Chapter 10 Alcohol harm reduction in Europe

| Reports - EMCDDA Harm Reduction |

Drug Abuse

Chapter 10 Alcohol harm reduction in Europe

Rachel Herring, Betsy Thom, Franca Beccaria, Torsten Kolind and Jacek Moskalewicz

Abstract

This chapter provides an overview of harm reduction approaches to alcohol in Europe. First,

definitions ascribed to alcohol harm reduction are outlined. Then, evaluated alcohol harm

reduction interventions in European countries are described and the evidence for their

effectiveness examined. These include multi-component programmes, improvements to the

drinking environment, and initiatives to reduce the harms associated with drink-driving. Third,

harm reduction activities that have been recorded and described but not yet evaluated are briefly

outlined. These include ‘grassroots’ initiatives and more formal local initiatives. To conclude, the

chapter raises questions about how alcohol harm reduction is defined and put into practice, the

evidence-base that is available for policymakers, and how information is shared. It highlights the

need to develop systems to facilitate knowledge transfer on alcohol harm reduction between

researchers, policymakers and practitioners in Europe but stresses the importance of respecting

local and cultural diversity in the development and implementation of harm reduction initiatives.

Keywords: alcohol, harm reduction, Europe, evaluation.

Introduction

The consumption of alcohol is an integral part of many European cultures and is embedded in

a variety of social practices. Whilst drinking alcohol is, for the most part, a pleasurable

experience often associated with relaxation and celebrations, there are a number of societal

and health harms associated with its consumption. The European Union (EU) is the heaviest

drinking region of the world (Anderson and Baumberg, 2006) and alcohol is linked to multiple

health and social problems. Health-related conditions include cancer, injury, liver cirrhosis and

cardiovascular disease; it is estimated that in the EU alcohol is responsible for 7.4 % of all

disability and premature deaths (Anderson and Baumberg, 2006, p. 401). At a global level, it

is estimated that 3.8 % of all deaths and 4.6 % of disability-adjusted life years are attributable

to alcohol (Rehm et al., 2009, p. 2223). There is also a broad range of societal harms

associated with alcohol consumption including crimes, violence, unemployment and

absenteeism, which place a significant burden on societies and economies (WHO, 2008a)

A wide array of measures are employed by European countries to reduce the harms

associated with alcohol. These include restrictions on availability, taxation, education

campaigns, laws on drink-driving, and a range of formal and informal interventions

commonly referred to as ‘harm reduction’ or ‘risk reduction’ measures. Yet the concept of

harm reduction is contested — as is the usefulness of this approach — and there is very little

rigorous evaluation of harm reduction projects or programmes, including in Europe.

This chapter begins with a brief overview of alcohol consumption and alcohol-related harms in

Europe. This will be followed by an examination of what is meant by the term ‘harm reduction’

in relation to alcohol. It then considers harm reduction interventions that have been evaluated

in European countries, also drawing upon the broader published literature, much of which is

North American or Australasian. We briefly outline harm reduction activities that have been

recorded and described but not yet evaluated. These include ‘grass roots’ initiatives and more

formal local initiatives. In conclusion, we argue for a clarification of what is meant by the term

‘alcohol harm reduction’, and the creation of more effective systems for sharing information and

collecting data, alongside research to examine the extent to which harm reduction is seen as an

appropriate approach to reducing alcohol-related harms in the different countries of Europe.

Alcohol-related harm in Europe

The relationship between alcohol consumption and health and social outcomes is complex and

multidimensional. Key factors include: volume of alcohol drunk over time; pattern of drinking (for

example, occasional or regular drinking to intoxication); and drinking context (e.g. place,

companions, occasion) (WHO, 2008a). The countries with the highest overall alcohol

consumption in the world are in eastern Europe, around Russia, but other areas of Europe also

have high overall consumption (WHO Europe region 11.9 litres per adult; Rehm et al., 2009, p.

2228). In all regions worldwide, including Europe, men consume more alcohol than women, and

are more likely to die of alcohol-attributable causes, suffer from alcohol-attributable diseases

and alcohol-use disorders (Rehm et al., 2009; Anderson and Baumberg, 2006). Europe has the

highest proportion of alcohol-attributable net deaths and within Europe the highest proportion is

for the countries of the former Soviet Union (Rehm et al., 2009, p. 2229). Alcohol is thought to

be responsible for 12 % of male and 2 % of female deaths in Europe (Anderson and Baumberg

2006, p. 3), and 25 % of male youth mortality and 10 % of female youth mortality (Anderson

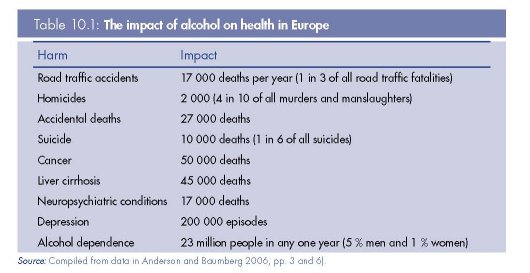

and Baumberg 2006). The health impact of alcohol is seen over a wide range of conditions (see

Table 10.1 for examples) and includes acute harms (e.g. accidents and injuries as a result of

intoxication) and harms associated with longer-term consumption (e.g. cirrhosis).

Alcohol consumption can negatively impact on an individual’s work, their relationships and

studies (e.g. absenteeism, breakdown of relationships) and consequently on other people (e.g.

families, colleagues) and society as a whole. At a societal level the harms associated with the

consumption of alcohol include public nuisance (e.g. disturbance, fouling of the streets),

public disorder (e.g. fights), drink-driving and criminal damage. The tangible costs of alcohol

to the EU (that is, to the criminal justice system, health services, economic system) were

estimated to be EUR 125 bn in 2003; this included EUR 59 bn in lost productivity due to

absenteeism, unemployment and lost working years through premature death (Anderson and

Baumberg, 2006, p. 11); the intangible costs of alcohol (which describe the value people

place on suffering and lost life) to the EU were estimated to be EUR 270 bn in 2003

(Anderson and Baumberg, 2006, p. 11).

What is alcohol harm reduction?

Although in recent times the term ‘harm reduction’ has mostly been associated with the illicit

drug field, alcohol harm reduction strategies have been used for centuries (Wodak, 2003;

Nicholls, 2009). For instance, in England, the idea that those serving alcoholic beverages

should be legally responsible for preventing customers from getting drunk can be traced

back to James I’s 1604 ‘Act to restrain the inordinate haunting and tipling of inns, alehouses

and other victualling houses’; in practice the law was largely ignored, but it did establish an

important principle (Nicholls, 2009, p. 11). Examples of similar formal and informal

constraints on behaviour can be found in other European countries and, indeed, worldwide.

In sixteenth century Poland an innkeeper was supposed to make sure that farmers had no

dangerous objects with them in a pub, as they often became violent after drinking and then

would try to use drunkenness as an excuse for their behaviour (Bystoń, 1960). Thus, those

who served alcohol combined their profit-oriented job with harm reduction. Women have

often served as social control or harm reduction agents; in Patagonia, Indian Tehuelche

young women, not yet of drinking age, collected all weapons, including knives and axes,

prior to a drinking party to prevent severe injures in a case of alcohol-induced violence

(Prochard, 1902).

Measures to ensure the safety of alcoholic beverages (that is, free from harmful

adulteration or contamination, regulation of the alcohol content of drinks) are also longstanding

and remain important. Austrian wine adulterated with diethylene glycol (found in

antifreeze) to make it taste sweeter was withdrawn from sale across the world in the mid-

1980s (Tagliabue, 1985). Regulation of the sale and size of containers of medicinal (pure)

alcohol has reduced the harms associated with its consumption in Nordic countries

(Lachenmeier et al., 2007). Research in Estonia (Lang et al., 2006) examining the

composition of illegally produced (such as home-produced) and surrogate alcohol products

(e.g. aftershave, fire lighting fuel) found high levels of alcohol by volume (up to 78.5 %) and

various toxic substances (e.g. long chain alcohols). Moreover, it is likely that the

consumption of surrogate alcohol and illegally produced alcohol contributes to the high

mortality and morbidity associated with alcohol consumption in other countries in transition

(see, for example, McKee et al., 2005; Leon et al., 2007 on Russia).

Harm reduction principles were central to the influential ‘Gothenburg System’, named after

the Swedish city that first adopted the approach in 1865 (Pratt, 1907). Under Swedish law

private companies could be established that were empowered to buy up the sprits trade in

specific localities and run it on a not-for-profit basis, thus removing the financial incentive to

sell large quantities of spirits. Managers whose salaries were not dependent on high sales of

spirits (the law did not cover sales of beer or food) were employed to run the pubs. Although

the effectiveness of the Gothenburg System in reducing excessive consumption was not

entirely clear (Nicholls, 2009), it was an idea that attracted much interest and was adopted

in other places, including Bergen, Norway. The Gothenburg system also inspired the system

of ‘disinterested management’, established in late nineteenth century England, whereby

companies were formed that bought up pubs and employed salaried managers;

shareholders, in return for their investment, received a capped dividend on their investment.

However, the impact of this scheme was limited by the small number of establishments run on

these lines (Nicholls, 2009).

Whilst not a new idea, harm reduction was not particularly formulated as a concept for

policy intervention until it came to prominence in the illicit drugs field in response to HIV/AIDS

in conjunction with the spread of HIV through sexual intercourse and drug injecting

(Stronach, 2003). There was a recognition that sexual abstinence and stopping injecting

drugs was not a feasible option for many people, so realistic and pragmatic strategies were

required that focused on managing the outcomes of behaviour rather than eliminating or

changing the behaviour (Stronach, 2003). As Stockwell (2006) notes, what made harm

reduction distinctive when it emerged in the drugs field was the practice of encouraging safer

behaviour (e.g. not sharing injecting equipment and using condoms for sex) without

necessarily reducing the occurrence of the behaviour (see, for example, Lenton and Single,

1998 and box below).

|

World Health Organization definition of harm reduction In the context of alcohol or other drugs, describes policies or programmes that focus directly on |

With respect to alcohol, Robson and Marlatt (2006) have argued that the World Health

Organization (WHO) has emphasised total population measures, such as restricting supply,

almost to the point of discounting other approaches. However, the WHO are in the process

of drafting a global strategy to reduce the harmful use of alcohol (to be considered by the

World Health Assembly in May 2010) and harm reduction has been identified as one of nine

possible strategy and policy element options (WHO, 2008a). At the same time, whilst

acknowledging the positive contribution of harm reduction measures, the WHO note that the

evidence base is not, as yet, as well established as that for regulating the availability and

demand for alcohol (WHO, 2008a).

However, since the 1990s harm reduction has become increasing influential in the alcohol

field; indeed Robson and Marlatt (2006, p. 255) contend that ‘it is now, up to a point, the

conventional wisdom’. So what is alcohol harm reduction? As is common with such terms it

will depend on whom you ask or where you look. Stockwell (2006) has shown that the term

is applied in many different ways, some of which rather push the boundaries of ‘harm

reduction’. For Stockwell, what distinguishes harm reduction from other approaches is that it

does not require a reduction in use for effectiveness, rather it is about seeking to ‘make the

world safer for drunks’ (2004, p. 51). On their website the International Harm Reduction

Association (IHRA) state, ‘Alcohol harm reduction can be broadly defined as measures that

aim to reduce the negative consequences of drinking’ (IHRA, n.d.), whilst Robson and Marlatt

(2006, p. 255) suggest that the common feature of harm reduction interventions is that they

do not aim at abstinence.

These broader definitions encompass interventions that do not attempt to reduce

consumption, such as the provision of safety (shatterproof) glassware in drinking venues,

‘wet’ shelters, ‘sobering up’ stations, and which often focus on specific risk behaviours (e.g.

drink-driving), particular risk groups (e.g. young people) and particular drinking contexts (e.g.

clubs, bars). They also encompass interventions that implicitly or explicitly do aim to reduce

alcohol consumption, for example server training, brief interventions and controlled drinking.

But the labelling of approaches that aim to reduce alcohol use as ‘harm reduction’ has been

challenged, with Stockwell (2004, 2006) arguing that such interventions would be better

described as ‘risk reduction’ as they require the reduction of alcohol intake to less risky levels.

Furthermore, a recent round-table discussion involving health professionals and nongovernmental

organisations about harmful alcohol use, concluded that: ‘Brief interventions

are not considered to constitute a harm reduction approach because they are intended to

help people drink less’ (WHO, 2008b, p. 8).

Stronach (2003, p. 31) identified five key elements that should underpin alcohol harm policies

and interventions:

• Harm reduction is a complementary strategy that sits beside supply control and demand

reduction.

• Its key focus is on outcomes rather than actual behaviours per se.

• It is realistic and recognises that alcohol will continue to be used extensively in many

communities, and will continue to create problems for some individuals and some

communities.

• Harm reduction is non-judgemental about the use of alcohol, but is focused on reducing

the problems that arise.

• It is pragmatic — it does not seek to pursue policies or strategies that are unachievable or

likely to create more harm than good.

Thus, within policy and research discourse, the notion of ‘alcohol harm reduction’, although

influential, has not gone unchallenged or without controversy. Indeed, there has been a

tendency, particularly within the media, to dismiss or even ridicule harm reduction

approaches. Within the United Kingdom, recent harm reduction interventions, including

handing out ‘flip-flops’ to women drinkers to prevent injuries caused by falling over in high

heels or walking barefooted, have attracted negative headlines (Hope, 2008; Salked,

2008).

This lack of consensus can be reflected in the responses of service and policy providers

across Europe. To capture how harm reduction is understood and how related strategies are

implemented in practice in Europe, we conducted a brief survey of the 30 European

Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) Heads of Focal Groups. We

received responses from Austria, Belgium, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Cyprus, Estonia,

Finland, Latvia, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain and Sweden.

We asked our survey informants what they understood by the term ‘harm reduction’. The

definitions they gave were anchored around the concept of limiting or reducing the negative

health, social and economic consequences of alcohol consumption on both individuals and

communities. A key idea was that harm reduction approaches do not seek to convince

individuals to abstain or to introduce prohibition but rather take a ‘pragmatic’ approach to

reducing harms associated with drinking.

Distinctions were made between harm reduction initiatives, which aimed to minimise

harm once it has actually been caused, and risk reduction initiatives, which aimed to

prevent harm being caused. Several respondents placed qualifiers; for example, the

respondent from Norway did not classify ‘responsible host’ or educational campaigns as

harm reduction measures. Similarly the Swedish respondent classified as ‘harm

reduction’ only those measures that aimed to reduce harm that already exists to some

extent.

Such variations were not unexpected but do highlight the fact that, whilst there might be a

shared language, the meaning attributed to the term ‘harm reduction’ can differ from one

European country to another. While the meaning of harm reduction varies by country, it is

important that the measures used are based on evidence and focused on outcomes (WHO,

2008b, p. 14). Evidence, however, is scanty.

Reducing alcohol-related problems: the international evidence

According to findings from international research, the most effective interventions include

alcohol taxes, restrictions on the availability of alcohol and measures to reduce drinkdriving;

interventions identified as the least effective include alcohol education, public

awareness programmes and designated driver schemes and many of the ‘harm

reduction’ approaches (Babor et al., 2003; Anderson, et al., 2009). Stockwell (2004, p.

49) argues that the most effective interventions to prevent alcohol-related harm require

reduction in the amount of alcohol consumed on a single occasion but suggests that

other measures can be employed alongside measures to reduce total population

consumption.

There is some international evidence about ‘what works’ to reduce alcohol-related harm as

defined in this chapter. The impact of screening and brief intervention (sometimes referred to

as ‘identification and brief advice’), particularly in primary care settings, in reducing harmful

alcohol consumption has been extensively evidenced as effective (Babor et al., 2003; Kaner

et al., 2007), although, as mentioned earlier, the inclusion of brief interventions as a harm

reduction measure is contested.

Graham and Homel (2008, pp. 196–238) provide a useful overview of the problems of

reducing alcohol-related aggression in and around pubs and clubs and review the

evidence for prevention and harm reduction measures. As they report, only a small number

of interventions have been evaluated with sufficient rigour to draw conclusions. They

mention a large randomised controlled trial of the Safer Bars Programme (a ‘stand-alone’

programme in Ontario, Canada), which consists of a risk assessment component, a training

component and a pamphlet outlining legal responsibilities, as having a modest but

statistically significant effect on incidents of aggression. Police enforcement trials did not

provide sufficient evidence to make recommendations but the Alcohol Linking Programme

(Australia) indicated the success of using place of last drinks data as the basis for targeted

enforcement. Community action models to implement local policy depend heavily on

partnerships but have demonstrated some success. This approach, evaluated largely in

North America, Australia, New Zealand and Scandinavia, has been described as ‘any

established process, priority, or structure that purposefully alters local social, economic or

physical environments to reduce alcohol problems’ (Holder 2004, p. 101); it is discussed

more fully below.

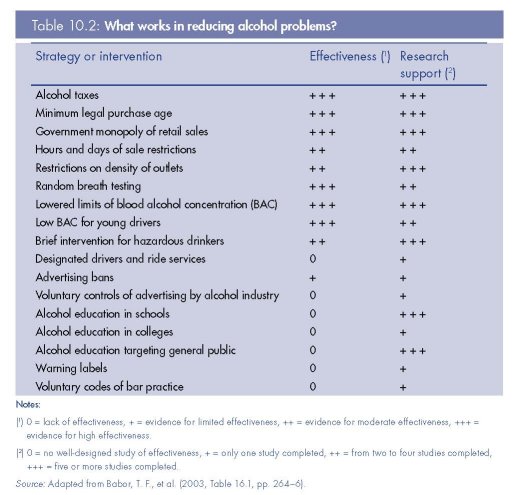

In a comprehensive synthesis and assessment of the international evidence, Babor et al.

(2003) offer a menu of interventions, which they have rated on four major criteria:

evidence of effectiveness, breadth of research support, extent of testing across diverse

countries and cultures, relative cost of the intervention in terms of time, resources and

money. The assessment reflects a consensus view of the 15 expert authors. For illustration,

Table 10.2 (adapted from Babor et al., 2003) shows ratings for two of the criteria:

interventions that were rated on effectiveness from none (zero) to highest (three ), and

interventions rated on breadth of research support from none (zero) to highest (three). The

table tells us, for example, that alcohol education in schools has five or more studies of

effectiveness but that there is no good evidence of effectiveness. It clearly indicates that

typical harm reduction measures such as warning labels on alcohol, designated driver

schemes and voluntary codes of practice are judged as least effective, although, as

illustrated in the second column, many harm reduction measures have few well-designed

evaluation studies. However, increasing attention has been given to the potential of

programmes of projects rather than stand-alone initiatives to achieve change. These ‘multicomponent’

programmes, which include many of the harm reduction interventions rated as

least successful, are discussed in the following sections.

Harm reduction approaches to alcohol in Europe: evaluated initiatives

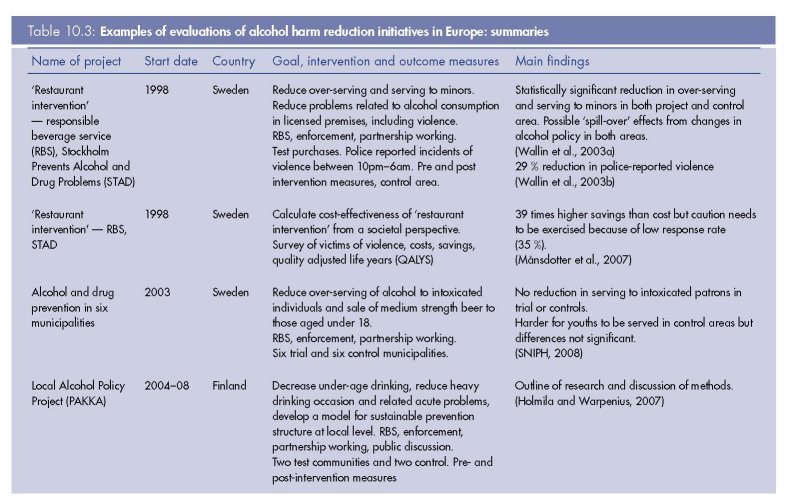

Although the focus of this section is on harm reduction initiatives that have been evaluated in

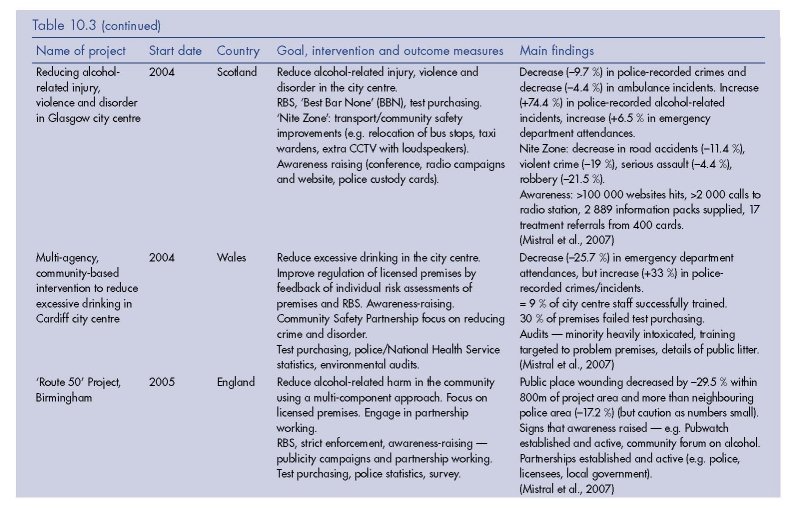

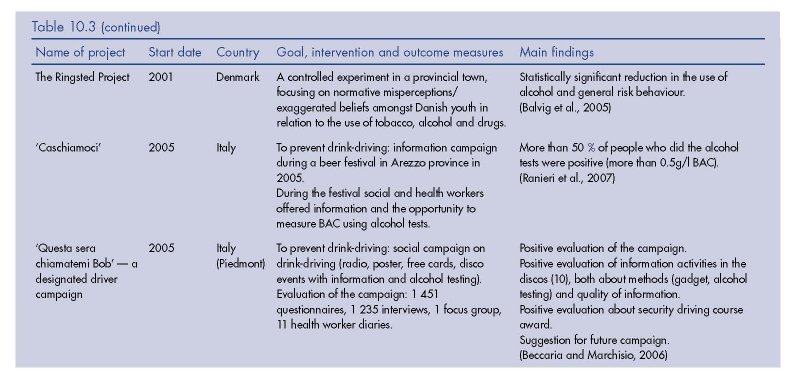

a European context, we also draw on the broader literature. Table 10.3 provides a summary

of the evaluated alcohol harm reduction interventions we have identified either from the

European literature or from international sources. Many evaluated harm reduction

interventions are part of multi-component community programmes designed to prevent and

reduce alcohol-related harm, whilst others are ‘stand alone’ interventions delivered at the

local or national level. First, the multi-component approach will be outlined, followed by an

examination of harm reduction interventions under two broad themes: improving the drinking

environment and reducing the harms associated with drink-driving. Interventions that form

part of multi-component programmes are summarised in the box on p. 288 and some will be

considered in more detail under the relevant theme. Although brief interventions are often

regarded as harm reduction, this chapter will not consider brief interventions, in part because

such classification has been contested (as noted above) and because an extensive literature

already exists and has been reviewed elsewhere (Nilsen et al., 2008).

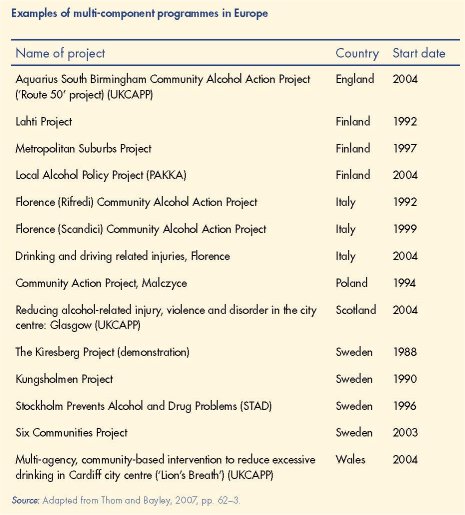

Multi-component programmes

Multi-component programmes involve the identification of alcohol-related problems at the

local level and implementation of a programme of coordinated projects to tackle the

problem, based on an integrative design where singular interventions run in combination

with each other and/or are sequenced together over time; the identification, coordination

and mobilisation of local agencies, stakeholders and community are key elements (Thom and

Bayley, 2007). Furthermore, as Thom and Bayley (2007) note, evaluation is an integral part

of multi-component programmes; both the overall programme and the individual projects

within it should have clearly defined aims, objectives and measures of effectiveness. Another

key element is that projects and the programme as a whole should have a strategic

framework underpinned by a theoretical base.

The ‘systems theory approach’, which is closely associated with the work of Holder and

colleagues in the United States (Holder, 1998), and the ‘community action’ approach have

been particularly influential (see Thom and Bayley, 2007, pp. 35–9). The United States,

Australia and New Zealand were at the forefront of the development of multi-component

programmes in the alcohol field and influenced the establishment of such programmes in

Europe (e.g. Holmila, 2001). Multi-component programmes have been conducted in

Scandinavia, Italy, Poland and the United Kingdom (see box on p. 288 and Table 10.3) and

have included a range of harm reduction projects. Whilst the specific targets of the multicomponent

programmes vary, the majority aim to influence community systems and change

drinking norms, and most aim to mobilise local communities with the intention of securing

sustainable, long-term change. For example, STAD (Stockholm prevents Alcohol and Drug

problems), a multi-component community programme in Sweden that ran 1996–2006,

included responsible beverage service training, community mobilisation and strict

enforcement of alcohol laws (Wallin, 2004; Wallin et al., 2003a; Wallin et al., 2003b; Wallin

et al., 2004; Månsdotter et al., 2007).

So, do multi-component programmes work? There is, as Thom and Bayley (2007)

conclude, ‘no simple answer’ to this question. Whilst there is evidence from international

research as to what is likely to work at a ‘stand alone’ level (see Table 10.2), what is less

clear is how they work in combination or what kind of combinations may result in an

effective multi-component programme. This is in part because of the expected synergistic

effect of the components and also the possible cumulative effects over time; furthermore,

it has not been possible to identify the contribution of particular components to

programme outcomes as a whole (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2000).

For example, educational and awareness-raising campaigns are often cited as ineffective

in changing behaviour (see Table 10.2) but are seen as a crucial element of most multicomponent

programmes. Anderson and colleagues (2009) argue that although the

evidence shows that information and education programmes do not reduce alcoholrelated

harm, they do play a key role in providing information and in increasing

awareness of the need to place alcohol issues firmly on public and political agendas

(Anderson, et al., 2009).

Although evaluation is integral to multi-component programmes, in reality these evaluations

are complex and it is not only difficult to untangle the effects of the interventions from each

other, but also from other activities in the locality. In relation to the evaluation of the three

projects in the United Kingdom Community Alcohol Prevention Programme (UKCAPP), Mistral

et al. commented:

The UKCAPP projects were part of a multi-faceted web of other local projects, partnerships, and

interventions … The complexity of these partnerships meant that it was impossible to consider any

UKCAPP project as a discrete set of interventions, clearly delineated in space, and time, the

effects of which could be evaluated independently of other local activities.

(Mistral et al., 2007, p. 86)

Another important issue highlighted by the UKCAPP evaluation was the inadequacy of

statistical datasets, which meant that it was impossible to judge the effectiveness of

interventions over time (Mistral et al., 2007). This was in part due to the different methods of

data collection, analysis and retrieval used by police, ambulance service and emergency

care departments, which made data validity hard to verify and comparison across sources or

sites highly problematic (Mistral et al., 2007). In addition, local issues (e.g. timing of

intervention, funding delays, getting agreement from all partners) can make systematic local

evaluation challenging.

In summary, whilst some programmes have reported considerable successes (e.g. Community

Trials Project, reported by Holder, 2000), others have yielded more mixed results, including

the Lahti project in Finland (Holmilia, 1997), Kiresberg project (Hanson et al., 2000) and

STAD (Wallin et al., 2003a) in Sweden. However, Thom and Bayley (2007) in their overview

conclude that the evidence suggests that a multi-component approach has a greater chance

of success than stand-alone projects.

Harm reduction interventions

Improving the drinking environment

Observational studies indicate that the drinking environment of licensed premises can impact

on the risk of violence and injury. A lack of seating, loud music, overcrowding, unavailability

of food are considered risk factors (Graham and Homel, 2008; Homel et al., 2001; Rehm et

al., 2003). A variety of initiatives to improve the drinking environment have been

implemented. These include server training, awards to well-managed licensed premises and

the use of safety glassware (or plastic). A recent systematic review concluded that there was

no reliable evidence that interventions such as these in the alcohol server setting are effective

in preventing injuries (Ker and Chinnock, 2008). Nevertheless, we look at some of the

research findings for each of these interventions in turn.

Server training

A number of European countries including Spain, United Kingdom, Ireland and the

Netherlands have developed national responsible beverage service (RBS) training and

accreditation schemes (EFRD website, 2009). Responsible beverage service is a key

feature of many Scandinavian and United Kingdom multi-component programmes (see

Table 10.3), with the aim of reducing sales to minors, over-serving and violence in and

around licensed premises. These interventions usually involve formal training of staff and

strict enforcement of existing alcohol laws; outcome measures include test purchasing and

police statistics.

Results have been mixed. The STAD project in Sweden took a quasi-experimental approach

with a control area, also located in central Stockholm, but not adjacent to the project area. In

relation to both over-serving and serving to minors there was a statistically significant

reduction in both the control and project areas, although in the project area the improvement

in relation to over-serving was slightly higher (but not statistically significant) (Wallin et al.,

2003a). Wallin et al. (2003a) note that during the time of research the Stockholm Licensing

Board (which covers both areas) altered practices and policy, and this might be one

explanation for why there were changes in alcohol service in both the project and the control

area (i.e. spill-over effects).

In contrast, there was a reduction in violence only in the project area, with a 29 % reduction

in police-reported violence in and around licensed premises (Wallin et al., 2003b). The

authors put forward several explanations for this result. First, there were a greater number of

large nightclubs in the project area and changes in practice in large establishments may

have a greater impact than changes in smaller establishments. Second, it may be a synergy

effect, with improved serving practices and increased enforcement combining to produce a

positive effect (Wallin et al., 2003b; SNIPH, 2008). Although it did appear to be harder for

youths to get served in the project site than the control, the differences were not statistically

significant (SNIPH, 2008).

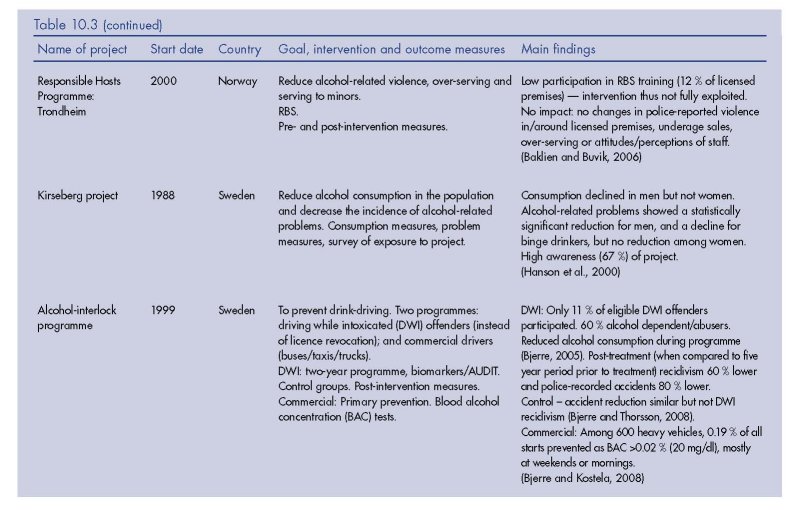

Other studies, for example in Trondheim, Norway, experienced a low uptake of the

intervention, and not surprisingly no impact was observed (Baklien and Buvik, 2006). The

‘Route 50’ project in Birmingham, an area with no history of partnership working, faced

similar challenges, but boosted uptake by providing incentives (e.g. waived the course fee)

(Mistral et al., 2007). Whilst there were decreases in police-recorded statistics compared to

the adjacent area, the number of crimes was low and thus no inferences could be safely

drawn (Mistral et al., 2007).

Awards for management of premises

In 2003, as part of a broad, multi-agency programme to reduce alcohol-related crime and

disorder in the city centre area, Manchester developed a scheme, called ‘Best Bar None’

(BBN), to identify and recognise the best-managed licensed premises in the area (Home

Office, 2004) (see box on p. 291 for details). The scheme has since been rolled out

nationally, but despite this BBN has yet to be fully evaluated. Although ‘a detailed

assessment’ of the impact of BBN on reducing disorder is planned (Harrington, 2008), a

small-scale evaluation concluded that there was ‘a lack of credible evidence to suggest that

the implementation of the BBN scheme in Croydon has specifically had an impact on the

reduction of crime and disorder in the town centre on its own’ (GOL, 2007, p. 2). Whilst

acknowledging there were benefits for those who implemented the scheme, these benefits

were difficult to measure and ‘largely amount to perception rather than evidenced reality’

(GOL, 2007, p. 2). The report recommended that if the BBN is to continue, then an agreed

measuring tool (that is, set of indicators) is required, so that the impact of the schemes can

be assessed and can provide credible evidence for other areas considering its

implementation (GOL, 2007).

|

From pilot project to national scheme — Best Bar None 2003 |

Use of safety glassware

Research in the United Kingdom identified that bar glasses were being used as weapons to

inflict injuries, in particular to the face (Shepherd et al., 1990b). Further research concluded

that the use of toughened glass would reduce injuries (Shepherd et al., 1990a; Warburton

and Shepherd, 2000). This research led to the replacement of ordinary glassware with

toughened glassware in licensed premises and there is evidence from the British Crime

Survey that this change resulted in a significant reduction of violent incidents involving the use

of glasses or bottles as weapons (Shepherd, 2007). However, Shepherd (2007) notes that

reductions in glass injury have not been sustained — probably because of the increased

availability of bottled drinks and the use of poorly toughened glass. Despite repeated calls,

there is, as yet, no manufacturing standard but the use of alternative materials, particularly

plastics, is seen as a way forward.

In 2006, as part of its approach to reducing alcohol-related violence and disorder in the

city centre, Glasgow city council banned the use of glassware (other than special ‘safety’

glass) from venues holding an entertainment licence — which in practice meant nightclubs

(Forsyth, 2008). However, individual premises could apply for an exemption for

champagne/wine glasses (Forsyth, 2008). The study, based on naturalistic observations

and interviews, reported that exemptions to the ban had allowed some premises to

continue to serve in glass vessels, and this resulted in injuries. Although disorder in allplastic

venues was observed, it incurred less injury risk and Forsyth (2008) concluded that

the research demonstrated the potential of such policy to reduce the severity of alcoholrelated

violence in the night-time economy. Earlier initiatives, for example ‘Crystal Clear’

in Liverpool, aimed to remove glass from outdoor public places in the city centre in order

to reduce glass injuries; a high-profile awareness campaign was mounted and action

taken by bar and door staff to prevent glass being removed (Young and Hirschfield,

1999). The evaluation found that there was high recognition of the campaign and police

and hospital data showed a reduction in glass injuries during the campaign (Young and

Hirschfield, 1999).

Reducing the harms associated with drink-driving

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses have found that highly effective drink-driving policies

include lowered blood alcohol concentration (BAC), unrestricted (random) breath testing,

administrative licence suspension, and lower BAC levels and graduated licenses for novice

drivers (Babor, et al., 2003; Anderson, et al., 2009). Less effective are designated driver

schemes and school-based education schemes (Babor et al., 2003). We look at three

examples — BAC measures, ‘alcolocks’ (or alcohol-interlocks, which are devices that prevent

a motor vehicle from starting when a driver’s BAC is elevated) and designated driver

schemes.

BAC measures

All European countries place legal limits on the BAC of drivers and the 2001 European

Commission Recommendation on the maximum permitted blood alcohol concentration

(BAC) for drivers of motorized vehicles called for all Member States to adopt a BAC of

0.5 g/L, lowered to 0.2 g/L for novice, two-wheel, large vehicle or dangerous goods

drivers; in addition, random breath testing was recommended so that everyone is checked

every three years on average (Anderson, 2008). There are currently three Member States

of the EU-27 that have a BAC limit of greater than 0.5 g/L (Ireland, Malta and the United

Kingdom) (ETSC, 2008). There is evidence that the reduction in BAC limits supported by

strict enforcement and publicity can reduce drink-driving at all BAC levels. For example,

Switzerland reduced the legal BAC limit from 0.8 g/L to 0.5 g/L and introduced random

breath testing in January 2005. The number of alcohol-related road deaths in 2005

reduced by 25 per cent and contributed to an overall 20 % reduction in the number of

road deaths (ETSC, 2008).

Alcolocks

Alcolocks (or alcohol-interlocks) are devices that prevent a motor vehicle from starting

when a driver’s BAC is elevated. Sweden introduced two alcolock programmes in 1999,

which have been evaluated. One programme involved commercial drivers (of taxis,

lorries and buses); in 600 vehicles, 0.19 % of all starts were prevented by a BAC higher

than the legal limit and lock point of 0.2 g/L, mostly during weekends and mornings

(Bjerre and Kostela, 2008). Another was a voluntary two-year programme for drinking

while intoxicated (DWI) offenders, which included regular medical monitoring designed

to reduce alcohol use and was offered in lieu of having licence revoked for a year. There

were two control groups; one group had revoked licences but did not have the

opportunity to participate in an interlock programme, and the other comprised DWI

offenders who had declined the opportunity to participate in the programme (Bjerre and

Thorsson, 2008). Only 11 % of eligible drivers took part in the programme. The

intervention group were significantly more likely to be re-licensed two and three years

after the DWI offence than the control groups and also, according to Alcohol Use

Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) scores, had lower rates of harmful alcohol

consumption. In the post-treatment period the rate of DWI recidivism was about 60 %

lower, and the rate of police-reported traffic accidents about 80 % lower than during the

years before the offence. Among the controls being re-licensed, a similar reduction in

traffic accidents was observed but not in DWI recidivism. Bjerre and Thorsson (2008)

conclude that these results suggest that the alcolock programme was more effective than

the usual licence revocation and also that it was a useful tool in achieving lasting

changes in the alcohol and drink-driving behaviour of DWI offenders. To date systematic

reviews of research indicate that alcolocks are only effective whilst in situ (Willis et al.,

2004; Anderson, 2008) and further work is required into what steps need to be taken to

prevent recidivism and ensure behaviour changes are sustained.

Designated driver schemes

The designated driver concept was first initiated in Belgium in 1995, jointly by the

(industry-funded) Belgian Road Safety Institute and Arnouldous (EFRD, 2007). Designated

driver campaigns are currently running in 16 European countries (EFRD, 2009) and were

co-financed by the European Commission for five years (ETSC, 2008). Table 10.3

provides a summary of an evaluated designated driver scheme in Italy (Beccaria and

Marchisio, 2006). There is no universal definition of a ‘designated driver’, but the most

common definition requires that the designated driver does not drink any alcohol, be

assigned before alcohol consumption, and drive other group members to their homes

(see Ditter et al., 2005). Other definitions adopt a risk and harm reduction strategy, in

which the main goal is not necessarily abstinence, but to keep the designated driver’s

blood alcohol content (BAC) at less than the legal limit. The evidence is that although the

BACs of designated drivers are generally lower than those of their passengers they are

still often higher than the legal limit for drinking and driving. Furthermore, an increase in

passenger alcohol consumption is often found when a designated driver is available. To

date, no study has evaluated whether the use of designated drivers actually decreases

alcohol-related motor vehicle injuries (Anderson, 2008). Anderson (2008) argues that

existing designated driver campaigns should be evaluated for their impact in reducing

drink-driving accidents and fatalities before financing and implementing any new

campaigns.

Alcohol harm reduction in Europe: non-evaluated harm reduction initiatives

In this section, we look at examples of harm reduction initiatives that have been recorded

and described in the literature but not thoroughly evaluated, and also at examples given by

our key informants (see box below). Harm reduction initiatives often begin as practical

responses to a problem rather than as a research question and thus are not usually formally

evaluated, at least not in the first instance. Information about such initiatives at the local level

is often difficult to come by. This indicates that there is a need for systematic pooling of

information, particularly for dissemination of knowledge about smaller local or regional

initiatives. One attempt at systematic collection of data is being promoted in the United

Kingdom. The Hub of Commissioned Alcohol Projects and Policies (HubCAPP) is an online

resource of local alcohol initiatives focused on reducing alcohol-related harms to health

throughout England (www.hubcapp.org.uk) launched in 2008. The focus of HubCAPP is on

identifying and sharing local and regional practice in relation to reducing alcohol harm, and

it is constantly expanding. Although not exclusively a database of harm reduction initiatives,

many of the projects can be classified as such, for example, the ‘Route 50 Project’ a multicomponent,

community-based initiative in Birmingham (Goodwin and McCabe, 2007).

|

Harm reduction initiatives: some examples that have been recorded and described • ‘Flip-flops’ (simple flat shoes) given to women who are experiencing difficulties walking in |

Some of the non-evaluated initiatives can be described as ‘grassroots’ interventions, that is,

they have been devised and initiated by lay people (e.g. parents, members of a local

community) to reduce alcohol-related harm within the local community. For example, in

provincial Denmark, parents have organised parties where young people drink alcohol

under adult supervision, with the aim of reducing harmful drinking in unsupervised outdoor

areas (Kolind and Elmeland, 2008). In similar vein, in Slovakia, in an attempt to supervise

the behaviour of young people coming home from parties, pubs and discos, local people

and police formed patrols to guide young people home safely and with minimal

disturbance to the community. Grassroots initiatives are generally pragmatic and reactive

and they may also be very specific to a time and place. However, if such initiatives appear

to be ‘successful’ they may over time be subject to formal evaluation and also be

implemented in other areas.

Other initiatives have been developed by agencies such as police, local government, health

and welfare agencies, often working in partnership, and like the ‘grassroots’ initiatives they

are aimed at reducing alcohol-related harm in the local area. Such initiatives are often

innovative, for example, giving out ‘goody bags’ containing items including sweets, ‘flip-flops’

(simple flat shoes), water, condoms and information leaflets on alcohol and safer sex, as part

of campaigns to reduce alcohol-related harm and disorder in town centres (Chichester

Observer, 2008; Hope, 2008; Lewisham Drug and Alcohol Strategy Team, 2007). The

innovative nature of these interventions generates media coverage, much of which is negative

or cynical (e.g. Hope, 2008; Salkeld, 2008; Smith, 2008 — on bubble blowers, flip-flops and

lollipops), and some groups (e.g. Taxpayers’ Alliance, United Kingdom) dismiss these harm

reduction measures as ‘gimmicks’ and a ‘waste of money’.

Whilst most of these measures have been introduced relatively recently, other interventions

have a longer history. For example, the first ‘sobering up station’ (záchytka) opened in

Czechoslovakia (now the Czech Republic) in 1951. It provided a place for intoxicated people

to sober up. It was a model that was soon adopted by other countries, including Poland

which established sobering up stations following the decriminalisation of public drunkenness

in 1956 (Moskalewicz and Wald,1987). Facilities that serve a similar function are dotted

across Europe; for example Scotland has two ‘designated places’ (in Aberdeen and

Inverness), which provide an alternative to custody for persons arrested for being drunk and

incapable; they are monitored in a safe environment until fit to leave, and further help is

available. There have been calls for a comprehensive system of ‘designated places’ to

provide a safe place for intoxicated people to sober up and to divert them from the criminal

justice and health systems (BBC, 2007).

There are a number of routes by which knowledge of successful interventions is spread,

both informal and more formal, including identification, dissemination and awards for

‘best practice’ (e.g. by government agencies, interest groups), fact finding visits, web

resources (e.g. HubCAPP in the United Kingdom), stakeholder networks and organisations

(e.g. Global Alcohol Harm Reduction Network — GAHRA-Net). The Internet plays a key

role in the exchange of information globally through websites, online publications, and

virtual networks.

Policy and knowledge transfer can be aided by thorough evaluation of interventions. But

whilst it is straightforward to find a description of a simple ‘evaluation’ of a particular

intervention, as we have seen in the case of BBN, robust, comprehensive evaluation is often

lacking. However, it is not merely a question of the evaluation of interventions. What works in

provincial Denmark may not work in inner city Paris, and care needs to be taken not to

simply ‘cherry pick’ interventions. Cultural and local contexts are important factors in

transferring intervention models and are often ignored when apparently successful projects

or programmes are ‘rolled out’.

Conclusion

Current usage and definition of the concept of harm reduction derives from the drugs field

rather than from the long history of formal and informal regulation of alcohol-related harm.

The lack of consensus regarding the definition and a tendency to include within the definition

initiatives that are contested as being ‘prevention’ and not really ‘harm reduction’, suggests both

a risk that the adoption of a very broad definition may result in loss of meaning and usefulness

of the concept for policy and practice and an opportunity to debate and clarify the concept

and its application in differing national, local and cultural contexts. Apart from the distinction

between measures that aim to reduce consumption, and measures that tackle only associated

harms, approaches to reduce or minimise harm once it has happened (harm reduction) can be

distinguished from risk reduction measures, which aim to prevent harm being caused in the first

place. These nuances of meaning have important implications for the development of strategy,

the adoption of specific projects and programmes, the evaluation of policies and initiatives and

for the effectiveness outcomes researchers choose to measure. Although the evidence base for

harm reduction approaches appears less solid than the evidence for measures to reduce

consumption, there has been far less research and fewer evaluated studies of measures that

address the harms without necessarily requiring lower consumption. This would be useful, both

in designing locally appropriate multi-component programmes and in providing a ‘menu’ of

evaluated initiatives to run alongside measures aimed at consumption levels.

It is also essential to establish the boundaries of inclusion in ‘harm reduction’ if more effective

systems for information sharing and data collection in Europe are to be agreed. Information

on harm reduction approaches — especially those that emerge from local or grassroots

activity — is hard to come by. Descriptions on websites are often ephemeral, and this is a

reflection also of the origins of harm reduction activity, which is frequently rooted in transient

local concern and crises. As the crisis or concern recedes, the initiatives fade away. At the

same time, most harm reduction activity appears to be semi-official (as opposed to grassroots

or lay), emerging at regional or local levels from professional and local authority action.

Sometimes a particular initiative catches the policy and public attention and is transferred

from one area to another, based more on the perception of success rather than on any

evaluation or formal assessment of effectiveness or of the appropriateness of transfer from

one setting to another. The development of information sharing systems, nationally and

possibly on a European scale, would be a step forward in providing the field with a more

comprehensive overview of harm reduction measures, settings in which they have been

implemented and with what results, and measures of effectiveness.

While harm reduction ‘thinking’ has joined the raft of policy strategies and local initiatives in

most European countries, remarkably few initiatives have been fully described, let alone

scientifically evaluated with any degree of rigour. This in itself may be one reason why

assessments of effectiveness based on international research result in harm reduction

measures being reported as less effective. However, before demanding conformity to ‘gold

standard’ evaluation studies, it is worth considering the nature and uses of many harm

reduction approaches. If, as appears to be the case, harm reduction requires flexibility and

immediacy in its reaction to locally defined need, there is a case for arguing that descriptions

of the approach and narratives of the implementation and perceived outcomes are more

useful than formal (expensive) evaluation. Such narratives are largely missing and could be

an important addition to information banks such as the United Kingdom’s HubCAPP.

Evaluation and research findings are, of course, only one element in decisions to adopt or

reject harm reduction as a legitimate goal for policy and in decisions about which initiatives

are suitable for implementation nationally or locally. Success or failure of harm reduction

initiatives can depend as much on media and public perceptions (as in the case of ‘flip-flops’)

or on gaining the collaboration of stakeholders (as in the case of server training) or the

willingness of volunteers (as in the Danish ‘Night Owls’ and the Danish parents’ parties) as on

the evaluated effectiveness of a particular strategy or activity. This is especially the case if the

evaluations emerge from projects located in very different social, cultural and political

systems. So questions arise as to what extent harm reduction is seen as an appropriate

approach to reducing alcohol-related harms in the different countries of Europe. Is harm

reduction the ‘conventional wisdom’ in Europe or are there countries where harm reduction is

thought to be inappropriate to that particular country’s cultural context and consumption

patterns? These are questions that deserve further exploration. In the drive towards a Europewide

planned approach to tackling alcohol-related harm, this overview of harm reduction

approaches highlights the need to develop opportunities and systems to facilitate knowledge

transfer on alcohol harm reduction between researchers, policymakers and practitioners in

Europe, but stresses the importance of respecting local and cultural diversity in the

development and implementation of harm reduction initiatives.

References

Anderson, P. (2008), Reducing drinking and driving in Europe, Deutsche Hauptstelle für Suchtfragen e.V. (DHS),

Hamm.

Anderson, P. and Baumberg, B. (2006), Alcohol in Europe: a public health perspective. A report for the European

Commission, Institute of Alcohol Studies, London. Available at http://ec.europa.eu/health-eu/doc/alcoholineu_

content_en.pdf (accessed 20 July 2009).

Anderson, P., Chisholm, D. and Fuhr, D. (2009), ‘Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of policies and programmes

to reduce the harm caused by alcohol’, Lancet 373, pp. 2234–46.

Babor, T., Caetano, R., Casswell, S., et al. (2003), Alcohol: no ordinary commodity, Oxford University Press,

Oxford.

Babor, T. F. (2008), Evidence-based alcohol control policy: toward a public health approach, Conference on

Tobacco and Alcohol Control — Priority of Baltic Health Policy, Vilnius.

Baklien, B. and Buvik, K. V. (2006), Evaluation of a responsible beverage service programme in Trondheim, Sirus-

Reports 4 (English summary), SIRUS, Oslo. Available at http://www.sirus.no/internett/alkohol/publication/310.

html (accessed 20 January 2010).

Balvig, F., Holmberg, L. and Sørensen, A-S. (2005), Ringstedforsøget. Livsstil og forebyggelse i lokalsamfundet [The

Ringsted project: lifestyle and prevention in the local community], Jurist-og Økonomiforbundets Forlag,

København.

BBC (2007), Profits ‘to aid alcohol problems’, BBC News 10 October 2007. Available at http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/

hi/scotland/north_east/7036806.stm (accessed16 July 2009).

Beccaria, F. and Marchisio, M. (2006), ‘Progetto Bob. Vatutazione di una compagna di promozione del

guidatore designato’, Dal fare al dire 15 (2), pp. XII–XX.

Bjerre, B. (2005), ‘Primary and secondary prevention of drink driving by the use of alcolock device and program:

Swedish experiences’, Accident Analysis and Prevention 37 (6), pp. 1145–52.

Bjerre, B. and Kostela, J. (2008), ‘Primary prevention of drinking driving by the large-scale use of alcolocks in

commercial vehicles’, Accident Analysis and Prevention 40 (4), pp. 1294–9.

Bjerre, B. and Thorsson, U. (2008), ‘Is an alcohol ignition interlock programme a useful tool for changing the

alcohol and driving habits of drink-drivers?’, Accident Analysis and Prevention 40 (1), pp. 267–73.

Bystoń, J. (1960), Dzieje obyczajów w dawnej Polsce. Wiek XVI-XVII. PIW, Warszawa.

Chichester Observer (2008), ‘Police to hand out flip flops to clubbers in Bognor’, 26 December.

Ditter, S. M., Elder, R. W., Shults, R. A., et al., (2005), ‘Effectiveness of designated driver programs for reducing

alcohol-impaired driving a systematic review’, American Journal of Preventative Medicine 28 (5 Supplement), pp.

280–7.

EFRD (European Forum for Responsible Drinking) (2007), Guidelines to develop designated driver campaigns,

EFRD, Brussels.

EFRD (2009), European Forum for Responsible Drinking website at www.efrd.org/main.html (accessed 9 March

2009).

ETSC (European Transport Safety Council) (2008), Drink driving fact sheet. Available at www.etsc.eu/documents/

Fact_Sheet_DD.pdf (accessed 9 March 2009).

Forsyth, A. J. M. (2008), ‘Banning glassware from nightclubs in Glasgow (Scotland): observed impacts,

compliance and patrons’ views’, Alcohol and Alcoholism 43 (1), pp. 111–17.

Goodwin, P. and McCabe, A. (2007), From loose, loose to win, win: Aquarius Route 50 project. Report to the AERC.

Available at: www.hubcapp.org.uk (accessed 9 March 2009).

GOL (Government Office for London) (2007), Best Bar None Croydon review, GOL, London. Available at http://

ranzetta.typepad.com/Croydon_BBN_evaluation.doc (accessed 9 March 2009).

Graham, K. and Homel, R. (2008), Raising the bar: preventing aggression in and around bars, pubs and clubs,

Willan Publishing, Cullompton.

Hanson, B. S., Larsson, S. and Rastram, L. (2000), ‘Time trends in alcohol habits: results from the Kiresberg

project in Malmo, Sweden’, Substance Use and Misuse 35 (1 & 2), pp. 171–87.

Harrington, J. (2008), ‘Sky’s the limit for Best Bar None’, Morning Advertiser, 16 June. Available at http://www.

morningadvertiser.co.uk/news.ma/article/62912 (accessed 12 March).

Holder, H. D. (1998), Alcohol and the community: a systems approach to prevention, Cambridge University Press,

Cambridge.

Holder, H. D. (2000), ‘Community prevention of alcohol problems’, Addictive Behaviours 25 (6), pp. 843–59.

Holder, H. D. (2004), ‘Community action from an international perspective’, in Müller, R. and Klingemann, H.

(eds), From science to action? 100 years later – alcohol policies revisited, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht,

pp. 101–12.

Holmlia, M. (1997), Community prevention of alcohol problems, Macmillan Press, Basingstoke.

Holmlia, M. (2001), ‘The changing field of preventing drug and alcohol problems in Finland: can communitybased

work be the solution?’, Contemporary Drug Problems 28 (2), pp. 203–20.

Holmila, M. and Warpenius, K. (2007), ‘A study on effectiveness of local alcohol policy: challenges and

solutions in the PAKKA project’, Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy 14, pp. 529–41.

Home Office (2004), Alcohol audits, strategies and initiatives: lessons from Crime and Disorder Reduction

Partnerships, Home Office Development and Practice Report 20,Home Office, London.

Homel, R., McIlwain, G. and Carvolth, R. (2001), ‘Creating safer drinking environments’, in Heather, N., Peters, T.

and Stockwell, T. (eds), International handbook of alcohol dependence and problems, John Wiley & Sons Ltd,

Chichester, pp 721–40.

Hope, C. (2008), ‘Police give free goodie bags containing condoms, flip-flops and lollipops to drinkers’, Daily

Telegraph, 20 December. Available at www.telegraph.co.uk/news/newstopics/politics/lawandorder/3850898/

Police-give-free-goodie-bags-containing-condoms-flip-flops-and-lollipops-to-drinkers.html (accessed 4 February

2009).

IHRA (International Harm Reduction Association) (n.d.), ‘What is alcohol harm reduction?’ Available at www.

ihra.net/alcohol (accessed 4 February 2009).

Kaner, E. F. S., Dickinson, H. O., Beyer, F. R., et al. (2007), ‘Effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary

care populations’, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2007, Issue 2, Art. No.: CD004148. DOI:

10.1002/14651858.CD004148.pub3.

Ker, K. and Chinnock, P. (2008), ‘Intervention in the alcohol server setting for preventing injuries’, Cochrane

Database of Systematic Reviews, Issue 3, Art No.: CD005244. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD005244.pub3.

Kolind, T. and Elmeland, K. (2008), ‘New ways of socializing adolescents to public party-life in Denmark’, in

Olson, B. and Törrönen, J. (eds), Painting the town red: pubs, restaurants and young adults’ drinking cultures in the

Nordic countries, Vol. 51, NAD (Nordic Centre for Alcohol and Drug Research), Helsinki, pp. 191–219,

Lachenmeier, D., Rehm, J. and Gmel, G. (2007), ‘Surrogate alcohol: where do we know and where do we go?’,

Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 31910, pp. 1613–27.

Lang, K., Väli, M., Szűcs, S., Ádány, R. and McKee, M. (2006), ‘The composition of surrogate and illegal alcohol

products in Estonia’, Alcohol and Alcoholism 41 (4), pp. 446–50.

Lenton, S. and Single, E. (1998), ‘The definition of harm reduction’, Drug and Alcohol Review, 17 (2), pp. 213–19.

Leon, D. A., Saburova, L.,Tomkins, S., et al. (2007), ‘Hazardous alcohol drinking and premature mortality in

Russia: a population based case-control study’, Lancet 369 (9578), pp. 2001–9.

Lewisham Drug and Alcohol Strategy Team (2007), Don’t binge and cringe evaluation: Lewisham 2007 anti-binge

drinking festive campaign. Available at www.alcoholpolicy.net/files/dont_binge_and_cringe_evaluation.pdf

(accessed 4 February 2009).

Månsdotter, A. M., Rydberg, M. K., Wallin, E., Lindholm, L. A. and Andréasson, S. (2007), ‘A cost-effectiveness

analysis of alcohol prevention targeting licensed premises’, European Journal of Public Health 17, pp. 618–23.

McKee, M., Suzcz, S, Sárváry, A., et al. (2005), ‘The composition of surrogate alcohols consumed in Russia’,

Alcoholism Clinical and Experimental Research 29, pp. 1884–8.

Mistral, W., Velleman, R., Mastache, C. and Templeton, L. (2007), UKCAPP: an evaluation of 3 UK Community

Alcohol Prevention Programs. Report to the Alcohol Education and Research Council. Available at www.aerc.org.uk/

documents/pdfs/finalReports/AERC_FinalReport_0039.pdf (accessed 10 February 2009).

Moskalewicz, J. and Wald, I. (1987), ‘From compulsory treatment to the obligation to undertake treatment:

conceptual evolution in Poland’, Contemporary Drug Problems Spring, pp. 39–51.

Nicholls, J. (2009), The politics of alcohol: a history of the drink question in England, Manchester University Press,

Manchester.

Nilsen, P., Kaner, E. and Babor, T. F. (2008), ‘Brief intervention, three decades on: an overview of research

findings and strategies for more widespread implementation’, Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs 25 (6), pp.

453–67.

Pratt, E. A. (1907), Licensing and temperance in Sweden, Norway and Denmark, John Murray, London.

Prochard, H. (1902), ‘Through the heart of Patagonia, London’, quoted in Horton, D. (1943), ‘The functions of

alcohol in primitive societies: a cross-cultural study’, Quarterly Journal of Studies on Alcohol 4.

Ranieri, F. et al. (2007), ‘Prevenzione ad una festa della birra?’, S&P: Salute e Prevenzione: La Rassegna Italiana

delle Tossicodipendenze 22 (45), pp. 59–68.

Rehm, J., Room, R., Monteiro, M., et al. (2003), ‘Alcohol as a risk factor for global burden of disease’, European

Addiction Research 9, pp. 157–64.

Rehm, J., Mathers, C., Popova, S., et al. (2009), ‘Global burden of diseases and injury and economic cost

attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders’, Lancet 373, pp. 2223–32.

Robson, G. and Marlatt, G. A. (2006), ‘Harm reduction and alcohol policy’, International Journal of Drug Policy

17, pp. 255–7.

Salkeld, L. (2008), ‘Flipping madness! Police offer free flip-flops to binge drinkers who keep falling over in heels’,

Daily Mail, 27 November. Available at www.dailymail.co.uk/newsarticle-1089919/Flipping-madness-Police-offerfree-

flip-flops-binge-drinkers-falling-heels.html (accessed 4 February 2009).

Shepherd, J. (2007), ‘Preventing violence — caring for victims’, Surgeon 5 (2), 114–21.

Shepherd, J. P., Price, M. and Shenfine, P. (1990a), ‘Glass abuse and urban licensed premises’, Journal of the

Royal Society of Medicine 83, pp. 276–7.

Shepherd, J. P., Shapland, M., Pearce, N. X. and Scully, C. (1990b), ‘Pattern, severity and aetiology of injuries in

victims of assault’, Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 83, pp. 75–8.

Smith, D. (2008), ‘How to calm binge drinkers: get them all blowing bubbles’, Observer, 30 November. Available

at: www.guardian.co.uk/society/2008/nov/30/binge-drinking-bubbles (accessed 9 February 2009).

Stockwell, T. (2004), ‘Harm reduction: the drugification of alcohol policies and the alcoholisation of drug

policies’, in Klingemann, H. and Müller, R. (eds), From science to action? 100 years later — alcohol policies

revisited, Klewer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, pp. 49–58.

Stockwell, T. (2006), ‘Alcohol supply, demand, and harm reduction: what is the strongest cocktail?’, International

Journal of Drug Policy 17, pp. 269–77.

Stronach, B. (2003), ‘Alcohol and harm reduction’, in Buning, E., Gorgullo, M, Melcop, A. G. and O’Hare, P.

(eds), Alcohol and harm education: an innovative approach for countries in transition, Amsterdam, ICAHRE, pp.

27–34.

SNIPH (Swedish National Institute of Public Health) (2008), Alcohol prevention work in restaurant and mediumstrength

beer sales in six municipalities (English summary), Stockholm: SNIPH. Available at www.fhi.se/en/

Publications/Summaries/Analysis-of-alcohol-and-drug-prevention-work-in-six-municipalities/ (accessed 28

January 2009).

Tagliabue, J. (1985), ‘Scandal over poisoned wine embitters village in Austria’, New York Times, 2 August.

Available at www.nytimes.com/1985/08/02/world/scandal-over-poisoned-wine-embitters-village-in-austria.

html?sec=health (accessed 14 July 2009).

Thom, B. and Bayley, M. (2007), Multi-component programmes: an approach to prevent and reduce alcohol-related

harm, Joseph Rowntree Foundation, York.

US Department of Health and Human Services (2000), 10th special report to the US Congress on alcohol & health,

US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute on Alcohol and Alcoholism, Washington, DC.

Warburton, A. L. and Shepherd, J. P. (2000), ‘Effectiveness of toughened glassware in terms of reducing injury in

bars: a randomised controlled trial’, Injury Prevention, pp. 36–40.

Wallin, E. (2004), Responsible beverage service: effects of a community action project, Karolinska Institutet,

Stockholm.

Wallin, E., Norström, T. and Andréasson, S. (2003a), ‘Effects of a community action project on responsible

beverage service’, Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs (English supplement) 20, pp. 97–100.

Wallin, E., Norström, T. and Andréasson, S. (2003b), ‘Alcohol prevention targeting licensed premises: a study of

effects on violence’, Journal of Studies on Alcohol 64, pp. 270–7.

Wallin, E., Lindewald, B. and Andréasson, S. (2004), ‘Institutionalization of a community action program

targeting licensed premises in Stockholm, Sweden’, Evaluation Review 28 (5), pp. 396–419.

Willis, C., Lybrand, S. and Bellamy, N. (2004), ‘Alcohol ignition interlock programmes for reducing drink driving

recidivism’ (Review), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2004, Issue 3, Art. No.: CD004168.

DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD004168.pub2.

Wodak, A. (2003), ‘Foreword’, in Buning, E., Gorgullo, M., Melcop, A. G. and O’Hare, P. (eds), Alcohol and

harm education: an innovative approach for countries in transition, ICAHRE, Amsterdam, pp. 1–4.

WHO (World Health Organization) (1994), Lexicon of drug and alcohol terms. Available at http://www.who.int/

substance_abuse/terminology/who_lexicon/en/index.html (accessed 24 June 2009).

WHO (2008a), Strategies to reduce the harmful use of alcohol: report by the Secretariat to the 61st World Health

Assembly, 20 March 2008, A61/13, World Health Organization, Geneva. Available at http://apps.who.int/gb/

ebwha/pdf_files/A61/A61_13-en.pdf (accessed 24 June 2009).

WHO (2008b), Report from a roundtable meeting with NGOS and health professionals on harmful use of alcohol,

Geneva, 24 and 25 November, World Health Organization, Geneva. Available at http://www.who.int/

substance_abuse/activities/msbngoreport.pdf (accessed 24 June 2009).

Young, C. and Hirschfield, A. (1999), Crystal clear: reducing glass related injury. An evaluation conducted on behalf

of Safer Merseyside Partnership, University of Liverpool, Liverpool.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|