RITUALS OF REGULATION: INSTRUMENTAL FUNCTIONS OF SOLITARY DRUG USE RITUAL

| Books - Drug Use as a Social Ritual |

Drug Abuse

RITUALS OF REGULATION: INSTRUMENTAL FUNCTIONS OF SOLITARY DRUG USE RITUAL

Chapter four described the two ritual patterns of heroin use that are most prevalent in The Netherlands. The overwhelming majority in the study did not limit their drug use to heroin only, and also consumed cocaine and, to a lesser extent, other psychoactive substances. They are polydrug users. The nesting of cocaine in heroin rituals has had a profound influence on the total drug use pattern of the research subjects. Chapter five discussed the effects of this high prevalence of cocaine use on the use patterns and the consequences for the individual users and their social environment. Chapter six presented the findings on transitions between the two common administration rituals. In these chapters the discussion was largely limited to "the observable sequences of psychomotor acts" --the first of the two requirements of the definition of ritual utilized in this study. It was demonstrated that both the use patterns of IDUs and chasers, whether they use heroin only or in whatever combination with cocaine, fulfill the definitional requirement of a prescribed sequence. The extensive descriptions established that for both rituals a well defined set of paraphernalia is dictated --all with their specific function.

Whereas before the discussion was largely confined to the descriptive level, the coming chapters will take a more analytical approach and concentrate on the instrumental functions, and symbolic meaning of drug use rituals (the special meaning part of the definition). Chapter seven discusses the instrumental function, while chapter eight will focus on the symbolic meaning at an individual level. Chapter nine addresses the significance of these rituals for the relationships between drug using individuals in their social networks.

Instrumental Functions of Drug Use Rituals

Rituals fulfill various functions depending on the circumstances. Some of those functions are more and others less obvious. The fulfillment of practical needs related to the day-to-day management of drug use is an important aspect of both solitary and social rituals. In particular, in solitary drug use rituals this function is stressed. These rituals can be observed to function as regulatory device which aims at:

- Maximizing the desired drug effect.

- Controlling drug use levels and balancing the positive and negative effects of the used drugs.

- Preventing secondary problems.

In practice, these functions are highly intertwined and for the superficial observer they may be hard to separate. For the purpose of analysis, however, they will be dealt with as separate as possible.

Maximizing the Desired Drug Effect.

Maximizing the desired drug effect can be seen in the preparation, the actual administration phase of the ritual and shortly after the drug has been administered. The first two excerpts from fieldnotes are examples of such preparatory ritual actions:

He puts a couple of drops of lemon juice into the cup, enough to cover the heroin that is already in there. He then adds a few drops of water from the plastic bottle. "I first boil it with 'much' lemon and little water, it dissolves better this way". He puts his lighter under the scale ... and boils the content. He doesn't cook it through, but boils it shortly several times. Then he adds more water to it and boils it all. He shows what is happening inside the cup. "You see, it dissolves beautifully, almost no dirt stays behind".

With a knife Henry took out ± 1 stripe of cocaine and put it in a teaspoon. He then poured a little ammonia in the spoon and then he added a little salt (baking soda). "Adding a little salt to the ammonia gives the best results, I think."

In both cases the users try to maximize the output of consumable product by ritual procedure. In the first case boiling the base heroin with a strong acidic solution is an effective measure, but cooking it for a few short times instead of one longer but equivalent interval is not. What matters is the (low) pH value related to the total cooking time. Correspondingly, adding bicarbonate to the ammonia to improve the conversion from cocaine hydrochloride to cocaine base is not a valid procedure as the pH of the ammonia is considerably higher than that of the bicarbonate. Thus, in both cases the behavior does not fit a means to an end scheme --it is unnecessary by empirical standards (1). In the first example the behavior is mingled with an act that does have a causal relationship with the end result. In the following three examples the relationship between means and end is more ambiguous:

Fred took the lumps and started smoking the base in a glass 'water bong'. This bong is designed to smoke cannabis. It had a picture of a cannabis plant on it. Fred did not put any water in it. "We used to put water in it." Henry said, "But we found out that without water it goes much better."

Whether water is used in base pipes or not is dependent on factors such as group norms and personal preferences. It may, however, be of some influence as the contents of the chamber of the pipe can hold more smoke than when it is filled with water.

After smoking Fred sat back, closed his eyes and laid his head against the back of the sofa. He pressed his fingers to his ears and stayed that way for about two minutes. He concentrated on the rush. ...

Eric took his shot and is concentrated on the flash, sitting on his chair with his head bowed. Meanwhile Leo enters the attic. [and starts talking to Eric.] ... Eric asks Leo not to talk to loud because he just took a cocktail.

Both Fred's posture and the position Eric is sitting in, are supposed to have a facilitating effect on their rush. Many users have developed their own specific sequence surrounding the administration of the drug, intended to boost the rush. Fred puts his fingers in his ears and Eric asks Leo to stop talking because they want to exclude outside stimuli which may distract their attention from their rush.

Chapter four presented some observations of booting (drawing blood back into the syringe and reinjecting one or more times). There exists some ambiguity in the scientific literature on the function of booting. According to Agar, IDUs boot for two reasons --to test the drug quality and to intensify the rush (2). Conversely, Zinberg argues that there is no causal relationship between booting and the rush (3). While assisting Doug with injecting, Jack, one of our key respondents, gave a more pragmatic explanation:

He takes the syringe, inserts the needle in the skin and hits a vein rather quickly. He pulls up some blood, presses the plunger, pulls up, presses, and pulls up again ± 2 cc. of blood. Then he takes out the needle because he lost the vein. He hits again and presses the blood-drug mixture in Doug's vein. "It's a waste to throw it away. There is still some dope in it." Jack says.

Jack, as most Rotterdam users, used a two-piece 2 ml syringe. When the plunger of such an syringe is pushed down completely, there still is some (0.05 - 0.1ml) solution left in the hub (4). This may go up to (an estimated) 5% of the injected dose and therefore have some effect on the intensity of the rush. A similar effect may work when using an eye dropper with an attached needle, the most prevalent injecting device in the time of Agar's research in the U.S.A. (1960s). In the 1970s, when Zinberg did his research, the 1 ml insulin syringes were more commonly used and these are constructed in a way that there is hardly a residue left in the barrel when the plunger is pushed down completely. This may explain Zinberg's conclusion. Even when this explanation is valid, it does not account for booting five or more times, which was repeatedly observed.

These activities are directed at the perfection of the performance (5) with the goal of increasing the desired effect of the drug. Perfection is reached through repetition. The pleasure inducing or rewarding effects of drugs are a main incentive for their use as can be witnessed in the following quotes: "I want to enjoy the coke flash"; "It's pleasing me the most when I smoke them together"; "White really is a delicacy"; "Ah, How nice it is!"; "I found the cocaine high delicious". Getting as much effect as possible from a given dose is the incentive for these actions.

Controlling Use Levels and Balancing Positive and Negative Effects of Drugs.

Most experienced users are well aware of the shadow sides complementing the desired effects of drug use --prolonged high intake of heroin leads to unmanageable dependence levels and frequent use of large amounts of cocaine results in negative side effects that outweigh the desired effects. An important function of drug taking rituals is to control use levels and manage or balance the negative and positive effects of the ingested substances. It is important to remark that control does not necessarily have to entail lower levels of intake. Within the study population, stability of use levels and successful prevention and management of, drug use (cocaine) related (psychological) problems may be more appropriate indicators of control. Control may best be perceived as a multidimensional process. Jack who is often employed as doorman at house addresses explained how he, in order to stay in control, organizes his use:

"I make 'kleine shotjes' (small fixes) with 1/4 to 1/2 'streep' (=0.025 to 0.050 gram) heroin in it, always. I will keep doing that. I mean, I can take more but than you get more sick too, and you can't effort it any more. Sometimes, when I do have more dope, I don't take bigger quantities in one shot, but I'll take more little fixes."

Jack has a rather stable use pattern. This is related to his rather continuous involvement in dealing, securing a steady availability of both cocaine and heroin. He further explained, that when working as a doorman his cocaine use goes up. Other users have more fluctuating use patterns --a period of heavy, uncontrolled use, followed by a period of regaining control in which they lower their intake or (temporarily) abstain from further use of, usually, cocaine:

Cor looks good. He wears a nice and clean shirt and a clean jeans. He tells he is working as a house painter again after a jobless period. At the moment he is with sick leave. He says he is doing alright now. However about two months ago he was not. He was in a period of intensive cocaine use. But he realized that he had to cut back his cocaine use to an acceptable amount and although he says this has cost much energy, he stopped taking cocaine to recover again. He tells that he is using cocaine moderately now.

The use of ritual procedure to regulate the level of drug use and to balance the positive and negative drug effects is common practice among the research participants. This is most evident in their day-to-day patterns of heroin and cocaine use. The overwhelming majority (96%) used cocaine and knowledge of, and experience with the negative side effects of this drug was widespread. Some users say they only use cocaine when there is enough to satisfy their craving:

He tells he's only smoking cocaine when he has enough money to buy a gram or more: "Otherwise it's to less and I flip. When I've used a gram or more I've had enough and won't buy no more."

Others periodically decrease their intake of heroin or stop using the drug altogether. This may be out of neglect, for example when binging on cocaine (see chapter 5.4.3) or intention --to decrease opiate tolerance or in an effort to stop using drugs. In the latter case, cocaine is sometimes used to ameliorate or cover heroin withdrawal:

"A few months ago I kicked heroin with cocaine. In that time I smoked ± 0.5 g cocaine per day and it didn't work me up at all. I felt high. When I smoke coke I want to be alone. When it's easy and quiet I don't get worked up from it."

However, cocaine used in administration rituals, doses and time schedules typical for this population (frequent smoking or injecting of relatively high doses) inevitably leads to a decrease of the desired effects and an increase of undesired ones. In order to control these undesired effects users frequently resort to the use of prescription drugs and heroin. According to many users, in particular heroin plays a crucial role in the process of leveling off the negative side effects of cocaine:

Some time later several inhabitants meet in the attic in Arie's room to drink tea. They talk about dope, making money, being stoned, pills, etc. ... [and] experiences are being exchanged about cocaine-use. Most of them tell they control cocaine through heroin.

Such statements are confirmed by many observations and informal interviews. Adding a knife tip of heroin (het kleurtje) to the colorless cocaine when smoked on aluminum foil is only partially done to make it easier to smoke or for hedonistic reasons. IDUs' cocktailing or injecting heroin shortly after a shot of cocaine is likewise not merely a matter of individual preference for a specific high. Countering undesired effects (dysphoria) is a prominent feature of these practices. Many users have an intense paradoxical relationship with cocaine, resulting in use patterns that spawn and boost the desired pleasurable effects while simultaneously self-medicating the negative side effects of the cocaine. They turn-take or combine cocaine and heroin, depending on personal preference, mood and drug availability. In the next excerpt Nadir explained his preference for turn-taking the two drugs:

Nadir isn't sure yet what he wants to buy. He says he only wants to buy some heroin "because cocaine makes me feel so para (paranoid)". But then suddenly he decides: "Well okay, I buy a little bit of cocaine too, just one streep", and he buys 1 stripe heroin and 1 stripe cocaine. ... I always first smoke the cocaine, pure without heroin. When I have finished the cocaine I start to smoke heroin. I must do it like that, otherwise the cocaine turns me crazy".

It becomes clear that such chemical mood control requires careful titration of the two substances. In the following, Jack explains the two main ways to manage the opposite effects of cocaine:

"Feeling the coke flash or not has to do with your spiritual attitude. When you don't want to feel it, you won't feel it. Users that don't feel relaxed won't get stoned nice." "When I take a shot of heroin after I took cocaine the speediness is taken away. You can talk relaxed again, you have the time to listen to other people. Then I feel myself becoming relaxed. In use there's a lot of suggestion." "A cocktail is a shot with 2 drugs, with different effects. I'll take a cocktail when I don't want to have such a strong coke flash. I always save some heroin to take after the cocktail. The flash from a cocktail is not as intense as from coke only. But, everybody has different experiences."

Jack's explanation underlines the importance of the interaction of pharmacological, psychological and social variables in controlling the drug effects. Drug use rituals aim to regulate these variables by standardizing the procedures utilized in the drug taking experience.

Cocaine use has been nested in rituals developed for heroin use and has taken over its function of primary source of pleasure. This development has altered the function of heroin use to a great extend. When both drugs are used, heroin use has become almost completely intertwined with and subservient to cocaine use. It is mainly used to modulate the effects of cocaine, in particular to ameliorate cocaine's disturbing side effects. Thus, a functional relationship between heroin and cocaine has been established, which is displayed in the integration of both drugs in shared administration rituals, the aim of which is to maintain a delicate balance of desired and undesired drug effects.

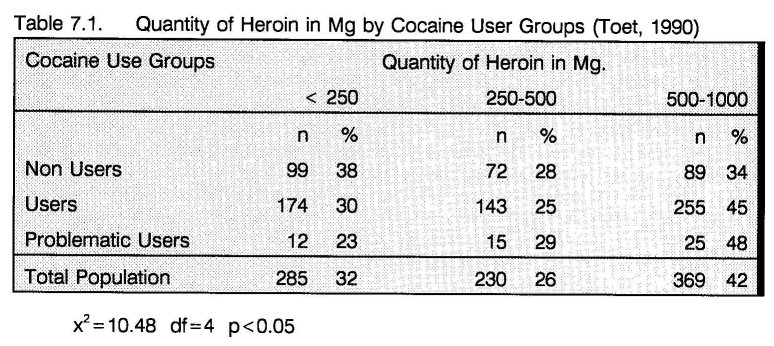

Support for the hypothesis that heroin is used to control the side effects of cocaine is offered by the Rotterdam (methadone maintenance) treatment intake data, which is recorded in RODIS. Only 32% of the heroin users, applying for methadone did not use cocaine at intake, while 62% did and for an additional 6% use of cocaine had become problematic (N=1095). Their level of heroin use is presented in the following table.

Conform the ethnographic results, the level of heroin use of cocaine users (especially the problematic users) was significantly higher than that of non-users (6). A recently published study by Grapendaal et al. reported similar results. "The most common combination is heroin and cocaine. ... [There exists] a very strong correlation between heroin and cocaine use. When both substances are used there exists a preference for similar quantities". Their results confirm the changed functions of both heroin and cocaine. Just as in this study, their respondents explicitly refer to the paradoxical effects of cocaine and the self-medication aspects of heroin in regards to the experienced cocaine related problems: "The coke is the nicest of all, but I don't want to become paranoia and therefore I always take some bruin with it" (7).

In chapter 5.5 it was suggested that prescription drugs have an additional value in controlling cocaine's side effects, in particular disturbed sleeping patterns and restlessness. Both the Grapendaal et al. study and RODIS corroborate the relevance of this suggestion. Cocaine and prescription drugs are combined in many polydrug use patterns (7). Users and problematic users of cocaine use significantly more substances than non users (6).

It can be argued that these ritual cocaine/heroin patterns are odd and rather inefficient regulatory devices. However, given the opportunities open to this group of regular users of cocaine and heroin, the prevention and management, or self-medication of cocaine related problems by use of heroin, does not seem an irrational option.

Additional Control Strategies

Many users do not have (permanent) access to financial resources required for maintaining the described cocaine/heroin pattern. They must resort to self regulation strategies that revolve around averting drug use situations and (periodical) abstinence. Then, regaining control is often the result of changes in the daily patterns and tightening up personal rituals and rules regarding drug use. About two months prior to the following fieldnote, Paco was in a period of heavy use. His landlord threw him out of his room, because he allowed many other users to get high at his place. The landlord had told him that they "did not live like normal people do." Being homeless, he spent the nights with friends he knew from the Central Station, who offered him a place to sleep --now here, then there. As he did not have his own place, he carried his works (injection paraphernalia) around and injected in public places, when drugs were available. When he told this, he was very stoned from heroin and prescription drugs. Two months later at the station he looked much better and talked about going to Morocco to withdraw and recover. He felt he had to as "I'm not living right this way, I've got to change." In fact, Paco had just made important changes that brought him back in control of his drug use:

Paco tells he has found a new room to rent last week. "I don't let other people use in my house anymore. They just make a lot of mess and troubles for me with the house keeper. Now, when I want to use, I get some dope and go home. There I make and take my shot. I'm not gonna walk around with lemon, spoon, spike, etc. I don't like to do that."

Compared to two months earlier he made considerable changes. He found a new room, but did not let other users get high there, which must have limited his drug intake substantially as in such situations drugs are often shared. He no longer used just because the occasion occurred, but tried to plan his use. Moreover, he stopped carrying his works around, averting him from using at other places than at home. (This may, however, bring him in a position in which he feels forced to share needles when he does need to use outside the house, e.g. when being in withdrawal.) Thus, by making significant changes in his ritual and adopting stricter rules --only injecting at home; not allowing other people to use at his place; plan his use; not carrying works-- which had a stabilizing effect on his life structure, (8) Paco regained control.

For other users, taking physical distance from the drugs (scene) seemed an important aspect of self regulation:

"We live in Zeeland. Originally we come from Rotterdam but we moved there because of the dope. It's very hard to get any there. But about once a week we make a trip to Rotterdam and buy some dope. We don't use every day. I get my methadone from the regional CAD. I can pick it up twice a week. They are rather flexible. I'm addicted for more than 15 years now, I tried to kick the habit many times and I've been clean for some periods. In one of these periods he came." He is pointing at the boy. It is a nice looking kid. He is well taken care off and looks good. He sits at his fathers feet hanging onto his legs. Softly he asks his parents when they will be leaving. "It is a good thing for us", his father says, "living in Zeeland. We don't use much, it's hard to get, that is good for us. I have a steady job there too." His wife tells she is using for 2.5 to 3 years now but she is not getting any methadone. "As he told we go about once a week to Rotterdam and that day we e.g. also go to the zoo, it's a day's outing that way."

By taking physical distance from the ritual place --the drug scene-- thus limiting the number of contacts that may lead to the start of the ritual sequence of drug ingestion, this couple regulates their access to the drugs. But they still like to use drugs and once a week they do. But by making this into a new ritual that combines drug use with other non-drug social activities, such as the visit to the zoo, they limit the time spent on using drugs, preventing an uncontrolled intake. From the fieldnote we can also see that the availability of methadone can be of help in keeping drug use under control. However, not all users fancy methadone. Especially Surinamese users often dislike this substitution drug. They emphasize its social control function, while it would furthermore lead to a double dependency. Sheep, a 35-40 years old Creole Surinamese man, who reported using heroin since 1972 explains his dislike of the substance:

"I use heroin and cocaine, I chase." Sheep feels that he is in reasonable control of his use. "Sometimes they (fellow users) ask me: You are never sick, how do you do that?" "Well, I am not in a methadone program. I don't want methadone, that is worse than heroin. You get much sicker from it."

Participating in a methadone program can also hamper plans of taking distance and regaining control:

"I was out of control, too much coke, you know. I first stopped the coke use. I was still in the methadone program. I had gone down with my dose. I took only three cc methadone per day, but I still had to come to the program every day. I didn't like that anymore. I was also reducing my heroin use, and coming to Rotterdam each day would make it only harder for me. Well, you know how it is, seeing everybody at the program each day. So, I'm not in a program anymore. I'm doing okay now, I'm back in control."

The daily methadone drinking routine can be considered a ritual --the sequence is highly determined and to the user it surely has special meaning (for one thing preventing withdrawal). The daily visit to the methadone program is often the moment of meeting user- friends, usually followed by procuring and using drugs. In this way the methadone ritual smoothly shifts into the ritual that leads to drug use. The quote "Well, you know how it is, seeing everybody at the program each day." has a strong symbolic contents as it refers to drug user knowledge "which cannot be shared or transmitted in the course of ordinary social interaction" (9). It not only refers to going to the program, but also to the fact that the people coming to the program, are participants in the same rituals of taking methadone and drugs. Visiting the methadone program is the daily start of a number of ritual sequences --meeting user friends, talking about ritual subjects such as wit and bruin, making plans to raise money and going out together to do so, going to a dealing address to procure and use drugs and to socialize. In this respect, it can also be ascertained that rituals can disturb self regulation. While the daily visit to the methadone program offers some degree of life structure, (8) it remains a question if this is always a positive contribution, as this activity promotes contacts with other daily users. Just as the house address, the methadone program carries several characteristics of a ritual place.

Preventing secondary problems

Several distinguishable parts of the drug administration ritual are directed at preventing or limiting the impact of so called secondary problems. Chapter four already presented a few examples of such practices. Chasers often save their aluminum covered pipe for the following morning. When they then wake up and do not have money nor drugs smoking the residue in the pipe will take the first withdrawal symptoms away. Some IDUs use ascorbic powder for dissolving base heroin instead of lemon juice. It is believed to be safer than using lemon juice. The use of a filter when drawing the injectable solution into the syringe is meant to stop insoluble impurities and other particles from entering the body, preventing infections. The practice of heating the strip of aluminum foil before the drug is put on it and smoked is another clear example. It is meant to prevent the inhalation of a coating, which supposedly causes respiratory or other health problems. Chapter five described two practices of cocaine smokers that are also directed at preventing or limiting damage to the respiratory system -- rinsing the cocaine base lump with water after preparing it with ammonia and using sodium bicarbonate instead of ammonia. Besides the supposed preventative effect on the respiratory system, some users also believe that this act averts "a terrible headache". What in fact is the effect of these precautions is not always clear. It has however become clear that many users practice spontaneous protective measures.

Rituals Communicate Cultural Norms

Many of the above described rituals have over the course of time developed into cultural norms --users may point at them and correct one another when they are not followed. For example, the practice of saving filters is generally disapproved of, as many users know, some by personal experience (in particular older users), that cooking up the filters and injecting this solution may cause a severe bodily reaction accompanied by sudden high fevers, chills, body shakes, etc., known as the shakes (in the Netherlands) or cotton fever (in the U.S.A.). One time a user was observed scolding a fellow user with cotton fever.

It was likewise observed that the knowledge of many of these practices is passed on to other users, normally in the course of the ritual performance itself. Rituals play an important role in educating novices about the rules of drug use (5). They serve to buttress, reinforce and symbolize these rules. Generally such information flow takes place at an unconscious level, as part of a peer group based social learning process (10). However, it is not uncommon to see more experienced users explicitly explain to novices why and how certain things ought to be done, as can be witnessed in the following two excerpts from fieldnotes:

The blonde (smoking) cocaine user is very interested in the shooting and watches it carefully. He asks some questions about how it is done and why. Doug answers his questions patiently ...

One of the [men] was explained a part of the cocaine chasing ritual. One of his friends put a lump of base on the foil and then with a lighter ... he melted the lump from above and let just a little smoke come from it. "This is what you do to take the ammonia rests out of it." "It's better for your lungs and you taste the difference." One of his other friends said.

Myths are an important ingredient of the observed rituals. For example, some users think that ascorbic powder is bad for the health, as it would "deposit on the heart valves". In particular cocaine seems surrounded by myth. Some users believe that cocaine melts at body temperature. Therefore holding a pack of cocaine in the hand or close to the body for some time is thought to affect the quality of the drug. But the melting point of cocaine is significantly higher than body temperature. For the same reason many IDUs, when preparing a cocktail, let the heroin solution cool down before adding the cocaine. Likewise, an injection of cocaine is never boiled. Cocaine may dissolve in water at room temperature, but heating the solution would probably prevent a lot of abscesses, associated with cocaine injecting, due to unsterile conditions. A probable explanation for these cocaine myths could be that cocaine is a relatively new drug in the Dutch heroin scene. Consequently, the knowledge about cocaine use may be still underdeveloped.

Many of the described rituals and rules are developed in the drug scene during a long process of casual information exchanges in informal networks --generally not based on objective information, but on personal experiences of users. Frequently the source of such information is not traceable and for many users its validity is hard to check (11). Therefore, many rules and ritual procedures contain rational and non-rational elements. In both cases they are supposed to have an impact on the outcome of the ritual. In actuality, they may or may not have such effects.

In his 1970s study on the determinants of controlled and uncontrolled drug use, Zinberg already argued that even "the most severe alcoholics and addicts ... do not use as much of the intoxicating substance as they could." He stated that "[s]ome aspects of control always operate" (12). The results of the present study reveal that, in fact, the observed activities surrounding the intake of drugs are, to a large extend, directed at safety and self regulation.

- Nadel SF: Nupe religion. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1954.

- Agar MH: Into that whole ritual thing: Ritualistic drug use among urban American heroin addicts. In: Du Toit BM (ed.): Drugs, rituals and altered states of consciousness. Rotterdam: Balkema, 1977: 137-148.

- Zinberg NE: Drug, set, and setting: The basis for controlled intoxicant use. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1984.

- Grund JPC, Stern LS: Blood rests in Syringes; Not only the size matters, but also the type of syringe. AIDS 1991; 12(5): 1532-1533.

- Nagendra SP: The concept of ritual in modern sociological theory. New Delhi: The academic journals of India, 1971.

- Toet J: Het RODIS nader bekeken: Cocainegebruikers, Marokkanen en nieuwkomers in de Rotterdamse drugshulpverlening rapport 87. Rotterdam: GGD-Rotterdam e.o., Afdeling Epidemiologie, 1990.

- Grapendaal M, Leuw E, Nelen JM: De economie van het drugsbestaan: Criminaliteit als expressie van levensstijl en loopbaan. Arnhem: Gouda Quint, 1991.

- Faupel CE: Drug availability, life structure and situational ethics of heroin addicts. Urban Life 1987; 15(3,4):395-419.

- Cleckner PJ: Cognitive and ritual aspects of drug use among young black urban males. In: Du Toit BM (ed.): Drugs, rituals and altered states of consciousness. Rotterdam: Balkema, 1977: 149-168.

- Harding WM, Zinberg NE: The effectiveness of the subculture in developing rituals and social sanctions for controlled drug use. In: Du Toit BM (ed.): Drugs, rituals and altered states of consciousness. Rotterdam: Balkema, 1977: 111-134.

- Des Jarlais DC, Friedman SR, Sotheran JL, Stoneburger R: The sharing of drug injection equipment and the AIDS epidemic in New York City: The first decade. In: Battjes RJ & Pickins RW (eds.): Needle sharing among intravenous drug abusers: National and international perspectives. Rockville: NIDA, 1988, pp 160-175.

- Zinberg NE: The social setting as a control mechanism in intoxicant use. In: Lettieri DJ, Sayers M, Wallenstein Pearson H (eds.): Theories on drug abuse: selected contemporary perspectives, NIDA research monograph 30. Rockville Maryland: NIDA, 1980: 236- 244.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|