TRANSITIONS BETWEEN RITUALS OF ADMINISTRATION

| Books - Drug Use as a Social Ritual |

Drug Abuse

TRANSITIONS BETWEEN RITUALS OF ADMINISTRATION

Most research participants either chased or injected their drugs. In general, these drug administration rituals were rather stable. As explained in the previous chapter, cocaine basing may well be increasing among chasers. But in the great majority of observations it was accompanied by chasing heroin, while cocaine chasing remained a common mode as well. Transitions from chasing to injecting and vice versa were also observed. In the following, these cases will be presented.

Transitions from Smoking to Injecting

During the fieldwork some research participants seemed in a transition phase from chasing to injecting. In this period they seemingly spent more time with IDUs and some tried to hide the fact that they injected for (non-injecting) peers. Freek, the subject in the following fieldnote, had been chasing for five years. He told that recently he started dealing to finance his habit. He was observed in a house where many IDUs live. It is one of the few house addresses where injecting is allowed and the house was visited by large numbers of both chasers and IDUs. At the time of observation he was not dealing, which may explain his transition to injecting in terms of drug availability:

A little later Freek wanted to shoot up. He asked everybody to soften their conversation. "I need a little rest around, otherwise I can't fix up and I don't want all the clients to see me shooting up." He said. "I didn't know you are shooting." Ronald asked "I thought you only chased your dope?" "I do both." Freek replied.

Freek asked for some silence so that he could concentrate on injecting. Apparently this was not a routine procedure. Lacking skills and experience, injecting was a stressful activity, as the rest of the observation shows:

Freek tied an electric wire around his right arm and searched for a vein. With his forefinger he tensely palpated his skin. It took him some time to locate a suitable vein. More than once he took up the syringe but hesitated and put it back on the table again. He changed the wire to his other arm and repeated the procedure. Then he found a good spot and inserted the needle.

In the next observation neophyte arousal is also evident:

Abdul asks Mohammed if he wants to help him setting the shot. Mohammed only wants to help him binding off his arm and finding a suitable vein. Abdul tells that this is maybe the tenth time he takes a shot, "I'm not so good at it yet". After pricking 5 times he manages to get into a vein. They are both pretty excited. Mohammed from the cocktail (he had already injected) and Abdul from the attempt to shoot, and they start to quarrel. Mohammed says he shoots much longer (about 6 months) and so he knows what he's talking about and knows how to do it best.

The transition from chasing to injecting is made for a variety of obvious and less obvious reasons --often in combination. Some chasers only smoke heroin combined with cocaine because they dislike the taste of heroin alone:

"I'm out of cocaine and I don't like to chase the heroin pure. I can't stand the taste, it's so dirty."

This man, a long time user who stopped injecting because he ran out of accessible veins, sniffs his heroin when he does not have cocaine available. A strong dislike of the heroin taste may be a reason to initiate injecting:

"I did chase when I started to use. But now I'm shooting. When chasing I had to throw up all the time. Almost every time I did it I got sick. It was quite an experience, shooting the first time, getting stoned without throwing up."

Other users need to hide their drug use, for example for their family. Chasing takes them too much time, which makes it harder to cover their use:

"Because I don't want my family to know about my heroin use, I can't use in the living-room. I always used the attic to chase the dragon. But it took me half an hour or more until I had smoked enough and could go down again. That made my family wondering what I was doing up there; what took me so long. Therefore I started shooting and now I can do it in 5 minutes."

Cocaine

Several statements of users and a considerable number of observations point at cocaine as a significant factor in the transition to injecting. The main reasons for initiating injecting, mentioned in this study were the faster and more intense effect. These reasons would apply to cocaine as well as heroin, but when explanations were given these generally referred to cocaine --Novice IDUs prefer shooting cocaine, above chasing or basing, because of the extreme 'flash' (rush). "Waugh, this is much better then smoking. Now you feel the flash right away", explained a user moments after he injected a cocktail. And another user explained: "Much better than the base-flash, it's the highest high you can get."

Frequently chasers start shooting cocaine, while continuing heroin smoking:

Billy asks Dirk what he wants. "Let's do coke first and then a cocktail", Dirk replies. ... Both shoot up without using a belt. Billy in the inner left arm. His arm is covered with needle-tracks. Dirk is shooting in his right arm. He has very little marks on his arm. When he is finished he takes the role of tinfoil that lies on the table, tears off a piece (± 15 by 7 cm.), heats it first, puts some heroin on it and starts chasing. "I'm only shooting now and then", he says, "strictly speaking I am a chaser."

Besides the intensified effects of (cocaine) injecting, the use of other drugs, in particular benzodiazepines may also play a role, as these can undermine internalized inhibitions. In the following excerpt Doug explains why he initiated injecting:

"You know me, have you ever see me shooting up, no never. Maybe some years ago I've tried it several times, but normally I always smoke dope. Now since 2 weeks or so I started shooting cocaine. This cocaine is so good, so after the first time I was sold off to it. It happened like this: I took a few, maybe three, Rohypnols. A friend of mine was here too, he said: "Hey man, try this (shooting), it's good cocaine". Doug continues: "Normally I wouldn't do it and keep refusing. But now, through the Ropies, I crossed the line."

In Doug's case the cocaine rush reinforces continuation of needle use despite negative information and knowledge. Other reasons for switching to injection include the high costs of chasing and basing cocaine. Paco, a ± 30 years old Moroccan user states:

"I am shooting mostly, sometimes I chase. I learned it from another Moroccan. I shoot every day, sometimes one a day, sometimes 10 a day when I have enough money or dope, especially cocaine. Cocaine I always shoot. Basing is too expensive and it takes too long. When you shoot you feel the flash right away."

Cultural Barriers to Injecting

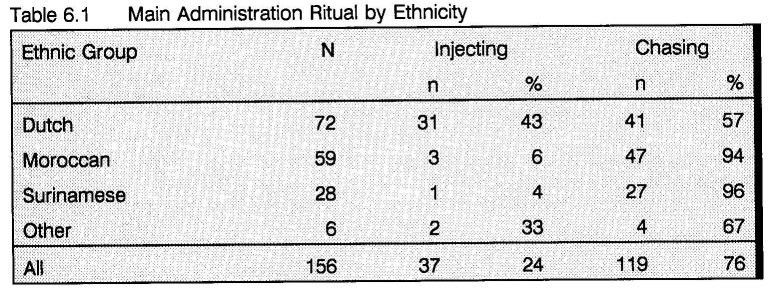

Table 6.1 presents the administration rituals for the different ethnic groups in the study. The table indicates that the prevalence of injecting among minority drug users is very low. Other Dutch studies found similar distributions (1). During the fieldwork only one Surinamese male was observed injecting in a group of white Dutch IDUs. Injecting in Surinamese groups was not observed. Injecting drug use is highly disapproved of in the Surinamese community. Therefore, Surinamese users will normally conceal their injecting drug use, which may result in an underestimation of actual injecting prevalence.

Although such disapproval may be less strong among Moroccan users, injecting Moroccans will normally also hide their injection drug use for non injecting peers. Prior to the observation of the two novice Moroccan IDUs (Abdul and Mohammed) presented above, these young men picked up 2 new syringes in the shelter next to the Central Station, but first one of them went in to look if there were no acquaintances or other Moroccans in the shelter. He explained: "I don't want them to know I'm shooting, but we were lucky as there was no one in."

The reasons for not injecting among minority users may often seem rather idiosyncratic. Such as Shaffy's --a 22 years old Moroccan:

"Although I was always with friends who were shooting, I never started. I tell you why. Three years ago I had to do some blood tests at the CAD (methadone program). I went into the doctors room, but had to wait because the woman was still busy taking blood from another. So I could watch her doing it. And man, she really made a mess from it. As if she did it for the first time. She was really stirring the needle in his arm to find a vein. The man was hurt by her for minutes. I first wanted to leave, but it was my turn already. She messed me up as well and it really hurt me. This cured me from the lust to shoot for ever. And then, shooting up is bad for the veins."

Such accounts may, however, well be expressions of specific socio-cultural inhibitions. Nadir, one of the Moroccan key respondents explained the low prevalence of injecting drug use among his compatriots in terms of religious blood taboos:*

The majority of the Moroccans are not acquainted with the shooting ritual and its paraphernalia. If they have ever seen a syringe, it was at a doctor's practice. Many of the Moroccan users come from Berber or other rural areas, where experience with doctors is rare. The doctor and his symbolic instrument --the syringe-- are fearfully respected.

This may well be a folk religion interpretation of the islamic (and Jewish) taboo on the consumption of blood --exemplified in the practice of ritual slaughter in which animals are bled dry before further processing (2). In the described Berber version of 'popular Islam' the scope of this basic rule of conduct seems thus extended to medical syringe use, perhaps encouraged by rivaling traditional healers. Imported by Berber immigrants and adapted to the situational requirements of the drug scene this taboo may well function as a cultural threshold for injecting, as was explicitly suggested by Nadir:

"According to this 'blood myth', evil spirits are attracted to blood and the devil has power over the blood. In Morocco this belief is so deeply rooted, that some people fear and might even try to escape from a doctor or hospital injection. In The Netherlands these Moroccans hear that injecting drugs produces all kind of diseases. To them, this is proof that the devil has been involved through the blood."

Van Gelder and Sijtsma also pointed at the religious meaning of blood as a reason for the Moroccan aversion of injecting (3). Mindful of Nadir's account, the following conversation between two Moroccan users was witnessed later during the fieldwork:

"Why don't you start shooting?". The boy replies, his face looking ugly: "Shoot- ing? That's filthy, very filthy. I will have nothing to do with it. You know on some addresses you find for instance an ashtray full with blood. Bah, it makes me feel sick, even when I talk about it now. I don't want to have anything to do with blood, I stay away from it as much as I can. You get diseases from it, you heard what's happening with AIDS. I will never start shooting, it's dangerous."

Surinamese users are also believed to maintain a taboo on injecting which, supposedly, is rooted in 'Winti' --a popular Creole folk religion (4). This study established some support for this assumption. At one of the frequently visited places where a group of older white Dutch IDUs lived, one day Sheep, a 35 - 40 years old Creole Surinamese man had moved in. Although all other residents and many of the visitors were IDUs, and while almost at any moment there was somebody injecting, Sheep restricted himself to smoking. A few times he was observed making disapproving remarks to people injecting. "I'm proud of my body.", he explained his aversion for injecting. Although the other Surinamese ethnic groups (Hindustani, Chinese, Javanese) may not share the Winti religion, the taboo on injecting is often shared.

In spite of such assumed protective cultural factors an increasing number of Moroccans and Surinamese do start injecting, which, according to users themselves, seems mainly associated with cocaine use. A trend already signalled by van Gelder and Sijtsma (4). During a visit to a dealing address the following discussion was observed after Lottie, a Surinamese female dealer had just served two white Dutch IDUs:

When the IDUs are gone Lottie says: "Shooters, always in a hurry." ... The other Surinam woman says: "it's a matter of how you take care of your body, I simply want no spike in my body, I hate it. You know, people start to shoot when they feel they don't get enough out of chasing anymore. But "we Surinam people" don't like spikes in our bodies." Lottie says: "That isn't the case anymore. More and more Surinam users start to shoot, they go for the coke flash. This happens more and more. I don't want to have anything to do with shooters or 'pill freaks'."

For a considerable number of Moroccan users, some additional factors may further reinforce the initiation of injecting. These users have problems complying with Islam standards or family and community obligations and are for that reason thrown out of the house and ostracized by the community. Often homeless they gather around the central station and in shelters for homeless men. There they have more contact with native Dutch users and especially with older IDUs. Diffusion of the injection ritual may have started with these contacts. In addition to contacts with Dutch IDUs, diffusion of injection has occurred through contacts with groups of Moroccan users who travel from countries where heroin injection is the dominant administration ritual, such as France and Belgium.

Transitions from Injecting to Smoking

Transitions can also be observed in the other direction. For example, some users stopped injecting because they tried to regain control over their drug use and their life in general. Another user ceased injecting in prison. After he was released he started using heroin again, but this time he smoked. Social pressure seems an important factor. One IDU, started working as doorman with a group of smoking users, who did not want him to inject:

"I stopped shooting up two days ago", he tells, "cause it is better for me. It's not easy but they're helping me very good. I quit kinda radically ..."

Three weeks later he was out of work again:

"I'm shooting up again", he says, "I'm also chasing, but now that I don't work anymore, I use less dope and that's why I shoot it."

It seems that both economic considerations and group rules (peer group pressure) influence the mode of administration.

Harrie, the older IDU mentioned before, also tried to stop injecting. He had multiple reasons. Observing him, it became clear that he had a hard time finding a vein. Often he was bleeding from all limbs when he finally got off. After more than 20 years of injecting there were few accessible veins left. Furthermore, his new girlfriend was opposed to his injecting. Last but not least, injecting cocaine became hard to control. This seemed a major reason for Harrie:

"For a couple of days I started to smoke cocaine (from aluminum foil). I find it more cozier, more relaxed. And I feel I'm more in control too, when I'm shooting I keep on going on. One after the other."

Although he really tried, Harrie was not able to stop injecting permanently. For about a month he actually injected much less and during this period his veins got some rest and became more accessible again when he tried to inject.

Difficulties with injecting is a common problem among longtime IDUs. Due to a history of poor and unhygienic injection technique, most veins have collapsed, are covered with scar tissue and have become inaccessible:

He ties off his right arm above the elbow. He tries four spots before he hits a vein. The first spot is on his inside of the underarm, somewhere in the middle between hand and elbow. He moves the spike around under the skin, digging for a vein. Blood drips on the carpet. A second attempt is made somewhat closer to the elbow and a third on elbow height. Both fail. The fourth attempt --just above the elbow-- is successful. "Well finally, I am having more and more troubles with my veins." He pushes only half of the contents in the vein and boots three times, while the solution in the barrel gets bloodier. Then he empties the barrel. When he boots again, he looses the vein. He digs around, manages to get the needle back in and boots again. Again he looses the vein and tries to get it back in, but in vain. Finally he stops and takes the needle out of his arm. He has been busy for four minutes.

Some IDUs were observed digging in their arms and legs for periods up to two hours. Often they try one site after the other without loosening the tourniquet, so that they bleed from many wounds. Despite the pain, stress and 'blown shots', most of these older IDUs postpone stopping until all their veins are gone. Prior to this moment they often initiate chasing as a secondary route --when injecting fails, or to temper arousal and improve concentration in advance of an attempt to inject. But sooner or later they are confronted with the inevitable choice, as becomes clear from Patrick's account. After injecting for 20 years, Patrick reached his limit and finally stopped injecting:

"I stopped shooting up simply cause I could not get a 'hit' anymore. I have been shooting up for 20 years now. In the end I wasted three shots on one 'hit'; the solution coagulated or the needle clogged and I got sick of the mess, ... all the blood and the pain. I shot in my fingers, I tried all places. At last it hurt so much I got tears in my eyes. I added coke to the heroin, not for the kick but to relieve the pain."

Just as for Harrie, terminating injecting was not easy for Patrick:

"When I stopped shooting up and started chasing I had to use more to meet the gap in effect. In the beginning it was hard, I missed that certain feeling, you know."

What Patrick missed is made clear by Harrie, when he explained why he relapsed into injecting again:

"I can't control it, I just keep on going. (...) When I was chasing I was waiting for the flash to come, or something. I kept on smoking and thought: where is it, when does it strike me. I missed the flash. I've always been a heavy user. When I took drugs, I took a lot so I would really feel it. That's what I'm missing when chasing."

In general, the observed rituals are fairly stable --most users tend to stick to their ritual of preference. Other Dutch studies found similar results (1, 5). Although economic incentives (drug availability) play a major role, the choice for a ritual is also determined by several other social and personal factors, which are subject to change. Such choices are for example influenced by personal health and group norms. For long time injectors the condition of their veins becomes increasingly the main determinant of the choice whether to inject or not. At some moment they have literally used up their veins and injecting stops being an option. The decision to terminate injecting is postponed as long as possible, only making the problem worse. Prior to this moment the injecting frequency decreases and is supplemented by chasing. When moving from a network with a dominant smoking norm into an injection oriented network, injecting becomes a serious option. Not only because of social pressure, but also because it may yield certain economic benefits, e.g. when sharing drugs. Sharing drugs is a common activity both among smokers and IDUs (see chapter nine), but they engage in different sharing rituals (dividing powder v.s. solution). Conversely, when an injector associates with a group of smokers, for example when accepting a job in a dealing collective, injecting may be terminated to avoid social disapproval or simply because it is proscribed. Nonetheless, again these social pressures cannot be detached from the economics. Besides the drug sharing aspect, the increased access to drugs will assuage terminating injecting.

- Korf DJ, Hoogenhout HPH: Zoden aan de dijk: Heroinegebruikers en hun ervaringen met en waardering van de Amsterdamse drugshulpverlening. Amsterdam: Instituut voor Sociale Geografie, Universiteit van Amsterdam, 1990.

- Wagtendonk K: Grondslagen van de Islam. In: Waardenburg J (ed.): Islam. Norm, ideaal en werkelijkheid. Weesp: Het Wereldvenster, 1984: 97-122.

- Gelder PJ van, Sijtsma JH: Horse, coke en kansen: Sociale risico's en kansen onder Surinaamse en Marokkaanse harddruggebruikers in Amsterdam. II Marokkaanse harddruggebruikers. Amsterdam: Instituut voor Sociale Geografie, UvA, 1988.

- Gelder PJ van, Sijtsma JH: Horse, coke en kansen: Sociale risico's en kansen onder Surinaamse en Marokkaanse harddruggebruikers in Amsterdam. I Surinaamse harddruggebruikers. Amsterdam: Instituut voor Sociale Geografie, UvA, 1988.

- Grapendaal M, Leuw E, Nelen JM: De economie van het drugsbestaan: Criminaliteit als expressie van levensstijl en loopbaan. Arnhem: Gouda Quint, 1991.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|