DRUG CULTURE AND DRUG POLICY: IMPLICATIONS FOR FUTURE DEVELOPMENTS

| Books - Drug Use as a Social Ritual |

Drug Abuse

DRUG CULTURE AND DRUG POLICY: IMPLICATIONS FOR FUTURE DEVELOPMENTS

Traditionally, interest in the factual description of the behaviors involved in drug taking and the concrete social context in which these behaviors take place have been minimal. The advent of the HIV epidemic among injecting drug users (IDUs) painfully bore the consequences of this negligence. The present research, while not instigated by concerns for the spread of HIV, is certainly relevant to this issue. The study was directed at the indepth ethnographic description of the drug taking behaviors of regular users of heroin and cocaine. It aimed to reveal the functions and meanings of these specific behaviors for the individuals and groups involved in their regular use. Furthermore, the research examined the possible (public) health implications of the behaviors under study and this is where the connection with the HIV issue is made. In addition the research should shed some light on factors that determine (aspects of) these behaviors. In particular (social) factors that can be subjected to (policy) interventions were of interest. Thus, the project started with fairly general research questions, which have been specified along the analytical process (1) to those presented in chapter 3.2.

A fundamental assumption of this research has been that, while the studied behavioral sequences have a functional basis, their functions and meanings extend beyond this pure instrumental functionality. The observed behaviors were thus expected to serve specific instrumental functions in the process of procuring drugs and introducing these into the body, as well as symbolic and social functions and meanings, both for the individual performers and their social networks. These complementary perspectives have been operationalized using the concept of ritualization. Chapter two provided an overview of the literature concerning ritual, its application in studies of drug use behaviors and of the factors that can be regarded as conditions of ritualization. This overview suggested a combination of economic (scarcity) and socio-cultural (subculture) factors as a main determinant of ritualization around drug taking. It furthermore suggested that these same factors are also of central importance to the issue of self-regulation, i.e. whether drug use is controlled or uncontrolled.

Thus, the present study took a microscopic look at the daily drug taking rituals of regular users of heroin and cocaine and described the functions and meanings of these drug administration rituals in terms of pragmatic utility and social effects, e.g. group coherence. As the study went along, the importance of the concept of availability became increasingly clear. The preponderant influence availability plays in the daily lives of the study participants is perhaps the most conspicuous and consistent finding of the study. Actually, this is neither surprising, nor new. A serious contention is that the reduced availability of drugs resulting from prohibition constitutes the essence of the drug problem society currently faces. (2 3 4 5)

Whereas ritual is the basic element of culture, this final chapter will address the impact of reduced availability on the level of the compound --the drug using culture itself. It will attempt to reveal some of the general processes involved and for that reason this discussion will not be limited to heroin, but also consider the cultural developments around two other drugs -- cannabis and MDMA. The current state of affairs of Dutch policy will be assessed for its impact on the developments around these different drugs. The ultimate aim of this chapter is to explore new directions for drug policy and practice, building on the successes of the Dutch normalization policy.

Drug Availability, Ritualization and Culture

Drug Availability: A Decisive Factor

Availability is at the root of individual choices for either chasing or injecting. Many of the observed transitions between administration rituals (see chapter six) were related to availability problems. Availability has also been a main determinant of the subcultural transition from injection to chasing as the dominant administration ritual for both heroin and cocaine. The combination of a stable and relatively high heroin quality on the Dutch illegal drug market and the easy availability of methadone provided an essential condition for the chasing ritual to thrive. (6) Availability can also play a role in cocaine related problems, such as loss of control and the initiation of injecting (chapters five and six). Cocaine's intense, but short lasting euphoric effect and the subsequent crash often result in high frequency administration schedules of sometimes every twenty (or less) minutes. Thus, while it may be just as easy to purchase as heroin and sold for approximately the same price per unit, the subjective or perceived availability of cocaine is for most of the observed users much lower than that of heroin.

As a result of the generally unrestricted availability of syringes and needles, standardized needle sharing patterns have not developed in the Netherlands, preventing the addition of special meaning to such acts (chapter thirteen). As a result, most IDUs perceive needle sharing as an inexpedient, or even deviant act. This does not mean that needles are never shared. But in the few observed cases of needle sharing a strong link with situational (un)availability of needles could be established (chapter twelve). In contrast, standardized drug sharing patterns did develop, as a result of a structural low availability of the drugs preferred by the research participants. Drug sharing was found to be highly ritualized and surrounded by elaborate subcultural rules (chapter nine). Sharing drugs is of course not limited to the participants in the present study, but rather a common feature of many formal and informal gatherings within various social groups. Both from a historical and a geographical perspective there are probably few societies where drugs do not play, or have not played, a role in social ritual. (7) Illegal or not, sharing drugs brings people together and strengthens their mutual ties. Therefore, it was argued that drugs have intrinsic or primary ritual value. But, whereas drug use and social ritual have a strong and historical relationship, the significance attached to the drug sharing ritual by those involved --the intensity of ritualization-- varies with the availability of the drug. While there is little principal difference between offering a guest a cup of coffee, a cigarette, a beer, a cannabis joint or a taste of heroin --all are directed at smoothening interactions (8 9)-- the social meaning of the latter is of a much larger magnitude.

Clearly, drug availability plays a crucial role in the construction of this social meaning. Submitting drugs and their users to economic and social repression, with the inevitable result of a reduced drug availability beyond the users' control, can be seen to have a series of definite consequences:

- It increases the economic value of the drugs. Increased economic value not only works as a strong stimulus for the formation of an illicit market intertwined with a subculture of users, but also translates into economic pressure towards more efficient administration rituals.

- It increases the ritual value of the drugs, which turns the ritual object and its utilization into an attractive and effective symbolic object of subcultural identification.

- Reduction of drug availability furthermore induces uncertainty about the probability of obtaining the ritual object, and thus about whether the ritual event may take place. This promotes opportunistic (unsafe) use patterns. Because the reduction of uncertainty and anxiety is a main function of ritual this uncertainty further increases the significance of the ritual performance. (10)

The overall result of these developments is a narrowing of focus and interest, as well as a severe reduction of behavioral expressions of the users. They will direct the major part of their activities towards realizing the performance of the drug use ritual. They will fixate on and cling to its undisturbed performance and the ritual will be narrowed down to its core functions --getting high and safeguarding this activity. This process not only has an impact on the individual users, but also determines the norms and orientation of the subculture.

Availability and Cultural Orientation: Survival or Progress

In his analysis of peasant life, John Berger provided an interesting framework which reflects the dynamic relationship of ritualization and availability and its impact on culture. Peasant life shares some remarkable similarities with that of the drug users reported on in this dissertation. The peasant is committed completely to survival and "whatever the differences of climate, religion and social history, the peasantry everywhere can be defined as a class of survivors". (11) The peasantry is a self-supporting economy within an economy which makes it, to some degree, a class apart on the frontier of the formal or mainstream economic-cultural system. "They maintained or developed their own unwritten laws and codes of behavior, their own rituals and beliefs, their own orally transmitted body of wisdom and knowledge, their own medicine, their own techniques and sometimes their own language." (11) Peasants and drug users share a decisive economic consciousness which determines their actions and can result in a highly opportunistic attitude. But in order to survive, they must resort to "mutual fraternal aid in struggling against ... scarcity and a just sharing of what the work produces". "When peasants [and drug users] cooperate to fight an outside force, and the impulse to do this is always defensive, they adopt a guerrilla strategy --which is precisely a network of narrow paths across an indeterminate hostile environment." (11) As with the drug subculture, the peasantry's relation to the dominant culture, can therefore be characterized as heretical and subversive. These analogies are even reflected in their similar reputations. The drug users' equivalent of the peasants' "universal reputation for cunning", (11) is portrayed in terms such as "extremely egoistic cannibals" who "lie, steal and manipulate their fellow human beings" due to a "junkie syndrome". (12 13)

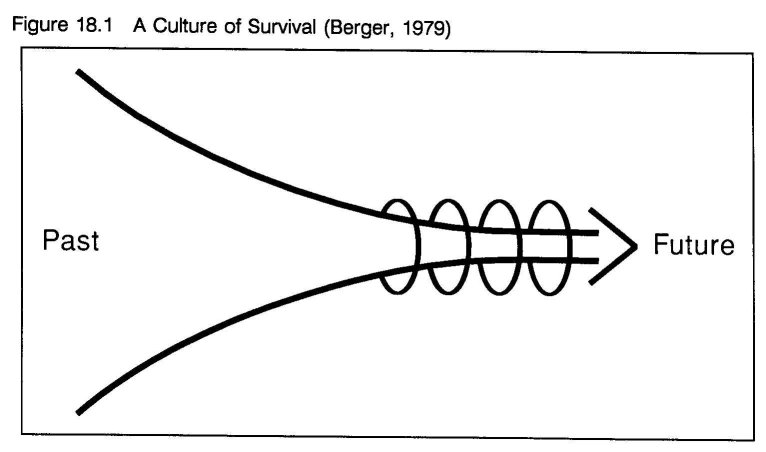

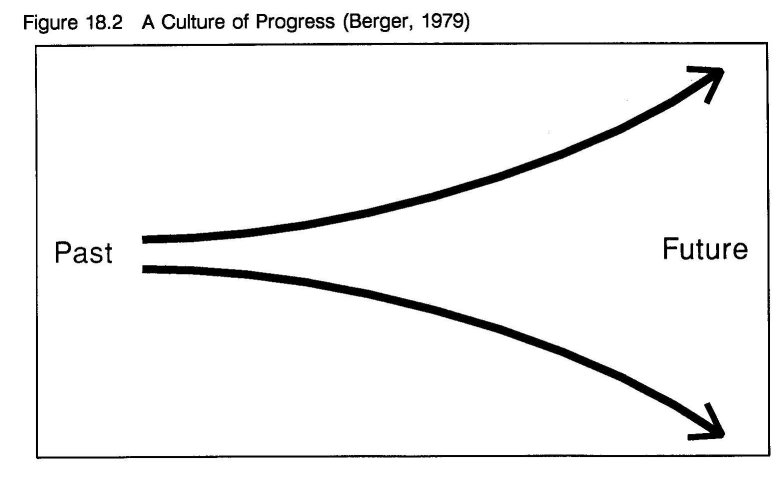

The essence of peasant life, Berger explains, is dealing with scarcity (hunger) and insecurity, without prospect of improvement, by following a narrow path of tradition. "A class of survivors cannot afford to believe in an arrival point of assured well-being. The only, but great, future hope is survival." (11) Peasant culture can therefore be described as a culture of survival. "A culture of survival envisages the future as a sequence of repeated acts for survival. Each act pushes a thread through the eye of a needle and the thread is tradition". (11) In other words, in dealing with reality and the future, one relies on the repetitive and routine performance of a specific class of practices. Exactly those practices that have demonstrated, time after time, to (temporarily) alleviate scarcity, and bring about survival of both the individual and its culture (see figure 18.1). Beyond survival only uncertainty exists, as this falls outside of ones control. Berger contrasts the culture of survival with, what he calls a culture of progress. "Cultures of progress envisage future expansion. They are forward looking because the future offers ever larger hopes. ... The future is envisaged as the opposite of what classical perspective does to a road. Instead of appearing to become ever narrower as it recedes into the distance, it becomes ever wider" (see figure 18.2). (11) The resulting spectrum of feasible and opportune behaviors becomes more diverse, while their ritual value decreases.

A cultural continuum

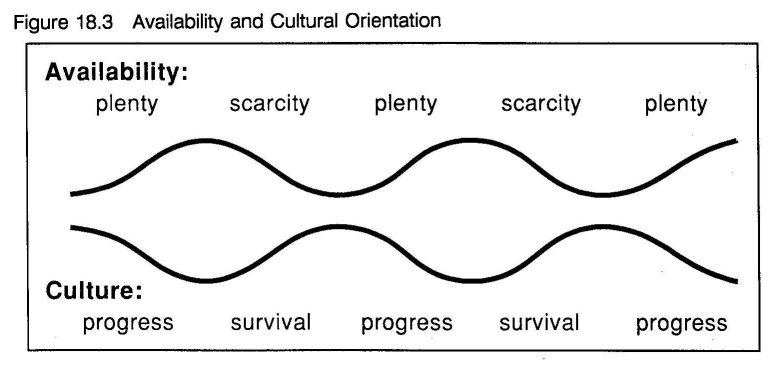

While Berger presents the two cultures as a dichotomy, mirror opposites of one another, the accuracy of this representation is questionable. Culture is probably more veraciously envisioned as a continuity, a flow from past to future, in which the labels survival and progress represent reversed positions which depend on availability (see figure 18.3).

In periods of scarcity the culture goes back to the basics and refrains from activities which surpass the biological goal of survival, whereas in periods of plenty activities diversify and the goal of survival becomes more remote. Inevitably, this has important consequences for the daily activities and commitments and thus for the life structure of those involved. With regards to pattern and function of rituals (and rules) one can observe in periods of scarcity a declining number of participants in the ritual with closer connections, and an increasing meaning attached to the ritual object and the (undisturbed) performance of the ritual. In contrast, in periods of plenty the number of participants (with less intimate connections) increases, while the meaning attached to the ritual object and to participation in the ritual decreases. Ultimately the ritual object becomes de-ritualized and stops being the instrumental imperative (14) of the culture, which itself has progressed into a stage of dissolving into a larger culture.

An illustration: The Dutch Cannabis Culture

An interesting illustration of this process is found in the recent history of cannabis use in The Netherlands. While cannabis use was not unknown before, during the 1960s the drug became more widely available in the upcoming middle class hippie subculture. (15) This counter-cultural movement was experienced as a serious threat, not only because of its illegal drug use, but also because it questioned the establishment. In response use of cannabis (and other drugs) was problematized and repressed. As a result, smoking cannabis became a symbolic act of resistance, invested with symbolic meaning, uniting adolescents and young adults, who shared the hippie philosophy of life. The fact that use and consumption dealing of cannabis became a focus of law enforcement only reinforced this process. Elaborate smoking rituals could be observed (dimly lit rooms, specific music, candles, incense, sitting in a circle passing the water pipe, chillum, or joint, etc.). The drug was surrounded by a detailed argot, which leaned heavily on imported American slang.

The contra-productive effects of repressing cannabis use were quickly recognized in the early 1970s and a more tolerant policy developed. With the revision of the Dutch Opium-act in 1976, possession of cannabis for personal use (30 grams or less) has been decriminalized in the Netherlands. Since then the availability has increased considerably as an open coffee shop based market developed. Nowadays, use of cannabis is no longer associated with a deviant subculture, while the hippie subculture was absorbed into mainstream society during the 1970s. Ritualization has decreased significantly and rapidly. Smoking cannabis is almost completely normalized in the Netherlands and users can be found in most social strata. (16) One can smoke a joint in most public environments without risking police harassment. Cannabis has become readily available and is sold in semi-legal, so-called, coffee shops --to the Dutch more and more a normal offshoot of the retail branch, for many foreigners still a strange novelty and a tourist attraction. (17 18) The Dutch generally mix cannabis with tobacco, while more potent ways of administration (water pipes, chillums, hot knifing) have become obsolete. Using a roach clip to hold the butt as it burns down, and saving and rerolling the butts --a typical American ritual-- is unknown among Dutch cannabis users and considered an oddity:

"An American friend who visited me recently, offered me this little plastic bag as if it was an important present." He shows a little zip-lock bag, containing four to five grimy reefer butts. "He said he did not dare to take them on the plane home. It seemed he had a hard time forsaking them. I kept the bag as a funny, but dirty, memento."

The marihuana leaf, which, featuring on clothing and jewelry, used to be an explicit style symbol of cannabis users in The Netherlands, has not disappeared, but it has diffused to many non-users, thereby loosing its ritual binding force. (19) This does not mean that all ritual behavior surrounding cannabis use has ceased to exist in Holland. It may well be observed among new, unexperienced users, most likely in the period during and shortly after initiation. After all, rituals have an important educational function. (20) Likewise, many experienced users perform and enjoy idiosyncratic rituals when making a handsome and perfectly smoking joint. But the functions of these stereotypical behaviors have changed. Little symbolic elaboration remained, while social goals have faded. The remaining solitary rituals are principally practical. They focus at the task at hand and prepare the user for getting high. Once of great importance, many symbolic behaviors have lost their function --they have become "empty rituals". Nowadays, the social symbolic meaning of sharing a joint largely parallels that of sharing a tobacco cigarette.

Back to the Heroin Culture

The cannabis example provides an indication of the different ritual patterns determined by varying levels of availability associated with social and economic pressure. While similar variations in the intensity of ritualization in the heroin culture are often not so clear cut, a comparison between Rotterdam and the Bronx (chapter sixteen) established several differences in ritual patterns, especially around use and consumer level transactions, which underline the significance of availability. Within the Dutch heroin culture itself such variations can also be observed. Although the overall frequency of drug sharing in the two groups differed little, the drug taking and sharing rituals of many (older) IDUs seemed considerably more formalized than those of chasers. Sharing among chasers generally took a casual and opportunistic form, while IDUs' drug sharing seemed confined to smaller circles, epitomizing stronger social bonding. The subcultural transition to the softer and less harmful chasing ritual is perhaps the strongest indicator of the power of availability. (6) The sequential and gradual character of chasing results in a rather stable intoxication, which limits the contrast between being sick and high (nodding), characteristic of injecting. A contrast, which perhaps is important in explaining loss of control. (21) The absence of this compulsive contrast, in turn, limits the importance of, and fixation on, the event. Other behaviors become more feasible and the overall behavior pattern is less directed at survival.

The Dutch Heroin Culture: A Culture in Transition

Thus, in terms of the above suggested cultural continuum, the Dutch heroin culture can be envisaged as being in transition --from a culture of survival (of which it still has many aspects) to a culture of progress, in which the heroin ritual is loosing much of its symbolic power. In a true culture of progress the drug may still be used, but instead of becoming the paramount determinant of behavior it will be part of a diversified pattern of behavioral expressions. In such a pattern heroin use is challenged and balanced by other determinants of behavior, fostering self-regulation processes that support controlled use. Little research has been conducted into this cultural transition hypothesis. However, one English study suggested lower dependency levels associated with chasing. (21) Likewise, the higher degree of self- regulation among (Surinamese) heroin/cocaine dealers reported in the previous chapter and the subcultural transition from injecting to chasing in the Netherlands (6) are also in line with this hypothesis. Furthermore, anecdotal observations of the relative ease with which later generations of heroin users seem to (permanently) kick heroin, (22) and the recent anecdotal reports from Amsterdam on controlled heroin smoking among young Moroccans (23) also point in the hypothesized direction.

New Drugs, New Rituals, New Cultures: the Example of XTC

The Cultural Setting

The recent emergence of MDMA (XTC or Ecstasy) provides an interesting example for comparison, as it is not yet contaminated by the influence of years of drug policy. While in the Netherlands the drug was not completely unknown before, in 1987 MDMA use emerged on a larger scale. Although also used in other (private or (semi-)therapeutic) settings, the use of MDMA has mainly been associated with the youth culture that has formed around house music, or shortly House. This new style of dance music originally emerged about 10 years ago in the Chicago gay scene and has developed into a highly successful international music scene. Just as Rock and Roll and Punk, House rebelled against the established (popular) musical culture and induced international cultural change far beyond the music. Its influence is noticeable in fashion, art, architecture and the socio-political attitudes of large groups of adolescents. In the beginning of 1987 House became popular within the incrowd of Dutch clubbers, and rapidly became popular in larger groups of young people. As the introduction to a recent Compact Disc release explained, "House is made for the dance floor, with sizzling rhythms, pumping basslines and little or no melody. ... People are going wild to extreme dance music, dressing extravagantly and having a wicked time." (24) "House Parties" or "Raves" are all night dance events that emphasize a total dance environment using state-of-the-art disco high technology (light-shows, stroboscopes and smoke machines). (25)

Whether on MDMA (or other drugs) or not, attendants may experience a "good" party as a revitalizing ritual. The Dutch musicologist and House musician Gert van Veen described House as follows:

"It is a musical experience that goes back to primeval age. Music as magic, as a means to reach a higher state of consciousness. The dance marathons are a ritual, in which the disc jockey acts as a wizard. Records are the ingredients of his hallucinating potion, with which he leads his audience to a liberating catharsis." (26)

At some parties visited in 1989 turn table wizards carefully controlled the atmosphere at the dance floor and they were able to incite communal maslownian peak experiences in which the whole dancing crowd turned wild --squealing, blowing whistles and laughing. (27) Upon his first introduction to a dancing and sweating crowd at a House Party, Bilu, a civil engineer from Kenia said "Man, this is tribal!". (28) And indeed, a house party does resemble a tribal celebration. Furthermore, the house tribe carries its own specific style symbols, e.g. clothing and jewelry, which are remarkably similar to those of the 1960s hippies. The tribe has also developed its own argot. (29 30)

The Drug and its Users

The use of MDMA spread simultaneously with House. A development which may well be stimulated by the extensive media hype, connecting the two. (31) MDMA has reached both new users with minimal or no drug experience and users with a varied experience with other illegal drugs. Both groups mix in the modern entertainment circuits. (25 31 32) In 1992 it was estimated that in Amsterdam approximately 10.000 people have ever tried the drug. (31 32 33) MDMA is now sold in various, at consumer level separated, markets (night clubs, discotheques, friendship groups pooling money) but is also part of the (tourist) street poly drug markets of Rotterdam and Amsterdam. Generally, the drug is orally ingested and its use has not yet been a reason for alarm. (25 31 32) Was the drug previously imported into the Netherlands --e.g. from the USA-- large busts in February 1992 and subsequent periodical publications indicate that the (illicit) Dutch amphetamine industry has broadened its market share and is producing large quantities of MDMA, which for a large part is intended for the seemingly ravenous British consumer market. (34 35) Recent anecdotal reports suggest that the incidence of MDMA use is still rising, while the drug has become accessible to new user groups. Drugs such as "magic mushrooms", LSD and amphetamine may also have gained in popularity, but it is too early to speak of a definitive trend. (36 37 38)

Interestingly, while drugs play some role of importance, House is not a closed drug centered subculture in the Netherlands. Although there is a cultural core of House Freaks, almost all social groups are represented at parties. (25 31 32) The key identity indicator of the cultural core is not the drug, but the music and perhaps the fashion. The common denominator seems to be the lust for endured trance dancing. Heterogeneity is also typical for the Dutch XTC users. Most users are in their twenties and thirties, have urban lifestyles, comparably high education levels and seem well tied in non drug dominated networks, activities and interests, such as work or study. (31 32)

XTC and Self-Regulation

Observations of XTC use of the last three and a half years indicate that the controlling strategies applied by XTC users initially leaned heavily on rather strict and idiosyncratic group rituals. But surprisingly rapidly these rituals seem to have been replaced by more generally applicable rules. (39) Adelaars suggested that users with prior illicit drug experience apply this experience to regulate smoothly their XTC use, whereas virgin users apparently find more difficulties in doing so. (31) Apparently, these experienced users adapt established and internalized rules to a changed (drug) situation, which seemingly gives them an advantage over users, whose MDMA use is the first experience with illicit drug use. Harding and Zinberg described similar processes among cannabis users in the USA, who adopted alcohol rules to their marihuana use. (40) Drug information programs are regularly approached by (potential) users in search of information about XTC. In response, the Amsterdam Jellinek Center and the National Institute on Alcohol and Drugs (NIAD) have both produced folders with objective and balanced information about the drug, including rather specific instructions for safe use. From a harm reduction perspective, this is a most sensible approach.

Considered in terms of the feedback model it can be assessed that the level of repression of XTC consumers and consumption level transactions has until now been rather low, resulting in a comparably high availability. XTC can be purchased at a reasonable price without much difficulties, or intensive involvement in criminal subcultures. This allowed for the development of rituals and rules aimed at safe and controlled use instead of concealing and safeguarding the use of the drug itself, for example through the formation of a closed subculture. Moreover, information on XTC and instructions for safe use are available not only via peer communication channels but also from established institutions. The drug has even been a regular topic in the pages of Achterwerk, a national radio and television weekly's readers' mail feature for children and youth. In this, alongside letters about e.g. familial conflicts, friendship, sexuality and pets, experiences with and opinions of the drug, are openly discussed. This has greatly facilitated the formation, and widespread acceptance of rules for safe use. The degree of life structure of most current XTC users seems to be relatively high and largely determined by non drug related contacts and activities. XTC is mostly taken within the confined context of recreational activities --whether this is at a House Party or at home with friends-- and part of a differentiated pattern of activities. In comparison with the heroin culture, the Dutch XTC culture (if one can speak of one) is a culture of progress. While the drug is an ever interesting conversation topic (price, contents, effects), this is merely recreational dope talk and only one of the many subjects when users meet. The drug is not the instrumental imperative (14) of the house culture, but merely an adjunct in a rather hedonistic pursuit of pleasure and social identity. Given the conditions set by Dutch drug policy, this situation was not really unexpected. (40 41)

At this point three Dutch drug cultures have past in review. The cannabis culture, which basically has seized to exist. (42) The heroin culture, which is becoming less oriented at survival and differs explicitly from its foreign counterparts on some important parameters. While there is little research available for thorough comparison, (41) it seems that the Dutch XTC culture is significantly more integrated in mainstream society than, for example in the United Kingdom. In Britain ravers are driven into an underground subculture, while the prevalence of XTC use has increased much faster than in Holland. British XTC users seem to have much higher use frequencies and taking several tablets a night is not exceptional. (43 44) Sensationalistic media accounts suggest a high rate of problems, (35) while at least seven deaths have been associated with XTC use. (43) Apparently, the UK does not provide a climate in which rituals and rules for safe and controlled use can nurture. Although several British drug information centers aim to stimulate this process with sensible, well designed education campaigns, based on harm reduction principles (44), the following explanation of a British clubber in Amsterdam indicates that such efforts have to compete with repressive law enforcement, a tradition of poorly managed alcohol control and an, almost unanimously, sensationalist media discourse: (35)

"In London, it's like in the pubs shortly before eleven. Everybody tanks up before it is too late. With E it's just the same thing, lad. You better pop'em now, while you're having a good time. You may not get another chance. Tomorrow this thing may be all over, but who cares about tomorrow. Hear me? That's what I like about coming to Holland. Here people can have fun without the coppers chasing you, there is time to chill out. Take a break, you know. Here, ... people care about tomorrow."

Prohibition: An Arbitrary Phenomenon

These different cultural climates are the result of a dynamic societal interplay of forces, such as economic interests, (geo-)political priorities, social definition, (collective) social learning, (historical) development of social regulatory processes, scientific knowledge, which can all differ per country. The outcome of this proces is, of course, subject to change and may be taken as an expression of the human ambivalence towards the use of psychoactive substances. In spite of international (UN) treaties, there is no global agreement on which drugs are, or are not, acceptable. Nor has there been one at any given time. Furthermore, societies may change their opinions on certain drugs over time, and have, in fact, done so often. (45) From a historical perspective, drug prohibition is a relatively recent, but also arbitrary phenomenon. On the other hand, tobacco, coffee and alcohol have all known periods of prohibition or, at least strong moral disapproval. Louis XIV banned tobacco sales and pope Urban VIII excommunicated its users. (46) In some countries draconian punishments were introduced, e.g. the slitting of nostrils in Russia and the death penalty in Turkey. (7) In 17th century England, coffee was considered a dangerous drug and outlawed. (46) For many people the word prohibition is synonymous with the US' ban on alcohol at the beginning of this century. The following quote from Robert Hughes' The Fatal Shore, depicting life on a hulk (a 19th century English prison ship), not only provides a historical illustration of the variable process outcomes, but also presents a fine metaphor of the human ambivalence regarding drug use.

"I cannot help it, sir," he would say to the Captain. "Then I will cut the flesh off your back," the Captain would reply, and indeed the Boatswain used to do his utmost, for stepping back a couple of Paces he would bound forward with his arm uplifted, take a jump and come down with the whole weight of his Body upon the unfortunate victim, at every Blow making a noise similar to a paviour when paving the streets. At length the poor fellow (as I often heard him say) became weary of his life. He found that his blameless conduct in every other respect could not save him from the consequences of this trifling breech of discipline ... and from being one of the best he became the worst character in the Yard. When I left it, he was in the Black Hole for having bitten off the first joint of the finger of Mr. Gosling the Quartermaster, who had put it in his mouth to see if he could detect any Tobacco. (47)

The quote shows the great value people attach to the use of intoxicants and the trouble they are willing to undergo to maintain established use patterns when availability is restricted and use repressed. As Hughes wrote,

[t]he great emblem of desire and repression in hulk life, more than sex or food or (in some cases) freedom itself, was tobacco. Possession of tobacco was severely punished, but the nicotine addict would go through any degradation to get his "quid." Silverthorpe noted how this cycle of addiction and flogging broke prisoners down: "They grow indifferent ... they go on from bad to worse until they have shaken off all moral restraint." (47)

Under such repressive conditions, the use of a desired substance gains a symbolic merit for the users, while to the non-users it becomes a metaphor of debauched evil. Then drugs truly become "herbs of heaven and hell". (46 48)

None of the bans on the currently legal drugs were successful in convincing users to abstain and all were overturned, but not before black markets were created and flourishing. Nowadays these intoxicants are legal and their use is regulated within a lawful context. Nevertheless, their use is not without risk. (5 49) Coffee, as well as alcohol and tobacco, however, have become indigenous to (Dutch) culture and fulfill a multitude of positive social functions. The large majority of users consume coffee and alcohol in a controlled fashion. Perhaps because tobacco was until recently promoted as a safe drug, many users are addicted. Still, the use of this drug does not lead to the profound social misery, which is automatically associated with, for example, heroin. Apparently, users have learned to balance the positive and negative effects of these drugs. Aware of the detrimental nature of excess, use patterns have largely voluntarily been subjected to implicit and explicit social controls --rituals and rules, which display and define appropriate human behavior and are part of normal human socialization processes.

Regulating these drugs within a lawful context acknowledges that they fulfill essential biological and social functions for the human species. Of course, these functions are not restricted to the use of currently legal substances, but merely an expression of an ubiquitous pattern. As the American psychofarmacologist Ronald Siegel expressed it concisely, "[w]e need intoxicants, because the need is as much part of the human condition as sex, hunger, and thirst. The need --the fourth drive-- is natural, yes, even healthy. To say No is to deny all that we are and all that we could be." (7) Therefore, society needs to accept that drug use in itself is not a detrimental behavior or an expression of deviance, but a structural and normal phenomenon with a permanent character. The choice of drugs available, however, has increased significantly over the last 25 years. Through the internationalization of culture -- whether in person (through faster and cheaper travel possibilities) or through the increasingly faster mass communication media-- around the world, people have become aware of prior unknown options. (50) Drugs are not exempted from this ubiquitous trend towards a global culture. Interpreting Entzinger's recent remarks on the phenomenon of immigration, one can argue that "[o]nce [drug use] is accepted as a given, it is of great importance to work towards a positive outcome --for the [consumer], as well as for the receiving society." (50) Drugs are here, and they are here to stay. Society must thus learn to live with their use, minimize the harm of use and turn it to its benefit as much as possible.

The following sections will investigate how the Dutch have tried to apply (certain aspects of) this line of thinking in dealing with the use of illicit drugs. After a brief sketch of its assumptions some results and the current state of affairs will be discussed. Subsequently, recommendations for future policy will be presented.

Dutch Drug Policy in Perspective

"Society will need to learn to cope"

Drug problems first developed in the Netherlands in the second half of the 1960s. Before, use of illegal drugs was not completely unknown, but was limited to specific sub-populations and not considered a real problem. (51) Already in the early 1970s it was recognized that a single repressive approach to drug use would create more problems, than it solves. (52) This recognition resulted in the development of the normalization policy --a drug policy rather distinct from those in most other countries. This policy --a mixture of pragmatism, compromising, down-to-earthiness, strategic planning, but also of trial and error and maybe a little luck-- is, however, an example of the general principles of Dutch social policy making and mirrors policies on related social and moral matters, such as homosexuality or abortion. For that reason some observers have referred to the Netherlands as an "advanced and sophisticated society, a societal testing station, a laboratory for moral and social topics". (53)

The basic assumptions of the normalization policy were formulated in the beginning of the 1980s. The policy is mainly directed at the problematic use of illegal drugs and the management of drug related problems. (54) Acceptance of the permanent character of the presence of drug use implicates that "society will ... need to learn to cope with the dangers they pose". (55) Therefore, the prevention of problematic drug use and drug related harm has been given priority over the prevention of drug use per se. In strong contrast with repression and social ostracism, the key features are "encirclement, adaptation and integration". "Although Dutch drug legislation is still a part of criminal law, it is generally considered as an instrument of social control, the results of which should be assessed with each case, and it should not be considered as a mouthpiece for passing moral judgment." (54) The penal approach is made subordinate to the public health goals. An important goal of the policy is to de- mythologize drug use and the junkie status. To take away the special meaning attached to drug use, users should not be treated as criminals or dependent patients, but as normal citizens who are capable of taking sensible decisions and respond to normal demands and opportunities. (54)

Some Results

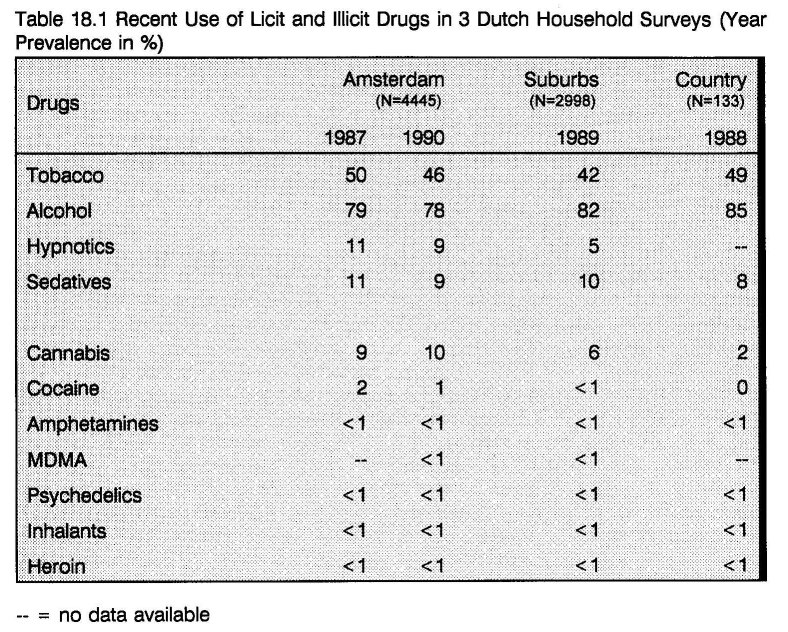

The low level of policing of individual use and consumer transactions of illicit drugs --an important cornerstone of the normalization policy-- has resulted in a rather steady availability of a variety of illegal drugs, in particular in the large cities. Increased availability of drugs is often thought to affect consumption by increasing the prevalence of use. (56) It is therefore interesting to see if Dutch policy has resulted in increased use prevalence. Several recent household surveys documented the use prevalence of both licit and illicit drugs. The following table presents an overview of household surveys conducted in Amsterdam, (16) a suburban area (57) and a rural community. (58)

The table shows that the use of illegal drugs in metropolitan areas is higher than in suburban and rural areas. This has been related to typical urban lifestyles --young one and two person households, who frequently make use of entertainment and cultural facilities, such as (movie- )theaters, discos and clubs. (16) Controlled drug use is often an integrated feature of such outgoing lifestyles. In Amsterdam the same instrument was administered in 1987 and 1990. Of the differences found in Amsterdam between the two years, only the reductions in the use of tobacco and sleeping pills are statistically significant. All other differences are not. Thus, while drugs are comparably easy to procure in Amsterdam, these data indicate a stable use prevalence over time. This suggests that the normalization policy did not result in increased use of drugs. (16)

It is furthermore interesting to explore how users outside the typical heroin using population regulate their drug use. Of particular interest is, how these users handle the comparably powerful psycho-stimulants cocaine and MDMA. In 1990 the Rotterdam Consultation Bureau for Alcohol and Drugs (CAD) registered 1537 client contacts (alcohol: 747; drugs 790). In 66 cases, this concerned people whose primary drug was cocaine and 42 of these were new contacts (heroin users are excluded). In 1989, 53 people (45 new contacts) presented themselves with a cocaine problem. In 45% of these cases cocaine was part of a multiple drug use pattern, mostly combined with alcohol or cannabis. (59) With a recently estimated 12.000 cocaine users in Rotterdam, these numbers are hardly alarming. (60)

Systematic data on MDMA related treatment applications are not available. In Rotterdam and Amsterdam people often request information about MDMA. In Rotterdam, the number of XTC related treatment applications is estimated at one a month or less. (61) XTC related treatment applications in Amsterdam were inventarized by Adelaars. Until autumn 1990 he found none. (31) This does not mean that the use of cocaine and XTC is completely without problems. For example, most subjects in a recent cocaine study by Cohen reported experience with craving and other negative effects of cocaine. (62) A recent XTC study by Korf et al. reported similar findings --many of their subjects have experienced a range of unpleasant effects during or after MDMA use. (32) In both Cohen's cocaine study and the XTC studies by Adelaars and Korf et al. these unpleasant effects were generally related to periods of high use levels. (31 32 62) A consistent finding in all three studies is that when people experience problems with the use of cocaine or XTC, they decrease or (periodically) discontinue their use. As Cohen writes: "Many indications were found that experienced cocaine users controlled their use ..., there are no indications that [this] group lost control and developed into compulsive high level users with a marginalized life style in order to support drug consumption." (62) All three studies described elaborate self-regulation strategies. Thus, while experience with the negative effects of these drugs is not uncommon, only few users apply for treatment and use patterns are subjected to social controls.

The normalization policy has been exceptionally successful in the case of cannabis. In practice both possession and consumer level transactions have been de-facto decriminalized. As was discussed above, the subculture that initially surrounded the use of this drug has completely dissolved, while the table shows that the prevalence of use has stabilized at a moderate level. (63) It can be concluded, that the normalization policy, which characterized the 1980s, has been a major factor in the stabilization and control of the drug problem in the Netherlands. It must be emphasized that in particular the restrained and astute approach of the Dutch police has been of crucial significance.

Some Unresolved Matters

Not surprisingly, the normalization policy has not been a 100% successful. While the Dutch heroin culture is rather stable and easy-going, with comparably little accretion of novice users, (57 58 64 65 66 67) policy has, for example, not prevented the formation of a shunted off residual group of marginalized and demoralized users, whose needs are poorly served. Over time, problematic drug users have changed from rebellious white middle class youth to immigrants, illegals, psychiatric patients and long term prospectless skid row users. The drug treatment and care system has become a repository in which various groups with many different problems are dumped. (68) Whatever the background and make up of their problem, merely based on one aspect --uncontrolled drug use-- individuals are relegated into a system that at best offers treatment or maintenance of the symptom which has been marked the defining feature.

Methadone, which in itself plays a very important and beneficial role in the Dutch approach, is generally dispensed in large scale programs, in which management, automation and registration goals are equal to, if not higher than provision of practical health care and social services. Many heroin users in the field study experienced the treatment in these programs as infantilizing and intrusive of their private lives. Often social control objectives dominate staff- client interactions and clients are treated as patients, whose motives are routinely distrusted. Many individuals have been subjected to this treatment system for ten years or more. One could say that they have become dehumanized commodities of professional treatment networks --the legal branch of the "heroin structure". (69) Beninger referred to this practice as the "trafficking in drug users" (70) --another example of post-modern institutionalization. (71)

In a way, program staff are caught in the same system --tired of playing the intrinsic power games (e.g. around methadone doses), they experience their work as burdening, repetitious, little challenging and unsatisfactory. Their job does not bring them much prestige. A recent survey among the staff of the Amsterdam Jellinek Center showed that 40% is looking for other jobs because of the massive workload (72) and burn-out is a frequent phenomenon. Working in the same position for many years, a considerable number of drug workers are under-educated and have a low market value on the job market. (68) Instead of quitting their jobs, they make their hours, but adjust their efforts downward. Their perception of their client group is often very negative and frustration is projected on clients leading to rigid and sometimes haphazard enforcement of disempowering program rules. This contributes to tension between staff and clients, not infrequently culminating in violent outbursts. This in turn leads to increasing use of sanctions and security measures such as plexiglass between clients and staff, while private security personnel maneuver clients through turnstiles.

An unintended negative side effect of methadone programs --and perhaps of specialized drug treatment in general-- is that they, to a certain extent, endorse the subculture and block societal integration. (73) In contrast with policy formulations, (54) known heroin users are not treated as normal citizens and they may well be the most stigmatized group in society -- denoted as Junks by the public and media, as well as by policy makers and the treatment and care agencies. A Rotterdam drug prevention worker summarized the impact of Dutch drug treatment practice on the heroin using population cynically but concisely as "stabilize, consolidate and segregate". (74) Whereas the Dutch parliament by motion expressed that drug users should be involved in policy making, (75) currently they play no role of significance. Especially in the AIDS-era, these are very worrying developments.

Some New Matters

Currently, HIV prevention for drug users is primarily relegated to the traditional drug treatment and care agencies. Often the social workers of these agencies have problems discussing safer use/sex. Their message rarely transcends the level of do not share needles or use a condom, and is hardly placed in a broader context of general health maintenance. While the Netherlands played a pioneer role in implementing needle exchange, these are mostly integrated in the methadone maintenance programs. Yearly, treatment agencies may contact 60-70% of the population, on a day to day base they only reach less than 40%. Some schemes only serve their own methadone clients. Those most at risk, e.g. out-of-treatment frequent cocaine injectors, are poorly reached by these schemes. The needle exchanges furthermore only offer a limited choice of items --generally only one type of syringe/needle and one or two types of condoms, whereas demand and daily practice are profusely varied. Furthermore, there is little information on HIV seroprevalence outside of Amsterdam and possibilities of early and profilactic treatment are poorly utilized.

Due to a combination of reasons an increasing number of users are pressured into the streets. As a result, nuisance problems (often of a visual nature) have increased, with a simultaneous growth in drug tourism. In other cities similar trends are observed. The completion of the urban renewal process in Rotterdam (resulting in a decreasing number of empty places for the house address scene) is one important reason. The decentralization of the Rotterdam police force is another. Decisions regarding public order and drug related nuisance --e.g. about whether or not raiding a house address-- are now made at precinct level and not weighed against the interest of the local drug policy. When a certain number of complaints are received, the precinct may form a local unit, which prepares and executes a raid. Some precincts are more active, whereas others seem to maintain the usual, more restrained approach. Already at the end of 1989 it became apparent in this study that the house address scene was the object of increasing police pressure and, in two publications, possible public health consequences were discussed (chapters 14, 15). A related and third reason is the increasing emphasis on social safety in the social renewal policy. In a 1991 Rotterdam survey 86% named public order as the biggest problem. In 1988 this was only 47% and in 1990 64%. Degeneration, decay and pollution of the urban environment ranked second, while foreigners rose on the Rotterdam problem inventory from 9% in 1990 to 17% in 1991. Among Turkish and Moroccan residents public order was experienced less of a problem. In 1991 their main worries were more tangible --unemployment and housing. (76) In operation taking back the street the precincts cooperate with autochtonic, in particular elderly, residents. As one neighborhood activist explained the strategy: "Complain as often to the police so that they bust the premises, if only because they're fed up with our calls". (76) Seemingly, the social renewal policy is primarily an outlet of fears and emphasizes repressive approaches. It is questionable whether a policy based on fear will prove successful in the long term.

The traditional drug assistance organizations have not really responded to the changed space allocations of drug users, nor to the increased prevalence of cocaine use, which further augments the problems in this population. Alternative (volunteer) organizations, such as the Paulus Church in Rotterdam, try to fill the gaps, but, having only minimal resources, get overwhelmed. Recently, the increased nuisance incited a blaze in the Dutch discussion on drug policy, which displays a considerable backlash in thinking. Politicians throughout the political spectrum trumpet populistic solutions (such as compulsory treatment and increased police pressure on congregation sites of drug users). Others want to introduce medical heroin dispension to decrease the nuisance. Of course, doctors disagree, while most treatment and care services for drug users remain significantly silent. Seemingly, little has been learned in the twenty years since heroin was introduced in the Netherlands.

Looking at the recent developments around XTC this seems all the more the case. Large XTC seizures followed by a wave of mostly negative and sensational media reports in the first half of 1992 prompted outcries to ban "illegal house parties where increasing numbers of under- sixteens indulge in excessive use of alcohol and ... XTC." (77) Some parties were busted or banned, others were surveyed by undercover police. While some authors predicted a "pollution of the market" when XTC was scheduled in November 1988, (78) this was not immediately noticeable. The recent seizures have, however, resulted in scarcity on the market. Prices went up and especially XTC tablets offered at parties and other irregular channels (as opposed to friendship networks that pool money) vary highly in quality.

This destabilized XTC quality demonstrates again that availability is the feedback model's factor, which is the most vulnerable for repressive drug policy. In addition to the unstable quality, variants of MDMA, such as the more potent MDA and weaker MDEA are being marketed as XTC, as well as other related drugs, such as amphetamine. At the time of its introduction (second trimester of 1992) MDEA was still legal. According to Jamin, Adelaars and Blanken, the introduction of MDEA demonstrates how the drug trade tries to by-pass the opium law. (79) Ketamine has recently also been sold as XTC in the Netherlands. (80) In England the drug seems to have gained some popularity after initial marketing as XTC. (81 82) Ketamine is a pharmaceutical drug used in anesthesiology with powerful hallucinogenic properties. "Compared to MDMA, Vitamin K is Tenth Gear. Where everyone who favoured ecstasy spoke of its mildness, the K people always led off by talking about its power." (83)

The turmoil on the XTC market thus introduced a considerable potential of secondary harm. Furthermore, according to some informants, reduced availability of XTC resulted in anxiety and drug-seeking behavior among users in some parts of the club circuit. De Loor observed that heavy users are becoming isolated from the moderate ones, who blame them for the negative media attention. (80) The feedback model predicts that such a repressive approach would induce the formation of a drug-driven, survival oriented subculture, users' alienation from mainstream cultural information sources, and obstruction of natural processes of self- regulation. These observations may well be the first signs of such a development.

It can thus be concluded, that, once innovative, currently the normalization policy shows several signs of self-contempt and fatigue, especially at the practical level. It is questionable whether in its current form it is suitable to deal with the demands of the 1990s.

Revitalization of Dutch Drug Policy

Transforming the Leading Policy Incentive: Towards a Controlled Availability of Drugs

There is thus a clear need to adjust the policy. When the Netherlands wants to maintain its position on the innovative frontier of the international discussion on drug policy, it must pursue new ways and approaches to counter the above discussed problems. Goldstein and Kalant recently wrote that "the practical aim of drug policy should be to minimize the extent of use, and thus to minimize the harm." (56) Most attempts to reduce the extent of use have relied on prohibition based supply reduction strategies. Not only have these strategies failed to check the use of drugs in countries with a tradition of illicit drug use, but (injecting) drug use is increasingly spreading to new regions. This spread may even be the result of drug prohibition as this has provided the economic incentive for the illicit drug industry, and spreading patterns often follow the routes of illicit drug trafficking. (84) Likewise, prohibition of one drug may induce the emergence of other, more potent drugs and more efficient drug administration rituals. Within months after the establishment of anti opium laws in Hong Kong, Laos and Thailand heroin use appeared suddenly and injecting came up. (85) Equally important is that these conventional strategies have introduced a plethora of secondary harm (see chapter ten). While Goldstein and Kalant seemingly refer to primary harm --harm directly related to the use of a certain substance, e.g. deteriorated tissue integrity of the nasal septum, due to frequent intranasal cocaine use or fetal alcohol syndrome in babies born from alcoholic mothers--, this may well be exceeded by the magnitude of secondary harm (harm related to drug policy), in particular since the advent of the AIDS epidemic. Minimization of harm associated with drug use, therefore, should be the practical aim of drug policy. Reduction of the extent of use may well be part of the strategy, but prohibition has proven to be unsuitable for this purpose, as it has resulted in the almost total absence of government control over the chain between producer and consumer. By criminalizing the drug trade, control has been handed over to illegal enterprise, resulting in an uncontrolled availability of drugs.

Recently one of the architects of the normalization policy, Eddy Engelsman, contemplated on a drug policy outside of criminal law. (86) Abandoning criminal law as the (dominant) policy instrument does, of course, not imply abandoning all control. Drugs are and have always been key commodities. Just as any other key commodity (food, housing, legal drugs), these need to be regulated. But by abandoning criminal law the chain between producer and consumer can be regulated more efficiently by simpler enforceable regulation systems. While this would be a preferable situation, it would be contra-indicated to change the law abruptly and legalize all drugs from one day to the other. This would disturb the natural progression of the described cultural transition process. Both users and mainstream culture need the time to adapt to increased availability of drugs.

Instead, the Dutch normalization policy should be revitalized --from containment of problematic drug use and management of drug related problems, the leading policy incentive should be shifted towards actively influencing the nature of drug use and directing drug using cultures towards less harmful patterns of use. The above explained cultural transition process of the heroin culture should be more actively influenced --its orientation at survival lessened while encouraging a transition towards progress. Likewise, the social controls that communicate safe use patterns in the XTC culture must be stimulated. The results of the present study suggest that such interventions are certainly feasible, especially in the Netherlands. But this will require sophisticated strategies and innovative interventions focussed on the drug culture(s) and its determinants. A step-by-step decriminalization of the various drugs --leading to, what one might term, a controlled availability-- should be part of the policy instruments, but is not the only one available. In the broader perspective of current Dutch social policy thinking, such a development would, in fact, offer a meaningful example of social renewal. Evidently, these activities should be monitored closely by research.

Increased Drug Availability and Prevalence of Use

It is often argued that increased drug availability will result in increased use. (56) Drugs themselves are considered to have such powerful reinforcing properties that mere availability will lead to (uncontrolled) use. Animal experiments are often presented to support this thesis. (87) However, Rhesus monkeys given four hours of daily access to cocaine during which drug delivery resulted from each lever press regulated their intake to a remarkable degree and showed stability in their daily cocaine use over periods of months. (88) In contrast, increasingly restrictive experimental regimes result in higher responding rates (and thus use levels). For example, monkeys in a progressive ratio schedule (89) would vigorously press the lever up to 12.800 times in order to get a shot of cocaine, depending on the dose. (90) In as much the drug taking behavior of these caged animals can be compared with that of humans in their natural setting, these experimental regimes more likely measure factors which resemble different aspects of prohibition in a highly stressful social setting, than a single pharmacological drug effect. Furthermore, in laboratory experiments with two rat colonies --one in a conventional experimental environment, the other in a simulated natural environment, a rat park-- affinity for opiate drugs could be established only under restricted conditions. (91)

Another argument often put forward is that of the per capita higher prevalence of use and addiction among physicians and other medical professionals, who have easy access to drugs. (56) These professions, however, are often very stressful with long working hours. More importantly, drug taking medical professionals risk heavy sanctioning, such as loss of professional license and criminal prosecution. Because of this threat and the social stigma involved with the use of illegal drugs, these drug using professionals are almost without exception solitary covert users. They are highly secretive about their use and do not associate (knowingly) with other drug using professionals. (92) This seriously hampers the formation of controlling rituals and rules as there is no exchange of information between, nor support or pressure from, (drug using) peers.

The rising prevalence of illicit drug use in production regions or the prevalence of opiate use in nineteenth century Europe and North America is likewise presented to support the thesis that increased availability will result in increased prevalence of drug use. However, table 18.1 indicated that in the Netherlands the use of drugs has stabilized, despite their relatively high availability. In addition to what was said above about the role of prohibition in the current spread of drug use, it can be argued that today's socio-economic conditions do not compare to those of the previous century, in which many drugs furthermore were rather indiscriminately promoted. Nowadays knowledge of and experience with drug use has increased greatly --not only of the pharmacology of the substances, but, more importantly, also of the social (learning) processes involved in drug taking. Likewise, prevention and education has become a science. Anti-tobacco and alcohol moderation campaigns indicate that lower use levels and self-regulation can well be established within a lawful context.

A Demand for Positive Rules

Negative rules deny the pertinence of behavior (thou shall not!) without offering acceptable alternative models of conduct. Almost all current drug laws are negative rules which do not make sense to those who use drugs and thus brake them by definition. Therefore negative rules are difficult to enforce. In every situation where people are subjected to rules, which they do not agree with or see the rationale of, they will look for and create channels to evade these rules and protect their interests. Thus, in every closed institution (prison, boot camp, psychiatric clinic) one will find an informal/underground communication and exchange system that distributes restricted information and commodities (e.g. food, electronics, (bootlegged) alcohol and other drugs). (93) Likewise, many people disagree with speed restrictions on multiple lane highways --not only do they break them, but they also try to circumvent enforcement with radar warning devices. Positive rules, at the other hand, make sense even to those who break them and thus are easier to enforce. Traffic lights and way of passage rules, for example, are ubiquitously accepted. (94) But, illustrations of positive rules can be found in all social groups. Figure 18.5 depicts an example of a positive rule regulating tobacco smoking on a birthday. The text translates into: "We would prefer that you did not smoke in this living room until our daughter Tessa Fairy is in dreamland and we give you the sign."

The implementation process of a controlled availability of drugs must be accompanied by education and prevention activities aimed at strengthening the social determinants of self- regulation. While a certain extent of ritualization around drug use is a positive requirement of self-regulation processes --in particular some re-ritualization around alcohol use may be beneficial to users and society as a whole-- the use of illicit drugs should be de-ritualized. The symbolic power of sharing a dose of heroin should be weakened as well as the current status of heroin use as a key indicator of subcultural identity. The strong reliance on, often (group) idiosyncratic, rituals should be superseded by more general applicable rules. These should take the form of positive rules that sanction socially acceptable patterns of use.

Social Policy and Life Structure

In general, the life structure of drug users is not a specific target of drug policy, but rather the subject of general socio-economic policy. Unfinished education, unemployment, lack of perspective and other (psycho-social) life stressors have all been associated with problematic drug use. (95 96 97 98) In that respect, socio-economic destitute is perhaps the main determinant of increasing prevalence of (uncontrolled) drug use in and around the poverty stricken production regions. This emphasizes the multi-dimensionality of the proposed model. It may be a rather moth-eaten phrase, but drug policy must be embedded in a broader framework of socio-economic policy that aims to provide citizens with the skills and chances to pursue a satisfactory life. The potential role of drug treatment in this area will be addressed further below.

Availability of Cannabis and XTC

Actually, the time for adjustment of the cannabis policy is riper than ever. While there are no availability problems at the consumer level, in the current twilight zone situation the cannabis trade seems to be increasingly controlled by non-legal enterprise. The number of coffee shops is growing and some are apparently less willing to comply with the --typical Dutch-- implicit rules, for example regarding nuisance, advertisement and availability of other (il)licit drugs. Completely unrestricted opening hours, furthermore, result in a --quite undesirable-- unregulated availability. Further decriminalization, --which may imply legalization-- would allow for a controlled availability through effective regulation of (domestic) cultivation, geographical spread of sales outlets, opening hours, product range, advertisement, quality testing, etc. (99) New drugs, such as XTC could be subjected to an experimental period, in which their controlled availability through regulated channels should be guaranteed. Such a strategy would probably not only eliminate the fast developing black market, but prevent considerable potential harm when supported by well considered and targeted information campaigns. Political ignorance and fear of foreign critique, however, result in indecisiveness and procrastination. Even worse, proposals for a more repressive approach of cannabis have recently surfaced. Likewise, while the Rotterdam drug squad is unhappy with the illicit status of XTC and complains about the recent pollution of the XTC market, (100) this development is very likely the result of the targeted actions of inter-regional organized crime squads (IRTs), picking an easy mark. (101) The prolonged criminalization of these drugs can be considered a serious crime against public health.

Strengthening Rituals and Rules of Users of Cannabis and XTC

In the domain of life structure users of cannabis and/or XTC probably need not be targeted as a distinct population, as their lives are fairly integrated in non drug dominated networks. In contrast, the formation of rituals and rules directed at moderation and safe controlled use of these drugs will require extra attention, especially in the case of XTC. In addition to mainstream media --school, public service announcements similar to the national alcohol moderation campaign-- subcultural channels may also be utilized, for example to distribute information on how to handle in case of adverse effects of drug use. A good example of this approach is a recent flyer from MDTIC in Liverpool on how to prevent, and handle in case of, heatstroke. This glossy party flyer-like folder uses lay-out, style symbols and argot of the English rave culture to present a life-saving message and is distributed via subcultural networks, such as certain records and clothing stores. (44) Not only can these media be used to strengthen and transfer existing, but also to feed new cultural norms. Gay Men's Health Crisis' billboard advertisement campaign in the U.S. stating that "9 out of every 10 gay men use condoms" in a time that perhaps one out of 10 actually did so, provides a good example. The key issue is to go beyond simplistic don't do this, don't do that messages and provide positive identification models, non-judgmental advice, and practical examples of safe conduct. When such valuable information is introduced into the community it will be disseminated by users themselves utilizing natural network links and peer pressure. (102)

Availability of Heroin

The real challenge, however, is to be found in the heroin culture. Self-regulation processes in this community are seriously hampered by two decades of repression. Policy must be directed in ways which empower users, stimulate self-regulation, and make it possible for them to take responsibility for their lives in general and drug use in particular. Medical dispension of heroin or injectable drugs is perhaps beneficial for a subgroup of users, for example those with serious stages of HIV disease, but will not have a significant impact on the heroin culture as a whole. It does not take away craving for cocaine, nor does it stimulate self-control, as control over the use level remains in the hands of an outside force --the doctor who writes the script. Therefore, enlarging drug availability must be organized outside the realm of drug treatment or care. As explained before, instant legalization is likewise not advised. Instead, heroin and cocaine should gradually become easier available, and, applying the expediency principle, consumer transactions should no longer be prosecuted.

A lot can be learned from the decriminalization of cannabis and the current policy towards house addresses in Rotterdam. Future policy must be a logical elaboration of, and thus be grounded in, the current street practice of tolerated house addresses where drugs are sold and used. This implicates an important role for the police. The police must extend its tolerant approach to a more active, regulating one. Use and vending of drugs at house addresses or in certain cafes should no longer be a reason for intervention, unless it involves inadmissible nuisance or other unlawful activities (e.g. fencing). An alternative or complementary possibility is the creation or endorsement of low key members only club houses, which can best be envisaged as a hybrid of the coffee shop and the opium den, (103) where drugs can be purchased for reasonable prices and used in a relaxed atmosphere. In addition to tolerating these venues, the police should actively explain this policy to the people that run them. When use and consumer sales are no longer reasons for intervention, and when given the proper support, users will be more than willing to cooperate with the authorities to control nuisance.

An interesting example of this proposed policy --apparently practice precedes policy again-- is provided by the recent off-the-record cooperation of a police precinct, a neighborhood social safety project (a positive exception) and a house address in the west of Rotterdam. In contrast with the rather repressive social control approach sketched above, drug use itself is accepted to a certain degree in this neighborhood and provisions are taken to reduce the harm for both the neighborhood and the users. For example, a steel sharpsafe has been installed in a park where injecting happens regularly and a space has been provided to a group of users. This tolerated house address offers both smokers and injectors a place to use. While clean needles are supplied, the provisions for smokers are, however, more favorable. The place has distributed a newsletter among its visitors issuing the house rules, information about health issues and other significant topics. HIV prevention materials are supplied by a local outreach team while health workers have access to the place. Its visitors have been active in removing abandoned needles off the streets and parks in the neighborhood and the side walk in front of the place is frequently swept. Police officers visit the place several times a week to discuss the state of affairs and to provide practical advise to visitors. This regulatory approach is being extended to several dealing addresses while simultaneously, a number of really vexatious addresses have been closed down, leading to a decrease of nuisance in the neighborhood.

In general, these places should discourage injecting by offering limited provisions for injecting (however, without stimulating unintended unsafe situations) and make more moderate modes of administration, such as smoking more attractive. Perhaps a few separate venues for injecting should be created. Quality control would become feasible and new, milder, smokable products (e.g. heroin reefers) can be introduced at lower prices than injectables. Coca tea or "Cokee" may be served free as there are some indications that this may reduce cocaine craving. (7 104)

Changing the Rituals and Rules of the Heroin Culture

The proposed controlled availability policy will induce a gradual adaptation of rituals and rules. However, when left to its own virtue it will take some time before these cultural changes become apparent. One should not forget that most of the current rituals and rules have been developed over a period of two decades and during that period they have proved highly functional. Merely feeding the culture with information is insufficient for establishing rapid change. But, in light of the HIV epidemic among IDUs rapid speed is of the essence. Such fast interventions cannot be expected from the established treatment agencies. A view which is apparently shared by the authorities as a recent government report doubts the effectivity of the current efforts. (105) The report considers merely providing leaflets and syringes insufficient. It states that prevention policy needs to be stronger and more innovative in relation to methods of approach. The report recommends to involve (ex) users in approaching out-of-treatment populations and employing drug users as para-professionals. Institutions are suggested to encourage self-organization of drug users and offer them facilities to do so. (105) There is thus a recognized need for immediate action directed at changing the rituals and rules of the heroin culture regarding HIV related behaviors.

Only few peer support initiatives have been undertaken in the Netherlands. One Rotterdam outreach program cooperated with active IDUs to distribute clean works via established network relations (described in chapter fourteen). In the Deventer No-Risk project active and former drug users were recruited to educate out-of-treatment users. They supplied prevention materials (needles, condoms, etc.) and provided HIV prevention trainings to other users urging them to subsequently pass on the information in their networks. (106) Another pilot project in Nijmegen worked with two former sex workers to provide peer education. (107) While all of these projects suggest that involving drug users in prevention activities is feasible and promising, they also revealed some obstacles in the realm of continuity, status problems, cooperation with other professional organizations, credibility, training and support, etc. (107 108) Very similar problems are described by Broadhead and colleagues, who studied the San Francisco NIDA outreach demonstration project. (102 109) They referred to these problems as agency problems, which can occur in any bureaucratic organization. A major problem of the Dutch peer support projects has been the lack of sufficient funding, in particularly for proper scientific evaluation. As a result, it is not possible to adequately assess their contribution. Likewise, these projects have a rather weak theoretical basis. Nevertheless, peer support/pressure seems an important method for HIV prevention. The current challenge is to operationalize the concept in ways that preclude or overcome the indicated problems.

Recent sociological research offers interesting perspectives on the formation and enforcement of norms, valuable for the concept of peer based HIV prevention. (110 111) In general, emergence of norms is dependent on three factors: 1) inclinations or actors' preferences regarding their own behavior; 2) regulatory interests or actors' preferences regarding the behavior of others; and 3) enforcement resources or measures for enforcing norms, for example access to sanctions and information. Most studies of norm emergence have focussed on inclinations or enforcement resources, but these recent studies emphasize the role of regulatory interests. (111) Regulatory interests create the demand for norms, while contradictory inclinations determine the supply cost of normative compliance, giving the emergence of norms a market-like quality. Social norms can only emerge when the regulatory interests that order cooperation outweigh the contradictory inclinations that lean toward defection. (102)

As knowledge of the AIDS epidemic diffused into the IDU community, new regulatory interests to reduce high risk behaviors emerged. But, while IDUs share these regulatory interests in preventing HIV infections, there are numerous contradictory inclinations resulting from the recurrent risks inherent to survival in the heroin culture (police harassment or arrest, overdose, rip offs and violence). The reduction of these conventional risks often relied on strategies that entail risks for HIV infection (not carrying works, use of shooting galleries, using with a partner and needle sharing). (112) Nonetheless, as chapter twelve explained, new safe use norms have emerged. The aim of future interventions must thus be to strengthen already existing risk-reduction norms and where necessary stimulate their adoption.