THE SHARING OF NEEDLES AND OTHER INJECTION PARAPHERNALIA: AN ETHNOGRAPHIC ANALYSIS

| Books - Drug Use as a Social Ritual |

Drug Abuse

THE SHARING OF NEEDLES AND OTHER INJECTION PARAPHERNALIA: AN ETHNOGRAPHIC ANALYSIS

Most of the current behavioral acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) research consists of studies relating HIV prevalence to the prevalence of HIV-risk factors, such as needle sharing. Few published studies describe what actually happens in such needle sharing events. Given this gap in the literature, there is an obvious need for ethnographic studies that provide thick description of the patterns and circumstances of drug use and locate hitherto unmeasured variables associated with risk behaviors such as needle sharing. In the previous chapter it became clear that the notion of needle sharing only partly describes and therefore obscures the intricate interactions of which this specific, but dangerous, act is an element. Sharing behaviors have been found to be frequent and significant events for the drug users observed in this study. The sharing of valued items such as housing, food and clothing is an everyday occurrence tied to the needs of survival in extreme circumstances. The sharing of drugs, observed among both injecting drug users (IDUs) and non-IDUs, fits into this wider pattern of daily interaction and exchange. In this chapter a further analysis of unsafe injecting drug use situations is presented. The chapter will discuss the factors involved in the cases of needle sharing observed in this research. It will also address the sharing of other drug injection paraphernalia --a frequently observed activity.

Factors Underlying Needle Sharing

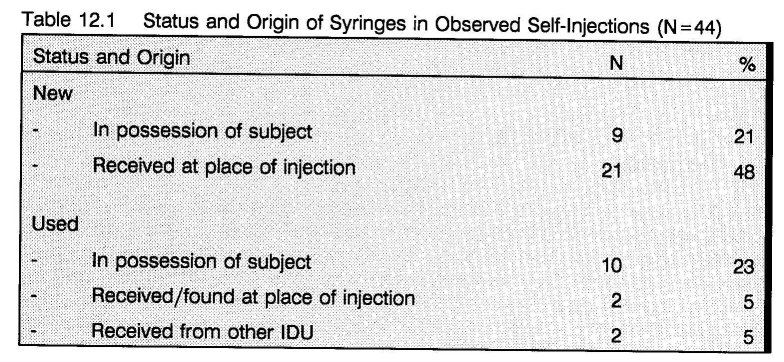

In 68 percent of the observed self-injection events, a new syringe was used. In 23 percent IDUs reused their own syringe. In less than 10 percent of the self-injections, a potentially unsafe syringe was reused (table 12.1). The used syringes found, or received from others, were not adequately cleaned (e.g. water only). (1 2) The unsafe self-injections were recorded at addresses where injecting was permitted and in a public place. Because of the normal address rules against injecting, IDUs used their drugs in private settings more often than smokers. These house rules may prevent needle sharing. However, some IDUs let their friends and acquaintances inject at their place, sometimes in return for a taste of the drug. At some of these using places and at some of the house addresses that allow people to inject, clean syringes supplied by an outreach and needle exchange program were dispensed (see chapter 14). 70% of the new syringes used were of such origin. Thus, instead of sharing used syringes, IDUs shared new syringes, thereby giving the responsibility for safe injecting a collective quality, building on structural, normatively regulated interaction patterns --a very important implication for HIV prevention.

Although both collective and individual norms of responsibility have been found to operate to minimize and manage the risks of needle sharing, there were a few situations in which unsafe needle behaviors were observed. The following fieldnote, for example, was recorded on the first floor of a squatted house. The house had three floors of which the first and third were in use. It did not have running water; water was carried to the house in containers from a garage next door. The house was inhabited by a group of older IDUs. At times the group offered shelter to other drug users. They also enabled other drug users to deal heroin, cocaine, or amphetamine in exchange for money and/or drugs. Occasionally they themselves dealt drugs as was the case at the time of observation. This house also was supplied with sterile syringes by the outreach program, mentioned above. However, at the time of observation it was unclear whether there were any new syringes left. Jack (the doorman) just opened the door for Billy and Dirk. They all knew one another. During the observation some other users went in and out.

Billy asks Dirk what he wants. "Let's do coke first and then a cocktail", Dirk replies. Billy has a syringe wrapped in aluminum foil. He does not want to wait for a new syringe. Dirk does not have one with him and starts searching. He asks Jack if there are any new ones left. "I don't know", Jack replies, "Maybe upstairs. Ask Karel, he's there." They call Karel several times but he does not answer. Then Dirk finds a syringe on a cupboard. It is unclear who it belongs to. He rinses it with water. He pulls up water twice from a cup he has filled from the water container and squeezes it through the needle. Billy mumbles something about AIDS. Dirk says "Ik heb schijt aan AIDS." (I don't give a shit about AIDS).

Dirk used this syringe two times. First he shared a dose of cocaine with Billy and within 30 minutes he shared a cocktail with Billy and Jack. both times these drugs were shared by frontloading.

In the second fieldnote, two IDUs (Eric and Anja) were in the shooting room of a house address where injecting is allowed. Leo entered the room. Leo did not come to the address to buy drugs, but to look for Eric. Eric owed him money and he had heard that Eric was at the address.

"I wanted to ask you if you can pay back or otherwise if you could help me with a shot." Leo said. Eric was not able to pay Leo back but offered a cocktail. Leo gladly accepted. "Great man, you don't know how wonderful that is, I'm so glad I didn't miss you here." However Leo was not in possession of a syringe. Leo asks Eric for a syringe: "I couldn't get a new one. The needle exchange at the Central Station had closed already". Eric tells Leo he only has his own, which he is not willing to share. Then Leo asks Anja if he can take one of her used syringes that are laying in front of her. Anja: "That's useless, they're all blunt, but if you want to try that's okay with me." She picks up several syringes from the floor and looks closely at the needle, comparing one with the other. Finally she makes her decision which one to give to Leo and gives it saying: "You have to clean it well." Leo goes with the syringe towards the sink and cleans it seven or eight times with cold water. To clean the plastic part of the needle, he moves it in such a way that there is some space between syringe and needle. He presses the plunger strongly so the plastic is cleaned under pressure. The water now does not come through the needle but shoots away through the little space between syringe and the plastic needle holder. Leo states: "It must be clean now". Anja tells him: "Don't worry I'm checked for AIDS recently, I told Eric too".

In the following fieldnote, Mohammed and Abdul had obtained new syringes from the exchange program near the Central Railroad Station before they went to a house address to buy cocaine and heroin. Not allowed to inject at the address, they went to a small greenhouse in a park. Mohammed prepared the jointly bought drugs. He then divided them by frontloading. Abdul wanted to check if the solution was equally divided between both syringes.

Mohammed gives both syringes to Abdul and asks him: "Don't you trust me?" Abdul doesn't answer. He holds the syringes next to each other and stares at them. While doing this he accidentally drops a syringe. The needle falls straight onto the ground. Abdul curses and so does Mohammed. Mohammed says: "Now you see what happens, why don't you believe me?". Abdul picks up the syringe and looks closely at the needle. He asks Mohammed if he still can use it. Mohammed takes the syringe and runs the needle tip over his thumbnail. "No", he says, "there is a burr on it. It's not sharp any more and it's dirty. You've got to get a new one". Abdul: "No, I don't go back, give me yours". Mohammed: "Then you have to wait until I'm ready". After Mohammed has taken his shot he starts cleaning his syringe with the water from the bottle. He puts some lemon juice in the cooker again, pulls it into his syringe and shakes it so that it mixes with the water. He puts the needle back on it, holds it with two fingers, and presses the water/lemon solution through it as hard as possible. Mohammed explains: "the lemon bites and cleans the needle better". When he's ready, he puts the needle on Abdul's syringe.

The examination of these three fieldnotes indicates that needle sharing often is the result of complex and multiple factors. It is important to ascertain that in all of the fieldnotes, needle sharing took place as an element of a drug sharing sequence. In none of the fieldnotes, the use of another's syringe was, however, planned. Rather an unexpected situation occurred. In the first fieldnote, Billy and Dirk select the particular address because injection is allowed and new syringes are available. However, at the time of entering new syringes were not available. In the second fieldnote, Leo did not have the money to buy drugs but, by coincidence, learned that Eric, who owed him money, was at the address. He did not have a syringe as he had been too late at the needle exchange. In the last fieldnote, although sufficient prevention measures were taken in advance, an unfortunate accident puts one of the users at risk.

In all three situations an unanticipated change puts the IDUs in the uncomfortable position of choosing between postponing/abstaining from a shot and an unsafe injection. They all chose for the unsafe injection although they were well aware of the potential risks of their behavior as evidenced by their rather intensive efforts to clean the used syringes. In the first two fieldnotes, AIDS is associatively mentioned while cleaning the syringes while in the last fieldnote the use of lemon is presented as a cleaning method superior to using water only. However, the existence of AIDS-related knowledge as an effective protecting factor can be seen as dependent on certain specific situational factors.

The significance of one of these situational factors, the intensity of drug craving, deserves special attention. Shortly before an injection, IDUs can often be observed to become highly aroused. This arousal leads to preoccupation with the sequence that relieves withdrawal or craving. (3) For some IDUs, this sequence begins when the drugs are obtained. For others, the preparation of the injection is the starting point. As one IDU put it: "As soon as I put it on the spoon my stomach turns around and I know it's gonna happen, I'm gonna feel that intense rush". In all of the presented cases, postponing the injection would have caused noticeable stress. In the first fieldnote, Billy and Dirk were in high anticipation of an injection. They had already visited the address 30 minutes earlier, expecting to find a dealer working. However, the dealer had just left, so they went to another to buy. When they returned Billy complained that it had taken them considerable trouble to find a dealer. Dirk did not bother to see if there were any new syringes upstairs. By this time, the drug craving had become too intense for further deferral. Leo (second fieldnote) explicitly expressed relief when he was offered an injection. In the last fieldnote, the accident happened only seconds before actual injecting. Obviously, the craving of Abdul has become so intense that he ignores Mohammed's advice to obtain another syringe. Furthermore, in all cases cocaine or a mixture of cocaine and heroin was injected. The addition of cocaine to the daily drug-using rituals has been observed in the field to be associated with an intensification of craving and a disruption of stabilized heroin- methadone patterns.

While situational factors play the most important role in needle sharing, certain personal factors can also be seen. One such factor is that of socially learned experience with the injecting ritual, internalized during the IDU career. This experience includes, among other things, protective skills that support safe needle use. The interaction between Billy and Dirk provides an illustration of this factor. To inject, Billy, an experienced IDU, went to a place where normally clean syringes are available. Nevertheless, he carried his own used syringe anticipating the absence of new ones. In contrast, Dirk, a novice IDU with no visible needle marks, did not bring a syringe. Immediately after injecting cocaine, he began smoking heroin. He identified himself, not as injector, but as a smoker, stating: "I'm only shooting now and then, strictly speaking I am a chineser" (chaser). Irrespective of his AIDS knowledge, Dirk's particular self-deception works against taking the appropriate precautions. His self-perception as a chaser provides a false sense of security that, in turn, leads to blase attitudes such as "I don't give a shit about AIDS". In the last fieldnote, another case of inadequate socialization is found. Both users were still at an early point in their injecting careers. Mohammed, who reported he had been injecting for about half a year, is instructing the even less experienced Abdul who was about to take his 10th lifetime injection.

The Sharing of other Drug Injecting Paraphernalia

Even in injecting drug use situations where needle sharing does not occur, there may be hidden risks that are the result of related practices. Drug users often share other paraphernalia, such as knives, lighters, spoons, water cups, ties and filters and chemicals, such as stomach salt (baking soda or bicarbonate) or ammonia (both used in preparing crack-cocaine) and acidifiers, such as lemon juice or ascorbic (to dissolve the heroin). These tools and materials are all used in the process of preparing the drug for consumption and some of these are supplied at house addresses.

In general, there is no exchange of body fluids involved in the sharing of chasing paraphernalia, but sharing chasing tubes may transmit minimal quantities of saliva resulting in the spread of, for example, bacteria and viruses that cause mouth sores, colds, influenza and maybe even hepatitis. Thus these practices normally include no risks of HIV transmission. IDUs' sharing of knives, lighters and tourniquets is also without risks. The sharing of citric and other acids probably presents no risks, because of the aggressive properties of these agents. Infection may result from sharing water containers, spoons and filters.

Water is an important ingredient for IDUs --it is necessary to dissolve the powder drugs. When available IDUs will generally take water from a tap. However, when the injection is taken at a place without running water (e.g. a squat) often the water is stored in cups, bottles or a jerrican:

Frits went to a jerrican with water and with the syringe (without the needle) he pulled out some water. He then poured a bit on the spoon.

Cleaning a syringe with water from a container for common use may contaminate this container. Virological studies have demonstrated that HIV can survive in tap water for an extended interval. (1) In tap water at room temperature, the virus can survive for over one week. (4) Consequently, using water from a jointly used container to prepare an injection may be a means of viral transfer. It can contaminate every item that is part of the user's injecting set, even when these are new or cleaned beforehand. (5)

Two factors are of importance in regards to the transmission of HIV via water. First, there is the drug injected. Injecting cocaine or amphetamine alone may carry more risk than an injection of heroin or a cocktail of heroin and cocaine or amphetamine, as these drugs are generally dissolved without heating (cold shake). When heroin is involved the solution must be heated which may kill the virus. This is, however, dependent on both the temperature and the time of heating. (6) Moreover, due to the chemical form (a base) of the heroin, marketed in the Netherlands, users use an acidifier to dissolve the heroin in water. This acid may also impact on the potency of the virus. A recent Scottish study found that the usual vinegar solutions used by Glaswegian IDUs to prepare heroin for injection inactivated both cell-free and cell- associated HIV. (7)

The second important point is the quantity of HIV positive blood in the water container. The probability of infection presumably depends on the quantity of virus exchanged. Recent simulations of needle sharing have found the volume of transferred blood from index user to first sharer to range from 0.51 ml to 28.36 ml, depending on syringe size, booting and rinsing. (8) In another study the mean volume recovered in needle sharing simulations was 34 ml. (9) These volumes are, however, more dependent on the type of syringe than on the barrel size, whereby 1 ml insulin syringes with fixed needles hold considerably less residue than syringes with detachable needles. (10) Information specifying the concentration of HIV in blood and the likelihood of infection in vivo is unavailable, (8) but a relationship between the amount of virus and the chance of infection has been suggested. (11) As the concentration of blood and consequently the volume of HIV in water containers is in general significantly lower than in used syringes, the chance from infection by sharing water is probably lower than when sharing or frontloading with unclean syringes, although the minimum quantity of HIV capable of infection is unknown. Therefore, the availability of water, the size of the container, the frequency of use and the number of users may be all of influence. In abandoned buildings without running water, Koester et al. observed containers with water that had turned pink from blood. (5) In this research, such extreme situations were not observed.

Spoons are often readily available on dealing / use addresses and used by both smokers (to prepare base-cocaine) and IDUs. Spoon sharing is probably the most common form of paraphernalia sharing. But in none of the observations of the sharing of spoons (or other drug paraphernalia) could a ritual interaction pattern be detected. Spoons are shared in the same manner as coffee users may lend or borrow a spoon. To illustrate a more or less typical situation of spoon sharing the following excerpt from a fieldnote is presented:

John starts to prepare a shot of heroin. He takes a spoon from a cup which contains several and throws the content of the paper in the spoon. [...] In the meantime Cor has entered the place. He has a quarter of cocaine and uses the same spoon as John did to prepare an injection.

Most IDUs use filters when drawing the solution into the syringe prior to injecting. The main purpose of this step is to screen out undissolved particles that may clog the needle. (5) This is a universal practice, as even when the powder is totally dissolved, one uses a filter. Wadding and cigarette filters are most commonly used. A piece of tissue can also be used. When these are not available the user will often take some lint from her/is clothing. It is not unusual to leave the filter in the spoon for the next injection:

Jack puts the coke in a tea spoon which he takes out of the open low cupboard he is preparing his shot on. In the spoon already is wadding filter. He gets a cup of water from the tap, pulls up some water with his syringe and squirts some in the spoon.

One reason for saving the filter in the spoon is that a residue of the drug remains on the spoon and in the filter:

Bert has just used Patrick's spoon to prepare a shot. Patrick then wanted his spoon back. "Here it is", Bert said, "look there is still some dope on it", as if it was a gift.

Some IDUs save the filters and inject the extract in bad times when they run out of drugs and money. Injecting the extract may lead to a, by many users feared, syndrome, characterized by symptoms, such as sudden chills and trembling over the entire body, muscle aches, headache, nausea and fever, believed to result from an acute reaction to a bacterial infection. (12) Because of the manifest trembling, this syndrome is known under the local argot term the shakes. When a fellow user in need of a dose is granted such savings, this syndrome seems probably the smallest risk. The practice of reusing and sharing filters is yet another opportunity for HIV transmission, as blood rests may easily remain in the fabric of the filter. Even when the liquid vaporizes and the presumed blood and virus in the filter (or in the spoon or other injecting paraphernalia) dry, these remain infective. (2)

A possible facilitating factor of paraphernalia sharing and contamination with HIV or other blood-borne infections is related to the physical condition of the veins of IDUs. A considerable number of IDUs suffer from collapsed veins resulting in great difficulties with injecting, as is witnessed in the next fieldnote:

When shooting up Harrie uses a hemp rope to tie his arm. He is having problems finding a vein. He tries several spots on his left arm but he does not succeed. Then he tries his other arm, also without success. He is already bleeding from several spots. He sits on the floor rolls up his pants and tries his left leg and the other. Finally he succeeds. He washes the blood from his arms and legs with a rag and some water. With the same rag he sweeps the blood he dripped on the floor away.

In such situations hygiene is clearly subordinate to the difficult task of injecting, resulting from, paradoxically, the same lack of hygiene and high injection frequencies in combination with poor self-injection skills. Sometimes it can take so much time to get a hit that the solution clogs in the needle or the syringe is completely filled with the blood-drug mixture. As a result, the plunger cannot be pulled back anymore and the solution is squirted back on the spoon with the possibility of contamination. Female users, in particular when frequently using cocaine, may be more susceptible to these problems, as women, in general, have smaller and harder to hit veins. (13) Such was the case in the following fieldnote. In this fieldnote, Anja, a 24 year old white Dutch female, is sitting in the attic of a dealing place for about two hours, trying to get a hit. (This observation was recorded in the same room prior to the observation of the needle sharing interaction between Anja and Leo in section 12.2.) She is surrounded by pieces of toilet paper, some with blood spots, old syringes containing blood rests, her spoon and a plastic lemon. Her left underarm and hand are streaked with dried blood. She is bleeding out of several injection sites. Then Eric came in:

"Look how I'm looking"; she says; I can't hit a vein, I'm trying for more than an hour." She removes the long, thin piece of textile she is using to bind off, from her arm and turns it around her wrist. She wants to try her hand again. She sticks in the needle several times, turning it around under her skin in search of a vein. The syringe is filled with blood. She groans when she moves the needle around under her skin. Eric tells her to watch out for the blood to congeal. "Otherwise it will choke up your needle", he says. Anja replies, "I know, I have put it back on the spoon two times already, heated it and pull it back in again through the filter." She is pointing towards the spoon with the bloody filter still in it, while the syringe stays in her other hand. Eric asks her now if he can use her spoon to prepare his shot. Anja says, "Okay, but you have to clean it proper". Eric takes the spoon from the ground, walks with it to a garbage can aside of the table and with a piece of paper he took from the table he wipes the bloody filter out of the spoon. Then he walks towards the sink and cleans the spoon thoroughly with cold water and a piece of toilet paper. When he's finished he carefully examines the spoon to see if he has cleaned it well.

Ensuing Eric uses Anja's spoon to prepare his shot. Then Anja uses the spoon to reboil her dose of gravy (the mixture of the drug solution and blood) for the third time. A little later Leo comes in. He gets some drugs from Eric --who owes him money-- and also uses Anja's spoon, after cleaning it with water and toilet paper.

Difficulties with injecting due to collapsed veins can increase the risk of HIV-infection in several ways. Someone will be more eager to borrow a needle when, as a result of persistent failure to enter a vein, the needle has become dull or clogged (Anja asked Eric, but he refused), but the syringe may also get filled with blood to the point the plunger cannot be pulled back further and the gravy has to be put back in the spoon, thereby fouling the spoon. As the preceding observation of Harrie shows, the multiple skin and vein punctures can result in blood contact with materials, that may be reused by others.

Potential Routes of HIV-Transmission in Group Drug Injection Interactions

The preceding two sections discussed the contexts of drug injection interactions that may put the actors at risk for HIV-infection. The following figures summarize these interactions and present the potential routes of viral transmission.

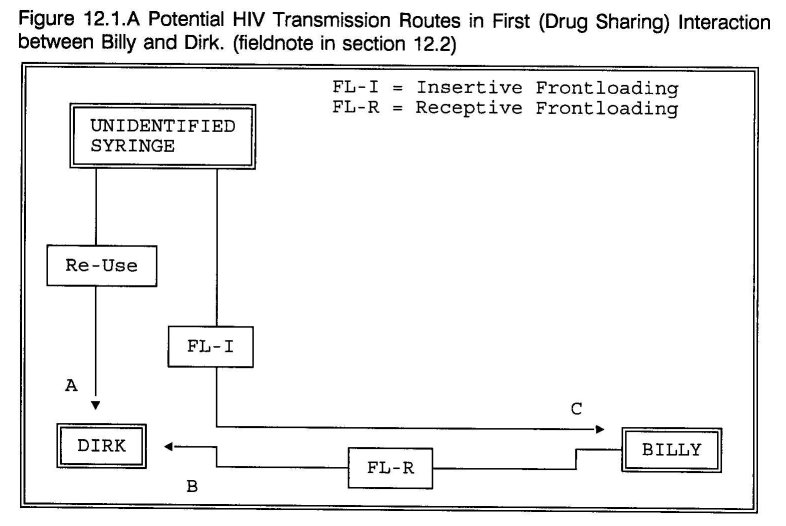

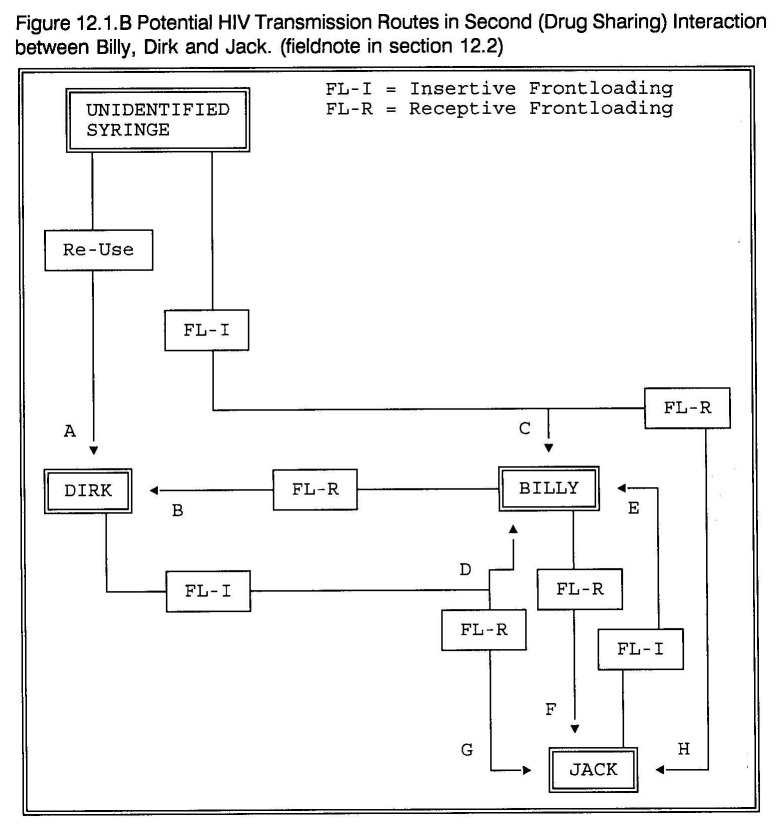

Figure 12.1.A plots the routes in the first interaction between Billy and Dirk. Dirk can become infected from the syringe he picked up (route A) and from receptive frontloading, that is, having Billy squirt the drug solution into his syringe (route B). Billy can become infected from insertive frontloading --inserting his needle in the syringe Dirk found (route C). These risks may have been exacerbated, as they inject cocaine. Preparing a shot of cocaine was done by cold shaking, without adding heat --which may affect the virus. Figure 12.1.B plots the routes in the succeeding interaction between Billy, Dirk and Jack. As in the preceding drug sharing interaction, Dirk can become infected from the syringe he found and from Billy's syringe (routes A and B). Billy can become infected from the syringe Dirk picked up, but now that Dirk used it, also from Dirk (routes C and D). He furthermore loads Jack's used syringe (insertive frontloading), which means a third infection possibility (route E). Through receptive frontloading Jack can become infected from Billy's needle (route F), but as Billy's needle may have picked up virus particles when loading the Syringe Dirk picked up, it can also transfer these to Jack's syringe (routes G and H).

Figure 12.1.A and 12.1.B clearly demonstrate the intricacy of risk behavior associated with drug injecting in groups. In these interactions infection could have taken place via at least 11 transmission routes.

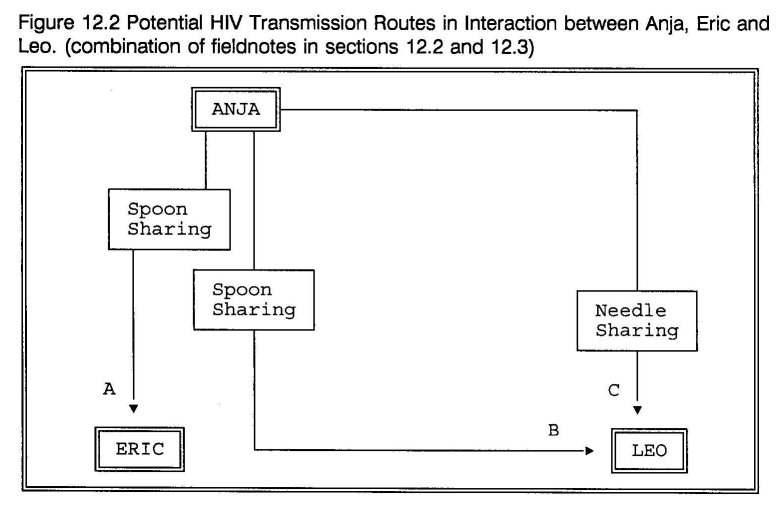

In the situation presented in figure 12.2 two distinct high risk interactions can be observed. Eric used Anja's spoon to prepare his shot (route A) and leo borrowed Anja's spoon (route B) and one of her used syringes (route C). Both the spoon and the syringe contain blood rests. All actors were aware of the potential risks of these exchanges. AIDS is not only discussed, but extensive efforts were undertaken to clean Anja's works before use. However, water is generally considered an insufficient disinfectant. (1 2) As a result, HIV may have been conveyed via three distinct routes.

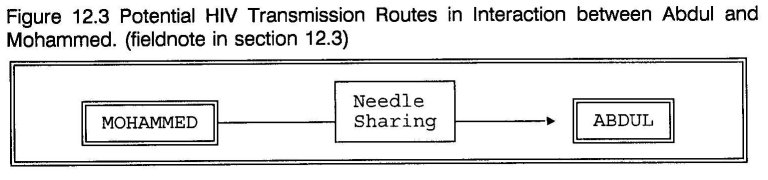

Figure 12.3 represents a situation in which the actors both possessed new syringes. They bought drugs from the money they made together. The drugs were divided by frontloading, but only because they both used new syringes this is without risk. But, nothing is so certain as the unexpected --by accident Abdul dropped his syringe and damaged the needle which resulted in an infection risk for Abdul.

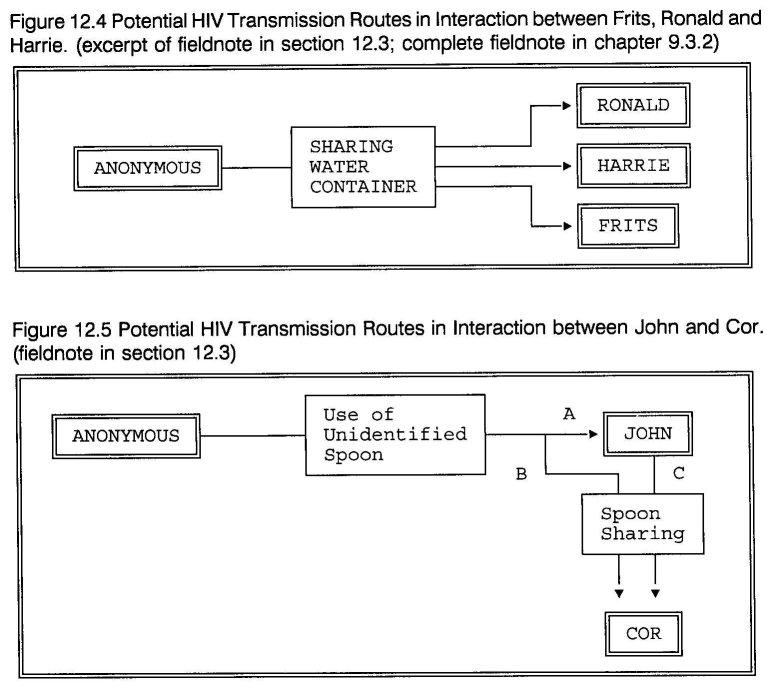

As all men in the situation presented in figure 12.4 used new syringes, again, this interaction appeared harmless. But in this case appearance is deceptive, as the use of the collective water container may have resulted in three routes of transmission.

Figure 12.5 indicates three routes of transmission: To prepare a shot of heroin John took a spoon from a cup, which contained several for common use (route A). Shortly after him, Cor used the same spoon to prepare a shot of cocaine (route B and C). The route leading from John to Cor may bear the highest risk (route C). Cor hardly cleaned the spoon before use and he cold-shaked his cocaine injection. The probability of viral transmission may have increased considerably, due to these two factors.

Transmission risks may further increase when filters are left in a used spoon and reused with that spoon. The routine sharing of spoons is often an unconscious practice. As pointed out, spoons belong to the standard inventory of most house addresses and are used by both IDUs and non-IDUs --who use spoons to prepare cocaine for smoking, normally using ammonia. Ammonia as well as lemon, ascorbic or vinegar --used to acidify the solution when preparing a heroin injection-- may affect the virus. (7) In particular ammonia seems to qualify. Spoons at addresses where both smoking and injecting is practiced may thus be safer, than those exclusively used by IDUs. Not only in the interactions in figures 12.1.A, 12.1.B and 12.5 spoons played a role, in the other cases they may also have been additional transmission vectors.

Except in the case presented in figure 12.5, the shared use of water containers and spoons, needle sharing and frontloading took place in the context of sharing drugs. This, again, demonstrates the drawbacks of the concept of needle sharing. It is too narrow to describe the intricate interactions that may put IDUs at risk for HIV-infection.

Increased availability of drugs is thought to affect consumption by increasing the prevalence of use. (14) Less attention has been given to the harmful effect of decreased availability of drugs. Availability-related variables, such as rising prices, decreasing purity, and unstable supplies can be seen as factors determining the onset of injecting. (15 16 17) The results presented in this dissertation show that if availability variables are held relatively stable over time, minimizing economic pressure to initiate and maintain injecting, a predominant smoking pattern can develop. Thus, injecting can be seen as adaptation to the conditions of decreased drug availability.

The availability of needles plays a major role in needle sharing. (16 18 19 20) A convincing illustration of this factor is the high prevalence of needle sharing in prison. (21) Traditionally, in the Netherlands, syringes have been easily obtainable. Since the AIDS epidemic the availability of syringes has increased due to the needle exchange programs. Furthermore, in contrast to other countries, the possession of injecting equipment has never been a cause of arrest in the Netherlands. (13 16 18 22 23) Risk of arrest discourages IDUs from carrying their personal injection equipment which limits so called on the spot availability, thereby increasing the frequency of sharing drug paraphernalia. The most dramatic indication of the importance of availability is the comparison of the low syringe sharing rates in the United Kingdom (24 25) and the Netherlands, (26) and the high rates in many cities of the U.S.A. (27)

The results of this field study support the hypothesis that under the conditions of stable availability of drugs and syringes and a decriminalization of possession, needle sharing decreases markedly. Nevertheless, research in Europe and the United States is documenting that IDUs are changing their behavior toward less risky injecting practices, despite the absence of Dutch conditions. (24 28 29 30 31 32) There seems to be a growing awareness of health and a willingness to use drugs in safer, more responsible ways. The field research found only a small incidence of irresponsible behavior in inexperienced IDUs or those experiencing craving intensified by cocaine. Several recent studies have shown a relationship between cocaine use, risk behaviors and HIV-serostatus. (33 34 35 36)

In numerous studies, the social organization of the drug subculture has also been associated with needle sharing. Drug users are often organized in small friendship groups. (37 38) These friendship groups are often linked in networks whose paramount activity is to obtain and distribute money and drugs (37 38) Both items are often shared and used together with other necessities of life. Sharing and its associated pattern of reciprocal aid provides a practical and emotional balance of the daily hardship of addict life. In the pre-AIDS era needle sharing fitted snugly into this pattern. Helping a fellow addict with a syringe was an expression of the almost universal subcultural code of share what you have. (39) These sharing behaviors function not only to satisfy individual craving, but also to support the maintenance of the network through the expression of community solidarity and the instrument of economic exchange. (37) In the AIDS era, needle sharing has lost its functionality, being transformed into a threat to the individual drug user, the friendship groups, networks, and the drug subculture as a whole. As with most cultural shifts, the process is gradual and never complete. Residues of the traditional code still remain and can be observed in emotional appeals and convenient lapses in newly acquired knowledge.

Paralleling other studies, the presented results show that, even under the most optimal conditions, IDUs can and do get into situations in which sterile injection equipment is not available. In contrast with novice IDUs, experienced injectors are likely to be more competent in managing such situations. (24 40) Continued risk behavior among IDUs has been associated with perceived availability (41 42) and group differences in obtainability, whereas minority IDUs experience more problems in acquiring new syringes. (43) Poly drug use, benzodiazepine use, psychiatric problems and fatalism are also associated with needle sharing, (44 45 46) as was injecting at shooting galleries.(44 47) These factors may, however, largely correlate with social factors, which negatively impact on a person's life structure, such as unstable living conditions, homelessness, poverty and absence of perspective on improvement. (13 25 46 48)

In conclusion, these findings suggest that needle sharing often is the outcome of structurally or situationally determined social interaction. Knowledge alone is not enough to counter the pressure of social interaction and drug craving. If clean syringes are not easily available in these stressful situations, the magnitude of addiction will ultimately lead IDUs to unsafe injection practices. While easy access and sufficient supply of clean syringes is effective, as van de Hoek, et al. conclude, (26) it is not enough. They recommend intensive counseling in future prevention education efforts. The findings also support their suggestion by identifying a number of factors that determine needle sharing. These factors should be addressed in counseling that focuses on the practical skills of safe drug use. Furthermore, the results indicate that changes in the social environment may be more important than changes in individual risk behaviors. Prevention efforts may be made more effective through the mobilization of collective social resources directed at preventing risk situations. IDUs and their networks should have a prominent role in such approaches, an idea that is getting more attention. (49 50) In Rotterdam the findings have shown that outreach programs that work together with IDUs to reinforce positive protective factors such as rules of safe use while, at the same time, distribute syringes to unknown IDUs via known ones can be effective in changing the environment (see chapter 14). Utilizing the knowledge of drug users and their information and exchange networks in promoting risk reduction through peer education and peer support might offer more perspective on a lasting behavior change than any other prevention effort.

- Resnick L, Veren K, Salahuddin SZ, Tondreau S, Markham PD: Stability and inactivation of HTLV- III/LAV under clinical laboratory environments. JAMA 1986; 255: 1887-1891.

- Martin LS, McDougal JS, Loskoski SL: Disinfection and inactivation of the human T-lymphotropic virus type III/lymphadenopathy-associated virus. J Infect Dis 1985; 152: 400-403.

- Wikler A: A theory of opioid dependence. In: Lettieri DJ, Sayers M, Pearson HW (eds.): Theories on drug abuse. Rockville, Md: National Institute on Drug Abuse, 1980.

- Barre-Sinoussi F, Nugeyre MT, Chermann JC: Resistance of AIDS virus at room temperature. Lancet 1985; 2: 721-722.

- Koester S, Booth R, Wiebel W: The risk of HIV transmission from sharing water,drug-mixing containers and cotton filters among intravenous drug users. International Journal on Drug Policy 1990, 1(6): 28-30.

- McDougal JS, Martin LS, Cort SP, Mozen M, Heldebrant CM, Evatt BL: Thermal inactivation of the Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome Virus, Human T Lymphotropic Virus-III/Lymphadenopathy- associated Virus, with special reference to antihemophilic factor. Journal of Clinical Investigation 1985; 76: 875-877.

- Goldberg DJ, FLynn N, Green ST, Jain S, Watson H, Keddie E: The disinfectant potential of vinegar solutions used by Glasgow IDUs to prepare heroin for injection. Poster presentation V International Conference on AIDS, Montreal, Canada, 1989. [Abstract no. Th.D.P.55]

- Gaughwin MD, Gowans E, Ali R, Burrell C: Bloody needles: the volumes of blood transferred in simulations of needlestick injuries and shared use of syringes for injection of intravenous drugs. AIDS 1991; 5: 1025-1027.

- Hoffman PN, Larkin DP, Samuel D: Needlestick and needleshare --the difference. J Infect Dis 1989; 160: 545-546.

- Grund JPC, Stern LS: Blood rests in Syringes; Not only the size matters, but also the type of syringe. AIDS 1991; 5(12): 1532-1533.

- Friedland G, Klein R: Transmission of the human immunodeficiency virus. New Engl J Med 1989; 321: 1621-1625.

- Froner G: Digging for diamonds: A lexicon of street slang for drugs and sex. San Francisco: Health outreach team productions, 1989.

- Murphy S: Intravenous drug use and AIDS: notes on the social economy of needle sharing. Contemporary Drug Problems 1987; 14: 373-395.

- Goldstein A, Kalant H: Drug policy: striking the right balance. Science 1990; 249: 1513-1521.

- Casriel C, Rockwell R, Stepherson B: Heroin sniffers: between two worlds. J Psychoactive Drugs 1988; 20(4): 37-40.

- Power RM: The influence of AIDS upon patterns of intravenous Use- Syringe and Needle Sharing- among illicit drug users in Britain. In: Battjes RJ, Pickins RW (eds): Needle sharing among intravenous drug abusers: National and international perspectives. Rockville: NIDA, 1988: 75-88.

- Parker H, Bakx K & Newcombe R: Living with heroin: The impact of a drugs 'epidemic' on an English Community. Philadelphia: Open University Press, Milton Keynes, 1988.

- Feldman HW, Biernacki P: The ethnography of needle sharing among intravenous drug users and implications for public policies and intervention strategies. In: Battjes RJ & Pickins RW (eds.): Needle sharing among intravenous drug abusers: National and international perspectives. Rockville: NIDA, 1988: 28-39.

- Robertson JR, Bucknall ABV, Welsby PD, Roberts JJK, Inglis JM, Peutherer JF, Brettle RP: Epidemic of AIDS related Virus (HTLV-III/LAV) infection among intravenous drug abusers. BMJ 1986; 292: 527-529.

- Newmeyer JA, Feldman HW, Biernacki P, Watters JK: Preventing AIDS contagion among intravenous drug users. Medical Anthropology 1989; 10: 167-175.

- Rahman MZ, Ditton J, Forsyth JM: Variations in needle sharing practices among intravenous drug users in Possil (Glasgow). British Journal of Addiction 1989; 84: 923-927.

- Olievenstein C: Drug addiction and AIDS in France in 1987. In: Battjes RJ, Pickins RW (Eds.): Needle sharing among intravenous drug abusers: National and international perspectives.Rockville: NIDA, 1988, pp 114-118.

- Pascal CB: Intravenous drug abuse and AIDS transmission: Federal and state laws regulating needle availability. In: Battjes RJ & Pickins RW (Eds.):Needle sharing among intravenous drug abusers: National and international perspectives.Rockville: NIDA, 1988, pp 119-136.

- Stimson GV, Alldritt LJ, Dolan KA, Donaghoe MC, Lart RA: Injecting equipment exchange schemes: final report. London: Monitoring Research Group, 1988.

- Donaghoe MC, Dolan KA, Stimson GV: Life style factors and social circumstances of syringe sharing in injecting drug users. London: Centre for Research on Drugs and Health Behaviour, 1991.

- Hoek JAR van den, Haastrecht HJA, Coutinho RA: Risk reduction among intravenous drug users in Amsterdam under the influence of AIDS. Am J Public Health 1989; 79: 1355-1357.

- Battjes RJ, Pickins R, Amsel Z: Trends in HIV-infection and AIDS risk behaviors among intravenous drug users in selected U.S. cities. presented at the VII International Conference on AIDS, Florence, Italy, 1991. [Abstract no. Th.C.46].

- Kokkevi A, Alevizou S, Stefanis C: AIDS related behavior and attitudes among IV drug users in Greece. presented at the V World AIDS Conference, Montreal, Canada, 1989. [abstract no. TH.D.P.72]

- Guydish J, Abramowitz A, Woods W, Newmeyer J: Sharing needles: Risk reduction among IVDU's in San Francisco. presented at the V World AIDS Conference, Montreal, Canada 1989. [abstract no. TH.D.P.34]

- Des Jarlais DC, Friedman SR, Hopkins W: Risk reduction for the acquired immune deficiency syndrome among intravenous drug users. Annals of Internal Medicine 1985; 103: 755-759.

- Kall KI, Olin RG: HIV status and changes in risk behavior among intravenous drug users in Stockholm 1987-1988. AIDS 1989; 4: 153-157.

- Watters JK, Cheng Y, Segal M, Lorvick J, Case P, Carlson J: Epidemiology and prevention of HIV in intravenous drug users in San Francisco. VI International Conference on AIDS, San Francisco, U.S.A. 1990 [Abstract no. F.C.106].

- Wiebel W, Ouellet L, Guydan C, Samairat N: Cocaine injection as a predictor of HIV risk behavior. presented at the VI International Conference on AIDS, San Francisco, USA 1990. [abstract no. F.C.767]

- Schoenbaum, EE, Hartel, D & Friedland GH: Crack use predicts incident HIV seroconversion. presented at the VI International Conference on AIDS, San Francisco, USA 1990. [abstract no. Th.C.103]

- Woods WJ, Abramowitz A, Guydish J, Clark W, Hearst N, Kiefer R: Predicting needle sharing behavior of IVDUs in treatment. presented at the V International Conference on AIDS, Montreal, Canada, 1989. [Abstract no. W.D.P.74]

- Clark W, Guydish J, Abramowitz A, Woods WJ, Sorensen J: Cocaine use associated with increased risk for IVDUs who share needles. presented at the VI International Conference on AIDS, San Francisco, U.S.A., 1990. [Abstract no. F.C.764]

- Des Jarlais DC, Friedman SR, Sotheran JL, Stoneburger R: The sharing of drug injection equipment and the AIDS epidemic in New York City: The first decade. In: Battjes RJ & Pickins RW (eds.): Needle sharing among intravenous drug abusers: National and international perspectives. Rockville: NIDA, 1988: 160-175.

- Preble E, Casey JJ: Taking care of business - the heroin user's life on the street. Int J Addict 1969; 1: 1- 24.

- Wieder DL: Telling the code. In: Turner R (ed): Ethnomethodology: selected readings. Middlesex, England: Penguin Education, 1974: 144-172.

- Schilling R, El-Bassel N, Schinke S, Botvin G: Risk behavior and attitudes among recovering IV drug users. Presented at the V World AIDS Conference, Montreal, Canada, 1989. [abstract no. TH.D.P.42]

- Rezza G, Fausto T, Tempesta E, Di Giannantonio M, Weisert A, Rossi GB, Verani P: Needle sharing and other behaviours related to HIV spread among intravenous drug users. AIDS 1989; 3: 247-248.

- Carballo M, Rezza G: AIDS, drug misuse and the global crisis. In: Strang J, Stimson G: AIDS and Drug Misuse. London and New York: Routledge, 1990: 16-26.

- Ostrow DG: AIDS prevention through effective education. Deadalus 1989; 118(3): 229-254.

- Klee H, Faugier J, Hayes C, Boulton T, Morris J: AIDS related risk behavior, polydrug use and temazepam. British Journal of Addiction 1990; 85: 1125-1132.

- Metzger D, Woody G, De Philippis D, McLellan AT, O'Brian CP, Platt JJ: Risk Factors for Needle Sharing among Methadone-treated Patients. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:636-640.

- Murphy S, Waldorf D: Kickin' down to the street doc: Shooting galleries in the San Francisco Bay Area. Contemporary Drug Problems 1991; 18(1): 9-29.

- Schoenbaum EE, Hartel D, Selwyn P, Klein RS, Davenny K, Rogers M, Feiner C, Friedland G: Risk factors for human immunodeficiency virus infection in intravenous drug users. New England Journal of Medicine 1989; 321(13): 874-879.

- Klee H, Faugier J, Hayes C, Boulton T, Morris J: Factors associated with risk behavior among injecting drug users. AIDS Care 1990; 2: 133-145.

- Des Jarlais DC, Friedman SR: Shooting galleries and AIDS: Infection probabilities and 'tough' policies. Am J Public Health 1990; 80: 142-144.

- Chitwood DD, McCoy CB, Inciardy JA et al.: HIV seropositivity of Needles from Shooting Galleries in South Florida. Am J Public Health 1990; 80: 150-152.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|