DRUG SHARING AND HIV TRANSMISSION RISKS: FRONTLOADING AND BACKLOADING AMONG INJECTING DRUG USERS

| Books - Drug Use as a Social Ritual |

Drug Abuse

DRUG SHARING AND HIV TRANSMISSION RISKS: FRONTLOADING AND BACKLOADING AMONG INJECTING DRUG USERS

Drug users are at risk for the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and other viral and microbiological infections. Although recently non injecting drug use related HIV has been reported (1 2 3 4), particularly injecting drug users (IDUs) are at risk, because of the use of contaminated injection equipment, generally termed needle sharing. (5 6) (Throughout the text, unless otherwise specified, the term needle sharing refers to the sharing of both needles and syringes.) On the basis of extensive research, needle sharing seems to be the most significant AIDS-related risk behavior practiced by IDUs. (5 6 7 8) Moreover, in the chain of transmission, the IDU seems also to be the main vector for secondary HIV spread to the heterosexual population in the U.S. (9 10)

In contrast with the United States and many neighboring countries, only a minority of drug users inject in the Netherlands. Most Dutch heroin users smoke their heroin and cocaine from tinfoil (chinesing or chasing the dragon). The availability, purity, and price of these drugs on the Dutch illegal market have stabilized over the years at relatively high levels and moderate prices, compared with neighboring countries and the United States. These economic factors were prerequisites for the diffusion (11) of the Asian practice of heroin smoking into the Dutch heroin using population. Mainly because of these economic factors, many Dutch users do not feel the necessity to inject, as do most of their foreign counterparts. (12 13 14) However, the IDU minority have not been overlooked. Since the mid 1970s harm reduction strategies for all drug users were adopted by Dutch governmental (15) and helping organizations. (16) Around 1985 AIDS became a major item of concern in the Netherlands. In 1984 Amsterdam started its needle exchange system. The number of needles that were distributed grew rapidly from 25.000 in 1984 to 820.000 in 1989. (17) Rotterdam started its municipal needle exchange system in the first half of 1987. The total number of needles distributed is considerably lower than in Amsterdam, respectively 196700 in 1988, 251700 in 1989, 223200 in 1990 and 231300 in 1991. (18)

Few HIV seroprevalence studies have been conducted in the Netherlands. In a selected group that may not represent all drug users in Amsterdam, van den Hoek et al. found a seroprevalence of 33 percent at entry into the study. (19) A study outside the large urban centers indicates a seropositivity of 4.8 percent in a non-representative sample. (20) In a Rotterdam study of a sample of extreme problematic drug users in methadone maintenance seropositivity was found to be 9.7 percent in 1986 and 6.5 percent in 1987. (16) Unpublished results from a 1988 study of an intake cohort of a drug treatment introduction program in the Hague show a seroprevalence of 0%. (21) As a comparison, self-reported lifetime prevalence of hepatitis among methadone clients in Rotterdam is 21 percent, for gonorrhea 24 percent and for syphilis 7 percent. (22)

HIV is undoubtedly transmitted through needle practices. Nonetheless, especially in situations where clean syringes are readily available it is not merely the act of sharing needles that constitutes the risks of spreading the virus. The behaviors associated with needle sharing can be decomposed into different components that each have their own distinctive probability of risk. The hypothesis of this chapter is that a deeper look into drug use contexts reveals other forms of sharing behavior that may be important factors in the transmission of HIV. A look beyond needle sharing involves a look into a world of multiple sharing and care taking practices that constitute the bonds of relationships of IDUs' social networks. These relationships are multidimensional and may lead to relationships with non-IDUs. For analytic purposes three patterns of sharing behavior directly related to HIV-transmission risks can be distinguished: 1) sharing, (including lending and passing on) syringes or needles; 2) sharing of other drug injection paraphernalia; 3) drug sharing. Specifically, certain forms of drug sharing may provide additional routes by which contaminated needles can present risks of infection to IDUs. In this chapter, a look beyond needle sharing is presented and one such drug sharing practice - frontloading - is described.

Chapter nine demonstrated that the use of heroin and cocaine among the research participants is embedded in a social structure that facilitates the use of these drugs. In addition, this social structure also functions as a social support system for the users. It was shown that valuable items, such as housing, food and clothing are shared on a regular basis in friendship and acquaintance networks. Users were observed to frequently help each other with daily problems associated with a lifestyle in which the use of drugs is the most important (and thus overwhelmingly demanding) value. Furthermore, in this social structure they socialize and find moral support.

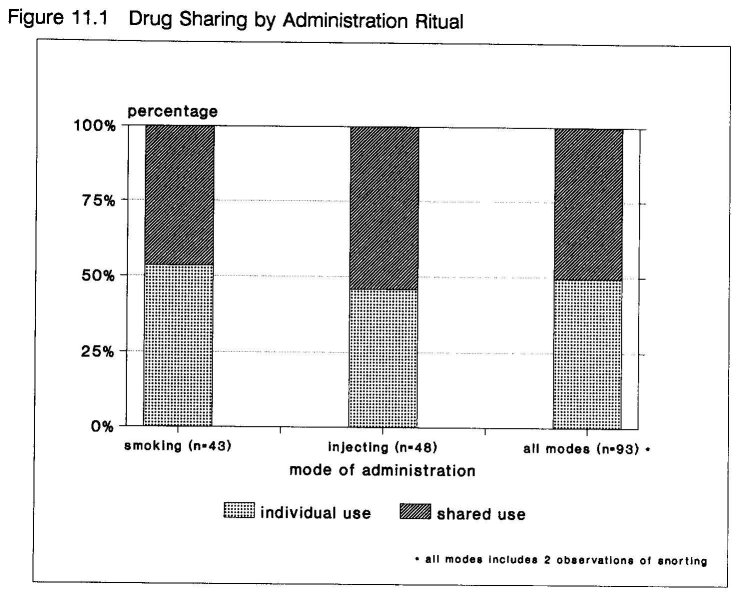

In this context of social support in drug user networks the sharing of drugs is an important and frequent phenomenon. Quantitative analysis of the observations of drug self- administration rituals clearly shows that drug use rarely is an individual act. The most common places where drugs were ingested are the dealing place (56%), home (18%), and a friends home (14%) (see figure 9.1 in chapter nine). Likewise, 43 of 62 observed drug sales at house addresses were followed by direct ingestion of (at least a part of) the purchased drugs. The mean number of people present at these places during the observed drug taking event was 4.3. As the vast majority of drugs is consumed at other places then home and with other people around, it was not surprising that drugs were shared in 50% (N = 93) of observed events (see figure 11.1). Chapter nine discussed the instrumental and social (i.e. social) functions of drug sharing, that are largely equal for smoking and injecting drug users. The proceeding sections will focus on the techniques commonly used when IDUs share drugs.

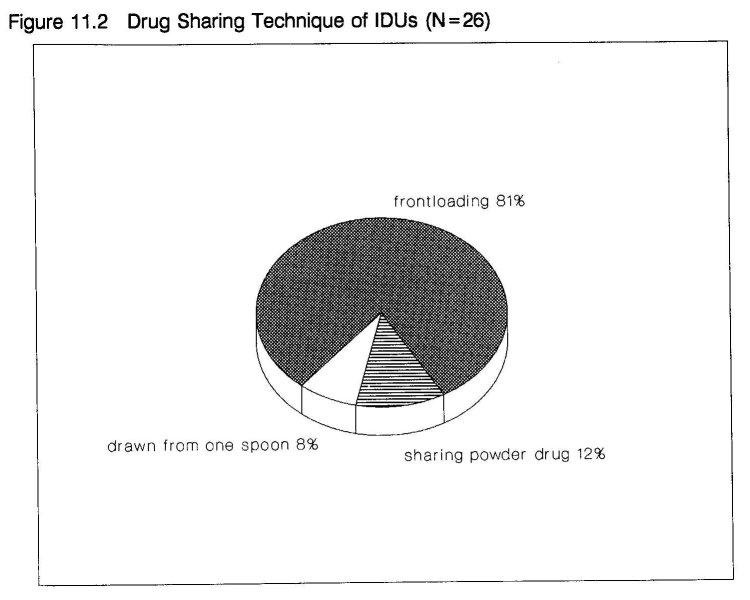

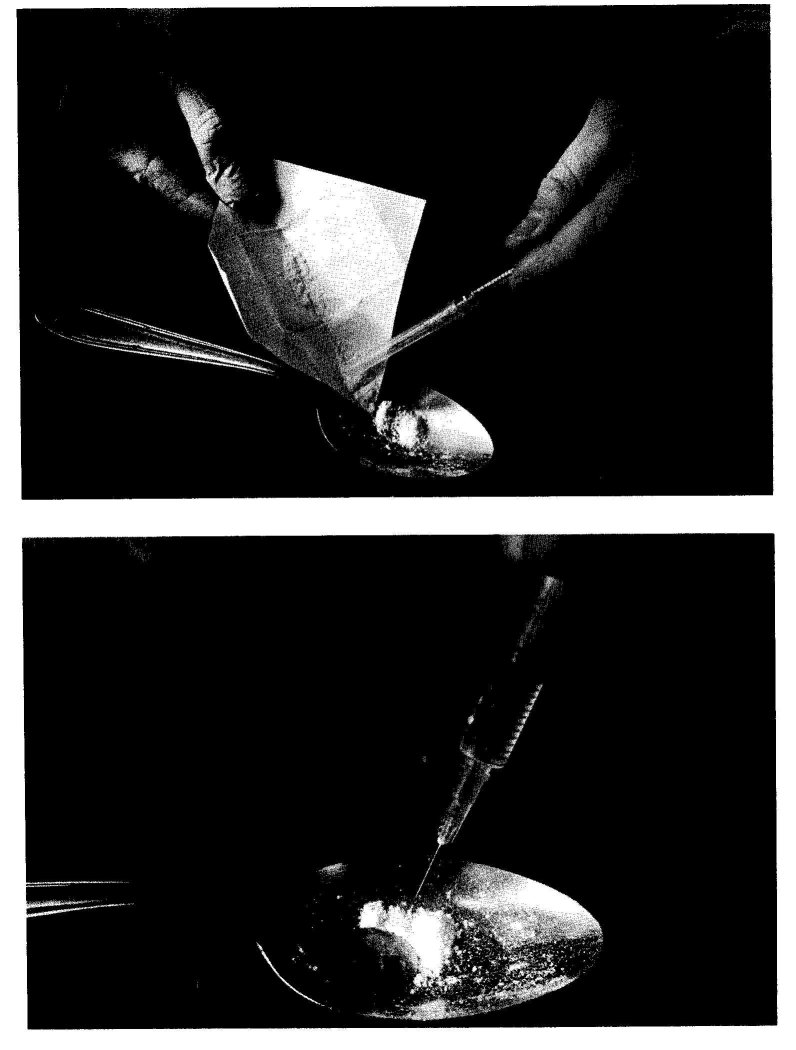

In 81% of observed sharing events among IDUs (N = 26), the drugs were shared by frontloading or streepjes delen (sharing stripes; referring to the scale gradients on the barrel of the syringe). This practice involves a special technique using two syringes (see figure 11.2). When sharing by frontloading, the drug is prepared on one spoon and then drawn in one syringe (A). From the second syringe (B) the needle is removed and the plunger is drawn back and by spouting a part of the solution from syringe A through the hub of syringe B, the drugs are divided. In this way the drugs can be divided into two or more equal parts (see photo sequence).

The following fieldnote documents a representative situation in which drugs are shared by frontloading. Richard and Chris have bought drugs at a dealing place and have gone home to inject:

Back home Richard and Chris start preparations to shoot up a 'cocktail' (a mixture of cocaine and heroin, also called a speedball). Chris and Richard both get tools and put them on the table. They sit down at the same time. Richard puts the spoon in front of him and takes out the packages. He opens the heroin package, holds it above the spoon and empties it. He adds some lemon and water. Meanwhile Chris opens two injection swabs and puts them on the broad rim (edge) of the ash-tray. When Richard is ready putting things into the spoon he nods, which Chris understands as a sign to put the swabs on fire with his lighter. This produces a flame +4 cm high, above which Richard now holds the spoon to boil the contents. Chris looks interestingly into the spoon and says: "I hope it's enough that we feel it." It takes something more then 2 minutes to dissolve the heroin. After this Richard puts in the cocaine almost immediately, without waiting for the solution to cool off. Cotton is used to make a filter, and Richard draws the cocktail in the syringe without the needle. Richard also divides the cocktail. He puts the needle back on his syringe. Chris gives him his syringe after removing the needle. Richard inserts his needle in Chris' syringe and pushes the piston. Before doing so he looks how much cocktail is in his syringe, so he knows how much to put over. He then holds the 2 syringes side by side to compare the contents. In one of them is a little more. That one he gives to Chris.

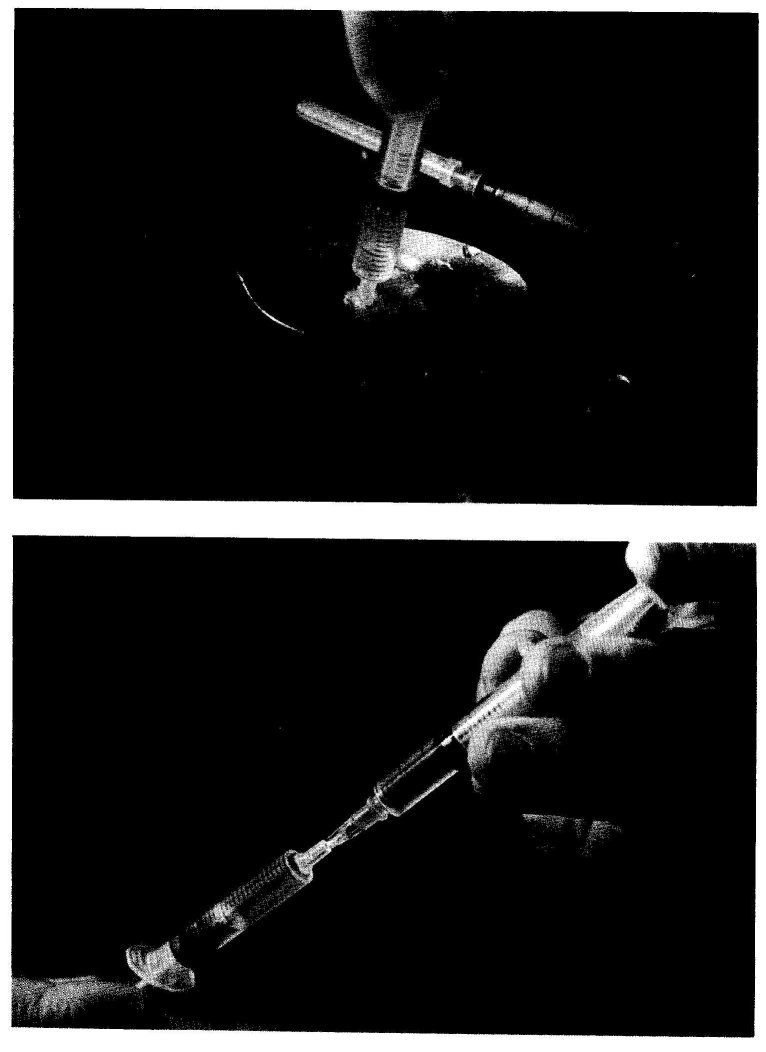

Except when the spoon is well cleaned and both the syringes are new or effectively cleaned (e.g. by bleaching) there is an increased risk of passing microbiological or viral infections, when utilizing this technique. The most obvious direction of transmission is from A to B as in syringe A present blood rests are diluted in the drug solution. However when inserting A into B, the needle of A can get into contact with virus particles (e.g. in old blood) in the hub of syringe B. This practice is only one of the many possible ways to utilize syringes in sharing drugs. Spouting from the donor syringe into the recipient syringe was most often observed, but it is, of course, also possible to draw the liquid from the donor syringe. This can be termed reversed frontloading. In order to frontload, the needle of at least one of the syringes involved in the drug sharing event must be removable (so that a needle can be inserted).

Where syringes with fixed needles (mostly 1 ml insulin) are the standard a similar technique has evolved, called backloading. This procedure was demonstrated by a female IDU from London:

The drug solution is one of the insulin syringes. She pulls the plunger out of the other syringe and holds the barrel almost horizontal. Slowly she spouts half of the solution in the back opening. "You need to do it very precisely. It must not go in all the way. There needs to stay some air between the liquid and the needle, otherwise you fuck up." Just as she explains, the liquid accumulates ± 1 cm from the back of the needle. She puts down the donor syringe, picks up the plunger and carefully holds it against the opening. In one smooth movement she pushes the plunger a little into the barrel, while simultaneously turning the needle upwards. "This is the crucial move", she explains, "I've seen several people blow shots doing it --squirting the shot into the air. Mostly when they were sick --shaking hands, you know."

From this demonstration it can be assessed that backloading requires a considerably more skilled hand than frontloading. Sometimes a certain quantity of drug solution is prepared in advance and stored in a syringe. This solution is then consumed in several shots over a given period of time --either alone or shared with other users.

Social Implications of Drug Sharing

Drugs are shared for an intertwined complex of social and economic reasons. In the observed sharing events 68% involved social incentives and in 83% economic. Many events fit into both economic and social categories. As illustrated in the last fieldnote, heroin users frequently share the drugs they buy together. At house addresses one pays less if purchasing in quantity. Therefore, it is rational to pool money and jointly buy drugs. Thus sharing results in more drugs for the individual for the same amount of money. Likewise, dealer/users may give a betermakertje or mazzeltje to someone without money for the sake of customers relations. But this kind of credit is not evenly distributed to all customers. Nor is it over time. Dealers must take several factors into account. They must control their financial balance and anticipate their clients' financial position, but they must also remain on good terms with their friends. They do not want to acquire the image of being in it just for the money and become alienated from their personal network. Helping with a betermakertje is a customary motivation for drug sharing, not limited to dealers. The term helping is common vocabulary and refers to the revered communal rule of helping a fellow user who is in withdrawal (see chapter nine).

A frequent sharing situation highly resembles that of being among friends in a pub. The users sit around a table, talk in a sociable atmosphere and share the available drugs. Mostly this concerns smokers, as IDUs spend less time at house addresses. Participation in shared drug taking activities (e.g. buying and using at the same house addresses) results over time in more structural relationships among individuals. By sharing drugs users make new contacts and existing ones are reinforced. Indeed, drug use is not the only factor that brings and keeps drug users together. They engage in many common activities and they spend considerable time on social and other conventional activities. (23 24) Moreover, the relations of the observed drug users were often much more intense and multiplex. Drugs were often shared among sexual partners, family, or people sharing living arrangements. A significant percentage (23%) of the IDUs observed to share drugs were typical running mates or dyads. The acquisition and use of drugs is an essential binding element in these dyadic relationships. (25 26) The following fieldnote provides an illustration.

Meanwhile they are telling how they came together, live together, etc. They're together for +5 weeks now. Chris: "We share everything; social benefit, food, dope, etc." Richard: "For instant tomorrow Chris gets his benefit and I get dope for it. Friday I'll get my money and we use that to buy dope." He goes on: "We go together into town every day, first to get methadone and then to make money."

The bond between running partners is believed to be "the strongest positive relationship within the IV-drug use subculture" and a "substitute for family". (27)

Drug sharing as described in this chapter is based on a study of a Dutch population; that is, in a situation of relatively low criminalization of drug use and relatively high availability of both drugs and syringes. However, drug sharing is embedded in a much broader pattern of social behaviors of heroin users, which includes the sharing of many necessaries of life. Although the frequency of these sharing behaviors could be influenced by the Dutch normalization policy, (28 29) enabling drug users to reflect the social responsibility, characteristic for Dutch society, (30) in essence they are almost universal in drug subcultures and have been documented in many studies in different times and places. (25 31 32) Sharing fits the broader context of drug user's lives and finds its function in coping with craving, human contact and needs, and life on the margins of society. As Mata and Jorquez put it:

Efforts to curb injecting drug use and needle sharing must begin with the understanding that these practices are embedded and maintained by a set of ongoing personal relations and exchanges in injecting drug users' personal social networks. Needle sharing must be seen as part of the larger picture of drug sharing practices. Drug sharing is at once a means to socialize, to belong, and to provide some measure of protection from the exigencies of la vida loca. More immediately, it is a means to cope with one's craving for drugs (31).

Both the helping and sharing (as well as the ripping and violence) characteristic of the subcultures of heavy drug users, are normal behaviors under abnormal or extreme circumstances. They can be compared with similar behaviors in high stress situations, such as in war and concentration camps. (33 34) Without a little help from your friends it is impossible to survive in the tough parallel world of users, dealers and police. In this context, sharing balances the constraints, the ripping and running (35), the competition, violence and mistrust of daily life. Then, drug sharing is an integrating ritual sanctioning a common lifestyle and strengthening mutual ties. (36)

Virological and Epidemiological Implications of Drug Sharing

The presented data suggest that the drug sharing technique of frontloading can be an alternative route of viral transmission. An important issue, regarding HIV transmission is the survival of HIV in blood rests in a syringe. It has been demonstrated that the virus can be detected up to 30 days (37) and even in syringes without visible remnants of blood. (38) The presumed infectivity of Western Blot-positive blood (39) supports the notion that positive tested syringes are potentially infectious when used by other IDUs. Moreover, the interval of 30 days must be regarded as an extremely long period between use and re-use of syringes of IDUs. It is much more plausible that a syringe is used several times a day, especially when cocaine is involved, or when employed at shooting galleries. In this research it was found that when IDUs shared drugs by frontloading, the interval between two shared doses was sometimes even less than half an hour. Furthermore, the upsurge of injecting cocaine use may have additional consequences. Recent findings indicate that cocaine can exacerbate HIV-1 transmission and infection in drug users. (40)

First publication of the findings on frontloading, prompted two American studies into the frequency of frontloading and its association with HIV infection. Among a sample of IDUs in Baltimore, Samuels et al. found no significant association. (41) However, the most recent findings come from New York and support the hypothesized infectivity of frontloading. Frontloading was widespread in this study. During the two years before the interview almost 40% (80/207) of subjects frontloaded, as did 30% (63/210) during the past 30 days. A strong association with HIV infection was reported. HIV seroprevalence was 71% among IDUs who frontloaded during the last two years and 36% among those who did not. (42)

The technique of frontloading and similar techniques are known far beyond the research sites of this study. This hypothesis is supported by the data and other research. Sharing drugs is a common phenomenon. An evaluation of a needle exchange program in a small Dutch town showed that 67% of the exchangers were preparing collective doses. (43) The observations of frontloading in this research were recorded in different friendship groups and networks. In addition, a considerable number of the IDUs in this study have at times kept residence in other Dutch or foreign cities. Some have their roots in other cities, others come from neighboring countries. Another obvious ground for sharing drugs by frontloading is that it is the most efficient and honest way to split a certain amount of drugs in two or more portions. When dividing the powdered drugs it is very difficult to cut them into equal amounts without a scale of some sort. By frontloading the solution can rather simply be proportionated because most syringes have scale gradients on them. This is a powerful incentive when dealing with goods that on a street level outweigh the price of gold 4 to 20 times. Furthermore, experienced IDUs are highly familiar with the instrument that is indispensable for their preferred route of getting high. In that respect, they are certainly the experts. When questioned on frontloading, a London female IDU colorfully explained while demonstrating backloading with two 1 ml insulin syringes:

"Yeah, I know what you mean. But because most users use these 'fits' (she points at the insulin syringes, which have fixed needles), we do it like this. [demonstrates backloading] ... Hey, we live with this thing --go to bed with it and get up with it. We know it inside out. Played with it, did everything what you can think of. Makes splitting gear (heroin) easy and fast, get it? Everybody knows that."

Indeed, around the world IDUs know what is and is not possible with syringes and needles and what serves their needs best. For the purpose of a fair share, frontloading and backloading apparently qualify everywhere. In Warsaw, Poland --where syringes are extremely scarce-- frontloading was observed at a dealer's house. This dealer had two sets. One he used himself. The other syringe had a double function. The dealer sold self-produced compote. In transactions the second syringe was used to measure and transfer the requested quantity in the client's syringe. It was, however, also lent to clients, who did not possess their own set. (44) Frontloading has been observed in drug sharing events in the Bronx (New York City) and Los Angeles (45), and reported in Baltimore. (41) In South Florida it is used in a procedure to prepare speedball, (46) It seems also common practice in Barcelona, Spain (47) and in several Swiss cities, such as Basel, Bern and Zürich. (48) Backloading has been documented in New York, (42) San Francisco (49) and Denver (50) in the USA, in London, Great Britain (51) and in Barcelona, Spain. (47)

The AIDS epidemic among IDUs highlights the importance of basic knowledge of lifestyles, behaviors and interactions of drug users in their social networks. The thesis of this chapter has been that a deeper look into this natural territory may reveal unknown and, for HIV prevention important matters. One such matter, the practice of frontloading has been presented. Research results on its infectivity are starting to become available. The negative results from Baltimore may well be related to methodological problems, as the New York study shows a very strong association. In addition to needle sharing, frontloading can be an important factor in the spread of HIV among IDUs. Until recently, this has been overlooked by most researchers as well as by IDUs who may otherwise avoid needle sharing and/or other risk practices. In the Netherlands, where there actually is a high availability of sterile syringes and where the actual sharing of needles and syringes has decreased significantly, (52 53) frontloading could even become a main route of HIV-spread. Thus, needle sharing is a definitionally incomplete notion. The term is a rough simplification of a very complex reality. Interactions of patterns, situations and socio-cultural factors involved in illegal drug use contribute considerably to the spread of HIV. Further research efforts into drug sharing practices and related issues should enhance scientific appreciation of these socio-cultural factors. On the other hand, prevention efforts aimed at filling such gaps in drug users' knowledge of HIV-risks need to be given urgent attention. In the Netherlands, the described findings have been implemented in printed prevention materials for IDUs, that are distributed by drug treatment agencies. (54) As only a minority of drug users at any given time are in daily contact with treatment and helping agencies, the methods used to disseminate this knowledge should involve a permanent street education process of active IDUs and equipping them with the necessary tools to change their behavior in the desired direction.

- Sterk C: Cocaine and HIV seropositivity. Lancet 1988, 1:1052.

- Schoenbaum EE, Hartel D, Friedland GH: Crack use predicts incident HIV seroconversion. presented at the VI International Conference on AIDS, San Francisco, USA 1990. [abstract no. Th.C.103]

- Golden E, Fullilove M, Fullilove R, Lennon R, Porterfield D, Schwartz S, Bolan G: The effects of gender and crack use on high risk behaviors. presented at the VI International Conference on AIDS, San Francisco, USA 1990. [abstract no. F.C.742]

- Chiasson MA, Stoneburger RL, Hildebrandt DS, Telzak EE, Jaffe HW: Heterosexual transmission of HIV associated with the use of smokable freebase cocaine (crack). presented at the VI International Conference on AIDS, San Francisco, USA 1990. [abstract no. Th.C.588]

- Brettle RP: Epidemic of AIDS related virus infection among intravenous drug abusers. BMJ 1986; 292: 1671.

- Chaisson RE, Moss AR, Onishi R, Osmond D, Carlson JR: Human immunodeficiency virus infection in heterosexual intravenous drug users in San Francisco. Am J Public Health 1987; 77: 169-172.

- Marmor M, Des Jarlais DC, Cohen H, et al.: Risk factors for infection with human immunodeficiency virus among intravenous drug abusers in New York city. AIDS 1987; 1: 39-44.

- Hoek JAR van den, Coutinho RA, Haastrecht HJA van, Zadelhoff AW van, Goudsmit J: Prevalence and risk factors of HIV infections among drug users and drug using prostitutes in Amsterdam. AIDS 1988; 2: 55-60.

- Newmeyer JA: The role of the IV drug user and the secondary spread of AIDS. Street pharmacologist 1987; 11(11): 1-2.

- Moss AR: AIDS and intravenous drug use: the real heterosexual epidemic. BMJ 1987; 294: 389-390.

- Katz E, Levin ML & Hamilton H: Traditions of research on the diffusion of innovations. Am Sociol Rev 1963; 28: 237-252.

- Casriel C, Rockwell R, Stepherson B: Heroin sniffers: between two worlds. J Psychoactive Drugs 1988; 20(4): 37-40.

- Burt J, Stimson GV: Report of in-depth survey of intravenous drug use in Brighton. London: Monitoring Research Group, 1988.

- Power RM: The influence of AIDS upon patterns of intravenous Use- Syringe and Needle Sharing- among illicit drug users in Britain. In: Battjes RJ, Pickins RW (eds.): Needle sharing among intravenous drug abusers: National and international perspectives. Rockville: NIDA, 1988: 75-88.

- Engelsman EL: Dutch policy on the management of drug related problems. Br J Addict 1989; 84: 211-18.

- Barends W: Routinematig HIV-onderzoek in een Rotterdams methadonprogramma. Medisch Contact 1988; 43(2): 58-60.

- Buning EC: DE GG&GD en het drugprobleem in cijfers, deel IV. Amsterdam: GG&GD, 1990.

- Geurs R: Spuitomruil in Rotterdam. Een evaluerende notitie over de spuitomruil in het kader van de AIDS-preventie onder Rotterdamse drugverslaafden. Rotterdam: GGD Rotterdam e.o., 1992.

- Hoek JAR van den, Haastrecht HJA, Coutinho RA: Risk reduction among intravenous drug users in Amsterdam under the influence of AIDS. Am J Public Health 1989; 79: 1355- 1357.

- Limbeek J van, Wouters L, Hekker AC, Cramer A: Een pilot-studie naar het voorkomen van personen met HIV-antistoffen in hulpverleningsprogramma's voor drugsverslaafden buiten de Randstad. Bilthoven: FZA, 1987.

- Haan HA de, Hoek JAR van den, Haastrecht HJA van, Meer CW van der, Coutinho RA: Relatief lage HIV-prevalentie onder druggebruikers in Den Haag ondanks riskant spuitgedrag. Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde 1991; 135: 218-221.

- Toet J: Het RODIS nader bekeken: Cocaïnegebruikers, Marokkanen en nieuwkomers in de Rotterdamse drugshulpverlening. Rotterdam: GGD-Rotterdam e.o., Afdeling Epidemiologie, 1990.

- Kaplan CD, Vries M de, Grund J-PC, Adriaans NFP: Protective Factors: Dutch intervention, health determinants and the reorganization of addict life. In: Ghodse H, Kaplan CD, Mann RD. (eds.): Drug misuse and dependence. London: Parthenon, 1990: 165-176.

- Faupel CE: Drug availability, life structure and situational ethics of heroin addicts. Urban Life 1987; 15(3,4): 395-419.

- Feldman HW, Biernacki P: The ethnography of needle sharing among intravenous drug users and implications for public policies and intervention strategies. In: Battjes RJ, Pickins RW (eds.): Needle sharing among intravenous drug abusers: National and international perspectives. Rockville: NIDA, 1988: 28-39.

- Preble E, Casey JJ: Taking care of business - the heroin user's life on the street. Int J Addict 1969; 1: 1-24.

- Des Jarlais DC, Friedman SR, Strug D: AIDS and needle sharing within the IV-drug use subculture. In: Feldman DA, Johnson TM (eds.): The social dimensions of AIDS. New York: Praeger Publishers, 1986: 111-125.

- Engelsman EL: Drug misuse and the Dutch: A matter of social wellbeing and not primarily a problem for the police and the courts. BMJ 1991; 302: 484-485.

- Bilsen H van: Moraliseren of normaliseren. Tijdschrift voor Alcohol, Drugs en andere Psychotrope Stoffen 1986; 12(5): 182-189.

- Hartsock P: Trip report Europe. Rockville: NIDA, 1987.

- Mata AG, Jorquez JS: Mexican-American intravenous drug users' needle-sharing practices: Implications for AIDS prevention In: Battjes RJ, Pickins RW (eds.): Needle sharing among intravenous drug abusers: National and international perspectives. Rockville: NIDA, 1988: 40-58.

- Des Jarlais DC, Friedman SR, Sotheran JL, Stoneburger R: The sharing of drug injection equipment and the AIDS epidemic in New York City: The first decade. In: Battjes RJ, Pickins RW (eds.): Needle sharing among intravenous drug abusers: National and international perspectives. Rockville: NIDA, 1988: 160-75.

- Epen JH van: Drugverslaving en alcoholisme: Diagnostiek en behandeling. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 1983.

- Despres T: The survivor: An anatomy of life in the death camps. New York: Pocket books, 1976.

- Agar M.: Ripping and running. New York: Seminar Press, 1973.

- Durkheim E: The elementary forms of the religious life. London: George Allen & Unwin LTD, 1971.

- Wolk J, Wodak A, Morlet A, et al.: Syringe HIV seroprevalence and behavioral and demographic characteristics of intravenous drug users in Sidney, Australia, 1897. AIDS 1988; 2: 373-377.

- Chitwood DD, McCoy CB, Inciardy JA et al.: HIV seropositivity of Needles from Shooting Galleries in South Florida. Am J Public Health 1990; 80: 150-152.

- Esteban JI, Shih JWK, Tai C-C et al.: Importance of Western blot analysis in predicting infectivity of anti-HTLV-III/LAV positive blood. Lancet 1985; 2: 1083-1086.

- Lai, P.K., Takayama, H., Tamura, Y., Nonoyama, M. (1990) Activation of human immunodeficiency virus in human myeloid cells by cocaine. presented at the VI International Conference on AIDS, San Francisco, USA. [abstract no. S.A.226]

- Samuels JF, Vlahov JC, Solomon L, Celentano DD: The practice of 'frontloading' among intravenous drug users: association with HIV-antibody. AIDS 1991; 5(3): 343.

- Jose B, Friedman SR, Neaigus A, Curtis R, Des Jarlais DC: 'Frontloading' is associated with HIV infection among drug injectors in New York City. Presented at the VIII International Conference on AIDS, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 19-24 July 1992. [Abstract Th.C.1551]

- Huson D, Neeteson K: Enquete AIDS-preventie HKPD Vlissingen. Vlissingen: HKPD, 1989.

- Valk P van der, Jong W de: Verslaafd in Polen. Intermediair 1988, 24(17): 59-63.

- Stern LS: Personal communication, 1990.

- Chitwood DD, McCoy CB, Comerford M: Risk behavior of intravenous cocaine users: Implications for intervention. In: Leukefeld CG, Battjes RJ, Amsel Z (eds.): AIDS and intravenous drug use: Future directions for community based prevention research. NIDA research monograph 93. Rockville MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse, 1990: 120- 133.

- Bolderhey A: Personal communication 1990.

- Weisswange A: Personal communication, 1990.

- Froner G: Digging for diamonds: A lexicon of street slang for drugs and sex. San Francisco: Health outreach team productions, 1989.

- Koester S, Booth R, Wiebel W: The risk of HIV transmission from sharing water,drug- mixing containers and cotton filters among intravenous drug users. International Journal on Drug Policy 1990; 1(6): 28-30.

- Efthimiou A: Personal communication, 1990.

- Kaplan CD, Morival M, Sterk CE: Needle exchange IV drug users and street IV drug users: A comparison of background characteristics, needle and sex practices, and AIDS attitudes. In: Community epidemiology work group proceedings. Rockville: NIDA, june 1986: IV-16-25.

- Hartgers C, Buning EC, Santen GW van, Verster AD, Coutinho RA: Intraveneus druggebruik en het spuitenomruilprogramma in Amsterdam. Tijdschrift Sociale Gezondheidszorg 1988; 66: 207-210.

- Wit G de: Front loading: Levensgevaarlijk. Dr. Use Good 1990; no. 5: 3.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|