|

INTRODUCTION

One of the issues posed by the organizers of the conference on harrn reduction, which generated this collection, was how to reach the 'hidden sector' of drug users — those neither in prison nor registered in treatment centres or other official agencies. Why is it important to study this less visible fraction of the drug-using population? As other contributors have pointed out, many drug users are satisfied with their lives for some time, and indeed, some do 'retire early' before developing serious problems. Clearly, not all drug roads lead to addiction.

We need to know more about the process that leads to different types of outcomes of drug use, not just the most destructive, in order to promote the occurrence of less harmful outcomes. Moreover, risks associated with drug use are not absent from even experimental or recreational use. Risks may be reduced by personal and social controls.

All drug use is subject to some form of social control, including the formal threats of punishment and the informal controls transmitted through peers and other social groups. Users who are less visible to enforcement agents and not in treatment are likely to be more influenced by personal and informal controls, including knowledge, beliefs and advice available in their social networks (Maloff et al., 1979). Their perceptions can contribute to the development of a harm minimization approach that is based on the reality of the drug use milieu.

The topic of this chapter is the user's perspective on risk and other health-related factors found in a sample of 100 cocaine users in Toronto, Ontario. This analysis includes three groupings of cocaine users: those who had used powder only, intranasale (N=22); those who had used powder and also smoked crack cocaine (N=52); and those who had snorted, smoked and injected cocaine (N=21).3 Thus their experiences reflect a continuum of risk according to mode of administration, one dimension to be considered in a harm reduction strategy.

SAMPLE AND DESIGN

A sample of adult cocaine users, aged eighteen years or more, was recruited directly from the community by means of advertising and referrals. The field period extended for twelve months and was completed by the end of March 1990. Designed as a prospective study, follow-up interviews will be conducted with respondents after one- and two-year intervals, in order to detect changes in cocaine use patterns and perceptions over time. The results presented here reflect the baseline data from the first wave of interviews.

The sample's demographic profile was as follows. The majority of respondents were male (70 per cent) aged thirty years or less (72 per cent), single (71 per cent), not university educated (74 per cent), employed full time (57 per cent), lived in shared or rented accommodation (62 per cent) and had a personal income of S30,000 or less (62 per cent). This community-based sample shared similar age, sex, education and employment status characteristics with a representative sample of cocaine users'from an Ontario provincial survey (Adlaf and Smart, 1989).

As drug users more generally, most had lifetime experience with a wide range of drugs, licit and illicit. While all but one respondent had ever used cannabis, over 80 per cent had experience with LSD, other hallucinogens, and other stimulants from non-medical sources. In addition, about half of respondents had ever used narcotics other than heroin, barbiturates or tranquillizers from non-medical sources; one-third had used phencyclidine (PCP) and nearly one-quarter had used heroin. Tobacco and alcohol were the first drugs tried, at a mean age of thirteen years. Cannabis was next, at nearly fifteen years on the average, followed by amphetamines, barbiturates, hallucinogens, tranquillizers and narcotics other than heroin, all before a mean age of twenty. In the early twenties, heroin was tried next, then cocaine and finally crack at the average age of tvventy-five. With the exception of alcohol, cannabis, cocaine and crack, use of any of these other drugs in the past year was restricted to a minority of the sample.

As cocaine users, just under half reported the use of cocaine in the past month, and about one-quarter had used crack in the same period. Just over one-third had not used cocaine in the past year. The amounts of cocaine used per occasion were fairly small: 0.84 g in the first year of use, 1.81 g in the period of heaviest use, and, for those who were still using, 0.92 g in the last three months. This sample tapped a broad range of experience with cocaine, not only in its various modes of administration but also in frequency and patterns of use.

RESULT 1: SATISFACTION WITH HEALTH AND WELLBEING

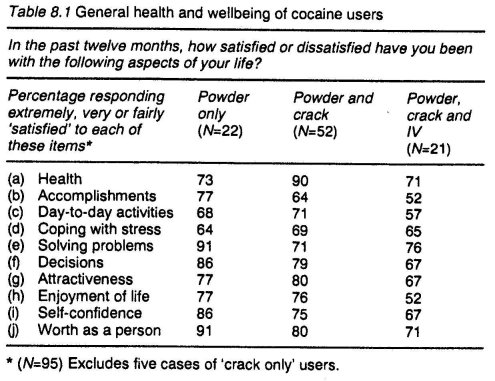

Respondents were asked a series of questions related to physical and mental health and wellbeing and asked to indicate how satisfied they were with these various aspects of their lives. In Table 8.1, their responses are shown, according to their experience with three modes of a'dministration of cocaine: snorting powder cocaine only, intranasal use plus smoking crack, and snorting and smoking crack and intravenous use. Although, in general, respondents in these subgroups expressed quite a high degree of satisfaction on all of these measures, the group with powder, crack and intravenous experience with cocaine showed the lowest scores on all of the items except coping with stress and solving problems. The powder-only group was highest on six of these (accomplishments, solving problems, decisions, enjoyment of life, self-confidence and worth as a person). The powder plus crack group had greater satisfaction than the other groups on four aspects of their lives (health, day-to-day activities, coping with stress, and attractiveness).

The differences between the three groups were, however, small on nearly all of the items and attain no or marginal significance.

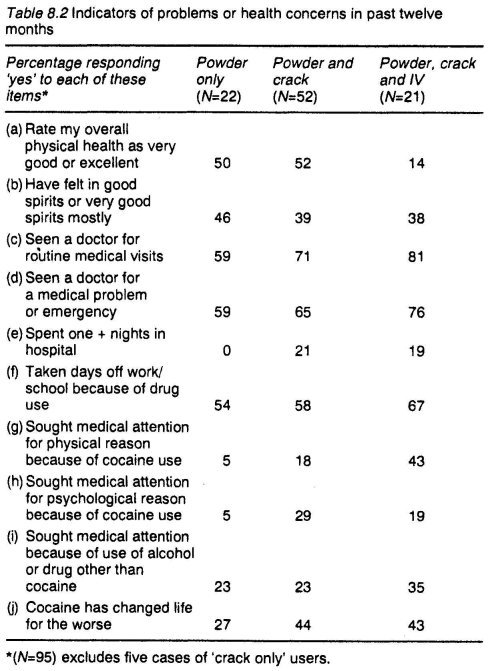

Respondents were also asked more specific questions about any problems or health concerns which they had experienced in the past twelve months. Their responses are shown in Table 8.2, again according to their experiences with three modes of administration of cocaine. Those who had snorted, smoked and injected cocaine indicated the lowest overall rate of physical health (14 per cent as very good or excellent, compared to about one-half of the powder/crack groups). In addition, this multi-mode group reported the most visits to doctors (whether routine or emergency), rnissed the most work or school, and was far more likely to have sought medical attention for the physical effects of cocaine use. In contrast, powder plus crack users wcre most likely to have sought medical attention for psychological reasons related to their cocaine use. Powder-only users were least likely (27 per cent) to say cocaine had changed their lives for the worse, whereas nearly half of the other two groups said that it had.

RESULT 2: CONTROLS ON USE

Four types of controls which may discourage or limit the use of cocaine will be described: availability, legal deterrence, risk perception. and informal guidelines operating in user networks. The first two can be disposed of quickly, since they had little impact. Availability' was perceived to be high, as over 90 per cent of the respondents generally found cocaine easy to obtain. Deterrence, or the perceived risk of punishment, was tow, in that over 90 per cent thought it was unlikely or very unlikely that they would be caught for a cocaine offence in the next year. Actually, 7 per cent reported a prior arrest for cocaine,*and many more had friends who had been arrested, but still regarded the risk of arrest as remote.

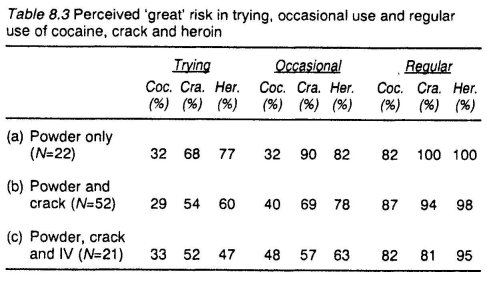

Perception of health risks has been shown to be one of the key factors explaining persistent and different patterns of drug use. In this study, respondents were asked the extent to which people risked themselves by trying, occasional use and regular use of cocaine, crack and heroin. The data reproduced in Table 8.3 show that the percentage in each of the three subgroups of cocaine users (according to experience with different modes of administration) perceive a GREAT risk in different use levels of cocaine, crack and heroin.

For trying each of these substances, it is evident that the three subgroups in our sample are very similar in their perception of a fairly low risk for cocaine, as less than one-third saw the risk as great. In contrast, about twice the proportion viewed the risk of trying crack or heroin as great. Powder-only users saw a higher risk for these latter forms of drug use than did those whose experience with cocaine extended to crack and intravenous use.

Occasional use of crack and heroin is viewed as much more risky than occasional use of cocaine by powder-only users. The contrast is not nearly as great for those who have used powder plus crack, and even less so for those who have experienced all three modes. Both of the more intensive cocaine-using subgroups viewed occasional use of heroin as more risky than occasional use of crack, while the opposite was in` dicated by powder-only users.

A very high proportion of all cocaine user subgroups, 80 per cent or more, see a GREAT risk in regular use of all three substances. Again, heroin on a regular baris is viewed as even more risky than crack, particularly by the group with intravenous experience with cocaine.

Since not all members of this sample had tried crack or injected cocaine, despite ready availability and litde fear of arrest, it was instructive to ask them: Why not? Those who had never smoked crack said either that they were not interested, and were satisfied with the intranasal effects, or were concerned that crack was too addictive. Those who had never injected cocaine offered a variety of reasons, including a fear of needles, of AIDS, of overdosing, and simply that injecting was too dangerous.

Respondents were asked if they had ever encouraged someone to try, or discouraged someone from trying, cocaine. More reported that they had taken a negative rather than a positive stance towards cocaine with friends or acquaintances. About two-thirds said they had actively discouraged someone from trying cocaine. Other than not trying it, respondents offered this advice to novices: limit the amount you take, only snort it, and do it with friends.

The advice offered to daily cocaine users, in order of frequency, was: get help, quit, use less, talk to them; however, one-quarter of respondents said they had no advice to offer to daily users, principally because advice would make no difference or be disregarded. When asked how they kept their own cocaine use in control, a wide range of responses was elicited. A majority expressed some concern about addiction as a possible result of their use, while a minority said they did not try to control their use because they had no need to. Others said they controlled use by avoiding people and situations where cocaine would be found, by limiting the amount used or the money spent, by abstaining or by exerting self-control.

CONCLUSION

We would make three points in conclusion. First, how can 'harm minimization' be enhanced in a group of experienced drug users? A realistic view is that many, if not most, will probably not become addicted to cocaine or otherwise harm themselves. Informal and personal controls will operate to minimize the risks involved. This.is, of course, dependent to some extent on the accuracy of available knowledge and its dissemination among users. As in earlier studies of cocaine users, these respondents ciisplayed quite high levels of concern regarding the health risks of cocaine and its addictive potential (Erickson and Murray, 1989). For others who have a higher threshold of risk, there might be points of intervention that would support healthier drug use practices. For example, self-perceptions of satisfactory mental and physical health were quite high among all users, yet the more quantitative information on seeking medical assistance (e.g. nights in hospital) indicated a fairly poor health profile in a group of young adults. This suggests that primary health care workers might have the most access to such users and be attuned to potential problems.

Second, what are the implications of drug policies for conducting such research as this on low-visibility drug users? This study has illustrated the difficulties of doing community studies in the midst of a `war on drugs' mentality that has characterized the media and police activities in the Toronto area (Cheung et al., 1991). It is difficult to get early stage and lighter users of illicit drugs to volunteer for research at any time, but especially when the newspapers are full of stories of increased enforcement targeting cocaine and crack. Also, the willingness of those who are interviewed to provide referrals to other users is reduced. Furthermore, we are concerned that the success of the follow-up component of the study will also be compromised by a perception of greater vulnerability to arrest among drug users. The result is that knowledge about the development or avoidance of risky outcomes of cocaine use, and the factors that influence these paths, will be compromised.

Third, and more broacily, it is also imponant to recognize that policies for 'safer' cocaine and crack use should encompass not only users' health, but also must include the minimization of harm to the public at large. Long-range policies, within a harm minimization perspective, ought to involve less stigmatization of the drug users themselves and decreasing criminalization of users. This is not to be equated with legal and widespread availability, as examples of irresponsible and self-destructive behaviour abound for both alcohol and tobacco. R.ather, we need a 'new public health' approach that encourages responsible use of all psychoactive substances. This may mean no use in some settings and for some individuals, and restrained use in other contexts. As the chapters in this collection attest, the first steps in conceptualizing and implementing harm minimization are underway. Research and evaluation are part of the next crucial phases in the shift towards a more comprehensive public health policy for the prevention and control of substance misuse.

NOTES

1 This research was funded by the National Health Research and Development Program, Ottawa, Ontario. Thc research assistance of Tammy Landau and Joan Moreau is gratefully acknowledged.

2 Any views cxprcsscd in this chapter are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Addiction Research Foundation.

3 A fourth subgroup, consisting of five respondents who had only used crack, was excluded from the analysis because of the small number and because there wu no clear-cut rationale for including them in one or other of the larger crack-using subgroups.

REFERENCES

Adlaf, E. M. and Smart, R. G. (1989) 'The Ontario Adult Alcohol and Other Drug Use Survey, 1977-1989, Toronto: Addiction Research Foundation.

Cheung, Y. W., Erickson, P. G. and Landau, T. (1991) 'Experience of crack use: Findings from a community based sample in Toronto', Journal of Drug Issues 20.

Erickson, P. G., and Murray, G. F. (1989) 'The undeterred cocaine user: Intention to quit and its relationship to perceived legal and health threats', Contemporary Drug Problèmes 16 (2): 141-56.

Maloff, D., Becker, H. S., Fomaroff, A. and Rodin, J. (1979) 'Informal social controls and their influence on substance use', Journal of Drug Issues 9 (2): 161-84.

|