Chapter 9 An open front door: the coffee shop phenomenon in the Netherlands

| Manuals - Cannabis Reader |

Drug Abuse

Keywords: cannabis — coffee shops — drugs tourism — enforcement —the Netherlands — regulation

Setting the context

A European monograph on cannabis would not be complete without a chapter on Dutch 'coffee shops'. 'Coffee shop' in the Dutch context is a euphemism for cafés where, since 1976, the sale and consumption of cannabis has been tolerated.

This chapter provides a number of surprising insights on the coffee shop phenomenon, from the leading Dutch authority on the subject. The Netherlands has relatively low prevalence of cannabis use (see Monshouwer et al., this monograph), despite the proximity of retail outlets. The 737 coffee shops (2004) are also found in a small number of towns, and their numbers have dwindled as municipalities have sought to tighten their licensing. The chapter also describes a number of features of coffee shops: the AHOJ-G operating restrictions, under which coffee shops operate; the challenges in enforcement of ensuring a limited supply of 500g on the premises (1); the 'back door problem' and controlling links with wider trafficking and crime. Indeed, beyond such retail outlets, the Netherlands is a wholesale hub in the trafficking of Moroccan cannabis resin across northern Europe (see GameIla, this monograph).

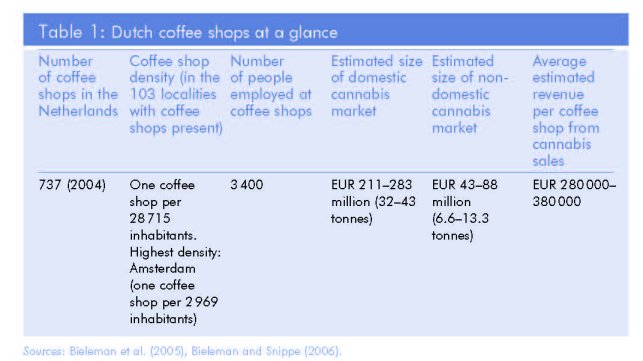

Coffee shops are controversial, both within the Netherlands and in the international context. This chapter remains focused on the domestic situation in the Netherlands: coffee shops and their impact on Dutch drug use patterns. However, coffee shops also play an interesting role in cross-border supply: annual sales volumes to non-Dutch buyers are estimated at 6.6 to 13.3 tonnes (Bieleman and Snippe, 2006). Cross-border drugs tourism has led to considerable and repeated criticism of the Dutch coffee shop policy, particularly among neighbouring countries. A counter argument of note is that cannabis prevalence among young people in the Netherlands is lower than many of its neighbouring countries, and that most cannabis consumed in these countries will not have been purchased at Dutch coffee shops (Table 1).

Perhaps most significantly, Dutch coffee shops play a symbolic role as a paradigm of liberal cannabis policies. In addition to their common appearance in academic studies of drug policy, they have become associated in popular culture with the liberal attitudes of the Netherlands. The coffee shops themselves do little to prevent such notoriety, and play a role in cannabis advocacy and the seed distribution businesses operating from the Netherlands. So, although in the Netherlands discussions in recent years have focused on the inevitability of supply — i.e. underground dealers will supply the demand which is currently served by coffee shops (2) — Dutch drug policy is likely to remain a controversial subject.

Further reading

Bieleman, B., Snippe, J. (2006), 'Coffeeshops en criminaliteit', in Coffeeshops en cannabis, Justitiële verkenningen 2006/01, WODC, Intraval, Groningen, 46-60.

Bieleman, B., Goeree, P., Naayer, H. (2005), Aantallen coffeeshops en gemeenteliik beleid 1999-2004: Coffeeshops in Nederland 2004, Ministerie van Justitie, Intraval-WODC, Groningen.

Korf, D., Wouters, M., Nabben, T., Ginkel, P. van (2005), Cannabis zonder coffeeshop: niet-gedoogde cannabisverkoop in tien Nederlandse gemeenten, Criminologisch Instituut Bonger, Universiteit van Amsterdam.

Mensinga, T. (2006)1 'Dubbel-blind, gerandomiseerd, placebogecontroleerd, 4-weg gekruist onderzoek naar de farmacokinetiek en effecten van cannabis', RIVM rapport 267002001/20061 RIVM.

Ministerie van Volksgezondheid, Welzijn en Sport (2003), Drug policy in the Netherlands, International Publication Series Health, Welfare and Sport No. 18, The Hague.

Niesink, R., Rigter, S., Hoek, J. (2005), THC-concentraties in wiet, neclerwiet en hasi in Nederlandse coffeeshops (2004-2005), Trimbos lnstituut, Utrecht.

Trimbos Instituut and EMCDDA (2007), Report on the drug situation 20061 Reitox national focal point report to the EMCDDA, Utrecht.

WODC (2006), Justitiële verkenningen 2006/01, Coffeeshops en cannabis, WODC, Intraval, Groningen.

An open front door: the coffee shop phenomenon in the Netherlands

Dirk Korf

Introduction

Although cannabis is still an illicit drug in the Netherlands, herbal cannabis and cannabis resin are openly sold in so-called 'coffee shops'. In general, coffee shops are café-like places, although some function more as a store where one can buy, but not use cannabis. In this paper we first describe the process of decriminalisation of cannabis and the evolution of coffee shops in the Netherlands. Then we discuss long-term trends in cannabis use in the Netherlands, both among the general population and among students at secondary schools, followed by exploring some problems regarding the causal relationship between coffee shops and trends in cannabis use in the Netherlands. Next, we examine the role of coffee shops relative to other cannabis sellers at retail level. Finally, we discuss recent developments regarding the supply of coffee shops.

From underground market to coffee shops

The Netherlands was one of the first countries where cannabis became the object of statutory regulation. The import and export of cannabis was introduced into the Opium Act in 1928. Possession, manufacture and sale became criminal offences in 1953. Statutory decriminalisation of cannabis took place in 1976. De facto decriminalisation, however, set in somewhat earlier.

With regard to the cannabis retail market in the Netherlands, four phases can be distinguished.

Phase 1

During the first stage, the 1960s and early 1970s, the Dutch cannabis retail market was a predominantly underground market. Cannabis was bought and consumed in a subcultural environment, which became known as a youth counterculture.

Phase 2

The second stage was ushered in when Dutch authorities began to tolerate so-called 'house dealers' in youth centres. Experiments with this approach were formalised through statutory decriminalisation in the revised Opium Act of 1976. This law distinguishes between two types of drugs: on the one hand, hemp products (Schedule Il drugs), and on the other hand, drugs that represent an 'unacceptable' risk (Schedule I drugs, such as heroin and cocaine). The law also differentiates on the basis of the nature of the offence. For example, drug use is not an offence, possession of up to 30 grams of cannabis is a petty offence or misdemeanour, while possession of more than 30 grams is a criminal offence.

Official national Guidelines for Investigation and Prosecution came into force in 1979. These guidelines are founded on the expediency principle, a discretionary principle in Dutch penal law which allows authorities to refrain from prosecution without first asking permission of the courts. Basically, the expediency principle can be applied in two ways. The first favours prosecution: prosecution is a default response, but is waived if there are good reasons to do so ('prosecution, unless ...'). This case-directed approach was common in the Netherlands until the end of the 1960s.

The second approach applies the expediency principle differently: prosecution takes place only if it is expedient and serves the public interest ('no prosection, unless ...'). Society-wide prosecution of cannabis offences was believed not to serve the public interest: it would stigmatise many young people and socially isolate them from society. According to the 1979 national guidelines, the retail sale of cannabis to consumers would be tolerated, provided the house dealer met the so-called AHOJ-G criteria. These criteria are:

• no overt advertising (affichering);

• no hard drugs;

• no nuisance (overlast);

• no underage clientele (iongeren); and

• no large quantities (grote hoeveelheden).

Small-scale dealing of cannabis thus remained an offence from a legal viewpoint, but under certain conditions would not be prosecuted. It should be acknowledged that this legal tolerance was initiated before the Opium Act was revised in 1976, and became more visible after 1979 with the entry into force of the national guidelines and AHOJ-G criteria. So by the end of the 1970s, the house dealer had become a formidable competitor to the street dealer.

Phase 3

In the third stage, cannabis resin and herbal cannabis were sold predominantly in café-like places, which have become known as 'coffee shops'. Although the government never intended this development, through case law it was decided that coffee shops were to be tolerated according to the same criteria as house dealers. During the 1980s coffee shops captured an increasingly large share of the Dutch retail cannabis market (Jansen, 1991).

Phase 4

The fourth stage began in the mid-1990s, when legislative onus was placed on curbing the number of coffee shops. Since then, the number of coffee shops has steeply declined from about 1 500 to 813 in 2000 and further to 737 in 2004 (Bieleman and Goeree, 2000; Bieleman et al., 2005). Moreover, in 1 996 local communities received the opportunity to decide whether or not they would allow coffee shops in their municipality. To date, 77% of the 483 communities have decided not to allow coffee shops at all. Consequently, they can close down coffee shops even if they do not violate the AHOJ-G criteria. In addition, the minimum age for visitors was increased from 16 to 18 years.

So, coffee shops are not distributed evenly over the country. Over half (52%) of all coffee shops are located in the five largest communities (> 200 000 inhabitants), while only 1% can be found in communities with less than 20 000 inhabitants. Although only 5% of the national population lives in Amsterdam, the city is the home of one-third of all coffee shops in the country.

Trends in cannabis use

From an analysis of available data on the prevalence of cannabis use between the late 1960s and the late 1990s, we concluded that there was little room to doubt that cannabis use in the Netherlands spread rapidly around 1970 (Korf et al., 2002). Most probably, cannabis use among youths in the Netherlands evolved in two waves, with a first peak around 1970, a low during the late 1970s and early 1980s, and a second peak in the mid- to late-1990s.

Prior to the Second World War, cannabis use in the Netherlands had hardly been heard of, and this did not change much in subsequent years. The 1950s witnessed the introduction of cannabis in the Netherlands, when herbal cannabis was used by small groups of jazz musicians and other artists who had learned to use it while abroad, as well as foreign seamen and Germany-based US military personnel, in particular in Amsterdam (Cohen, 1975; de Kort and Korf, 1992).

In the course of the 1960s, cannabis use in the Netherlands rapidly gained popularity. An increasing number of adolescents began smoking it, but not until the end of the decade did a cannabis smokers' subculture emerge. Cannabis spread significantly in the wake of the hippie movement, and smoking cannabis at the national monument in Dam Square or in the Vondelpark in Amsterdam became a staple of a burgeoning international youth sub-culture (Leuw, 1973).

The first indication of the rapid growth in the popularity of cannabis towards the end of the 1960s can be found in school surveys. In 1969 as many as 9% of the students

in the final form at secondary school reported having used cannabis at least once. Two years later this percentage had doubled to 18%. Yet rates did not continue to rise in subsequent years. In 1973, lifetime prevalence was again put at 18% (see Korf, 1995). It was more than a decade before the next national school survey was carried out, in 1984. This survey yielded a much lower lifetime prevalence of cannabis use (5%). To a considerable degree, however, the lower rate can be explained by inconsistencies in the samples. If comparable age groups are examined, the difference between 1973 and 1984 rates is much smaller: 18% ever use of cannabis for students with a mean age of 17.5 years in 1973; 12% for students 17 years and older in 1984 (Plomp et al., 1990).

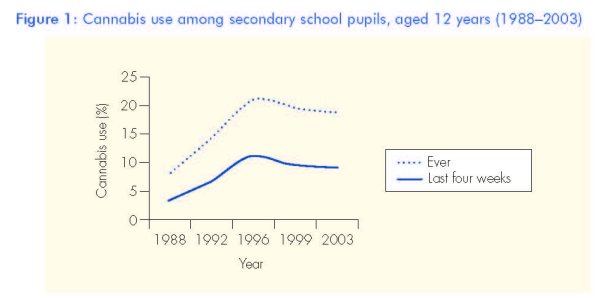

Unfortunately, these school surveys did not address nationally representative samples. Since 1988 nationally representative surveys have been conducted on the extent to which secondary school students aged 12 and older have experience with alcohol, tobacco, drugs and gambling. From 1988 to 1996, cannabis rates among students rose, but stabilised in the late 1990s, followed by a drop (Monshouwer et al., 2004). (Figure 1).

General population surveys are another indicator of trends in cannabis use. Between 1970 and 1991 six national household surveys have been conducted in the Netherlands (see Korf, 1995). They reveal a growing percentage of people that report having used cannabis at least once in their lives: from 2-3% in 1970, to 6-10% during the 1980s and to 12% in 1991. In 1997, a new series of general population studies was initiated, using large representative samples of people aged 12 years and over. In addition to figures on lifetime use of — amongst others — cannabis, this National Prevalence Study also includes data on current use (Abraham et al., 1999). According to the 1 997 data, the vast majority have never tried cannabis and only one in six respondents have ever used cannabis (15.6%). One in 40 respondents (2.5%) used cannabis in the month prior to the interview (current use). The second National Prevalence Study, conducted in 2001, revealed a lifetime prevalence rate of 17% and 3% for last month use (Abraham et al., 2002). A different age group (15-64 years) was studied in the third National Prevalence Study (2005/2006). Between 1997 and 2005-2006, trend analysis showed: a decrease in last year prevalence in the age group 15-24 years; an increase in lifetime, last year and last month prevalence among the age group 25-44 years; and an increase in last month prevalence in the age group 45-64 years (Rodenburg et al., 2007).

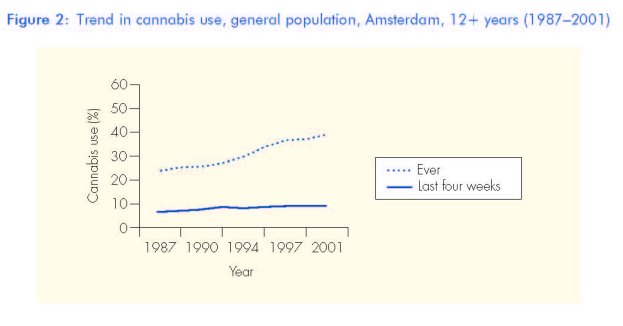

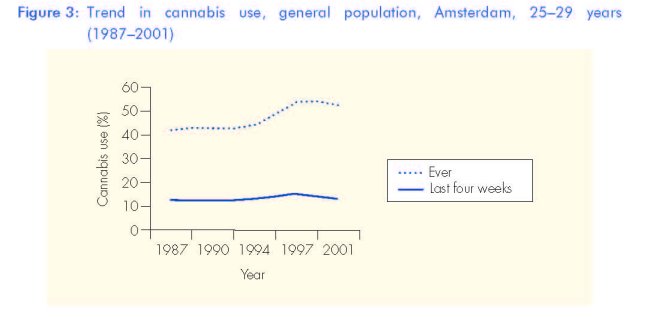

Cannabis use is not distributed evenly across the Netherlands. Cannabis use is more prevalent in urban than in rural areas. Amsterdam tops the list with respect to ever use and current use. Such an uneven geographical spread of cannabis use is not only typical for the Netherlands, but can also be found in other countries (Partanen and Metso, 1999). Since 1987, five surveys have been conducted among the general population of Amsterdam aged 12 years and over, applying a similar methodology as in the National Prevalence Study. Prevalence rates increased (Abraham et al., 2003). To a large extent, this increase reflects a generation effect. This generation effect also helps to explain why rates for ever use increase much more strongly than those for current use (Figure 2). The majority of the adult ever users in Amsterdam have stopped using cannabis. While many young ever users are currently taking cannabis, few older ones continue to do so. The mean age of cannabis use in Amsterdam remained stable at around 20 years. For the age cohort of 25-29 years, lifetime use first increased in the 1990s and then stabilised, while current use remained quite stable during the period (Figure 3).

Decriminalisation and cannabis use

During the transition from the first to the second phase in Dutch cannabis policy, the many underground selling points became consolidated into a more limited number of formalised sales outlets that were publicly accessible yet shielded from public view.

During the third phase, availability increased markedly in numerous coffee shops. More recently, availability may have decreased because of the declining number of coffee shops. It is striking that the trend in cannabis use among youth in the Netherlands parallels our four stages in the availability of cannabis. The number of adolescent cannabis users peaked when cannabis was distributed through an underground market during the late 1960s and early 1970s, when the drug was available through many small-scale retailers (street dealers, in homes and bars). Adolescent use then decreased as house dealers superseded the underground market during the 1970s. It increased again in the 1980s after coffee shops took over the sale of cannabis. And it stabilised or slightly decreased at the end of the 1990s, when the number of coffee shops was reduced.

Rising or falling cannabis consumption need not be the unequivocal result of decriminalisation or criminalisation. In order to study the possible link between decriminalisation and the evolution of Dutch cannabis use, first we need to analyse the prevailing rates of cannabis use both before and after decriminalisation. Moreover, longitudinal trends in cannabis use in the Netherlands can only properly be ascribed to decriminalisation when it is made plausible that they are causally related.

In line with MacCoun and Reuter (1997), reasoning by analogy might be helpful in getting closer to an understanding of the nature of the link between decriminalisation and cannabis prevalence rates in the Netherlands. How do the Dutch trends in the cannabis case compare to those in other Western nations? Such a question is not easy to answer, mainly because there are few countries where cannabis consumption has been consistently and systematically recorded over the years.

The USA has a relatively long tradition of surveys on drug use and the American figures consistently appear to be higher than those in the Netherlands (Plomp et al., 1990; NDM, 2006). Clearly the USA, as the prototype of a prohibitionist approach towards cannabis, reports higher cannabis consumption than the Netherlands, the prototype of anti-prohibitionism. Marijuana use among youth in the USA also evolved in waves, with a peak during the late 1970s, a decline in the 1980s, a rise in the 1990s and then stabilisation. Harrison (1997) concludes that such a wave-like development can be understood as a verification of Musto's more general model on trends in drug use (Musto, 1987). In addition, structural factors such as the post-Second World War baby boom and drug education (affecting health risk perception) might help to explain the development in marijuana use in the USA (Harrison, 1997). Other European countries have also reported a wave-like trend in cannabis use (Kraus, 1997). For example, cannabis use spread rapidly in (West) Germany toward the end of the 1960s, followed by stabilisation and decline in the early 1970s and then an increase in the 1980s (Reuband, 1992; Kraus, 1997). The rising use of cannabis in Germany continued in the 1990s (Kraus and Bauernfeind, 1998; Kraus et al., 1998).

Cannabis use in some other countries with a prohibitionist approach towards cannabis — Sweden in particular — is substantially lower than in the Netherlands. Although this has been used as supporting evidence that prohibition deters use, the argument does not hold when seen in relation to data from other prohibitionist countries, for example, the USA, and elsewhere in Europe. From the available data from general population surveys in 10 Member States of the EU (which are not absolutely comparable), the EMCDDA concluded that the level of cannabis use varies strongly within the EU (EMCDDA, Annual Report 2001); from 9.7% in Finland to 25% in the UK (England and Wales). The Netherlands is placed somewhere in the middle (and this would most probably be lower if its level of urbanisation were taken into account). From a comparison of data from general population surveys in Germany (Kraus et al., 1998) and the UK (Ramsay and Partridge, 1999)1 we concluded that adolescents and young adults in these countries have showed a similar trend to that in the Netherlands: increasing cannabis use from the late 1980s onwards (Korf et al., 2002).

So, trends in cannabis use in the Netherlands appeared to run along similar lines to those in other European countries, and Dutch figures on cannabis use between the late 1960s and the late 1990s were not out of line with those from countries that did not decriminalise cannabis. Over time, prevalence of cannabis use shows a wave-like trend in many countries, including the Netherlands. This supports Reuband's earlier conclusion that cannabis use trends evolve relatively independently from drug policy, and that countries with a 'liberal' cannabis policy do not have higher or lower rates than countries with a more repressive policy (Reuband, 1995).

From the data discussed so far, it appears unlikely that decriminalisation of cannabis causes an increase in cannabis use. However, before we draw such a final conclusion, we need to address three issues. First, we have compared Dutch prevalence data with those from countries that did not officially decriminalise cannabis. However, the actual enforcement of cannabis offences may be less strict than the law suggests. Second, at the level of the 'dependent variable', the question is 'what is the most appropriate indicator for cannabis use?' Third, we must take into account the accessibility of coffee shops: as mentioned, there is a minimum age for visiting coffee shops.

How do drug laws relate to the actual enforcement of cannabis offences? The Netherlands has separate schedules for cannabis and other illicit drugs. The use of cannabis is not illegal, and penalties for trafficking are higher than for possession. In this respect, the Dutch drug law is not unique. There are other EU countries with differential drug laws (two or more schedules), where cannabis use is not illegal, and where the drug law sets higher penalties for trafficking than possession (see Ballotta et al., this monograph; Korf, 1995; Leroy, 1992). Most EU countries have penalties for cannabis possession, ranging from a fine to incarceration (EMCDDA ELDD, 2001). According to Kilmer (2002), in practice most arrests for cannabis possession in EU Member States appear to only lead to a fine, while few data are available on the levels of these fines and about what happens when they are not paid. So Kilmer examined actual cannabis law activities within a number of Western countries, by comparing police capacity, enforcement of and punishment for cannabis possession laws. He concluded that the probability of cannabis users being arrested for cannabis possession is generally between 2 and 3%. Probability of arrest was fairly similar (2-3%) in EU countries with relatively low cannabis prevalence rates (e.g. Sweden: arrest rate, 2.4% in 1997) and those with higher rates (e.g. United Kingdom: arrest rate, 2.1% in 1996 and 2.9% in 1998). Consequently, formal criminalisation of cannabis possession rarely leads to actual criminalisation in practice. So it appears plausible that current cannabis laws in EU Member States, as well as other Western countries, have little deterrent effect on cannabis use.

It is not uncommon to discuss the effects of decriminalisation of cannabis in the Netherlands on the basis of data from school surveys. The analysis by MacCoun and Reuter (1997) was largely based on data from school surveys, and we included such figures in our analysis earlier in this chapter as well. Unfortunately, this is not without problems. In 1996 the minimum age for coffee shop visitors was raised from 16 to 18 years. Consequently, minors are not allowed to buy and use cannabis in coffee shops, which means that prevalence rates of cannabis use among youth below the age of 18 cannot be defined as valid indicators in the analysis of the effects of decriminalisation.

In a secondary analysis of national school survey data from 1992, 1 996 and 1 999 we looked at how the use of cannabis evolved amongst adolescents (Korf et al., 2001). We faced two difficulties. First, school populations are constantly changing, partly due to an ongoing rise in percentages of ethnic minority students. Second, samples do not always precisely reflect school populations. Statistical bias can be corrected to an extent by weighting, but that still does not ensure full representativeness. Both the real changes in the student population and the sampling errors could potentially damage the reliability of the cannabis use statistics. We allowed for this as much as possible by performing logistic regression analysis. This enabled us to detect any changes in the use of cannabis that were not due to differential background characteristics (gender, ethnicity, school type and urbanisation) in the samples. Analysis revealed a break in the previous upward trend in current cannabis use among 16-17-year-olds after the raising of the age limit for coffee shops in 1996. Cannabis use stabilised between 1996 and 1999. In addition, the analysis indicated a shift in supply from coffee shops to other sources. Current 16-17-year-old cannabis users among the students in 1999 bought their cannabis less often in coffee shops (25.7%) than those from 1996 (45.2%). Logistic regression led to the same conclusion: the 1999 students showed a greater likelihood of buying cannabis outside coffee shops (an odds ratio of 0.76).

These figures are a strong indication that the higher age limit at coffee shops has indeed resulted in a reduction of cannabis sales to adolescents in coffee shops, in favour of more informal supply through friends (from 47.6% in 1996 to 66.5% in 1999). These figures are somewhat problematic as what has been reported as buying in a coffee shop could also mean that the respondents had someone else buy the drug there. Nevertheless, the data strongly suggest that raising the minimum age for coffee shops had an effect on buying behaviour. According to the 2003 national school survey, most current cannabis users among students aged 18 years buy their cannabis also or exclusively in coffee shops, substantially more often than younger users (Monshouwer et al., 2004). It is tempting to interpret the nationwide stabilisation in adolescent cannabis use as a result of raising the age limit. Adolescents are now more likely to obtain cannabis from friends and acquaintances instead of from coffee shops. Thus, at the user level we see an apparent displacement of the cannabis market (Korf et al., 2001).

In conclusion, trends in the lifetime prevalence of cannabis use in the Netherlands developed in parallel to changes in cannabis policy. Alongside the rapid growth in the number of coffee shops, we observed a significant increase in prevalence rates. However, this does not automatically support the conclusion that decriminalisation has led to an increase in cannabis consumption. First of all, lifetime prevalence is often not an adequate indicator since it largely reflects a 'generation effect'. Current (last month) use seems to be a better indicator, although from the perspective of harm reduction it might be argued that 'problem use' is an even better one. Unfortunately, there is no standardised indicator for problematic cannabis use.

Reasoning by analogy through cross-national comparison partly leads to conclusions other than MacCoun and Reuter's (1997). In particular, their conclusion that commercial access — through coffee shops — is associated with growth in cannabis use has to be questioned. Their study largely focused on data from the USA and Nordic countries (Denmark and Norway). Within a Western European context, prevalence rates in the Nordic countries are generally rather low, with the exception of Denmark, which combines relatively high lifetime figures with low current use. Comparison with other EU countries shows striking similarities with Dutch figures on current cannabis use. In addition, neighbour countries, as well as the USA, report similar trends in current cannabis use over time. Cannabis use in neighbour countries also shows a wave-like development, so it seems implausible that the trends in cannabis use in the Netherlands were causally related to Dutch cannabis policy. It seems more likely that the parallel development of cannabis use with stages in the decriminalisation process in the Netherlands was accidental, and that trends in cannabis use were predominantly affected by other factors that were not unique to the Netherlands.

Most probably, these factors relate to general youth trends that make cannabis more or less fashionable and acceptable. We were able to include more recent figures on cannabis than MacCoun and Reuter, and these data show that cannabis use stabilised among Dutch youth in the late 1990s. At first glance, this seems to be a result of raising the minimum age for access to coffee shops from 16 to 18 years. However, informal networks of friends appear to have quickly taken over the role of coffee shops as retail suppliers of cannabis. Most probably, the role of such informal networks is similar to those in other European countries. This leads to the conclusion that regulating the cannabis market through law enforcement has only a marginal, if any, effect on the level of cannabis consumption.

The restricted role of coffee shops

As has been mentioned, most communities in the Netherlands do not have coffee shops at all, in particular smaller towns and villages. In 2003-2004 we conducted a study on the 'non-tolerated' sale of cannabis in the Netherlands (Korf et al., 2004). By non-tolerated cannabis dealers, we meant the ones outside the officially tolerated coffee shops. The study focused on the retail trade and not on the coffee shop suppliers (the back door) or the middle and higher levels of the cannabis market.

The study was conducted in 10 municipalities with more than 40 000 inhabitants, that were geographically spread throughout the country and different as regards their size and coffee shop density (number of coffee shops per 10 000 residents). Eight of the municipalities had one or more coffee shops and the other two did not have any official coffee shop at all. Local experts were interviewed in all 10 communities, a survey was made among approximately 800 current cannabis users (not recruited in coffee shops) in seven communities and an ethnographic field study was conducted in five communities.

In all the municipalities we studied, there was a non-tolerated cannabis market at the retail level. We distinguished two main categories: fixed and mobile sale points. The fixed non-tolerated sales points can be divided into home dealers and under-the-counter dealers primarily at clubs or pubs. The mobile non-tolerated sales points can be divided into home delivery after cannabis is ordered by telephone (mobile phone dealers) and street sales in the street and at spots where people hang out (street dealers). In addition, there are home growers, who can be either fixed or mobile dealers.

We found that, whether or not municipalities have coffee shops, the non-tolerated sale of cannabis is widespread. At the retail level, the non-tolerated cannabis market was very similar in all the municipalities in the study, and the same sales patterns were found in virtually all municipalities. In the municipalities with officially tolerated coffee shops, an estimate of approximately 70% of the local cannabis sales went directly through the coffee shops. The higher the coffee shop density, the greater their percentage of the local sales. In municipalities with no coffee shops or a low coffee shop density, users most frequently bought cannabis somewhere else, as well as in a coffee shop.

There are various reasons why non-tolerated cannabis dealers also operate in municipalities with coffee shops. The major reasons are the geographic distribution of the coffee shops, their opening hours and the minimum age they adhere to. In particular, it is the mobile phone dealers and home dealers who take advantage of the geographic gaps in the cannabis market and are mainly active in districts where coffee shops are rare or non-existent. Additionally, coffee shops are not open 24 hours a day and the non-tolerated dealers explicitly take advantage of this by being easy to reach customers at times when the coffee shops are closed. For minors, the minimum age at coffee shops is an important reason to have cannabis resin or herbal cannabis delivered, or to buy it on the street or from a home dealer. In addition, non-tolerated dealers can serve as an attractive alternative for coffee shops because users can buy larger quantities of cannabis, and sometimes the cannabis is sold more cheaply.

The 'back door' of coffee shops: diverging policy options

Originally, most cannabis used in the Netherlands was cannabis resin, and until the mid-1980s most cannabis was imported. Due to strong improvement in cultivation techniques, domestically grown herbal cannabis became more and more popular. In the early 1990s approximately 50% of the cannabis used in the Netherlands was domestically grown (Boekhoorn et al., 1995). In the second half of the 1990s, the popularity of domestically cultivated herbal cannabis further increased. According to a study among experienced cannabis users by Cohen and Sas (1998), about half preferred herbal cannabis, mostly 'nederwiet', one-quarter preferred cannabis resin and another quarter had no preference. In 2001, from a survey among coffee shop visitors in Amsterdam, it was concluded that two-thirds preferred herbal cannabis to cannabis resin (Korf et al., 2002).

Today, herbal cannabis is the product sold most often in coffee shops. Mostly this is so-called 'nederwiet', or home-grown herbal cannabis. In practice, this kind of herbal cannabis is grown indoors and only a small proportion is imported herb grown outdoors. Most cannabis resin is imported, predominantly from Morocco (see GameIla, this monograph) and only a very small proportion of the resin sold in coffee shops stems from indoor cultivation in the Netherlands.

The THC content of cannabis as sold in coffee shops in the Netherlands has been systematically monitored by the Trimbos Institute since 1999. It might be debated to what extent these figures are correct as there is dispute among researchers over what is the most appropriate method to measure THC concentrations (King et al., 2005), and perhaps the Dutch method generates relatively high concentrations. Nevertheless, while consistently applying the same laboratory techniques, the monitoring system is an adequate instrument to analyse trends in purity over time. THC concentrations in sold 'nederwier more than doubled between 1999-2000 and 2003-2004, from an average of 8.6% to 20.4%. In 2004-2005 the average concentration dropped to 17.7%, and 17.5% in 2005-2006, which was comparable to 2002-2003. Imported hashish showed an increase in THC concentration from 11-12% in the first two years to 17-18% in 2002, and then remained stable. THC concentrations in imported herbal cannabis remained quite stable at around 6% (Pijlman et al., 2005; Niesink et al., 2006).

The supply of coffee shops is commonly known in the Netherlands as 'the back door', even though in reality both suppliers and customers use the same door to enter the coffee shop. While the sale of cannabis to consumers is tolerated in coffee shops, the supply remains illegal and is subject to law enforcement. Although a maximum of 500 grams 'in stock' is tolerated, coffee shops can still be prosecuted for sourcing the cannabis into their locality. Moreover, cultivation of five plants or more per person is illegal. Police and the judicial authorities have increased their actions against herbal cannabis growers. Between 2000 and 2003, the number of cases brought to the public prosecutor for cannabis offences increased by more than 40% (from 4 324 to 6156). A growing number of cannabis plantations have been raided and in both 2005 and 2006 approximately 6 000 herbal cannabis cultivation sites were dismantled, and about 2.5 million plants confiscated and destroyed per year (Wouters et al., 2007).

When the Dutch authorities decided to decriminalise cannabis and to tolerate the retail sale of cannabis to consumers, they did not, and probably could not, envision that this would lead to the coffee shop phenomenon. The strong growth of the number of coffee shops — that were never intended to exist — meant that the authorities were confronted with a new problem. In order to cap this growth, the national government decided to give local communities legal instruments to regulate the number of coffee shops, including the option to not allow coffee shops at all. Regarding the supply side of the cannabis market, enforcement has focused on large-scale dealers. Interestingly, herbal cannabis has taken over from the once-dominant resin. While cannabis resin typically was, and still is, imported, herbal cannabis is today mostly domestically cultivated. Consequently, a shift in law enforcement can be perceived from controlling import to controlling cultivation within the country itself (Decorte and Boekhout van Solinge, 2006).

While finalising this paper, two options for regulating the supply of coffee shops have been debated in the Netherlands. On the one hand, at a national level the Ministry of Justice of the previous government was a strong advocate of persistent repression of the illegal cultivation of cannabis in the Netherlands. On the other hand, a growing number of communities with coffee shops, as well as a majority in the Dutch parliament, have pleaded to take a further step towards decriminalisation by regulating the back door problem. From their perspective, the fight against international traffickers should be continued and intensified, while supply for the national market should become less profitable for criminals by allowing the cultivation of herbal cannabis under strict conditions for coffee shops only. Just before Christmas 2005, the Ministry of Justice gave up its resistance and declared to no longer block an experiment with regulated cultivation of herbal cannabis. With the new national government, installed early in 2007, the future of the supply of coffee shops is an open question.

Recent developments

In 2007, the national guideline that coffee shops are not allowed to sell alcohol has finally been implemented in Amsterdam. As a result, most of the approximately 40 coffee shops in Amsterdam that were also serving alcohol, have decided to stop selling cannabis and consequently lost their coffee shop licence.

Also, there is a trend to be more strict on allowing coffee shops in the proximity of schools. The city council of Rotterdam has been the first to decide to close down approximately 27 of a total of 62 coffee shops, mostly in the inner city. It is to be expected that coffee shop owners will continue to protest in the courts against this decision, in particular because the city of Rotterdam has declared that the coffee shops to be closed will neither receive any financial compensation, nor be given a licence for a coffee shop elsewhere in Rotterdam.

As part of the plans of the national government to ban tobacco smoking from restaurants and cafes in 2008, a vivid discussion continues on the question of whether coffee shops should become totally smoke-free, be allowed to have a separate smoking facility, or will be exempt from the general anti-smoking policy.

(1) This problem has become known as 'the back door' problem in the Netherlands. A recent case in the town of Terneuzen highlights the problem. A police check of the coffee shop Checkpoint in June 2007 found over 5kg of cannabis on the premises and over 90kg in a nearby warehouse (www. hvzeela nd.n lin ieuws. ph p? id = 5542).

(2) This was one of the broad conclusions of the Cannabis zonder coffee shop report.

References

Abraham, M., Cohen, P., van Til, R. et al. (1999), Licit and illicit drug use in the Netherlands, 1997, Centre for Drug Research (CEDRO), Amsterdam.

Abraham, M., Kaal, H., Cohen, P. (2002), Licit and illicit drug use in the Netherlands, 2001, CEDRO/ Mets., Amsterdam.

Abraham, M., Kaal, H., Cohen, P. (2003), Licit and illicit drug use in Amsterdam, 1987 to 2001. CEDRO/Mets., Amsterdam.

Bieleman, B., Goeree, P. (2000), Coffeeshops geteld; Aantallen verkooppunten van cannabis in Nederland (Coffee shops counted. The number of cannabis selling coffee shops in the Netherlands), Intraval, Groningen.

Bieleman, B., Goeree, P., Naayer, H. (2005), Aantallen coffeeshops en gemeenteliik beleid

1999-2004: coffeeshops in Nederland 2004, Ministerie van Justitie, Intraval-WODC, Groningen. Boekhoorn, P., van Dijk, A., Loef, C., van Oosten, R., Steinmetz, C. (1995), Softd rugs in nederland,

consumptie en hanciel, Steinmetz, Amsterdam.

Cohen, H. (1975), Drugs, ciruggebruikers en drugsœne, Samson, Alphen aan den Rijn. Cohen, P., Sas, A. (1998), Cannabis use in Amsterdam, Cedro, Amsterdam.

Decorte, T., Boekhout van Solinge, T. (2006), 'Het aanbod van cannabis in Nederland en Belgie [Cannabis supply in the Netherlands and Belgium], Tiidschrift voor Criminologie 2006 (48) 2 (lthemanummer Drugs en drughandel in Nederland en Belgiël), 144-154.

EMCDDA (2001), Annual report on the state of the drugs problem in the European Union, European Monitornig Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, Lisbon.

EMCDDA (2001), ELDD: legal status of cannabis: situation in the EU Member States, European Monitornig Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, Lisbon.

Harrison, L. (1997) 'More cannabis in Europe? Perspectives from the USA', in: Korf, D. and Riper, H. (eds.) Illicit drugs in Europe. Proceedings of the seventh annual conference on drug use and drug policy in Europe, Siswo, Amsterdam.

Jansen, A. (1991), Cannabis in Amsterdam. A geography of hashish and marihuana, Coutinho, Muiderberg.

Kilmer, B. (2002), 'Do cannabis possession laws influence cannabis use?', Paper presented at the

International Scientific Conference on Cannabis, Rodin Foundation, 25 February, Brussels.

King, L., Carpentier, C., Griffiths, P. (2005), 'Cannabis potency in Europe', Addiction 100(7):

884-886.

Korf, D. (1995), Dutch treat. Formal control and illicit drug use in the Netherlands, Thela Thesis, Amsterdam.

153

An open front door: the coffee shop phenomenon in the Netherlands

Korf, D., van der Woude, M., Benschop, A., Nabben, T. (2001), Coffeeshops, jeugd en toerisme, Rozenberg, Amsterdam.

Korf, D., Nabben, T., Benschop, A. (2002)1 Antenne 2001. Trends in alcohol, tabak en drugs bii ionge Amsterdammers, Rozenberg Publishers, Amsterdam.

Korf, D., Wouters, M., Nabben, T., van Ginkel, P. (2004), Cannabis zoncier coffeeshop, Rozen berg, Amsterdam.

de Kort, M., Korf, D. (1992), 'The development of drug trade and drug control in the Netherlands: a historical perspective', Crime, Law and Social Change 17: 123-144.

Kraus, L. (1997), 'Pravalenzschatzungen zum Konsum illega re Drogen in Europa' (Prevalence estimates of illicit drug use in Europe), Sucht 43 (5): 329-341.

Kraus, L., Bauernfeind, R. (1998), 'Reprasentativerhebung zum Gebrauch psychoaktiver Substanzen bei Erwachsenen in Deutschland 1997' (Population survey on the consumption of psychoactive substances in the German adult population 1997), Sucht 44 (Sonderheft 1).

Kraus, L., Bauernfeind, R., Bühringer, G. (1998), Epidemiologie des Drogenkonsums. Ergebnisse aus Bev6Ikerungssurveys 1990 bis 1996 (Epidemiology of drug use. Findings from population surveys 1990-1996), Nomos, Baden-Baden.

Leroy, B. (1992), 'The European Community of twelve and the drug demand. Excerpt of a comparative

study of legislations and judicial practice', Drug and Alcohol Dependence 29: 269-281.

Leuw, E. (1973), 'Druggebruik in het Vondelpark 1972' (Drug use in the Vondelpark 1972),

Nederlands Tiidschrift voor Criminologie 15: 202-218.

MacCoun, R., Reuter, P. (1997), 'Interpreting Dutch cannabis policy: reasoning by analogy in the legalization debate', Science 278: 47-52.

Monshouwer, K., van Dorsslelaer, S., Gorier, A., Verdurmen, J., Vollebergh, W. (2004), Jeugd en riskant gedrag, Trimbos Institute, Utrecht.

Musto, D. F. (1987) The American disease. Origins of narcotic control. Oxford University Press, New York/Oxford.

Nationale Drug Monitor (NDM) (2006), Jaarbericht 2006, Trimbos lnstituut, Utrecht.

Niesink, R., Rigter, S., Hoek, J., Goldschmidt, H. (2006), THC-conœntraties in wiet, nederwiet and

hasi in Nederlandse coffee shops (2005-2006) (THC-concentrations in cannabis preparations sold

in Dutch coffee shops), Trimbos Institute, Utrecht.

Partanen, J., Metso, L. (1999), 'Suomen toinen huumeaalto' (The second Finnish drug wave), Yhteiskuntapolitiikka 2, Helsinki.

Pijlman, F., Rigter, S., Hoek, J., Goldschmidt, H., Niesink, R. (2005), 'Strong increase in total delta-

THC in cannabis preparations sold in Dutch coffee shops', Addiction Biology 10 (2): 171-180.

Plomp, H., Kuipers, H., van Oers, M. (1990), Roken, alcohol- en drugsgebruik onder scholieren vanaf 10 Oar (Smoking, alcohol and drug use among students aged 10 years and older), VU University Press, Amsterdam.

Ramsay, M., Partridge, S. (1999), Drug misuse declared in 1998: results from the British Crime Survey, Home Office, London.

Reuband, K. (1992), Drogenpolitik und Drogenkonsum. Deutschland und die Niederlande im Vergleich (Drug policy and drug use. A comparison of Germany and the Netherlands), Leske and Budrich, Opladen.

Reuband, K. (1995), 'Drug use and drug policy in Western Europe. Epidemiological findings in a comparative perspective', European Addiction Research 1 (1-2): 32-41.

Rodenburg, G., Spi jkerman, R., van den Eijnden, R., van de Mheen, D. (2007), Nationaal prevalentie onderzoek middelengebruik 2005, IVO, Rotterdam.

SAMHSA (2000), Summary of findings from the 1999 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Rockville.

Wouters, M., Korf, D., Kroeske, B. (2007), Harde aanpak, hete zomer. Een oncierzoek naar de ontmanteling van hennepkwekeriien in Nederland, Rozenberg, Amsterdam.

154

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|