Chapter 8 In thinking about cannabis policy, what can be learned from alcohol and tobacco?

| Manuals - Cannabis Reader |

Drug Abuse

Keywords: alcohol – cannabis – economics – environmental strategy – polydrug consumption – prohibition – regulation –taxation –tobacco

Setting the context

Cannabis is just one of many psychoactive substances used in Europe for recreational and therapeutic purposes. Research into the topic has never really ignored this real-life polydrug use. Most joints contain tobacco. A cannabis session often includes the consumption of alcoholic drinks. These are givens. Nonetheless, only recently have professionals working in the area of cannabis control genuinely begun to look at the 'cross-substance' effects of legislation targeted at other, legal, substances such as alcohol and tobacco.

This is not to say that there has been a revolutionary shift towards examining the interrelationships of polydrug consumption. The epidemiological regime — which splits drug taking along neat substance-specific lines (cannabis, ecstasy, cocaine, etc.) — remains in place. Rather, there has been a shift in national drug strategies — at least in Europe — to erode the substance-specific approach which traditionally segregated activity on licit psychoactive substances from activity on illicit drugs ('). Politically, it is

no longer taboo to compare legal and illegal substances. The recent advent of smoking bans in Europe represents a golden opportunity to measure the knock-on effects on consumption of other substances. Moreover, evidence on the effects of decriminalisation of cannabis (that is, lower penalties for personal possession) in many European countries during the early 2000s is now filtering into the policy literature.

This chapter does not retread the well-worn track of comparative drug harm indexes and the relative harms of cannabis and society's chosen licit drugs. Instead, it examines the ways in which the market for licit substances has been subject to government control, together with brief commentary on the merits of these interventions. The 'elephant in the room' has been dutifully ignored. There are no 'what-if' scenarios on how market controls could be transposed to cannabis in a post-legalisation environment. A postscript to this chapter provides a range of sources for further reading on the topic of mooted cannabis regulation. However, for the time being, any such options would require a huge shift in the political balance, which currently appears to be, if anything, more tipped in the favour of increased controls on cannabis rather than liberalisation (see Ballota et al., this monograph).

Further reading on the regulation of alcohol and tobacco

Alcohol

Anderson, P., Baumberg, B. (2006), Alcohol in Europe, Institute of Alcohol Studies, London ec.europa.eu/health-eu/news_alcoholineurope_en.htm

Gerritsen, H. (2000), The control of fuddle and flash: a sociological history of the regulation of alcohol and opiates, Brill Academic Publishers, Leiden.

Walton, S. (2003), Out of it: a cultural history of intoxication, Random House, New York.

Tobacco

European Commission (2007), Green paper — towards a Europe free from tobacco smoke: policy options at EU level, Health & Consumer Protection Directorate-General.

Kopp, P., Fenoglio, P. (2000), 'Le coût social des drogues licites (alcool et tabac)', in Observatoire Français des Drogues et Toxicomanies 22.

In thinking about cannabis policy, what can be learned from alcohol and tobacco?(2)

Robin Room

If caffeine and other such banalised psychoactive substances are left out of consideration, almost everywhere in Europe today cannabis is one of the 'big three' of psychoactive substances, along with alcohol and tobacco. Although the international drug control system applies continuing pressure against it, cannabis has taken on a semi-legal status in many parts of Europe, at least at the level of the user.

This raises the question, what can be learned from the extensive literatures on alcohol and tobacco policy which might be useful in thinking about cannabis policy? The question is obviously applicable in a situation where cannabis has a legal or semi-legal status. It also has some applicability where cannabis has a clearly illegal status. Total prohibition was once fairly common in both the tobacco (Austin, 1978) and alcohol fields, in the case of alcohol applying less than a century ago in many parts of Europe — Norway, Finland, Iceland, the Russian Empire and then the early Soviet Union. Studies of what happened during alcohol prohibition, and also of what happened with legalisation, are of interest in thinking about cannabis policy.

Taking into account the alcohol and tobacco experience is particularly important because the field of empirical studies of cannabis policy is so little developed. A landmark in this field is the sustained effort by MacCoun and Reuter (2001) to assemble the evidence on the likely results of illicit drug legalisation in the USA. A byproduct of this study, however, was an underlining of how weak the evidence base is in this area. A recent review of 'the contribution of economics to an evidence-based drugs policy' (MacDonald, 2004) found agreement that illicit drug use showed some responsiveness to price, but that 'there is not yet a consensus on the possible range of price elasticities for certain drugs'. Evidence on the effects of depenalisation of marijuana still depends on a rather small range of studies (Single, 1989; MacCoun and Reuter, 2001; Donnelly et al., 2000), in some cases of paradoxical instances where the reach of the criminal law actually widened (Single et al., 2000).

Traditions of studying the impact of alcohol and tobacco policies

Alcohol policy impact studies

There is a very substantial literature on the effects of alcohol control policy changes on drinking amounts, patterns and problems. Data used in these analyses has primarily been of two types: social and health statistics, such as alcohol sales data, police statistics and mortality and hospital discharge data; and before-and-after surveys, mostly cross-sectional but in a few cases longitudinal. Some studies have included control sites, and one or two notable studies have included a random assignment to intervention or control condition (e.g. Norstreim and Skog, 2003).

Alcohol policy impact studies have primarily been carried out in a limited range of countries, generally excluding both the developing world (Room et al., 2002) and Southern European wine cultures. Even between somewhat similar societies, there are substantial variations in the research emphasis on particular topics (Room, 2004).

There is an imperfect fit between what those involved in liquor licensing decisions may want to know and what is available in the literature on alcohol controls. This gap between the content of alcohol control legislation and the research literature has been documented in the USA (Wagenaar and Toomey, 2000), but exists also elsewhere — particularly in countries where the tradition of alcohol policy impact studies has not been strong. The studies are sometimes done because a change was controversial in a particular jurisdiction, and funding an evaluation was a way of defusing the controversy. Other studies have been opportunistic, where a researcher seizes the chance to do a 'natural experiment' study ('natural' here means that the researcher did not have a voice in the circumstances of the change, so that the study's design is often constrained). Often studies have made use of available data, such as per-capita consumption data or mortality registers. Since research is usually a national government responsibility, its topical focus is not necessarily attuned to the concerns of local jurisdictions.

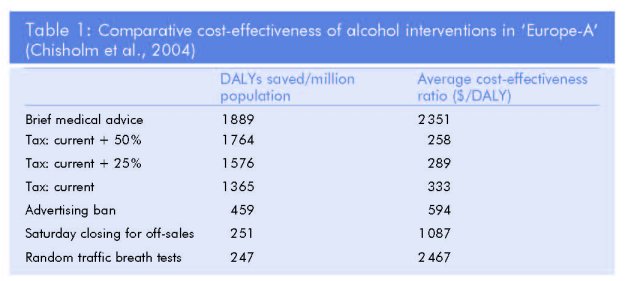

Nevertheless, the growth of the literature evaluating the effects of alcohol controls has been a substantial achievement involving a number of national traditions, and lessons from it can be applied, with suitable caution, across jurisdictions, and drawn on in thinking about cannabis policy. Reviews are now available (e.g. Babor et al., 2003; Room et al., 2002) which summarise the findings and implications of the literature. A new step forward, as part of the WHO-CHOICE programme (`Choosing interventions which are cost effective', available at: www3.who.int/whosis/menu.cfm?path=evidenc e,cea&language=english), has been the estimation of the relative cost-effectiveness of different strategies and combinations of strategies to prevent alcohol-related problems (Chisholm et al., 2004), in terms of dollars per saved DALY (disability-adjusted life year). Table 1 shows some of the results from these analyses for the 'Europe-A' WHO subregion, which is roughly coextensive with the European Union. Since evidence was lacking for any effectiveness of mass media persuasion of school-based education, these strategies were excluded from the analysis as having no apparent cost-effectiveness. In terms of cost-effectiveness per DALY saved in developed European countries, then, the policies tested ranked as follows (most cost-effective first): taxes (even without counting the revenues from taxes); advertising ban; closing times (specifically, Saturday closing for off-sales); random traffic breath tests; screening and brief medical advice; and (with no cost-effectiveness) mass media persuasion and school education.

Tobacco policy impact studies

There is also a substantial literature of tobacco policy impact studies. As for alcohol, there are several synthetic reviews of the literature (e.g. Jha and Chaloupka, 1999; Rabin and Sugarman, 2001). Whereas the alcohol policy impact literature aims primarily at assessing the impact of specific interventions, the equivalent tobacco literature is often aimed at assessing the impact of anti-smoking policy packages as a whole (e.g. Siegel and Biener, 1997; Pierce et al., 1998). This partly reflects the reality that policy changes in the tobacco area have often involved the simultaneous application of multiple strategies. It also reflects the different circumstances of the substances in the countries where the main policy impact studies have been done. For alcohol the status quo ante has often been a detailed system of controls on availability and on places and times of use, with the literature often studying what happens when one or more of the controls is removed or relaxed. For tobacco the status quo ante has been very

little control on availability, and the literature is primarily studying the effect of initiating measures such as anti-smoking persuasion campaigns, controls on places of use and on age of purchase, and raised prices, which have been increasingly put forward as a coordinated package.

Comparing the alcohol policy and tobacco control literatures, one can find clear differences in emphasis. Taxes loom even larger as a strategy for tobacco than they do for alcohol (see Chaloupka et al., 2001). Although a much greater proportion of the total harms from alcohol than from tobacco are to others, the aim of reducing harm from 'second-hand smoke' has proved politically potent for tobacco control in a way that has only been true for drink-driving in alcohol policy. Accordingly, a strong emphasis in the tobacco literature has been put on environmental prohibitions — bans on smoking at work and in public places — which are already, to a considerable degree, taken for granted with respect to alcohol.

In this connection, Hauge (1999) has argued that the modern emphasis on health harm to the drinker has been a policy mistake in the alcohol field. The two policy impact literatures have also reached substantially different conclusions about the effects of counter-advertising campaigns. This probably primarily reflects the differences in the aims and content of the campaigns, as well as differences in the social politics of the substances. The anti-smoking campaigns which have proved effective (Pechman and Reibling, 2000; Sly et al., 2001, 2002; Wakefield et al., 2003) have often involved frontal attacks financed by governmental agencies on the bona fides of the tobacco industry. This is an unusual enough occurrence in a capitalist society to have impressed teenagers, at least in the short run — although the campaigns have often proved politically unsustainable in the longer run (Givel and Glantz, 2000). Also, more available in the nicotine field, though underutilised, has been the option of harm reduction through changing the mode of use of the psychoactive substance (Shiffman et al., 1997).

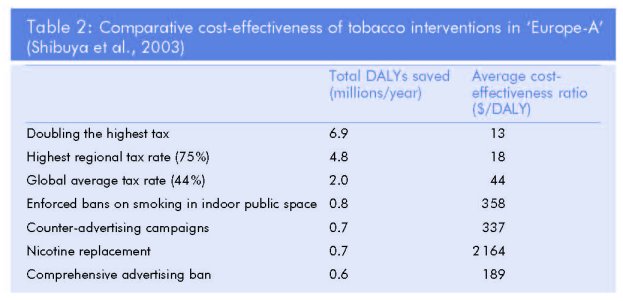

As for alcohol, the WHO-CHOICE programme has calculated estimated cost-effectiveness ration for specific interventions, and for combinations of interventions (Shibuya et al., 2003). Results for 'Europe-A' are shown in Table 2. Again, the cost-effectiveness calculations exclude the government revenue gained from the tax from the calculations. A comparison of the results suggests that somewhat more conservative assumptions were used in the alcohol calculations than in the tobacco calculations.

Instead of impact studies: 'expert knowledge'

As will be apparent from the discussion above, there is great variability in the availability of published evidence on the effects of policies governing the availability and use of psychoactive substances, both licit and illicit. It should be noted, however, that the lack of a formal academic literature does not mean a lack of practical knowledge of the effects of policies. As Valverde (2003) has documented for the alcohol control system in Ontario, those staffing regulatory systems typically build up a job-based stock of knowledge, often mixing 'facts' and values, which guide their everyday actions. On the other hand, there is ample experience from medicine and other professions with such practice knowledge that its conclusions about effects are often mistaken, when subjected to the harsh test of well-designed outcome and impact studies. It would be advantageous, with respect to cannabis policy, and for that matter policy on all psychoactive substances, to move to an 'evidence-based' standard of policymaking. This requires a substantial investment in developing the evidence on which the policymaking can be based.

Some specific lessons from alcohol and tobacco policy research

Does consumption necessarily go up after legalisation?

The answer to this question seems to be, 'it depends'. The total alcohol consumption does not seem to have changed much after the legalisation of alcohol at the end of US Prohibition (Gerstein, 1981). But this was in a circumstance of economic depression, and with quite stringent alcohol control regimes replacing prohibition in many US states. As MacCoun and Reuter (2001 pp. 356-366) conclude, in the US context, depenalisation of use seems not to increase cannabis use, but outright legalisation probably would. However, the circumstances of legalisation would certainly affect this, and stringent regulatory control of cannabis would be likely to hold consumption down (see below).

What regulatory alternatives are there to prohibition?

The history of control of alcohol and other psychoactive substances is full of examples of different regulatory regimes, and the effects of some of them have been evaluated. One part of such a system is the regulation of the market in the substance, including retail sales.

One option for such regulation is a kind of prescription or permit system, issuing licences to individuals to purchase cannabis. This could be a system organised with physicians and pharmacists as the gatekeepers, like prescription systems for psychoactive medications. Such a system, with a mental health screening component, might be adopted if there is a major policy concern about cannabis precipitating schizophrenia. But it seems more likely that a more bureaucratised system, as for driver's licences, would be adopted. Sweden's 'Bratt system' for alcohol in the decades before 1955 had a version of such individualised controls (Frânberg, 1987).

A second option is a rationing system, which allots a maximum purchase amount to the purchaser in a particular time period. The Swedish Bratt system included a rationing system, and there are also some more recent examples of alcohol rationing (Schechter, 1986).

A third option is a government monopoly system, where the state monopolises one or more levels of the production, distribution and sale of the substance. Such monopoly systems presently exist for alcohol in 18 US states and all Canadian provinces (though only a few of the states and nine of the provinces have monopoly stores at the retail level), as well as in all Nordic countries, except Denmark. There have been state monopoly systems for cannabis in India, and monopoly systems for opiates were a feature in the Asian territories of the empires of the first half of the 20th century (Brook and Wakabayashi, 2000). The medicinal cannabis office set up by the Dutch government may be seen as a similar monopoly. There is a recent Canadian proposal for government shops to take over the sale of tobacco (CaIlard et al., 2005), and there have also been proposals in Canada and in the US northwest for cannabis to be legalised for sale in government alcohol stores.

The fourth option is a licensing system, where private commercial enterprises are licensed to sell the product, with the licence conditional on the seller abiding by the rules of a regulatory system. Such a system is common for alcoholic beverages, as an alternative to a government monopoly. A licensing system is used in the Netherlands to regulate the 'coffee shops' that allow non-criminalised retail purchase of cannabis (see Korf, this monograph). Specific licensing systems for retail tobacco sales have become common, for instance, in the USA in recent years (www.healthpolicycoach.org/doc. asp?id=3147).

Is a rationing system effective?

There is good evidence that rationing systems for alcohol hold down the levels of problems from alcohol, whether in terms of violence (Schechter, 1986) or long-term health consequences (Norstriim, 1987). When the Swedish system of individualised rationing was abolished in 1955, for instance, the rate of liver cirrhosis mortality jumped by one-third in the following year, reflecting the removal of a constraint on the consumption of heavy drinkers (Norstrtim, 1987).

Is a government monopoly system effective?

It has been shown that government monopoly of retail sales can be quite effective in holding down retail sales of alcoholic beverages (Her et al., 1999). The effects are partly through associated characteristics which have been shown to be effective in holding down sales: limitation of the number of sales outlets, and limitation of hours and days of sale. Government management of the system also results in more professionalised employees, less likely, for instance, to sell to those who are under legal age. And it removes the private profit motive, which tends to drive consumption upwards, not only in terms of sales promotion but also in terms of political influence from private actors to loosen restrictions in availability (Room, 2001).

Do taxes on psychoactive substances affect the amount of consumption?

As already indicated in Table 2, the answer to this from both the tobacco and the alcohol literature is an emphatic 'yes'.

Can regulatory policies affect the potency of the psychoactive substance used?

The answer to this question is clearly 'yes'. At least a dozen US states, for instance, ban Everclear spirits, a product that is 95% pure ethanol. The legal availability of lesser-strength alcoholic beverages (including regular-strength spirits) means that there is no substantial black market for Everclear.

Prior to 1915, spirits were the main form of alcohol consumed in all Nordic countries. By the 1980s, the main form was beer (wine has now replaced beer in Sweden as the most used form in terms of alcohol content). The changeover from spirits to beer was accomplished very quickly in Denmark by a swingeing tax on spirits imposed during the First World War (Bruun et al., 1975). In other Nordic countries the change was more gradual, accomplished partly by differential taxation and partly by making low- and middle-strength beer more widely available than other alcoholic beverages.

Whether a more potent form of the psychoactive substance is more harmful than a less potent form is an apparently easy question to answer for alcohol, in the sense that most of the harm from drinking alcohol comes from the psychoactive ingredient itself. Nevertheless, it can be questioned how much effect the Nordic political effort to channel consumption toward beer and wine and away from spirits had on alcohol-related problems. The political intent was to moderate drinking customs along with the change in beverage, but there is little evidence that this happened. At least in the short run, the 'trouble per litre' of alcohol did not decline when beer was made much more available in Finland in 1969, and consumption rose by about 50% (MakeId et al., 1981).

For tobacco, as for cannabis, the issue of whether greater potency is more harmful is obviously more complicated, since much of the harm results not from the psychoactive ingredient but from what accompanies it, particularly in smoked form (tars, carbon monoxide). Thus, low-nicotine, high-tar tobacco cigarettes are likely to cause more health harm than high-nicotine cigarettes, since the smoker will get more tar and carbon monoxide in the course of reaching the same level of nicotine. Analogously, it should not be assumed that a higher THC content will be more harmful.

Interacting with the issue of potency is the issue of mode of ingestion. It is likely that there is less risk to health from eating or vapourising marijuana than from smoking it. However, for licit as well as illicit psychoactive substances, there is relatively little

systematic knowledge on the effects in a population of measures designed to favour one mode of ingestion over another. Often policies are made on the basis of vague fears rather than systematic knowledge. For instance, the Swedish form of snuff, known as snus, is banned for sale in the European Union, other than in Sweden, on the grounds that it is a health hazard. There are good public health arguments for promoting the use of snus as a much less harmful alternative to smoking cigarettes, although these arguments are also disputed (Gilliam and Rosaria Galanti, 2003). But at present the European legal system considers that it must make decisions on whether snus should remain banned on the basis of suppositions.

Snus is much less deadly than smoked tobacco ... [But] one cannot conclude with certainty whether offering snus on the market would principally have the effect of encouraging smokers to stop smoking (a 'substitution effect') or of facilitating, on the contrary, the path towards consumption of tobacco (a 'passage-way effect') ... The insufficiency of data and the scientific uncertainty [is about] the supposed behaviour of the public. The question which poses itself is that of knowing if, in these circumstances, the ban on snus can be considered as a protective measure efficacious for public health.

(Gee!hoed, 2004; translated from French version)

Can regulatory policies affect the location and circumstances of use?

Again, the answer to this is clearly positive. One result of prohibitory policies is to push consumption into private or semi-private places. The Dutch coffee shop model of limited cannabis availability in designated places may be seen as holding down the public nuisance from cannabis smoking (see Korf, this monograph).

Again, however, the issue of which locations of use are more harmful has turned out to be complicated in the alcohol field. Drinking in streets and parks is usually seen as increasing the nuisance for others (Teirronen, 2003), but the perception has varied at different times on whether drinking in a tavern or restaurant is more or less harmful than drinking at home. On the one hand, control laws in US states at repeal of prohibition often forbid sale of 'liquor by the drink', since at that time the 'old-time saloon' was defined as the seat of most alcohol problems. But when 'liquor by the drink' was finally allowed in North Carolina, no effect on alcohol-related harm statistics could be detected (Blose and Holder, 1987). On the other hand, Finnish authorities in the 1970s presumed that drinking in a bar or restaurant would be more restrained than drinking at home. But in fact, Partanen (1975) found that the empirical results in Helsinki were the opposite: 'people do not drink any more at home than in a restaurant, but they do it in a more leisurely manner, which seems to lead to a lower degree of intoxication'. The issue of the harm associated with specific circumstances of use should be treated as an empirical question rather than a matter of 'expert knowledge'.

What about the impact of the European single market and of trade agreements and disputes?

The prohibition on cannabis sales under the international drug control regime is presumably primarily responsible for the fact that there have been so far no challenges to any legislation that discriminates, for instance, between cannabis grown in the country and imported cannabis. Such challenges have been a regular occurrence for both tobacco and alcohol, and both the single market mechanisms of the European Union and the trade agreements administered by the World Trade Organisation have created substantial difficulties for alcohol and tobacco control regimes (e.g., Room and West, 1998; Taylor et al., 2000). The new Framework Convention on Tobacco Control may help to remedy this situation, but the issue of whether it overrides trade agreements

is not settled (Room, 2006). It would thus be wise for any move to legalise cannabis, however restrictive the regulations, to take into account the need to exempt hazardous substances from coverage under trade agreements and disputes.

Conclusion

Although the literatures have their limits, studies of the impact of tobacco and alcohol policies are much more numerous and cover a broader territory than the equivalent studies for cannabis. In the absence of formal studies, estimation of the impact of laws and policies remains a matter for 'expert knowledge', although it is clear from the alcohol and tobacco fields, as well as from medical and other research, that expert knowledge based only on general principles or practical experience is often wrong. Any government that is serious about making laws and policy that have specific intended effects needs to build funding into any policy initiative for a scientific evaluation of its actual effects, both intended and otherwise.

The alcohol and tobacco research findings suggest some general conclusions about the relative strength of different prevention and policy strategies. As with cannabis, it is difficult to show lasting effects from public information campaigns and school education on tobacco and alcohol. On the other hand, laws which channel rather than forbid use — for instance, laws against drink-driving — have been shown to be effective. In general, the findings in both the alcohol and the tobacco literatures underline the power of regulatory approaches, including taxation, in limiting the harm from psychoactive substances. Such regulations are more easily and effectively applied where there is a legal market, since in that case there are licensed actors in the market who have something to lose by having their licences suspended or taken away. From this perspective, the state ties one hand behind its back with a prohibition regime, since its ability to control the market is greatly restricted.

On the other hand, it must be acknowledged that Europe has serious health and social problems from both tobacco and alcohol. In both areas, the European Union is now taking some steps to assist national and local governments in reducing the levels of problems. But a clear difficulty in this effort, both at EU and national levels, is the entrenched political power of vested economic interests in maintaining the size of the alcohol and tobacco markets. Any shift towards regulatory regimes for cannabis would be wise to take account of this, and to build into cannabis policies insulation from the potential influence of market forces and interests.

References

Austin, G. (1978), Perspectives on the history of psychoactive substance use. NIDA Research Issues 24, US National Institute on Drug Abuse, Rockville, MD.

Babor, T., Caetano, R., Casswell, S., Edwards, G., Giesbrecht, N., Graham, K., Grube, J., Gruenewald, P., Hill, L., Holder, H., Homel, R., êsterberg, E., Rehm, J., Room, R., Rossow, I. (2003), Alcohol: no ordinary commodity – research and public policy. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Blose, J. O., Holder, H. D. (1987), Liquor-by-the-drink and alcohol-related traffic crashes: a natural experiment using time-series analysis. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 48: 52-60.

Brook, T., Wakabayashi, B. T. (eds) (2000), Opium regimes: China, Britain, and Japan 1839–1952, University of California Press, Berkeley.

Bruun, K., Edwards, G., Lumio, L., Mäkelä, K., Pan, L., Popham, R. E., Room, R., Schmidt, W., Skog, O.-J., Sulkunen, P., Österberg, E. (1975), Alcohol control policies in public health perspective 25, The Finnish Foundation for Alcohol Studies, Helsinki.

Callard, C., Thompson, D., Collishaw, N. (2005), Curing the addiction to profits: a supply-side approach to phasing out tobacco. Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives and Physicians for a Smoke-Free Canada, Ottawa.

Chaloupka, F. J., Wakefield, M., Czart, C. (2001), ‘Taxing tobacco: the impact of tobacco taxes on cigarette smoking and other tobacco use’, 39–71 in Rabin, R. L., Sugarman, S. D. (eds), Regulating tobacco, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 39–71.

Chisholm, D., Rehm, J., van Ommeren, M., Monteiro, M., Frick, U. (2004), The comparative costeffectiveness of interventions for reducing the burden of heavy alcohol use. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 65: 782–793.Christie, P., Ali, R. (2000), ‘Offences under the cannabis expiation notice scheme in South Australia’, Drug and Alcohol Review 19: 251–256.

Connolly, J. (2005), The illicit drug market in Ireland: overview no. 2, Health Research Board, Dublin.

Costes, J-M. (ed.) (2007), Cannabis: données essentielles, OFDT, Paris.

Donnelly, N., Hall, W., Christie, P. (2000) ‘The effects of the cannabis expiation notice system on the prevalence of cannabis use in South Australia: evidence from the National Drug Strategy Household Surveys 1985–95’, Drug and Alcohol Review 19: 265–269.

Frånberg, P. (1987), ‘The Swedish Snaps — A History of Booze, Bratt, and Bureaucracy — a summary’, Contemporary Drug Problems 14: 557–611.

Geelhoed, M. L. A. (2004), Conclusions de l’avocat générale M.L.A. Geelhoed [on cases C-434/02 and C-210/03]. Luxembourg: Court of Justice of the European Communities, 7 September

Gerstein, D. (1981), ‘Alcohol use and consequences’, in Moore, M., Gerstein, D. (eds), Alcohol and public policy: beyond the shadow of prohibition, National Academy Press, Washington DC, 182–224.

Gilljam, H., Rosaria Galanti, M. (2003), ‘Role of snus (oral moist snuff) in smoking cessation and smoking reduction in Sweden. With other papers and commentaries’, Addiction 98: 1183–1207.

Givel, M. S., Glantz, S. A. (2000), ‘Failure to defend a successful state tobacco control program: policy lessons from Florida’, American Journal of Public Health 90: 762–767.

Hauge, R. (1999) ‘The public health perspective and the transformation of Norwegian alcohol policy’, Contemporary Drug Problems 26: 193–207.

Her, M., Giesbrecht, N., Room, R., Rehm, J. (1999) ‘Privatizing alcohol sales and alcohol consumption: evidence and implications’, Addiction 94: 1125–1139.

Jha, P., Chaloupka, F. J. (1999), Curbing the epidemic: governments and the economics of tobacco control, World Bank, Washington DC

MacCoun, R., Reuter, P. (2001), Drug war heresies: learning from other vices, times and places, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

MacDonald, Z. (2004), ‘What price drug use? The contribution of economics to an evidence-based drugs policy’, Journal of Economic Surveys 18: 113–152.

Mäkelä, K., Österberg, E., Sulkunen, P. (1981), ‘Drink in Finland: increasing alcohol availability in a monopoly state’, in Single, E., Morgan, P., de Lint, J. (eds), Alcohol, society, and the state: 2. The social history of control policy in seven countries, Addiction Research Foundation, Toronto, 31–60.

Norström, T. (1987), ‘Abolition of the Swedish alcohol rationing system: effects on consumption distribution and cirrhosis mortality’, British Journal of Addiction 82: 633–641.

Norström, T., Skog, O.-J. (2003), ‘Saturday opening of alcohol retail shops in Sweden: an impact analysis’, Journal of Studies on Alcohol 64: 393–401.

Partanen, J. (1975), ‘On the role of situational factors in alcohol research: drinking in restaurants vs. drinking at home’, Drinking & Drug Practices Surveyor 10: 14–16.

Pechman, C., Reibling, E. T. (2000), Anti-smoking advertising campaigns targeting youth: case studies from USA and Canada. Tobacco Control 9 (Suppl. II): 18–31.

Pierce, J. P., Gilpin, E. A., Emery, S. L., White, M. M., Rosbrook, B., Berry, C. C. (1998), ‘Has the California tobacco control program reduced smoking?’, Journal of the American Medical Association 280: 893–899.

Pudney, S. et al. (2006), ‘Estimating the size of the UK illicit drug market’, in Singleton et al. (eds), Measuring different aspects of problem drug use: methodological developments, Home Office Online Report 16/06, London.

Rabin, R. L., Sugarman, S. D. (eds) (2001), Regulating tobacco, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Room, R. (2001), ‘Why have a retail alcohol monopoly?’ Paper presented at an International Seminar on Alcohol Retail Monopolies, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, 19–21 August www.bks.no/retail.htm

Room, R. (2004), ‘Effects of alcohol controls: Nordic research traditions’, Drug and Alcohol Review 23: 43–53.

Room, R. (2005), ‘Social policy and psychoactive substances: a review’, Report to the Foresight Brain Science, Addiction and Drugs Project, Foresight Directorate, Office of Science and Technology, London www.foresight.gov.uk/Previous_Projects/Brain_Science_Addiction_and_Drugs/Reports_and_Publications/ScienceReviews/Social%20Policy.pdf

Room, R. (2006), International control of alcohol: alternative paths forward. Drug Alcohol Rev. 25: 581–595.

Room, R., West, P. (1998), ‘Alcohol and the U.S.-Canada border: trade disputes and border traffic problems’, Journal of Public Health and Policy 19: 68–87.

Room, R., Jernigan, D., Carlini-Marlatt, B., Gureje, O., Mäkelä, K., Marshall, M., Medina-Mora, M. E., Monteiro, M., Parry, C., Partanen, J., Riley, L., Saxena, S. (2002), Alcohol and developing societies: a public health approach, Finnish Foundation for Alcohol Studies, Helsinki and World Health Organisation, Geneva.

Schechter, E. J. (1986), ‘Alcohol rationing and control systems in Greenland’, Contemporary Drug Problems 15: 587–620.

Shibuya, K., Ciercierski, C., Guindon, E., Bettcher, D. W., Evans, D. B., Murray, C. J. L. (2003), ‘WHO framework convention on tobacco control: development of an evidence based global public health treaty’, British Medical Journal 327: 154–157.

Shiffman, S., Gitchell, J., Pinney, J. M., Burton, S. L., Kemper, K. E., Lara, E. A. (1997), ‘Public health benefit of over-the-counter nicotine medications’, Tobacco Control 6: 306–310.

Siegel, M., Biener, L. (1997), ‘Evaluating the impact of statewide anti-tobacco campaigns: the Massachusetts and California tobacco control programs’, Journal of Social Issues 53: 147–168.

Single, E. (1989), ‘The impact of marijuana decriminalisation: an update’, Journal of Public Health Policy 10: 456–466.

Single, E., Christie, P., Ali, R. (2000), ‘The impact of cannabis decriminalisation in Australia and the United States’, Journal of Public Health Policy 21 (2): 157–186.

Sly, D. F., Hopkins, R. S., Trapido, E., Ray, S. (2001), ‘Influence of a counteradvertising media campaign on initiation of smoking: the Florida “truth” campaign’, American Journal of Public Health 91: 233–238.

Sly, D. F., Trapido, E., Ray, S. (2002), ‘Evidence of the dose effects of an antitobacco counteradvertising campaign’, Preventive Medicine 35: 511–518.

Taylor, A., Chaloupka, F. J., Guindon, E., Corbett, M. (2000), ‘The impact of trade liberalization on tobacco consumption’, in Jha, P., Chaloupka, F. J. (eds), Tobacco Control in Developing Countries, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 343–364.

Törronen, J. (2003), ‘The Finnish press’s political position on alcohol between 1993 and 2000’, Addiction 98: 281–290.

Valverde, M. (2003), Law’s dream of a common knowledge, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

Wagenaar, A. C., Toomey, T. L. (2000) ‘Alcoholic policy: the gap between legislative action and current research’, Contemporary Drug Problems 27: 681–733.

Wakefield, M., Flay, B., Nichter, M., Giovino, G. (2003), ‘Effects of anti-smoking advertising on youth smoking: a review’, Journal of Health Communication 8: 229–247.

WODC (2006), ‘Coffeeshops en cannabis’, in Justitiële verkenningen 2006/01, WODC, Intraval, Groningen, 46–60.

Editorial postscript

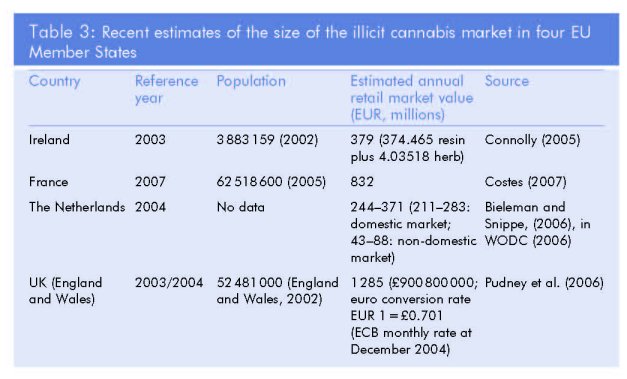

This chapter focuses deliberately on experiences with regulating alcohol and tobacco. It does not include crystal gazing for regulation of legalised cannabis. In the production of the monograph, some reviewers felt that some more information on specific regulatory controls on cannabis was required. The chapter, however, remains useful in drawing attention to the many ‘unknowns’ faced when regulating psychoactive substances. For illicit drugs in general, economic analysis of market size is relatively immature, relies on broad assumptions and triangulation of diverse datasets (seizures, prevalence, retail prices, arrests, potency, etc.), and usually implies a large margin for error. So significant preparatory work would need to be done before regulatory models could be seriously considered for cannabis. At this point, it is premature to discuss topics such as product certification and licensing, feasibility studies, econometric analysis, market sizing, regulatory standards, fiscal forecasting, seasonality, etc. with any degree of certainty.While some exploratory work has been done on market sizing in the EU, estimates to date remain problematic. In particular, regulation would need to respond to findings that home-grown self-supply and informal supply ‘among friends’ make up a substantial amount of the market in EU countries (see Legget and Pietschmann, this monograph) (Table 3).

In terms of further reading on economic controls of cannabis in a (hypothetical) regulated market, the subject has recently experienced a revival in interest. This is true both of economic and statistical journals, as well as in the usual drugs and public health journals. As a basic introduction, the difficulties of drug market sizing formed the subject of a chapter in the UNODC’s World Drug Report 2005 (UNODC, 2005). Specific studies on cannabis are generally based on patterns that follow the decriminalisation of cannabis use. Specific studies include those in Australia (Clements and Zhao, 2005), British Columbia (Easton, 2004) and Massachusetts (Miron, 2003). In Europe, while a regulated cannabis market is frequently a subject of lobbyists’ pamphlets (e.g. Holtzer, 2004; Atha, 2004), policy-oriented study has either been restricted to domestic market profiling (Bramley-Harker, 2001; Pudney, 2004) or has favoured the broad-brush analysis of illicit drugs in general (Clark, 2003; Bretteville-Jensen, 2006). A recent study in France (Ben Lakhdar, 2007) provides a useful exploration of how the French cannabis market is structured, in terms of volume and values. Such quantitative study is rare in Europe, yet would contribute greatly to our understanding of the economics of cannabis.

(1) EMCDDA Annual Report 2006, selected issue: 'European drug policies: extended beyond illicit drugs?'.

(2) This paper draws in part on Room (2005).

Selected reading on a regulated cannabis market

Atha, M. (2004), Taxing the UK drugs market, Independent Drug Monitoring Unit.

Ben Lakhdar, C. (2007), Le trafic de cannabis en France, OFDT, Paris.

Bramley-Harker, E. (2001), Sizing the UK market for illicit drugs, RDS Occasional Paper 74: 35–46, Home Office, London.

Bretteville-Jensen, A. (2006), ‘To legalize or not to legalize? Economic approaches to the decriminalization of drugs’, Substance Use and Misuse 41 (4): 555–565.

Cameron, L., Williams, J. (2001), ‘Substitutes or Complements? Alcohol, Cannabis and Tobacco’, The Economic Record 77 (236): 19–34.

Caputo, M., Ostrom, B. (1994), ‘Potential tax revenue from a regulated marijuana market: a meaningful revenue source’, American Journal of Economics and Sociology 53: 475–490.

Chaloupka, F. et al. (eds) (1999), The economic analysis of substance use and abuse: an integration of econometric and behavioral economic research, University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Clark, A. (2003), The economics of drug legalization, Delta, Paris.

Clements, K. (2006), ‘Pricing and packaging: the case of marijuana’, Business Journal 79: 2019–2044.

Clements, K., Zhao, X. (2005), ‘Economic aspects of marijuana’, University of Western Australia, conference paper.

Easton, S. (2004), ‘Marijuana growth in British Columbia’, Public Policy Sources, Fraser Institute Occasional Paper.

Farrelly, M., Bray, J., Zarkin, G., Wendling, B. (2001), ‘The joint demand for cigarettes and marijuana: evidence from the national household surveys on drug abuse’, Journal of Health Economics 20: 51–68.

Gettman, J. (2006), ‘Marijuana Production in the United States’, The Bulletin of Cannabis Reform, Issue 2, December.

Hall, W., Pacula, R. (2003), ‘Cannabis as a legal substance’, chapter 18 in Hall, W., Pacula, R. (2003), Cannabis use and dependence: public health and public policy, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Holtzer, T. (2004), Globales Cannabisregulierungsmodell/Global cannabis regulation model, Verein für Drogenpolitik, Mannheim.

Kopp, P., Fenoglio, P. (2000), ‘Le coût social des drogues licites (alcool et tabac)’, Toxicomanies 22, Observatoire Français des Drogues.

MacCoun, R., Reuter, P. (2001) Drug war heresies: learning from other vices, times and places. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Miron, J. (2003), The effect of marijuana decriminalization on the budgets of Massachusetts governments, with a discussion of decriminalization’s effect on marijuana use, Drug Policy Forum of Massachusetts.

Pudney, S. (2004), ‘Keeping off the grass? An econometric model of cannabis consumption by young people in Britain’, Journal of Applied Econometrics 19 (4): 435–453.

Selvanathan, S., Antony Selvanathan, E. (ed.) (2005), The demand for alcohol, tobacco and marijuana: international evidence, Ashgate Publishers, London.

Single, E., Christie, P., Ali, R., (2000), ‘The impact of decriminalization in Australia and the United States’, Journal of Public Health Policy 21: 157–186.

Thies, C., Register, F., (1993), ‘Decriminalisation of marijuana and the demand for alcohol, marijuana and cocaine’, The Social Science Journal 30: 385–399.

UNODC (2005), ‘Estimating the value of illicit drug markets’, Chapter 2 of World Drugs Report 2005, Vienna.

Wilkins, C. et al. (2002), ‘The cannabis black market and the case for the legalisation of cannabis in New Zealand’, Social Policy Journal of New Zealand 18: 31–43.

Wodak, A., Cooney, A. (2004), ‘Should cannabis be taxed and regulated?’, Drug and Alcohol Review 23(2): 139–141.

Zhao, X., Harris, M. (2004), ‘Demand for marijuana, alcohol and tobacco: participation, levels of consumption, and cross-equation correlations’, Economic Record 80: 394–410.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|