8. 1 Epidemic vs. Symptom

| Books - A Society with or without drugs? |

Drug Abuse

8. 1 Epidemic vs. Symptom

As was the case in the bill from 1968, the government did not use

epidemic as a metaphor to describe the spread of drug abuse. On the

contrary, Lidbom pointed several times to the impropriety of the

metaphor. However, in the Riksdag debates, right-wing MPs in

particular frequently used the epidemic metaphor, referring to theories

of Bejerot. Proponents of the epidemic theory opposed all definitions in

which negative social and psychological disturbances are a cause of

drug abuse, which they denoted the "symptom theory". A statement

from the government on assistance may illustrate the "symptom"

theory:

The underlying idea for assistance is that abuse of drugs and other addictive

substances can be regarded as primarily a social and social psychological problem

triggered by a dysfunction of the individual's interaction with other people and

phenomena in the person's regular milieu (Prop. 1972: 67:24).

According to the epidemic theory, however, people without such

symptoms, e.g. members of the medical profession, had also succumbed

to drug addiction. There must therefore be another primary cause,

namely, the substance itself: "We can speak of an epidemic that hits

blindly and independently of social and psychological preconditions"

(Rd, 1972: 87: 35). One consequence of the epidemic theory is the

necessity to isolate the drug addict after detoxification to prevent

contacts with drugs and other drug abusers and subsequently a relapse

into drug abuse. Some conservative MPs tabled a reservation, urging

the standing committee to state that drug abuse was not only a symptom

of social problems but a epidemiological problem as well (SoU 1972:

21).

While most Social Democratic MPs described the problem in

moderate terms, members of the Conservative and the Liberal parties

but also several Social Democrats described the problem in terms of

crisis. Rune Gustavsson, of the Centre Party (in 1977 Minister of Social

Affairs) spoke of the drug trade as: "a business that break down large

parts of a whole people" (Ibid. 31). Yngve Persson (Social Democrat),

an influential union leader and member of the RNS, stated: "the only

possible goal for the drug policy is to free our people from this misery"

(Ibid. 78). However, despite the controversies about the origin of the

drug problem and parts of the action programme, and the most suitable

countermeasures, there was no disagreement on the seriousness of the

problem. The Riksdag overruled the reservations from non-socialist

MPs and a MP from the Communist Party and approved the decisions

of the standing committees (Rd 1972 no. 87: 92).

The Dutch threat

From the beginning of the first problem definition process, international

co-operation was regarded as crucial in the struggle against drug abuse.

Sweden worked hard in the international context to bring amphetamines

under international control. Against this background, it is

understandable that the Dutch decision not to sign and ratify the

Convention on Psychotropic Substances established in Vienna in 1971

provoked strong reactions in Sweden.75 This was particularly

provocative to because a major part of smuggled amphetamines was

alleged to come from the Netherlands. MPs, the Minister of Justice

(Lidbom), and the National Police Commissioner had unsuccessfully

tried to induce the Dutch to view the international trade in drugs more

realistically and to adjust their drug legislation. However, there was

more than the position of the Netherlands in amphetamine trafficking to

Sweden. The whole Dutch drug policy was a thorn in the flesh for many

MPs. Svensson (Social Democrat), for example, stated that:

From Holland a figure of 140,000 cannabis-dependent persons was reported. In

some cases, this did not cause serious problems, in other cases it was a prelude to an

abuse that certainly can become tremendously annoying for this country. What is it

one can discover there and I would like to bring up? Well, that the use [of cannabis]

is so widespread that it had become a political factor. The case is, if I am right, that

for political reasons there was no power to interfere. It would be terrible if we got

into the same situation, i.e. if milder drugs were so widespread that one would not

dare to interfere for fear of getting on the wrong side of large groups of youth (Ibid.

65).

Apart from the wrong interpretation of the survey, referred to in the

Baan Committee's report (lifetime prevalence was estimated at

140,000, not dependency), the observation of Svensson was not wholly

beside the point. The Dutch government indeed had to consider the

opinions of large sections of the population, not just groups of youth. In

addition, it was against the tradition of governance to act when large

dissent existed in society on a particular issue. Besides, repressive

interventions had failed to stop the dissemination of cannabis among

Dutch youth.

According to a Liberal MP, Hamrin, the difficulties in achieving a

united front against smuggling could be exemplified by the

Netherlands. The failure in making the Dutch understand what was at

stake and co-operate in halting the big dealers put Sweden in a

distressing position (Ibid. 76).

Against the backdrop of the negative results of these efforts, ten MPs

representing all parties in the Riksdag had sent a letter to the Dutch

government on 15 March 1972. It said:

We, personal members of the Swedish Riksdag, have noticed that statements made

by the Swedish government and the National Swedish Police Board to the Dutch

government to take measures in order to facilitate smuggling of drugs from Holland

have failed to receive sufficient positive reaction. Public opinion in Sweden finds it

inconceivable that Holland, with its strong legal traditions, does not consider itself

able to co-operate in measures that are more effective. We appeal to the Dutch

government to rapidly undertake actions that can facilitate interference in the

outrageous trade in drugs (Ibid. 76).

In order to keep the heat on the Dutch government, MPs should at

regular intervals and by appropriate methods call attention to the fact

that Sweden and other countries were worried and waiting for results

(Ibid. 77).

Minister Lidbom answered that nothing indicated that the Dutch in

the near future would radically change their attitude. There was no

other way than continuing to persuade the Netherlands to change course

by its own political institutions (Ibid. 31). How to persuade them was a

difficult question. Ultimately it was a matter of influencing (Dutch)

public opinion, and in this field voluntary good forces could co-operate:

organisations, newspapers, television, etc. Likewise opinion moulding

on a political level was important and an exchange of MPs and experts

from both countries would be desirable. The Swedish ambassador in

The Hague had been requested to investigate this possibility (Ibid. 81).

This episode illustrates that the Dutch drug policy was seen as a major

problem for the Swedish drug situation.

In the meetings of the BRÅ Narcotics Group, the Netherlands was

regularly discussed. In 1973, the country was still mentioned as the

main source of the trafficking of amphetamines to Sweden. In 1974, the

Dutch governmental plan to decriminalise cannabis had come to the

attention of the group (Meeting 3 May 1974). In 1975, Amsterdam was

pointed out as the centre for heroin distribution (Meeting 12 September

1974. However, the NPB emphasised the good co-operation with Dutch

police authorities (Meeting 1 November 1973).

Prelude

In the second half of the 1970s, some developments occurred that

eventually ended in a revision of the first problem definition. As in

1968/1969, one may speak of a hectic period in the history of the

Swedish drug policy.

In autumn 1975, the situation had not changed much since the

description by Lidbom in 1972. The Minister of Social Affairs reported

that no important changes had occurred during the last year. Severe

drug abuse was still confined to big city regions and cannabis more

spread out. Surveys indicated that the number of young people who had

tested drugs was decreasing (Prop. 1975/76: 100: 7: 164).

In the next budget bill, the situation was depicted somewhat

differently.76 While drug abuse was still a quantitatively limited

problem compared to alcohol abuse, it was a serious symptom of

psychosocial problems. The most widespread drug during the seventies

had been cannabis but, as the minister said: "the majority of those who

have tested cannabis cease after one or few occasions." Furthermore,

surveys indicated that the number of youngsters that tried drugs had

decreased (Prop. 1976/77: 100: 8: 171). Data on the prevalence of

severe drug abuse were not available, and to fill this gap a case-finding

study would start in March 1977. Data from other sources, however,

indicated that abuse of central stimulants was still dominating among

established addicts, but a shift to abuse of opiates was also noted.

Abuse of morphine base had disseminated on a small scale in the

Stockholm and Malmö regions since the beginning of the seventies. In

1974, police and assistance agencies had reported intravenous abuse of

heroin. For the NPB, this was reason to increase the number of police

officers and in 1977, special drug brigades were established in all

counties.

In summary, developments of prevalence and incidence of drug

abuse during the seventies so far was described in both positive and

negative terms. The most common drug was cannabis, but many

youngsters tried this only once or twice. Surveys among pupils in

primary school showed a descending trend in the prevalence rate of

those who had ever used drugs, especially during the first half of the

seventies. Intravenous abuse of amphetamines was confined to the

metropolitan regions. The increase in abuse of opiates and in particular

heroin was most worrying.

Directors-General once again

Against the background of the increase of heroin abuse in particular, the

minister appointed a Leading Group in March 1977. This group was to

recommend actions against drug abuse and to co-ordinate actions,

especially in the field of assistance. The body comprised the under-

secretaries of state of social affairs (chairman) and justice and a number

of directors-general of central authorities.77The Leading Group

appointed 15 regional working groups that were to map the local

situation.

In its final report, February 1978, the Leading Group reported that

the situation concerning treatment was still distressing, especially the

insufficient expansion of treatment homes. Another conclusion was that

shortcomings in assistance to drug abusers constituted the weak link of

the action programme. It was heavily undersized and, as emphasised by

police and customs, actions in other fields of the action programme had

therefore lost in effect (Ds S 1978: 2: 12). A major expansion of

treatment homes was necessary but also ambulatory care needed

reinforcement. The involvement of popular movements, unions, and

voluntary organisations in aftercare needed more attention. Many

municipalities called for family care as an alternative to intramural

care.78

Furthermore, the Leading Group concluded that abuse of alcohol was

by far the biggest abuse problem in the country. Drug abuse was most

pronounced in big city regions, but drug problems had been noted in

smaller cities too. Multiple drug use was common. The situation was

judged as serious and the need for actions on a broad front was stressed.

However, according to the Leading Group no innovative methods or

additional resources were needed but intensified co-ordination between

actors in the action programme (Ds S 1978: 2: 20).

The report from the Leading Group was followed by the first drug

policy bill presented by a non-socialist government in March 1978. As

always in Swedish drug policy bills, the dissemination of drugs was

described extensively. Surveys indicated that the number of young

people testing cannabis had decreased. As regarding severe abuse the

picture was more blurred. According to estimates by authorities, the

number of intravenous abusers in the country was between 10,000 and

15,000. Abuse of central stimulants had stabilised but was still

dominating. Abuse of heroin had gained ground quickly, especially

since 1976. The number of heroin abusers in Stockholm was estimated

at 1000 and another 1000 in the rest of the country (Prop. 1977/78:105:

17). Cocaine was quite rare but could be expected to spread.

According to the Minister of Social Affairs, Gustavsson, the situation

was very serious. As in previous governments, the starting point for a

drug policy was that society could not accept use of drugs for other than

medical and scientific purposes, all other use was abuse. However, a

new feature was introduced in this bill; drug abuse was also rejected as

a phenomenon that did not belong in Swedish culture. It was something

un-Swedish:

The struggle against drug abuse may not be confined to just limiting its presence

but must be directed at eliminating drug abuse. Drug abuse can never be accepted as

part of our culture (Ibid. 30).79

The statement was unanimously accepted by the standing committee on

social affairs, even if the committee and (the government) reckoned that

the measures as proposed in the bill would not ultimately solve the

problem (SoU 1977/78: 36: 4).

The minister described the drug problem in terms of the "symptom"

theory:

Concerning the origins of drug (and alcohol) abuse these can be an expression of

psychological and social difficulties whose causes often can be found in society's

own imperfections. In the struggle against abuse, which to the highest degree is a

matter of preventing its emergence and dissemination, these causes must be

combated (Ibid. 30).

Some examples of social causes were unemployment, deficiencies in

the work environment and unsatisfactory living and leisure conditions.

As before, it was emphasised that the struggle against abuse was a

matter for all sections of society.

The epidemic theory was not referred to in the bill or in the report

from the Leading Group. On the other hand, it would show up in the

Riksdag debate in May 1978. Several MPs could not understand why

the epidemic of drug abuse did not come under the Law on Contagious

Diseases, which would entail an obligation to apply for treatment.

Bejerot and his organisation the RNS were frequently mentioned. The

issue of compulsory care was not on the agenda because discussions

had to wait until a state committee had completed its report on this

subject. Nevertheless, some MPs referred to the Hassela treatment

homes community which had stressed the need for extending the

maximum age for compulsory care according to the Care of Young

Persons Act to 23 years (Rd 1978 no. 160: 60). The lack of knowledge

on the results of treatment methods was also mentioned as a problem.

The pessimism about treatment results for heroin abusers was

unjustified, according to the minister, who referred to American

research (Ibid. 73).

It is striking that no particular international developments were

discussed in the bill, the Riksdag, and the standing committee on Social

Affairs (SoU 1977/78: 36). The Netherlands was not mentioned as a

problem.

The bill passed the Riksdag but not without voting on reservations

from social democratic MPs and motions of the Communist Party (Ibid.

80).

New guidelines

In 1977, complaints from police officers in the Stockholm region

reached the local prosecutors. Experiences had shown that the generous

practice of dismissal of prosecution stood in the way of actions against

street-level dealing. Dealers simply did not carry with them drugs for

more than a week's use, and police officers experienced actions against

drug dealing as meaningless. The prosecutors in Stockholm were

receptive to the complaints and decided that possession of heroin and

cocaine should be excluded from the possibility of dismissing

prosecution (Solarz 1987: 93).

In 1980, the national guidelines were reviewed. Dismissal of

prosecution should moreover only be used for quantities of one smoke

of cannabis (0.751 g) or one dose of central stimulants (0.10.2 g),

(cocaine excluded). When in doubt about the quantity, prosecution was

recommended. Furthermore, dismissal should be restricted to first-time

offenders. The Prosecutor-General pointed out that the adjustment of

guidelines this time was not caused by new legislation. Apart from

developments in the field of legislation, the prosecutors also had to

keep themselves informed on developments in medicines and social

conditions (RÅC I: 94). Up till then, a basic standpoint for prosecution

had been to prioritise actions against professional illegal trade and

distribution of drugs. Now the Prosecutor-General stated that also

actions against illegal retail sale were important. By actions on this

level, trade would become more risky and less profitable for those that

benefit from organised crime, which in turn would diminish interests in

further distribution. Moreover, it would lead to greater difficulties in

getting access to drugs, which in its turn facilitated rehabilitation of the

addict, and decreased the risks of disseminating drug abuse. However,

combating small-scale dealing was not enough. It would be necessary to

interfere on the level of abusers as well by taking measures against

possession of drugs.

The guidelines contained a reconsideration of the harm caused by

cannabis. New scientific documentation of the damage done by

cannabis contradicted opinions that cannabis was harmless. For

example, continued use could trigger psychosis and cause changes in

the personality. Another reason was that the use of cannabis had spread

to socially established persons. This development could partly be

counteracted by a more restrictive policy on dismissals and a fine could

have individual and general preventive effects for this category (Ibid.

7).

Compulsory care

When the State Committee on Social Welfare published an interim

report with principles for a new Social Welfare Act, compulsory care of

abusers was part of the new organisation of social services (SOU 1974:

39). However, the committee was divided on this point and in the

referral round, many organisations were critical as well. They perceived

the proposal as a preservation of the Temperance Act. The criticism

came from a new generation of social workers that believed that social

work should be based on voluntariness and assisting clients, not

controlling or suppressing them. Critical voices could also be heard

from politicians from left-wing parties. They denoted the act as a law

aimed at fostering the working class (Holgersson 1988: 253).

In February 1975, the Minister of Social Affairs, Aspling, instructed

the committee to investigate the possibilities for compulsory care of

substance abusers (drug and alcohol abusers) outside the realm of social

welfare. However, when the non-socialist government came into office

in autumn 1976 the Minister of Social Affairs, Gustavsson, instructed

the committee to investigate the former proposal on compulsory care

within social welfare as well (Ibid. 266). This created a situation in

which the committee had to consider two directives simultaneously.

In 1977, the State Committee on Social Welfare published its final

report (SOU 1977: 40). The committee proposed a new Social Welfare

Act in which the goals and obligations of municipal social service were

outlined. Compulsory care of adult drug and alcohol abusers was not

part of the act. However also this time the committee was divided on

this subject. A (conservative) minority supported the directive from

Minister Gustavsson. A committee of officials was appointed to work

out a compromise. The next year the committee proposed that a special

provision would be added to the LSPV act that enabled compulsory

care of substance abusers in a mental hospital for a maximum period of

four weeks in situations of emergency (Ds S 1978: 8). In the bill for the

Social Welfare Act, compulsory care of adult abusers was also

proposed to be a matter for psychiatry. Those who were dependent on

alcohol or drugs and in need of detoxification and other psychiatric care

related to dependency could be admitted compulsorily if absence of

care implied serious danger to their health or life or someone else's

personal security or health (Prop. 1979/80:1). However, this was not the

end of the story. In June 1980, the Riksdag approved a new Social

Welfare Act but without a law on compulsory care on which there was

still was large disagreement. The Minister of Social Affairs appointed a

working group to review the issue of compulsory care on the basis of

discussion in the Riksdag on this matter. In January the next year the

working group delivered a draft for an "Act on the Care of Adult

Abusers in Certain Cases" (LVM). The bill passed the parliament in

December and came into force in 1981. The LVM Act (SFS 1981:

1243) enabled compulsory care of adult abusers of alcohol and drug

abusers for a period of two months with a possible prolongation of

another two months. The decision to prolong compulsory care was to be

taken be the social services not the court. Furthermore, responsibility

for compulsory care was allocated to counties and municipalities. The

main difference from the Temperance Act is that the LVM Act

primarily aims at improving abusers' condition and increasing their

motivation for voluntary treatment. In other words, while the

Temperance Act primarily was to protect society, in the LVM Act the

condition of abusers was in focus.

New threats

The next governmental drug policy bill came in February 1982 and was

called "Actions against Alcohol and Drug Abuse" (Prop. 1981/82:143).

Besides the fact that alcohol and drugs were discussed in one single bill,

another striking fact is that very little attention was paid to assistance.

Control measures and information seemed to be more important.

In the bill, the situation concerning drug abuse was depicted in detail.

The case-finding study that started in 1977 and was published in 1980

was referred to. For the first time, prevalence of severe drug abuse

could be discussed based on a study.

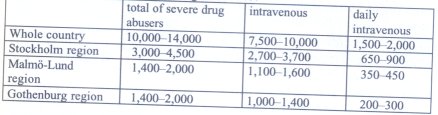

Table 1: Severe drug abuse in the big cities 1979.80

Opiate abusers, including heroin, comprised half of the category daily

(7501000) and 30% (25003300) of all intravenous drug abuse.

Further, a high number of multiple drug users were reported (Ds S

1980: 5: 92).

According to the BRÅ Narcotics Group, access to drugs had

increased slightly since 1979. Other data on developments in the drug

market came from police sources. The number of seizures had increased

sharply from 3359 in 1978 to 6992 in 1981. According to the minister,

the increase could be explained by increased policing against street-

level dealing and the changed guidelines for prosecutors in 1980.

However, custom had not changed its practice and recorded an increase

in seizures, which indicated increased availability of drugs in the

country, especially of amphetamines and heroin, and according the

police cocaine also was for sale in the streets (Prop. 1981/82: 143: 6).81

Furthermore, severe drug abuse was not confined to big city regions

any longer but manifest throughout the country. The drug problem was

described as a serious social and medical problem whose character had

recently become more serious. However, this development was similar

to that in most countries where drug abuse had become a threat to social

welfare (Ibid. 20).

Cannabis

Abuse of cannabis was substantial according to a report from the BRÅ

Narcotics Group (Ds S 1982: 1). However, annual surveys conducted

during the seventies showed a decline in lifetime prevalence among

youth (aged 15/16) that experimented with drugs, mainly cannabis. The

latest survey in 1981, however, showed a slight increase from 8 to 9%.

However, according to a household survey (age 1224), lifetime

prevalence of cannabis use had increased during the same period, from

9% in 1971 to 15% in 1980 (Ibid. 9). In spite of the fact that this was a

minor increase and opinions were divided on how to interpret the

surveys, the minister stated that a new wave of cannabis smoking had

started around 1979, as in other Western countries (Rd 1982 no. 153:

155). The image of a new wave of cannabis was also conveyed by a

report from the inquiry on the extent of drug abuse (UNO) (Ds S

1981:11). The overall conclusion by the UNO was that the drug

situation among young people had not worsened during the 1970s (Ibid.

79). The question is then: which data supported the assertions that a

new wave of cannabis was on its way? Part of the UNO inquiry was a

qualitative study among 19 youngsters (1216 years) from different

social backgrounds. Especially worrying was the use of cannabis

among upper-class youth that did not use cannabis to escape from

problems but as a symbol of freedom. Often they had learned to smoke

marijuana during visits to the US. Youth in this social category would

presumably not encounter serious problems when they wanted to quit

abuse of cannabis. However, it was a well-known fact that new patterns

of abuse usually start in upper-class groups and then disseminate to

groups with different social backgrounds. Youngsters with less

favourable conditions often have less potential to end abuse (Ibid. 50).

This line of reasoning is strikingly similar to the conclusions by the

Baan Committee some ten years previously; however, countermeasures

were of a completely different character.

It is likely that the government referred to the UNO report when it

stated that:

Abuse of cannabis has disseminated to groups that traditionally are not regarded as

categories of abusers. Among them, a tolerant attitude towards cannabis abuse

prevails. The drug is part of their lifestyle and they defend its abuse with false

assertions that it does not entail any social or medical harm. This message has also

been mediated by parts of the commercial culture. Behind this message are

economic forces that are risking the social and economic well-being and health of

the people for their own gain (Prop. 1981/82:143: 42).

This statement shows some new aspects of the drug problem. Cannabis

was used in other groups than the traditional, already deviant youth.

These new users were not aware of or ignored the basic facts about

cannabis-related harm. Furthermore, the dark forces were not just the

big dealers but also parts of commercial culture.82 Information that

aimed at changing people's attitude was considered an important and

effectual instrument to counteract this development. However, a

precondition for the efficiency of information was that society acted

consistently so that concord would be achieved between the message

and the actions (Ibid. 43).

Controlling the streets

During 1981, the police increased actions against street-level dealing.

Nationwide actions against drug criminality and in particular against

street-level dealers were pursued in autumn 1981 and spring 1982.

Round-ups of apartments and other places where drug abusers and

dealers hung out were parts of the action. Special attention was paid to

drug problems in schools and police officers were active in providing

information on drugs in schools and organisations (Prop. 1981/82: 143:

23). In the standing committee on justice, a motion was tabled

demanding a criminalisation of use of drugs. The committee held the

view that there was reason to change the Drug Act in this respect (JuU

1981/82: 47).

In July 1982, some changes in the Drug Act came into force. The

maximum penalty for simple drug offences was increased from two to

three years' imprisonment. The minimum penalty for serious drug

crime was increased from one to two years' imprisonment. A novelty

was the motivation for changing the Drug Act; it was aimed at

accentuating society's repudiation of drug abuse (Hoflund 1987: 26).

While previous provisions of the Drug Act sought to combat certain

aspects of the trade in drugs, from this period on, law provisions would

also be a symbol that conveyed a message to the population.

Assistance

The establishment of treatment homes was still a weak link in the

"chain of care". In spite of generous state subsidies for establishing and

running treatment homes, the speed of opening new homes was still

disappointing. In July 1981, the number of beds in state-subsidised

homes was 352, with an additional number of 100 beds that were

funded in other ways. The reasons for this slow pace, according to the

minister, could be found in administrative and practical difficulties in

starting a treatment home.

Concerning ambulatory care, the number of specialised centres for

drug abusers was 26 in January 1982. The major activities of these

centres were outreach work, different kinds of treatment and aftercare.

Detoxification and motivational work was done at special wards of

psychiatric hospitals (200 beds). An experiment with conditional

treatment instead of imprisonment had started in 1979 and would be

evaluated (Prop. 1981/82:143: 16).

Opinion formation

Information on drugs to the public followed the path set out by the SBN

in 1969, i.e. producing basic facts by central state authorities. In 1977

"Facts on Drugs and Drug Abusers", approved by the BRÅ Narcotics

Group, was published by the National Board of Health and Welfare. In

1980, the Ministry of Social Affairs and the BRÅ Narcotics Group

published a brochure "Facts on Hash and Marijuana". The brochure was

produced because of the worrying developments concerning cannabis

abuse and sent to all pupils aged 1319 (800,000 copies).83 A

complementary guide to teachers was distributed in 70,000 copies. In

spring 1981, two television programmes on the subject of hash were

broadcast and a leaflet printed. The RFHL started a nationwide action

called "Strike Back against Hash". In 1979 a committee for opinion

moulding against the drug culture was installed by the government

(SoU 1981/82:43). In 1981 a nationwide campaign against alcohol was

launched by the Ministry of Social Affairs and carried out by authorities

and organisations. In 1982, a similar action against drugs was pursued.

The target groups were youth and their parents (Prop. 1981/82:143: 8).

A novelty in the 1982 bill concerns the role of information. A new

concept was introduced, "opinion formation". Information was no

longer aimed at warning the people against the dangers of drugs (and

alcohol) or obtaining support for the government's struggle against

drugs. It also aimed at creating opinion against drug abuse (and

alcohol). Opinion against drugs had become a weapon in the struggle

against drugs, and cannabis was the main target.

Drug culture

Another new feature in policy documents was the introduction of the

concept of "drug culture". Information on drugs and influencing

attitudes would militate against the drug culture. What is this drug

culture? The Minister of Social Affairs had suggested that commercial

interests lay behind. The Minister of Education stated that many

youngsters had difficulties in defending themselves against the special

"youth culture" that was often associated with a naively positive

attitude to alcohol and drugs (Rd 1982, no. 153: 119). By information

on drug-related harm and by influencing norms, schools could make

pupils take a stand against the glorification of drugs.

In the plenary debate on the bill in May 1982, the Minister of Social

Affairs expressed her satisfaction with the national actions. The goal for

actions was to initiate a debate and to make young people reject drugs

(and alcohol). Actions had been fruitful so far. Thanks to the assistance

of almost all organisations in Sweden, meetings with parents had been

organised throughout the country. Young people demonstrated against

drug dealing (and alcohol dealing). Drug-free rock concerts, music, and

dance parties have been a great success in many places. Several MPs

also concluded that a new attitude was growing among the people, for

example, among parents concerning the purchase of alcoholic

beverages for their children (Ibid. 153).84

The Riksdag also discussed the cannabis-glorifying youth culture.

Sigurdsen (s) (Minister of Social Affairs in the next Social Democratic

government) was rather specific in defining the drug culture:

Pop music glorifies hash, and the culture that follows in its track is characterised by

the hallucinatory effects caused by the drug. We just can look at the covers of

albums in record shops. I think one can say that the drug-arousing community

develops its own culture (Ibid. 181).

Sigurdsen was also afraid that if the dimension of what was going on

remained undisclosed, a generation would run the risk of going under. It

was a shame to a rich welfare society that drugs had achieved such a

strong foothold. No more investigations were needed, but actions. An

alternative had to be created to the drug culture. At the same time,

Sigurdsen had declared in a newspaper article that she and the party

now had dissociated themselves from the former "blather" of drug

liberalism (Svenska Dagbladet 29 October 1982). A MP from the

Conservative Party supported her. He too pointed out the covers of

records as the source of drug-inspired lifestyles. According to him

freedom of speech would be respected but:

We can in each and every context and we shall do that forcefully point out

individuals and groups that have drugs as part of their message. In that case, they

will constantly be pushed into a position of defence that will become increasingly

intolerable. We must stop the "blather" culture (Ibid. 185).

The term "blather" (flum in Swedish) deserves a brief comment. In the

Swedish context of the drug problem "blather" usually denotes

opinions, people, a phenomenon or culture that do not express a firm

attitude against drugs. It is often used as a synonym of another

pejorative, "drug liberal".

75 The Netherlands was not the only country that did not sign. It was not until 1976

that the required number of signatories (40) was reached and the Convention came

into force.

76 In October 1976, after 44 years of Social Democratic governments, a non-

socialist coalition came into office.

77 Five members had also been members of the SBN in 1968. This time a reference

group of MPs informed the parliament about the Leading Group's activities.

78 Family care means that socially stable families take care of one or more

youngsters as an extra member of the family with financial compensation from the

social services.

79 For alcohol policy, the overall goal was to limit total consumption.

80 Data were obtained from authorities and registers. The definition of severe abuse

was all intravenous abuse, regardless of the frequency, and all daily or almost daily

abuse, regardless of the mode of intake (Ds S 1980:5).

81 The increase of amphetamines was explained by a reorganisation of Dutch crime

syndicates and increased domestic manufacture (Prop. 1981/82: 143: 6).

82 In the UNO report, musicals like Hair and Quadrophenia and rock concerts were

mentioned as examples.

83 The brochure was translated into seven immigrant languages.

84 The minimum age in Sweden to buy beverages in the state System Company is 20.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|