Report 3 A process for constructing a global estimate of the burden of illicit drug use

| Reports - A Report on Global Illicit Drugs Markets 1998-2007 |

Drug Abuse

3 A process for constructing a global estimate of the burden of illicit drug use

The complexities involved in constructing a comprehensive national estimate of the cost of drug use are significant and efforts to construct them are nontrivial. Each of the previous studies represents a substantial amount of effort with numerous incremental decisions that needed to be made in order to facilitate their construction. While many of the decisions are grounded in science, some are simply pragmatic and are a function of the environment in which they are being constructed (e.g., data only exist to measure certain aspects of the problem or behaviour; or no cost data exist for estimating the cost of particular outcomes so they are excluded). These sorts of complexities and details are important when trying to make comparisons of the relative burden of illicit drug use across countries from existing estimates. They also demonstrate why it is unwise to try to consider the global burden of the problem by simply aggregating results from different studies. There are just too many important caveats, assumptions, definitional inconsistencies, and costing differences for such an aggregation to be truly meaningful.

In this chapter, we lay the ground work for thinking about how to construct a global estimate of the burden of drug use that is mindful of the issues just discussed. It is important to realize that any estimate of the global burden of drug use must be far less comprehensive than national estimates in terms of cost elements considered. This is not because the omitted costs do not matter on a global scale. Rather, it is more a function of the fact that some costs cannot be consistently measured across all countries. This may be due to differences in social and political environments that give rise to particular costs, which vary across countries independent of drug use, or it may be due to inconsistency in the measurement of the problem or the unit cost of the outcome. The goal here is to describe an approach that focuses on a fairly narrow set of key elements that are almost universal across countries. When these elements are measured consistently across countries, they can be used as a means for comparing the relative burden of the drug problem across countries, at least with respect to these common core elements. Not all countries currently collect each of these elements, however, so it still is not possible to provide a full global estimate based even on this narrower conceptualization of the problem. The utility of such an approach can still be demonstrated for those countries providing information on these elements.

It is important to begin with a definition of drug use that can be meaningfully and consistently applied across the various countries and result in accurate measurement of the same behaviour. Although regular, dependent or problematic users are more likely to impose harm on themselves and others compared to recreational users, it is far more difficult to obtain consistent indicators of dependent, heavy, or problematic drug use across all countries. Indeed, recent efforts by the EMCDDA to obtain consistent measures of problematic drug use in each of the European Member States resulted in only 15 out of 27 member states reporting a measure of problematic drug use in 2007 (EMCDDA, 2008b). Given the problem of inconsistent measurement, therefore, this report focuses on measuring harms for any recent use of an illicit drug, as indicated through past year prevalence. A major limitation of using this measure, of course, is that it is impossible to construct an estimate of the cost per dependent or problem user, as done by Godfrey et al. (2002) for England and Wales. Furthermore, by using a simple measure of prevalence of any drug use, it is not possible to decompose costs by substance used. These represent real limitations to bear in mind when examining the results presented from studies using the same prevalence-type measure.

The general approach is to identify the health, productivity, and crime indicators that can be consistently tracked across a large number of countries. The specific health indicators should focus on those that are clearly attributable to drug use (need for drug treatment, drug-related mortality, overdoses) and those for which significant attention has been given by the international community, particularly the World Health Organization and UNODC (e.g. HIV/AIDS, Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C). Although such an approach would not represent the full range of probable drug-attributable morbidity (e.g., drug-related driving deaths), it is clear from the national studies previously reviewed that there remains significant debate regarding the health harms that should be considered as well as the presumed attributable fraction of specific diseases (e.g. Collins & Lapsley, 2008; Popova et al., 2007). Thus, by focusing on a small set of core indicators for which there is relatively good measurement consistently across countries and for which there is general agreement regarding the extent to which drugs contribute, it reduces the effort and focuses energy on indicators that are likely to be widely agreed upon trans-nationally.4

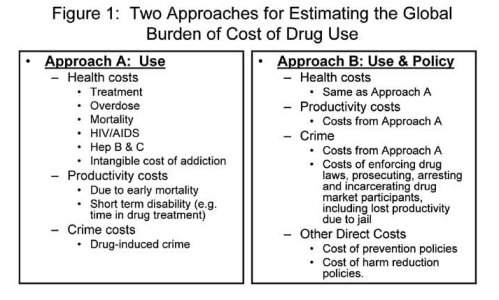

Figure 1 provides a basic conceptual framework for an approach that is mindful of the different social contexts and political responses that raise the cost of drug use when considering the burden of disease internationally. Two estimates of the economic cost of drug use should be constructed, rather than one. The first, which is referred to as Approach A, focuses more narrowly on costs that the scientific literature reasonably supports are incurred as a function of drug use itself. It largely reflects costs associated with drug treatment, poor health outcomes due to drug use, and lost productivity. It also includes the intangible health burden associated with drug addiction.5 The second approach (labelled Approach B) adds to the first estimate the additional cost of society’s response to the drug problem, in particular criminal justice costs, harm reduction and prevention policy responses. The reason for adding these costs in incrementally is so that the consumers of these numbers, in particular policy makers, can see the extent to which the economic burden is driven by consumption or society’s response to that consumption.

Although drug treatment could clearly be considered a policy response rather than strictly a medical issue in many countries, we include drug treatment in Approach A rather than Approach B because it is unclear in many countries the extent to which drug treatment is a medical response (done because of a perceived medical need) rather than a policy response (done to change individual behaviour). Countries differ in terms of the fraction of drug treatment paid for by private payers versus public funders and the extent to which addiction is viewed as a health problem (and thus covered through regular health insurance) versus a behavioural or social problem. National statistics rarely differentiate treatment episodes in terms of who pays (private insurance, private charity/foundations or government). Indeed, even in Europe, the EMCDDA does not require member nations to report information regarding the fraction of all drug treatment paid for by the public sector. Given the inability to distinguish the extent to which drug treatment represents a policy response versus a medical response, it is included conceptually as part of Approach A.

Approach B provides an interesting point of comparison vis-à-vis estimates obtained using Approach A for both within-country assessments (in terms of the relative emphasis on responding to drug use versus the burden of that use itself) as well as across countries assessments (in terms of the relative magnitude of the costs of society’s response versus the cost associated with use). 6 Of course, no informed interpretation of these numbers can be made without additional information regarding the relative effectiveness of particular policies. Indeed, if a particular policy approach is truly effective, then it is possible that the cost of implementing it exceeds the cost of users who are undeterred by it in some cases. Thus, just because a policy approach is more expensive than consumption, per se, does not mean that the policy should not be pursued. Further, because it is impossible to know the extent to which treatment represents a medical response versus a policy response and treatment represents a major fraction of some country’s total policy response, interpretations of these comparisons should only be made cautiously.

Figure 1 clearly represents a simplification of the drug problem and the costs associated with it. Several relevant and important aspects of drug-related harm captured in existing national studies are clearly omitted. The focus on these indicators, however, is due to the fact that they are the main cost elements considered consistently in previous national studies, as indicated by Table 2. They therefore represent the most plausible starting point for conducting a systematic assessment of costs for multiple countries.

4 Of course, a major health area that is currently excluded from this framework is mental health. The literature examining the relationship between illicit drug use and particular mental health problems is still developing. As shown in Table 1.2, some national studies have included costs for specific mental health problems, but there is far from a consistent standard. Given the uncertainty regarding attributable fractions in the literature, the inconsistency in measurement of the problem in existing problems, and the lack of national data regarding the incidence of these problems for most countries, mental health costs are not being considered at this time.

5 Recent work demonstrates that the intangible cost of living with addiction represents a substantial share of the total burden of the disease

(Collins & Lapsley, 2008; Nicosia et al., 2009). Other intangible costs also exist, such as family burden and the societal burden of living with diseases that are spread through drug use, but we are not aware of any international efforts to systematically consider the quantification of these costs. However, in the case of the burden of disease, significant work has occurred internationally attempting to quantify the value of a lost quality of life or disability burden of addiction as well as other diseases (King et al., 2005; Zaric et al., 2000; Barnett & Hui, 2000; Hirth et al., 2000).

6 Note that if a policy has an effect, then the total cost estimated using Approach A would reflect the effect of the policy through lower estimates of consuming related harms. This does not make the suggested comparison uninteresting but demonstrates the need to be cautious interpreting results regarding the relative differences in cost of policy versus cost of consumption.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|