Report 3 Review of national studies of the cost of drug abuse

| Reports - A Report on Global Illicit Drugs Markets 1998-2007 |

Drug Abuse

2 Review of national studies of the cost of drug abuse

Given the need of policy makers to better understand the importance of substance abuse vis-à-vis other societal issues, several Western nations have funded research examining the economic burden of alcohol, tobacco and illicit drugs within their own borders. From early studies it can be seen that political and social environments influence not only the types of harms considered but also the factors that influence these harms, including the availability of particular drugs, the likelihood that substances get used, and the probability that harm comes from either immediate or long term use of the substance. Thus, the concept of societal costs of drug use must be considered within the context of the country in which those harms are being considered. That being said, there are certain harms that can be uniformly observed across countries, such as development of dependence, the spread of HIV or hepatitis through needle sharing among injection drug users, and lost productivity associated with premature death. Similarly, there are in many cases common responses by countries, such as the delivery of treatment to those in need of it or the attempted suppression of supply through the incarceration of dealers and traffickers. Thus, there remain common elements that exist across countries that can be compared, but it requires consistency in the measurement of these indicators and in the unit costs applied to each.

The significant differences in indicators and costing strategies adopted in early national reports precluded comparisons of the drug problem across countries even when similar elements of the problem were being compared. In response, a series of symposia and workshops were held in Canada and the United States between 1994 and 2002 involving international experts engaged in these activities in various developed countries. From these meetings, international guidelines for estimating the cost of substance abuse (alcohol, tobacco and illicit drugs) were published by the World Health Organization (Single et al., 2003) recommending a unified methodological approach across all studies.

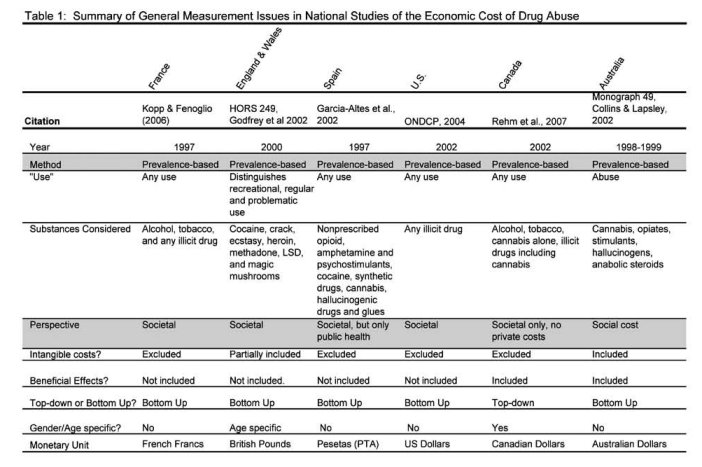

Even with the development of these international guidelines, recent national studies of the economic burden of drug abuse remain disparate in important ways that preclude the direct comparison of their results. However, the guidelines were never intended to instruct authors on how to construct estimates for the purposes of international comparisons; instead they were offered as a way of harmonizing the general methodological approach. Table 1 provides a summary of key measurement issues related to the construction of recent national estimates from seven different countries (France, England and Wales, Spain, the United States, Canada, and Australia).1 As can be seen by the shading in Table 1, there are only two broadly consistent methodological elements across all seven studies, but these are important. First, all studies adopt a prevalence-based approach, which considers the current calendar year costs associated with individuals using drugs in that year, ignoring the future costs (or savings) associated with drug use as those current users age. The prevalence-based approach, therefore, assumes that the distribution of use and harms associated with use over the life course is stable and can be predicted from the distribution of users and harms observed among current users at different ages in the current calendar year. Second, all the studies consider costs imposed on society, not just the costs borne by users or the payer of health services.

However, even with respect to this dimension, the studies are not entirely consistent, as the notion of “societal” differs across studies. In particular, the Canadian study only includes costs imposed on others and does not consider the private costs (i.e. the costs borne only by the individual user) associated with drug abuse. In all the other studies, the term “societal” is used to refer to both the private and public costs associated with use. Another nuance is the breadth to which societal costs are examined. In the Spanish study, only the costs to the public health system are considered, whereas most of the other studies also consider the social costs impacting the criminal justice and welfare systems.

The similarities in methodological approaches across the studies end with these two dimensions. The aspects in which these studies differ are important for demonstrating why comparisons across countries are unwise when using information from existing national studies. As summarized in Table 1, there are important differences in either the definition of substance use (any use, abuse or regular use), the substances included (any illicit drug versus a set of particular drugs), the method to assess costs (bottom-up versus top-down, separately by gender and age group), and in the specific costs included (cost offsets from positive effects of use, inclusion of intangible costs).

In terms of the definition of use, most studies consider the costs of any use of the substance, but the Australian study examines only the cost of abuse, while the England and Wales study distinguishes costs associated with recreational (any) use, regular use, and problematic use. The distinction in type of use can have important implications for which costs or problems get included. For example, a recreational user in the United States and France can still be arrested for simple possession, which would be included in the total cost of drug use for these countries if any drug use was considered but would not be included if only problematic or dependent use was considered. Even more important is the fact that the substances considered across the studies are not the same. The focus on different substances across studies may reflect differences in the substance of abuse in these countries, the perceived harms of particular drugs, or the availability of data on particular substances abused. For example, in the case of the Godfrey et al.’s (2002) study of England and Wales, cannabis is not scheduled as a Class A drug, and hence is omitted from the study which focused exclusively on Class A drugs. However, cannabis remains the most widely used illicit substances in England (Reuter & Stevens, 2007). Comparing the total costs from Godfrey et al.’s (2002) study to that of Spain or Australia would be misleading given that different substances are represented and a key substance of abuse (cannabis) is missing by construction from the Godfrey et al. (2002) report.

Intangible costs refer to the emotional and physical burden placed on individuals because of drug-induced problems (addiction, premature mortality, or fear of crime and victimization). In some cases these intangible costs are borne by the drug user himself (when dealing with the emotional and physical burden of being addicted) and in some cases these costs are borne by others (those left behind when a drug user dies, those living in drug-infested neighbourhoods). Although widely recognized as a significant aspect of the total burden of drug abuse, only the most recent studies have attempted to quantify these losses (Godfrey et al., 2002, 2004; Rehm et al., 2007; Collins & Lapsley, 2002, 2008). The typical reason for their exclusion is the difficulty in placing a monetary value on these very personal measures of pain and suffering. There is substantial debate in the literature regarding how best to do this (see e.g., Hirth et al., 2000; Viscusi & Aldy, 2003; Aldy & Viscusi, 2008). Nonetheless, as indicated by those studies that have attempted to include them, they represent a considerable portion of the total burden of the disease. For example, Collins & Lapsley (2008), which updates their 2002 study mentioned in Table 1 and provides greater focus on drug-attributable crime, estimate that the intangible cost of all substance abuse represent 45% of the total economic cost in Australia (for 2004/2005).2 Similarly, the extent to which the beneficial effects of substance use are considered when estimating the economic burden of these diseases is fairly mixed. Although the beneficial effects of moderate alcohol consumption is now widely recognized, the potential positive effects of cannabis for medicinal purposes are not generally considered in many cost of illness studies focused on illicit substances. Very few studies acknowledge the fact that most people initiate consumption of these substances because they seek the positive effects they offer (e.g. relaxation or pleasure).

The methods for assigning costs to specific indicators vary across studies as well. Although most of the recent national studies apply a bottom-up costing strategy, where specific health, treatment, crime, and productivity costs are given a unit cost estimate based on prevailing market rates, it has generally been more common in the previous literature to use a top-down approach for assigning costs. The top-down approach uses budget information from government authorities to construct a unit-cost estimate by diving the total budget for a given cost area (e.g. drug treatment) and dividing it by the number of patients served to get a cost per patient. The advantage of such an approach is that it directly considers the additional administrative and overhead costs associated with a variety of government activities. The disadvantage of that approach is that it is often extremely difficult in aggregate budgets to isolate costs that are strictly due to illicit drug use (versus alcohol use, tobacco use, or some other related problem).3 Hence the unit cost estimates constructed from a top-down approach might not reflect the actual average cost for the drug users specifically. Moreover, if drug users require extra (fewer) resources than others pooled into that government budget, a top-down approach might underestimate (overestimate) the actual cost imposed by drug users. Related to these issues are differential costs due to gender and age. Assigning a value for premature mortality using the human capital approach (the approach most commonly employed in these studies) can be very different depending on the typical age and gender of the person who died from drug use (Viscusi & Aldy, 2003). Similarly the cost of treating a particular health problem could differ based on the age of the individual being treated (young versus old) or the timing of when it is detected (early identification of Hep C or HIV). Some studies apply gender and/or age-specific costing units for the outcomes considered in the study, while others apply simple averages for the population being served or evaluated. These sorts of differences can have important implications in terms of the total costs calculated for the same exact outcomes because drug-problems disproportionately affect certain segments of the population across countries (e.g. youth and young adults).

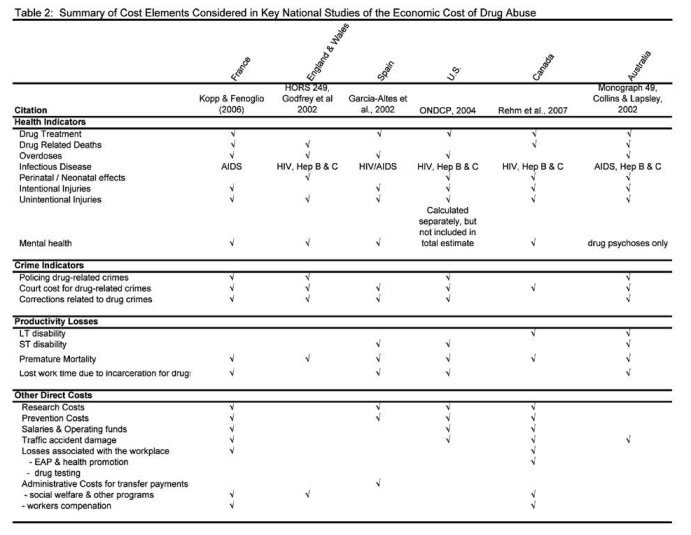

In addition to the general differences in methodological approaches described above, there are a number of relevant differences in the specific costs considered across the seven more recent national studies. Table 2 provides a brief overview of the key cost elements considered in the seven national studies previously discussed. To some extent the differences in indicators considered partially reflect availability of data, in some cases they represent an alternative conceptualization of the problem (e.g., productivity losses associated with long term disability due to drug use), and in other cases they represent differences in the social and political structures involved in responding to the drug problem (salaries and operating funds, employee assistance programs and health promotion). What is particularly salient here, however, is that differences exist even in categories that would otherwise seem similar. The specific example highlighted in this table is that of drug-related infectious diseases. Kopp & Fenoglio (2006) only consider the cost of drug-related AIDS, while Garcia-Altes et al. (2002) consider the cost of drug-related HIV infection as well as AIDS and Godfrey et al. (2002) consider the cost of HIV/AIDS, Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C. Given the different prevalence rates of each of these infectious diseases, not to mention their lifetime costs, very different cost amounts for “infectious diseases” could result based on alternative construction of the indicators included. The same could be said of the other categories broadly represented here, such as intentional injury, unintentional injury, and even premature mortality. In the case of premature mortality, the EMCDDA has developed a common definition that is uniformly applied in the Member States. According to the EMCDDA, drug-related deaths within the European Union refer to those deaths that are the direct result of drug consumption, such as overdose, poisoning, or drug-related suicides. But in the Australian studies, however, premature deaths due to drug use include deaths caused by drug- related diseases, such AIDS and Hepatitis C. So even within specific cost elements, considerable differences can exist in terms of the definition of behaviours being represented with a common label.

The fact that independent national studies differ along the dimensions just mentioned is in no way a statement that any particular study is better or worse in their construction of an estimate. Neither should these differences across studies diminish the significant contribution each study makes in terms of our general understanding of the drug problem within a particular nation’s borders.

Instead, the differences are merely reflective of the fact that nations differ in their reasons to be concerned about drug problems, the harms caused by drug use, and the availability of data to measure those harms and their costs. Even when guided by the same methodological principles (Single et al., 2003), important differences can still emerge that makes direct comparisons across nations difficult and unwise. If one is intending to take on the task of developing an estimate that can be directly compared to measures from other countries, then it is necessary to start from scratch and develop a common conceptualization of the problem that can be consistently measured and monetized in all the relevant countries. Then the very difficult work of harmonizing those indicators across cultures and societies would have to begin.

1 National estimates of the cost of illicit drug use in Switzerland, Luxembourg, and Finland were referenced in the general literature we reviewed, but we were unable to obtain copies of the original studies which would enable their inclusion in this analysis. We do not believe their omission, however, influences the main findings of this chapter, which are that systematic differences exist in the methods used to estimate these costs and hence direct comparisons of these estimates to generate a global burden of disease is not possible.

2 When illicit drugs are examined by themselves, in absence of alcohol, the intangible costs represent a smaller but still sizable fraction of the total burden of illicit drugs (16%).

3 Moreover, such an approach obtains the average cost of an event, not the marginal, which in most instances is actually lower than the average cost of the event (given that marginal cost does not consider the fixed costs associated with having an enforcement structure, health care structure, or whatever in place).

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|