Appendix to report 4: country reports UNITED KINGDOM

| Reports - A Report on Global Illicit Drugs Markets 1998-2007 |

Drug Abuse

UNITED KINGDOM

1 General information

Location:

Western Europe, islands including the northern one-sixth of the island of Ireland between the North Atlantic Ocean and the North Sea, northwest of France

Area:

244,820 sq km

Land boundaries/coastline:

360 km / 12,429 km

Border countries:

Ireland 360 km

Population:

60,943,912 (July 2008 est.)

Age structure:

0-14 years: 16.9% (male 5,287,590/female 5,036,881)

15-64 years: 67.1% (male 20,698,645/female 20,185,040)

65 years and over: 16% (male 4,186,561/female 5,549,195) (2008 est.)

Administrative divisions:

England: 34 two-tier counties, 32 London boroughs and 1 City of London or Greater London, 36 metropolitan counties,

46 unitary authorities

Northern Ireland: 26 district council areas

Scotland: 32 unitary authorities

Wales: 22 unitary authorities

GDP (purchasing power parity):

$2.13 trillion (2007 est.)

GDP (official exchange rate):

$2.773 trillion (2007 est.)

GDP- per capita (PPP):

$35,000 (2007 est.) (CIA World Factbook)

Drug research

Governmental departments take the lead in funding, coordinating and conducting drug-related research but many universities also carry out drug-related research within relevant research institutes, centres and groups. In addition, a number of non-academic organisations undertake drug-related research when commissioned to do so. Funding is also available from research councils, foundations and trusts. The UK REITOX National Focal Point is based at the Department of Health, and works in collaboration with the John Moores University in Liverpool – maintains a listing of current research and recent publications including journal articles. An extensive number of scientific journals, websites dedicated to research and national drug conferences are the main channels for disseminating drug-related research findings. There are many drug researchers and different research groups at universities and in other institutions and organisations. Different agencies contribute to monitoring the drug problems and drug policy (Country overview).

Main drug-related problems

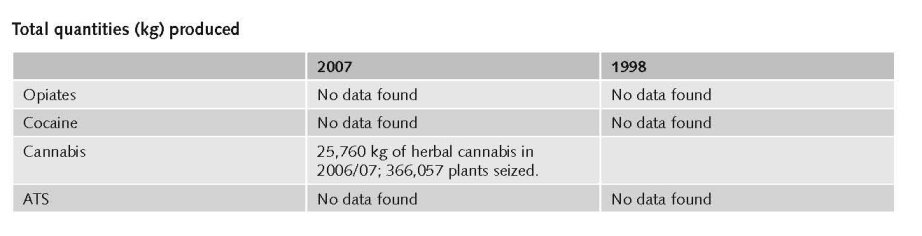

The main drug problem in UK is consumption followed by trafficking (mainly imported), Production plays a minor role although there is increasing domestic production of cannabis; in 2008 sinsemilla accounted for 81% of the UK cannabis market (expert’s comments).

2 Drug problems

2.1 Drug supply

2.1.1 Production

2.1.2 Trafficking

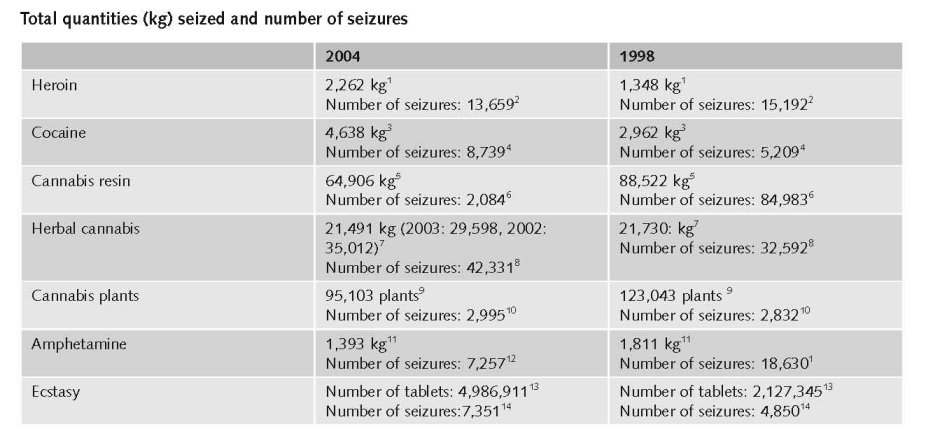

1. Quantities (kg) of heroin seized, 1995 to 2005, EMCDDA Table SZR-8-SEIZURE-HEROIN-QUANTITY.htm

2. Number of heroin seizures, 1995 to 2005, EMCDDA Table SZR-7-SEIZURE-HEROIN-NUMBER.htm

3. Quantities (kg) of cocaine seized, 1995 to 2005, EMCDDA Table SZR-10-SEIZURE-COCAINE-QUANTITY.htm

4. Number of cocaine seizures, 1995 to 2005, EMCDDA Table SZR-9-SEIZURE-COCAINE-NUMBER.htm

5. Quantities (kg) of cannabis resin seized, 1995 to 2005, EMCDDA Table SZR-2-CANNABIS-QUANTITY.htm

6. Number of Cannabis resin seizures, 1995 to 2005, EMCDDA Table SZR-1-SEIZURE-CANNABIS-NUMBER.htm

7. Quantities (kg) of herbal cannabis seized, 1995 to 2005, EMCDDA Table SZR-4-SEIZURE-HERBAL-CANNABIS-QUANTITY.htm

8. Number of herbal cannabis seizures, 1995 to 2005, EMCDDA Table SZR-3-SEIZURE-HERBAL-CANNABIS-NUMBER.htm

9. Quantities (number of plants) of cannabis plants seized, 1995 to 2005, EMCDDA Table SZR-6-SEIZURE-CANNABIS-PLANTS-QUANTITY.htm

10. Number of seizures of cannabis plants, 1995 to 2005, EMCDDA Table SZR-5-SEIZURE-CANNABIS-PLANTS-NUMBER.htm

11. Quantities (kg) of amphetamine seized, 1995 to 2005, EMCDDA Table SZR-12-SEIZURE-AMPHETAMINES-QUANTITY.htm

12. Number of amphetamine seizures, 1995 to 2005, EMCDDA Table SZR-11-SEIZURE-AMPHETAMINE-NUMBER.htm

13. Quantities (tablets) of ecstasy seized, 1995 to 2005, EMCDDA Table SZR-14-SEIZURE-XTC-QUANTITY.htm

14. Number of ecstasy seizures, 1995 to 2005, EMCDDA Table SZR-13-SEIZURE-XTC-NUMBER.htm

Additional information

Heroin from Afghanistan and the Golden Triangle enters the UK via Northern Cyprus and Turkey in freight vehicles. Trafficking of heroin also occurs via flights with a connection to Turkey and Pakistan. Cocaine from South and Central America, in particular Colombia, Peru and Bolivia, arrives in the UK mainly via Spain and the Netherlands, but also by air courier, either directly from South America or via the Caribbean. Morocco is the primary source of cannabis resin for the UK market. Main routes for transhipment are by road through the Iberian Peninsula, France and Belgium. In addition, there are indications of intensive hydroponic cultivation in the UK. Ecstasy and other synthetic drugs enter the UK from the Netherlands and Belgium, through ferryboats and the Channel Tunnel. However, some synthetic drugs are produced in the UK, including amphetamines (Country overview).

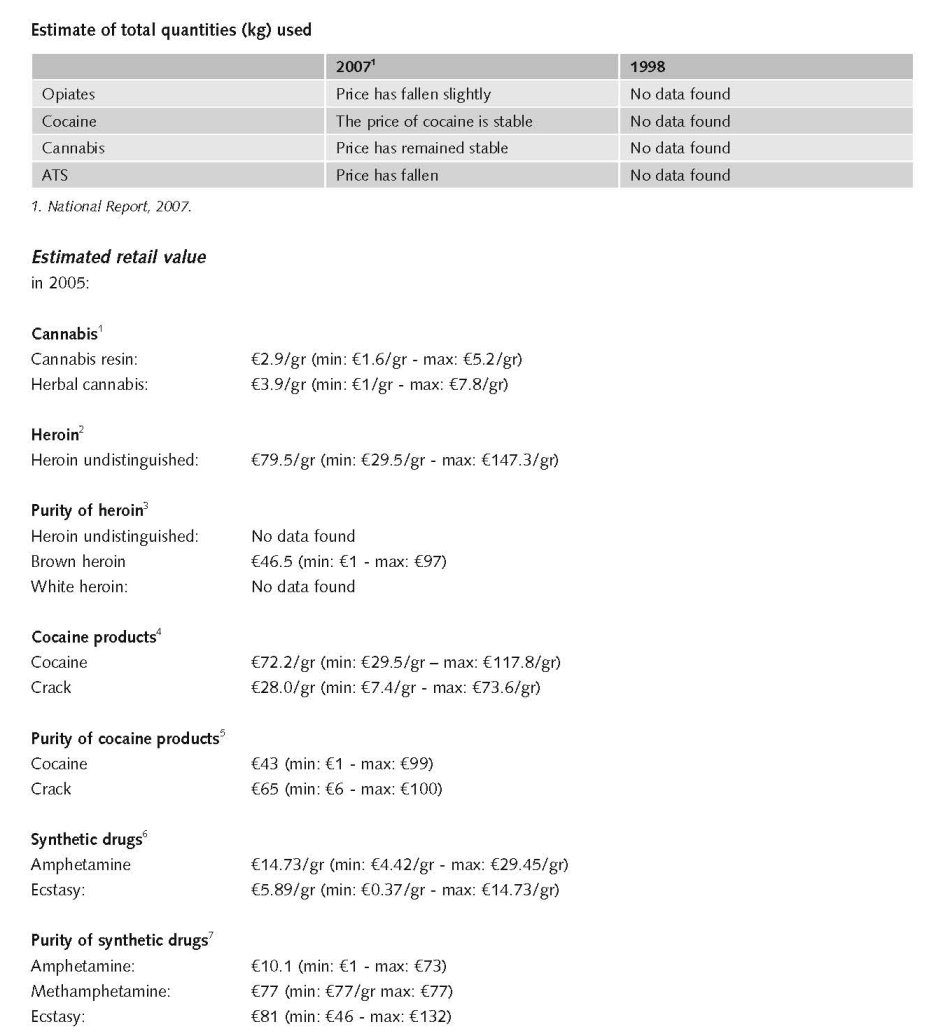

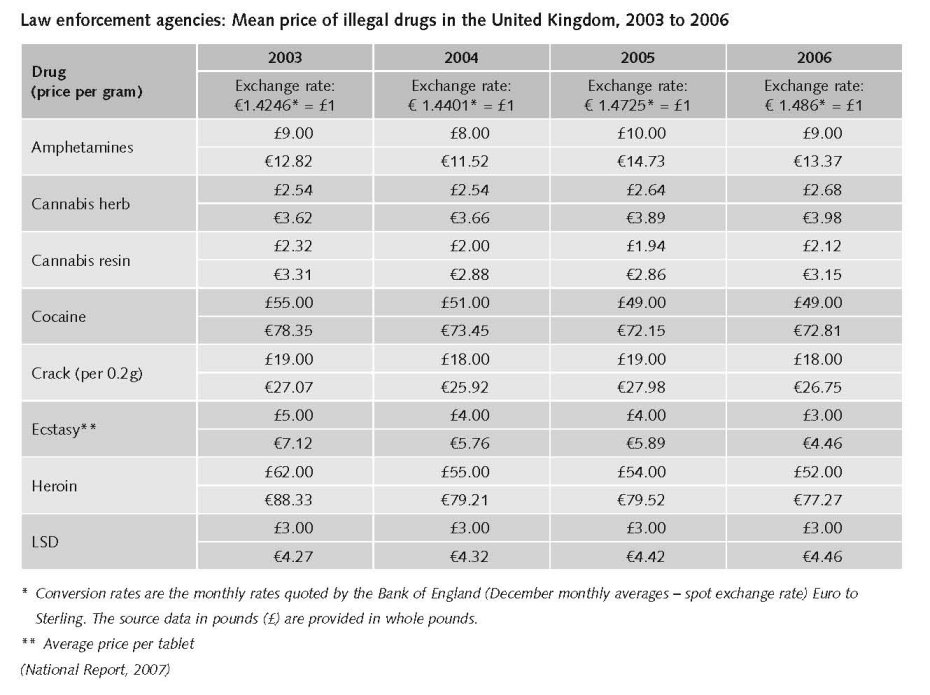

Estimated market value

A substantial fall of around 20 per cent in most drug prices over this four-year period, with a particularly striking price fall for ecstasy (Home Office, 2006).

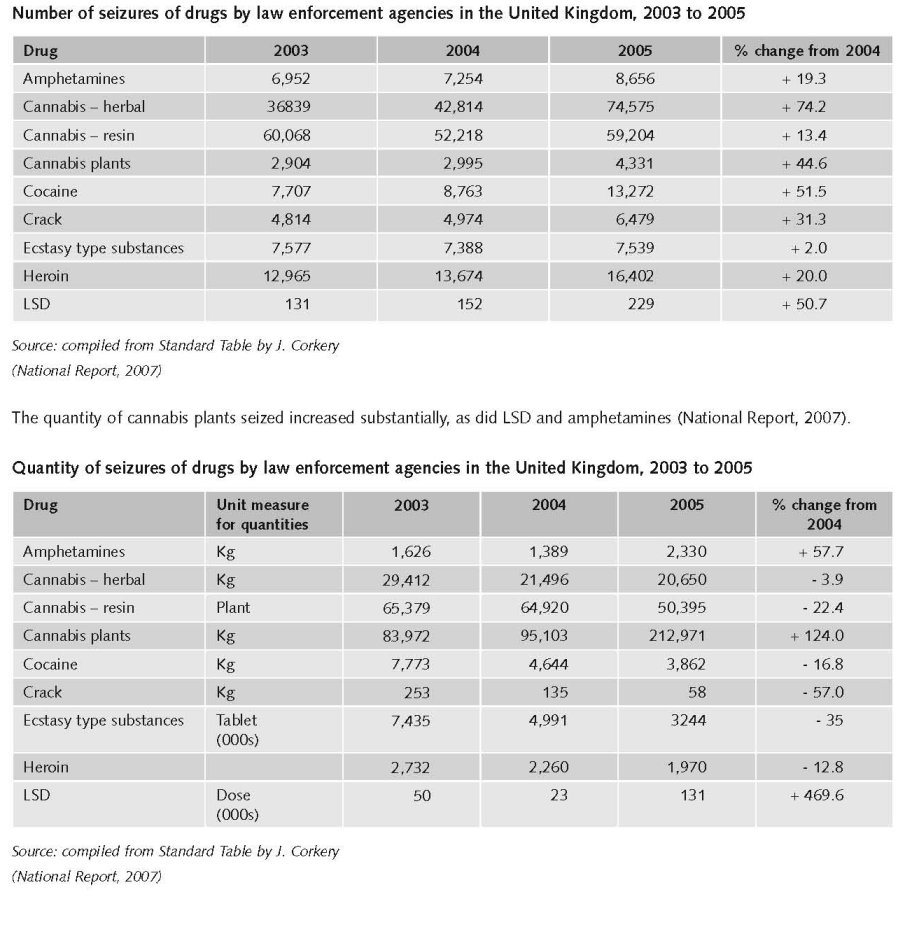

Seizures

In 2005 there were 189,032 seizures of drugs in the United Kingdom, a 42 per cent increase from the previous year. Increases are reported for all drugs, the largest being for herbal cannabis (74.2%), cannabis plants (44.6%), and cocaine (51.5%). There was a decrease in the quantity of seizures for a number of drugs including herbal cannabis, cannabis resin, cocaine, crack and heroin (National Report, 2007).

2.1.3 Retail/Consumption

1. Price of cannabis at retail level, 2005, EMCDDA Table PPP-1 Part (i)-PRICE-CANNABIS.htm

2. Price of heroin at retail level, 2005, EMCDDA Table PPP-2 Part (i)-PRICE-HEROIN.htm

3. Purity of heroin at retail level, 2005, EMCDDA Table PPP-6 Part (i)-PURITY-HEROIN.htm

4. Price of cocaine products at retail level, 2005, EMCDDA Table PPP-3 Part (i)-PRICE-COCAINE.htm

5. Purity of cocaine products at retail level, 2005, EMCDDA Table PPP-7 Part (i)-PURITY-COCAINE.htm

6. Price of synthetic drugs at retail level, 2005, EMCDDA Table PPP-4 Part (i)-PRICE-SYNTHETIC.htm

7. Purity of synthetic drugs at retail level, 2005, EMCDDA Table PPP-8 Part (i)-PURITY-SYNTHETIC.htm

Data from law enforcement agencies show that the average price of amphetamines, crack, ecstasy and heroin fell in 2006, whilst cocaine and cannabis herb prices remained stable (National Report, 2007).

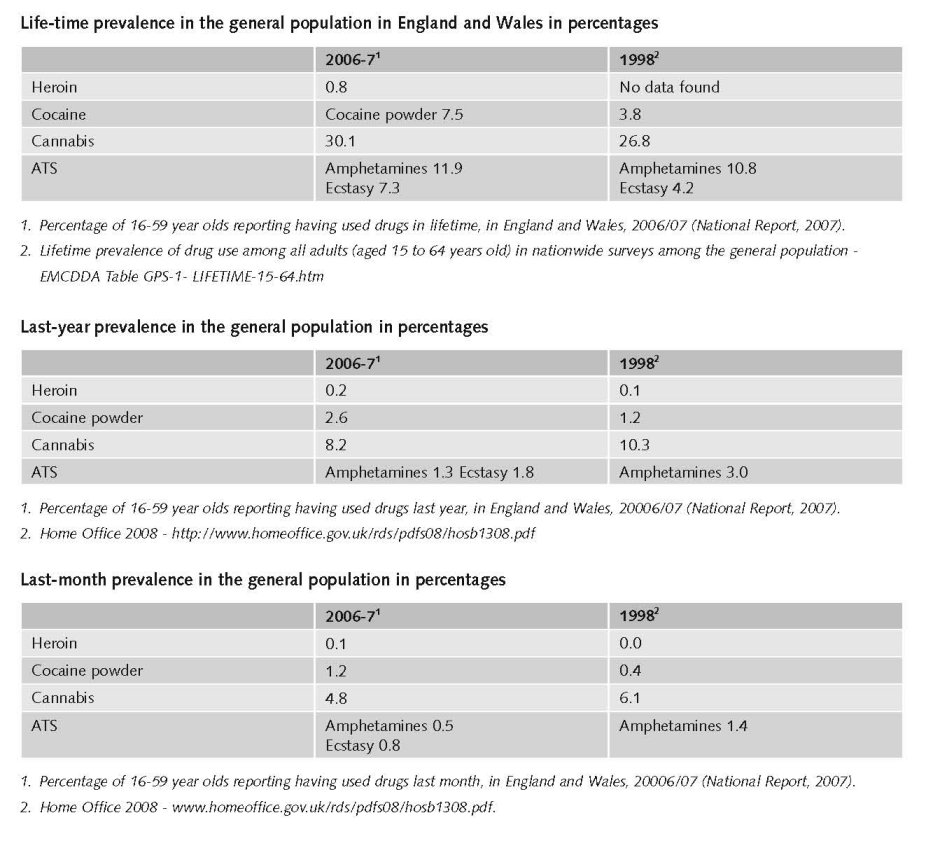

2.2 Drug Demand

Survey data on drug use amongst adults in England and Wales (2006/07) show that the fall in recent prevalence of drug use, first seen in 2004/05, has continued. This is mainly accounted for by a fall in cannabis use. Similar trends are seen in Northern Ireland. In Scotland, changes in the methodology of the 2006 survey mean that it is not possible to make any meaningful comparisons with previous surveys.

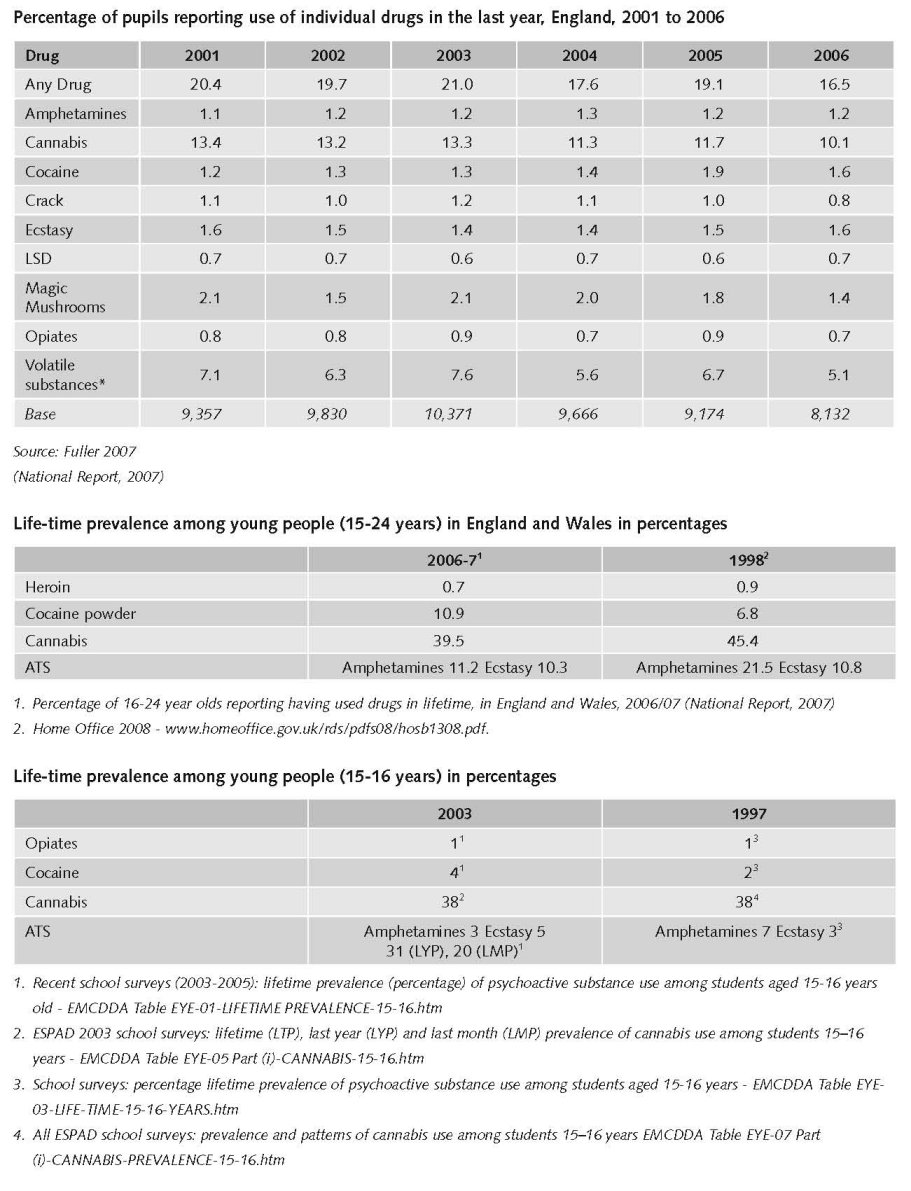

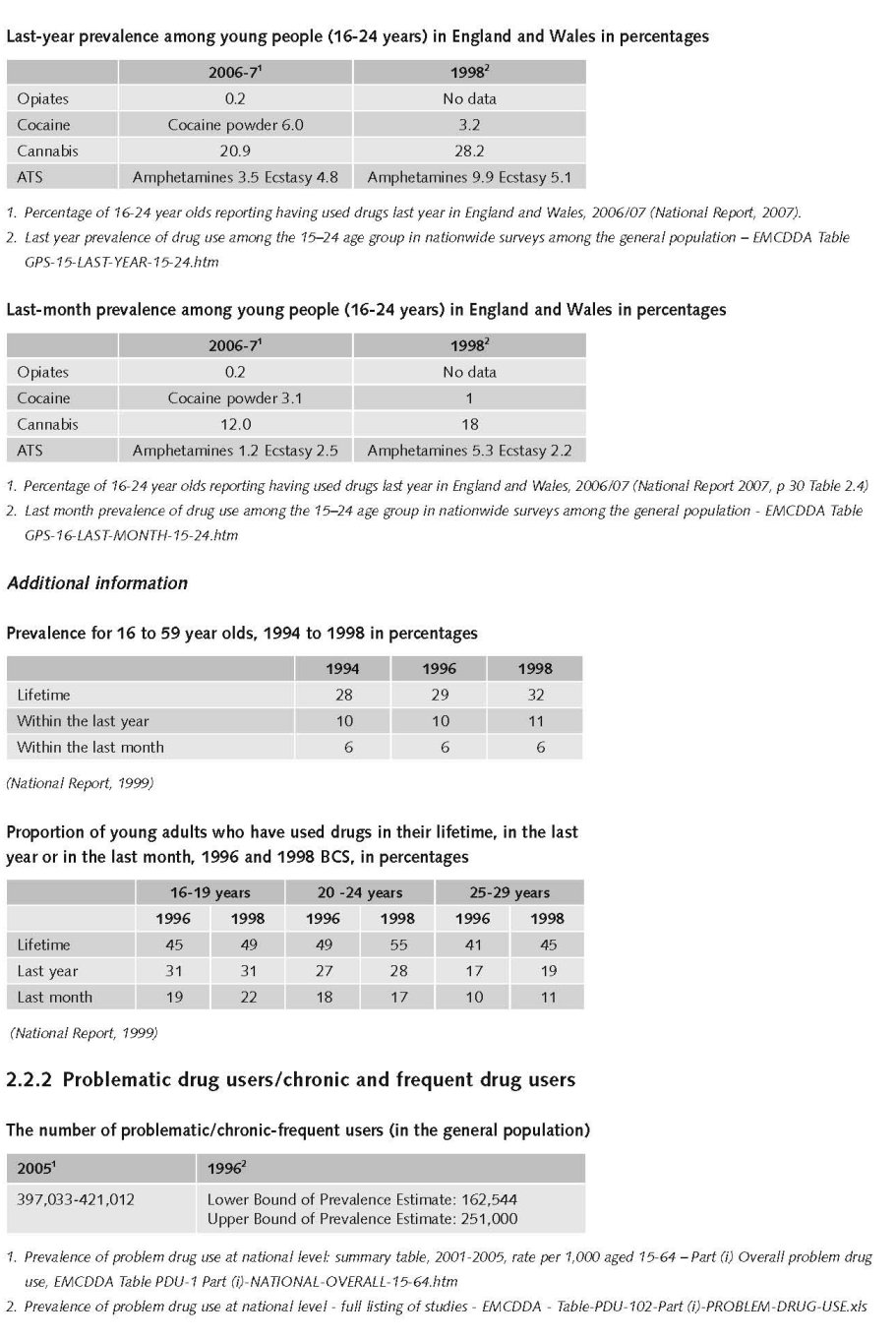

While prevalence amongst young people (aged 16 to 24) continues to be much higher than amongst the adult population as a whole, similar trends to those found in the wider group can be seen, with declining overall drug use and cannabis use. Use of cocaine, however have continued to increase.

Amongst school children prevalence also continues to fall. The decrease is mainly attributable to a fall in the two most common drugs, cannabis, and, amongst this group, volatile substances. Cocaine use appears to be stable (National Report, 2007).

Young adults under 35 are significantly more likely to use drugs, and amongst those who are under 25 years old, recent (last year) and current (last month) prevalence is higher still. In England and Wales, amongst these young adults, there has nevertheless been a steady decline in the recent use of any drug since 1998 (National Report, 2007).

Cannabis continues to be the most commonly used drug across all age groups, with prevalence rates close to those for use of any drug. Use of other drugs is considerably lower. Since the late 1990s the British Crime Survey shows that use of cocaine increased substantially and it is now the second most used drug amongst adults. However, there has been a corresponding decline in use of amphetamines, previously the second most used drug (National Report, 2007).

2.2.1 Experimental/recreational drug users in the general population

Life-time prevalence among young people (15-24 years) in percentages

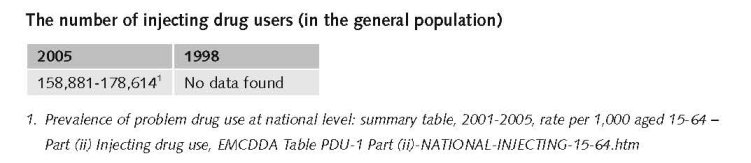

Evidence from research into problem drug use shows that opiates continue to be the main problem drug in the United Kingdom. Use of cocaine has continued to rise within the general population and is the second most used drug after cannabis. (National Report, 2007) Cannabis remains by far the most used drug in the general population in England and Wales, but use has declined significantly since 1998. (National Report 2007) Ecstasy remains the third most used drug in the general population, higher amongst young aged 16 to 24 (5%) though recent data shows no significant change from the previous year. In the general population recent and current use amphetamines remains low in the general population (National Report, 2007).

Expert comments

Problem drug use estimates in the UK are available at country (i.e. England, Northern Ireland, Wales or Scotland) and local level. Estimates are obtained though the capture-recapture and/or multiple indicator method, as is found to be appropriate for the data concerned. Definitions of problem drug use vary. Latest estimates for England are for 2005–06, are based on the capture-recapture method where possible, and, defining problem drug use as those who use opiates and/or crack, suggest 332,090 problem drug users, a rate of 10.2 per 1 000 population aged 15 to 64. In the United Kingdom as a whole, using data from recent studies (based on different time periods and definitions of problem drug use), the focal point estimated that there were 398,845 problem drug users, a rate of 10.15 per 1,000 population aged 15-64 (Country Overview).

2.3 Drug related Harm

2.3.1 HIV infections and mortality (drug related deaths)

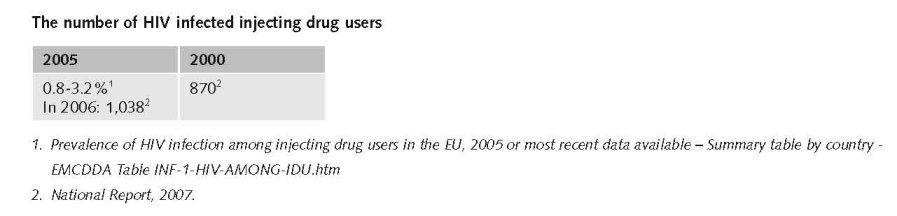

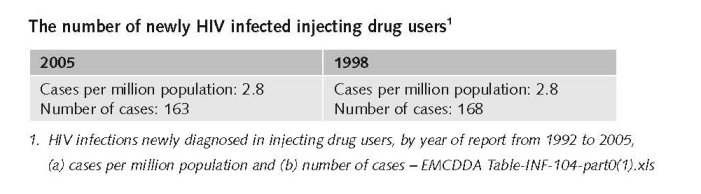

The overall prevalence of HIV seen among IDUs in 2006 was similar to that seen in recent years, and remains higher than that seen in the late 1990s (National Report, 2007).

In 2006, 1,038 HIV-infected IDUs were seen for HIV-related treatment or care in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, a 19 per cent increase since 2000 when 870 IDUs were seen for care. In Scotland, 387 HIV-infected IDUs were seen for HIV-related treatment or care in 2006, an 11 per cent decrease since 2000 when 436 IDUs were seen for care (National Report, 2007).

Additional information

• Opiates/opioids (i.e. heroin/morphine; methadone; other opiates/opioid analgesics), alone or in combination with other drugs, accounted for the majority (68%) of fatalities. Heroin/morphine alone or in combination with other drugs, accounted for the highest proportion (46%) of fatalities;

• Deaths involving methadone were more likely to be the result of illicit rather than prescribed drugs (62% or more);

• There was an increase in the number of cases involving methadone from 198 to 217;

• The proportion of cases involving methadone increased from 12 per cent to 17 per cent;

• The proportion of cases involving alcohol-in-combination increased from 26 per cent to 32 per cent;

• The proportion of cases involving heroin/morphine decreased from 46 per cent to 44 per cent (National Report, 2007).

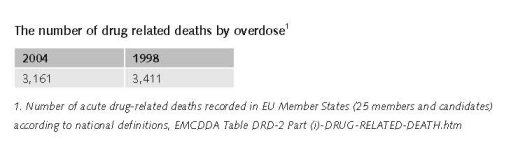

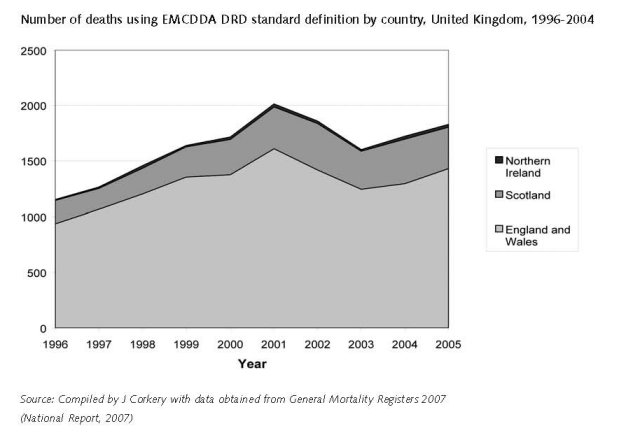

Based on the Drug Strategy definition, the number of drug-related deaths in the UK rose steadily between 1996 to 2001, fell from 2001 to 2003, but has risen subsequently to 1979 in 2005. Males accounted for about 77.8% of deaths and the average age of those dying was 37.7 years (Country Overview).

2.3.2 Drug related crime or (societal) harm

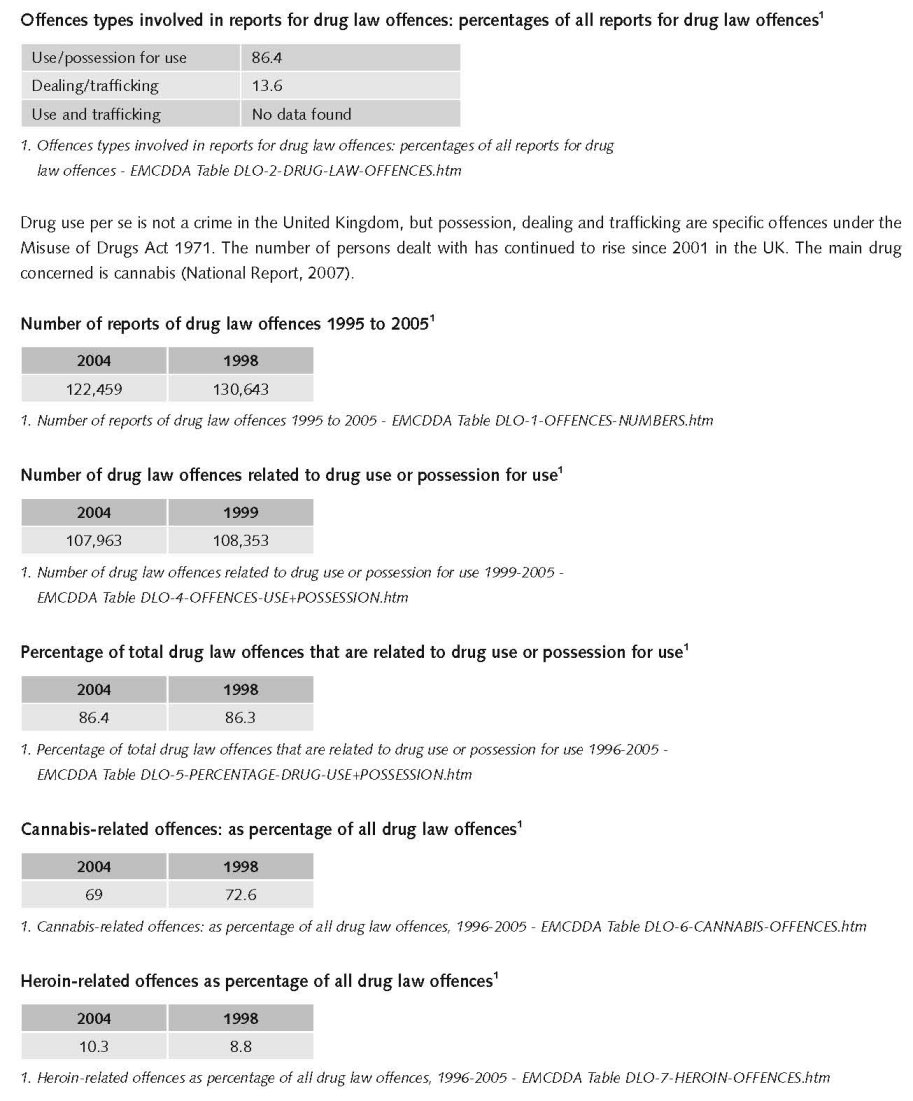

The number of persons dealt with has continued to rise since 2001 in the UK. The main drug concerned is cannabis (National Report, 2007).

General criminal offences routinely recorded by the police do not contain information on the offenders’ drug habits, neither do specific drug law offences. It is therefore not possible to provide an accurate estimate of the number of offences that are drug related, but there is substantial research evidence of the link between drug use, particularly use of heroin and crack cocaine, and acquisitive crime. Around three quarters of the users of these drugs admit to committing crime to support their habit. Over two-thirds of those in custody are reported to be problematic drug users. However, acquisitive crime, to which drug related crime makes a substantial contribution, has continued to fall in recent years (National Report, 2007).

3 Drug policy

3.1 General information

3.1.1 Policy expenditures

In 2005/06, labelled expenditure in the United Kingdom is estimated at €1.5 billion. Using a number of sources, it is possible to identify and estimate attributable proportions of unlabelled expenditure across multiple government functions such as health, public order and safety, social protection and education. Estimated unlabelled expenditure for 2005/06 is €7.3 billion, two-thirds of which is public order and safety expenditure with almost a quarter (24%) spends on child and family social work. Estimated overall expenditure is €8.7 billion which amounts to 0.48% of GDP or €144.43 per capita (National Report, 2007).

There is no full overview of expenditures for demand reduction in the UK. The national reports give some data for some countries as e.g. the 2007 report. For 2007/2008 there was a budget of €81 million available for the Young People’s Substance Misuse Partnership Grant for England. This budget is for the delivery of a range of local universal, targeted and specialist substance misuse interventions for children and young people (National Report, 2007).

The 2007/08 Pooled Drug Treatment Budget for England was announced to increase from €550m to €569m. In addition, €14.7 million capital funding will be distributed and €79.7 million in capital funding was made available to increase capacity for in-patient and residential (Tier 4) services in England in 2007/08 and 2008/09.

In 2005/06 €97.6 million was invested by the Scottish Government to tackle the drug problem across Scotland. €8.8 million a year was allocated for 2005/06 and 2006/07 to enable more people to enter treatment (National Report, 2007).

3.1.2 Other general indicators

A United Kingdom Drug Strategy was launched in 1998 (UKADCU 1998) setting four principal aims: preventing drug use amongst young people; safeguarding communities; providing treatment; and reducing availability, to be achieved through education, prevention programmes, expanded treatment, legal sanctions and the expansion of legal opportunities. The strategy was updated in 2002 with an increased emphasis on Class A drugs and problem drug users (DSD 2002). Government targets for the strategy are detailed in Public Service Agreements (PSAs). New agreements for reducing the harm caused by drugs (and alcohol) were set in October 2007 placing responsibility on a number of Government departments to meet the targets set. Each of the devolved administrations (Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales) has its own strategy, tailored to its individual circumstances (Scottish Office 1999; National Assembly for Wales 2000; DHSSPSNI 2006) (National Report, 2007).

In early 2008, the United Kingdom adopted its second ten-year drug strategy 2008–18 called ‘Drugs: protecting families and communities’. The strategy focuses mainly on illicit drugs, is comprehensive and covers four broad fields: law enforcement; prevention; treatment and social re-integration; and communication. It is complemented by a three-year action plan which sets 86 actions to be implemented during that timeframe and by a system of public service agreement (PSA) targets which will be maintained and reviewed on a regular basis. There is also devolution of powers to Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales and the UK Government is responsible for setting the overall strategy and for its delivery in the devolved administrations only in those areas where it has reserved powers. Thus, each of the devolved administrations has its own strategy (Country Overview).

Numbers available on arrests and imprisonment for drug-law related offences

Offences under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 recorded by the police show that of a total of 5,428,300 recorded in England and Wales in 2006/07 194,300 (4%) were drug crimes. This is an increase of nine per cent from the previous year (178,500). This is largely attributable to increases in the recording of possession of cannabis offence (National Report, 2007).

Numbers available on arrests and imprisonment for use/possession for personal use

The general term ‘reports for drug law offences’ is used since definitions and study units differ widely between countries. For definitions of the term ‘reports for drug law offences’, refer to Drug law offences – methods and definitions.

Expert comments

General criminal offences routinely recorded by the police do not contain information on the offenders’ drug habits, neither do specific drug law offences. It is therefore not possible to provide an accurate estimate of the number of offences that are drug related, but there is substantial research evidence of the link between drug use, particularly use of heroin and crack cocaine, and acquisitive crime. Around three quarters of the users of these drugs admit to committing crime to support their habit. Over two-thirds of those in custody are reported to be problematic drug users. However, acquisitive crime, to which drug related crime makes a substantial contribution, has continued to fall in recent years (National Report, 2007).

3.2 Supply reduction: Production, trafficking and retail

Main focus in UK is on consumption and on trafficking (mainly import).

Priorities of supply reduction covered by policy papers and/or law

The Misuse of Drugs Act 1971, with amendments, is the main law regulating drug control in the UK. It divides controlled substances into 3 Classes (A, B, C) with A being the most dangerous. These Classes provide a basis for attributing penalties for offences. Maximum penalties vary not only according to the Class of substance but also whether the conviction is a summary one made at the Magistrate court or one made on indictment following a trial at Crown Court (Country overview).

Drug use per se is not an offence under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971: it is the possession of the drug which constitutes an offence. Summary convictions for the unlawful possession of Class A drugs such as heroin or cocaine involve penalties of up to 6 months’ imprisonment or a fine; on indictment penalties may reach 7 years’ imprisonment. Class B drugs such as amphetamines attract penalties at magistrate level of up to 3 months’ imprisonment and/or a fine; on indictment up to 5 years’ imprisonment and/or an unlimited fine. Possession of Class C drugs, such as barbiturates attracts penalties up to 3 months imprisonment and/or a fine at magistrate level, or up to 2 years’ imprisonment and/or unlimited fine on indictment. There are also a number of alternative responses such as a formal warning from the police, who have considerable powers of discretion. Cannabis will revert to being a class B drug in 2009 (Country overview).

Under the Misuse of Drugs Act, a distinction is made between the possession of controlled drugs, and possession with intent to supply to another; this latter is effectively for drug trafficking offences. The Drug Trafficking Act 1994 defines drug trafficking as any production or supply transportation import and export of drugs covered by the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971. The penalties applied depend again on the classification of the drug and on the penal procedure (magistrate level or crown court level). For trafficking in Class A drugs the maximum penalty on indictment is life imprisonment, while trafficking of Class B and C drugs can attract a penalty of up to 14 years in prison. In 2000, a minimum sentence of 7 years was introduced for a third conviction for trafficking in Class A drugs (Country Overview).

In the last years a more strict approach to trafficking offences was developed, including among others a minimum sentence of 7 years imprisonment for a third conviction for trafficking in Class A drugs (National Report, 2001).

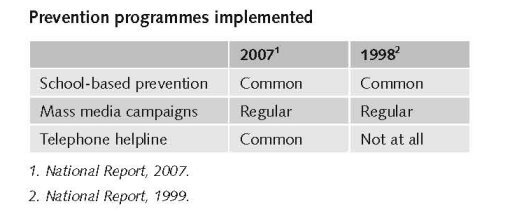

3.3 Demand reduction: Experimental/recreational drug use + problematic use/chronic-frequent use

Universal drug prevention initiatives are an important area of policy in the field of prevention. Communication programmes such as ‘FRANK’ in England and ‘Know the Score’ in Scotland, provide information and advice to young people and their families Throughout most of the United Kingdom, drug prevention is part of the national curriculum and most schools have a drug education policy and guidelines on dealing with drug incidents. Guidance on drug education recommends an approach that includes all psychoactive substances, including alcohol and tobacco, and places drugs education within the wider health and social education agenda (Country Overview).

In order to reinforce the law on cannabis and the harms associated with its use a widespread education campaign on the harms of cannabis (and all illegal drugs) has been implemented in 2006/7. In partnership with DfES, the Home Office has produced ‘Understanding Drugs’, a comprehensive teacher and pupil information pack which is now available to every secondary school in England (National Report, 2006).

There are various selective or indicative prevention initiatives targeting high risk groups. Examples are Positive Futures a national sports-based social inclusion programme aimed at marginalised 10 to 19 year olds with projects in most deprived areas in the country, and Sure Start a programme supporting children and their families from birth up to age 14 (up to age 16 for children with special needs or disabilities) (National Report, 2006).

Activities in recreational settings focus on harm reduction with safe clubbing guidelines and person-to-person intervention. Another important element of selective prevention is the focus on vulnerable young people such as young offenders, looked-after children, young homeless people, young people who have been sexually exploited or work in the sex industry, and children whose parents are drug users (Country Overview).

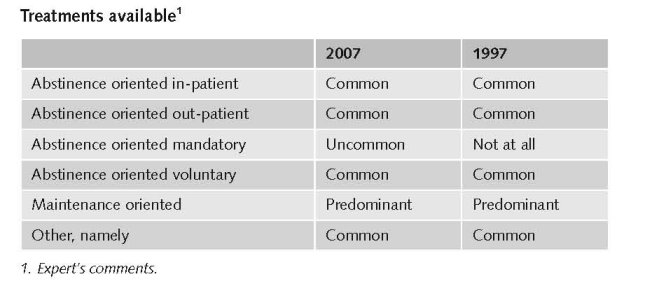

In most parts of the United Kingdom, particularly in England, there is a four-tier system of treatment providing a conceptual framework for treatment provision. Tier 1 refers to generic interventions such as information and advice, screening and referral to more specialist services. Tier 2 refers to open-access interventions, such as drop-in services providing advice, information and some harm reduction services such as syringe exchange. Tier 3 services are specialist community services and include prescribing services, structured day programmes and structured psychosocial interventions, such as counselling and therapy and community-based detoxification. Tier 4 services are in-patient services, including detoxification and residential rehabilitation. The majority of structured treatment is delivered at Tier 3, predominantly through community-based specialist drug treatment services (Country Overview).

Coordination and integration between a range of providers is seen as key in helping problem drug users reintegrate into society. While providing treatment remains a priority, the role of other service providers of housing, employment, education and training has also become important, leading to the concept of Wraparound Services. This integrated approach is seen through the introduction of the Drug Interventions Programme (DIP) in England and Wales, and the establishment of Criminal Justice Intervention Teams which have been developed to improve referral into treatment through the criminal justice system and for those in prison (see Chapter 9) (National Report, 2007).

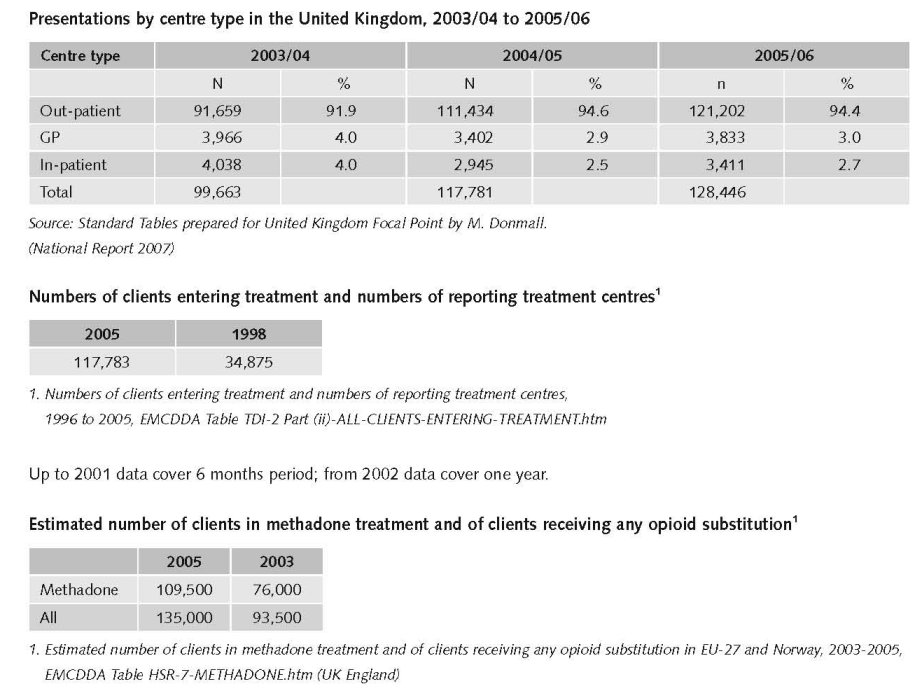

The 2005–06 treatment demand data for the United Kingdom was based on 1,678 treatment centres comprising of; 1,390 out-patient treatment centres, 88 in-patient treatment centres and 200 general practitioners. In 2005/06, a total of 128,446 clients entered treatment, out of which 49,625 were first time treatment clients (Country Overview).

In 2005–06, opioids were the most reported primary drug among all clients entering treatment at 65.1%, followed by cannabis at 15.8% and cocaine (including crack) at 11.5%. Treatment demand data among first time treatment clients indicated a similar trend with the primary substance of use being opioids at 49.7%, followed by cannabis at 24.8% and cocaine (including crack) at 15.8% (Country Overview).

In 2005/06, 29% of all clients entering treatment were over 35 years old. A lower age distribution was reported among new treatment clients with 37% under the age of 25 years. As far as gender distribution is concerned, 72% of all clients were male whereas, 28% were female. A similar trend in gender distribution was reported among first time treatment clients with 72% for male and 28% for female (Country Overview).

Substitution treatment remains the main treatment in the United Kingdom. Most substitution treatment is for opiate dependence, and the majority offered through specialist out-patient drug services, and increasingly in shared care with general practitioners. Oral methadone is the drug of choice for substitution treatment, but increasingly also buprenorphine, which has been available since 1999. Furthermore, injectable methadone and heroin are also available, albeit more rarely, in England. The Misuse of Drugs Act 1971, Section 7.3a stipulated that both methadone and buprenorphine treatment can be initiated and provided by medical doctors, specialised medical doctors and treatment centres. The total number of clients in substitution treatment in Scotland was 19 227 (2005 data), 463 in Northern Ireland (2006 data) and an estimated 146 500 in England (2006 data) (Country Overview).

The vast majority of treatments are reported through out-patient services (94%).

Methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) was introduced in 1968, high-dosage buprenorphine treatment (HDBT) in 1999 and heroin-assisted treatment (HAT) in the 1920’s (Year of introduction of methadone maintenance treatment (MMT), high-dosage buprenorphine treatment (HDBT) and heroin-assisted treatment, including trials - EMCDDA Table HSR-8-METHADONE-INTRODUCTION.htm).

Suboxone, a combination of naloxone alongside buprenorphine, was launched in early 2007 as an alternative treatment to methadone and buprenorphine. The formulation is designed to limit the potential for misuse, as well as lowering its street value. It is used for maintenance treatment of opioid dependence (National Report, 2007).

Limited supply of diamorphine, reported in the previous UK Focal Point Reports, continues although there has been substantial improvement (National Report, 2007).

(www.news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/6376713.stm)

Priorities of demand reduction (prevention) covered by policy papers and/or law

Prevention of young people’s drug use is a key element of drug strategies in the United Kingdom. There is a focus on better education and intervention for young people and families, especially those most at risk, and better public information about drugs. (8) This emphasis on drug prevention has not changed in the last decade as can be seen from the establishment of the Drugs Prevention Board in 1998 to improve coordination of prevention activity. Under the auspices of the UK Anti-Drugs Coordination Unit, the board had the task to take forward joint commissioning of effective prevention and education (National Report, 1999).

There has been a high focus on vulnerable young people. The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence has produced public health guidance on community-based interventions to reduce substance misuse among vulnerable and disadvantaged children and young people. The Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs has reported on the implementation of its recommendations on the children of drug using parents (National Report, 2007).

Priorities of demand reduction (treatment) covered by policy papers and/or law

All UK drug strategies give priority to the provision of better access to effective treatment, particularly for vulnerable or excluded groups, and to encourage client retention. Delivery of drug treatment is through local multi-agency partnerships, representing health criminal justice agencies and social care services (Country Overview).

According to guidance by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) treatment providers are expected to offer advice and information, care planned counselling, structured day care programmes, community prescribing, in-patient drug treatment and residential rehabilitation. In addition, drug misusers are to be offered relapse prevention and aftercare programmes; hepatitis B vaccinations; testing and counselling for hepatitis B and C and HIV; and needle exchange (National Report, 2007).

Since 1998 the government has provided additional funding to increase the number of drug using offenders engaged with treatment services. This included the introduction of Drug Treatment and Testing Order pilot schemes. Under this order courts may, with the offender’s consent, make an order requiring the offender to undergo treatment either as part of another community order or as a sentence in its own right. It is envisaged that such schemes will be available in all courts in England and Wales by 2001 (National Report, 2000).

The Drug Interventions Programme introduced in 2003 represented a fundamental change in the extent to which drug using offenders are engaged in treatment (www.homeoffice.gov.uk/crime-victims/reducing-crime/drug-related-crime).

Also proposals from the Department of Work and Pensions to ensure drug users receiving State benefits engage in treatment (www.dwp.gov.uk/welfarereform/noonewrittenoff).

Suboxone (buprenorphine/naloxone) has been licensed for use in the United Kingdom. (National Report 2007) since December 2006 It has been introduced to discourage the injecting of buprenorphine, by means of the naloxone component which precipitates withdrawal effects (National Report, 2007).

There is no legal basis for drug treatment in the UK. However, with the Dangerous Drugs Act 1967, diamorphine and, at that time, methadone, and, also cocaine, for the treatment of drug misuse cannot longer be prescribed by general practitioners, unless they applied for a licence to do so. Apart from a licensing requirement for these particular drugs, there has been no impediment to prescribing based on the clinical judgement of any doctor. However, when NICE issue a technology appraisal:

“.. guidance represents the view of the Institute, which was arrived at after careful consideration of the evidence available. Healthcare professionals are expected to take it fully into account when exercising their clinical judgement. The guidance does not, however, override the individual responsibility of healthcare professionals to make decisions appropriate to the circumstances of the individual patient, in consultation with the patient and/or guardian or carer.”

Also, NICE clinical guidelines are recommendations about the treatment and care of people with specific diseases and conditions in the NHS in England and Wales. This guidance represents the view of the Institute, which was arrived at after careful consideration of the evidence available. Healthcare professionals are expected to take it fully into account when exercising their clinical judgement. The guidance does not, however, override the individual responsibility of healthcare professionals to make decisions appropriate to the circumstances of the individual patient, in consultation with the patient and/or guardian or carer and informed by the summary of product characteristics of any drugs they are considering.

There were no changes during the past ten years concerning these legal provisions.

3.4 Harm reduction

3.4.1 HIV and mortality

Additional information

In UK different activities have been undertaken to reduce and prevent drug-related death including interventions like provision of awareness materials and overdose training for prison staff and prisoner (National Report, 2006).

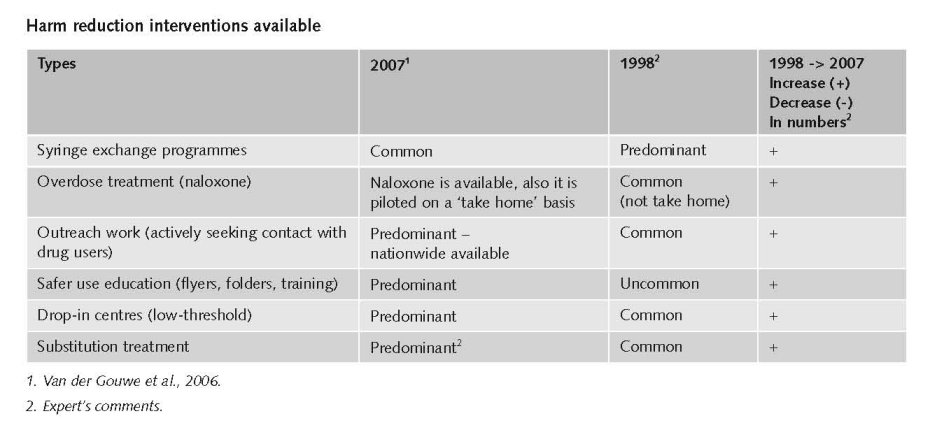

Interventions include information campaigns of the risks associated with drug use, as well as information on safer injecting and safer sex, needle exchange schemes, infection counselling, support and testing, vaccinations against hepatitis B. In May 2007, the Department for Health (DH) and the National Treatment Agency (NTA) published a document entitles ‘Reducing drug-related harm: an action plan’. One of its aims is to improve delivery, by issuing guidance on reducing drug-related harm to commissioners, service users, carers and those working with drug users. This includes guidance on hepatitis C, the provision of needle exchange services and testing, and treatment for blood-borne virus infections in prisons and the community. The Action Plan also contains plans for a health promotion campaign, which will be targeted at risk groups such as homeless drug users, speedballers (i.e. those injecting heroin and crack together) and potential or new injectors. Syringe exchange is offered by a wide range of services, including specialist syringe exchange services, detached outreach and mobile units, pharmacies, and accident and emergency services. Consumption rooms are not available in the UK. In England trials are being conducted to establish the potential role that increased availability of injectable opiates can play in reducing the harms associated with drug use. In 2003, the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 (see section on national drug laws) was amended to allow doctors, pharmacists, and drug workers to legally supply swabs, sterile water, certain mixing utensils and citric acid to drug users who obtained controlled drugs without a prescription (Country Overview).

Drug-related deaths (DRDs), infectious diseases, co-morbidity and other health consequences are key policy issues within the United Kingdom drug strategies (Scottish Office, 1999; National Assembly for Wales, 2000; DSD, 2002; DHSSPSNI, 2006).

A strategy for England and Wales was published in 2001, focusing on promoting treatment, with service providers expected to provide information and advice on how to reduce DRD, to educate drug users and their families on resuscitation, educate prisoners on the risk of overdose on release from prison, and training of paramedical and Accident and Emergency (A&E) staff. This has been updated in 2007 with the publication of a new Reducing Drug-related Harm: An Action Plan. In Scotland a strategy and action plan to reduce DRD was published in 2005.

Throughout the United Kingdom there is information about volatile substances available on drug information websites.

The Scottish Government and the Health Promotion Agency in Northern Ireland ensure that young people, parents and retailers are aware of the dangers of abusing products such as cigarette lighter refills, aerosol sprays and glue. In Scotland 90 per cent of Scottish schools include advice on the risks from volatile substance abuse.

In the 1980s, United Kingdom drug policy was led by a public health approach aimed at containing HIV transmission.

The subsequent action, involving harm reduction measures, is regarded as having been successful in containing HIV amongst injecting drug users (IDUs); providing free needles and syringes, promoting the safe disposal of used equipment, information campaigns on safer sex and safer injecting; and HIV/AIDS counselling, support and testing. The Hepatitis C Action Plan for England was developed in 2004, prioritising prevention of infection and disease progression. Treatment for infectious diseases is provided as part of the National Health Service (NHS), including the provision of anti-retroviral treatment for HIV and HCV. Treatment for wound infections is available through primary care, Accident and Emergency (A&E) departments, and in some areas, through needle exchange schemes and specialist drug services. Those in prison have access to HIV and hepatitis testing, and vaccination against HBV. In England, Reducing Drug-related Harm: An Action Plan, also focuses on infectious disease and DRD (National Report, 2007).

Legal changes implemented during the past ten years

An amendment to the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 was made in 2003 to allow doctors, pharmacists and drug workers to legally supply swabs, sterile water, certain mixing utensils (e.g. spoons, bowls, cups and dishes) and citric acid to drug users who obtained controlled drugs without a prescription came into force in August 2003 (National Report, 2004).

3.4.2 Crime, societal harm, environmental damage

The impact of policies and strategies in the last ten years

In a report looking at the impact of crime reduction policies and strategies since 1997, Enver et al. (2007) reviewed drug misuse. The authors argue that despite apparent progress against a number of targets including: numbers in treatment; targets on drugs and young people; and reducing health harms, there is a degree of disconnection between policies and targets and what might actually be happening in terms of real levels of drug use, availability and associated harms, for example where the number of arrests for young people using cannabis contribute to police targets on drug arrests (National Report, 2007).

Tackle crime and anti-social behaviour associated with drug misuse and reduce the harms caused by drugs to the community and use the criminal justice system to help offenders engage with treatment services (National Report, 2007).

The most important statement is to tackle crime and anti-social behaviour associated with drug misuse and reduces the harms caused by drugs to the community and use the criminal justice system to help offenders engage with treatment services (National Report, 2007).

During the past ten years there was an emphasis on treatment linked to crime and anti-social behaviour.

Priorities of harm reduction covered by policy papers and/or law

The Drugs Act 2005. The Stationery Office, London. Available: www.opsi.gov.uk/acts/acts2005/ukpga_20050017_en_1;

The Anti-Social Behaviour Act 2003. The Stationery Office, London. www.opsi.gov.uk/acts/acts2003/ukpga_20030038_en_1

References

Consulted experts

G. Eaton, Project Manager, National Focal Point, London.

Documents

CIA. The World Factbook: United Kingdom. Available: www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/uk.html, last accessed 15 December 2008.

Country overview: United Kingdom. Available: www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/country-overview/uk, last accessed 15 December 2008.

Home Office. Measuring different aspects of problem drug use: methodological developments, 2006. Available: www.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/pdfs06/rdsolr1606.pdf, last accessed 15 December 2008.

Home Office. Drug Misuse Declared: Findings from the 2007/08 British Crime Survey, 2008. Available: www.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/pdfs08/hosb1308.pdf, last accessed 15 December 2008.

National Report to the EMCDDA, United Kingdom, 1999.

National Report to the EMCDDA, United Kingdom, 2000.

National Report to the EMCDDA, United Kingdom, 2001.

National Report to the EMCDDA, United Kingdom, 2004.

National Report to the EMCDDA, United Kingdom, 2006.

National Report to the EMCDDA, United Kingdom, 2007.

Van der Gouwe D, Gallà M, Van Gageldonk A, Croes E, Engelhardt J, Van Laar M, Buster M. Prevention and reduction of health-related harm associated with drug dependence: an inventory of policies, evidence and practices in the EU relevant to the implementation of the Council Recommendation of 18 June 2003. Utrecht, Trimbos Institute, 2006.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|