Appendix to report 4: country reports SWITZERLAND

| Reports - A Report on Global Illicit Drugs Markets 1998-2007 |

Drug Abuse

SWITZERLAND

1 General information

Location:

Central Europe, east of France, north of Italy

Area:

41,290 sq km

Land boundaries/coastline:

1,852 km

Border countries:

Austria 164 km, France 573 km, Italy 740 km, Liechtenstein 41 km, Germany 334 km

Population:

7,581,520 (July 2008 est.)

Age structure:

0-14 years: 15.8% (male 623,213/female 577,430)

15-64 years: 68.2% (male 2,605,044/female 2,562,354)

65 years and over: 16% (male 501,699/female 711,780) (2008 est.)

Administrative divisions:

26 cantons

GDP (purchasing power parity):

$303.2 billion (2007 est.)

GDP (official exchange rate):

$423.9 billion (2007 est.)

GDP- per capita (PPP):

$40,100 (2007 est.) (CIA The World Factbook)

Drug research

Switzerland has a number of institutes that deal with drug research, like the Institut für Sucht und Gesundheitsforschung (ISGF) in Zürich, l’Institut universitaire de médecine sociale et préventive in Lausanne, SFA/ISPA (Schweizerische Fachstelle für Alkohol und andere Drogenprobleme) in Lausanne, Narcotic Control Schweizerisches Heilmittel Institut SWISSMEDIC and Bundesamt für Statistik.

Main drug-related problems

Consumption is the main drug-related problem in Switzerland. Switzerland is a substantial producer of cannabis herb in Europe. Trafficking includes export of cannabis herb and import of other illicit drugs for the domestic market.

2 Drug problems

2.1 Drug supply

2.1.1 Production

Switzerland has, for instance, reported a sharp increase in illegal cannabis cultivation. A 1999 Swiss EKDT report argued that in 1998 more than 100 tonnes of cannabis were harvested for the drug trade, and it was plausible that Switzerland became the second largest European exporting country after the Netherlands (EMCDDA, 2008).

2.1.2 Trafficking

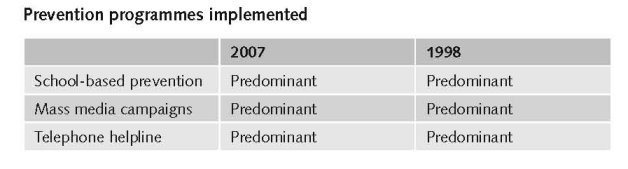

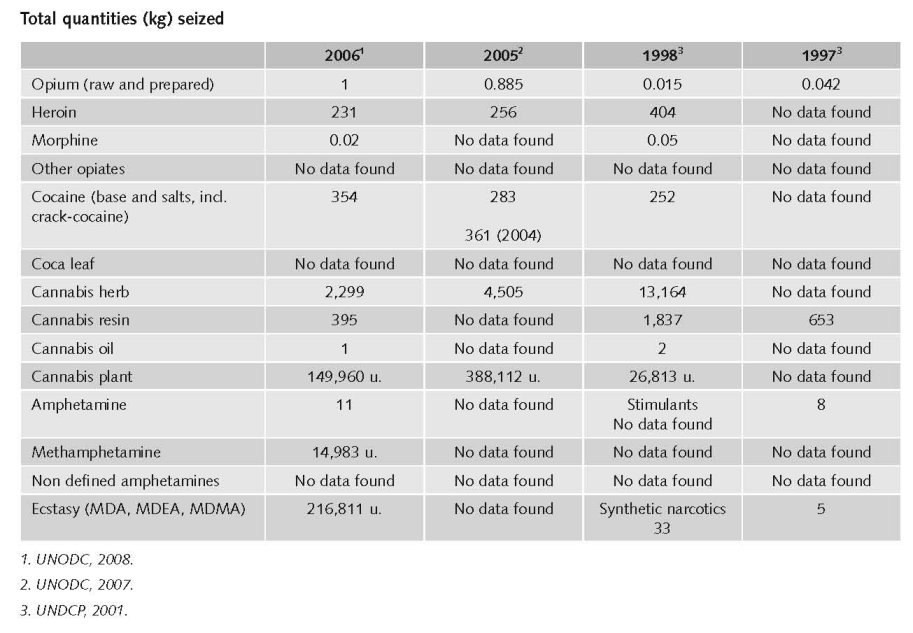

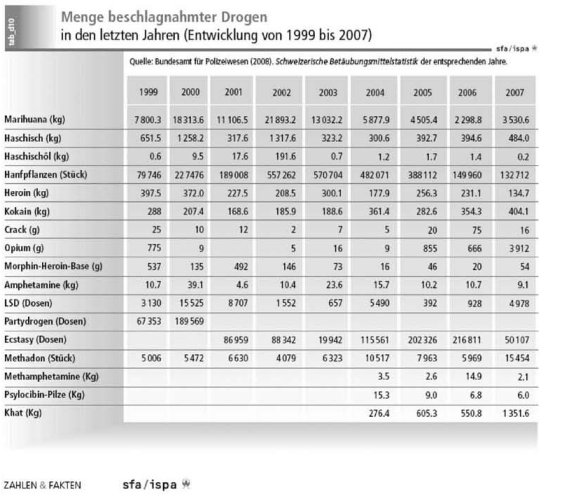

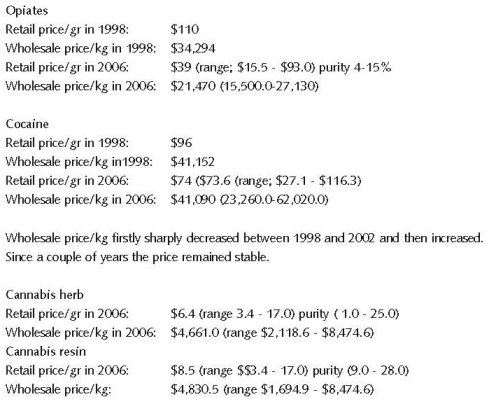

Amounts of seized drugs in the period 1999 - 2007

(SFA/ISPA, 2008f)

2.1.3 Retail/Consumption

2.2 Drug Demand

2.2.1 Experimental/recreational drug users in the general population

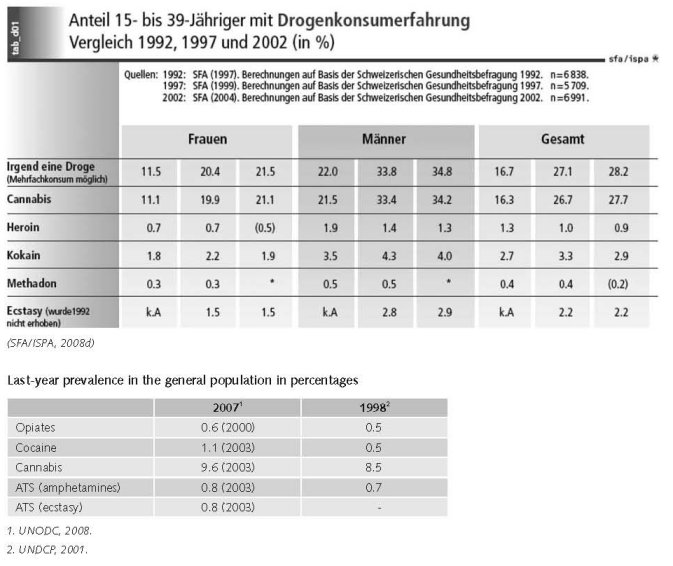

If one takes Switzerland’s resident population aged between 15 and 39 as a whole, only a minority have ever used drugs in their lives. For substances such as heroin, cocaine and ecstasy, the proportion is less than 4% (MaPaDroIII, 2006).

The situation is somewhat different with cannabis, where a good quarter of the population have tried it at least once. Unlike the other substances, where use has remained stable, cannabis use has increased slightly. But even here non-consumption is clearly still the norm among the population (MaPaDroIII, 2006).

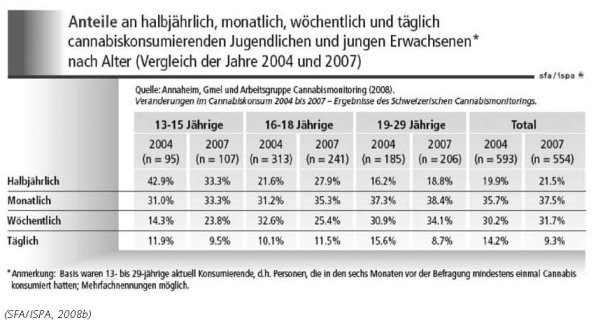

Half yearly, monthly, weekly and daily cannabis consumption among youth and young adults

(comparison of 2004 and 2007) differentiated in age groups (13-15 years, 16-18 years, 19-29 years and total)

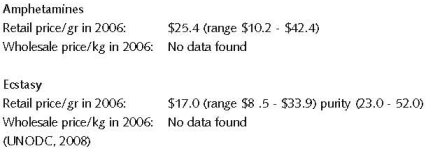

The UNODC 2008 ATS Assessment does not mention Switzerland at all. This would assume that either no data about the use of ATS are available in Switzerland or that ATS is not commonly used and/or produced in Switzerland. Since no other reports mention anything about ATS use in Switzerland, it seems that consumption of ecstasy and/or (meth-) amphetamines in Switzerland is low (UNODC, 2008a).

Prior to the release of the new household survey for 2006, Germany had reported stable cocaine use levels. The same applied to most neighbouring countries, including Austria, Switzerland, Belgium, the Netherlands, Denmark, Poland, the Czech Republic and other central European countries (Slovakia and Hungary) (UNODC, 2008).

In 2002 almost half of young people in their ninth school year (age 16) admitted having tried cannabis at least once. Furthermore, the average age of first use has fallen (FOPH, 2007).

Nevertheless, it is worth pointing out that young people of school age only seldom use other illegal substances such as heroin, cocaine and synthetic drugs (including ecstasy).

Leaving aside cannabis experimenting with synthetic drugs, cocaine and other illegal substances increases at the age of about 18. Only a small minority takes these drugs regularly. Only a very few try heroin. On the other hand, some two thirds of 20-year-olds have tried cannabis at least once. Regular use of this substance in particular increases after the end of obligatory schooling (age 16), especially among young men. 13% of them use cannabis on a daily basis; the figure for young women is 4%. Nevertheless there are certain indications that cannabis use among young people has gradually stabilised in recent years (FOPH, 2007).

2.2.2 Problematic drug users/chronic and frequent drug users

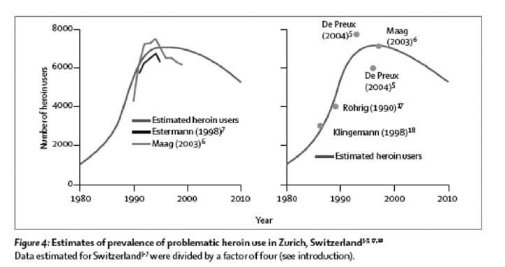

On the basis of existing data it can be assumed that the number of heroin dependents dropped from around 30,000 in 1992 to 26,000 in 2002 (MaPaDroIII, 2006).

Estimates of prevalence of problematic heroin use in Zurich

(SFA/ISPA, 2008e)

A SFA study on use of medicinal drugs estimates that 1 percent of the adult population in Switzerland is dependent (i.e. around 60 000 persons) (SFA, 2008e).

According an estimate of the Federal Office of Public Health there are 30,000 problem drug users in Switzerland (expert’s comments).

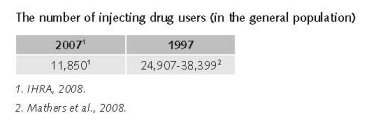

Mathers et al. report that in 1997 the prevalence of people who inject drugs among 15-64 years in Switzerland was between 0.51% (low) to 0.65% (mid) to 0,78% (high). The estimated number of people who inject drugs varies from 24,907 (low) to 31,653 (mid) to 38,399 (high). (Mathers et al., 2008).

In 2007, there are an estimated 11,850 people who inject drugs in Switzerland (IHRA, 2008). The age of this population is going up (expert’s comments).

Expert comments

The figures on problem use in Switzerland are rather weak.

2.3 Drug related Harm

2.3.1 HIV infections and mortality (drug related deaths)

Mathers et al. report that a 2004 estimate of prevalence of HIV among injecting drug users is 1.4%. (Mathers et al., 2008) Another survey mentions an adult HIV prevalence of 0-1.7% among people who inject drugs in 2007 (IHRA, 2008).

As the prevalence of HIV among drug users is still very high (between 10 and 30%) changes in harm reduction services and in individual consumer behaviour could easily result in an increase of new infections. (SFA 2008c) The rate of HIV/AIDS infection has levelled off at 5% to 15%, but hepatitis is widespread. There are indications that almost all dependent drug users are infected with the Hepatitis C virus (FOPH, 2007).

In 1994 28.0% (women) and 24.9% (men) of positive HIV-tests had to be explained by intravenous drug use. In 2006 this figure decreased to 7.2% (women) and 8.2% (men). The 2007 figures show a slight increase. 61 of the total 735 newly infected men and women in 2007 got infected through intravenous drug use. More than two-third of this group were men (SFA, 2008c).

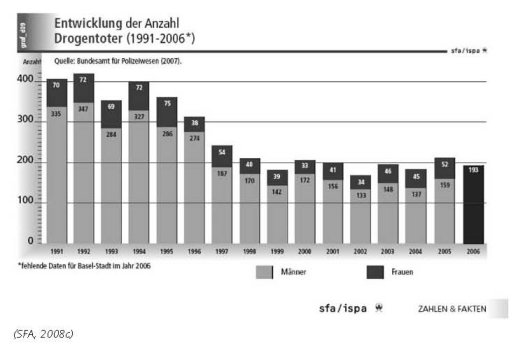

The number of drug related deaths by overdose

Number of drug-related death between 1991 and 2006 (light columns: male, dark columns: women)

2.3.2 Drug related crime or (societal) harm

No information found on harm for society.

3 Drug policy

3.1 General information

3.1.1 Policy expenditures

3.1.2 Other general indicators

In Switzerland there are a number of problems for concerted action in the field of drug policy and practice. An important one is that the Narcotic law is arranged at Federal level; the health and law enforcement are at Cantonal level and finally the social services and welfare they work at municipal level (Uchtenhagen, 2007).

In 1991 the Federal Council decided on a first package of measures to reduce the drugs problem (MaPaDro I 1991-1997). (FOPH 1991) It gave the Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH) the task of implementing measures in the areas of prevention and therapy, and later in harm reduction. Not included in either of these packages was law enforcement which was instead handled separately. These measures are based on a model of 4 pillars (prevention, therapy and reintegration, harm reduction, and repression and control). Their primary objectives are: to maintain and improve the state of health and social integration during the phase of active drug use; to decrease and hinder the entry into dependence; to increase and facilitate an exit from dependence (i.e. to decrease the number of drug users, the main expected outcome). (De Preux et al., 2004) These measures were strengthened and taken further in a second package of measures (MaPaDro II, 1998–2002; FOPH, 1998).

Since the Confederation has no constitutional competence in drug policy, it cannot enforce this model in a top-down manner. Instead, it must rely on other means in order to convince the main players of Swiss drug policy – the cantons and the cities – to adopt its ideas (Kubler & Widmer, 2004).

Main objective of drug policy of the federal government is a reduction of drug-related problems. This objective is to be implemented by achieving three goals:

• Reducing the consumption of drugs;

• Reducing the negative consequences for drug users;

• Reducing the negative consequences for society as a whole.

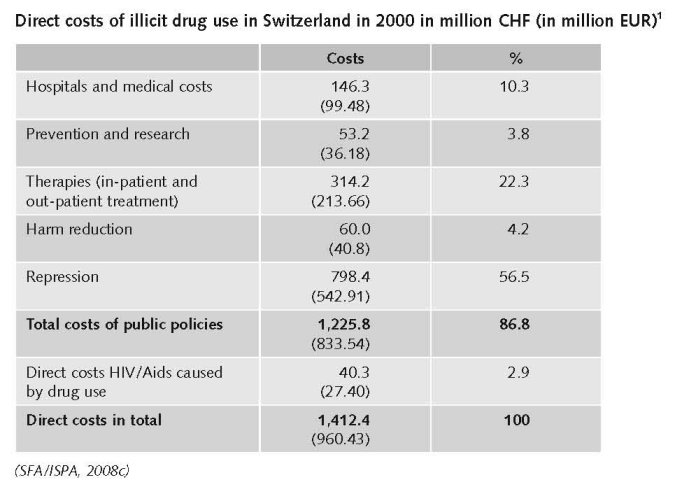

1 1 CHF = €0.68. Exchange rate in 2000.

In implementing its drugs policy the federal government will continue to base its global strategy on the four pillar model:

• Prevention helps to reduce drug consumption by making it harder to start using drugs and by preventing the development of addiction.

• Therapy helps to reduce drug consumption by enabling users to break free of their dependency and to stay free of it, or at least by keeping this option open to them. In addition it promotes the social integration of those under treatment and helps to improve their health.

• Harm reduction helps to reduce the negative consequences of drug use on the consumer and indirectly on society as well, by providing individually tailored and socially less problematic ways of consuming drugs.

• Law enforcement uses appropriate regulatory measures to implement the prohibition of illegal drugs, thus helping to reduce the negative consequences of drug taking for society as a whole (FOPH, 2007).

MaPaDro III (the federal government’s third package of measures to reduce drug-related problems 2006−2011) is designed to open up the four pillars of this policy and increase the interchange between them. The federal government’s role is concentrated above all in the following areas: drawing up the basic principles, evaluation, further training for drug professionals, quality enhancement, information, coordination and international cooperation. Furthermore, in implementing its drugs policy the federal government is paying particular attention to the two cross-sectoral issues of gender and migration (FOPH, 2007).

In recent years the drugs problem has changed and new ways of intervening are required. MaPaDro III identifies the need to adapt and aims to open up the four separate pillars. MaPaDro III is the first package to define the basic principles underlying all four pillars – including law enforcement – which should make it possible to harmonise them better and do away with some of the barriers between them. Furthermore, as MaPaDro III is implemented, the broader context of addiction policy, which also includes legal substances, will be taken into account where necessary and where possible at the current point in time (FOPH, 2007).

The broad consensus on drugs policy born in the 1990s under the impact of the open drugs scenes, has crumbled. There is a greater need to justify drugs policies, not least because of the pressure to make savings in the public purse. MaPaDro III provides a response to this pressure for justification. By describing the current situation and the basic principles underlying the policy, and by demonstrating the continuing need for action, it makes clear the reasons for the federal government’s involvement in drugs policy. Furthermore, in defining goals, strategies and measures it makes the nature of the federal government’s undertaking more visible (FOPH, 2007).

As far as illegal drugs are concerned, a number of measures are implemented by a wide range of very different players in all four pillars. Yet a coherent drugs policy able to cope with the growing complexity of the problems requires that the aims and activities of all the players should be coordinated. In order to deal with this need for coordination, MaPaDro III for the first time defines common basic principles applying to all the pillars, thus making it possible to improve internal coordination between the federal bodies. On the basis of its position in the structure, which gives it a national and international perspective, the federal government also acts as moderator and coordinator in encouraging reciprocal voluntary coordination between the various players in drug-related fields (FOPH, 2007).

The Federal Law on Narcotics and Psychotropic Substances and the federal government’s packages of measures are the framework of Swiss drug policy. Despite the demonstrable successes in drugs policy, it has not yet proved possible to incorporate the four pillar policy into legislation. A National Council committee is currently working on a draft for a partial revision of the Narcotics Act, which would lead to the policy being made part of legislation. The cannabis issue is to be excluded and dealt with instead through the popular initiative “For a rational hemp policy with effective protection of young people” (FOPH, 2007).

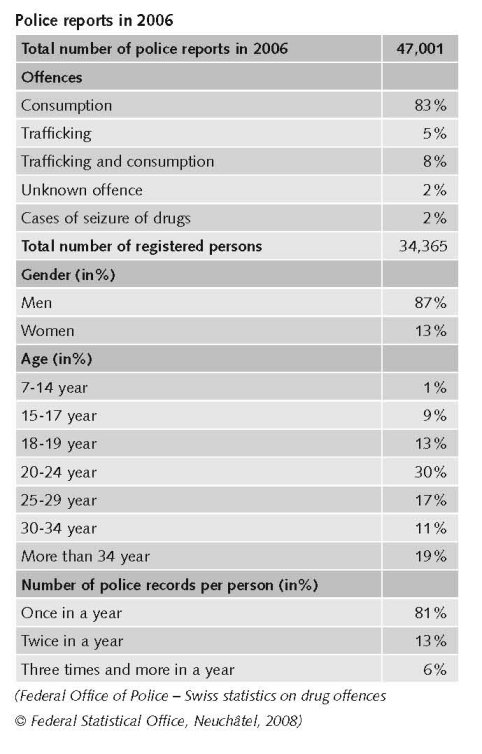

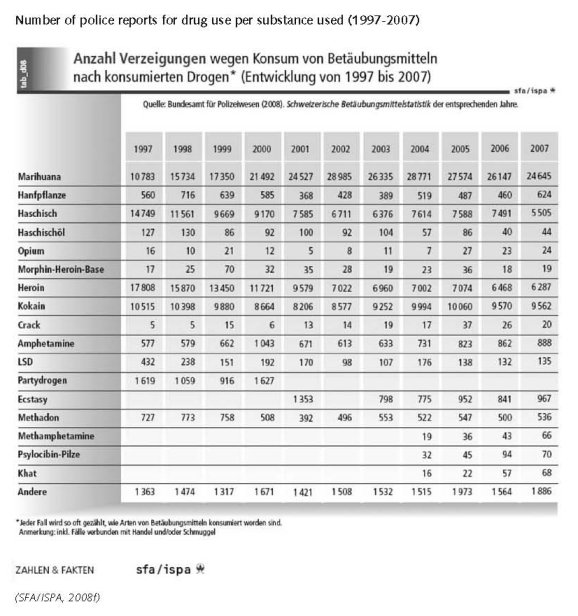

Numbers available on arrests and imprisonment for drug-law related offences

In 2007 46,957 reports for drug law offences were registered, i.e. 44 reports less in 2006 (47,001). The number of reports for consumption of illicit drugs slightly decreased in 2007 to 37,030 compared with 38,991 reports in 2006. The reports for selling illicit drugs (2,809 reports) increased in 2007 with 14.6 percent compared to 2,450 reports in 2006. Again the most reports are because of selling cocaine followed by selling marihuana and heroin (EIPD, 2008).

3.2 Supply reduction: Production, trafficking and retail

The primary goal of enforcement is to reduce supply and to fight against the trafficking of narcotics, the illegal financial transactions related to such trafficking (for example, money laundering) and organized crime. Users are not the number one target of police operations in Switzerland. Enforcement of the federal Narcotics Act is, to a large extent, the responsibility of the cantons, although the Confederation does monitor the situation closely and can call for and carry out police investigations into drug trafficking. It should be noted that canton and commune laws on policing differ and sometimes result in varying interventions. Furthermore, the drug milieu changes quickly and the methods used to fight drug-related problems are improving and adapting to this milieu. These methods include:

• Focussing enforcement activities on the manufacturing of drugs, trafficking and money laundering;

• Assigning more officers to the “drug police” and making greater use of specialists from other sectors (finance professionals);

• Intercantonal and international co-operation (agreements with police forces from neighbouring countries);

• Accelerating and improving the processing of information (networking systems and access to the police department networks from many European countries);

• Improving co-operation between the police and the private sector (banks, chemical industries, etc.);

• Improving police effectiveness and making greater use of front-line liaison workers;

• Strengthening the legal structure (for example, policing legislation, witness protection). (Collin, 2002).

Priorities of supply reduction covered by policy papers and/or law

As in most of the countries Swiss Narcotic law has followed the evolution of international treaties. For an important part Switzerland just responded to the commitments under these conventions. With respect to the production, distribution, acquisition and use of narcotics, the current legislation provides that narcotics and psychotropic substances cannot be cultivated, manufactured, prepared or sold without cantonal authorization, in accordance with conditions set by the Federal Council. In addition, a special permit from the Federal Office of Public Health is required for the importation or exportation of controlled narcotics. Furthermore, under section 8 of the Narcotics Act, the following narcotics cannot be cultivated, imported, manufactured or sold: smoking opium, heroin, hallucinogens (such as LSD) and hemp for the extraction of narcotics or hash. Section 8 also sets out the conditions governing the treatment of addicts with medical prescription of certain narcotics.

The current legislation also contains criminal provisions that apply to: anyone who unlawfully cultivates, manufactures, extracts, processes or prepares narcotics; anyone who, unless authorized, stores, ships, transports, imports, exports, provides, distributes, sells, etc., or buys, holds, possesses or otherwise acquires narcotics; and anyone who finances illicit traffic in narcotics, acts as an intermediary or encourages consumption. Section 19 offenders are liable to imprisonment or a fine depending on the seriousness, according to the Narcotics Act, of the act committed. The intentional consumption of narcotics or the commission of a section 19 offence for personal use is punishable by detention or a fine. For petty offences, the appropriate authority may stay the proceedings or waive punishment and may issue a reprimand. However, preparing narcotics for personal use or for shared use with others at no charge is not punishable where the quantities involved are minimal. Finally, anyone who persuades or attempts to persuade someone to use narcotics is also punishable by detention or a fine (Collin, 2002).

Cannabis use is illegal in Switzerland. Use is generally punished with a fine. (SFA/ISPA, 2008b) Despite the fact that users are not seen as the number one target of police operations in Switzerland 83% of the police reports for drug law offences have been for consumption (in 2006). Around 50% of these arrests are for possession of cannabis (see arrest tables above).

A planned amendment to the Narcotics Act which also provided for the decriminalisation of cannabis use sparked renewed controversy for a time in 2002. Opinion polls showed that on the issue of cannabis there was no clear majority among the public for any one policy. The amendment of the law, which would also have included the incorporation of the four pillar policy into legislation, failed to get through Parliament in 2004 (NOPH, 2007).

In a referendum of 30 November 2008 a majority of the Swiss population supported the 4 pillar drug policy (68.05%). In the same referendum a majority (63.19%) refused a legalisation of the personal consumption and production of cannabis (expert’s comments).

3.3 Demand reduction: Experimental/recreational drug use + problematic use/chronic-frequent use

Prevention measures are aimed primarily at achieving three objectives:

• To prevent drug use among individuals, especially children and youth;

• To prevent the problems and harmful effects related to drug use from spilling over onto the individual and society;

• To prevent individuals from going from casual drug use to harmful use and addiction, with all of its known consequences.

The Confederation’s prevention strategy comprises six objectives:

• To make prevention part of everyday life;

• To focus not only on drugs but also on personal resources and the strengthening of the individual’s social network;

• To create alliances between the Confederation, the cantons, the communes and private structures (family, schools, recreational associations, etc.);

• To tap into scientific research;

• To enhance early intervention;

• To ensure the viability of projects funded by the Confederation, even when the Confederation opts out.

It should be pointed out that the most notable change in prevention has been a transition from the concept that prevention was a matter of preventing someone from ever trying drugs to today’s concept of preventing the health and social problems related to drug use, thereby integrating the person’s social network and environment as well (Collin, 2002).

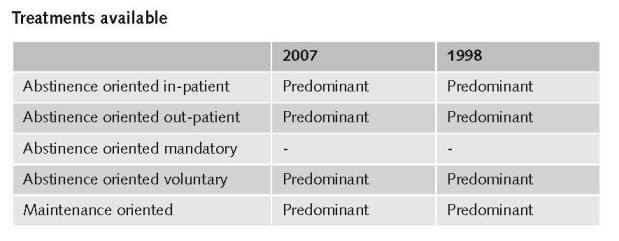

In Switzerland, there are many types of in-patient and out-patient treatment available to people suffering from drug addiction.

The objectives sought through treatment include:

• Breaking drug addicts of their habit;

• Social reintegration;

• Better physical and mental health.

(Collin, 2002)

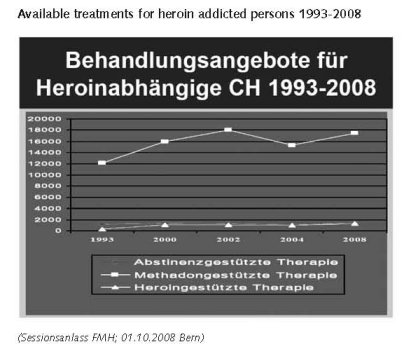

By the end of 1999, there were already 1,650 treatment spaces reserved for hard core heroin addicts in 16 treatment centres. In addition, during the same period, approximately 50% of opiate addicts (estimated to be 30,000) were being treated with medically prescribed methadone, compared to 728 individuals who were receiving this type of therapy in 1979. Those individuals addicted to one or more drugs also have access to in-patient treatment based on abstinence, to a limited number of spaces in transition centres, specialized withdrawal units or clinics, and treatment institutions, as well as out-patient consultation centres. In March 1999, there were 100 institutions providing in-patient withdrawal and rehabilitation treatment in Switzerland, for a total of 1,750 spaces (Collin, 2002).

Substitution treatment (generally methadone prescription) including psychosocial counselling is widespread. In 2005 17,236 patients received methadone substitution treatment (SFA/ISPA, 2008a).

Heroin-assisted treatment (HAT) started in Switzerland in 1994. After a pilot phase, which ended in 1996, the treatment programme was continued and is now part of the regular treatment system in Switzerland. The treatment is provided by special treatment centres (Gerlich et al., 2006).

Heroin assisted treatment has been a recognized type of therapy in Switzerland since 1999. Currently, there are 23 of these centres in the German and French speaking parts of Switzerland. (Gerlich et al., 2006) At the end of 2006 there were in total 1,308 patients in one of these 23 centres, of which two are in prison (SFA/ISPA, 2008a).

As in many other countries diversion schemes exist (since the seventies), i.e. drug treatment enforced by a court sentence as an alternative for a prison sentence (expert’s comments).

Priorities of demand reduction covered by policy papers and/or law

Drug prevention and treatment are from the start key elements in formal Swiss drug policy. They are two of the four pillars of the Swiss drug policy and as such covered in the drug policy papers (MaPaDro 1, II and III), underpinning the priorities and programmes mentioned above.

In a referendum of 30 November 2008 a majority of the Swiss population supported the 4 pillar drug policy (68.05%). This means a formal sanctioning of the strongly health-oriented approach formulated in the drug policy papers (MaPaDro 1, II and III).

3.4 Harm reduction

3.4.1 HIV and mortality

At the end of the 1980s, Switzerland witnessed a rapid increase in drug related problems. The increase of heroine consumption; the advent of open drug scenes in several cities; the rapid emergence of the AIDS epidemic among iv drug users and their degrading social condition had become increasingly visible (De Preux et al., 2004).

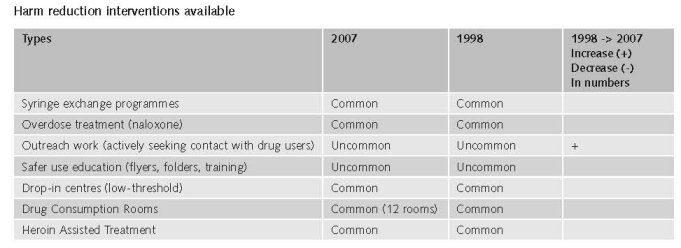

The first so-called “low threshold” coping skills institutions made their appearance in Switzerland in the mid 80s. Their purpose was to reduce the health and social risks and consequences of addiction. First and foremost, these institutions gave drug addicts a roof over their heads and were often equipped with cafeterias, showers and laundry facilities. They provided addicts with someone who would listen and talk to him or her. These facilities have evolved over the past ten years and now incorporate medical support for harm reduction (for example, prevention of AIDS and other infections, needle exchange, out-patient medical care, etc.) and social support (street work, soup kitchens, emergency shelters, low threshold centres, etc.). The Swiss Federal Office of Public Health supports many harm reduction projects as part of MaPaDro’s.

Furthermore, the cantons, communes and private institutions also provide such programs. In 1995, the SFOPH established a central service to support certain social assistance agencies, particularly those with low thresholds, and to advise the cantons, communes and private institutions on planning and funding harm reduction programs. Drug addicts have access to such programs without having to meet any particular prerequisites. The objective of these harm reduction services is to limit as much as possible the negative consequences of addiction so that the addict is able to resume a normal existence. In addition, these measures are aimed at safeguarding and even increasing the addict’s chances of breaking the drug habit (Collin, 2002).

In 2005 there were more than 200 harm reduction services in 19 cantons, including among others 38 drop-in centres (including out-patient support) 16 drug consumption facilities, 14 day care centres. There were 106 ‘sleep-in’ services, 27 outreach services, 12 specialised services for women, 7 specialised organisations in the field of safer use education (SFA/ISPA, 2008a). Needle exchange for drug addicts (and inmates), offers of employment and housing, support for sex workers and consultation services for the children of drug-addicted parents are included in several of the services named above.

Priorities of harm reduction covered by policy papers and/or law

Switzerland was one of the first countries (together with the Netherlands and the United Kingdom) which developed a formal harm reduction policy. Harm reduction is the third pillar of the Swiss drug policy and as such covered in the drug policy papers (MaPaDro 1, II and III), initiating and giving direction and support to the programmes mentioned above (IHRA, 2008).

3.4.2 Crime, societal harm, environmental damage

No data found on interventions/measures to reduce harm for society.

References

Consulted experts

R. Hämmig, Director, University Psychiatric Services Bern, Addiction Department.

Documents

Büechi M, Minder U. Swiss Drug Policy, Harm Reduction and Heroin-Supported Therapy. Vancouver, Canada, The Frasier Institute, 2001.

CIA. The World Factbook: Switzerland. Available: www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/sz.html, last accessed 10 December 2008.

Collin C. Switzerland’s Drug Policy: Prepared For The Senate Special Committee On Illegal Drugs Political and Social Affairs Division. Library of Parliament, 14 January 2002.

De Preux E, Dubois-Arber F, Zobel F. Current trends in illegal drug use and drug related health problems in Switzerland. Institut universitaire de médecine sociale et préventive, Lausanne. In SWISS MED WKLY, 2004, 134: 313–321.

EJPD (Eidgenössisches Justiz- und Polizeidepartement), Bericht 2007. Polizeiliche Kriminalstatistik PKS. Schweizerische Betäubungsmittelstatistik. EJPD, 2008.

EMCDDA, A cannabis reader: global issues and local experiences, Monograph series 8, Volume 1. European Monotoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, Lisbon, 2008.

ENCOD. The Grey Zone: Cannabis Legislation and Practice in Europe. ENCOD, 2004.

FOPH (Federal Office of Public Health). Federal Measures to Reduce Drug Related Problems (MaPaDro I 1991-1997). Bern, Swiss Confederation, 1991.

FOPH. Federal Measures to Reduce Drug Related Problems (MaPaDro II 1998-2005). Bern, Swiss Confederation, 1998.

FOPH. Switzerland’s National Drug Policy. MaPaDro III. The federal government’s third package of measures to reduce drug-related problems (MaPaDroIII 2006−2011). Bern, Swiss Confederation, 2007.

Gerlich M, Gschwend P, Uchtenhagen A, Kramer A, Rehm J. Prevalence of Hepatitis and HIV infections and vaccination rates in patients entering the heroin-assisted treatment in Switzerland between 1994 and 2002. European Journal of Epidemiology, 2006, 21: 545–549.

IHRA (International Harm Reduction Association). Global state of harm reduction 2008. Mapping the response to

drug-related HIV and hepatitis C epidemics. London, 2008.

Kubler D, Widmer T. How the Swiss Federal Drug Policy Spreads to Cantons and Cities: An Evaluation. Centre for Comparative and International Studies (CIS) Zurich, CIS news, No 8, November 2004.

Mathers BM, Degenhardt L, Phillips B, Wiessing L, Hickman M, Strathdee SA, Wodak A, Panda S, Tyndall M, Toufik A, Mattick RP, for the 2007 Reference Group to the UN on HIV and Injecting Drug Use. Global epidemiology of injecting drug use and HIV among people who inject drugs: a systematic review. Vienna, 2008.

Nordt C, Stohler R. Incidence of heroin use in Zurich, Switzerland: a treatment; case register analysis. Sessionsanlass FMH, Bern, Revision BetMG: Gründe und Folgen der 4-Säulen-Politik, A. Uchtenhagen Institut für Sucht- und Gesundheitsforschung. Lancet 2006, 367: 1830–1834.

SFA/ISPA (Schweizerische Fachstelle fur Alkohol- und andere Drogenprobleme). ZAHLEN & FAKTEN, Illegale Drogen: Behandlung. Lausanne, 2008a. Available: www.sfa-ispa.ch/DocUpload/ID_BEHANDLUNG.pdf, last accessed

15 January 2009.

SFA/ISPA. ZAHLEN & FAKTEN, Illegale Drogen: Cannabiskonsum. Lausanne, 2008b.

Available: www.sfa-ispa.ch/DocUpload/ILL_D_CANNABIS.pdf, last accessed 15 January 2009.

SFA/ISPA. ZAHLEN & FAKTEN, Illegale Drogen: Folgen des Konsums. Lausanne, 2008c.

Available: www.sfa-ispa.ch/DocUpload/ID_FOLGEN.pdf, last accessed 15 January 2009.

SFA/ISPA. ZAHLEN & FAKTEN, Illegale Drogen: Konsum. Lausanne, 2008d. Available:

www.sfa-ispa.ch/DocUpload/ID_KONSUM.pdf, last accessed 15 January 2009.

SFA/ISPA. ZAHLEN & FAKTEN, Illegale Drogen: Medikamente. Lausanne, 2008e.

Available: www.sfa-ispa.ch/DocUpload/MEDIKAMENTE.pdf, last accessed 15 January 2009.

SFA/ISPA. ZAHLEN & FAKTEN, Illegale Drogen: Widerhandlungen gegen das Betäubungsmittelgesetz, Lausanne, 2008f. Available: www.sfa-ispa.ch/DocUpload/ID_VERGEHEN.pdf, last accessed 15 January 2009.

Uchtenhagen A. The political environment of local partnerships: lessons from the Swiss experience. Research Institute for Public Health and Addiction at Zurich University A WHO collaborating Centre (3rd Conference Democracy, Cities & Drugs. Venice, november 8-10, 2007

UNDCP (United Nations International Drug Control Programme). Global Illicit Drug Trends 2000. Statistics. Vienna, UNDCP, 2001.

UNODC (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime). World Drug Report 2007. Seizures. 2007. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

UNODC. World Drug Report 2008. Vienna, UNODC, 2008.

UNODC. World Drug Report 2008. Global ATS Assessment. Vienna, UNODC, 2008a.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|