Appendix to report 4: country reports SWEDEN

| Reports - A Report on Global Illicit Drugs Markets 1998-2007 |

Drug Abuse

SWEDEN

1 General information

Location:

Northern Europe, bordering the Baltic Sea, Gulf of Bothnia, Kattegat, and Skagerrak, between Finland and Norway

Area:

449,964 sq km

Land boundaries/coastline:

2,233 km / 3,218 km

Border countries:

Finland 614 km, Norway 1,619 km

Population:

9,045,389 (July 2008 est.)

Age structure:

0-14 years: 16% (male 745,110/female 703,857)

15-64 years: 65.6% (male 3,008,148/female 2,928,930)

65 years and over: 18.3% (male 729,500/female 929,844) (2008 est.)

Administrative divisions:

21 counties

GDP (purchasing power parity):

$338.5 billion (2007 est.)

GDP (official exchange rate):

$455.3 billion (2007 est.)

GDP- per capita (PPP):

$37,500 (2007 est.) (CIA World Factbook)

Drug research

The main organisations involved in conducting drug-related research are university departments, although non-governmental and governmental organisations are also relevant partners. Several channels for disseminating drug-related research findings are available in Sweden, ranging from scientific journals, to dedicated websites, reports, manuals and conferences. (Country overview)

Main drug-related problems

The main drug problem in Sweden is consumption followed by trafficking. Production plays no significant role.

2 Drug problems

2.1 Drug supply

2.1.1 Production

Production sites for drugs are rare in Sweden. On average less than one simple site for manufacturing of drugs (kitchen lab) is found annually over the last ten years. However, in 2008 about 20 full scale cultivations of marijuana have been disclosed in the southern part of Sweden as reported in the 2008 national report (National Report, 2008). This is a totally new development.

2.1.2 Trafficking

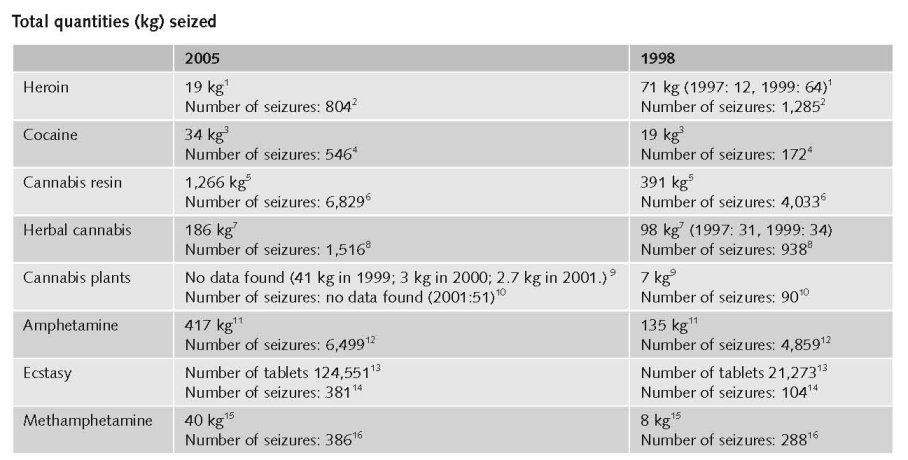

1. Quantities (kg) of heroin seized, 1995 to 2005 - EMCDDA Table SZR-8-SEIZURE-HEROIN-QUANTITY.htm

2. Number of heroin seizures, 1995 to 2005 - EMCDDA Table SZR-7-SEIZURE-HEROIN-NUMBER.htm

3. Quantities (kg) of cocaine seized, 1995 to 2005 - EMCDDA Table SZR-10-SEIZURE-COCAINE-QUANTITY.htm

4. Number of cocaine seizures, 1995 to 2005 - EMCDDA Table SZR-9-SEIZURE-COCAINE-NUMBER.htm

5. Quantities (kg) of cannabis resin seized, 1995 to 2005 - EMCDDA Table SZR-2-CANNABIS-QUANTITY.htm

6. Number of Cannabis resin seizures, 1995 to 2005 - EMCDDA Table SZR-1-SEIZURE-CANNABIS-NUMBER.htm

7. Quantities (kg) of herbal cannabis seized, 1995 to 2005 - EMCDDA Table SZR-4-SEIZURE-HERBAL-CANNABIS-QUANTITY.htm

8. Number of herbal cannabis seizures, 1995 to 2005 - EMCDDA Table SZR-3-SEIZURE-HERBAL-CANNABIS-NUMBER.htm

9. Quantities (number of plants) of cannabis plants seized, 1995 to 2005 - EMCDDA Table SZR-6-SEIZURE-CANNABIS-PLANTS-QUANTITY.htm

10. Number of seizures of cannabis plants, 1995 to 2005 - EMCDDA Table SZR-5-SEIZURE-CANNABIS-PLANTS-NUMBER.htm

11. Quantities (kg) of amphetamine seized, 1995 to 2005 - EMCDDA Table SZR-12-SEIZURE-AMPHETAMINES-QUANTITY.htm

12. Number of amphetamine seizures, 1995 to 2005 - EMCDDA Table SZR-11-SEIZURE-AMPHETAMINE-NUMBER.htm

13. Quantities (tablets) of ecstasy seized, 1995 to 2005 - EMCDDA Table SZR-14-SEIZURE-XTC-QUANTITY.htm

14. Number of ecstasy seizures, 1995 to 2005 - EMCDDA Table SZR-13-SEIZURE-XTC-NUMBER.htm

15. Quantities (kg) of Methamphetamine seized, 2001 to 2005 - EMCDDA Table SZR-18-SEIZURE-METHAMPH-QUANTITY.htm

16. Number of Methamphetamine seizures, 2001 to 2005 - EMCDDA Table SZR-17-SEIZURE-METHAMPH-NUMBER.htm

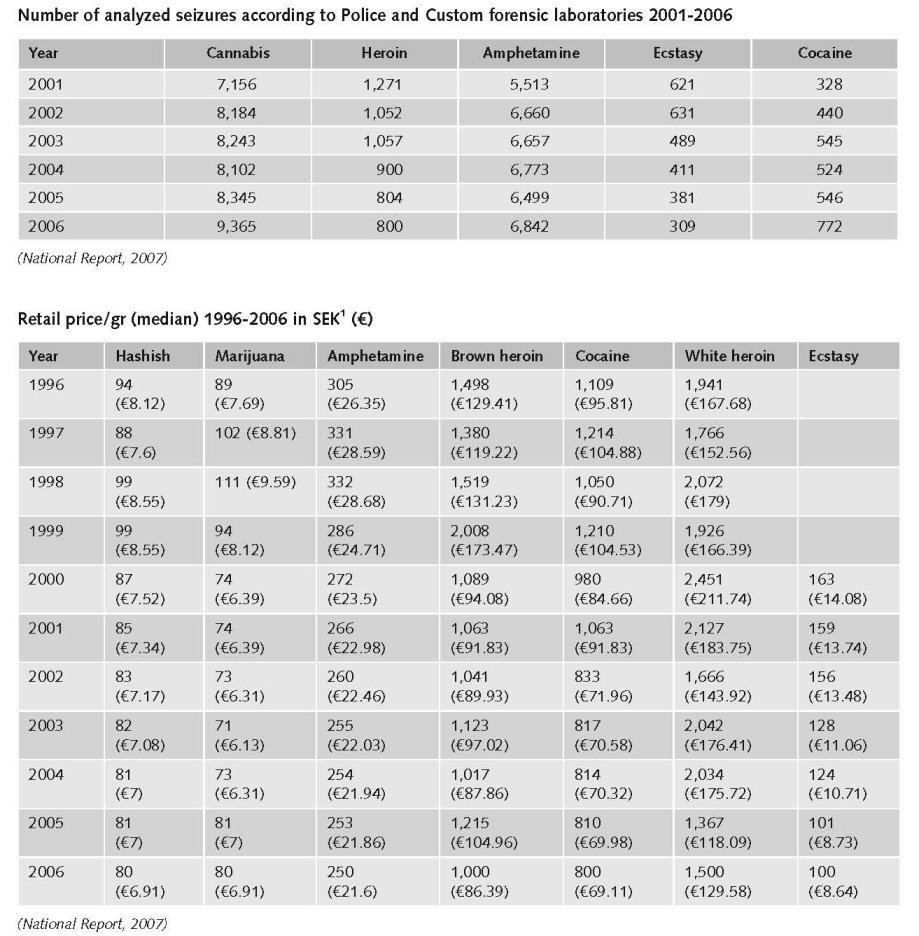

According to police reports, the illegal drug most frequently seized in Sweden is cannabis, accounting for 50.6% of all drug seizures in 2006 (Country overview).

In 2006, the total number of drugs seizures was 18,497. With regards to quantities in 2006, the Swedish customs seized the largest amounts ever with a total of 1,358 kg of cocaine and 103 kg of heroin. Another significant quantitative seizure in 2006 was ecstasy, with a total quantity of 291,385 tablets. The quantity of seized amphetamine in 2006 was 422 kg, an amount lower than for 2005 but higher than 2004. The seized quantities of cannabis in 2006 are the lowest quantity seized so far this century. In 2006, the seized quantity of 6.5 tonnes of khat is less than the peak year of 2004, when h 9.3 tonnes were seized by customs and police, and khat seizures are now on par with the level of 2003 (Country overview).

Additional information

Cannabis seized in Sweden originates from Morocco and it is smuggled through Spain and more recently, through Portugal. Cannabis is also trafficked by tourists travelling between Sweden and Denmark, as the prices for cannabis are lower in Denmark. Amphetamine mostly originates from the Netherlands, Belgium, Estonia, Poland and Lithuania, with brown heroin originating from Afghanistan (Country overview).

1 1 SEK = €0.09. Exchange rate 15 February 2009.

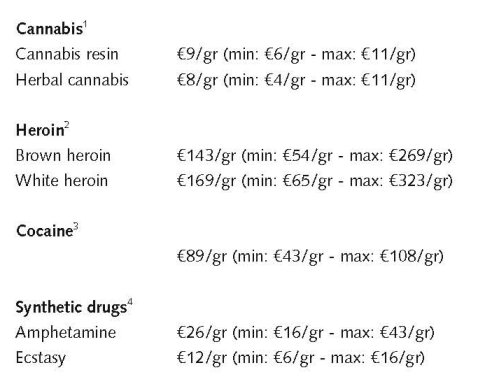

Estimated retail value

in 2005:

1. Price of cannabis at retail level, 2005, EMCDDA Table PPP-1 Part (i)-PRICE-CANNABIS.htm

2. Price of heroin at retail level, 2005, EMCDDA Table PPP-2 Part (i)-PRICE-HEROIN.htm

3. Price of cocaine products at retail level, 2005, EMCDDA Table PPP-3 Part (i)-PRICE-COCAINE.htm

4. Price of synthetic drugs at retail level, 2005, EMCDDA Table PPP-4 Part (i)-PRICE-SYNTHETIC.htm

Data regarding prices of drugs at street level are reported by the Swedish Council for Information on Alcohol and Other Drugs (CAN). In 2006 CAN reported that there was a decrease in the average price of hashish and amphetamines in the last decade. In 1996, the average price for hashish was €10/gram whereas in 2006, the average price was €9/gram. On the other hand, in 1996, the average price for amphetamines was €33/gram whereas, in 2006 the average price was €22/gram (Country overview).

2.2 Drug Demand

2.2.1 Experimental/recreational drug users in the general population

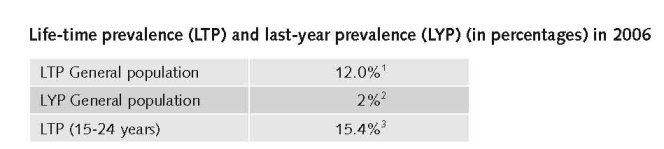

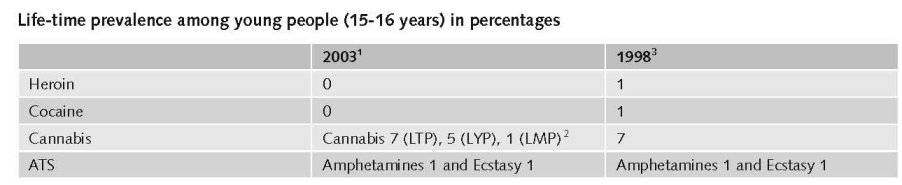

In 2005, a public health survey was conducted among 16–84-year olds. Results for 16–64-year olds show a lifetime prevalence for cannabis rate of 12% (14.7% for men, 9% for women) slightly lower than reported in 2004. School surveys on drug use have been carried out in Sweden annually since 1971 by the Swedish Council for Information on Alcohol and other Drugs (CAN). Reported lifetime prevalence for illegal drugs among students between the ages of 15–16 was highest in the 1970s (15%) and subsequently dropped to 4% in 1985 and 5% in 1986, reaching its lowest level in 1989 (4%). Since then the rate rose again to 9% in 2001, before dropping to 6% in 2006. In the most recent survey (2006), last month prevalence was 3% for boys and girls, which was slightly higher than reported in 2003 (2% for both genders). As in most European countries, cannabis was the illegal drug students had most frequently experimented with in their lifetime, with results indicating 5% for students aged 15–16 years. Lifetime prevalence in 2006 of solvents and inhalants was 6%, and 1% for ecstasy and amphetamines (Country overview).

1. Lifetime prevalence of drug use among all adults (aged 15 to 64 years old) in nationwide surveys among the general population, EMCDDA Table GPS-8-LIFETIME-15-64.htm

2. Last year prevalence (percentage) of drug use among all adults (aged 15 to 64 years old) in nationwide surveys among the general population: last survey available for each Member State, EMCDDA Table GPS-10-LAST-YEAR-15-64.htm

3. Lifetime prevalence of drug use among the age group of 15 to 24 years old in nationwide surveys among the general population. Last survey available for each Member State, EMCDDA Table GPS-17-LIFETIME-15-24.htm

There are no detailed data for recent data on LTP and LYP of cannabis use in the general population and among young people (15-14 years).

1. Recent school surveys (2003-2005): lifetime prevalence (percentage) of psychoactive substance use among students aged 15-16 years old, EMCDDA Table EYE-01-LIFETIME PREVALENCE-15-16.htm

2. ESPAD 2003 school surveys: lifetime (LTP), last year (LYP) and last month (LMP) prevalence of cannabis use among students 15–16 years - EMCDDA Table EYE-05 Part (i)-CANNABIS-15-16.htm

3. School surveys: lifetime prevalence (percentage) of psychoactive substance use among students aged 15-16 years old, EMCDDA Table EYE-03-LIFETIME PREVALENCE-15-16.htm

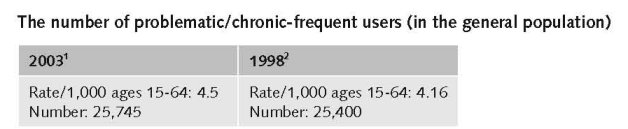

2.2.2 Problematic drug users/chronic and frequent drug users

The most recent estimate (2003) on the number of problem drug users from a governmental report presented in October 2005 was close to 26,000 (2.9 drug users per 10,000 inhabitants). According to the report, the number of PDUs has been more-or-less constant over the years since 1998, with a peak in 2001 of close to 28,000 problem drug users. Problem drug use in Sweden is dominated by heroin and amphetamines. In a national survey in 1998, it was found that 73% of PDUs have used amphetamines during the last 12 months, and that 32% reported amphetamines as their primary drug. In the previous survey in 1992 these figures were 82% and 48% respectively (Country overview).

1. Prevalence of problem drug use at national level: summary table, 2001-2005, rate per 1,000 aged 15-64 - Overall problem drug use, EMCDDA Table PDU-1 Part (i)-NATIONAL-OVERALL-15-64.htm

2. Prevalence of problem drug use at national level: full listing of studies, rate per 1,000 aged 15-64 - Overall problem drug use, EMCDDA Table PDU-102 Part (i)-NATIONAL-OVERALL-15-64.htm

No data found on the number of injecting drug users (in the general population) and among younger people (<20 years).

2.3 Drug related Harm

2.3.1 HIV infections and mortality (drug related deaths)

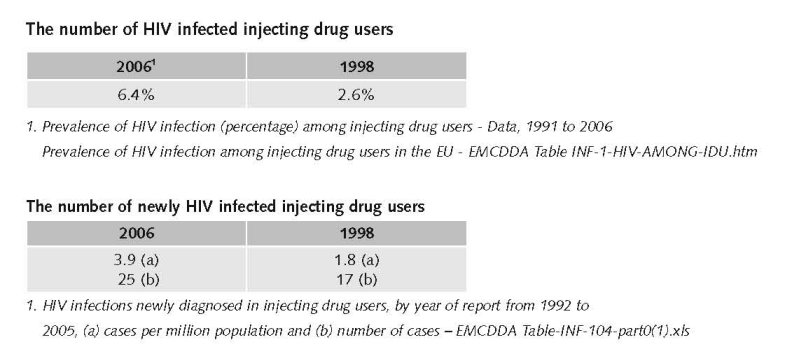

In 2006, the number of notified cases with acute hepatitis B infections through intravenous drug use was 63, or 47% of all notified cases with a known transmission route (n=162). Over time, a shift in age dispersion can be noticed, with more cases in the younger age groups. Approximately 22% of notified cases during 2006 were found in the age group 15–24 (Country overview).

35 IDUs were reported to have contracted HIV during 2006. During the second half of 2006, an increase in reported HIV cases among IDUs was observed (Country overview).

Additional information

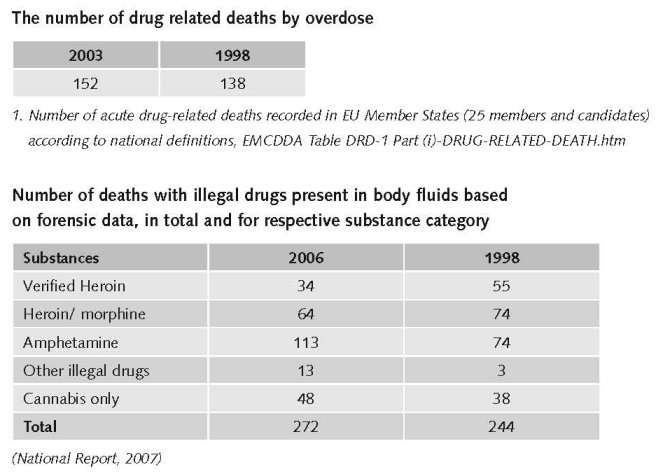

According to the EMCDDA standard definition (which includes acute deaths directly related to drug consumption or overdoses), there were 135 drug-related deaths in 2004 (152 in 2003). Since 1990, the data show an increase in drug-related deaths, which peaked in 2000 and appears to have been declining since then. It must be noted, however, that changes in the registrations system should be taken into consideration when interpreting the data. The change in the ICD system was introduced in 1997: There have been no relevant changes in the registration system since 1997, and this also needs to be taken into account when looking at the trend line for drug-related deaths (Country overview).

Apart from the Cause of Death Register, a special local register on drug-related mortality operated between 1985 and 1996. It consisted of information from all deaths investigated by the Department of Forensic Medicine in the Stockholm reception area (covering counties of Stockholm, Södermanland and Götland). The data between 1985 and 1996 also suggest an increase in the number of drug related deaths. Furthermore, the 1994 – 2006 data from the forensic toxicity register also suggest an increase in the number of drug related deaths in the last ten years (Country overview).

2.3.2 Drug related crime or (societal) harm

No information found on harm for society.

3 Drug policy

3.1 General information

3.1.1 Policy expenditures

The first trial to estimate expenditures for drug use was performed by The Swedish National Audit Bureau, 1993. The expenditures include health care, treatment, probation care, social service, the penal system, the judiciary system and social welfare system. The conclusion of this early study was built upon an estimated number of abusers of 17,000. The public costs was estimated to €330 million 1991 (expert’s comments).

Fölster & Säfsbäck made an estimation of the costs excluding the health care sector but including police and custom control. Their estimations built upon the same number of abusers as the 1993 study and they ended up with a sum of €660 million the year 1996 (expert’s comments).

In a Governmental investigation (Narkotikakommissionen 2000) another estimate of the public costs was made. In this investigation the number of abusers was assumed to be approximately the same number as before, i.e. 17,000. The estimate of public costs landed on €847 million the year 1999 (expert’s comments).

In the only study published in a scientific journal Ramstedt calculated the public expenditures for the drug policy 2002 to between €495-1385 million (Ramstedt, 2006). In that sum costs for the primary health care sector are approximations. Ramstedt calculated the total costs for each institution dealing with abusers and then summed those. Earlier studies calculated the costs assigned to each abuser and multiplied with the number of abusers (expert’s comments).

By updating the costs calculated by Ramstedt using the consumer price index an approximation is that the cost of the Swedish drug policy 2007 is €528 -1 474 million (expert’s comments).

In a study performed by Statistics Sweden an estimate of the illegal activities in the Swedish national accounts were calculated. The number of addicted persons was estimated to 28,000 year 2001. The number of addicted persons 2007 is approximately 26,000. An extrapolation by using linear regression of the costs of purchasing drugs, grounded on the relation to gross national product of earlier years, can be calculated to be €176 million. This sum only includes costs for trading and the contribution of trading with illegal drugs to the gross domestic product. Public expenditures are not included in this sum (National Report, 2008).

Developing demand reduction is financed with central-government funds is being carried out in Sweden’s municipalities. About €21 million of central-government development funds has been allocated among municipalities by county administrative boards in 2006. Of these funds, around:

• SEK 23 million (€2,275,990) (SEK 22 million (€2,177,810) in 2005) has been allocated to out-patient projects targeting young people or adults with addiction problems;

• SEK 93 million (€9,205,260) (SEK 74 million (€7,326,900) in 2005) has been allocated to alcohol and drug prevention, of which:

- SEK 55 million (€5,446,440) to preventive work (SEK 53 million (€5,249,470) in 2005);

- SEK 34.5 million (€3,415,570) to early interventions for children in families where substance abuse and violence between adults occur (SEK 18 million (€1,781,190) in 2005);

- SEK 3.5 million (€346,233) to interventions for women with addiction problems who are victims of violence (SEK 3 million (€296,898) in 2005);

• SEK 93 million (€9,205,260) (SEK 40 million (€3,956,910) in 2005) has been allocated to supporting the development of services for heavy addicts (National report, 2007).

Establishing a national action plan on drugs with a corresponding funding has implied that responses to the actual situation have been possible to launch. It has also been a period of formulating agendas and to lay down broad outlines for responses to various aspects of the drug problem. The cost for the municipalities for persons with alcohol and/or substance abuse has increased by 7.7% between 2000 and 2005 and housing per se with close to 65% over the same period according to the annual situation report from the NBHW on individual- and family care50 (National Report, 2007).

The national action plan on drugs (2002–2005, 2006–2010) has led to an increased support for drug related research. In the period 2002–2006 the government has supported just over 100 different research projects in the drugs at a cost of €9.6 million (National Report, 2007).

Expenditures increased during the past ten years

The expenditures have increased for all areas as a consequence of the national action plans on drugs. As presented above, the efforts to monitor drug related expenditures are not consistent and the methods differ. It is thus not feasible to specify the development for the three areas (expert’s comments).

3.1.2 Other general indicators

Sweden has two separate plans in relation to drugs, one for alcohol and the other for drugs, which were adopted together: the ‘National alcohol and drug action plans 2006–10’. The drug action plan is comprehensive, focuses on illegal drugs and covers prevention, treatment and rehabilitation, and supply reduction. Its purpose is to establish a direction for drug preventive work and to guide and improve social efforts to tackle drugs. Implementation is the responsibility of local, regional and national actors. The overall goals of the drug policy are: reducing the recruitment of new drug abusers; inducing more drug abusers to kick the habit; and reducing the supply of drugs. This drug policy is combined with other social policies policy preventing unemployment, social exclusion, and so on (Country overview).

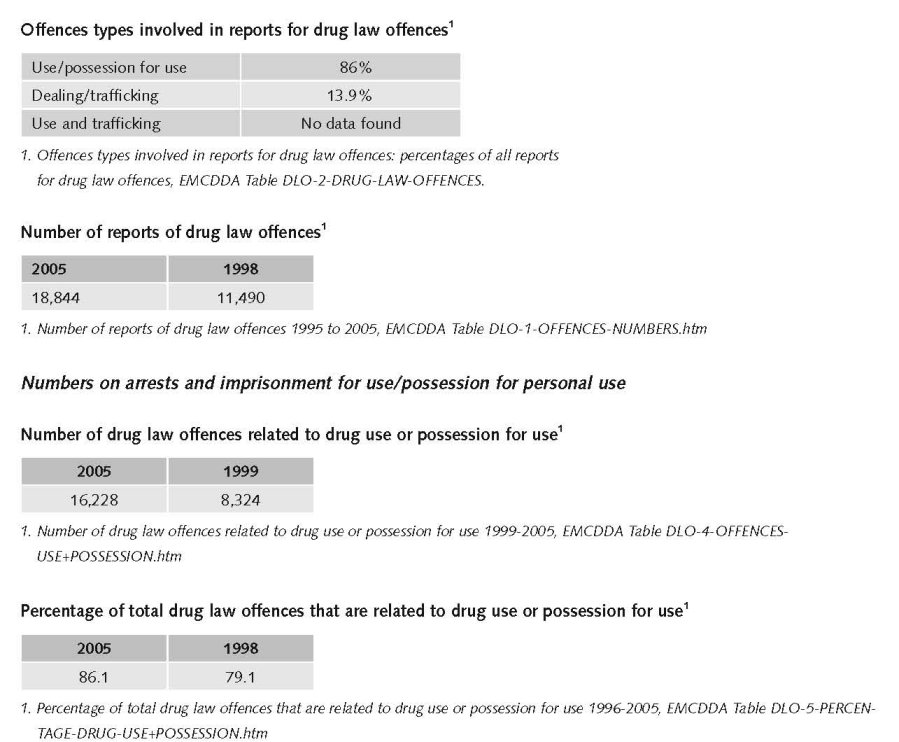

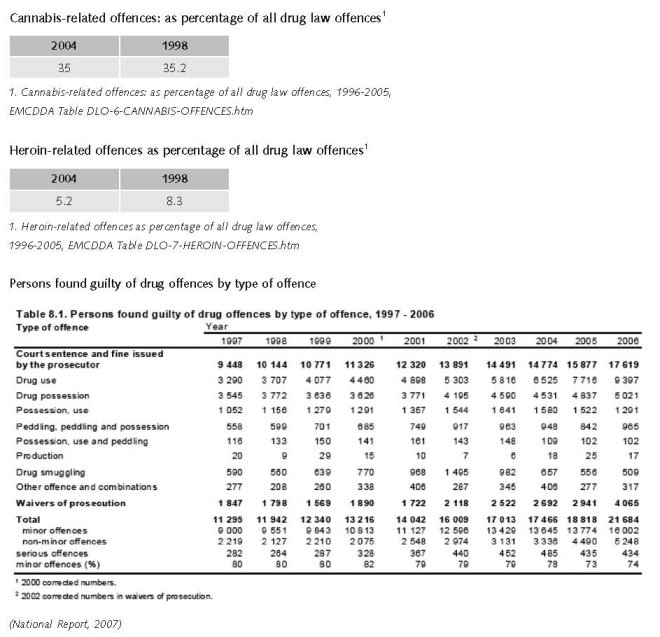

Numbers on arrests and imprisonment for drug-law related offences

Drug offences continue to increase and over the last ten years an average annual increase of close to 7% is noted. Drug use (53%) and drug possession (28%) were the two most common offences committed by persons convicted of drug offences in 2006 (National Report, 2007).

3.2 Supply reduction: Production, trafficking and retail

Main focus in Sweden is on measures against trafficking, retail and possession.

Priorities of drug policy covered by policy papers and/or law

Priorities of drug policy on drug production, supply and trafficking are covered by drug policy papers, but not broken down for specific type of drugs (expert’s comments).

Supply reduction is one of the three pillars in the action plans on drugs.

In principle there were no changes in the past ten years but the first national action plan on drugs 2002 – 2005 clearly expressed this objective that also remained unchanged in the present action plan 2006 – 2010 (expert’s comments).

The use and possession of illegal drugs are criminal offences under the Narcotic Drugs Punishment Act. Use and possession are punished according to three degrees of severity for drug offences: minor, ordinary and serious. The degree of offence takes into consideration the nature and quantity of drugs and other circumstances. Penalties for minor drug offences consist of fines or up to six months’ imprisonment, for ordinary drug offences up to three years, and for serious drug offences two to ten years’ imprisonment, with penalties of up to 18 years possible for recidivists. The penalties for drug trafficking offences regulated in the Law on Penalties for Smuggling are identical with the penalties provided in the Narcotic Drugs Punishment Act (Country overview).

Sweden also operates a system of classifying substances as ‘Goods dangerous to health’, which may be used to rapidly control goods that, by reason of their innate characteristics, entail a danger to human life or health and are being used, or can be assumed to be used, for the purpose of intoxication or other influence. The import of such goods is punished in the same way as for drugs offences, whereas their possession and transfer will be punished by up to one year imprisonment (Country overview).

Legal changes during the past ten years

The act and ordinance on “goods dangerous to health” came into force 1999. Simultaneously there was a change in the narcotic drugs punishment act with the implication that “dependence causing properties” was changed to “dependence causing properties or euphoric effects” (expert’s comments).

3.3 Demand reduction: Experimental/recreational drug use + problematic use/chronic-frequent use

Additional information

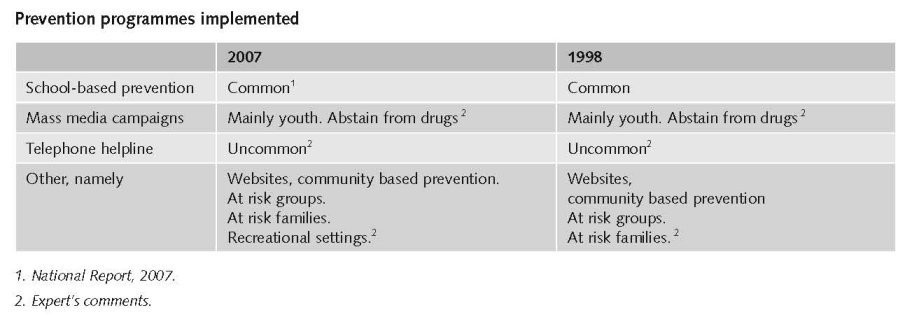

The main features of prevention policy in Sweden are a wide range of detailed objectives and actions covering universal as well as selective prevention. The key focus is on social skills and social inclusion. Implementation of curricular school-based prevention programmes is common, but very little is known about the coverage, quality and contents of these programmes (Country overview).

Quality control of school-based prevention is not yet developed and monitoring systems (that is, databases) do not exist. Selective prevention is sometimes targeted at ethnic groups and has an only recently acknowledged political and practical relevance. Selective prevention in recreational settings is carried out by municipalities and the entertainment industry, with a focus on norm-setting and controlling approaches. Special characteristics of the prevention culture in Sweden within the European context are a strong local community-based delivery of prevention, the absence of monitoring systems for prevention, and comprehensive detailed planning of future prevention activities in the national action plan. Prevention in recreational settings in Sweden shows considerable promise (Country overview).

Over the last years a shift in the drug preventive work towards structural and policy issues is seen, in contrast to the former efforts on information and campaigns. The National Action Plan (introduced in 2002) emphasises that it is important that drug issues are given high political priority in the local society and that all efforts should be based on methods that are evaluated (National Report, 2003).

The implementation of this national action plan on drugs is run by the national drugs policy coordinator (NDPCo). 2003 and 2004 show a marked increase in drug prevention activities, mainly due to initiatives from the coordinator. By Government support the majority of the 290 local authorities in Sweden have been able to appoint local drug 5 coordinators for the alcohol- and drug preventive work in order to strengthen the local mobilisation (National Report, 2004).

In 2006, data on treatment demand was reported by a total of 222 treatment centres comprising of 92 out-patient treatment centres, 98 in-patient treatment centres and 32 treatment centres within the prison setting. In 2006, a total of 6,920 clients entered treatment, of whom 1,426 were new treatment clients (Country overview).

The 2006 treatment demand data suggests that 34.9% of all clients entering treatment reported amphetamines as the primary drug, followed by 24.4% for opioids and 17% for cannabis. Among new treatment clients, 30.4% reported that cannabis was the primary drug, followed by amphetamines at 26.7% and opioids at 19.1% (Country overview).

In 2006, 40% of all clients entering treatment were aged more than 35 years. A lower age distribution was reported among new treatment clients, with 40% under the age of 25 years. As regards gender distribution among all clients entering treatment, 76% were male whereas 24% were female. A slightly different gender distribution was reported among new clients entering treatment, with 64% for males and 36% for females (Country overview).

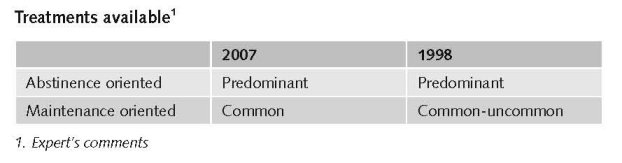

The social services in the municipalities are responsible for the treatment of problem drug use, even if the cases require medical treatment. Thus most treatment for problem drug use is organised outside hospitals by the social services. Most treatment is drug-free and the vast majority is delivered in out-patient settings. There are treatment facilities specifically for problem drug users, but as a rule of thumb treatment of problem drug use takes place alongside treatment of alcohol and/or other addictions (Country overview).

The Medical Products Agency’s Code Statutes LVFS 2004: 15 stipulate that only treatment centres can initiate, and should be predominantly involved in, substitution treatment. Methadone introduced in 1966 and buprenorphine introduced in 1999 are the only officially recognised pharmaceutical substances for substitution treatment. Substitution treatment with methadone has always been subject to strict regulations. Since the new guidelines for substitution treatment came into force in January 2005, provision of medically-assisted treatment has increased. In 2006, a total of 2,739 clients were in substitution treatment, 1,270 of whom were on methadone. In Sweden, there are about 60 treatment units at hospitals used in substitution treatment (Country overview).

Methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) was introduced in 1967, high-dosage buprenorphine treatment (HDBT) in 1999 (Year of introduction of methadone maintenance treatment (MMT), high-dosage buprenorphine treatment (HDBT) and heroin-assisted treatment, including trials’’ EMCDDA Table HSR-8-METHADONE-INTRODUCTION.htm)

National guidelines for the treatment of alcohol and drug abuse came into force in 2007 (National Report, 2007).

The guidelines are directed towards both the social service and the health- and medical sector with the aim to develop a higher clearness and uniformity in the care- and treatment sector. Issues covered by the guidelines are inter alia detection and early intervention, instruments for judgement and documentation, psychosocial treatment and medically assisted treatment, pregnant women, dual diagnosis (National Report, 2007).

The NDPCo has put forward a detailed proposal for the improvement of the treatment of abusers of heroin and other opiates32 – among other things the possibility of economic sanctions against counties that do not offer treatment. The NDPCo also propose the establishment of an “ombudsman” to care for opiate abusers rights to treatment (National Report, 2007).

Law or other legal provisions/arrangements

In Sweden, social legislation determines that social services in the local community are responsible for the implementation of treatment of problem drug use. Treatment is mainly delivered by public institutions, followed by private and non-governmental organisations. Funding of substance treatment, including treatment delivered by NGOs, is provided by the public budget of the municipalities, which are also subsidised by state funds. In the case of NGOs, public funding is handled by the National Board of Health and Welfare and is based on applications from the NGOs (Country overview).

3.4 Harm reduction

3.4.1 HIV and mortality

Additional information

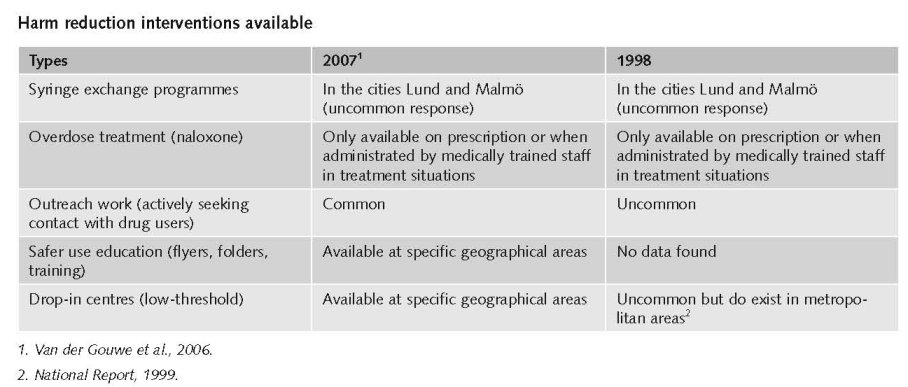

Up until 2006, two needle exchange programmes have existed in southern Sweden (Lund since 1986 and Malmö since 1987). These programmes also assist drug users with other medical/social support and refer them to drug-free treatment within the Social Services. Pharmacies are not entitled to sell needles/syringes (Country overview).

Priorities of harm reduction covered by policy papers and/or law

The ‘National action plan on drugs (2002–05)’ does not use the phrase harm reduction measures and overall the plan follows a restrictive policy. Even though the Drugs Commission in Sweden has commented that drug users can be offered help without the requirement of an immediate and/or long-lasting drug-free life, the Commission advises against legal prescription of heroin, safe injection rooms and other low-threshold programmes. As of 2006, the Swedish government introduced a law which in effect allows each of the 21 regions in Sweden to introduce needle exchange programmes (Country overview).

3.4.2 Crime, societal harm, environmental damage

No information found on interventions/measures to reduce harm for society. However, improved treatment and rehabilitation programmes as a consequence of the drug policy priorities contribute to reduce the harm for society.

References

Consulted experts

A. Bessö, Department for Alcohol and Narcotics, Swedish National Institute of Public Health.

Documents

CIA. The World Factbook: Sweden. Available: www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/sw.html, last accessed 10 December 2008.

Country overview: Sweden. Available: www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/country-overview/sv, last accessed 10 December 2008.

National Report to the EMCDDA, Sweden, 1999.

National Report to the EMCDDA, Sweden, 2003.

National Report to the EMCDDA, Sweden, 2004.

National Report to the EMCDDA, Sweden, 2007.

Van der Gouwe D, Gallà M, Van Gageldonk A, Croes E, Engelhardt J, Van Laar M, Buster M. Prevention and reduction of health-related harm associated with drug dependence: an inventory of policies, evidence and practices in the EU relevant to the implementation of the Council Recommendation of 18 June 2003. Utrecht, Trimbos Institute, 2006.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|