Appendix to report 4: country reports RUSSIAN FEDERATION

| Reports - A Report on Global Illicit Drugs Markets 1998-2007 |

Drug Abuse

RUSSIAN FEDERATION

1 General information

Location:

Northern Asia (the area west of the Urals is considered part of Europe), bordering the Arctic Ocean, between Europe and the North Pacific Ocean

Area:

17,075,200 sq km

Land boundaries/coastline:

20,241.5 km/ 37,653 km

Border countries:

Azerbaijan 284 km, Belarus 959 km, China (southeast) 3,605 km, China (south) 40 km, Estonia 290 km, Finland 1,313 km, Georgia 723 km, Kazakhstan 6,846 km, North Korea 17.5 km, Latvia 292 km, Lithuania (Kaliningrad Oblast) 227 km, Mongolia 3,441 km, Norway 196 km, Poland (Kaliningrad Oblast) 432 km, Ukraine 1,576 km

Population:

140,702,096 (July 2008 est.)

Age structure:

0-14 years: 14.6% (male 10,577,858/female 10,033,254)

15-64 years: 71.2% (male 48,187,807/female 52,045,102)

65 years and over: 14.1% (male 6,162,400/female 13,695,673) (2008 est.)

Administrative divisions:

46 oblasts, 21 republics, 4 autonomous okrugs, 9 krays, 2 federal cities, and 1 autonomous oblast

GDP (purchasing power parity):

$2.097 trillion (2007 est.)

GDP (official exchange rate):

$1.29 trillion (2007 est.)

GDP- per capita (PPP):

$14,800 (2007 est.) (CIA The World Factbook)

Drug research

There is one major addiction research centre (epidemiology and monitoring) in the Russian Federation, the Russian Narcological Research Centre/ Research Institute of Addictions which is among others also participating in the ESPAD). A number of universities and experts working at universities are also engaged in research regarding drug use and drug-related matters (such as Dr. Mendelevich from the Institute for Research of Problems of Mental Health, Kazan State Medical University). A number of international bodies, such as UNODC, UNAIDS, WHO are also involved in monitoring drug trends or trends in infectious diseases related to (injecting) drug use.

Main drug-related problems

The Russian Federation is facing substantial drug consumption problems. In particular opiates (mainly heroin and homemade opium poppy derivates) and ATS (especially vint, the Russian equivalent of methamphetamine) are consumed widely. The Russian Federation is an important producer of amphetamine-type stimulants and cannabis. It is a transit country for heroin (from Afghanistan to Central and Northern Europe).

As the world’s largest country the Russian Federation incorporates many different markets: usage/prevalence/availability of various types of drugs differ largely between the regions.

2 Drug problems

2.1 Drug supply

2.1.1 Production

In the Russian Federation, in recent years the number opium seizures and the amount of opium seized have decreased. Heroin seizures have increased. Heroin comes in “ready” form from Afghanistan. Heroin production in the Russian Federation is very limited.

Other opiates are widely produced in the Russian Federation, especially home-made products such as khanka (chorny) and mak, which are basically cheap and dirty opium derivates. Both derivates are not strong in effect and they are not trafficked abroad at all, and produced for local/ domestic market solely (expert’s comments).

Very low levels of cultivation of opium poppy continue to take place in many other regions and countries such as the Russian Federation, Ukraine, Central Asia, the Caucasus Region, other CIS countries, Balkan countries, Baltic countries, Egypt, Lebanon and Iraq (UNODC, 2008).

The Russian Federation isrol a country for production of drugs for the international drug markets.

It is estimated that there is about 1,000,000 hectares of wild cannabis in the Russian Federation (UNODC, 2008b). The THC level of wild cannabis is quite low. The Russian Federation is among the largest cannabis producers in Europe (2,500 mt excl. Central Asia; 4,850 mt incl. Central Asia) besides other the C.I.S countries, notably Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan (UNODC, 2008).

There is a large domestic market in the Russian Federation for amphetamine-type stimulants. The main ATS is ‘vint’ (similar to methamphetamine or ‘pervetine’, produced and used in Czech Republic) and is a homemade stimulant prepared by people themselves, but is also manufactured in (meth-)amphetamine laboratories.

The important role of the Russian Federation in manufacturing ATS is evidenced by the relatively large number of dismantled production facilities, though the information reported differs substantially. The INCB reports that in 2006 Russian authorities detected 1,700 facilities used to illicitly manufacture synthetic drugs, including 136 chemical laboratories (INCB, 2008). UNODC reports that in 2006 526 amphetamine laboratories were dismantled in the Russian Federation, 57% of the total dismantled in Europe (UNODC, 2008).

Besides vint there is also some production of ecstasy in the Russian Federation (e.g. Saint Petersburg), but ecstasy is mainly being imported from the Netherlands, Poland, and Baltic States, especially Lithuania (UNODC, 2008a).

In 2007, there were 1,486 cases reported of illicit production of drugs that were dismantled by the Federal Drug Control Service (FDCS). Most of these laboratories were kitchen laboratories, no big industries. The market for ATS in the Russian Federation is big, but the laboratories where they are manufactured are usually small and produce for local markets (expert’s comments).

UNODC reports for seizures of illicit laboratories in the Russian Federation that in 2005 417 labs for cannabis oil (63.491 kg) and 601 cannabis herb labs (2,323.000 kg) were dismantled; in 2006 380 cannabis resin labs (41.174 kg) were dismantled; this is half of the total number of dismantled labs in these 2 years in the total of Europe (UNODC, 2008).

In 2005, 8 morphine labs (0.004 kg) and 346 opium labs (2.223 kg) were dismantled; in 2006 186 opium labs (0.198 kg), 26 heroin labs (0.048 kg) and 13 morphine labs (0.565 kg) were dismantled (UNODC, 2008).

Finally, another 1,936 unspecified labs were dismantled in 2005 in the Russian Federation (UNODC, 2008).

2.1.2 Trafficking

There was a decrease (>10%) in trafficking of heroin and morphine in the Russian Federation in 2006. And this holds true for trafficking of cocaine as well. Trafficking of cannabis resin, in amphetamines and in ecstasy also decreased (>10%). (UNODC, 2008)

In 2006, 619 opiates producing laboratories were destroyed. Afghanistan (269), the Russian Federation (225) and the Republic of Moldova (112) reported seizing and dismantling the majority of these labs. Laboratories in the Russian Federation and the Republic of Moldova tend to produce acetylated opium from locally cultivated opium poppy straw, whereas laboratories in Afghanistan produced morphine and heroin (UNODC, 2008).

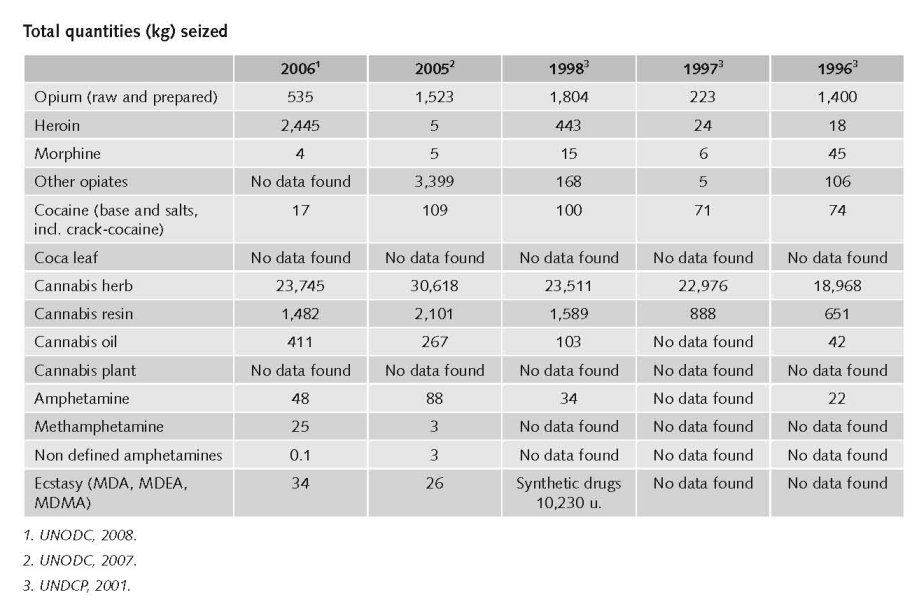

According to the World Drug Report 2008, global heroin seizures amounted to 58 metric tons, about the same as a year earlier (-1%). The largest heroin seizures in 2006 were reported by Iran (10.7 mt or 19% of global heroin seizures), followed by Turkey (10.3 mt or 18%), China (5.8 m or 10%), Afghanistan (4 mt or 7%), Pakistan (2.8 mt or 5%), the Russian Federation (2.5 mt or 4%) and Tajikistan (2.1% or 4%) (UNODC, 2008).

Opiate seizures reported by countries of East Europe (which obtained most of their opiates via the Silk Route) fell by 48% in 2006. In parallel, the Russian authorities reported a marked decline of heroin availability on the Russian market (UNODC, 2008).

The Russian Federation has only reported the seizure of amphetamine laboratories to UNODC. It is possible that these laboratories produce methamphetamine. The Russian Federation reports seizures of both ephedrine and pseudoephedrine, which would point towards the production of methamphetamine (or methcathinone as known as ephedrine) (UNODC, 2008).

Between 1996-2006 there were 918 clandestine amphetamine laboratories reported in Europe. The largest numbers of dismantled laboratories were reported in the Russian Federation (526 or 57%). For 2006 the largest number of laboratories in Europe was reported by the Russian Federation (79) (UNODC, 2008).

The market for cocaine is limited to larger cities and all cocaine inside the Russian Federation is imported from South America through Africa into the Russian Federation. Sometimes the Russian Federation is not the target area but the transit country from which the cocaine is imported into (Central and Southern) Europe. Cocaine may become popular among the ‘Golden Youth’ (expert’s comments).

In 2006 24 metric tons of cannabis were seized in the Russian Federation (UNODC, 2008).

Estimated retail value

(most recent estimates)1

An ecstasy tablet costs around $10-15 in Moscow in 2007 (expert’s comments).

Before 2005 there were many open drug scenes, but after 2005 many of these open scenes were closed. Now, there are many small scale scenes, where only small scale selling takes place (among others through the internet) (expert’s comments).

2.2 Drug Demand

2.2.1 Experimental/recreational drug users in the general population

The Russian Federation is the world’s largest country. As a result the country incorporates many different markets: usage/prevalence/availability of various types of drugs differ largely between the regions.

The Russian Federation is a large consuming country for opiates, especially heroin and home- made opium poppy derivates, such as khanka (chorny) and mak (expert’s comments).

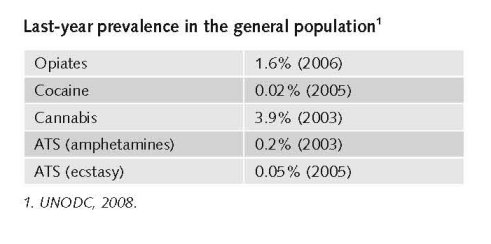

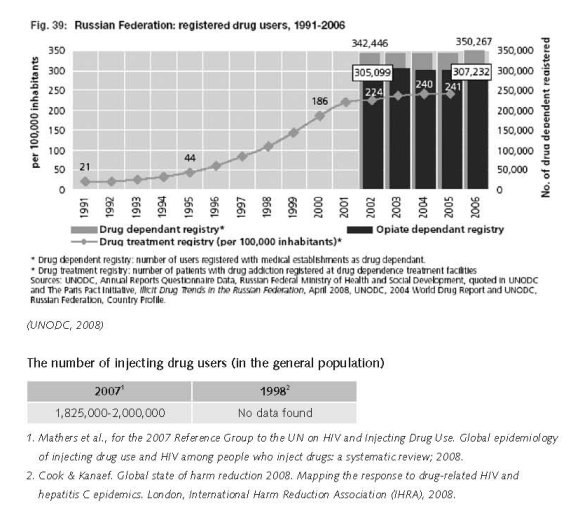

Prior to this year, UNODC used the estimates provided by the Russian authorities for the year 2000/01 which suggested that there were roughly two million opiate users, or 2% of the population age 15-64. New data and research made available by the Russian Federation in 2007 has enabled UNODC to revise the estimate for 2006 to 1.65 million opiate consumers in the Russian Federation or 1.6% of the population age 15-64 UNODC, 2008). Data on registered drug dependent persons suggest that the number of opiate users stabilised or declined in the period 2002 – 2006 (UNODC, 2008).

The market for cocaine is limited and concentrated in the big cities as the substance is very expensive and in general only used by well-to-do people (expert’s comments).

The market for ATS is huge and increasing. Vint, the Russian equivalent of methamphetamine is being prepared and consumed widely for at least the last 10 years (expert’s comments).

In the Russian Federation the use of amphetamines in 2006/2007 is 0.1 – 0.3% of the population (annual prevalence).

The use of ecstasy in 2006 is < 0.1% of the population (annual prevalence but in general the use of ecstasy in 2006 has increased (UNODC, 2008). Consulted experts stated that the use of ecstasy in Moscow among the general population has grown from 0.9% to 2.4% in 2 years (expert’s comments).

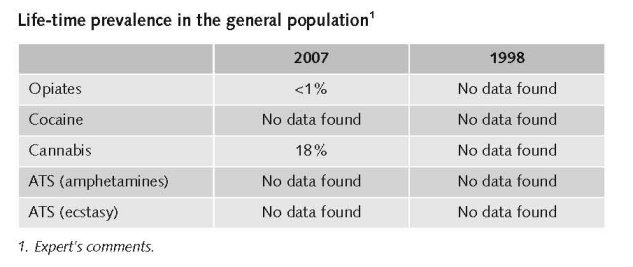

Cannabis is Russia’s main drug of choice. In Moscow, 24% of population between 15-64 have ever tried cannabis. In the Russian Federation, in general the life time prevalence of cannabis use is 18%; for opioids the life time prevalence is below 1% (expert’s comments).

Pharmaceutical drugs such as fentanyl, tranquillizers, etc are also still used but this also depends on the region (expert’s comments).

The estimated number of illicit drug users varies from 3 to 6 million people (UNODC 2008, UNODC 2008b, Human Rights Watch 2007, Bobrova et al. 2007, Russian Harm Reduction Network, 2007) and includes both recreational and frequent/chronic users and both injecting drug users and non injecting drug users and also includes all illicit drugs.

The average age of first use of illicit drugs dropped the last decade from 17 to 14 (UNODC, 2008b).

Prevalence of drug use among young people and last month prevalence is not monitored on a national basis in the Russian Federation (expert’s comments).

Additional information

According to the World Drug Report 2008, the use of heroin and other opiates in the Russian Federation in 2006 was stable. This is also true for the use of cocaine and for the use of cannabis (herb and resin). The use of amphetamines, methamphetamines and related substances in the Russian Federation was stable in 2006. There was however, some increase in the use of ecstasy (MDMA, MDA, MDEA) in the Russian Federation in 2006 (UNODC, 2008).

“Reliable data for prevalence of drug use among the general population in the Russian Federation are not available. Estimations are as valuable as measuring the general temperature in a hospital.” (expert’s comments)

2.2.2 Problematic drug users/chronic and frequent drug users

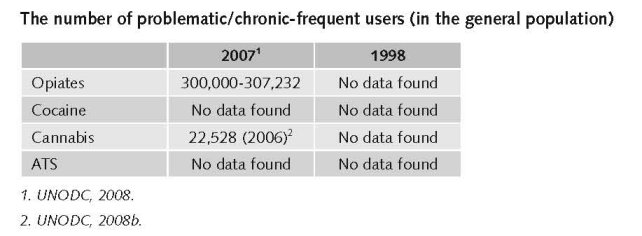

In total there were 517,389 registered drug dependents in the Russian Federation in 2006; 300,000 of them were ‘opiate abusers’, 43,035 were dependent on other drugs; 22,528 persons were ‘cannabis addicts’ (stable) 2006 (UNODC, 2008b).

52,460 people were treated for drug abuse in 2004: 94.3% for dependency on opiates, 0.05% were having problems with cocaine use, 0.5%with amphetamines and 1.8% with cannabis (UNODC, 2007).

A stabilisation also occurred in the Russian Federation, following many years of dramatic increases. The number of registered drug dependent persons (350,267 in 2006), including the number of registered opiate users (307,232 in 2006), has remained largely unchanged over the 2002-2006 period. Russian authorities reported a shortage of heroin on the Russian market in 2007 – despite the strong increase of Afghan opium production (UNODC, 2008).

There are no data available about patients in private institutions. Data are only available for patients treated in state centres.

356,000 people that came to the centres for medical help in 2007 were given the diagnosis of drug addiction (expert’s comments). Another group of drug users (182,000 persons) were not diagnosed with drug addiction, but were found to ‘use drugs in a harmful way’ (= with a potential risk of drug addiction), which is 538,000 people (cumulative) altogether. So the number of problem drug users has increased. The number of people seeking treatment is increasing in both groups (expert’s comments).

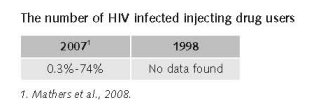

The prevalence of injecting drug use in the age group 15-64 year old to be 1.78% and that the estimated number of people who inject drugs is 1,825,000 (Mathers et al., 2008).

IHRA reports 2,000,000 people who inject drugs in the Russian Federation. Needle and syringe exchange programs exist in the Russian Federation, but there is no opioid substitution treatment (OST) (Cook & Kanaef, 2008).

The number of drug addicts in the Russian Federation increased by 9 times of last decade (UNODC, 2008b).

2.3 Drug related Harm

2.3.1 HIV infections and mortality (drug related deaths)

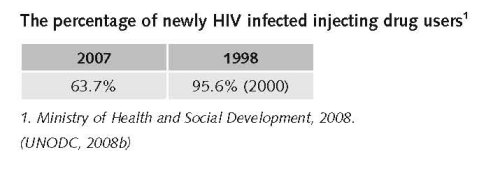

The overwhelming number of HIV-positive people registered in the country by the end of 2007 (82.4% of those who know how they were infected) contracted HIV when using non-sterile instruments for drug injection (Ministry of Health and Social Development, 2008).

However, there are signals showing a shift of the main route of transmission of HIV from injecting drug use to heterosexual transmission.

While the epidemic in Russia has remained largely concentrated among injecting drug users other high-risk groups-sex workers, prison inmates en men who have sex with men, there is clear evidence of a significant rise in heterosexual transmission. The percentage of heterosexually transmitted infections has increased from 17.8% in 2002 to 34.1% in 2007 (Joint UN team on AIDS, 2008)

There are no good figures on HIV prevalence among injecting drug users in the Russian Federation. The estimates range from 0.3% (low) to 37.15% (mid) to 74% (high) (Mathers et al., 2008). According to IHRA estimates there are 2,000,000 injecting drug users in the Russian Federation, among which adult HIV prevalence is between 12-30% (Cook & Kanaef, 2008).

The drug use explosion of the late 1990s was accompanied by a rapid increase in the number of HIV infections. Due to poor knowledge of HIV and the frequent joint use of injecting equipment, HIV spread rapidly. In the years between 1995 and 2001 the rate of new infection doubled every six to twelve months. By mid-2006 almost one million people were believed to be HIV-positive, the vast majority of them infected through drug use. Rates of HIV infection among drug users vary considerably across Russia. According to National Research Institute for Substance Abuse studies, 9.3 percent of injection drug users who are registered with state narcological clinics were HIV-positive in 2005. In some Russian cities studies have found considerably higher prevalence rates. For example, UNAIDS cites studies that found that 30 percent of injection drug users in St. Petersburg were HIV-positive and 12 to 15 percent in Cherepovets and Veliky Novgorod (Human Rights Watch, 2007).

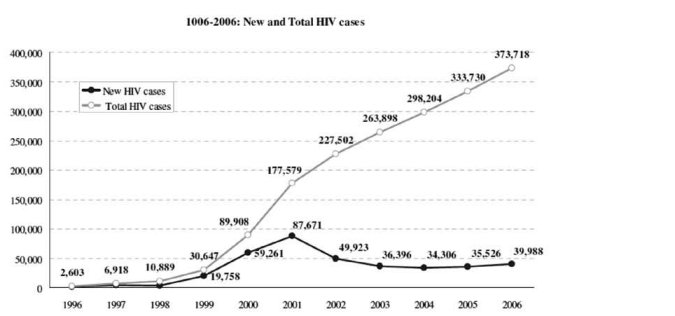

The HIV epidemic in the Russian Federation continues to grow, although not as rapidly as in the late 1990s. The annual number of newly registered HIV cases declined between 2001 and 2003 (from a peak of 87,000 to 34,000), but has subsequently started to increase again. In 2006, 39,000 new HIV diagnoses were officially recorded, bringing the total number of HIV cases registered in the Russian Federation to about 370,000 (UNAIDS/WHO, 2008); HIV cases represent only those persons who have been in direct contact with the Russian Federation’s HIV reporting system (UNAIDS/WHO, 2008).

The close links between injection drug use and HIV infection add extra urgency to the need for effective drug dependence treatment. Injection drug users make up an estimated 65 to 80 percent of all persons living with HIV in Russia and about 10 percent of injection drug users in Russia are HIV-positive. Effective drug dependence treatment has been shown to help reduce HIV infections, as patients may either stop using drugs altogether or may adopt less riskful injection behaviour. Today, as Russia is rapidly expanding access to antiretroviral (ARV) treatment for people living with HIV, effective drug treatment programmes, including methadone maintenance therapy and drug-free programmes, could play an important role in aiding drug users in accessing and adhering to ARV treatment. If Russia does not take steps to address the problems of its drug dependence treatment system, it runs the risk of continued and increasing spread of HIV, and even drug resistant HIV strains, due to lack of access by drug users to ARV and their suboptimal adherence due to poor quality drug dependence treatment programmes (Human Rights Watch, 2007).

From the late 90s to early 2000s it was generally accepted that the HIV epidemic was mostly driven by young, urban, male injecting drug users. More recently, however, large numbers of women have also been affected by the epidemic. (…) there is evidence that most women become infected through sexual transmission (MAP, 2008).

Although the percentage of IDUs among new HIV cases decreased from 95.6% in 2000 to 63.7% in 2007, the main route of HIV infection in the Russian Federation in 2006-2007 remained intravenous drug use (Ministry of Health and Social Development, 2008).

A lethal overdose of narcotic drugs is a complicated toxicological diagnosis. The full set of tests is carried out very rarely (not done routinely, only on suspicion). Post-mortem diagnosis in drug overdose cases is usually respiratory failure or heart failure, which are pathophysiological causes of death in such cases and would not be registered as drug related deaths. For example, the national database of causes of deaths in 2003 revealed only 200 cases of drug overdose deaths nation-wide.

Sources point to Moscow, Orenburg and Volgograd reporting a perceived increase in drug related mortality; however only Orenburg provided information that the number of overdose related cases in 2005 was 31 (Ministry of Health and Social Development, 2008).

2.3.2 Drug related crime or (societal) harm

There is not much information available on drug-related harm for society. With regards to drug-related crime there are some data. Over 240,000 drug crimes (acquisition, sale, manufacture etc.) were registered in 2006 by the Russian law enforcement agencies. This is an increase 23% compared to 2005. The number of crimes related to drug trafficking increased by 12% in 2006 (100,000 cases 2005 and 123,000 cases in 2006), but the proportion of trafficking declined (58% in 2006 against 63% in 2005) (UNODC, 2008b).

The level of drug related crime has remained stable over the years. The number of serious crimes such as drug trafficking is more or less stable. Law and amendments have no effect on the share of drug related crime (expert’s comments).

3 Drug policy

3.1 General information

3.1.1 Policy expenditures

Estimates of total annual expenditures in 2007 on drug policy measures

In general the available budget for drug policy increased as they created the Federal Drug Control Service (FNSC) in 2004. Especially the budget for drug supply reduction has increased since 2004 (expert’s comments).

Expert comments

The federal target programme has little to do with drugs. It is a very vague programme. Nobody really knows how much money is spent on which targets.

Figures for budget spent on treatment and a comparison between the budgets for demand reduction and supply reduction are not available. Several institutions are active work in these issues, e.g. FDCS, Federal Security, Ministry for Internal Affairs, Ministry for Agriculture. Most of them are focussing on law enforcement (expert’s comments).

3.1.2 Other general indicators

Numbers available on arrests and imprisonment for drug-law related offences

The number of arrests and imprisonments for drug-law related offences has increased, as more drugs come into the Russian Federation (expert’s comments).

Numbers available on arrests and imprisonment for use/possession for personal use

In most CIS countries, police are known to make arrests for possession of even minimal amounts of narcotic substances. Narcotic laws in Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan and the Russian Federation aim to seek out and punish users both for purchase and possession. Out of fear for incarceration or fear of ending up in the official state roster of registered drug users, many injecting drug users do not seek treatment or use clean needles.

This has serious implications for the implementation of harm reduction services. For instance, although syringes can be legally purchased from a pharmacy in the Russian Federation, people working in the field of HIV prevention say that police often watch certain pharmacies to keep an eye out for ‘regular buyers’. At the same time, law reforms in 2004 have decriminalized possession of small amounts of drugs, which, in turn, significantly reduced the number of drug users ending up in the Russian Federation’s prison system (MAP, 2008).

The focus of law enforcement has shifted from use/possession to production, trafficking and (large scale) dealing, but at street level these changes do not influence or alter the actual selling of drugs. Small–scale drug trafficking and selling of drugs, the availability of drugs and the prices have not changed substantially because of the shift in focus of law enforcement (expert’s comments).

In the law no distinction is made between different types of drugs. However in determining the sentences courts sometimes differentiate between types of drugs (expert’s comments).

3.2 Supply reduction: Production, trafficking and retail

The main focus is on fighting drug crime, production, trafficking, criminal networks and money laundering. There has been a shift in drug policy in 2004, increasing enforcement efforts on these issues, as larger scale drug-related crimes got increasingly in the hands of organised crime (expert’s comments).

Among the new measures introduced recently is an increased alertness of law enforcement at the border with Afghanistan, as most of the heroin comes from this country. Recently an agreement has been reached between governments of the Russian Federation and Iran, Afghanistan and Central Asia to cooperate on drug related issues. In 2007 an anti-drug committee was created to coordinate the fight against drugs (expert’s comment).

Changes regarding drug policy realised during the past ten years

From 1996 to 2004, possession of very small amounts of heroin – as little as 0.005 gram (about one hundredth of an average daily dose) – was a criminal offence for which a prison sentence of five to seven years could be imposed. During that period, many drug users were prosecuted for possession of small amounts of drugs that were meant for personal use. Many ended up in prison for a substantial period.

In recent years there have been some attempts to move away from pursuing drug users.

In 2004, the Russian government inserted a Note to Article 228 of the 1996 Criminal Code to the effect that possession of small amounts of drugs (“less than 10 average single doses”) resulted in an administrative violation rather than a criminal offence. Following this amendment, some 32,000 people were released from prison or had their sentences reduced. However, internal opposition to the amendment led to its repeal. In December 2005, a new law was passed which removed the term “average single dose” from Article 228. The new law could result in more drug users being prosecuted and imprisoned for possessing relatively small amounts of any illegal drugs, including cannabis.

Though the use of drugs itself is only an administrative offence, as users usually have drugs with them they can be (and are) charged with possession (expert’s comments).

In February 2006 the Russian government partially reversed the reforms of May 2004. Possession of more than one-half of a gram of heroin is now considered a criminal offence. According to Levinson, the number of criminal prosecutions for possession of illicit drugs has risen sharply since February 2006, with 30,000 more people facing prosecution for the crime in 2006 than in 2005 (Human Rights Watch, 2007).

October 2007, a State Drug Control Committee on Additional Measures to Counter Illicit Trade in Narcotic Drugs, Psychotropic Substances and Precursor Chemicals was established by Presidential Decree in the Russian Federation. While the Federal Drug Control Service maintains its responsibility of coordinating law enforcement activities against illicit drug trafficking, the Committee has the mandate to monitor and coordinate the decision-making process and implementation of executing agencies at all levels of the Government (INCB, 2008).

3.3 Demand reduction: Experimental/recreational drug use + problematic use/chronic-frequent use

Preventive measures increased over the years, as there are now more financial possibilities for such interventions.

Telephone help lines exist. However, the coverage is mixed. It differs per region. There are no data about the number of telephone helplines, nor about the message they spread (anti-drugs, harm reduction, referral to treatment, etc)

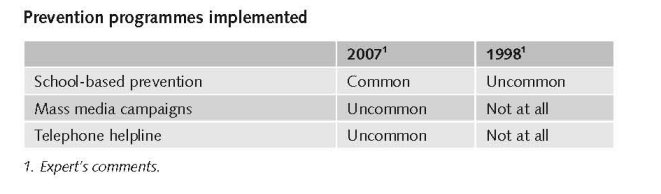

School-based drug prevention is more common than ten years ago. There is no control regarding the quality of this programme. Mass media campaigns are uncommon. There are not well developed (expert’s comments).

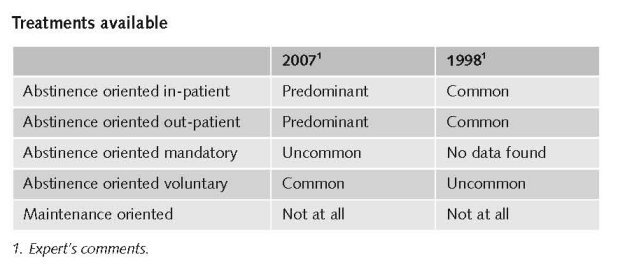

Drug users in the Russian Federation who wish to seek medical treatment can do so through the state drug dependence treatment system, which offers them detoxification services and, in some regions, rehabilitation treatment. Today, treatment is mostly voluntary, although in certain, limited circumstances drug users can also be forcibly committed to treatment (Human Rights Watch, 2007).

Narcological clinics (detoxification) are available in all major towns in the Russian Federation, but they cost up to $500/ month which many people cannot afford. The treatment demand is bigger than the services provided, but this differs per city. Sometimes there are waiting lists, but also the costs and the fact that patients get registered as drug user is a barrier for many persons to seek treatment.

However, aftercare – e.g. managing craving and relapse prevention – is provided in only 26 out of 85 regions in the Russian Federation. In some regions there are private and / or religion-based rehabilitation centres besides these state centres. These services are generally even more expensive than the state centres (Human Rights Watch, 2007).

There is ample evidence that the state drug dependence treatment system in Russia is largely ineffective (Human Rights Watch, 2007).

Drug abuse treatment services in Russia include both in-patient and out-patient care, focussing on short-term medical care for withdrawal symptoms associated with drug- and alcohol-addicted individuals. Such care is in most cases provided in narcological dispensaries (n = 182), in-patient facilities for the management of drug detoxification and the complications of drug misuse, and narcological cabinets (n = 1,975), which provide out-patient care mostly for alcohol dependent patients (Bobrova et al., 2007).

In the Russian Federation no difference is made between drugs and alcohol treatment, or between specific treatments for different drugs. There is only a special system available for people suffering from HIV/AIDS, as they go to AIDS centres to get treatment including drug treatment (expert’s comments).

In the Russian Federation, the Government is considering drafting legislation on compulsory treatment for drug addicts. The Federal Drug Control Service expects that, once adopted, the new law will lead to the establishment of special medical centres where drug addicts will undergo treatment on the basis of a court decision (INCB, 2008).

Yet (…) the vast majority of individuals addicted to drugs in Russia does not have access to evidence-based medical care to treat their dependence. Russia has made policy decisions relating to the provision of medical treatment for drug dependents that are inconsistent with and in violation of its obligation to provide, within available resources, health care that meets the criteria of available, accessible, and appropriate. While detoxification treatment is widely available throughout Russia, rehabilitation treatment remains unavailable in many parts of the country. Private drug dependence clinics, some of which offer evidence-based rehabilitation treatment, are often unaffordable for drug users. Various obstacles keep drug users away from seeking treatment at state clinics, including the risk of restrictions on civil rights by being registered as a drug user, breaches of confidentiality associated with treatment, and a widespread distrust of drug treatment services that also undermines take-up rates. The treatment offered at detoxification clinics does not follow lessons learned from decades of research on effective drug dependence treatment modalities. On the contrary, policy decisions relating to what drug treatment programs can be offered deliberately ignore the best available medical evidence and recommendations, and as such arbitrarily restrict drug users’ access to appropriate health care (Human Rights Watch, 2007).

One of the most effective and best researched drug dependence treatment modalities for opiate dependence known today, maintenance treatment (methadone and buprenorphine) is banned by law in the Russian Federation (Human Rights Watch, 2007; Cook & Kanaef, 2008).

3.4 Harm reduction

3.4.1 HIV and mortality

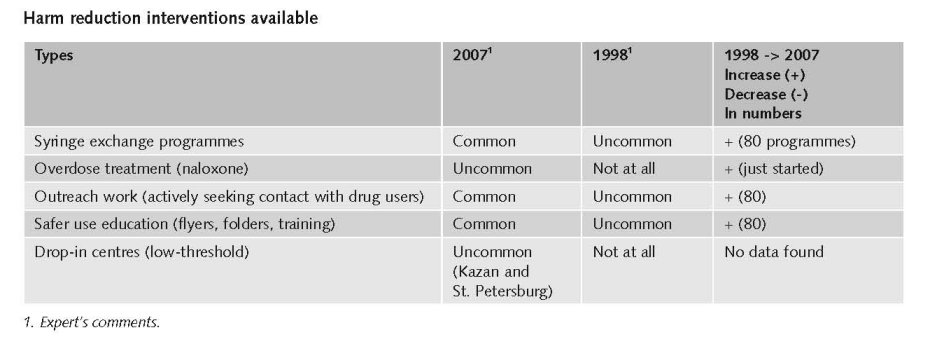

In the Russian Federation, there is no explicit supportive reference to harm reduction in national policy documents (Cook & Kanaef, 2008).

In 2003 the Russian State Duma (parliament) adopted a series of amendments to the Russian criminal code that included an annotation to article 230 that specified that “promotion of the use of relevant tools and equipment necessary for the use of narcotic and psychoactive substances, aimed at prevention of HIV infection and other dangerous diseases” did not violate the article provided that it is implemented with the consent of relevant health and law enforcement authorities (Human Rights Watch, 2007).

These amendments meant that needle and syringe exchange, including distribution of drug paraphernalia such as bleach and sterile water, were from that date more or less approved of by the State. It paved the way for the establishment of more harm reduction NGO’s throughout the Russian Federation.

However, for some years, the Russian police service and the Federal Drug Control Service (FDCS) continue to suggest that the provision of sterile injecting equipment to injecting drug users (IDUs) contravene laws prohibiting the ‘promotion’ of drug use. Despite the amendment, in the form of an explanatory Note, to Article 230 of the 1996 Criminal Code, which provides a legal basis for the provision of sterile injecting equipment, the fact is that organisations (mostly civil society) providing this equipment still operate in a climate of legal uncertainty. This is because the draft government order providing guidelines on how these programmes should be established and implemented has yet to be approved and published. Although some federal funding is earmarked for organisations providing free sterile injecting equipment to IDUs, the amount falls far short of that required to provide adequate service provision and coverage. The majority of the 40 NSP (Needle Exhange Programmes) operational in Russian Federation are maintained by international funding (mainly – the Global Fund) (expert’s comments).

But, there is no law in which harm reduction as such is mentioned leave alone approved, but some legal protection for drug users is mentioned in the criminal code (expert’s comments).

3.4.2 Crime, societal harm, environmental damage

In the Russian Federation, there is no explicit supportive reference to harm reduction in national policy documents (Cook & Kanaef, 2008).

References

Consulted experts

A. Bidordoniva, Freelance Consultant HIV/AIDS prevention and epidemiology.

A. Khatchiatrian, Head of representative office in the Russian Federation, Regional Director of Programs in the Russian Federation and Ukraine at the Transatlantic Partners Against AIDS.

E. Koshkina, Epidemiologist, Russian National Narcological Research Centre.

A. Pavlovksy, Outreach worker, Russian Harm Reduction Network.

V. Pelipas, Drug policy Expert, Russian National Narcological Research Centre.

A. Sarang, Coordinator, Russian Harm Reduction Network.

UNODC RORB staff.

Documents

Bobrova N, Alcorn R, Rhodes T, Rughnikov I, Neifeld E, Power R. Injection drug users’ perceptions of drug treatment services and attitudes toward substitution therapy: a qualitative study in three Russian cities. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 2007, 33: 373–8.

CIA. The World Factbook: Russian Federation.

Available: www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/rs.html, last accessed 10 December 2008.

Cook C, Kanaef N. Global state of harm reduction 2008. Mapping the response to drug-related HIV and hepatitis C epidemics. London, International Harm Reduction Association (IHRA), 2008.

Human Rights Watch. Federal Target programme: comprehensive measures to combat drug abuse and drug trafficking 2005-2009. Rehabilitation Required: Russia’s Human Rights Obligation to Provide Evidence-based Drug Dependence Treatment, 2007.

INCB (International Narcotics Control Board 2007). Report. Vienna, 2008.

Joint UN Team on AIDS. Joint UN Programme of Support on AIDS in the Russian Federation 2009-2010. Moscow, 2008

MAP (Monitoring the AIDS Pandemic). AIDS in the Commonwealth of Independent States, 2008.

Mathers BM, Degenhardt L, Phillips B, Wiessing L, Hickman M, Strathdee SA et al. for the 2007 Reference Group to the UN on HIV and Injecting Drug Use. Global epidemiology of injecting drug use and HIV among people who inject drugs: a systematic review, 2008.

Ministry of Health and Social Development. Country Progress Report of the Russian Federation on the Implementation of the Declaration of the Commitment on HIV/AIDS, January 2006-December 2007. Moscow, 2008.

Russian Harm Reduction Network. Civil society Report. Russia’s way towards universal access to HIV prevention, Treatment and Care prepared by the Russian Harm Reduction Network, Nation Forum of NGO’s, HIV/AIDS NGO’s, the Russian Union of PLHIV, with support of the European Harm Reduction Network (EHRN) and International Treatment Preparedness Coalition in Eastern Europe and Central Asia. 2008.

UNAIDS (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS) and WHO (World Health Organization). Eastern Europe and Central Asia. AIDS epidemic update regional summary. Geneva, 2008.

UNDCP (United Nations International Drug Control Programme). Studies on Drugs and Crime. Global Illicit Drug Trends 2000. Statistics. Vienna, UNDCP, 2001.

UNODC (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime). World Drug Report 2007. Vienna, UNODC, 2007.

UNODC. World Drug Report 2008. Vienna, UNODC, 2008.

UNODC. World Drug Report 2008: Global ATS Assessment. Vienna, UNODC, 2008a.

UNODC. Illicit Drug Trends in the Russian Federation. Moscow, UNODC Regional Office for Russia and Belarus, 2008b.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|