Appendix to report 4: country reports INDIA

| Reports - A Report on Global Illicit Drugs Markets 1998-2007 |

Drug Abuse

INDIA

1 General information

Location:

Southern Asia, bordering the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal, between Burma and Pakistan

Area:

3,287,590 sq km

Land boundaries/coastline:

14,103 km/ 7,000 km

Border countries:

Bangladesh 4,053 km, Bhutan 605 km, Burma 1,463 km, China 3,380 km, Nepal 1,690 km, Pakistan 2,912 km

Population:

1,147,995,904 (July 2008 est.)

Age structure:

0-14 years: 31.5% (male 189,238,487/female 172,168,306)

15-64 years: 63.3% (male 374,157,581/female 352,868,003)

65 years and over: 5.2% (male 28,285,796/female 31,277,725) (2008 est.)

Administrative divisions:

28 states and 7 union territories

GDP (purchasing power parity):

$2.966 trillion (2007 est.)

GDP (official exchange rate):

$1.099 trillion (2007 est.)

GDP - per capita (PPP):

$2,600 (2007 est.) (CIA The World Factbook)

Drug research

In 2008, United Nations office on Drugs and Crime, Regional Office for South Asia (UNODC-ROSA) conducted a rapid assessment of drugs and HIV in South Asia, including India. Further there is drug research taking place at local/regional level, such as Chennai, Manipur, and New Delhi. In the biggest cities of India there is expertise in this field available.

Main drug-related problems

India is mainly a consumption country of cannabis, opioids and pharmaceuticals.

2 Drug problems

2.1 Drug supply

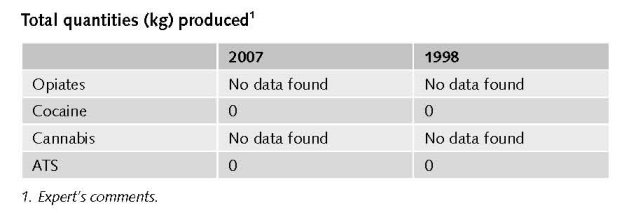

2.1.1 Production

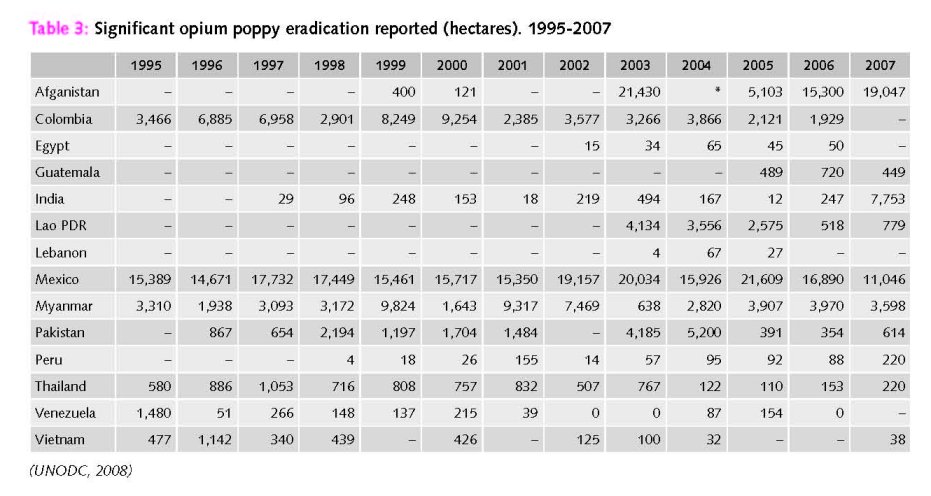

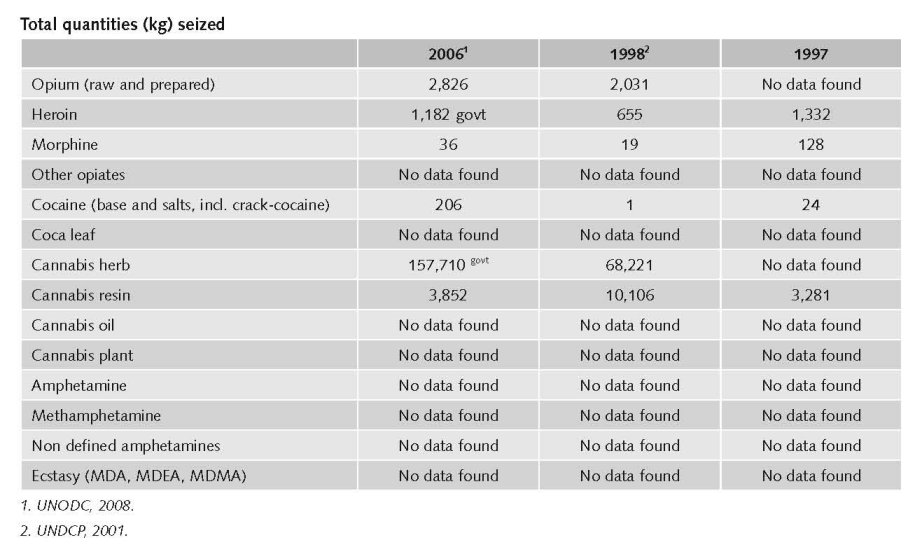

India does not play a major role as production country of any drug, except for legal production of opium. It is together with Turkey the world’s largest producer of legal opium. Illicit production of opium also exists, given the growing number of eradications of opium poppy fields over the years (UNODC, 2008).

A domestic market in illicit cannabis derivates (charaz) exists, and further a few people are licensed to grow cannabis (expert’s comments). Cannabis is cultivated (mostly resin but also herb) also for export. India is seen as an important producer of cannabis resin in South-Asia (UNODC, 2008). This is underlined by the fact that Nepal and India were mentioned by 8.5 of countries as the main source of cannabis resin on their markets (UNODC, 2008).

India has a significant chemical industry and is one of the largest exporters of licit ephedrine and pseudoephedrine, making it a target for ATS precursor diversion and illicit manufacturing of ATS by international drug trafficking organizations (UNODC 2008a).

A large (domestic and export) market in illicit (non-prescribed) pharmaceutical drugs exists in India. ATS production is rather limited in India (expert’s comments).

In 2003, the first clandestine ATS laboratory (ATS not specified) was reported and dismantled in Kolkata (in east India), followed by another laboratory in 2004 located in Hyderabad (south-eastern India). Elevated activity related to ATS reappeared in 2006, with the discovery of an illicit laboratory in Gurgaon (northern India). The laboratory was reportedly set-up by transnational organized crime groups from East Asia and North America to manufacture ephedrine-based meth-amphetamine. In a separate incident (November 2006), after prolonged surveillance, a sea container holding a complete mobile laboratory and chemicals for illicit manufacture of methamphetamine was seized in transit off the coast near Kolkata. It was believed to be part of a larger organization for manufacture most likely in New Delhi. In 2007 a clandestine methamphetamine-related laboratory for the extraction of precursors from pharmaceutical preparation was discovered in Mumbai. Authorities seized 290 kg of pseudoephedrine destined for Australian laboratories and arrested five persons including foreign nationals involved in the extraction process (UNODC, 2008a).

Roughly 39% percent of tableted amphetamines-group substances were reported to come from India and about 20% from the Netherlands (UNODC, 2008a).

2.1.2 Trafficking

Trafficking of pharmaceuticals from India to neighbouring countries takes places at a large scale (UNODC, 2008a).

While there have been reports for several years of tablet methamphetamine (known locally as yaba’) in the markets of China, Lao PDR, Cambodia, Thailand and Viet Nam, and to a lesser extent Malaysia, reports from 2007 show methamphetamine from Myanmar shifting west into new markets in Bangladesh, India and Nepal (UNODC, 2008a).

Pharmaceutical preparations containing narcotic drugs are widely trafficked and abused in India. Codeine based syrups are diverted from the licit market in India and smuggled into Bangladesh (INCB, 2008).

In Moreh (eastern State of Manipur on the India-Myanmar border), methamphetamine is commonly trafficked into India while precursor chemicals are trafficked to Myanmar as part of a larger criminal network which has also included the trafficking of counterfeit currency, pharmaceuticals and other illicit drugs. The area is vulnerable to significant illicit trafficking due to the lack of a clearly demarcated border and generally unrestricted movement of people and goods (UNODC, 2008a).

2.1.3 Retail/Consumption

India was the largest opiate market (in 2006) in the sub-region with an estimated opiate using population of around 3 million persons (UNODC, 2008).

The opiate market is India is considered stable, but has increased if compared to the situation in 1998 (expert’s comments).

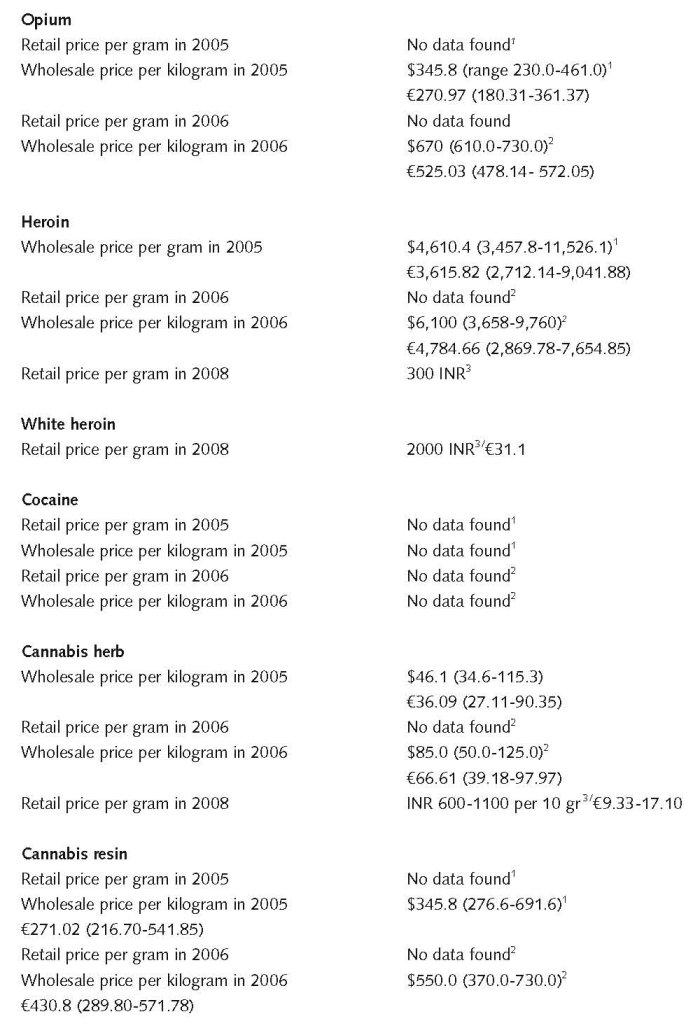

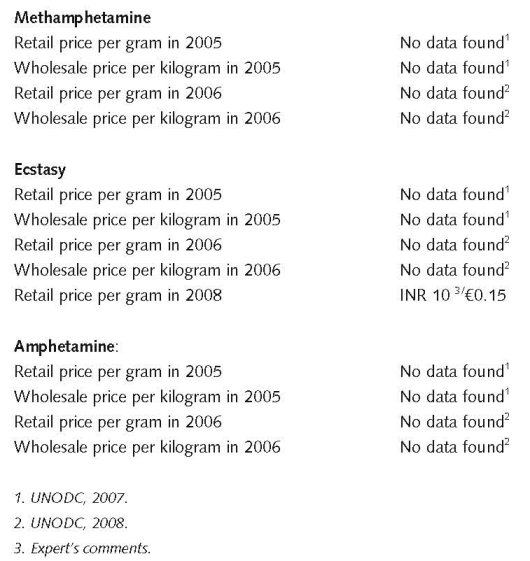

Estimated retail value

(most recent estimates)

1 $1 = € 0.783014. Exchange rate 26 February 2009.

2 1 INR = € 0.0155500. Exchange rate 26 February 2009.

Expert comments

The quality of heroin (at least in Delhi) is declining; this is why people move from heroin to pharmaceuticals (stable quality, cheaper).

2.2 Drug Demand

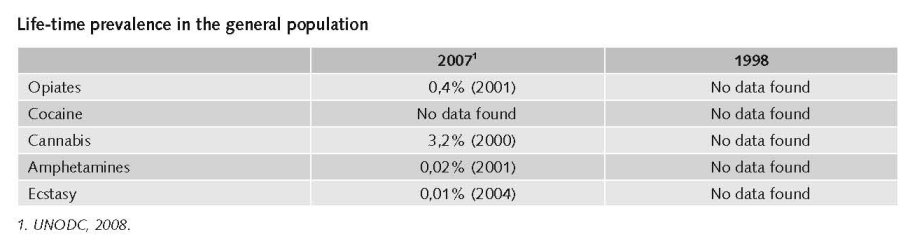

2.2.1 Experimental/recreational drug users in the general population

Most countries of East and South-East Asia reported declines in opiate use in 2006, reflecting the strong declines of opium production in Myanmar and the Lao PDR in recent years. Countries reporting declines included China, Indonesia, the Philippines, Malaysia and Myanmar. Overall, use trends as perceived by experts showed a small decline for the year 2006. Over the 1996-2006 period the same indicator highlights Asia as the driving force behind the increase in the total number of opiate users at the global level. If experts did not perceive increases in the opiate markets in South West Asia and Central Asia over that period, the trend would have remained stable, not only in relative terms (prevalence rates) but also in absolute numbers (UNODC, 2008).

Unfortunately, existing national and regional monitoring systems are often not capable of generating representative data. For example, neither India nor China – collectively accounting for 38% of the global population – has ever conducted a nationally representative survey on ATS consumption (UNODC, 2008a).

The number of ATS users and cocaine users is still very low, and may be centred in a few scenes in Delhi and in NE India (expert’s comments).

The most current estimate (2001) of amphetamine group use in India’s population (15-64 years) is 0.2%. Use at that time was reported to be mostly limited to regions such as Kerala (on the southern coast), Uttar Pradesh (in the northeast near the Nepal border), and Manipur - the area also noted for its methamphetamine and precursor trafficking. Given the identification of several clandestine ATS operations in India, confirmed proliferation of methamphetamine seizures from neighbouring Myanmar and other countries of East and South-East Asia and the speed with which ATS can emerge in a new market, the potential for ATS to expand in India should not be underestimated (UNODC, 2008a).

The number of cannabis users is estimated 8.7 million (UNODC ROSA, 2007). There is no information available whether the number of cannabis users increased, decreased or remained stable over the past 10 years.

Pharmaceuticals are used widely throughout the country, but no data have been found (expert’s comments).

Applying prevalence estimates to the population figures in 2001, based on population growth, it can be projected that in that year there were about 62.5 million alcohol users, about 8.7 million cannabis users and about 2 million opiate users in the country (UNODC, MSJE & UNESCO, 2004).

No data have been found on last-year prevalence in the general population and on life-time, last year, and/or last month prevalence among young people.

Additional information

Irregular or incomplete reporting from Member States is compounded by the varying quality of data provided. Specifically, and similar to other drugs, information about the extent of ATS consumption (prevalence rate) is the weakest indicator, as household and other surveys are lacking or are outdated in some countries in several of the most affected regions (according to supply side indicators and/or expert opinion). Unfortunately, this is the case in several populous countries (i.e. China and India), thus affecting regional and global prevalence estimates (UNODC, 2008a).

2.2.2 Problematic drug users/chronic and frequent drug users

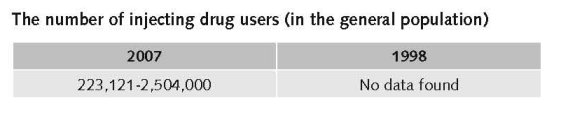

The number of problematic/chronic-frequent users (in the general population)

Approximately 73.54 million people dependent on drugs, of which 62.46% on alcohol (UNODC ROSA, 2007).

The estimated range of injecting drug users across the country is between 223,121 (male) (NACO 2007) through 1,112,500 (Cook & Kanaef, 2008) to 2,504 million opiate users including IDU (UNODC ROSA, 2007). But not all opiate users are problem users. However, injecting drug use nationwide is on the rise (although this differs from region to region).

There is a shift towards more risky modes of use: from non-injecting to injecting. This shift from non-injecting heroin to injectable pharmaceuticals occur, when heroin is scarce; when the cost of heroin is increasing; when there is an observable reduction in purity levels; when police enforcement is vigilant Further, injectable pharmaceuticals are more easy available and costs are less (Raju, 2008).

Injecting drug use is reported to be increasing in at least ten countries in the region (Afghanistan, India, Indonesia, Japan, PDR Laos, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan, the Philippines and Sri Lanka), while there are reported declines in injecting in Hong Kong and Taiwan (Cook & Kanaef, 2008).

Injection drug use is a major driver of the epidemic in the northeast states. Recent size estimation data show that injecting drug users could constitute 1.9 – 2.7% of the adult population in Manipur and Nagaland. In addition to the known risks of HIV transmission through sharing injection equipment, sexual transmission is also important. In a sample of injecting drug users in the northeast, 75% were HIV positive, most were under the age of 19 years, two-thirds were sexually active, and 3% reported using condoms. The risk of HIV transmission to sexual partners and wives of injecting drug users has been documented across India (…) Injecting drug users are also found in most of the major cities in India outside the northeast) and HIV prevalence rates ranging between 2% and 44% have been documented among them. Little is known about injecting drug user overlap with other risk groups in states outside the northeast (Chandrasekaran et al., 2006).

The situation in North East India differs largely from the rest of India. In NE India there is a large injecting culture, and this has led to major outbreaks of HIV in this area (Manipur) (expert’s comments).

Injectable pharmaceutical opioids like Morphine, Pethidine, Pentazocine (Fortwin®), Buprenorphine alone or in combination with other drugs, Propoxyphene; Spasmoproxyvon, (Dextropropoxyphene® plus Dicyclomine) ínjectable Benzodiazepines like Diazepam (Calmpose®) and injectable Anti Histamines like Promethazine (Phenargan® Chlorpheniramine (Avil®) are widely used, although no data are available about the numbers of users (Raju, 2008).

2.3 Drug related Harm

2.3.1 HIV infections and mortality (drug related deaths)

The number of HIV infected injecting drug users

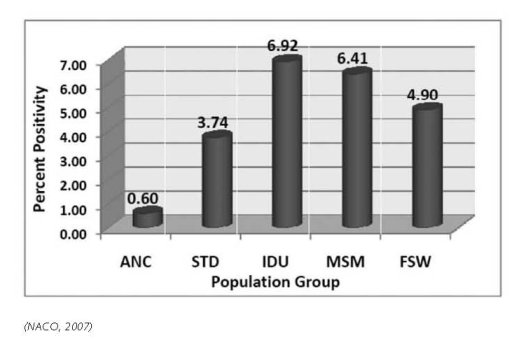

Estimated number of HIV+ infected persons has gone up from 3,5 million in 1998 to 5,206 million in 2005 (NACO 2007). While adult HIV prevalence among the general population is 0.36 percent, high-risk groups show higher numbers. Among Injecting Drug Users (IDUs), it is as high as 8.71%, while it is 5.69% and 5.38% among Men who have Sex with Men (MSM) and Female Sex Workers (FSWs), respectively (www.nacoonline.org, accessed June 2008). 2.2% of all cumulated HIV infections were attributed to IDU in 2003 (UNODC ROSA, 2007).

Adult HIV prevalence amongst people who inject drugs in India is ranging from 1.3% to 68.4% (Cook & Kanaef, 2008).

Mathers et al. report an estimate of HIV prevalence of 11.15% among IDU for 2004 (Mathers et al., 2008).

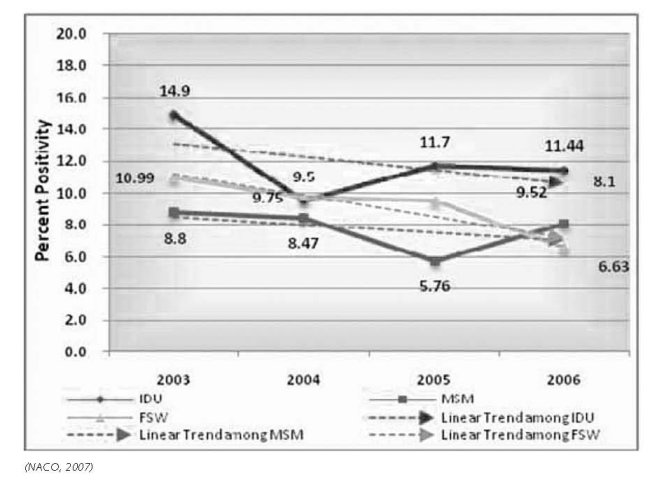

HIV prevalence among IDU in selected states (see below) show that the prevalence in India does not follow a specific pattern: in some areas HIV prevalence among IDU is increasing, whereas in other areas it is decreasing or more or less stabilising:

The number of newly HIV infected injecting drug users

The number of newly HIV infections increased compared to 10 years ago. But the number of newly infected IDU tends to decline over the past. The transmission route is predominantly sexual (87.4 percent). In the North Eastern states/provinces10, besides injecting drug use, which is the main route of HIV transmission, heterosexual route is emerging as an important mode of transmission. The other routes of transmission by order of proportion includes perinatal (4.7 percent), unsafe blood and blood products (1.7 percent), infected needles and syringes (1.8 percent) and unspecified and other routes of transmission (4.1 percent) (UNGASS, 2008).

The number of drug related deaths by overdose

Data about drug related deaths or drug overdose are not systematically collected; however several experts, e.g. in Chennai, report many drug overdoses, but there are no exact data available (expert’s comments).

2.3.2 Drug related crime or (societal) harm

No data found on drug related crime or (societal) harm.

3 Drug policy

3.1 General information

3.1.1 Policy expenditures

Estimates of total annual expenditures in the past ten years

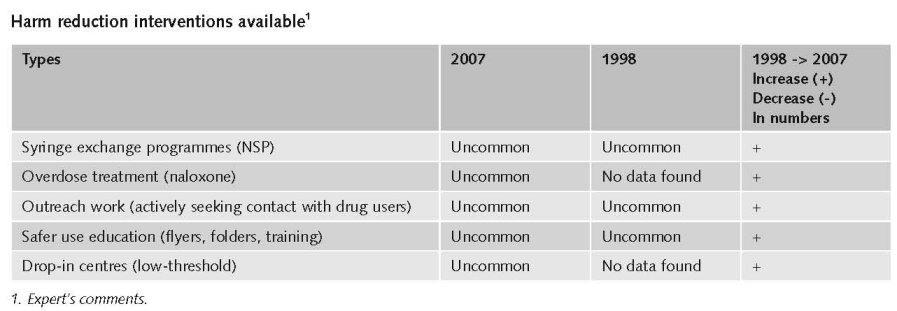

Expenditures on drug policy measures as a whole increased over the past ten years. This is among others due to the fact that the number of treatment facilities as well as the number of harm reduction interventions increased the period mentioned (expert’s comments).

No data are found on national expenditures on drug policy measures. It is considered that the expenditures on supply reduction measures are much higher than on treatment. Expenditures on harm reduction only started recently (expert’s comments).

3.1.2 Other general indicators

Numbers on arrests and imprisonment for drug-law related offences

19,563 persons were arrested in 2006 for drug related matters (NCB, 2006).

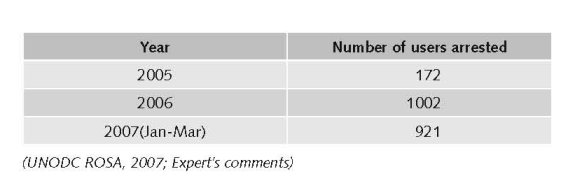

Not much information could be found on arrests. The number of arrests and convictions for drug related offence has risen over the past 10 years. In India, street users are ’soft /easy targets’ for the police. E.g. in Mumbai enforcement action against users has witnessed an increasing trend:

3.2 Supply reduction: Production, trafficking and retail

Main focus

Main focus in India is on trafficking and retail. Since laws differentiate between quantity and substance, the focus is now more on drug dealing.

Control over psychotropic substances is a relatively new phenomenon in India. India is emerging as transit route for illicit drugs. Besides pressure to comply with international conventions there is an internal drive to work with a deterrent approach.

The focus of the law is on

• Regulation through licenses for cultivation, production, export-import, transport;

• Control over use for medical & scientific purposes;

• Prohibition of everything that does not fall in 1) and 2).

This resulted in a rather harsh approach in the late eighties, including rulings that all drug offences had to be prosecuted and for instance bail was impossible. Death penalty was introduced for repeated conviction for specific crimes (UNODC ROSA 2007; expert’s comments).

Changes regarding drug policy realised during the past ten years

The new elements concern the decriminalisation of the possession of small amounts of drugs for personal use (expert’s comments).

Priorities covered by law or other legal provisions/arrangements

Opium Act, 1857

• Introduced licenses for poppy cultivation;

• Commenced a more lenient approach towards possession or consumption of opium.

Opium Act, 1878

• Strengthened government control on all aspects of cultivation & opium trade;

• Penalised ‘unlawful’ possession of opium.

The Dangerous Drugs Act, 1930

• The list of ‘dangerous drugs’ was extended to coca, cannabis & synthetic opium;

• Prohibited cultivation, manufacture & trade except with government sanction;

• Decriminalised possession for personal consumption;

• Allowed opium supply to registered ‘addicts’.

Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances ACT, 1985

• Introduced in 1985 under international pressure to comply with International Conventions;

• Laid down a strict criminal regime; penalising all aspects of drug use;

• Provided extraordinary powers of enforcement, diluted rules of evidence including presumption of culpability & reversal of burden of proof.

In 2001 a more lenient approach towards drug users was chosen. Penalties took into account differences in substance and quantity. Sentences also included provisions for treatment for drug dependency. From 2001 onwards, a differentiation is being made between small, medium and large (commercial) amounts. Penalties for consumption cover a range from a fine (Rs. 10,000 - 20,000) (€155.15-310.38) to imprisonment (from six months to one year) depending on drug consumed. The sentence range for a person found in possession of a small quantity of an illicit drug is between six months to one year imprisonment, in case possession is proven to be intended for personal consumption. Possession was distinguished from consumption. For both the penalty is between six and twelve months imprisonment, provided possession is of small quantity.

Capital punishment exists in India, but is reserved for ‘rarest of rare’ cases (UNODC ROSA, 2007; expert’s comments).

3.3 Demand reduction: Experimental/recreational drug use + problematic use/chronic-frequent use

Additional information

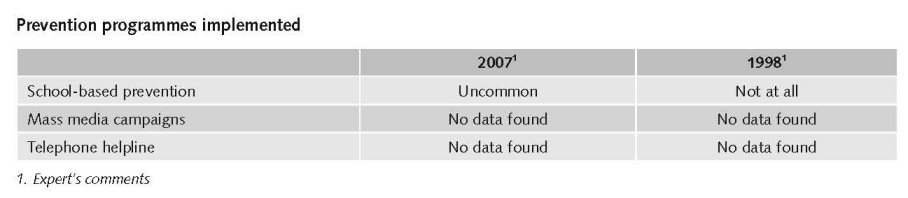

There is not much information available about nationwide preventive activities (expert’s comments).

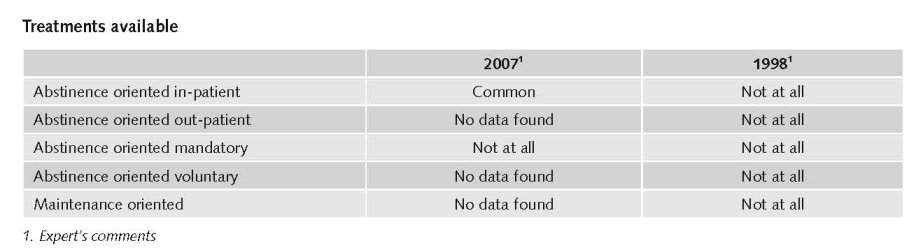

Main focus

Abstinence-oriented treatment (detoxification and rehabilitation / in-patient treatment centres according the Therapeutic Community and 12 steps approach) are the traditional main focus. Only recently Opiate Substitution Treatment (OST) got accepted and only buprenorphine. Methadone treatment is still prohibited (expert’s comments). India has yet to formulate a national policy on the issue related to substitution treatment (NACO, 2006).

In India, where estimates suggest that there are over one million people who inject drugs, there are thirty-five sites providing locally produced buprenorphine for limited periods, taken sublingually (Cook & Kanaef, 2008).

In 2004/2005, 81,802 people were in drug treatment, of which 61.3% opiates, 15.5% for cannabis, 1.5% cocaine, 0.2% amphetamines, 0.9% inhalants and 4.1% sedatives (UNODC, 2008).

The number of treatment centres (de-addiction) is judged as not sufficient. There are 432 abstinence-oriented treatment centres in India. Treatment facilities are available in the main cities only, and they all follow the same model. OST (buprenorphine) is available in some cities/region. There is nearly no after care and only a few day care centres in India (expert’s comments).

Priorities of drug treatment covered by policy papers and/or law

The NDPS act includes among others the following elements:

• Section 7A providing for a National Fund; among others for identification, treatment, rehabilitation and supply of drugs to drug dependent persons where such use is a medical necessity;

• Section 71 authorises the government to set up treatment centres and make rules for supply of drugs consistent with the Act and where such supply is a medical necessity;

• Section 39 allows a court to divert in lieu of sentencing an addict who:

- is convicted for consumption or offence involving a small quantity

- with his consent

- to detoxification at centres maintained or recognized by the government

- after entering bond with or without sureties to

- submit treatment progress report after one year

- abstain from commission of offence.

• Section 64A – Any addict, who:

- is charged with consumption or offence involving small quantity

- volunteers to undergo detoxification at centres maintained or recognised by government and

- undergoes treatment shall not be liable to prosecution;

- Immunity may be withdrawn in case of incomplete treatment.

- (UNODC ROSA, 2007; expert’s comments).

Minimum standards of care have been developed by the TT Ranganathan Clinical Research Foundation, based in Chennai, South India.

All treatment facilities are bound by these guidelines. These standards introduced in 2001, include guidelines on treatment to be offered, the scope of medical care, activities for psychological care, providing psychological care to families and the social network of the addict, after-care/ follow up and rehabilitation services, records to be maintained, the development of manuals (medical manual, therapy manual, administrative manual, network directory) (expert’s comments).

3.4 Harm reduction

3.4.1 HIV and mortality

Only recently harm reduction was put on top of the political agenda, as HIV got a major issue in India. The National Aids Control Organization (NACO) now fully supports (and subsidises) harm reduction interventions: OST, day care centres and needle and syringe exchange.

Harm reduction interventions exist in a number of big cities. The coverage of harm reduction is increasing in recent years. Before drug-use related harm was considered a problem mainly for North-East India only. North-East India has the best coverage with harm reduction interventions (expert’s comments).

In the last year, the number of NSP sites is reported to have increased in China, India, Malaysia, Myanmar, Taiwan and Nepal (small increase), although decreasing in Bangladesh (Cook & Kanaef, 2008).

In India, Bangladesh and Nepal, the most commonly injected drugs are heroin, buprenorphine and pharmaceutical drugs. In India, a crudely refined heroin base known as ‘brown sugar’ is most commonly injected. People injecting drugs are reported to be predominantly poly-drug users (Cook & Kanaef, 2008).

Priorities of harm reduction policy covered by policy papers and/or law

The National AIDS Control Programme Implementation Plan, Phase III, 78 (2006-2011) is focussing on prevention of HIV and STD among vulnerable groups such as IDU. Priorities are specific services for high risk groups linking prevention, care and support. It mentions the following components targeting IDUs:

• Detoxification, abstinence oriented treatment and rehabilitation;

• Needle exchange;

• Substitution therapy;

• Abscess management and other health services.

(NACO, 2006)

In India, there is an explicit supportive reference to harm reduction in national policy documents (Cook & Kanaef, 2008).

3.4.2 Crime, societal harm, environmental damage

No information found on interventions/measures to reduce harm for society.

References

Consulted experts

D. Daniels, Director, SAHAI Trust, Chennai.

M. Dharan, Outreach worker, SAHAI Trust, Chennai.

D. Gaspar, President, Hopers Foundation Harm Reduction CBO, Chennai.

K. Krisnan, Secretary, Hopers Foundation Harm Reduction CBO, Chennai.

I. Kumar, Deputy Director General, Narcotics Control Bureau, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India, New Delhi.

B. Langhkam, Coördinator OST NE India, Emmmanuel Hospital Association.

R.K. Raju, Policy officer, SHARAN, New Delhi.

S. Ranganathan, Honorary secretary, TT Ranganathan Clinical Research Foundation Chennai.

L. Samson, President, SHARAN/ Indian Harm reduction Network, New Delhi.

N. Shrivastava, Narcotics Control Bureau, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India, New Delhi.

T. Tandon, Senior technical and policy advisor, Lawyer’s Collective New Delhi.

Y. Thirumagal, Freelance consultant, Chennai.

R. Walia, Project coordinator Precursor Control Project for South & South West Asia, UNODC New Delhi.

Documents

Chandrasekaran P, Dallabetta G, Loo V, Rao S, Gayle H, Alexander A. Containing HIV/AIDS in India: the unfinished agenda. Lancet Infect Dis 2006, 6: 508–21.

CIA. The World Factbook: India. Available: www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/in.html, last accessed 18 December 2008.

Cook C, Kanaef N. Global state of harm reduction 2008. Mapping the response to drug-related HIV and hepatitis C epidemics. London, International Harm Reduction Association (IHRA), 2008.

INCB (International Narcotics Control Board 2007). Report. United Nations, Vienna, 2008.

Kumar S. Rapid Situation and Response Assessment of Drugs and HIV in Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Nepal and Sri Lanka: a regional report, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime - Regional Office for South Asia, New Delhi, 2008.

Mathers BM, Degenhardt L, Phillips B, Wiessing L, Hickman M, Strathdee SA et al. for the 2007 Reference Group to the UN on HIV and Injecting Drug Use. Global epidemiology of injecting drug use and HIV among people who inject drugs: a systematic review, 2008.

NACO (National AIDS Control Organisation). Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, National AIDS Control Programme Phase III (2006-2011), New Delhi, 2006.

NACO, HIV Sentinel Surveillance and HIV estimation 2006. NACO, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, 2007.

NACO, Note on HIV Sentinel Surveillance and HIV Estimation, 2008.

NCB (Narcotics Control Bureau). Annual Report, 2006.

Raju RK, Social Consequences of Drug Use in India. Society for Service to Urban Poverty. Sharan, 2008.

Tandon T. Specific Law Relating to Specific Groups: People using drugs. National Judicial Academy, 2008.

UNDCP (United Nations International Drug Control Programme). Studies on Drugs and Crime. Global Illicit Drug Trends 2000. Statistics. Vienna, UNDCP, 2001.

UNGASS. Country Progress Report. India, Reporting Period: January 2006 to December 2007, 2008.

UNODC (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime). World Drug Report 2007. Vienna, UNODC, 2007.

UNODC. World Drug Report 2008. Vienna, UNODC, 2008.

UNODC. World Drug Report 2008: Global ATS Assessment. Vienna, UNODC, 2008a.

UNODC, MSJE & UNESCO (United Nations office on Drugs and crime- Regional Office for South Asia and Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment & UNESCO). Extent, Pattern and Trends of Drug Abuse in India, 2004.

UNODC ROSA. Legal and Policy concerns related to IDU harm reduction in SAARC countries. Lawyers’ Collective 2007: 51-66

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|