Appendix to report 4: country reports HUNGARY

| Reports - A Report on Global Illicit Drugs Markets 1998-2007 |

Drug Abuse

HUNGARY

1 General information

Location:

Central Europe, northwest of Romania

Area: 93,030 sq km

Land boundaries/coastline:

2,185 km / 0 km (landlocked)

Border countries:

Austria 366 km, Croatia 329 km, Romania 443 km, Serbia 166 km, Slovakia 676 km, Slovenia 102 km, Ukraine 103 km.

Population:

9,930,915 (July 2008 est.)

Age structure:

0-14 years: 15.2% (male 774,092/female 730,485)

15-64 years: 69.3% (male 3,393,630/female 3,488,011)

65 years and over: 15.6% (male 559,483/female 985,214) (2008 est.)

Administrative divisions:

19 counties, 23 urban counties, and 1 capital city

GDP (purchasing power parity):

$191.7 billion (2007 est.)

GDP (official exchange rate):

$138.4 billion (2007 est.)

GDP- per capita (PPP):

$19,300 (2007 est.) (CIA World Factbook)

Drug research

There is a considerable research community consisting of a number of individual drug researchers working at different institutes (universities, semi-governmental institutes, etc.) working on research and monitoring on various subjects in different fields (medical, epidemiological, criminological, sociological, etc.). Epidemiological research has long been a tradition in Hungary, although research into the effectiveness of interventions is rarely found. The National Focal Point, based at the National Centre for Epidemiology, which also conducts and initiates research, collects all research reports available in Hungary and disseminates their results via its website and newsletter. Scientific journals and a new electronic database on research, which will be available soon, are examples of other dissemination channels in the country (Country overview).

Main drug-related problems

The main drug problem in Hungary is consumption followed by trafficking of especially heroin as a chain in the Balkan route. Production plays no significant role.

2 Drug problems

2.1 Drug supply

2.1.1 Production

No data found.

2.1.2 Trafficking

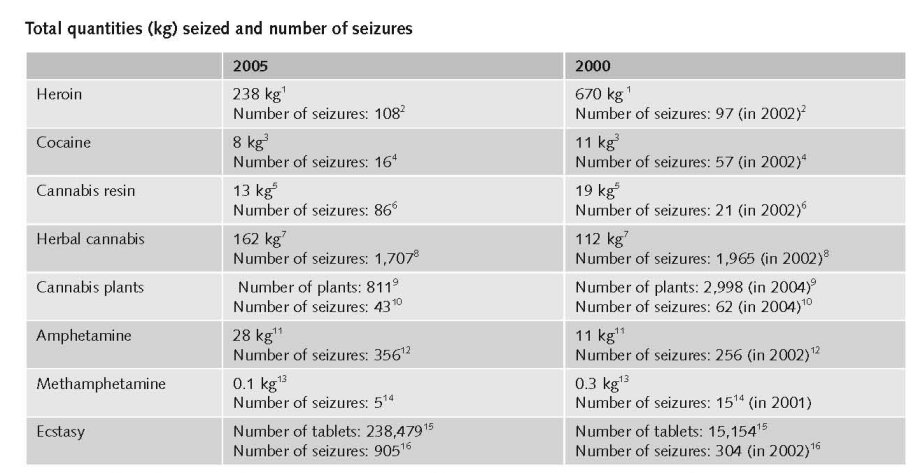

1. Quantities (kg) of heroin seized, 1995 to 2005 - EMCDDA Table SZR-8-SEIZURE-HEROIN-QUANTITY.htm

2. Number of heroin seizures, 1995 to 2005 - EMCDDA Table SZR-7-SEIZURE-HEROIN-NUMBER.htm

3. Quantities (kg) of cocaine seized, 1995 to 2005 - EMCDDA Table SZR-10-SEIZURE-COCAINE-QUANTITY.htm

4. Number of cocaine seizures, 1995 to 2005 - EMCDDA Table SZR-9-SEIZURE-COCAINE-NUMBER.htm

5. Quantities (kg) of cannabis resin seized, 1995 to 2005 - EMCDDA Table SZR-2-CANNABIS-QUANTITY.htm

6. Number of Cannabis resin seizures, 1995 to 2005 - EMCDDA Table SZR-1-SEIZURE-CANNABIS-NUMBER.htm

7. Quantities (kg) of herbal cannabis seized, 1995 to 2005 - EMCDDA Table SZR-4-SEIZURE-HERBAL-CANNABIS-QUANTITY.htm

8. Number of herbal cannabis seizures, 1995 to 2005 - EMCDDA Table SZR-3-SEIZURE-HERBAL-CANNABIS-NUMBER.htm

9. Quantities (number of plants) of cannabis plants seized, 1995 to 2005 - EMCDDA Table SZR-6-SEIZURE-CANNABIS-PLANTS-QUANTITY.htm

10. Number of seizures of cannabis plants, 1995 to 2005 - EMCDDA Table SZR-5-SEIZURE-CANNABIS-PLANTS-NUMBER.htm

11. Quantities (kg) of amphetamine seized, 1995 to 2005 - EMCDDA Table SZR-12-SEIZURE-AMPHETAMINES-QUANTITY.htm

12. Number of amphetamine seizures, 1995 to 2005 - EMCDDA Table SZR-11-SEIZURE-AMPHETAMINE-NUMBER.htm

13. Quantities (kg) of Methamphetamine seized, 2001 to 2005 - EMCDDA Table SZR-18-SEIZURE-METHAMPH-QUANTITY.htm

14. Number of Methamphetamine seizures, 2001 to 2005 - EMCDDA Table SZR-17-SEIZURE-METHAMPH-NUMBER.htm

15. Quantities (tablets) of ecstasy seized, 1995 to 2005 - EMCDDA Table SZR-14-SEIZURE-XTC-QUANTITY.htm

16. Number of ecstasy seizures, 1995 to 2005 - EMCDDA Table SZR-13-SEIZURE-XTC-NUMBER.htm

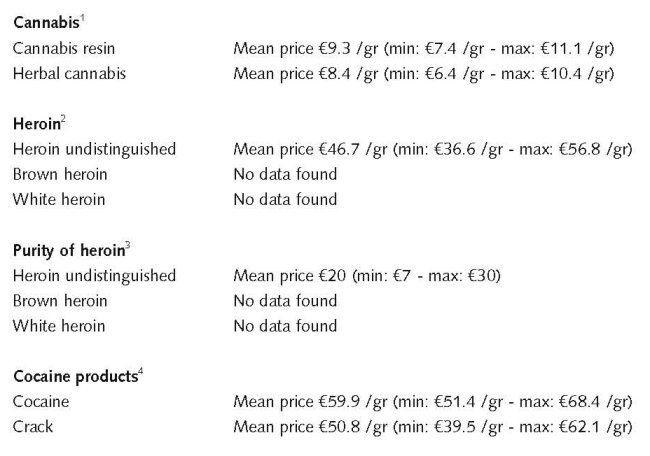

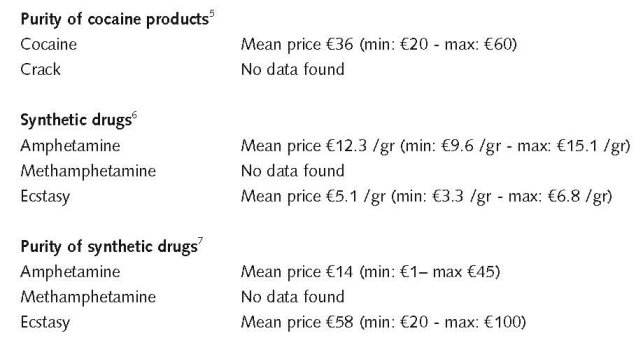

Prices reported in National report 2007 showed a decrease compared to the 2006 report: the average price of cannabis resin, cocaine, amphetamine, ecstasy and LSD decreased, while heroin (gr) became more expensive compared to the average price last year (National Report, 2007).

Hungary is a transit country for heroin trafficked across in the Middle East region and transported to Western Europe via the Balkan route. It has been discovered in the last two years that criminal groups operating via the Balkan route, mainly involved in heroin smuggling, also take part in the smuggling, sale and production of synthetic drugs (Country overview).

2006 figures show that the number of seizures for heroin, cocaine and amphetamines has been increasing in recent years across many of the main drug types: heroin (2005:108 seizures; 2006: 114 seizures) cocaine (2005: 16; 2006:113), amphetamines (2005: 356; 2006:368). Furthermore, in 2006, 145 ecstasy seizures were undertaken with a total of 138 278 tablets. However, when compared to 2005 there was a significant decrease in both the quantity and the number of ecstasy seized, with a total of 105 seizures in 2005. The quantity of seized tablets did not decrease proportionally with the number of seizures as most of the ecstasy tablets originated from a single large seizure in 2006 (Country overview).

Even though there was no significant change in the number of seizures, the quantity of seized herbal cannabis and cannabis plant increased significantly compared to the two previous years (National Report, 2007).

More people interviewed had information on the price of amphetamine than ecstasy. This fact confirms other changes in different areas of the drug problem (more amphetamine seizures, etc.), which imply that amphetamines has become more widespread on the drug market (National Report, 2007).

1. Price of cannabis at retail level, 2005 - EMCDDA Table PPP-1 Part (i)-PRICE-CANNABIS.htm

2. Price of heroin at retail level, 2005 - EMCDDA Table PPP-2 Part (i)-PRICE-HEROIN.htm

3. Purity of heroin at retail level, 2005 - EMCDDA Table PPP-6 Part (i)-PURITY-HEROIN.htm

4. Price of cocaine products at retail level, 2005 - EMCDDA Table PPP-3 Part (i)-PRICE-COCAINE.htm

5. Purity of cocaine products at retail level, 2005 - EMCDDA Table PPP-7 Part (i)-PURITY-COCAINE.htm

6. Price of synthetic drugs at retail level, 2005 - EMCDDA Table PPP-4 Part (i)-PRICE-SYNTHETIC.htm

7. Purity of synthetic drugs at retail level, 2005 - EMCDDA Table PPP-8 Part (i)-PURITY-SYNTHETIC.htm

Estimated retail value in 1998:

Heroin €16-32 / street dose (National Report, 1999).

No further information on prices around 10 years ago.

2.2 Drug Demand

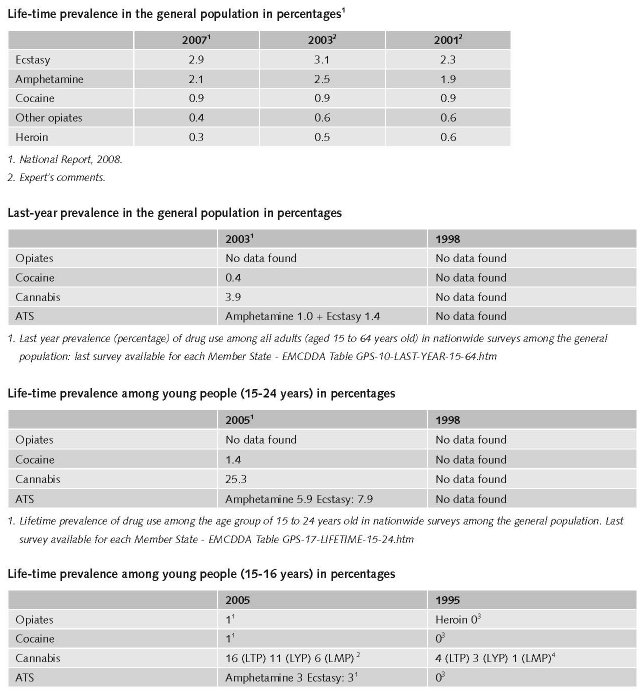

The last general population survey on drug use was conducted in Hungary in 2007, and its results will be available in the 2008 national report to the EMCDDA. Results of the 2003 general population survey reveal that lifetime prevalence of illicit drugs among the population aged 18–54 was 11.4%. Lifetime prevalence for cannabis was 9.8%, 3.1% for ecstasy, 2.5% for amphetamines and below 2% for other substances, except for sedatives and/or tranquillisers (22.2%) (Country overview).

Available data for the age group 18–34 years old showed that 20.1% reported lifetime experience with illegal drugs and 17.4% reported to have used cannabis at least once in their life. Lifetime prevalence for this age group was lower for all other illicit substances. Lifetime experience with ecstasy and amphetamines were in second and third place, at 5.6% and 4.5% respectively (Country overview).

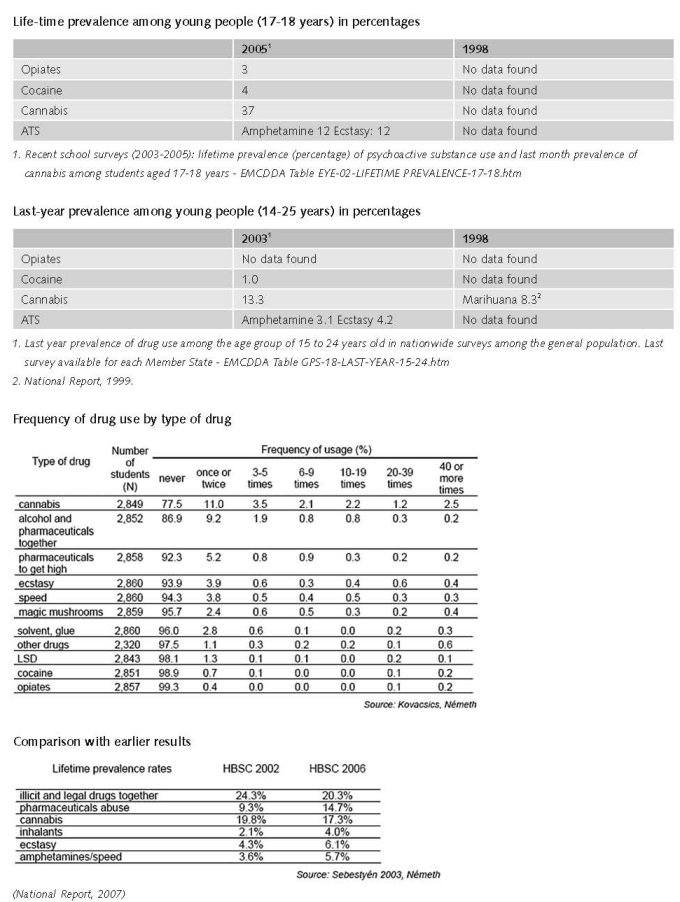

Nationwide data on drug use among students are based on the ESPAD surveys conducted in 1995, 1999, 2003 and 2007. The results of the ESPAD survey 2007 will be available at the end of 2008. A comparison of the results among 15–16-year-olds revealed an increase in illegal drug use between 1995 and 1999. The increase in lifetime prevalence of illicit drug use between 1999 and 2003 was exclusively due to the increase of cannabis use. While lifetime use of any illicit substance other than cannabis increased from 1.4% in 1995 to 5.5% in 1999, and stabilised at 5% in 2003, lifetime experience of cannabis increased further from 4.5% in 1995 to 11.5% in 1999 and 16% in 2003. An increase was also observed for lifetime use of amphetamines: 0.4% in 1995, 2.3% in 1999 and 3.1% in 2003 (Country overview).

The 2006 HBSC survey showed that 20.3% of 15–17-year-old students have used an illicit substance at least once. Lifetime prevalence of cannabis use was reported by 17.3% of the respondents. Lifetime prevalence of respectively ecstasy, amphetamines/speed were 6.1% and 5.7%. The use of all drugs was found to be influenced by gender and age: prevalence of drug use among male students was higher than among female students, with the exception of prevalence for misuse of pharmaceutical products. Compared to the previous HBSC results (2002), an increase in the lifetime prevalence was recorded for all substances (Country overview).

2.2.1 Experimental/recreational drug users in the general population

1. Recent school surveys (2003-2005): lifetime prevalence (percentage) of psychoactive substance use among students aged 15-16 years old - EMCDDA Table EYE-01-LIFETIME PREVALENCE-15-16.htm

2. ESPAD 2003 school surveys: lifetime (LTP), last year (LYP) and last month (LMP) prevalence of cannabis use among students 15–16 years - EMCDDA Table EYE-05 Part (i)-CANNABIS-15-16.htm

3. Recent school surveys (2003-2005): lifetime prevalence (percentage) of psychoactive substance use among students aged 15-16 years old - EMCDDA Table EYE-01-LIFETIME PREVALENCE-15-16.htm

4. All ESPAD school surveys: prevalence and patterns of cannabis use among students 15–16 years - EMCDDA Table EYE-07 Part (i)-CANNABIS-15-16.htm

2.2.2 Problematic drug users/chronic and frequent drug users

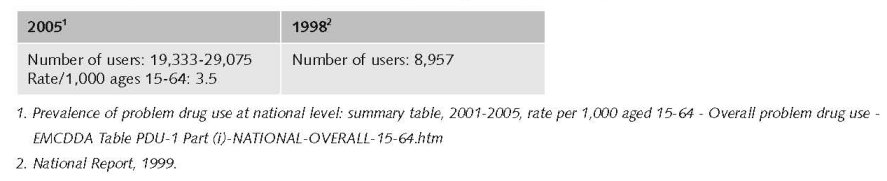

In Hungary the first estimate for the prevalence of hidden problem drug use was conducted in 2003. In 2005, the rate for problem drug use is 3.5 per 1 000 inhabitants. In 2006 a more recent study using the capture-recapture method estimated a total number of 24,171 problem drug users (in a range between 19,307 and 29,035). The number of problem opiate users is estimated at around 4,000 people in Budapest (the number ranged between 3,848–4,223, according to the various methods applied) (Country overview).

The number of problematic/chronic-frequent users (in the general population)

The number of injecting drug users (in the general population)

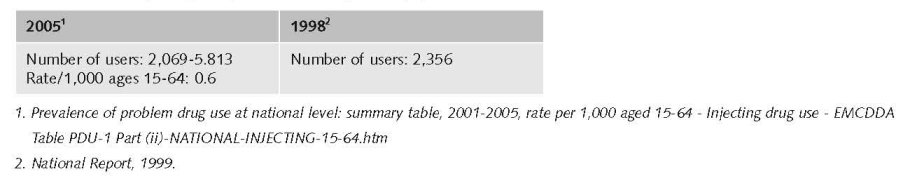

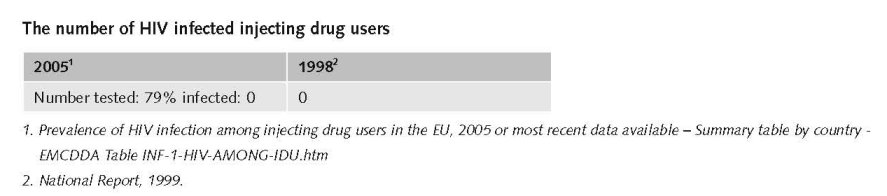

Injecting drug use was decreasing between 2002-2005 (National Report, 2007).

There is no information on the number of injecting drug users among younger people (< 20 years).

2.3 Drug related Harm

2.3.1 HIV infections and mortality (drug related deaths)

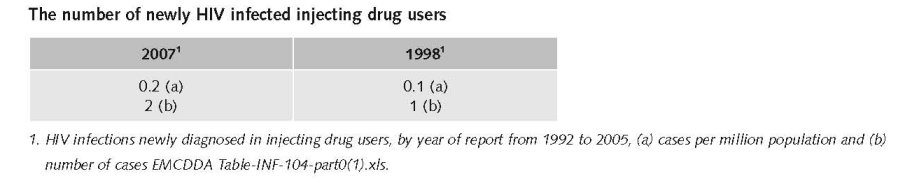

In 2006, 168 HIV tests were performed. 81 newly revealed HIV positive cases were reported, thus the incidence of HIV infections (8 cases/million inhabitants) was lower compared to the year before (10,5 cases/million inhabitants). The mode of infection was only known in two-thirds of the newly registered HIV cases. This year no HIV infections were discovered among people in the IDU risk group. No newly diagnosed AIDS patients were reported among IDUs, either (National Report, 2007).

Based on the incidence data reported in 2006 and the HIV tests of 300 injecting drug users (IDUs) it can be concluded with a high probability, that in the Hungarian IDU population – similarly to previous years – the number of HIV infections is very low. Among people treated at specialised out-patient treatment centres and people taking advantage of low-threshold services, 28.9% HCV prevalence was measured. In 2006, the number of injectors distributed by needle exchange programmes increased by 56%, while the number of clients grew by 84%. The per capita number of injectors – implying secondary syringe exchange – that had been on the rise, decreased in 2006 for the first time since 2003. On the other hand, the number of clients has reached its highest value ever. This may mean that the programmes reach more and more drug users directly (National Report, 2007).

2.3.2 The number of drug related deaths by overdose

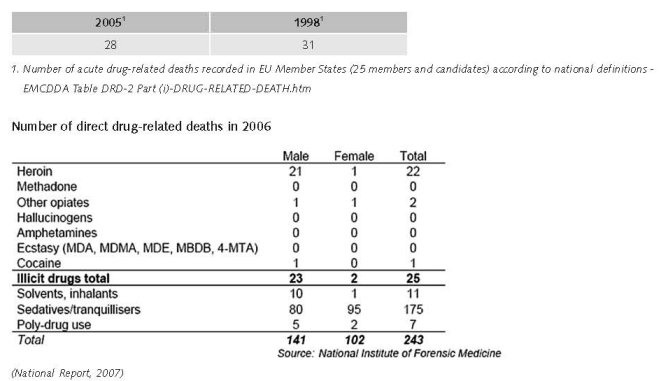

The number of reported deaths due to illicit drug use further decreased in 2006 compared with previous years. 25 overdose death cases were reported in 2006, compared to 28 in 2005 and 34 in 2004. Conversely, the number of fatal heroin overdoses increased, from 8 in 2004, to 13 in 2005, and 22 in 2006, thus accounting for the vast majority of DRDs. One death was related to a cocaine overdose, and two to other opiate substances. As regards the distribution by age and sex, we may say that the majority of cases involved males (22 cases out of 25) and the mean age was 30.2 years (Country overview).

3 Drug policy

3.1 General information

3.1.1 Policy expenditures

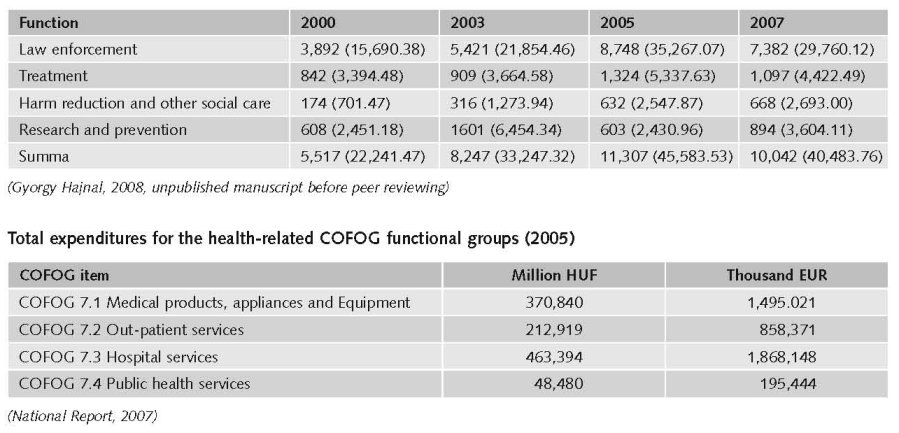

According to the experts the drug policy expenditures have increased the past ten years.

Public expenditures in million HUF (and in thousand EUR1), estimates based on the methodology proposed by the EMCDDA. The figures calculated according to the inflation rate relevant for the given years.

Labelled drug-related budget expenditures identifiable on the basis of the national budget report is, only a small fragment of total drug-related budget expenditures for the same year. On the basis of applying the methodology foreseen by the EMCDDA Reporting Guidelines the total amount of drug-related expenditures in the field of public order and safety is 12-28% higher than the benchmark set by the 2006 research. There was a particularly large deviation with regards to the expenses of the judiciary. Drug-related budget expenditures in the field of health services (COFOG 7.1-7.4) were, within the scope and the limits of the current work, impossible to estimate (National Report, 2007).

3.1.2 Other general indicators

Hungary’s first ever national strategy on drugs covers the period 2000–09. It was complemented by a national action plan which was implemented in 2004 and which is now replaced by another strategy, Government Decree 1094/2007 (XII. 5.) on government tasks related to the implementation of the objectives of the national strategy on reducing the drug problem. The national strategy focuses on illicit drugs, is comprehensive and covers the following pillars: community cooperation; prevention; social work/treatment/ rehabilitation; supply reduction; international cooperation; and monitoring. Specific short-, medium- and long-term objectives and achievements are set for these pillars (Country overview).

The implementation of the Drug Strategy was supported by legal provisions (National Report 2002). One example is the Amendment to the Act IV. of 1978 on the Criminal Code by Act II. of 2003 aiming among others at facilitating the implementation of the National Drug Strategy (National Report, 2004).

1 €1 = 248.0501 HUF. Exchange rate published in National Report 2008.

Based on data of the Public Prosecutor’s Office, 2,484 persons were sentenced for drug related offences in 2006. These offenders committed 2,874 offences, which they were called to account for on the following legal grounds:

• 1,806 offenders were sentenced for using type offences prohibited by Section 282 and Section 282/A of the Criminal Code;

• 182 offenders were sentenced for trafficking type offences prohibited by Section 282 and Section 282/A of the Criminal Code;

• 148 persons were sentenced for offences prohibited by Section 282/B (using or Trafficking type offence to the injury of a person under the age of eighteen or involving such a person);

• 348 persons were sentenced for conducts as prohibited by Section 282/C (drug addicted persons committing a using or trafficking type offence);

• Nobody was sentenced for an offence prohibited by Section 283 (Misuse of materials used for producing narcotic drugs) of the Criminal Code (National Report, 2007).

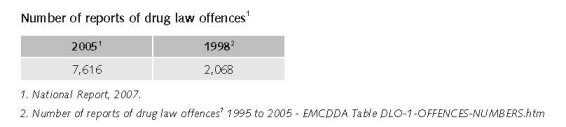

The general term ‘reports for drug law offences’ is used since definitions and study units differ widely between countries.

For definitions of the term ‘reports for drug law offences’, refer to Drug law offences – methods and definitions.

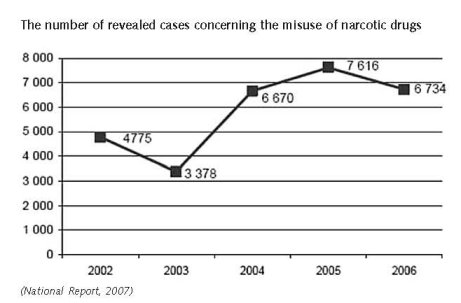

The number of cases concerning the misuse of narcotic drugs decreased by 13.4%, compared to 2005, with a total of 7,616 cases in 2005 and a total of 6,734 cases in 2006. Furthermore, Misuse of narcotic drug offences made up 1.6% of total crime activity in 2006. This rate does not indicate the full extent of crime related to drugs, such as crimes committed by drug users in order to acquire drugs or other organised crime (Country overview).

The number of revealed offenders was 15% less in 2006 than the number of misuse of narcotic drug cases detected by the authorities. This means that every sixth offender against whom the proceedings were initiated for misuse of narcotic drugs committed at least two offences. In 2005 this ratio was 7%, and never went above that in the years prior to 2005 either. The main reason for this is the criminal legislation (National Report, 2007).

The number of revealed cases concerning the misuse of narcotic drugs decreased by 13.4% compared to 2005 (6,734 in 2006, 7,616 in 2005).

Misuse of narcotic drug offences made up 1.6% of total crime activity in 2006. This rate does not indicate the full extent of crime related to drugs (e.g. crimes committed by drug users in order to acquire drugs, other organized crime) (National Report, 2007).

Conducts of offence denoting the “production, manufacturing, acquisition, possession, importing” of narcotic drugs for demand-related activities of personal use, made up for 90.9% of all revealed offences of misuse of narcotic drugs in 2005 (89.8% in 2006). “Use” as such had a rate of 0.8% – this legal fact was still included in statistics because proceedings initiated prior to the amendments in 2003 were closed in 2005. Thus we can say that demand-related offences for personal use have a share of 91.7%. Supply-related criminal acts (denoting offering, supplying, distributing, trafficking narcotic drugs) account in 2005 for 8.3% of all revealed offences (in 2006 for 7%).

Offences involving the activities “production, manufacturing, acquisition, possession, importing” of narcotic drugs which include most often personal use, made up 89.8% (90.9% in 2005) of all revealed drug offences. Compared to that, supply-related criminal acts (denoting offering, supplying, distributing, trafficking narcotic drugs) do not even account for one-tenth (7%) of all reported offences. A significant proportion of misuse of narcotic drug offences is constituted by demand-related behaviours, especially offences committed by occasional users (National Report, 2006; 2007).

The offences where the subject of crime was any narcotic drugs, increased by 714% between 1993 and 1998 (if 100%=302 in the initial year of this data collection in 1993). While in the same period the offences of heroin increased by 1870%, (if 24=100% in the initial year of this data collection in 1993) (National Report, 1999).

Expert comments

The above mentioned decrease of revealed cases concerning the misuse of narcotic drugs cannot be accounted for by any legal changes. It is possible that the investigating authority’s interest in and/or capacity for uncovering these offences decreased somewhat.

3.2 Supply reduction: Production, trafficking and retail

Main focus in Hungary of supply reduction is on retail and on trafficking.

Priorities of supply reduction covered by policy papers and/or law

The drug-related sections of the Hungarian Criminal Code (HCC) were considerably amended in 2003. This amendment was based on the principle that both demand and supply must be reduced, and that there is a need to differentiate approaches towards drug consumers, where prevention, treatment and criminal law must all be taken into account. The HCC was reorganised into sections covering possession, trafficking, minors, addicts, exemptions from punishment, and drug precursors. The amendment introduced more detailed provisions (lower maximum sentences if the offender is an addict, detailed and differentiated regulations on drug-related crimes if persons under 18 years are involved), and most importantly, made the treatment option again available both for consumers and addicts. It also removed ’consumption’ as a specific offence — although in an indirect way consumption remains punishable, as possessing and acquiring drugs remains an offence (Country overview).

In 1999 an amendment of the Penal Code, Section 282 and 282/A and 282/ B and 283 entered into force by March 1999. It foresees much higher penalties for drugs trafficking (5-15 years and also life long prison sentence), mainly if committed it in the framework of organised crime, or in armed form. The amendment re-introduced the punishment of drug consumption (as it was before 1993), however it makes possible beside the voluntary treatment other alternatives of imprisonment (as public work, or fine) in case of petty crime, or misuse of drugs (National Report, 1999).

All narcotics-related activity performed without authorisation is classified as a criminal offence. The definition of the “abuse of narcotic drugs” in the Criminal Code (Law No. IV of 1978) has been amended different times in the last two decades to make the rules on trafficking and dealing more strict (National Report, 2003).

Drug use is still a criminal offence (this was reintroduced in 1998), be it that the sentences are tougher for trafficking and dealing drugs than for using them (National Report 1999). The law (Section 282 of the criminal code) allows furthermore for treatment as alternative for imprisonment for drug use offences, but only in case the offenders are addicted, not offering or supplying drugs to others, etc (National Report 2003) or for minor offences (National Report, 2003).

3.3 Demand reduction: Experimental/recreational drug use + problematic use/chronic-frequent use

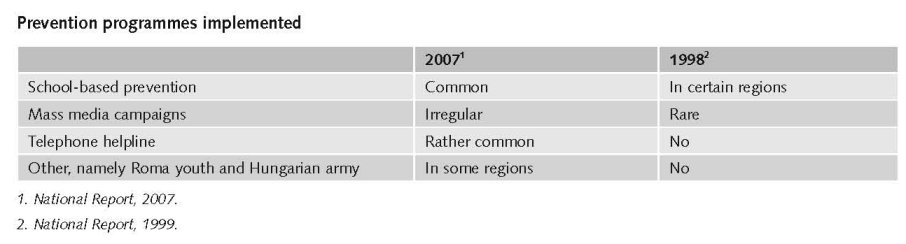

Universal prevention is specifically carried out within a school setting. During the school year 2005–06, 229 different prevention programmes were implemented within the school setting. The most common objectives of these programmes were: the provision of knowledge concerning drugs and health promotion; development of self-knowledge; and the development of refusal skills. These programmes were delivered through seven identified methods: lecturing, discussions, group work, visual presentation, material presentation, role-play and demonstration (Country overview).

As regards selective prevention, activities are targeted at recreational settings, ethnic minorities and youths. In 2006, six organisations carried out harm reduction/prevention activities in recreational settings. These organisations took part in more than 250 events, where they reached almost 28 000 youths. As regards ethnic minorities, joint peer counselling training programme for Roma and non-Roma youths were organised in 2006. In 2005, a new service targeted at youths in shopping malls was launched in Budapest and Pécs. This new service offer youths information on the different programmes in the form of structured or spontaneous group discussions, or individual consultations. Group discussions mostly involve questions of self-knowledge and issues which teenagers are mostly preoccupied with, such as relationships, love, sexuality and drug use. Besides providing a low-threshold service, one of the most important tasks of this service is to act as a filter and direct youths to the right places (Country overview).

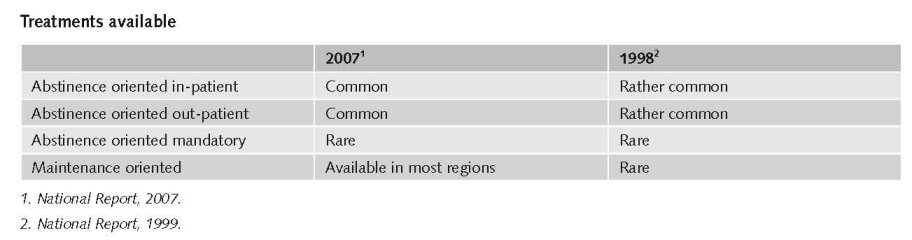

Year of introduction of methadone maintenance treatment (MMT): 1995 (Year of introduction of methadone maintenance treatment (MMT), high-dosage buprenorphine treatment (HDBT) and heroin-assisted treatment, including trials - EMCDDA Table HSR-1-METHADONE-INTRODUCTION.htm)

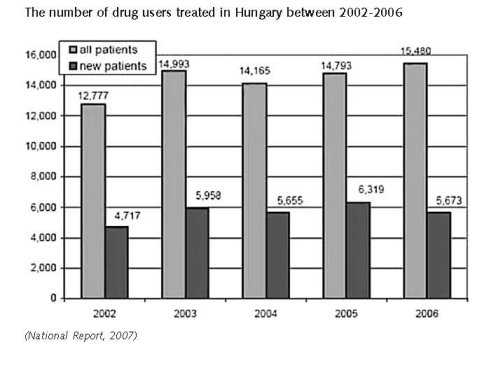

In 2006, the data collection system for treatment demand was provided by 453 treatment centres, out of which 329 were out-patient treatment centres, whereas 124 were in-patient treatment centres. In 2006, the number of drug users in treatment increased to a total of 15,480 compared to 2005, when a total of 14,793 clients in treatment were reported. In 2006, the number of clients entering treatment decreased to a total of 5,673, compared to the 6,319 clients in 2005 (Country overview).

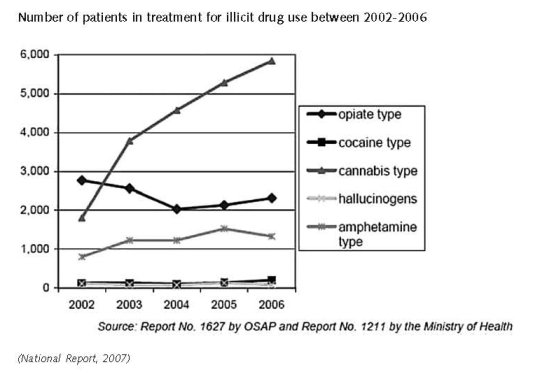

The number of heroin users in treatment and injecting users has been continuously decreasing since 2000. This trend was reversed in 2006, and both the number of heroin users in treatment and injecting users increased. In 2006 again, the number of patients in treatment for cannabis use was the highest; the number of amphetamine users decreased for the first time compared to the previous year. The share of cocaine users has further increased, while the number of hallucinogen users decreased (National Report, 2007).

In 2006, cannabis was the primary substance of abuse among all clients in treatment, with a ratio of 37.9%, followed by 15% for opioids and 4.4% for amphetamines. Similarly, among clients entering treatment cannabis was reported as the primary substance of abuse at 54.1%, followed by 7.4% for opioids and 5.3% for amphetamines (Country overview).

Treatment for drug users is offered at various out-patient and in-patient facilities throughout Hungary. Facilities include specialised drug clinics and therapy-providing institutions, as well as psychiatric departments, therapeutic communities and crisis intervention departments. The need for developing out-patient institutions specialising in treatment for drug addicts was identified, and first services were established, in the 1980s. Overall, in 2006 there were 21 specialised out-patient treatment centres operating in 14 counties in Hungary. In-patient care is offered by psychiatric departments, departments of addiction, crisis intervention departments as well as by NGOs running therapeutic communities. Besides the 13 existing therapeutic communities, two new facilities were opened in 2006. Long-term rehabilitation is mainly provided by NGOs. The services they deliver are only partially medical or healthcare-related, and are dominated by social and welfare programmes such as work therapy and social reintegration (Country overview).

In 1994, the first methadone maintenance treatment programme was launched in Hungary, and this is currently available in eight institutions in six towns nationwide. In 2006, the total number of clients in methadone maintenance treatment was 853. Furthermore, the methodological guidelines of the Professional College of Psychiatry on methadone treatment of 2002 stipulate that methadone treatment can only be initiated by treatment centres. At the end of 2007, the registration process of Suboxone was initiated (Country overview).

On the whole, it can be concluded that the health care treatment chain – similarly to the previous year – is still quite irregular and deficient in 2006. Considering the number of clients, there are great differences between the capital and the other parts of the country (National Report, 2007).

Priorities of demand reduction covered by policy papers and/or law

There are no separate legal regulations on drug prevention and drug treatment. These tasks are covered in general legislation on public education and health. This has not changed since 1998, (National Report 1999) be it that some education and health laws have been adapted. School drug education is for instance covered by the Law on Public Education which was adapted in 2002 specifying criteria and guidelines for health education in schools (National Report, 2003). Drug-free treatment is covered by general laws on heath care provision like Act CXXXII of 2006 (National Report, 2007).

The National Drug Strategy 2000-2009 set clear objectives increasing reach and quality of drug prevention and treatment. The Co-ordination Forums on Drug Affairs and the working groups of the Co-ordination Committee were installed to facilitate and support the local and nation-wide co-ordination of prevention and treatment and their co-operation with other professions (expert’s comments).

3.4 Harm reduction

3.4.1 HIV and mortality

A harm reduction approach has been present in Hungary for many years. However, only in recent years has it also received support at the professional and drug policy level. The ‘National strategy for the reduction of drug problems’ includes an obligation to integrate a harm reduction approach and harm reduction programmes. In practice however, the coverage of such programmes is limited. A number of low-threshold services provide counselling, referral to long-term treatment, social support and legal assistance. Needles and syringes are available across the country through six fixed needle and syringe programmes (two in Budapest and four in other cities), two mobile units in Budapest, five vending machines (one in Budapest), and eight street outreach programmes (three in Budapest and five in other cities). A total of 13 organisations are involved in needle and syringe exchange programmes in Hungary. In 2006, a total of 142 433 syringes were distributed with an exchange rate of 50% (Country overview).

Priorities of harm reduction covered by policy papers and/or law

Harm reduction services are for an important part covered by legal regulations of social care. Especially since 1999/2000 the legal fundament for law-threshold services and outreach work developed strongly, specifying (minimum) requirements and rules for these services (National Report 2007). This was supported by Ministerial regulations like the detailed rules of the operation of low-threshold services in regulation 3/2006. (V. 17.) of the Ministry of Youth, Family, Social Affairs and Equal Opportunity, which amended Regulation 1/2000. (I. 7.) of the Ministry of Social and Family Affairs on the professional requirements of employment in social institutions, its personal and material requirements, and the professional tasks and operation requirements of social institutions offering personal care (National Report, 2007).

3.4.2 Crime, societal harm, environmental damage

No information found on interventions/measures to reduce harm for society.

References

Consulted experts

Katalin Felvinczi, Director, National Institute for Drug Prevention, Budapest.

Documents

CIA. The World Factbook – Hungary. Available: www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/hu.html,

last accessed 15 November 2008.

Country overview: Hungary. Available: www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/country-overview/hu, last accessed

15 November 2008.

National Report to the EMCDDA, Hungary, 1999.

National Report to the EMCDDA, Hungary, 2003.

National Report to the EMCDDA, Hungary, 2004.

National Report to the EMCDDA, Hungary, 2006.

National Report to the EMCDDA, Hungary, 2007.

National Report to the EMCDDA, Hungary, 2008.

Van der Gouwe D, Gallà M, Van Gageldonk A, Croes E, Engelhardt J, Van Laar M, Buster M. Prevention and reduction of health-related harm associated with drug dependence: an inventory of policies, evidence and practices in the EU relevant to the implementation of the Council Recommendation of 18 June 2003. Utrecht, Trimbos Institute, 2006.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|