Appendix to report 4: country reports CANADA

| Reports - A Report on Global Illicit Drugs Markets 1998-2007 |

Drug Abuse

CANADA

1 General information

Location:

Northern North America, bordering the North Atlantic Ocean on the east, North Pacific Ocean on the west, and the Arctic Ocean on the north, north of the conterminous US

Area:

9,984,670 sq km

Land boundaries/coastline:

8,893 km/ 202,080 km

Border countries:

US 8,893 km (includes 2,477 km with Alaska)

Population:

33,212,696 (July 2008 est.)

Age structure:

0-14 years: 16.3% (male 2,780,491/female 2,644,276)

15-64 years: 68.8% (male 11,547,354/female 11,300,639)

65 years and over: 14.9% (male 2,150,991/female 2,788,945) (2008 est.)

Administrative divisions:

10 provinces and 3 territories

GDP (purchasing power parity):

$773 billion (2007 est.)

GDP ((official exchange rate):

$908.8 billion (2007 est.)

GDP- per capita:

$37,300 (2007 est.) (CIA The World Factbook)

Drug research

There are many researchers spread over several University Departments and there are specialised centres for addiction research in Canada (Centre for Addiction and Mental Health and the Centre for Addiction Research of British Colombia).

Main drug-related problems

The main drug related problems in Canada are production, trafficking and consumption (mainly of cannabis and ecstasy). Canada produces cannabis with developed technologies for its domestic drug market and export to the US. Canada has an increasing ecstasy production.

2 Drug problems

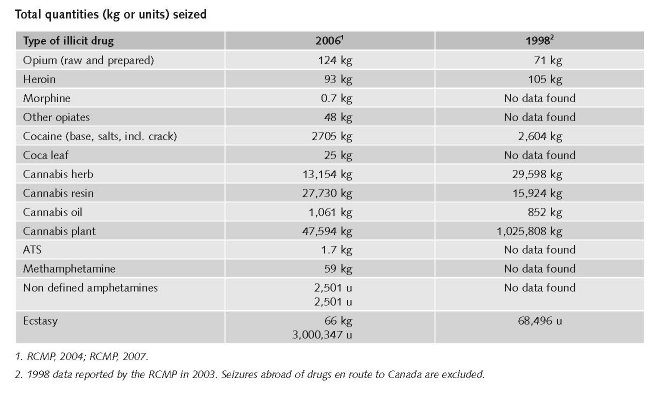

2.1 Drug supply

2.1.1 Production

Canada is not an important drug producing country. An exception may be made for the production of ecstasy.

2.1.2 Trafficking

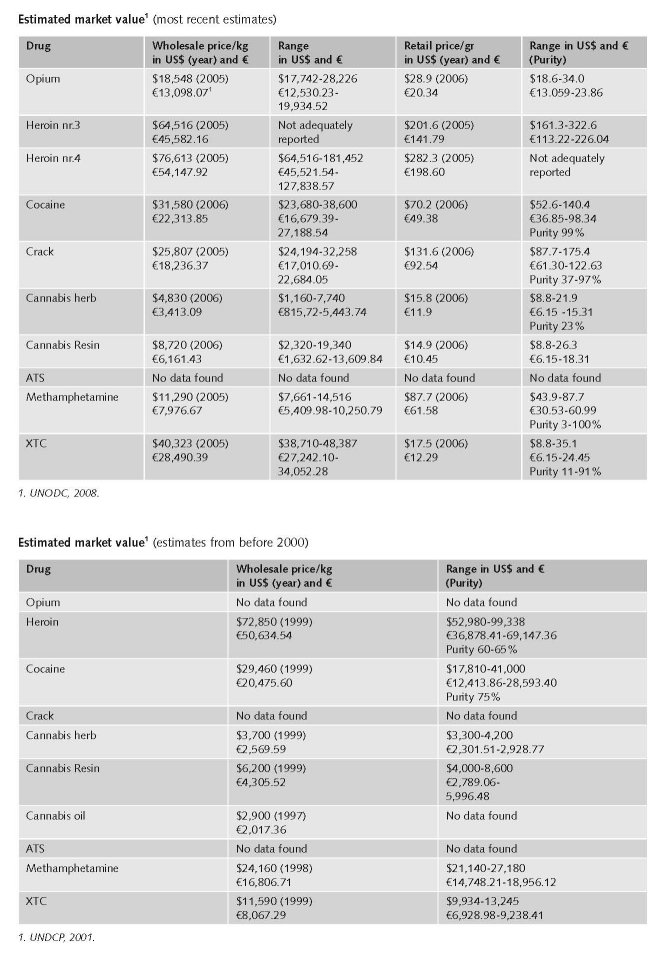

1 $1=€0.706172. Exchange rate 17 December 2008.

2.1.3 Retail/Consumption

No data found on retail and consumption.

2.2 Drug Demand

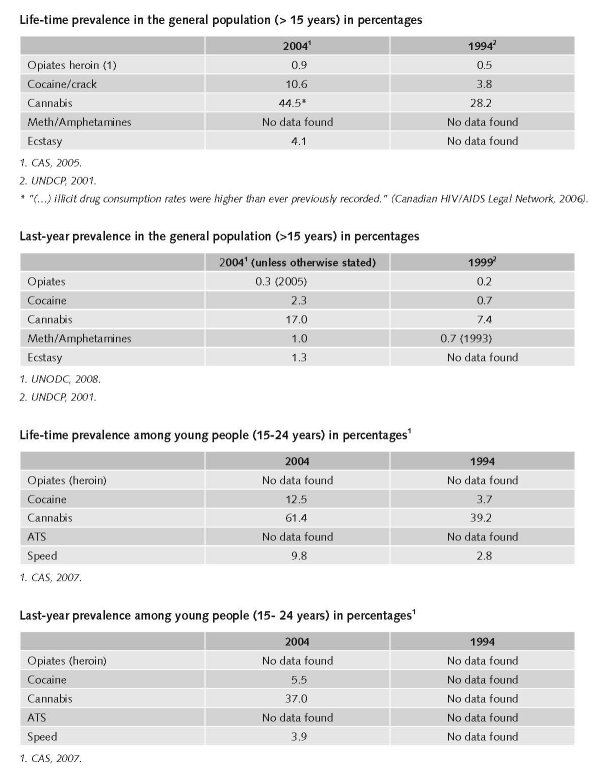

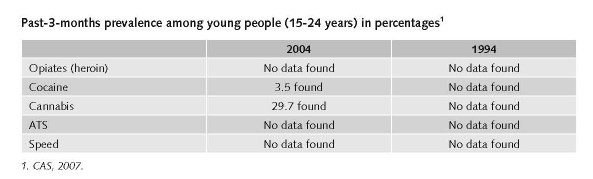

2.2.1 Experimental/recreational drug users in the general population

Among youth cannabis is the most frequently used illegal drug during lifetime (61.4), followed by hallucinogens (16.4%), then cocaine (12.5%), ecstasy (11.9%), speed (9.8%) and inhalants (1.8%).

Young people use more illegal drugs than adults. The use of any of 5 illegal drugs (24.2% versus 15.2%) and any of 6 illegal drugs (62.1% versus 42.3%).

Studies show “(…) that crack use has become increasingly prevalent in street drug-use populations across Canada in the past ten years although considerable local differences exist.” (Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse, 2006).

2.2.2 Problematic drug users/chronic-frequent drug users

There are no data on the number of problem drug users in the general population. A national expert survey suggested that there were more than 80,000 opioid users in Canada in 2003 (Popova et al., 2006).

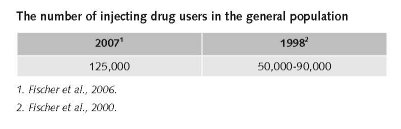

The number of IDUs in Canada (over the total population in 1999 of some 31 million) is estimated to range from 50,000 to 90,000 and has varied little throughout the last decade (Fischer et al., 2000).

In 2000-2001 there were an estimated 125,000 injection drug users in Canada, most of whom were using heroin and cocaine (Fischer et al., 2000).

The substantial difference is probably due to differences in methodology (expert’s comments).

No data found on the number of injecting drug users among younger people (< 20 years).

2.3 Drug related Harm

2.3.1 HIV infections and mortality (drug related deaths)

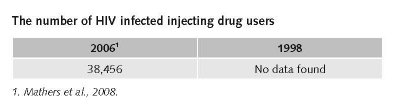

For 2006 it was estimated that 13.4% (2.9% - 23.8%) of 286,987 people who inject drugs (range 220,690 – 375,173) were infected with HIV.

Around 2000 HIV among injection drug users was increasing dramatically, with Vancouver having the highest rate in North America (Canadian Foundation for Drug Policy, 2001).

Public Health Agency of Canada, 2008: 5,465 cumulative adult HIV-positive test reports of injecting drug users (end of June 2007). The proportion of adult HIV-positive tests attributed to IDU has gradually decreased from 24.6% in 2001 to 19.3% in 2006 (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2008).

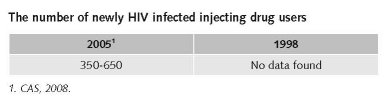

The estimated number of new HIV infections among IDU is 350-650 in 2005. The number of new HIV infections among people who inject drugs (IDU) appears to be decreasing overall. (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2008).

2.3.2 Drug related crime or (societal) harm

The long term trend in the number of police-reported drug offences has remained stable over the past 15 years. It must be noted that trends in drug offences are directed influenced by levels of police enforcement (Tremblay, 1999).

Much of the increase in police-reported drug offences can be attributed to a rise in offences for the possession of cannabis. Between 1992 and 2002 684 (11%) murder incidents in Canada were reported to be drug related. Of these, 176 (26%) were gang related (Desjardins & Hotton, 2004).

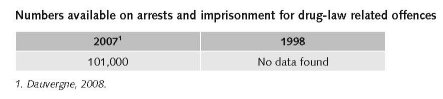

“The 2007 national crime rate reached its lowest point in 30 years. Canadian police services reported a 7% decline in crime, the third consecutive annual decrease.” (…) “Among the few crimes to increase in 2007 were drug offences and impaired driving, both of which tend to be influenced by police enforcement practices.” (Dauvergne, 2008).

Drug related violent activities are on the rise in 2003 in most areas in Canada, although the increase cannot be quantified through hard data (Royal Canadian Mounted Police, 2004). No other data found.

3 Drug policy

3.1 General Information

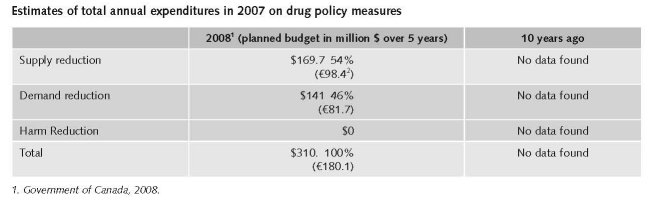

3.1.1 Policy expenditures

The three plans of the national anti-drug strategy of August 2008 cover several proposals.

1. Preventing illicit drug use $30 million (€17.4) million over 5 years;

2. Treating those with illicit drug dependencies by promoting collaboration among governments and supporting agencies to increase access to treatment services, approximately $111 million (€64.37 million);

3. Combating the production and distribution of illicit drugs by increasing law enforcement’s capacity to combat marihuana grow operations, synthetic drug production and distribution operations; $102 million (€59.15 million) over 5 years and an additional $67.7 million (€39.26 million) if the Enforcement Action Plan has passed i.e. the mandatory minimum penalties: (www.hc-sc.gc.ca/ahc-asc/activit/strateg/drugs-drogues-eng.php)

3.1.2 Other general indicators

Drug offence rates reached an all-time high in Canada in 2002, with almost 93,000 charges recorded under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act. Furthermore, three out of four prisoners in Canada are assessed as having issues related to substance abuse

The overall rate of drug offences was driven by cannabis offences, which accounted for about 6 in 10 drug offences. Possession of cannabis, which comprised three-quarters of all cannabis offences in 2007, rose by 6%.

Following five consecutive increases, cocaine offences remained stable while other drug offences, such as heroin, crystal meth and ecstasy, were up by 6% (Thomas, 2005).

Numbers available on arrests and imprisonment for use/possession for personal use

Much of the increase in police-reported drug offences can be attributed to a rise in offences for the possession of cannabis (Desjardins & Hotton, 2004).

2 CAD = € 0.579880. Exchange rate 17 December 2008.

3.2 Supply reduction: Production, trafficking and retail

Priorities of supply reduction covered by policy papers and/or law

There is currently less emphasis on harm reduction. Today’s National Anti-drug Strategy includes three action plans: preventing illicit drug use, treating those with illicit drug dependencies, and combating the production and distribution of illicit drugs. Harm reduction is not mentioned explicitly in this strategy (www.hc-sc.gc.ca/ahc-asc/activit/strateg/drugs-drogues-eng.php).

Ten years ago Canada’s Drug Strategy was pointing at the following activities for the next future: strengthening drug prevention (because this is most cost-effective), responding to the needs of young (and young adult) people as well as seniors, enhancing border interdiction activities, increasing efforts to reduce drug-related crime, identifying and assessing innovating approaches to treatment and rehabilitation, and respond to the considerable harm associated with injecting drug use (Interdepartmental Working Group on Substance Abuse, 1998).

Enforcement practices of the courts and the police with respect to marijuana have changed markedly in Canada since the 1970s (Riley, 1998).

Police now primarily (but by no means solely) target growers and distributors instead of consumers. In Canada, the police and the judiciary have created a de facto softening of penalties for possession, not the politicians. The police target the growers, but the expansion of the cannabis industry has continued during the past years (Bouchard, 2007; forthcoming).

Bill C-8 was a major revision of legislation in order to better fulfil its international obligations. Bill C-8 (The Controlled Drugs and Substances Act or CDSA) adopted on 20 June 1996, formed part of Canada’s National Drug Strategy. It was intended “to provide a framework for the control of import, production, export, distribution and use of mind-altering substances.” (Leduc & Lee, 1996).

The CDSA law replaced the Narcotic Control Act and parts III and IV of the Food and Drugs Act on May 14, 1997. It prohibits the importation, production, sale, provision and possession of a wide variety of controlled drugs and substances.

Simple possession of 30 g or less of cannabis (marihuana/marijuana) or 1 g or less of cannabis resin (hashish) is a summary conviction only offence and does not normally result in a criminal record.

Judges have considerable discretion in sentencing offenders under the CDSA. Sentences may take into account aggravating factors, e.g. selling drugs to children, or near schools or other public places where youth frequent (Health Canada, 2008).

The new developments concern the decriminalisation of the possession of small amounts of drugs for personal use.

New legislation will amend the focus of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (CDSA) on drugs in schedule I (opiates, cocaine and methamphetamine) and schedule II (cannabis). Under CDSA no mandatory prison terms are mentioned, but currently these will be introduced. The legislation will allow the Drug Treatment Court (DTC) to impose a penalty other than a mandatory sentence on an offender who has previous conviction for a serious drug offence (without other aggravating factors and presuming that the offender will finish the DTC programme) (www.hc-sc.gc.ca/ahc-asc/activit/strateg/drugs-drogues-eng.php).

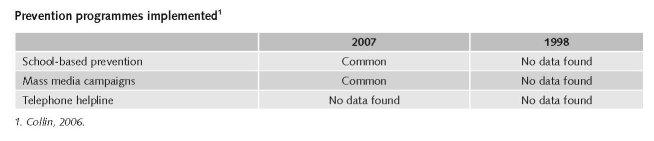

3.3 Demand reduction: Experimental/recreational drug use + problematic use/chronic-frequent use

No other data found on the rate of implementation of these preventive interventions.

Treatments available

Insufficient data available for determining the rate of implementation of available treatments.

Some treatment programmes are focussed on abstinence, other on reducing harm and stabilising the life of drug users. Only methadone is legally permitted in Canada for maintenance (long-term) treatment (Collin, 2006).

Both in-patient and out-patient treatment options exist.

Methadone maintenance is given when other treatment options have failed, and addicts must participate in mandatory counselling (Collin, 2006).

Drug Treatment Courts (DTCs) were initiated as a type of coercive treatment. The first one started in 1998 and is still reserved for criminals with a non-violence offence (Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse, 2007).

Some treatment programmes specialise in treating an addiction to a particular substance, e.g. solvent, heroin (Collin, 2006).

The opioid treatment system has expanded during recent years (especially the availability of MMT). Treatment utilization rates are still lower than in most Western European countries (Popova et al., 2006).

Priorities of demand reduction covered by policy papers or/and law

Some legislation allows for diversion of persons from the criminal justice system to treatment (alternative measures). Many provinces/territories also require those convicted of impaired driving offences to attend substance abuse education and/or treatment programmes.

Treating those with illicit drug dependencies by promoting collaboration among governments and supporting agencies to increase access to treatment services:

• Enhance treatment and support for First Nations and Inuit people;

• Provide treatment for young offenders with drug-related problems;

• Enable the RCMP to refer youth with such problems to treatment programmes;

• Support research on new treatment models;

• Support provinces and territories to improve treatments systems and address critical treatment needs of at-risk youth and • Other vulnerable populations.

• (Government of Canada, 2008).

Drug Treatment Courts (DTCs) were initiated as a type of coercive treatment. The first one started in 1998 and is still reserved for criminals with a non-violence offence. The second one started in Vancouver at the end of 2001. Four other DTCs may have been implemented now in Ottawa, Winnipeg, Regina and Edmonton.

These courts provide judicially-supervised treatment in lieu of incarcerating individuals who have a substance use problem that is related to their criminal activities, e.g. drug-related offences such as drug possession, use, or non-commercial trafficking and/or property offences committed to support their drug use such as theft or shoplifting (Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse, 2007).

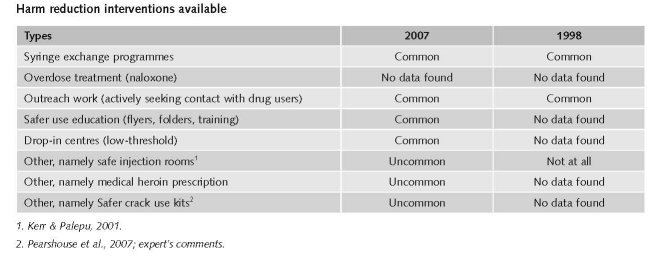

3.4 Harm reduction

3.4.1 HIV and mortality

Community-based outreach programmes and needle exchange programmes were among the first HR programmes introduced in Canada (Collin, 2006).

The first official Canadian NEP was opened in 1989. There are now more than 30 NEPs operating across Canada (Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse, 2007).

There is explicit supportive reference to HRI in national policy documents (IHRA, 2008).

Priorities of harm reduction covered by policy papers and/or law

The initial National Drug Strategy was launched in 1987, renewed in 1992 and named Canada’s Drug Strategy (CDS), the continued objective was to reduce the harmful consequences of drug use on individuals, families, and communities by addressing both the supply of and the demand for licit and illicit drugs (Collin, 2006).

Harm reduction was part of this strategy although criticisms pointed that this strategy heavily relied on enforcement-based legislation (Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network, 2006).

The national strategy was renewed in 2003 for a period of 5 years (2008).

Criticisms in 2003 were: 1) that demand and harm reduction actions were still not prioritised and remained ill-funded compared to supply reduction measures. On the contrary, a substantial proportion of the funds previously directed towards demand reduction were reallocated to supply reduction; and 2) that the strategy has been slow to respond to the growing body of scientific evidence indicating that many of the harms associated with drug use are due to enforcement based politics and practices. In 2004-2005 Drug Strategy funds were used to re-certify 550 existing DARE officers and to recruit and train 150 additional officers, despite of the fact that DARE has been proved ineffective in reducing drug use among students (e.g. Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network, 2006, p.8). The proposed prevention campaign, targeting at youth and their parents, is reminiscent of the US-style “Just Say No” campaign that did not work (Canadian Aids Society, 2007).

Harm reduction is not mentioned anymore in today’s National Anti-drug Strategy http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/ahc-asc/activit/strateg/drugs-drogues-eng.php.

Even though harm reduction was initially directed toward injection drug use, many jurisdictions have since adapted this approach to other illicit drugs, as well as to legal substances (Collin, 2006).

In June 2003 Health Canada approved an exemption from the application of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act to allow the launch of a supervised injection site pilot project “Insite”. Insite has been the subject of evaluation by a group of researchers, resulting in over 20 peer-reviewed publications in the past 4 years. Canada also endorsed experiments with medical heroin prescription (heroin-maintenance therapy). Finally, harm reduction interventions are also slowly introduced in prisons (http://www.cfenet.ubc.ca/cfepapers.php?id=47).

3.4.2 Crime, societal harm, environmental damage

The long term trend in the number of police-reported drug offences has remained stable over the past 15 years. It must be noted that trends in drug offences are directed influenced by levels of police enforcement (Tremblay, 1999).

Much of the increase in police-reported drug offences can be attributed to a rise in offences for the possession of cannabis. Between 1992 and 2002 684 (11%) murder incidents in Canada were reported to be drug related. Of these, 176 (26%) were gang related (Desjardins & Hotton, 2004).

References

Consulted experts

M. Bouchard, Assistant Professor, School of Criminology, Simon Fraser University, Vancouver.

N. Boyd, Professor and Associate Director of the School of Criminology, Simon Fraser University, Vancouver.

S. Brochu, Tenured Professor, School of Criminology, University of Montreal.

Documents

Bouchard M. A capture-recapture model to estimate the size of criminal populations and the risks of detection in a marijuana cultivation industry. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 2007, 23: 221-241.

Bouchard M, Dion CB. Growers and facilitators: Probing the role of entrepreneurs in the development of the cannabis cultivation industry. Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship, 2009, 22(1): 25-38.

CAS (Canadian Addiction Survey). A national survey of Canadians’ use of alcohol and other drugs. Prevalence of use and related harms. Detailed report. Ottawa, Health Canada, 2005.

CAS. A national survey of Canadians’ use of alcohol and other drugs. Focus on gender. Ottawa, Health Canada, 2008.

CAS. A national survey of Canadians’ use of alcohol and other drugs. Substance use by Canadian youth. Ottawa, Health Canada, 2007.

Canadian Aids Society. Canada’s new national anti-drug strategy: The Canadian AIDS, 2007.

Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse, FAQs. Drug Treatment Courts. Ottawa, 2007. Available: www.ccsa.ca, last accessed 12 December 2008.

Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse, FAQs. Needle exchange programs (NEPs). Ottawa, 2007.

Available: www.ccsa.ca, last accessed 12 December 2008.

Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse, FAQs. Crack Cocaine. Ottawa, 2006. Available: www.ccsa.ca, last accessed 12 December 2008.

Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network. Injection drug use and HIV/AIDS in Canada: The facts. Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network, 2005. Available: www.aidslaw.ca, last accessed 12 December 2008.

Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network. Canada’s 2003 renewed drug strategy – an evidence-based review. HIV/AIDS Policy & Law Review, 2006, 11 (2/3). Available: www.aidslaw.ca, last accessed 12 December 2008.

Casavant L, Collin C. Illegal drug use and crime: a complex relationship. Ottawa, Library of Parliament, 2001.

CFDP (Canadian Foundation for Drug Policy). HIV/AIDS and injecting drug use: A national action plan. (Report of the National Task Force on HIV, AIDS and Injection Drug Use. 2001.

CIA - The World Factbook: Canada. Available: www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/ge-os/ca.html, last accessed 20 December 2008.

Collin C. Substance abuse issues and public policy in Canada: I. Canada’s Federal Drug Strategy. Parliamentary Information and Research Service, 2006.

Correctional Service Canada. Speakers Binder, Section 7. Available: www.csc-scc.gc.ca, last accessed 12 December 2008.

Desjardins N, Hotton T. Trends in drug offences and the role of alcohol and drugs in crime. Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics (Juristat) 2004, 24(1).

Dauvergne M. Crime statistics in Canada 2007. Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics (Juristat) 2008, 28(7).

EPI Update. HIV/AIDS Epi Update. Ottawa, Health Canada, Centre for Infectious Disease Prevention and Control, 2003.

Fischer B, Rehm J, Blitz-Miller T. Injection drug use and preventive measures: a comparison of Canadian and western European jurisdictions over time. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 2000, 162: 1709-1713.

Fischer B, Rehm J, Patra J, Firestone Cruz M. Changes in illicit opioid use across Canada. CMAJ, 2006, 175(11): 1385-1387.

Government of Canada. National Anti-Drug Strategy. Ottawa: Government of Canada, 2008, Backgrounder.

Health Canada. Canadian Addiction Survey (CAS). Focus on gender. Ottawa, 2008.

Health Canada. Straight facts about drugs and drug use. What are Canada’s drug laws? Controlled Drugs and Substance Act. 2008. Available: www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hl-vs/pubs, last accessed 12 December 2008.

Interdepartmental Working Group on Substance Abuse. Canada’s Drug Strategy. Ottawa, Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada, 1998.

Kerr T, Palepu A. Safe injection facilities in Canada: Is it time? JAMC, 2001, 165(4), 436-437.

Leduc D, Lee J. Illegal drugs and drug trafficking. Depository Services Program, Nov. 1996 (revised Feb 2003).

Mathers BM, Degenhardt L, Phillips B, Wiessing L, Hickman M, Strathdee SA, Wodak A, Panda S, Tyndan M, Toufik A, Mattick RP. Global epidemiology of injecting drug use and HIV among people who inject drugs: a systematic review. The Lancet, 2008, vol. 372, Sept 24 (Table 5).

OAS/CICAD. Canada. Evaluation of progress in Drug Control 2005-2006. OAS/CICAD, Multilateral Evaluation Mechanism (MEM/INF, 2006 Add. 8), 2007.

PHAC (Public Health Agency of Canada). Infectious diseases: HIV-AIDS. Key populations. 2008.

Pearshouse R, Elliott R, Robinson C. Distribution of Safer Crack Use Kits in Canada: Legal issues. Poster presented at the 16th International Conference on the Reduction of Drug Related Harm, Warsaw, 2007.

Popova S, Rehm J, Fischer B. An overview of illegal opioid use and health services utilization in Canada. Public Health, 2006, 120(4): 320-328.

RCMP (Royal Canadian Mounted Police). Drug situation in Canada 2003. Ottawa, RCMP, 2004.

RCMP. Drug Situation Report 2006. Appendix A. Ottawa, RCMP, 2007.

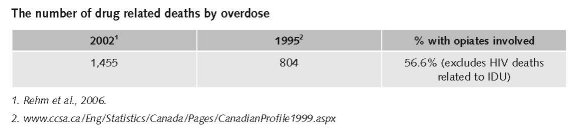

Rehm J, Baliunas D, Brochu S, Fischer B, Gnam W, Patra J, Popova S, Sarnocinska-Hart A, Taylor B. The costs of substance abuse in Canada 2002. Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse, 2006.

Riley D. Drugs and drug policy in Canada: A brief review & commentary. Prepared for the Canadian Foundation for Drug Policy, 1998 (updated in 2001).

Single et al.. The costs of substance abuse in Canada. Ottawa, Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse, 1996.

Society looks beneath the surface. Available: www.cdnaids.ca/web/pressreleases.nsf, last accessed 12 December 2008.

Thomas G. Harm reduction policies and programs for persons involved in the criminal justice system. Ottawa, Canadian Centre on Substance abuse, 2005.

Tremblay S. Illicit drugs and crime in Canada. Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics (Juristat), 1999, 19(1).

UNAIDS/WHO. AIDS epidemic update. Regional Summary 07. Geneva, 2008.

UNDCP (United Nations International Drug Control Programme). Global Illicit Drug Trends 1999. New York, UNDCP, 1999.

UNDCP Studies on Drugs and Crime. Global Illicit Drug Trends 2000. Statistics. Vienna, UNDCP, 2001.

UNODC. World Drug Report 2008. Statistical Annex. Vienna, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2008.

www.ccsa.ca/Eng/Statistics/Canada/Pages/CanadianProfile1999.aspx, last accessed 12 December 2008.

www.hc-sc.gc.ca/ahc-asc/activit/strateg/drugs-drogues-eng.php, last accessed 12 December 2008.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|