PRELIMINARY

| Reports - Wickersham Commission Report |

Drug Abuse

PRELIMINARY

1 SCOPE OF THE REPORT

In the First Deficiency Act, fiscal year 1929, under which this Commission was appointed, its purpose was stated as follows; "A thorough inquiry into the problem of the enforcement of prohibition under the provisions of the Eighteenth Amendment of the Constitution and laws enacted in pursuance thereof, together with the enforcement of other laws." This statement of purpose is repeated in the Second Deficiency Act, fiscal year 1930, in these words : "For continuing the inquiry into the problem of the enforcement of the prohibition laws of the United States, together with enforcement of other laws, pursuant to the provisions therefor contained in the First Deficiency Act, fiscal year 1929." Such being the purpose, the method of inquiry was stated by the President in his address at the beginning of the work of the Commission: "It is my hope that the Commission shall secure an accurate determination of fact and cause, following them with constructive, courageous conclusions." In such a connection it is impossible to divorce the problem of enforcement from that of enforceability. Hence in order to conduct a thorough inquiry, so as to lead to constructive conclusions, we have felt bound to go into the whole subject of enforcement of the Eighteenth Amendment and the National Prohibition Act; the present condition as to observance and enforcement of that Act and its causes; whether and how far the amendment in its present form is enforceable; whether it should be retained, or repealed, or revised, and a constructive program of improvement.

2 MATERIALS USED

As the basis of our conclusions, we have used the following materials:

1. Reports of investigators. Under the direction of Mr. Henry S. Dennison, Mr. Albert E. Sawyer, assisted by a number of investigators and statisticians, made a survey and report covering the organization, personnel and methods of federal prohibition enforcement, the personnel management of the bureau of prohibition prior to the transfer to the Department of Justice, and the operation of the permit system. Mr. James J. Forrester made investigations and reports on the effects of prohibition in industry and on the condition of wage earners and their families. Mr. A. W. W. Woodcock, now Director of Prohibition in the Department of Justice, before his appointment to that position submitted a number of reports based on study of the materials before us and of materials gathered by personal investigation in different localities. Also an investigator was employed to go over the law reports and the statistical and other information published by the several states bearing on the extent of state co-operation and state enforcement.

2. Statements of Officials. Statements were made before the commission by the Secretary of the Treasury, the Attorney General, the Assistant Attorney General in charge of prohibition cases, a former Assistant Attorney-General in charge of prohibition cases, the Assistant Secretary of the Treasury, the present Director of Prohibition, the Commissioner of Prohibition (before the Prohibition Reorganization Act of 1930) and Chief Law Officer of the Prohibition Bureau (before that reorganization), the Assistant Secretary of Labor, the Assistant Commissioner General of Immigration, and the Supervising Examiner of the Civil Service Commission.

3. Surveys. Under the direction of the Commissioner of Prohibition (prior to the transfer to the Department of Justice) surveys were made of the conditions as to observance and enforcement of the National Prohibition Act in substantially all of the states. These surveys were put at our disposal.

4. Examination of witnesses before the committee on prohibition or the commission. The committee on prohibition examined witnesses, often obtaining additional written statements. Among those heard were prohibition administrators and former prohibition administrators in important centers, United States attorneys and former United States attorneys having experience in cases under the National Prohibition Act, investigators for district attorneys, high police officials, economists and statisticians, physicians and heads of hospitals, educators, social workers, employers, labor leaders, leaders in civic organizations interested in enforcement of law, and persons specially interested in or prominent in connection with each side of the controversy as to prohibition. The Commission had no power to subpoena or swear witnesses, but no one requested by the Commission so to do failed to make an oral or written statement.

5. Letters in answer to questions or questionnaires. Letters were received from the governors of states, from judges, state and federal, throughout the country, from United States attorneys and state prosecuting officers, from chiefs of police, from the heads of colleges and high schools and persons prominent in education (procured with the assistance of officials of the National Education Association), from charity organizations and social workers, and from large employers of labor.

6. Memoranda from bureaus, federal and state. Memoranda, chiefly as to statistics, bearing on disputed questions of fact, were furnished freely by state and federal bureaus.

7. Reports of Congressional hearings. The reports of the hearings before the Judiciary Committee of the Senate in 1926 and of those before the Judiciary Committee of the House in 1930, were before us and were carefully collated with our other material.

8. Reports and statistics from foreign countries. Through the Department of State we were able to procure reports made specially by persons in the diplomatic and consular service of the United States, as well as official reports, printed documents, and statistics, bearing on systems of manufacture and distribution of liquor and the working of systems of liquor control in foreign lands.

9. Statements and suggestions 'volunteered. Manuscript statements, plans, proposals, and suggestions have been sent to us by volunteers from every quarter and have received due consideration.

10. Printed books, papers, and pamphlets. The voluminous literature on every aspect of prohibition and liquor control has been gone over carefully and collated with the other material before us.

Members of the Commission have also interviewed well informed persons in substantially every part of the country and have availed themselves of their personal observation and experience.

Our conclusions are derived from a critical study of these materials.

3 THE PROBLEM OF LIQUOR CONTROL

Laws against drunkenness are to be found very generally in antiquity. But the economic organization of the ancient world did not bring about the conditions of production and distribution with which attempts to control the use of alcohol must now wrestle. In the modern world, commercialized production and distribution especially of distilled spirits, called for legislative action early in the history of most of the modern nations. In England, what may fairly be regarded as restrictive, as distinguished from primarily economic lesgislation, begins in the fourteenth century. In the eighteenth century, following repeal of earlier restrictive statutes, the general use of distilled liquors called for legislation, and from that time there is a continuous history of legislative control in Great Britain. In Germany, sale of distilled liquor began to be regulated at the end of the fifteenth century. In France, regulation as distinguished from taxing legislation begins in 1818. In America, the history of liquor control begins with colonial legislation as to sale to Indians and closing hours, followed by a resolution of the Continental Congress in 1777 against distilled liquor. Over one hundred and fifty years of experimenting with systems of restriction, - through taxation and excise, closing hours, prohibition of selling to certain types of person, high license, local option, state dispensaries, state prohibition, and finally national prohibition, have not disposed of the subject. It remains one of acrimonious debate, with the most zealous adherents of the latest solution compelled to admit grave difficulties and serious resulting abuses. The necessity of liquor control is universally admitted in civilized countries. But this necessity of control gives rise to a problem of how to bring it about which has vexed society for centuries and now gives concern in all lands and very likely will persist whatever regimes of regulation are set up.

To some extent the problem of liquor control is interwoven with the whole problem of the relation of an ordered society to the individual life. Much of the difficulty encountered by every system of control and much of the difficulty encountered in enforcement of the National Prohibition Act is involved in all social control through law. The National Prohibition Act has brought into sharp relief features of this wider problem which has not attracted general attention. But there are special and intrinsic difficulties in liquor control and particularly in a regime of absolute prohibition. Settled habits and social customs do not yield readily to legislative fiats. Lawmaking which seeks to overturn such habits and customs, even indirectly by cutting off the sources of satisfying them, necessarily approaches the limits of effective legal action. The long history of legislative liquor control is one of struggle against this inherent difficulty. It could not be expected that legislation seeking to make a whole people at one stroke into enforced total abstainers would escape it.

4 HISTORY OF LIQUOR CONTROL BEFORE THE EIGHTEENTH AMENDMENT

A study of the problem of prohibition enforcement requires a brief review of the history of the abuses which led to the adoption of the Eighteenth Amendment and of the evils which the amendment was designed to remove.

The evils resulting from the production, sale and use of intoxicating liquors have troubled communities and legislatures increasingly in modern times. Legislation on the subject was enacted in the American Colonies, primarily for the purpose of preventing the sale of liquor to Indians and also for the purpose of preventing as well as for punishing drunkenness. The Continental Congress, on February 27, 1777, adopted a resolution:

"that it be recommended to the several legislatures of the United States immediately to pass laws the most effectual for putting an immediate stop to the pernicious practice of distilling, grain, by which the most extensive evils are likely to be derived, if not quickly prevented."

The Congress of the United States, at its first session under the Constitution, passed a law, approved July 4, 1789, placing a tax on the importation of ale, beer, porter, cider, malt, molasses, spirits, and wines. The purposes of the Congress in adopting this law were revenue, protection, and incidentally encouragement of temperance. By an act approved March 3, 1791, import duties on liquors were raised and an excise tax was placed on all spirits distilled within the United States, but not on malt liquors. Opposition to this tax was manifested in many places and produced what is known in history as the Whisky Insurrection in Western Pennsylvania, which was not placated by an act of May, 1792 (raising the duty on imports and reducing the excise tax), and which was suppressed only by the use of federal troops. In the period thereafter to 1861 various acts were enacted by Congress from time to time imposing excise or ad valorem taxes upon various forms of intoxicating liquors. After the outbreak of the Civil War on July 1, 1862, a comprehensive act was adopted imposing a tax on the sale of liquor and providing for the issuance of federal licenses. From 1862 until the World War every brewery and distillery in the United States was operated under a federal license, subject to policing by the federal government and required to maintain and file elaborate records. Subject to these provisions, the liquor traffic was conducted with the sanction of the federal government, which profited from the business to the extent of depending upon it for over one-fourth of the national revenue over a long series of years.

Without entering into a detailed review of the long history of the efforts to grapple with the liquor traffic, it may be observed that failure to secure compliance with state regulatory laws and the influence exercised by organized liquor interests in political affairs greatly stimulated the movement towards national prohibition. As early as 1885 amendments were proposed in Congress prohibiting the manufacture and dealing in intoxicating liquor. In the reports of senate committees in both the 49th Congress (1886) and the 50th Congress (1888) reference was made to a growing body of opinion that the evil wrought by the use of alcohol as a beverage and its effect upon the life, health and morals of the American people could only be removed by national legislation enforced by the national will in cooperation with the efforts of the states.

The police powers of the states, upon which state prohibition laws had been held valid, were declared by the Supreme Court of the United States ineffective to prevent importation of liquor from a wet state into a dry state and impotent to stay the sale and delivery within a prohibition state of liquor in the original package in which shipped from another state. As a result Congress, by the Webb-Kenyon Act of 1913, prohibited the shipment of liquor from one state into another to be used in violation of the laws of the latter, and thus enabled the dry states to make their prohibition laws effective against liquor shipped in interstate commerce.

When the United States entered the World War in April, 1917, it was universally recognized that one of the most essential steps in winning the war was to suspend the liquor traffic. Accordingly, in May, 1917, Congress prohibited the sale of liquor to soldiers. In September, 1917, the Food Control Bill was passed containing a provision prohibiting the manufacture and importation of distilled liquor for beverage purposes and authorizing the President at his discretion to reduce the alcoholic content of beer and wine and to limit, prohibit and reduce the manufacture of beer and wine. In 1918, the Agricultural Bill, which became a law on November 21st of that year, provided for the prohibition of the manufacture of beer and wine after May 1, 1919, and prohibition of the sale of all liquors after June 30, 1919. The period of war prohibition was continued until the conclusion of the war, and, thereafter, until after the termination of demobilization.

On April 4, 1917, a joint resolution was introduced in the Senate, proposing an amendment to the Constitution prohibiting the manufacture, the sale or transportation of intoxicating liquors within, the importation thereof into, and the exportation thereof from the United States and all territory subject to the jurisdiction thereof for beverage purposes. In the course of the debate over this resolution, reference was made to the fact that twenty-six states had enacted state prohibition laws, that more than 60 per cent of our people and 80 per cent of the territory of the United States at that time were living under prohibition.

Two features of the history of liquor control in the United States are of special importance for our present purpose, namely, the effect of industrial organization and consequent methods of manufacture and sale upon production and consumption of liquor and the effect of this and of organizations of producers upon politics. Much of the failure of the systems of liquor control devised in nineteenth-century America was due to their presupposing an economic situation which was ceasing to exist. For example, the high license system sought to insure responsible local sellers of good character and standing who might reasonably be expected to conform to the regulations imposed by local opinion and expressed in local laws. But the days of the old independent local tavern keeper were gone. The business of brewing and that of distilling came to be organized. The local brewer and local distiller supplying a limited local trade gave way to great corporations, organized on modern lines, each prepared to do a huge business and seeking to expand by finding new markets and increasing their business in old markets. Competition between these corporations was keen. Methods of production and distribution were improved continually. Sales organization was developed. More and more the local seller ceased to be independent and became a mere creature of some producer. Thus there was every pressure upon the seller to sell as much as possible and to as many as possible. Legislation preventing such corporations from holdings licenses was not hard to evade and ran counter to the settled economic current. Commercialized production and distribution, under the economic order of the twentieth century, became a great evil.

No less an evil grew up through the political activities and influence of organizations of producers, working through their local dependents. The corrupting influence upon legislation and upon administration and police in our large cities was conspicuous and growing. The steady progress of state prohibition and local option was largely coincident with the growing power of these organizations and due to public resentment thereat.

Probably the institution which most strongly aroused public sentiment against the liquor traffic was the licensed saloon. The number of saloons was increasing in many states. In general, they were either owned or controlled by brewers or wholesale liquor dealers. The saloon keepers were under constant pressure to increase the sale of liquors. It was a business necessity for a saloon &keeper to stimulate the sale of all the kinds of liquor he dealt in.

The saloons were generally centers of political activity, and a large number of saloon keepers were local political leaders. Organized liquor interests contributed to the campaign expenses of candidates for national, state and local offices. They were extensive advertisers in the newspapers. Laws and ordinances regulatory of saloons were constantly and notoriously violated in many localities. The corruption of the police by the liquor interests was widespread. Commercialized vice and gambling went hand in hand with the saloons. When proceedings were taken to forfeit saloon licenses because of violation of the law, it was a common practice for the brewers to procure surety company bonds and provide counsel to resist forfeiture. The liquor organizations raised large funds to defeat the nomination or election of legislators who opposed their interests. The liquor vote was the largest unified, deliverable vote. The result of advertising by the brewers was a substantial increase in the consumption of beer, which was followed by some increase in the consumption of whisky, as shown by the statistics published by the Bureau of the Census.

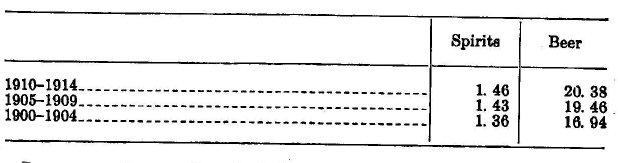

In three five-year periods prior to 1914, the per capita consumption in gallons of distilled spirits and beer increased as follows:

In a general way the alcoholic content of spirits is from six to seven times that of beer.

In many cities, saloons occupied at least two and sometimes all four corners at the intersection of important streets. They also held strategic positions near entrances to large factories and industrial plants. They furnished open invitations to wageworkers, as they deft their places of employment, to enter and spend their money. Many left the saloons for their homes in a state of intoxication and with only the remnants of their wages in their pockets.

The United States Brewers Association, which was one of the dominant factors in the liquor situation from the time of its organization on November 12, 1862, in the annual address of its president in 1914 quotes the "American Grocer," the liquor dealers' organ, to the effect that despite the adoption of prohibition in some states and local option in others the per capita consumption of alcoholic drinks had increased nearly three gallons over a ten-year period. The Year Book of the association for that year contains arguments against national prohibition based upon the asserted fact that this would destroy a capital investment in the liquor industry in the United States which had reached the "huge sum of $1,294,583426." The United States Ceri6ls Bureau reports fixed the amount of capital so invested at that time at $915,715,000.

The evils of the liquor system most responsible for the formation of public opinion leading to the adoption of the Eighteenfh Amendment, were the saloon and the corrupt influence of licquor dealers in politics, the latter being linked closely with the former.It is significant that almost all of the bodies at the present time seeking the repeal of the Eighteenth Amendment concede that under no circumstances should the licensed saloon be restored. Admittedly, the great achievement of the Eighteenth Amendment has been the abolition of the saloon.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|