I. NATIONAL PROHIBITION

| Reports - Wickersham Commission Report |

Drug Abuse

I. National Prohibition

1 THE EIGHTEENTH AMENDMENT AND THE NATIONAL PROHIBITION ACT

On December 18, 1917, the joint resolution was adopted by both houses with the required constitutional majority and was transmitted to the states for their consideration. On January 29, 1919, the Secretary of State, by proclamation, announced that on January 16th thirty-six states had ratified the amendment and therefore it had become a part of the Constitution. It was subsequently ratified by ten additional states. It became effective on January 16, 1920, as the Eiahteenth Amendment to the Constitution, the pertinent sections of which are as follows:

" Sec. 1. After one year from the ratification of this article the manufacture, sale or transportation of intoxicating liquors within, the importation thereof into, or the exportation thereof from the United States and all territory subject to the jurisdiction thereof for beverage, purposes is hereby prohibited.

" Sec. 2. The Congress and the several states shall have concurrent power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation"

The absolute prohibitions of the Amendment extend only to the manufacture, sale, transportation, importation, or exportation of intoxicating liquors for beverage purposes. The Amendment does not prohibit the manufacture, sale, transportation, importation, or exportation of alcoholic liquors which are not intoxicating, or of intoxicating liquors for other than beverage purposes. It does not define intoxicating liquors or directly prohibit the purchase, possession by the purchaser, or use of any liquor, whether intoxicating or otherwise. The power to deal with these questions is vested in Congress under the provisions of Section 2 of the Amendment, or left to the several states.

In pursuance of this authority, in October, 1919 Congress passed the National Prohibition Act. In the title to this act three distinct purposes are stated: (1) to "prohibit intoxicating beverages," (2) to regulate the manufacture, production, use and sale of high proof spirits for other than beverage purposes," and (3) to "insure an ample supply of alcohol and promote its use in scientific research and in the development of fuel, dye and other lawful industries."

The law is divided into three titles. Title I deals with war-time prohibition and is not material to this inquiry; Title II with the prohibition of intoxicating beverages; and Title III with industrial alcohol.

By Section 3 of Title II it is declared that " all of the provisions of this Act shall be liberally construed to the end that the use of intoxicating liquor as a beverage may be prevented." This language has been criticized as extending the purpose of the Act beyond that of the Amendment of the Constitution. The criticism seems rather technical. The Amendment did not expressly prohibit the use of intoxicating liquors as a beverage, but without this use the things prohibited would not exist. On the other hand, if the direct prohibitions of the Amendment were effective there could be no use for beverage purposes except as to the limited simply on hand when the Amendment became operative. The direct and expressed purpose was to prohibit the sources and processes of supply; the ultimate purpose and, if successful, the inevitable effect was to prohibit and prevent the use of such liquor as a beverage.

It has been observed that the Eighteenth Amendment did not define intoxicating liquors which were prohibited for beverage purposes. In the absence of any definition this would, of course, mean liquors which were in fact intoxicating, a matter practically impossible of accurate determination, since" it -would depend upon the amount and conditions of consumption, the physiology of the consumer, and other factors which vary in each case. The definition of this term to be effective must necessarily fix a somewhat arbitrary standard. It was left to the legislative discretion of Congress.

In Title II Section 2, of the National Prohibition Act, it was declared that the phrase "intoxicating liquors should be construed to include alcohol, brandy, whisky, rum, gin, beer, ale, porter, and wine, and in addition thereto any spirituous, vinous, malt or fermented liquor, liquids and compounds. whether medicated, proprietary, patented or not, and by -whatever name called, "containing one-half of one per centum or more of alcohol by volume which are fit for use for beverage purposes."

The validity of the provision and the definition of alcoholic liquor therein were challenged in the courts and were sustained by the Supreme Court of the United States as being within the powers conferred upon Congress by the Amendment."

To this general limitation of less than one-half of one per cent alcoholic content by volume there is in the Act one exception as applied to manufacture.

This appears in Section 29 of Title II, which, after prescribing penalties for certain violations of the Act, including illegal manufacture and sale, declares that "the penalties provided in this Act against the manufacture of liquor without permit shall not apply to a person for manufacturing non-intoxicating cider and fruit juices exclusively for use in his home, but such cider or fruit juices shall not be sold or delivered except to persons having permits to manufacture vinegar."

The amendment does not directly prohibit the purchase or possession of alcoholic liquor for beverage purposes. Nor does the National Prohibition Act prohibit the purchase for such purpose, although prohibitions against purchase are contained in many state laws. "Section 25, Title II of the Act does expressly declare it to be unlawful to have or possess any liquor or property designed for the manufacture of liquor intended for use in violation of the Act, or which has been so used and makes such property subject to confiscation. Section 33 provides that after February 1, 1920 the possession of liquor not legally permitted shall be prima facie evidence that such liquor is kept for disposition in violation of the law. This latter section excepts from its operation liquor in one's private dwelling, while the same is occupied as his dwelling only provided such liquors are for use only for the personal consumption of the owner thereof and of his family residing therein and of his bona fide guests when entertained by him therein, placing the burden of proof upon the possessor to prove that such liquor was lawfully acquired, possessed and used.

The penalties prescribed for violations of the Act vary as to different offenses. For violation of an injunction against maintaining a place of manufacture or sale, declared to be a nuisance, the penalty is fixed at a fine of not less than $500 nor more than $1,000 or imprisonment of not less than thirty days nor more than twelve months, or both. For illegal manufacture or sale, the penalty prescribed for the first offense is a fine of not more than- $1,00 or imprisonment not exceeding six months; and for a second or subsequent offense a fine of not less than $200 nor more than $2,000 and imprisonment of not less than one month nor more than five years. By the Increased Penalties Act approved March 2, 1929, it was provided that wherever any penalty was prescribed for the illegal manufacture, sale, transportation, importation, or exportation of intoxicating liquor as defined in the Act, the penalty imposed for each such offense should be a fine not to exceed $10,000 or imprisonment not to exceed five years, or both, but that this Act should not operate to repeal any minimum penalties then prescribed by law. It is further declared by this Act that it was the intent of Congress that the courts in passing sentence under this Act should discriminate between " casual and slight " violations, and habitual sales of intoxicating liquor or attempts to commercialize violations of the law.

In addition to these basic provisions, which are in a sense supplemental to the Amendment, the Act contained elaborate provisions for the enforcement of the prohibition against the manufacture, sale, transportation, importation, exportation, or possession of alcoholic liquors as defined therein for beverage purposes; the regulation of the manufacture, sale, transportation, and use of alcoholic liquors for non-beverage purposes and of alcohol for industrial purposes, with numerous administrative provisions intended to make the law effective.

It is not deemed appropriate to encumber this report with further analysis of the Act. Other pertinent provisions will be stated to such extent as may seem necessary in connection with the discussion of the problem of enforcement as applied to the various subjects which come within the scope of the law.

2 HISTORY OF PROHIBITION ENFORCEMENT BEFORE THE BUREAU OF PROHIBITION ACT 1927

(a) Original Organization

The Amendment and the National Prohibition Act inaugurated one of the most extensive and sweeping efforts to change the social habits of an entire nation recorded in history. It 'Would naturally have been assumed that the enforcement of such a novel and sweeping reform in a democracy would have been undertaken cautiously, with a carefully selected and specially trained force adequately organized and compensated, accompanied by efforts to arouse to its support public sympathy and aid. No opportunity for such a course was allowed.

As already noted, it was necessary to leave the definition of intoxicating liquor to the legislature, and also necessary for the legislature to fix a somewhat arbitrary standard. Considerable public sentiment, was however, antagonized by the legislative fixing of the permissible content of alcohol at a percentage substantially below the possibility of intoxication. This gave offense to a number of people who perhaps did not give adequate consideration to the administrative difficulties which might be involved by permitting a larger alcoholic content. Instant compliance was necessarily required from the date the amendment became effective. Scant opportunity was allowed for the organization of a force to carry out the Congressional mandates. There was no time or opportunity for careful selection of personnel. The officials charged with the execution of the law realized grave difficulties in the task thus imposed upon them.

The Commissioner of Internal Revenue, in his Annual Report to the Secretary of the Treasury for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1919 made while the National Prohibition Act was pending in Congress, referred to the fact that that bill placed the responsibility for the enforcement of its provisions upon the Bureau of Internal Revenue of the Treasury Department, which already was burdened with the fiscal and revenue problems of the government. "Not to enforce prohibition thoroughly and effectively," said the Commissioner, "4 would reflect upon our form of government, and would bring into disrepute the reputation of the American people as law abiding citizens. No law can be effectively enforced except with the assistance and cooperation of the law-abiding element. The Bureau will accordingly put into operation at once the necessary organization to cooperate with the states and the public in the rigid enforcement of the prohibition law, and appeals to every law-abiding citizen for support. This contemplated end requires the closest cooperation between the Federal officers and all other law-enforcing officers, state, county, and municipal."

"The Bureau naturally expects unreserved cooperation also from those moral agencies which are so vitally interested in the proper administration of this law. Such agencies include churches, civic organizations, educational societies, charitable and philanthropic societies. and other welfare bodies. The Bureau further expects cooperation and support from the law-abiding citizens of the United States who may have been opposed to the adoption of the Constitutional amendment and the law, which in pursuance of that amendment makes unlawful certain acts and privileges which were formerly not unlawful. Thus, it is the right of the Government officers charged with the enforcement of this law to expect the assistance and moral support of every citizen, in upholding the law, regardless of personal conviction.

If the cooperation thus referred to had been cordially given and the Bureau had been adequately and efficiently organized for the purpose of discharging the responsibilities laid upon it by the National Prohibition Act, it is probable that many problems of the character existing at the present time, would not have risen. As a matter of fact, very little cooperation was given by the agencies referred to and the organized bodies which had been instrumental in procuring the adoption of prohibition apparently abandoned all effort to convince the public of its advantages and placed all their reliance upon the power of the national government to enforce the law. The proponents of the law paid no heed to the admonition that "no law can be effectively enforced except with the assistance and cooperation of the law-abiding element." On the contrary, the passage of the act and its enforcement were urged with a spirit of intolerant zeal that awakened an equally intolerant opposition and the difficulties now being experienced in rallying public sentiment in support of the Eighteenth Amendment result largely from that spirit of intolerance.

On the passage of the law, the Bureau of Internal Revenue proceeded to organize departments under supervising Federal prohibition agents for the enforcement work and to create in each state an organization under a Federal prohibition director for the regulation and control of the nonbeverage traffic in alcohol by a system of permits. The appointment of prohibition directors and agents was not subject to the Civil Service laws. The salaries of prohibition agents were too low to be attractive. There has been much criticism of the character, intelligence and ability of many of the force originally appointed and many of their successors, and it is probably true that to their reputation for general unfitness may be ascribed in large measure the public disfavor into which prohibition fell. Allegations of corruption were freely made, and, in fact, a substantial number of prohibition agents and employees actually were indicted and convicted of various crimes. The facts are given more in detail by the Assistant Secretary of the Treasury in his testimony before the Senate Committee hereinafter referred to.

When the new national administration came in, in 1921, a committee was appointed, consisting of two members of the cabinet and an assistant secretary, who made a study of the subject, and recommended the transfer of certain activities from one department to the other where they appropriately belonged, including the transfer of the prohibition enforcement unit to the Department of Justice. That transfer, which also was recommended by this Commission in its preliminary report in November 1929, was authorized by Congress and carried out in this present year, 1930.

The organization set up under the Bureau of Internal Revenue was headed by a Commissioner of Prohibition. The original appointee, served from November 17. 1919, to June 11, 1921. His successor served until May 20, 1927, but the latter's authority was curtailed on November 1. 19257 by the appointment of a Director of Prohibition with equal power, who also served until May 20, 1927. On that (late the offices were reconsolidated and a new Commissioner appointed who served until July 1, 1930.

The Bureau of Internal Revenue charged with the enforcement of prohibition as well as the Customs Bureau and the Coast Guard, were directly under the supervision of an Assistant Secretary of the Treasury. Five persons held that office between January 1920 and April 1925, and for eight months there was a vacancy in the office and no Assistant Secretary appears to have been especially charged with the supervision of the prohibition forces or the coordination of the three services.

During the period prior to July, 1921, the enforcement and permissive features of the law were administered separately, with supervising federal prohibition agents in charge of the former and state directors, who were permitted to choose their own personnel, in charge of the latter. During the short life of this system, an unusually large number of supervising agents saw service as heads of the twelve departments into which-the-country was divided. In July, 1921, the office of supervising federal prohibition agent was abolished, and enforcement placed under the state directors, 48 in number. The occupants of these positions were constantly changing, and 184 men were in and out of these 48 positions during the years 1921 to 1925, when the office was abolished. The enforcement agents, inspectors and attorneys, as -was authorized in section 38 of the National Prohibition Act, were appointed without regard to the Civil Service rules. A force so constituted presented a situation conducive to bribery and official indifference to enforcement. It is common knowledge that large amounts of liquor were imported into the country or manufactured and sold, despite the law, with the connivance of agents of the law.

April 1, 1925, General Lincoln C. Andrews, a retired army officer was appointed Assistant Secretary of the Treasury and ascended to the supervision of Customs, Coast Guard and Prohibition. He reorganized the whole prohibition enforcement machinery, using the federal judicial district as the geographical unit, and grouping those units into districts. making in all twenty-four prohibition districts in each of which was placed an administrator, who was given the authority and was to be held responsible for the law's enforcement.

General Andrews, in a letter dated March 31, 1926, which was put in evidence at the hearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee, stated that 875 employees had been separated from the service for cause, from the commencement of prohibition to February 1, 19267 and of that number 658 separations had been effected since June 11, 1921. During substantially the same period, January 16, 19207 to March 30, 19261 148 officers and employees, including enforcement agents, inspectors, attorneys, clerks, etc., except-narcotic officers, were convicted on charges of criminality, including drunkenness and disorderly conduct.

While the number of convictions had in the federal courts for violation of provisions of the act, increased from 17,962 in the fiscal year ending June 30, 1921, to 37,018 in the fiscal year ending June 30, 1926, there was growing dissatisfaction with the results of the ad' ministration of the law, and an increasing volume of complaints against the service. These led to the introduction in Congress of a large variety of bills proposing amendments to the Eighteenth Amendment or to the National Prohibition Act and finally to demands for an investigation into the workings of the law.

(b) Senatorial Investigation, 1926

In April, 1926, an inquiry was opened before a subcommittee of the Judiciary Committee of the United States Senate, charged with the duty of Investigating and making a report to the full Judiciary Committee on all of these proposals. The report of the hearings before that committee fills two volumes, aggregating about 1,650 pages. The hearings lasted from April 5 to 24, 1926. It appeared from the evidence adduced that, despite the prosecutions referred to, and seizures of a large amount of liquor, a very great deal of industrial alcohol was being diverted and sold illicitly for unlawful purposes. General Andrews testified that the sources of illicit liquor at that time were smuggling, the diversion of medicinal spirits, the diversion of industrial alcohol, (which was the principal source or the backbone of bootleg liquor that was then sold), and in the south and middle west moonshine liquor.

General Andrews further testified that his assignment as Assistant Secretary of the Treasury in April, 1925, was to take charge of customs coast guard, and the prohibition unit and try to bring about cooperation between the three-for the purpose of enforcement of the prohibition laws, it being naturally the function of Customs to stop smuggling on the land and of the Coast Guard to stop smuggling by the sea. He found only about 170 patrolmen in the customs service; a very insufficient-, number. He needed more patrolmen than he could possibly supply. His entire border patrol force was 170 customs men on both land borders, Canada and Mexico, and 110 prohibition enforcement agents, making 280 in all. With certain contemplated additions, be expected his total force to be something like fifteen or sixteen hundred to patrol the whole of the Canadian border from the Atlantic to the Pacific, and the whole of the Mexican border from the Gulf to the Pacific. He thought that would stop the smuggling of liquor, although it would not materially reduce the supply in the country, because, as he had stated, the greater source of supply was from diverted alcohol and medicinal spirits.

In March, 1927, General Andrews resigned and Mr. Seymour Lowman, the present incumbent of the office, was appointed Assistant Secretary of the Treasurer to succeed him, effective April 1, 1927.

3 PROHIBITION ENFORCEMENT SINCE 1927

(a) The Bureau of Prohibition Act, 1927

Following the hearing before the Senate Committee, Congress, by act of March 3, 1927, known as "the Bureau of Prohibition Act" (44 Stats. 1381) created in the Department of the Treasury two bureaus a Bureau of Customs and a Bureau of Prohibition each under a commissioner; authorized the Secretary of the Treasury to appoint in each bureau one assistant commissioner, two deputy commissioners, one chief clerk, and such other officers and employees as he might deem necessary, and provided that the appointments should be subject to the provisions of the Civil Service laws and the salaries be fixed in accordance with the classification act of 1923. The Commissioner of Prohibition, with the approval of the Secretary of the Treasury, was authorized to appoint in the Bureau of Prohibition such employees in the field service as he might deem necessary, but it was expressly enacted that all appointments of such employees were to be made subject to the provisions of the Civil Service laws, notwithstanding the provisions of Section 38 of the National Prohibition Act. The term of office of any person who was transferred under this section to the Bureau of Prohibition, and who was not appointed subject to the provision of the Civil Service laws, was made to expire on the expiration of six months from the effective date of the Act, i.e, April 1, 1927.

From the time of enacting this law until the end of the year 1929, the tedious task of replacing men declared ineligible under the terms was taking place.

In April, 1927, the members of the force of the Bureau of Prohibition, exclusive of clerks in the field offices and clerks and administrative officials in the Washington headquarters (already serving under Civil Service regulations were subjected to examination to determine their eligibility to continue in the service. As a result, 41% of those of the force who took the examinations received therein passing marks by virtue of which they continued to hold their positions and 59% failed.

(b) Changes in Personnel and in Organization

The original organization set up in the Bureau of Internal Revenue at the beginning of prohibition did not last long, and experimentation with organization during the first few years was carried to a point which undoubted1y must have caused a feeling of insecurity and uncertainty in the force and detracted from the heartiness and confidence necessary to the effective working of any organization. During the eighteen months from January, 1920 to July, 1921, several hundred incumbents held the positions of agents for varying periods of time. There were constant changes in the prohibition administrators. In all but six of the twenty-four prohibition districts, during the period April 1, 1925 to March 31, 1927, there were two or more administrators two in each of ten districts, three in each of five districts and five in each of three districts. After the passage of the act of March 3, 1927, and during the subsequent period until July 1, 19301 in the twenty-seven prohibition districts there were two Administrators in each of eleven districts, three in one district, four in each of four districts, and five in one district. Not only were all of these changes made in the principal officers of the districts, but the boundaries of the districts themselves were frequently changed. Three districts underwent four territorial reorganizations, eight of them three, and nine of them two. Only seven districts remained substantially as originally outlined.

Among the district administrators, during the period April 1, 1927, to July 1, 1930, there were ninety-one changes in the twenty-seven districts, and in some of the districts the average length of service was only six months. It is quite obvious that no organization could function efficiently and harmoniously in such a state of upheaval, with its leadership continually shifting and its plan of field organization subject to constant revision.

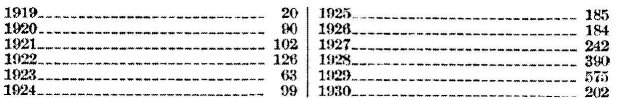

Of 2,278 persons in the service on April 30, 1930, the number appointed in each calendar year since the passage of the National Prohibition Act is shown as follows:

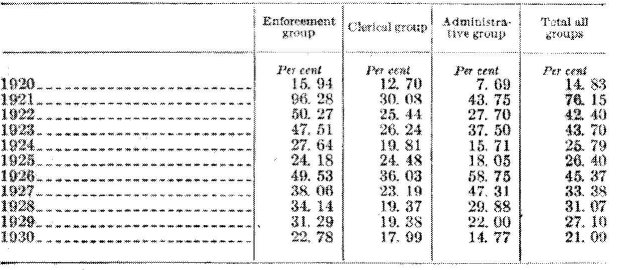

Of the 943 Prohibition agents in the service on July 1, 1920, the salaries of 839 ranged from $1,200 to $2,000 per per annum. Of the remainder, 89 were paid from $2,000 to $2,500; 12 from $2,000 to $3,000, and only three received more than $37000. At the present time the prohibition agents receive a salary of $2,300 upon entering the service. This is gradually increased to a maximum of $2,800 per annum. The annual turnover in personnel has been large. Eliminating any increase or decrease in the aggregate and considering only positions vacated and refilled, the figures furnished us show the following annual turnover in personnel, by groups, for the fiscal years 1920 to 1930, inclusive (less narcotic field force):

The turnover in the higher administrative posts averaged 29.37 per cent per annum during the period of eleven years, the peak being 58.75 per cent in 1926. The turnover in the enforcement branch during the years 1920 to 1930 averaged 39.78 Per cent. The effect of the application of the Civil Service laws marked a reduction but in 1930, the turnover was still too high, being 22.78 per cent.

One of the most unp1easant aspects of the problem of prohibition enforcement which relates directly to the matter of organization and personnel arises out of the charges of bribery and corruption. A general charge of this character against any organization is easily made but difficult of proof. It is obviously unjust to those in the organization who are not only honest but are diligent and patriotic in the discharge of their public duties. Yet to the extent that these conditions have existed or may now exist they constitute important factors in the problem of prohibition enforcement and are vital considerations as affecting the government generally.

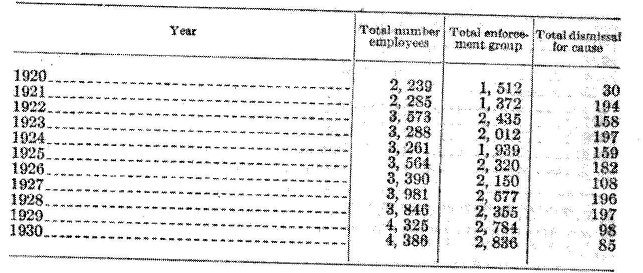

From statements furnished, it appears that from the beginning of national prohibition to June 30, 1930 there were 17,972 appointments to the prohibition service, 11,982 separations from the service without prejudice, 1.604 dismissals for cause. These figures apply only to the prohibition organization and do not include Customs, Coast Guard, and other agencies directly or indirectly concerned -with the enforcement of the prohibition laws. The grounds for these dismissals for cause include bribery, extortion, theft, violation of the National Prohibition Act, falsification of records, conspiracy, forgery, perjury and other causes which constitute a stigma upon the record of the employee. The total number of employees in the service at the end of each fiscal year, the number in the enforcement group, and the number of dismissals therefrom for cause each year are given as follows (less narcotic field force):

These figures do not, of course, represent the total delinquencies of the character named which actually occurred. They only show those which are actually discovered and admitted or proved to such an extent as to justify dismissal. What proportion of the total they really represent it is impossible to say. Bribery and similar offenses are from their nature extremely difficult of discovery and improvements in organization and methods of selecting under Civil Service should operate to reduce the number of offenses.

(c) Training of Prohibition Agents

Not until the year 1927, was any effort made to furnish even the key men in the prohibition enforcement organization with special training in the work they were expected to perform. In the fall of 1927, a plan for giving training periods, each of two weeks duration, to agents and prohibition employees, was inaugurated. This was followed by an extensive tour by the Washington officials in charge of personnel training through every district in the country. This was begun early in 1928 and was continued in January, 1929. In February, 1930, the Prohibition Bureau school of instruction established a correspondence course for instruction in the duties of the office, the elements of criminal investigation, constitutional law, etc.

Since the extension of the Civil Service laws over it, there has been continued improvement in organization and effort for enforcement, which is reflected in an attitude of greater confidence in the prohibition agents on the part of United States attorneys and judges.

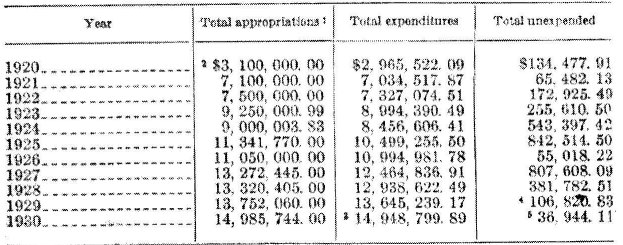

(d) Appropriations for Prohibition Enforcement

In the following statement of appropriations and expenditures the appropriations for the narcotic unit, which was operate as a part of the prohibition unit or bureau but with a separate personnel, are included, since in the data furnished the expenditures for the two services are combined. The appropriation for the narcotic unit averaged about 10 percent of the total.

1 These figures are taken from an annual publication of the Treasury Department "Combined Statement of Recelpts Disbursements, Balances et cetera of the United States" and represent balances of each appropriation adjusted as of June 30, 1930, except as noted.

2 includes $300,000.00 transferred to War Revenue for the enforcement of Title I of the National Prohibition Act.

3 This is the amount shown in Annual Report of Commisioner of Prohibition for 1930 as expended, and includes estimate of commitments outstanding and unpaid June 30, 1930.

4 and Estimated— subject to adjustment. Actual cash balances reported by Treasury Department, Division of Bookkeeping and Accounts, as of June 30, 1030 are: For the 1930 appropriation, $19,962.09; for the 1929 appropriation 38,820.83; 1929-30 deficiency appropriation $679,730.36.

These figures do not represent the total expenditures for prohibition enforcement. The expenditures for the Bureau of Customs, Coast Guard and other services directly or indirectly connected with prohibition enforcement many of which have been necessarily increased to a greater or less extent to meet the additional burdens imposed by the National Prohibition Act, do not appear in the foregoing figures.

(e) Cooperation with other Federal agencies

Cooperation of the Prohibition Bureau forces with the Customs and Coast Guard forces was imperfect, despite the fact that all three services were subject to the same department of government and directly under the control of an Assistant Secretary of the Treasury until July 1, 1930. Long experience had accustomed the officials and men of the Customs Service and the Coast Guard to work together. They did not readily cooperate with the prohibition forces. Despite the efforts of the Assistant Secretary, constructive cooperation between the three branches was not established.

The problem of preventing the smuggling of liquor into the United States at many points on our land and water borders-nearly nineteen thousand miles in extent-was added to the other duties of the prohibition force and the limited customs and coast guard forces.

The duties of the men in the Customs Service in preventing smuggling of liquor and other commodities over the international boundaries devolved upon what is called the border patrol of that service, the members of which receive a salary of $2,100 a year and are under the direction of the collector of customs. On the rivers such as the Niagara, the Detroit and the St. Clair, the customs service does the patroling in small picket boats.

The duties of the Coast Guard, apart from their life saving and maritime activities, include patroling the border waters of the country for general police purposes. Their number has been considerably increased since the enactment of the Prohibition Act, and on June W 1929, included 12,100 officers and men. The enlisted men in this service are paid $36 a month and furnished with uniforms, food and lodgings. The Coast Guard service had a serious organization problem of its own at the time that its forces were rapidly augmented in 1925 for the purpose of breaking up the rum row of vessels which lay off our coasts beyond the three mile limit, at which time some three thousand additional men were enlisted.

The Bureau of Immigration in the Department of Labor has a border patrol which was organized in 1925 primarily to prevent the illegal entry of aliens. The personnel of this patrol has been increased from about 400 in 1925 to approximately 1000 in 1930. This service works more closely with the Customs Bureau than it does with the prohibition forces, as the immigration inspectors are accustomed to work on the border with customs inspectors. This border patrol does, however, aid in the apprehension of aliens who are engaged in smuggling liquor.

Cooperation between all the forces above referred to would have been difficult at best. Each of the forces other than prohibition has duties to perform of a different nature than seizing liquor or apprehending smugglers of intoxicants. Effective cooperation is only possible where there is mutual respect and confidence. The older services had no such feelings for the newer.

These conditions explain the fact that save in a few places and under special conditions, there was no cordial, effective cooperation between these branches of the federal service. The attempts at better coordination have resulted in some progress, but much remains to be done. The Commissioner of Prohibition as late as June, 1929, stated that the then existing cooperation could be better. "It is a little spotty now, due to individual temperament. There is no difference of opinion or lack of complete harmony in the directing heads, but as you go down the service, the service rivalry crops out." One of the most important pressures necessary to the enforcement of the prohibition of liquor importation is the creation of a competent border patrol which shall unite in one efficient force the men of the four different services above mentioned. Difficult as is the task it does not seem to be beyond accomplishment although some legislative aid may be necessary to perfect such an organization.

(f) General Observations

The foregoing statements are sufficient to indicate the nature, extent, and resources of the Governmental machinery which has been set up for the purpose of prohibition enforcement and the more important aspects of its administration. Viewed solely from the standpoint of the enforcement machinery and administration, it is obvious that the organization has passed through many vicissitudes and has been subject to conditions many of which have been prejudicial to effective service. How far these conditions were inherent in the nature and subject-matter of the undertaking and in the conditions under which it was inaugurated and has been developed and how far they might have been or may now be avoided is difficult of determination and opinions differ thereon. The Eighteenth Amendment represents the first effort in our history to extent directly by Constitutional provision the police control of the federal government to the personal habits and conduct of the individual. It was an experiment, the extent and difficulty of which was probably not appreciated. The government was without organization for or experience in the enforcement of a law of this character. In creating an organization for this purpose, it was necessary to proceed by the process of trial and error. The effort was subject to those limitations which are inseparable from all human and especially governmental activities.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|