Four: Experiencing Other Persons

| Books - The Varieties of Psychedelic Experience |

Drug Abuse

Four: Experiencing Other Persons

The psychedelic drug subject's experiencing of other persons differs from his normal experiencing of others in a remarkable variety of ways. There are radical alterations of visual perception—of the way the other person is seen—and these are sometimes directly attributable to the sub-ject's emotional state and/or ideation. The subject may find in his awareness of his own psychical complexity a new appreciation and sometimes understanding of the complexity of another or others. 'The inadequacies of clichés and labels employed to simplify relationships often become apparent. Capacity for empathy seems greatly heightened in many cases. Customary methods of communication may be sup-planted by novel, characteristically "psychedelic" methods, including the telepathic if a great many subjects and observers may be trusted on this point. Out of these varied experiences may come significant reorien-tations in the area of interpersonal relationships.

Visual Perception of Other Persons. The visual experiencing of other - pezsons is for a majority of psychedelic subjects one of the most dra-, matie and memorable aspects of the session. How the subject sees another person depends mainly upon: 1)his sensory response to the person; 2)his emotional response to the person; 3) what he is thinking about the person; and 4)inferred unconscious determinants. Sensory and emotional response and ideation, along with unconscious materials, are interactive and apparently any one of the four may hold a tempo-rary ascendancy and determine to some extent the content of the first three. Doubtless this is also true outside the psychedelic drug context, but normally the interaction is not so clear to the person and the effects upon visual perception are much less striking.

Whether the subject sees another person in a positive or a negative way depends upon a great many factors. In general, if the subject is anxious or hostile with regard to another person or persons, he or they will be seen, if visual distortion occurs at all, in some negative way. If another person is liked or regarded as supportive by the subject, then he will be seen, should distortion occur, in a positive way. However, there are always exceptions; the same person may be viewed in a positive way at one time and in a negative way at another; and neither subject nor guide should respond automatically to visual distortions with any in vino veritas sort of interpretation.

The guide, when his performance is satisfactory, will only rarely be seen by a subject in a drastically distorted way. Especially, vvith the same qualification, the guide rarely will be seen distorted in a drastically negative way. The reason for this would seem to be that the guide is required as a kind of "home base," at once constant and yet able to accompany the subject on his psychedelic journey. Additionally, the subject presumably already has come to accept the guide as a trust-worthy, authoritative figure upon whose advice and good will he can rely; and the guide, by means of his in-session behavior, continues to recreate and reinforce this role.

Such distortions of the guide as occur thus will be mostly "in favor" of the guide. However, it is always possible that a subject, if sufficiently anxious, will distort the guide in some negative way—a phenomenon the guide may find useful in assessing his own performance and the state of the subject, but should not rely upon exclusively.

In a fairly common distortion the guide may be perceived by the subject as one or more of a variety of archetypal figures. For example, a female guide may be seen as a goddess, as a priestess, or as the personifi-cation of wisdom or truth or beauty. Descriptions of some of these "archetypal" perceptions have included seeing the guide's features as "glowing with a luminous pallor" and her gestures as being "cosmic, yet classical." The clothing has been seen by subjects to change and "flow," from the vestrnents of an Egyptian Isis figure to the robes of an Athena. As a final metamorphosis she has sometimes become some variation of a sort of future space deity, hovering between stars and clad in garments of star dust, glacial ice, and so on. All of these were positive perceptions for the subjects, who possibly enhanced their own sense of security by attributing godly or godlike status and powers to the guide.

However, in a negative variation of this type of distortion the guide was perceived as an Egyptian bas relief, a painting of Isis carved on some tomb wall. Perceptually depriving the guide of life, tridimension-ality, or freedom of movement, may be a weapon the subject uncon-sciously wields against the guide to "punish" her, make her less threat-ening, purchase self-aggrandizement at the guide's expense or otherwise assert a magical supremacy over her. In this case the subject, momen-tarily irritated, reduced the guide to bas relief status and then wrote: "So you are just an Egyptian tomb painting. VVhat a waster

Such perceptions as this one, along with similar reductions in which persons are seen as things or even may be denied form and substance, are usually products of anxiety or hostility but also may be rooted in egoism. In this latter case the subject may look out upon a world in which others exist not with-himself, but for-himself. Since this for-himself world is essentially a world of the other-as-object, the per-ceptual "thingification" of the other is not too surprising. The flattening out of the other—the perception of him as unilinear or as a painting—is often only the first step in an inanimatizing process that culminates in the subject's perception of the other as a thing deprived of all traces of the former identity and humanness.

To examine some more of these distortions the male guide may be seen as a Buddha or Buddha-like figure (positive distortion). The guide was so seen throughout most of a peyote session by a subject who at no time visualized him in a negative way. However, in a subsequent LSD session, this subject was more anxious and produced both negative and positive perceptions of the guide.

S-1, the subject just referred to, participated first in a peyote session that included two other subjects. These other subjects, both good friends of S, were nonetheless negatively distorted by him by means of the caricaturing process previously described. S writes that "Early in my session I noticed a tendency on my part to see people as caricatures of themselves. A minor physical peculiarity would transforrn itself into a major personality trait. The twitch of a facial muscle became the sinister leer of an evil mind. As the evening wore on this delusion became more pronounced and for a time it was unsettling to realize that I was seeing things as I did, not because that was how they were, but because my mind was shaping them in a peculiar manner—an observation that I think would also find application in my day to day life."

This subject, a businessman in his late twenties, insisted at one point in the session on going out for a walk. Since the dose had been light and the subject was well in control of himself, this was agreed to. Persons in the street then were also negatively distorted:

"Out on the street the cool evening air was chilly but exhilarating. The city, which had seemed from the window cold, grimy and slightly sinister, now was transformed into the wonderland I had envisioned when hearing fables as a child. The rich colors and textures of fantasy, more real than real, were pure enchantment. Walls of buildings had an added dimension to their surfaces. I felt I was walking in a waking dream. It was an all-consuming pleasure, just to see, touch, feel and smell. I had the urge to run and, giving way to the impulse, felt myself propelled along at triple speed, as in an old speeded-up movie.

"The occasional passer-by was also greatly altered in appearance and I saw him as a grotesque distortion of himself. The personality and intentions seemed to be boldly written on his features and reflected in his mannerisms. I found myself laughing openly at these people, a laughter that seemed to be three-quarters sarcasm and one-quarter de-light. I believe now that this was a magnification of a trait I ordinarily keep hidden, below the surface, even from myself. It was eerie, how I seemed to be able to divine the intentions of these strangers. I recall also seeing a car, built during the era when much chrome trim was in style. In the bright moonlight it became a blinding mass of glinting silver, overwhelming in its impact. I staggered back and looked with relief on the subtler tones of the city skyline.

"My friend--'s illusions took on a more frightening form. I can still see his expression as he looked down at a caterpillar on the ground and saw it seemingly grow in size to gigantic proportions and start to pursue him. He quickly looked away and never looked back on the creature again.

"Returning to the apartment I saw once more how the others were distorted, as if I were focusing on the dominant quality of each.. . . The guide seemed more and more, as the evening wore on, a kind of benign Buddha, malcing his own inner judgments of the people present."

Despite the negative visual distortions (generally of persons, but not of objects), S regarded his peyote experience as being overall an ex-tremely positive one. He limited himself mainly to sensory experiencing and found his awareness of color the most memorable aspect of the session. On his way home, "The city was bathed in the first pink rays of the morning sun and was truly breath-taking to behold. The soft greens of the trees and grass of Central Park were beyond belief. The buildings and streets had a warmth and charm hitherto reserved for memories of bygone days . . . That evening I was back in my old familiar world, but with an awareness of and appreciation for colors, hues and textures that I had never had before. This effect remains with me still (some four months later), but to a lessened degree. The scarcely remembered nausea was indeed a small price to pay for the remarkable night and the heightened awareness of the world around me that I still retain."

In his subsequent (LSD) session, S was determined to come to grips with some personal problems and to try to revise his thinking about various key persons in his life. The emotion generated by this effort, along with several unfortunate but unavoidable aspects of the setting, resulted in the subject's being more anxious than during his former session and also resulted in transient feelings of hostility toward the guide. Both the anxiety and hostility were at their strongest early in the session and yielded negative distortions of the guide who appeared to be "younger and more soft and plump . . . (The guide's) hair was hanging down in an unattractive way . . . (and the guide resembled) Little Boy Blue in the Gainsborough painting"—a decidedly negative perception for this subject. Later, S feeling less anxious and no longer hostile, the guide was seen by him as "very firm and massive, mature and authoritative looking"—a strongly positive perception.

This subject's negative visual perceiving and "caricaturing" of strangers encountered on the street is typical. When strangers are seen and visually distorted by a subject, the distortion is almost always nega-tive in one way or another. These distortions, as with the distortions of the guide, are usually products of anxiety and hostility. These last derive, in turn, from a variety of ideas and feelings that frequently have included the following:

Subjects almost always tend to feel ill at ease with persons who are not also taking the drug or who have not had some previous experience of it and so that they might "understand." The subject is uncertain of the extent to which he is able to function normally if need be and so sees those who have no interest in protecting his well-being as threats to him. As vvith primitive man, there is the sense that "the stranger is the enemy." The stranger may be seen (along the lines of Sartrean psychol-ogy) as that Other with whom one is always in essential conflict. Here, as theorized by a subject, "The stranger represents in its purest form other-personness. [And the subject then] . . . responds on essential and primordial levels. He can do this because he is unaffected by all of those additional factors that come into play when he is interacting with some-one whom he knows."

In general, when the predominant emotional response is anxiety, strangers will be seen as menacing; when hostility is the predominant response, a kind of patronizing view may be assumed, with the un-known others perceived as being absurdly grotesque, ridiculous, or pathetic. These responses are not invariable since, for example, a subject may cope with his anxiety by developing a solipsistic pattern in which other persons cannot harm him for the reason that they are his own mental constructs. 'Then he may visually perceive others from the same patronizing vantage point as one in whom anxiety is not the predomi-nant response.

One of the most common varieties of negative perception among subjects who take the "patronizing" view of other persons is the perceiv-ing of others as animals. S-2, a tvventy-seven-year-old male (LSD), first saw his wife, who he usually thought of as being quite attractive, as having "the head of a snouty hippopotamus on the body of a weasel." For a time he found this view rather funny, but later he found it disturb-ing and refused to look at her. S would not explore the significance of the distortion, but there was considerable conflict between the couple at the time.

This animalizing or theriomorphizing of others was a constant in S's experience. Standing on a balcony, he saw almost everyone on the street below in terms of some animal correlate. At one point he looked down at the street and began to giggle uncontrollably. He pointed to a fat and gaudily dressed lady who was walking a fat and gaudy Pekingese. He explained that he had visually "switched them" so that he saw "a big, fat Pekingese leading a little fat lady on a leash."

Similarly, S-3, a thirty-year-old physician (LSD), was taken by friends to a large department store where he wanted to experience the variety of "colors and movements." 'There, in the section selling ladies' dresses, he became convulsed with laughter and had to be taken to a less stimulating floor. S had seen the women around him as "a lot of broken down peacocks trailing bedraggled feathers"; as "clucking, complacent hens"; and, in the Tall Girls' division, as a bunch of "stringy, scrawny, beady-eyed ostriches." He was led out of the store proclaiming amidst guffaws that "Bloomingdale's is a turned-on barn-yard."

S-4, a writer in his late thirties, had predominantly hostile percep-tions of almost everyone but the guide, who was simultaneously seen by him as an attractive, friendly figure. At the end of his session he visited a restaurant with the guide and describes his visual impressions as follows:

"Seated in a restaurant where I have been many times before: ordi-narily, this is a dimly lighted place; but tonight, it seems to me, many additional lights are burning; or the same lights are burning, but much more brightly . • . My pupils, dilated, are drinking in light to an abnor-mal degree . . . Always in the past this has seemed to me a pleasant and cheerful place; but now, seeing everything much too clearly, I no longez find it so. The waiters, I remark, all seem to be pimps, thieves, cut-throats—in a film they surely would be pirates; the tablecloth appears to be worn, dirty and stained; and, across from us, I see great ugly red blotches on the face of a man who is drinking yellow wine and who frequently pauses to lick fat wet lips that are drooling. Another man, sitting at a nearby table, is partially paralyzed, so that bringing each forkful to his mouth seems an awkward, agonizing labor; and a small gray creature, reeking of death and resembling a gargoyle, scurries past the stools lining the bar and is swallowed by a night that has pointed teeth and is yawning . . . In the room the waiters come and go I speak-ing of Antonin Artaud . ."

Here, the subject's perceptions combine elements of hostility and anxiety; while at the same time, as previously noted, his peception of the guide was very positive and included a slight distortion of appear-ance "in favor" of the guide. Also, in this case most of the distortions are not, with respect to vision, so drastic as in the examples just cited. Most of the same perceptions might have been possible without the drug; but they are lopsided in their emphasis.

'The distorted visual perceptions of the psychedelic drug subject sometimes have been equated with caricatures; but while this appears to be a fairly plausible observation in some cases, it is not so in others. Among the possible resemblances to caricature, in some of the subjects' perceptions a single aspect of the physical appearance or apparent char-acter of a person may be seized upon, overemphasized, and then em-ployed to sum up, as it were, the one perceived. We find here the mental economy or minimized expenditure of thought associated with caricature. However, unlike caricature, there need be no conscious hostility or aggressive intent. Nor is it necessarily some defect of the one "carica-tured" that is exaggerated. And while the facial expression may be distorted into a grimace, it would seem that the same mental process as regards method may be utilized to transform the countenance in the direction of enhanced beauty, serenity, strength or some other positive attribute.

It is true that every visual distortion of the other is to some extent gratuitous and a violation of the other that transmutes him into some-thing "not himself." It is also true that the majority of distortions, whether in the direction of the beautiful or of the grotesque, involve a reduction and oversimplification. If we wish, when the other is rendered ugly, grotesque or ridiculous, we may regard the process and its product as caricature. But what then shall we call the same process when the end-product exhalts or enhances in some way the person thus perceived?i

Apart from the guide, most positive distortions are of individuals well known to the subject and towards whom he is very favorably disposed. In general, love, strong friendship, and desire are productive of visual distortions that may suffuse another with extraordinary beauty or some other much-valued attribute. Some of these positive distortions, subjects say, involve not a reduction but rather a "complexification" of the other, a "symbolization" of the other's now-known complexity with all of the richness of the other visible in the perceptual distortion at the same time it is conceptually apprehended.

'These "rich" and "complexified" perceptions of the other often are described by subjects as being not distortions, but valid perceptions. The distorted perception was the old one that denied the other her due and derived from habit, conditioned response, accumulation of griev-ances, and so on. This phenomenon of perceiving, in the drug session, the other as she "really is" has been likened to a kind of deja vu. "Suddenly one turns the corner and sees the other in terms of a richness once seen, but lost through over-familiarity. With this perception, closed circuits are reopened and the persons communicate in ways and on levels long inaccessible to them. Also, new circuits may be opened and new ways of communication become possible." (Subject's descrip-tion.) Or the subject may feel he is seeing the other in all her richness and complexity for the first time.

Ambivalence with regard to the other may yield a particularly rich variety of perceptions, with the other seen alternately as ugly, drab, beautiful, or whatever, often in terms of the specific relation in which the two persons temporarily find themselves. For example, a woman may perceive her husband as extremely handsome in his role as intel-lectual companion; and then, should he attempt to exert his authority as "head of 'the household," perceive him as a shrunken, ridiculous, and inept figure. Such perceptions may, but do not always, point to specific areas of conflict of which the subjects were unaware.

In another type of common visual distortion, the other person is perceived as surrounded by or extruding intricate patterns of wires, loops, electrical and color wave emanations. In a typical case of this kind S-5, a male in his early thirties (LSD), first looked into a mirror and saw himself as the source of great circular loops of neon wires that entirely surrounded him. 'The loops were many—"hundreds of thousands"—and consisted of his attachments to himself and to every aspect of his life—"memory loops, love loops, hate loops, eating loops, mental block loops." Upon re-entering the living room he saw his wife and immediately became absorbed in studying her since she, too, appeared to him to be surrounded by her loops. He had always thought of her as being "a rather simple person" and was "altogether amazed to discover that she is every bit as complicated as I am." Subsequent to his session, and for about a week, the subject claimed to be able to see dimly a tangle of loops surrounding himself, his wife, and almost everyone with whom he came in contact. 'These were not, he emphasized, "meaning-less hallucinations," but revealed to him something important about the character of the other person.

S said that this experience was especially helpful to him in under-standing his wife and coming to know her as the "subtle and complex being she really is." This recognition, he felt, had enabled him to "react to her on many more levels" than was possible in the past. As he considered the phenomenon he decided that in large measure he was recapturing a view of his wife that he had had at the time of their marriage. "Habit had withered and custom staled the infinite variety of her ways," at least for him. But, in his session, he had "reappropriated her complexity" and now took it into account in his relationship with her.

Of 25 LSD subjects who experienced this perceptual and ideational recognition of the richness and complexity of the other, 19 were of the opinion that the recognition was of actual values residing in the other, not just a projection produced by wishful thinking, a momentary up-surge of affection, or whatever. The subjects generally felt that with the passage of time they had conditioned themselves not only to simplify their perception of the other, but also to place the emphasis on her poverty. For the most part, it was the guide's opinion that these subjects were in fact recognizing real, not just illusory, values in the other person.

In another fairly common departure from normal perception, the other is seen in terms of his "potential." In a very simple case of this kind, S-6, a housewife (LSD), perceived her rather corpulent husband as "basically thin." After the session she continued to insist to the husband that his personality really belonged with a much more slender body. Whatever his reasons, the husband agreed that the wife's percep-tion was of an easily fulfilled potential and that his personality would be better suited to a slender body. In only six months he had dropped 30 pounds and it was generally agreed that his "new" body was much better suited to his personality than the former fat body had been.

As a final example of visual change, some subjects, for periods of varying duration, experience feelings of "universal love," "fellow-feeling," or "love for all mankind." This state results in most cases in positive visual distortions with other persons being seen as all very beautiful, loving, friendly, and good. These eruptions of universal love will be discussed at some length later on in this chapter.

There are, of course, many implications present in this perceptual material. Here we will remark that if, as we believe, the drug-state distortions are magnifications of tendencies found also in "normal" perception, then they afford unique opportunities for studying the per-ceptual process..

Communication. Another often strikingly unusual aspect of interper-sonal relations in the psychedelic drug state is communication. Factors of especial importance in producing the peculiarly "psychedelic" vari-eties of communication include the following: the much-increased tempo of thought; feelings of empathy; heightened sensitivity to nuances of language and to non-verbal cues; greater use of gestures and shifts of posture and facial expression as means of communicating; the sense that communication is multileveled and much more meaningful than at other times; the sense that words are useless because the experience is "ineffable"; the feeling that communication by telepathic and other "extrasensory" means is possible; and the illusion that one is communi-cating when one is not—particularly, that one has given voice to a message when actually nothing was said.

Subjects may range from the gamilous to the taciturn, depending upon a great variety of factors apart from the usual behavioral pattern. In general, the peyote subject is more talkative than the person taking LSD; and the larger doses of LSD are most productive of speech econ-omy, the subject variously preferring nonverbal methods, feeling that fewer words are needed to convey his message, or developing the men-tioned illusion that he has said a great deal when in fact the message has remained on the level of thought. Since in general LSD, particularly in doses of 200 micrograms and upwards, yields the more interesting phenomena, the examples to be found in this section will be of LSD subject communication.

To expand a bit upon the foregoing, it is common for a drug subject to feel that because of the rapidity with which his thoughts unfold, it is impossible to communicate by ordinary means and so he must abandon the effort or develop new means more adequate to the situation. He may also feel that speech is largely superfluous since the high degree of empathic communion has made him very communicative on even the most subliminal levels—from one spoken word conveying a bookful of ideas and associations, on to total telepathic communication. Also, he may feel that gestures, postures, and subtle shifts of facial expression, on the part of both himself and the other(s), can communicate volumes of material otherwise verbally inexpressible. Subjects thus may think that they are doing a highly effective job of communicating with one another even though very little in the way of speech passes between them. Nor is it possible to say with certainty that they are always wrong, or that communication by other, still less orthodox means does not occur. Sub-jects repeatedly insist with some vehemence that they are able to "tune in" directly on the moods and thoughts of the guide and other persons, especially other persons who also are taking the drug. 'They sometimes seem to do so, and any assertion that they always are actually picking up ordinary sensory cues cannot be based on the guide's visual observa-tions and has to be based on the assumption that the subject is alert to cues the guide has missed. Underlying such an assumption, of course, usually will be a theoretically grounded rejection of the possibility that such phenomena as telepathy can exist.

The conveying and receiving of complicated messages, without the normal amount of verbalization, is made possible also by the subject's alertness to nuances of language. Double meanings and other word plays may be picked up instantly. Apparently simple statements and even single words yield manifold meanings and implications that all seem simultaneously accessible. Much speech that ordinarily would be needed now seems pruned away and the result is a terse and cryptic spoken "shorthand" that may be entirely satisfactory to the subject but is likely to be enigmatic to others.

For example, two subjects, S-7 and S-8, were participants in a group session. Previous to the session these two men had only a nodding acquaintance. But during the session they sat across a table from one another and communicated "psychedelically," later feeling that many thousands of words had been interchanged (although aware that spoken words had been few). They considered this "conversation" the most meaningful, interesting and important of their lives. The interchange, although brief when written down, consumed one-half to three-quarters of an hour and went approximately as follows:

S-7: Smiles at S-8

S-8: Nods vigorously in response.

S-7: Slowly scratches his head.

S-8: Waves one finger before his nose.

S-7: "Tides."

S-8: "Of course."

S-7: Points a finger at S-8.

S-8: Touches a finger to his temple.

S-7: "And the way?"

S-8: "We try."

S-7: "Holy waters."

S-8: Makes some strange apparent sign of benediction over his own head and then makes the same sign toward S-7.

S-7: "Amen."

S-8: "Amen."

These subjects said that they had initially become aware of a deep bond of mutually shared feelings and ideas that united them. Their "conversation" had ranged over "the human condition" and such sub-jects as cosmology, theology, and ethics, to a shared exploration of the significance of each to the other and, finally, of their personal relation-ship to the Infinite. They had felt themselves at all times to be in a rare state of accord and understanding. Much had been conveyed, they added, by slight gestures and changes of facial expression that had escaped the guide's attention.

Apparently successful complex communication, effected mainly by extra-verbal means, can be intensely interesting, instructive and also disturbing to a person with preconceived ideas about what is possible in this area.

S-9. Male. Graduate student in philosophy. At the time of his ses-sion S was largely committed to logical positivism and was writing a dissertation dealing mainly with Wittgenstein and A.J. Ayer. S's inter-pretation of positivism tended to put the whole burden of the world's meaning on the interrelationships of words. He was ordinarily an inces-sant talker who would, however, speak for hours without making a single gesture and with virtually no change in his facial expression.

In the drug state, S almost totally reversed his behavioral pattern in this respect. He lapsed into lengthy periods of silence broken from time to time by a "loaded" single word or brief phrase or by gestures aimed at the guide or at various objects in the room. Surprisingly, the guide found these occasional words and gestures to be quite meaningful and often very rich in content. Subsequent reconstruction of the session indicated that S had managed to convey a great deal of what he had intended to communicate.

During the post-session talk S said that while in the drug state he had felt that his thought processes, although extremely complex and subtle, still were largely pre-logical and therefore pre-verbal. He thus had found it necessary to communicate his feelings by the use of an occasional "ur-word" or by means of gestures and facial expressions.

S said that he recognized very clearly the "somewhat mystical im-plications" of this statement and felt that he should be "extremely skeptical" about what he had said. Yet, at the same time, he had the feeling that his experience and analysis of it were valid and cast serious doubt on many of his previous philosophical certainties. His doubt deepened as he began to suspect that the experience which at first he had interpreted as a regressive preverbal one also could be seen, "be-cause of its complexity, as a kind of evolutionary preview into future post-verbal modes of communication."

Whether this subject is to be regarded as helped or harmed by his drug experience will depend upon how one evaluates the merits of his subsequent actions and ideas. Continuing to grapple wiih the insights he had gained, he became increasingly dissatisfied with his dissertation and finally abandoned it altogether. With much additional expenditure of time and energy he wrote a new dissertation, switching his allegiance to a philosopher about as opposed to Wittgenstein as could be.

While LSD inhibits or seems to minimize the need for speech in some cases, in other instances the subjects become more verbose than usual and sometimes much more eloquent. The loquacious subject may talk a great de,a1 because he finds that he has many important ideas he wants to share and has also the capacity to express them. Or, he may talk a great deal because he is anxious or confused and talking helps him preserve his sense of identity and his contact with some supportive figure. It is not always easy for the guide to determine which of these motives is operative.

A few subjects seem to achieve a previously unparalleled lucidity while in the drug-state. Individuals who norrnally limit their conversa-tion to routine small talk may speak with some brilliance of a great variety of matters or make extensive analyses of their own mental pro-cesses as affected by the drug. These are not always persons who are "starved for good conversation." Those who know them may be aston-ished at the comparative erudition and talent for conversation they display. Two such subjects have continued to be more effective conver-sationalists after their sessions; but most at once relapse into their former chitchat and declare themselves baffled by the temporary verbal facility and regretful at its loss. These are not, it ought to be added, uneducated persons or persons of low intelligence. They are inarticulate persons who presumably drew upon information always accessible but rarely put to use in conversation and, in some cases, rarely thought about.

The varieties of illusory communication encountered in the sessions are also of considerable interest. In the first example we have the case of an LSD subject, S-10, whose wife was on hand for a portion of his session but did not take the drug. As reconstructed and substantially condensed, the following brief interchange between S and his wife W was heard and respectively assimilated by them about like this:

S says: "You are looking very beautiful." With these words S means to convey, and thinks he has conveyed: "I have just recognized to what extent I have lost sight of all your good qualities. I used to see them, but somehow I developed a sort of blindness. Now, however, I am seeing you as the beautiful person you truly are, and I intend to maintain this recognition after my session so that we will be able to recapture all the happiness we once had."

W says: "It may be just the drug, but I appreciate the compliment." W means to convey, and thinks she has conveyed: just what she said, although her enthusiasm for the compliment is not great.

S understands W to have meant: "I am going to accept this statement of your good intentions for the time being, but will wait and see whether you still feel the same way after you are out of it. You have done a good many things I didn't like, but I can still forgive you if you

will change. I do love you and I understand that you want to do better."

S says: "You're smiling. Are you happy?" S means and thinks he has conveyed: "I can see by your smile that you are very pleased with what I have been saying. You may still have a few doubts, and so may not yet be completely happy, but I see that you are much happier than before and things are going to get even better. You are very understand-ing and seem somehow to sense what I know to be true, that I am a greatly changed person who means every word that he says and who is going to treat you much better from now on. Just seeing you so happy is reward enough for me. Now that we have arrived at a real understand-ing . .

W says: "Oh, yes." W means: Nothing very much. She is just being agreeable. W is thinking: "Naturally I smiled. He looks pretty funny all stretched out on the floor there. Well, at least he doesn't seem too crazy and nothing else bad has happened either. He has several more hours to go, but everything seems okay so I can leave pretty soon and spend the rest of the afternoon shopping with my mother."

S understands W to have meant: "Oh! Yes! I am very, very happy! I can see now that you really mean what you have been saying and really are changed. We are communicating so fully, understanding each other as we never did before. We are not talking much, but who needs words? You are revealing yourself to me and I am revealing myself to you in many, many ways all at once. Ohl Yes! Now that we have broken through all the barriers that used to separate us, we love one another as never before and will go on loving one another like that. I am so happy!"

In the above example of illusory drug-state communication, S first supposes that W has understood all that he meant and thought that he had conveyed by his words. In addition to this, S believes that he has received from W answers never given to messages never sent, much less received by W. In the following example, S-112 was visited during his session by a girl he was in love with but had never found the courage to tell about his feelings. He believed at the time of the session and also afterwards that he had spent several hours telling this girl how much he loved her. In fact, his "long declaration of love" was never made at all and the few words he spoke to her over a period of several hours were innocuous when not almost meaningless. (He had taken a large, 350 microgram dose of LSD and in spite of having had much previous psychedelic drug experience became confused and sometimes inco-herent.) What S actually said during a portion of her visit, and his account of what he thought he had said, are as follows:

S looks with eye; closed at images and remarks: "I see a big jeweled butterfly." Opens his eyes and looks at his beloved (B) through some pussy willows standing in a Japanese vase: "How beautiful. Oriental. No, now you look Greek." Closes his eyes and observes more images. "Greek again. A forest. I hear music. Now it seems to be Aztec." Long pause. "So many places. So many times." Long pause. "Computers. We're just computers. It is very bad. No, I don't know why." Lies on a couch with eyes closed for a long time, then looks over at B. "I am so sorry. I mean, you must be bored .. ."

Occasionally, during this period, B made brief inquiries as to what S was seeing or asked him to elaborate on something he had said. How-ever, B admitted later that she was preoccupied at the time and had paid only minimal attention to S. She had been present at psychedelic drug sessions before and found this one comparatively dull. B says that she had no idea at the time that S loved her, much less that he was proclaiming his love to her. S, for his part, seemed to ignore or gave very terse responses to B's few attempts at conversation.

Later, however, S wrote a report more than 50 pages long detailing what he thought he had communicated to B. We here quote a few excerpts from the passages corresponding to his actual words as re-produced above:

"From above me, many-hued, its giant vvings fluttering, the great jeweled moth descends and alights upon the table and the wings, as I open my eyes, have become translucent, brilliant, incredibly fragile fans that you are holding and that pass for an instant across your face, then, unmoving, become its frame. Between the silken fans—which I know to be flowers, but which are fans still—your face is oriental: very white, as if heavily powdered or painted, but unbelievably, exotically beautiful. And now, between the brown branches, studded with their small soft buds, it is equally beautiful but classically Grecian. Forgive me if I fail to understand you when you speak. It is my apprehension of your beauty that destroys my capacity to focus upon your words.

"Standing, in another time and place where I observe you only from a distance, you are Rhea: yawning black mouths of caverns at your back and panthers and lions at your side. 'The green depths of the forest ring with the cries of your worshipers, the night descends slowly, and the torches borne by the procession of your priests illumine—what again is this room, where you are standing and seeming to listen to what I, too, am he,aring . . . For even at this moment, in this room, from far off, as if echoing across time from the depths of a torch-illumined forest, there lingers the sound of horn and pipe, of drum and castanet. But we are Aztecs now, and you are my queen, and your hair frames a beauty turned barbaric and cruel as the eyes of a tiger. Before us assembled multitudes cry out as you raise an arm heavy with flat golden bracelets and rings of unparalleled brilliance glow in a moonlight that encircles and suffuses the sacred enclosure where we stand.

"Atop a pyramid, studded with what seem great buttons of ivory, inlaid with sapphires, rubies and emeralds, again we are standing side by side. My arms are bare, bronzed and heavily muscled, and in my hand is a sword around which a living, writhing serpent is entwined.. . .

"In all of those times, in all of those places, but now I seem so old and you—you are always, unchangingly just as you were then.

"It seems to me that I think only of love, speak only of love, and that you are telling me: `Go on. Go on. Go on.' ...

"Floods of images: the mind's interior—we are computers, feeding one another, incessantly feeding one another, and linked by tapes that emerge from one metallic surface to vanish into the other. My flesh is crawling and my heart is made of brass. How dismal to be computers, and how terrible to be linked to you only by tapes. . . .

"Always, again and again, I come back to the single theme of my love for you. I would like to change the subject—free you from my monomania. I have forced myself to fall silent; to think a thousand thoughts, about different times, places, things; yet my ideas, however remote they seem at first, invariably refer back, as I see all too quickly, to the single, inescapable source of my obsession.

"I send my mind floating down swift streams and over waterfalls; roll my self up in a ball that is fired at targets distant as stars; strive to thrust my thoughts into an orbit that will circle and center upon any-thing, anyplace, anyone else—and cannot avoid or renounce the rejoicing that accompanies the succession of my failures.

"'The walls dance, the ceiling shimmers, tiny red wisps of light go darting, sometimes to collide and explode or unite, through the spaces above me. My awareness—fragmented—focuses with what seems equal intensity upon a dozen or more objects: vase, ashtray, pillow, painting, window, the arrn of a chair, the leg of a table, sounds, smells (for these are to me at the moment as much objects as the rest), a radiator, my own hands and feet—I apprehend them all, my thoughts circle around them, envelop them, take them in from every perspective—but as satellites of you!

"All of this, I feel—I know—is unjust, unfair, an unwarranted talcing advantage of our present situation. You have come here be-cause I told you I might need you, yet I use this occasion almost wholly as a means of furthering my relentless efforts to possess you. I am ashamed of what seems an exploitation, and is surely ingratitude; yet my love for you is so great I no longer am able to contain it...."

Such examples of illusory communication as the foregoing should not be isolated and then used as weapons against the psychedelic drug experience. Important authentic communication also takes place as numerous instances cited in this book repeatedly demonstrate. Here, as in many other areas of the drug experience, we encounter a curious blending of the valuable with the bizarre. Also, even the bizarre or ludicrous experience may be of value in terms of long-range conse-quences. For example, S-10 did in fact change his thinking about his wife and their relationship improved as a result. Much of life's happi-ness, after all, flows out of one illusion or another.

Empathy. About ninety per cent of our psychedelic drug subjects have experienced at least once some state of mind that many term "empa-thy." These experiences, while to some extent similar, are not identical and in particular cases subjects seem to be talking about sympathy, accord, concord, rapport, affinity, psychological correspondence, under-standing, likemindedness, union, communion, or some combination of these. We will discuss these various states under the heading of "empa-thy"—indicating our reservations by placing the term in quotation marks.3

In the more common varieties of "empathy," the subject identifies with another person much as an actor may identify with his role, then feels he has gained a high degree of understanding of that other; by a kind of "reverse empathy" the subject assimilates an other into himself, rather than "feeling" himself into the other; or his experience resembles sympathy, defined as "a similar relation between persons whereby the condition of one induces a responsive condition in an-other." Or, here, we may take a definition from physics—"the relation between two bodies whereby vibrations in one produce responsive vi-brations in the other"—and substitute psyche or self for body.

At the extremes of the "empathic" experience, are solipsism on the one hand, and mystical union on the other hand. Typically, the solipsistic subject appropriates the other person, the other 'being drawn into oneself and regarded as a part or extension of oneself, or even as nothing more than a product of one's imagination. In the mystical union, with its sense of "I am You—We are One," the self is described as being finally extinguished altogether. The solipsistic experience, be-cause it denies the separate independent reality of the other, yields little of value and when described as "empathy" is only an illusion of empa-thy. Distinctions between the mystical and empathic experiences will be made in our discussion of mysticism.

There is also a variety or type of drug-state "empathy" that should be regarded as one of the most important experiences available to psy-chedelic subjects. 'The condition referred to might be imperfectly de-scribed as one in which distinctions between I and You, or I and It, become blurred and the subject-object relation between persons seems to yield to a sense of mutual intermingling with openness to and knowl-edge of the other. In this seemingly most genuine, and definitely most transformative, of "empathic" states there remains an awareness of the respective identities of the self and of the other. At the same time, individuation no longer imposes the usual insularity. Among the follow-ing cases, Subjects 14, 15 and 16 are of this type.

Since a subject's daim that he has experienced "empathy" has to be mainly assessed in terms of his description of his own subjective state, the content and validity of the experience elude exact evaluation. How-ever, certain phenomena sometimes occurring within the "empathic" context tend to support the claim of a breaking through the normal boundaries separating persons. 'The simultaneous sharing of images and visual patterns and apparent telepathic communication are examples of experiences supporting the claim. Instances of the latter, with accounts of experiments, are given in the section to follow.

S-12, a musician, and his wife, S-13, first had separate LSD sessions and then had a session together. 'The husband was having an affair with another woman at the time and this had given rise to conflict between him and his wife.

During their joint session the subjects repeatedly claimed to experi-ence identical or almost identical eyes-closed images and also ideas. This remarkable phenomenon both astonished and delighted the couple. They declared themselves "LSD twins" and embarked on a lengthy mutual exploration of the meaning and implications of what they had experienced. Particularly impressive to these two was the "fact" that they many times found themselves simultaneously seeing (imaging) themselves together in various ancient cultures.

One cannot rule out in this case the possibility of a well-intentioned dishonesty. One of the subjects may have claimed to be experiencing what the other was experiencing, and then the two of them jointly played the game from there. However that may be, the couple said that they felt themselves "reborn" to a new sense of unity and harmony. Six months later, the husband had gotten rid of his mistress and the mar-riage was prospering as a consequence. One year later, he had the mistress back—but the marriage was prospering in spite of it. Rightly or wrongly, the definite and still-lasting improvement in their relation-ship was attributed by the couple to their "empathic" LSD experience and subsequent analysis and reinforcement of it.

A still more unusual case of this sort occurred in a session in which two of the five participating subjects were twin sisters. These twins, S-14 and S-15, achieved a degree of what they called "empathy" that bordered on the eerie.

During their childhood the mother of these girls had done every-thing she could to make one sister literally indistinguishable from the other. The twin sisters were given identical clothing, identical haircuts, and compelled to engage in all of the same activities together. So suc-cessful was the mother that she herself often could not tell one child from the other one.

By the time the two girls were thirteen years old, each deeply re-sented the other. Each wanted to be "a real individual, not just one half of a Siamese-twin team." 'The effect of this resentment, as the two grew older, was for each to differentiate herself as totally as possible from the other. In their teens, one sister decided on a science career, the other decided on the arts. They dressed in opposite styles and if one sister was wearing her hair long, the other wore it short. By the time they were thirty, one sister had become a physician and the other was an avant-garde painter. They were still strongly antagonistic, quarreled heatedly over the most trivial matters, and continued to dress and to wear their hair in very different styles. Even so, and although both denied it, the resemblance between them was considerable.

Despite their apparent mutual hostility the twins saw one another fairly often and one sister arranged for the other to be a co-subject at the group session. For the first hour or two of the session, the pair kept up their customary bickering. Then they became absorbed in their altered sense perceptions and images and soon began comparing notes. To their astonishment each was experiencing almost the same changes of perception and the same images experienced by the other. They repeatedly inquired of the three other subjects in the room what those subjects were experiencing; and found, somewhat to their dismay, that the others were having quite different and highly individualized experi-ences.

The twins also discovered that they were reacting almost identically to ideas and people, finding the same things funny or sad for the same reasons, and drawing similar conclusions about their co-subjects. They went on comparing notes for some time, beginning to enjoy their "inex-plicable mutuality," until a man in the room complained that they should keep their "Gemini perceptions" to themselves and asked, "Christ, don't either of you exist apart from the other one?" He added that the twins looked to him "like one person with two heads and four legs."

These remarks had a strong effect on the twins, who reacted by intensely contemplating one another for a long time. At first they gig-gled at one another nervously, but then became pensive and finally appeared to be in a profound and almost trancelike sort of communion. It was while in this "empathic" state, they said later, that they had discovered themselves to be "essentially the same person." Each woman proclaimed herself to be "variations on my twin," but declared that the "overlapping of identities" no longer was a source of discomfort.

The effect of this experience was to make the sisters "great friends" —and so they have remained for more than two years. At a time when one sister was going on a trip, she solicitously urged a family friend to "take care of my other self"—something she "could never possibly have said" previous to the LSD session.

It might be added that among the most unusual examples of shared experience in this case were several involving a shared synesthesia. Both women claimed to react to the same piece of music by "seeing the sounds"; and later, looking at the painting, they both said that they were able to "taste the color red." Again, in this case, we have the possibility of deception; but here it seems unlikely.

A fairly common component of the "empathic" experience is the illusion on the part of one subject or both of an interconnectedness of the bodies of the two persons. S-16, an LSD subject, described an "empathy process" in which he gradually became aware of "neural and dermal fibers of communication" extending from himself toward the other and from the other toward himself. Gradually these fibers "grew together and meshed into a total tapestry" containing his "life and the life of the other." S felt during this experience that he "knew" the other as he had never known her before, and had discovered and even literally "felt" values in her of which he previously had been unaware. These values were first experienced by him as "colored threads, color tones of the mutual tapestry," before they became "cerebrated as specific values."

In another, somewhat similar case the subject, S-17, first experi-enced his "empathy" in terms of the "physically felt rhythms" of the other person. Whether these rhythms were bodily processes, heart beats, humming nerves, S could never decide to his own satisfaction. But he "felt" and later "heard" the other person as a "symphonic complex with a great range of percussive beats." He expressed his "empathy" by "entering into the music and rhythms" of the other, swaying and snap-ping his fingers to the other's "orchestration." The person with whom S was "empathizing" responded with delight to this "musical rapproche-ment" and swayed and snapped along with him.

Drug-state "empathy" often begins with a feeling of great looseness, unknitting, and relaxation on the part of the subject. This feeling then may pass over into one of liquefying, flowing or becoming oceanic. At this point the body boundaries may be experienced as melting and indefinite, so that the subject may find himself uncertain as to where his "body leaves off and its surroundings begin." Finally, the psyche or self may seem permeable, transcendent and "empathic."

Subjects experiencing this unknitting and dissolving of boundaries, self-transendence and receptivity are likely to attribute a similar condi-tion to the person with whom they enter into an "empathic" relation-ship. But such an attribution may be only a projection, and then the subject may experience a genuine feeling of "empathy" on his own part while erroneously believing that the other is also "empathizing" with him.

For example, during a group LSD session, a male subject, S-18, told a female friend: "Walls are falling away from me. My walls are crum-bling down." He then observed her closely for a while and added: "And your walls are falling away, too. You're not so damned enigmatic as you usually are. I feel for the first time that I really know you." S told the guide later in the session that he had felt an intense communion with his friend, "a communion much closer than any sexual communion."

On the other hand his friend, also taking LSD, told the guide that throughout her session she had felt "no empathy whatsoever" with S. On the contrary, she had mostly felt that the two were "different island universes drifting in space and not at all related to one another. His contemplating me so intensely merely annoyed me and I thought: `How dare you try to encroach upon my universe!' I felt that his contempla-tion of me was a terrible invasion of my privacy." Had his friend been less honest, perhaps "just to be agreeable," S today might be extolling LSD "empathy" instead of proclaiming his "skepticism" with regard to it.

Finally, it might be added that "empathy" with objects or with music is much more common than "empathy" with persons. It is also easier and for most more enjoyable, subjects frequently explaining that "things" do not resist one's effort to "empathize" with them as persons often do. Also, the "empathizing" subject may be extremely sensitive to feelings of indifference or hostility on the part of others and his "empathic" forays into the other thus may meet with painful psychic snubs.

Successful "empathy" with things may enable the subject to move on to successful "empathy" with persons. Here, as in some other expe-riences to be examined, the nonhuman world is often the gateway to the world of the human. And the Thing-World is one that some subjects must traverse and come to terms with before they are able to accept and find acceptance in the World of Other Persons.

"Telepathic" and Other "ESP" Phenomena. We have mentioned on a number of occasions the daims by psychedelic drug subjects that they are able to communicate "telepathically," particularly that they are able to "read the minds" of other persons. This alleged capacity seems to function at its best within the context of an "empathic" relationship; but it is said to function in other contexts as well.

In addition to this claim of a drug-induced or "drug-liberated" telepathic capacity, subjects from time to time report experiences that they feel involve other varieties of extra-sensory perception (ESP). For example, they may claim to be able to see or otherwise know what is taking place outside their own environment (clairvoyance); to be able to obtain from an object something of its past history ("psychometry"); or to be able to see or know future events.

Should the psychedelic drugs in fact be a means whereby certain ESP faculties in man could be made operational and effective, then the significance of these drugs for interpersonal relations would of course be enormous.

Since very remote times there has existed a lore associating psyche-delic and hallucinogenic drugs with a broad range of ESP and occult phenomena. Some of this lore undoubtedly refers to actual oc-currences, but ones which may be understood without appealing to ESP. For example, the use of various Solanyceae derivatives by witches appears to make intelligible to us on a scientific level many phenomena formerly seen as involving elements of the supernatural.

On the other hand, there are legends and writings by old historians describing events that do not easily lend themselves to explanations acceptable to most present-day scientists. To take a very early example, it often has been suggested that the priestesses of some of the Greek oracles made use of hallucinogenic drugs to activate clairvoyant and other paranormal faculties. Descriptions of the behavior of the pythian priestesses of the oracle at Delphi lead the authors of this book to condude that again one or more plants containing the Solanaceae drugs was employed.

Some of the most impressive of the more recent reports of "tele-pathic" (or clairvoyant) phenomena associated with psychedelic drugs involve a psychochemical found in the western Amazon region and first discovered in 1850. The narcotic derivative or group of closely related derivatives is known variously as ayahuasca, caapi, yage and tele-pathine. The principal allcaloid producing the psychedelic effects is probably harmine, but some other chemicals also seem to be involved in the production. Despite various studies over the years, caapi, etc., re-mains but poorly understood.

In 1927, Dr. William McGovern, assistant curator of South Ameri-can Ethnology, Field Museum of Natural History, provided one of a number of reports attributing apparent "telepathic" powers to the indi-vidual ingesting a drink prepared from the Banisteriopsis caapi.4

Describing some of the effects of caapi, which he took with the natives of an Amazon village, McGovern wrote:

"Curiously enough, certain of the Indians fell into a particularly deep state of trance, in which they possessed what appeared to be telepathic powers. Two or three of the men described in great detail what was going on in malokas hundreds of miles away, many of which they had never visited, and the inhabitants of which they had never seen, but which seemed to tally exactly with what I knew of the places and peoples concerned. More extraordinary still, on this particular eve-ning, the local medicine-man told me that the chief of a certain tribe on the faraway Pira Parana had suddenly died. I entered this statement in my diary and many weeks later, when we came to the tribe in question, I found that the witch doctor's statement had been true in every detail. Possibly all these cases were mere coincidences."

Similarly, in 1932, a Brazilian colonel named Morales experienced for himself the seeming telepathic or clairvoyant properties of yage.5

Colonel Morales "was on a military mission far up the headwaters territory of the Amazon, toward the borders with Eastern Peru, when he heard from an old Indian about this queer plant. Morales, by way of an experiment, drank a decoction of it. It produced on him an amazing, hyperesthetic effect which seemed to dilate the normal consciousness. He asserts that he heard the music of an orchestra playing in what was apparently American surroundings. He says he also became conscious of the death of his sister in a house far away from where he was located. 'The house was in Rio de Janeiro some 2,900 miles distant, as the crow flies, from the remote village where he then was. A month later, a runner brought him a letter ... telling him that his sister had died about the time Morales had drunk the infusion of the yage plant...."

Since LSD is of rather recent vintage (psychedelic properties dis-covered in April, 1943), it has no ancient history and lore of strange events; only a monumental recent lore. Peyote, however, has a history of use for the purpose of inducing telepathic, clairvoyant, prophetic, necromantic and other capacities going back well beyond the fifteenth century. Several decades ago the principal peyote alkaloid, mescaline, was already being tested to determine the validity of claims that tele-pathic communication was possible in the drug-state. Dr. Felix Marti-Ibaez writes° that "Even as a medical student, I had heard about mescaline experiments. A renovvned Spanish pharmacologist, Dr. Bascompte Lakanal, had told me of the work being done at the Pasteur Institute in Paris using mescaline. An alkaloid from the Mexican cactus peyote, mescaline caused a 'luminous drunkenness' in which the world turned into an orgy of color, a bacchanal of swirling lights, a rainbow symphony. 'The most extraordinary result was that, when telepathic experiments were carried out with the mescalinized volunteers, they could reproduce words, sketches, and musical notes, pronounced, sung, or drawn by other people in a distant room of the same institute. Some physicians then began to wonder whether the pharmacologie arsenal had not become enriched by its first 'telepathic drug!' "

Concerning these few instances we have mentioned, and many oth-ers of which we have knowledge, we maintain a position of open-minded skepticism. They are cited only as fairly typical examples of the lore of ESP phenomena as it has been associated with the psychedelic drugs.

Attempts of the last decade or so to demonstrate ESP-enhancing properties of LSD, mescaline and similar chemicals have been incon-clusive—when not plainly abortive—in experiments with both "sensi-tives" and persons not aware of possessing any ESP capacities. A num-ber of instances of apparent telepathy, precognition, clairvoyance, and clairaudience have been reported, but seemingly they occurred with no greater frequency than in experiments where no drug is administered. Psychedelic drugs are said to have worsened the performances of some experimental subjects. In other cases, the plus deviation from the usual performance was less than noted when tranquilizers and amphetamines were given.

The theory often underlying such use of the psycho-chemicals is that ESP is a natural faculty of mind that is inhibited or kept inoperative by the production of body chemicals developed in the course of human evolution to serve just that inhibitory purpose. 'The inhibiting chemicals, that is, served to prevent man from perceiving a "larger reality" that would be too distracting and so interfere with his survival and progress in the world. 'The "medium" or "sensitive," then, is a person whose body does not produce these chemicals in the normal amount and whose mind, therefore, is not normally inhibited. If, as has been argued, psychedelic drugs "inhibit the inhibitors," then the drug subject might be able to experience what the medium experiences?

As noted, however, experimental ESP results do not seem suffi-ciently impressive to compel our acceptance of this theory. But the theory is not thereby discredited, since parapsychologists have noted a variety of factors that might have a detrimental effect upon ESP per-formance even where the potential for improved performance has been activated by the drug.

The present authors, as noted, are skeptics with regard to parapsy-chology and the phenomena with which it is concerned; but, at the same time, we are not closed-minded or antagonistic. Some testing of LSD subjects has been done and we will present the results without making any claims of having conclusively proved anything.

Our efforts at demonstrating a drug-induced capacity for clair-voyance have yielded very little. Some subjects have reported themselves able to visit distant places and have "brought back" reports of what they "saw"; but all of these reports have tended to be vague and the more impressive instances still might be put down as "lucky guesses." A subject might be told, for example, to "go" to a house or apartment at a certain address where the occupant and general contents were known to the guide but not to the subject. A few subjects then gave fairly accurate information, describing persons and objects in the house. 'This is not, as some will note, a good test of "traveling clairvoyance" since the possi-bility of telepathy or the subject's "reading the mind" of the guide has not been excluded.

S-19, a housewife in her mid-thirties, complained in the course of a LSD session that she could "see" her little girl in the kitchen of their home and that the daughter was taking advantage of her mother's ab-sence to go looking for the cookie jar. S then further reported that the daughter was standing on a chair and rummaging through the kitchen cabinets. She "saw" the child knock a glass sugar bowl from a shelf and remarked that the bowl had shattered on the floor, spilling sugar all around.'

S forgot this episode, but when she returned home, after her session, she decided to make herself some coffee and then was unable to find the sugar bowl. She asked her husband where it was and he told her that while she was away their daughter had "made a mess," knocking the sugar bowl from the shelf and smashing it. The child had done this "while looking for the cookies."

Since the child often went looking for the cookies, and had almost smashed the sugar bowl before, it is easy to "explain away" this particu-lar incident. Apparently more baffling is a somewhat similar case in-volving a subject of another guide.

In this second case, a friend guiding a session phoned us to say that an LSD subject had reported seeing "a ship caught in ice floes, somewhere in the northern seas." She could read the name of the ship on its bow: it was the France. Two days after the phone call (and three days after the session), there appeared in the newspapers an item relat-ing that a ship had been freed after being trapped in ice, somewhere near Greenland. The ship was the France, which had gotten into trouble at about the time of the subject's session. There would seem to have been no earlier news items concerning the incident.

We have nothing of value to say concerning this type of phenome-non, which is heard of often enough where no psychedelic drug is involved.

Much more relevant to the present chapter are controlled experiments conducted by one of the authors (J. H.) in an effort to examine the validity of claims by subjects of "telepathic communication." The initial aim was to study various aspects of the "empathic" experience. However, testing is likely to disrupt the "empathic" state; and most subjects therefore had to be tested for "telepathic" capacity in the drug-state but outside the empathy context.

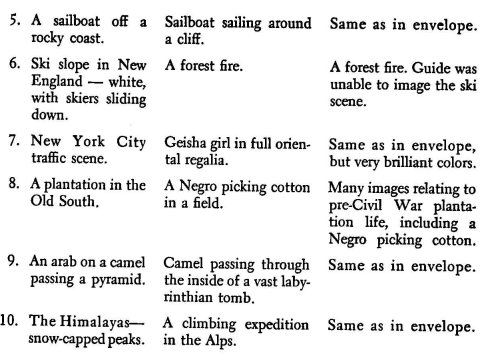

In an experiment involving 27 subjects, the guide used a standard 25-card Zehner ESP pack to test for possible changes in extra-sensory awareness on the part of the subjects. The guide's method was to sit across the room from the subject, running through the pack ten times (250 cards) and shuffling upon the completion of each 25-card run. She would lift up the top card, look at it and ask the subject to tell her what it was—circle, square, cross, star, or waves. She would put the card down, and make a note of the subject's response, and then go on to the next card.

Most of the subjects very quickly became bored with this process, regarding it as a waste of valuable psychedelic time. This subject resist-ance or indifference may have affected the results, especially in 23 cases where the subjects performed on the levels of chance or below chance, dropping to levels of two and three correct guesses out of a possible 25 toward the end of the testing.

The average test run (based on the ten runs) was as follows:

4 - 5 - 5 - 6 - 4 - 2 - 2 - 3 -1 - 3 (Score 3.5, or 1.5 below chance).

On the last five runs, where the scores fall off sharply, the subject was usually especially bored with the test and his resistance was in-creased accordingly. Some were apparently throwing out guesses with no attempt at all at telepathy. There remains, however, the possibility that the consistently below-chance scores on the last five runs might be an example of a kind of "negative telepathy," the resisting subject expressing his opposition to the process by misreading the cards. No subject, however, consciously tried to make mistakes as far as could be learned.

In the case of the remaining four subjects—a female (F) and three males (M)—the results were considerably and consistently above chance. It might be of significance here that each of the four subjects was a good friend of the guide and thus better motivated than the others to help her with the experiment. Also, a factor of greater claimed feelings of "empathy" on the part of these four should be noted. Their scores (averaged for the ten runs) were as follows:

M-1: 9 - 8 - 9 - 10 - 12 - 13 - 9 - 5 - 4 - 4

F-1: 8 - 13 - 10 - 11 - 8 - 11 - 9 - 10 - 6 - 5

M-2: 11 - 9 - 8 - 8 - 11 - 13 - 10 - 10 - 7 - 4

M-3: 8 - 7 - 10 - 12 - 9 - 11 - 4 - 6 - 4 - 3

Tested in a comparable non-LSD situation, only one of these sub-jects scored significantly above chance; and his performance remained well below that achieved with the LSD factor added. Even with these high scorers, one notes, performance tends to decline rather sharply for the last three runs. In an LSD context it does not seem feasible to try to inflict a series of more than ten runs on an experimental subject.

Of some other researchers with whose work we are acquainted, one sponsored a very large number of similar tests under psychedelic drug conditions with dismal results. On the other hand, another researcher, Andrija Puharich, reports that his testing demonstrates significant im-provement of the telepathic performance early in the drug (Amanita muscaria) experience. His data may be found in his book, Beyond Telepathy.9

Testing the hypothesis that the card test may be a poor one for the particular circumstances—or that card testing may be, as a subject charged, "psychedelically immoral"—an attempt was made to devise another test that would be more compatible with the subject's mental state and therefore more congenial to him. The guide had noticed that her subjects often seemed to pick up random images that crossed her mind; and the subjects seemed most adept at this in the case of images that had for the guide some emotogenic force—i.e., images that were esthetically, historically or otherwise personally potent or emotionally charged.

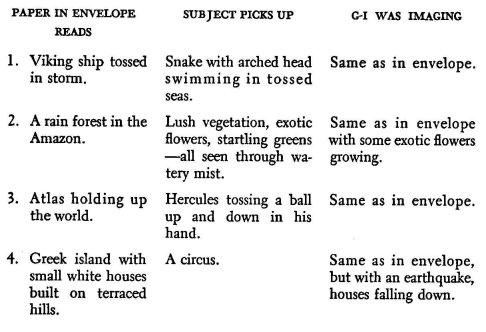

It was thus decided to write down ten such images and to place them in ten envelopes. The subject would sit across the room from the guide (G-1) or in an adjoining room with another guide (G-2). G-1 would pick up an envelope and image the scene described on the paper inside the envelope. 'The subject would relay what he had "picked up" to G-2, who would record the subject's words. G-1 would then say "Now!" and think of the scene described in the second envelope, and so on. After "sending" the contents of the ten envelopes, the image sent by G-1 would be compared with the description given by the subject. 'The number of approximations occurring with this test seemed significant. Out of 62 subjects tested, 48 approximated the guide's image two or more times out of ten. Five subjects approximated the guide's image seven and eight times out of ten.

By "approximation" is meant the following: 'The scene-Would be described on the paper in the envelope as "a Viking ship tossed in a storm." A subject would be considered to have approximated this if he reported, for example, "a snake with an arched head swimming in tossed seas." The paper in the envelope might read: "An arab on camelback passing pyramid." An approximation then might be "a mummy lying in a gilded sarcophagus."

In a number of cases an official error was attributed to the subject although the guide was unable to image the scene described in the envelope, but imaged something else. Or the guide might "lose" the initial image, and find it replaced by another. In some such cases the subject would accurately pick up the guide's "accidental image" instead of the written image she intended to transmit, but still would be charged with an error. The sealed envelope procedure was used as an additional control.

Of the 14 subjects who received less than two out of ten of the images, almost all were persons not well known to the guide or persons either experiencing anxiety or primarily interested in eliciting personal psychological material. The data on subject performance appear as in the following record of an especially high scoring subject:

Whatever else might be said of this test, there can be no doubt that the subjects greatly preferred it to the ESP-card testing. They felt that it grew more naturally out of the psychedelic drug experience; that it took advantage of the subject's much-increased ability to image; and that it was certainly more entertaining, or at least less productive of boredom and irritation.

In another experiment, the subject would be asked to "get into the head of" (or "identify with") some historical or contemporary per-sonage concerning whom the guide, it was believed, had much more knowledge and "inside information" than did the subject. The subject was told to "incarnate" himself in that person, to "be" that person and think and behave accordingly.

In some of these cases the results were remarkable, the subject changing his voice, way of speaking, posture and even, it seemed, his appearance and way of thinking. The subject would not, however, lose his awareness of his own identity. He would, rather, "be two people," and would talk about his "new" and "second self" vvith a plausibility that sometimes verged on the uncanny.

Of such a "test," it must be said that it is never possible for the guide to be certain of the extent of the subject's knowledge of the person with whom he "identifies." Asking the subject to "get into" a person totally unknown to him is not productive. At the very least, however, this game has elicited some outstanding performances from persons not previously aware of any acting ability. Some of the per-formances also would necessitate the subject's calling upon reservoirs of inforrnation, or memories, not consciously in his possession. Further, there seems to be demonstrated here a heightened capacity for empathy.

Instant Love and Galloping Agape. Twentieth-century man in the Western World has come to be almost obsessively concerned with the difficulties of the interpersonal relationship and with the "necessity" for tearing down the walls that separate one human individual from an-other. Confronted by the possibilities of nuclear self-destruction, an imminent population crisis and the emergence of Red-Fascist and other tyrannies, we seek ever more frantically after means by which men and nations may be able to coexist in harmony. With the contemporary supremacy of physics over metaphysics, the most urgent need of man seems no longer to be to find the meaning of his place in the cosmic scheme of things. Defining his position vis a vis God has ceased to be man's central quest. Instead, with mounting despair and desperation, he attempts to define and improve his position vis a vis the Other Per-son»)

Such intricate analyses of the interpersonal relationship as Buber's I and Thou and Sartre's Being and Nothingness reflect Western man's concern and also serve to deepen and complicate the problem even while shedding some light upon it. Psychoanalytic, phenomenological, and other psychologies produce, even as they instruct us, a sense of confusion and frustration in the face of the revealed complexities of the human psyche. Man's isolation, opaqueness, estrangement, and the con-sequent imperfections of communication with and knowledge of other minds emerges as the most pressing and seemingly insoluble problem he confronts.