Nine: Religious and Mystical Experience

| Books - The Varieties of Psychedelic Experience |

Drug Abuse

Nine: Religious and Mystical Experience

One of the most important questions raised by the psychedelic drugs is whether authentic religious and mystical experiences occur among the drug subjects. To this question the answer must be Yes—but we feel an extended discussion is warranted and that many qualifications are in order.

In our experience, the most profound and transforming psychedelic experiences have been those regarded by the subjects as religious. And in depth of feeling, sense of revelation, semantically, and in terms of reorientation of the person the psychedelic religious and religious-type experiences certainly seem to show significant parallels with the more orthodox religious experiences. These parallels alone would be sufficient to demand extensive and careful study.

Undoubtedly it would be the supreme irony of the history of religion should it be proved that the ordinary person could by the swallowing of a pill attain to those states of exhalted consciousness a lifetime of spiritual exercises rarely brings to the most ardent and adept seeker of mystical enlightenment. Considering the present rapid assimilation on a mass cultural level of new discoveries, therapies, and ideologies, it then might not be long before the vested religious interests would finally have to close up shop. And no less renowned a prophet than the late Aldous Huxley has suggested that humanity at large may in fact come to avail itself of psychedelic drugs as a surrogate for religion.

Since his statement appeared in 1954, the controversy has raged between those like Huxley, Gerald Heard, and Alan Watts who believe that in these chemicals the evolutionary acceleration of man's spiritual nature is now at hand, and other writers such as R.C. Zaehner who contend that these drugs at the most produce a very minor sort of nature mysticism and moreover tend to vitiate higher forms of religious and mystic expectations.'

Before considering this debate in the light of our own findings, it should be of value to examine briefly something of the history of artifi-cially induced states of mystical and religious consciousness. We do this in order to demonstrate to the reader the unbroken line of continuity in the history of "provoked mysticism."

Since the time when man first discovered that he was a thinking organism in a manifold world, he has sought to marshal his analytic capacity to control the manifold and discover its natural laws. As a parallel movement to this analytic process there developed as an under-current another way of knowing—one that sought to discover man's essential nature and his true relationship to the creative forces behind the universe, and to discern where his fulfillment lay. For the sake of achieving this integral knowledge men have willingly submitted them-selves to elaborate ascetic procedures and have trained for years to laboriously master Yoga and meditation techniques. They have prac-ticed fasting, flagellation, and sensory deprivation, and, in so doing, may have attained to states of heightened mystical consciousness, but also have succeeded in altering their body chemistry. Recent physiologi-cal investigations of these practices in a laboratory setting tend to con-firm the notion that provoked alterations in body chemistry and body rhythm are in no small way responsible for the dramatic changes in consciousness attendant upon these practices. The askesis or ascetic discipline of fasting,2 for example, makes for vitamin and sugar defi-ciencies which acts to lower the efficiency of what Huxley calls the cerebral reducing valve.3

Similarly, the practice of flagellation will tend to release quantities of histamine, adrenalin, and the toxic decomposition products of protein—all of which work to induce shock and hallucination. With regard to sensory deprivation, the work of D.O. Hebb at McGill Uni-versity in Canada and that of John Lilly at the National Institutes of Health in Washington demonstrates on the laboratory level how the elimination of external sensory stimuli can result in the subjective pro-duction of fantastic visionary experiences similar to those reported by St. Anthony during his vigil in the desert or the cave-dwelling Tibetan and Indian hermits who live out great segments of their lives in com-plete isolation. Other techniques of "provoked mysticism" include breathing exercises rhythmically performed to alter the composition of the blood and provide a point of concentration, extended chanting (which increases the carbon dioxide content of the blood), hypnosis, prayer dancing (employing body oscillations which induce trance and presumed physical changes), the spinning frenzy of the whirling der-vishes, and so on.

'The most comprehensive and consciously controlled system of dis-ciplines is, of course, the Hatha Yoga which incorporates the practices of posture regulation, breathing exercises, and meditation. Its immedi-ate aim is to bring under conscious control all physiological processes, so that the body can function with maximum efficiency. Its ultimate aim is to arouse what is called kundalini, a universal vital energy which is supposed to gain its access to the body at the base of the spine. When aroused and controlled, it is said to activate the psychic centers and thus make available to the yogi unusual powers. It is claimed that if this energy can be directed to the head center (the thousand-petalled lotus), a mystical state is attained and the yogi becomes aware of a mystical unitive consciousness. To this end the early Sanskrit psychophysical researchers developed a remarkable knowledge of physiological pro-cesses and their relation to body control.

Thirty years ago, in a volume entitled Poisons Sacrés, Ivresses Di-vines, Philippe de Felice provided considerable documentation to sup-port the ages-old connection between the occurrence of religious-type experiences and the eating of certain vegetable substances. He wrote that the employment of these substances for religious purposes is so extraordinarily widespread as to be "observed in every region of the earth among primitives no less than among those who have reached a high pitch of civilization. We are therefore dealing not with exceptional facts, which might justifiably be overlooked, but with a general and, in the widest sense of the word, a human phenomenon, the kind of phe-nomenon which cannot be disregarded by anyone who is trying to dis-cover what religion is and what are the deep needs which it must satisfy.4

De Felice advanced the thesis that one of the earliest known of the substances, the soma of the Vedic hymns, may have been indirectly responsible for the development of Hatha Yoga. 'The soma appears to have been some kind of creeping plant which the Aryan invaders brought down with them from Central Asia about 1500 s.c. 'The plant occupied an integral position in the myth and ritual structure of Vedic religion, was regarded as divinity, and was itself ritually consumed to bring the worshiper to a state of divine exhilaration and incarnation. "We have drunk soma and become immortal," hymns the early Vedic author. "We have attained the light, the gods discovered." According to de Felice, as the Aryans moved deeper into India the gods proved more difficult to find as the soma plant, like fine wine, would not travel. The exercises of the Hatha Yoga school, he suggests, may have been created as an attempt to fill the "somatic" gap and achieve that physiological state of being conducive to religious states of consciousness similar to those brought on by the ingestion of the sacred food. 'The larger impli-cation of this thesis is that vegetable-provoked mysticism exists as a state prior to askesis-provoked mysticism—that early man may have come upon his first instances of consciousness change through his ran-dom eating of herbs and vegetables. Certainly this thesis can never move beyond the realm of conjecture, although the fact remains that naturally occurring mind-changing substances are found the world over and are much more likely to have been experimented with before the creation of any system of mind-changing exercises.5

For millennia man has been involved in the ritual ingestion of sub-stances reputed to produce an awareness of a sacramental reality and has come to incorporate these substances into the myth and ritual pat-tern of the culture in which they occur. The words haoma, soma, peyote, and teontmacatl, all of which refer to God's flesh, are significant semantic referrents to the religious experiences believed to be inherent in the sacred foods.

One of the major archaeological discoveries of recent years has been the digging up on the Guatemalan highlands of a great many stone figures representing mushrooms out of whose stem emerges the head of a god. Thus the mushroom appears to have been hypostatized as deity as early as 1500 s.c. These figures occur as Aztec artifacts as late as the ninth century A.D. However, the earlier figures are technically and stylistically of finer craftmanship, indicating a flourishing cult in the early pre-classical period. By the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries of our era reports of such a mushroom cult occur in the writings of Span-ish explorers and priests. They naturally regarded these rites as demonically derived celebrations and soon made certain that they were driven underground. 'The rites, as noted, continue to survive today among the Mazatec Indians of southem Mexico where the ancient liturgy and ritual ingestion is still performed in remote huts before tiny con-gregations.

In recent years the cult has been subject to a great deal of publicity owing chiefly to the efforts of that well-known mycophile R. Gordon Wasson. In thirty years of search for the secret of the mushroom throughout the world, he and his wife believed that they uncovered the mystery among the Mazatec communicants. 'They persuaded a curan-dera or cult shaman to allow them to participate in the ceremony and swallow the sacred food. Recalling his experience, Wasson wrote that "as your body lies in the darkness, heavy as lead, your spirit seems to soar and leave the hut, and with the speed of thought to travel where it listeth, in time and space, accompanied by the shaman's singing and by the ejaculations of her percussive chant. What you are seeing and what you are he,aring takes on the modalities of music, the music of the spheres . . . as your body lies there . . . your soul is free, loses all sense of time, alert as it never was before, living eternity in a night, seeing infinity in a grain of sand. What you have seen and heard is cut as with a burin in your memory, never to be effaced. At last you know what the ineffable is, and what ecstacy means."

In a monumental study of the mushroom, Mushrooms, Russia, and History, the Wassons claimed to discover its sacramental usages in cultures widely distributed from the Levant to China; and they state that it even was known to the Norsemen of the Icelandic culture? In addition to the Mexican cult, the rite continues today among certain shamanistic tribes in Siberia, the ritual object of the cult being the hallucinogenic mushroom Amanita muscaria. Because this variety of mushroom occurs widely throughout Europe, Wasson has advanced the hypothesis that it might provide an answer to the secret of the Elusinian mysteries. From certain Greek writings and from a Pompeian fresco there are indications that the initiate drank a potion and then, in the depths of the night, beheld a great vision. Aristides, in the second century A.D., speaks of the ineffable visions and the awesome and luminous experience of the initiates.8 Wasson finds significance in the fact that the Greeks frequently referred to mushrooms as the "food of the gods," broma theon, and that Porphyrius is quoted as having called them "nurslings of the gods," theotrophos.8

However interesting is the notion of a mushroom-inspired Hellenic mystery, we suspect that Wasson's mycophiliac zeal exceeds his academic rigor when he suggests that Plato came upon his theory of an ideal world of archetypes after having spent a night at the temple of Eleusis drinking a mushroom potion.

The history of transcendental experience bears testimony to the thin line that often separates the sublime from the demonic, and to the frequency with which the one may cross over into the other. In demonic terms the visionary foods were extensively used, for example, by vvitches, especially during the period 1450 to 1750. As remarked, the witches drank and rubbed on their bodies concoctions the principal ingredients of which were the Solanaceae drugs contained in such plants as the thorn apple, mandragora, deadly nightshade, the henbanes, and others. The drug concoctions were employed at the Sabbats to produce hallucinations and disorientation, and also were taken at home for the purpose of inducing dreams and imagery of flying, orgiastic revels, and intercourse with incubi. So vivid were the nightmares and hallucinations produced by these drugs that witches frequently confessed to crimes they had only dreamed about but thought they had committed in the flesh.

The peyote ceremonies of the Native Arnerican Church have re-ceived sufficient treatment elsewhere in this book.

The historic sacrality of the visionary vegetables has since given way to the modern notoriety of the synthetic derivatives—especially, LSD, psilocybin, and mescaline. With regard to religious experiences as othervvise, one confronts these contemporary compounds with a host of puzzling questions. How, for example, may one reconcile the extremes of enthusiasm on the part of those who claim to find in these drugs a near-panacea for all ills and the key to mystical illumination with the vehement antagonism of those who are convinced that at best the drug-state mimics schizophrenia while at worst the drugs may wreak irre-parable havoc with the psyche and possibly also irreparably damage the brain? Again the whole question arises as to whether these substances are consciousness-expanders or merely mind-distorters? In Savage's well-known phrase, do they provide "Instant Grace, Instant Insanity, or Instant Analysis?"" Finally, there is the tragic-comic denouement that these altercations have won for the drugs a pariah mystique. The prob-lem with such a mystique is, of course, that it dictates that the pariah must go underground and there fester in cultic movements.

The contemporary quest for the artificial induction of religious ex-periences through the use of psycho-chemicals became a controversial issue with the publication of Huxley's Doors of Perception in 1954. In that book Huxley with his usual genius for the quixotic offered the suggestion that visionary vegetables in their modem synthetic forms could provide a new spiritual stimulation for the masses: one that was surer than church-going and safer than alcohol» The actual experi-mental testing of the claims for the psycho-chemical-as-religious-surrogate occurred in 1962 on an occasion now known as "The Miracle of Marsh Chapel." As a part of his work on a Harvard University doctoral dissertation in the Philosophy of Religion, Dr. Walter Pahnke, an M.D., set out to test a typology of mysticism based on the categories of mystical experience summarized by W.T. Stace in his classic study of the subject.12 Pahnke designed his experiment to test this typology on subjects who were given psilocybin in a religious setting. The subjects in question were twenty theology students who had never had the drug before and ten guides with considerable psychedelic experience. 'The theology students were divided into five groups of four persons, with two guides assigned to each group. After a preparatory gathering the groups moved upstairs to the chapel and the three-hour Good Friday service that awaited them. It was on this occasion that two of the subjects in each group and one of the two guides were given 30 micro-grams of psilocybin, a fairly strong dose of that drug. The effects of psilocybin are very similar to those of LSD. The second guide and the two remaining subjects received a placebo containing nicotinic ingredi-ents which provided the subject with a tingling sensation but produced no psychedelic effects. The drug was given in a triple-blind frameworlc, meaning that neither subjects, guides, nor the experimenter knew which ten were getting the psilocybin and which ten were members of the control group and received placebos. The Good Friday sermon was preached and the subjects were left in the chapel to listen to organ music and to await whatever experiences they were to have.

What subsequently occurred has been described as "bizarre," "out-rageous," and "deeply inspiring." As Pahnke's dissertation has not yet been published, we will not to be able to describe at this time the events that transpired in the chapel. However, it is permissible to say that nine subjects from the psilocybin group reported having religious experiences which they considered to be genuine while one of the subjects who had been given a placebo also claimed to have experienced phenomena of a religious nature. Typical of the responses was this excerpt from a report written shortly after the experiment by one of the subjects: "I felt a deep union with God. . . . I carried my Bible to the altar and tried to preach. The only words I mumbled were peace, peace, peace. I felt I was communicating beyond words."

In order to provide some material for a meaningful critique of this experiment the subjects' reports were read by three college-graduate housewives who were not informed as to the nature and background of the reports, but were asked to assign to each a rating of strong, moder-ate, slight, or none, according to which of these terms best applied to a subject's statement in the light of each of the nine elements of mystical experience listed in the mystical typology provided by Pahnke. Accord-ing to Pahnke, the statistical results of these ratings indicated that "those subjects who received psilocybin experienced phenomena which were indistinguishable from if not identical with . . . the categories defined by our typology of mysticism."

Various other studies would seem to attest to the mystico-religious efficacy of the psychedelic drugs. For example, in an attempt to explore the "revelatory potentialities of the human nervous system," Dr. Timothy Leary and his associates arranged for 69 full-time religious professionals to take psilocybin in a supportive setting. Leary has sub-sequently reported that over seventy-five percent of these subjects stated after their sessions that they had experienced "intense mystico-religious reactions, and considerably more than half claim that they have had the deepest spiritual experience of their life.""

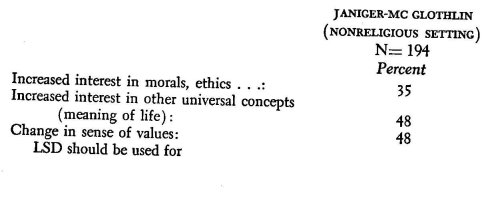

In another study by two Californians, a psychiatrist and a psycholo-gist respectively, Oscar Janiger and William McGlothlin reported on a study involving 194 LSD subjects (121 volunteers and 73 as part of a program in psychotherapy). 'The drug was given in a nonreligious set-ting so that presumably religious expectations did not influence the subjects as was the case with the Leary experiment. Below is a statisti-cal abstract of their findings, based on a questionnaire answered by the subjects ten months after their sessions:

It also should be added that ten months after having taken the drug twenty-four percent of the 194 subjects still spoke of their experiences as having been "religious."15

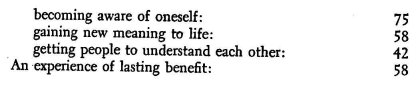

Two other similar studies should be mentioned because of the re-markable percentages reported with regard to the subjects' feeling that they had had a religious-type experience. Both experiments were con-ducted by psychiatrists but whereas one provided a supportive environ-ment for the session, the other not only was supportive but also was structured in part to provide the subject with religious stimuli. This second precedure resulted in significantly higher percentages of subjects reporting religious experiences."

Taken altogether these findings must be regarded as remarkable. In the five studies just cited between thirty-two and seventy-five percent of psychedelic subjects will report religious-type experiences if the setting is supportive; and in a setting providing religious stimuli, from seventy-five to ninety percent report experiences of a religious or even mystical nature.

'The reader is surely by this time wondering what to make of the claims of these researchers. Are they psychedelic Svengalis employing suggestion to play upon the sensitized psyches of their hypersuggestible subjects, imposing whatever delusions they might need or wish to im-pose? Or may it be that they themselves are deluded and fail to under-stand that in present-day America a man or woman will put a check next to "had a religious experience" if a drug has helped him or her to feel in some impressive way "different" than usual? There can be no doubt that the psychedelic drugs give the subject experiences very "dif-ferent" from any the average person is likely to have had. For the most part the drug-state resembles neither the effects to be gotten from alco-hol nor those resulting from amphetamines and tranquilizers. Does the present-day subject, then, having little or no familiarity with what is meant by the terms "religious" and "mystical" (other than something undefinedly exciting), adopt these words by default to describe the novel phenomena he has encountered during his session (and finds conveniently present on the questionnaire)? 'The Eastern scholar R.C. Zaehner offers a sophisticated version of this argument in his book attacking Huldey's position, Mysticism, Sacred and Profane. In this work Zaehner presents a closely reasoned and scholarly look at the classical records of religious and mystical experience and concludes that drug-induced mysticism falls so far short of the experiences of saints and holy men that a subject is badly misleading himself if he feels that he has undergone an authentic religious experience. "Preternatural" experience, the experience of transcendence and union with that which is apprehended as lying beyond the multiplicity of the world, is very common experience indeed, Zaehner argues. Not only is it common to nature mystics, but it recurs regularly with poets, monists, manic-depressives, and schizophrenics. Whether one is dealing with the "cos-mic emotion" of the nature mystic, the "almost hysterical expression of superhuman ecstasy" found in a poet like Rimbaud, the bliss of subject-object dissolution, or the rapture of psychologically dissociated states, one is dealing exclusively with "preternatural" phenomena and not with authentic religious or mystical experience. Zaehner deems all psy-chedelic drug experience, be it madness, monism, or nature mysticism, to lie entirely within the province of such preternatural experience.

The further implication of Zaehner's thesis is that these drugs can never induce theistic states of religious and mystical experience which he regards as the supreme and authentic religious experience. The other tvvo forms of mystic,a1 experience which Zaehner recognizes, nature mysticism in which the soul is united with the natural world and monis-tic mysticism in which the soul dissolves into an impersonal Absolute, are infinitely inferior states of religious awareness as compared to theistic mysticism in which the soul confronts the living, personal God.

Here Zaehner's position is clearly open to criticism. Apart from questioning the value hierarchy which Zaehner ascribes to the three kinds of mysticism, one might take him to task for suppressing the evidence for drug-induced theistic mysticism. As is well known, the peyote rituals of the Native American Church are frequently productive of theistic religious experiences. James Slotkin, an anthropologist, has noted that the Indians during these ceremonials "see visions, which may be of Christ Himself. Sometimes they hear the voice of the Great Spirit. Sometimes they become aware of the presence of God and of those personal shortcomings which must be corrected if they are to do His

(Slotkin, it should be added, had observed the Indians' rites and been a participant in them.) And, in any case, the phenomenon of specifically theistic versions of psychedelic mysticism is an ancient and widespread tradition.

Needless to say, Zaehner's arguments have provided ammunition for many theologians and churchmen who refer to religious experiences induced with the help of psychedelic drugs as "chemical religion," "cheap and lazy religion," "instant mysticism," etc., and who charge that the use of the drugs for such a purpose amounts to "irreverently storming the gates of heaven." However, there is no avoiding the fact that Zaehner's critique has the ring of an eleventh hour tour de force. One philosopher sympathetic to the use of the drugs for religious purposes says that "Zaehner's refusal to admit that drugs can induce expe-riences descriptively indistinguishable from those which are spontane-ously religious is the current counterpart of the seventeenth-century theologians' refusal to look through Galileo's telescope or, when they did, their persistence in dismissing what they saw as machinations of the devil. . . . When the fact that drugs can trigger religious experiences becomes incontrovertible, discussion will move to the more difficult question of how this new fact is to be interpreted.'"

In our own experience, the evidence would seem to support the contentions of those who assert that an authentic religious ex-perience may occur within the context of the psychedelic drug-state. However, we are certainly less exuberant than some other researchers when it comes to the question of the frequency of such experiences. It is not here a question of our having had fewer subjects who claim to have had a religious experience—over forty-five percent have made this claim; rather, because of the criteria employed, a large number of these claims have been rejected by us. The difference therefore is one of criteria rather than of testimonial opulence.

In our attempt to develop unbiased criteria for the authentic reli-gious experience we have employed the usual measuring devices; how-ever, we have also found it important to place some emphasis on what we have termed the "depth level" of the experience. The literature of nondrug religious and mystical experience appears to lend considerable support to this criterion. It is significant to note, for example, that in this traditional literature the writers repeatedly deal with and emphasize the stages on the way to mystical enlightenment and describe these with metaphors suggesting striking analogies to the psychodynamic levels hypothesized in our psychedelic research. Again and again, the literature reveals comparable gradations or levels of experience as the mystic moves from acute bodily sensations and sensory enhancement to a heightened understanding of his own psychodynamic processes, through a stage inhabited by visionary and symbolic structures, until at last he achieves the very depths of his being and the luminous vision of the One. This level is described as the source and the ground of the self's unfolding and represents the level of confrontation with Ultimate Reality. The most important of the experiences reported by William James in The Varieties of Religious Experience are of this type in which the person seems to be encountered on the most profound level of his being by the Ground of Being. Religious experience can be defined, then, as that experience which occurs when the "depths of one's being" are touched or confronted by the "Depth of Being." Mystical experience differs from this in degree, not in kind. This latter occurs when one's personal depths dissolve into the "transpersonal" depths—when one is unified at one's deepest level with the source level of reality.

Mystics and religious personalities have repeatedly warned against accepting states of sensory and psychological alteration or visionary phenomena as identical with the depths of the spiritual consciousness. These warnings go unheeded today by many investigators of the psy-chedelic experience who seem to accept the subject's experiences of heightened empathy and increased sensory awareness as proofs of reli-gious enlightenment. Doubtless some of these experiences are analogous in some way to religious and mystical experiences. But religious ana-logues are still not religious experiences. At best they are but stages on the way to religious experiences. And a major problem in this research to date is that it has been conducted by persons unfamiliar with the nature and content of the religious experience. Thus claims are made that can be misleading.

For example, a subject may have a euphoria-inducing experience of empathy with a chair, a painting, a person, or a shoe. This may result in protestations of transcendental delight as chair, painting, person, and shoe are raised to platonic forms and the subject assumes himself to be mystically enlightened. Too often in these and similar situations the guide will offer reassurance to the subject and so reinforce his belief that he is having a religious experience. But by doing this, the guide may prevent the subject from descending to a deeper level of his being where a genuinely religious and transformative experience then might be had.

Given this type of misunderstanding, it is no wonder that the psy-chedelic drugs have resulted in a proliferation of "fun" mystics and armchair pilgrims who loudly claim mystical mandates for experiences that are basically nothing more than routine instances of consciousness alteration. The mandate being falsely and shallowly derived, the sub-sequent spiritual hubris can be horrendous, the subject announcing to whoever will listen that all mystic themes, all religious concepts, all meanings, and all mysteries now are accessible and explainable by vir-tue of his "cosmic revelation." It is frequent and funny, if also unfor-tunate, to encounter young members of the Drug Movement who claim to have achieved a personal apotheosis when, in fact, their expe-rience appears to have consisted mainly of depersonalization, dissocia-tion, and similar phenomena. Such individuals seek their beatitude in regular drug-taking, continuing to avoid the fact that their psychedelic "illumination" is not the sign of divine or cosmic approval they suppose it to be, but rather a flight from reality. Euphoria then may ensue as a result of the loss of all sense of responsibility; and this can and often does lead to orgies of spiritual pride and self-indulgence by those who now see themselves as the inheritors of It! In fact, they come to spend several days a week with It! And all mundane concerns, all earthly "games" seem superfluous and are abandoned insofar as circumstances will allow.

'The situation is complicated by the fact that many such persons are caught up in a quasi-Eastern mystique through which they express their disenchantment with the declining Western values and with the prolifer-ating technology, the fear of becoming a machine-man, and the yearn-ing for some vision of wholeness to turn the tide of rampant fragmenta-tion. This vision they pursue by means of a wholesale leap to the East without, however, having gained the stability, maturity, and elasticity needed to assimilate the Eastern values. Few have the spiritual sophisti-cation of a Huxley or have spent as many years of study and training in quest of methods of achieving the spontaneity and integration elabo-rated in the teachings of some schools of Vedanta and Mahayana Bud-dhism. Thus the leap out of the "games" and everyday "roles" of West-ern reality is usually into a nebulous chaos seen as Eastern "truth." It is an added misfortune that the psychedelic drugs may genuinely give some inkling of the complexity of Eastern consciousness, although the vista usually uncovered is no revelation but merely a glimpse—one that would require years of dedicated study before it could be implemented and made effective in day-to-day existence.

To at least some extent the responsibility for this seduction of the innocent must lie with such authors as Huxley, Alan Watts, and others who in their various writings imposed upon the psychedelic experience essentially Eastern ideas and terminology which a great many persons then assumed to be the sole and accurate way of approaching and interpreting such experience. Armed with such terminology and ide-ation, depersonalization is mistranslated into the Body of Bliss, empa-thy or pseudo-empathy becomes a Mystic Union, and spectacular visual effects are hailed as the Clear Light of the Void."

It should by now be evident why the authors discount as belonging to the class of authentic religious and mystical experience a good many cases in which the data of altered sensory perception and other ordinary drug-state phenomena are hypostatised by the subject as having sacra-mental or religious significance. Among our own cases, that of the young woman in the opening chapter who perceived the objects around her in terms of "holy pots" and a "numinous peach" is clearly not an example of religious experience as the rest of her account goes on to make clear. This subject is indulging in a commonplace practice of psychedelic subjects—the describing of various uncommon experiences in terms of sacramental metaphors.

This is not to suggest that religious insight and religious-type expe-rience never occur in combination with an experience of sensory en-hancement. The interpretation accompanying the perception may result in revelatory insights. A famous case in point is the divinity school professor contemplating a rose: "As I looked at the rose it began to glow," he said, "and suddenly I felt I understood the rose. A few days later when I read the Biblical account of Moses and the burning bush it suddenly made sense to me." Thus within the framework of the psychedelic experience one man's glowing rose can be another man's epiphany.

Analogues of the Religious Experience. The sensory, ideational and symbolic analogues of religious experience are not religious experience; but, at the same time, these may be productive of insights enabling the subject to live more easily and fruitfully than he was able to do before. In order to illustrate this point, we will reproduce here a description by a subject of an experience of extended sensory awareness bordering on nature mysticism and verbalized by the subject mainly in religious terrils. Although the subject was at the time indifferent to religion, she found it necessary to make use of metaphors drawn from the religious vocabulary in order to formulate and communicate her responses.

The subject, S-1 (LSD), a housewife in her early thirties, was taken by the guide for a walk in the little forest that lay just beyond her house. The follovving is her account of this occasion:

"I felt I was there with God on the day of the Creation. Everything was so fresh and new. Every plant and tree and fern and bush had its own particular holiness. As I walked along the ground the smells of nature rose to greet me—sweeter and more sacred than any incense. Around me bees hummed and birds sang and crickets chirped a ravish-ing hymn to Creation. Between the trees I could see the sun sending down rays of warming benediction upon this Eden, this forest paradise. I continued to wander through this wood in a state of puzzled rapture, wondering how it could have been that I lived only a few steps from this place, walked in it several times a week, and yet had never really seen it before. I remembered having read in college Frazer's Golden Bough in which one read of the sacred forests of the ancients. Here, just outside my door was such a forest and I swore I would never be blind to its enchantment again."

The subject remained true to her vow and as of two years after the session continued to experience not only heightened sensory apprecia-tion but also a kind of awe and reverence whenever she walked through her "Holy Wood." 'Thus, although the subject cannot be said to have had a religious experience in the forest, she unquestionably had an experience of the sensory transfiguration of a part of her everyday world so profound that she found it necessary to use the vocabulary of the religious life to describe her experience. Further, although S considered herself to be basically agnostic, her experience in the forest caused her to feel in herself an awakening to dimensions of reality to which she previously had been indifferent. Subsequent to the session she continued to remark in herself a growing interest in "spiritual matters," as she describes:

"Since that day I have had brewing in me a sense of the relevance of that forest for the other areas of my life and the life of my family. For I have come to realize that my way of seeing and hearing and smelling the forest in a way that was greater than any way I had ever seen and heard and smelled before was not because the forest was in any special way 'different' or even more 'sacred' than the rest of the world but because the rest of the world (and this includes myself and my children) was perceived by me with the eye of ordinary expectation. With this expec-tation life becomes just something that somehow you muddle through with no thought or hope of it ever being anything else. But that forest proved me wrong. I saw there and I knew then that there were dimen-sions to life and harmonies and deeps which had been for me unseen, unheard, and untapped. Now that I know that they are there, now that I have awakened to the glorious complexity of it all I shall seek, and perhaps some day, I shall find."

It is interesting to compare this subject's account of discovering unsuspected dimensions of life with the classic account of William James in which the great psychologist similarly evaluates his nitrous oxide experience in terms of a revelation of the levels of existence:

"One conclusion was forced upon my mind at that time, and my impression of its truth has ever since remained unshaken. It is that our normal waking consciousness, rational consciousness as we call it, is but one special type of consciousness, whilst all about it, parted from it by the filmiest of screens, there lie potential forms of consciousness entirely different. We may go through life without suspecting their exist-ence; but apply the requisite stimulus, and at a touch they are there in all their completeness, definite types of mentality which probably somewhere have their field of application and adaptation. No account of the universe in its totality can be final which leaves these other forms of consciousness quite disregarded. How to regard them is the question —for they are discontinuous with ordinary consciousness. Yet they may determine attitudes though they cannot furnish formulas, and open a region though they fail to give a map. At any rate, they forbid a prema-ture closing of our accounts with reality. Looking back on my own experiences, they all converge toward a kind of insight to which I cannot help ascribing some metaphysical significance.""

As noted, there are various odd and pathologicomimetic states of mind which seem to be especially productive of unfounded claims of religious and mystical experience. Depersonalization and empathy, for instance, can cause an ordinarily secular-minded subject to sound like a garrulous Hindu sage who has been transplanted into Southern Cali-fornia. It is not infrequent to hear these psychedelic Swamis intoning such "wisdom" as:

"The not-self of me yields to the Void of Becoming."

"You and I are One. One and God is All."

"We are Mind-ed by God and Self-ed by each other."

"My Isness is of God. My Supposed-to-be-ness is of Man."

Of course not all experience which falls short of being authentic religious experience is on so sophomoric a level. And some actually superficial experiences may sound quite authentic when taken out of their context in the session. Such is the following example which in-volves the not-too-rare psychedelic experience of feeling that one has been raised to a transcendental plateau from which it is possible to look down upon one's own mental processes in Olympian fashion and as if with the "eye of God." This Olympian perspective then leads not infre-quently to religious or pseudo-religious phenomena.

S-2, a thirty-four-year-old sociologist (LSD), writes (with initial reference to his eidetic imagery) :

"The surface of my mind, upon which I—evolved to a supercon-sciousness—looked downward, was revealed as a vast illuminated screen of dimensions impossible to calculate. I observed the myriad multiform ideas and images passing across it; and sensations and emo-tions, flowing inward and outward—whatever occurred within the psyche; perhaps, within the still larger, more complex totality of the self.

"From above, with absolute concentration, observing and sustaining all of this, I was—directing everything, controlling the internal events as one might control the carefully preconceived flights of innumerable air-craft, keeping each on course, preventing all miscalculations and wan-derings that might lead to missed objectives and collisions and needless expenditures of energy.

"The light that illumined these images grew brighter and brighter until I was almost frightened by the intensity of the brilliance. I saw that perfect genius would require the perpetuation of the capacity so, from above, to visualize and direct and regulate. Perfect genius would be an unwavering perfect control of the positions and velocities of ideas and images, instantaneous pre-arranged channeling of impressions—all the internal events, from conception, held in view and directed.

"But then, in a flash of illumination, I understood that this perfect genius of which I conceived was nothing more than a minute and miser-able microcosm, containing but the barest hint of the infinitely more complex and enormously vast macrocosmic Mind of God. I knew that for all its wondrous precision this man-mind even in ultimate fulfillment of all its potentials could never be more than the feeblest reflection of the God-Mind in the image of which the man-mind had been so miracu-lously created.

"I was filled with awe of God as my Creator, and then with love for God as the One Who sustained me even, as in my images, I seemed to sustain the contents of my own mind. It seemed to me that I stood in relation to the whole of the universe in somewhat the same relation as the universe, itself no more than a greater microcosm, stood to the Macrocosm that is God.

"Thus recognizing my own total insignificance, I marveled all the more at the feeling I now had that somehow the attention of God was focused upon me and that I was now receiving enlightenment from Him. Tears came into my eyes and I opened them upon a room in which it seemed to me that each object had somehow been touched by God's sublime Presence."

Read as here presented in the foregoing quotation this description might appear to be the report of a major revelation—an authentic religious experience. However, in the context of S's entire session, it loses most of its impact and importance and must be seen as no more significant than some other and not at all religious experiences of this subject. S was not changed in any important way by the "enlighten-ment" he said he had received, and a few days after the session S himself had relegated it to his personal stockpile of "interesting episodes."

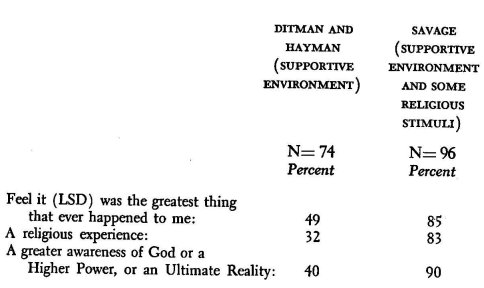

Symbolic Analogues. Since religious and other phenomena of the sym, bolic level have been discussed in the preceding chapter, we will con-sider here only a single aspect of symbolic analogues to religious experi-ence—the eidetic images of an apparently religious nature experienced by almost all subjects. If taken uncritically, these images would seem to provide prima facie evidence of religious experiential content. However, the larger part of this imagery occurs without accompanying religious emotion, and we must conclude that it is a phenomenal curiosity of the drug-state and does not establish or portend any activation of religious or mystical states of consciousness. The following is a statistical break-down of the kind and frequency of "religious" images as they have occurred among our drug subjects:

* To the nearest percentage.

Certain comments should be made with regard to these statistics. Of the four percent of the subjects who did not report any religious imagery at all, these persons were, with two exceptions, completely imageless or imaged only geometric forms. This would seem to indicate that if a subject is able to image at all, then some kind of "religious" imagery is almost certain to occur as a part of the total eidetic image content.

The preponderance of imagery relating to religious architecture reflects not so much a religious interest as an aesthetic appreciation of this generally most imposing and interesting of all architecture.

We will also note that some aspects of these statistics are more than slightly enigmatic. Why, for example, do ancient and primitive rites occur in the images so much more often than do the contemporary ones? Is it because the old rites reflect and minister to deep-rooted human needs that the modern rites do not, or is there some other explanation? Why do angels run such a poor second to devils? Here, it would seem that the devils and demons may be personifications of nega-tive components within the psyche. Sigmund Freud, for one, undoubtedly would have remarked with great interest this apparent preponder-ance of negative over positive personifications of unconscious elements.

Another phenomenon of considerable interest is the fact that mandala (symbolic geometric diagram) imagery scores only eight per-centage points less than imagery pertaining to traditional religious sym-bols. In this statistic one may be encountering evidence of the radical individuating tendency of the psychedelic process. The mandala is, after all, a highly personal symbolic form; in fact, the symbolic condensation of the thematics and dynamics of the person's own nature. It is the coded formula of the subject's personal mythos. The significant per-centage of mandala imagery then may be testimony to one of the key phenomena of the psychedelic experience: the discovery and creative utilization of personal patterns of being against the backdrop of univer-sal structures and sanctions.

The Integral Level. When we examine those psychedelic experiences which seem to be authentically religious, we find that during the session the subject has been able to reach the deep integral level wherein lies the possibility of confrontation with a Presence variously described as God, Spirit, Ground of Being, Mysterium, Noumenon, Essence, and Ultimate or Fundamental Reality. In this confrontation there no longer is any question of surrogate sacrality. 'The experience is one of direct and unmediated encounter with the source level of reality, felt as Holy, Awful, Ultimate, and Ineffable. Whether this Presence resides forever immanent in the integral realm of man's being or whether this realm provides the Place of Encounter between man and Presence remains a meta-question requiring no answer. The important thing is that the encounter does take place—in an atmosphere charged with the most intense affect. This affect rises to a kind of emotional crescendo climaxed by the death and purgation of some part of the subject's being and his rebirth into a new and higher order of existence. Specifically, the subject tends to feel that his encounter with Being has in some way led to the erasure of behavioral patterns blocking his development, and at the same time provides him with a new orientation complete with in-sight and energy sufficient to effect a dramatic and positive self-trans-formation.

Our major criteria for establishing the validity of these most pro-found religious and mystical experiences are three: Encounter with the Other on the integral level; transformation of the self; and, in most cases, a process of phenomenological progression through the sensory, recollective-analytic and symbolic levels before passing into the integral. In the case of these authentic experiences this progression has been at the same time a rich and varied exploration of the contents of these levels providing a cumulative expansion of insight and association until, at the threshold of the integral, the subject has experienced a compre-hensive familiarity with the complex network of his being such as he had never known before. This process is greatly intensified and ap-proaches culmination during the subject's passage through the symbolic level.

Comparative studies in the history of religion demonstrate the tendency in the life of a given religion or culture for the myth and ritual complex to exist as a stage prior to the development of the individuated religious or mystical quest. Indeed, it is a matter of cultural and psycho-logical necessity that the myth and ritual pattern should dominate and precede the emergence of the mystic way for the one serves a more comprehensive role in the organic ordering and revitalizing of society and psyche, while the other involves a movement away from the social complex to a region of radical individuation.

It is significant then that in the levels of phenomenological progression revealed in the psychedelic experience, the symbolic realm with its abundance of myth and ritual material is, in most cases, experienced as preceding the level of integral and mystical reality. This relation of the symbolic to the integral will be illustrated in the following case.

The Authentic Religious Experience. In the highly unusual case to follow we present a detailed account of what we consider to be an authentic religious experience. It is also a transforming experience, one that profoundly and beneficially changes the person. The movement is continuous, beginning in the first 'of three psychedelic sessions, and reaching culmination in the third as the subject attains to the integral level. This case should be read as exemplifying better than any other we present the guided progression through the various hypothesized levels toward the climactic, transforming confrontation—here, a confronta-tion with God.

The (LSD) subject, S-3, in his late thirties, is a successful psychol-ogist who has achieved much recognition in his field. Before offering any account of the sessions it will be necessary to discuss the back-ground of the subject at some length. We should add that we have received from thoroughly reliable sources confirmation of many of the strange autobiographical materials first supplied us by the subject.

As we have found to be very often true, in its broad outlines the life of this subject may be seen as the re-enactment of a myth—in this case, the myth of the rebellious angel Lucifer who challenged the power and authority of God Himself and was cast down into Hell as a punish-ment for his pride. One of the most extraordinary elements in this case is the very early "choice" of the particular myth and the thoroughness with which the myth has been acted out in the subject's life.

In considering this case it may prove helpful to keep in mind several key points. S, since earliest childhood, has displayed a high degree of intelligence accompanied by a rich imagination continuously expressed in both his overt behavior and his abundant fantasy life. He has shown a constant tendency to represent his life to himself in terms of symbolic analogues. And he has long regarded the progression and details of his life as "a kind of 'art work,' initiated by a fertile childish imagination and subsequently 'improved upon' by an older imagination armed with immense amounts of esoteric data."

S is the only child of well-to-do Protestant Anglo-Saxon parents with whom his relations are good. As it has been described to him, he came into the world with long silky black hair growing over much of his body. His face at the time of his birth was wizened, he had teeth and resembled a tiny, ancient man. Shortly after his birth he developed pneumonia and "was born with or soon got a bad case of jaundice." His skin was wrinkled and yellow and his relatives thought him an ex-tremely odd-looking baby, "a little old Chinaman," although his mother insisted she thought he was "quite beautiful." S was not expected to survive, but "surprised" his family and the physician "by somehow pulling through."

As a child, S was precociously intelligent, imaginative, and self-reliant. By the time he was four he could read and, at the age five, was reading pulp fantasy and science-fiction magazines as well as the usual children's books. Myths and legends of many lands, along with the works of Poe were read to him or by him. As far back as he is able to remember, S always felt himself to be "alien, not really a member of the human race at all, but someone who belonged someplace else and got into this world by accident or under strange circumstances." However, he soon found it expedient to keep "the secret" of his "difference" to himself and to "make believe" he was "like other children." Or, when unable to deceive himself, he would "consciously pretend" to be "a human child." Whether this began as a game he played with himself, S cannot be certain; but this seems to him a likely explanation.

Also as far back as he can recall, S felt an irresistible attraction toward "what others regarded as evil," although S himself "at no time accepted this value judgment." All through his childhood his "sympa-thies were always with the bad guys" in films, on the radio, etc. In playing with other children he selected games in which he could take the role of the robber or some other villain. His precocity was such that he was easily able to "manipulate most other children" and also, much of the time, the adults around him. Until rather recently he has continued to see his relations with others in terms of their manipulation by him—a manipulation that was usually not a means to some end, but rather was an end-in-itself.

At around age six, S greatly distressed his mother by declaring his disbelief in God. He attended Sunday School under duress and excelled at memorizing passages of Scripture; but, in reading the Bible, he "was always turning to the erotic incidents and to anything that concerned the Devil." His fascination with the Devil was constant throughout his childhood and much of his adult life. At the age of twelve, he made the first of his many "unsuccessful attempts" to sell his soul to the Devil. He found books on demonology and sorcery, studied them, and identi-fied with the demon Ashtaroth. He practiced black magic, "sometimes with apparent success."

At age thirteen, S had his first sexual experience. Thereafter, he was "constantly out after sex." He became exceedingly promiscuous and had remained so up until about one year before his session. He also "read omnivorously about sex," especially prohibited sex practices and aberrations. All of this he did "because society, and especially the church, regarded sex outside of wedlock as evil." Whatever was thought to be "evil," S would do—although he stopped short of activities likely to result in serious trouble with the police. At the same time, S "never did believe that sex was evil." He never experienced any feelings of guilt in connection with his "evil" practices and "probably" never has known what it is to feel consciously guilty. Yet, no one has ever suggested that S is a psychopath. For all his "manipulation" of others, he has fre-quently been of great help to his friends and associates and is regarded by many as a kind, compassionate person.

As he grew older, S became "a real scholar of evil." He searched assiduously for "all the banned books" and read them. In school, his intelligence (I.Q. about 165) permitted him to earn good grades with-out effort and left him time to "stir up lots of mischief." At the univer-sity, he was considered to be an outstanding student. He was drawn to the study of psychology, and especially to psychoanalysis, because his own mental processes seemed to him "mysterious and unlike those of other persons."

Although an atheist with scientific interests, S continued his studies in satanism, witchcraft, "black" occultism, etc. His atheism was militant and for a time he also was a nihilist. His militancy "attracted disciples" and others often remarked that he had "some strange kind of power." He had much sexual success with coeds and "preached a doctrine of total debauchery." However, he preferred his contacts with socially low-level girls and spent much time in "almost skid-row surroundings" that seemed to have a very great fascination for him.

"As a nihilist," S "believed in nothing at all," and "the effect of this" was to cause him to lose the "power" that others always had recognized in him. The "next effect" was a "crippling anxiety neurosis" that came on when S still was in graduate school. He was "just barely able to control" his anxiety to the extent required to let him finish school. Whenever confronted by "a person in any position of authority" over him, S would "inwardly tremble" and felt that at any moment the trembling "would be exteriorized and then degenerate into total panic." Yet, when confronted by such situations, he "somehow always got through." And even when the neurosis was at its worst S remained a forceful personality who "always managed to have a few disciples on the string."

In his practice as a psychotherapist, S was unusually effective. Here, he felt, the "upper hand" was his and consequently the "anxiety prob-lem did not come up." Outside the therapeutic situation, however, S's ‘`neurotic symptoms intensified" until, for a few brief periods of his life, he found himself almost unable to enter a store to make a purchase. If he found himself in a position where he "had to ask anybody for anything," he became extremely agitated and feared he would be unable to speak. This condition, which was intermittent, was at its worst during a period of three to four years. The neurosis "seriously handicapped" S and caused him a great deal of misery for almost a decade.

At age twenty-eight, S embarked upon a lengthy self-analysis that continued for some seven years. His method was eclectic, but mostly psychoanalytic and Freudian. He worked with auto-hypnosis and relax-ation techniques in an effort to suppress his physical symptoms (trem-bling, tachycardia, etc.) while he "attacked the neurosis itself" with his self-analytic method. During the whole duration of the neurosis S con-tinued to be promiscuous, but could only overcome his anxiety with the woman he approached as "suppliant" by drinking very heavily. He felt that this necessity presented the added threat that he would become alcoholic.

About four years previous to his LSD sessions, S "achieved impor-tant breakthroughs" in his self-analysis. He did not "cure" the neurosis but developed techniques "for detecting a symptom at its inception and immediately suppressing it." He felt that the cause of the neurosis no longer was operative, so that the task was really one of breaking down habits and conditioned response patterns. His anxiety, he felt he had learned, was in fact a "rage unable to express itself because known to be an irrational, inappropriate response." This rage occurred whenever S was "in any sense in a subordinate position." Then the rage, which he could not express, "would come to the surface as symptoms" which S initially had "mistaken" for amdety. Later, what he feared was the symptomatic behavior itself, and "then the anxiety became real." After his "breakthroughs" he continued to work at the self-analysis for an-other year, then abandoned it as no longer needed. He continued to be "very promiscuous," but "more out of habit than need."

About one year before his sessions, S had several experiences he felt to be of great importance. He long had recognized religious tendencies in himself but had always suppressed "this need" or "deflected the need towards the Devil." Now, however, he felt that his lifelong preoccupa-tion with the Devil was "juvenile" and made some strenuous efforts to tap "that genuine source of strength and inner peace men call God." S felt that on several occasions he had "broken through to this Source." Each time, after such a breakthrough, he noted "definite gains towards improved adjustment and self-mastery." But he never could manage to subdue his "inner devils, who whispered that all of this was merely hypocrisy and self-delusion."

S then had a curious kind of "mystical experience." His "totem animal" for many years had been the wolf. This wolf, with which S identified, represented "a wild, untameable freedom." The wolf was, like himself, "a solitary beast, self-reliant (and as S wanted to be), strong and snarling his defiance at the world." This personal totem was abandoned when S, reflecting upon his "wolf-identification," suddenly knew beyond all possibility of doubt that the wolf in himself now was dead. In almost the same instant, dosing his eyes, he saw before him a vivid eidetic image of a huge, beautiful tiger and knew with equal conviction that the tiger now was his totem. Following this incident the tiger appeared to S in a succession of dreams. During the dreams S was "somehow made to understand" that the transition from wolf to tiger represented a distinct advance for him and that the neurosis was coming to an end.2' From the moment of this change of totems onward, S continued to make "steady gains" in the form of "a healthier outlook than ever before and better relations with other persons." He continued to "seek God" and the feeling that this was "something to be ashamed of" troubled him much less than before. He felt that for the first time in his life his mental health was "very good, though not perfect," and that the more severe of his problems had been left behind him "once and for all."

Such, very briefly, are the general outlines and some relevant details of this subject's strange background. The infonnation was not available to us previous to his session and, in this subject's case, no amount of interviewing could elicit what he did not want to tell. He was far too practiced and knowledgeable a veteran of dissimulation to reveal either in conversation or testing any information he preferred to withhold. Nor was there, at the time of his first session, any longer any serious dis-turbance to be diagnosed.

The First and Second Sessions. Because S's last two sessions are more important and require rather lengthy summation, we will pass very briefly over the first.

During that first session, S spent several hours experiencing the various phenomena of the sensory level. He adjusted to the drug-state22 quickly and kept up a witty and intelligent running commentary on his images, visual distortions, ideas about "psychodynamic mechanisms" involved in the sensory phenomena, etc. He expressed some desire to examine his own psychology, but produced nothing of much impor-tance. We agreed with S that, at this point, his psyche already was so well explored that he might as well go on to something else.

Some three and one-half hours into the session, S abruptly ceased his brief venture into the recollective-analytic realm and experienced many phenomena characteristic of the symbolic level. He felt the evolu-tionary process in his body and also imaged rudimentary life forms, then observed with much interest the development over the aeons of new and more complicated varieties of plant and animal life. He ob-served dinosaurs in ferocious combat and a series of "abortive hu-manoid forms, failing to develop so as to enable them to survive." He repeatedly observed "very decadent half-human beings" and great twist-ing masses of serpents, writhing in a brilliantly colored mass, "inextric-ably intertwined." He remarked that this latter image often had been seen (eidetically imaged) by him outside of the drug-state, but never so vividly.

The most dramatic moments of this session occurred after some five hours, when S imaged a great ball of fire that exploded in outer space and molten-looking but "immaterial" sheets of flame rained down upon the earth—"a kind of fiery deluge." 'These sheets of flame became a blazing, glowing cylinder that surrounded "the edges of the earth." The cylinder "cooled," became a silvery mist, and then appeared to evapo-rate. "After this," S declared, "the Presence of God was upon the earth" and the attempts of evolution to bring forth man were crowned with success. Henceforth, the "pull of Nature upon man was down-ward." It was as if whatever force had itself failed at creating man, now set itself the task of undoing God's successful creation. Concerning this conflict, S described himself as being "very ambivalent . . . wanting to side with God, but somehow allied with the other force that incessantly strives to tum order into chaos." S felt that this conflict he now de-scribed was basically his own, but "infinitely more complex" than his statement of it would suggest. With great emotion he announced that "this is of vital importance to me" and that he "absolutely must get to the bottom" of what he felt was being disclosed to him about his own nature.

From this point on, the drug effects rapidly diminished and no material of any importance was produced. After the session, S contin-ued to insist very strongly that "something has been started, some process that it is very important I see through." He felt that this could only be accomplished if he had another LSD session.

While only rarely in our work have we found it desirable to give a subject more than one session, in this case we shared the subject's conviction that "something big is in the wind." Since all were agreed that another session was in order, we scheduled the second for the following Saturday, just seven days from the date of the first session. On the occasion of this second session, S declared he would "waste no time with the exotica"—the sensory level phenomena—and almost at once resumed his first-session preoccupation with symbolic level materials. His session from that point on was largely on this symbolic level with, however, frequent and important movements "back up" to the recol-lective-analytic.

Early in the session, S reported feeling his body to be that of a huge, happy dragon lying upon the surface of Mother Earth. He also reported the recurrence of a surface numbness or anesthesia which he now re-lated to the tough hide of the dragon. This anesthesia, as before, could be penetrated by music, which provided intense pleasure sensations "as if each nerve end were being simultaneously stimulated"; but whatever he touched was felt "as by one whose whole body is encased in a thin rubber glove." Bach's Brandenburg Concerto No. 4 was played and S was urged to permit his body to "dissolve." At first he was "over-whelmed by a bombardment of physical sensations, by tangible sound waves both felt and seen." The sensations were "erotic" and his intellect too now seemed to be "almost wholly genital." He closed his eyes and described great sinuous, jeweled shapes undulating through space. "Everything" was "coming in waves and from all sides." "Great waves of stimuli" were "crashing against the perrneable rock" S now felt him-self to be. He reported that "everything is happening now on a great universal scale. I can dissolve. Now I understand what is meant by being a part of everything, what is meant by sensing the body as dissolv-ing. I have a knowledge of all my particles dissolving and becoming incorporated into a sea of particles where nothing has form or even substance. In this sea there is no individuality."

It was not clear at this point whether S was moving toward an authentic or a pseudo-mystical experience. He was urged to continue the dissolution process and almost at once announced that he was resist-ing the process. "At the same time as I dissolve," he said, "I feel myself to be some kind of huge monument, some great stone edifice." Again, he was urged to "let go," to dissolve not only the body but also the self. To this he responded that "There are two ways of doing it. I can take everything into myself, or I can let myself go totally into what is not myself. 'This decision is the most difficult problem of all. I must see what I can do."

S then was momentarily diverted by images of "a huge beautiful ballet in which all of my physical and mental states are personified.

There are thousands of dance figures, each one of whom is myself. I am able to feel myself into each one of them, but am also able to combine them all and feel them as a totality." He then quickly returned to the "dissolution theme" and described an image of "horizons that go out and out and out. These expanding horizons are what I see and feel and am. This became possible when something was pulled away from over my head. A kind of net was lifted from the top of my head, and caught in the net and pulled away with it were many ugly things. Once the net and all that garbage had been pulled away the horizon could begin to go out. I now have no horizon at all. I have a feeling and knowledge of being physically boundless. There is an oceanic quality, yet sometimes I get washed up by some irritating passage in the music. I get washed up into dirty little bistros on tropical islands in the ocean."

Again S was urged to stop resisting, to allow himself the experience of boundless being. But now he found himself surrounded by "darting, oriental, snake-like things, moving in circles around me so that I cannot go beyond them." He began to breathe heavily and gave the impres-sion of being involved in some great internal struggle. His face red-dened, he started to perspire, and the facial expression resembled that of some mythological hero locked in mortal combat. After some min-utes he reported experiencing a "titanic struggle." His senses were un-willing to relinquish their "hold upon the earth." He complained of being "in bondage to serpentine, oriental forms that press down upon consciousness strangling its horizon." S struggles against these forces and, in so doing, experiences sensations more intense than any he has known. His effort, he now says, is directed towards "containing God." But the "Idea of God is too big to contain. One tries to know God by extending oneself outward in all directions as a circle radiates outward from its center along an infinite number of lines." S is told that he should not struggle any longer but simply "Be the circle extending outward, let yourself extend outvvard to meet God if that is what you want." S then wondered about the advisibility of this, saying that "If God is real, one would not dare to meet Him unless properly prepared." He laughed loudly and said that "My ego is still in pretty good shape. I find myself sitting down before the Majesty of God, but as a member of the House of Lords. The meeting place is long and narrow and contains a few minds who have elected God to His high office. We acknowledge our submission to His power, but only reluctantly."23 He adds that "Should I allow God to enter me, then I would expand as if filled with a wind, and finally I would burst."

After a silence of some minutes, S remarked: "I am locked in a titanic struggle. The creatures are enormous and symbolic. Whether I am losing or winning I don't know, because I don't understand the symbolism or what the outcome should be. Great colossi are fighting. Tigers and other beasts, hundreds of feet high, tear at one another's throats. These are the forces of myself, forces threatened with dissolu-tion should I abandon myself to God. The forces also have cosmic meaning—meaning beyond the meaning they have in my own psychology."

At this point, S reviewed a good deal of the material summarized at the beginning of this case. He tried to put his conflicts into conventional psychological terms, but declared himself unable to make a convincing formulation. Only religious terms were "relevant and valid" and "The big, essential conflicts are with God. Any others I am able to take care of by myself." Concerning his "conflict with God," S said that he found himself "impelled by a basic instinct of survival to fight against God. Should I be overthrown in this, then my I would be gone. To preserve itself my I must wage war against God. Once I give in, I am subject to God. My I is only able to preserve its singularity by blowing itself up very large and fighting against everything. . . . Either I meet God on equal terms, or I cannot meet him at all. I feel like a terribly battered boxer who gets knocked down again and again but keeps on getting up and coming in for more punishment. I am a battleground of the most titanic forces. All this time colossal tigers and enormous dragons are snarling at one another's throats. These forces I know to be symbolic and involved in my conflict with God, yet I still cannot say exactly what they are."

S reported that he was continuing to experience very intense sexual sensations and said that he feared abandoning himself to God because God might "take away" his "sexuality." The subject was now at the start of what proved to be a three-hours-long "battle with God." 'The psychical climate of this "battle"' was intensely emotional as at times S would "rage against God" and against his own "impotence in this terrible struggle." During much of this time he continued to describe what he was experiencing and we must condense the monologue:

"What Infinity takes away has to be infinite also. I would be sucked at both ends by God should I give myself up to Him. I am both giving all that I can and all that I have is being taken away. I have done all I can. God must sustain me if this effort is to continue ... Yes, yes I need God. I need Him out of the need that everyone has who knows he cannot stand alone against all of the forces of the universe. God has raised all these forces up and God alone can sustain them. But I don't see why I should have to fight all these terrible battles. Rather I'd pass unnoticed like some grain of sand on the beach. I see the promise of giving in to God, and also the threat if I do not. But I have started out with nothing but my bare hands and through the years have piled up plenty of weapons. If God tries to fight me in my own world, He will find me plenty tough to handle. And God, to fight me, has to be willing to assume certain human proportions. He has to dwindle down and make Himself almost human, come into the human sphere, to contend with those who can't fight Him on more potent levels.

"It is unfair! Unfair! I have no chance at all in this fight! [Here, S became extremely angry.] How do I keep my self-respect if give in to God? God stands with His foot on one's neck and will only take it away if one makes an abject surrender to Him. This I cannot do! All around me these damned tigers and dragons and herculean figures are fighting, trying to tear each other to bits .. . If we can neither give in to God nor successfully resist Him, then we have to settle for some smaller, less satisfying place in the scheme of things. But one doesn't accept it plac-idly. One always resents the fact that God is so much greater—and, even more, that God should make us aware of His greatness. One is ultimately defeated by God because one is defeated by an Idea that is greater than oneself.

"My mind goes out as far as it can go, and beyond that is God. I am beaten down again and again by it. My mind reaches out to encompass all and when it fails I get mad and start complaining that someone is greater than I. If I can't encompass all, at least I can defend myself. I can put on a suit of armor. When some small nation is threatened by a bigger neighbor and can't develop good enough offensive weapons, then it puts up good defenses. Still, there should be the possibility of some kind of agreement. To accept God seems to me to mean only surrender and this I haven't been forced to do. Every minute I fight very hard and am very, very tough. I am like an old general who has been through many wars, knows all the tactics and has developed his arsenal. . . . 'The more one acquires, the more one has to protect. What ultimately threat-ens can only be God, for ultimately God is whatever is other than oneself."

At this point the subject launched into a lengthy and scathing attack upon Christ. Christ was seen as "the archetypal demagogue, the personi-fication of the socialist concept in religious terms. . . Given all that man has learned in the last two thousand years, I consider that my mind is greater than God's mind personified in Jesus. God had to reduce Himself too much in order to make Himself comprehensible to the human masses. In Christ, God reduced himself to such miserable proportions no man of intelligence can accept Him."