9 The Escalation Theory

| Books - The Strange Case of Pot |

Drug Abuse

9 The Escalation Theory

The Logical Fallacy

'It cannot be too strongly emphasized that the smoking of the marijuana cigarette is a dangerous first step on the road which usually leads to enslavement by heroin.' This is a quotation from a . pamphlet issued by the United States Bureau of Narcotics in 1965. The most repeated argument against cannabis is that those who use it are likely to go on to more dangerous drugs, in particular heroin.

This is variously described as progression, predisposition, escalation and the stepping-stone theory. Here I shall use the word escalation because it has come into recent popular use to signify the deterioration of a situation.' Whichever word is used, the notion of cause and effect is implied — that cannabis leads to heroin addiction; or, to put it the other way round, a large number of people would have escaped heroin addiction but for their use of cannabis.

The Wootton report dealt with this controversy in four carefully worded paragraphs (48-51) and came to the conclusion that the 'risk of progression to heroin from cannabis is not a reason for retaining control over this drug'. This conclusion was reached after considerable discussion and the exhaustive examination of the available evidence, but it seems to have had very little effect. Both the press and public continue to make statements as if the Wootton report had never been written. The editorial in the Daily Express repeated the escalation theory as the reason for rejecting the report on the day it was published. A letter in the Sunday Timer on 19 January 1969 asked: 'What about the more important information from people who have nursed many drug addicts whom they know have "graduated" from cannabis to heroin.' There have been many paragraphs in local papers similar to one that appeared in the Hampstead and Highgate Express on 22 August 1969, reporting a case of a twenty-year-old man found in possession of cannabis: The Chairman of the magistrates, Councillor Geoffrey Finsberg, said: "The bench is determined to stop this nonsense which leads on to harder drugs,"'

Most people rule out the possibility of a pharmacological action which would predispose pot smokers to heroin. The most usual statement given in support of escalation is that most heroin addicts started on pot. The usual figure given is between 80 and 90 per cent and this is supported by retrospective investigations into the background of addicts, mostly from America. The same investigations show that the use of the word 'started' is misleading, because cannabis was by no means always the first drug the addicts had taken; nearly all of them had taken alcohol and tobacco before cannabis, and many had also taken amphetamines. The implication of the statement is that cannabis leads to heroin, but it is a logical fallacy to state that pot smokers will go on to hard drugs because the majority of heroin addicts have taken cannabis. One might as well say that most whisky drinkers will go on to methylated spirits because most meths drinkers have drunk whisky.

For many years investigators have studied the background case histories of drug addicts in clinics, hospitals and prisons. They can quite honestly and sincerely state that most heroin addicts have used cannabis. But this is not a statement of cause and effect. It is merely a statement of association. The statement immediately becomes false if someone interprets this sequence in time as a causal relationship.

It is also worth remembering that the relationship between heroin addicts and doctors at the treatment centres is a very special one. The addict is fully engaged upon the business of persuading the doctor to give him all the heroin he wants. The doctor is trying to cut down the daily dose. It is well kflowh that junkies become expert liars and will say almost anything if it will help to wheedle a little extra out of the doctor. A junkie talking to a doctor who is known to be an advocate of the escalation theory is going to do his best to please him and would quickly agree to the implied suggestion that pot was the start of his downfall.

Evidence obtained from retrospective investigations into the previous habits of heroin addicts can never provide conclusive evidence to support the escalation theory. The only way to get a proper idea of the extent of escalation is to find a representative group of pot smokers and follow up their progress each year, noting how many go on to heroin, and how many continue to smoke only pot, and how many give up cannabis altogether. Such a research would take rather a long time and it would have to be a large group because even the most positive advocates of escalation do not put the number likely to go on to hard drugs higher than 15 per cent. Nevertheless it is surprising that no one has undertaken this research, considering the importance of the subject and the strong feelings that it arouses.

Correlation or Causality

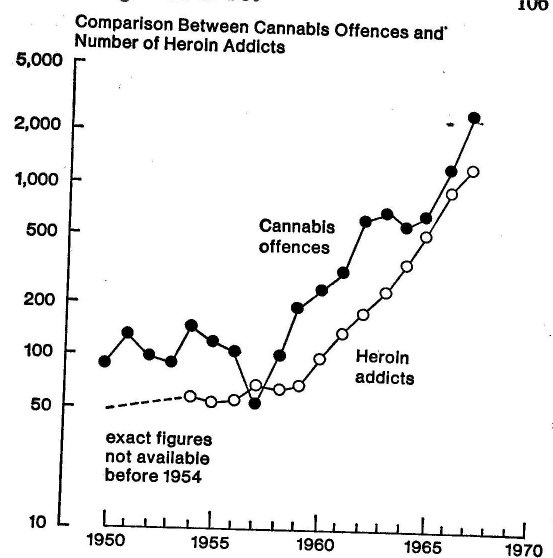

Another important argument in support of escalation is that official figures show a sudden rise in arrests in 1957 followed by a rise in the number of heroin addicts two years later. Since then the number of addicts and cannabis offenders have continued to rise at about the sane rate.

A considerable disadvantage of this evidence is that the figures are concerned with individuals who have been arrested or who are under treatment. As we now know, people who have come to the notice of police or doctors are hardly ever typical of a particular group of deviants. The same error was made about homosexuals. For many years the only research made into this phenomenon was by questioning homosexuals in prisons and clinics. But most homosexuals do not get arrested and do not seek treatment. It was not until a detailed study had been made of the attitudes and activities of homosexuals who had not been in trouble that the real characteristics of homosexuality were better understood?

It is equally misleading to make generalizations about all users of cannabis from investigations limited to studies of pot smokers who have been arrested or are under treatment - whether they have escalated to heroin or not. There is no doubt that there are certain types of pot smokers who are more likely than others to get arrested, perhaps because of their behaviour, clothes, colour, or simply because they make themselves more conspicuous. But most users of cannabis do not attract the attention of doctors or police.

It is dangerous to imply cause and effect because two phenomena have a high statistical association. It is not always possible to decide which is the cause and which is the effect. It would be possible to use the same figures to suggest that cannabis delayed the onset of heroin addiction - the 80-90 per cent addicts who have previously used cannabis might have become addicted to heroin one or two years earlier if they had not taken cannabis. A much more probable explanation is that both phenomena are caused by a third factor. In this case it may be an attitude of mind which includes the desire for recreational drugs. This would explain the association of cannabis with heroin addiction, not because one was the cause of the other, but because both are caused by the same trait - the desire for recreational drugs.

Certainly we need evidence of a different kind before we can deduce that cannabis leads to heroin because most addicts have used pot. In fact much of the evidence points in the opposite direction. If the escalation theory were true, there would be a more even distribution of heroin addicts throughout the country; over three quarters of all heroin addicts known to the Home Office live in London, but cannabis is smoked in many other areas. One would also expect more of the addicts to come from Pakistan or the West Indies; less than 3 per cent of all addicts on the Home Office list are coloured immigrants, but the Wootton report contained figures which showed that 38 per cent of all cannabis offenders were coloured.

John Kaplan (1970) has made a careful study of the overall arrest figures in America and has come to the conclusion that if the stepping-stone effect exists at all, it will most likely be found only in certain particular segments of our society such as among poor Negroes and Mexican-Americans'. He compared cannabis offenders with heroin offenders and failed to find, the same correlation that Paton (1968) and others have found here.Between 1960 and 1968 arrests in California for cannabis offences rose by 703 per cent, but arrests for heroin rose only 7 per cent; in 1960 arrests for heroin crimes were 52 per cent of the total adult drug arrests; by 1968 the percentage had fallen to 12 per cent.3

It is, of course, a much more meaningful comparison when both groups are offenders, but it is not possible to do this here because the number of people arrested for heroin offences is so small. In Great Britain the registered heroin addict does not need to buy his drug asfie can get it free on prescription from a treatment centre. The situation in this country is in some ways ironic, for the pot smoker has to buy his supply, while the heroin addict can obtain his much more dangerous drug free if he registers at a treatment centre. I suppose this could be a possible reason why a pot smoker goes on to heroin although I have never heard anyone suggest this.

Statistical Calculations

The Home Office believes that most addicts have now registered, as it is obviously in their interest to do so. The largest group who have not registered would be the new addicts who have to admit to themselves that they are dependent on the drug before they can persuade themselves to go to a treatment centre to register. The result is that the total number of narcotic addicts in the country is known4 to within a margin of error of two or three hundred.

We have no idea of the number of people who take cannabis. The Wootton committee felt unable to make any kind of estimate; they reported that guesses ranged between 30,000 and 300,000. This is such a wide range that it is not really possible to make sensible use of these figures. Furthermore I do not think a more accurate estimate is possible at the present state of our knowledge.5 In any case it is necessary to define what is meant by users of cannabis. Goode (1969) concludes that most of those who have tried cannabis do not use it more than a dozen times. If this is true, obviously it is important to distinguish between people who have tried it a few times and those who use it regularly. There is also a very large intermediate group who smoke pot intermittently and on rare occasions at parties or while away from home.

It is the total lack of knowledge about the number of cannabis users in Great Britain that undermines the arguments put forward by W. D. M. Paton (1968), professor of pharmacology at Oxford University, who is the best-known advocate of the escalation theory. He has corripared the number of cannabis offences and the number of heroin addicts. In his graph, reproduced overleaf, the data is plotted with logarithmic ordinates so that rates of growth can be compared.

This figure reveals a strong association, but there are three things (already noted) to take into account.

1. Professor Paton is comparing two very dissimilar groups; one group is almost all the known heroin addicts, the second group is a small minority of cannabis users.

2. Cannabis users who have been arrested are not typical of the whole group.

3. A causal relationship should not be inferred from a statistical association without supporting evidence.

The major piece of evidence produced by Paton is based on the assumption (which hardly anyone would accept) that cannabis and heroin have nothing to do with each other; then he sets out to disprove this hypothesis. To no one's surprise, he succeeds.

The hypothesis is tested by using a method of inverse probability (a version of Bayes' theorem). By using this statistical manipulation, Paton calculates that 7-15 per cent of those who take cannabis will be, or are, heroin addicts.6 He gets this result by starting with a very low figure for the total number of cannabis users. His estimate is far below the figures given in the Wootton report. If he had taken the average of the two figures suggested in this report (i.e. 165,000 instead of his figure of about 25,000), his result would have been far less than one per cent.

Paton concludes that 'there is, at least for our culture, a far closer connection between cannabis and the opiates than is generally realized'. This is an extraordinary statement when one considers that it is the general view that cannabis and hard drugs are closely connected, and it is the minority who feel that the escalation theory is based on spurious evidence.

Nor does Paton contribute anything of value by using a statistical manipulation7 to disprove the statement that there is no connection between cannabis and heroin. No one in his right mind would insist that there is absolutely no connection between pot smoking and heroin use. It is the extent of the connection and its nature that is important. Most addicts have taken cannabis; the first experience of heroin is nearly always after taking pot, not before; cannabis consumption has risen in the last ten years and so has the rate of heroin addiction. All this is well known and not very surprising. One would expect to find some kind of connection between one recreational drug and another.

It is interesting that the escalation theory is always stated as a progression from cannabis to heroin, although the arguments would lead one to expect that it also applied to other recreational drugs. There is nothing particularly unique about the connection

." between cannabis and heroin. Paton's calculations show there is also a connection between amphetamines and heroin. Blum (1965) found that the correlation between opiate (including heroin) and cannabis use was no higher than that between opiate and amphetamine use, and it was lower than between opiates and sedatives, or " tranquillizers, or glue, or nitrous oxide. On the other hand the correlation between cannabis and various other drugs was higher than with the opiates; for example, the correlation between canna' bis and L SD was considerably higher than the correlation between -- cannabis and heroin. It seems likely that the escalation theory is just another way of making the unsurprising statement that people who have taken one recreational drug are more likely than nonusers to have taken other drugs.

Multiple-Drug Users

The most plausible explanation for the connection 'between cannabis and heroin is that among any group of illegal drug takers, there is a small minority who will turn out to be multiple-drugs users. These are disturbed individuals with severe personality disorders who will start on the drugs which are easiest to get, but will continue to try other drugs until they find one which they cannot discontinue in favour of another because they are trapped by its addictive power. The multiple-drug user is also particularly attracted by the ritual of injecting his drug intravenously. This was particularly noticeable after the epidemic of methedrine (an 'amphetamine) taken intravenously. When the supply was stopped the multiple-drug users turned to injecting a wide variety of other substances (including heroin, barbiturates and Mandrax).

The flaw in the escalation theory is that it postulates that there is something special about cannabis. Nearly all investigations show that most heroin addicts are multiple-drug users who have tried almost anything that has come their way. In Blum's (1965) sample of opiate users, 100 per cent drank alcohol, 95 per cent smoked tobacco, 78 per cent used cannabis, 73 per cent used barbiturates, 66 per cent amphetamines, 62 per cent tranquillizers, 50 per cent hallucinogens and 33 per cent other drugs. In James' (1969) study of addicts in prison, 88 per cent had used methedrine by injection, 75 per cent amphetamine tablets, 66 per cent had smoked cannabis and the same proportion had taken barbiturates.

Most multiple-drug users have the emotionally impoverished family backgrounds not infrequently found in other delinquent groups, such as high incidence of broken homes, poor school records, unemployment, work shyness, and police records. In the words of the Wootton report: 'It is the personality of the user, rather than the properties of the drug, that is likely to cause progression to other drugs.'

It is necessary to add that there is an element of infection. It is not possible to become a multiple-drug user unless one discovers how to obtain a multiplicity of drugs. It is unlikely that an individual, however severely disturbed, would become a multiple-drug user if he was born and remained in a remote village all his life. To this extent contact with other drug users in the hard drug scene is epidemic and fortuitous. Therefore the chance of a disturbed personality going on to heroin depends upon the setting in which he finds himself. There are areas and groups where cannabis use is extensive, but there is no problem of heroin addiction, for example, in Morocco; and there are areas and groups where heroin is widespread and cannabis is hardly used at all, for example, until recently in Vancouver.

People object to this concept because multiple-drug use is recent whereas individuals with personality disorders have always been with us. The answer is that if the disordered individual does not find his way to the drug scene, his disability will come out in some other way, perhaps more violent and disruptive. The disposition to multiple-drug taking involves complex psychological mechanisms which we are only just beginning to understand, but it is possible in the not too distant future that we may discover some characteristics which can help us to spot the potential drug abuser. Then in any group using recreational drugs it may be possible to predict that certain individuals will continue to experiment indiscriminately with dangerous drugs, and thus preventative measures may be devised.

The Distinctness of the Two Drugs

There are a few other arguments used to support the escalation theory. One is that tiring of the novelty or pleasure to be obtained from cannabis, users go on to other recreational drugs. The effects of pot are relatively benign and for some, it is suggested, this may not be enough. It cannot be guaranteed as a relief from depression. The novelist William Burroughs writes: 'It makes a bad situation worse. Depression becomes despair, anxiety panic . .

In fact most pot smokers look down on junkies and certainly do not feel that heroin has more to offer. Many regular users are very satisfied with the effects of pot and tend to reduce the dose as they become more experienced.

Heroin can not be described as a drug 'similar to cannabis, but stronger' — a description which some might use of L SD. Heroin is quite different. It is much harder for the experimenter to obtain, for, unlike pot, one has to have a working knowledge of the drug scene in order to buy heroin illegally. It is injected, whereas cannabis is smoked, and this involves an immense step emotionally for many people who are used to smoking but view the idea of using a syringe with abhorrence. Most important of all, the effects of the two drugs are so dissimilar; heroin is more like a sedative or a super tranquillizer. It is a drug that has attractions for the disenchanted who are constantly searching for something to provide escape from the tribulations of the real world. Cannabis increases awareness; heroin dulls the senses. Only rarely are both drugs attractive to the same person.

Another suggestion is that cannabis users must buy their supplies from the same source as the sellers of heroin: as both sources of supply are illegal, pot smokers have to contact people in criminal networks and run the risk of being contaminated. This argument fails on two counts. (1) Pot smokers rarely procure direct from big dealers, but buy from friends and fellow pot smokers. (2) Nearly all addicts get their heroin free on prescription. Consequently people who sell cannabis do not sell heroin.

This argument implies that it is the law and the police who are most responsible for the escalation from cannabis to heroin. Supporters of legalization say that it is the prohibition of cannabis, and not cannabis itself, which may lead on to heroin. There may be some substance in this. For many years teachers and others have been warning young people about the dangers of cannabis. Now that so many young people are discovering for themselves that it is nothing like so dangerous as they have been told, there is the risk that when they are offered heroin, they will not believe what they have been told about the dangers of hard drugs. Some who have been harassed by the police because they are pot smokers may decide that they will be no worse off if they go on to heroin. Indeed they will be better off so far as the law of the land is concerned, because they will be able to get their drug supplies legally; if they go to a treatment centre and register, they will get their heroin free. It is not possible to register with the Home Office as a cannabis addict. Clark (1965), the American writer of a book entitled Dark Ghetto, argues:

The fact that those who use marijuana, a nonaddicting stimulant, are also required to see themselves as furtive criminals could in some part also account for the presumed tendency of the majority, if not all, drug addicts to start out by using marijuana. It is a reasonable hypothesis that the movement from nonaddicting drugs or stimulants to the addictive is made more natural because both are forced to belong to the same marginal, quasi-criminal culture.

The situation is different in America because all heroin is bought illegally and is expensive because supplies are controlled by the Mafia. No criminal syndicate thinks it is worth while to control marihuana in America or cannabis in Britain. The supplies come from too many areas and its users do not become continuous daily customers.

But it may well be true that outlawing cannabis has a deleterious effect. It encourages a disrespect for the law and forces the user to smoke in secret. Any minority group tends to adopt anti-social attitudes when it finds its activities are illegal. The effect is to 'criminalize' a large segment of our community and the result is bound to be disruptive.8

Nevertheless the majority of pot smokers do not associate with heroin addicts in spite of the fact that they are both using illegal drugs, and both have used, or still use, cannabis. The typical pot smoker has never met a junkie and has no access to heroin. Their way of life is distinct and their values are incompatible.

The Inevitable Conclusion

Some people believe that even if escalation operates in only a minority of cases, the needs of this minority are an overwhelming argument in favour of the prohibition of cannabis. At first sight this seems to be a question of numbers to be solved by adequate - research. If it turned out that one in ten became addicts, most people would think the risk too great; if it were one in a hundred, many would still feel the chances were too high; if it were one in a thousand, the argument would be less compelling. Bu't the problem cannot be so easily solved. So long as cannabis is illegal, pot smokers as a group are going to contain an untypical proportion of rebels, drop-outs and people with personality problems. Even if it can be shown that one in a hundred of today's pot smokers will go on to heroin, it by no means follows that this proportion would be the same if cannabis were legalized.

The only reasonable conclusion is that escalation is best explained by the presence of potential multiple-drug users in any group taking an illegal drug. The Wootton report concluded that 'cannabis use does not lead to heroin addiction'. This finding is not unique. All the recent independent reports and investigations have come to the same conclusion. Bender (1963) writes that marihuana 'only occasionally is followed by heroin usage, probably in those who would have become heroin addicts as readily without marijuana' and Blumer (1967) reports: Popular conceptions of youthful drug use almost always presume that youthful users move along a line of development ending in heroin addiction. Our evidence offers no support to these conceptions but, instead, largely contradicts them.'

But there will still be many who remain unconvinced. It is almost as if the public wants to believe that those who smoke pot will end up as heroin addicts.

1. Whereas the word progression, used in the Wootton report, tends to ' imply improvement as well as forward movement.

2. The Sociological Aspects of Homosexuality, by Michael Schofield, Longmans, 1965.

3. Figures from the Bureau of Criminal Statistics, Department of Justice, State of California, 1968.

4. 1,466 in 1969.

5. When the law is changed so as to permit research into cannabis, it will be possible to devise an inquiry, given sufficient time and money, to make a fairly accurate estimate of the incidence, just as it was possible to give reliablefigures on teenage sexual activities a few years ago — The Sexual Behaviour of Young People published by Penguin Books in 1968.

6. Bayes' theorem states that A = B x C : D where

A = the incidence of heroin taking among cannabis takers.

B = the incidence of cannabis taking among heroin takers.

C = the incidence of heroin taking among the population at large.

D = the incidence of cannabis taking among the population at large. Paton estimates that 90 per cent of heroin addicts have taken cannabis (B), 5 per 100,000 of the population take heroin (C), and 30-60 per 100,000 take cannabis (D). By using these estimates, he calculates that A = 7-15 per cent according to the value given to D.

7. Bayes' theorem itself is the subject of controversy among statisticians.

8. This important point is developed in more detail in chapter 12.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|