6 The British Scene

| Books - The Strange Case of Pot |

Drug Abuse

6 The British Scene

The Early Days

Cannabis has been taken for hundreds of years in India and the Middle East, but it is only very recently that it has become a problem in this country. Except for the areas bordering directly on the Mediterranean, there was very little interest in cannabis in Europe. Although the famous Club des Hachichins was established in Paris, Gautier and his friends were thought to be a very eccentric group and the use of hashish did not spread.

After the cultivation of hemp was abandoned in America, the remaining plants were allowed to go to seed and became weeds which spread across the United States. But it was not until this century that a new generation found a use for this prolific plant. It was the Mexican labourers who introduced the idea of smoking it. By 1926 cannabis was well known in New Orleans and gradually its use spread to all the large urban areas of the United States. At first it was mainly consumed by Mexicans, Negroes and Puerto Ricans — the minority groups living in poverty in the large cities. In some ways these people were similar to the users in Arabic countries who found that cannabis could bring comfort and relief from the hard living conditions of the very poor.

But then a strange phenomenon developed. Instead of the habit spreading gradually up the social scale which might not have been unexpected, what happened was a new interest in cannabis among a quite different section of the community. At first a small group of intellectuals, stimulated by the writings of Aldous Huxley (1959), tried experiments with mescaline and cannabis. But from 1960 onwards the development of the civil rights and then the hippy movements gave impetus to this interest and marihuana became the subject of much speculation and discussion among middle-class students, university staff, entertainers and artists. For the first time there were a number of articulate voices who questioned the old assumptions about cannabis.

But before this happened the US Government had already made it illegal by passing the Federal Marihuana Tax Act which effectively prohibits the use of the drug. This was in response to public demand starting about 1930 when the popular press began to create and spread a number of myths about marihuana. For some reason sensational stories about this drug have always been I thought by editors to be good news stories which will sell papers. The series of myths which were circulated forty years ago in America are still used even today to support arguments against the use of marihuana.

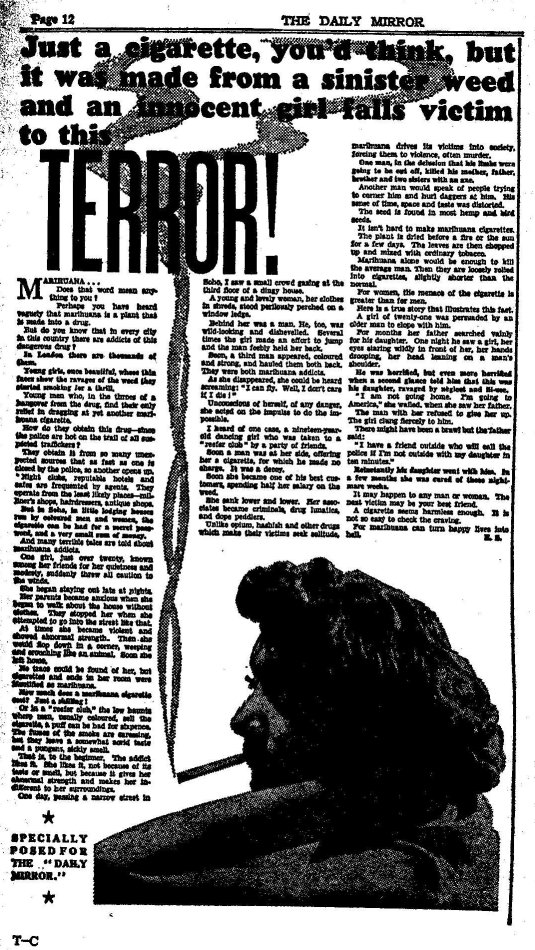

Similar alarming and picturesque stories appeared in British newspapers from time to time. One of the earliest examples was in the Daily Mirror on 24 July 1939. Under the long headline 'Just a cigarette you'd think, but it was made from a sinister weed and an innocent girl falls victim of this TERROR', this full-page article contains most of the famous marihuana myths.

The idea that it is addictive:

In London there are thousands of them. Young girls, once beautiful, whose thin faces show the ravages of the weed they started smoking for a thrill. Young men who, in the throes of a hangover from the drug, find their only relief in dragging at yet another marihuana cigarette.

The stories about cannabis leading to violence and other reactions which are the exact opposite to the known medical effects; the reference to abnormal 'strength' suggests that the reporter got this from a description of the effects of cocaine:

One girl, just over twenty, known among her friends for her quietness and modesty, suddenly threw all caution to the winds. She began staying out late at nights. Her parents became anxious when she began to walk about the house without clothes. They stopped her when she attempted I to go into the street like that. At times she became violent and showed abnormal strength. Then she would flop down in a corner, weeping and crouching like an animal.

The well-known stories about drug users leaping from windows, usually told about LSD nowadays:

A young and lovely woman, her clothes in shreds, stood perilously perched on a window ledge. Behind her was a man. He, too, was Wild-looking and dishevelled. Several times the girl made an effort to jump and the man feebly held her back. Soon a third man appeared, coloured and strong, and hauled them both back. They were both marihuana addicts.

The suggestion that the traffickers are coloured:

But in Soho, in little lodging houses run by coloured men and women, the cigarette can be had for a secret password, and a very small sum of money.

The fable that a person can smoke cannabis and be hooked on it without realizing it:

I have heard of one case, a nineteen-year old dancing girl who was .taken to a 'reefer club' by a party of friends. Soon a man was at her side, offering her a cigarette. It was a decoy. Soon she became one of his best customers, spending half her salary on the weed.

The confusion with other drugs:

Unlike opium, hashish [sic] and other drugs which make their victims seek solitude, marihuana drives its victims into society, forcing them to violence, even murder.

And inevitably the suggestion that marihuana and irresistible sexual desires are linked together:

For women, the menace of the cigarette is greater than for men. A girl of twenty-one was persuaded by a coloured man to elope with him.

All of these myths have been repeated time and again over the thirty years since this story first appeared. There are, of course, many serious arguments against the use of cannabis (and these are studied in detail in later chapters). But every informed person knows that cannabis is not addictive, does not make the user suicidal, is not sold only by coloured people, cannot be disguised as ordinary tobacco, does not drive users to violence and murder, and is not an aphrodisiac.

Newmark (1968) gives several examples of sensational press items about drugs:

'The problem of drugs is the worst we have had to face since the Black Death.' Speaker at the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland.

'LONDON SETS DRUG WATCH IN SCHOOLS.

"Happening all over the place" — A doctor.'

Actually the doctor said that as yet he had no evidence of widespread drug taking in schools but he had his suspicions.

A well-known writer in the Daily Express wrote `... Dr Plumb

. has just written in the Spectator arguing that drug taking should be legalized.' In fact Dr Plumb, a professor of history at Cambridge, suggested that after suitable research it might turn out to be more sensible to permit the use of cannabis (not all drug taking) rather than ban it.

The press still tends to treat all drugs as though they had the same effects and were equally dangerous. When the report on amphetamines and LSD was published in March 1970, several newspapers summarized the recommendations as if they applied to all drugs and quoted figures for the number of heroin addicts which were quite irrelevant. 'HIDDEN MENACE OF DRUGGED DRIVERS' in the Evening Standard referred to anti-histamines used to relieve travel sickness, not to illegal drugs. In January 1968 the Guardian had a headline: ' MARIJUANA AND LSD COULD RESULT IN "MONSTER CHILDREN".'

' Alex Mitchell (1969), a reporter on the Sunday Times, noted that the Daily Express in 1967 reported that 'students bought drugs from an attractive Swedish blonde at undergraduate parties'. Mitchell wondered 'whether she was the same girl who cropped up in a Daily Telegraph article almost three years earlier' when it reported that a group was 'organizing the manufacture of reefers for Cambridge undergraduates. They are believed to include a West Indian, a Frenchman and a blonde Swedish girl.' Mitchell adds: 'Needless to say the Baltic beauty was never named: she remains a part of the drug mythology which Fleet Street has constructed over the past ten years.. . . Exploring the cuttings covering five decades revealed an unbelievably shallow approach to the reporting of drug affairs.'

In fact there was no drug problem of any kind in Great Britain before 1914. It was something the Chinese did in Limehouse. When the Egyptians first demanded that the drug should be put under international control in 1924, the British reaction was not untypical. They suggested a committee to study the situation, but they were overruled and so controls were introduced in Britain in 1928 in order to implement an international agreement.

But cannabis was not a British problem at that time. The highest pre-war figure for cannabis offences was 18 and this was in 1938. About twenty years ago the Customs found that increasing quantities were being brought into the country, mostly by immigrants; at first the chief offenders were West African, but later there were more West Indians.

In 1950 there were over a hundred prosecutions for cannabis offences for the very first time. This was the result of a series of raids on certain London jazz clubs and it became clear that cannabis was now being used by Englishmen as well as by immigrants. But it was not until 1964 that there were more white people than coloured being convicted of possessing cannabis. Today there are three times as many white as coloured offenders.

Middle-Class Users

In one important aspect the spread of cannabis in Britain differs fundamentally from the American experience. In this country cannabis has never been the favourite drug of the poverty-stricken and undernourished. There is no equivalent in Britain to the poor hashish users in Arabic and Asian countries or the Mexicans, Puerto Ricans and Negroes smoking marihuana in the large urban communities of America. The deprived in Britain stick to alcohol, and the down and out to methylated spirits. It is true there were the same scare stories in the press as in America, and the same sudden middle-class interest among students and intellectuals, but the original smokers in this country, the seamen and musicians, were not from the depressed classes. Thus there is no history of extensive cannabis misuse among the very poor and social workers do not -associate this drug with the criminal fringe, the psychopaths and others with severe personality disorders.

Even now cannabis is not the main illegal drug for ' working-class users. People from the depressed areas in this country are more likely to use amphetamines, even though this ' drug is harder to obtain. Pep pills are also the favoured drug in the criminal sub-cultures. Scott and Willcox (1965) found evidence of amphetamines in urine tests in 17 per cent of admissions to remand homes. No doubt some people have taken cannabis before committing a crime, but it is unlikely to be helpful; amphetamines increase courage and energy, but a man under the influence of cannabis prefers to sit still and enjoy himself passively.

A British criminologist (Downes, 1966) noted that the British . user of cannabis was 'hip', middle class or student class. An American writer (Chein, 1964) agrees that the interest in cannabis in Great Britain tends to spread down, not up, the socio-economic scale. The cannabis users during the 1967-8 hippy movement were rarely working-class youths; these articulate proselytizers were more likely to be drop outs from grammar schools and colleges.

Until recently middle-class boys and girls were influenced hardly at all by the new working-class youth movements. The era of rock and roll, starting with Bill Haley and the Comets in the late 1950s, - was brash and aggressive. The spread of pep pills started during the days of the teddy boys and the racial explosions in Notting Hill and Nottingham. From this came the mods on their scooters and the jockers on their motor cycles meeting and fighting on the beaches at 'Southend, Brighton and other holiday resorts. It was a restless violent period when youth clubs and cinemas were smashed for '_ertjoyment, but it had little to do with the politically committed

tivities of CND and the later student demonstrations.

The present-day successors to the rockers are probably the Hell's Angels, the Californian gangs of outlaw motor cyclists who have , established a few chapters (or units) in the South of England. A similar, more recent, phenomenon is the gangs of young working-class boys called 'skinheads', an inelegant, strangely puritanical group who go out to cause agro ' - a skinhead term for aggravation and violence. But these movements attract only a minority of the young people of today. For many others the swinging teenage scene is represented by the stars of pop music and the new hair styles and bright fast-changing fashions in clothes. At the other end of the spectrum is the `underground' or alternative society', the movement which developed from the beats, and later the hippies. Stimulants and violence are quite alien to this new teenage cult. This is a rebellion against authority and materialism, but it is also a thoughtful search for new values in which cannabis plays a part.

The Underground

Cannabis has also been associated with the development of new forms of folk music and contemporary art. Whereas the amphetamines attracted the rockers and their successors because the pills energized and stimulated the physical capacities, cannabis seems to have greater effects in the spiritual sphere, increasing the inward-directed mental faculties. It is a drug of contemplation and peace. This is why it is particularly attractive to those in the psychedelic sub-culture (Brickman, 1968). Cannabis is their favourite drug because its effects reflect the desire for tranquillity and nonviolence and it is popular in the Eastern countries whose philosophies have encouraged the people in the underground to take a fresh approach to religion.

But it would be unfair to suggest that the underground is only concerned with cannabis and drugs. It is a genuine protest against present-day materialist values, with a special interest in the mystical elements of life. Leech (1969) in a Christian analysis of this sub-culture writes: 'It is a serious movement with a concern for new values based on love, and it has brought about what can only be described as a new spirituality.' It is ironic that these young people without religious affiliations are interested in the transcendental aspects of religion at a time when Christians, particularly the `new theologians', are turning away from this towards reasoned intellectual problems.

The underground also has serious social and political aims, expressed vehemently and passionately in IT,OZ,Black Dwarf and other periodicals which provide the movement with focus and cohesion. /T has a circulation of 48,000 and must be read by more than twice that number.

Silberman (1967) thinks that cannabis

enjoys particular popularity among those who, for one reason or another, are unable or unwilling to participate in anything in regard to which the possession of a well-developed drive for power would be of great importance. In ideological terms it would be true to say that it is the drug of those whose general orientation is anti-authoritarian, anti-militaristic and, in the context of contemporary Western societies, anti-establishment.

Work on the underground is a hustle' or 'gig' which are words used for any non-violent means of making money which does not require regularity or taking orders from supervisors without question. Greys' are the people who work for wages until they get a pension. None the less several excellent self-help organizations, such as Bit and Release, have grown from this movement.

Bit is a two-way information service for young people who cannot get on terms with the existing organs of our society. It started in the summer of 1968 as a simple information service but people soon made it much more than that. On average, London Bit answers over 1,200 inquiries a week, mostly by telephone. 'People want pads, jobs, advice, help. And we've got to give it to them. The pregnant chicks are ours, the people with nowhere to live are ours, the people using drugs are ours, the failures are ours and the losers are ours too.' This is from an advertisement for Bit, which is essentially a twenty-four-hour-a-day, seven-day-a-week, advisory bureau and emergency service for unattached young people, operating from an office provided by Westminster City Council. Bit was conceived as self-help and many of the 200 voluntary workers are from among those who have been helped.

Release was established to help those who have been arrested for drug offences and to arrange for them to be represented by lawyers who have experience of such cases. Advice is given on individual rights regarding searches, arrests, court procedures and the interpretation of the law. Financial assistance is provided in those cases where legal aid has been refused, and medical attention, work or accommodation is arranged for those who need it. Release is run entirely by young people and a report of the work done since it started in 1967 (Coon and Harris, 1969) showed that in one year 603 people had been helped; 364 (60 per cent) of these were cannabis users.

These and other self-help organizations are set up to help these young people, including many who take cannabis, to find their way in a society with which they are unsympathetic but in which they must live. There are others who take this social alienation to its logical end and try to live their own lives without contributing to or taking anything from the community around them. In fact this is very difficult to do as our society tends to be all-embracing. These people find it very hard to keep their independence and despite their best resolution they become aware that they are dependent on the state and its ramifications. The ideal of cutting off from materialist society is occasionally attained in self-contained rural settlements founded in the United States; in general our climate makes such enterprises very hard and unattractive.

It is important to note that the psychedelic underground is quite distinct from the hard drug scene or from the Soho drug subculture. It has hardly any similarities with the purple-heart craze of a few years ago, nor is it connected with the amphetamine users to be found in Soho and the East End of London. The 1968 outbreak of injecting methedrine (an amphetamine obtainable in ampoules and known as 'speed' in the drug world) spread from central London to distant towns, and for the first time provided a link between the 'pill heads' (amphetamine users) and the junkies' (heroin addicts). But very few cannabis users were involved and IT and other underground publications campaigned vigorously against it with slogans like SPEED KILLS

Other Users

The young people of the underground are the best-known users of cannabis, but they are not the only ones. There are many more who smoke hash for pleasure at week-ends as their equivalent to other people's alcohol. They do not join campaigns to legalize pot, ?- nor are they articulate defenders of the drug. Consequently they are harder to identify.

Most people agree that a large number of immigrants use cannabis, but it is very difficult to get any idea of the actual nuns-hers or the proportion within each immigrant group that takes this drug. Although it is illegal to use cannabis in most African and the Caribbean countries, its use is traditional and it is not usually prosecuted unless it is practised very openly. It is generally regarded as a pardonable and not very serious fault, so it is not surprising that many do not give up the habit when they come here. Some immigrants from Cyprus, Malta and Pakistan also use cannabis. It is not true, however, that the majority of coloured men smoke pot. The Wootton committee did not find any clear link between immigration and cannabis smoking.

The Wootton committee also reported that there was a growing number of workers among the unskilled occupations who were using cannabis; these people were said to be industrious and law-abiding. But there were others who had dropped out of the educational system and were actively rebellious. Some of these people avoided any kind of regular work and were often in trouble with the law. But very few of this group kept exclusively to cannabis. They 4ended to be severely disturbed and were prepared to take any drug they could find. This multiple-drug use nearly always includes cannabis because it is one of the easiest drugs to obtain, but it is a mistake to confuse these junkies with people who only smoke pot.

Unfortunately there has been no research which helps to give a description of the cannabis users in Britain. In an investigation in Oakland, California, a group of young people were firm in their conviction, based on their own experience, that marihuana resulted in harmless pleasure and increasing conviviality, did not lead to violence, madness or addiction, was less harmful than alcohol, and could be regulated. They cited case after case of individuals known to them who had not been harmed in health,

school achievement, athletics or career as a result of smoking cannabis; and they were not themselves interested in being helped to abstain from the drug. The investigators (Blumer and associates at the University of California) make the important point that these young people are not opting out; on the contrary they are making a positive effort to conform with the accepted activities of others in their group. The investigators conclude that youthful cannabis use in Oakland is an extensive and deeply rooted practice, 'and is buttressed by a body of justifying beliefs and convictions, involves a repertoire of practical knowledge and incorporates a body of precautions against apprehension or arrest. Drug use constitutes for the users a natural way of life and does not represent a pathological phenomenon.'

A similar study in this country would probably disclose areas where the use of cannabis is now socially accepted in the same way as in Oakland. But there are many more areas where any kind of drug use apart from alcohol and tobacco are denounced as dangerous behaviour.

The only certain indication of these opposing views is age. There are very few men or women over the age of forty who use cannabis, and most people who smoke pot are nearer twenty than thirty. This is a most unfortunate division in the generations which inevitably brings accusations about immaturity on one side, and complaints about repression from inflexible fuddy-duddies on the other side. It is exactly because older adults cannot look back at youthful personal experiences of cannabis (as they can at other youthful indiscretions) that they must be most careful not to misjudge the situation or jump to unfounded conclusions.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|