4 Legal Aspects

| Books - The Strange Case of Pot |

Drug Abuse

4 Legal Aspects

The Development of International Controls

When I first came to study the arguments for and against the use of pot, one of the strongest considerations to my mind was the attitudes of the World Health Organization and the United Nations Commission on Narcotic Drugs. After all, there were still too few international agreements in the world and I would not be happy to see my own country abandon one of them. Furthermore, it is reasonable to assume that an international organization brings together the best experts on the subject and therefore their decisions are likely to be right. But in fact the story of the development of international controls is complicated and not without its doubtful aspects.

It was at the International Opium Conference at the Hague in 1912 that it was first suggested that there should be regulations for the control of Indian hemp (as cannabis was called in those days). At the second Opium Conference in 1924 the Egyptian delegate presented a strongly worded statement, containing many unproven scare-stories and exaggerations about the consequences of taking cannabis. The British and other representatives felt that not enough was known about this drug to introduce complete prohibition at a conference called to devise measures to control opium, but the Egyptian delegate retorted that the only reason why these nations delayed was becausecannabis did not affect the safety of Europeans.

The British objection was overruled and controls on cannabis were instituted for the first time. Ten years later a new international commission decided that information on the effects of cannabis 'still leaves much to be desired' and set up a new committee to study the whole problem again. But before it could complete the inquiry, the war broke out and the League of Nations ceased to exist. After the war the UN Commission of Narcotic Drugs decided not to appoint a special committee on cannabis. In 1954 a WHO Expert Committee advised the Commission that cannabis had no medical value, that 'its use eventually leads the smoker to turn to intravenous heroin injections' and concluded that 'cannabis constitutes a dangerous drug from every point of view, whether physical, mental, social or criminological'. Later statements by the WHO have modified considerably the strong language used in this document. Even at that time the Narcotics Commission decided that the new international agreement should have a special section (later named Schedule IV); this was to be a list of drugs which allowed signatory countries to decide whether to permit their use for medical and scientific purposes.

Britain signed the 1961 Single Convention along with sixty-four other countries. It is a strange document. The preamble refers exclusively to addictive drugs, but their own expert advisers had noted that cannabis was not addictive. The presence of cannabis in Schedule IV is to be explained by its obsolescence in medical practice rather than by its intrinsic danger.

No history of the development of the international control of cannabis would be complete without some mention of Mr Harry J. Anslinger. For several years before the US Congress passed the Marihuana Tax Act, there was a publicity campaign against cannabis by the Federal Bureau of Narcotics under Anslinger's direction and leadership. No story was too alarmist for this reformer. The marihuana user was said to be a violent criminal given to rape, homicide and mayhem. He also said that the drug led to insanity and to heroin addiction (although he had originally denied this possibility when giving evidence before the Senate Committee on Finance). Indeed Anslinger (1961) takes credit for many of the myths that still circulate about marihuana.1

The American law was passed on the grounds that marihuana was a drug that incited its users to commit crimes of violence and often led to madness. The Federal Bureau later boasted that it had destroyed 60,000 tons of marihuana. But Anslinger's influence as a hyperactive reformer went far beyond the boundaries of the United States: He was the American representative at many international meetings and at others he was able to exert considerable pressure on the delegates as the Commissioner of the Treasury Department's Bureau of Narcotics. It was also well known that the main financial support for these international organizations came from the United States.

Anslinger's moralist evangelism was bound to affect the representatives of other countries. Notices and warnings were regularly circulated by the Federal Bureau of Narcotics through the UN Commission and to the police forces of the world through Interpol. He arranged for special publicity to be given to the many horror stories emanating from Egypt.2 When he retired his work was carried on by Mr Giordano, one of his most active disciples, as head of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics. This came under the US Treasury Department because it was intended to be a minor tax office, but it soon grew into a large bureaucracy. Later it was combined with the Bureau of Drug Abuse under the Department of Justice.

These activities have not gone unnoticed. Professor Lindesmith (1965) has objected to the manipulation of various medico-legal reports by the Narcotics Bureau, and the President's Judicial Advisory Council criticized the activities of the Bureau in 1964. Maurer and Vogel (1967) complain that marihuana 'has received a disproportionate share of publicity as an inciter of violent crime'. The inclusion of cannabis into an international agreement mainly concerned with opiates and cocaine was due to the efforts of one determined man, combined with inadequate research methods in the countries where the drug was most prevalent and the ignorance of other delegates from countries where cannabis at that time was largely unknown.

Many people including Government spokesmen have assumed that the British law on cannabis cannot be altered as Britain is a party to the 1961 Single Convention. But article 46 of the Convention states that any signatory may denounce it unilaterally after six months' notice. It is also open to any country to propose amendments. Nonetheless it is an agreement accepted by most countries in the world after a great deal of discussion and hard work. The British representatives are surely quite right to be most reluctant to do anything which might weaken an agreement which controls the production and distribution of opium and other dangerous drugs.

The Dangerous Drugs Act 1965 and 1967

The 1965 Act implemented the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, 1961, which regulated the distribution of cannabis, cocaine, opiates and related narcotic drugs. It made importation, manufacture or cultivation of cannabis illegal and limited the distribution of these drugs to cases where they were prescribed by medical practitioners. As cannabis is rarely employed medically in this country and is virtually never prescribed, in effect all possession was illegal.

The concept of 'possession' can lead to legal ambiguities. There is some doubt if a person is guilty of the offence of possession if be doesn't know that he has the drug, which might have been dumped in his coat pocket without his knowledge or left hiddendn his home by the previous occupier. There is also some doubt in law if a person can be said to possess a drug when all the police can find in the lining of his pocket are trace elements which can hardly be measured. There is also doubt if a person is in possession of a drug when he has just consumed it, especially as it is very difficult at present to detect the presence of cannabis in the body.

Section 5 made it illegal to permit the smoking of cannabis on any premises and there have been several cases where private houses have been entered and searched, and householders have been arrested and imprisoned. Anyone concerned in the management' of the premises was also liable. This is an absolute liability' which meant that the landlord or manager was still guilty, even if he was unaware that the premises were being used for smoking cannabis. In a recent case Stephanie Sweet was the tenant of a farmhouse near Oxford and sub-let it out to students, some of whom were arrested for smoking pot there. Miss Sweet had not visited the house for several weeks and had no idea what was going on. Nevertheless she was found guilty under this section of the Act and the case had to go as far as the House of Lords before this decision was reversed. Absolute offences are rare in English law, being confined mainly to offences like selling impure food or serving drinks to minors. The wording in section 5 was modelled on an old provision about opium dens and it is not certain whether the original framers of the Act intended to create another absolute offence as regards cannabis.

An infringement of any of the provisions of this Act rendered the offender liable to a fine of up to £1,000 and imprisonment for up to ten years. The penalties were originally introduced in 1920 to deal with traffic in opiates; they were increased in 1923 and remained virtually unchanged until the new legislation. The maximum sentences were the same for cannabis as for heroin and other much more dangerous drugs. It was often argued that the high penalties for possession were justified because it is difficult to catch the trafficker in the act of selling cannabis and it is usually only possible to find him in possession of a large amount. It is sometimes stated that these high penalties are required by the international agreement, but this is not true. The Single Convention obliges signatories to penalize possession, but it leaves it to each individual country to decide the penalties that should be imposed.

The main provisions of the Dangerous Drugs Act, 1967 was to restrict the prescribing of the drugs named in the 1965 Act to doctors working in treatment centres. Lord Stonham stated on behalf of the Government3 that 'the bill is concerned with addiction to hard drugs, and particularly with heroin and cocaine addiction'. Just the same, cannabis was also included under its provisions. Both these Acts really were dangerous pieces of drug legislation because they confused heroin with cannabis. The first drafts of the new drugs law again classified cannabis and heroin as if they were equally dangerous, but following strong protests from the Advisory Committee on Drug Dependence, they were put into different categories.

The New Legislation

The 1965 and 1967 Dangerous Drugs Acts were concerned only with drugs controlled under the international Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs. Other Acts were passed to control other drugs. The Government felt that the existing legislation was co-ordinated and inflexible. The new legislation repeals and replaces all existing drugs laws. The emphasis of the new Misuse of Drugs Bill is on speed, so that the Home Secretary can deal with any new development of misuse that may arise.

The Bill gives comprehensive control of the manufacture, supply and possession of all drugs which may be misused. These are separated into three categories according to the Home Office's idea of their gravity.

Class A includes heroin, opium, morphine and other narcotics. It also covers LSD and injectable amphetamines which for the first time come under a control as strict as heroin. The group also includes some drugs not used in medicine, such as STP, DMT and DET, which have not been controlled before. It also covers cannabinol and T H C.

Class B controls six narcotics and five stimulant drugs of the amphetamine type, such as Drinamyl (purple hearts), Benzedrine and Dexedrine. It also covers cannabis and cannabis resin.

Class C comprises nine named amphetamine-type drugs which are considered to be less dangerous.

An outstanding feature of the Bill is that for the first time in British drugs legislation it distinguishes between unlawful possession and trafficking which public opinion regards as deserving the severest punishment. Penalties on indictment for possession have been reduced from the maximum of ten years (which has not been used by the courts) to a range of sentences varying with the drug involved. Penalties for trafficking, supply or smuggling of all Class A and B drugs are raised to fourteen years and an unlimited fine. The same maximum penalty is provided for the cultivation of the cannabis plant.

For possession of a Class A drug like heroin, the maximum sentence is seven years or an unlimited fine or both; for the possession of a Class B drug, which includes cannabis, the maximum penalty is five years or an unlimited fine or both. Possession of a Class C drug gets a maximum of two years or an unlimited fine or both. On summary conviction the maximum penalties are: Class A — twelve months or £400 or both; Class B — six months or £400 or both; Class C — six months or £200 or both.

Another change from the old Act is that occupiers and persons managing premises are no longer absolutely liable for cannabis use on their premises. The onus is now on the prosecution to show that drug use was knowingly permitted. But the Bill extends the scope of the law so that occupiers and managers are now liable if they permit drug transactions. The new legislation, however, makes it possible for premises to be used for smoking cannabis for research.

The Bill preserves the existing powers of arrest and search, which were the subject of consideration by the Deedes committee. Thus the power of statutory search, which first appeared in the 1967 Act, is to be continued despite criticism of the way these police powers are being used.

The Home Secretary is also given wide powers to ban a doctor from prescribing drugs when a tribunal has decided that he has been over-prescribing. But as cannabis is hardly ever prescribed, these regulations will not affect pot smokers. The Home Secretary can also add to the list of drugs, or change the category of a particular drug from one class to another by regulations, subject to the approval of Parliament. An advisory council and a committee of experts will be set up to assist the Home Secretary. These bodies — with tribunal procedures for erring doctors — are offered as safeguards against the wide powers the Bill gives the Home Secretary.

The alteration in the maximum sentences for cannabis will have very little effect as the new penalties are higher than the courts sensibly impose. It seems that the Government has accepted that there should be some legal indication that heroin is more dangerous than cannabis, but both should be subject to heavy penalties. It remains to be seen if the change means that the police will concentrate on the dealer and show less enthusiasm for arresting the ordinary user of cannabis. With a maximum penalty of five years, possession is still far more than a technical offence.

The Number of Offenders

The total number of persons convicted under the 1965 Act in 1969 was 6,095; of these, 4,683 were convicted for cannabis offences. The total number of persons convicted for all offences under the various Drug Acts was 9,857 in 1969, so about half of all offenders were penalized for using cannabis. Most of the other offences were for possessing amphetamines. There has been a steep rise in the number of offences involving cannabis from 17 in 1946 to 205 in 1954, to 4,683 in 1969— an increase of 52 per cent over the previous year. No doubt part of this growth is due to additional police activity, but most people would agree that there has been a tremendous increase in cannabis use in the last few years, especially among the young. Originally most of the offenders were immigrants but in recent years over half of the offenders have been of United Kingdom origin. Of the 4,683 convictions, 4,094 were for unlawful possession, 122 for unlawful import, 147 for unlawful supply, 225 for permitting premises to be used for smoking cannabis, 49 for procuring and 46 for other offences. Five People were convicted for cultivating cannabis in England, but only a few plants were found. In 1969 the police and customs seized 544 kilogrammes of cannabis herb and resin, compared with 1,125 kilogrammes in 1968. The amount seized in the last two years would makemore than 1,000,000 joints. The confiscated cannabis came from twenty-five different countries.

Over two thirds of all cannabis offenders did not have any convictions of any kind for non-drug offences. About a quarter of all cannabis offenders were imprisoned; about 17 per cent of first offenders were sent to prison (or borstal, detention centre or approved school).

A special analysis was made for the Wootton Committee, which analysed all cannabis convictions in 1967 according to the amount of the drug found on the offender. In fact nine out of ten of all offences were for possessing less than 30 grams. Of the 2,419 people who were convicted of possessing less than 30 grams of cannabis, 373 (15 per cent) were imprisoned - the Wootton committee felt that this proportion was far too high. The same analysis showed that 1,857 persons without previous convictions for any type of offence were convicted of possessing less than 30 grams of cannabis; 237 (13 per cent) of these first offenders were sent to prison - 119 of them were aged twenty-five or under.

It appears that cannabis smokers are not criminals in the usual sense of the word. In general they do not commit other crimes and most of them are young first offenders. The vast majority have less than 30 grams in their possession when they are arrested. Of the 2,419 persons convicted of possessing this small amount of cannabis in 1967, only 191 (less than 8 per cent) had previous convictions for drug offences. This may suggest that first offenders give up taking cannabis after a conviction for possessing; a more probable explanation is that the convictions only reflect a very small proportion of the total number of cannabis users and detection is mostly a matter of chance.

Illicit Sources of Supply

In 1966 a report by the Economic and Social Council of the Permanent Central Narcotics Board observed that the illegal traffic in cannabis was the most widespread of all. The quantities of cannabis seized varies widely from country to country and depends more upon the efficiency of the customs officials than the amount actually leaving or entering a country. There is no doubt that the smuggling is international with variations in the degree of organization.

In Great Britain the annual volume of seizures had not increased very much between 1957 and 1967. There have been a few cases where people were caught bringing in very large supplies, but most seizures have been of small amounts from seamen and people returning from holidays abroad. The annual report from the Home Office to the United Nations for 1965 noted `the apparently new practice of individuals from different groups of cannabis users making visits to Asia via Europe, often by hitch-hiking, with the object of purchasing supplies for resale to United Kingdom users known to them'.

The traffic in cannabis had been for many years linked with ports and dockland districts and was destined mostly for seamen, musicians and immigrants. By 1960 the use of cannabis had spread beyond these groups and was no longer restricted to inner London. There was also a social expansion because the drug was now being used not only by musicians and artists, but by a significant section of the population. Even so, there are no signs that criminal gangs have started large-scale smuggling of cannabis although this has for a long time been a possibility. As things are at present it would not be worth the while of a bigtime crook. Supplies are plentiful and there are so many sources of supply that it would be impossible to create a monopoly. If the police were Very successful and caused a scarcity, thereby putting up the black-market price, a large organized criminal group might enter the field. But at present cannabis is a business for the small operator.

Recently three men were discovered smuggling in 414 pounds of cannabis resin. They were each imprisoned for five years and fined £2,000; in default of the fine, they will serve two more years. They were breaking the law and no doubt would have made a lot of money from selling the hashish if they had not been caught. Therefore most people would agree that they deserved to be given a heavy fine and sent to prison. Smuggling on this large scale seems to be very rare. Of the 2,731 convicted of cannabis offences in 1967, only 49 (1.8 per cent) were found guilty of possessing more than one kilogram.

The emotion and hatred engendered by the idea of an evil pusher trapping young people and tricking them into becoming drug addicts is misplaced. Many people professing a liberal attitude to young people and drugs have suggested decreasing the penalties for people who take cannabis and increasing the penalties for those who sell it. But this extravagant hatred of the pusher is based on a myth which is misleading. The very word 'pusher' is emotive and conjures up the picture of the evil man tricking innocent young people into trying a drug with the certain knowledge that once they have been trapped in this way, they will be hooked for life. This picture is not true even for heroin, and is a long way from the truth for cannabis which is not an addictive drug.

Furthermore it is not true that heroin and pot are usually obtained from the same supplier. Nearly all cannabis is smuggled into the country in small amounts. Very little heroin comes from abroad; the main source of illegal heroin comes from addicts who have managed to persuade their doctor to prescribe more than they need and they sell this to people who have not yet registered at a treatment centre. Pot smokers and junkies do not mix. The average user of cannabis does not know anyone who takes heroin and he certainly would not know where to get a supply.

The new Act awards the same penalties for selling heroin or cannabis. Thus it perpetuates two of the common myths — that the problem can be solved by attacking the dealer in drugs, and that heroin and cannabis are obtained from the same supplier.

People who buy and sell pot do not behave like the ordinary man's idea of the mythical pusher. An experienced pot smoker knows where to go for a new supply and probably has a regular dealer. Knowing that the police set traps and use agents provocateurs, the sensible smoker realizes that this is a dangerous transaction and will only deal with someone he can trust, or at the very least with someone who has been recommended by another user. Pot smoking is a gregarious activity and so a person who has just begun smoking will probably be given or sold a small amount by a friend. For quite a time the user will get his supplies from others in his circle and will not have to find a supplier dealing in cannabis for profit. Eventually he may want to get his own supply and then he finds out from his friends where to go. But even if he does not get this friendly advice, he can probably find a small-time dealer by asking around.

Of course there is always a risk that a person buying an illegal substance may be swindled because the seller will know that the cheated buyer will not complain to the police. Sometimes the buyer is required to pay in advance and the seller goes away to get the hash, and disappears for ever. On other occasions the buyer finds he has been sold pot which is of a very poor quality or has been adulterated to make it go further. On more than one occasion the police have arrested someone for possessing cannabis, but on analysis it turned out to be a harmless substance such as herbal mixture although the user was even more surprised than the police to be given this information.

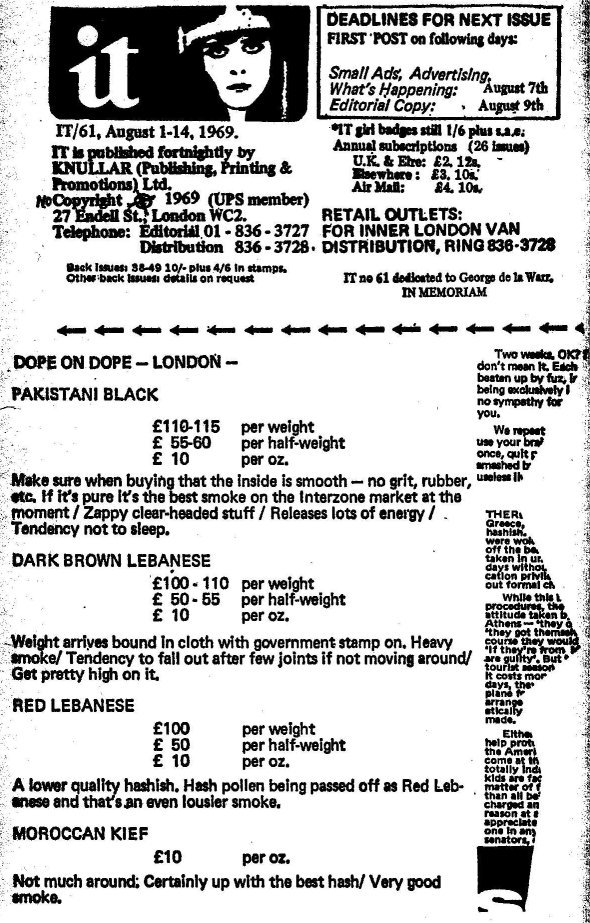

Quite often the sale of cannabis is a social occasion with the seller arriving at the client's home with his scales and supplies, and the buyer looking it over and talking knowledgeably about the quality and the current market rate. One of the services provided by IT is a periodical run down of the state of the market (see illustration taken from page 2 of /T/61, August 1969). As in all business ventures, legal or otherwise, there are some sharks who will take advantage of their customers and there are others who are anxious to establish a reputation for fair dealing so as to create the demand for more business. What one will not find is an evil pusher looking for innocent children to turn on and corrupt. Most of the dealers are small-time operators who can sell all the cannabis they can get to friends and acquaintances, and who would not be interested in selling heroin, nor would they know where they could get any to sell.

1. 'Much of the irrational juvenile violence and killing that has written a new chapter of shame and tragedy is traceable directly to this hemp intoxi. cation ...

'As the Marihuana situation grew worse, 1 knew action had to be taken to get proper control legislation passed. By 1937, under my direction, the bureau launched two important steps : first, a legislative plan to seek from Congress a new law that would place Marihuana and its distribution directly under federal control. Secondly, on radio and at major forums, such as that presented annually by the New York Herald Tribune, I told the story of this evil weed of the fields and riverbeds and roadsides. I wrote articles for magazines; our agents gave hundreds of lectures to parents, educators, social and civic leaders. In network broadcasts I reported on the growing list of crime, including murder and rape. I described the nature of Marihuana and its close kinship to hashish. I continued to hammer at the facts.

'I believe we did a thorough job, for the public was alerted, and the laws to protect them were passed, both nationally and at the state level.' — The Murderers by Harry Anslinger and Fulton Oursler.

2. In 1960 the United Arab Republic stated that there were 900,000 Egyptians addicted to cannabis, but in 1964 the number given was under 100,000. A 1965 United Nation Document E/CN.7/474/Add.2 Drug Abuse in the Middle East' commented on the information supplied by the UAR delegation: 'Earlier accounts have gone so far as to describe it as a plague or national calamity, without, however, producing precise information and references to support these judgements.'

3. Hansard, House of Lords, 20 June 1967, col. 1,172.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|