MARIJUANA IN MOROCCO

| Books - The Psychedelics |

Drug Abuse

MARIJUANA IN MOROCCO

TOD MIKURIYA

Morocco, on the north coast of Africa directly across the Strait of Gibraltar from Spain, is the closest country to Western Europe where marijuana is extensively grown and used by the inhabitants. It is a poor country, with the per capita income less than $200 per year. Morocco obtained its independence from Spain and France only in 1956. Marijuana is grown in quantity by the mountain-dwelling "unacculturated" Berber tribes in the Rif Mountains and is sold in the partially 'Westernized coastal plains.

Kif is the Moroccan word for marijuana. It is a general name that covers all preparations smoked. These preparations are different from those encountered in North America in that only the blossoms of the mature female plant are used. Another difference is that the blossoms are always mixed with an equal amount of tobacco. Its use is widespread throughout the country among adult males, as it has been for centuries.

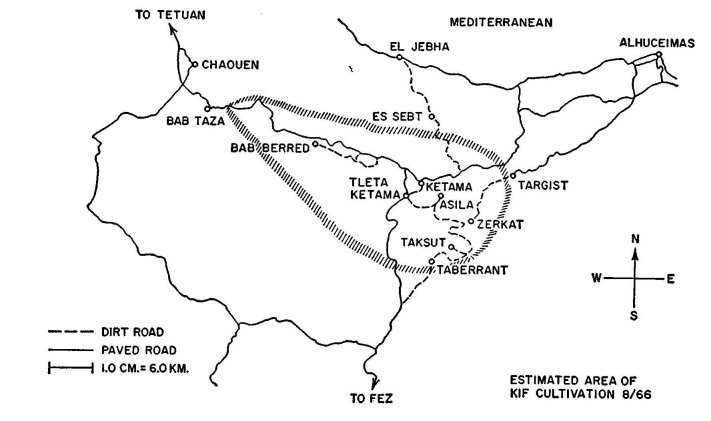

From August 20-23, 1966, I had the opportunity to travel in the Rif Mountains area in the province of Alhucemas, Morocco. During this period, I had the opportunity to observe the cultivation of kif, particularly near the towns of Ketama, Taksut, Taberrant and Tleta Ketama. Introductions and translations were facilitated by the Director of the National Co-operative of Artisans for the Province of Alhucemas. He is responsible for supervising the operations of handicraft manufacture for this province. As handicraft manufacture happens to take place in the kif-growing area, I could observe the traditional activity as well.

With proper introductions by an individual occupying a position of some importance locally, I found the people quite hospitable and friendly. During my visit I had the opportunity of sharing various native dishes from the communal bowls in the center of the traditional circle. The people were quite open about answering any of my many questions. At the same time, they were fully aware of the "illegality" of kif. Even the children that I met knew that it is forbidden to take kif into the lowlands. During this visit, I talked with law-enforcement officials and local farmers, as well as with village officials.

The Rif are a chain of mountains stretching across the northernmost area of Morocco. Except in the highest elevations (7000-8000 feet), they are generally hot and dry. The terrain is quite rugged. The slopes are steep and rocky and often drop several thousand feet to the narrow canyons below. In the central region of the mountains there is a small plateau. The village of Ketama is located at its western edge.

The area surrounding this central plateau is strongly reminiscent of many areas of the western United States, such as northern California and Colorado. There are small, rather scanty strands of fir trees on the upper elevations. In the lower areas, the vegetation is mostly low shrubs and grasses. During the short winter, from November to March, there may be as much as two or three meters of snow at the higher elevations.

Kif is grown in an area in the Rif Mountains approximately one hundred fifty kilometers northeast of Tangier. The kif-growing area itself is a triangle with the base an imaginary line drawn east to west from a point approximately ten kilometers west of Targist and ending about ten kilometers east of Bab Taza. The legs of the triangle converge in the area of Taberrant to the south. The area included in this triangle is approximately one thousand square kilometers. Ketama is reputed to be the center of the growth area, while the town reputedly producing the most kif is Asila, to the southeast.

While the main roads are generally well-surfaced macadam, the grading is poor, because hand tools are used for construction instead of earth-moving equipment. These roads are usually kept open all year. There are, however, just four or five towns actually located on first-class roads. Many of the towns in the area are located on extremely poor dirt roads leading back into the hills. These latter are so formidable that it is not possible to drive any faster than fifteen or twenty miles per hour, at best. At several spots along these rural roads, I saw gangs of workmen attempting to maintain and improve the road with pick and shovel. The roads wind along the faces of steep cliffs, and there was evidence of frequent slides.

There is little, if any, rural electrification. Most of the towns had no electric or telephone lines leading to them. When telephones and electricity were in evidence, they usually ran to the small outposts of the national police. Outposts seemed to be located in each small town along the main road, but only sporadically along the secondary roads.

The villages in this area that are off the main road bear very little resemblance to the villages along the main road or in the lowlands. They appear not to be villages as such, but rather collections of houses spaced within half a kilometer of one another in these very steep canyons. There were no interconnecting roads for vehicles, only winding donkey paths. Many villages are inaccessible for cars, and donkeys are the only means of transport.

This area is populated chiefly by various Berber tribes. In the villages, many of the people cannot speak any language other than their native dialects. They often cannot speak Arabic. In most towns, however, Arabic is spoken, and occasionally French or Spanish is used as a secondary language. The language barrier may be the reason that they are a people not easily assimilated into the cultures of the "European" cities of the coast or the "Arabic" cities of the plains and foothills.

For perhaps a thousand years the tribes have rather successfully resisted outside influences from a succession of invaders that range from the ancient Phoenicians and Romans to the modern French and Spanish.

The Berbers seem to have a strong sense of private property and know exactly whose field is whose. The various families through the generations have taken much effort to build and maintain the neatly terraced fields that sit precariously on the steep, rocky slopes.

Throughout North Africa, these people are referred to as "The Berber Problem" because of their resistance to assimilation. Often along the road and again in the isolated villages, I saw men carrying ancient rifles on their backs. When I asked about this, I was told that they weren't really rifles, but were "just part of tradition."

Taksut,is located in one of the myriad steep, craggy canyons so characteristic of the central Rif Mountains. The barren, gray mica-schist walls tower around the narrow, steep floor of the canyon. The fields are terraced with local stone in order to create level land for the cultivation of crops. Small, flat-roofed adobe houses are spaced several meters apart and surrounded by the family fields.

Taksut is not on the rather complete Michelin road map. It is located about seventy kilometers southwest of the town of Targist. The town is at the end of a spur of a road so primitive that only large trucks and four-wheeled vehicles can pass safely. During snowfall in the winter, it is isolated from the rest of the world. The road comes to an abrupt rocky end on the outskirts of this town. There are no streets—only donkey paths.

The center of town is just across a footbridge and up through some large boulders. This is just a small, unpaved space around which there is a little cluster of houses and two tiny general stores. Throughout the town, the buildings are often built around the boulders or perched on top. There is a small stream nearby. There is no city hall, post office, or other evidence of government services in this town. There is no telephone or electricity and no evidence of a modern sewage system. No health services are provided.

As one goes from the center over the tortuous trails, the outlying houses are surrounded by larger plots of gronnd. The fields are more rock than dirt, although much work has gone into clearing the rocks. The terraces of these fields are made from the cleared rocks.

The fields around Taksut are planted about 5o per cent kif. The remaining crops are corn, wheat, legumes, and truck-garden products such as tomatoes and melons. Besides agriculture, the town is supported by artisans working in the home. Taksut has no one specialty in handicrafts, but rather depends on the work of several individuals who specialize in making such items as leather hassocks, leather purses and handbags, rugs, pseudoantique firearms, and hand-tied rugs. The population of this little town/valley was estimated by some of its residents to be between three and five hundred.

The economy of this area is almost solely supported by the cultivation of kif. In the central areas of growth, it is the only crop. The individuals involved in kif production in these areas must even purchase staple goods rather than grow them themselves. In the peripheral areas, however, more of the other crops are in evidence. These are apparently both for local consumption and limited cash crops. Although no accurate estimate can be made of the total area and yield, the area planted in kif is probably in the thousands of square kilometers, with an output in the range of thousands of kilograms per square kilometer of marketable product.

The corn and wheat crops are quite poor in quality, with yields of perhaps less than one bushel per acre. Concerning the yield of kif, the average is estimated by the local fanners as being two kilograms per square meter of marketable product (dried tops and stems; the leaves are not included). The farmers receive five dirham (one dirham equals twenty cents) per kilogram of this product from the individuals who come up from the lowlands with trucks to take the product for distribution in the cities. The selling price in the cities jumps to between fifteen and fifty dirham per kilogram. Products refined further, those in which the blossoms have been separated from the stems and seeds, may bring up to two hundred dirham per kilo. These blossoms are mixed with an equal amount of high-grade tobacco, grown primarily in other sections. I did not see any cultivation of this tobacco in the area I visited.

Kif is planted in this high, mountainous region early in March, shortly after the spring snows have thawed. Male plants are culled when the plants are old enough for sex to be determined. It is harvested during the month of August and in early September, when the blossoms are ripe but before their plants go to seed.

The government attempts to practice a policy of containment. While it prohibits new areas of kif production, it allows those already in production to be maintained. The nature of this control is shown by the fact that in Taberrant, a comparatively inaccessible town, the national gendarmery had destroyed several unauthorized acres of kif growing there shortly before my visit.

Along the main road, at least at Bab Taza, Bab Berred, Ketama, and Targist, there are barricades and national gendarmery outposts. These outposts have telephones and sometimes short-wave radios for intercommunication. When I inquired what these were for, I was told that at night all trucks that pass through this area are searched. I was also told that most of the Moroccans who pass through the area have their luggage inspected at various bus stops. In my travels, however, I never saw this happen.

Along one of the dirt roads, I saw a weighing station, where some farmers had brought the dried kif to be picked up for shipment to the cities of the lowlands. I was not, unfortunately, able to find out more about the transportation arrangements. The regulation of kif is apparently a very complicated matter, handled by the Moroccan government in a way that seemed incomprehensible to me. It is apparent that large vehicles must be used for transporting the large amount of kif grown to the areas of consumption, but the exact arrangements for getting the kif to market were unclear. There apparently must be some way of obtaining government "approval" to enable these vehicles to take the crops to the cities of the plains. The cultivation of kif in Morocco has gone on for hundreds of years. Thousands of kilograms are consumed each year.

A situation of chronic unemployment in Morocco has been aggravated by the migration of Berbers with no industrial skills and who are not assimilated into either the Arabic or the European culture. In 1965, Casablanca experienced riots that necessitated seven days of martial law. These riots took place primarily in the slum areas on the edge of the city, which are populated mostly by "displaced" Berbers.

I was told that five years ago there was an attempt to bum kif fields in the mountains, but that this government effort was met with armed opposition. The government ceased its effort when it became apparent that this would be a long and costly struggle. The rugged terrain and the poor communications made effective resistance to the government campaign quite easy. In addition, pressures from people in the cities who traffic in the huge quantities of kif were not insignificant.

The government also realized that depriving the Berbers of their chief, and often sole, cash crop would drive them from their marginal rocky land, further inflaming the unemployment problems in the cities.

The above observations and inferences illustrate the complexity of the problem of kif production in Morocco. The barren marginal soil on which little else can be grown, combined with the rugged terrain, poor roads, poor communications, and the tradition among these people of resisting outside influence, interact with the pressure of large vested interests in the transportation and distribution of kif as well as with a chronic unemployment situation. It is therefore unlikely that any significant reduction of kif cultivation can be effected. The situation of stalemate between the central government and the Berbers of the Rif will probably continue for the foreseeable future.

Kif is widely smoked by males throughout Morocco. It may have been introduced by one of the succession of Arab conquerors from the eastern Mediterranean countries during the seventh century A.D. Despite the efforts of various Arab, Spanish, and French rulers to suppress kif or at least tax it, its growth and use have continued to flourish.

Prohibitions against kif, according to some of the older kif users, or kiefe, were fewer during the Spanish-French partitioning of Morocco. For many years, it was taxed and concessions were allotted for growth and sale. As late as 1954, it was prepared in the form of packaged cigarettes by government-approved manufacturers. The efficacy of control by taxation and monopoly was not too effective, as seizures of contraband kif amounted to between one fifth and one half of the total legal output. The use of kif was finally made illegal in 1954.1

The fact that kif smoking is now illegal in Morocco has the effect of preventing the user from ostentaciously selling or smoking kif in the European sections of the larger coastal Cities. Lack of respect for this recent law is hardly surprising, since the custom of kif use in Morocco has been present for centuries. The use of kif violates no Muslim holy law, which would provide another possibility of social control. By contrast, Muslims patronizing European bars are liable to summary arrest and incarceration; there seems to be a rising concern for the growing number of young men who are becoming alcohol users.

Unfavorable attitudes of the Moroccan Government seem not to stem from a general moral concern, but rather from a point of view that kif smoking may create more economic hardship in a people whose existence is marginal. The use of kif is also a symbol of the traditional order, which must be changed if the goals of Moroccan industrialization and self-sufficiency are to be achieved. Another factor may be pressure on the government from Western European and United States narcotics-law enforcement agencies to stop the growth and use of kif. It is said that the present king is not as well liked as his father, because he is attempting to suppress or discourage the use of kif.

As in Western Europe, England, and the United States, the present incidence of kif smoking is impossible to estimate, due to the fact that it is illegal. Another stumbling block to estimation may be a reluctance to admit to a Westerner that one is at variance with practices of an alcohol culture that has (and economically still does) occupied a position of dominance. In addition, there are a substantial number of Moroccan men who have tried it at some time in the past, but have never become regular users. A group of users in the small town of Targist claimed that 20 per cent of the males are currently regular users, and that 90-95 per cent of the men have used kif at some time in that town. When asked about use among women, the answer almost universally elicited, both in rural Targist and urban Tangier, was, "No women use it around here, but I have heard that some use it in [some other town or area]." In the rare contacts with Moroccan women, they answered that it was forbidden to them and that if they were caught ,using kif they would be beaten.

In Tangier, there was little evidence of kif smoking in the European sections of town, but within the Arab quarter (kasbah or medina), there was little to suggest non-use. Most stores selling handicraft sold the traditional pipes. Several small shops sold just pipes and pouches for the use of kif.

As one might expect, contacting Moroccan users is simple compared with a similar task in the United States, as it is far less dangerous to smoke kif in Morocco than to smoke marijuana in the United States. One need only ask about kif in a general way. If the man is a user, the chances are that he will smilingly proffer the traditional su si pipe, which has a long wooden stem and a small clay bowl, happy to meet a foreigner who shares this common interest. If he is not a user, his reply carries with it the effect of one who does not use tobacco in the United States. He will usually admit to having tried it at one time, but not finding it to his liking.

The customs surrounding the use of kif in Morocco appear to be of a secular-social nature in contrast with those of the Hindu holy men of India described by Carstairs2 as using cannabis as a religious sacrament. In Arab sections of the cities, kif smoking is almost as ubiquitous as the highly sugared, mint-flavored tea that accompanies all but the most perfunctory of conversations.

The methods of kif smoking are quite different in Morocco from the ways in which marijuana is used in the United States. In the United States, use patterns, described by Becker3 and Walton4, are based on fear of discovery and avoiding waste of this precious commodity. By contrast, the Moroccan user is not concerned with waste, because kif is cheaper than tobacco. It is the custom to have the person who offers a su psi pipe load it, light it, and wipe the mouthpiece before handing it to the recipient. The recipient inhales the smoke deeply, but promptly exhales. He does not pass the half-smoked pipe to another, but continues to smoke leisurely until the first crackle is heard, as the heated ash approaches the bottom of the bowl. He then expels the remaining burning plug by blowing into the pipe. He either cleans, refills, relights, and passes the cleaned pipe to the next person, or passes the cleaned pipe and allows the recipient to use his own supply. In a group, often more than one pipe is used.

A similarity between the practices of United States marijuana smokers and the Moroccan kif smokers is the physical arrangement of the groups. Both groups tend to sit in circles, either around a table or else lounging about on the floor on cushions. This circular configuration may be to facilitate the passing of the pipe from one to another, or, wildly speculating, perhaps is a surviving vestige of the archetypal tribe around the communal fire. This may, however, be only coincidence, since lounging about on low cushions in a circle is usual practice in the Moroccan household.

Also similar was the content of the conversation during sessions of kif smoking. As with the United States user, his Moroccan counterpart often spins stories of legendary types and preparations of kif he has sampled, seen, or heard about. There were tales of oral preparations of cannabis combined with other substances purportedly given to children of mountain tribes to assuage the cold of night and help sedate them for the evening. A potent substance for eating, called amber, was described. A recipe for a special kif sweetmeat, majoon, was described. Majoon is usually compounded from powdered blossoms, sugar, honey, cinnamon, and almonds. It is baked in the hot sun until it reaches the consistency of a moist fudge. It is eaten by the "fingersful." The use of oral preparations was not observed.

Hashish, a more concentrated preparation, is much less common, but nevertheless widely known. Unfortunately, there was no opportunity to observe its manufacture during my short stay. One man in a village seems to be the local expert in its manufacture. Such a man exists in Ketama, the town in the middle of the growth area, but when I was there, he was out of town attending his wife, who expected to give birth to a child shortly. From descriptions by the,,residents, hashish is made from the blossoms and the leaves of the plant and takes at least two days to make, with many stages of cooking. This process differs from Norman Taylor's description of the manufacture of charas by harvesting pollen and resin by beating the blossoms on leather aprons.5

Terminologies for the effects and use of cannabis seemed to be relatively simple, considering its high incidence of use and long history of consumption. Hashashut means to feel the full effects of the cannabis. This term also appears to mean overdose. Moroccan users recognize both pleasurable and unpleasant effects of cannabis. Fehrdn denotes having a pleasurable effect, a "good trip" in contemporary United States terms. Teirala means an unpleasant result, or unpleasant side effects, a bad trip. Unpleasant effects are described as related to overdosage. Nashat is a group of kif smokers. Few solitary kif users were seen. Its use appears to be primarily of a social nature, as it is in the United States. Nashatu refers to such a group lasting twenty-four hours. Douach means to become intoxicated with kif, or to "turn on."

The complexity of attitudes toward kif was illustrated by the behavior of my host and guide. This man, of some local importance in the province of Alhucemas, showed quite varying responses to the topic in different circumstances. When with men who were his social inferiors but not his subordinates, he would smile and speak affably of kif as if it were a fine wine, an experience that all should enjoy. He would refer to himself as a heavy user and describe the pleasure he derived. By contrast, when he was with people of like or superior station, he would minimize, but not deny, his use of kif. He would then portray himself as a light or intermittent user. One of his friends, a caid (mayor or chief) of a small village, showed a similar "selective" attitude. During lunch with him and the lesser officials of the town, the lesser officials smilingly admitted to regular smoking of kif, but the caid denied any use at all. After lunch, as we drove over the winding mountain roads to the next town, the caid, who accepted the proffered ride, volunteered that he used it at home regularly. He said it would not be proper to speak of such things in front of his employees. A parallel might be seen in the attitudes in contemporary America toward alcohol.

The chief differences in the use of cannabis between the United States and Morocco are smoking technique, pharmacology, and formality. Although kif is more readily available and cheaper in Morocco, it appeared from sessions with the Moroccan users that while much more is smoked than in the United States, much less is actually ingested. The practice of inhaling but not holding the breath might decrease significantly the amount of active principle absorbed. Combination of kif with tobacco would also decrease the amount of cannabis actually ingested. These differences in technique make comparison of dosage difficult.

Tobacco itself seems to play an important role in the smoking of kif. In several of the kif sessions, I would substitute pure kif blossoms for the standard mixture when the pipe passed my way. The response was fairly uniform. The recipient would take a few puffs, wait until he felt that I wasn't looking, discreetly discard the contents, and reload the pipe from his own supply. The respondent indicated only that he preferred kif-and-tobacco. It is hard to know whether or not it was the taste or the psychic effects that determined his preference more. It is certainly possible that the kif-tobacco mixture has different psychic effects from pure kif, as the pharmacological effects of nicotine are not without consequence.

Use of kif in Morocco is certainly less formal than "pot parties" in contemporary United States. In the back of any shop or cafe, the ubiquitous su si pipe can be seen. The Moroccan does not suffer from fear of discovery and prosecution as does his American counterpart.

Although commonly confined to non-European settings, the musicians and dancers in an expensive restaurant for tourists on "packaged" tours would pass the suPsi pipe from member to member. They made no effort to conceal their activity from the audience. The audience was oblivious to this performing nashat. The proprietor, when asked about this practice, first acted as though he could not understand the question. Persistence yielded the reply that the musicians were Berbers, but that "none of the people around here do that."

Several small cafes were observed that sold only the familiar sugared green mint tea, local cakes, and sweets. The patrons devoted themselves to smoking kif and participating in instrumental/vocal renditions of familiar songs. The atmosphere was relaxed and congenial, but not lethargic, in contrast with the familiar noisy ebb and surge of the average United States neighborhood bar.

Morocco is a country in which modern efforts to suppress an ancient habit have only succeeded in making it mildly unrespectable without really inhibiting the use of kif or seriously affecting the customs around its use. It continues to be one of the major socialization devices of the people. Given the Islamic prohibition against alcohol, the character of the Berbers who grow kif, and the economic situation of the country, it seems unlikely that its use will ever be eradicated or even seriously curtailed.

1 Benabud, A. "Psycho-pathological Aspects of the Cannabis Situation in Morocco: Statistical Data for 1956," Bulletin on Narcotics, 1957, 9 (4), 1-16.

2 Carstairs, G. M. "Dam and Bhang: Cultural Factors in the Choice of Intoxicant," Quarterly Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 1954, 15 (2), p. 228.

3 Becker, H. S., Outsiders; Studies in the Sociology of Deviance. New York: The Free Press of Glencoe, 1963, pp. 47-48.

4 Walton, R. P., Marihuana: America's New Drug Problem. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1938, PP. 47-48.

5 Taylor, N., Narcotics: Nature's Dangerous Gifts. New York: Dell Publishing Co., 1963, p. 14.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|