CHAPTER VIII TYPES OF USERS

| Books - The Opium Problem |

Drug Abuse

Along with a consideration of the extent of the problem, its development, and nature, it is important to determine the kinds of individuals affected in order to discover, if possible, for purposes of control any common factors present. Such an attempt at classification for the determination of the types of persons involved may be approached from many angles according to the particular information desired. For example, any or all of such factors as race, age, sex, physical condition, mental and ethical traits, social status, occupation, environment, education, etc., may be covered. Comprehensive classification along any of these lines has a value and may lead to distinctly important findings.

Any of the above classifications may be applied, furthermore, to chronic opium users as of two periods, namely, the period preceding their use of the drug and the period following this use. By an application of such distinctions we should be able to determine both the kinds of individuals who become users and the effects of chronic use upon these individuals. Such a classification would have distinct etiologic and prognostic value and should assist very materially in determining and applying the details of control activities.

It will be seen at once, however, that any such detailed classification into types involves an abundance of material dealing with several aspects of this problem which in previous chapters we have indicated is lacking or is of such a fragmentary nature as to preclude its use for purposes of generalization. In what follows, therefore, we are presenting such data as we have been able to collect bearing on one or another of the factors or conditions affecting those suffering from chronic opium intoxication. In its perusal the reader must bear in mind constantly the incompleteness of knowledge on the subject and the intrinsic value of the evidence submitted as affected by the wide or limited experience of the individual writer, his professional tendencies and the groups dealt with, all of which influencing factors are self-evident in the quotations and references given.

Sex Distribution

Here we find, as in the consideration of other phases of the problem, that the available material is too fragmentary and too strongly influenced by special factors to serve as a wholly satisfactory basis for generalizations. As we have pointed out elsewhere, it is only through studies of long and representative series of cases that we shall be able to reach definite and unassailable conclusions as to the extent of chronic opium intoxication and its distribution by sex, age, and other groupings. In the absence of such desirable data, the following is presented as comprising the best information available to date.

In the section dealing with etiology we have seen what Smith,' 1832, states in his inaugural dissertation on opium as to the predilection of women for these drugs.

A. Calkins-1871.2

. . in the division of sex the women have the majority . . .

". . . The Cyprians who perambulate Broadway by gas-light are reliant upon laudanum in extremity not only, but partial to the same for its stimulating power. Loines reckons that two-thirds of the class become habituated eventually to opium in some form; it may be laudanum, or as likely morphine, going to the amount of 5 grains of the latter for the daily dose. In New York their purchases are made on the Avenues chiefly, and besides they partake habitually and largely of strong liquors. A young man, an apothecary on Union Square, gives similar testimony regarding the courtesans of Savannah. Those accounts square very precisely with the observations of Dr. Quackenbos who remarks further, that the aggregate of instances among women in high place is incredibly large."

O. Marshall-1878.3

Marshall, as we have seen in the chapter on extent, in his survey in the State of Michigan, gives the following sex distribution of .1313 cases,— 510 or 38.8% males and 803 or 62.2% females. These cases, it will be remembered, were collected by Marshall through correspondence addressed to physicians throughout the state and represent the number so reported from 96 towns and villages. In these cases, there would appear to be no factor which might influence unduly the number of either sex reported. They would seem rather to be a fair cross-section of the opium using population of the communities dealt with.

H. H. Kane-1880.4

Kane quotes Bartholow as follows:

" 'A delicate female, having light blue eyes and flaxen hair, possesses, according to my observations the maximum susceptibility.' "

Kane himself states that women outnumber men.

C. W. Earle-1880.5

Earle, in his study of cases in Chicago obtained through interviews with druggists in different sections of the city, states:

"Among the 235 habitual opium-eaters, 169 were found to be females, a proportion of about 3 to 1. Of the 169 females, about one-third belong to that class known as prostitutes. Deducting these, we still have among those taking the different kinds of opiates, 2 females to 1 male. In one family I found the mother at the age of 65 taking one drachm of gum opium each day, and her daughter, at the age of 30, consuming two drachms of the tincture. One lady, aged 50, has taken it since she was 13 years of age. Suffering from some painful sickness during her youth, she was given, by a physician, a box of powders, on which was written 'Morphia'. She had the prescription repeated, and gradually found herself in the power of the seductive drug, from which in all probability, the will never be freed."

In this series it is possible that the relatively large number of prostitutes has increased the proportion of women, but even allowing for these, as the author points out, there would still be a preponderance

of females. His figures show 28.1% males as compared with 71.9% females.

J. M. Hull-1885.°

. . . and as to sex, we may count out the prostitutes so much given to this vice, and still find females far ahead so far as numbers are concerned."

His series of 235 cases, collected throughout the State of Iowa,

shows the following sex distribution,-86 or 36.2% males and 149 or 63.8% females.

T. C. Allbutt--1905.7

"In respect of sex there does not seem to be much difference ; the anticipation that the practice would be found more prevalent in woman is not supported by facts. From my own experience I certainly should have said that the greater prevalence lay on the feminine side ; however, Dr. Mattison, Dr. Levinstein, Dr. Erlenmeyer and other authors of weight, find the figures to run pretty equally between the sexes."

C. E. Terry-1913.8

Terry gives as the sex distribution determined from the cases handled at the health office and through duplicate records from physicians in Jacksonville, the following:—out of a total of 541, 228 or 42.1% were males and 313 or 58.9% females.

P. M. Lichtenstein-1914.9

Lichtenstein concludes from observations on 1000 handled in the City Prison, Manhattan, that males greatly outnumber females.

L. P. Brown-1914.1°

Brown in a study of 2370 in the State of Tennessee, found the fol-lowing sex distribution:-784 or 33.1% males and 1586 or 66.9% females.

C. B. Farr-1915."

Farr, in a study of 120 cases of heroin use at the Philadelphia Gen-eral Hospital, found that 91 or 75.8% were males and 29 or 24.2% were females. He also studied 176 cases of chronic opium intoxica-tion in which other forms of the drug than heroin were used. Of these 94 or 54.41% were males and 82 or 46.59% were females. It is worthy of note that of the heroin users 41 used cocain also and of the cases using other forms of opium 40 used cocain. The types here represented were quite evidently drawn largely from the underworld where, as would be expected, the origin of the condition was mainly evil associa-tion,—hence, both the preponderance of males and the large number using cocain and heroin.

J. McIver and G. E. Price-1916.12

McIver and Price, in a series of 147 cases also at the Philadelphia General Hospital, found that 103 or 70.1% were males and 44 or 29.9% were females. They state in this connection:

"The majority of women were prostitutes, and some few of the men were or had been cadets. A number were notorious crooks and thieves. . . . The majority were dwellers in, or frequenters of, the `tenderloin..'"

M. Craig-1917.13

Craig states that both sexes seem to be almost equally affected.

Special Committee of Investigation Appointed by the Secretary of the Treasury-1918.14

"Contrary to general opinion the committee finds that drug addiction is not more prevalent among females than males. Reports obtained from some parts of the country show that the females outnumbered the males, while in other sections, officials reported a preponderance of males. Taking all factors into consideration, it appears that drug addiction is about equally prevalent in both sexes."

It should be remembered that the above committee did not differentiate between opium and cocain users but based their conclusions on statistics covering both classes. The majority of cocain users seem to be males." Another fact to be borne in mind is that the statistics used were drawn primarily from institutional reports comprised in questionnaires answered by heads of penal institutions, almhouses, health officers, private hospitals and sanatoria.

J. A. Hamilton-1919.'6

Hamilton reports a total of 388 persons received at the Workhouse, Blackwell's Island, New York City, during 1918 for drug treatment, of whom 351 or 90.5 were males and 37 or 9. 5 were females.

S. D. Hubbard-1920.17

Hubbard states that out of 7464 registered at the New York City Narcotic Clinic in 1919, 5882 or 78.8% were males and 1582 or 21.2% were females." The only two drugs dispensed at the New York clinic were morphin and heroin. Dr. Hubbard does not state whether any chronic users of opium in the crude form or of other opium preparations applied for treatment and if so whether they were given morphin or heroin as a substitute for their drug of choice. The unusually large percentage of heroin users, 96.5%, indicates an excess of young males of the underworld or gangster type with whom heroin is the drug of choice because of its slightly different physiologic action and also because it is the drug of choice of the peddler, inasmuch as it permits easily of adulteration.

In the report of the narcotic clinic, Los Angeles, Dr. Bucher gives the following sex-distribution, 389 or 66.8% males and 193 or 33.2% females."

Another series of cases which permit of statistical study has been obtained from Dr. Webster who conducted the narcotic clinic at Cleveland in 1920 and 1921.2° During the period of its existence approximately 2000 cases were registered, but only 681 of these are available for study through having been entered in a separate record. Dr. Webster states, however, that these 681 are, as far as he can tell, typical of the whole. Of these 446 or 65.5% are males and 235 or 34.5% are females.

E. Meyer-1924.2'

From a study of 90 cases treated from 1904 to 1923, this author reports as follows as to sex distribution and the age of beginning the chronic use of narcotics:

|

Under 20 years of age |

20-30 | 30-40 | 40-50 | Over 50 | |

| Men | 7 | 20 | 17 | 7 | 4 |

| Women |

- | 8 | 8 | 1 | 1 |

A review of the foregoing material brings out decided differences of opinion as to the incidence of the sexes among the opium-using popu-lation. The majority of writers state that women outnumber men as victims. However, in order to understand the reasons for this distri-bution, it is necessary to examine the types with which the individual writers appear to have dealt. As a very general rule, it will be found that those giving a preponderance of women have been private practitioners of medicine, or those whose surveys presumably covered all classes, while those giving a preponderance of men have had ex-perience wholly or chiefly with the inmates of correctional and other public institutions. Neither group has adduced evidence from suf-ficiently long series of cases to answer the question conclusively. It is natural, however, to suppose that among cases originating through the medical use of the drug women would exceed men in view of the greater frequency of recurrent or chronic, painful maladies among women. Many of these result from pelvic troubles and are, of course, peculiar to the sex. Whether or not other sex attributes having to do with the make-up of the individual have any etiological relationship we are not in a position to state. A cause frequently mentioned is painful menstruation which, from the nature of its periodic recurrence, is well adapted to induce sooner or later the chronic use of an opiate drug if such is taken for relief. The chronicity of the many pelvic inflammatory conditions needs no comment.

Among the cases dealt with by the medical heads of correctional and other institutions, however, other determining factors undoubtedly enter. Here the social groups dealt with are composed for the most part of criminal, underworld, or lower social types. Among these types of users there is little doubt that males preponderate. The greater exposure of young males to vicious associations, indulgences, and dissipations, the tendency to gang-formation, and the very great preponderance of males among peddlers all operate to bring to custo-dial institutions men rather than women.

The ultimate determination of sex preponderance must be based on material dealing accurately with the extent of the condition in the population as a whole. If it is found through future investigations that cases owing their origin to the medical use of the drug preponderate, it will doubtless be found that women preponderate. If, on the other hand, the illicit traffic, evil association, and other causes more peculiar to males than to females have brought about a greater number of cases of this type, a reverse sex distribution will doubtless be shown.

Age Distribution

In different series of cases the average age of chronic opium users varies considerably. No age period, however, is exempt. Even from birth, as indicated by the congenital cases, through infancy, with its soothing syrups and paregoric, to old age we find a varying number of victims.

In the consideration of the age period of the greatest prevalence of chronic opium intoxication, just as in the case of sex distribution, writers have reached different conclusions based on experiences with selected groups. In trying to determine the period of life in which the chronic use of opium is most frequently met, we must consider carefully the vitiating circumstances which creep in through such cause.

In what follows, we could wish for a greater abundance of material but, as in every other phase of this subject, the information is fragmentary.

C. W. Earle-1880.22

Earle states that chronic opium intoxication is "a vice of middle life, the larger number, by far, being from 30 to 40 years of age." In a series of 235 cases he gives the average age of males as 41.1 and that of females 39.4, the average for both sexes being 39.7. It will be remembered that approximately one-third of the women listed by Earle were prostitutes, which would tend to lower the average age of the females.

J. M. Hull-1885.28

Hull states that the age at which chronic opium intoxication is most common is the period between 50 and 60. In his series of 235 cases he does not separate the males and females so that only the combined average age of the sexes can be obtained. This figure is 46.5. Hull dealt for the most part with cases reported in small towns in an agricultural state, where in all probability the influences of prostitution and evil association in general were slight. This doubtless accounts for the greater average age of his cases than that of Earle's series.

C. E. Terry-1912.24

Terry found the average age of 551 cases, including 155 cocain users, both sexes, to be 35.2. (In another series collected a little earlier than the foregoing, 213 cases, the average age of beginning was found to be 26.1 years for males and 27.4 years for females or 26.7 for both sexes.)

L. P. Brown-1915.25

Brown found the average age of males to be 51, of females 49 and for the sexes combined 50. He comments as follows on his table of age periods:

"Table IV is possibly the most instructive of this series, showing as it does, the per cent of each sex at different age-periods. Note in this the great preponderance of women from age 25 to age 44. In these two age-periods they form nearly three-fourths of the whole number of addicts, and this preponderance appears to so far prevail into the next period that 63.5 per cent of all females are from 25 to 55 years of age, as against only 59.6 per cent of all males. It will be at once apparent that the first twenty years of this period is about the age when the stresses of life begin to make themselves felt with women, and includes the beginning of the menopause period. It appears reasonable, therefore, to ascribe to this part of female life, no small portion of the addiction among women. Again it seems fairly safe to ascribe the slightly larger proportion of men in the first ten-year life-period to the fact that this is about the age when dissipations are commonly taken up, these being more distinctively a male attribute."

Brown gives the average age of beginning for males to be 37 years and 10 months and for females 37 years and 6 months.

C. B. Farr-1915.26

Farr states that a large proportion of the 120 cases of heroinism studied by him were young—in the twenties,—a few of whom began as early as the fifteenth year. The average age of his 176 opium users was much greater than that of his series of heroin cases. In the former there was a fair proportion of middle aged and elderly persons.

W. A. Bloedorn-191721

Bloedorn published a table giving the age periods of a series of cases studied at Bellevue Hospital, New York, covering admissions from 1905-1916 inclusive, in which sex distribution is not indicated. The following are the average ages determined from that table,-34.1 for opium users, 31.8 for morphin users, and 24.1 for heroin users. The average age for all cases is 28.3. This series illustrates very well the point already brought out as to the different age periods obtaining among users of different opium preparations.

S. D. Hubbard-1920.28

Hubbard gives the following age periods for the 7464 cases registered at the New York City narcotic clinic:

"Age 15-19 20-24 25-29 30-34 35-39 40-50 Over 50 Total

Number 743 2142 2218 1155 766 365 75 7464

Percentage 9 28 29 14 10 9 1 100"

The average age for these cases in which males and females are not separated is 23.7. It will be remembered that 96.5% of Dr. Hubbard's cases were heroin users and that the great preponderance, 78.81%, were males. Both of these factors conduce to an early average age, inasmuch as they mean an undue preponderance of young males owing their condition for the most part to evil associations.

The 582 individuals registered at the Los Angeles narcotic clinic, 1920, were distributed as to age as follows:

18 to 20 years 5 50 to 60 years. 28

20 to 30 years 211 60 to 70 years 13

30 to 40 years 221 70 to 80 years 4

40 to 50 years 98 80 to 90 years 2

The average age figured from the above table is 35 years.

Webster's series 29 from the Cleveland narcotic clinic, 1920-21, gives an average age for males of 33.9 and for females 33.5, the average age for both sexes being 34.6. In this series of 681 cases the drug used was morphin except in one instance. This higher average age as com-pared with that of tile New. York City clinic would appear to indicate a different type of user from that predominating in the latter series.

Alexander Lambert-1922.3°

Referring to his study of 1593 cases, "persons in comfortable cir-cumstances of life and occurring in private practice," Lambert states the following:

"In the cases collected by Lambert, 17 per cent of the patients were under thirty, 31 per cent were between forty and fifty, and 18 per cent were over fifty years of age. In the age grouping, it is a noticeable feature that of those taking heroin 66 per cent were under thirty, while of morphin addicts only 12 per cent were under thirty."

C. F. Collins-1922.3'

Commenting on the age of cases coming under his notice in the Court of Special Sessions, New York, Judge Collins gives the following:

Comparative Percentage Table as to

Males 832 per cent and Females 16.8 per cent

Year Average age 21 years Under

and under 21 years

1916 23 years 48.12 28.27 18.91

24 years 54.29

1917 26 years 54.6 20.1 12.3

27 years 57

1918 25 years 49.7 16.2 10.5

26 years 54.15

1919 26 years 51.7 12.6 6.5

27 years 56.1

1920 25 years 46.5 17.8 8.2

26 years 53.5

1921 26 years 44.8 12.32 6.16

New York State Commission of Prisons-1924.32

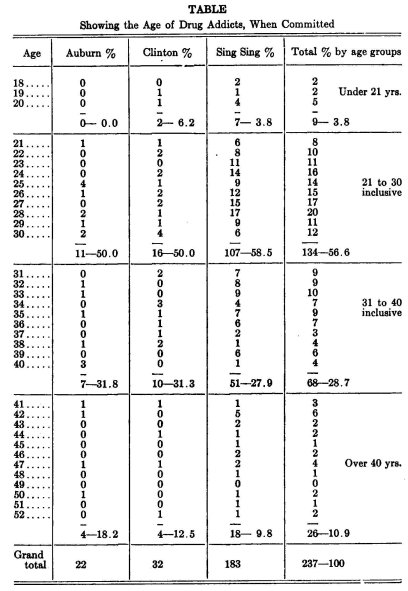

In a report on the findings of a special committee appointed by this Commission to investigate the problem of addiction, the following table is given to show the ages of 237 addicts convicted of felonies and sentenced to certain state prisons between January 1, 1921 and September 1924:

D. Oberteuffer-1924.33

Oberteuffer under the supervision of Professor Thomas D. Wood of Teachers College, Columbia University, New York, through a questionnaire survey made a study dealing in part with the use of habit-forming drugs by the high school children of New York State.

Questionnaires were sent to 687 schools in the state including all that are given the rating of Senior High School or High Schools. From these 360-52.4 per cent— replies were received, representing 152,824 pupils. Among this number there were no cases of drug addiction known.

In addition to the above data we are giving below material which we have collected as to the use of drugs by school children. Reports have been made from time to time of the use of these drugs by grammar and high school pupils and much publicity has been given by the daily press to such alleged conditions. Wherever such reports have come to our knowledge we have followed them to their source in an effort to obtain the actual facts. In practically every instance we have found that the published statements were greatly exaggerated and in some instances were based apparently upon rumor alone without even a single actual case in substantiation.

The following examples are typical of the published reports and our findings upon investigation:

A year or so ago we investigated a press item that was widely circulated to the effect that the children of a certain school were said by one of the teachers prominent in a woman's club to be addicted. Correspondence with the teacher in question brought out the fact that she had no accurate information and that her public statement amounted to nothing but a rumor brought to her by a child, that as far as she knew was without basis in fact.

From another city have been reported some cases of the use of opium by delinquent girls who obtained it in a dance hall. This was corroborated by correspondence but the conditions were quickly broken up by the local authorities.

A later press report related to the selling of narcotics to school children in one of the large eastern cities. We wrote to the chief of police who was reported to have charge of the investigation. He replied that after an extended investigation nothing could be found which in any way connected the high school pupils with the sale of narcotic drugs.

Even among the juvenile court cases chronic opium intoxication is uncommon This we investigated through letters addressed to 378 judges of juvenile courts from whom we received 122-32.2%—replies. From this number, who in the aggregate were handling thousands of juveniles a year, only 6 cases of chronic opium intoxication among delinquents were reported of which 3 came from one locality and the other 3 individually from different cities. Inquiries made from chiefs of police brought forth 2 cases from 45 cities.

From the above we may conclude that while chronic opium intoxication among juveniles is a potential danger, up to the present it has not existed to any great extent and that the reports which so far have been published in the daily press practically always have been greatly exaggerated. In our opinion it is extremely unlikely that addiction to narcotic drugs ever will become prevalent among school children. The price of these drugs as sold in the illicit traffic—from one to five dollars a grain—alone is a deterrent to their use by children of school age whose usual small means would not enable them to become lucrative customers.

The variations in the average age of users reported in the preceding data probably bear a definite relationship to the etiology of the corresponding series of cases involved. This relationship indeed is so constant within certain limits as to enable us to judge of the leading etiologic factors in any given series by noting the average age of the users. One will find, for instance, that the medical cases present an average age considerably higher than that of the users who acquired the condition through dissipation or vicious association. Naturally, we should expect the average age in the cases of medical origin to be found in that period of life contributing the greater part of painful, recurrent, or chronic conditions. Such seems to be the case where the influence of child-bearing, pelvic inflammatory troubles, rheumatism, neuralgias, or other conditions of this type, which occur principally in the third and fourth decades of life, is a prominent causative factor. In the underworld cases, on the other hand, where example, alcoholic excesses, evil associations, and the very common desire, especially among young men, to "try anything once" or to emulate the actions of others are of etiologic import, the average age of users of opium preparations is considerably younger. This period corresponds to that period of life in which ignorance, curiosity, and the spirit of adventure combine as potent influences of conduct.

The youth of chronic opium users is frequently a matter for public comment by those advocating certain reform measures. The apparent basis of such claims is the age of cases seen in correctional institutions, in some of the clinics, and in the free wards of general hospitals. Such series, as the foregoing material indicates, comprise chiefly heroin users and, because of the circumstances surrounding their collection, are not typical of the opium-using population as a whole and should not alone be considered in connection with prevention and control.

As a general rule, we find that the average age of chronic opium users apparently has been decreasing, as a study of the earlier series of cases shows this average age to be considerably higher than that of the more recent series. This is significant of the introduction of new and different etiologic factors, of which we find evidence in the growing use of these drugs among young people of both sexes, resulting chiefly from the illicit traffic. Those which give the lowest average age are the series reported since the passage and enforcement of the Harrison Narcotic Act, dealing for the most part with situations existing in large centres of population and comprised of anti-social groups in custodial institutions.

Form of Drug Used

There is a further aspect of chronic opium intoxication which is of especial interest in connection with sex and age distribution as well as with the etiology of the condition. It has been the common observation of practically every student and one which has given rise to frequent comment that different types of individuals, different etiologic factors, and even sex and age periods have been influential in the selec-tion of the particular opium preparation used. It is inevitable that in the earlier days of opium usage for medicinal purposes the cruder forms of opium should occupy practically the whole field, as the alkaloids had not yet been discovered. With the discovery and manufacture of the various opium products, as we have pointed out in the chapter dealing with the development of the problem, the popularity of their employment developed in the following order,— crude opium, mithridatium, theriaca, philonium, and diascordium, later the tinctures, powdered opium, and Dover's powder, and finally the alkaloids and their derivatives. It is natural also that, in accordance with their special properties or the properties thought to be possessed by them, certain preparations should have acquired popularity over others and that certain physicians and schools should have selected and clung tenaciously to favorite forms of this valuable drug. With the advent of the hypodermic the use of the alkaloids was increased markedly and for a while they usurped almost completely the places held by the earlier preparations. Later with the discovery of heroin and its alleged unique properties, especially valuable in certain condi-tions, a still further refinement of practice was made possible. While recently its employment in medicine has becOme unpopular owing to its widespread use in the underworld, there is even today a lively dis-cussion as to its merits and demerits and medical opinion is quite sharply divided as to its place in therapeusis.

Almost every opium preparation has some action distinct from that of the others and not only the medical profession but the laity as well have become more or less informed as to these distinctions and differences. With the cases of chronic opium intoxication owing their origin to the therapeutic use of the drug whether prescribed by phy-sicians or suggested by patent medicine advertisements, drug clerks, or the promptings of the general and common tendency toward self-medication, it is natural that certain preparations should have been used for certain purposes. Thus, because of their peculiar value, we should expect the employment of the cruder forms of opium in intes-tinal conditions, of morphin for the relief of pain, of codein and later heroin for respiratory troubles and so on. We find in the histories of the cases studied evidence of such therapeutic selection. The age of the patient and the length of the intoxication have also a direct beming on the selection of the opium preparation. Thus the chronic opium users among veterans of the Civil War and others of their generation are much more likely to be found using gum opium, powdered opium, or laudanum than are those. among the veterans of the Spanish War or of the late World War, where morphin was the drug of common choice. The selection of particular opium preparations, dependent on the stage of development in opium usage of the period and on therapeutic choice, is easily understood and needs little or no comment. With the advent of heroin, however, and the passage and enforcement of strict prohibitory legislation, new and unusual factors entered.

Reference already has been made to the fact that some time prior to the awakening of the medical profession in America the underworld was using heroin. It seemed to fill a place not easily duplicated by other opium preparations in the desires of the vicious user. The stimulating effect of heroin is known to be greater than that of morphin and this quality added to its narcotic property is a sufficient reason for its preference as a drug of dissipation. The facts also that it is easily absorbable through a mucous membrane as that of the nose, that it requires no equipment such as a hypodermic, and the consequent suggestion ever present in the minds of cocain users, have all combined to make it the opiate of choice of the underworld. We do not wish to be understood as meaning that there are no therapeutic cases of chronic heroin intoxication. On the contrary, there are a great many, but where evil association in conjunction with mental or moral degeneracy or abnormality exists, we usually find heroin to be the opium preparation of choice.

Here the influence of sex is seen; just as there appear to be more male alcoholics and more male cocain users there are also more male heroin users and for the same reasons. The exposure of males to evil suggestion is greater than that of females. There is more congregation of males in places of ill-repute. Occupation and the habits of the sex bring males more into contact with modes of dissipation in general and with the purveyor of illicit drugs in particular. Consequently we should expect to find a preponderance of heroin users in the early years of life in both sexes, particularly among young males.

Another factor is responsible for the recent increasing widespread use of heroin, namely the illicit traffic. There have been times in this commerce when smuggled heroin has been more easily obtainable than morphin and above all the ease with which heroin permits of adulteration without fear of discovery, thus permitting a very greatly increased profit to the trafficker, has made for its popularity in the underworld traffic. Heroin diluted one-half means profits increased 100% and the peddler has never been slow to embrace such opportunity for increased earnings. This preference of the peddler for heroin and the greater supply of the drug in the underworld market have had another result. Not only has it assisted in making heroin the drug of choice among underworld users but, also in conjunction with the deterring effect of anti-narcotic laws on the handling of cases of chronic opium intoxication by reputable physicians, a further increase in its use has occurred. Many individuals who had been using opium in some other form particularly morphin have been driven to peddlers for their supplies and, finding principally heroin available, have perforce adopted its use. There have been times in New York when morphin sold on the street as high as $80.00 an ounce while heroin was selling at a much lower figure. The cross-tolerance existing among the different opium alkaloids, permitting of changing from one to another, has made it not too difficult for the individual to forego his drug of choice and take up another which, for the time being, was more easily procurable. Thus a not inconsiderable number of cases owing their condition to the medicinal use of crude opium, laudanum, or morphin are today using heroin. In the chapter dealing with treatment we shall see in the statements of certain authors that this enforced selection has not been a beneficial one.

The chronic use of heroin was further increased as the result of its employment in the treatment of morphinism. We have seen in another chapter that it was early advocated in these cases and that as a result of such practice former morphin users had been transferred as it were to the newer preparation.

The distribution of cases as to drugs used, which have been reported from time to time, unfortunately has not been made so frequently as we might wish, but those data which we have at our disposal bear out the foregoing statements when considered in connection with the history of the problem, etiology, age and sex distributions.

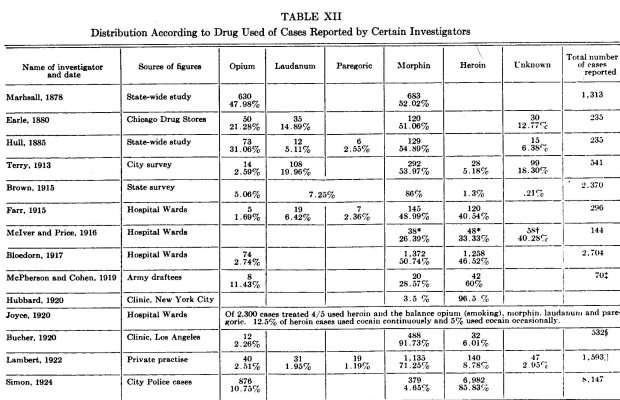

We have prepared the following table of distribution according to drug used from the material available.

In view of what already has been said as to the series of cases included in the above table little more is needed. But we desire again to point out that in certain series, notably those of Farr, McIver and Price, McPherson and Cohen, Hubbard, and Lambert certain in,. fluences which already have been covered in detail conduced inevitably to a selection in the types represented and these influences unquestionably account for the relative frequency of the opium preparations

given in these series.

Other Classifications

Further statistical classification may not be attempted with the material available, however desirable it would be to determine the incidence of other factors having possibly important bearings on the problem under consideration, its prevention, and ultimate control. Especially valuable would be material dealing with the physical condition, the mental and ethical traits, occupation, environment, and education.

In what follows one or another of these groupings is mentioned and while the material is not numerically convincing, when considered as a whole, it may lead to certain justifiable conclusions.

A. Calkins-1871.34

"In England, the toilers in the smitheries, and the midnight relays at the factory-looms, are conspicuous. The unfortunates too, who find temporary refuge in the lying-in hospitals, as Dr. Reid declares, are often addicted to laudanum, and to spirits besides. Exemption in families appears to be determined as much by class-distinction, though not in precise correspondence, as in China.

"In reference to Europe at large no particular section appears to have caught the infection, unless France be accounted a partial exception. On the Continent no distinct class perhaps could be specified, unless perchance some of the cloistered brotherhoods. Paris, however, not to be behind in innovations, is said, on Tiedemann's authority, to have within her bounds an inaugurated society of opium-smokers (Opiophiles, as they style themselves), who have their nightly reunions, and a journal provided for the recording of any notable individual experiences.

"Our home-classification wears a very diversified aspect. Some get into the the habit fortuitously rather; others gravitate the same way, as if determined by some occult impulse. Prominent in the ranks are the squadrons of litterateurs (they 'of imagination all compact' included), such as live by brain-labor,—and especially those who execute their work by instalments more,—representatives of the professions, itinerating trumpeters of the Orator-Puff grandiloquent, lackadaisical idlers, who have forgotten the primeval rule as 'when Adam delved and Eve span,' wine-bibbers, who would fain discard an old acquaintance for an untried novelty, the lady of haut-ton, idly lolling upon her velvety fauteuil and vainly trying to cheat the lagging hours that intervene ere the 'clockwork tin-tinnabulum' shall sound the hour for opera. or whist, the quasi-lady of the demi-monde as well, whose life has been a vicissitudinous fluctuation between affluence and unconcern at the one extr'eme and mischance and anguish of spirit at the other, and whose hard fortune now is

"To know the light but by its parting smile,

And toil, and strive, and wish, and weep awhile;

and last, if last in order yet numerically outflanking all the rest, the invalid throngs as they course along, 'not in single files but in battalions,' to be amused anew and to be decimated over and over by noisy nostrum-mongers and brag-gadocio pseudomantists."

B. H. Hartwell-1889.35

Hartwell, in reporting upon the answers received to a circular sent to druggists throughout the state from whom replies representing 180 cities and towns were received, writes:

"What classes of people use opium in your community? 446 answers: 22 per cent, all classes; 22 per cent, middle classes; 7 per cent, upper classes;

7 per cent, lower classes; 11 per cent, do not know of any who use opium; 11 per cent, do not know; 20 per cent, miscellaneous."

Replies received from circulars replied to by 260 physicians repre-senting 100 cities and towns are given by Hartwell as follows in answer to his question—"What classes of people mostly use it?"

"166 answers: 30 per cent, all classes; 22 per cent, higher; 3 per cent, middle; 6 per cent, lower; 12 per cent, middle and higher; 14 per cent, nervous women;

8 per cent, do not know."

T. C. Allbutt-1905.36

Allbutt, in his System of Medicine, says:

"Now, who are the persons who thus indulge themselves? The prompt answer will be—the neurotics. Who, then, are the neurotics? Are we not all neurotic nowadays? In a later chapter of this work I propose to discuss the subject of neurasthenia as a whole, and this I must not anticipate. I will repeat, however, what I have said on former occasions, that quickness and sensibility, acute perception and alert muscular reaction, are not morbid char-acters, but the qualities of high breeding. These qualities, however, become morbid when they are developed in relative excess in the lower ranges of sensi-bility, the higher qualities remaining at their former mean, that is, relatively in defect. Now that which in higher centers we call control, and in the lower inhibition consists in the reverse of this—in the cultivation of the higher planes of thought and sensibility, whereby the alertness of the lower is not diminished but transformed. Unfortunately disease may reduce a man to the level of those who had never known a higher state, and a man of mobile and sensitive fibre may thus for a phase become a neurotic; such a one may also become a morphinist under the pressure of pain or other distress, but he is not to be spoken of as constitutionally a neurotic. Again, not a few elderly persons have been under my care for sciatica, post-herpetic and other neuralgias, and the like, for whom morphine injections had been used; from such sufferers, however, this means must be firmly withheld, for it brings them into this dilemma, that while the rupture of the habit is in later life a graver stress, yet its continuance, by the cachexia it produces, is in them more quickly injurious to health than in younger persons. The establishment of a morphine habit in old people too often means an inevitable bondage, and shortened and fretful days.

"Another class of patients—not neurotic—presents itself to our consideration, namely, of those, young or old, who smitten by incurable and painful disease, expect no long span of life. Do we rightly encourage in these the use of the morphine syringe? That in some such cases, as of aneurysm, for example, the practice may be the lesser of two evil courses, may well be; but the solace is purchased at a heavy price. Whether pain soothed by less treacherous means be better, not only for the patient's friends but also for himself, than tearfulness, petulance, caprice, and a deterioration of character, which makes the death-bed scene of pettiness and exaction, rather than an example of fortitude and serenity, must be decided in the individual case. Too often a habitual resort to the drug, needed in increasing quantities, brings death of what is best in the man without euthanasia."

"Then comes the troop of those 'neurotics'—persons subject, perhaps, by nature to larger oscillations of nervous balance than the normal man—who scent intoxications from afar with a retriever-like instinct, and curious in their sensations, play in and out with all kinds of them; narcotics possess such folk almost by anticipation, and they often find less difficulty in the first tolerance than other people."

"One more group of morphinists and I have done. I refer to those who take morphine on small excuse, because it lies to their hand. Of these weak persons doctors and druggists form the majority; the rest are chemists and other men of science familiar with such means, who think in their folly that their technical knowledge will give them the use without the abuse of them."

G. P. Sprague-1907.37

Sprague from an etiologic point of view, divides persons suffering from morphinism into three groups:

"First, a small one composed of normal individuals, who, from unwise treatment for pain in acute illness, have contracted the habit; a second, larger group of moral degenerates who indulge in the vice of morphinism ; and a third and much the largest group, recruited from the victims of improper training and lack of early discipline; from the vast army of defectives who, beginning to lose ground in the race of life, resort to drugs as a spur, and from the large number who, suffering from sudden shock of disease, loss, etc., resort to the drug in the hope of obtaining relief. Granting these statements to be true, it follows that cause and symptoms in drug addiction are interwoven, and that a large majority of such patients are abnormal individuals, with whom the particular stimulant or sedative used is accidental, and dominates and masks the pre-existing and co-existing abnormality, in addition to adding an abnormality of its own."

C. W. Carter-1908.38

Carter states that morphin addiction does not respect age, sex, occupation, rank, race or vocation.

J. V. Shoemaker-1908.3°

"There is a fundamental fact to be borne in mind in the treatment of this class of patients, as pointed out by Kellogg; it is that the majority of persons who acquire the vice of drug addiction are peculiarly constituted, and are either those who live entirely upon the sense-plane, whose highest aim is to gratify their appetites, and who, when the natural resources begin to fail, stimulate them with various drugs; or they belong to a class of neurotic, hypersensitive individuals, who are the products of the brain-destroying and race-deteriorating conditions of modern life. In such cases the drug treatment should be secondary to hygienic measures, particularly diet, massage, electricity, and hot or cold applications to the occiput and spine. Relapses in such individuals should not discourage the physician or the patient."

C. C. Wholey-1913.4°

"Any individual may become addicted to the excessive use of narcotic drugs. The majority of my cases represent the average individual with the average heredity and environment. These persons have generally acquired their habit accidentally. It is, therefore, fallacious and unjust to refer without qualification to drug users as a class inherently neurotic and degenerate."

He also comments as follows on certain types observed but does not speculate as to the proportion which they form of the whole number of opium users:

"There are many individuals whose powers of resistance, by reason of inherit-ance and environmental factors, are merely sufficient to enable them to main-tain a healthy balance. They have enough nerve stability to carry them through an efficient life provided no exceptional strain is placed upon them. When such persons come into contact with narcotizing drugs, their delicate balance is likely to be overthrown; the nervous organism has no reserve with which to meet the added demand made upon it by the inroads of the drug. These individuals are not necessarily neurasthenic; they have been endowed with no more endurance than the ordinary routine of each day would demand."

"There is another individual who is congenitally just short of the balance which the above person normally possesses. This individual is inherently neurotic. His nerve endowment is not quite sufficient to enable him to live from day to day comfortably and effectively. He will, therefore (a mere biologic incident in his struggle for self-preservation), desperately grasp at whatever seems to aid his own inadequate efforts. When drugs come his way, with their seeming power to increase his flagging energy, or to bring peace and order into his turbulent, chaotic, harassed existence, it is inevitable that he shall anchor himself by their use. Those are individuals whom physicians should particularly safeguard; it is hazardous for them even once to experience the soothing influence of an opiate."

In addition to the above, Wholey states that there are a few fairly well-defined types, distinctly pathologic, who seem especially likely to become drug users, as the cyclothymiac, emotionally unstable in-dividuals alternately depressed and elated. This class, he believes, represents various shadings within the group of borderland cases showing manic-depressive characteristics.

Another pathologic type, the author continues, is that known as the constitutionally immoral, with undeveloped moral and ethical sense, impatient and with lack of endurance for physical or mental discom-fort. In this class are the ne'er-do-well, the tramp, petty thief, prostitute, etc.

Closely associated with the preceding, he says, there are certain distinct types which must be clearly differentiated. One is the high-grade imbecile, another the heboid often difficult to recognize, and frequently a precursor of dementia praecox.

These types must be carefully differentiated, the author believes, in order to deal intelligently with drug addiction. He states:

"The cyclothymiacs and the constitutional immorals possess an anomalous make-up which often precludes the possibility of cure. They drift from insti-tution to institution, relapsing again and again; the hopeless picture presented by these persons, really mental cases, has done much to create practically universal skepticism regarding cure for drug addiction."

P. M. Lichtenstein-1914.4'

The following by Dr. Lichtenstein is the result of observation of 1,000 cases admitted to the City Prison, Manhattan:

"As regards occupation, the cases observed and treated by me showed that the employment of habitués required little effort and gave them plenty of leisure time. The occupations given were as follows in the order named: Salesmen, clerks, newsdealers, truck drivers, actors, stenographers, waiters and waitresses, and cooks. I have found very. few who gave a history of performing very laborious work.

"Among the women, in the order named, the occupations were actresses, nurses and saleswomen. Most of these had been arrested for soliciting, keeping disorderly houses, or shoplifting. The social standing of habitues is an interesting item. The greater number are of the gangster type and consequently are mental and moral degenerates. It is surprising, however, to learn how many habitues are of the better class. Physicians, nurses and actresses, also some of the very richest of our people, frequently have elaborate 'lay-outs' in their homes, richly furnished, and stocked with the handsomest jeweled opium pipes. Many of these people naturally never attract our attention because of the absence of marked physical changes, due to good surroundings, good meals, etc."

S. Block-1915.42

"Normal persons will never become drug habitués. This is one other phase of the subject we must not overlook. The author has found it convenient to divide all cases into two great groups: first, those whose trouble is like a neurasthenia, if there is such a sickness; second, those who have a definite hysteria. Most of the cases belong to the hysterical class. These are treated like any other hysterics, and the certainty of permanent cure is the same. The main point is to make a careful study of the case, why and how the habit started, what physical affections have been wrought, etc. In short we must try to make a diagnosis beside recognizing a mere symptom that the layman knows as well as his doctor. Many cases of major hysteria are cured by suggestion in some form, many are only temporarily cured, and this is true of drug fiend cases. Likewise, as many cases of stuttering or other hysterical phenomena are acquired by imitation, so it is with these cases.

"In the neurasthenic type, as in other neurasthenias, we have the feeling of unrest, the desire for something not at hand, pessimistic unhappiness, inability to concentrate on any subject, seeing only the dark side of life. Like any neurasthenia it may originate from a series of misfortunes, real or imagined.

These people become self-conscious, shun society, threaten suicide, take big chances on important undertakings, and seek unnatural means to appease their terrible feelings. In despair they begin the use of drugs to get oblivion, having read or having been told of a feeling of well being following their use. How often are we told of the drunkard trying to 'drown his sorrow'."

D. K. Henderson-1916.43

"There seems to be very little doubt but that the vast majority of those unfortunate individuals who use drugs to excess are constitutionally unstable, poorly balanced, and psychopathic; they react to the difficulties and conflicts of their lives by becoming drug habitués. There are a few, especially those addicted to opium and morphine, who on the other hand, to start with may be fairly sound constitutionally, but who, on account of definite physical disorders usually of a painful nature, have had a narcotic prescribed by their physicians, and experience such blessed relief that even although they have only been taking small doses they gradually and insidiously come more and more under its influence, and ultimately find that they are quite unable to do without it."

"The majority of those who use this drug are the lowest of the low, and if anything are more vicious and more degenerate than those addicted to other forms of drug habituation. The above statement may, I think, to a certain extent be vouched for by the fact that the majority of those applying for treatment for heroin addiction are mere youths varying in age from 17 to 28 years, the average age for a series of nineteen cases being 20 years. In contrast, the average age of a series of fifteen cases of morphin addiction was 36 years, and the average age of a series of sixteen cases of alcoholism was 34 years. The above contrasts may be made still more striking when it is remembered that the devotees have usually been taking the drug for a number of years before they apply for treatment, so that there is no doubt that a good many of the heroin cases start taking the drug when they are only about 14 or 15 years of age."

J. McIver and G. E. Price-1916.44

McIver and Price, reporting on a study of a series of cases at the Philadelphia General Hospital, state:

"In considering the question of degeneracy, signs of arrested development, such as abnormalities in the shape and size of the ears and palate, irregularities in the arrangement of the teeth, abnormally shaped heads and marked facial asymmetry, were carefully studied. Of the 147 patients, fifty-nine, or 40 per cent, presented one or more of these stigmata to a well-marked degree.

"Some writers have emphasized the fact that 'neurotics' tend to acquire the cocain habit rapidly and Block says that 'Normal persons never become drug habitues.' While we believe that Block's contention is true as regards the majority of drug addicts, our observation is that normal persons may and do become habituated to the use of morphin through taking it over a considerable period of time for the relief of pain or insomnia; however, these patients, should the cause be removed, offer the best prognosis."

F. X. Dercum-1917.5

"We must remember that one who acquires drug addiction is usually not a normal individual. Frequently he is hereditarily neuropathic. Often we note in their family history alcoholism, nervous breakdowns or actual psychoses. The inheritance of ready exhaustion, depression, of a neuropathic make-up generally plays a role in some cases.

"The organization which leads to morphinism and cocainism does not differ essentially from that which leads to alcoholism."

W. A. Bloedorn-1917."

Bloedorn, in a study made of cases in Bellevue Hospital, New York, says:

"An examination of these cases at close range does not bear out the statement often made that drug addicts belong to the so-called criminal class. It is true that when the drug has come to. be a necessity for the addict the importance of obtaining enough of it every day overshadows everything else in his life, and in order to obtain the drug he has little hesitancy in lying or stealing. These traits are developed and become engrafted in the direct proportion that they become necessary to secure the desired relief and are not the result of inherent criminal tendencies. In other words, the individual is not an addict because he has criminal tendencies but rather he develops criminal tendencies because he is an addict."

"There is a tendency to surround drug addicts with an air of mystery, to regard them as a peculiar class, to ascribe to them numerous vices and few virtues and to set them apart from their fellowmen as being a distinct type. But when we attempt to describe this type we find that we are describing an individual and not a class. There is no justification for the mystery which has been allowed to creep in and hover about the drug addict. It is easy to dispose of these cases by consigning them to the so-called criminal class, or the class of defectives, but when we come to examine them individually and at close range we find increasing numbers who do not fit into these special classes. The term 'moral delinquent' has come to be applied to the drug addict and while there is justification for this term it really is only a synonym of drug addict and does not serve to throw any considerable light on the class as a whole."

"The Binet test was also a part of the examination in all cases and while the series is not yet completed it is evident that drug addicts cannot be classed as mental defectives. While, naturally, some were found who fell below the 15-year test at least 80 per cent. answered all tests applied and showed no evi-dence of being mentally backward."

Joint Legislative Committee, New York-1917.47

"It has further been stated by competent authorities before your Committee that drug addiction is not confined to the criminal or defective class of humanity.

"This disease, however contracted, is prevalent among members of every social class."

F. H. Carlisle-1917.48

Carlisle states that individuals too poorly equipped mentally fully to appreciate the dangers of continued use of the drug, moral de-linquents whose addiction is engrafted on an unstable moral and mental make-up, and individuals of criminal tendencies constitute about twenty-five per cent of admissions and reduce the nun2ber of favorable results of treatment in like proportion.

C. L. Dana-1918.4°

"Most addicts are constitutionally unstable persons, likely to be a burden or a menace to society anyway.

"Drug addiction does not lead to insanity or the serious psychoses needing cus-todial care. The percentage of such cases in State hospitals is very small. It is very large, however, in prisons and reformatories and it would seem as if drug addiction had more relations to crime and social waste than to psychiatry.

"The drug addict is not usually a mental defective, and a series of intelligence tests would not disclose large percentages of morons and imbeciles, as happens in certain other anti-social groups."

G. D. Swaine-1918.5°

"In Class one, we can include all of the physical, mental, and moral defectives, the tramps, hoboes, idlers, loafers, irresponsibles, criminals, and denizens of the underworld, and, among women, the idle rich, who began taking the drug for the intoxication it produces and have kept it up until they have become slaves to its devilish power. And, all these do not want to be cured. If forced to take treatment, they may be cured, but, they almost always relapse. In these cases, morphine-addiction is a vice, as well as a disorder resulting from narcotic poisoning. These are the `drug-fiends.'

"In Class two, we have many types of good citizens, who have become addicted to the use of the drug innocently and who are, in every sense of the word 'victims.' Morphine is no respecter of persons, and the victims are doctors, lawyers, ministers, artists, actors, judges, congressmen, senators, priests, authors, women, girls, all of whom realize their conditions and want to be cured. In these cases, morphine-addiction is not. a vice, but, an incubus, and, when they are cured they stay cured."

C. B. Pearson-1919.5'

Pearson says that the degenerate type is the one who has given the morphin addict a much worse reputation than he deserves and is the one always in evidence. The better type is not, for he is not suspected of being an addict. It is among this latter class that we get our highest percentage of permanent cures and this is also the part of our work most likely to remain unknown.

The straight morphin addict, he says, rarely becomes a degenerate.

"So far as my experience goes I have yet to see my first case. The causes of degeneracy among morphine addicts are the immoderate use of alcohol, mixed drug taking, syphilis of the nervous system, the repeated attempts at heroic treatment that end in failure, or repeated shocks due to abstinence from the drug from any reason, viz., imprisonment, or accidental separation from the source of supply due to lack of funds or any other reason. I have seen a number of morphine addicts who were mixed drug takers, who also used alcohol to excess and who were also syphilitics, who had not yet reached the point of degeneracy. However, I believe this combination will produce degeneracy if given time enough in every case. I do not mean by this that morphine is not one of the causal factors of degeneracy in the latter type of cases. While morphine acting upon one who lives a normal hygienic life in all other respects has not in my experience proved to be sufficient to cause degeneracy we can readily see that the case may be different when the drug acts upon an individual whose power of resistance is being or has already been broken down by the excessive use of alcohol, cocaine, chloral hydrate or other powerful hypnotics, syphilis, the repeated shocks of mistaken methods of treatment, even if only one of these factors is working with the morphine. But when all are combined degeneracy cannot be far away. However, it is really surprising how long some of them bear up 1under all these factors of degeneracy and still retain a fair degree of mental and moral integrity for some time."

T. S. Blair-1919.52

"Morbid and unstable individuals who become drug addicts are the 'horrible examples' held up too much to public view and reprobation. It is not true that all drug addicts, nor even one-fourth of them, ever become such creatures as are depicted in fiction."

"And it must be admitted as a fact in therapeutics that there are many opium addicts who are not casually recognized as such, even though for years addicted. This is not said in defense of opium addiction, but acknowledged as a fact that must be properly evaluated."

"We are listing the drug addicts as follows:

Pure addicts. They should be cured.

Addiction with curable disease. This is a clinical problem. Addiction with incurable disease.

Addiction in the aged, which is hard to cure."

M. C. Mackin-1919.53

Mackin, writing of cases treated by the State Hospital for Inebriates, Knoxville, Iowa, 1919, says:

"According to Pouchet, forty per cent. of our morphinists are physicians, and the wives of physicians also constitute a considerable percentage. Besides physicians, druggists often become addicts.

"Morphinism, as a rule, affects those hereditarily tainted, who have less stamina to oppose the continued use of the drug. This would be hardly fair to the medical profession to accuse such a large percentage as being hereditarily tainted and the statistics of the State Hospital of Inebriates at Knoxville on this question are at a decided variance with statistics of Pouchet. Our hospital shows that less than two per cent of those admitted were physicians."

Special Committee of Investigation appointed by the Secretary of the Treasury-1919.54

. . . the Committee finds that addicts may be divided into two classes, namely, the class composed principally of the addicts of the underworld and the class which is made up almost entirely of addicts in good social standing."

Under the heading "Effect of addiction on morals," the Committee reports:

"From information in the hands of the Committee, it is concluded that, while drug addicts may appear to be normal to the casual observer, they are usually weak in character and will, and lacking in moral sense.

"The opium or morphine addict is not always a hopeless liar, a moral wreck, or a creature sunk in vice and lost to all sense of decency and honor, but may often be an upright individual except under circumstances which involve his affliction, or the procuring of the drug of addiction. He will usually lie as to the dose necessary to sustain a moderately comfortable existence, and he will stoop to any subterfuge and even to theft to achieve relief from the bodily agonies experienced as a result of the withdrawal of the drug. There are many instances of cases where victims of this disease were among the people of the highest qualities morally and intellectually, and of the greatest value to their com-munities, who when driven by sudden deprivation of their drug, have been led to commit felony or violence to relieve their misery."

S. E. Jelliffe and W. A. White--1919.55

"The habitual use of opium in some form has become common among all classes in society. The same thing may be said with reference to the reasons for taking opium as has been said with reference to alcohol. The opium habitue is a person primarily of neuropathic taint, the mere opium taking or the symp-toms it produces being but surface indications of the real trouble."

G. E. McPherson and J. Cohen-1919.56

Based on their survey of 100 cases of drug addiction entering Camp Upton, N. Y., via the draft, 1918, McPherson and Cohen report that the mental-age ratings secured by the Stanford-Binet, Point-Scale, Performance-Scale, and Beta Tests indicate that the intellectual level of drug addicts appearing before the Recruit Medical Examining Board does not vary strikingly from that of normal draftees.

J. H. W. Rhein-1920.5T

"Any effort to correct the evils of drug addiction must be based on a thor-ough understanding of the psychologic factors underlying the cause. I do not believe that mental deficiency is a cause of drug addiction, nor do I believe that the proportion of mental defectives is high among drug addicts. I believe that improper prescribing of opium, morphin or heroin by physicians, while responsible in some degree, is only incidental in drug addiction. I mean by this that the cause of development of the habit is inherent in the individual. The drug addict is a psychopath before he acquires the habit. He is a person who cannot face, unassisted, painful situations; he resents suffering, physical, mental or moral; he has not adjusted himself to his emotional reactions. The most common symptom that requires relief is a feeling of inadequacy; an inability to cope with difficulties. These conditions call for an easy and rapid method of relief which is found in the use of drugs. It is simple enough to cure the victim of his craving temporarily, but the difficulty is in preventing a return to the habit. To cure a drug addict means to reconstruct and re-educate his personality so that he can adapt himself to his emotional reactions."

T. F. Joyce-1920.68

Joyce, writing of cases treated at Riverside Hospital, New York, and for the most part sent there by the New York City clinic, says:

"Drug addicts may be divided into two general classes. The first class is composed of people who have become addicted to the use of drugs through illness, associated probably with an underlying neurotic temperament. The second class, which is overwhelmingly in the majority, is at the present time giving municipal authorities the greatest concern. These people are largely from the underworld or channels leading directly to it. They have become addicted to the use of narcotic drugs largely through association with habitues and they fmd in the drug a panacea for the physical and mental ills that are the result of the lives they are leading. Late hours, dance halls, and unwholesome cabarets do much to bring about this condition of body and mind and in a great many cases these people are found far below the standard mentally."

S. D. Hubbard-1920.59

Hubbard, describing the work of the New York City Narcotic Clinic, says:

"There are drug addicts constitutionally inferior, and superior; feeble minded, and strong minded; physically below, and above par; morally inferior, and superior. No one class of society seems, in our experience, to enjoy a monopoly in this practice."

Further on he says:

"It has been said that the experience in the Department of Health emergency narcotic clinic was unique; that the character of the addicts visiting this service was very exceptional. Possibly our experience dealt with an unusual feature of this problem, but from personal consultations with many acknowledged addicts—in all walks of life—journalists, ministers, writers, physicians, clergymen, teachers, business men, etc., seeking interpretation of the law's requirements, as it affected them individually—they being addicts—we naturally had an opportunity for first-hand information."

Later he writes:

"We feel that we have had an unusually wide and peculiarly general experience with drug addicts of all classes--classes so large as to make us think that others' experience in this form of practice has not been nearly so extensive."

Unfortunately Dr. Hubbard, though mentioning in the second paragraph above that among others, writers, clergymen, teachers, and business men constitute some of the occupations represented among users of narcotic drugs, fails to mention any of these occupations by numbers in his occupational classification of the patients treated at the clinic as listed at the end of the same article.

In another article in the same year, Hubbard 60 classifies drug users as follows:

"The habitual users of narcotic drugs may be divided into two general classes:— (I) Those who suffer from a disease or ailment requiring the use of narcotic drugs and (2) addicts—dope fiends—drug habitués; those who use narcotic drugs for the comfort these afford and solely by reason of an acquired habit. The Harrison Narcotic Law (U. S. Supreme Court, Doremus and Webb cases) says that drugs may not be given to keep the users comfortable by maintaining their customary use.

Class 2 may be divided further:

(a) Correctional (underworld type).

(b) Mentally defective (the constitutionally inferior person or the individual with feeblemindedness).

(c) Social misfits (the person whose maladjustment does not permit him to conform to social customs).

(d) Fortuitous (the individual who has had an adequate reason for taking narcotics, but the reason has disappeared and the drug habit is continued because of the physical suffering which unaided deprivation brings).

Many addicts loathe their habit, but physically cannot break from it unaided. A number of addicts, especially those in class 2, subdivision (a), use the practice of drug indulgence in their jobs. In our experience in drug addiction in New York City we found that those in subdivisions (a) and (b) were mostly heroinists, while the morphinists were in (c) and (d). The heroinist and morphinist have been thus differentiated by an outspoken physician: The morphinist has guts, while the heroinist has only bowels."

"The addict is not always a hopeless liar or a moral wreck or a creature sunk in vice and lost to all sense of decency and honor, but was frequently in our experience an upright person except as concerned his affliction or the procuring of the drug of his affliction. Addicts lied about dosage; but when they found that the game was 'on the level' they would voluntarily admit deception and tell what they were actually taking.

"When it is considered how these creatures were hounded and imposed on by illicit prescriber and dispenser, as well as how they endeavored to escape police detection and family discovery, it was natural to meet some peculiar situations; but when sanctuary was assured, they calmed down and became friendly and communicative, and in many instances helped the officials to aid them in getting rid of their habit. Most of them when freed are anxious to remain free. I have been assured of this so often by addicts who have been off the drug and whom I have followed up that I make this statement advisedly and with positive assurances that many of our cases are off the drug for good, provided all temptation is removed. There were many instances in our experience in which the victims of this condition were persons of the highest qualities, physically, morally and intellectually, and some held high positions of authority and responsibility. One is a signalman who for twenty-five years has been addicted, yet has not missed a day from work and has never been reported for any company infraction, and, strange to relate, his superior officer was wholly unaware of his misfortune. This man took the cure and returned to his position, and for the last six months has been off the drug.

"The correctional class I do not desire to discuss here, as the subject is one which merits special and lengthy consideration. The underworld addict is grossly misunderstood. While drug indulgence has been held accountable for his unmoral character, those whom I have had opportunity to study show degeneracy incident to association and environment, and addiction only as a secondary expedient for stimulating nerve energy and drowning painful reminiscences."

Hobart A. Hare-1920.°'

Hare in discussing Lambert's article entitled "Scope of Therapeutics in the Relief of Narcotism" at a symposium of the Philadelphia County Medical Society, says his experience has shown that there are two classes of addicts: (1) Those fundamentally rotten by inheritance, and (2) those not fundamentally rotten, "but men and women, like any one of us, who, through illness, have come to be dependent on morphin, codein or possibly even heroin." He says these people are easily cured and separate themselves from the true morphin habitue who does not want to be cured. There is a difference in the morale and courage of the two classes. Twenty years ago, he says, he did not have much faith in the cure of morphinism, but experience has taught him that many people who have slipped into addiction through chrouic painful maladies as bladder and pelvic troubles can with a little care be cured.

American Medical Association-1920.62

At the 1919 meeting of the House of Delegates, American Medical Association, a special committee ori the question of narcotics was appointed consisting of Dr. E. Eliot Harris, Chairman; Dr. A. T. McCormack, Dr. Paul Waterman, Dr. Alexander Lambert, ex-officio. So far as we have been able to determine this was the committee which reported in 1920:

"We think it is also apparent that the habitual users of narcotic drugs may be divided into two classes. In Class 1 we shall place all those who suffer from a disease or ailment requiring the use of narc,otie drugs, such as cancer, and other painful and distressing diseases. Patients in this class are legitimate naedical cases, and the physician should be ever mindful that his patient should protect him by not sharing the drug with others.

"After excluding Class 1, we have left for consideration those who are addicts—those who use narcotic drugs for the comfort they afford and continue their use solely by reason of an acquired habit. In this class we have those who are suffering from a functional disturbance with no physical basis expressed in pathologic change. ."

"We turn to the consideration of the persons classified as addicts after ex-cluding all those who suffer from a disease calling for the use of narcotic drugs, and with the conviction that we are dealing with functional conditions for which the remedy is the withdrawal of the drug. On the basis of the testimony we have submitted in this report we suggest the following subdivisions of Class 2, in which we include addicts as just defined:

1. Correctional cases

2. Mental defectives

3. Social misfits

4. Otherwise normal persons."

A. Lambert--1920.63

"While the psychoneurotic and the inadequate personality break down more completely under the mental conflicts and strains of life and resort more quickly to narcotism than normal persons, all morphin users are not of this type. Many are normal personalities of more than average intelligence and realize fully their positions and their progressive degeneration. Such individuals are really filled with remorse and resent the stigma which is placed upon them for a habit for which they are often not responsible."

* * * *

"It has often been stated, both in lay and medical writings, that the purely physical cravings for narcotics is directly inherited. This today is a discarded theory, as the facts do not bear it out. The craving is only physical when recovering from over indulgence. The so-called craving is always an emotional impulse often over-powering the so-called will even against the judgment and reasoning endeavors of the personality to resist. Feeble-mindedness is inherited. The weak-willed self-indulgent personality, prone to excess in all things, is inherited. The self-conscious, introspective personality, unable to stand the hard knocks of life, is a personality often transmitted from parent to offspring. . . . In these psychoneurotic individuals, alcohol and drug addiction is but the expression of the desire for relief from a strain which cannot be borne."

E. S. Bishop-1920.64

"It is a fact that the narcotic drugs may afford pleasurable sensations to some of those not yet fully addicted to them, and that this effect has been sought by the mentally and morally inferior purely for its enjoyment for the same reasons and in the same spirit that individuals of this type tend to yield themselves to morbid impulses, curiosities, excesses and indulgences. Experience does not teach them intelligence in the management of opiate addiction and they tend to complicate it with cocaine and other indulgence, increasing their irresponsibility and conducing to their earlier self-elimination.

"Wide and varied experience, however, hospital and private, with careful analysis of history of development, and consideration of the individual case, demonstrates the fact that a majority of narcotic addicts do not belong to this last described type of individuals. It will be found upon careful examination that they are average individuals in their mental and moral fundamentals. Among them are many men and women of high ideals and worthy accomplishments, whose knowledge of narcotic administration was first gained by 'withdrawal' agonies following cessation of medication, who have never experienced pleasure from narcotic drug, are normal mentally and morally, and unquestionably victims of a purely physical affliction."

* * * * *