CHAPTER III ETIOLOGY

| Books - The Opium Problem |

Drug Abuse

The importance of the causative factors responsible for such a condition as the one under consideration requires no emphasis. It is patent that in order to succeed all preventive work must be based on an appreciation of such factors. Yet unfortunately few comprehensive studies concerning the etiology of chronic opium intoxication have been made. This apparently is due to the fact that the experiences of individual writers have been limited to one or another class of patients. Thus the prison physician, the alienist and the medical head of a private sanatorium handle very different types and it is quite apparent that studies of such selected groups elicit very different conclusions as to the relative influence of causative factors. No one study of which we have knowledge contains a true cross-section of the opium-using population and it is only by the most careful evaluation of all of them that the truth can be ascertained. In view of the total lack of really comprehensive studies these determining factors should be borne in mind by the reader of what follows.

F. E. Oliver-1871.1

From correspondence throughout the State of Massachusetts, Oliver was informed that the "habit" was caused by the injudicious and often unnecessary prescribing of opium by the physician. He adds: "So grave a statement, and one so generally endorsed, should not be allowed to pass unnoticed by those who, as guardians of the public health, are in no small measure responsible for the moral, as well as physical, welfare of their patients."

As further causes the writer mentions depressed conditions of the nervous system induced by occupation, overwork with deficient nutrition, or a vicious mode of life as prostitution and sometimes intemperance. He states that those most generally exempt from this vice are out-of-door laborers and others with occupations allowing an abundance of fresh air and nourishing food. In England, he states, and suspects that it is true also of this country, the opium habit is especially common among the manufacturing classes who are too apt to be indifferent to all hygienic laws. He adds that one of the most frequent predisposing causes is the desire of stimulation which is common in all peoples. The selection of opium in preference to other stimulants is prompted, according to some of his correspondents, by motives of expediency, the facility with which it may be procured and taken without endangering the reputation for sobriety.

He lays emphasis on one source of the opium "appetite," according to a number of his correspondents, that of its use in infancy and childhood for nursery medication, stating that it is the principal constituent of most of the soothing syrups, such as Winslow's Soothing Syrup.

A. Stille-1874.2

"In some countries where the heat of the climate, or the prohibition of wine by religious enactment, restricts the use of alcoholic drinks, the innate and universal propensity of man to employ some artificial means of promoting the flow of agreeable thoughts, of emboldening the spirit to perform acts of daring, or of steeping in forgetfulness the sense of daily sorrow, has led the inhabitants to seek for those coveted objects in the use of opium. Throughout the whole of Southern Asia, but especially in its most opposite regions, Turkey and China, the consumption of opium for these purposes exclusively is so great as almost to exceed belief. Of late years, also, the habit of chewing opium is alleged to have become very prevalent in the British islands and in the United States, especially since the use of alcoholic drinks has been to so great an extent abandoned by certain classes of people under the influence of the fashion introduced by total abstinence societies, founded upon mere social expediency, and not upon that religious authority which enjoins temperance in all things, in meat and condiments as well as in alcohol and opium. It is true that opium is not likely to become popular among an active and industrious race like the Anglo-Saxon, whose preference must always be for the more potent, though less permanent stimulus, of ardent spirits, the 'gross and mortal enjoyments' of which are far more suitable to the character of that race than the 'divine luxuries' of opium. 'If,' says De Quincey, 'a man "whose talk is of oxen" should become an opium-eater, the probability is, that (if he is not too dull to dream at all) he will dream about oxen;' but men of active mind and warm imagination, as the Orientals generally are, will choose the stimulant which multiplies and gives a livelier coloring to the ideas, rather than that which, acting more especially upon what is merely sensual in man, excites to muscular exertion and boisterous mirth."

S. F. McFarland-1877.3

"I believe that nearly all the cases of opium inebriety are produced by its medicinal use, and most commonly through the prescription of physicians. At }east, during a practice of twenty-four years, I have never known a single instance which did not thus originate. Many a prescription, intended for a day, is continued indefinitely. Several have resulted from the use of patent nostrumsAyer's Cherry Pectoral, McMunn's Elixir of Opium, and various cough mixtures.'

0. Marshall-1878.4

Marshall makes the following statement based on his survey in Michigan:

"The opium-habit in this country sems to arise from many different causes, prominent among which is the indiscriminate use of medicines without intelligent medical advice. Few families are to be found who are without their stock of remedies. Common among these, are opium, morphine, Dover's powder, laudanum, and paregoric, besides the domestic prescriptions containing opium. For the nursery, in addition to the common opiate preparations, are the patent soothing-syrups, cordials and anodynes, nearly all containing opium.

"To show to what an extent the dosing of infants with opiates is carried, it is claimed that over three-quarters of a million of bottles of Mrs. Winslow's soothing-syrup are sold annually in the United States. According to an analysis made and reported in The California Medical Gazette, each bottle of this syrup contains from one-half a grain to one grain of morphine. Placing the average at Three-quarters of a grain to each bottle, the amount of morphine used in this manner would be 562,500 grains, or about 1,171 Troy ounces,—enough to kill a half million of infants not accustomed to its use."

"From the predisposition to nervous and neuralgic affections produced by it, probably many cases of the opium-habit in the adult have their first cause in the use of opiates in infancy and childhood. A want is created in the child which is satisfied in the adult when opium is taken, tolerance being already established."

"The most frequent cause of the opium-habit in females is the taking of opiates to relieve painful menstruation and diseases of the female organs of generation. The frequency of these diseases in part accounts for the excess of female opium-eaters over males.

"Undoubtedly in many instances physicians are directly responsible for the habit, in continuing the medicine too long, or too frequently resorting to it; but more often the opiate is prescribed and afterward indefinitely continued without the physician's knowledge or consent. The prescription intended for a day is repeated by the druggist many times, and its use is continued until the habit is formed. I believe there is no effectual law to reach these cases or prevent the sale of opium in any quantity. At present it would not be difficult for a lunatic or a child to obtain at the drug stores all the opium he called for, provided he told a plausible story and had the money to pay for it."

H. H. Kane-1880.6

"The dangers of contracting this habit from the hypodermic use of morphia was recognized in the very infancy of the practice, but was scoffed at or disregarded until a few years ago, when the profession in Germany, England and America awoke, almost simultaneously, to a knowledge of the fact that the habit had become alarmingly common, and that it had been contracted, in the majority of instances, through the carelessness of the physician, 'who had taught either the patient or his friends how to use the instrument.

"Some of my correspondents, men of ability and in large practice, express themselves as very skeptical of the truth of the statement that the morphia habit has ever been formed by the use of the drug hypodermically. Testimony from all parts of the civilized world settles this matter beyond question."

* * * *

Kane goes on to say:

"The most important point for the physician to keep in mind is that, in the majority of cases, formation of the habit from the use of the hypodermic syringe is his own fault. When care and discretion are exercised the rule will be for the patient to recover without any desire to continue the use of the drug."

C. W. Earle-1880.6

In a report covering a study of the extent of the chronic use of opium in Chicago, Earle makes the following statement:

"In many cases it is difficult to ascertain the reason for taking the drug. The customer buys the preparations he desires and immediately takes his departure; and it is usually a delicate question to ask, 'What do you take it for?' Dr. Joseph Parrish says 'that men take it not for social enjoyment, but for a physical necessity.' With such an opinion I have no sympathy. When it is a physical necessity for men, to steal and lie, and murder and partake of alcohol to such an extent as to incapacitate themselves for work, and bring ruin on their families, then I will admit the same in regard to opium-eating. Quite a number, however, freely confess the reason for taking the drug. Eight say that it is for its stimulating and happy effect; four formerly were addicted to drink and seek quietude by taking opium; five are unhappily married; thirty-eight have had rheumatism and are now suffering from it to some extent, and an equal number assign neuralgia as the cause of their pains, for which some form of opiate is taken. Those diseases known by the incomprehensible name of 'female complaints,' are frequently given as the cause for taking an opiate. Previous sickness, and wounds received during the war, painful stumps after amputation, injuries to nerves, etc., etc., loss of property and position in society, are given by a few. But the great majority confess that it was first given during some disease in the course of which pain was a prominent symptom. An opiate was prescribed by the physician, and ever afterward, when suffering pain, the little powder, or laudanum, or gum opium, has become their solace. However much we may desire to avoid this grave responsibility, the truth must be confessed, that the greater number of men and women who are now completely enslaved to the different preparations of opium, received their first dose from members of our profession."

H. Obersteiner-1880.7

Obersteiner states that medical men are justly charged with spreading the disease owing to their carelessly leaving morphia and a syringe with the patient and that it appears to be their punishment that many themselves fall victims.

Daniel Jouet-1883.8

Jouet states that the two great causes are, as Levinstein first stated in describing the condition, the use of morphin to relieve pain and its use to bring about the euphoria the drug produces.

Besides calling attention to the growing fashion of morphin use by the upper strata of society, Jouet states that as a rule it is in the therapeutic use of the drug to relieve pain and procure calm and rest that the first knowledge of it is formed. It is especially those of nervous temperament and excitable natures who are subject to neuralgias and who become easily familiar with morphin. It is to individuals of the type'S in whom the intellectual life predominates and who have the greatest tendency to sensual pleasures that the physician is most apt to give the drug for self-administration.

In a table the author lists various conditions for which the drug was originally administered and the number of cases of morphinism caused by each.

Ataxia 32

Prostatitis 2

Sciatica 14

Nervousness 7

Neuralgias 10

Peritonitis 1

Asthma 8

Periostitis 2

Dyspepsia 2

Gastro-Enteralgia 1

Hypochondriasis 4

Pleuritic pains 4

Madness 2

Painful contractures 1

Painful tumors 9

Hemoptysis 1

"There are omitted from this table a few cases of morphinism due to imitation and one of a physician due to repeated experiments on himself. Given these two major causes of addiction—relief of pain and the desire for agreeable sensations—it is easy to see why the number of morphinists is so large when we consider the multiplicity of painful affections, the ease with which patients may procure morphin, and finally the condemnable indifference in certain cases, of some physicians who are too willing to leave morphin in the hands of their patients."

M. Notta-1884.8

"One can become a morphinist in two ways: either by taking morphin internally, in the form of powder, for example, or by absorbing it by the hypodermic method in the form of an injection. It is this last method which is the more widespread and one can only say that the hypodermic injection is the mother of morphinism. But if that is the principal cause, it is not the only one. There is still another guilty one, the physician. Ask morphinists how they contracted this unfortunate habit. Eight times out of ten, the reply is the same; they had a rebellious neuralgia, some illness (often in women pelvic peritonitis) the pain from which could be relieved only by an injection of morphin. The physician always administered it, but one day when he was away, not being able to stand the pain, they administered it themselves. Since then they have continued it, multiplying the injections finding it so easy to relieve the least pain by a little injection and they have developed the taste for it. Now, although cured, they cannot get along without it, they are morphinists! From use to abuse there is only a step and this step is very quickly taken! It is the story of the first cigar; it seems good, or it makes one vomit, one smokes a second, one habituates himself to it, and one becomes a smoker."

J. M. Hull-1885.1°

Hull, in presenting the results of a survey made by him in Iowa, states:

". . . The habit in a vast majority of cases is first formed by the unpardonable carelessness of physicians, who are often too fond of using the little syringe, or of relieving every ache and pain by the administration of an opiate."

William Pepper-1886."

"Pain holds the chief place among the influences which predispose to the formation of the opium habit. By far the greater number of cases have taken origin either in acute sickness, in which opium administered for the relief of pain has been prolonged into convalescence until the habit has become confirmed, or in chronic sicknesses, in which recurring pain has called for constantly repeated and steadily increasing doses of opiates. In view of the frequency and prominence of pain as a symptom of disease, and the ease and efficiency with which opium and its preparations control it, the remote dangers attending the guarded therapeutic use of these preparations are indeed slight. Were this not so, the number of the victims of the opium habit would be lamentably greater than it is. For these reasons the use of opiates in acute sickness, if properly regulated, is attended with but little danger. Far different is it, however, in chronic painful illnesses. Here to procure relief by opium is to pave the way not only to an aggravation of the existing evils, but also to others which are often of a more serious kind. Opium is at once an anodyne and a stimulant. The temptations to its use are of a most seductive character. To the over-worked and underfed mill-operator it is a snare more tempting than alcohol, and less expensive. It allays the pangs of hunger, it increases the power of endurance, it brings forgetfulness and sleep. If there be myalgia or rheumatism or neuralgia, and especially the dispiriting visceral neuralgias so common and so often unrecognized among the poorer classes of work-people, opium affords temporary relief. The medical man suffering from some painful affection, the worst symptoms of which are relieved by the hypodermic injection of morphine, falls an easy prey to the temptation to continue it—a danger increased by the fact that he is too often obliged to resume his work before convalescence is complete. Indeed, the self-administered daily doses of physicians sometimes reaoh almost incredible amounts. To women of the higher classes, ennuyee and tormented with neuralgias or the vague pains of hysteria and hypochondriasis, opium brings tranquillity and self-forgetfulness."

*

"The responsibility of the physician to his patient becomes apparent when we reflect that with very few exceptions the opium habit is the direct outcome of the use of the drug as a medicine."

* * *

"A predisposing influence of more importance than would at first sight appear is found in sensational popular writings upon the subject. As Kane has well said, 'At the time in which De Quincey, Coleridge, and Southey lived the people and his profession knew little of the opium habit save among foreign nations. The habitues were few in number, and consequently when De Quincey's article appeared it created a most decided impression upon the popular mind—an impression not yet effaced and one which bore with it an incalculable amount of harm. Men and women who had never heard of such a thing, stimulated by curiosity, their minds filled with the vivid pictures of a state of dreamy bliss and feeling of full content with the world and all about, tried the experiment, and gradually wound themselves in the silken meshes of the fascinating net, which only too soon proved too strong to admit of breaking I There can be no question that a percentage of cases of the opium habit, small though it be, is even in our day to be attributed to this cause."

C. S. Schmidt-1889.12

After reviewing the growing use of narcotic or stimulating drugs from ancient times down to the present, this author states that the majority of cases arise from the use of morphin to quiet pain but that the euphoria which develops tempts the patient to continue the use of the drug. He emphasizes the psychic effect, stating that in their desire to experience the euphoria patients increase their doses as the effect is lost.

B. H. Hartwell-1889."

On the basis of a survey made in the State of Massachusetts, in answer to a query sent to physicians asking for their opinion as to the cause of an increase in the use of opium, Hartwell reports the following:

"The resolve under which this article is prepared implies, that, if the sale of opium and the evils arising therefrom are increasing, the cause and manner thereof are to be investigated, and remedies proposed; but this investigation, whatever its conclusions, would not be complete without giving the cause of the large sales and extended use of opium, outside of that prescribed by physicians. There are many influences at work to introduce and spread the opium habit. Question No. 2, sent to physicians, asked, of those who. thought that the use of opium was increasing, the cause of such increase. About one-third placed the blame wholly or in part upon the medical profession. Unfortunately, the opium habitue frequently gets his first acquaintance with the drug fro.: its employment for the relief of pain; and, not knowing or realizing the evils arising therefrom, either continues it after the visits of his physician have ceased, or resorts to it for ills real or imaginary, without medical advice, and is a slave to it ere he is aware."

"The opium evil is frequently spread by those who praise it as a remedy, the effects of which they know full well; and still further by those who simply recommend it as a reputed remedy for pain. De Quineey tells us that he bought his first opium on the recommendation of a college acquaintance whom he met by accident. The readiness with which opium can he obtained from druggists without prescriptions, or by reduplication of them, forms not a small part of the cause of the large sales and use of the drug; while in part it must be ascribed to that desire for stimulation or sedation which seems to be the outcome of excessive brain work in the pursuit of earth's idols,—wealth and fame. Example serves not infrequently also, non-users becoming victims by merely seeing an intimate friend or acquaintance indulge in the habit. The following are a few extracts from physicians' replies in relation to the cause of the extended use of opium:

"'I think that physicians are too ready to prescribe, and patients are too ready to take morphia and other opiates for the relief of pain, without due regard to the readiness with which the opium habit is formed.'"

"'Habits of luxury and self-indulgence; increased mental and emotional strain in life; greater predominance of the neurotic or neuropathic treatment, and its accompanying craving for stimulants and narcotics; a desire for stimulation and intoxication which can be concealed.'

"'There are several causes, among which are over-mental strain, and all conditions of life which produce insomnia; using it in place of alcoholic stimulants; the common use of the hypodermic syringe, and quack medicines.'

"'Disinclination of people to bear pain; carelessness on part of physicians, who prescribe opium in its various forms without further knowledge as to patient; continuance of drug; and free, unlicensed sale of opium.'

"'Fear that physicians are often responsible; prescriptions are given and patients have them filled ad libitum.'"

G. Pichon-1889.14

Pichon investigated the charge that the medical man was responsible in general for the formation of morphinism. He introduces his discussion by stating that formerly the therapeutic use of the drug was the only cause of chronic opium intoxication and that it is even yet the most frequent cause. By leaving the drug and hypodermic syringe with a member of the family or even the patient, opportunity is given for repeated unrestricted use. Added to this is the nefarious role of the druggist, all of which results in harm being done before the physician discovers it. The social use, he states, has increased much in the past few years and the expensive and artistic syringes and solution containers that are for sale are quite evidently not manufactured for medical or therapeutic purposes.

In view of the fact that no classes or types of individuals are exempt from the possible development of chronic opium intoxication, Pichon believed it was important to determine what proportion of cases were therapeutic in origin and caused by medical men. He was scrupulously careful in determining this point in his efforts which, he states, he does not conceal were to exonerate the medical man of the charges of carelessness with which he is accused. Unfortunately, he states, the findings of his investigation were far from answering his purpose in this particular. He had thought that in the recriminations directed at physicians there had been much exaggeration. The clinical facts, however, he says, have forced him to admit that on the contrary the generally accepted ideas on the subject are even less than the truth.

From careful investigations he comes to the conviction that medical or therapeutic morphinism is much more common than that from other causes. This is true not only of the older cases but also of those occurring during the last few years, which he says is less excusable as the dangers of morphin and the contra-indications for its use are now well known. But this does not seem to prevent all sorts of carelessness and imprudence. In fact, the author states, the neglect is more common than ever. In arriving at these conclusions he used only cases where the facts and antecedents were well established in order to avoid all criticism.

Out of 55 carefully studied and verified cases of morphinism, 37 were of therapeutic origin. In 34 of these the morphin was ordered by the physician and its use then was neglected entirely and left to the patient himself, a very great mistake. In only three cases was the drug used spontaneously, i.e., without the advice of a physician. In these 34 medical cases, other etiologic factors also entered, according to Pichon.

Pichon states that besides the therapeutic cases there are the euphoric cases described by this term by Fiedler and later by Levin-stein. This class of cases, he believes, is unworthy of pity; they are true morphin drunkards. According to Pichon, this type of morphinism holds the same relationship to the other type that acquired syphilis does to congenital syphilis. They first sought the poison and tolerance came later. This division into these two general classes is important from the viewpoint of etiology, symptomatology, and prognosis.

Pichon believes that there are really only these two general causes of morphinism—those of therapeutic and euphoric origin. The first group may comprise all temperaments and types, as injections of morphin become within a certain length of time a necessity, whatever the type of individual. The second group, on the contrary, would comprise chiefly those who by their temperamental characteristics are drawn toward the unknown and mysterious, to licentiousness if they do not belong to that great class of unstables, abnormals, degenerates, etc., of hereditary origin of whom we have heard so much of late years.

It is in this group that we find intemperates of all kinds as well as the morphinists of euphoric origin.

R. Bartholow-1891.15

"Usually the habit of morphinism is formed in consequence of the legitimate use of the hypodermatic syringe in the treatment of disease. Employed in chronic painful maladies for a long period, it is discovered, when an attempt is made to discontinue the injections, that the patient cannot or will not bear the disagreeable, even painful sensations which now occur."

Bartholow divides chronic users into two classes:

"1. Those who take drug as means of intoxication

2. Those who have had morphine prescribed as a remedy and are forced to continue its use after the subsidence of disease."

William Osler-1894.16

"This habit arises from the constant use of morphia—taken at first, as a rule, for the purpose of allaying pain. The craving is gradually engendered, and the habit in this way acquired. The injurious effects vary very much, and in the East, where opium-smoking is as common as tobacco-smoking with us, the ill effects are, according to good observers, not so striking.

"The habit is particularly prevalent among women and physicians who use the hypodermic syringe for the alleviation of pain, as in neuralgia or sciatica. The acquisition of the habit as a pure luxury is rare in this country."

William R. Cobbe-1895.17

Cobbe reports that out of more than 1200 cases of which he has record, nearly 70 per cent. acquired their condition from medical carelessness.

American Textbook of Applied Therapeutics-1896.18

"There seems to be a strong tendency in many, especially of the neurotic class, to the formation of a drug-habit. Some of those, irrespective of medical advice, will resort to drugs to relieve a craving which for the time is most promptly satisfied by other agents of similar nature. A number first learn the potent influence of drugs to soothe their shattered nervous systems from their medical attendant, who perhaps at first carelessly allows them to know what they are taking, and later permits them to use these agents without his supervision. The responsibility of the physician in such cases is great. Better death or invalidism than the contraction of a habit that degrades, demoralizes and finally kills. But the influence stops not here; the products of conception of these drug-habitues come into the world with the imperfections and weaknesses of their parents intensified. The carelessness and indifference with which many physicians administer such drugs as chloral, opium and its alkaloids is appalling. I have known numerous eases confirmed in the opium habit that apparently could lay the cause of their affliction at the door of their good-intentioned physician. All drugs from the repeated use of which a craving may be established should be employed with great caution. The patient should not know what he is taking and should not be able to have the prescription renewed without the knowledge and sanction of the physician. In the majority of instances in which drugs arc used, for which a habit is easily formed by some persons, the same agent should not be continued long at a time, but should be alternated with other drugs.

"The chief etiologic factor in the development of morphinism is pain, in the broadest meaning of the term—and this may be physical or mental. The next cause in frequency is probably insomnia, with its attendant evils. A large number of morphinists have been, or are at the same time, alcoholics, taking to the syringe after alcohol has been pushed to such an extent that the bodily discomfort produced by over-doses required a stronger and speedier narcotic. From this class of people, moreover, is recruited the largest percentage of drug-maniacs, especially those indulging in habitual dosing with chloral, cocain, etc. In fact, it has been stated that but few cases of pure cocainism have ever been observed. Another class of patients is made up of those of idle and luxurious habits; here the inducement to use morphin is frequently imitation, at times curiosity from reading highly sensational literature (De Quincey, Coleridge, etc.) at other times ennui. Poverty and the misery and deprivations incident to it often lead to morphinism, although the poor are more frequently opium-eaters, it being easier and less expensive to obtain possession of opium than of morphine. Here may be briefly alluded to the fact that a number of patients are started on their downward career by physicians who prescribe or inject the drug recklessly or imprudently, The grave responsibility of the medical profession in this connection is so apparent as to need no further comment."

American Pharmaceutical Association-1903J°

The Committee on the Acquirement of Drug Habits of the American Pharmaceutical Association, E. G. Eberle, Chairman, and Frederick T. Gordon, reported as follows on the etiology of chronic opium intoxication.

"A physician is called for the first time to a well-to-do home; a practice might be secured which would be valuable if he can only show his ability, and he does- there is not very much pain in the prick of a needle, and the result is so quick, so calming—wonderful man—the patient begins to improve at once.

"Society's whirl demands late hours—a little punch, perhaps salad; sleep must be immediate or the man of business will not get any; there are medicines that will produce it quickly; the prescription can be refilled as occasion demands. The next day a severe headache •occurs—no trouble to relieve that, so convenient that many carry it in their pocket, because the headache comes so frequently.

"The man of business must develop the idea which is to yield an extra profit quickly, gain the advantage over his competitor; this may make him nervous, but what of it? That can be remedied by the physician; perhaps he saw an advertisement of a remedy in the paper that would do it, or a friend told him what he is using for the same trouble.

"The pain, irritation, itching, inflammations and other annoyances yield to the influence of some of these delusive drugs; an ointment, a spray, a suppository, all have had their victims."

"The lawyer must have his brain yield its utmost; the preacher must make his sermons interesting; constant strain evidences itself and this must be corrected at once and it can be, and once more they exhibit even greater fluency than before.

"Shall we carry this idea forward to the generation which follows? It is needless; the nursing babe absorbs medicine from its mother's breast as it draws its nourishment; it becomes an habitue with its birth. My mother takes this, I will try a little of it, is another trend of the habit, as well as other association in various walks of life. The negroes, the lower and immoral classes, are naturally most readily influenced, and therefore, among them we have the greater number, for they give little thought to the seriousness of the habit forming.

"I have before me a report from New Jersey; a mother purchased morphine pills several times a week, her son acquired the same habit; another mother takes laudanum, now her daughter does the same. Nearly all report headache remedy habitues; one says if that is a habit, I have about one hundred; I sell about eight gross per year. A Dover's powder habitue was new to me, but knowing the reporter personally, entertain no doubt whatever. Diarrhoea remedies are reported in habitual use by quite a number; One reports a whole family, including young children, addicted. They quickly become morphine and laudanum users. Quite a number report addiction due to physicians in being too ready with the hypodermic injections and suggesting to the patient to send for a few morphine pills. We have many reports expressed in the following, which we copy verbatim from an Indiana letter: 'The most deplorable condition pertaining to the drug habit of late years is that many of the leading lights in the medical profession should become slaves to a vice which they are supposed to combat.' Another writes that quite a number of habitues of his locality lay their acquisition to two physicians who were habitués themselves. This result is natural, but deplorable. The other addictions are ascribed to the use of patent medicines, already described and exhibited in about thirty-eight letters and reports.

"I have not devoted any space to the lower walks of life and will quote two in part. One from Montana reads: 'Most drug fiends of this section come from the Pacific coast. They commence with smoking opium, which becomes too expensive and consumes too much time, so they eat morphine; then they use it by injection because it goes further, then they tip their injection off with cocain because it deadens the pain, and gradually they use more cocain than morphine.' The other report carries with it the same idea relative to morphine and cocain, and says further that cocain fiends are vicious, but that the habit is not as chaining as morphine."

James M. French-1903.20

French states that in most cases in this country the habit is acquired by prolonged use of the drug for relief of pain, insomnia, or to quiet alcoholic nervousness.

Stewart Paton-1905.21

"The development of this habit depends upon a great variety of conditions and each case needs to be studied by itself. Not a few patients gradually become habituated to the vice from the fact that the drug is too often prescribed for long periods of time, by physicians for the relief of pain in chronic neuralgia, sciatica, insomnia and nervousness, or in women for dysmenorrhoea."

He cites cases where this commonly was done by physicians.

Sir William Whitta-1908.22

"Morphinisrn usually originates in the use of morphia or opium which has been prescribed for the relief of physical pain caused by some functional or organic disease. The relief of thc, physical suffering, if the latter is continuous or frequent, calls for increasing doses, till in a comparatively short time enormous quantities arc necessary for the obliteration of the pain. It is not to the condition which culminates in the capacity for swallowing or injecting these colossal doses that the terms `Morphinism' and the 'Morphia-habit' are applicable. It is to the craving which the use of the drug engenders that these synonyms should be applied. Long after the disease which first called for the exhibition of the narcotic has passed away, the individual, having experienced the pleasant stimulating effects of the drug, soon finds that he cannot exist without them. As the pleasurable sensations pass off they succeed feelings of lassitude, listlessness, and depression of spirits which call loudly and irresistibly for further stimulation. The morphinomaniac or the victim of the morphia-habit then finds that he is incapable of exercising his brain or performing the ordinary duties of his calling without resorting to his narcotic; this he uses in doses which for the time bring him up to the level of his normal mental and physical vigour."

R. Dupouy-1912 234922.23'

Dupouy cites the history of one family of four members as an example of what is involved in the giving of a hypodermic syringe and the drug by a physician to the patient. All four—father, mother, daughter and son—became chronic users of opium through the same physician. In summarizing the author states:

"This case is unfortunately not unique, in this same little corner of the world where our confrere—morphinophile and as you have guessed, morphinomaniacpracticed, there can be counted more than two hundred of his patients who have become morphinomaniacs through his attentions."

Ten years later the same author states that the most frequent cause is the prescribing of the drug for painful conditions such as hepatic and renal colic, pelvic pain, rheumatism, asthma, the pain following surgical procedures, etc. Added to the use of morphin in these cases is the fear of pain which the use of the drug creates. This inability to stand pain is a part of the mental make-up of many cases of morphinomania. Such constitutional weakness and psychasthenia, cyclothymia, emotional instability are well known but the therapeutic use of the drug is the more important as without it the majority of these cases would not occur. The causative influence of the initial prescription is seen in a great majority of his cases.

There are doubtless other causes such as the desire to relieve physical or mental suffering, contagion—especially among women—and curiosity in unstable individuals which may act jointly with the first cause.

C. C. Wholey-1913.24

". . . this brings us as physicians face to face with the ugly fact that perhaps the majority of the morphinists in this country today were first prescribed their drug by a physician. Many histories reveal the appalling truth that the administration of the drug as a medicine was needlessly carried on until habit was formed. Usually, I find the patient has at first been ignorant of the nature of the drug; after he has come to the habit stage there is little use to inform him of the harmful nature of his panacea, for he has found that for him it seems good and he will not consider parting with this drug until he has reached that stage where he finds himself so impaired as to be unable longer to hold his own. We find patients who have had given into their own hands the hypodermic needle. The use of the needle practically always insures the formation of the habit."

He also believes that there are two other causes—(1) the passing on of information that opium preparations relieve pain such as dysmenorrhoea, headache, etc., and (2) patent medicines.

James Tyson and M. Howard Fussell-1913.25

"The morphine habit is most frequently acquired as the result of long-continued administration of morphine, to relieve some suffering due to a painful or incurable malady or for insomnia. The influence of heredity in favoring the formation of the habit is acknowledged. Neurotic persons are more apt to become its victims. The victim of alcohol often becomes a morphine fiend, being deluded by early experience with the drug to believe that he can thus overcome the previous more disgusting, if not more terrible, habit."

"Too much carelessness is practiced by physicians in placing morphine in the hands of patients to be used at their pleasure. The hypodermic syringe has wrought untold mischief and should never be placed in the hands of patients. On the other hand, when morphine is judiciously ordered for patients suffering extreme pain only, it is very rarely the case that a habit is established."

G. E. Pettey-1913.26

Pettey believes that not more than 15 per cent. of drug habitues enter upon the use of a drug as a dissipation, or as a sequence of other forms of dissipation. The remaining 85 per cent. usually are brought into the addiction either inadvertently or accidentally.

Pettey adds that probably 75 per cent. of all laymen addicted to the use of drugs owe their addiction to the indiscreet or necessary use of opiates by physicians. Protracted painful ailments force upon them a condition which they are unable afterward to throw off by their own efforts. These victims of the drug are never willing slaves; they are rebels throughout the entire period of subjugation, and they always hope and look forward to the time when they may be set at liberty.

C. J. Douglas---1913.27

"Most physicians are careful, intelligent, and conscientious in the administration of morphine. But there are many individuals in the profession who, through carelessness or a failure to appreciate its dangers, are recklessly prescribing this drug, with the result that morphinism is often acquired, and their patients become helpless slaves. While morphine has a legitimate place in our materia medica, and is a valuable remedy when properly prescribed, yet our best physicians are increasingly cautious in its use, and never employ it except as a last resort. It is humiliating to admit that the widespread prevalence of morphinism is largely due to too careless prescribing by physicians. These prescriptions are often made by well-meaning men, who seem to forget or ignore the dangers and limitations of this drug."

C. E. Terry-1913.28

Terry classifies from the standpoint of cause of original administration 250 chronic users as follows:

Owing to chronic and incurable disease 5 or 2%

From prescriptions of physicians 122 or 48.8%

Through dissipation and evil associates 76 or 30.4%

On advice of friends (not evil associates) 47 or 18.8%

The first and second belong together and were separated to show in how few instances the original malady, for which an opiate was given, persisted and remained a constant cause for its continued use.

Alexander Lambert-1913 28-1922.30

In 1913 Lambert discusses the subject as follows:

"A further experience with the patients has brought out the striking fact that nearly 80 per cent of those addicted to the use of morphine have acquired their habit through legitimate prescribing by their physicians or by self-medication. This has been due to a lack of realization on the part of physicians that it is by small doses, often repeated over a certain length of time, and not by any definite amount taken for the purpose of acquiring the habit as a luxury or as a vicious self-indulgence, that patients drift into the morphin habit. The patients themselves have failed to realize that if they took morphine even in small doses over a certain length of time, the habit would be fastened on them before they knew it. As the majority of patients have drifted into this habit unwittingly through means furnished by the medical profession, it seems justifiable that we should do all possible to popularize among the profession a method of treatment which with a minimum of suffering can relieve these patients of their unfortunate habit. In the majority of cases when once the morphin habit is acquired, the drug ceases to give pleasure. Often the pain for which it was taken has long ceased to exist; it is continued because of the intensity of the suffering when it is withdrawn. In spite of all statements and beliefs to the contrary, patients can not break away from this drug of their own volition unless some treatment is at hand to relieve the intensity of the withdrawal symptoms, because of the intense suffering which these symptoms bring."

In a survey of the literature from September 1, 1921, to March 1, 1922, Lambert compares the statistics on the etiology of chronic opium intoxication obtained by Dr. Hubbard with his own as follows. As to the source of his statistics, Lambert states that he "recently gathered the statistics of 1,593 addicts from the United States and Canada, drawn from persons in comfortable circumstances of life and occurring in private practice."

"The causation of the addiction as given in statistics dominated by a heroin group, as represented by Hubbard's statistics, is vastly different from that given in Lambert's statistics, dominated by a morphin group. Bad associations were given in Hubbard's statistics as accounting for 69 per cent, and other causes 5 per cent. In private practice, bad associations claim only 24 per cent, illness 71 per cent, and unknown causes 8 per cent. In the latter statistics, therefore, it is undeniable that legitimate medication is a factor in bringing about 71 per cent of the narcotic addiction.

"A detailed study of the causation of drug addiction, based on Lambert's statistics, is of interest. In the cases collected by him 17 per cent of the men and 29 per cent of the women acquired their addiction from physical pain—the pain following operation or injury, the pain of gall stones or renal colic, or the steady grinding pain of headache or neuritis. In only 2 per cent of the women was pelvic pain given as the cause. The pain of rheumatism and gastric diseases accounted for about 2 per cent of the causes in both men and women, and was about 5 times more frequent as a causal factor than the pain of chronic nervous diseases or of heart diseases. Acquisition of the habit through the use of patent medicines is mentioned in a few instances only. Sickness and indefinite pain are given as the cause by 14 per cent of the men and 23 per cent of the women. Asthma is given in 2 per cent of each and mental strain, in the form of worry, unhappiness and sorrow, in 21 per cent of the men and 19 per cent of the women. Overwork and fatigue caused the addiction in 16 per cent of the men and 20 per cent of the women. It would seem from these figures that men bear physical pain better than women—at least so far as seeking relief in morphin is concerned—and the same is true of sickness and indefinite pain. Men, however, succumb more readily to mental strain, and in the quest for relief are especially prone to turn to alcoholism, later turning to morphine to get rid of the first narcotic. Overwork and fatigue are particularly prone to drive men to seek relief in some narcotic, and morphine is apparently very frequently used for this purpose, especially in certain occupations.

"A comparison of the causative factors in relation to the different drugs reveals a noticeable difference in the percentages. Among morphine addicts, 40 per cent of the men and 25 per cent of the women took the drugs for sickness; indefinite pain and bad associations claimed only 13.5 per cent of the men and 8 per cent of the women. Of the 140 taking heroin 81 per cent of the men and 70 per cent of the women took it because of bad associations, but only 6 per cent of the men and 3 per cent of the women took it for sickness. Morphine and cocain addiction was attributed to overwork and fatigue by 32 per cent of the men; of the women taking this combination, none took it for overwork, but 37.5 per cent took it because of the pain following operations, and an equal number because of bad associations. Of those taking morphine and alcohol, 25 per cent of the men took it for overwork and fatigue and 18 per cent of the women for this cause. Sickness and indefinite pain caused 17 per cent of the women to seek relief in this combination and 18 per cent of the men. Bad associations caused the addictions in but 12 per cent of the men and 8 per cent of the women."

P. M. Lichtenstein-1914.31

Lichtenstein reports on a study of 1,000 cases 82 representing 5% of the average number of prisoners admitted to the City Prison, Manhattan, during one year. He states:

"As regards the acquisition of the habit, I have ascertained the following: The number of victims who directly trace their addiction to physicians' prescriptions is very small; I have found but twenty such people out of 1,000. Most of these victims were women who had been suffering from tubal disease. One woman had been severely burned and had to be given opiates to quiet her. The information given by physicians to patients, that they had been receiving morphine, cocaine, etc., is to be deplored. Patients should be kept in ignorance as to medication. Other prisoners have stated that they had been induced by friends to take a 'sniff' of the drug, which is variously termed 'happy dust', `snow', etc.

"Several individuals have come to the conclusion that selling 'dope' is a very profitable business. These individuals have sent their agents among the gangs frequenting our city corners, instructing them to make friends with the members and induce them to take the drug. Janitors, bartenders, cabmen have also been employed to help spread the habit. The plan has worked so well that there is scarcely a poolroom in New York that may not be called a meeting place of drug fiends. The drug has been made up in candy and sold to school children. The conspiring individuals, being familiar with the habit-forming action of the drug, believe that the increased number of 'fiends' will create a larger demand for the drug, and in this way build up a profitable business.

"Many individuals begin taking a narcotic for insomnia; this is particularly true of physicians and nurses. I have treated many nurses addicted to morphine taken hypodermically. Others take the drug to ward off sorrow and care, and still others are compelled to take the drug because of severe pains caused by locomotor ataxia, cancer, etc. The number of young people addicted is enormous. I have come in contact with individuals sixteen and eighteen years of age, whose history was that they had taken a habit-forming drug for at least two years.

This includes girls as well as boys."

Lucius P. Brown-1914.33

Brown states that his investigations indicate that "well over fifty per cent. of existing cases of narcotic addictions are due to the indiscreet administration of drugs by physicians."

Archibald Church and Frederick Peterson-1914.34

". . . it is a sad commentary on the heedlessness of some medical men, but the family physician is responsible in almost every case of development of the morphin habit and its far-reaching consequences. It should be looked upon as a sin to give a dose of morphin for insomnia or for any pain (such as neuralgia, dysnienorrhea, rheumatism) which is other than extremely severe and transient."

Clifford B. Farr-1915.35

Basing his opinion on observations at the Philadelphia General Hospital, Farr states that in many cases the morphin was taken merely as an indulgence, but other persons attributed it to medication begun either on their own responsibility or on the advice of a physician.

L. L. Stanley-1915-1918.36 37

"The causes of morphinism are many. Foremost perhaps, it is brought about by efforts to combat the distress and ravages of pain. Physicians of the last decade have been too eager to allay pain merely by slight injection of morphine, and, in fact many have not hesitated putting the preparation in the hands of their patients, with the result that people with primarily a minor ailment have been unwittingly put under the defiling influence of this drug.

"Secondly, there are diseases which require opium derivatives not only for the allaying of pain, but for relief from the condition. Asthma may lay claim to morphine as one of its cures. Bronchitis and pulmonary affections demand heroin, while peritonitis and derangements of pelvic organs require a certain amount. Chronic and incurable diseases as cancer, aneurism and some kidney diseases are tided for awhile and rendered more tolerable by the suffering victim.

"Besides pain and disease, there is a nervous strain of modern life, or the `Mania Americana', which is temporarily relieved by the soothing effects of opium, but which is subsequently made worse by the continued use. Physicians are prone to its use. They are in daily contact with the drug, and although they realize the firm grasp with which it takes them, many endeavor to fling aside their troubles and cares or to stimulate themselves to further efforts by partaking of this hemlock cup. Society women who have undergone a trying season of parties and social functions, ever endeavoring to outrival their neighbor in social splendor, often find themselves wrecked in mind and body. Too often they indulge in opium to calm their 'shattered nerves. As with the higher classes, so with the lower. Prisons and penitentiaries are filled with fiends, many of whom were produced after they had entered the dismal walls. Almost every brothel has its victims. And even the dweller of the gutter and slum is not exempt. Conditions of life are such, their pains and tribulations are so great that the miserable victim seeks periods of relief and contentment in the use of this death-dealing substance."

Later in 1917-1918, reporting on a study of 100 persons at the San Quentin Prison, Stanley 37 discusses the way in which these prisoners began the use of the drug as follows:

"Knowing the relatively tender ages at which this habit is formed, it is of interest to find out just how the use of dope was begun. To this, question there were a great many answers.

"Fifty, or one-half, began by associating with bad companions at night, frequenting dance halls, saloons, poolrooms, and later 'joints' where they were induced to try the pipe. Very few who ever try the pipe have will power enough to refrain from doing the same thing again at some future date when they are importuned to do so by their evil associates. Fifteen per cent were induced and educated to this addiction by women of the underworld, who perhaps took a fancy to the young man and persuaded him to go with her to indulge in this insidious vice. Eleven claim that they learned to smoke opium in jails and penitentiaries.

"In the not far remote periods of the two California penitentiaries it was not difficult to have opium smuggled inside the walls, where men not cured of their addiction would use the drug and induce younger prisoners to be 'sports and take a shot.' At the present time, however, a close watch is kept at the prisons and no contraband is allowed to enter. But at the county jails no such rigid vigilance is in force, and it is said by the prisoners who have come from those jails, that it is a very easy matter for any one who has money to have the drug brought to him. It is in those jails that many a young man is induced to become an addict to this habit because he wishes to show his toughened cell mates that he can be as bad a man as any of them.

"Sixteen others claim that they began the use of dope on account of various sicknesses, such as rheumatism, accidents, syphilis and other forms of disease in which there was a high degree of pain. In some of these cases, it might have been the fault of the physician or of the nurse that the patient found out what he was receiving for his pain and in this way led him on to his addiction.

"One patient examined at San Quentin began by taking paregoric for stomach ache, with which he was troubled to a considerable extent. He was given this by his mother when he was at the age of seven years. From this frequent dosage he acquired the habit, the persistence in which finally landed him in jail. A second addict stated that when he was in high school in a certain town in Nevada, it was a fad among the boy and girl students to visit Chinatown regularly, where they smoked opium. Another told that while in the Alaskan fisheries, he, with a number of other men, was given morphine to stimulate him to greater efforts and to work at higher tension so that all of the fish might be taken care of in a limited time without pecuniary loss to the company. At the end of the season, he was, with a number of other men, a confirmed addict."

J. McIver and G. R. Price-1916.38

These authors report as follows on an analysis of 147 cases at the Philadelphia General Hospital:

"When questioned as to why the habit of opium-smoking had been formed, all who so used the drug stated that it was first indulged in for pleasure and acquired through association in the 'tenderloin'. Of the morphin users, the largest number, twenty-eight, learned of the effects of the drug through its hypodermic administration by a physician or through a physician's prescription. The next largest number, twenty, first used morphin as an alternate or substitute for opium-smoking. Eighteen acquired the habit through association as a social diversion; ten took morphin for the first time on their own initiative for the relief of pain or insomnia; six used it as a substitute for heroin and five were made victims of the drug while patients in various hospitals in our own city. Of those who used the alkaloid heroin, the largest number, fifty-six, acquired the habit through association. Twenty took heroin instead of smoking opium, or as a substitute for morphin, when these drugs became difficult to obtain. The remaining seven resorted to the drug to relieve the effect of alcoholic excesses, insomnia, headache, etc.

"While these figures prove conclusively that a vast majority of cases of opium-smoking, heroin and cocain sniffing are acquired through association, we would emphasize the fact that the largest single factor in the production of morphinism has been professional medication."

C. B. Burr-1916.3°

Burr states that he is not prepared to admit that

". . . the majority or more than a large percentage of cases are due to the injudicious prescription of the physician. While some develop because of the continuance of a physician's prescription (often without his knowledge) for an undue length of time, many originate from pure self-indulgence. It is true in all probability that morphine is used too liberally in the treatment of neuralgic conditions. It is too frequently the first resort and one dose is followed by another and another until the patient is under the tyranny of the habit."

"A fruitful source of opium and morphine addiction is the presence of one mischievous person who is a confirmed habitu6. I have known a whole neighborhood to be infected indirectly by a single individual of this character."

C. .E. Sceleth-1916.4°

"I would call attention to certain rules in the use of morphin by physicians by the observance of which the spread of the habit can be materially restricted. It is a terrible stigma on our profession that in 75 per cent of the cases of chronic morphinism, the drug was first administered by a physician: and that in less than 10 per cent it was not given for its prime indication—incurable pain."

J. Rogues de Fursac and A. J. Rosanoff-1916.41

"The study of the etiology of morphinomania involves the consideration of two distinct questions: (1) What individuals are apt to become morphinomaniacs? (2) How does one become a morphinomaniac?

"(1) What individuals are apt to become morphinomaniacs?

"Morphine is no longer, as it was formerly, an aristocratic poison limited to the upper classes. 'Even rural populations are no longer exempt from the contagion; and the fault is chiefly with the physicians.'"

"Morphinomania is especially frequent among those who, on account of their profession or surroundings, can readily procure the poison; such are physicians, their wives, medical students, pharmacists, nurses and laboratory attendants.

"As in the case of alcoholism, the character of the soil is here also an important factor. The less energetic and mentally stable the individual is the more likely he is to yield to the seductive influence of the poison. Thus we find that morphinomaniacs are often degenerates.

"(2) How does one become a morphinomaniac? —In many ways, but chiefly:

"(a) Through medication; many subjects receive their first injection for the relief of some painful affection as hepatic colic, neuralgia, or tabes.

"(b) Through curiosity; this occurs especially among degenerates, idlers, individuals who are tired of all ordinary pleasures and are longing for new sensations, and whose unfortunate tendency is still farther stimulated by the example and proselytism of old morphinomaniacs.

"(c) Through the craving for a sedative or for relief from mental suffering; this occurs in the overworked (soldiers in time of war or young people during difficult examinations) and in those who are driven by some misfortune or ill-luck to seek in morphine a consolation for their sorrows and disappointments."

W. A. Bloedorn-1917.43

In connection with a report of a study of the drug cases at Bellevue Hospital, Bloedorn says:

"The number of individuals who begin the use of drugs through illness, insomnia, or persistent pain, while constituting a large aggregate, is believed to form a relatively small percentage of the total. The great majority take their first step through being unfortunate enough to meet and associate with addicts. The recruit is often invited to participate in the use of the drug, and these associates seem never loath to provide him with this means of becoming a confirmed habitue.

"This is particularly true of the large centers of population, and there can be no doubt that overcrowding, congestion, insanitary surroundings, and a lack of the facilities for healthful recreation are predisposing factors in drug addiction. Under these circumstances a drug addict becomes a focus of infection, as it were, and through contact with susceptible individuals serves to spread the evil. With this sort of environment the drug habit is considered to be highly contagious, particularly among minors."

F. X. Dercum-1917. 44

. . . physicians cannot rid themselves of the great responsibility involved in the abuse of morphin, for it must be admitted that it is too frequently prescribed for comparatively trivial affections, and that some physicians are altogether too ready with the use of the hypodermic syringe. Prescriptions for the relief of pain should be for a few doses only."

Carl Scheffel-1918.45 46

Scheffel, after asking the question, "What has the medical profession done to prevent and cure drug addiction?" answers "Very little."

"We learn from medical history that the medical profession is directly responsible for an overwhelmingly large percentage of drug addicts; from the same source we likewise learn that in caring for these unfortunates medical fads have held, and still are holding sway. Pecuniary interests seem to have crowded out scientific pursuit, and little real good has been accomplished in either the eradication of the habit, or the cure of its victims.

"If such is the state of affairs among those whom we look up to for legal, moral and physical guidance, what can we expect the public to know about these dangerous conditions."

In a later article, Seheffel 47 analyzes the etiology of fifty cases of the chronic use of drugs of which 45 used opium derivatives. The result of this study shows that about 93 per cent. of the cases of chronic opium intoxication were caused either through the inability of the profession to relieve or cure difficult chronic conditions or by the careless and promiscuous administration by physicians of dangerous habit-forming drugs over long periods of time and many times in conditions where these drugs were not absolutely indicated. Only 7 per cent. resorted to the use of drugs entirely of their own accord and not on account of some form of illness for which an opiate was prescribed.

Scheffel states that it should be emphasized that physicians are making more addicts to these drugs than they would like to admit. In insomnia, etc., it is not justifiable to give these drugs over long periods of time as there are plenty of other therapeutic agents available.

William A. White-1918.48

. . . as in other varieties of narcomania the most important cause is the neuropathic diathesis. In this class of patients the habit is often initiated by the use of morphine to relieve the periodic pains of neuralgia, tabes, dysmenorrhea, rheumatism, etc., or the mental depression incident to worry, loss of position, grief and the like. A great many cases are unfortunately traced to the carelessness of physicians in prescribing the drug, and as if in retribution medical men furnish the largest quota of sufferers (fifteen per cent.)."

Jacob Diner-1918.48

"The predisposing causes leading to drug addiction, no doubt, must be looked for, first in the social condition and conditions of labor which obtain among the civilized people. We all know that as civilization progressed the demands upon man became more and more insistent. Greater energy outlay is demanded daily, and to meet these requirements stimulation, either mental or physical, become obvious, nay, become almost imperative. Some of us obtain that stimulation by change of work, by vacations, by hobbies which we enjoy and which give us a mental or physical rest or both. Others, less careful perhaps in the choice of their relaxation, have recourse to the handy but injurious drug.

"Once in a great while the members of the medical profession are the cause of the contraction of the drug habit. It is quite often a relatively easy matter to relieve a suffering patient from pain by the administration of a narcotic. While I fully realize that it is the duty of the physician to allay suffering and cure disease, yet I believe we should lay more emphasis on the latter part of the sentence, that of curing disease rather than to allay suffering. It is for this reason that I wish to emphasize the wrong which the physician commits when he has recourse to the administration of a narcotic for the purpose of easing suffering rather than attempting to analyze the cause of the suffering and removing that cause.

"Another and perhaps a most important factor in the promulgation of the use of narcotics has come into vogue recently. As long as the sale of narcotics was not surrounded with so many restrictions and as long as the legitimate use of narcotics was made relatively easy and the obtaining of narcotics for legitimate purposes was within the reach of the suffering public on the one side and within the scope of the prescribing practitioner on the other, there was no special inducement for any man or class of men to increase the use of narcotics. But within recent years, whether necessary or not, a number of laws, intended of course honestly to reduce the abuse of narcotics, have been passed both in the State legislative body and in Congress, and thus the obtaining of drugs has been made relatively, I say relatively, more difficult.

"Because of this increasing difficulty those people who think they have to have the narcotic are willing to pay almost any price in order to obtain it. Commercial history has proven that wherever there is a demand there will be the supply and so, in the case of narcotics, the demand being there it was but a short time before the supply was available. Naturally, of course, that supply was there merely because of the profit there was in it, and the more difficult it was made for the genera, public or even for the physician to use the narcotic or to prescribe it, the more lucrative was it made for those people to handle it; in fact, it became an inducement for them to increase the use of narcotics by illegitimate means in order to increase their profit."

New York Psychiatrical Society—Public Health Committee,

New York Academy of Medicine-1918.5°

These organizations made a number of recommendations concerning the causes and prevalence of drug addiction, the methods of treatment for relief and treatment for cure and the legislation needed for the dispensing and control of drugs. In regard to the causes and prevalence of drug addiction, the following recommendation was made:

"4. We recommend that a thorough study be made of the extent and causes of drug addiction, such studies for example as will give information as to the age, sex, occupation and environment and the mental and physical condition of victims of the drug habit and as to how their habit was formed.

"With regard to the cause and frequency of the habit, we can make only provisional statements. So far as our knowledge goes, the drug habits formed as the result of long and painful sickness, as the result of painful surgical operations, and as the result of mental causes like sorrow, depression and apprehensive states, constitute at present as in the past, a negligible proportion of the total.

"The habit has largely been formed in recent years by association and Imitation by boys and young men and women who are often quite ignorant of the dangers of the habit. Examination of a long series of addicts at Bellevue Hospital shows that about four per cent formed the habit through the advice and prescription of unscrupulous physicians who utilize what is known as the reduction treatment as a cover for their reprehensible practice."

G. E. McPherson and J. Cohen-1918.51

These authors made a study of 100 cases of drug addiction entering Camp Upton, New York. From this survey, they report that

" . . . ten per cent of the 100 men examined attributed their contraction of the drug habit to medication by professional advice. Eighty per cent admitted they were introduced to drugs, by their friends, their friends very largely being immoral women. The social stimulus seemed in a large majority of cases to be the active agent in propagating addiction."

Special Committee of Investigation appointed by the Secretary of the Treasury-1919.52

"Data assembled by the committee show that the habit of using opiates or cocaine is acquired through association with addicts, through the physician, and through self-medication with these drugs, or patent or proprietary preparations containing the same. The first two ways in which addiction is acquired are of about equal importance at the present time, the last being of lesser importance in the light of replies received to the questionnaires sent out.

"With respect to this phase of the subject, the committee finds that addicts may be divided into two classes, namely, the class composed principally of addicts of the underworld and the class which is made up almost entirely of addicts in good social standing.

"The addict of the underworld, in a large majority of cases, acquires the habit of using these drugs through his or her associates. This is probably due to the fact that addicts of this class make use of heroin and cocaine most frequently, these drugs being employed as a snuff. It is therefore an easy matter to treat a companion to a sniff of the 'dope.' In addition these drugs are made use of by 'white slavers' in securing and holding their prey, and by prostitutes in entertaining their callers.

"With respect to the addict of good social standing, the evidence obtained by the committee points to the physician, as the agent through whom the habit is acquired in the majority of cases. Some, however, become addicted to the use of these drugs through self-medication while a few first indulge as a social diversion."

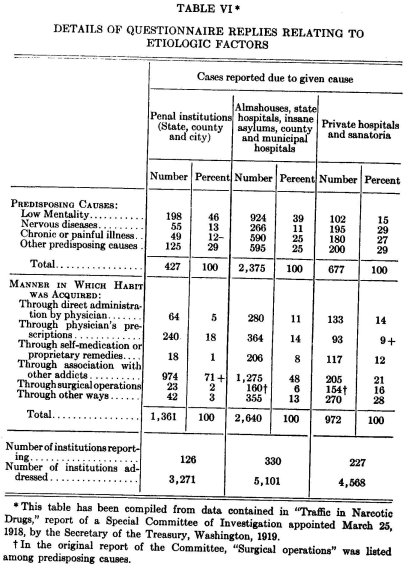

Special questionnaires were sent out by this Committee to various groups and among other questions included one requesting a report on the manner in which the "habit" was acquired. The replies to this question are tabulated below.

The committee reports that questionnaires to chiefs of police did not elicit figures but the causes in order of importance were given as follows: Physicians' prescriptions, association with other addicts, prohibition, chronic diseases, curiosity, prostitution, use of patent medicine, use as a stimulant, idleness, use by dentists.

All questionnaires sent to state, county, and municipal health officers brought no figures as to causes but gave the following in order of importance: Physicians' prescriptions, chronic diseases, prohibition, association, use of patent medicines, prostitution, for stimulation, through curiosity.

It should be noted that the above report includes cocain users as no distinction is made between opium and its derivatives and cocain.

M. C. Mackin-1919.53

Mackin gives the following as the causes of the misuse of morphin.

First, by administering drugs because of the surgical treatment over a protracted period.

Second, by protracted medication for bodily ailment and disease.

Third, by insomnia.

Fourth, by general ill .feeling, sorrow and care.

Fifth, by bad example which is especially true of physicians' wives.

"The chief obsession of the drug addict is to gain converts to the cult. Often the experiment is made 'just for fun' but indifference soon turns to longing. The pleasurable sensation which the injection produces urges to the second injection when the effects of the first have worn off, and thus necessitates in a short time an increase of the dose with a development of the imperious craving.

"This is a craving which causes men to dare all danger, run any risk, forfeit friendship, destroy affection, relinquish honors in possession or in prospect, to associate with criminals, reduce themselves to beggary and those dependent upon them to pauperism, want and wretchedness, expose their families to contemptuous pity, and defy any fate, all in order to gratify this craving."

James M. Anders and John H. Musser-1920.54

"The climate, country, and nationality have a certain disposing influence in the development of opiumism and morphinism. In the opium-growing parts of Asia, as in China, India, and Persia, where the climate is warm, enervating, and conducive to physical and moral abandonment during the greater part of the year, and in Turkey also, opium-eating and smoking habitues are as numerous as alcohol habitues are in Europe and America among the Caucasians.

"Women are more commonly the victims of morphinism than men, except physicians and druggists as a class.

"Ennui and an idle spirit of irritation and adventure among the sensation-loving and luxurious sometimes sow the seeds of an indulgence in narcotics that bring forth fruitage in the form of a fixed habit.

"The incautious prescribing of morphin and the too ready hypodermic use of the alkaloid by physicians in treating various cases of pain are not infrequently the cause of morphinism. Overwork of the brain, great business or social strains, prolonged worry and anxiety either with or without work, insomnia, remorse, idleness, and secret vices, are the most common predisposing agents of the morphin habit.

"Paregoric, laudanum, chlorodyne, and 'soothing-syrup' are drunk to a frightful extent in large cities among the poor and miserable, and cause great disturbance of the health of the habitués. Heroin is being used to an alarming extent in spite of all efforts to limit its sale."

S. Dana Hubbard-1920.55 56

Hubbard made a study of the cause of chronic opium intoxication

in the cases passing through the New York City Narcotic Clinic from which he reports the following:

"Most—in fact 70 per cent—of the addicts, in our clinic, are young people; they have had no really serious experiences--surely none sufficient to occasion a desire to escape all life's responsibilities by recourse to the dreams of narcotic drugs; therefore the one and only conclusion that we can arrive at, is that the acquirement of this practice—drug addiction—is incident to propinquity, bad associates, taken together with weak vacillating dispositions, making a successful combination in favor of the acquirement of such a habit. Being with companions who have those habits, they, in their curiosity give it a trial (similar to the acquirement of cigarette smoking in our young) and soon have to travel the same road to their own regret."

"This appears to vary with localities. Our experience points, in the great preponderance of instances, to bad and vicious associates, 69 per cent from their own statements.

"Raising the morale of our public assemblies for the young and making programs in our shops and factories may materially aid in preventing this reprehensible practice.

"Efforts to prevent and avoid mental and physical fatigue in industry with a careful regard for opportunities for acquirement of this habit by the industrially employed is strongly indicated."

Hubbard gives the following table of reasons assigned by addicts for acquiring the habit:

"Bad associates 5,190 69%

Illness 1,994 26%

Other causes 280 5%"

Later Hubbard 56 writes:

"Bad associates and evil environments are the chief causes producing addiction among youthful habitués in this city. Of 7,464 cases observed from April 10, 1919, to January 15, 1920, in the department of health clinic, 3.5 per cent were morphinists, while 96.5 per cent were heroinists."

"The etiology of narcotic drug addiction is not unusual or complicated. It is a natural sequence of indulgence in narcotics for a more or less variable period. The very susceptible acquire the habit in very short periods of time, some as short as ten days (some girls state that after having sniffed three or four times, the withdrawal symptoms were marked); but usually it requires a number of such indulgences. Medically considered, it is thought that any one taking repeatedly a drug for a period of from three to five weeks is in grave danger of becoming an addict. When addiction has been established, it is usually impossible for the individual to discontinue the use of the drug without outside assistance.

"In the clinic, 7,464 cases were cared for; and while gradual reduction (one-half grain every other day) was the custom, yet it was extremely difficult to hold our patients to schedule. A number openly opposed reduction ; and when the amount was cut down about half, they left the clinic, not to return, or to return under a different name to commence again at the maximum dosage (15 grains) and pursue another course of reduction. Many were detected doubling in this manner. Of the total mentioned above, less than 2,000 availed themselves of hospital aid, 23 per cent being the actual admissions. This demonstrated that they either feared to undertake a cure or else did not want to be cured.