VIII A Cross-Cultural Study

| Books - Society and Drugs |

Drug Abuse

This chapter describes some aspects of the use of several mind-altering drugs in those nonliterate societies for which data are available. It also identifies relationships between styles of drug use and certain culture characteristics. It describes cross-culturally consistent relationships among several different aspects of drug use and presents the results of a test of relationship between one style of use for one drug and certain characteristics of nation-states. Given the limitations of data and method, the study should be considered exploratory rather than definitive.

The thrust of the work reported is consistent with earlier cross-cultural investigations on alcohol as initiated by Horton (1943 sup-plemented by Field (in Pittman and Snyder, 1962), and recently ex-tended by Bacon, Barry, and Child (1966). These cross-cultural studies are, in turn, related to a number of single culture investigations which describe or account for drug-use styles in terms of other cultural or social characteristics. Illustrations from the field of alcohol studies in-clude Bunzel (1940), Lolli, Serianni, Golder, and Luzzatto-Fegiz (1958), Blum and Blum (1964), Connell (1965), and Sadoun, Lolli, and Silverman (1965 ). Extending beyond investigations of whole cul-tures or normal samples drawn from such cultures, a considerable num-ber of studies link styles of drug use in particular groups within a given society to other aspects of the person and his environment. Given the consistent findings which show that drug use is a social and psychologi-cal phenomenon, as well as a pharmacological and physiological one, one might expect that a systematic analysis of cross-cultural data would reveal certain regularities in the use of drugs other than alcohol, and between drug use and other characteristics of societies. It is that prem-ise upon which our work is based.

METHOD OF APPROACH

Initially, a search was made for descriptions of drug use in cul-tures of varying complexity. Therefore, we originally included nation-states as well as nonliterate societies. This proved unsatisfactory since, for the most part, drug use in nation-states appears to vary consider-ably, depending upon the ethnic, class, generational, and status mem-bership. ( See Cisin and Cahalan [1966] for an illustration with refer-ence to alcohol.) Thus, descriptions of the use of the lesser studied drugs (cannabis, stimulants, hallucinogens, medical opiates) threatened tô be unreliable when reported for nation-states as a whole. For that reason, with one exception, we restricted our work to a description of mind-altering drug use in nonliterate societies. That exception is the use of drug "abuse" data for nation-states. For both the nonliterate sodeties and nation-states, we tested for relationships between styles of drug use and other characteristics of societies. As a source of characteristics of nonliterate culture, we relied on Textor (1967), and for nation-state characteristics on Banks and Textor (1963 ).

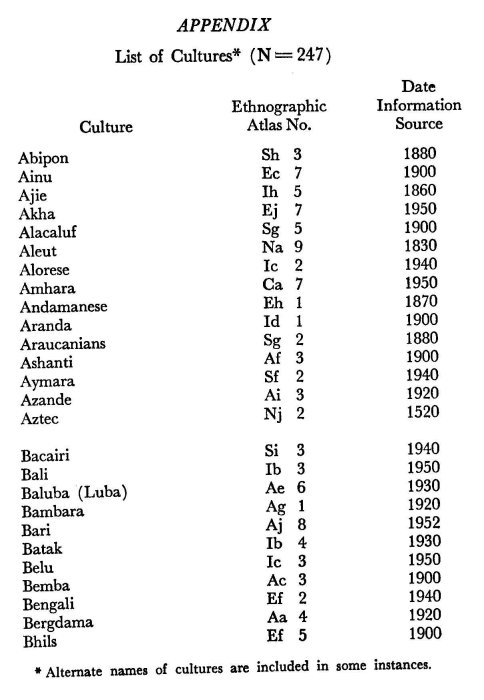

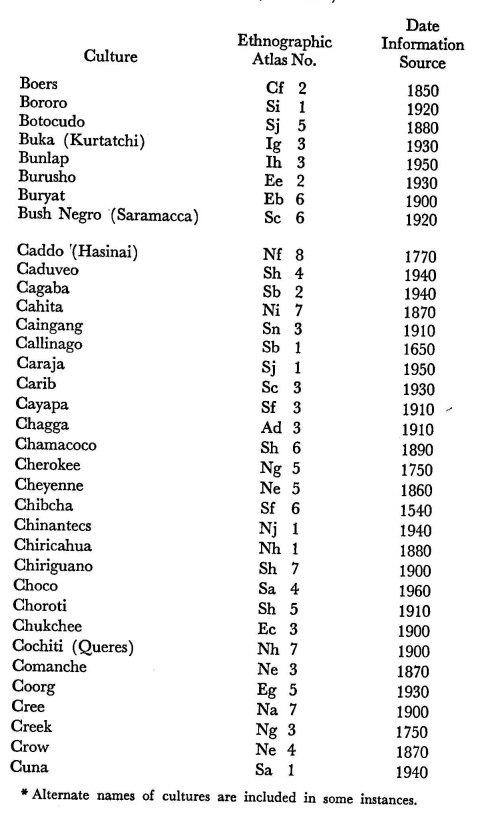

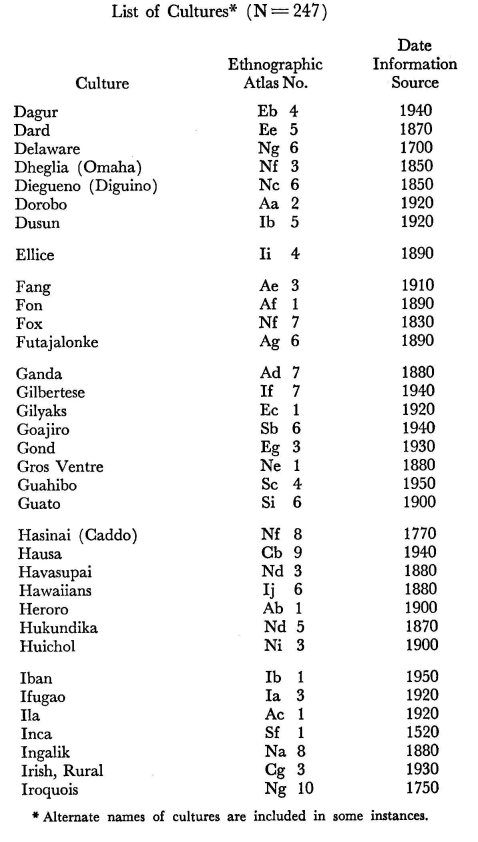

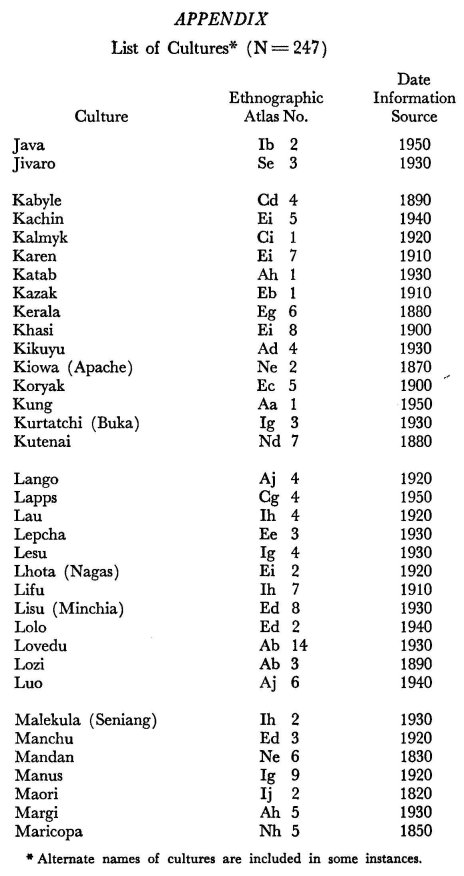

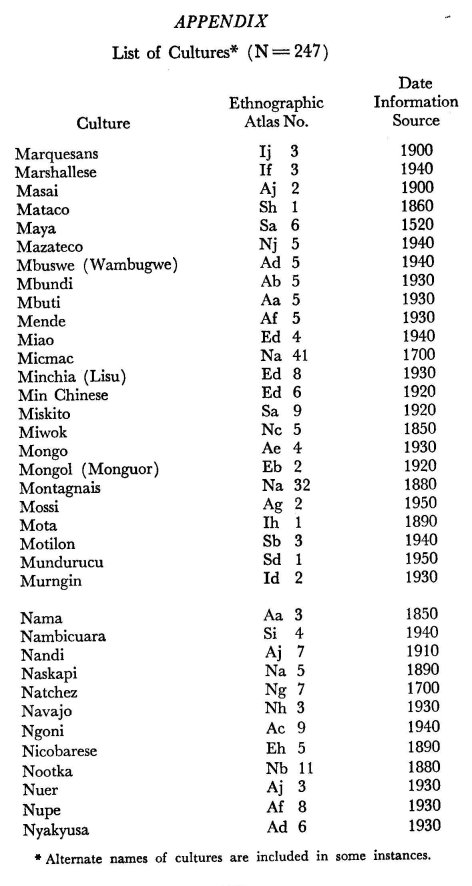

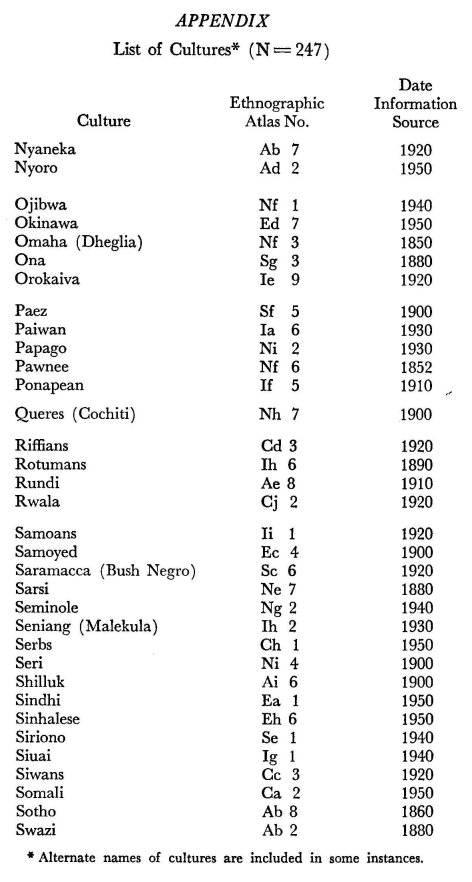

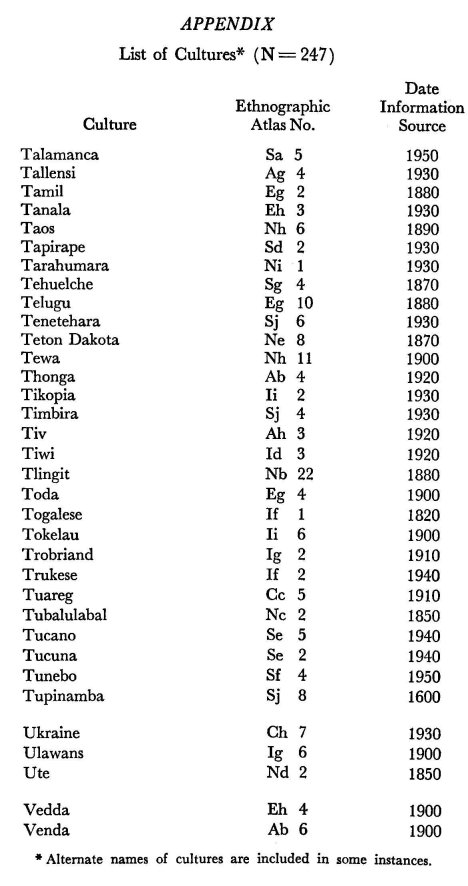

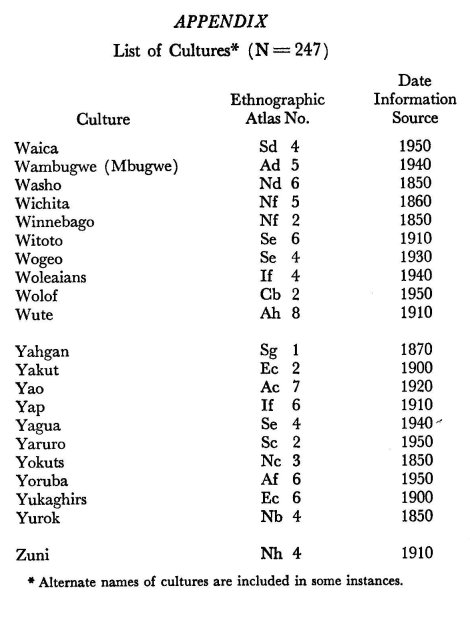

With reference to nonliterate societies, we sought data on alco-hol, tobacco, natural hallucinogens (such as peyote, fly agaric, datura, and parica), natural stimulants (betel, kola, khat, kava, and so on), cannabis, opium, and coca-cocaine. No attempt was made to describe the use of medically employed synthetic pharmaceuticals. Our primary data sources were the Human Relations Area Files (HRAF ) at Yale and (in limited number) at Stanford and supplemental reading con-ducted as part of our other work in social and epidemiological psycho-pharmacology (see Blum in Joyce, 1967). The appendix contains the list of nonliterate cultures used.

Using standard coding sheets, raters recorded styles of drug use as follows: (1) extent of drug use; (2) change,s in use over time; (3) availability; (4) how the drug was introduced; (5) primary present source; (6) pre,sence of abuse as defined by within-culture elements; (7) presence of abuse as defined by nonnative observers; (8) circum-stances of use; (9) settings and inferred intents in use; (10) attitudes (supports and restraints) surrounding use; (11) differences between the sexes in use; (12) differences in age groups in use; and (13) status differences in use. Toward the end of our data gathering, the mono-graph by Child, Bacon, and Barry (1965) was published. In those instances in which their data were more complete than ours, we incor-porated their findings into our descriptive categories, provided no con-flict existed between their sources (when these were evident for ratings) and ours. We obtained a final sample of 247 nonliterate societies for each of which at least one aspect of use of one mind-altering drug was described.

RELIABILITY OF DATA

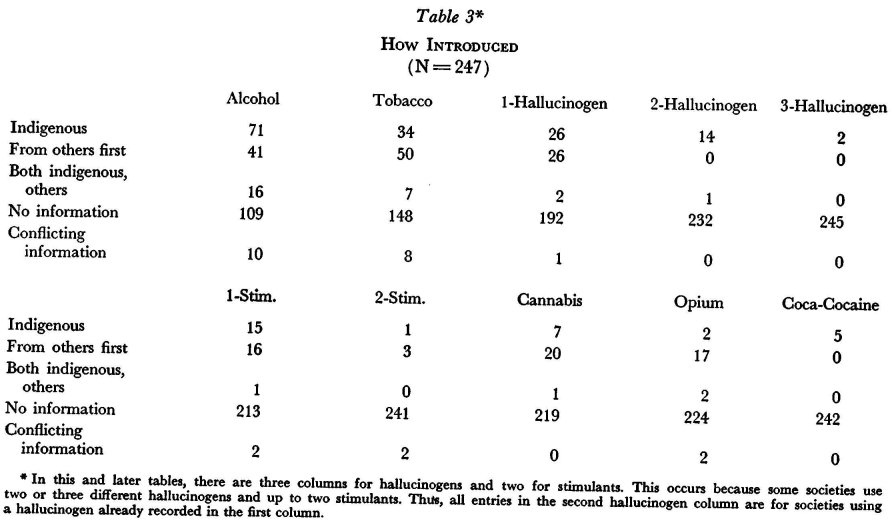

A constant problem was that of reliability. Frequently, different observers of a culture offer contradictory observations. Two different ratert reading the same material may disagree on their coding. Further, the same rater reading the same source on different occasions may sometimes be inconsistent. In addition, clerical unreliability may occur when codes are transferred to Balgol sheets, and to cards for computer processing. Table 3 illustrates the problem of contradictory observa-tions since conflicting reports occurred in 29 out of the 172 (17 per cent) cultures about which any alcohol data were available. This per cent is not an estimate of proportionate total unreliability, for it is de-rived only from cultures where two observers disagreed. When only one culture description is available, there can be no test of reliability (unless of an internal-consistency sort)., and when there were three or more different reports on one culture, our procedure called for record-ing the majority description—rather than recording a "conflicting-in-formation" entry, which we treated as a "no-information" entry and did not include in our analysis. As a test of agreement among raters on the same material, some of the HRAF material at Stanford and Yale was independently coded by two different persons. Using a measure of agreement between raters based on information-bearing codes alone (excluding the "no-data" entry)., one obtains an interrater reliability of .82. Induding the "no-data" codes, interrater agreement rises to .96. In the cases when one of our raters reported differently for cultural observations on two occasions (occurring 8 per cent of the time in a test run of 712 coding operations), our procedure was to compare it with codes entered by a second rater and choose the most commonly selected code; thus, we have not excluded such cases by placing them in the "conflicting-information" category. As a second-step check, one showing 73 per cent agreement, two raters compared three sets of orig-inal code entries on those cultures where three different sources or rat-ings occurred (one set derived when one rater repeated ratings a second time). In another comparison, we examined our descriptive entries for forty-nine cultures against the data from Child et al. For 405 coding operations, there is full agreement between ours and the Child data on only 109 items (34 per cent) and complete disagreement on 91 items (22 per cent). For 84 items, Child et al. reported no entries where our sources gave data. For 67, Child has data where our sources provided no information (16 per cent). Additionally, for 91 items the Child report displays internal conflict.

The foregoing illustrates reliability problems arising from a se-ries of tests of the data. Although disagreement between raters and in-consigtency in repeat observations by the same rater are apparent, the largest source of error seems to come from disagreement in reports by observers of a society, as is shown in our "conflicting-information" entries, in Child et al. inconsistency reports from several sources, and in the disparity between our sources and the Child material (presumably arising from other than HRAF since interrater reliability using the File sources is high). Our confrontation with the reliability problem has not led us to solutions other than the procedural ones noted (ma-jority judgments when possible, not using culture data when conflicts are not reconcilable by majority judgment). We must assume that the unreliability of sources and, secondarily, of ratings contributes to an unknown, but probably considerable, error in the cross-cultural method as we employ it here.

Our interest in learning whether cross-cultural inquiry would yield variables related to similar styles of drug use for several drugs, or variables related to particular drug use (in addition to those identified for alcohol), required measures of correlation—or association—between drug use styles and culture characteristics. We proceeded by se-lecting, on a priori grounds, 67 culture characteristics from among the 480 available culture "classifications" in Textor (1967 y. Our selection emphasized variables relating to environment, social complexity, child-rearing methods, and cultural themes. Each of these variables was tested against selected aspects (styles) of drug use for the 247 nonliter-ate societies. The statistic employed for these operations was the Yates correction of Chi Square (two-tailed). By testing with this "shotgun" computer approach (each variable against each drug-use style for all cultures), one would ordinarily expect 5 per cent of all tests to prove significant (when alpha = .05) by chance. The limiting factor here was that the majority of tests run were not completed because of insuffi-cient data; out of more than 6,000 tests run, an estimated two thirds had multiple-cell entries in the 0 to 5 range; most others had but small numbers in each cell, so, as a result, the likelihood of achieving signifi-cant results was greatly diminished. We face, therefore, the loss of statistical power because of a paucity of original data, as well as an uncertain proportion of our significant findings being simply chance phenomena. For these reasons, beyond the demonstration of trends and general principles, our study is intended as a device for deriving hy-potheses and generating theories, not as a test of theory or of particular relationships.

In the second portion of the study, the analysis of drug-abuse data and nation-state characteristics, our selection of twenty-one polity characteristics was also made on a priori grounds, the variables being selected from the fifty-seven polity characteristics in Banks and Textor (1963)'. Information on nation-state drug abuse was obtained from UN documents (1963) for 102 reporting nations. Drug-abuse ratings (a rating of / for one or more addicts per 1,000 population, 2 for one addict per 1,000 to 5,000 inhabitants, and 3 for less than one addict per 5,000 inhabitants) were treated in 2 X 3 contingency tables, and the statistic employed for tests of association (two-tailed) was the Wil-coxin two-sample test. It is important to note that the UN drug-abuse data exclude alcohol and are not derived from what would be con-sidered adequate sources or research. Were alcohol included one would anticipate a quite diverse set of findings from those obtained.

In advance of presentation of tabular data, we again call at-tention to the paucity of observations on drug use in nonliterate soci-eties. Lack of attention by ethnographers, travelers, and other observ-ers to drug behavior is coupled with the already-noted unreliability among them where there has been observer interest. In consequence, there is no drug for which adequate descriptions exist for the ma-jority of societies in our sample. Furthermore, the culture character-istics (Textor's classifications) are often absent, so that, for some of our cultures, few if any descriptors are available (the Aleut, for example Y. These lacks constitute a severe deficiency for investigators seeking to identify determinants or correlates of drug use on a cross-cultural basis. This unreliability of observation calls attention to inadequacies in eth-nographic methods--a matter we (Blum and Blum, 1964 Y discuss more fully elsewhere.

FINDINGS

Descriptions of styles of use. We begin by presenting the data showing the distribution of aspects of drug use for the several drugs of interest among the cultures in our sample. The tables reflect simple counts based on descriptions by observers as transcribed by our raters into categories of style of use.

Drug introduction: initial source. Drugs may be introduced into a culture from outsiders, as through commerce or war, or they may grow indigenously. Sometimes a native plant may be exploited only after its properties have been taught by outsiders and sometimes a society may be introduced to a substance from both indigenous and external sources. According to Table 3, there is no communality across drug classes. For most societies where there are data, alcohol, some hallucinogens, and coca-cocaine are indigenous, whereas tobacco, some hallucinogens, most stimulants, cannabis, and opium are not native but have been brought in by outsiders. It is unusual for a drug to be of mi.xed (indigenous and outsidej origin. Observations are insufficient in number and are in conflict.

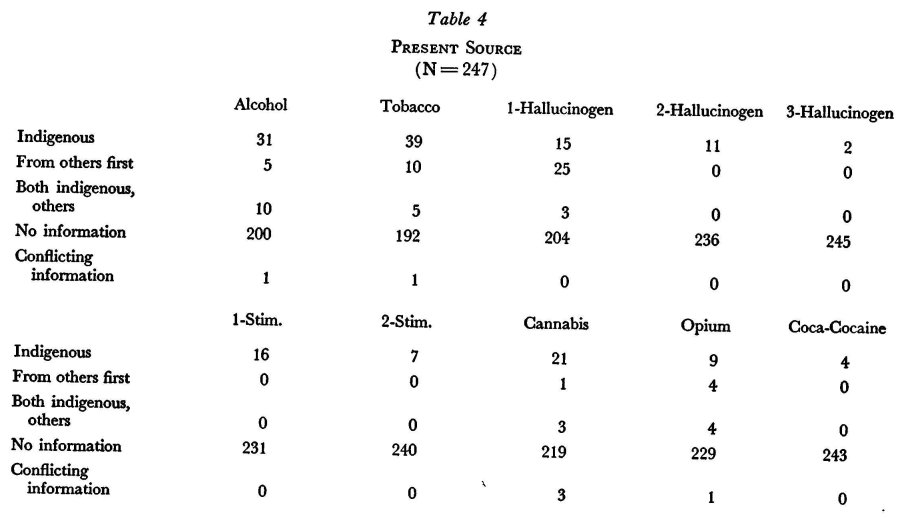

Present source. Table 4 presents data on the present sources of drugs in use, whether indigenous or outside. For all drugs, except some hallucinogens, the most frequent pattern is that the primary drug sources are indigenous. Given the -greater frequency of outside origins for drugs at the time of introduction, the implication is that over time production of drugs becomes localized and reliance on outside sources is diminished. As with other descriptions, data are available only for a few of the societies observed.

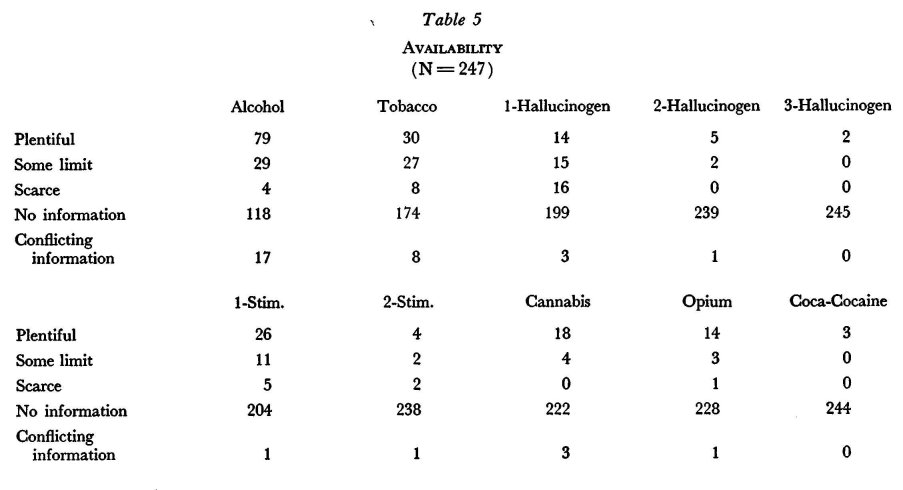

Availability. The most common case, as seen in Table 5, is for drugs to be plentiful. That holds for alcohol, many hallucinogens, stimulants, cannabis, opium, and coca-cocaine. Scarcity is an unusual circumstance, but occurs most frequently with respect to some hallu-cinogens. For the majority of societies and for all drugs except alcohol, observers have generally failed to note availability.

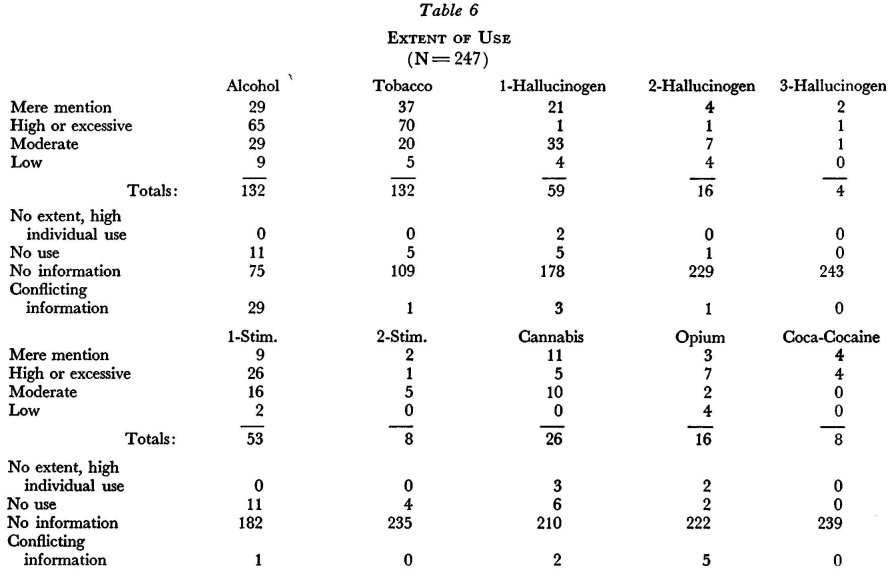

Extent of use. Table 6 summarizes observations on the extent of use of drugs among the cultures.

The tables indicate that high or excessive use characterizes be-havior regarding alcohol, tobacco, some stimulants, opium, and coca-cocaine for the majority of all nonliterate societies where observations have been made. The most common pattern of use for all hallucino-gens and some stimulants is more moderate.

It is apparent in Table 6 that for the majority of cultures the observer has failed to record whether or not the use of the drug of interest occurs. The exceptions are alcohol, where there is information in about two thirds of the cases, and tobacco, where information exists for about three fifths of the cases. The presence of conflicting reports by observers are also most often in regard to alcohol among all the drugs. From Table 6 two inferences may be drawn : one is that, with the exception of the hallucinogens, the most frequent pattern of niind-altering drug use in nonliterate societies is for high or excessive use rather than for moderate or low use and, secondly, that observers have generally been inattentive to drug use other than alcohol and tobacco. What accounts for observer inattentiveness is not known; it is possible that high or exce,ssive use of a drug—the most common observation in Table 6—is what attracts attention. If that were the case, then the large number of societies for which data are missing would be assumed to be in the low- or moderate-use categories. There is, at present, no evidence either to support or to negate such an assumption.

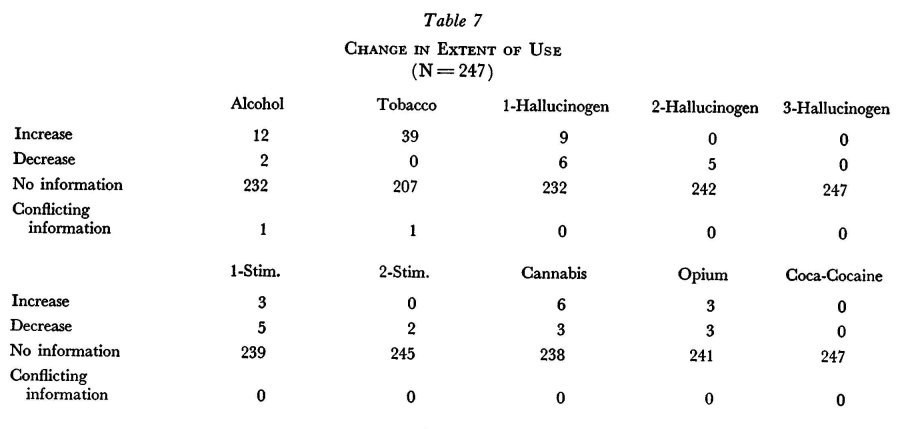

Changes in extent of use. Available data provide little infor-mation on changes in patterns or amounts of drug use for most soci-eties. We see from Table 7 that when changes are noted, the most frequent development is an increase in use.' Some stimulants are an exception. We conclude tentatively that increased drug use is the most commonly observed phenomenon.

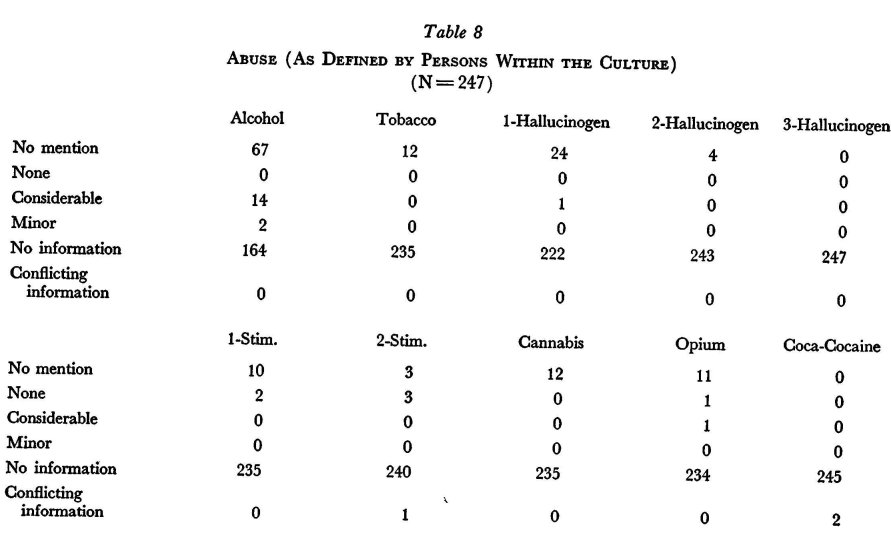

Abuse assessed by within-culture elements. "Abuse" implies undesirable behavioral or physiological outcomes as a result of individual drug use; the evaluative response of "undesirable" in turn rests upon religious, hygienic, normative, legal, or other value sources. When some persons within a culture view with alarm the drug-use habits or drug-response behavior of others (or themselves Y, a problem of drug abuse may be said to occur. When this occurs, the presence of extreme individual differences or of group heterogeneity may also be implied. Table 8 presents findings as to the presence and degree of such drug abuse as reported by within-culture members '(nativesT. When information on abuse judgments is present—and that is the unusual case—the estimation of "considerable" abuse applies to alcohol, hallucinogens, and opium. "Minor" abuse, reported on the basis of judgment by persons within the culture (nativesT, occurs infre-quently with reference to alcohol. In the case of the stimulants, and of opium in one case, people within the culture specifically deny any abuse. We draw two tentative conclusions: first, most observers have rarely attended to how persons within a society view use within that society and, second, when such- observations are made, the more com-mon within-culture response is concern—that is, disapproval is ex-pressed. This, of course, may be a biasing factor in the sense that such concern may account for an observer's recording. No stimulants are said to be perceived as abused.

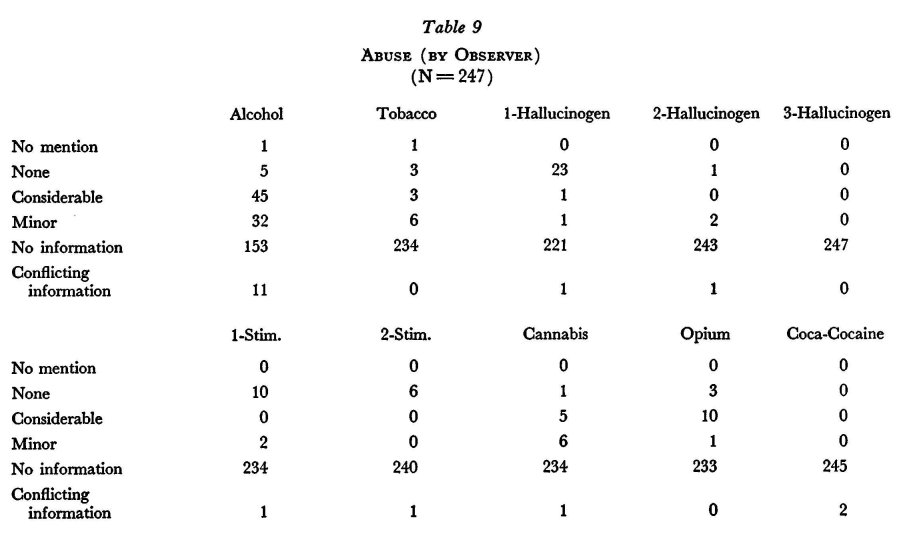

Abuse assessed by outsiders. Table 9 presents the frequency data on judgments of drug abuse as rendered by the observer whose report constitutes the description of the culture. It is apparent that observers from the outside .(nonnativesT have been quicker to report their own reactions to drug use than to report the judgments of peo-ple within a society. Thus, we have observer assessments more often set forth than indigenous ones for all the drugs. Alcohol has drawn the most frequent judgments of ab-use by observers and the most frequent conflicts among observers. Absence of abuse is noted in most cases of stimulant and hallucinogen use. For the majority of societies, the abuse of alcohol, cannabis, tobacco, and opium is described where problem use lias been considered. Our condusion from Tables 8 and 9 is that observers have been more sensitive to their own than to indigenous views of drug use within cultures. When there is alertness to abuse, both indigenous people and observers are likely to find it considerable for alcohol, opium, and occasional hallucinogens. Observers, but not indigenous people, find considerable abuse of tobacco and cannabis.

The use of stimulants is but rarely characterized as abusive by either outsiders or insiders.

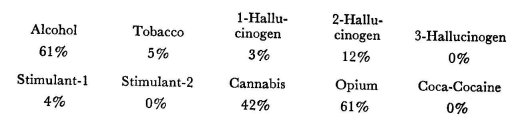

It is of interest to examine the frequency of drug abuse, as cited by observers, as a proportion of drug use per se. Taldng the drug-using cultures of Table 3 (exduding "no use," "no information," and "con-flicting information" ) and the abuse data in Table 9 (combining "minor" and "considerable," excluding "conflicting information" ), one obtains the following distribution of drug-using cultures reported to have abuse (in percentages) :

It is apparent that alcohol and opium are equally ranked as drugs abused in the majority of nonliterate cultures in which they are employed. Cannabis ranks third, with problems of abuse noted in about two fifths of the using cultures. For the other drugs, abuse is rare or subject to conflicting opinion.

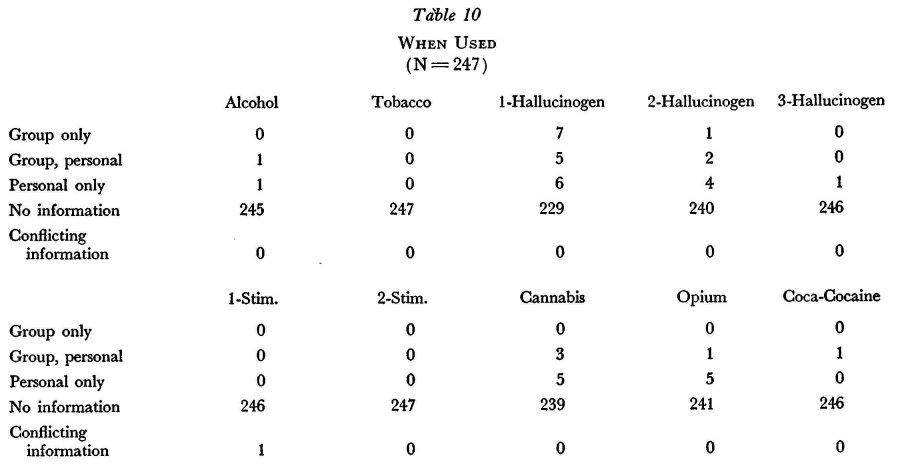

Social vs. individual use. Observer reports were reviewed to determine when drug use took place primarily as a group activity (in-tegrated use), as an individual (private) one, or as both. Table 10 presents the meager data; there is almost no clear explication of the social circumstances of use defined in these terms. For the few cultures described, one sees a predominance of individual use as opposed to group use.

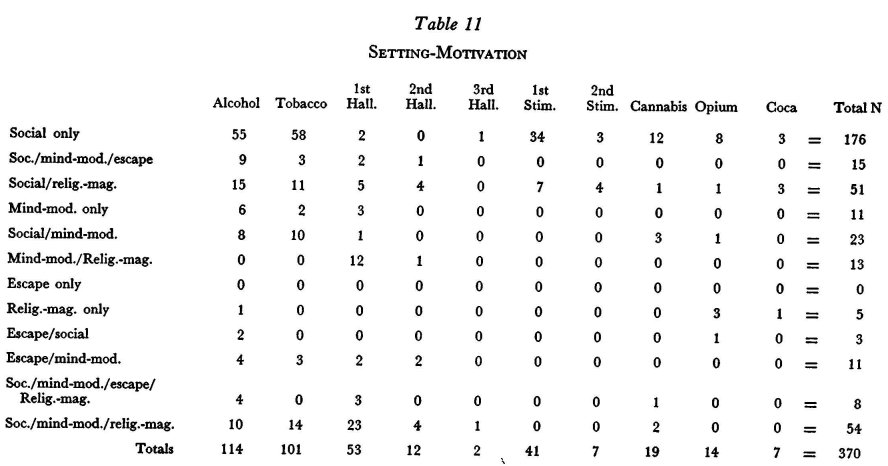

Conditions of use: setting and motivation. Another way to approach the style of use is to examine institutional settings, ritualistic content, or—translated into an inference about individual expectations —motives for use. These may also be inferred functions for drug use. Observer data were categorized in terms of these setting-motive con-ditions as follows: social (including interpersonal, other-oriented, used in eating, and festivals), mind-modifying (including private, self-ori-ented, and introspective), escape (including private, anxiety-reducing, and personal-problem dampening), religious-magical (traditional, ritu-alistic, and institutionalized, including folk medical). Table 11 shows the distribution of these styles of use and the combinations that were reported. Conditions of setting-inferred intent are fairly often described for alcohol, tobacco, and some hallucinogens, with a wide variety of conditions of use.

The data in Table 11 may be summarized in five statements as follows: (1), The most frequent setting-intent for psychoactive drug use is the social one. Ninety per cent of all descriptions for all classes of drugs include a social-use component. By "social" we imply the en-hancement or enrichment of interpersonal activities. (2) Slightly more than half (193/370) of all descriptions of setting-intent indicate that only a social component is present—that is, there are no implications of religious-magical rituals (including folk medical), of introspective private use, or of the escape use which implies psychological distress and its alleviation by drugs. (3) Multiple functions for drugs are very common—that is, psychoactive substances are frequently used under several different circumstances of setting and inferred intent. The im-plication is one of multiple social utility or psychological function for each class of drugs. (4) Drugs vary by class in the extent to which multiple functions are demonstrated. The stimulants show least variety and multiplicity of use, being limited to social and religious-magical functions. (5 ) Drugs vary by class in the predominance, cross-cultur-ally, of one function (setting-intent) vs. another. Hallucinogens, for example, are rarely simply social and most often, proportionately, in-volve mind-modifying and religiouscomponents. Opium, in turn, is proportionately most often employed for psychological-escape functions.'"

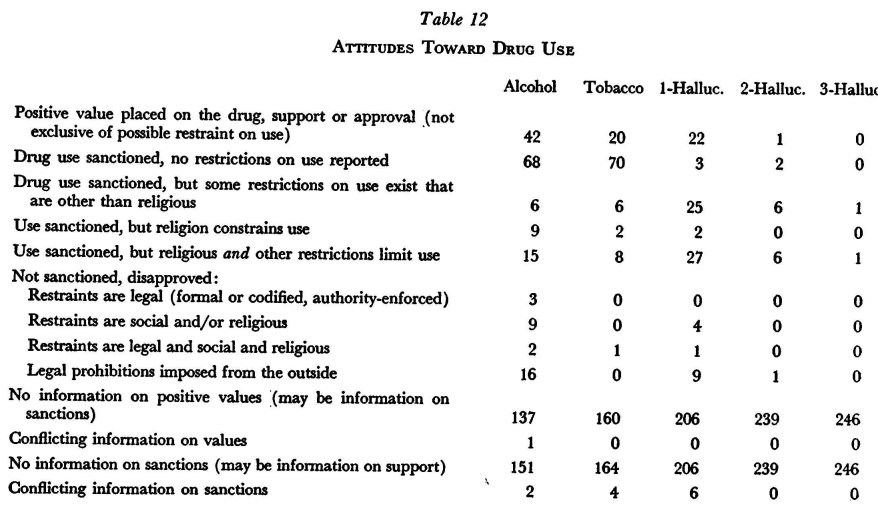

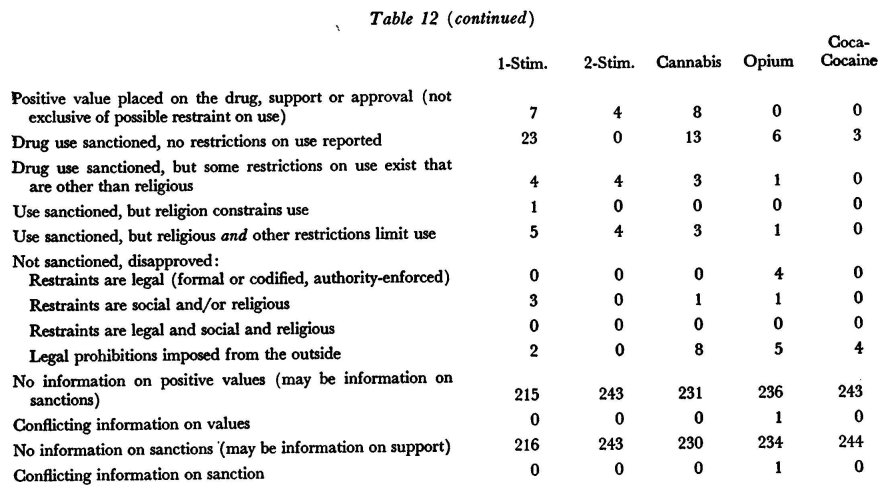

Support for and restraint on drug use. We have sought to describe general attitudes toward drug use by rating support for and restrictions against drug use. One cannot be sure that an actual con-tinuum exists from support to opposition, since within a culture these two views can exist side by side, whether in opposing subgroups or within persons whose judgment depends upon the circumstances of use. Rather than assume a continuum, we initially handled support and restraint as independent subscales—that is, positive value was rated independent of sanction, and kinds of restraints independent of both. Only after these independent ratings were complete was it apparent that such discrete analysis was unnecessary, sometimes because of lack of data, or perhaps because of a genuine continuum odsting in nature, or because observers treated disapproval-approval as a continuum creat-ing a spectrum in their observations. Table 12 presents the information on attitudinal supports and sanctions.

Inspection of the table suggests that positive values for drug use with or without restrictions on use (lack of restrictions, of course, may reflect indifference rather than approval) are the predominant patterns for all of the drugs. Approval of use combined with restric-tions occurs most often in the case of the hallucinogens. Outright (in-ternal) opposition to use occurs proportionately more often in the case of opium. Legal controls imposed on tribal societies by ruling nation-states are found proportionately more often for coca-cocaine, opium, and cannabis, in that order.

If one considers the information on positive values alone—that is, on cultures approving rather than being indifferent to, or re-strictive of, or opposed to use—one finds that the proportion of so-deties with positive values is greatest for tobacco and cannabis and least for opium and some hallucinogens.

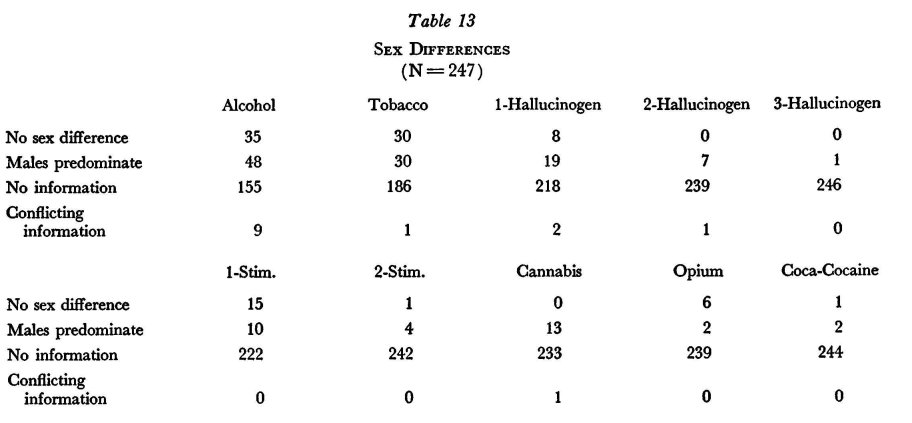

Sex differences among users. Table 13 presents data on sex differences among drug users. There is no category for "females pre-dominate" since no observation recorded that state of affairs for any drug culture. As usual, there are the most information and the most conflict among observers in regard to alcohol. One sees that in the ma-jority of cultures it is males who predominate in the use of alcohol, hallucinogens, cannabis, and coca-cocaine. Equality of the sexes in drug use occurs most often among cultures for opium, stimulants, and tobacco.

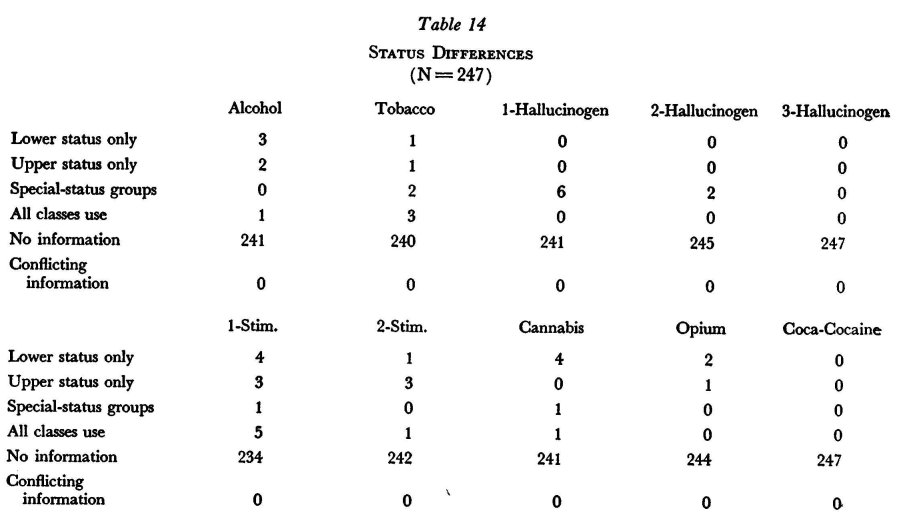

Status differences. Table 14 shows the distribution of drug-use behavior differences as a function of status ranking (such as class and caste).. Few observers have recorded this. When reports are avail-able, lower-status use is most prevalent for alcohol, cannabis, and opium, while use by special-status groups (shamans, for example) is most prevalent, proportionately, in the case of hallucinogens. Both high- and low-status use is attributed to some stimulants. The small number of entries leads us to stress the danger of attaching importance to the proportions shown here.

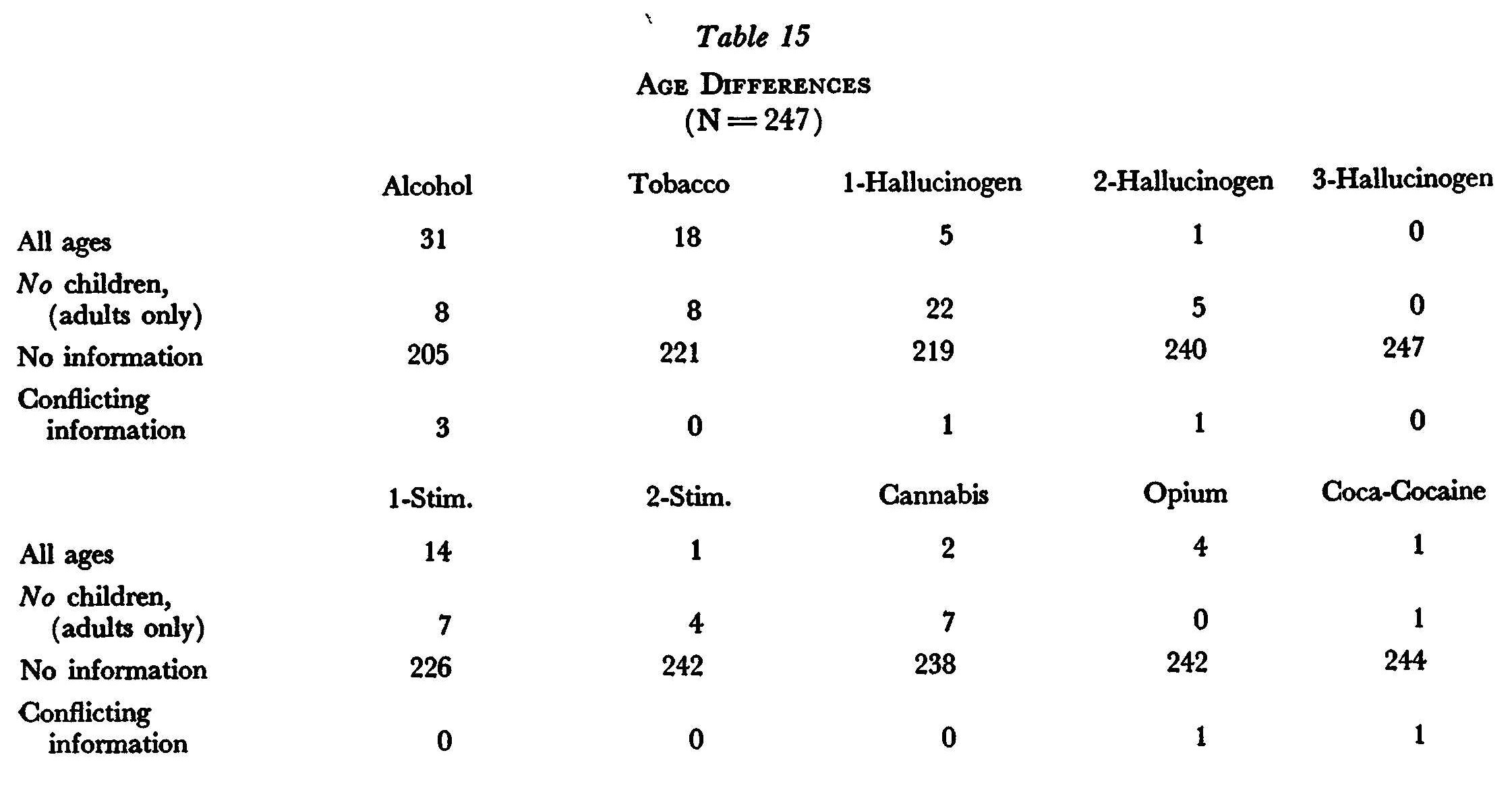

Age differences. Given the limited observations, our cate-gories are crude, contrasting cultures where children and adults may use a drug to those where children (prepubertyY are not allowed to use the drug. Table 15 shows that all-age use occurs more often for alcohol, tobacco, stimulants, and opium (including, of course, folk medical useT, whereas children are prohibited, in most of the cultures for which data are available, the use of hallucinogens and cannabis.

Resistance to use. Of special interest are those cases in which a nonliterate society is described as "resisting" use of one drug while, perhaps, at the same time heavily using or even abusing another. "Re-sistance" implies either the availability of the drug as an indigenous material or its availability to other groups geographically near by or with whom trading relations exist for other commodities. (On the other hand, from some of the reports one infers that what has been termed "reluctance to use" may simply be a matter of scarce supply. y

Cultures with evidence of high availability and little or no use are the Navajo, Papago, and Tarahumara for datura, the Pawnee for alco-hol, and the Amhara for tobacco. Cultures cited for inconsistent pat-terns—high use of one drug and resistance to another—are the Rundi with high use of alcohol and tobacco but resistance to cannabis; the Rwala, who use alcohol but resist tobacco; the Gond, using alcohol heavily but resisting opium and cannabis (see Carstairs [1954] for a related study) ; the Khasi, using alcohol heavily but resisting opium; the Yurok, Murdurucu, and Caingaing, using tobacco heavily but_ very little alcohol; the Tewa, using tobacco heavily but avoiding alcohol and hallucinogens; and the Tarahumara and Papago, using alcohol and tobacco heavily but resisting datura.

Drug use and other culture characteristics. In this section we list the significant (alpha = .05) and borderline (alpha = .10)' associations between drug-use styles and culture characteristics that emerge from our analysis. The ordering of the data is by groups of related characteristics (such as child rearing, and environmenq and within groups from characteristics most often associated with drug behavior to those least often associated with it.

1. Child Rearing and Childhood Experience

When pressure toward developing obedient behavior in the child is high, then:

ALCOHOL : Use rather than no use occurs, P < .05.

TOBACCO : Moderate rather than high or excessive use occurs, P < .10.

TOBACCO : Moderate or no use occurs rather than high or ex-cessive use, P < .05.

HALLUCINOGEN : Use by adults rather than by all ages, P < .05.

STIMULANT: Moderate rather than high or excessive use occurs,P < .10.

STIMULANT: Male use predominates rather than use by both sexes, P < .10.

STIMULANT: Use by adults only rather than use by all ages,P < .10.

When early oral satisfaction is high, then:

ALCOHOL: Use is by both sexes rather than predominantly by males, P < .05.

TOBACCO: High or excessive use rather than moderate or no use occurs, P < .10.

STIMULANT: High or excessive use rather than moderate or no use occurs, P < .10.

STIMULANT: High or excessive use rather than moderate occurs, P < .05.

When positive pressure toward developing responsible behavior in the child is high, then:

ALCOHOL: Drug is plentiful rather than limited or scarce, P < .05.

TOBACCO: Moderate or no use rather than high or excessive use occurs, P < .10.

TOBACCO: Moderate use rather than high or excessive use occurs, P < .05.

TOBACCO: Drug is limited or scarce rather than plentiful,P < .10.

When pressure toward developing self-reliant behavior in the child is high, then:

ALcoHoL: Male use is predominant rather than by both sexes, P < .10.

STIMULANT: Use is by both sexes rather than by males predomi-nantly, P < .10.

STIMULANT: Use is by all ages rather than by adults only, P < .10.

When indulgence of the child is high, then:

ALCOHOL: Drug is limited or scarce rather than plentiful, P < .05.

ALCOHOL : Use is by adults only rather than by all ages, P < .10.

When child's inferred anxiety over nonperformance of responsible be-havior is. high, then:

TOBACCO : Moderate use rather than high or excessive use occurs, P < .05.

TOBACCO: Moderate or no use rather than high or excessive use occurs, P < .10.

When pain inflicted on the infant by the nurturant agent is high, then:

TOBACCO : Use is by both sexes rather than predominant male use, P < .10.

2. Fatnily and Kinship, induding:

When the community is kin-homogeneous, then:

TOBACCO: Moderate rather than high or excessive use occurs, P < .05.

TOBACCO: Moderate or no use occurs rather than high or ex-cessive use, P < .05.

TOBACCO : Drug is limited or scarce rather than plentiful, P < .05.

STIMUIANT : Drug is limited or scarce rather than plentiful, P < .05.

STIMULANT: Drug use is by adults only rather than by all ages, P < .10.

OPIUM : No use rather than use occurs, P < .10.

OPIUM : Culture disapproves rather than approves of use, P < .05.

When the community is commonly exogamous rather than nonex-ogamous, then:

ALCOHOL : Moderate or no use occurs rather than high or ex-cessive use, P < .05.

ALCOHOL: No use rather than use occurs, P < .10.

ALCOHOL : Moderate use rather than high or excessive use occurs, P < .10.

STIMULANT: Drug is limited or scarce rather than plentiful, P < .10.

STIMULANT : Male use is predominant rather than by both sexes, P < .10.

When kin group is exclusively patrilineal, then:

ALCOHOL: Use is by all ages rather than by adults only, P < .10.

STIMULANT: Drug is limited or scarce rather than plentiful, P < .05.

OPIUM: High or excessive use rather than moderate use occurs, P < .10.

When the community is a clan community, community-structured, segmented on a clan basis, then:

ALCOHOL: Moderate or no use occurs rather than high or ex-cessive use, P < .10.

TOBACCO: Use is by both sexes rather than by males pre-dominantly, P < .10.

When family is of an extended type rather than an independent type, then:

ALCOHOL: Use rather than no use occurs, P < .05.

OPIUM : Moderate or no use rattier than high or excessive use occurs, P < .10.

When cousin terminology is of the Eskimo or Hawaiian type, then:

ALCOHOL: No use rather than use occurs, P < .10.

When kin group is patrilineal or double descent rather than matri-lineal, then:

STIMULANT: Drug is limited or scarce rather than plentiful, P < .05.

When wives are obtained by relatively difficult means, then:

STIMULANT : Drug is limited or scarce rather than plentiful, P < .05.

When commonly polygamous co-wives dwell together rather than separately, then:

CANNABIS : Culture disapproves rather than approves use, P < .05.

3. Environment and Food-Production Settlement Pattern When cereals are produced other than root foods, then:

ALCOHOL : Use rather than no use ocurs, P < .05.

ALCOHOL : High or excessive use rather than moderate or no use occurs, P < .05.

HALLUCINOGEN : Drug is limited or scarce rather than plentiful, P < .05.

STIMULANT: Use rather than no use occurs, P < .10.

STIMULANT: Excessive or high use occurs rather than moderate or no use, P < .05.

When the natural environment is very harsh—desert, desert grasses, tundra, steppe—then:

ALCOHOL: Drug is limited or scarce rather than plentiful, P < .05.

TOBACCO : No use rather than use occurs, P < .05.

HALLUCINOGEN: Personal rather than group use occurs, P < .05.

STIMULANT: Moderate use rather than high or excessive use occurs, P < .10.

When food production is by intensive rather than simple agriculture, then:

TOBACCO : Moderate or no use occurs rather than high or ex-cessive use, P < .10.

STIMULANT: High or excessive use rather than moderate or no use occurs, P < .05.

When food supply is secure and food shortages are rare or occasional, then:

TOBACCO : High or excessive use rather than moderate use occurs, P < .05.

TOBACCO : High or excessive use rather than moderate or no use occurs, P < .05.

When natural environment is very harsh—subtropical bush, temper-ate grassland—then:

TOBACCO : No use rather than use occurs, P < .10.

HALLUCINOGEN : Personal use rather than group use occurs, P < .10.

When settlements are fixed, then:

STIMULANT: Drug is plentiful rather than limited or scarce, P < .10.

STIMULANT : Extent of drug use does not increase, P < .10.

4. Social, Political, and Economic Organization

When class stratification based on wealth and/or occupational status Ls present, or based on occupation alone (two Textor descriptions combined), then:

HALLUCINOGEN : Extent of drug use is not increased, P < .05 (oc-cupation only).

STIMULANT : High or excessive use rather than moderate use occurs, P < .05 (wealth or occupation), P < .10 (occupation only) .

STIMULANT: High or excessive use occurs rather than moderate or no use, P < .05 (wealth or occupation), P < .10 (occupation only).

STIMULANT : Culture disapproves rather than approves use, P < .10 (wealth and/or occupation).

When political integration is the large state, the little state, or the minimal state, then:

ALCOHOL: Use is by adults only rather than by all ages, P <.10.

TOBACCO : Moderate or no use occurs rather than high or ex-cessive use, P < .10.

TOBACCO : Use is by adults only rather than by all ages, P < .10.

When there is presence of hierarchy of jurisdiction, then:

ALCOHOL : Moderate use occurs rather than high or excessive use, P < .10.

HALLLUCINOGEN : Group use occurs rather than personal use, P <. 10.

CANNABIS : Moderate or no use occurs rather than high or ex-cessive use, P < .10.

When the society works in metal, then:

ALCOHOL : Use rather than no use occurs, P < .05.

STIMULANT : Use rather than no use occurs, P < .10.

When headmen are hereditary, then:

ALcoHoL: Moderate use rather than high or excessive -use occurs, P < .10.

CANNABIS : High or excessive use rather than moderate use occurs, P < .10.

When individual rights in real property and rules for inheritance are present, then:

TOBACCO: Use rather than no use occurs, P < .10.

TOBACCO : Culture disapproves rather than approves use, P < .10.

When class stratification is present, then:

HALLUCINOGEN : Drug use does not increase in extent, P < .05.

5. Interpersonal Themes; World View

When games are limited to games of skill only, then:

ALCOHOL : No use rather than use occurs, P < .05.

STIMULANT : Drug is plentiful rather than limited or scarce, P < .10.

STmuLANT: Drug use is by both sexes rather than male use pre-dominantly, P < .10.

STIMULANT : Use is by all ages rather than by adults only, P < .10.

When dreams are used to control supernatural powers, then:

ALCOHOL : High or excessive use occurs rather than moderate use, P < .10.

TOBACCO: Drug is limited or scarce rather than plentiful, P < .05.

STIMULANT : High or excessive use rather than moderate use occurs, P < .10.

STIMULANT : High or excessive use rather than moderate or no use occurs, P < .10.

When games, if present, include games of strategy, then:

ALCOHOL: Use rather than no use occurs, P < .10.

ALCOHOL : Drug is plentiful rather than limited or scarce, P < .05.

STIMULANT : Drug is limited or scarce rather than plentiful, P < .05.

When military glory is strongly emphasized (or moderately), then:

ALCOHOL : Male use is predominant rather than use by both sexes, P < .05.

CANNABIS : Culture approves rather than disapproves use, P < .10.

When bellicosity is extreme, then:

ALCOHOL : Male use predominates rather than use by both sexes, P < .10.

HALLUCINOGEN : Culture approves rather than disapproves of use, P < .10.

When games, if present, include games of chance, then:

ALCOHOL : Use rather than no use occurs, P < .10.

ALCOHOL : Culture approves rather than disapproves use, P < .10.

When composite narcissism is high, then:

ALCOHOL : Male use predominates rather than use by both sexes, P < .05.

ALCOHOL : Use rather than no use occurs, P < .10.

Forty out of the sixty-seven culture characteristics are shown to have significant or borderline relationships to styles of use of one or several mind-altering drugs. One sees that in all cases where three or more associations occur between a culture characteristic and drug-use styles, these apply to two or more different drugs. One also sees that each type of drug is associated with cross-cultural characteristics, ex-cept for coca-cocaine. We tentatively conclude that culture character-istics will be found as correlates of the use of any class of mind-altering drugs.

In terms of the number of significant or borderline associations between drug-use styles and culture characteristics, these correspond, with important exceptions, to the number of observations on the Ilse of the drug—that is, to the adequacy of the cross-cultural data. Alcohol, on which the largest number of observations are available, yields thirty-two such associations. At the opposite extreme, coca-cocaine yields none; observations on its use were available for only eight societies—obviously an unfruitful N for contingency tests. The other drugs infre-quently reported on (or infrequently employed, in fact) by observers are opium and cannabis; for each of these only four associations are significant—setting the alpha level at .10 for convenience of the present discussion. A reversal of order occurs in the middle cases; twenty-four associations significant beyond .10 occur, yet for the stimulants—ob-servations of which exist for seventy-eight fewer cultures than tobacco —thirty-two associations (alpha = .10) are noted. The hallucinogens, on the other hand, observed in slightly more societies than stimulants, yield only eight relationships significant when alpha is set at .10. Some of the,se departures from a regular relationship between drug-data in-adequacy and findings probably result from variations which occur in available data on the culture characteristics themselves (see Textor, 1967 )'. Some probably reflect real differences in the features of cultures associated with the use of one drug versus another. One obvious con-dusion is that the more adequate the descriptive data, the more likeli-hood there is of uncovering relationships between drug use and culture characteristics. The possibility of a linear relationship is not excluded; if that were the case, then one would expect careful observation to reveal a very considerable array of cross-cultural characteristics which would be predictive of drug-use styles. The alternative would hold also: knowledge of drug behavior would allow prediction of certain other culture characteristics.

We call attention to consistencies in the foregoing relationships which are based on the categorization of the discrete culture character-izations into sets of related variables.

1. Child rearing is related to the levels of use of several drugs and to their differential use within a culture (by age, sex, status). For example, trends toward moderation in use of alcohol, tobacco, and stimulants, as well as the unrestricted use of hallucinogens, stimulants, and tobacco, occur where there are childhood pressures toward obedi-ence, where pressures toward responsible child behavior exist, and where amdety over that responsibility exists.' Childhood self-reliance, child indulgence, narcissism, and pain infliction on the child all show relationships to what groups may use drugs.

2. Kin and family relationships appear related to levels of use of several drugs; kin-homogeneous communities show moderate to-bacco use, little or disapproved opium use, and have a limited supply of stimulants; exogamous communities are associated with from no-to-moderate alcohol use, scarcity of stimulants, and so on.

3. Environment and food production are related to levels of use of several drugs. Environmental harshness implies limited alcohol supply, absence of tobacco use, lower stimulant use, and personal rather than group hallucinogen use. Cereal rather than root production im-plies high alcohol and stimulant use, but low availability of hallucino-gens; a secure food supply implies high tobacco use; intensive rather than simple agriculture implies greater use of tobacco and stimulants; a food-production society per se implies plentiful alcohol and, gener-ally, when food supplies are plentiful, drug abuse is more common. Such an association, although intriguing, also demonstrates the need for caution in interpreting and generalizing. At the nation-state level, it appears that the poor rather than the wealthy are more in danger of drug abuse (such as alcoholism and opiate dependency), althbugh use without abuse characterizes wealthier groups. Perhaps at the pre-industrial level, plant-production efforts are not devoted to nonnutritive substances until some level of abundance is achieved.

4. The structure of social and economic organization is also a drug-related feature. For example, political integration at the state level finds alcohol and tobacco use limited to adults; a hierarchy of jurisdiction implies moderate alcohol use, group rather than personal hallucinogen use, and low rather than high cannabis use. Also, wealth-and/or occupation-based class stratification implies high stimulant use and simultaneous disapproval of such use, no increase in hallucinogen use, and drug abuse as defined by outside observers. Hereditary chief-tainships occur with moderate rather than high alcohol use but, con-versely, with high rather than moderate cannabis use. Economic styles, other than agricultural, are also drug-behavior correlates. For example, the use of alcohol and stimulants is associated with metal-worldng so-cieties; individual property rights are associated with tobacco use and disapproval of that use.

5. Interpersonal themes (to construct a loose category of val-ued behavior ) appear related to the differential use of one drug versus another. For example, games of skill ( but no other games) imply use of stimulants but nonuse of alcohol; military glory occurs in connection with cannabis approval; and bellicosity with hallucinogen approval. Magical-religious orientation is related to the level of use of several drugs, for when dreams control supernatural powers, alcohol and stim-ulant use is high rather than moderate.

On the basis of these findings, we tentatively conclude that gen-eral relationships are likely to hold in nonliterate societies for styles of use of several drugs and for differential use of those drugs and speci-fied culture variables. It appears that child-rearing practices are strongly implicated, as are kinship patterns and family practices, the nature of the natural environment and of agricultural practices, cer-tain cultural themes or interests, magical-religious techniques, social structure, and economic styles.

The styles of drug use which are most often associated with culture characteristics are those of levels (amount) of use and the characteristics of persons using the drug (age, sex, status). We fmd no associations for most of the styles of use for which both original descriptive data and relationships were sought—for example, motiva-tions, sanctions, attitudes, circumstances of use, sources, changes, and manner of introduction. Some relationships are demonstrated in con-nection with drug availability and abuse. We attribute this to the paucity of original observations, to the small frequency of observations in any one category in the more highly refined category schemes (for example, setting-motivation--see Table 11), and possibly to real dif-ferences, as well as to the likelihood that manner of introduction and present source of drug are less integral to cultural styles than is drug using per se.

We are limited to the conclusion that the extent of use of nearly all classes of xnind-altering drugs, approval and disapproval of the use of at least some of these drugs, availability and selection of certain drugs over others, and the kinds of persons within a society who use particular drugs are all behaviors integrated with other features of (nonliterate) culture characteristics which are identifiable and appear in common on a cross-cultural basis. There is also some evidence sug-gesting that changes in extent of use (of hallucinogens) and that con-ditions of use—specifically as a group contrasted to individual phe-nomena—are related to particular characteristics of societies. These statements will come as no surprise to those familiar with alcohol stud-ies, for such general relationships were demonstrated in earlier cross-cultural alcohol research.

Relationships among styles of drug use. In this section are reported the significant (alpha = .05)' and borderline (alpha = .10) associations (all two-tailed tests) among styles of drug use. An earlier model for interrelated styles is found in the 1965 study by Child et al. (for example, their study of the sex of drinkers in relationship to the presence of aboriginal drinking and to the presence or absence of in-tegrated drinking within cultures)'.

ALCOHOL: The extent of use is high rather than low or mod-erate when observers indicate abuse is high rather than minimum, P < .05.

The drug is indigenous in origin when social reasons for its use are present, P < .05.

TOBACCO : Extent of use is low or moderate rather than high when magical-religious reasons for its use are pres-ent, P < .05.

The drug is indigenous in origin when religious-magical reasons for its use are present, P < .05.

STIMULANTS : The extent of use is high rather than low or mod-erate when the drug is plentiful rather than less plentiful, P < .05.

The extent of use is low or moderate rather than high when religious-magical reasons for its use are present, P < .05.3

CANNABIS : The extent of use is high, moderate, or low rather than no use when it is plentiful rather than less plentiful, P < .05.

The drug is indigenous in origin when religious-magical reasons for its use are present, P < .10.

The foregoing statements suggest that there are some interre-lationships among styles of drug use for several classes of mind-altering drugs. The relationships between extent of use and availability are hardly remarkable; those between extent of use and religious-magical conditions of use—one of the conditions of "integrated" use—are of theoretical interest. What is most noteworthy is the paucity of signifi-cant interrelationships.

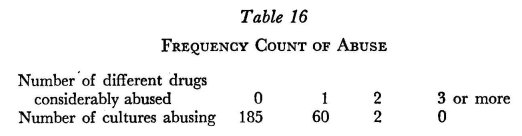

Drug abuse in nonliterate cultures. In describing the extent of drug use, we have combined observer ratings of "high" or "exces-sive" use into one category (Table 1)', which limits itself to the amount of the drug consumed. Judged abuse of drugs may or may not be re-lated to amounts consumed, as Child et al. have shown, and we have used a separate rating scheme to report abuse, Table 8 showing the in-frequency with which members of a culture describe (or are asked about!)' it and Table 9 for abuse (or concern) described by the out-side observer. We have seen that the extent of use of particular drugs —and to a lesser degree approval-disapproval (Table 12 Y—are asso-ciated with other features of societies. In this section we examine drug abuse per se, not limited in our analysis to a particular drug. Table 16, below, is a frequency count of the number of cultures in our sam-ple abusing one or more drugs considerably, that abuse resting on an outside observer's judgment.

Reports of single- rather than multiple-drug abuse are the most common. Nonobservation on abuse predominates. Three quarters of the considerable abuse is for alcohol, again suggesting the inadequacy of data on other drugs. One asks whether any insights are gained by comparing cultures considerably abusing any drug—judged by outsiders--with those described as not abusing any (a contaminated procedure since abuse not noted does not assure its absence or abusing them to a minor extent only. Below are listed those associations significant at the .05 and the borderline .10 levels.

Drug abuse occurs when the natural environment is very harsh, P < .05.

Drug abuse occurs when the food supply is plentiful, P < .05.

Drug abuse occurs when class stratification based on wealth and/or occupational status alone are present (a combined variable), P < .10.

Drug abuse occurs when military glory is strongly or moderately emphasized, P < .05.

Drug abuse occurs when bellicosity is extreme, P < .05.

There is only one association between drug abuse as described by persons within a culture and another culture characteristic; one fmcLs, in remarkable contradiction to what outside observers report -(see above )1, that

Own-culture-perceived drug abuse does not occur when the food supply is secure and food shortages are rare or occasional, P < .10.

Drug abuse and the characteristics of nation-states. Earlier, we examined relationships between the variety of drug-use styles and the characteristics of nonliterate cultures. We now extend that analysis to nation-states, limiting the style of use to one feature--namely, drug abuse (excluding alcohoq as reported by governmental agencies in that nation. It will clearly be seen that the socioeconomic characteristics of the nation-states are not independent. The statistics applied to the ordered two-by-three contingency tables were the Wilcoxin- two-sample test. All tests were two-tailed. Relationships are as follows:

Drug abuse is associated with population-growth rates of over 2 per cent per year, z =-- 2.05, P < .05.

Drug abuse is associated with an agricultural population of 34 per cent or more, z 2.99, P < .05.

Drug abuse is associated with gross national product of less than $300 per person per year, z — 3.63, P < .05.

Drug abuse is associated with a gross national product of less than $600 per person per year, z — 3.59, P < .05.

Drug abuse is associated with low economic-development status (little prospect of attaining a self-sustained economic growth by the mid-1970's) , z — 3.17, P < .05.

Drug abuse is associated with low rates of literacy "(50 per cent or less), z =-- — 2.54, P < .05.

Drug abuse is associated with low newspaper circulation (less than 100 per 1,000 population), z = — 3.72, P < .05.

Drug abuse is associated with other than Christian religious affilia-tion by the majority of the population, z — 4.33, P < .05.

Drug abuse is associated with the absence of linguistic homogeneity among the population, z = — 3.44, P < .05.

Drug abuse is associated with absent or only partial Westernization, z --= — 3.12, P < .05.

Drug abuse is associated with government instability, z — 2.34,P < .05.

Drug abuse is associated with limited or absent interest articulation by institutional groups (such as clergy, legislative blocs, and profes-sional groups), z 2.58, P G.05.

Drug abuse is associated with limited or absent interest articulation by nonassociational groups (such as kin, ethnic, religious, regional, status, and class), z = 4.02, P < .05.

Drug abuse is associated with infrequent interest articulation by anomic groups (as in demonstrations and riots), z 3.84, P < .05. Drug abuse is associated with the absence of elitist political leader-ship (leadership is not confined to particular racial, social, or ideo-logical

The following relationships were not found to be associated (when alpha = .05)::

Drug abuse and Muslim religious majorities in the population, z = 1.09.

Drug abuse and religious homogeneity, z — 1.79.

Drug abuse and Westernization through colonial status, z — 1.55.

Drug abuse and former British colonial rulership vs. colonial ruler-ship by others, z = 1.71.

Drug abuse and the freedom of group (political) opposition, z = .84.

Drug abuse and the extent of political enculturation (extremity and extent of opposition, factionalism, disenfranchisement), z — 1.20.

We conclude from the foregoing that drug abuse, defined by national self-reporting, is associated with a variety of socioeconomic characteristics; extensive own-nation-perceived drug abuse seems essentially to be a problem of the underdeveloped countries.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

Observations on drug use in 247 nonliterate societies were analyzed for descriptions of drug behavior. Various styles of drug us'e were then tested for relationships to 67 culture characteristics. In addition, "narcotic" drug-abuse data from 102 nations were used in a test for relationships to 21 nation-state socioeconomic characteristics.

The following major findings emerge.

Observers of nonliterate societies have tended not to report on drug-use behavior in any detail; furthermore, observers are often in conflict with one another, suggesting inadequate ethnographic methodology. A strong need exists, then, for interested ethnographers in drug use and in training them to perform quantifiable and reliable observations.

When data are available on nonliterate societies, the predomi-nant use pattern which emerges is one of high use of alcohol, tobacco, opium, coca-cocaine, and some of the stimulants; hallucinogen and some stimulant use tends to be at low or moderate levels. As far as trends are concerned, increase rather than decrease in use is the pattern more often observed, with the exception of the stimulants and opium. High drug availability is common except for hallucinogens. Availabil-ity, in turn, may be a function of the observed tendency for drug pro-duction to become local, even if the original sources were not indige-nous.

Problems of abuse are rarely noted, except for alcohol. It is rarer still for observers to inquire as to whether natives themselves conceive of their group as having an abuse problem; more often, the observer renders his own judgment. Both indigenous sources and out-side observers, when their views are reported, cite considerable abuse of alcohol, cannabis, tobacco, and opium; outsiders, but not insiders, report the predominant picture for tobacco and cannabis is also abuse; neither outsiders nor insiders perceive many societies as abusing nâtural stimulants. It is important to keep in mind that abuse is seldom sub-ject to careful definition and must be conceived as an expression of disapproval or concern.

Analysis of the settings and motives surrounding drug use indi-cates that social components are the most common and that the in-ferred enhancement, enrichment, or smoothing of interpersonal activi-ties is a primary function for most classes of psychoactive drugs and is one component of action in all of them described here. It is also observed that multiple functions are common—that is, the same drug serves several functions within the same society. Drugs vary, by class, in their tendency to fulfill multiple functions and also in their predomi-nant use for particular inferred functions. Stimulants, alcohol, and tobacco, for example, are very often simply social; hallucinogens, rarely social, are much more often religious-magical or mind-altering. Proportionately, opium is most often implicated in psychological-escape functions.

Positive values accompany the use of most drugs; in most cul-tures for which data are available, alcohol, tobacco, stimulants, can-nabis, and coca-cocaine are used either with positive approval or with-out restraint. However, the number of societies disapproving and/or restraining alcohol use nearly matches those approving and not restraining it. Re,straints, coexistent with positive values, predominate in the use of hallucinogens and some stimulants; outright opposition is the majority pattern for opium. Obviously, such opposition can occur simultaneously with high rates of use, suggesting cultural heterogeneity, individual (intrapsychic) conflict over use, or that strong interests in use generate counterreactions of control.

There are various distributions according to sex, age, and status. For no drug in any society reported here does female use surpass that of males. The predominant pattern for alcohol, hallucinogens, and cannabis is for primarily male use. Both-sex use is the majority pattern for opium, stimulants, and tobacco. Low-social-status use as opposed to high-status use occurs most often with alcohol, cannabis, and opium. Special groups (such as shamans) tend to use hallucinogens; high-status groups, the stimulants. The meagerness of data requires extra caution in viewing these drug uses and status findings. The use of cul-turally extant drugs by all ages is the characteristic pattern; on the other hand, children in most societies are prohibited the use of hallu-cinogens and cannabis.

A phenomenon of special interest is the resistance to the use of one drug by a society using other drugs and having access to the re-sisted substance. Certain resisting societies are identified. Further study of this behavior would be worth while.

- In testing associations between drug behavior (and availabil-ity) and other characteristics of nonliterate societies, forty variables have been identified as possibly related to drug use. In view of the partial correspondence between the adequacy of observations and the frequency of significant findings, more intensive future work is likely to yield a considerable number of culture characteristics related to vary-ing aspects of drug behavior. At present, our findings are limited pri-marily to associations with the amount of drug use and the character-istics of users.

The major expectation that behavior in regard to several classes of mind-altering drugs is related to social variables is borne out. When any cultural characteristic is found associated (alpha = .10, two-tailed test) with three or more drug-use styles, the association is with two or more different drugs; all drugs except coca-cocaine (on which the few-est observations are available) are so related. Generally, levels of drug use ( high to low) are associated with child-rearing methods, the nature of the environment and food-production methods, kin relationships, and social structure. The choice of one drug as opposed to another appears related to social structure and to economic life styles. The par-ticular associations which emerge here are best considered as sources of hypotheses, not as demonstrated relationships. The anticipated rela-tions between other aspects of drug behavior and culture character-istics did not appear. Presumably, this is due to the insufficiency of original observations.

Certain relationships are also found between some kinds of drug behavior as, for example, availability and extent of use. These rela-tionships among drug behaviors arc few and unremarkable and sug-gest the need not only for more data but also for more explicit hy-potheses and more refined approaches.

Comparing those nonliterate societies noted by observers for considerable abuse of any drug with societies viewed as not having abuse (even though it may occur and be unreported) yields but few relationships. Both the data and the comparison method are deficient, but the comparison does suggest that abuse is associated with environ-mental harshness, class stratification based on wealth and/or occupa-tional status, military glory, and bellicosity. Since abuse as perceived by indigenous informants is limited to an association with an insecure food supply, even though observers also find abuse in association with plentiful food, it is evident that no conclusions are in order regarding the relationship between perceptions of drug abuse and the adequacy of food. These relationships certainly merit further inquiry.

The search for relationships between levels of drug abuse (ex-cluding alcohol) as reported by nations and as revealed by the socio-economic characteristics of those nations has been fruitful. Fifteen out of twenty-one variables are shown to be related; for example, abuse is least where populations are Christian, where there is political ac-tivity (articulation) by (nonassociational) interest groups, by anomic groups, and where newspaper circulation is high. Generally, the char-acteristics of nations with high self-reported rates of narcotic and 'other nonalcoholic drug abuse are those one associates with the underdevel-oped non-Western nations. Were estimates of abuse to indude alcohol and to be based on epidemiological rather than official case data, it is likely that more complex findings would emerge which would show that Christian and Western nations are not without serious drug-be-havior problems.

It is our thesis that attention to patterns of drug use within cultures and across culture is merited-those patterns to include the full range of mind altering substances. Though such an approach, greater knowledge of correlates and determinants of drug behavior-including the problem behaviors adn drug outcomes comprising abuse-will be gained. The present study suggests the complexity of drug bahavior, but it also indicates, as has the work of many others, that one sector of the road to understanding l;ies in the study of childhood rearingh and natural and social environments.

1 The dates of the observations on societies in otu. sample range from 1520 (Inca, Maya) to the present. A total of fifteen reports are prior to 1850, so we cannot say that all changes in extent are recent ones.

2 This study does not attempt to replicate that of Child et al. (1965). Comment is required on what may appear to be discrepancies between their fmdings and ours. Their study, focused on akohol, pays special regard to the correlates of drunkenness and a factor analysis of drinking behavior; it used sup-plemental reading and direct inquiries to ethnographers to establish ratings; rat-ing scales were 7 point continua, relationships were reported as correlations, and complex hypotheses linking several aspects of drinking behavior were explored. They used a sample of 139 societies, most of which were preliterate, 110 of which were known on the basis of the authors' earlier work, 57 of which were from Horton's sample.

In contrast, our study includes, but does not focus on, alcohol, did not seek to arrive at final judgments when two sources were contradictory, used fewer point-rating scales, and tested for association rather than using coefficients of correlation (although Child et al. do report significance of their correlations). We did not rate drunkenness per se or the same behavior factors used by them (for example, we combined "high" and "excessive" use and treated "abuse" as a general variable), and we did not test all of the culture characteristics tested by Child et al., nor did we test all of their drinking-behavior variables. Further and crucially, our sample contained 247 societies, 172 of which had alcohol use or nonuse specified. Even though our sample included the Child cultures, when their data on an item contradicted another source, we excluded that item from the analysis as unreliable.

We suggest that apparently discrepant findings as they exist are a func-tion of conception method and sample.

3 Here again we note how contingent our associations are upon what observers have reported--observations very likely influenced by ethnographic fashions. What, for example, if our information on those drugs we find to be associated with religion-magic exists only because observers were interested in religion and magic, and so noted drug use in that context? It would mean that drug sampling was biased, so that any correlations would reflect sampling error rather than natural relationships; possibly, then, extensive use of these same sub-stances outside of religious-magical contexts had been ignored.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|