IX A Cultural Case Study: Temperate Achilles

| Books - Society and Drugs |

Drug Abuse

Our concern here is to examine the use of alcohol in three rural Greek communities, to suggest how its use is related to other aspects of rural Greek culture and personality, and to determine the extent of a specific health problem: alcoholism. In rural Greece there are illnesses that villagers say the doctors do not recognize; alcoholism is one that no one recognizes. This social fact is fundamental to understanding matters that range from the reporting of statistics to the handling of local inebriates.

Approximately three thousand years have passed since "blameless" Achilles, the epitome of Greek manhood, ravaged the army of the Trojans. Since the days of Homeric heroes the Greeks have seen their city states disintegrate and the centers of culture, wealth, and political power vanish. Yet, despite the changes of the centuries and the intermingling of racial stocks, much has remained of the ancient Greek spirit, of the Greek temperament. Tales and customs from antique times live on. Most important for the present study, the ideal of manly excellence, arete, has persisted practically unchanged. True, the modern Greek has a new word for it: levendis. To call someone levendis is high praise. The levendis is a joy to behold for his body is beautiful, his song deep and loud; with powerful leaps he leads the dancers, all full of grace and pride. Hospitable to the stranger is the levendis and a terror to whoever opposes him. He leaves no offense unavenged; he can drink more than anyone else at a festival, yet never falter in song or step. He is blameless—and blameless also was Achilles whose body had no flaw and whose courage in battle none dared to challenge. "To the levendis" is a toast given standing, drink raised high; it can bring tears of pride to the man so honored.

That was the hero of old and that is the Greek of today—at least, that is the portrait of himself which he would paint and maintain. Should an alien force intrude to disturb the flattering image, it must be erased, or suppressed, or at least verbally denied. No wonder, then, that no alcohol problem exists in Greece. For the individual to be a drunk is to be only "half a man," an animal, and so it is understandable that no villager will portray himself in this unfavorable light. What is true for the man is true for the nation. The national philotimo, or love of honor, demands there be no shameful blemish.

Many are the reasons offered to explain the land's good fortune in being free from alcoholic problems. The skeptical observer, knowing a bit about Greek pride and attendant Greek denial, may not be fully convinced. After all, even glorious Achilles had his weaker moments. Yet, when the observer sets out to inquire for himself, he may be surprised to learn that his Greek informants did not gloss over the facts as much as he had anticipated. And so it was with us. Social beliefs are social realities and, on occasion in human affairs, there is a substrate of empirical evidence to support them. Let us now examine the evidence and then the beliefs, reaching our conclusions as best we can from limited materials.

The findings reported here are the result of years of work, during which four study trips to Greece were undertaken, the last in 1962. The methods used were those of the social and clinical psychologist; they consisted in formal interview schedules with all families and healers in the area studied; observation and rating schedules included the Dodds Hygiene Scale originally used in Syrian villages. A third method was an action technique, whereby, in cooperation with the Ministry of Health, we introduced physicians into each community and conducted Greece's first morbidity survey and observed the villagers' reactions to medical care. Finally, we employed the informal observations derived from living with the village folk.

As a consequence, we became acquainted with each family in each village; with the local medical personnel—the doctors, pharmacists, and midwives; with the nonmedical healers—the priests, nuns, magicians, practikoi, and wise women; and with the village drunks and the village tavern keepers.

Three communities were studied in this formal manner. A fourth, in which we lived, provided informal observational data. The study communities were located in Attika :1 Panorio with 126 peasant residents, ethnically homogeneous, and of Albanian-Doric stock; Dadhi with 200 people from Asia Minor who had come to mainland Greece in 1922; and the third, a community of eight families of Saracatzani shepherds, said to be descendants of ancient Greeks but today living scattered on the mountainside. None of the three communities has local authorities; they are all under the jurisdiction of the central community of Doxario, which boasts about a thousand inhabitants, and in which we lived. Our house contained a tiny coffee house-taverna and fronted a somewhat larger taverna. Thus, unobserved ourselves, we could watch the comings and goings of their habitués and study their behavior.

PATTERNS OF USE

In Doxario and the surrounding villages, it is relatively easy to distinguish those social settings in which, or occasions on which, alcoholic beverages are consumed. These are as follows:

With meals, excluding the morning meal

At the coffee house-tavema At family celebrations

During the rites of hospitality At festivals

During religious rites

During efforts to heal the sick

Meal-time use. At the noon meal, at the evening meal, and during afternoon or evening "snacks," it is common for alcohol to be consumed. It is usually taken in the form of retsina, a locally produced white wine which has been flavored with resin from the local pine trees and has an alcohol content between 12 and 14 per cent. After dinner strong, sweet wines may be served, often diluted with water.

Coffee house-taverna. When they have leisure time, the men gather at the coffee house. While there they may read the newspapers, talk, play tavli (a game resembling checkers), sip coffee and water, or consume alcohol. The most common alcoholic beverage ordered in the coffee house is ouzo, an anise-flavored, distilled grape product containing about 46 per cent alcohol. It is usually taken mixed with a full glass of water. Alcohol may be consumed any time during the day while at the coffee house, but, more frequently, it is ordered during a show of hospitality or friendship or in the evening. It is our impression that evening consumption is increased on those occasions when musicians are present or when a record player is playing.

Celebrations. We define "celebrations" here as festivities limited to family events or gatherings of family and friends. Celebrations occur when a child is born, when there is a baptism, a wedding, or a name day ( equivalent to the American birthday celebration except that it occurs on the day sacred to the saint whose name the celebrant bears), when a house, an animal, or an enterprise is blessed by the priest, or on "good days" when some happy event or good fortune befalls someone in the family. If the celebration involves all family members, it will take place at home. White wine, retsina, will be served. In addition, depending upon income, social standing, individual preference, and the importance of the occasion, there may be ouzo, liqueur (most often rose-flavored such as when ouzo is flavored with rose water, but fruit liqueur may also be served), brandy ( called "cognac"), or, though rarely, tsipouro or raki.

A celebration may also occur at the coffee house-taverna, in which case it will be limited to male friends. To mark a special occasion, beer may be served.

Hospitality rites. When a stranger2 or visitor comes to call, there are hospitality rites which occur regularly. A spoon sweet (glyko), made of fruit preserves, is served with a glass of water. In addition, among the peasants who can afford it, an honored guest—especially in the case of men—may be offered ouzo or a rose or fruit liqueur. Among the shepherds wine is the only drink which will be offered.

Community festivals—the panighiri. We define "festivals" as community-wide events which may be celebrated by all of the village together. On these crowd occasions, the celebrants will be grouped either by family or by male friendship. Some community-wide occasions will be celebrated not en masse, but in the houses of each family. It is customary at these times for families to pay calls upon one another. Festivals include the name day of the local saint (the saint after whom the main church is named and who serves as the patron saint of the community), Easter, Carnival (preceding Lent), Harvest Festivals, the Day of the Cross (September 14), Beheading of St. John (August 29), the Sleeping of the Virgin (August 15)', Epiphany ( January 6), St. Basil's Day (New Year's), Christmas, and the Feast of St. Constantine and St. Helen. Which festivals are celebrated will depend upon the patron saint of the community, the region of Greece, the occupation of the folk, and the local traditions.

A church of St. Demetrius exists in one of our communities, and since his day, on October 26, coincides with the opening and the tasting of new wine, there is more than usual revelry on this occasion. For the shepherds St. Demetrius' Day marks the driving of the sheep down from the mountains to their folds on the plain. The feast of St. George on April 23 is also important for the shepherds, since it is on that' day that the flocks are moved to the mountains. St. George, a warrior-saint like Saint Demetrius, is patron saint to the Saracatzani.

Festivals need not take place within the village, for there may be a pilgrimage to churches dedicated to saints nearby. For example, the Panorio and Dhadhi people go to Saint Marina by the ocean on her day to celebrate ritual, to frolic, and to bathe there. Drinking will be part of those festivities.

Religious rites. As we can see, the festivals cited above are all religious occasions. They are characterized by a holiday spirit and the expectation that people will enjoy themselves while, at the same time, participating in a religious activity. We distinguish these fun-oriented occasions from the more solemn rites (although never deeply solemn in the North European sense of silence, serious-visaged piety, and ostentatious gravity that so often surround Protestant rituals) which accompany the Mass, Communion, funerals, and funeral feasts. A sweet red wine is usually served to communicants, although white wine can also be employed in church services. Funeral feasts occur after the burial of the dead, at memorial services forty days after interment and again three years later, and each year on All Souls Day.s3 At these meals white wine is served, but ouzo, brandy, or liqueur may also be consumed.

Healing. Various remedies may be employed to strengthen and to heal the ill. White wine, ouzo, brandy, sweet red wine, and beer are considered to have healing properties. In addition, ouzo, wine, tsipouro, and brandy may be applied externally as medicaments.

In the settings and occasions associated with the use of alcohol, one factor stands out: drinking occurs within a group context. It is done in the company of one's family or one's friends. It may be done in the presence of the whole community, or, at least, in the presence of a large number of one's neighbors, as at a fiesta or a sacred ritual in church. Its use in healing is an interpersonal event; the woman of the family who takes responsibility for nurturing and feeding will give the sick person his wine or brandy.

The people with whom one drinks are important people, persons with whom one is bound by ties of obligation, loyalty, emotion, and shared living. Except in the exercise of hospitality rites, one does not drink with strangers. When one does drink with a stranger, the host is usually in the company of his male friends or his family.

A second characteristic of drinking is that it is not a goal in itself or even the primary activity of the group. Its use in religious ritual is symbolic and secondary to the rites and intentions of the priest and congregation. Its use in healing is medicinal or magical, and again it is but one of many other on-going activities directed toward achieving or maintaining health. At mealtimes it is ingested as part of the meal—as another food thought to have its own nutritional or health-giving value, as well as providing appetite and good feeling, both of which in themselves are considered essential parts of the important family meal. At fiestas and celebrations its use is greater, but again drinking is only one of many on-going activities; it is one designed to bring pleasure, but in a facilitative fashion by enhancing one's ability to dance, sing, talk, be witty, or join in the festival mood. In the coffee house or taverna, its use is limited, and again is considered an adjunct to the social activities there. No one goes to a coffee house to get a drink; one goes to be with others and only incidentally does he have a drink.

Prescribed and proscribed foods and drinks. The choice of food and drink on festival occasions is prescribed, within certain limits, by custom. The use of alcohol is consistent with the larger prescriptions for diet and behavior at these times. Wine is an acceptable drink on any festival or ritual occasion which involves eating or drinking, whereas beverages with higher alcohol content are less often employed and their use is, in a sense, less traditional. Certain foods are expected to be served on certain occasions as, for example, lamb on the spit at Easter, St. Basil's pie with a coin at New Year's, and koliva (boiled wheat with almonds, sugar, parsley, raisins, fried flour and pomegranate seeds) for memorial feasts and offerings to the dead. Similarly certain foods are proscribed on those occasions designated for fasting. For example, on Clean Monday, which follows Carnival and begins Lenten fasting, one takes unleavened bread and abstains from olive oil, fish, and meat. Other fasting periods which are observed by the communities in the Doxario area include the forty days before Easter, the forty days before Christmas, every Wednesday and Friday, the first fifteen days of August, and the Day of the Cross, September 14.

For each period certain designated foods may be taken, just as certain ones must be avoided. Wine4 is an acceptable beverage during fasting and no proscription is set forth against its use at these times. The same holds for another cherished drink: coffee.

There are certain periods of fasting which are dictated by individual considerations rather than by the calendar. The bereaved family will abstain from elaborate foods before funeral rites and will observe such customs as not baking sweet things for one year following a death. Pregnant women may also fast; we found some villagers voicing the belief that wine was one of the substances to be avoided. By no means, however, did all villagers subscribe to this proscription.

Some villagers say that the lechona—as a woman is called during the forty days after the birth of her child—must fast, but again there is disagreement on whether or not she must avoid wine. Another individual fasting period precedes taking Communion; at this time people will also abstain from intercourse and will bathe as part of the purification ritual. However, they need not refrain from drinking wine.

During all the community-wide fasting periods, women and the older people are reportedly the two groups most likely to adhere to the strict regimes of avoidance and other customary practices. Our interviews showed a common core of agreement among all villagers on what the fasting and feasting periods are and what foods and drinks are appropriate to them; we did find lack of agreement on how stringently one should observe these customs. Some latitude apparently does exist in the degree of adherence to culturally prescribed food and drink regimes; nevertheless, tradition and immediate sanctions, as well as availability and economics, determine much of what one will eat or drink during any period or even on any single occasion. The latitude allowed an individual or family in the choice of diet for fasting, festive occasions, or daily regimes is not wide. The individual may decide whether or not to avoid meat on Wednesday or Friday, but should he fail to prepare koliva for the memorial service for the dead, or be seen by his neighbor cooking meat on the Day of the Cross, reputations would suffer. As a consequence, he prepares food with an eye to what the neighbors might say. These informal sanctions operate as mighty forces to determine conformity within a small community.

In addition, the individual has learned, as he grows up, to follow the customary practices. He looks forward to St. Basil's pie and lamb on the spit, he enjoys the koliva, and he takes pride in fasting, knowing he is doing what is right and thus accumulating a kind of credit for his soul—credits presumably tallied in a later life. Even if he wished to deviate, few are the directions he might take. The local economy produces but a few products; everyone must eat what he raises or, if he produces cash crops or animals, what he can buy locally. In Doxario, small grocers provide a few items from elsewhere, but for the people of Dhadhi and Panorio, and for the shepherds on the mountains, little or no choice exists—even presuming a person has the money and does not demonstrate that local distrust for products grown in unknown places or nourished by suspicious fertilizers that "spoil the taste of food."

What is true for food is true for wine. For example, villagers agree that the local wines are best: "The Athenians add yellow color to their wines and dilute them; ours we know are good. Our grapes produce wines with 14 per cent alcohol; elsewhere they have only 12 per cent." No store in the Doxario region stocks a single bottle of wine. It is all in barrels, filled with the local produce. To drink a foreign wine—that is, one from outside Doxario—might not be prohibited; but it is impossible.

Food and wine are intimately linked in regard to beliefs about ingested substances (which we shall discuss later) and in the custom that wine is not ordinarily taken without something to eat along with it. There is no purpose to it in the sense of any conscious effort to retard intoxication; but it is a tradition and, as such, it is accepted usage —pleasurable and unquestioned. At the coffee house-taverna, alcohol is served with olives, a bit of fish, bread, or cheese. During heavier drinking at festivals or celebrations, wine is accompanied by loaves of bread on the table, and often by lamb chops or kokoretsi (intestines of sheep broiled on the spit) . Eating and drinking occur together and are usages jointly governed by tradition.

LEARNING TO DRINK

Traditions do not govern in the abstract. They are learned and incorporated into the habits and opinions of individuals. In our three communities, learning about drinking begins in childhood. It is considered natural and proper that a child may taste wine and may have small amounts at meal times. There is some disagreement among villagers about when children should begin to have wine, just as there is some discrepancy between the age considered proper for starting to drink and the actual—but earlier—age when children first begin.

About a third of the villagers with whom we discussed this matter indicated that children should begin to drink wine in their early years (under ten), while the remainder agreed that it was proper to begin drinking wine sometime during adolescence. Since alcohol is rarely taken except in the form of wine, the age for tasting other beverages is difficult to ascertain; it is our impression that children may be allowed to taste ouzo when it is served and, indeed, may be given it for therapeutic purposes when they are ill.

Young boys visit the Doxario coffee house, where their manly antics earn them praise from the older men. Summertime brings several ten- to seventeen-year-old youngsters to the coffee house, where they sit all day, doing nothing, imitating their elders. From time to time, someone may treat them to a lemonade in return for an errand they are asked to run. The coffee-house sitting that the boys do results in their learning one of the most important functions of being a man: to take part in public life. The drinking is secondary, but it is in this context that the forms of public drinking will be learned.

No discernible difference emerges when proper drinking ages for boys are compared with those for girls. Nevertheless, distinct differences between the sexes in drinking behavior emerge as individuals grow older. The villagers do not agree about what are the proper drinks for women to take. About half of them contend that a woman may drink anything a man may drink, that there are and should be no restrictions on beverages. The other half contend that it is improper for women to take the stronger drinks • ouzo, brandy, raki, or tsipouro. A very few would prevent women from having beer, but none would deny them wine. Nor would anyone deny them the sweet liqueurs, including rose water-ouzo.

In reviewing within-family drinking patterns, we find that there are abstainers in many families, but these are no more often women than men. The most frequent pattern is for all of the adults in a family to take wine with some—but by no means all—meals. It is also more common for all of the children to drink wine with meals than for none of them to take it. The most common reason for children's abstinence is that they are too young; for adults, either men or women, the reason for abstinence is that it is bad for their health or they do not like the taste. The notion of its being bad for health is expressed in the sense that it makes an individual sick, rather than indicating any belief that wine has general deleterious effects.

It is more common for villagers to remark that the women and children takes less wine with meals than the men do. It is in this difference of the amount consumed that one sees a consistent relationship between sex and drinking behavior. In other words, men drink more, and more often, than women. As we have said, the coffee house is a male institution. Women do not participate in its affairs. At festivals it is the men who may drink heavily; women are expected to conduct themselves with propriety and modesty—conduct forms which are not seen as compatible with any loss of control or exaggerated behavior.

That drinking can become a focus of family dispute in which the underlying issue is neither the expressed one of health nor one of morality (as is often the case in the United States). but, rather, one of "manliness" versus effeminacy, is reflected in the following observation at an Athenian family dinner:

It was a pleasant gathering around a home-cooked meal at the usual late dinner hour (ten p.m.) presided over by the father. Grandfather and grandmother were present, as was the very sleepy only son, a nine-year-old. The mother was only intermittently to be seen, since it fell upon her to prepare and to serve a complex party fare in honor of the visitors. It would have insulted the philotimo of our hosts had we insisted too much on helping her with her duties. Neither she nor her old mother-in-law drank anything, except a very small taste of the sweet, strong after-dinner wine. Upon those occasions when she joined us at the table, a tense discussion arose between her and her husband, one which seemed like a continuation of a long-standing argument between them. The mother was quite perturbed for she did not want her beloved boy, Tassos, to have any wine, alleging that it might harm his health, or if not his health, then at least his liver might be damaged. The father insisted the boy have his glass of wine; he turned to us for confirmation and support: "In the United States is it all right for boys to have some wine with dinner?" he enquired, adding, "You are psychologists, tell her (the mother) that to drink is good for a boy!"

Clearly, the real but unverbalized question was not "to drink or not to drink" but, rather, "Is it good for Tassos to act according to the feminine code and become a mama's boy, or should he be allowed to act in conformity to the male code and become a real man?" The drinking was merely a sign indicating the different roles which Tassos' parents visualized for him. For his father the principle was very simple: to drink is what a real man does and what a boy has to learn.5

VARIATIONS IN ALCOHOL USE

We have seen that, in learning to drink, age and sex emerge as associated variables. Young children drink less than older children; older children drink less than adults. Boys and girls begin to drink wine at the same age, but they will grow to adulthood having learned that men drink more than women and, to some extent, that women are less likely to be allowed to take high-alcohol-content beverages such as

raki or ouzo.

Within age and sex groups not everyone drinks the same amount. While there is considerable uniformity in drinking behavior associated with settings and occasions, individual variation is also present. We examine some additional variables that appear to be related to differential usage.

Among the villagers of Panorio and Dhadhi, no one abstains from alcohol because of his social position or because he would be threatened by loss of status should he drink excessively at festive times. On the other hand, in Doxario we found both local physicians expressing the belief that they had to be especially moderate in their behavior. Neither man "rubbed shoulders" with the hoi polloi and neither would jeopardize his position through excessive drinking, even on feast days. One of the priests, Father Manolios from Naxos, appeared to hold the same view: that he must be moderate and conduct himself so as to maintain dignity and circumspection. The other priest, Father Dimitri from a local family, voiced no such sentiments and was proud of his image as a levendis, a warrior at heart, a hale fellow who was no slouch at drinking.

These two factors, income and leisure, operate to determine what each person may drink and how much he may drink with consistency. Some families are so poor they cannot afford wine with any meal; some can have it only for celebrations. Many families cannot afford any beverage but wine; some can afford an occasional glass of ouzo or beer. Only a few can afford to purchase beer or ouzo at whim In Panorlo, we found it was a rare family which had anything but wine in the house. In Dhadhi, only a few families had a bottle of ouzo or liqueur on hand. Among the Saracatzani, none had anything but wine on hand and not all had that. In Doxario itself, with its larger population and wealthier citizens, the well-to-do farmers, merchants, and professionals were the families who could afford to stock several bottles of liqueur or to have brandy on hand.

Beer is more expensive than wine; consequently, it has more prestige, especially in the lower classes. In Athenian high society, many of the American ways have been adopted. Whiskey and gin are served for their snob value. Their high cost, however, has prevented these American imports from penetrating to the villages. Greeks consider beer (and whiskey) as innovations, although beer was introduced about three hundred years ago. Serious commercial manufacture started about a hundred years ago. When the villager serves beer as a sign of esteem for his guest, or on Sunday and festival days, he may say, "We'll even have beer"; in other words, it plays the role of champagne for him. Aside from the city, upward-mobile Greek, the average person contends that hard drinks such as whiskey are needed for "quick heat" in cold climates. Greece, they say, is warm and cheery; hence, such drinks are not needed.

Among the villagers of Dhadhi and Panorio and the Saracatzani shepherds, leisure time is a rare commodity. Most of the days of the year are spent laboring in the fields or with the flocks or in maintaining property and possessions. We found that the coffee houses were empty except in the evenings, and by no means did every man have the energy or funds to join with his neighbors in socializing at night. People who rise with the sun retire with the sun, and few are the hours available for bending ears or elbows in conviviality. In Doxario, on the other hand, there were men whose wives had brought them a dowry or who had inherited good lands sufficient to enable them to survive with but little work. In some cases, survival was at a subsistence level—an income of no more than $30 or so a month, supplemented upon occasion by sending the wife to beg food from the landowner or richest farmer in the area. Nevertheless, these men could live with little work and their leisure was employed in the coffee house. Some we saw, almost every day, sitting there from morning until night. In the coffee houses of Doxario, a cadre of men were fixtures in the place, and the time—if not the inclination—to drink was theirs.

One of the Doxario town-council members, an able friendly man, explained his activities as consisting of doing as little as possible in his grocery store-taverna, so that he would have time to spend sittingin the shade. There he surveyed the unchanging scene in company with the habitués of his establishment, each drinking slowly from a glass of water and an aluminum cup of wine. He said, "If I wanted to work hard I could be a rich man. But why should I do that? I like the way I'm living. I want to have time. That is the best of all."

Some of the peasants of Dhadhi own vineyards which produce grapes for the local white wine.' None of them owns pine trees from which resin may be obtained but for a period of time in recent years some did contract with a landowner to tap a pine forest. A few families in Panorio also have vines and one family owns pine trees. Resin for their wine is either obtained under arrangement with a landowner or by surreptitiously tapping trees without consent.' Grape growers may sell the grapes to a merchant or to a cooperative, take them to a government press some miles away for pressing and use or sale, or press and make the wine at home. Determining the machinery and extent of these practices was beyond the scope of our study. It does seem reasonable to expect that those peasants who produce grapes are more likely to have wine on hand than those who do not, especially in the case of poorer farmers whose cash is limited and whose barter agreements must support subsistence. If this is so—and we believe it is—ownership of vineyards is an additional factor associated with wine availability and, potentially, with differential consumption.

While statistical data on production and consumption for the whole of Greece must await another time, it would at least be useful to present statistics on production and consumption for the Doxarlo region. Unfortunately one cannot. The problem is that the present machinery for gathering information on production does not allow accurate estimates. There is also confusion over the nature of that machinery. According to one statement of the official system for alcohol taxation and production control, all vines are counted and estimates are made of grape production for purposes of tax control and statistical reporting. Informal statements by wine growers in the region indicate, however, that no such vine-by-vine monitoring occurs.

It is also said that official requirements call for the pressing of all grapes in government controlled facilities. Such controls are to provide for taxation and statistical reporting of production. Informal reports from the wine growers state that the only grapes to be pressed in the controlled facilities are those which are sold and which are used in the production of wine for bottling and for the distilled products made from residuals left after the pressing. These distilled spirits are processed and bottled in Athens rather than locally.

Wine which is intended for local use is not produced under government supervision, say these growers; nor is it bottled. It remains in barrels and is either sold or bartered in the region. We have mentioned that the only wine obtainable in the Doxario region is in barrels; no bottled wine is to be seen. Bottled liqueurs, ouzo, and brandy may be stocked on store shelves in Doxario. The bottles, though, are dusty and grimy, giving the impression that such products move but slowly in local commerce.

CULTURAL THEMES AND VALUES

Philotimo, or love of honor, influences drinking behavior among men. The way to attack a male, the way to express aggression, envy, or competitiveness toward him, is to attack his philotimo. This is accomplished through shaming him or ridiculing him by demonstrating how he lacks the necessary attributes of a man. Consequently, avoiding ridicule becomes a major concern, a primary defensive operation, among rural Greek males. He does this in part by prophylactic means: he controls his family with an iron hand, so that members will not become the instrument by which he is shamed. He also avoids situations which are potentially dangerous to the philotimo. Merely being manly, having philotimo, is no guarantee that others will not test one's mettle through probing attacks. In a culture shot through with envy and competitiveness, there will be an ever-present danger from others. Consequently, a man with philotimo must be prepared to respond to jeer, insinuation, or insult with a swift retort, an angry challenge, or, if need be, by the lightning thrust of his knife. Philotimo is enhanced if a man is physically sound, lithe, strong, and agile. It is enhanced if he can converse well, show his wit, and act in other ways that facilitate sociability and establish ascendancy. Generosity in ordering food and drink at a party is one method of adding to everyone's enjoyment while, at the same time, earning points of honor and prestige. Greek informants mention that drinking helps a man overcome his cautious hold on his purse strings and permits him to pay freely for new rounds of wine and snacks for his party companions. His friends will then praise him for his bounty, envy him for his increased ability to command respect and admiration, and will even emulate him so as not to be outshone by his generosity.

One aspect of philotimo can also be a spur to heavy drinking. A man with special characteristics becomes the levendis, our modern Achilles. But whoever aspires to the honor of achieving levendis status must drink competitively and win and, in doing so, not impair his abilities, at least, as a social warrior. Uncontrolled drunkenness poses dread dangers to philotimo. To be a "bloated wine-sack with dog's ears" was an insult in Homer's time and its equivalent is one now. Insofar as a man loses control over his body, over his speech, over his capacity to interact with others effectively, he is endangered by drink. Such a condition exposes him to ridicule and deprives him of the means to respond effectively to challenge; especially dangerous is the fact that he loses his wit and thus fails to hear the warning which would enable him to cut off the challenger verbally—short of the knife.

Philotimo can be enhanced at the expense of another. It has a see-saw characteristic; one's own goes up as another's declines. The Greek, in order to maintain and increase his sense of worth, must be prepared each moment to assert his superiority over friend and foe alike. It is an interpersonal combat fraught with anxiety, uncertainty, and aggressive potentials. As one proverb describes it, "When one Greek meets another, they immediately despise each other."

Strife was a theme important to Hesiod, and it remains important today. Then and now, it spurs to greater endeavor by testing one individual's capacities—strength, cunning, wit—against another's. These jousting matches are a feature of the convivial drinking gatherings in the coffee house. A party begun with a good meal, and sped on its way with the juice of the grape provides an excellent opportunity for men to show their worth. They ingest huge quantities of food, generously compete in ordering more food and wine, and demonstrate their self-control, no matter how often they may be challenged to show the "white of the glass bottom"—that is, "bottoms-up."

Let us illustrate:

Two young daughters of Athenian friends of ours were visiting us on a Sunday when our social workers had already left for their own homes in the city. Learning of our visitors, the Doxario dignitaries—imposing, white bearded Father Dimitri, two handsome, good-humored, charming policemen, the mayor, the teacher from Panorio (who had just purchased two live chickens for tomorrow's dinner and kept them tethered, squawking, under his chair), and our special friend, Panaiotis, a farmer—offered all of us the rites of hospitality. As the evening began, we met at the coffee house under a flowering Judas tree. The men outdid one another in providing the party. One challenge was particularly instructive. Father Dimitri was amusing himself by gently corrupting one of our Athenian guests. Slyly he filled her glass whenever she looked away, smilingly he teased her about not having finished her glass, happily he nodded approval as she, responsive to the interest of the handsome priest, downed the white wine. He would then direct her attention elsewhere and proceed to repeat the cycle. It did not take too long before the poor girl was giggling outlandishly in her cups. Father Dimitri's next play was to smoke a cigarette, casually offering the young lady one, too. She refused, but soon he had persuaded her to smoke one and then another. It was, of course, improper that a girl should be seen drunk and smoking in public.

Father Dimitri had triumphed. We could imagine his thoughts: "So those city girls will drink with the men, eh? Well, I'll show her who is the master here." It was no accident that the next song he chose to sing, a Klepht song, told of the priest's daughter, the spawn of the sperm of the devil.

Another moving challenge occurred that evening. Our other Athenian visitor, a tall girl, flashing-eyed, arose dramatically. She held her full glass out toward the handsome policeman. "Aspro pato"8 she exclaimed, flinging the gauntlet which summoned him to a drinking duel. In one gulp she downed her wine (about six ounces), a feat symbolic of female equality with the male. Her opponent, a true gentleman, allowed her the pleasure, declining to chug-a-lug his cup. She smiled triumphantly. She had vanquished the man and with him some portion of her heritage of oppression as a Greek woman at the hands of men. But the young man could not quite bear it. When he believed himself unobserved, he quickly downed his glass; polite to the end, he at least proved to himself he was not to be bested.

The competition among men forces them to be inventive drinkers, or better said, inventive nondrinkers. As an evening progresses, one or another will surreptitiously hide his glass as the brimming jug is poured around. Casually he places his hand over the mouth of the glass, implying it is full while it is, in fact, depleted. Busily he fills the glasses of the others while pouring for himself a tiny splash. (On one occasion when we saw that to hold our own we must compete and win, we demonstrated an American brand of cunning and used our

own glasses as a pitcher from which we poured for others. The move was taken with good humor, even though it deprived our hosts of the pleasure of seeing their American guests under the table.)

Observers of Greek village life (Lee, 1953; Sanders, 1962 have noted that father and son do not frequent the same coffee house. Our experience supports this observation, although we did not find it an absolute rule. For the most part, father and son will either be in different coffee houses or will attend the same coffee house at different times. We believe that this practice safeguards the father from the son, and, as a corollary, safeguards the family from the aggravation of potentially disruptive conflict. The competitive wit, comments, and drinking in the coffee house are not a seemly form of father-son interaction. Overt competition in any form must not take place between people of unequal status. Neither the realities of power nor the forms of respect will allow it. As a consequence, we suggest that in the coffee house peers or men less closely bound by emotional ties are the ones who may contain dangerous elements of revolt.

ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING

The coffee house and the home are the places where people drink. In the village, the taverna, or coffee house is a place in which everything from eggs, soda, and coffee to lamb on the spit may be served. In most of the smaller villages, the coffee house is, first of all, a general store. Whether small or large, the coffee house is the meeting place for men. There they may sit for hours without drinking anything more intoxicating than several glasses of water, play tavli, and Watch time and the rest of the villagers pass by. If the occasion is more festive, a round of wine or ouzo may be ordered. A passing stranger, a cousin who lives in the next village, a representative of the agricultural bank, or a residing American, all of them provide an excellent reason for making the occasion a festive one.

In Doxario, the coffee houses are sometimes as spacious as 40 feet by 30 feet, with a patio outside for use in summer weather and tables set alongside the street where, on pleasant days, the habitués gather under open sky and leafy boughs. These coffee house-tavernas serve coffee, wine, the stronger ouzo, raki, tsipouro, and, with each alcoholic beverage, a glass of water and a bit of food, mezes. Meals may or may not be served, depending not only on the time and the day, but whether the pot from which the proprietor takes his dinner still has something in it.

There are in Doxario about eighteen coffee house-tavernas, ranging from the size of a postage-stamp bistro with only two or three tables to places capable of seating—at least outside—a hundred or so people. Estimating the adult male population of Doxario at about three hundred, one finds one coffee house for every seventeen males.

In Dhadhi, there is no splendor in the coffee houses, of which there are four serving the village. Three have patio areas bordering on the dirt road that runs through the town; all have a single inner room in which stand tables and chairs. They are simple places; gathering there does not depend upon atmosphere or aesthetics. The four coffee houses serve a population of about seventy adult males—in other words, there is one coffee house for each seventeen men.

Panorio has one main coffee house, although another villager has several tables and chairs located in her front room so that the men may gather there on a winter's evening. During our study a third villager was adding a room to his house with the apparent intention of opening an additional coffee house-grocery store (in Panorio the gathering place stocks the few staples which are available in the community). Considering the two available coffee houses, one finds, then, that there is one for every twenty-two men in the village.

While the number of men per coffee house in each of these two villages may suggest a rather considerable use of their facilities, observations indicate that such is not quite the case. Attendance is irregular and for many men a visit to the coffee house remains a pleasant but infrequent activity. Since each coffee-house owner in Panorio and Dhadhi operates the business only as a sideline—one usually requiring the joint effort of husband and wife—in addition to their ordinary farming activities, there need not be great profit from the enterprise for it to continue operating.

The Saracatzani, living as they do on the mountainsides, have no coffee houses at all. When the shepherd men wish to attend, they must walk or ride their donkeys into Doxario. The requirements of the sheep severely limit the number of such outings that can be made, especially in the summer season when the animals are on the mountain slopes.

The scope of our study did not allow us to gather detailed information on consumption of alcohol over time. Through observation and interrogation, we did derive information which allows us to make some estimates in regard to consumption.

At mealtime those families serving alcohol consume very moderate amounts. Women and children drink no more than 2 or 3 ounces of wine, men no more than 8. No alcohol is ordinarily served after the meal. If a man spends his evening in the coffee house, he ordinarily has one cup or, at the most, two cups of wine—normally 8 ounces—provided the evening is a quiet one without celebration, strife, or rites of hospitality. During rites of hospitality in the home, about an ounce or, at the most, 2 ounces of ouzo—usually diluted by at least a half and served in a glass of water—are offered to the men, and the male hosts match drink for drink.

If a male guest is being entertained in the coffee house, the occasion may become a festive one. This is especially likely on a Saturday evening, and on rare occasions the men may travel as far as Doxario-- or the men of Panorio as far as Spathi—to listen to music and to dance, sing, and drink. On these occasions men may be expected to consume six, eight, or ten cups of wine (about 24, 32, 40, or more ounces). These amounts they may also be expected to consume, provided they can afford it, at community-wide festivals. Celebrations at home, in which all ages and sexes are present, are characterized by less consumption on the part of the men.

The amount consumed during religious rites is small. Communicants and participants in the Mass receive only a spoonful of wine. Those participating in memorial feasts to the dead take no more than a few ounces.

The villagers agree that people drink the most at festival days and family celebrations. They also agree that men drink more-when together, as in the coffee house, than when they are with their families at home.

On certain rare occasions, a man may state his intention of drinking an extraordinary amount during the course of an evening, such as on a festive occasion at the coffee house or during a panighiri —a community-wide festival. He may say he wants to achieve ke fia, a state of happy mood, and set about with determination to arrive there. Under such conditions he may order raki, ouzo, or tsipouro instead of the traditional resinated wine. However, we feel that such conscious efforts to seek an altered state of consciousness or mood are rare. At least, we did not observe them.

A few villagers told us, during discussions about the times when people drink the most, that life circumstance as well as social setting influences consumption. It was their belief—one by no means expressed by all villagers—that when troubles came upon certain individuals they would increase their rate of consumption. The intent in such cases is presumably to reduce felt distress or anxiety.

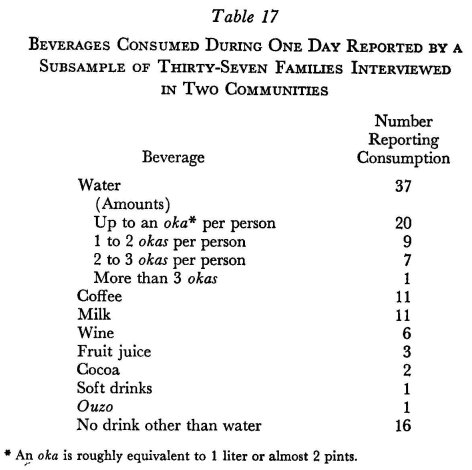

Families were asked to report their beverage consumption for the day prior to one interview. Table 17 below presents the results. Obviously, water is the primary beverage consumed. Since the interviews were conducted in midsummer, when temperatures over 100°F. were reached, it is understandable why such large amounts might be taken. However, one must be cautious about accepting the accuracy of statements as to amounts.

Table 17 indicates that for a particular midweek day more families reported no use of wine than reported use of wine. We were not in a position to make observations of alcohol consumption for a sample of individuals over time, although that would have been desirable. It is our impression that a J curve best describes alcohol consumption behavior over time, with most individuals clustering in the low-consumption or no-consumption end of the continuum and decreasing numbers extending to the high-consumption end of the continuum. Among the individuals whom we knew well in the three communities, none was observed to be inebriated during the months of our study. Among persons known to us casually, several were inebriated upon occasion.

The villagers in Dhadhi did not agree as to whether anyone in their village should be described as generally drinking too much. However, about half did name individuals whom they considered to be excessive drinkers. Another quarter of the respondents were defensive in regard to this question, apparently hesitating to cast aspersions on their community or its citizens. Two men were named as the village's heavy drinkers. One was a lively old man in his late sixties who, though an effective member of the community, was widely known for his mastery of the art of cussing and his pleasures in the wine cup. During our months of study, we did not observe him to be inebriated as defined by any visible behavioral signs. The other Dhadhi villager named as an excessive drinker was a man in his mid-sixties who stood out because of his more-unshaven-than-most condition, but was never observed to be drunk by any of the investigators. His wife was firm in her belief that he drank too much. During the medical examinations to which she and her husband went jointly, she stood behind her husband gesturing to the physician with hands and tilted head to communicate tippling without her husband's seeing it.

The villagers of Panorio completely agreed that some ,men drank too much in the community. Three men were named, each in his mid-fifties. One person, who was said to be too often drunk, was spoken of as a man without adequate philotimo. This characterization marked him as a deviant and as a man who was not accorded full respect in Panorio. The second man mentioned was also considered to drink too much, but his children's accomplishments and his own bravery during the war were so well known that he was respected as well as criticized. Perhaps, these conflicting attitudes of villagers about him accounted for the awkwardness we observed in their mention of him, as well as for their apparent reluctance to discuss his behavior.

The third person mentioned as a heavy drinker was said to share this characteristic with all the men of his clan, only more so. Since all the men are admired for their ability to hold their liquor, the sentiments expressed about this man were more in the nature of admiration for his levendis characteristics than criticisms.

Among the shepherds, none was spoken of as heavy drinkers and, during our observations, we saw no one who was inebriated.

In Doxario, we found more extreme behavior. There, in a population of a thousand, two men were mentioned as drunks, one of them serving as the town fool and whipping boy. The latter we never observed to be sober; beginning in the early morning, he staggered about on his pathetic rounds. The other drunk we rarely saw, but occasionally he was pointed out to us. There seemed to be no question that these two were unable to function at work and that their behavior was symptomatic of chronic alcoholism.

EFFECTS OF ALCOHOL

We limit our discussion of alcohol effects to behavior which is observed as a function of social setting and emerges as idiosyncratic and, in a somewhat different category, to those conditions associated with physical condition. We begin with the latter.

Reviewing the physical findings presented in Health and Healing in Rural Greece, we find no diagnosis of alcoholism made, nor do we find diagnosis of conditions commonly associated with alcohol use, such as cirrhosis and peripheral neuritis. On the other hand, we do find the physician recommending that one resident of Dhadhi and another of Panorio should curtail their alcohol intake. The Panorio patient turned out to be one cited by the villagers as a heavy drinker and as a man lacking respect. He was described by the physician as melancholic, supersensitive, and pessimistic. The doctor attributed his poor mental condition to prior surgery and sickness; his diagnosis was chronic gastritis, aggravated by the use of alcohol. His recommendation of abstinence was for the treatment of gastritis. The Dhadhi patient also proved to be one cited by villagers—and his wife—as a heavy drinker. He was diagnosed as a nervous and overweight person with high blood pressure who should eat less food and drink less wine. We cannot be sure that such a recommendation was not in response to the dramatic gestures of the man's wife as she did a pantomime in the examining room.

Reviewing the clinical findings on the other villagers described by their neighbors as heavy drinkers, we find no physical evidence derived from the clinical examinations to indicate any serious physical disorder attributable to alcohol. It is worthy of note that the two men identified by a physician as having health problems associated with alcohol use were both described as having psychiatric problems. Since it is very rare for village physicians to describe psychiatric difficulties in their patients, we may take it that both of these men presented highly unusual personalities. In neither case were the psychiatric problems related by the physician to the use of alcohol. For our purpose here, we must suggest that there is some evidence for the existence of personality disorder—defined by Greek standards—in two out of the three non-levendis, heavy drinkers who were medically examined. This is not to make a claim for the accuracy of psychiatric diagnoses or to presume any causal relationship between personality deviation and heavy alcohol use. It does suggest, however, the need to attend to individual personality factors in studying the process which leads to villagers' characterizing a man as an unadmired heavy drinker.

As for the men identified by villagers as heavy drinkers—but not noted by physicians to have any problem associated with alcohol use—we find that only two out of three appeared for medical examination. The third man, the clever clisser from Dhadhi, along with his wife and soldier son ( who was away on duty), failed to cooperate in this phase of our study. Of the two who did appear, both from Panorio, one was found to be without psychiatric or physical difficulties. The other was found healthy but overweight and in an exceptional characterization by the physician was termed "a joyful and teasing personality." Need we say this patient was our hearty levendis?

Doxario, with its thousand residents, might be expected to show a wider range of health problems and behavior than our tiny communities. We have already noted the presence in Doxario of two "confirmed" drunks. More serious health problems attributable to alcohol use were also found there. One physician reported that two of his patients had died either shortly before or during the study period as a result of cirrhosis of the liver. Both were elderly; one was a man and the other a woman. In addition, the pharmacist reported that one patient he knew had recently developed tuberculosis which he believed could be attributed to heavy drinking and poor nutrition.

It is worth noting at this point that one physician listed smoking, wine drinking, and eating heavy foods as partial evidence of a lack of "hygienic conscience" in the local residents. While he felt these were health threats, he said the local low morbidity rate was due to "good water and hard work."

When used at meals or hospitality rites or in the treatment of illness, wine is not expected by the villagers to change behavior. They consider it a facilitator of social or natural processes, just as it is at festivals and celebrations where larger amounts are consumed and where drinking is associated with a bon vivant spirit expressed in singing, dancing, flirtation, talking, and so forth. When this approved behavior occurs—and wine need not be taken for it to take place—no comment is made and the behavior is not necessarily attributed to the alcohol. In this context, the villagers observed that when drinking, people tend to be gay, to laugh, to joke, and to be happy.

On the other hand, behavior may occur which is notable in the sense that it is an exaggeration of ordinary actions or a deviation from them. In this framework, the villagers cited the following, in order of frequency, as effects of alcohol to be observed at or following heavy drinking occasions: ( 1) aggressive behavior including quarreling, cursing, beating wives and children, fighting, and killing; ( 2) overly talkative behavior, including shouting and being noisy; (3 ) boisterous behavior, as in breaking glasses or being capricious; (4) becoming sick, vomiting; (5) acting "crazy" and silly or showing irrational or unspecified deviant behavior—"going astray"; (6) sleeping or passing out; (7)' amorous behavior—chasing girls, making love; (8) uncoordinated behavior, such as staggering; and, least often (9), being silent or crying.

If we may take frequency of being mentioned as evidence for the effects of alcohol on these special occasions, we see two common trends: the enhancement of sociable "fun"—dancing, singing, talking, and flirting—and the release or aggravation of aggressive-competitive impulses leading to quarrels and violence. The most bizarre behavior by local standards—and, by inference, very unusual—is being silent or crying.

There are no themes that our own observations can add to the villagers' descriptions of what they do when they drink a lot. We may select from our observations and their reports to illustrate what occurs.

At an all-day hospitality rite for visiting friends: Everyone ate, danced, sang from one in the afternoon till eight in the evening. At eight, they sat down to a second major meal; chatting, drinking wine, singing. By midnight, the eleven-hour party was over. No one had become drunk; all had appeared to enjoy themselves immensely.

At an evening celebration in a coffee house-taverna: Two neighbors began to quarrel. Old grievances were voiced. Insults were hurled. Both pulled knives. One was felled with an abdominal slash. He was taken to Athens but the police were not called.

At a festival on the name day of a saint: Most of the village was present, sitting at tables which extended out into the street. Two bands played simultaneously and two singers vied to outshout one another. Three different dancing areas were occupied with changing groups of men and women, only men, only women, or especially talented solitary or duo performers doing folk dances. Wine and food were abundant; the noise level almost unbelievably high by our standards. Everyone appeared joyous. No one appeared to have lost control or to be unaware of the opinion of others.

On an ordinary evening: The town drunk of Doxario ordered food which he ate but then claimed he could not pay for. The coffee-house owner—who had been drinking wine—picked him up and threw him across the table. All the dishes were broken as they crashed to the floor. The owner then accused the drunk of having broken his good dishes and, with that, beat the man unmercifully for five minutes. The other habitués watched the proceedings without comment. Bruised and battered, the drunk was eventually allowed to crawl away.

In the hut of the Saracatzani: As honored guests, we were offered wine from a pottery jug. The host and his wife drank with us; the children did not. The flies which had fallen in the jug, or had fallen in the cups, were carefully plucked out of our cups by the fingers of our host before they were handed to us. Quiet conversation and good humor occupied us for several hours, while no more than two cups of wine were consumed.

At a harvest festival: The lord, owner of much land, invited all his workers to the harvest festival. Abundant food, a special treat of fruit, as much wine as one wanted, were available. Dancing and talking were the main activities for five hours. No one behaved in an idiosyncratic manner. There was keen competitiveness among the male dancers and some sharp humorous exchanges occurred, but in the presence of the great landowner, more than ordinary decorum was exhibited.

At the Daphni wine festival: Hundreds of varieties of wine could be obtained freely, in unlimited amounts and without payment. There may have been ten thousand people celebrating the new wine the night we were present. Two men only had to be carried out, drunk. They were carried out tenderly, protectively; our Greek hosts turned to us with a teasing smile, for the two men wore the uniform of the American navy!

INTERPERSONAL CONTROLS

How a sober person acts toward one who has been drinking heavily is shaped by their role relationship, by the setting, by general attitudes, and by idiosyncratic factors. A prime consideration is whether or not the drunken person has already been cast by community opinion in the role of shameful deviate—that is—a man without philotimo or a woman without modesty.

In the case of the confirmed drunk—one so defined by community opinion—there is common community rejection expressed by isolation, ridicule, abuse, taunting, and physical brutality. The confirmed drunk, unable to defend himself physically because of his weakness and lack of coordination and because of his psychic surrender to the role of town fool and punching bag, may be treated aggressively with impunity. The aggression directed toward him may be taken as a direct expression of the disdain of the community for his complete loss of manly virtue. It also serves, for some individuals, as a means for amusement, as men or boys engage in drunk baiting, or for the release of more idiosyncratic, sadistic impulses on the part of those who attack the drunk physically.

No segment of the community of Doxario takes the side of the underdog. This is understandable among individuals who are more concerned with acquiring power than in equalizing its distribution. Police authorities do not intervene either to punish drunkenness or to protect the inebriate, unless homicidal weapons are brought into play. A beating may be interrupted if police are present in the town square at the time, but even this is problematical. As long as no great damage is done, the police will not interfere with the normal course of events.

In the same way, bystanders will not intrude should one or two set Out to beat a drunk. His problem is not theirs; he is not family and his chronic alcoholism has made it unlikely for him to have built up among the residents any reserve of obligations which he might call upon by asking for assistance.

An individual designated as a heavy drinker but not one cast in the role of the town drunk is less vulnerable to assault. This is especially true if he functions effectively in the community in such a way as to have reciprocal obligations operating—ones which restrict the freedom of those who might like to deal with him harshly. In addition, the heavy drinker who is not cast in the deviant role still commands the loyalty of family—if not of kin—and the presence of his family members serves to deter any direct expression of aggression toward him. Nevertheless, if his drinking reduces his capacity to act "as a man," he will be the object of gossip, ridicule, and disdain. In our three small communities, one man in Panorio could be considered in such a position.

An individual who drinks heavily and perhaps frequently but who holds his liquor well is more respected than scorned. Other men will admire his capacity, and if his behavior includes the ability to dance, sing, talk, or fight well when he is drinking, he is a candidate for the role of a levendis. His sons will seek to emulate him and his peers will tell tales of his prowess.

The actions of family members toward the unmanly drunk are different from those of other residents. While others are free to scorn him, family members may not do so for they themselves are objects of scorn. The reputation of the father is applied to his wife and children. If he earns the disrespect of the community, they will all reap the fruits of his failure. The children will be ridiculed for their father's failings and the bad blood which they are assumed to have inherited. His daughters will find it harder to obtain a desirable husband, and his sons' blood will be questioned in the marriage negotiations. The wife may have the quiet sympathy of other women, for of all the groups in the community the ones tied by the gentlest bond are the women who know—and sometimes glory in—the suffering they share. Should the wife be beaten by her husband—and both the villagers and priest report that it is the sport of drunken husbands—she will deserve their sympathy. But she does have a final weapon: taking her dowry and going back home to her parents. In the case of the older woman, whose husband will be older and who is, according to our observations, more likely to be a heavy drinker, her parents may be either dead or living with her in her own house. In either case, she will have no other home to which to return.

We did not observe any wives being beaten. We knew wives whose husbands were reported to have beaten them. We also knew women with husbands who were reported to drink heavily, but who would hardly have dared to challenge their wives to any combat, verbal or physical. Seemingly, the Greek woman need not be submissive. Her response to her husband's drinking appears to be a function of personality and resourcefulness.

ATTITUDES AND BELIEFS

Attitudes and beliefs regarding alcohol are interwoven with cultural themes and life styles. Those that we consider most salient for health activities we set forth in Health and Healing in Rural Greece. We would present the following major areas for consideration here: the relationship between drinking and eating, the relationship between alcohol and other powerful or magical substances, concepts of moderation and their expression in regard to drinking, and orientation to altered states of consciousness. All of these play a role in regulating drinking behavior.

We have discussed the prescriptions and proscriptions which set forth the use of food and drink for feasting, fasting, and daily use. Insofar as one defines a food as an ingested substance taken for its presumed nutritive value, then wine taken at mealtimes is a food, for it is believed to be good for a person's health. Indeed, among all the liquids that the villagers listed as good for health, wine stood second to milk in value, while water ranked third, as reported during formal interviews. Among liquids considered to have special healing powers—as opposed to a mere good-for-you value—the various herb teas ranked first, milk second, and wine and ouzo third.

Just as foods can be dangerous to health, so too can wine. Among the foods, salted and fried foods and beans (pulses) were considered the most dangerous. Among the health-endangering liquids, alcohol in excess was nearly unanimously ranked first, followed by ouzo, milk, curative teas, and water. It can be seen from this that it is not feasible to set wine apart in some special category of substance; rather, some of the ways of viewing wine were closely linked to ways of looking at solid foods and nonalcoholic liquids. Among all of these classes of ingestible substances, certain items were considered good for health and certain ones bad for health, certain items had special healing qualities, and some had special dangers. Wine, interestingly enough —and to a certain extent ouzo—was listed as having all four effects.

There were certain similarities in the viewpoints that the villagers held toward water and wine. In rural Greece, water is no mere neutral substance taken when one is thirsty. It is more valued than that. The people pride themselves on being connoisseurs of water; long discussions ensue over the qualities of water from different springs or from different regions. In a land where it is scarce, water has come to be a focus of attention. While nearly everyone would agree that it is indispensable to health, some ascribe to it nutrient values, just as with food. Furthermore, it is commonly held, as with both food and wine, that water can also be dangerous. Too much water is bad, iced water can be harmful, dirty water can cause illness, and water taken on an empty stomach can cause the wandering navel.°

In Health and Healing in Rural Greece, we discussed the importance of food in Greece. We pointed out the emphasis placed on food as a substance which gives strength to ward off danger and how it is given to express love or to combat anxiety. Considerable anxiety results when an individual refuses food, shows loss of appetite, or is too thin. In our communities, nearly everyone agreed that being too thin was bad for health; while the same was said of being too fat, one must remember that the standards of desirable weight differ from those in the United States. What we might call "plumpness" is the villager's standard for female beauty—a standard which can verge into what Americans would call "fat" without any decrease in judged pulchritude. Greek infants are, by American standards, overfed, just as they are, by our standards, indulged. The heavy eater is much admired; we recall the pride with which a man described his elderly father's vitality in eating several pounds of bread at one sitting. The hostess forces food upon her guests and is truly gratified when a guest responds by asking for even more. In fact, the entire matter of food offering and food intake is a subject of considerable interest and even preoccupation.

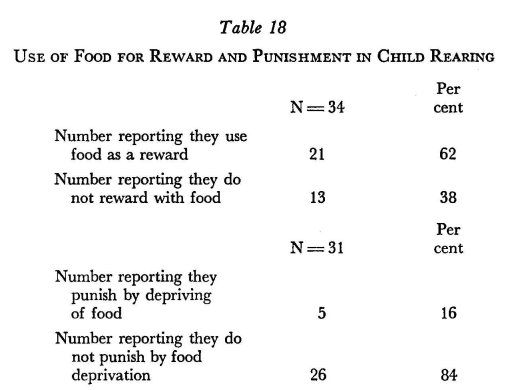

Given the importance of giving and receiving food, we tested in one of our questions the notion of food's being used as a reward for good behavior but not as a punishment for bad behavior among children. The table below presents the definitive answers given by villagers of whom the question was asked.

Our observations were consistent with these reports. Parents are more likely to indulge the young child than to punish him and more likely to feed him more than he wants than to deprive him of food he desires. We would suggest that a psychodynamic consequence of this practice, certainly reinforced by prevailing attitudes, is that children do not learn to associate being "bad" with food deprivation; as a result, they do not project onto foods associated elements of badness and forbidden desirability. Foods, then, do not take on a simultaneous positive and negative valence, which might, in turn, make them objects of approach-avoidance in the unconscious sphere related to the children's own feelings of badness and desire to taste the forbidden. Having ventured this far in speculation, we take the final leap to suggest that wine is similarly free from projected conflictual elements and that neither wine nor food will be as sought after as forbidden rewards (either primitive or symbolic) by individuals who feel either neurotic guilt or neurotic rebellion against punitive parental figures. We offer this as a formulation for further testing.

In any event, we believe it useful to consider drinking as one aspect of larger patterns of the ingestion of solids and liquids—all of which are considered to have nutrient value and all of which are subject to similar definition of use in terms of cultural edicts and associated emotional response.

The earlier book discusses the importance of the notion of powers residing in deities, objects, and substances and the use of magic as a means for directing these natural forces to serve the intent of men. We feel there is evidence enough to argue for the belief that alcohol contains power which may be magically controlled, or that in itself it is a means by which other powers may be propitiated or warded off. We see this belief reflected in the use of wine in the Mass, in the employment of alcohol internally and externally in healing efforts, and in its use at Christmas time when it is poured on the hearth along with olive oil as an offering (Megas, 1958)—in ancient times the offering was to Hestia, goddess of the hearth. We see it in the Cretan Christmas custom according to which the priest offers a bottle of wine to strangers on Christmas day (in the belief that the dead return at Christmas and may appear in the form of strangers). We see it in Chios (Argenti and Rose, 1949) in the notion that the "wine sack" or drunkard becomes a vrikolax or revenant when he dies. We see it in the belief that red wine is good for the blood. In Health and Healing in Rural Greece, we have shown that a relationship of sympathetic magic exists between blood and wine.

While there is no evidence that the ordinary use of wine is circumscribed by taboo, its sympathetic association with blood in folk tales, its usage as a symbolic equivalent of blood, its usage at sacrifice, and its connection with becoming a revenant suggest that the rural folk are not unmindful of its potential magical dangers and applications. Given the belief that alcohol, especially wine, has magical properties, it follows that it is a substance which must be handled with more than usual caution. The wise man does not play with magical forces beyond his control; his approach to any substance which has power in itself is likely to be respectful.

While there is an empirical basis to the belief that wine may have both beneficial and deleterious effects on health, this double-edged conception is held regarding many powers within and outside of man which must be subject to magical, ritual control. Among the foods for example, beans are likewise believed by some to be both healing and dangerous. While the Pythagorean strictures against beans are well known, their association in earlier times with the cult of the dead is suggested by recent excavations conducted by Dakaris (Archaeology, 1962) at the Homeric nekromanteion near Ephyra. There was' evidence at Ephyra of libation also ritually employed, quite possibly of wine.

Unquestionably, magical thinking plays a strong role in Greek rural life. One of the paramount features of forces magically manipulated is their capacity to work for the good or for the bad. Wine would seem to be one of these forces, and insofar as it is perceived as such, its use is subject to extraordinary caution. These same cautions may be inferred from institutionalized or ritual practices which are derived from antiquity. We surmise that man's early use and experience with alcohol was subject to considerably more magical practice than at present, but even in Homeric and classical times, it is possible to demonstrate that its use was highly formalized in association with its presumed efficacy as a means for propitiation of the supernatural, as well as in association with a belief about its "sympathy" with the blood—a belief, in turn, presumably related to the desire on the part of the dead to taste of it. These historical practices have led to institutional practices still extant, as seen in the Mass and possibly in the practice of adding resin to the wine." Institutions define conduct and attitudes long after salient beliefs have passed; in their stead myths and rationalizations appear. The use of wine is still a part of institutional practice, a part of ritual, and these usages operate effectively both to define use and to engender attitudes commending restraint in drinking.

It is also true that some ancient practices emphasized the ecstatic use of wine, as in the Dionysian rites. Evidence of ecstatic use is not found in our communities, but Megas (1958) reports that in Thrace, where the worship of Dionysos was strong, the festivities on the first day of the vintage took place, until recently, "with such frenzy that a casual observer might have thought himself among the ancient Greeks worshipping Bacchus." It is also likely that the brotherhood of the Anastenarides in Thrace contains elements of Dionysian ritual. These practices, even though leading to ecstasy, are structured in a complex institutional framework which does not allow for any remarkable individual deviation. Both in restraint and in abandon we may deduce ritual operations designed to manipulate a natural power.

One informant described drinking practices in Doxario by saying, "They intersperse moderation with occasional orgies." We believe this to be a fair description; Greek life styles do present an oscillating rhythm which is expressed in drinking as in other conduct. Moderation is an ideal. Wherever moderation is emphasized among rural Greeks, one detects their awareness of their own potential for the extreme. The goal may be to live with one another in neighborly tranquility, but when asked what happens when people drink heavily, they describe the quarreling, the knife fights, and the brutality which follow. Moderation is more than a value—it is a plea, a direction toward which to turn for balance after the frenetic drama.

We believe that the villager wants to guide his drinking conduct according to the value of moderation. ( Moderation, after all, is relative to practices and potentials in the Greek culture. When someone who has just consumed 2 okas of water says it is a moderate amount, he has in mind someone else who has just consumed 4 okas.) If the villager is not challenged by a situation or a threat that forces him to realize his extreme potential, his behavior will be consistent. Nevertheless, there are certain features of life which serve to trigger the Dionysian mode: competitive strife, the warrior code, the occurrence of festivals where revelry and orgy are sanctioned, the postulated tenuousness of boundaries of the self which reduces control in the absence of others, a certain readiness to disregard the morrow in favor of the flaming moment, and, finally, a capacity to experience emotion without restraint—an openness to the full flow of feelings and a willingness to immerse oneself within that affective stream. This last characteristic we postulate as reflecting both a value in and a consequence of a culture which emphasizes propriety rather than sin and which directs emotional expression rather than suppresses it.

Alcohol may be employed as a means to achieve an altered state of consciousness—the latter conceived of as an end in itself. Dulling of monotony, a warm glow, forgetfulness, the freedom for ecstasy: these are illustrations. We may ask to what extent alcohol is employed in this fashion in rural Greece. It is subsumed under our broader inquiry into the use of intoxicants, hallucinogens, and stimulants.