7 Findings and Recommendations

| Reports - Redefining AIDS in Asia |

Drug Abuse

I. KEY FINDINGS

1. Too few Governments in Asia have given AIDS the priority it deserves

The HIV epidemics in Asia have already affected millions of people, and they continue to grow. The Commission's projections show that an estimated 9 million Asians have been infected with HW since the start of the epidemic, and almost 4 million of them have died of AIDS-related causes. In 2007 alone, some 375 000 Asians were infected with HIV (a significant proportion of them women) and 420 000 died of AIDS.

AIDS is the leading cause of disease-related deaths among working-age adults in Asia. AIDS has emerged as the single-largest cause of disease-related deaths and work days lost among 15-44 year-old adults in Asia. In the absence of a major expansion of well-designed HIV responses, this will remain true for the foreseeable future.

Nevertheless, HIV responses in many Asian countries do not reflect the urgency of the situation.

2. Stronger leadership and political commitment on AIDS is urgently needed in Asia

Globally, successful HIV responses have been driven by strong commitment and leadership from political leaders. Without high levels of political support, it is impossible to overcome the obstacles that block effective programmes for controlling the pandemic.

Effective leadership tackles difficult issues and mobilizes productive action. Addressing AIDS brings to the fore controversial issues which mainstream society prefers to avoid—like sex work, drug use and homosexuality. Social taboos go hand-in-hand with the stigma and discrimination which people infected with HIV experience and which sabotage HIV responses. In a few places, courageous leadership from political and social leaders has challenged these taboos, defused stigma and mobilized the public into supporting successful HW programmes.

Asian countries with strong leadership have reversed the growth of their HIV epidemics. Asian leaders in places such as Thailand, Hong Kong SAR, Cambodia and Tamil Nadu in India had the foresight to recognize the threat of AIDS early on; they provided leadership that proves vital for reversing their epidemics. But such cases are the exception to what has been until quite recently a generalized lack of high-level commitment and leadership with respect to AIDS programmes in Asia.

More Asian leaders are now acting on HIV, but much more is needed. Evidence gathered by the Commission shows that more political leaders in Asia are taking up the AIDS agenda. Many national leaders have begun to provide some leadership support to AIDS programmes. This is evident in the larger commitment of resources, the creation of stronger governance structures for programme delivery, and the more meaningful involvement of affected communities in some places. At the same time, current responses in most countries are still too limited to reverse the epidemics. Leaders should—and can—do more.

There are still serious gaps in addressing AIDS as an emergency issue and recognizing its serious impact on individuals, families, and societies. Few leaders in Asia have made AIDS a genuine national priority. Efforts to create a supportive environment for HIV interventions remain scarce. In the past five years, hardly any country in Asia has brought its laws in line with the urgent need to provide those people most at risk of infection with HIV-related services. In many countries, the rights of people living with HIV are not yet explicitly safeguarded. Where top-level commitment does exist, resources often do not reach the provincial and local levels, leading to uneven, unpredictable and inefficient I IIV programmes. Moreover, few Government bureaucrats recognize the importance of the active involvement of communities. Resource commitments still fall short of the levels needed to halt and reverse the epidemic.

Politicians have key roles to play. The Commission acknowledges the important role of parliamentarians in AIDS advocacy in Asia. Some politicians have made valuable efforts to build awareness among their constituencies, lobby for HIV-related legislation, ensure that intellectual property laws support equitable access to medicines, press for more HIV resources, and hold their Governments accountable for their countries' HIV responses. Parliamentary committees on HIV have been set up in a number of countries. Increasingly, regional networks of Parliamentarians are also focusing on issues related to HIV and sexual and reproductive health.

Leadership and political commitment are the most important prerequisites for an effective HIV response. Asia's countries have the opportunity to reverse the HIV epidemics and undo the damage being done. Seizing that opportunity requires stronger leadership across the board. Leaders should begin by clearly demonstrating their support for HIV strategies that are pragmatic and of proven effectiveness.

3. Prevention still does not have an urgent enough priorityeven though effective prevention is bothfeasible and affordable in Asia

The vast majority of HIV infections in Asia occur during three high-risk behaviours (unprotected commercial sex, the sharing of contaminated injecting equipment, and unprotected sex between men) and one ostensibly 'low-risk' behaviour (sex between wives and their HIV-infected husbands). The Commission's country-specific analyses show that this conclusion applies across the region. The epidemics thrive where sex work is common, needle-sharing is widespread and men are having unprotected sex with other men. Casual sex outside of the sex trade is not yet a significant factor in Asia's HIV epidemics. HIV risk is highest among men. Male clients outnumber sex workers by 10 to 1; most injecting drug users in the region are men, and anal sex is extremely effective in transmitting HIV between men. Thus, most infections to date have been among men. The majority of women living with HIV in Asia were infected during sex with husbands with high-risk behaviour. The epidemics follow a common pattern in which HIV prevalence initially rises among injecting drug users, then increases among female sex workers and their male clients, and eventually grows among those clients' wives and children. Parallel epidemics among men who have sex with men have also reached high levels in many Asian countries.

A focus on these risk behaviours is essential for effective prevention in Asia. The extent and intensity of these risk behaviours in different countries ultimately shape the evolution and scale of their HIV epidemics. Differences in HW prevalence between countries are largely the result of variations in these behaviours, especially the prevalence of sex work. Therefore, in order to achieve maximum effectiveness, national HIV responses need to focus on preventing HIV infections in those sectitins of the local population that are most at risk for HIV, and on providing them with treatment and care services and impact mitigating support.

Asia's epidemics are best-classified according to an analysis of which risk behaviours are responsible for most new infections. In light of their basic commonalities, Asia's HIV epidemics should be classified not according to national HIV prevalence, but rather according to the behaviours that drive transmission. Such analysis enables one to pinpoint the current status and likely evolution of the epidemic, and makes it possible to implement those HIV interventions which have maximum impact.

National programme decisions should be based on their effectiveness in preventing new infections. Not all prevention programmes are equally effective. As a general rule in Asia, those programmes should focus on reducing HIV risk and removing those social factors that generate the largest number of new HIV infections. Such relatively low-cost but high-return interventions should form the core of HIV prevention efforts.

Currently, this essential focus is missing in many Asian countries. Few countries currently focus their prevention efforts on those population groups that are most at risk of becoming infected with HIV. Even when this focus is sought, the resulting programmes generally do not achieve adequate coverage.

In many countries, prevention efforts are not adequate to contain the epidemics. Except in Cambodia, Hong Kong, SAR, Thailand, and some states in India, prevention programmes are not demonstrably affecting the growth of HIV epidemics in Asia. Because programmes are heavily dependent on external funding, few Governments in Asia have taken full responsibility for, and ownership of, their HIV responses. Even in countries with documented successes, little has been attempted or achieved in preventing HIV transmission among men who have sex with men and injecting drug users, and between husbands and wives.

Asia's growing economies can finance stronger HIV programmes. Curbing HIV spread and transforming AIDS into a manageable, chronic disease is entirely feasible in a region that includes some of the most dynamic economies in the world. Given Asia's comparatively low prevalence and its rapidly-growing economies, the programmes required to contain the epidemic and provide care for those affected are well within the means of most Asian countries.

Efforts to combat a public health threat like AIDS often yield other, wider benefits. For example, the drive to combat cholera helped to improve sanitation systems in Europe, while the response to tuberculosis has helped improve hygiene practices and strengthen community health facilities, and avian influenza has promoted improvements in disease surveillance. Effectively addressing HIV brings a range of wider public health benefits, and serves as a platform for strengthening social development in Asia.

4. Sustainable success requires also addressing key social factors

HIV risk, decisions on HIV responses and the responses themselves are shaped by the contexts in which they occur. HIV-related risks do not occur in a social, economic or cultural vacuum. Numerous factors facilitate, aggravate or reduce HIV risk-taking. Many of these can be addressed successfully. Similarly, decisions on where to focus HIV interventions often are influenced by social, cultural, religious, political or institutional factors. Particularly important in this respect are stigma and discrimination, two factors which often undermine the implementation of effective prevention, treatment and impact mitigation responses. Finally, poor policies, weak governance and legal or operational barriers often also block effective action. HIV responses work best when such hindrances are removed.

Steps for addressing the factors that influence risk and affect programme effectiveness must be incorporated into the HIV response. Those factors must be addressed as an integral part of the overall HIV response. But the responsibilities for doing so should be spread appropriately across the system. Leaders should ensure that an 'enabling environment' for prevention, care and impact mitigation is established. Legislatures and institutions must address legal or institutional restrictions that undermine effective programmes. Non-governmental and community organizations, working with Government entities, need to develop strategies to convince the public to support appropriate efforts. Some of those interventions form an intrinsic part of the HIV response and should be funded accordingly. Some are best integrated into existing programmes and systems, with AIDS funds used as catalysts. Others are relatively low cost (for example, legal reforms) but need to become concrete, well-defined components of the overall response.

Women and poor households bear a disproportionate part of the epidemics' impact. Although the strong growth rates of Asian economies are helping to reduce poverty, rapid economic development is also widening economic disparities in the region. In many places, economic growth is also outstripping the pace of social development and the protective effects of social safety nets. Those trends could have significant consequences for the HIV epidemic and its impact, especially among women, who often are already socially and economically disadvantaged. Asian leaders need to recognize the importance of equity and social development as elements of an effective HW response. Effectively addressing HIV brings a wider range of benefits and serves as a platform for social sector reforms in Asia.

5. Treatment and care pose important challenges, but if prevention keeps HIV prevalence low, universal access to treatment becomes feasible

Identifying people in need of treatment and care is a challenge. While most HIV infections occur in people with specific risk behaviours, the illnesses associated with AIDS often occur long after they have changed those behaviours. Identifying those individuals can be a challenge, since they may no longer belong to the communities that are usually targeted for HIV testing. Stigma and discrimination against people living with HIV pose further difficulties, by reducing their willingness to access testing and other HIV services. Stigma and discrimination may also undermine efforts of affected families to raise the resources needed for antiretroviral treatment. Given the predominant patterns of HIV transmission in Asia, the challenge is to achieve wider access to a continuum of affordable treatment and care services to all those in need.

Financial sustainability of care and treatment programmes needs more attention. In countries where the provision of free or subsidized antiretroviral treatment relies heavily on external funding, the financial sustainability of those services is a concern. More research is needed to determine the best combinations of Government subsidies, insurance coverage, work-based health care, and private sector resources for ensuring sustainable access to antiretroviral treatment and care services.

Regional mechanisms that can help countries expand access to treatment and care are not being used fully. It is within the means of most Asian countries to deal with many of the financial, technical and logistical factors that currently limit treatment coverage. Collective and regional mechanisms can be used more fruitfully to negotiate favourable pricing, make bulk purchases, reduce costs and expand access to life-saving medications.

Prevention programmes must be expanded to make treatment and impact mitigation programmes affordable and sustainable. Even in Thailand, where prevention programmes kept HIV prevalence below 2 per cent, the recurring costs of antiretroviral treatment will soon be more than USD 200 million a year. National HIV prevalence is lower than 2 per cent in all other countries in Asia. If other countries can keep infection levels low, treatment and impact mitigation costs can also be kept down. Effective prevention is the first line of defence against rising treatment costs and growing impact mitigation duties.

6. Impact mitigation in Asia is needed primarily at the household level. The impact of Asia's HIV epidemics is most evident at the household level, where women, as caregivers, workers and surviving spouses, generally bear the brunt of the consequences. Women-centred impact mitigation needs to be at the core of a country's HIV response. Yet mitigation programmes for HIV and other catastrophic health conditions do not exist in most Asian countries. Ultimately, treatment is the most effective way to reduce the epidemic's impact. Treatment can keep families together, stop women from being widowed, prevent children from being orphaned by AIDS, and enable families to continue supporting themselves.

7. Programmes are not currently large enough to reverse the epidemics, provide care for those living with and affected by HIV, and mitigate the impacts of the epidemic. Despite the notable successes achieved by Thailand and Cambodia in reducing new infections, Asia overall has not yet put in place HIV responses that match the scale and patterns of its HIV epidemics. Instead, most countries in the region are in danger of losing ground to an epidemic that has proved resilient, particularly when presented with new opportunities for its spread. Currently, HIV prevention and treatment services in Asia reach fewer than one-third of the people who need them most. Despite the relatively low numbers of people in Asia who currently need antiretroviral therapy, only one in four (26 per cent) people are receiving it.

8. Addressing social exclusion and involving communities is critical to an effective response

HIV-related stigma and discrimination continue to undermine Asia's response to the epidemic—whether by sanctioning inaction or encouraging the harassment and maltreatment of people affected by the epidemic. Leaders must show greater resolve in challenging the ignorance and prejudice that surround the epidemic, and in supporting legislative and other changes that can reduce stigma and discrimination.

Activism is underdeveloped in many countries of Asia. Activism, advocacy and the active participation of people living with or threatened by HIV have been key elements in mobilizing and sustaining enhanced responses elsewhere in the world. Governments should be open to these vital elements of the overall response, and United Nations agencies and other development partners need to do more to foster partnerships and dialogue between Government and civil society.

Engagement of affected communities in planning, implementing and assessing HIV responses is weak. Because of the marginalization of people most at risk and the stigma experienced by people living with HIV, AIDS policies and programmes need to be informed by engagements with the affected communities. At present in Asia, the involvement of such key populations in national HIV responses is weak and, in many places, tokenistic.

9. Asia has the resources for an effective HIV response. Investing them sensibly will yield substantial returns

The countries of Asia can decide the future course of their HIV epidemics. The future of Asia's HIV epidemics will depend largely on whether sufficient resources are effectively deployed in HIV responses that achieve wide coverage among people most at risk. If the right choices are made, the entire region could soon be experiencing the same decline in the epidemic observed in Cambodia, Thailand, and Tamil Nadu.

Less than USD 1 per capita is needed for effective responses. The Commission estimates in most countries in Asia, an average annual investment ranging from USD 0.50 to less than USD 1 per capita, depending upon the level of HIV prevalence, if focused along the lines recommended in this Report, can halt and eventually reverse the epidemics.

The benefits of appropriate prevention, treatment and care programmes outweigh their costs. The Commission's research shows clearly that the advantages of appropriate action far outweigh the costs, and would bring benefits that reach beyond the HIV epidemic and the public health system.

II. POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

1. Leaders of Governments in Asia should clearly demonstrate their resolve and commitments to halt the spread of HIV in the region in time to achieve the Millennium Development Goal of reversing it by 2015. This cannot be done in one swift move. It requires a concerted plan of action—from policy to strategy to implementation.

Having reviewed the national HIV responses in Asia, the Commission has found that they follow predictable patterns, starting with either denial or panic before gradually evolving into better-informed but often uneven responses. The Commission is pleased to note that in many countries there is a commitment among top-level political leaders to speak out about AIDS. Mostly, though, this is confined to policy statements—a necessary but insufficient ingredient for a comprehensive and full-scale response.

1.1. The time has come to translate political resolve into effective action. Action means setting out policies, designing programmes, committing sufficient resources and putting into place strong governance structures for managing those programmes. Effective action also involves creating a supportive legal, political and institutional environment in which people most at risk can be reached with interventions.

1.2. Political leaders need to acquire a deeper understanding of the dynamics of the epidemic and its impact on individuals and families Low national HIV prevalence means that the impact of the epidemic is not yet obvious nationally in many parts of Asia. But in affected households and communities, the impact is severe. Leaders should be more alert and responsive to those realities.

1.3. Given the important role that politicians can play in supporting the HIV responses, the Commission strongly recommends that they set up HIV committees in their parties and parliaments. Where such committees already exist, they and their regional counterparts (such as the ASEAN Parliamentary Assembly) should be further encouraged to monitor the progress Governments make towards achieving Universal Access to HIV prevention, treatment, care, and support (as agreed to in the 2006 High Level Meeting on AIDS at the UN General Assembly) and expressed in Millennium Development Goal Six (halting and reversing the HIV epidemics). The capacity of these structures should also be strengthened in order to combat HIV-related discrimination, protect human rights, ensure adequate funding for HW programmes and in order to remove legal, regulatory and other barriers that block access to treatment, prevention, care and support.

1.4. Generating quality evidence and using it effectively is vital, needs to be given higher priority. The Commission's Report partly addresses this need, although it does so largely at a regional level. Similar work is needed at country level. Evidence of the epidemic's impact at various levels of society should be collected and collated regularly. The Commission's call for a biennial HIV Impact Assessment and Analysis, carried out by an independent agency (see Recommendation 3 in this chapter), is important in this context. Regional-level bodies, like the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), as well as UN agencies such as the UN Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP) can also produce evidence-based reports on progress against AIDS, and use them as advocacy tools for scaling-up responses at country-level.

1.5. Besides Governments, business leaders need to assume a more proactive role in the HIV response. Even though the epidemic's impact on their businesses may not be as damaging as in some African countries, failing prevention programmes will affect them in the form of rising medical expenditures, insurance payments, staff retraining costs and productivity losses. On the other hand, they are well-placed to build AIDS awareness and to mount prevention and treatment programmes among workers and their families. Leaders of industries involved in infrastructure delivery (and especially those employing large numbers of migrants) have a particular responsibility for dealing with HW in their workplace policies and programmes. Except for isolated commitments by some business leaders, the Commission has not yet witnessed organized efforts by the business community to meet these responsibilities.

2. AIDS programmes should be implemented through well-defined and efficient governance structures that are backed by strong political leadership and meaningful community involvement

The experiences of various HIV governance structures in Asia are discussed in Chapter 5. The Commission wishes to underline the need to improve arrangements in three aspects of programme management: National AIDS Commissions; national programme management structures; and the Country Coordinating Mechanisms of the Global Fund for AIDS, Tliberculosis, and Malaria.

2.1. Focus the mandate and membership of National AIDS Commissions on policy-making, coordination, monitoring and evaluation

Many countries have established National AIDS Commissions to spearhead and coordinate their HIV responses. Unfortunately, these structures are often large, unwieldy and, as a consequence, ineffective. The roles and responsibilities entrusted to these structures often have been poorly-defined and inappropriate. This has resulted in inaction, inefficiency, duplication, and confusion. On occasion, even the most basic elements of the HIV response have suffered.

The National AIDS Commission should be headed by the highest political authority if there is sufficient commitment to the HIV response at that level. Its mandate should centre on policymaking, coordination, monitoring and evaluation; it should not be responsible for implementing HIV programmes. Within those bounds, its roles and responsibilities—especially those that involve collaboration with health ministries—must be clearly defined. The National AIDS Commission should be compact in structure and membership. It should include only those key ministries that have key roles in implementing HIV programmes (the Health Ministry and, as appropriate, Ministries of Education, Social Welfare, the Interior, Police, Justice, by way of example). Each of these ministries should have their own HIVbudgets, and retain primary responsibility for implementing the respective programmes and projects that fall within their ambit. Membership should also include civil society, through elected and appointed community representatives (see Chapter 6), networks of people living with HIV and non-governmental organizations. National AIDS Commissions should have equal membership of both Government and non-governmental members and should feature a strong Secretariat to support their coordination functions.

2.2. Strengthen national programme management

The Commission is concerned about the weakness of management structures at programme delivery level in many countries (see Chapter 5), which undermines the effectiveness of national programmes and causes a waste of resources.

The Commission recommends that countries place senior and experienced managers at the helm of national programmes, individuals who also have a positive attitude about working with communities. These people should be selected in an open and competitive process. The managers should have the necessary financial and administrative authority to run programmes and access funds. A strong technical team should provide support. Once appointed, that team's tenure should be of a fixed duration in order to avoid the inefficiency arising from frequent rotation and transfers. The UN system and other development partners should also invest in building the capacity of the national programme manager's team to ensure its ability to manage a sustainable response.

Governance structures should be simple and the decision making process should be speeded up in such organizations. It would be wise to develop broad guidelines for a proper programme management structure based on best practices available within and outside the region. UNAIDS should be able to take up this role in consultation with Governments.

2.3. Improve the functioning of Country Coordination Mechanisms (CCMs)

The Global Fund to fight AIDS, 'Iliberculosis and Malaria will continue to play a central role in providing resources to national AIDS programmes. The Fund has established several governance structures for managing and monitoring the implementation of funded programmes. Thus, the Country Coordinating Mechanisms play a crucial role in recommending programmes for funding, and in monitoring the progress of their implementation. Those structures have an important hand in the performance of prevention and treatment programmes undertaken by Government and civil society organizations.

2.3.1. Make Country Coordination Mechanisms (CCMs) more transparent and responsive. The Commission recommends that the reform of the Country Coordinating Mechanism process be made a priority by country leaderships. Country Coordinating Mechanisms need to operate in a more democratic and transparent manner, and should encourage more meaningful involvement by civil society partners (especially community representatives). The Commission took note of several complaints from community leaders about the lack of transparency in Country Coordinating Mechanism activities, and the token involvement of communities. UN agencies and other development partners involved in the Country Coordinating Mechanisms have a special responsibility for ensuring genuine and meaningful participation of community representatives in those structures.

2.3.2. Let decisions be guided by the local epidemiological situation. The Commission emphasizes that Global Fund funding decisions should be solidly grounded in the epidemiological realities of countries.

2.3.3. Clarify relationship with National AIDS Commissions. In many countries the relationship between the National AIDS Commissions and Country Coordinating Mechanisms is not clearly-defined. While the Country Coordinating Mechanisms are usually under the administrative control of Health Ministries, National AIDS Commissions tend to be organized as multisectoral bodies for coordination purposes. The overall accountability of Country Coordinating Mechanisms to coordinating bodies such as National AIDS Commissions is often unclear. The Commission urges UNAIDS and the Global Fund to develop guidelines for fostering stronger and more effective links between these two important organs for coordinating AIDS programmes at country-level.

3. Understand the epidemic

As discussed in Chapter 2, the HIV epidemics in Asia share several basic features. In all countries, most new HIV infections occur during unprotected paid sex, the sharing of contaminated drug injecting equipment, unprotected sex between men, and when persons infected in that manner (mostly men) then have unprotected sex with their spouses and other sex partners. The extent and intensity of such risk behaviours ultimately shape the scale of the various epidemics. On current evidence, it is highly unlikely that Asia's HIV epidemics will grow independently of the commercial sex trade, drug injecting and sex between men. This makes it more appropriate to classify Asia's HIV epidemics according to their stages of evolution, rather than according to the disease burden they represent. What is needed is a classification system that distinguishes between the various stages of evolving epidemics: 'latent', 'expanding', 'maturing' and

Beyond the basic common features, certain differences in patterns and trends of HIV transmission (and risk behaviours) are evident between and within countries. These should be identified and properly understood—at both national and sub-national levels. HIV epidemics often are concentrated in 'hot-spots' that can be targeted with intensive prevention and treatment efforts. But risk behaviours and patterns of transmission change, making it vital to stay abreast of new developments in the epidemic, as well as to monitor and assess the impact of the HIV response on the epidemic.

3.1. Evaluate and strengthen strategic information systems. Each country has to strengthen its epidemiological and behavioural information systems (including the analysis of data generated by those systems) in order to achieve the best-possible, up-to-date understanding of its epidemic.

While HIV information systems have improved in most Asian countries in the recent past, there is still considerable room for improving data collection systems. In particular national data collection systems and their analytical capacity must be strengthened. The transparency of those processes and access to the HIV data should be improved as well.

3.2. Make better use of existing data to estimate the magnitude of the problems. The methodologies used to achieve such understanding should be regularly re-assessed (including through peer review) with a view to constant improvement.

In order to improve the accuracy of HIV estimates, country estimates should be based on pertinent survey data, including those collected in sentinel surveillance, HIV household and sectoral surveys.

3.3. Create a Regional Reference Group to support the countries efforts. The Commission proposes the establishment of a Regional Reference Group for Asia to support, review and validate country estimates and projections on HIV infections and resource needs. This would help refine the quality and effective use of HIV-related data and to set appropriate standards to guide programmes and policies.

3.4. Use in-country analyses to guide responses. HIV policies and programmes must be guided by country-owned HIV and AIDS estimations and projections, and by the sound analysis of evidence relevant to successful prevention, treatment, care and impact mitigation programmes.

3.5. Expand information systems to include data on responses. The coverage, quality and efficacy of prevention, treatment, care and impact mitigation efforts should be included within the ambit of information and analysis systems.

3.6. Conduct a biennial HIV Impact Assessment and Analysis. Each country should conduct a biennial HIV Impact Assessment and Analysis that would guide HIV policies and programmes. Such an Assessment would review the latest epidemiological evidence, identify new HIV 'hot-spots', analyse factors (including rapid economic and social changes) that can increase HIV transmission and hinder effective responses, assess the current HIV response (across various sectors), and project the impact of the epidemic (from the household level onward).

3.6.1. Conducting the HIV Impact Assessment and Analysis should be the responsibility of a high-level Government body, one which should include civil society representation (including representatives of people most at risk).

3.6.2. Each Assessment and Analysis should be compiled into a Report that is widely publicized and disseminated.

3.6.3. Countries must ensure that their HIV responses are tailored and adapted in accordance with the assessments and analyses emerging from this process.

4. Combat stigma and adopt measures to remove discrimination

Myths and misconceptions about HIV persist in every Asian country. Whether these myths are the product of ignorance or prejudice, they help fuel the stigma and discrimination that plague HIV responses. This is evident even in the healthcare systems of several countries, where studies have documented disturbing levels of ignorance about HIV and prejudice towards people living with HIV

HIV-related stigma and discrimination are distinct (although mutually reinforcing) concepts, and they are best tackled in ways that reflect those differences. Stigma and discrimination against people infected or affected by HIV continue to affect their access to employment, housing, insurance, social services, education and health care. Consciously or not, the reluctance of many social and political leaders to arm themselves with the facts and to speak out on these issues helps keep in circulation false claims about 'AIDS cures', myths about how HIV is transmitted, and the chauvinism that stigmatizes people living with HIV But there is ample evidence, too, that legislative interventions can reduce HIV-related discrimination and empower people living with HIV or groups at high risk of infection to organize themselves and participate actively in HIV responses.

4.1. Leaders should speak out against stigma and discrimination. Leaders in all walks of life, and at all levels in society, have a responsibility to stay well-informed about HIV

and to speak out against ignorance, prejudice and deception.

4.2. Correct or remove laws that support discrimination. Governments should repeal or amend laws or regulations that enshrine HIV-related discrimination, especially those that regulate the labour market, the workplace, access to medical and other forms of insurance, healthcare, educational and social services and inheritance rights (particularly of women). They should also ensure that laws and regulations aimed at safeguarding the rights of affected communities and persons living with HIV are introduced and enforced.

4.3. Create AIDSWATCH bodies to monitor and highlight discrimination. In order to help counteract HIV-related discrimination, the Commission recommends the creation of 'AIDS monitoring bodies'. These would monitor and address HIV-related discrimination in healthcare settings, in workplaces and educational institutions and in the widGr society. AIDS funds should be used to support the establishment of these AIDS monitoring bodies. Countries with existing Human Rights Commissions should ensure that these additional roles are integrated into their responsibilities.

4.4. Support the active involvement of people living with HIV. One proven way of reducing stigma against people living with HIV is by enabling and supporting their efforts to organize themselves as HIV advocates, educators and activists—and to forge partnerships with the media, healthcare providers, governmental and other civil society organizations. Funding, technical and logistical support can help them achieve this goal—equally, a more tolerant and facilitating approach from the authorities is necessary.

5. Adopt a human-centred approach and speak out on controversial issues

The criminalization of people most at risk undermines efforts to prevent new infections and provide treatment and care to people who are already infected. Research shows that where sex workers and drug injectors are targeted for arrest and prosecution, condom use tends to be lower and needle-sharing tends to be higher. Such policies drive people most at risk deeper underground, which makes the provision of outreach services not only more labour- and cost-intensive, but also less effective. In some countries, outreach workers and service providers are harassed and arrested. The Commission believes such policies are counter-productive and dangerous.

5.1. Address legal barriers to effective prevention in most-at-risk populations. Sex work, the use of narcotics, and sex between men is illegal in many countries. In Asia, where these behaviours are at the centre of the HIV epidemics, such legal provisions should not be allowed to hinder potentially effective efforts to control HIV. Countries should repeal punitive laws that criminalize sex between men.

5.2. Enhance services and protections for those most-atrisk of HIV. Governments are advised to shift their focus from punitive legislation towards policies providing protection for vulnerable people who are at high-risk of HIV infection, as well as for service providers and their beneficiaries. Rather than try to address HIV risk and transmission among groups most at risk as a legal issue, health-enhancing services should be made available or improved—such as sexual health services for sex workers and their clients, and men who have sex with men and harm reduction programmes for injecting drug users.

5.3. Remove barriers that prevent sex workers from organizing. Governments should remove legislative, policing and other barriers that prevent sex workers from organizing collectives, and to strengthen their access to services. Donors must remove conditionality or policies that prevent their partners from supporting organizations that work with sex worker organizations.

5.4. Bring public security people into the response. Governments should issue legislative and/or administrative directives to the police, correctional and judicial services to facilitate the provision of HIV-related services to people most at risk (including those who are imprisoned or interned).

5.5. Implement prison-based HIV programmes. Given the high imprisonment rates of people most at risk, Governments are advised to ensure that prisons and other correctional service institutions provide prisoners with HIV information and essential prevention services.

5.6. When controversy arises, speak out boldly. In order for these steps to be taken, opinion leaders must be bold enough to speak out on these issues and the controversies that surround them.

6. Promote and support AIDS activism and civil society advocacy

Despite the increase in funding available for combating the HIV epidemics, HIV has been slipping down the list of priorities in many Asian countries. This is partly because the epidemic is slow-moving and often 'hidden' It lacks the sudden and explicit drama of other epidemics, such as SARS. Activism and advocacy is therefore essential to keep HIV constantly on the agenda. Civil society organizations, the media, opinion leaders, United Nations agencies and external donors all need to support such activism and advocacy in order to help build an effective and sustainable response. At the global level during the last five years, such advocacy and activism has helped increase resources devoted to HIV reduce antiretroviral drug prices, and ensure greater involvement of civil society networks in the planning, programming and monitoring of HIV responses.

6.1. Expand the base of HIV champions to raise HIV's public profile. The Commission's analysis of national responses reveals a paucity of HIV champions among social and religious leaders, and media, entertainment and sports celebrities. In most countries, little sustained pressure exists from civil society groups and voters for dealing with HIV issues, the very groups that have proved so vital in HIV responses elsewhere. Societal leaders must encourage such people to become actively engaged and help in raising public awareness.

6.2. Encourage advocacy partnerships and activism around HIV issues. Governments should be open to these important dimensions of the overall response, while United Nations agencies and other development partners have a special responsibility to foster partnerships and activism at various levels.

7. Focus resources to achieve maximum impact

The Commission's review of national and international HIV responses shows that, of the estimated USD 6.4 billion required annually for a scaled-up response in Asia, only around USD 1.2 billion was available in 2007. These funds are not always used for programmes that are focused enough to have the maximum impact on the epidemic. HIV programmes in Asia currently span too many activities. This state of affairs stretches resources, complicates the task of programme managers and reduces the effectiveness of interventions. Current spending patterns also reveal a mismatch between resource allocation and strategic priorities. Multiple funding, political and other pressures have lead to programming decisions that are not fully formed and developed and inappropriate funding allocation. In addition, current domestic investment in HIV is low across most of Asia. As a result, much of the HIV response is externally-funded and -driven.

7.1. Prioritize the interventions that are most effective. The Commission emphasizes that interventions that can have the quickest, largest and most sustainable effect on reducing HIV transmission and the impact of the epidemic must be given priority in allocating 111V resources.

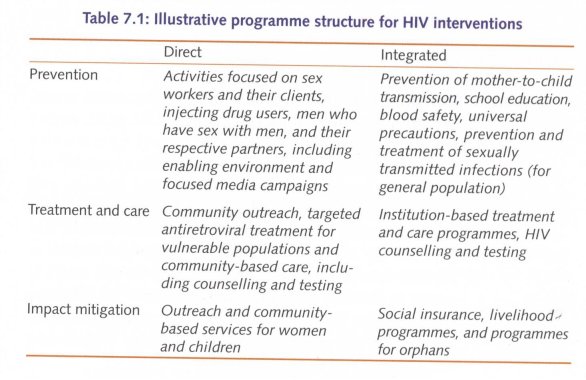

7.2. Focus on the high-impact interventions to reverse the epidemic and lessen its impacts. Based on its research, the Commission has classified current HIV programmes into four categories: Low-cost/High-impact, High-cost/High-impact, High-cost/Low-impact, and Low-cost/Low-impact. Prevention activities that focus on populations that are at risk and on creating a supportive environment are examples of Low-cost/ High-impact activities. Antiretroviral treatment wouldbe an example of a High-cost/High-impact intervention. Together, with women-friendly livelihood support and orphan programmes, these high-impact interventions should constitute the core of the HIV response. If countries committed resources to the response of the order of USD 0.50-USD 1.00 per capita range as proposed in Chapter 3, 1IIV epidemics in Asia could be reversed, 40 per cent of AIDS-related deaths could be averted (through the provision of antiretroviral therapy), and 80 per cent of women and orphans could be provided with social security protection and livelihood support.

7.3. Leverage additional resources to address other drivers of the epidemic and impediments to effective responses. A variety of other programmes and policies are available to address some of the underlying drivers of the HIV epidemics, the factors that aggravate their impact and that block or undermine the provision and use of HIV services. When successful, such programmes bring longterm sustainability to the HIV response and link with wider social development objectives. The Commission therefore recommends that additional resources be mobilized to leverage and support activities such as the prevention and treatment of sexually transmitted infections (aimed at the general population, as opposed to most-at-risk groups), condom promotion and provision for the general population, health systems strengthening measures, such as blood safety and universal precaution systems, sex education for school students, as well as strengthening social and health sector infrastructure and women's empowerment programmes.

7.4. Increase local investments in HIV responses. Governments should reduce their dependency on external financial support and invest more in their national HIV response. This can increase local ownership, and improve the coordination of HIV activities. An essential step along that path is the development of a normative guideline for resource needs, based on the kind of high-impact, focused approach the Commission proposes in this Report.

8. Take proven prevention activities to scale

At present, HIV interventions that focus on most-at-risk groups in Asia are very limited in their coverage. In a few countries, including Cambodia, Thailand and parts of south India, programmes for reducing HIV transmission during commercial sex have been introduced on an adequate scale. But such examples are exceptional. Most responses still favour small, local projects whose combined impact on the overall epidemic is marginal. The Commission is disappointed to report that in no country in Asia are prevention and treatment services for people most at risk currently available on anything like the scale needed to alter the course of the epidemic. Based on data collected from countries in 2005, prevention programmes reached only about one third of sex workers, only 2 per cent of injecting drug users and less than 5 per cent of men who have sex with men. The situation might have improved marginally since then, but it is highly improbable that service coverage has reached the desired levels. Epidemiological modelling suggests that if 60 per cent of people engaging in high-risk behaviours adopt safe behaviours (for example, consistent condom use with sex workers, use of sterile injecting equipment, etc.) the HIV epidemics can be reversed.

Unfortunately, most countries in Asia have not standardized the preventative measures required for the different groups most at risk. For example, needle exchange and drug substitution programmes are often treated as optional rather than essential HIV services for injecting drug users. Indeed, only four countries in Asia offer comprehensive risk reduction programmes for drug injectors, and none has a comprehensive prevention programmes for men who have sex with men. Peer education—a powerful component of interventions targeting sex workers, injecting drug users, and men who have sex with men—hardly exists, in several countries like Cambodia, China, Thailand and Viet Nam. These shortcomings stem partly from a lack of standardization in the programmes, which allows donors to fund programmes of variable appropriateness and effectiveness.

8.1. Ensure that prevention efforts are at a scale that makes an impact. Proven interventions should be scaled-up to reach the critical coverage thresholds that are needed to achieve a significant impact on the epidemic. It is primarily the responsibility of Governments to ensure that this happens. The Commission calls for some standardization of effective programme elements, which could be initiated and validated by the United Nations and other international partners.

8.2. Focus on geographic 'hot-spots'. HIV 'hot-spots' and high disease burden localities must be given priority when expanding coverage. The expansion of services should occur simultaneously in those places, and should comprise a set of clearly-defined activities and standards.

8.3. Define and implement the elements of a full prevention package for each at-risk population. The essential elements of prevention interventions for sex workers, injecting drug users and men who have sex with men should be defined for the Asian context both on a regional and national basis. Governments—supported by United Nations agencies, regional bodies and external donors—need to revise and/or endorse the standard elements of a comprehensive HIV prevention package for Asia, as proposed by the Commission later in this chapter (as described in Prevention Recommendation 1, below).

9. Ensure universal access to HIV treatment and care

Antiretroviral therapy is the mainstay of treatment for people who are infected with HIV In addition to successful prevention programmes, antiretroviral treatment is the most effective way to reduce the impact of the epidemic, especially in poor households, by prolonging producrive lives and enabling persons to continue to earn livelihoods. Affordability problems should not deny the poor these benefits. The Commission therefore recommends that provision of antiretroviral drugs, along with support services (such as CD4, CD8 and viral load tests) be fully subsidized. In order to secure better access for the poor, women, and children, a subsidy element also needs to be added for meeting transportation and other 'hidden' costs associated with accessing treatment services. The numbers of people in need of antiretroviral therapy in most of Asia are relatively low, and only four countries (China, India, Myanmar, and Thailand) account for about 90 per cent of that need. Yet, only one quarter (26 per cent) of people in need of antiretroviral treatment in Asia currently receive it.

The Commission believes that universal antiretroviral therapy coverage is well within the means of most Asian countries—and must therefore be achieved in the near future.

9.1. Delivery of quality antiretroviral therapy is a Government responsibility. Governments have a duty to ensure that a comprehensive package and continuation of effective treatment services (that is, first- and second-line antiretroviral drugs) is accessible to those who need it.

9.2. Integrate HIV treatment services into existing health systems and ensure equitable access. The Commission recommends that antiretroviral treatment programmes should be integrated into the general healthcare systems of countries. However, a comprehensive set of services which include expanding access to free voluntary testing and counselling, CD4 and CD8 testing, viral load monitoring when needed and the treatment of opportunistic infections should be funded out of the AIDS budget. In the case of poor people, transportation costs to reach treatment centres should be funded from programmes to ensure treatment compliance. Social insurance schemes should include antiretroviral treatment.

9.3. Engage affected communities to expand treatment access. Governments must assume responsibility for ensuring that free antiretroviral therapy is available and accessible to all who need it. Community organizations, including those representing most-at-risk groups and people living with HIV, should be involved in designing, implementing and monitoring this undertaking.

10. Make impact mitigation an integral part of the national response

Much of the impact of HIV occurs at the individual and household levels. The evidence shows that poor, affected households bear a disproportionate burden associated with HIV illness and death. This is not surprising, given the fact that social security systems in most of Asia are either weak or absent. The stigma experienced by AIDS-affected people (especially widows and orphans) means that gaining access to social welfare is often difficult. The low social status accorded to women, limitations on their access to employment and the denial of their property and inheritance rights in some countries (notably in South Asia) cause considerable insecurity—especially for women affected by AIDS. Indeed, most countries in Asia lack practical mechanisms to protect women against such consequences. However, studies suggest that a dedicated, AIDS-specific mechanism probably would be unviable in the predominantly low-prevalence settings in Asia. Strengthening livelihood security and income generation programmes—with special focus on AIDS-affected women—would seem a more prudent approach. For similar reasons, support for children orphaned by AIDS is best channelled through cash transfer programmes for vulnerable children.

10.1. Fund impact mitigation programmes through the national AIDS budget. The Commission urges Governments to include impact mitigation as an integral part of their national HIV responses, and to devote sufficient resources from the AIDS budgets to that end.

10.2. Ensure impact mitigation programmes should have the following components, at a minimum:

• income support should be available to women in AIDS-affected households, regardless of whether the women are infected with HIV;

• special support (including cash transfers or subsidies for education, transport and food expenses) should be available to families fostering children orphaned by AIDS;

• existing insurance and social security schemes must be reviewed and, if necessary, revised to ensure that they provide protection to AIDS-affected people; and

• laws are needed to guarantee equal inheritance rights for women and men.

10.3. Integrate into existing social security programmes wherever feasible. To the maximum extent possible, impact mitigation should be integrated into existing national social security programmes, while being funded out of the AIDS budgets. In countries where the social security programmes are weak or non-existent, AIDS impact mitigation programmes should be organized independently and fully funded. Indeed, the HIV epidemic provides countries with a valuable opportunity to strengthen their social protection programmes for catastrophic health and other expenditures. These programmes are not very expensive: the Commission estimates that for the whole of Asia, the total cost would be of the order of USD 300 million per year.

11. Ensure community and civil society involvement in all stages of policy, programme design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation

Civil society involvement has been shown to be a vital aspect of successful HIV responses around the world. In settings where groups most-at-risk also tend to be marginalized and vulnerable to discrimination, community and civil society involvement becomes even more important.

Organizations of people living with HIV, and groups representing or supporting people most at risk, must be actively involved in designing, implementing and monitoring HIV programmes. They should be represented on the key bodies entrusted with fighting the epidemic, including National AIDS Commissions and Country Coordinating Mechanisms of the Global Fund. These representatives should be selected in a transparent and fair manner While Governments need to facilitate such involvement, additional donor support is needed to ensure that sufficient financial, technical and human resources are available to enable civil society organizations to participate effectively. Donors should consider including genuine civil society involvement among their criteria for funding national HW programmes.

12. Increase community accountability through greater transparency, democratic governance and improved preparedness. The International Federation of the Red Cross Code of Conduct for non-governmental organizations is a useful guide for improving accountability and governance. The better-prepared, better organized and more accountable community organizations become, the more fruitful their collaboration with Governments is likely to be.

12.1. Community organizations must become more accountable for their conduct and performance. To that end, they should establish systems and structures that support their effective participation in the HIV response (including the selection of their representatives to participate in HIV structures).

12.2. Bring communities together to strengthen their ability to participate at the national level. The Commission recommends that community organizations form national alliances, which can in turn assign representatives to national bodies such as Country Coordinating Mechanisms and National AIDS Commissions on the basis of an open and transparent selection process.

12.3. Community organizations involved in national HIV responses need to collaborate with each other. They need to develop procedures and policies to inform such collaboration, including the selection of representatives and accountability procedures.

13. Use regional organizations to strengthen coordinated responses across the region

Dialogue, cooperation and the sharing of HIV programming experiences at regional level can help strengthen and extend Asia's HIV responses. Regional intergovernmental organizations have been involved in Asia's HIV response for some time, and groupings such as the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) have made high-level commitments to fighting the epidemic. However, those commitments are yet to translate into activities that capitalize on the strengths and advantages that such regional bodies offer

13.1. Regional intergovernmental organizations, like ASEAN and SAARC, should take leadership in enhancing HW responses and as platforms for promoting new understandings and approaches across the region.

13.2. Regional organizations should assume a stronger role in negotiations on antiretroviral drug prices, and regular monitoring of the AIDS response in member countries in high-level political forums.

14. Strengthen and sharpen the roles of United Nations agencies

The Commission did not undertake an extensive review of the functioning of the United Nations system in support of the AIDS response in the region. But it did conduct a strategic overview of the role of UNAIDS and its cosponsor organizations in supporting Asian countries' HIV responses. It found that the strong global advocacy for resources and political support for AIDS programmes mounted by UNAIDS has had a positive impact in Asia. UNAIDS should be commended for its achievement in substantially scaling-up resources available to AIDS and in strengthening the political commitment of Asian leaders to improving HIV responses in their respective countries.

However the Commission is concerned that UNAIDS is not yet effective in providing truly integrated technical support to countries, partly because of the numerous UN agencies that are involved in the Joint Programme. UN support programmes often lack coherence. One reason appears to be that the programmes sometimes reflect the corporate priorities of the respective agencies, rather than the national priorities of the affected countries. It is yet to be seen whether the division of labour among UNAIDS cosponsor agencies outlined in the Global Task Team recommendations will be put into practice.

14.1. The UN should continue to advocate for greater financial and political commitment from countries, based on its comparative advantage in this area.

14.2. UNAIDS should develop and support a coordinated regionally specific strategy for Asia. The Commission recognizes the unique role of UNAIDS in monitoring and evaluating national commitments and responses to the epidemic with respect to achieving the Goals set in UN Declarations on Universal Access and in the Millennium Development Goals. UNAIDS should develop and support a strategy that pertains specifically to Asia's HW epidemics and responses. It needs to ensure that UN agencies provide coherent technical and managerial support to realize such a strategy at country and regional levels.

III. STRATEGIES AND PROGRAMME IMPLEMENTATION

The policy priorities identified above have to be translated into effective strategies and programmes for implementation. Successful strategies and programmes require the following basic elements:

• establishing linked behavioural and epidemiological surveillance systems for tracking patterns and trends in the epidemics, and for gauging the coverage and impact of interventions;

• prioritizing the most effective interventions functionally and geographically, and investing accordingly;

• providing universal access to treatment (with a special emphasis on reaching poor households and geographic locations with a high burden of disease), and linking this to outreach programmes for marginalized populations;

• institutionalizing impact mitigation programmes to reduce the burden of the epidemic at household level, focusing efforts in high prevalence settings and giving priority to affected women and children;

• creating a supportive legal and political environment to facilitate and foster the active participation of most-at-risk and affected communities and people living with HIV while expanding prevention, treatment and impact mitigation efforts to an adequate scale.

• establishing efficient governance structures to secure appropriate involvement of all relevant ministries and sectors in programme formulation and implementation.

Irrespective of the roles assumed by other stakeholders and actors, the primary responsibility for an effective HIV response rests with the Governments of Asian countries.

The next section groups specific programmatic recommendations under four broad headings: prevention, treatment and care, impact mitigation; and programmatic issues for implementing those components. Because the components are inter-related, some recommendations cut across several categories.

A. Prevention

Effective and timely prevention efforts are the cornerstone of a successful HIV response. As stated in Chapter 3, in countries with expanding epidemics, every USD 1 spent on appropriate prevention programmes can save USD 8 in averted treatment costs.

The Commission's review of epidemiological evidence and country experiences in Asia highlights the fact that effective prevention which focuses on the behaviours that carry the highest risk of HIV infection can reverse the epidemic. Strong political commitment to give such programmes priority and to create an enabling environment for them is essential. Effective prevention interventions can keep the costs of operation, treatment and care manageably low.

The payoff would be considerably fewer people infected with HIV, and higher quality treatment and care for those living with HIV—thus sparing millions of lives, protecting livelihoods and saving resources that can be directed to meeting other development priorities.

1. Focus prevention programmes on interventions that have been shown to work and that can reduce the maximum numbers of new HIV infections

1.1. Focus on most-at-risk populations: Most new HIV infections in Asia are directly or indirectly attributable to unprotected paid sex, the sharing of contaminated, injecting equipment, and unprotected sex between men.

Focused programmes that have proved successful in preventing the spread of HIV among those groups most at risk of infection are well-documented, and should form the core of HIV prevention programmes. These groups include sex workers, injecting drug users, men who have sex with men, male clients of sex workers, and regular partners of these men. Effective prevention services for these groups can avert over 80 per cent of new HIV infections.

1.1.1. Introduce comprehensive harm reduction programmes

The Commission's review of research evidence from Asia and elsewhere confirms that harm reduction programmes are effective in reducing the sharing of contaminated drug injecting equipment, increasing condom use among drug injectors and reducing HIV infection levels among them. The Commission acknowledges that these measures are not always politically popular, but their effectiveness is beyond dispute. If introduced on a large-enough scale, they can contribute significantly to reducing the HIV epidemics in countries where injecting drug use is common.

Of the 11 countries in Asia with drug-related HIV epidemics, no country currently offers a comprehensive harm reduction programme that includes both drug substitution and needle (and syringe) exchange services on the required scale. Most of these countries offer one or the other of those services, which is inadequate and less effective. When large proportions of drug injectors are infected with HIV, substitution treatment becomes especially important. If successful, such treatment removes those infected persons from injecting networks, thereby reducing the chances of HIV transmission. Although WHO has included substitution drugs on its Essential Drugs List, legal barriers blocking the therapeutic use of such drugs remain in place in many countries.

• Governments must facilitate and support the introduction of integrated, comprehensive harm-reduction programmes that provide a full range of services to reduce HIV transmission in drug injectors.

• The harm reduction package should include needle-exchange, drug substitution and condom use components, as well as referral services (for HIV testing and antiretroviral treatment). The evidence shows that the overall effectiveness of such programmes suffers when such components do not form an integrated package.

• Legal obstacles blocking the implementation of comprehensive harm-reduction programmes (including the procurement of drugs for substitution treatment like methadone and buprenorphine) should be liftesi in the broader interests of public health.

• The overlap of HIV and Hepatitis C infections is also a matter of growing concern. Significant numbers of people infected with both viruses are dying of Hepatitis C complications, even when they receive and adhere to antiretroviral treatment. A successful needle and syringe exchange programme would also prevent Hepatitis C infections, thus reducing the very costly treatment of that disease.

• The Commission recommends that United Nations agencies negotiate price reductions for substitution drugs such as methadone and buprenorphine, as well as facilitate the streamlined and sustainable procurement of these drugs by Governments that introduce harm reduction programmes.

1.1.2. Increase the consistent use of condoms during paid sex

The consistent and correct use of condoms is the most effective method for preventing the sexual transmission of HIV during commercial sex. Indeed, the 100 per cent condom use programmes introduced in Cambodia and Thailand were crucial in increasing condom use during paid sex in brothels in those countries. However, the subsequent implementation of similar programmes has brought complaints about human rights violations from sex workers. In addition, the past decade has seen significant shifts in several Asian countries from brothel-based sex work to other settings (such as massage parlours, bars, streets, and parks). While the principle of 100 per cent condom use still holds, the reach and effectiveness of programmes modelled on the Thai experience is open to question. At the very least, sex worker involvement through peer education and protection of their human rights must be essential components of such programmes.

• More sex work interventions based on peer education should be introduced and scaled up. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation experience in India confirms that the scale of such programmes can be increased, but only when their various components (including the creation of an enabling environment) are well-defined and appropriately packaged, and when clear indicators are set and adequate funding is secured.

• Government has a key responsibility to ensure that condoms are available, accessible and affordable to sex worker and their clients.

• The Commission recommends that the use of female condoms (especially in paid sex) should be encouraged as an empowering measure for women and should be introduced where the operational feasibility of so doing has been demonstrated.

• Political and social leaders should be involved in mass information campaigns to educate the public about the numerous public health benefits of condom use. There should not be any restrictions on the use of the mass media to promote condom use.

1.1.3. Reduce HIV transmission among men who buy sex

Men who buy sex are the most important source of new HIV infections in most Asian countries. Many of them go on to infect their wives and girlfriends, women whose only risk behaviour is to have unprotected sex with their husbands or boyfriends. Interventions focused on these groups should be a key component of all Asian HIV prevention programmes. Focusing prevention efforts on sex work clients (who are mostly young and almost exclusively male) can bring considerable benefits as most of them participate actively in mainstream social and economic life.

• The Commission underlines the need to make commercial sex clients a central focus of HIV prevention programmes in Asia.

• Attempts to reduce HIV transmission in paid sex usually target sex workers. Several such programmes have been partially successful. But when interventions also target the clients of sex workers, the outcomes tend to be more impressive—as is the case in Cambodia and Thailand, where powerful mass media campaigns directed at clients played an important role in helping instil a virtual norm of condom use during paid sex. These media campaigns also have a long-lasting effect, as has been the case in Thailand.

• Other than media-driven campaigns, other programmes focusing on clients are in general poorly developed. There is an urgent need for innovative operational research and creative programming to reach these (mainly male) clients with effective interventions.

• One such approach would be to introduce HIV education and provide HIV services (such as treatment for sexually transmitted infections, and condom promotion) in work settings that tend to be associated with demand for sex work—such as men working in the military, the police, the merchant navy, and in long-haul transport, construction, and infrastructure projects.

• The Commission's review of evidence also indicates that programmes targeting commercial sex clients should not be morally judgmental. They should be pragmatic and must provide clients with the necessary information and services to protect them and others against HIV infection.

1.1.4. Reduce HIV transmission during sex between men

HIV transmission among men who have sex with men does not necessarily lead to a large-scale epidemic in the wider population. However a serious epidemic among men who have sex with men can potentially account for between 10 per cent and 30 per cent of new HIV infections, making it a significant factor in the overall HIV epidemic.

• A comprehensive programme to prevent infections among men who have sex with men includes intensive HIV education (especially peer education), provision of condoms and water-based lubricants, access to services for managing sexually transmitted infections, as well as support for local advocacy and self-organization.

• Legal and policy barriers that hinder the delivery of HIV services to men who have sex with men should be removed or, at least, relaxed. For example, anti-sodomy laws could be repealed or legislation to provide beneficiaries and service providers with immunity from prosecution could be introduced.

1.1.5. Protect the wives of men who buy sex, inject drugs or have sex with other men

Studies from South and South-East Asia have shown that 75-90 per cent of women infected with HIV are monogamous and were infected during sex with their husbands or boyfriends. Preventing HIV infections in sex work clients can therefore significantly reduce HIV infections in the wider population. Prevention of mother-to-child transmission is important and offers additional opportunities to reduce HIV infections among infants.

• No intervention aimed at protecting 'low-risk' women has yet proved effective on a large scale. The Commission recommends that high-quality research be undertaken to improve HIV interventions aimed at reaching those women who are likely to be exposed to HIV by their husbands.

• HIV counselling and testing for (male and female) patients seeking treatment for sexually transmitted infections and other indicative settings should be expanded.

• The Commission recommends that access to programmes for preventing mother-to-child transmission of HIV be expanded (especially in HIV 'hot-spot' areas) by integrating them into the existing healthcare system. Reproductive health services should be used as an entry point to increase women's access to HIV prevention, testing and referral services.

• The Commission notes, however, that in several Asian countries the majority of deliveries of new-born babies do not occur in medical institutions. Consequently, improvements in the accessibility and quality of antenatal care and institutional delivery are needed, the benefits of which transcend the HIV response and will help reduce the high rates of infant and maternal mortality in many Asian countries.

1.2. Target specific geographic regions

The epidemics in Asia show considerable variation at sub-national level. Early and effective interventions among injecting drug users in a handful of urban areas could still avert a large-scale epidgmic in, for example, Pakistan. In Viet Nam, injecting drug use is driving most of the HIV epidemic in the north, while paid sex is a more important factor in the south. Prioritizing prevention interventions according to the sub-national characteristics of the epidemic can save significant human resources and funds.

Most national HIV surveillance systems currently do not provide a detailed enough picture of the HIV transmission and behavioural patterns and trends at sub-national levels. These systems should be adapted to generate data and analysis in order to identify geographic 'hot-spots' of high-risk behaviour and/or high HIV incidence so that HIV programmes can respond more quickly and appropriately to changes in the epidemic. Local-level capacity should be strengthened or built so that these data and analyses inform HIV plans and programmes.

1.3. Create an enabling environment for HIV interventions

'Enabling environments' are essential for delivering HIV services to most-at-risk populations. The environment in which risk behaviour and risk reduction occur has a major bearing on how HIV epidemics evolve and how effective HIV responses become. Some contextual factors shape the potential effectiveness of HIV interventions—by preventing at-risk persons from understanding the HIV risks they face, accessing information and services that can reduce those risks, or being able to maintain safer behaviours. Such inhibiting factors often are linked to the conduct and practices of local law enforcement personnel, religious and other community leaders, and local powerbrokers. Even where national laws enshrine rights that should shield those groups most at risk against harassment and persecution, these laws are often ignored at the local level.

1.3.1. Engage local partners in building an enabling environment. At the local level, solving this problem requires delicate advocacy (and education) efforts directed at opinion leaders and law enforcement authorities so that the importance of HIV interventions are understood and supported. The networking of sex workers, drug injectors and men who have sex with men must make up an integral part of the enabling environment, as explained in Chapter 4. Harassment and violence against most-at-risk populations must be avoided, by involving police and other law enforcement agencies in education and communication programmes, and through supportive media campaigns.

1.3.2. Improve the legal and policy environment. At the national level, this requires supportive laws and policies—which may entail removing, altering or relaxing the enforcement of certain laws and regulations.

1.3.3. Build trust by addressing community needs. At the level of individuals, finding a solution requires recognizing and addressing some of the immediate needs of those groups most-at-risk, in order to foster the trust and rapport that is needed to deliver effective HIV services to them. This would include improving access to male and female condoms and lubricants, needle syringes, substitution drugs, sexually transmitted infection clinics, and to other basic health services (for diagnosing and treating TB, for example, or treating abscesses and sores).

1.3.4. Cost enabling environment activities and support. Activities related to creating an 'enabling environment' must be costed for HIV interventions, particularly at the project level; such 'enabling' activities need to be factored into intervention costs.

mil 206 Redefining AIDS in Asia

2 Avoid programmes that accentuate AIDS-related stigma

It is important to recognize that not all interventions aimed at most-at-risk groups are effective, and to note which have been proven to be ineffective, or even counter-productive. In their enthusiasm to initiate large-scale prevention programmes, Governments are seen to adopt certain programmes which accentuate stigma and violate the human rights of most-at-risk groups. These include 'crack-downs' on red-light areas and arrest of sex workers, large-scale arrests of young drug users under the 'war on drugs' programmes, mandatory testing in healthcare settings without the consent of the person concerned and releasing confidential information on people who are HIV positive through the media.

These initiatives can be counterproductive and can keep large numbers of at-risk groups and people living with HIV from accessing even the limited services being provided by the countries.

3. Take interventions to scale