2 The Future of HIV in Asia

| Reports - Redefining AIDS in Asia |

Drug Abuse

CHAPTER SUMMARY

• Almost 5 million Asians are currently infected with HIV; in 2007 itself some 440,000 people were infected with HIV and 300,000 died of AIDS-related diseases.

• Asia's HIV pandemic is now entering a second growth phase, which could push HIV prevalence to almost 10 million by 2020 if expanded prevention efforts are not introduced.

• Both the doomsday scenarios of ever-expanding epidemics and the notion that Asia's epidemics will automatically 'run out of steam' are misplaced.

• HIV epidemics in Asia continue to grow, but HIV responses in many countries still do not reflect the urgency of the situation.

• Reliable HIV data is a precondition for taking effective action against the epidemics. Countries should assess the epidemics regularly and adapt their responses accordingly.

• Current HIV surveillance systems are overly dependent on limited data sources. Countries need to examine multiple sources of data to come to an accurate understanding of the patterns, trends, and scale of the epidemics. Even where limited epidemiological findings are available, they are not used to inform policy and implementation strategy.

• HIV transmission in Asia is driven primarily by three high-risk behaviours: unprotected commercial sex, injecting drug use, and unprotected sex between men.

• HIV programmes should aim to prevent the maximum number of new HIV infections and this means focusing interventions on population groups that are most-at-risk of getting infected.

• But, Asia's epidemics are not limited to these most-at-risk populations. In many countries, adult men who buy sex, and their female partners, constitute the largest group of people living with HIV.

• Three out of four adults living with HIV in Asia are men, but the proportion of vvomen infected with HIV has also risen gradually. Most of them are in steady relationships, and are being infected by husbands and boyfriends who, currently or in the past, engaged in high-risk sex or drug injecting.

• The most sensible way to prevent HIV infections in women is to prevent their husbands from becoming infected through paid sex and drug injecting.

• Dynamic economic and social changes are underway in Asia, and high-quality research is needed to know what effects these may have on Hie evolution of HIV epidemics. But in most Asian countries, an increase in casual and premarital sex among women, by itself, is unlikely to lead to a net increase in new HIV infections.

• A new method of analysis of the various stages of the epidemic has been recommended. This will help Asian countries understand the stages of the epidemic better—than through the existing epidemiological classification of 'low', 'concentrated', and 'generalized' epidemics--and to tailor the responses accordingly.

ASIAN EPIDEMICS PRESENT MAJOR CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES

This chapter examines the characteristics of Asia's HIV epidemics, sketches the likely futures of those epidemics, and proposes a . framework for addressing them.

When expressed as a proportion of the region's large population, HIV prevalence in Asia seems low. Nevertheless, the absolute numbers are large. Almost 5 million Asians are currently infected with HIV, some 440,000 people got infected with HIV and 300,000 people died of AIDS-related diseases in 2007.1 Regionally, AIDS is estimated to be the single largest cause of death and morbidity due to disease for adults aged 15-44 years.2,3

Our understanding of epidemics in Asia has improved considerably in recent years. It is now clear that HIV transmission in this region is driven primarily by three high-risk types of behaviour: unprotected commercial sex, injecting drug use, and unprotected sex between men.4

Other important insights have also emerged. Although the epidemics are not confined to marginalized populations, the doomsday scenarios of ever expanding epidemics in Asia, are, on current evidence, quite misleading. 'The epidemic is predominantly concentrated among particular groups, and it can be contained if policies are targeted accordingly.

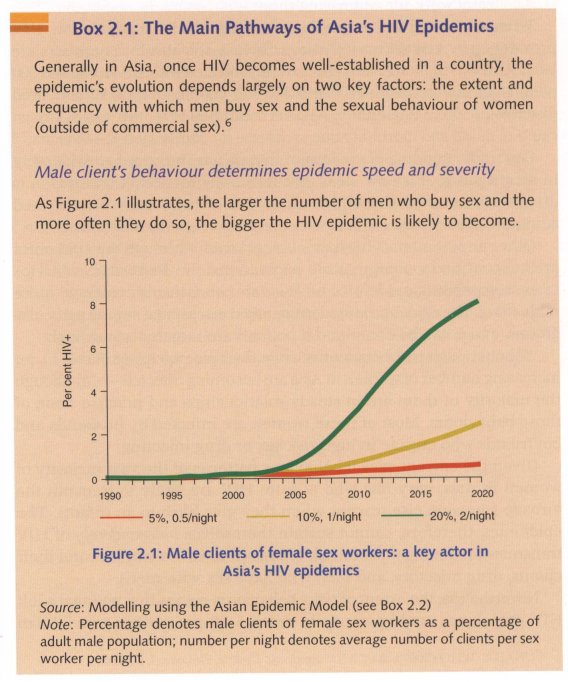

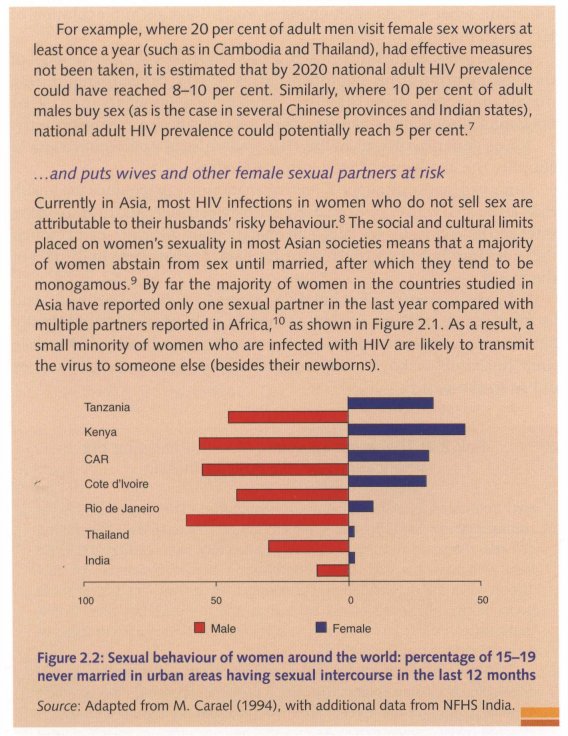

Although high-risk behaviours drive the epidemics (see Box 2.1), an indeasing number of women in Asia are becoming infected—even though the majority of them are in steady relationships and practise none of those behaviours. Most of these women are infected by husbands and boyfriends who engage in high-risk sex or drug injecting.

Given the current sexual behaviour patterns of the vast majority of women in Asia, very few who acquire HIV are likely to transmit the virus to someone else (except when they give birth to an infant). The epidemics, therefore, cannot sustain themselves independently of HIV transmission among most-at-risk groups (that is, sex workers and their clients, drug injectors, and men who have sex with men).

Nevertheless, the extent of risky behaviours means that national adult HIV prevalence could potentially reach 5-10 per cent in. some Asian countries.5 There is no evidence at present that these patterns of HIV spread will change substantially in the foreseeable future. At the same time, dynamic economic and social processes leading to changes are taking place in many Asian countries (as discussed below) and it remains uncertain what effects such changes might have on the evolution of HIV epidemics in the region.

For the foreseeable future, then, Asia's epidemics will derive most of their momentum from significant levels of HIV transmission during unsafe paid sex, drug injecting, and/or sex between men. This epidemiological reality translates into a major challenge and opportunity.

These generic patterns of the HIV epidemics in Asia would seem to simplify the challenge of preventing infections.

However, investing public funds in programmes that reduce the health risks associated with commercial sex, sex between men, and drug injection safer can be politically, socially, and operationally difficult—even though these are hardly isolated behaviours in Asia, or elsewhere in the rest of the world.

It bears repeating that in Asia, close to 100 million men and as many as 10 million women engage in at least one of these risky behaviours, and many more women may be at indirect risk because their husbands or boyfriends inject drugs or practise unsafe sex, or did so in the past.11

Box 2.2: The Asian Epidemic Model: Analysing the Implications of HIV Policies in Asia

HIV epidemics in Asia share many similarities. The large number of commercial sex clients creates fertile ground for HIV:to spread. The sharing of needles among injecting drug users causes HIV to spread rapidly, while men who have sex with men contribute an increasing number of new infections as the regional epidemic among them grows. The size of these populations, their levels of risk behaviour, and the starting points of HIV transmission vary from country to country. But the overall pattern tends to be consistent across the region.

In 1998, the East-West Center and its Asian collaborators began developing the Asian Epidemic Model, a policy tool based on the common regional patterns of HIV spread. The model incorporates the key populations affected by HIV epidemics in Asia: clients and sex workers, injecting drug users, men who have sex with men and the wives of these most-at-risk men. Using country-specific data on the sizes and behaviours of these groups, the model simulates the tranSMission of HIV from one person to the other through unprotected sex, needle-sharing, and mother-to-child transmission.

This allows for the development of country-specific models that capture diversity in the factors driving the epidemics in various countries of the region.

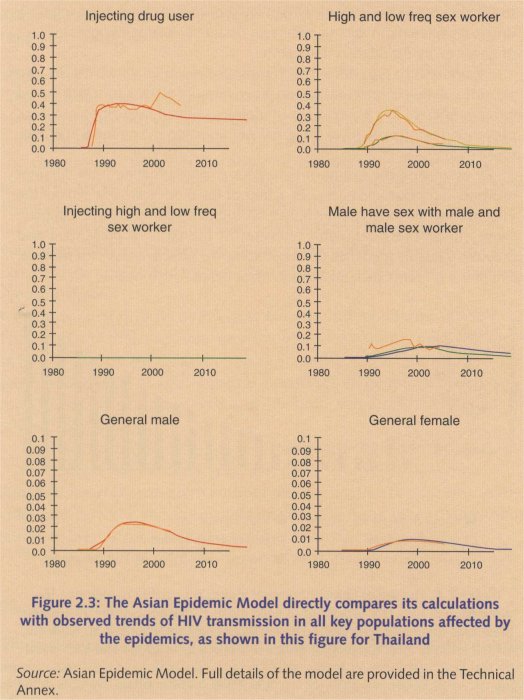

One important feature of the Asian Epidemic Model is that it directly compares its calculations of HIV levels against the observed trends, as shown in Figure 2.3, which provides a valuable check on how well the model is reproducing actual trends. The Center and its collaborators have applied the Asian Epidemic Model and found close agreement between the predicted and observed HIV trends in settings as diverse as Cambodia, Thailand, Jakarta (Indonesia), Ho Chi Minh City (Viet Nam), and Guangxi and Yunnan provinces in China.

The model projects future HIV trends based on the population sizes and risk behaviours that are provided as inputs. This makes it a powerful tool for policy analysis. One can use it to generate 'what if' scenarios: What if Cambodia had not increased condom use between sex workers and clients to 90 per cent in the 1990s? What would have happened if the injecting drug user epidemic in Jakarta had never occurred? Examples of these types of analyses are included in this chapter.

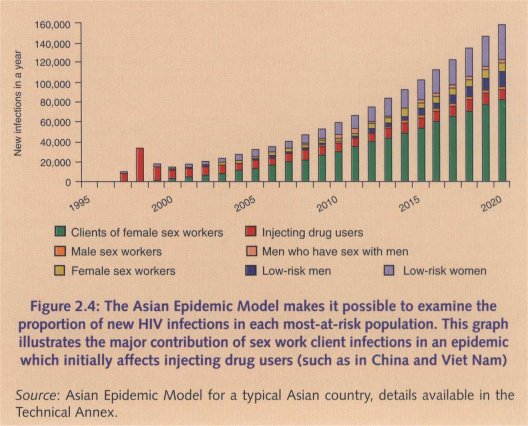

In addition to projecting HIV trends, the Asian Epidemic Model also provides detailed information on how new infections are distributed among different key populations. In doing so, it can help pinpoint where prevention efforts can have the greatest impact on the national epidemic (see Figure 2.4).

By estimating the extent of behaviour change resulting from different prevention programme packages, a user of the model can also explore the effectiveness of programme choices on future epidemic trends. Coupling those effectiveness data with estimates of the costs of prevention also provides valuable guidance on maximizing the effectiveness of responses. Chapter 3 presents such analyses in more detail.

Using the Asian Epidemic Model, the Commission has prepared a set of projections for Asia, which form the basis of some of the policy analyses presented in this Report. Chapters 3 and 4 use those analyses to examine which responses in Asia are the most cost-effective and bring out the best results. The Technical Annex to this Report describes the Commission's projections and analyses in detail.

Behavioural variations explain the diversity of HIV epidemics in Asia

Beyond their basic, shared features, HIV epidemics occurring in Asia vary considerably. The extent and the pace at which they evolve differ from country to country. Often there are also significant variations within countries. In some areas, HIV is circulating mainly among drug injectors and their sexual partners, in others it has become entrenched in the sex trade, while elsewhere the virus has not yet established a strong presence. Those variations depend primarily on differences in the extent and types of risk behaviour being practised and the point at which HIV was introduced in these places. Notwithstanding such diversity, efforts to feduce the spread and impact of HIV in Asia have to start by examining two questions:

• Who is currently most likely to become infected with HIV? The answer to this question requires an understanding of current levels of HIV infection and risk practices in most-at-risk groups, as well as some knowledge of the absolute numbers of people who engage in such high-risk practices. What is needed, therefore, is reliable HIV-related information.

• In the future, which behaviours are most likely to produce large numbers of HIV infections?

Here the answer requires a solid understanding of the dynamics of the epidemic: how the various groups most at risk interact with one another, and hovv HIV is transmitted from one group to another.

The next section explores these questions.

The risks of the sex trade

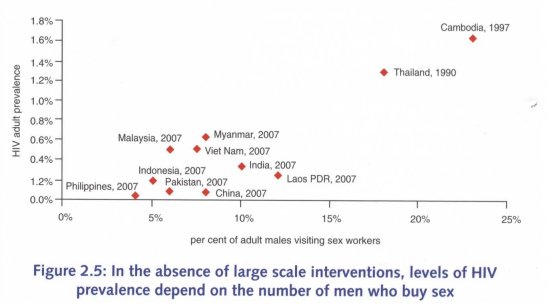

Three key factors explain why HIV prevalence has risen so rapidly among sex workers and clients in some parts of Asia but not in others: first, the proportion of men who visit female sex workers; secondly, client turnover; and thirdly, levels of condom use during paid sex.

Men who buy sex outnumber drug injectors and men who have sex with men, by a large margin in Asia. It is estimated that up to 37 million men in China buy sex regularly, 12 as do about 30 million in India.13 Meanwhile, Indonesia estimates that more than three million men buy sex each month.14 On an average, in Asia, there are about 10 male clients for every sex worker.15 In addition, most men who buy sex from women are either already married or will get married. Infected clients or former clients potentially put more people at risk than any other population group. The proportion of men who have unprotected commercial sex is probably the single most important determinant of the potential size of HIV epidemics in most of Asia.

Source: Graph is based on estimated national adult HIV point prevalence, the percentage of men who visit sex workers (obtained from country-specific secondary data sources). Details are available in the Technical Annex.

Note: Both male clients and HIV data for Cambodia and Thailand are for scenarios in which major interventions have not yet been introduced.

It follows that interventions which can prevent HIV transmission to and from male clients of sex workers are likely to be the most effective in controlling HIV epidemics in Asia—a conclusion underlined by Cambodia and Thailand's experiences.

Once significant behaviour change is achieved among the male clients of sex workers, such change can become permanent. In Thailand, for example, the effects of its HIV campaigns in the early 1990s are still evident in the fact that fewer men visit sex workers and consistent condom use during paid sex has stayed relatively high, despite the fact that prevention efforts subsequently waned.16

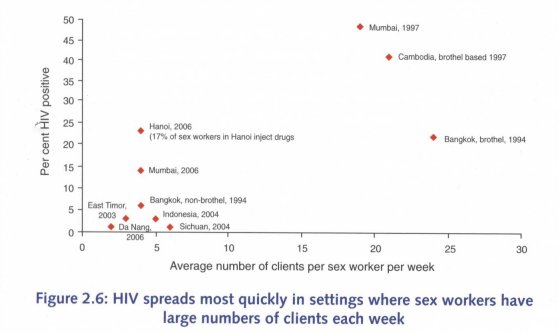

The second factor relates to the turnover of clients. The more clients a sex worker has in a day or a week, the more opportunities there are for HIV transmission.17 High client turnover, combined with high susceptibility to HIV infection (due to the presence of other sexually transmitted infections, for example) can create a critical mass of infections that can spark the rapid spread of HIV within sex trade.

Source: National HIV and behavioural surveillance systems

Note: Data on client turnover and HIV prevalence among sex workers are drawn from various data sets. Detailed references are provided in the Technical Annex. This graph depicts an ecological analysis and does not establish causality.

Does this mean that HIV prevalence among sex workers and their clients will stay low as long as the volume and turnover of clients is relatively low? Although HIV prevalence is unlikely to become very high among sex workers in places with low client turnover, this is true only if clients are uninfected. Many countries are seeing an infusion of HIV into commercial sex networks from other sources, primarily drug injectors. As a result, in Indonesia, Viet Nam and parts of China, for example, HIV infection levels have been rising among sex workers and clients. This rise is probably due to the large proportion of male drug injectors who buy sex (between 28 per cent and 52 per cent in four Indonesian cities in 2004, between 14 per cent and 43 per cent in seven cities in Viet Nam in 2006, and around 25 per cent in a number of sites in southwest China in 2004).18 This relationship is discussed in detail below.

The third factor involves condom use. Alarmed by a rapid rise in HIV prevalence among sex workers, the Thai authorities in 1991 launcheda pragmatic campaign to encourage the use of condoms, especially in commercial sex. More clients began to use condoms more often. In northern Thailand, condom use among 21-year old men (selected by ballot for military service), rose from 63 per cent in 1991 to over 90 per cent in 1995. Simultaneously, HIV prevalence dropped among these young men (from 11 per cent in 1991 to 7 per cent in 1995)19 and among sex workers (from an 58 per cent in 1991 to a still-high 44 per cent eight years later in the northern Thai city of Chiang Rai, for example).20

Similar programmes have had comparable results elsewhere. In Cambodia, HIV prevalence among 'direct' sex workers fell from 39 percent to 21 per cent between 1996 and 2003, and among 'bar girls' who sometimes sell sex, it declined from 18 per cent to 12 per cent over the same period.2I HIV prevalence among female sex workers in the Indian city of Chennai fell from 8.2 per cent in 2000 to 2.2 per cent in 2006, with some 90 per cent clients claiming they used a condom during commercial sex.22

Box 2.3: A New Look at the Economics of an Old Trade

Commercial sex exists in every region, and Asia is no exception. In most Asian countries, female sexuality is tightly controlled, with women expected to preserve their virginity until marriage. Conversely, young men are not expected to remain œlibate until married. Since the vast majority of women are not available for sex until marriage, an obvious supply/demand imbalance occurs.23'24^25

Historically, sex workers have addressed that imbalance. Thus, a small number of women perform sexual services for a much larger number of men. Epidemiologically, this increases the probability of HIV transmission. Once the virus is introduced into this network of people who buy and sell s,ex, infection levels can rise rapidly among women who sell sex to large numbers of men (who have a high 'client turnover'). Women infected with HIV transmit the virus to clients, who in turn transmit the virus back into the small but increasingly infected pool of sex workers.

In some quarters, preventing sex work has been seen as a politically appealing way to control HIV transmission. However, such an approach only tackles one part of the equation (supply) while leaving the other (demand) untouched. This is why some researchers argue that greater sexual freedom for women may reduce the demand for commercial sex and limit HIV transmission in Asia.26

Whether through peer education (as in the Sonagachi programme in India and the SHAKTI project in Bangladesh)27 or structural interventions targeting brothel managers (as in Cambodia and Thailand), increasing the rate of consistent condom use in sex work to more than 50 per cent can significantly reduce HIV transmission.28,29 In every setting with a flourishing sex trade, achieving and maintaining high levels of condom use in commercial sex will, more than any other intervention, prevent the greatest number of HIV infections in the society as a whole.

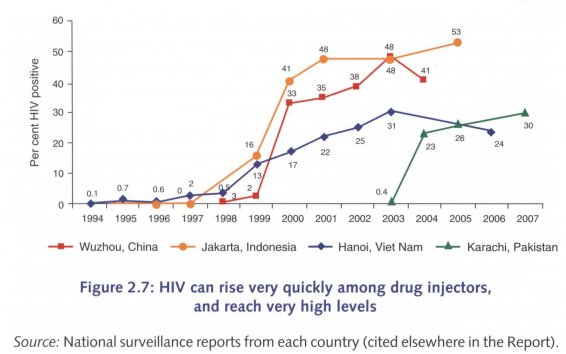

DRUG INJECTING SPREADS HIV RAPIDLY

Sharing syringes and needles when injecting drugs is the easiest way of HIV getting transmitted. As a result, HIV prevalence can increase very quickly among drug injectors.

Several countries and areas in Asia have seen HIV infection levels soar from zero to 40 per cent or higher in only a few years. In the Nepalese capital, Kathmandu, HIV prevalence was 68 per cent among injecting drug users in 2003, while in Viet Nam's northern port city of Hai Phong, 66 per cent tested HIV positive in 2006. In Lashio, close to Myanmar's border with China, 60 per cent of drug injectors were found to be infected in 2004. In Karachi (Pakistan), HIV prevalence among injecting drug users rose from under 1 per cent in early 2004 to 26 per cent in March 2005.3°

Unfortunately, HIV prevalence in drug injectors does not decline as swiftly as it rises. Once prevalence reaches high levels, it can take many years of intensive and wide-scale prevention efforts to bring infection rates down again. Success stories from industrialized countries show that it takes 7 to 10 years before a substantial drop in prevalence is observed.31,32

The most effective course of action is to prevent HIV infections among injectors before prevalence soars. In countries and regions where the opportunity still exists, early intervention will be far easier and cheaper than trying to curb rampant HIV spread among injectors and their sexual partners. In China, Hong Kong Speical Administrative Region (Hong Kong SAR) opted for this route, and its harm-reduction programme has helped keep HIV prevalence among drug injectors low for many years.33

Countries and areas where HIV prevalence among injectors is still relatively low (including Bangladesh, Pakistan, several cities in eastern China, and some in India and Malaysia) should therefore focus a very substantial part of their HIV prevention efforts on programmes that reduce drug injecting, that promote the use of sterile equipment when injecting does occur, and that encourage safe sex among injectors and their partners. This should be done immediately.

Several countries in Asia (for example, Bangladesh, China, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Nepal, and Viet Nam) have started programmes to provide sterile needles and methadone or other oral substitutes to heroin injectors. These are important steps forward. But most of these programmes are small and reach only a fraction of the people who require such services; limited coverage means limited impact on the HIV epidemic.

Only in parts of India and China (notably Hong Kong SAR) are HIV prevention programmes for drug injectors currently being implemented on a scale large enough to have an effect on HIV spread at the national level.

Preventing an HIV epidemic among drug injectors can be a very effective way of avoiding a wider HIV epidemic. First, it would prevent a critical mass of infection building up in the sex trade, and second, it would limit HIV being passed on to the non-commercial sex partners of drug injectors.

However, at the current stage of the epidemic, the option of preventing it among networks of drug injectors is no longer available; for example, in Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nepal, Thailand, Viet Nam, and parts of China and India. In those places, HIV prevalence among injecting drug users is already high, and a substantial proportion of new HIV infections are the result of the sharing of contaminated injecting equipment or unprotected sex with an infected injector.

...AND JUMP STARTS THE EPIDEMIC IN THE SEX TRADE

Injectors who buy sex

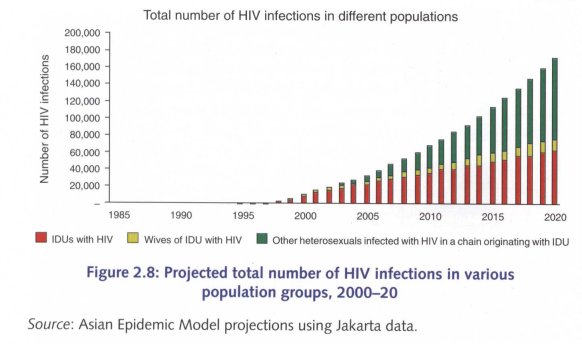

Infected drug injectors can introduce the virus into the sex trade in two ways: as buyers (male injectors buy sex from sex workers whom they infect), or as sellers (female drug injectors sell sex to male clients, whom they infect).

Reconstruction of the evolution of the HIV epidemic in Jakarta (Indonesia), shows that the roughly 40,000 people who inject heroin in that city can have a dramatic effect on the HIV epidemic, as illustrated in Figure 2.8 below. Over the course of 20 years (2000-2020), a failure to prevent HIV infections among drug injectors could lead to some 1.6 million people becoming infected with HIV, fewer than half of whom would be injecting drug users.

Injectors who Sell Sex

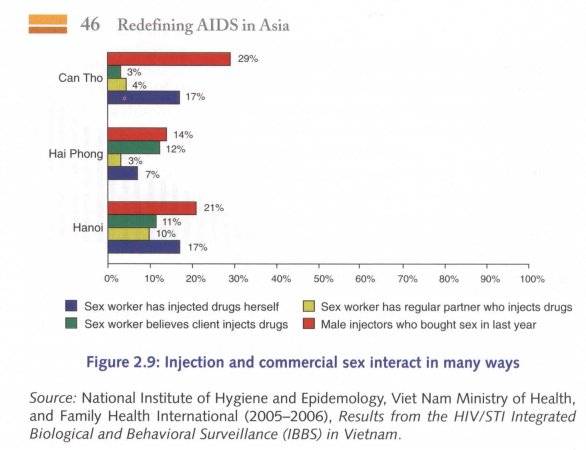

Drug injectors who finance their addiction by selling sex tend to have a high turnover of partners. Male injectors sometimes sell sex, but female injectors do so quite often. Studies in Viet Nam's Ho Chi Minh City have found that up to one quarter of the city's 12,000 or so street-based sexVorkers inject drugs. In Hanoi and Can Tho, about 17 per cent of sex workers said they injected drugs, according to a 2005/2006 survey. Sex workers who injected drugs were between 3.5 and 31 times more likely to be HIV-infected, compared with those who did not inject.34

In parts of China, almost half (47 per cent) of female injectors said they sold sex, and they were significantly less likely to use condoms with clients, compared with sex workers who did not inject. This information prompted HIV planners in southwest China to increase their focus on reaching female injectors with safe sex programmes, and with some success. In 2003, just 38 per cent of injecting sex workers said they had received free condoms in the previous year, compared with 53 per cent of non-injecting sex workers. By 2005, after outreach workers had focused on helping injectors adopt safer practices, 94 per cent of injecting sex workers were receiving free condoms. Consistent condom use with clients among injecting sex workers rose from 32 per cent in 2003 to 71 per cent in 2005.35

Box 2.4: HIV behind Prison Walls:

A Less Understood Epidemic

As in much of the rest of the world, narcotic use is illegal in Asia, and drug users are jailed frequently (not only for their drug-using habits but also for crimes committed to finance their addictions). Because sterile needles are not freely available in prisons, it is common to share injecting equipment. Close to 30 per cent of Indonesian injectors have spent time in jail, according to national surveillance findings, and a high proportion of them injected while behind bars.

In Thailand, drug injectors who had been jailed were seven times more likely to be HIV-infected than were injectors who had never been jailed.36,37 In Chennai (India), they were more than twice as likely to be infected compared with those who had never been to jail.38 And in Indonesia, men who had recently arrived in jail were only a quarMr as likely to be HIV-infected compared with other prisoners.39 According to public health officials, drug-injecting while in jail probably accounts for most of those discrepancies. In Thailand, one in six current injectors said the first time they injected drugs was in jail.40

The risks do not end there. People who are newly infected in jail are highly infectious. If they then have unprotected sex with other inmates who are not injectors, they am much more likely to transmit HIV. And those who are in jail for a short period of time may well be released while they are still highly infectious. Their sex partners outside the prison system are then at high risk for HIV infection. Jails can act as reservoirs for HIV.

Effective prevention programmes inside prisons can help limit HIV spread. Logistically, prisons are among the easiest places to mount HIV prevention programmes. The only real obstacle is political and it can easily be overcome. Several countries have introduced prevention programmes in prisons (including the provision of sterilized injecting equipment); these include Australia, Iran, Kyrgyzstan, and many countries in Europe. In Germany, for example, new infections in prison fell to zero after sterile needles were made easily available to inmates.41,42,43,44,45

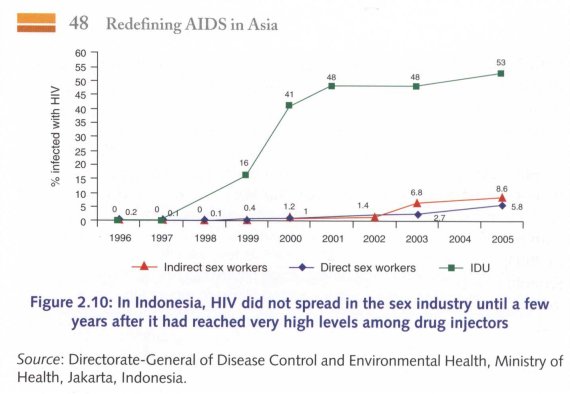

The lesson is clear. When infected drug injectors are also involved in commercial sex trade (as buyers or sellers), HIV epidemics can occur very quickly. If condom use is low—as in Indonesia—high HIV infection levels among drug injectors can start an epidemic which then spreads to commercial sex networks (see Figure 2.10). But if condom use is already high when infected drug injectors buy or sell sex (as in Thailand), HIV will not spread as widely and as quickly into commercial sex networks, even if HIV prevalence among injecting drug users is high.

SEX BETWEEN MEN: A FAST GROWING EPIDEMIC

Although there is an emerging gay scene in some cities, same-sex monogamy remains relatively rare in Asia. Social taboos and discrimination means that many men who have sex with men still disguise their sexual preference by also having sex with women (in marriage or otherwise).46

Men with many partners are more likely to encounter a newly-infected partner and become infected, and they are also more likely to spread the virus to a large number of other people. In a study in Bangkok in 2004, HIV-negative men reported anal sex with an average of 41 men in their lives, while HIV-positive men averaged 54 life-time partners.47 In Ho Chi Minh City, some 8 per cent of men who had sex with other men said they had had anal sex with three or more consensual partners in the previous month.48 Partner turnover in Phnom Penh was higher, with 21 per cent of the men saying they had sex with six or more partners in the previous month (and almost half of those men exchanged sex for money at least once in the previous week).49

Such high partner turnover, combined with low condom use, has led to a rapid rise in HIV prevalence among men who have sex with men in several Asian cities. In Bangkok, more than one in four (28 per cent) men who have sex with men were found to be infected with HIV in a 2005 study, up from 17 per cent in 2003.5° In the Chinese capital, Beijing, fewer than 1 per cent of surveyed men who have sex with men were HIV-positive in 2004; two years later, prevalence had reached almost 6 per cent. In Karachi (Pakistan), 4 per cent of surveyed male sex workers were found to be infected in 2005; within two years, that figure had nearly doubled.51 Among transgender sex workers, HIV infection levels were higher: 22 per cent in Jakarta in 2002 and 37 per cent in Phnom Penh in 2003.52

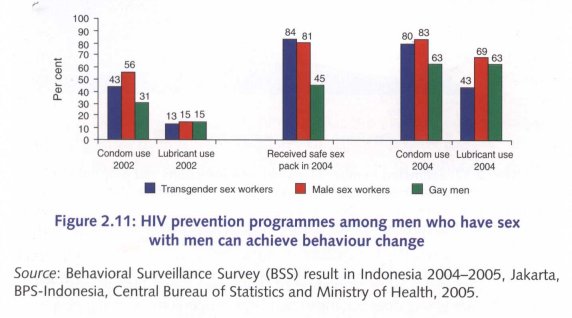

When HIV prevention services have been provided in Asia to men who have sex with men, uptake of those services tends to be impressive. In Indonesia, the Health Ministry collaborated with non-governmental partners to produce and promote safe sex packs, including condoms, water-based lubricant, and information about HIV and sexually transmitted infections. Figure 211 shows levels of condom and lubricant use before and after the prevention. programmes started. Clearly, high coverage of a service that men appreciate can translate into rapid behaviour change.

Community groups of men who have sex with men have proved to be energetic and competent partners (and leaders) in HIV prevention in many settings. This can keep costs down, while ensuring high programme coverage.

Box 2.5: Is Casual Sex among Young People Driving Asia's HIV Epidemics?

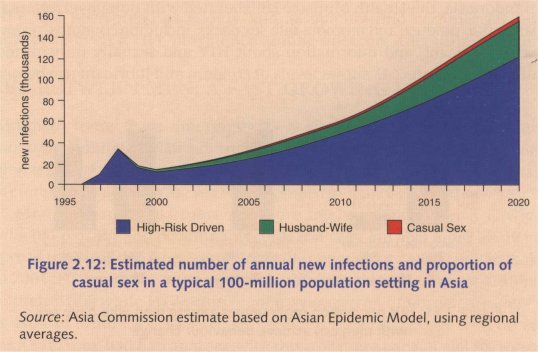

Socio-cultural restrictions on women's sexual freedom are one of the reasons why casual sex remains a minor factor in Asia's HIV epidemics at the moment. But even increases in unprotected casual sex are unlikely to lead to larger HIV epidemics in the foreseeable future, as Figure 2.12 shows. Yet, in several Asian countries, significant resources are invested in trying to discourage unsafe casual sex among young people.

The fact that a large proportion of those who are at high risk of HIV infection are young does not mean that large proportions of young people are at high risk of HIV. In every country in Asia, at least 98 per cent of young women and 90 per cent of men—and usually far more—neither sell nor buy sex or inject drugs. They are therefore not at high risk of HIV infection.

THE BEST WAY TO PROTECT WOMEN IN ASIA IS TO PREVENT THEIR HUSBANDS FROM BECOMING INFECTED

Although three out of four adults living with HIV in Asia are men, the proportion of women in this total has risen gradually—from 19 per cent in 2000 to 24 per cent in 2007.53

Those women will have been infected in one of three ways. A very small minority will have acquired HIV while injecting drugs, some will have been infected when selling sex, and most will have been exposed to HIV during sex with a husband or boyfriend who had been infected during paid sex or when injecting drugs. As a conservative estimate, the number of women at risk of falling into the latter category could number more than 50 million in Asia.54

Clearly, therefore, the best way to prevent most HIV infections in women, therefore, is to prevent their husbands from becoming infected in the first place. And the most effective way of achieving that is to prevent infections during paid sex and drug injecting. Unfortunately, public programmes aiming to do that have been too few. As a consequence, large numbers of men in Asia are infected with HIV, and they are putting their regular sexual partners at risk. Typically, those partners are unaware of that risk and are not able to protect themselves against infection.

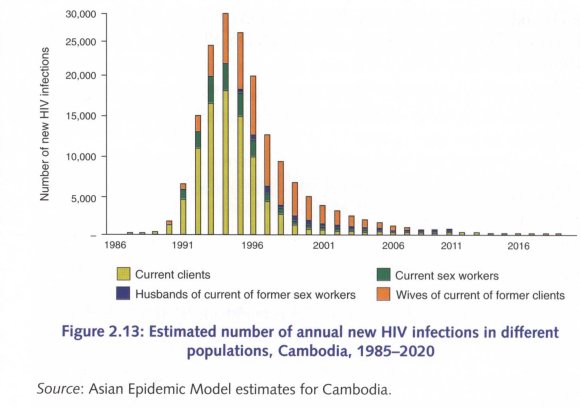

'Note, though, that even when countries reduce HIV transmission in the sex industry or among drug injectors, there will remain a phase in which most new infections will occur in women who have unprotected sex with their infected husbands. Cambodia is now in such a phase, as Figure 2.13 shows. This does not mean that the epidemic now sustains itself independent of the sex industry or injecting drug use.

An estimated one-third of all new infections in Cambodia in 2007 (up from 13 per cent in 1992) will have been among women who are not sex workers. But the absolute number of new infections in women infected by their husbands is much smaller compared with the period when the epidemic peaked: only an estimated 330 women will have been infected by their husbands in 2007, compared with more than 7,500 in 1996.55 If sustained, effective programmes to curb HIV transmission in commercial sex, drug injection, and male-male sex are established, countries will see a steady decrease in spousal transmission and become a minor factor in. an overall epidemic that also declines.

CLASSIFYING ASIA'S EPIDEMICS TO TAILOR EFFECTIVE RESPONSES

HIV can only spread through society independently of commercial sex, drug injection, and sex between men if the immediate sexual partners of people at high risk of infection also have unprotected sex with several other people in a short space of time.

Such epidemics are now commonplace in East and southern Africa, and in parts of West and Central Africa. They have been termed 'generalized epidemics', and a numerical threshold is usually attached to that term: once HIV prevalence among pregnant women in urban areas exceeds 1 per cent, countries are deemed to be experiencing a 'generalized epidemic'.

It is usually assumed that in such epidemics, prevention efforts have to reach the entire sexually active population, and emphasis is often placed on reaching young people with those interventions. But this categorization may not be appropriate everywhere.

Nowhere in Asia (nor anywhere in Europe or the Americas) has HIV spread through societies independently of drug injecting, sex between men and/or commercial sex. 'Generalized epidemics' require a high prevalence of multiple, concurrent sexual partnerships among both men and women—and these patterns are very rare in Asia.

So, the standard classification of 'low-level', 'concentrated' or 'generalized', based on the HIV prevalence in pregnant women, does not capture the actual nature and dynamics of Asia's epidemics.

The 'low-level' label disguises a rising trend in HIV infections in places where interventions are not in place, and can lead to complacency.

The 'concentrated' epidemic implies equal weight to all populations—whether they are migrants, sex workers, or injecting drug users — whereas in Asia, the early prioritization of prevention for injecting drug users in many settings can make a significant difference to the outcome of the epidemic.

The 'generalized' epidemic label has led some countries in Asia to shift mistakenly from focused prevention interventions to generalized awareness campaigns for their entire populations.56,57

The Commission proposes that Asia's epidemics can be better understood if they are classified according to the predominant risk behaviours and their relative contribution to new infections, rather than according to national HIV prevalence. Such a scheme offers broad guidance that can assist countries and donors in selecting and prioritizing their HIV interventions more appropriately. The Commission recommends that UNAIDS and WHO further develop and validate this scheme.

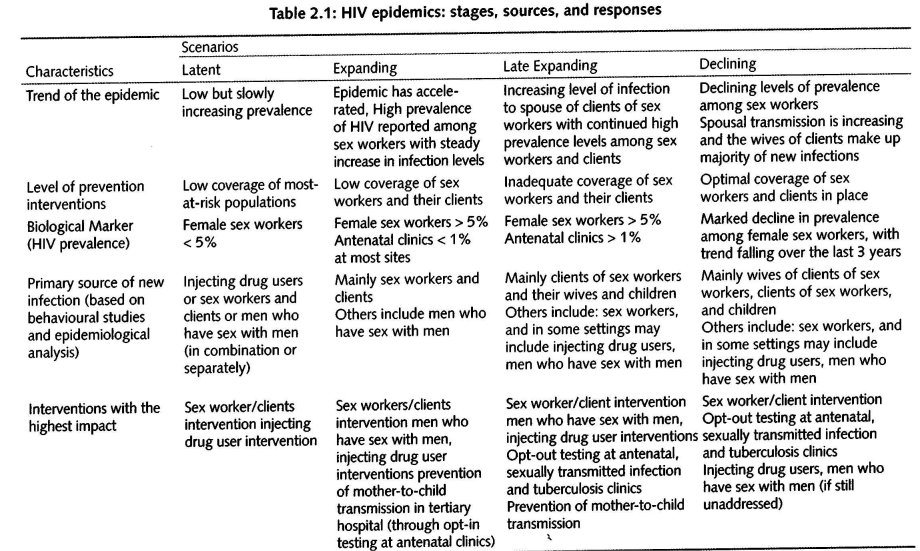

The Commission proposes four epidemic scenarios or categories for Asia, namely: Latent, Expanding, Mature, and Declining (see Table 2.1 and the rIbchnical Note at the end of this Chapter). Countries should themselves assess into which categories their epidemics fit, guided by using characteristics such as those listed in Table 2.1 . In the case of large and populous countries, the epidemic might match more than one category.

Table 2.1 shows how the various scenarios can be matched against HIV and behavioural information to indicate the most appropriate package of interventions. Note, however, that HIV epidemics are dynamic and require regular assessment. A robust system on strategic information and surveillance is therefore an essential prerequisite for a successful response, which is discussed later in the chapter.

Box 2.6: The Current Course of HIV in Asia:

A History of Successes and Failures

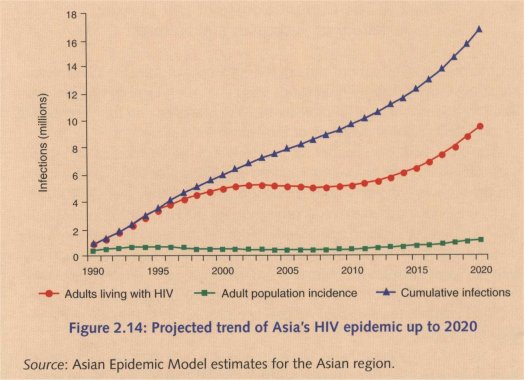

In order to assess the current state of the epidemics of Asia, the Commission prepared a set of country projections using the Asian Epidemic Model (see Box 2.2). Individual country projections were prepared and then combined to produce a regional overview of the epidemics' course.

The projections assume that the prevalence of key behaviours that shape Asia's epidemics (such as levels of condom use during paid sex, clierit turnover, and the numbers of men who buy sex) will remain as they were in 2007.58

Figure 2.14 shows the overall projection for the HIV epidemic in Asia. In 2007, just over 5.1 million adults and children in the region were living with HIV and 375, 000 people were newly-infected. These figures agree closely with the latest UNAIDS estimate that 4.8 million people in Asia where living with HIV in 2007. More than 2.6 million men, 900,000 women and over 300,000 children have died of AIDS-related causes in the region since the epidemic began.

Cambodia, Myanmar, and Thailand and the high-prevalence states of India dominated the first decade of the Asian HIV pandemic. However, in these places, the sex work components of the epidemics were brought under control, and HIV prevalence has now started to decline. Despite those achievements, however, these high-prevalence areas are experiencing substantial ongoing HIV transmission among men who have sex with men 4nd injecting drug users. But the combined effect of measures to combat risks in the sex trade in these epidemics has resulted in a slowdown in the rate of growth of the regional epidemic, starting in the early-2000s.

The future of Asia's epidemics will be decided mainly by developments in the epidemics of countries which are today experiencing relatively steady growth in new HIV infections. That group includes some of the world's most populous countries: Bangladesh, China, Indonesia, and Pakistan. Their epidemics are likely to dominate the next phase of the regional pandemic.

Figure 2.14 depicts the resultant, post-2010 upswing in the regional pandemic we can anticipate. After a period in the mid-2000s, when nevv infections declined slightly, the Asian HIV pandemic is now entering a secondary growth phase, which may push HIV prevalence to almost 10 million by 2020 in the absence of expanded prevention efforts.

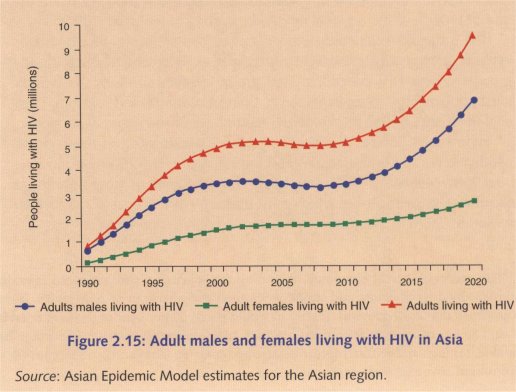

As Figure 2.15 shows, males continue to dominate the epidemics, with about two males infected with HIV for every female who acquires the virus. This trend is likely to continue into the future. By the late 2010s, the male—female ratio will start to rise somewhat as the epidemics among men having sex with men and injecting drug users assume a larger role in the epidemic.

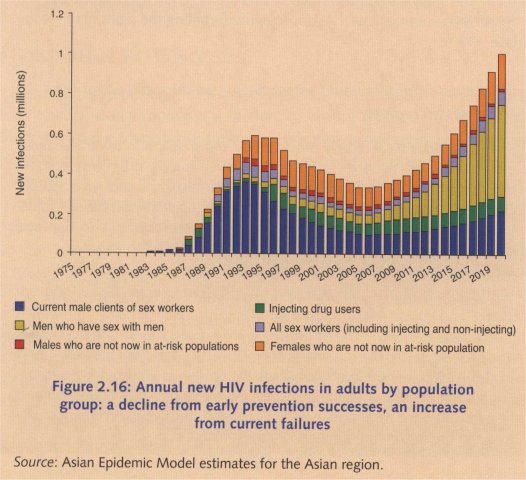

If one looks at the pattern of new HIV infections in various population groups (Figure 2.16), one sees a dynamic and evolving regional pandemic. New infections in Asia peaked at over 600, 000 in the mid-1990s, but effective condom promotion for sex workers and clients subsequently reversed that trend. New infections have continued to decline as condom use has increased also in other countries.

At the same time, low coverage of HIV interventions has meant that infections are not being prevented as effectively in other groups, such as injecting drug users, men who have sex with men, and the wives of sex work clients or other higher risk men. Consequently, their relative contribution to the total number of new infections is increasing, even as the overall numbers decline. Note, however, that this decline is coming to an end. Unless further prevention success is achieved, it is likely that new HIV infections will rise again as the number of sex work clients increases, transmission among drug injection continues, the epidemic among men who have sex with men grows, and infected men continue to transmit the virus to their wives and girlfriends.

WHAT CAN 'WE LEARN FROM THESE PROJECTIONS?

The region must address all aspects of the epidemic

Regionally in 2007, as Figure 2.16 shows, all the population groups were contributing substantially to new HIV infections--whether sex workers and clients, husbands and wives, injecting drug users or men who have sex with men. This means that prevention efforts are urgently needed and needed for all those populations if Asia is to avoid forfeiting the gains made in the late-1990s.

Individual countries should assess their epidemics and adapt their responses accordingly

Some countries have largely brought HIV transmission in sex trade under control, but still need to tackle transmission among drug injectors and men who have sex with men, and between husbands and wives. Other countries have not yet made inroads into their epidemics in the sex trade. Whatever the case, countries need to tailor their responses to the local epidemiological situation.

The lull after the first phase in the pandemic's evolu ion is ending, and a new wave of infections seems imminent

The projections depict a regional success story that lasts from the early 1990s to about 2005 in those countries where the epidemics grew quickly early on. But we run the risk of seeing those achievements fade. Complacency must be overcome, and resources should be targeted effectively and appropriately to avoid the maximum numbers of new infections.

MIGHT CHANGES IN SEXUAL BEHAVIOUR ALTER THE COURSE OF THE EPIDEMICS?

Many Asian economies are booming. Between 1985 and 2005, per capita gross domestic product in Asia tripled in real terms. Per capita income in China, for example, rose five-fold over the period, while in India it increased by 126 per cent and in Viet Nam by 166 per cent.59 However, although overall wealth is increasing in much of Asia, poverty is not being reduced at the same pace. As a result, income and other inequalities (for example, in access to certain services and resources) are growing in several countries.

It is impossible to say exactly how economic and social changes will affect HIV epidemics in Asia. But one way of approaching the question is by exploring possible changes in two of the factors that currently define the epidemics: the number of men who buy sex, and the sexual networking patterns of women.

MORE MEN BUYING SEX?

The future of Asia's epidemics depends to a considerable extent on what happens to men's incomes and their mobility outside family settings. Men who have disposable income, and who travel or migrate to work opportunities, provide most of the demand for commercial sex.6° If countries in Asia continue to experience rapid economic growth and men's incomes continue to rise, the demand for commercial sex in the region is also likely to rise.

A surge in new HIV infections in the sex trade is most likely if the pool of male clients expands faster than the pool of women selling sex. If the pool of sex work clients increases but the numbers of female sex workers stay unchanged, then the average sex worker will have more clierits. As a result, client turnover will increase. In such a scenario, HIV prevalence will probably also increase. A similar trend is likely if the numbers of male clients remain steady but fewer women sell sex. In that case, client turnover will also increase and so will HIV prevalence.

In all such scenarios, the future of Asia's epidemics still depends on whether opportunities for HIV transmission during paid sex canbe reduced.

VVILL CASUAL AND PREMARITAL SEX LEAD TO A RISE IN HIV EPIDEMICS?

Current patterns of sexual networking in Asia do not support high-prevalence HIV epidemics independent of the sex trade and drug injecting. But economic changes lead to changes in social relations. As economies develop, women gain greater access to education and employment opportunities and assert their rights more effectively. It is sometimes argued that improved educational and career opportunities for women lead to a relaxation in the socio-cultural restraints placed on women's sexual freedom. Internationally one typical outcome is a rise in the age of marriage, which tends to correspond with more premarital sex.61 Will such a shift in Asia lead to a rise in HIV epidemics?

In Asia's richest countries, sexual behaviour among young people now mirrors that in Western countries. In a national survey conducted in Japan in 1999, only about 5 per cent of women in their 40s and early 50s had had sex with five or more men in their lifetimes. But about 40 per cent of young women aged 18-24 years had already had five or more sexual partners in total, and about the same percentage of young women said they had sex with two or more men in the previous year.62 A similar, though somewhat less pronounced trend, was observed in rural areas. According to a study among university students, condom use with regular partners was high (about 70 per cent), but it was much lower with casual partners (around 50 per cent).

Yet such high levels of sexual activity and modest levels of condom use have not led to an HIV epidemic among young heterosexuals in Japan, any more than they have in. Europe or the Americas. A large part of the reason could be that where men have more opportunities for casual sex, they are less likely to visit sex workers.63

This suggests that in most Asian countries an increase in casual and premarital sex among women in itself is unlikely to lead to a net increase in new HIV infections because there probably will be a corresponding reduction in commercial sex, which is one of the main drivers of the epidemic.

None of this warrants complacency. An increase in casual sex heralds other challenges and risks, even if it is unlikely to trigger larger HIV epidemics in Asia. Young people will need information about how to avoid unwanted pregnancies and how to protect them and their partners against sexually transmitted infections, including HIV They will need sex education and services to help them lead healthy sex lives. In both scenarios, women's sexual behaviour is a key variable that will shape the future of HIV in Asia.

SOLID DATA AND ANALYSIS IS NEEDED TO UNDERSTAND AND RESPOND TO THE EPIDEMIC

Having reliable HIV data is a precondition for gaining a solid understanding of the epidemic but rigorous analysis is required to develop that understanding. Unfortunately, on this front—the careful scrutiny and analysis of data—many countries in Asia still fall short.

The reason for this is largely institutional. The task of collecting, assessing, and analysing data from dozens of sources is best-performed in a centralized manner. Yet this time-consuming, critically important work is seldom entrusted to a single structure or unit.

Instead, various data sets tend to 'float' about in. the public health system in different state institutions, non-governmental organizations and donor agencies. District health offices often do not share their surveillance data with the national health ministry. People collecting behavioural data in one donor-funded project tend to be reluctant (or unable) to share the information with someone who is funded by a different donor.

Sometimes, national Governments are reluctant to grant international organizations or academic bodies access to data they consider sensitive (and it is typical to regard HIV surveillance data as sensitive). It is not unusual for those same Governments to then dismiss data collected by universities or international partners on the pretext that they did not collaborate with the national health system.

A further layer of complexity (and sensitivity) is added when programme data are included in the analysis. Obviously, before deciding how best to allocate programme resources, it seems prudent to conduct an assessment of which prevention services are available where, how many people have access to them at what levels of coverage, and what demonstrable effects they are having. But information on service delivery is rarely shared between service providers (whether non-governmental or state), between donors, or by Governments. Attempts to rectify this state of affairs (such as the UNAIDS-backed Country Response Information Service) are often seen as externally driven and of limited relevance to national needs, and service providers therefore have little incentive to contribute information to those systems.

IMPROVING THE ANALYSIS OF HW DATA REQUIRES RESOURCES AND TIME

All countries can achieve a robust analysis of HIV-related data (including information on HIV, sexually transmitted infections, risk behaviours, risk population sizes, and service delivery), and they can do so with relative ease.

What is required is an understanding of the epidemiology of HIV and sexually transmitted infections, a critical appraisal of the quality of data, solid computing skills, and curious minds. Furthermore, it is essential that somebody—an institution or structure—takes responsibility for coordinating this effort, and acquires the resources and the time to do it properly. Solid, trustworthy analysis of the data takes time.

This is why Governments should put in place institutional and budgetary mechanisms to create permanent posts for senior-level analysts with the authority to access all available information and the mandate to gather it into a single system for analysis and to provide relevant policy analyses to key decision makers so they can make the right choices.

All this is readily achievable, but it makes the challenge a little tougher to meet. Just as good data do not translate automatically into strong analysis, good analysis does not translate automatically into good policy or effective service provision. A range of factors (institutional, political, financial, practical, ideological, and socio-cultural) shape those outcomes. Chapter 4 discusses some of the contextual factors that need to be addressed in order to achieve an effective response to HIV, while Chapter 5 examines some of the financial issues.

Box 2.7: Are Current Surveillance Systems

Overestimating HIV in Asia?

Recent population based surveys of HIV in Cambodia and India have led to lovver estimates of the numbers of people living with HIV in those countries.

In the case of India, the new estimate is dramatically lower than before: 2.5 million (2 million-3.1 million) adults in India were believed to be living with HIV in 2006, cornpared with the 5.2 million (3.1 million-8.7 million) estimated in 2005.64,65

Earlier estimates of the number of people living with HIV had been based mainly on data collected at public clinics where pregnant women receive antenatal care. Most of those clinics are in urban or peri-urban areas. But a survey of 100,000 households in 2006 showed that antenatal clinic data tended to overestimate prevalence among women (possibly because a higher proportion of women who are more likely to be infected with HIV use public rattler than private facilities). India's national estimates were revised downwanis to reflect this information, and are now in line with earlier population-based HIV data which had suggested that state-level and national prevalence estimates based on sentinel surveillance might have been overestimated .66

In Cambodia, a 2005 household HIV survey showed that HIV prevalence among women was more than three times higher in urban than in rural areas. HIV estimates based largely on urban sites therefore would have overestimated national prevalence. Cambodia's HIV estimates have been adjusted accordingly and are now more accurate than before.

In Ho Chi Minh City (Viet Nam), the discrepancy between HIV prevalence estimates based on epidemiological models and those based on a national household HIV survey turned out to be smaller. This was mainly because the household survey data did not include those drug injectors and sex workers interned in 're-education' camps (among whom HIV prevalence tends to be very high).

Household HIV surveys have undoubtedly improved our knowledge about absolute levels of HIV in the population, but they are time-consuming and expensive. And their samples do not necessarily include populations that are most-at-risk of HIV infection. Planners in Asia need to weigh the additional benefits of gathering data in this manner against their costs and lirnitations.

Where surveillance systems show that HIV prevalence and risk behaviours are high among particular populations, the priority must always be to ensure that the people affected have access to effective prevention and treatment services. In terms of preventing HIV infections, such an approach is more valuable than arriving at a perfect count of the total number of infections nationwide.

Box 2.8: Improving Understanding of Asia's

HIV Epidemics by Addressing Data Needs

On the whole, Asia probably leads the world in gathering reliable information about the prevalence of HIV and risk behaviours in some of the groups most likely to be exposed to the virus (especially among sex workers). Many countries also collect valuable behavioural information on clients of sex workers (though fewer have HIV prevalence information for clients). A growing number of Asian countries have also adapted their national surveillance systems to gather information on risk behaviour among drug injectors. Generally, though, men who have sex with men remain neglected in terms of both HIV and behavioural surveillance.

There are other gaps, too. Assume that HIV prevalence in Group A is 40 per cent, but only 0.01 per cent of the population belongs to Group A and those persons are unlikely to transmit the virus persons outside that. group. Group A probably will not contribute significantly to the HIV epidemic. But at the turn of this century, no country in Asia had well-documented, data-based estimates of the numbers of people who engage in particular high-risk behaviours. Fortunately, the situation has improved subsequently. Such estimates now exist in many countries, and they are constantly being refined.

Public health surveillance is a core function of national Governments. Yet, legislation and budgeting do not always reflect its importance, especially in countries that are undergoing rapid market transition. In many places, this has disrupted public health data systems, and it is compromising those countries' capacity to understand and respond appropriately to public health crises such as AIDS.

Data collected at district or provincial levels are not always passed on to the national level for analysis. And national HIV prevention policies are not always enforced at provincial or district levels which, increasingly, control decisions about which services will be funded, and how public employees use their time.

HIV surveillance is often institutionally and geographically fragmented. Health ministries usually set up HIV surveillance systems, but the work is often done by other institutions (many of them outside Government). In addition, many international donors fund data collection processes that occur entirely outside of Government systems. Those data, although potentially valuable, then tend to be under-utilized in the analysis of national trends, and prevention and care needs.

TECHNICAL NOTE: FOUR SCENARIOS FOR PRIORITIZING INTERVENTIONS

Latent epidemic

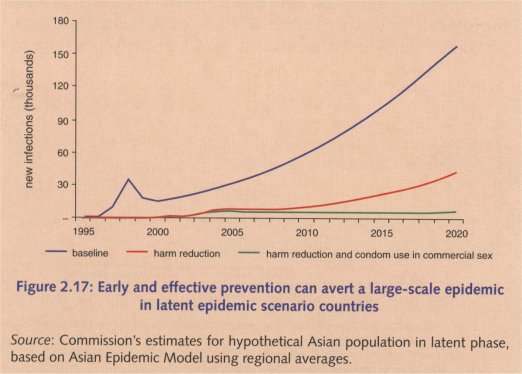

In this phase, HIV prevalence is still very low. Early and effective action on prevention will avert a large-scale epidemic.

Trend: HIV prevalence is very low among the adult population, and few if any prevention programmes are in place.

Biological indicator: In the absence of prevention efforts, prevalence of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections among female sex workers is below 5 per cent.

Source of new infections: Most new infections are among injecting drug users and men who have sex with men. Female sex workers account for a smaller number of new infections.

Most effective package: Without expanded prevention programmes, the epidemic will grow as shown by the blue line. If a high-coverage, focused, and successful harm reduction package for injecting drug users is put into place, the epidemic in the sex trade will be delayed, leading to an epidemic that starts to grow several years later (red line). If programmes also achieve consistent condom use in the sex trade, then the epidemic can be averted almost entirely (green line). If men having sex with men are contributing substantial numbers of new infections in a country, programmes should be expanded to include them.

Expanding epidemic

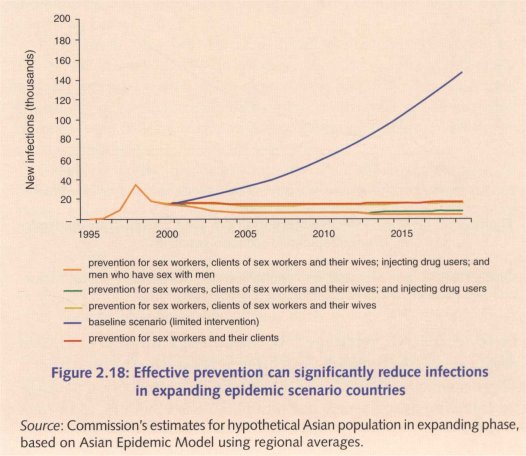

HIV prevalence is still relatively low but growing. Without immediate and effective prevention, the epidemic is likely to grow to significant levels.

Trend: HIV prevalence is low among the adult population but has already started rising among sex workers and their clients. Prevention programmes are either absent or inadequate.

Biological indicator: In the absence of prevention efforts,prevalence of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections among female sex workers is above 5 per cent, while HIV measured in antenatal clinics remains low (under 1 per cent).

Source of new infections: Most new infections are among female sex workers and their clients. The overall benefit of early harm reduction intervention is reduced in this phase because infections in injecting drug users (and men who have sex with men in most settings) likely account for a smaller number of new infections.

Most effective package: Without expanded prevention programs, the epidemic will grow as shown by the blue line. If a sex trade package achieves consistent condom use, the number of new infections will drop greatly (red line). Adding a package to prevent husband-to-wife transmission will further reduce infections (yellow line). Further addition of a harm reduction package for drug users (green line), and risk reduction package among men who have sex with men (orange line) will bring the epidemic to 'extremely low levels.

Maturing epidemic

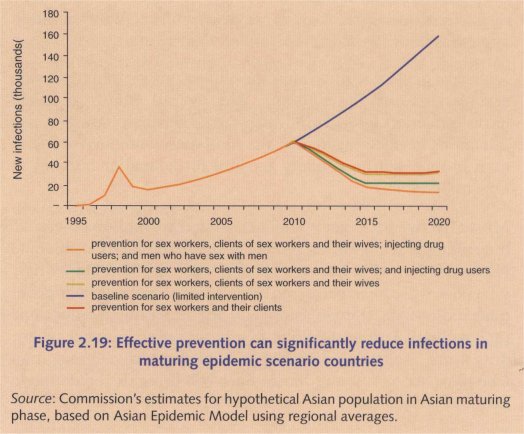

In this phase, HIV prevalence has been rising for several years, and HIV is spreading in the general population (mainly to sex work clients and their wives).

Trend: HIV prevalence is increasing in the adult population and is high in specific sub-populations, but few if any prevention programmes are in plac,e.

Biological indicator: In the absence of prevention efforts, prevalence of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections among female sex workers is above 5 per cent and HIV measured in antenatal clinics is relatively high, exceeding 1 per cent.

Source of new infections: Most new infections will be among clients of sex workers and the wives of those men, while new infections in sex workers, injecting drug users and men who have sex with men will likely account for a smaller but still significant number of new infections.

Most effective package: The most effective package here will be similar to that in the Expanding phase. Without expanded prevention programmes, the epidemic will grow as shown by the blue line. If a sex trade package achieves consistent condom use, the number of new infections will drop greatly (red line). Adding a package to prevent husband-to-wife transmission will further reduce infections (yellow line). Further addition of a harm reduction package for drug users (green line), and risk reduction package among men who have sex with men (orange line) will bring the epidemic to extremely low levels.

Declining epidemic

Effective condom-use programmes have curbed the sex trade epidemic, but sex work clients who were infected earlier are still transmitting HIV to their wives. Programmes for injecting drug users and men having sex with men remain at the pilot level (for example, this is the situation in Thailand today).

Trend: HIV prevalence is falling as a result of successful sex worker and client prevention programmes, but new infections will soon rise again as a major epidemic among men having sex with men takes hold.

Biological indicator: With successful condom use programmes, prevalence of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections among female sex workers may still exceed 5 per cent, but there will be a declining trend.

Source of new infections: Many new infections will be among the wives of clients of sex workers, injecting drug users will provide a steady source of new infections, and the contribution of men who have sex with men will be growing rapidly. Female sex workers and their clients will account for a smaller number of new infections because of the effectiveness of programmes.

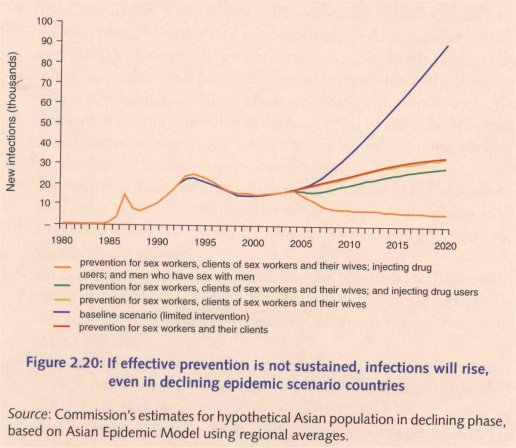

Most effective package: If the package does not sustain high levels of consistent condom use in the sex trade, prevalence will rise rapidly again (blue line) rather than rising more gradually due to the growing epidemics among men having sex with men and injecting drug users (red line). Adding a package for prevention of husband-to-wife transmission by expanding mother-to-child transmission programmes and voluntary counselling and testing will reduce infections a little (yellow line). Adding harm reduction for drug users will reduce new HIV infections by a steady amount (green line). However, the addition of a package for men having sex with men will produce the largest reduction in new infections in this phase if sex trade successes are maintained (orange line).

1 UNAIDS/WHO (2007), 2007 AIDS Epidemic Update, Geneva: UNAIDS.

2 Estimations and calculations of death and morbidity due to AIDS for Asia are detailed in the Tbchnical Annex.

3 Estimations and calculations of death and morbidity for other diseases are based on C. Mathers and D. Loncar (2006), 'Projections of Global Mortality and Burden of Disease from 2002 to 2030', PLoS Medicine, 3 (11), pp. 2011-30. Country figures made available by Mathers and Loncar.

4The Commission estimates that these high-risk behaviours account for 75 per cent or more new infections in the region.

5 The Commission's research and projections (using the Asia Epidemic Model) show that had there been no change in condom use and the number of men visiting sex workers in Thailand and Cambodia, national HIV prevalence could have reached as high as 8-10 per cent by 2007.

6 The partially protective role of circumcision has been factored into these calculations. However, in the current context of Asia, the Commission does not consider circumcision to be a priority prevention measure when projecting the likely outcomes of comprehensive intervention scenarios.

7 For more details, please refer to the 'Technical Annex.

8 R.R. Gangakhedkar, et al. (1998), 'Spread of HIV infection in married monogamous women in India', Journal of the American Medical Association, 278 (23), pp. 2090-2.

9 The possibility of under-reporting of self-reported sexual behaviour of women across major parts of the world does not change the main conclusion.

10 M. Carael (1995), Chapter 4, 'Sexual Behaviour', in J. Cleland and B. Ferry (eds), Sexual Behaviour and AIDS in the Developing World, London: Taylor & Francis.

11 The estimate is derived from a synthesis of estimated population size of different most-at-risk population groups in the countries of the region. References for the data sources are available in the rIèchnical Annex.

12 F. Lu, et al. (2006), 'Estimating the number of people at risk for and living with HIV in China in 2005: methods and results', Sexually Transmitted infections, 82 (supplement 3), pp. iii 87-iii 91.

13 India estimates are compiled from several sources, including detailed mapping and estimations provided by the Avahan project.

14 Behavioral Surveillance Survey (BSS) result in Indonesia 2004-5, Jakarta, BPS-Indonesia, Central Bureau of Statistics and Ministry of Health, 2005.

15 Estimates are derived from a synthesis of estimated sizes of various most-at-risk groups in the countries of the region. References for the data sources are available in the lbchnical Annex.

16 UNDP (2004), Thailand's Response to HIV/AIDS: Progress and Challenges, Bangkok: UNDP.

17 The period during which HIV infectivity is highest is relatively brief, but recently infected sex workers will expose many more men to HIV during that period if their client turnover is high. Tb illustrate this, compare a sex worker in Mumbai (average 12 clients per week in 2006, down from 20 a few years earlier) with one in Manila (average 2 clients per week). If we assume that the period of high infectivity lasts about three months, then the Indian sex worker will expose 144 men to a very high risk of HIV if condoms are not used, while the Filipina sex worker will expose only 24 clients. Indeed, HIV prevalence among sex workers in Mumbai rose from zero in 1987 to above 50 per cent just six years later. Among sex workers in Manila, HIV prevalence did not exceed 1 per cent. Early in Thailand and Cambodia's epidemics, when client turnover levels were similar to those in Mumbai, HIV also rose very quickly among sex workers—more than one-third of whom were infected in several cities.

18 Behavioral Surveillance Survey (BSS) result in Indonesia 2004-5, Jakarta, BPS-Indonesia, Central Bureau of Statistics and Ministry of Health, 2005; National Institute of Hygiene and Epidemiology, Viet Nam Ministry of Health, and Family Health International (2005-6), Results from the HIV/ STS Integrated Biological and Behavioral Surveillance (IBBS)in Vietnam; China data obtained by E. Pisani, coutesy of the China UK HIV/AIDS Prevention and Care Programme, 2007.

19 K. Nelson and D. Celentano (1996), 'Decline in HIV infections in Thailand', New England fountal of Medicine, 335 (26), pp. 1998-9.

20 Bureau of Epidemiology, Department of Disease Control, Ministry of Public Health, Thailand, HIV Serosurveillance in Thailand: Result of the 6 and 17 Rounds, 1991 and 1999, Bangkok.

21 Cambodian national surveillance data (2005) (National Center for HIV/AIDS Dermatology and STDs Cambodia 2006).

22 Indian Council of Medical Research and Family Health International 2007; AIDS Prevention and Control Project (2006).

23M. VanLandingham, et al. (1995), 'Friends, wives and extramarital sex in Thailand: A qualitative study of peer and spousal influence on Thai male extramarital sexual behaviour and attitudes', available at: 970.

24 J.M. Knodel, et al. (1996a), Sexuality, sexual experience and the good spouse: views of married Thai men and women, Chiang Mai: Silkworm.

25 J.M. Knodel, et al. (1996b), 'Thai views of sexuality and sexual behaviour', Health 'flansition Review, 6, pp. 179-201.

26 M. Kremer and C. Morcom (1998), 'The effect of changing sexual activity on HIV prevalence', Mathematical Biosciences, 151 (1), pp. 99-122.

27 Further details on these programmes are provided in Chapter 5.

28 S. Jana and B. Banerjee (eds) (1997), A dream, a pledge, a fulfilment: Five years' stint of STD/HIV intervention programme at Sonagachi, Calcutta: All India Institute of Hygiene & Public Health.

29 L. Guinness, et al. (2005), 'Does scale matter? The costs of HIV-prevention interventions for commercial sex workers in India', Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 83 (10), pp. 747-55.

30 National Centre for AIDS and STD Control, Ministry of Health, and Family Health International (2004). National Estimates of Adult HIV Infections: Nepal; National Institute of Hygiene and Epidemiology, Viet Nam Ministry of Health, and Family Health International (2005-2006). Results from the HIV/ STI Integrated Biological and Behavioral Surveillance (IBBS) in Vietnam; Data obtained by E. Pisani, courtesy of the China UK HIV/AIDS Prevention and Care Programme, 2007; F. Emmanuel, C. Archibald, A. Altaf (2006), 'What drives the HIV epidemic among injecting drug users in Pakistan: A risk factor analysis', Abstract MOPE0524, XVI International AIDS conference, 13-18 August, Toronto.

The Future of HIV in Asia 43

31 C. D. Des Jarlais, et al. (2000), 'Behavioral risk reduction in a declining HIV epidemic: injection drug users in New York City, 1990-1997', American Journal of Public Health,90 (7), pp. 1112-16.

32 A.G. Davies, R.M. Cormack, and A.M. Richardson (1999), 'Estimation of injecting drug users in the City of Edinburgh, Scotland, and number infected with human immunodeficiency virus', International Journal of Epidemiology, 28 (1), pp. 117-21.

33 Hong Kong SAR has also shown that widespread access to opioid substitution therapy can be effective. Heroin is the most commonly injected drug throughout Asia. Synthetic substitutes for heroin, such as methadone and buprenorphine (which can be taken orally) can reduce frequency of injection. They also reduce the likelihood that people will share neeclles when they do inject, as substitute drugs reduce craving, and injectors say it is the hunger for an immediate fix that often pushes them into situations where they share needles.

34 National Institute of Hygiene and Epidemiology, Viet Nam Ministry of Health, and Family Health International (2005-2006). Results from the HIV/ STI Integrated Biological and Behavioral Surveillance (IBBS) in Vietnam.

35 Data obtained by E. Pisani, courtesy of the China UK HIV/AIDS Prevention and Care Programme, 2007.

36 S.F. Vanichseni, et al. (2004), 'Risk Factors and Incidence of HIV Infection Among Injecting Drug Users (IDUs) Participating in the AIDSVAX© B/E HIV Vaccine Efficacy 'Thal, Bangkok! Abstract TUPpC2043, XV International AIDS Conference, Bangkok, Thailand.

37 A.K. Buavirat, et al. (2003), 'Risk of prevalent HIV infection associated with incarceration among injecting drug users in Bangkok, Thailand: case-control study', British Medical Journal, 326 (7384), p. 308.

38 S.M. Panda, et al. (2005), 'Risk factors for HIV infection in injection drug users and evidence for onward transmission of HIV to their sexual partners in Chennai, India', Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, 39 (1), pp. 9-15.

39 Annual HIV Surveillance Report, 2007 (in Bahasa-Indonesia), Republic of Indonesia, Jakarta: Ministry of Health, courtesy of E. Pisani.

40 C. Beyrer, et al. (2003), 'Drug use, increasing incarceration rates, and prison-associated HIV risks in Thailand', AIDS Behaviour, 7 (2), pp. 153-61.

4I WHO, UNAIDS, and UNODC (2007), 'Effectiveness of Interventions to Manage HIV in Prisons: Needle and syringe programmes and bleach and decontamination strategies', Geneva, World Health Organization, UNAIDS, UNODC.

42 K. Dolan, et al. (2007), 'HIV in prison in low-income and middle-income countries', Lancet Infectious Diseases, 7 (1), pp. 32-41.

43 R. Heimer, et al. (2006), 'Methadone maintenance in prison: evaluation of a pilot program in Puerto Rico', Drug and Alcohol Dependency' , 83 (2), pp. 122-9.

44 K. Dolan, S. Rutter, and A.D. Wodak (2003), 'Prison-based syringe exchange programmes: a review of international research and development', Addiction, 98 (2), pp. 153-8.

45 K. Stark, et al. (2006), 'A syringe exchange programme in prison as prevention strategy against HIV infection and hepatitis B and C in Berlin, Germany', Epidemiological infection, 134 (4), pp. 814-19.

46 UNAIDS (2007), 'Men who have sex with men: the missing piece in national responses to AIDS in Asia and the Pacific', Bangkok: UNAIDS RST-AP.

47 E van Griensven, et al. (2005), 'Evidence of a previously undocumented epidemic of HIV infection among men who have sex with men in Bangkok, Thailand', AIDS, 19, pp. 521-6.

48 National Institute of Hygiene and Epidemiology, Viet Nam Ministry of Health, and Family Health International (2005-6). Results from the HIV/STI Integrated Biological and Behavioral Surveillance (IBBS) in Vietnam.

49 Cambodian national surveillance data 2005 (National Center for HIV/AIDS Dermatology and STDs Cambodia 2006).

50 E van Griensven, et al. (2005), 'Evidence of a Previously undocumented, epidemic ..!

51 F. Emmanuel (2007), 'Changing pattern of HIV/AIDS in Pakistan: Low prevalence to concentrated Epidemic among IDUS', 8th International Conference on HIV/AIDS in Asia and the Pacific, Colombo, Sri Lanka.

52 P. Girault, et al. (2004), 'HIV, STIs, and sexual behaviors among men who have sex with men in Phnom Penh, Cambodia', AIDS Education and Prevention, 16 (1), pp. 31-44; E. Pisani, et al. (2004), 'HIV, syphilis infection, and sexual practices among transgenders, male sex workers, and other men who have sex with men in Jakarta, Indonesia', Sexually Dansmitted Infections, 80 (6), pp. 536-40.

53 Derived from Asian Epidemic Model estimates for Asia; complete details of the model and its results are provided in the nchnical Annex.

54 The estimate is derived from a synthesis of the estimated size of various most-at-risk and low-risk population groups, in the countries of Asia. References for the country-specific data used to arrive at this regional estimate are available in the lbchnical Annex.

55 Estimates are based on Asian Epidemic Model calculations for Cambodia.

56 MAP (2004), AIDS in Asia: Face the facts, Monitoring the AIDS Pandemic Network, Bangkok. Available at

57 K. Ruxrungtham, et al. (2004), 'HIV/AIDS in Asia', The Lancet, 364 (9428), pp. 69-82.

58 The extent of other behaviours, including the sharing of contaminated injecting equipment by drug injectors and sex between men was also kept at 2007 levels. It was also assumed that antiretroviral treatment would reach 50 per cent of those in need by 2010 and 80 per cent of those in need by 2020. In some countries where coverage has expanded rapidly and infrastructure is strong (such as Thailand), higher levels of antiretroviral coverage were assumed.

59 GDP data calculated from GDP per capita adjusted for purchasing power parity, in constant year 2000 USD, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) database.

60 This hypothesis is yet to be validated in a scientific study.

61 A. Greenspan (1992), Asia-Pacific Population & Policy, 22, Honolulu, East-West Center.

62M. Ono-Kihara, et al. (2002), 'Sexual practices and the risk for HIV/STDs infection of youth in Japan', Journal of the Japan Medical Association, 126 (9), pp. 1157-60.

63 In both Thailand and Tamil Nadu (in India), a reduction in the number of men who visit sex workers was associated with increased casual sex but not necessarily with increases in HIV transmission. In both cases, this occurred in the wake of large-scale HIV interventions which promoted condom use and the reduction of risky behaviours. This also occurred amid relatively strong economic growth, expanded education opportunities, and greater sexual freedom. However, no systematic study has been carried out to investigate such correlation or establish possible causality between development and changes in sexual behaviours in Asia.

64 UNAIDS/WHO (2007), AIDS Epidemic Update, December 2007, Geneva.

65 UNAIDS (2006), 2006 Report on the global AIDS epidemic, Geneva.

66 Research in the Guntur district in the southern state of Andhra Pradesh showed that HIV infection levels found in a population-based study were about half as high as those based on sentinel surveillance. See L. Dandona, et al. (2006), 'A population-based study of human immunodeficiency virus in south India reveals major differences from sentinel surveillance-based estimates', BMC Medicine, 4 (31).

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|