4 Opium in the Fens

| Books - Opium and the People |

Drug Abuse

Opium in the Fens

Despite the difficulties of reconstructing patterns of opium use, a detailed picture can be put together of what was happening at this time in one particular area. Opium consumption in the Fenland was arguably untypical in that it was high, and extensive enough to attract particular attention at the time. The spotlight thrown upon it by the mid-century public health inquiries, and its importance as evidence during the later anti-opium agitation, is invaluable. It is possible to reconstruct the incidence of popular opium use, however imperfectly, in a rural setting.

The low-lying marshy Fens covered parts of Lincolnshire, Cambridgeshire, Huntingdonshire and Norfolk. Remote and isolated by reason of their geography, there had been attempts to drain them and to improve the agricultural land on an individual basis since the sixteenth century. Work in northern Fenland had been carried out in the following century with the aid of Dutch engineers. Yet Arthur Young in his late-eighteenth-century Annals of Agriculture commented that much of the Fenland was still subject to frequent inundation. It was only at the turn of the century, with the drive to agricultural improvement and enclosure which paralleled industrial developments, that further drainage work was undertaken on a major scale. For much of the first half of the century, the Fens remained an unhealthy, marshy area, where medical assistance was limited, especially for the poor, and where large numbers of the working population of the countryside were prone to the ague, `painful rheumatisms' and neuralgia.1

The fact that these conditions had led to a noticeably high consumption of opium was commented on at the tlime. `There was not a labourer's house ... without its penny stick or pill of opium,and not a child that did not have it in some form.' According to an analysis made in 1862, more opium was sold in Cambridgeshire, Lincolnshire and Manchester than in other parts of the country.' As elsewhere, poppy-head tea had been used as a remedy long before other narcotics were commercially available. Charles Lucas, a Fenland physician, recalled the widespread use of the remedy. `A patch of white poppies was usually found in most of the Fen gardens. Poppy-head tea was in frequent use, and was taken as a remedy for ague.... To the children during the teething period the poppy-head tea was often given.3 Poppies had been grown in the area for the London drug market, where they were used to produce syrup of white poppies ; and there had even been attempts made in Norfolk to produce opium on a commercial scale.

Although the use of opium, in one form or another, was certainly not new in the Fenland area, in the nineteenth century commercial opium and opium preparations were more widely used. Shifts in the structure of agrarian society may also have made the use of opiates more widespread (the practice of enclosure degraded the status of the agricultural labourer). A greater awareness of, and concern about, the practice grew up through the numerous social surveys and statistical exercises which characterized these years. The impression is of a long-established habit suddenly brought to light by growing interest in, and increased access to, the Fenland area.

The high general death rate in agricultural Lincolnshire - 22 per i,000 living in Spalding in the 1 840s, as high as industrial areas like Huddersfield and Keighley - was enough to single it out. It was notable too that the death rate from opium poisoning (primarily based on laudanum deaths) was 17.2 per million living average over the 1863-7 period in the Midlands area, which included Fenland Lincolnshire. This figure had risen to 23.8 per million in 1868, the year when the restrictions of the Pharmacy Act were introduced. This was far higher than the national opium death rate, averaging 6 per million in the same five years .4 It was this type of evidence which stimulated investigations by Dr Henry Julian Hunter in the 1 860s. Reporting to Sir John Simon, as Medical Officer to the Privy Council, in 1863, on the excessive mortality of infants in some rural districts, he wrote:

A man in South Linconshire complained that his wife had spent a hundred pounds in opium since he married. A man may be seen occasionally asleep in a field leaning on his hoe. He starts when approached, and works vigorously for a while. A man who is setting about a hard job takes his pill as a preliminary, and many never take their beer without dropping a piece of opium into it. To meet the popular taste, but to the extreme inconvenience of strangers, narcotic agents are put into the beer by the brewers or sellers.5

Others who had practical experience of the area told the same story. The basis of adult opiate use in the area appears to have been what a pharmacist who practised there in the early 1900s termed `The three scourges of the Fens ... ague, poverty and rheumatism'.

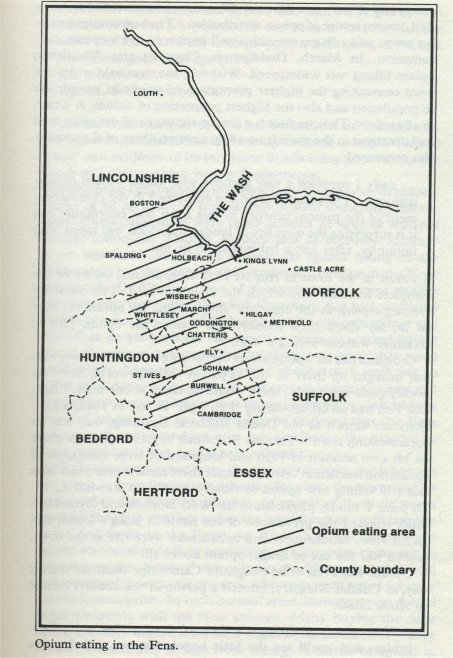

The area where opium eating was common can be delineated fairly clearly. It appears to have stretched from Boston in the north (although there is some indication that there was a lesser incidence of the habit as far north as Louth), into the Isle of Ely, where it concentrated, and on round King's Lynn and towards Castle Acre in the east. St Ives and the Fenland area of Huntingdonshire was its south-west boundary; Burwell, Soham and Methwold on the south-east, the area round Whittlesey in the west. Opium was, of course, used well beyond these limits; but dependence on the drug was not so exceptional as in the Fens.

A pharmacist who arrived in Louth from Edinburgh to take up a new post in 1913 still remembers her feelings of surprise at the much greater quantities of opium sold there. Twenty years earlier, Dr Rayleigh Vicars had been equally perplexed by the unaccountable symptoms of a patient of his in Boston. One of her friends soon set him right. 'Lor', Sir, she has had a shillings worth of laudanum since yesterday morning.'6 Holbeach, too, had an opiumeating reputation. `It has always been understood that Holbeach is a great laudanum district, and, as might be expected, the drug is sold in immense quantities....' Dr Harper, working at the Holbeach Dispensary, was surprised at the longevity of the opium eaters who came. Fifteen who attended had an average age of seventy-six years, although all were taking over a quarter of an ounce of the drug each week. Even as late as r909, a pharmacist apprenticed in the town remembers several addicts who were supplied, and the large quantities of opium sold.?

The habit centred on the Isle of Ely. Ely itself, `the opium eating city of Ely', as a Morning Chronicle reporter called it, was a well-known centre of opium distribution." The surrounding market towns and villages were also well known for their opium consumption. In March, Doddington, Chatteris and Whittlesey, opium taking was widespread. Wisbech, too, was said to be the town consuming the highest proportion of spirits in proportion to population and also the highest proportion of opium. A letter, in 1894, from Thomas Stiles, a ninety-six-year-old druggist, who had practised in the town from 1813, gave evidence of the quantities consumed:

... daily I supplied a vast number with either opium or laudanum ... The amount of opium consumed in the commencement of the present century in this form was enormous, and it is surprising the quantity of laudanum which was taken with impunity, after being habituated to its use..."

A visitor to the town in August 1871 soon became aware of the complete freedom with which the drug was sold. The Saturday evening crowds in the chemists' shops `come for opium ... they go in, lay down their money, and receive the opium pills in exchange without saying a word'."

Croyland had its `opium slaves', according to Mrs Burrows, who was brought up there in the 1850s. A shillingsworth made up twenty good-sized pills; these would be taken at one dose." Burwell Fen had an opium-eating `Fen tiger' as late as 1910, a local character known as old Daddy Badcock. Spalding, too, was an opium-eating town - Thomas Stiles had begun to practise there on his own account in 1826 and `disposed of large quantities of opium and laudanum'. An apprentice there some ninety years later was still selling raw opium to elderly people `to alleviate fever'. Dr John Whiting, physician to the West Norfolk and Lynn Hospital, stressed the prevalence of the habit in King's Lynn, too. In his view, drunkenness and debauchery were rife in the town, and so was the use of drugs, opium above all.

Opium was even to be bought in Cambridge itself on market day, as Charles Kingsley, himself a parson in the county, related in Alton Locke:

'Yow goo into druggist's shop o' market day, into Cambridge, and you'll see the little boxes, doozens and doozens,already on the counter; and never a ven-manls wife goo by, but what calls in for her pennord o' elevation to last her out the week. Oh! ho! ho! Well, it keeps women-folk quiet, it do; and it's mortal good agin ago pains.' `But what is it?'

`Opium, bor' alive, opium!'12

As soon as the marshlands were left behind, the habit died away. The custom was established in these higher lands to only a `limited extent' and evidence of its incidence in adjoining areas, as for instance in Leicestershire, is only fragmentary.

High opium consumption may have been to some extent characteristic of all agricultural populations in such low-lying, marshy areas. Historically there were other pockets of ague (a malarial disease) round the Thames Estuary and in Romney Marsh.13 There was little evidence of exceptional opium taking in the former area; but the practice did occasionally emerge in the Kent marshlands. Dr Thomas Joyce of Rolvenden noted some strange developments there after the 1868 Pharmacy Act had restricted the sale of opium by unqualified vendors: `In my own village and immediate neighbourhood this practice exists to a considerable extent, the opium being retailed by the grocer and other small shopkeepers. I am credibly informed about 3 oz a week are so distributed. Since January last, four cases of opium sickness and purging have come under my own immediate notice ... and I have heard of others.'14 It can reasonably be assumed that the Fens remained the opium-taking area par excellence; the practice in other marshlands was only a pale reflection.

The largest consumers were the country people, the labourers who came in from the outlying marshy fens into the towns to buy it on market day, `not the villagers, or people of the little towns in which the shop was, but rather the inhabitants of small hamlets or isolated farms in the Fens'. In Wisbech it was the country people who came to do their marketing on a Saturday evening who crowded out the chemists' shops. It was the `Fen tigers', the small dark people of the remoter districts, who were most noted for their opium consumption. In such isolated areas, laudanum was shared indiscriminately with the farm animals. Many buying the drug stated that they wanted it for their pigs, not for themselves - `they fat better when they're kept from crying'. The use of opium in cattle medicines was not unique to the Fens, although its use was said to be on the increase in the 1850s. Six drachms of laudanum for a sheep and two or three ounces for a horse were not unusual. One child who died from opium poisoning in Cambridgeshire in 1838 had accidently drunk laudanum intended for a calf. Opiates were mostly used throughout East Anglia, and probably elsewhere as well, to dope vicious or unmanageable horses before they went

for sale. 15

It was the doping of young babies that had first attracted attention to the high consumption of opium in the Fens. The introduction of new methods of exploiting the land had resulted in particular in declining standards of child care. The drainage of areas under water and their cultivation led, in the nineteenth century, to the use of itinerant `public gangs' composed of both women and children, and employed by a gang master. The underpopulated nature of the drained areas meant that the gangs, supplying the lack of a settled labour force, ranged over wide areas. Although the public gangs were by no means the norm in the Fenland, it is true that, where they existed, women were away from home for long periods and the care of young babies suffered.16

The extremely high infant mortality rates in the Fenland towns, a06 per i,000 living in Wisbech, higher than in Sheffield in the 1860s, were sufficient to indicate the special circumstances there. The old custom of. dosing children with poppy-head tea was to some extent replaced by the sale of the commercially produced opiate, or at least 'Godfrey's' which the chemist made himself. But the dosing of babies was not overly peculiar to the Fens (child dosing with opium is discussed in Chapter 9). It went on in areas far beyond the marshlands - in Yarmouth, Walsingham, Downham, Goole. It is possible, too, that opiates were used, inadvertently or not, to dispose of unwanted children - `Twins and illegitimate children almost always die.' This may have been the case outside the Fens as well.

The habit was also noticeable among working-class women, their use of the drug perhaps originating from `tasting' the opiates which they gave their children, as well as from the tradition of self-medication, `the wretchedness of their homes', and the demands on some women of the gang system. A woman came into a druggist's shop in Ely while the Morning Chronicle reporter was there, asked for a pennyworth of laudanum and drank it off with the `utmost unconcern' before his startled eyes.'' Other elderly females took up to thirty grains a day and an old woman at Wisbech was accustomed to a daily dose of ninety-six grains.18

The origins of such a situation lay not in unwise medical prescription, since few of the most obvious consumers would have seen a doctor at all regularly - Dr Harper's surprise at the opium eaters who came to the Holbeach Dispensary is proof of that. The druggist's shop, not the doctor's surgery, was at its centre. It symbolized the dominance of the consumer of the drug, not its prescriber, as already noted in Chapter 3. It had its basis in the peculiar circumstances of the area, but also in the tradition of popular self-medication. Use for simple euphoric effect was a possibility in the Fens. The writer Thomas Hood, on a visit to Norfolk, `was much surprised to find that opium or opic, as it was vulgarly called, was in quite common use in the form of pills among the lower class, in the vicinity of the Fens ... the Fen people in the dreary, foggy, cloggy, boggy wastes of Cambridge and Lincolnshire had flown to the drug for the sake of the magnificent scenery... '19 Dr Rayleigh Vicars also recognized this as the case. He found a patient `apparently unconscious of everything excepting the strange visions floating through the sensorian and giving rise to the erratic movements and gestures'. He commented, after this abrupt introduction to the popularity of opium among his patients, that `.. . their colourless lives are temporarily brightened by the passing dreamland vision afforded them by the baneful poppy'.20

It is possible to make some estimate of the amount of opium sold and taken individually in the Fens. It came into the area on farmers' carts and was sold, as elsewhere in the country prior to 1868, through a multiplicity of outlets, of which chemists' shops were only the most obvious. Opium was sold `by almost every little country shopkeeper and general dealer', on market stalls, and hawked from village to village by itinerant vendors. The British Medical Association estimated in 1867 that Norfolk and Lincolnshire consumed half the opium imported into the country.21 This, estimated on the basis of 1859, the last year for which home consumption figures are available, would be at least 30,000 lb. and possibly more. Shop counters in the Fenland towns were loaded every Saturday night with three or four thousand laudanum vials. One firm sold two hundred pounds of opium a year in the March/ Wisbech area. In Spalding, the druggists' sales in the 1860s averaged approximately 127 grains per head of the local population there. A druggist in Ely sold three hundredweight a year, and two others eighty or ninety pounds each .22

This was only the relatively `respectable' and obvious tip of opium sales. The turnover in grocers' and general shops went unrecorded. Poppy-head tea was brewed at home. The main opiates sold commercially were, as elsewhere, laudanum and crude opium itself. The latter, sold either in pill form, or carved in square lumps about an inch in length, seems to have been most popular, although laudanum was said to be favoured by women consumers. `Pills or penny sticks' were what Dr Hunter saw on sale, and others describe farmers' wives and labourers buying their penny packets of opium. Actual consumption and expenditure are difficult to estimate. Thirty grains was a pennyworth, the average daily dose of those who had taken the drug over a long period. Dr Elliott found that an average dose was half an ounce a week of solid opium or four ounces to half a pint of laudanum in the morning and the same in the evening. Many took more. A St Ives druggist remarked that people had come into his shop and drunk off two scruples of opium.

I have been really frightened to see them take it in such quantities, I thought it would have killed them. When they came into the shop I have seen them look very bad, and have asked them if they were used to taking it in such large doses, and they have said `Oh yes!' But I certainly thought by the ravenous way in which they took it out of the box, that they wanted to poison

themselves.'23

Actual expenditure is even more difficult to estimate. It was said later on, in the 1870s, that families were spending eight-pence to one shilling a day on it. A Croyland addict, buying enough to make forty pills, was spending two shillings a day, a very sizable proportion of an agricultural labourer's wage. In Holbeach, laudanum was fourpence an ounce; so weekly consumption of eight ounces was less expensive. Laudanum had been sixpence an ounce early in the nineteenth century; by mid century it was threepence in Ely and fourpence in St Ives.

Opiate use in the Fens was culturally accepted and sanctioned in a way which might not seem strange in South-East Asia, but which is striking in such an English setting. The majority of the labouring part of the Fenland population and those shopkeepers selling opium clearly accepted its use on a regular basis as something quite normal, not only in the early decades of the century, but, to a lesser extent, well into the 1870s and 1880s. The case of the Fens emphasizes the general attitude of poor users to the drug. There was a general absence of concern. In Boston, Dr Rayleigh Vicars had to struggle against the community support offered his opium-eating patient in order to impose a medical imprint on the situation. `The neighbours,' he reported, `... indulge in the same lethal habit, and encourage the fatal termination by goodnaturedly lending their own private store of laudanum.' In Croyland, as elsewhere, buying opium was an errand for a child to go on, just like any other small purchase. One had the `daily duty... to go every morning for a shillings worth of opium, or, as it was nicknamed, "stuff'...' The unconcern of Fenland society is perhaps best demonstrated by the encounter in the Wisbech chemist's shop in 1871. The writer:

Went into a chemist's shop, laid a penny on the counter. The chemist said - `The best?' I nodded. He gave me a pill-box and took up the penny, and so the purchase was completed without my having uttered a syllable. You offer money, and get opium as a matter of course. This may show how familiar the -

custom is.24

The existence of a domestic population which could apparently control and moderate its consumption became a matter of interest later in the nineteenth century. The public health concern of midcentury abated; but the case of the Fens continued to be important to those involved in the debate on the Indo-Chinese opium trade and the allied issue of the effects of regular opium use. The interpretation of opium eating in the Fens at mid-century was marked by a relative absence of the sort of concern which was evoked by opium use in an industrial setting. The possibility of the 'stimulant' use of opium by the industrial working class was one of the reasons behind the drive to control sales of opium at mid century. Lower-class use in urban areas was important as an argument in seeking greater professional control over the sale of drugs. This is dealt with in Chapter 9. Yet opiate eating in the Fens was used by professional interests in exactly the opposite way. For opium was removed from the more restrictive Part One of the poisons schedule of the 1868 Pharmacy Act (the controlling legislation) precisely because of protests from Fenland pharmacists, who feared their trade would be affected by too much control .2' This was indicative of the way in which views of opiate use were coloured by social and class setting. `Stimulant' opium use in the cities was part of the threat posed by the industrial working class. The opium-eating labourer in the Fens was a different matter, even if, as Hood surmised, he had taken the drug in part for its stimulant effect. Middle-class and `respectable' opium use was of course rarely a matter of concern, even in the case of stimulant use by the _ Romantic writers.

Regular and widespread opium use was clearly in decline by the last quarter of the century, although consumption in the Fenland area remained notably higher (in particular in the eyes of pharmacists who practised there) as late as the 19005.26 It had been, in its time, a notable example of the operation of a system of open availability of opium. It had demonstrated how a population could succeed in controlling by informal social mechanisms its consumption of the drug, with only minimal medical and legislative intervention. The reminiscences and accounts of the practice given by doctors have the air of being given by outsiders standing on the periphery of a quite different cultural tradition of drug use. The Fens were a specific instance of the popular culture of opiate use in the first half of the century - opium used in a rural setting in a manner which varied only in degree from the pattern of consumption in the rest of society.

References

1. H. C. Darby, `Draining the Fens', in L. F. Salzman, ed., Victoria History of the County of Cambridge and the Isle of Ely (London, University of London, Institute of Historical Research, 1948), PP. 75-6, and H. C. Darby, The Draining of the Fens (Cambridge, 2nd edn 1956), p. 65.

2. L. M. Springall, Labouring Life in Norfolk Villages (London, G. Allen and Unwin, 11936), p. 59; D. W. Cheever, `Narcotics', North American Review, 95 (1862), pp. 375-415. V. Berridge, `Fenland opium eating in the nineteenth century', British Journal of Addiction, 72 (11977), pp. 27584, discusses the question of the Fens in greater detail.

3. C. Lucas, The Fenman's World. Memories of a Fenland Physician (Norwich, Jarrold and Sons, 1930), P. 52.

4. E. Gillett and J. D. Hughes, `Public health in Lincolnshire in the nineteenth century', Public Health, no volume number (1955), pp. 34-4o, 55-60; local figures are also quoted in P.P. 1864, XX V I I I : Sixth Report of the Medical Officer of the Privy Council, 1863, Appendix 14, `Report by Dr Hunter on the excessive mortality of infants in some rural districts of England', p. 459.

5. Dr Hunter's report, op. Cit., p. 459.

6. G. Rayleigh Vicars, `Laudanum drinking in Lincolnshire', St George's Hospital Gazette, 1 (1893), PP. 24-6.

7. W. Lee, Report to the General Board of Health on a Preliminary Inquiry into the Sewerage, Drainage, and Supply of Water, and the Sanitary Condition of the Inhabitants of the Parish of Holbeach (London, W. Clowes and Sons, 1849), p. 14; `Opium eating in England', British Medical .Journal, 2 (1858), p. 325; W. Waterman, retired pharmacist, personal communication, 1977.

8. Morning Chronicle, 26 December 1850; W. Lee, Report to the General Board of Health on ... the parish of Ely (London, W. Clowes and Sons, 1850) PP. 18-19.

9. P.P. 1894, LXII: Royal Commission on Opium, q. 24706.

10. `Notes on Madras as a winter residence', Medical Times and Gazette, n.s. 14 (1857), P. 426.

11. Quoted in M. Llewelyn Davies, ed., Life As We Have Known It (London, 1931, Virago reprint 1977), pp. 113-14.

12. C. Kingsley, Alton Locke (London, 185o, Everyman edn 1970), p.130.

13. G. H. F. Nuttall, L. Cobbett and T. Strangeways-Pigg, `Studies in relation to malaria. I : The geographical distribution of anopheles in relation to the former distribution of ague in England', Journal of Hygiene, 1 (1901), pp. 4-44.

14. T. Joyce, `The Pharmacy Act and opium eaters', Lancet, 1 (1869), p. 150.

15. C. Marlowe, Legends of the Fenland People (London, Cecil Palmer, 1926), p. 134; `Increased consumption of opium in England', Medical Times and Gazette, n.s. 14 (1857), P. 426; G. Ewart-Evans, personal communication, 1975 and 1976. The high level of laudanum use for animals was still notable in the area in the 1920s : Home Office papers, H.O. 45, 11932

16. P.P. 1867, X V I : Children's Employment Commission: Sixth Report of the Commissioners on Organized Agricultural Gangs... p. 183; P.P. 18678, X V I I

First Report of the Commission on the Employment of Children, Young Persons and Women in Agriculture, p. 131.

17. Morning Chronicle, 27 September 1850.

18. Evidence on the apparent female preponderance is in E. Porter, Cambridgeshire Customs and Folklore (London, Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1969), pp. 13, 26; M. Llewelyn Davies, op. cit., pp. 113-14; Parliamentary Debates (Hansard), 352 (1891), col. 314.

19. T. Hood, Reminiscences, quoted in H. A. Page, Thomas De Quincey His Life and Writings (London, John Hogg, 1877), pp. 233-4.

20. G. Rayleigh Vicars, op. cit., pp. 24-6.

21. L. M. Springall, op. cit., p. 59; P. P. 186o, L X I V : Accounts and Papers. Imports and Exports of Opium.

22. Evidence on quantities sold is in the Morning Chronicle, 26 December 185o; The Times, 23 September 1867; A. Calkins, Opium and the Opium Appetite (Philadelphia, J. Lippincott, 1871), p. 34.

23. Morning Chronicle, op. cit.

24. Medical Times and Gazette, n.s. 14 (1857), P. 426

25. `General Medical Council. Pharmacy', Medical Times and Gazette, 2 (1868), PP. 51-2; `Report of the Pharmacy Bill committee to the General Medical Council', British Medical journal, 2 (1868), p. 39.

26. The later history of Fenland opium use is discussed in V. Berridge, op. Cit., pp. 275-84.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|