3 Open Sale and Popular Use

| Books - Opium and the People |

Drug Abuse

Open Sale and Popular Use

Opium, once imported, passed through a mechanism of wholesaling and retailing which finally brought it within reach of the ordinary consumer of the drug. Until 1868, there were no bars on this process at all (and even after 1868 restrictions were still quite minimal). The chapters in this Part will analyse how such a system of free availability and sale operated in the early decades of the century and how opium was used not just medically but for non-medical reasons as well at all levels of society.

Opium was an everyday part of the drug trade. Once sale negotiations had taken place, it became the property of a wholesale drug house. There had been such wholesalers in London since the seventeenth century, and firms like William Allen & Company, of Plough Court (ancestor of Allen and Hanbury), had been in existence since the early eighteenth century. It was in the early part of the following century, however, that the process speeded up. Not only wholesale drug houses but manufacturing druggists, too, were established in profusion. Meggeson and Company in 1796 and May and Baker in Battersea in 1834 were among the earlier examples. Often there was no initial distinction in function, The early businesses dealt with many aspects of what later became specialized fields of the pharmaceutical industry. Thomas Morson and Sons Limited, for instance, the first commercial manufacturer of morphine in Britain, began as an apothecaries' business in Fleet Market in 1821. Wholesaling, manufacturing and retailing were at that stage all part of the same operation; not until 1900 did Morsons actually give up their retail business.' The wholesale druggists did not just sell but also manufactured their own opium preparations, a process which naturally provided much scope for adulteration, at a time when there was no legislative control .2 The Apothecaries' Company, perhaps the most prestigious of the wholesaling houses, was manufacturing twenty-six opium preparations in 1868, including two morphine preparations, the hydrochlorate and the acetate, as well as its popular

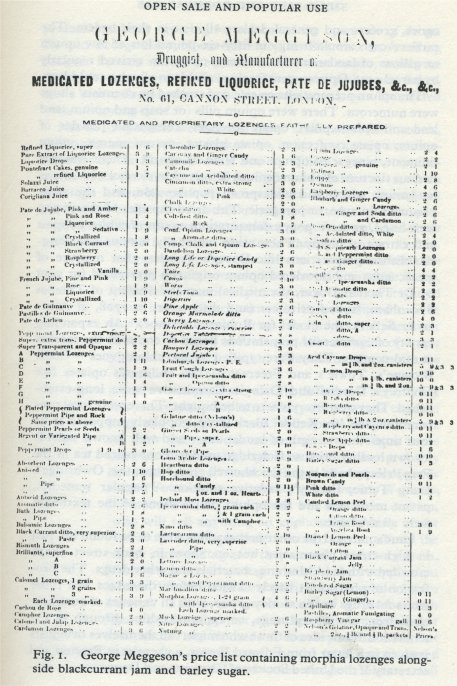

`Cholera number two' mixture. In 187 t, it had twenty-five on its books, including the oddly titled Fire Brigade mixture (Mist pro. Fire Brigade) which contained opium.3 William Allen, in Plough Court, had sixteen opium preparations on his list in 1810, twenty in 1811. One wholesale druggist was selling poppy capsules at is. 10d. for a hundred, opiate plaster, Hemmings' extract of opium and syrup of white poppies, Battley's Sedative Solution, morphine acetate and hydrochlorate, Turkey opium, as well as Black Drop and the special Godfrey bottles (three dozen for 10s.).' Top sellers in the opium line are difficult to pin-point. Allen's kept most stockof opiate confection, extract of opium, the gum (or raw) drug, various varieties of laudanum, and syrup of white poppies. Later in the century, morphine hydrochlorate, paregoric, raw and powdered opium, laudanum, and gall and opium ointment were the Apothecaries' Company's most popular products. In the eighteenth century, the central wholesalers had dealt direct with provincial apothecaries. In the latter years of the century, however, and increasingly in the nineteenth, a number of provincial wholesale houses established themselves, often developing as specialist businesses from grocers who found drugs their most profitable line.5 Some chemists still dealt directly with the central wholesalers,6 but it became customary for local chemists to buy opium from local wholesalers rather than direct from London. In 1890, W. Kemp and Son at Horncastle, one of these local businesses, still offered nine opium preparations. There were special quotations for twenty-eight-pound and fifty-six- pound lots of Turkey opium. More specialist opium preparations continued to be obtained from London. George Meggeson was the manufacturer there who led the market in the production of lozenges, and many opium and morphine based ones were on his price list (Figure 1).7

The opium stocks of such wholesalers, in the years before the 1868 Pharmacy Act limited the sale of the drug to professional pharmacists, were available to any dealer who chose to purchase. There was no limitation at all. Qualified pharmacists and apothecaries, grocers and general dealers all sent in their orders. The carriers' carts would bring out fifty-six-pound lots of raw opium or gallons of laudanum for delivery; or opium arrived regularly by parcel post. Opiates were freely available to all who could buy.

The opium preparations on sale and stocked by chemists' shops were numerous. There were opium pills (or soap and opium, and lead and opium pills), opiate lozenges, compound powder of opium, opiate confection, opiate plaster, opium enema, opium liniment, vinegar of opium and wine of opium. There was the famous tincture of opium (opium dissolved in alcohol), known as laudanum, which had widespread popular sale, and the camphorated tincture, or paregoric. The dried capsules of the poppy were used, as were poppy fomentation, syrup of white poppies and extract of poppy. There were nationally famous and long-established preparations like Dover's Powder, that mixture of ipecacuanha and powdered opium originally prescribed for gout by Dr Thomas Dover, the medical man and student of Thomas Sydenham, turned privateer (and discoverer, in 1708, of Alexander Selkirk, the model for Robinson Crusoe).8 An expanding variety of commercial preparations began to come on the market at mid-century. They were typified by the chlorodynes - Collis Browne's, Towle's and Freeman's. The children's opiates like Godfrey's Cordial and Dalby's Carminative were long-established. They were everywhere to be bought. There were local preparations, too, like Kendal Black Drop, popularly supposed to be four times the strength of laudanum - and well known outside its own locality because Coleridge used it. Poppy-head tea in the Fens, `sleepy beer' in the Crickhowell area, Nepenthe, Owbridge's Lung Tonic, Battley's sedative solution - popular remedies, patent medicines and the opium preparations of the textbooks were all available.

Laudanum and the other preparations were to be found not just in high-street pharmacies but on show in back-street shops crowded with food, clothing, materials and other drugs. The profession of pharmacist barely existed before the 1840s and those who sold drugs were a motley group, with all varieties of qualifications from customary usage, or apprenticeship, through to examination. Some idea of those who might call themselves druggists is given in a letter from Edward Foster, a chemist in Preston and secretary of the United Society of Chemists and Druggists, a semiprofessional body agitating for reform of the open sale of drugs. He told George Grey, Home Secretary, in 1865, that those selling drugs in Preston included a basket maker, shoe maker, smallware dealer, factory operative, tailor, rubbing stone maker and baker, and a rent collector, who, as he pointedly noted, was `connected with a burying club'.9

Not all drug sellers were of this type. There were, for instance, those pharmacists who had taken the, as yet, voluntary examinations set by the Pharmaceutical Society. There were also apothecaries under the jurisdiction of the Society of Apothecaries, which although it had theoretically extended its authority throughout

the country by the 1815 Apothecaries Act, exerted only lax inspection even in its traditional metropolitan area of control. And there were those who had learnt the trade through apprenticeship. These various groups appear sometimes to have surrounded the sale of opium with certain precautions even prior to 1868. Some, for instance, sold laudanum in a special poison bottle, or inquired for what purpose the purchaser wanted it. Others refused to serve persons unknown to them with drugs, or limited the purchaser to a certain amount. A friend of Professor Alfred Taylor of Guy's Hospital had been refused a drachm of laudanum for toothache in this way by a City chemist.'°

In the small corner shops, it was usually different. There, `They put down their penny and get opium.' Many of the people engaged in selling drugs and chemicals would sell opium with complete freedom, and their number was estimated in the 1850s to be between 16,000 and 26,000, although even this number probably

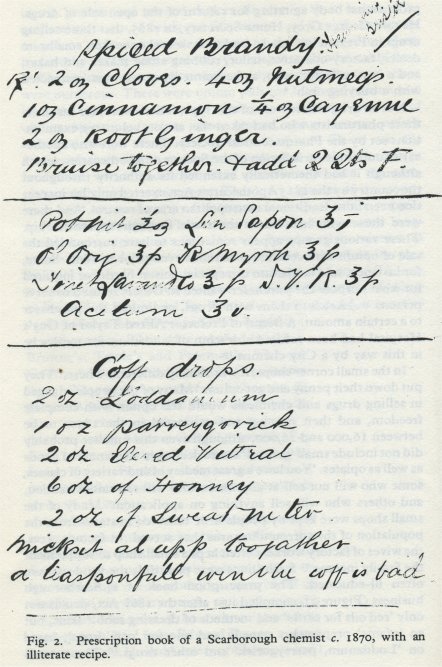

did not include small `general' stores dealing in all manner of goods as well as opiates. `You have a great medley of and variety of classes, some who will not sell at all, others who will sell under caution, and others who will sell anything on application.' Many of the small shops were kept by people little removed in status from the population of the surrounding area they served. In factory areas, the wives of factory workers often kept a small shop to supplement the family income." Such shops were plentiful; the vendors were often ill-educated. The prescription book of a Scarborough business (Figure 2), compiled just after the 1868 Act, details not only `red oils for cattle' and methods of dressing rabbit skins, but an infants' preparation remedy and one for 'coff drops', based on 'Loddanum, parreygorick' and other drugs. 12 These small businesses were everywhere to be seen, an everyday part of both urban and rural life. In a back street in Chorlton in 1849 surrounded by mills, there was a `shop in the "general line", in the window of which, amongst eggs, candles, sugar, bread, soap, butter, starch, herrings, and cheese, I observed a placard marked "Children's Draughts, a penny each" 1.13

It is easy enough to point to the mistakes and tragedies which undoubtedly occurred as a result of the system. The public health campaign of mid-century made great play of the sometimes horrifying carelessness of open sale. Professor Taylor himself had nearly lost a friend through the ignorance of a village shopkeeper

near Windsor, who had sent an ounce of laudanum instead of the 'syrup of rhubarb ordered. There was indeed no guarantee that the shopkeeper would have any knowledge of poisons at all, even though some obviously learnt by experience. In 1858, when Mr Story took over a shop at Guisborough, with its existing stock of groceries, draperies and drugs, `he was not thoroughly acquainted with' the latter commodities `and objected to take the whole of them, but the person leaving pressed him to do so'. When, in April, Fanny Wilkinson, a servant at Guisborough, sent for powdered rhubarb, that Mr Story confused the jar marked `Pulv. opii Turc. Opt' with Turkish rhubarb was hardly surprising. Fanny Wilkinson died after taking a teaspoonful of powdered opium; Mr Story had to stand trial for manslaughter.14 Many such small shopkeepers, the `chemists and grocers' who were still usually to be found in any city or town, picked up their dispensing knowledge where they could. It was for them that books like William Bateman's Magnacopia (1839) were produced. Its opium-based recipes for astringent balls, gout remedies and corn plasters mingled with others for ink, cleaning grates and making preserves.

It was intended as a `chemico-pharmaceutical library of useful and profitable information for the practitioner, chemist and druggist, surgeon-dentist etc.'.15

Even the small shops held a varied stock of opiates, or concocted their own preparations based on opium.16 Vendors sometimes had their own speciality, particularly in the `Children's Draught' line. Local varieties of `quietness' for soothing small babies were quite commonly to be found. The raw drug was often prepared for sale in the shop. It was purchased in square one-pound blocks which always came wrapped in red paper, labelled `opium (Turc)'.

An ex-apprentice remembered that `we ... peeled off the skin, softened it by pounding with a little honey in a mortar and then making quarter ounce, or half ounce and one ounce "loaves", wrapping them in Rouse's red waxed paper'. Opium was put on sale in one-drachm or two-drachm packets. The `gum' was dug from the cake of opium with a palette knife, weighed, rolled in French chalk and wrapped in greaseproof paper. In the better druggists an apprentice was often put in charge of weighing out the penny and two-penny portions of opium sold over the counter. These shops would also make up their own laudanum and other preparations. In the hands of an inexperienced druggist, this could be a source of error. Cutting opium fresh from a damp lump which should have been left until dry, together with careless weighing, could result in a preparation stronger than intended. 17

Nor were such shops the only places where opiates could be obtained. Street markets had their opium preparations. According to Samuel Flood, a surgeon in Leeds in the 1 840s, Saturday night purchases of pills and drops were a regular custom as much as the buying of meat and vegetables - `in the public market place ... are to be seen ... one stall for vegetables, another for meat, and a third for pills! ... '18 London costermongers were still selling the preparations in the 1900s, even if the paregoric they sold no longer contained opium. Opium was to be found on sale in pubs, too. Medical herbalists were common, and untrained midwives in working-class areas often had their own recipes as well. It was quite usual for an untrained doctor to act as medical adviser to the families in his area, prescribing mixtures containing laudanum for conditions such as diarrhoea and dysentery.

What needs greater emphasis than the mistakes which emerged as evidence in the public health campaign is the complete normality of open sales of opium to both seller and purchaser. An area of opiate use existed where doctors were never consulted and which, except at times of particular anxiety, was largely un-

remarked. Working people rarely encountered a trained doctor on any regular basis. A visit to a hospital out-patient department, a dispensary order or a subscription to a provident dispensary was, for most, the limit of professional medical care. Mostly such care was self-administered, and many of the preparations used were opium-based. The `official' medical uses of opium were paralleled by a quite distinct popular culture of opiate use. The `medical' use of opium was, by the end of the century, almost the only legitimate one. But earlier in the century popular use was as extensive, if not more so. Many subsequent medical developments were adaptations of, or prefigured by, established trends in self-medication; popular and medical forms of knowledge mingled. It is with this popular culture of opium use, the sale and use of opium among working-class consumers of the drug, that the rest of this chapter will deal.

The opium preparations sold in chemists and back-street shops were only commercial developments of practices common before industrialization. Poppy-head tea had long been a well-known rural remedy, for soothing fractious babies and for adults, too. Its use continued in the nineteenth century. Bob Loveday, Hardy's character in The Trumpet-Major, fell into a stupor through using poppy heads in the time-honoured way. '... I picked some of the poppy-heads in the border, which I once heard was a good thing for sending folks to sleep when they are in pain ...79 Poppy heads made into fomentations (often with camomile flowers) were still in regular use at the end of the century.

For over-the-counter sales, however, laudanum was universally recognized to be most popular for poor customers, although powdered opium was used, in making suppositories, for example, and in certain areas taking raw opium, rolled into pill-like masses, appears to have been quite common. Everyone had laudanum at home. Twenty or twenty-five drops could be had for a penny. Laudanum was also sometimes sold at threepence an ounce. The extent of such sales was barely realized in mid-Victorian England. Professor Taylor told the Select Committee on the Sale of Poisons in 1857 that `in many large manufacturing towns ... labouring men come to the extent of two hundred or three hundred a day for opium'.20 Some idea of the extent of demand became clear when Edward Hodgson, a pharmacist in Stockton-on-Tees, noted details of the number of customers he served with opiates over a summer month in 1857. Two hundred and ninety-two customers had bought opium from him over the month. As Hodgson was one of the six qualified chemists in the area, this presupposes that at least sixty people were buying opiates each day from this type of source alone, in a town with a population of twelve or thirteen thousand. 21

The sale which went on in general dealers made the evidence of accredited pharmacists bound to be an underestimate. The daybook of William Armitage, a `chemist and grocer' in Thorne, a village near Doncaster, gives some indication of the way in which sales were undramatically made. Between June and December 1850, he made twenty-nine over-the-counter sales of opiates, not including the opium-based doctors' prescriptions he dispensed in the same period. Thorne, where Armitage had his business, was hardly representative of the extent of urban purchasing. Yet the pennyworths of laudanum he sold, the two-pennyworth of paregoric to Mrs Coulam on 6 October, the mixed order of laudanum, acid drops and turpentine noted on 10 July, the fivepence left owing for opium by Stephen Webster, all give some flavour of the acceptability of opium as an everyday purchase.22

The corner shop, and not the doctor's surgery, was the centre of popular opium use. The balance of the drug seller/purchaser relationship often inclined to the latter. Customers often dictated the type of remedy they wanted. Families had their own private recipes which the shopkeeper or chemist would make up. It was

laudanum and ipecacuanha for coughs in one Hoxton family, lau-danum and chloroform (known as 'Gasman's mixture' from the person who had first suggested it) in another area. Twopenceworth of antimony wine with twopenceworth of laudanum for whooping cough was a remedy passed on in a Woolwich family.23 Sometimes the vendor interposed some degree of expertise in this process. One in Manchester recalled in 1849 that such `home-made' opium recipes often contained dangerous quantities of laudanum. He tried to convince the possessors of the remedies of the danger involved, and was sometimes allowed to change the proportions. There is little doubt that such remedies derived from the poppy recipes of pre-industrial living (many had been handed down in the same family for generations). The conditions of urban society brought the vendor of the drug into the situation when families could no longer produce their own remedies.

Opium was sometimes sold ready packaged in pill boxes, but the liquid preparations were measured into any container the customer provided. Shopkeepers kept their laudanum in large containers. It was measured into `bottles of all kinds ... dirty and clean'. This was in fact a strong argument against having a special

type of poison bottle -'They would take it ... to have some syrup of poppies, or any little innocent thing put in; it would be boughtwith the word "poison" upon it, and taken home, and it would become a very common bottle....' This practice meant too that the final strength of a preparation could sometimes be rather different from its original recipe. A half-emptied bottle of cordial would be bought, so that more laudanum could be put into it. Few opium preparations, patent medicines apart (Godfrey's Cordial had its own distinctive steeple-shaped bottles), were pre-packaged, the `jug and bottle' method of sale was almost universal.24

Going to the grocer's for opium was often a child's errand. In a large family, a harassed mother would send the eldest child, often kept at home to nurse younger brothers and sisters, out shopping. With such a system, there was often an instinctive bond between vendor and purchaser. The small corner shops, even the pharmacist's and druggist's businesses in areas where most sales were in pennyworths, did not see themselves as a group separate from their customers. There was a relationship of mutual dependence, which often resulted in a barrier of evasiveness presented to an outsider. Several told the Morning Chronicle reporter investigating Manchester conditions in 1849 that they knew nothing of the drug, while `several of them had their windows covered with announcements of different forms of the medicine which they were cool enough to declare they did not deal in'. Many accepted that some, at least, of their customers would be dependent on opium. If a large quantity was asked for, it was the custom to ask if the purchaser was in the habit of taking the drug and was accustomed to it.

Working people were relying upon opiates purchased in this way to deal with a whole range of minor complaints. They were a remedy for the `fatigue and depression' unavoidable in working-class life at the time. They acted as a cure-all for complaints, some trivial, some serious, for which other attention was not available. Medical herbalists and botanists, untrained midwives and self-trained doctors were used by the poor. For the most part, ailments were dealt with on the basis of community knowledge; and there was often positive opposition to the encroachment of trained doctors. It was in this situation where opium came into its

own. It was, for instance, widely used for sleeplessness.25 Many working-class consumers appear to have followed this advice. An inquest at Jarrow in 1891 revealed that the deceased had been accustomed to take laudanum for sleeplessness. The inquest on Amos Withers of Hull in 1881 noted that for four years he had been in the habit of taking 1 / 12 drachm of opium to alleviate pains in the head and stomach and to help him sleep.26 A pharmacist remembered that, as late as the 1900s, `... we sold laudanum, and before we closed on Saturday nights we had a few old ladies wrapped in shawls, bringing their old bottles for 3 d and 4 d of "lodlum" which helped them with their coughs and sleeping'.27

Middle-aged prostitutes, according to a factory area druggist, took it when they felt low or to relieve pains in their limbs. There was a large sale of gout and rheumatic pills each containing a grain of opium, colchicum extract and liquorice powder. These were an indication of the drug's popularity in the treatment of rheumatism. It was also a great standby for coughs and colds.28' Families could follow the advice given in domestic medical texts. Many chemists had their own opiate cough recipes. An octogenarian chemist remembered in the 1950s how `customers often asked for four-pennyworth each of oil of aniseed, oil of peppermint, laudanum and paregoric to be mixed with sugar syrup for a cough mixture'. The numbers of opiate-based cough remedies, `chest tonics' and rheumatic and diarrhoea pills in chemists' recipe books give an indication of the range of popular usage .29

It was always in the treatment of minor ailments, whose symptoms might or might not mask more serious complaints, that opiates were most useful. Dr Rayner at Stockport prescribed opiates in the form of eye drops as well as for sleep. The Doctor, a medical magazine offering advice to non-professionals, told one correspondent, 'A.Z.', to bathe a sore eye three or four times daily with a warm decoction of poppy heads. Elizabeth Adams, who died of an overdose of laudanum in Sussex in the summer of 1838, had taken it to cure toothache `unintentionally in too large quantity'. 30 Medical reliance on the drug to combat cholera or dysentery was paralleled by its popular currency as a remedy for diarrhoea.

It was as popular for earache as for toothache - `mix equal parts of purified ox-gall and liquid laudanum together, and let fall into drops every night into the affected ears'. For stomach cramp, `flatulencies, or wind', headaches, and nervous diseases in general, it was at least a palliative. In medical practice it was recommended for the treatment of insanity. There was advice in domestic texts for its use in hysteria. `Women's ailments' and the menopausewere popularly treated with opium, just as the drug was used in professional medicine to subdue such symptoms.

External use of the drug was common in popular usage. Buchan's Domestic Medicine, which ran into numerous editions in the first half of the century, recommended an anodyne plaster containing powdered opium and camphor for use in acute pains, especially of a nervous kind, and clysters or suppositories containing opium. A `liniment for the piles' was based on two ounces of emollient ointment and half an ounce of laudanum, mixed well together with the yolk of an egg. Buchan recommended anodyne balsam to be used in violent strains and rheumatic complaints. It should be rubbed `with a warm hand' on the affected part, or a linen rag moistened with the mixture and applied.31 For ulcers, bruises, sprains and chilblains (one text recommended a poultice of bread and poppy liquor renewed every six hours) it was in regular use. These were the type of small 'non-medical' ailments occurring in every home where opium came into its own.

The uses of opium in self-medication paralleled and prefigured those of professional medical practice. Self-medication with opium, if anything, encompassed more than the professional spectrum of use. A particular example was the connection of opium use with drinking. Certainly the conjunction of opium and alcohol in popular usage was more extensive than its orthodox use. Opium was generally accepted as a medical remedy for the treatment of delirium tremens. But it was popularly used to counteract the effect of too much drink. In many industrial working-class areas, children's cordials containing opium were on sale in the pubs. The Morning Chronicle reporter found this to be the case in Ashton, and probably, he thought, in Manchester as well. It was customary to sell laudanum there also. In Liverpool in the 1850s much was sold by publicans during the cholera season, and in the fruit season in the summer, `It is the custom for the publicans to keep a supply of laudanum to add to the brandy....' The criminal usage of the drug which such proximity could lead to was recognized.32

This appears to have been a widespread popular means of controlling and counteracting excessive drinking. The number of cases where overdoses of opium were accidentally taken in these circumstances is some indication of this. A Manchester blacksmith took six drachms of laudanum while drunk; a Liverpool widow of `intemperate habits' was `accustomed to take a few drops of laudanum after indulging in drink' .33 These were only exceptional instances - in that they took too much and so their cases received publicity - of what seems to have been a common enough practice. Medical men were known to use this type of remedy on themselves after excessive drinking. How far such usage extended both above and within the working-class is impossible to estimate. This informal means of sobering up had its local variations - the adding of opiates directly to beer in the Fens, for instance. This practice was the origin of the `stimulant' working-class use of opium which much concerned outside observers in the 1830s and 1840s and which is discussed in Chapter 9.

How much opium was in fact being consumed, not just among the working class, but indeed at all levels of society in a situation of open availability? This is difficult to assess, for the available data on mortality and consumption have severe drawbacks.34 Many contemporary discussions used the statistics to support the argument that the use of opium was rising out of control. The belief in `stimulant' opium use among the industrial working class (to be discussed in Chapter 9) owed much to the picture presented through the figures.35 The detailed mortality data will be considered in Chapter 7 as part of the public health case. Certainly

deaths from opium were high (14o died from narcotic poisoning in 1868), and the level of accidental overdosing was notable, even though deaths by other violent means - suffocation, drowning - were always far more numerous. But there is less evidence of a steep overall increase in either mortality or consumption in the

first half of the century. The rate in 1840 of 5 per million population for narcotic poisoning deaths had risen to 6. t per million in 1863, not a startling increase, since the early figure was most likely an underestimate. Absolute import figures, too, were increasing.

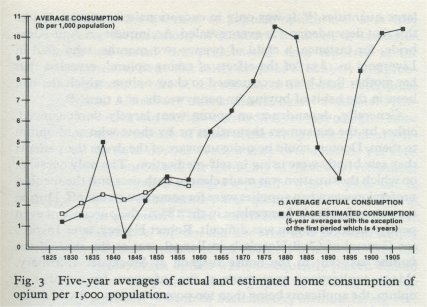

But home consumption figures per thousand population show a less steep progression than a simple comparison of import totals. Table 2 (p. 274) shows that in the 1 827-60 period home consumption varied between 1.3 and 3.6 lb. per thousand population. Figure 3 shows that in the same period the five-year average home consumption varied between a and 3.3 lb. per thousand population. Home consumption was rising, although not as swiftly or as astronomically as contemporaries believed.36

Certainly given the level of self-medication which prevailed, dependence or addiction among working people was likely to be common. No precise quantification can be given. A survey was conducted by Professor Robert Christison of Edinburgh and G. R. Mart, a Soho Square surgeon, in the early 1830s, but this was unique. The sample was small and unrepresentative, since only those whose dependence was obvious and well known were included. A total of twenty opium eaters were recorded. Of that number, seven of the thirteen females would be classified as working-class, two of the seven males .37 Knowledge of the extent of dependence is otherwise piecemeal. It can be estimated through the mortality rate. But of course not all overdose cases would have been working-class consumers, nor would all have been dependent on the drug.38

Patterns of use necessarily emerge haphazardly. Martha Pierce of Hughenden, a sixty-year-old lace-maker, a widow with eight children, while in prison in 1854, told the chaplain that she had `been used, for 4 years, last past, to take 5 pennyworth of laudanum per week. Can take 2 teaspoonfuls per day. States that great

numbers of women in her neighbourhood, and some men, take large quantities.'39 It was only in exceptional circumstances like this that dependence was ever revealed. An inquest on Ann Kirkbride, for instance, a child of twenty-two months, who died in Liverpool in 1854 `of the effects of taking opium',, revealed that

her mother `had been accustomed to chew opium, which she had been in the habit of buying by pennyworths at a time' .40

Generally, dependence on opium went largely unrecognized, either by the consumers themselves or by those who sold opium to them. Doctors could be quite unaware of the drugs the patients they saw briefly were using in self-medication. The only occasion on which the situation was made clear to both user and the medical profession was when supplies were for some reason cut off. During the cotton famine in Lancashire in the 1 860s, the purchase of even pennyworths of opium was difficult. Robert Harvey, later Inspector General of Civil Hospitals in Bengal, was at the time of the famine assistant to the house surgeon at Stockport Infirmary. `Many applications were made at the infirmary for supplies of opium, the applicants being then too poor to buy it ... I was much struck,' he later recalled, 'by the fact that the use of the drug was much more common than I had any idea of, and that habitual consumers of ten and fifteen grains a day seemed none the worse for it; and would never have been suspected of using it.' In Salford, customers who regularly took a teaspoonful of laudanum would come and beg for a dose in bad times when they had no money.41

Doctors who worked closely with the poor elsewhere also had their eyes opened about the extent of use and dependence. Dr Anstie, editor of the Practitioner, commented on the prevalence of opium taking among the poor of London. He had had this point brought home to him. `It has frequently happened to me to find

out, from the chance of a patient being brought under my notice in the wards of a hospital that such patient was a regular consumer, perhaps, of a drachm of laudanum, from that to two or three drachms per diem, the same doses have been used for years without any variation.' His comments on the habit were a realistic appraisal of why there was a large sale of opium to the working class. The consumers were `persons who would never think of narcotising themselves, anymore than they would be getting drunk; but who simply desire a relief from the pains of fatigue endured by an ill-fed, ill-housed body, and a harassed mind'.42

The official sources are, except in special instances like this, mostly silent on the question of popular opium use. It is easy enough, using the testimony of coroners' inquests, of accidental overdosing and casual `non-professional' sales reported in the medical journals, to write of it solely in terms of dangers and problems. The particular bias of the sources to an extent determines the conclusion. Alternative information is barely available. Pharmacists' day-books and workhouse medical records can give some indication, but the records of small corner shops where most purchases went on have not survived, if they ever existed. Yet even from the official sources and the testimony of those who remember some part of the system emerges a picture where opiate use in the early decades of the century was quite normal, where it was not in general a 'problem'. There were reasons for concern, as later chapters will indicate. Opium did not arise as a problem simply from the minds and outlook of the medical profession. But the framework within which opium was subsequently placed should not serve to erase the positive role it played in working-class life at this period. Robert Gibson in Manchester, manufacturing vermin killer, medicated lozenges (including morphine) and 'whole-

some sweetcakes'; opium lozenges given like sweets as a treat to a shopkeeper's child; a pub keeper sucking morphine lozenges for a sore throat - these are incidents which, slight in themselves, recall the time when opium was freely available and culturally sanctioned. Opium itself was the `opiate of the people'. Lack of access to orthodox medical care, the as yet unconsolidated nature of the medical profession and, in some areas, a positive hostility to professional medical treatment ensured the position it held in the popular culture of the time.

references

1. `Messrs Morson give up the retail', Chemist and Druggist, S7 (1900), p. 65o; A. Duckworth, `The rise of the pharmaceutical industry', ibid., 172 (1959), PP. 127-8; J. K. Crellin, `The growth of professionalism in nineteenth century British pharmacy', Medical History, r r (1967), pp. 215-27.

2. All these wholesale druggists gave evidence to the First Select Committee Enquiry into Adulteration in 1854.

3. Society of Apothecaries, Laboratory mixture and process book, 186872, Guildhall Library Ms. 8277.

4. W. Allen and Co., Inventories of drugs, 1810-11, Pharmaceutical Society Ms. 22008. There is information about prices and preparations also in Allen and Hanbury, Price book of drugs, 1846-66, Pharmaceutical Society Ms. 22006; and Sales Ledger of a wholesale druggist, 184758, Wellcome Library Ms. 833.

5. A. Duckworth, op. cit., pp. 127-8; R. S. Roberts, `The early history of the import of drugs into Britain', pp. 165-83, in F. N. L. Poynter, ed., The Evolution of Pharmacy in Britain (London, Pitman, 1965).

6. Dicey and Sutton, Drug invoice, 1838, Pharmaceutical Society Ms.12177, shows Thomas Harvey of Lees buying drugs, including opium, from Dicey and Sutton in Bow Church Yard, London.

7. W. Kemp and Son, Monthly Prick List of Specialities (Homcastle, no publisher, 1890); G. Meggeson, Price list of medicated lozenges, c. 1850, Pharmaceutical Society Ms. 1232'-4.

8. D. N. Phear, `Thomas Dover, 1662-1742. Physician, privateering captain, and inventor of Dover's Powder', Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, 9 (1954), PP. 139-56.

9. Public Record Office, Home Office papers, H.O. 45, 7531, 1865: Letter from Edward Foster to Sir George Grey.

10. P.P. 1857, X I I (sess. 2) : Report from the Select Committee of the House of Lords on the Sale of Poisons etc. Bill, q. 852. There is also evidence of this type of informal restriction in P.P. 1834, V III : Report from the Select Committee on Inquiry into Drunkenness, q. 1793; British Medical Journal, r (1868), p. 637.

11. `Alleged child poisoning', Pharmaceutical journal, 3rd ser. 6 (18756), pp. 596-7; R. C. Ellis, `Short notes of a fatal case of poisoning by opium', Lancet, 2 (1863), p. 126. Both reports show how shops selling opiates were kept by factory workers' wives.

12. Prescription book of a Scarborough chemist, c. 1875, Wellcome Library Ms. 3994.

13. Morning Chronicle, 15 November 1849; Home Office papers, H.O. 45, 5347, 1854: Letter from Hull coroner to Home Secretary.

14. `Poison shops', Lancet, r (1858), p. 486.

15. W. Bateman, Magnacopia (London, John Churchill, 1839).

16. Clay and Abraham, Stock list of a Liverpool shop, Pharmaceutical Society Ms. 40619. A Peterborough shop had sixteen opium preparations in stock: R. Bright, Memorandum of the valuation of stock taken 1 November 1854 at 29 Broad Street, Peterborough, Pharmaceutical Society Ms. 9987.

17. Reminiscences date back to the early I900s, but it can be assumed that practices would have changed little over the previous fifty years. Indeed, where procedures can be directly compared, there seems to be no difference. This section is based on information from H. Cook, E. W. Frost, W. E. Hollows and other retired pharmacists. See also P.P. 1843, XV: Children's Employment Commission: Second Report of the Commissioners on Trade and Manufactures, Appendix to the Second Report, part 2, q. 30

18. S. Flood, `On the power, nature and evil of popular medical superstition', Lancet, 2 (1845), P. 203.

19. T. Hardy, The Trumpet-Major (London, Smith, Elder and Co. 188o), p. 274. I am grateful to Meta Zimmeck for this reference.

20. P.P. 1857: Select Committee on Sale of Poisons ..., op. cit., 1, 852.

21. `Register of the sales of opium and laudanum in Stockton-on-Tees', Pharmaceutical journal, 17 (1857-8), p. x65.

22. W. Armitage, Chemist's prescription book, 1847-99, Wellcome Library Ms. 978.

23. `Memories of the "jug and bottle" trade. By an octogenarian', Chemist and Druggist, x67 (1957), pp. 164-5; `Sale of poisons', Lancet, x (1870), p. 92; the Hoxton reminiscence was collected by Anna Davin.

24. This section is again based partly on pharmacists' memories and also on `Poisoning' by laudanum', British Medical journal, 2 (1878), p. 889; P.P. 1857: Select Committee on Sale of Poisons..., op. cit., q. 1195; 'Suicides by laudanum', Pharmaceutical journal, new ser. 3, 1861-2, pp. 628-9; `Opium as a daily transaction', ibid., 207 (19711), p. 215.

25. J. Parkinson, Medical Admonitions to Families, Respecting the Preservation of Health, and the Treatment of the Sick (London, H. D. Symonds, I801), p. 157.

26. W. Rayner, Workhouse medical officers' order book, 1840, Stockport Local History collection, Ms. B/EE/3/211, describes how opium pills were given to some workhouse inmates at night.

27. G. H. Rimmington, retired pharmacist, personal communication,1975

28. Pannell's Reference Book for Home and Office (London, Granville Press, 19o6), pp. 480-81, and J. Parkinson, op. cit., pp. 326-7, both describe this usage.

29. For example the chemists' recipe book of Mr Lloyd Thomas (1879i goo), which contains a recipe for 'pauverine' cough mixture, a cheap variety especially for poor customers. I am grateful to the late Mr G. Lloyd Thomas for lending me his father's book.

30. `Poisoning by laudanum', Pharmaceutical journal, 3rd ser. 10 (18798o), p. 599; P.P. 1839, XXXVIII:Returns from the Coroners of England and Wales of All Inquisitions Held by Them During the Years 1837 and x838, in Cases where Death was Found by Verdict of Jury to Have Been Caused by Poison, p. 431. See also `On toothach' (sic), The Doctor, z (1833-4), P. 206; T. L. Brunton, `The influence of stimulants and narcotics on health', pp. 183-267 in M. Morris, ed., The Book of Health (London, Cassell, 1883).

3I. W. Buchan, Domestic Medicine (London, A. Strahan, 18th edn 1803), PP- 294, 297, 304, 335, 337, 361, 399, 410-11, 415, 660, 663-4, 670, 675, 685.

32. Morning Chronicle, 1 November 1849; P.P. 1857, XII: Report ... on the Sale of Poisons, op. cit., q. 276.

33. `Poisoning by opium and gin...', Lancet, 1(1862), p. 326; P.P. 1839, XXXV III: Returns from the Coroners..., op. cit., p. 435; The Times, 5 January 1870; `The sale of laudanum', British Medical journal, x (1891), PP. 363-4.

34. The drawbacks of mortality data are discussed in B. W. Benson, `The nineteenth century British mortality statistics: towards an assessment of their accuracy', Bulletin of the Society for the Social History of Medicine, 21 (1977) PP. 5-13.

35. J. Jeffreys, `Observations on the improper use of opium in England', Lancet, r (1840-4r), pp. 382-3; and `The Sale of Poisons', Pharmaceutical Journal, 9 (1850), PP. 163, 205-10, 590-91.

36. These data are discussed in more detail in V. Berridge and N. Rawson, `Opiate use and legislative control: a nineteenth century case study', Social Science and Medicine, 13A (1979) PP. 351-63. The establishment of the domestic morphine industry should also be taken into account in assessing the rise in home consumption (see Chapter 12).

37. R. Christison, `On the effects of opium eating on health and longevity', Lancet, r (1832), pp. 614-17; G. R. Mart, `Effects of the practice of opium eating', ibid., r (1832), pp. 712-13; see also V. Berridge, `Opium eating and life insurance', British Journal of Addiction, 72 (1977) PP. 371-7.

38. Annual Reports of the Registrar General (London, H.M.S.O., 1867), pp. 176-9. For an example of one regular user who did exceed the limit of his tolerance by mistake, see Inquisition at Whitechapel on Samuel Linistram, 28 November 1820, Middlesex Record Office Ms. MJ/SPC E 1130.

39. `Prison chaplain's register. 1854', Buckinghamshire Record Office, MSQ/AG/27.

40. Reynolds's Newspaper, 1 October 1854. For other examples, see `The estate of pauperism and laudanum-drinking', Lancet, 1 (1878), p. 325; letter from J. D. Phillips, British Medical Journal, 1 (1884), p. 885.

41. P.P. 1894, LXI. Minutes of Evidence of the Royal Commission on Opium, q. 3387.

42. F. E. Anstie, Stimulants and Narcotics (London, Macmillan, 1864), P. 149.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|