12 Morphine and Its Hypodermic Use

| Books - Opium and the People |

Drug Abuse

12

Morphine and Its Hypodermic Use

Professional involvement in the question of opium use was not limited to the sale and availability of the drug. In the last few decades of the century doctors in particular became more closely involved in the way it was administered and used. Popular use of opium continued and the sale of 'non-medical' patent remedies was high, as the previous chapter has demonstrated. But the increased medical use of a new form of opium, its alkaloid, morphine, brought a closer medical concern both with hypodermic morphine-injecting addicts and, through them, with delineating new medical views of opium eating based on ideas of disease and treatment.1 It is this involvement and the advent of the new hypodermic technology of administration which are considered in the following two chapters.

Although medical concern about hypodermic morphine use was only a feature of the last quarter of the nineteenth century, the isolation of morphinn as the active principle of opium was made early in the century. Responsibility has traditionally been assigned to three men .2 In 1803, Derosne, a French manufacturing chemist, produced a salt, his 'sel narcotique de Derosne'; this was the substance later known as narcotise, but it also contained some morphine. A year later, Armand Seguin read a paper before the Institut de France in which de described his isolation of the active principle of opium. His communication 'Sur l'opium' was not published until 1814. Meanwhile Frederick William Serturner, a pharmacist of Einbeck in Hanover, working on Derosne's salt, had investigated the composition of opium more accurately than anyone before. He isolated a white crystalline substance which he found to be more powerful than opium. Calling the new substance `morphium' after Morpheus, the god of sleep, he published details in the journal der Pharmazie, in 1 805, 1 806 and 1811, although the significance of his breakthrough was not appreciated until he wrote again on the subject in 1816. In 1831, the Institut de France awarded him a substantial prize for `having opened the way to important medical discoveries by his isolation of morphine and his exposition of its character'.

The isolation of morphine was part of a general systematization of remedies_ and discovery of alkaloids in line with the growth of toxicology as a science. Quinine, caffeine and strychnine were all isolated shortly after morphine. Other opium alkaloids were also discovered - narceine by Pelletier in 1832, and codeine by Robiquet in 1821 while examining a new process for obtaining morphine suggested by Dr William Gregory of Edinburgh. Morphine (sometimes still referred to as 'morphium') first became known in Britain in the early 1820s, in particular after publication of the English translation of Magendie's Formulary for the Preparation and Mode of Employing Several New Remedies.3

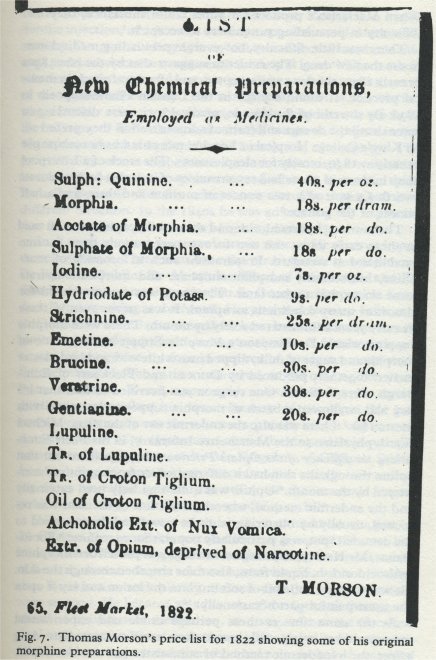

Morphine was manufactured on a commercial scale quite early on. It was produced by Thomas Morson, later a founder of the Pharmaceutical Society and one of its presidents. He had originally gone to Paris to train as a surgeon, and had picked up his pharmaceutical knowledge there. Morson took over a retail business in Farringdon Street on his return to England; and it was in the parlour behind the shop that morphine and other drugs were produced. Morson's first commercial morphine was produced in 1821, at about the time when Merck of Darmstadt also began production of wholesale morphine. The English variety sold at eighteen shillings per drachm, with the acetate and sulphate also selling at the same rate.4 Macfarlan and Company of Edinburgh began to manufacture the alkaloid in the early 1830s, when Dr William Gregory (the son of James Gregory, of Gregory's Powder) devised a process for the production of morphia muriate. British opium collected by Mr Young in his initial experiments was used. The drug was later purified and more exact processes devised. In the early years of morphine production, Macfarlan's received opium from the London wholesale houses and returned them the muriate. The drug was still brown and formed a brown solution, for the process then used did not abstract the resin of colouring matter.

When Macfarlan's produced a purer white substance, they had difficulty in persuading purchasers to accept it.5

There was little difficulty, however, in persuading medical men to use the new drug. The evidence suggests that by the late 1830s or early 1840s the drug was accepted, and often preferred, in medical practice. It found a place in the London Pharmacopoeia in 1836. By the end of the decade, medical men were discussing in some detail the dosage and form of administration they preferred. In King's College Hospital in London morphia was in routine use as early as 1840, mostly for sleeplessness. The stock of a Liverpool shop in the mid 1 840s had seven ounces of morphia hydrochlorate (worth £3 4s.I0d.), two ounces of muriate and three and a half ounces of the acetate.6

The muriate, hydrochloride and acetate of morphia were all used in these early days; the two former preparations later became established as standard. Preparations such as bromide 0f morphine, bimeconate, morphine sulphate and morphine tartrate came on to the market later. The drug was recommended for almost as many conditions as opium. It was never even in these its early years administered solely by mouth. There were morphia suppositories - Dr Simpson's Morphia Suppositories, made of morphia and sugar of milk, dipped into white wax and lard plaster melted together, produced by Duncan and Flockhart of Edinburgh, were available. One surgeon was horrified to find that his dog had swallowed a batch of morphia suppositories made with mutton fat.7 There was also the endermic use of the drug. Michael Ward, physician to the Manchester Infirmary, in his Facts Establishing the Efficacy of the Opiate Friction (1809), pointed out that opium through the skin had a different effect from opium administered by the mouth." Opium was quite regularly used externally and the endermic method, whereby a section of the skin was removed, usually by blistering, and the powdered drug applied to the denuded spot, was particularly popular for morphine.9 For instance, Mr Hanley, in Islington in 1865, was prescribed morphine hydrochloride in liquid form, also to be absorbed through the skin.

He was to `dip a little bit of soft lint into the lotion and lay it upon the most painful part occasionally'.10

At the same time as these perhaps crude and experimental attempts were being made to produce a more immediate drug effect, the hypodermic method of administration was developed.

Intravenous administration had a much longer history than hypodermic injection, which was a development of the mid-nineteenth century. Drugs, including opium, had been injected into both animals and man since the seventeenth century at least." The method was desultorily used, and interest in it did not revive until the end of the eighteenth century. The new practice then of inoculation was a further stage in the evolution of the hypodermic method. Dr Lafargue of St Emilion, in a series of letters and papers in the 1830s, described his method for the inoculation of morphine. The point of a lancet was dipped into a solution of morphine, inserted horizontally beneath the epidermis, and allowed to remain there for a few seconds. But his researches eventually developed in a different direction. In the 1840s he was advocating the implantation of medicated pellets with a darning needle.12

Such methods were in a sense `curtain raisers' for the true hypodermic method. Three men have the credit for its development: Dr Rynd of Dublin, Dr Alexander Wood of Edinburgh, and Dr Charles Hunter, a house surgeon at St George's Hospital in London. Rynd, working at the Meath Hospital and County Infirmary in Dublin in the 1840s, described how he had cured a female patient of neuralgia by introducing a solution of fifteen grains of acetate of morphine by four punctures of `an instrument made for the purpose'. The patient recovered, as did others. Ten years later, Alexander Wood, apparently unaware of Rynd's earlier publication, described his own treatment of neuralgia. He had made several attempts to introduce morphia by means of puncture needles, and, in 1853, `1 procured one of the elegant little syringes constructed for the purpose by Mr Ferguson of Giltspur Street, London'. Experiments with the muriate on an elderly lady suffering from neuralgia proved the utility of the method. Papers -published in 1855 and 1858 gave publicity to it.13

However, it was the use to which the new method was put by Dr Charles Hunter which revealed its true potential. Hunter had initially used Wood's hypodermic method purely as a local means of treating disease. Sepsis set in; Hunter was forced to use other sites for injection and quickly realized that the results obtained were as good. He became an advocate of the `general therapeutic effect' of hypodermic medication, as distinct from the `localization supported by Woods and others. 14 What he called his 'ipodermic (and later hypodermic) method led to a period of sustained and acrimonious debate between Wood and Hunter. Although the former had, in his 1855 paper, described the general effects of the method, it was Hunter who developed this aspect, while Wood clung tenuously to the belief that it was a local means of treating a local affection. The controversy created such interest that the Royal Medical and Chirurgical Society, to which Hunter had read a paper in 1865, appointed a committee to look into the question of hypodermic medication. Its report, published in 1867, came down strongly on Hunter's side. It concluded that `no difference had been observed in the effects of a drug subcutaneously injected, whether it be introduced near to, or at a distance from the part affected'. Belief in the localization theory lingered on, but Hunter's method was more generally accepted.15

He had recommended the hypodermic use of morphine for its certainty in action and for more rapid absorption. Morphia injections he advocated as of benefit in melancholia, mania and delirium tremens, where it did away with the necessity for restraint. It was useful for chorea, puerperal convulsions, peritonitis, ague, uterine pain, tetanus, rheumatism and incurable diseases such as cancer. There were others in the medical profession as enthusiastic, but no one perhaps more so than Dr Francis Anstie. Anstie was editor of the Practitioner from its foundation in 1868 until his death in 1873 and his concern about working-class and opium use has already been mentioned. His particular interests lay in the areas of alcohol and neuralgia (on which he wrote sections for Dr Russell Reynolds's System of Medicine) as well as with opiates. His determined advocacy of new and apparently better methods was representative of that section of the medical profession which wished to develop more scientific, more `professional' means of treatment, to elevate the status and develop the expertise of doctors as a body. In his opening remarks in the first issue of the new journal, he drew attention to the lack of proper analysis of remedies and the isolation of more exact means of treating

disease.16

Anstie was correct in his belief that if the profession was to establish itself as such, and remain superior to and distinct from the mass of quacks, herbalists, patent-medicine vendors and manufacturers, it had to develop its own exclusive expertise, as well as a more scientific and exact means of treating disease. It was significant, then, that Anstie's warmest praise was reserved in the early years of the journal for the hypodermic method, and for its use with morphia in particular. His article of 1868, `The hypodermic injection of remedies', marked the high point of unquestioning acceptance - `of danger', he wrote

there is absolutely none ... The advantages of the hypodermic injection of morphia over its administration by the mouth are immense ... the majority of the unpleasant symptoms which opiates can produce are entirely absent ... it is certainly the fact that there is far less tendency with hypodermic than with gastric medication to rapid and large increase of the dose, when morphia is used for a long time together.17

In this, Anstie was at one with the Committee on Hypodermic Injection which had recommended the method specifically for confirmed opium eaters, since smaller doses than those previously taken by mouth were requisite. In the late 1860s the group of `new men' who formed a distinct medical group round Anstie were enthusiastic about the `new remedy', hypodermic morphine. Clifford Allbutt, later Regius Professor of Physic at Cambridge and a noted'writer on addiction, recommended the use of morphia to treat heart disease, although opium was generally forbidden in that type of condition. He was also using it to treat dyspepsia and 'hysteria'. There was much interest in and excitement about the new method. Hypodermic injections of morphia and aconite were reported in use for convulsions; there were morphia injections for chorea. Dr John Constable described how he had cured a case of hiccoughs by the subcutaneous method.''

Doctors were engaged in a more complex process than they realized. Advancing the barriers of scientific discovery, analysing and utilizing new and apparently safer or more reliable methods, they were at the same time involved in the process of establishing their own professional expertise at the expense of `non-scientific', harmful or unreliable remedies. Enthusiasm for hypodermic morphine was generally accompanied by a denigration of opium; the 'medical' remedy was seen as more effective. But the profession was also creating its own problem by the advocacy of hypodermic usage and it was not long before the first warnings of the increased incidence of addiction began to appear. The most influential in English medical circles was that of Clifford Allbutt in 1870.

Allbutt expressed the progress of his doubts in the Practitioner, in particular the case of nine of his patients who seemed as far from cure as ever despite the incessant and prolonged use of hypodermic morphia. `Gradually ... the conviction began to force itself upon my notice, that injections of morphia, though free from the ordinary evils of opium eating, might, nevertheless, create the same artificial want and gain credit for assuaging a restlessness and depression of which it was itself the cause.""' He was not the first to draw attention to this attendant possibility, and warnings had been published as early as 1864.20 Allbutt's warning was initially not generally accepted in the profession .21 Even Anstie himself was unwilling to abandon the benefits of morphia because of the danger of addiction. He was in favour of a form of maintenance prescribing, of controlled morphine addiction on a lower dosage: `Granting fully that we have ... a fully formed morphia-habit, difficult or impossible to abandon, it does not appear that this is any evil, under the circumstances.'22 In hospital and general practice, the 1870s marked no particular dividing line; doctors still wrote enthusiastically to the medical journals of the good results they had obtained by using hypodermic morphine.

Yet there was a dawning realization that morphine injections on a repeated basis could have attendant dangers. Reports of the utility of the method were tinged with a certain wariness, in. particular as details of the abuse of the drug on the continent and in America began to filter through. It was on the continent, too, that concern and a more exact definition of morphine addiction crystallized. Dr E. Levinstein of Berlin published in 1877 Die Morphiumsucht nach Eigenen Beobachtungen, translated into English the following year as Morbid Craving for Morphia (1878).23 Levinstein's work was the first all-embracing analysis of

the condition of morphine addiction to reach the English medical profession. (Dr Calvet had published an Essai sur le Morphinisme aigu et chronique in Paris in 1876 but this appears to have made no impact in Britain.) Levinstein's book was based on his own experiences in the institutional treatment of addiction in Berlin,

and was instrumental in defining 'morphinism' as a separate condition or disease. As Levinstein himself remarked, others had seen it as 'Morphinismus', 'Morphia-delirium' or `Morphia evil'. He was the first to define it as a disease with a similarity to dipsomania, although not a mental illness. Levinstein still saw addiction as a human passion `such as smoking, gambling, greediness for profit, sexual excesses, etc....'.

Disease isease theories were developing in many areas at this time; the elaboration of disease theories of narcotic addiction and the importance of Levinstein's work in this respect will be discussed in the following chapter. What was also important for the English medical profession, however, apart from the ideas contained in the book, was the interest in the subject which it stimulated. The 1878 book was widely reviewed and discussed. In 1879 came a request from Dr H. H. Kane of New York, anxious for information about British doctors' use of hypodermic morphia. He was particularly interested to learn if any cases of opium habit had been contracted in this way. His book, The Hypodermic Injection of Morphia. Its History, Advantages and Dangers (1880), was based on the experience of British as well as American physicians.24 The work of another German expert, Dr H. Obersteiner, was published in the newly established Brain; and continental doctors were crowding thick and fast into this newly opened medical field .2b British doctors themselves were increasingly aware of morphine addiction. Case histories which had appeared sporadically in the medical press in the 1870s were, by the end of the decade, greatly increased in quantity and prominence.28

A report on chloral produced by the Clinical Society of London in 1880 drew attention to the possibility of misuse not only of that drug, but of narcotics in general. The committee's report was in ha neutral as to the supposed deleterious effects of the long-contlnued use of chloral. But its publication was the occasion for comment on the apparent increase in addiction to all forms of narcotics, chlorodyne and morphine in particular. The dangers of hypodermic use were highlighted; there was a contribution in The Times from an addict who had re-used his original morphine prescription again and again .27 The death of Mr Edward Amphlett, 'a nephew of Baron Amphlett and assistant surgeon at Charing Cross Hospital, who was revealed at the inquest in 1880 to have been accustomed for years to take chloral and morphia, confirmed fears of increased use.28 In the Commons, Lord Randolph Churchill significantly compared Gladstone's oratory on Home Rule to 'the taking of morphia! The sensations ... are transcendent; but the recovery is bitter beyond all experience . . . '29

Churchill's views were echoed in the medical presentation of morphine addiction: Dr Seymour Sharkey wrote on the treatment of 'morphia habitues', citing a case of his, a city manager, whose business gave him the facilities for getting as much morphia as he pleased and who had used the drug over a seventeen year period. Sharkey later expanded, and to a certain extent sensationalized, his views in -an article on 'Morphinomania' in the Nineteenth Century in 1 $87.30 In 11889, Dr Foot led an extensive discussion of morphinism in a meeting of the Irish Royal Academy of Medicine. Ascribing a five-fold origin to the habit - for relief of pain, insomnia, melancholia, curiosity and imitation - he recognized that the possibility of cure was dependent on the duration of the habit, the persistence or not of the exciting cause and the physical or nervous constitution of the patient-31

In the 1880s doctors were as busy elaborating the dimensions of morphinism and delineating the outlines of the typical morphia habitue as they had once been in analysing those conditions where hypodermic usage was invaluable. Case histories of morphine addicts to a great extent replaced studies of morphine use in the medical journals. Continental and American influence was still noticeable. Dr Albrecht Erlenmeyer's work on morphine addiction, published originally in Germany in 1879, became known in its English version at the end of the 1880s.$2 The most persistent `outside' influence on British medical thinking on morphine addiction towards the end of the century was the work of Dr Oscar Jennings. Jennings, an ex-morphine addict himself, was English, but the bulk of his working experience, and case histories, came from France. His ideas on the treatment of addiction led him into much controversy, yet the sheer volume of his published work - in books like On the Cure of the Morphia Habit (1890), The Morphia Habit and its Voluntary Renunciation (1909), The Reeducation of Self-control in the Treatment of the Morphia Habit (1909), numerous articles and contributions to journals and conferences - made his name a force to be reckoned with.33

Well-defined views were held on the origin and incidence of the disease. Most accepted a stereotype whereby morphine addiction was vastly increased and increasing, where many addicts had acquired the habit through original lax medical prescription and through the eventual self-administration of the drug. Women

were said to be peculiarly susceptible to morphinism; and not a few doctors recognized that the medical profession itself was also highly -prone to addiction.`Morphinomania,' Dr H. C. Drury told the medical section of the Irish Royal Academy in March 1899, `is increasing with terrible rapidity and spreading with fearful swiftness.' The `recourse to injections under the' skin' was accordmicing to the Lancet in 1882 `becoming general', while Dr S. A. K. Strahan, physician to the Northampton County Asylum, agreed. The `vicious habit' was `undoubtedly a growing disease'." The greatly increased general number of case histories and comments on the subject gag substance to a feeling that an epidemic was threatening.

Medical susceptibility to morphine addiction was established. Drury, for instance, thought that morphinomania was particularly prevalent among the medical profession, and a standard medical text like Sir William Osler's The Principles and Practice of Medicine (1894) saw doctors forming one of the main classes of addicts .35 Conventional ideas about the weakness of the female sex were-al-so soon linked with the spread of morphine use. As the Lancet put it, `Given a member of the weaker sex of the upper or middle class, enfeebled by a long illness, but selfishly fond of pleasure, and determined to purchase it at any cost, there are the syringe, the bottle, and the measure invitingly to hand, and all so small as to be easily concealed, even from the eye of prying domestics.' Most medical writings on the subject were united in seeing women pecukarly at risk .36 Female susceptibility was linked with the iatrogenic origin of most morphine addiction, and also with the idea of selfmedication. The apparent willingness of practitioners to hand over control of injection either to a nurse or to the patient herself was stressed, and this usurpation of the professional role of the doctor was a continuing theme in discussions of morphine addiction. Dr Macnaughton Jones told the British Gynaecological Society in 1895 that no patient should be allowed to inject herself. Levinsein, too, attributed the spread of the disease to the carelessness bf medical menrin allowing patients to inject .37

These questions of the amount of increased usage of the drug (and its hypodermic usage in particular), the numbers of addicts at this period, and their social class and gender badly need more extended examination if the reality of the picture presented in the medical journals is to be assessed. In certain respects, it is clear that the medical profession was myopically exaggerating the dimensons of a situation it had helped create. How much morphine was actually being used in England at this time is difficult to estimate. To arrive at any picture of overall home consumption of morphine is almost impossible. Duty on imported opium ceased in 186o and no actual `home consumption' figures are available after that date. Estimates of home consumption of all narcotics, including morphine, after 186o can only be obtained by subtracting the amount exported from that imported. This is an uncertain method of assessing anything but the most general trends in overall consumption. These moved upward for the first fifteen years after the abolition of duty in 1 860, but decreased between the mid 1 870s and the 1890s.38 General trends reveal little about the production and home consumption of domestic morphine. Morphine was not separately incorporated into the trade statistics until 1911 (and then largely because of the demands of the 1911 Hague Convention for the collection and production of morphine and cocaine statistics). Until this date, it was included in the `drugs, unenumerated' section and measured only in terms of financial value. The trade statistics are of little direct value in an examination of morphine production. Yet there was a widening post-186o gap between imports and exports. This strongly suggests that much of the imported drug was being used to make morphine, since even the best Turkey opium would yield only around 10 per cent morphine. The general trend of home consumption also bore a strong relation to the business cycle. The connection with the onset of the `Great Depression' of the 1870s was particularly marked, and consumption appears to have declined. Fluctuations like this again suggest a connection with the overall fortunes of the morphine industry.

Yet how much morphine Thomas Morson and Son, J. and F. Macfarlan and T. and H. Smith in Edinburgh were actually producing and exporting at this time remains uncertain. Wholesale business records show that morphine was popular, but no more so than other opium preparations and derivatives. The Society of Apothecaries for instance, one of the major wholesaling organizations, was producing large quantities of morphine preparations in the 1860s, but fewer a decade later. Yet the importance of morphine should perhaps not be overemphasized or singled out. The Society was still making large quantities of other opium preparations, too - it had twenty-six on its laboratory list in 1871. There were thirteen batches of paregoric, ten of laudanum, nine of powdered opium, and also of gall and opium ointment. Morphine at this wholesale level was only a part of the whole spectrum of

opiate use. 39

This is also the picture which emerges of 'grass-roots' usage in the second half of the century. In everyday medical and pharmaceutical practice morphine was in increased use. But there was nothing like the epidemic of rising consumption which the medical accounts suggested. Nor was everyday medical practice a matter of hypodermic injection alone. Morphine was used in many varied forms and there is little evidence 0f extensive self-administration of the hypodermic syringe. The evidence of prescription books shows that morphine was in quite regular use in the second half of the century, but that dispensing 0f the drug was not rapidly escalating. An Islington pharmacist, for instance, dispensed fiftyfive morphine prescriptions in 1855 (from a total 0f 378), or 14.5 per cent of the whole number of opium-based remedies. By 1865, the number had risen t0 sixty-four (out of 316), or 20 per cent. But figures in 1875 and 1885 were lower.40 Re-dispensing must be a matter of conjecture, since chemists noted only new prescriptions and did not re-enter a copy each time an old prescription was dispensed. Clearly, however, the picture of morphine prescribing at the level of general practice differed from the conventional stereotype. Doctors were likely to administer hypodermic injection themselves either in the surgery or on home visits. Yet if the self-injection which the medical accounts postulated were reality, some of it would have come to light through the dispensing of doctors' prescriptions by pharmacists. There is little sign of it. The poisons register for an Eastbourne pharmacist's practice, giving details of transactions under the Pharmacy Act in the 1880s and early 1890s, shows entries for morphia and ipecacuanha lozenges for cough, but only one entry in a six-year period between 1887 and 1893 for sol. morph. hypo, or hypodermic morphia.41 Nevertheless cases where the hypodermic drug was recklessly prescribed are not hard t0 find. Alfred Allan, given hypodermic morphia `very frequently' in King's College Hospital, was discharged in July 1870, partly at his own wish, partly because the `Sisters got tired of him'.42

Even quite limited administration of the drug in this way, in unwise quantities or on an extended basis, could have resulted in a serious escalation of addict numbers. But there is little evidence that there were large numbers of morphine addicts in the late nineteenth century. One surprising omission in the welter of discussions on treatment methods, the origin of ' addiction and the characteristics of the addict was any serious consideration of how many of them there really were. It is only through examination of numbers of addicts admitted for treatment that some estimate can be made. An inebriates' home or a lunatic asylum were the two possibilities, and clearly only those whose habit was out of control would be admitted there. As Dr Robert Armstrong-Jones pointed out in 19o2, it was difficult on that basis to calculate how large the class of addicts really was, since `only the repentant sinner visits the consulting room'. Repentance must have been limited; for the numbers of admitted addicts were always very small. Jones himself reported eight admitted to the Claybury Asylum by 19o2 (within an unspecified period). Four of these were taking morphia hypodermically and one by mouth; the others took opium in various forms. At Bethlem Royal Hospital, few addicts were admitted. There were only nine cases between 1857 and 1893, two of these taking morphia.43 More cases were admitted to inebriates' homes. The Dalrymple Home at Rickmansworth took in addicts as well as alcoholics. Between 1883 and 1914, one hundred and seventeen drug cases had been admitted. Forty-six of these were taking morphia and fifteen both morphia and cocaine, a rate of admission of approximately two addicts a year .44

There were few signs of hypodermic usage of epidemic proportions here. Dr Armstrong-Jones was of the opinion that, for every case admitted to an asylum, there were probably scores outside with the habit whose mental and moral state was on the borderline of insanity. Yet he gave no evidence to support his assertion; and the low level of admissions, if not a guide to the general morphine addict population, at least indicated that only a small number were unable to lead some form of active life. Nor did the `female' emphasis in medical writing bear much relation to reality. Prescription books show that as many men as women were initially prescribed morphine (although this does not take into account the possible sex bias of re-dispensing). Morphine was undoubtedly popular in the treatment of specifically female complaints - for period pains, in pregnancy and during labour - and also for those ailments such as neuralgia, sleeplessness and `nerves' in general, which were considered to have a hysterical origin and so to be particularly common among female patients. There were wellknown female addicts like G. B. Shaw's actress friend Janet Achurch.45 Yet Jones's own case histories of 1902 were evenly divided between male and female; and whereas three 0f the four males used hypodermic morphia, only one 0f the females did so. The morphia cases admitted t0 Bethlem were all male.

The identifiable hypodermic morphine-using addict population at this date in fact appears to have had a medical or professional middle-class bias. There was n0 morphine-using drug sub-culture to parallel the beginnings 0f self-conscious recreational use of other drugs like cannabis and cocaine described in Chapter 16. Like the disease theory formulated to encompass addiction, the focus of morphine injection was very much a professional one. Virgil Eaton, in a study 0f opiate dispensing in Boston in the late 1880s, found the lowest proportion of morphine dispensed in the poorer quarters of the town. In England, too, morphia was always the more expensive drug and opportunities for addiction more easily available to better-off patients 46 There undoubtedly was addiction t0 hypodermic morphine; and from this time forward hypodermic use of the drug was, in medical eyes, the major part of the `problem' of opium use. Nevertheless part of the contemporary medical stereotype of the incidence and nature of the practice remains unproven. It is probable that, in numerical terms alone, morphine addicts bore no comparison to those dependent on opium. Much opiate consumption had always been outside the medical ambit of control, whereas morphine had always been primarily a `medical' drug. The profession, by its enthusiastic advocacy of a new and more `scientific' remedy and method, had itself contributed to an increase in addiction. The new technology of morphine use - the hypodermic method - did indeed create new objective problems in the use of the drug. The drug effect was more immediate, and smaller doses had a greater effect. But the profession showed a clear social bias in singling out this form of usage when there were still far larger numbers of consumers taking oral, opium. The quite small numbers of morphine addicts who happened to be obvious to the profession assumed the dimensions of a pressing problem - at a time when, as general consumption and mortality data indicate, usage and addiction to opium in general was tending to decline, not increase.

References

1. G. Sonnedecker, `Emergence of the concept of opiate addiction', Journal Mondiale Pharmacie, No. 3 (1962) pp. 275.90 and No. I (1963), pp. 27-34, deals with the emergence of the use of hypodermic morphine, but the articles are marred by an automatic acceptance of a `problem' framework deriving closely from current concerns.

2. Details of the process of discovery are in W. R. Bett, `The discovery of morphine', Chemist and Druggist, 162 (1954), pp. 63-4; J. Grier, A History of Pharmacy (London, Pharmaceutical Press, 1937) P. 93; AC. Wootton, Chronicles of Pharmacy, op. Cit., p. 244.

3. For an early notice of it, see 'Morphia, or morphine', Lancet, 1 (18223), pp. 67-8

4. `Messrs Morson give up the retail', Chemist and Druggist, 57 (1900), p. 650; A. Duckworth, `The rise of the pharmaceutical industry', ibid., 172 (1959), R 128; `Letter about the manufacture of morphine', Pharmaceutical Journal, 4th ser. 5 (1897), p. i9; T. Morson, `List of new chemical preparations, 1822', Pharmaceutical Society Pamphlet 8745.

5. W. Bett, op. cit., pp. 63-4; W. Gregory, `On a process for preparing economically the muriate 0f morphia', Edinburgh Medical and Surgical Journal, 3S (1831), PP- 331-8.

6. Examples of the early use and availability of the drug are in `Professor Brande on vegetable chemistry', Lancet, 2 (1827-8), pp. 389-90; King's College Hospital case notes, op. cit., 1840; Clay and Abraham, `Stock of a Liverpool shop', 1845 Pharmaceutical Society Ms. 40619; W. Bateman, Magnacopia, op. cit., pp. 33-4.

7. 'Dr Simpson's morphia suppositories', Medical Times and Gazette, new ser. 14 (1857), p. 141; 'Apomorphia', Lancet, r (1883), P. 577.

8. M. Ward, op. cit., p. vii; see also the standard article on the development of the hypodermic method, N. Howard-Jones, `A critical study of the origins and early development 0f hypodermic medication', journalof the History of Medicine, 2 (1947), PP. 201-49.

9. Review of Dr Ahrenson's book, British and Foreign Medical Review, S (1838), P. 348.

10. Islington prescription book, op. cit., 1865 entry.

11. Details of experiments by Christopher Wren are given in D. I. Macht, `The history of intravenous and subcutaneous administration of drugs', Journal of the American Medical Association, 1916, p. 857.

12. M. Martin-Solon, `Review of a report on the inoculation of morphine, etc. proposed by Dr Lafargue', British and Foreign Medical Review, 4 (1837), p. 506 N. Howard-Jones, op. cit., pp. 203-4.

13. See N. Howard-Jones, op. cit., and `The evolution of hypodermics', Chemist and Druggist, 159 (1953), p. 607.

14. Letter from Charles Hunter in Medical Times and Gazette, 2 (1858), PP. 457-8, cited in N. Howard-Jones, op. Cit., p. 222.

15. Hunter was in fact right, for the drug's essential pain-relieving action is on the central nervous system. From the injecting site, it is absorbed into the blood stream and carried to the brain. C. Hunter, 'On the ip0dermic/hypodermic treatment of diseases', Medical Times and Gazette, r8 (1859), pp. 234-5, 310-11, 387-8; C. Hunter, On the Speedy Relief of Pain and Other Nervous Affections by Means of the Hypodermic Method (London, John Churchill, 1865).

16. F. E. Anstie, Editorial, Practitioner, r (1868), pp. i-iii; for further details of Anstie, see his entry in the Medical Directory (London, J. Churchill, 1874), p. 48, and H. L'Etang, 'Anstie and alcohol', Journal of Alcoholism, 10 (197S), pp. 27-30.

17. F. E. Anstie, `The hypodermic injection of remedies', Practitioner, r (1868), PP. 32-41.

18. Examples of medical enthusiasm for the hypodermic method are in T. C. Allbutt, `The use of the subcutaneous injection of morphia in dyspepsia', Practitioner, 2 (1869), pp. 341-6; `Review of the West Riding Lunatic Asylum Medical Reports', Journal of Mental Science, i7 (18712), P. 559; J. Constable, `Case of persistent and alarming hiccough in pneumonia, cured by the subcutaneous injection of morphia', Lancet, 2 (1869), pp. 264-5.

19. T. C. Allbutt, `On the abuse of hypodermic injections of morphia', Practitioner, 5 (1870), PP. 327-31.

20. T. C. Allbutt, `Opium poisoning and other intoxications', in his System of Medicine (London, Macmillan, 1897), vol. 2, p. 886.

21. G. Oliver, `On hypodermic injection of morphia', Practitioner, 6 (1871), pp. 75-80, is one example of a dissentient from Allbutt's views.

22. F. E. Anstie, `On the effects of the prolonged use of morphia by subcutaneous injection', Practitioner, 6 (1871), pp. 148-57.

23. E. Levinstein, Morbid Craving for Morphia (Die Morphiumsucht) (London, Smith, Elder, 1878).

24. H. H. Kane, The Hypodermic Injection of Morphia. Its History, Advantages and Dangers (New York, Chas. L. Bermingham, 188o). For Kane's inquiries in the English medical journals, see `Hypodermic injection of morphia', Lancet, 2 (1879), p. 441.

25. H. Obersteiner, `Chronic morphinism', Brain, 2 (1878-8o), pp. 44965; and `Further observations on chronic morphinism', ibid., 5 (18845), PP. 323-31.

26. Both the British Medical Journal and the Lancet had much discussion and correspondence on hypodermic morphine addiction and its treatment at this time; e.g. J. St T. Clarke, `The sudden discontinuance of hypodermic injections of morphia'. Lancet, I (1879), p. 70; C. Murchison, `The causes of intermitting or paroxysmal pyrexia', ibid., I (1879), p. 654.

27. The Times, 30 January 188o; editorial comment in Lancet, z (188o), p. 100.

28. Amphlett's death was reported in the British Medical Journal, 2 (188o), P. 484.

29. Hansard 3rd ser. 304 (1886), col. 1343.

30. S. Sharkey, `The treatment of morphia habitues by suddenly discontinuing the drug', Lancet, 2 (1883), p. 1120; and his 'Morphinomania', Nineteenth Century, 22 (1887), pp. 335-42.

31. Foot's discussion was widely reported in the medical journals, for example `Royal Academy of Medicine in Ireland', Lancet, 2 (1889), p.1336.

32. There was also continuing American influence through the work of Drs Crothers and Mattison, as in T. D. Crothers, Morphinism and Narcomanias from Other Drugs. Their Etiology, Treatment and Medico-Legal Relations (Philadelphia and London, W. B. Saunders, 1902); and J. B. Mattison, The Mattison Method in Morphinism. A Modern and Humane Treatment of the Morphin Disease (New York, 1902). Mattison also spoke and wrote for the Society for the Study of Inebriety.

33. Jennings' works and papers are too numerous to be listed comprehensively here. See, for example, O. Jennings, On the Cure of the Morphia Habit (London, Bailliere, Tindall and Cox, 1890); `On the physiological cure of the morphia habit', Lancet, 2 (1901), pp. 360-68; The Morphia Habit and its Voluntary Renunciation (London, Bailliere, Tindall and Cox, 1909).

34. H. C. Drury, 'Morphinomania', Dublin Journal of Medical Science, 107 (1899), PP. 321-44; `Reckless use of hypodermic injections', Lancet, r (1882), p. 538; S. A. K. Strahan,'Treatment of morphia habitues by suddenly discontinuing the drug', Lancet, r (1884), pp. 61-2.

35. W. Osler, op. cit., p. 1005. Osler's conclusion was not universally held. Ronald Armstrong-Jones, medical superintendent at Claybury Asylum, openly disagreed with it: R. Armstrong-Jones, `Notes on some cases of Morphinomania', Journal of Mental Science, 48 (1902), pp. 478-95. There were some notable doctor addicts, for example George Harley, Professor of Practical Physiology at University College Hospital: A. Tweedie, ed., George Harley, F.R.S. (London, Scientific Press, 1899) P• 174.

36. T. D. Crothers, op. cit., p. 87. For examples of supposed female susceptibility, see W. A. F. Browne, 'Opiophagism', Journal of Psychological Medicine, n.s., r (1875), pp. 38-55, and W. S. Mayfair, `On the cure of the morphia and alcoholic habit',Journal of Mental Science, 35 (1889), pp. 179-84. J. L'Esperance, `Doctors and women in nineteenth century society: sexuality and role', in J. Woodward and D. Richards, eds., op. cit., pp. 105-27, analyses how the medical profession validated women's position in society. See also The Times, 12 January 1880; T. C. Allbutt (1897), op. cit., p. 895. Allbutt did however later revise his ideas about the female preponderance among morphine addicts; Armstrong-Jones also doubted the validity of the stereotype.

37. H. C. Drury, op. cit., p. 327.

38. The difficulties of using trade statistics to arrive at home consumption data are discussed in V. Berridge and N. Rawson, op. cit., p. 355. Comparison of published home consumption figures prior to 1860 calculated per 1,000 population, with estimated figures derived from subtracting the amount of opium exported from that imported, show that estimated home consumption after 1860, then the only statistic available, can be used only to indicate general trends.

39. Information derived from analysis of the Society of Apothecaries laboratory process book, op. cit.

40. Islington prescription book, op. cit.

41. Poisons Register, c.1886-93, Pharmaceutical Society Ms.

42. King's College Hospital case notes.

43. R. Armstrong-Jones, op. cit. (1902); and his `Drug addiction in relation to mental disorder', British Journal of Inebriety, 12 (1914), pp. 12548. Bethlem Admission Registers 1857-1893, Bethtem Royal Hospital.

44. Homes for Inebriates Association, Thirtieth Annual Report, 1913-14, P. 13, P.P. 1884-5, X V : Fifth Annual Report of the Inspector of Retreats under the Habitual Drunkards Act, 1879, p. 32. A breakdown of cases admitted shows not one had an associated narcotic habit.

45. G. B. Shaw, Collected Letters, 1874-97, ed. Dan. H. Laurence (London, Max Reinhardt, 1965), pp. 503, 581.

46. V. G. Eaton, `How the opium habit is acquired', Popular Science Monthly, 33 (1888), pp. 663-7.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|