11 The Patent Medicine Question

| Books - Opium and the People |

Drug Abuse

II

The Patent Medicine Question

The 1868 Act was testimony to the influence which professional consolidation could have on the availability of narcotics. In one important respect, however, it was incomplete. Although the inclusion of patent medicines within poisons legislation had been one aim of both medical and pharmaceutical professions since the 1850s, such products were excluded from the Pharmacy Act.1 The' Parliamentary Bills Committee of the British Medical Association had lobbied for restrictions on patent medicines to be added, but Section 16 of the Act specifically excluded any `making or dealing' in patent remedies. The question of patent medicines, in particular those based on opium, became a central concern of the continuing professional campaign regarding availability.

The first medicine Stamp Acts under which the government collected its licensing revenue had been passed in the eighteenth century. Duties on medicines were in fact first imposed in 1783; but the law as established throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and which required a licence to sell, or imposed a duty on the medicine sold, dated from three acts of 1802, 1804 and 18 12. Few patent medicines which paid duty under the Acts actually deserved the name. Only in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries had owners of medical formulae actually gone to the length of patenting them. After 1 800, medicinal compounds were only rarely patented. Those which paid the government stamp were proprietary, rather than patented medicines. Revenue was nevertheless considerable. Around £200,000 annually was reckoned to be derived from medicine stamps in the early 1890s.2

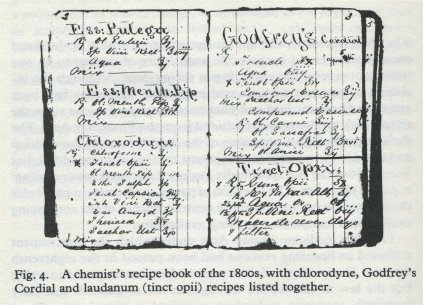

Many contained opium in some form and some had a lengthy ancestry. Dover's Powder not only became a staple of popular consumption but was used also in medical practice. Daffy's Elixir, invented by the rector of Redmile in Leicestershire, was even older. It first came to public notice between 1660 and 1680.3 As Chapter 9 has shown, the children's opiates, Godfrey's Cordial in particular, were mostly long-established.' There was no clear dividing line in the first half of the century between strictly 'medical' remedies and those used in self-medication, so patent medicines were often used in medical practice, or medical men made their own semi-patent remedies. Dover's Powder was widely used in hospital practice. Pharmacists made their own versions of Godfrey's and Atkinson's. Some patent preparations, Battley's Sedative Solution for instance, were incorporated within the Pharmacopoeia; its official name was liquor opii sedativus. Others were made by pharmacists aspiring to professional status. Peter Squire of Oxford Street produced Squire's Elixir (containing opium, camphor, cochineal, fennel-seeds, spirits of aniseed and tincture of snake-root) and later his own chlorodyne in competition with Collis Browne's.5 The dividing line between `medical' and 'nonmedical' remedies was even less clear when medical men themselves were often involved in-commercial activity.

The exclusion of patent medicines from control in 1868 was increasingly resented as establishing an area where doctors and pharmacists had little influence. The early public health legislation in the area of food and drugs continued this tendency. The 1875 Sale of Food and Drugs Act, for instance, specifically excluded proprietary or patent medicines from Section 27 of the Act, which made it an offence to sell an article falsely labelled .6 Yet patent medicines appear to have been enjoying a vogue at the end of the century. To some extent this was a natural result of the provisions of the 1868 Act, which had made ordinary opium preparations that much more difficult to obtain. There was also a practical reason. In 1875, an Act had reduced the medicine licence duty and the number of vendors increased. Over twelve thousand licences were taken out in 1874; twenty thousand in 1895.7

There began in the 1 880s a new professional campaign against open sale, this time concentrating on the issue of patent medicines. Press publicity was given to cases of chlorodyne addiction as early as 188o; the views of the developing anti-opium movement were also displayed in this direction." Discussions took place between the Home Office, the Privy Council Office and interested bodies like the Pharmaceutical Society and the Institute of Chemistry in 1881 and 1882. It was hoped at this stage to establish that patent remedies did in fact come within the Act and that further legislation was therefore unnecessary. But a test case involving a solution of chloral sold without a poison label, and brought before a Hammersmith magistrate at this period, left the situation unclear. The professional bodies, both medical and pharmaceutical, were unanimous in demanding further restrictions on the sale of patent medicines, and they had the press and the government on their side." A Patent Medicine Bill was introduced in 1884 which would have brought opiate-based patent medicines under the control of the 1868 Act, for any patent medicines containing a scheduled poison were to be sold only by a registered pharmacist. Pressure from the Society of Chemists and Druggists had ensured an added degree of freedom for the pharmaceutical profession. A pharmacist who sold a patent medicine unlawfully was not to be held responsible if he was unaware that it contained a scheduled poison.l0

The chlorodyne issue

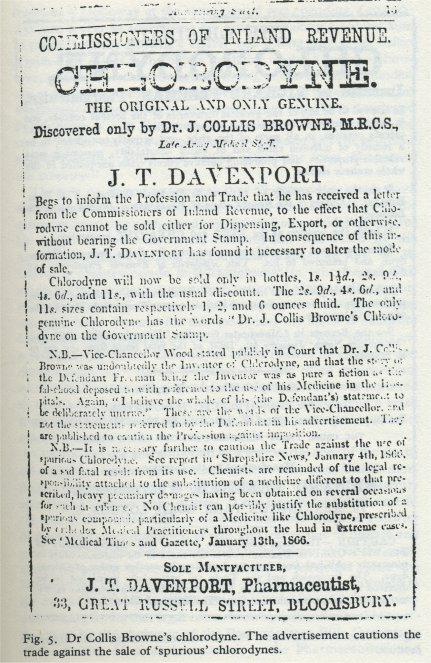

The 1884 Bill was unsuccessful, and patent medicines remained unrestricted." In the next decade, the bulk of medical and pharmaceutical hostility was directed at one particular patent preparation. This was chlorodyne, most commonly associated with the name of Dr John Collis Browne. Collis Browne, a physician, had first used the preparation in 1848, while serving with the army in India. In 1854, while on leave in England, Collis Browne was asked to go to the village of Trimdon in County Durham to fight an outbreak of cholera. His 'chlorodyne' (the name he gave the preparation the following year) produced encouraging results. But it was not until Collis Browne left the army in 1856 and went into partnership with J. T. Davenport, a chemist practising in Great Russell Street, to whom he assigned the sole right to manufacture and market the compound, that Collis Browne's became widely known on the domestic market (Figure 5).12

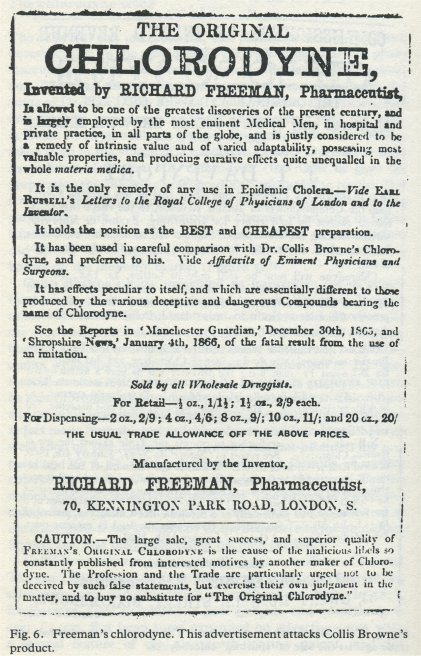

Collis Browne's early presented an impressive list of conditions which chlorodyne was claimed to cure. `Practical Instructions' were issued for the treatment of cholera and diarrhoea by the preparation; it was also recommended for `coughs, colds, influenza, diarrhoea, stomach chills, colic, flatulence, bronchitis, croup, whooping-cough, neuralgia and rheumatism' .13 Its commercial success was demonstrated by numerous attempts to find its exact formula; and to market rival chlorodynes. Chloroform and morphia were the main ingredients ; the name chlorodyne was in fact made from the words `chloroform' and 'anodyne'. 14 Rivals were soon on sale, since Collis Browne had not patented his preparation. Mr A. P. Towle communicated the formula of another chlorodyne to the Chemist and Druggist in 1859 and Towle's chlorodyne was commercially marketed. The advent of Freeman's chlorodyne (Figure 6) in the early 1860s was the occasion of an unsuccessful law suit brought by Collis Browne; and the ubiquitous Squire, too, was busy publicizing his own version.15

Collis Browne's was certainly suffering the penalties of success. The exact dimensions of its popularity are difficult to analyse. Its sales were large and advertising expenditure was high. In 1871, for instance, sales amounted to over £28,o00 and advertising to over £4,000. But large sums expended on advertisements were a normal feature of the nineteenth-century patent medicine business - Holloway at the same period was spending £40,000£50,000 a year in advertising his pills and taking a similar sum in profit-16 Collis Browne's clearly had a long way to go before it joined the giants in the patent medicine world. Sales were, however, increasing - they brought in over C3 i,00o in 1891 (a modest 10-11 per cent increase in twenty years). Many of the earlier patent medicines - the soothing syrups in particular - had been developed in the north. Collis Browne's, as a relatively late arrival on the scene, gained the bulk of its sales from London and the southern part of England. More than half its sales came from this part of the country. 17

There is no reason to suppose that all chlorodyne users were working-class, but the continuing cultural traditions of self-medication ensured that such patent medicines had considerable popular usage. In some instances, consumption was aided by the generosity of those further up the social scale. The Rev. W. R. Dawes, a country parson in Buckinghamshire, who treated with medicine `his numerous gratuitous patients', wrote to Davenport in 1858 asking for fresh supplies: `The trying weather lately having caused a large demand for this medicine, my stock is suddenly exhausted and I shall be particularly obliged by your sending me a pint and half of the Chlorodyne safely packed in a box by the Oxford coach ..."18 Sarah Williams, the wife of an engine-room artificer at Portsmouth, who after her death in 1889 was reported to have been buying at least three bottles of chlorodyne a week from her local branch of Timothy Whites, was one instance of a poor consumer who took too much.19

Chlorodyne use and addiction was the central core of the medical campaign against patent medicines at this time. Unlike morphine, however, the use of the preparation was not consistently seen from a `disease' point of view. It was largely outside the medical sphere of control. Chlorodyne use was seen more as a matter of availability and limitation of sale, and less as one of disease and treatment. E0 Medical men continued to be uneasy about the availability of patent medicines, chlorodyne in particular, after the failure of the 1884 Bill. Chlorodyne poisoning cases multiplied in the medical journals; and following the circulation of a memorandum asking for further legal controls on opium and morphine preparations by the chairman of the Parliamentary Bills Committee of the British Medical Association, "to the Pharmaceutical and Apothecaries Societies and the President of the General Medical Council in 189o, the attack on patent medicines and chlorodyne intensified.21 Ernest Hart was editor of the British Medical Journal at this time, and it was his campaigning in that role and as Chairman of the British Medical Association's Parliamentary Bills Committee which brought action. Parliamentary questioning on the subject in 1891 evoked a non-committal response .22

In the same year, it was this Parliamentary Bills Committee which communicated with the Treasury Solicitor to ask him to institute prosecutions against chlorodyne and its manufacturer. The Treasury prosecution of J. T. Davenport in 1892 was successful in extending the 1868 Act to chlorodyne in particular and opiatebased patent medicines in general. Davenport was summoned before Mr Lushington at Bow Street Police Court to answer the charge that he had sold retail a mixture (chlorodyne) containing opium and chloroform without indicating the poisonous nature of the contents on the bottle. Davenport's defence was that the preparation was a patent one and hence exempt under Section 16 of the 1868 Act. Mr Lushington, however, took a stricter view of the term: a patent medicine he defined as one actually issued with a government patent rather than a remedy paying the medicine duty. The charge was held to be proved; and Davenport fined £5 with costs.23 As a result chlorodyne and other patent medicines containing scheduled poisons had to be sold by a registered pharmacist and labelled `poison'. The new policy was vigorously prosecuted and the council of the Pharmaceutical Society took action against offending dealers-"

It is difficult to estimate how far the professional `scare' about expanding chlorodyne use was indeed justified. Chlorodyne was responsible for an increased number of deaths in the 1890s, even though actual death rates were steady. Collis Browne's sales, as its figures show, were not expanding rapidly; and the statistics of chlorodyne mortality may have to some extent mirrored public concern. For the highest mortality figures came after, not before, restriction .25 Medical men to this extent magnified the `problem' ofchlorodyne use to justify their own control. Yet the 1892 decision certainly had a marked effect on the sale of chlorodyne. Collis Browne's sales figures were down by £6,200 in 1899 (around 20 per cent) from the 1891 level ; and, at £25,000, were £3,000 lower than the total in 1871.26 The campaign against patent medicines in general did not cease. Publications such as Health News's Exposures of Quackery (1895-6) devoted whole sections to `chlorodyne, and other opiates and anodynes' and to the `widespread system of home-drugging' which had resulted from the easy availability of opiate patent medicines .Y7

In America at the same time, the revelations of Samuel Hopkins Adams in Collier's Magazine were instrumental in the passage of a Federal Pure Food and Drugs Act in 1906.28 But when the British Medical Association published its own famous investigations into the composition and profitability of patent medicines -- Secret Remedies and More Secret Remedies in 1909 and 1912 - the talk was all of remedies once containing morphine or opium, but which had now dropped it from their formulae .2' The investigations of the Privy Council Committee which considered the poisons schedule and reported in 1903 found just the same. Most of the children's soothing syrups no longer contained opium. Some cough mixtures - Kay's Linseed Compound, for instance, and Keatings' Cough Lozenges - still used it. 30 Others which had once included the drug now found commercial benefit in declaring that it was not present. Owbridge's Lung Tonic was one such; and Beecham's Cough Pills also declared that they did not contain opium.Liqufruita Medica guaranteed itself to be `free of poison, laudanum, copper solution, cocaine, morphia, opium, chloral, calomel, paregoric, narcotics or preservatives...'; it was basically a sugar solution. The frequency with which this type of claim was made on the wrapper was in itself testimony to the increasing alienation of the drug from popular, as much as from medical, usage.

References

1. For `professional' opposition to patent medicines, see `Petition from Royal College of Physicians, Edinburgh to House of Commons ...', Lancet, r (1859), P. 294.

2. `Patent and secret narcotic preparations', British Medical journal, 2 (1890), p. 639; Health News, Exposures of Quackery (London, The Savoy Press, 1895), vol. 1, pp. 24-6; L. G. Matthews, History of Pharmacy in Britain (Edinburgh and London, E. and S. Livingstone, 1962), p. 366; P.P. 1914, I X: Report from the Select Committee on Patent Medicines, p.v.

3. A. C. Wootton, op. cit., pp. 172-3.

4. `Quack medicines', The Doctor, 6 (1876), p. 37.

5. `Squire's Elixir', Lancet, r (1823-4), p. 38; Chemist and Druggist, 167 (1957), op. cit., PP. 164-5, 274, 298 and 322.

6. Quoted in P.P. 1914, op. cit., p. vi.

7. Health News, op. cit., p. 34

8. For example, the correspondence in The Times on 1o January I880, which dealt in general with the abuse of narcotics, but also brought up the question of chlorodyne. See also Privy Council Office papers, P. C. 8, 310, 1884, `Notes on the Sale of Poisons Bill'.

9. Privy Council Office papers, P.C. 8, 273, 1882, `Memorandum on the Pharmacy Act'; P.C. 8, 283, 1883, `Objections to the Pharmacy Bill'; P.C. 8, 299, 1883, `Pharmacy Bill. Sale of poisons', P.C. 8, 364, 1886, `Poisons Bill', and P.C. 8, 310, 1884, op. cit.

10. P.C. 8, 283, 3 March 1883, letter to Home Secretary from Society of Chemists and Druggists.

11. See details of the Bill and its failure in Pharmaceutical journal, 3rd ser. 14 (1883-4), PP. 746, 763; British Medical Journal, I (1882), p. 760; Home Office papers, H.O. 45, 9605, 1881-6, `Sale of poisonous patent medicines ...'; and Hansard, 3rd ser. 286 (1884), col. 8o,, where its second reading was deferred for six months in the expectation of a government Bill which never materialized.

12. J. P. Entract, 'Chlorodyne Browne: Dr John Collis Browne, 181984', London Hospital Gazette,5-73, no. 4 (1970), pp. 7-11; and J. Collis Browne, Practical Instructions for the Treatment and Cure of Cholera and Diarrhoea by Chlorodyne (London, n.d.), pp. 15-16.

13. See, for example, the advertisement in News of the World, I I May 1862.

14. `Formula for chlorodyne', The Doctor, 2 (1872), p. 173; `Composition of chlorodyne', Lancet, 1 (187o), p. 72.

15. Correspondence from Squire and Davenport on chlorodyne, Lancet, 2 (1869), PP. 74 and 152.

16. E. S. Turner, The Shocking History of Advertising (London, Michael Joseph, 1952), pp. 66-7.

17. C. D. Wilson, managing director of J. T. Davenport and C0., personal communication, 1975.

18. `Postal services and traffic', Pharmaceutical Journal, 210 (1973) P.115.

19. `Poisoning by chlorodyne', Pharmaceutical Journal, 3rd ser. 20 (18899o), p. 1035. See also H.O. 45, 10454, 1893, `Letters on the question of chlorodyne and the Habitual Drunkards Act, 1879'.

20. Norman Kerr did, however, recognize `chlorodynomania' as a disease entity, but few other English specialists followed his lead. N. Kerr, Inebriety, its Etiology, Pathology, Treatment and Juridsprudence (London, H. K. Lewis, znd edn 1889), p. 115.

21. `Memorandum by the chairman of the parliamentary bills committee of the B. M. A.', British Medical journal, 2 (1890), pp. 973-5.

22. `The consumption of chlorodyne and other narcotics', British Medical Journal, r (1891), p. 817.

23. `Important decision under the Pharmacy Act 1868', Pharmaceutical Journal, 3rd ser. 22 (1891-2), pp. 928-40.

24. H. H. Bellot, op. cit., p. 36; `The Irregular Sale of Poisons', British Medical Journal, r (1892), p. 978.

25. See V. Berridge and N. Rawson, op. cit. Also Annual Reports of the Registrar General (London, H.M.S.O., 1889-99). 26. C. D. Wilson, op. cit.

27. Health News, op. cit., p. 35; also R. Hutchinson, Patent Foods and Patent Medicines (London, Bale, Sons and Danielsson, 2nd edn 1906).

28. S. H. Holbrook, The Golden Age of Quackery (New York, Macmillan, 1959), P. 26.

29. British Medical Association, Secret Remedies, What They Cost and What They Contain (London, B.M.A., 1909), pp. 12-13, 14-18; and More Secret Remedies, What They Cost and What They Contain (London, B.M.A., 1912), p. 77, 148.

30. H.O. 45, 10059, 1888-x903, `Departmental Committee to consider Schedule A of the Pharmacy Act, 1868', p. 548; R. Hutchinson, `Patent medicines', British Medical Journal, 2 (1903), p. 1654.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|