12 The Female Addict

| Books - Narcotics Delinquency & Social Policy |

Drug Abuse

XII The Female Addict

What about girls who become addicted to drugs? We have already explained in Chapter II our reasons for concentrating on males. This was not, however, to gainsay the desirability of knowing whether similar or different factors are responsible for female involvement than for that of males. The present chapter reports on two small studies of young female addicts.

A word may be in order on the issue of the smaller proportion of female involvement. About all that we can say with any degree of assurance is that the issue is probably not a simple one. It is known that the much higher incidence of the use of opiates among males is paralleled by similarly marked disproportions in the incidence of alcoholism, juvenile delinquency, and crime. These differences cannot be easily explained by the greater psychological stability of the female constitution or the more effective sheltering of the female from psychological stress. Women, for instance, take up as many mental hospital beds as do males, and the relative number of females in outpatient and private psychiatric or psychotherapeutic treatment is, if anything, even higher.

That females, as such, do not have a lesser diathesis toward drugs is indicated by the fact that, prior to the Harrison Act, the incidence of narcotics use by females equaled and probably exceeded that among males.1 The simple hypothesis sometimes appealed to in explaining the sex differential in delinquency and crime—namely, that females are more apt to be protected from the social consequences of their actions—seems clearly inappropriate in relation to drug use. The incontinent use of drugs is not easily concealed. Moreover, one effect of such protection would be to increase the proportion of females in hospitals and decrease the proportion in jails and reformatories. If anything, this differential runs the other way. As reported in Chapter II, slightly more than one in five known cases of drug use were female, both in the below-sixteen and in the sixteen-through-twenty age ranges. This may be compared to an average of one in eight in new admissions to Riverside Hospital.

Perhaps the major plausible, relatively simple hypothesis remaining is that females are less likely than males to express their tensions in ways that are detectably and flagrantly violative of prevailing social codes. It may be noted that such a sex differential would have been operative with respect to the use of narcotics to a much lesser degree, if at all, prior to the Harrison Act than subsequent to its passage. Not only was the medically nonprescriptive use of narcotics not illegal, but females could readily obtain narcotics in the context of an acceptable social alibi: narcotics were major ingredients of proprietary medications for the then eminently respectable and vaguely designated array of disturbances that masqueraded under the title of "female complaints." One contemporary effect of greater female conventionality would be, of course, to inhibit girls in experimentation with drugs and thus contribute to the lower incidence of their involvement. Another less direct effect contributing to the same end would be that their lesser involvement in delinquency would also decrease the likelihood of their coming into contact with the drug-using subculture. This would, of course, also obtain with any sex differential in the incidence of delinquency, regardless of how the delinquency came about.

Another possibly relevant consideration in the explanation of the lower incidence of narcotics involvement among girls is that females have available to them another technique of "acting out" which may subserve many of the same needs served by narcotics (albeit in a dramatically different fashion) and which is not available to males, namely, the out-of-wedlock pregnancy. To be sure, there must be some male involved in every pregnancy, but the drama is enacted largely in the life of the female. It is not clear, however, if this is a relevant factor, why the sex ratio of drug involvement should be the same (or somewhat lower) for cases under sixteen as for cases in the sixteenthrough-twenty age range.

The general questions we have attempted to answer about female adolescent opiate addicts in this study are the following: (1) What is the nature of the addiction process for female adolescent addicts? (2)

What are their personal characteristics, relationships, and psychopathology? (3) What is their social background—the structural and dynamic characteristics of their families? (4) What role does addiction play in their lives?

Where it was feasible and relevant, we have contrasted the characteristics of the female patients with the male patients (based on our own comparable studies) in order to cast light on the final question, namely: (5) Whether and how the process, characteristics, background, and function of opiate addiction of female adolescents differ from those of male adolescent addicts.

The Sample

Twenty female patients were selected for clinical study. These were serial first admissions who came to Riverside Hospital through the Screening Clinic operated by the hospital in conjunction with the Narcotics Term Court of the New York City Magistrates' Court system. Of these twenty patients, eleven were Negro, three were of Puerto Rican or other Spanish-speaking Caribbean origins, five were of white ethnic groups, and one patient had a Puerto Rican mother and an American Negro father. At the time of admission they ranged in age from seventeen through twenty years, with a median age of eighteen and one-half. Except for two cases missed during the vacation of the psychiatrist who interviewed these patients, these were all the female patients admitted between September, 1955, and November, 1956.

In the thirteen months required to obtain this sample of twenty patients, there were twenty-two first-admission female patients and 225 male patients, a ratio of one to ten. Serial first admissions were selected rather than a block of patients resident in the hospital during a shorter period, partly in order to study patients who were not overinterviewed (and interview-wise), but mainly in order to study patients comparable in their hospitalization experience and treatment. Furthermore, by studying patients serially, there were never more than a few patients in clinical investigation at a time, a factor which would maximize the patient's individuality in the eyes of the investigator. All these patients were under the care of the same psychiatric team in the hospital. The data to be reported take into account relevant observations by the psychiatric social worker, psychologist, nurse, occupational therapist, and school personnel who constituted the team; but, in the main, they were assembled by one of the writers (who was the psychiatrist in charge of the hospital team) in the course of from two to twenty interviews (with a median of six interviews) with each of the patients.

In order to study the family background of the female adolescent addict, we took for our sample the families of twenty-two female patients who were resident in Riverside Hospital between November, 1955, and March, 1956, who had a parent or parents who could be interviewed at home by specially trained second-year social work students. All these families had had some (usually little) contact with psychiatric social workers in the hospital. None had been previously visited in their homes. Although we would have preferred to have made home visits to all the families of the patients we studied clinically, our social work investigators had to do all their interviewing between the limiting dates, since some of the data they obtained were to be used by them in a group master's thesis project at the New York University School of Social Work.2 However, ten of the patients in the family study were also in the clinical study.

The Clinical Study

Beginning with the response to her hospitalization and to the interview, a picture of the life history, relationships, and psychopathology was constructed for each of the patients. Though we did not use any formal questionnaire, we planned to elucidate the following matters through the interviews: (1) experience with opiate and nonopiate drugs and with drug-users; (2) personal adjustment, including school and work experiences, pattern of interpersonal relationships, goals, expectations, and interests; (3) family structure, background, goals, achievements, and status characteristics; (4) interview behavior, e.g., general behavior, appearance, rapport, productivity, affect, style, intellectual functioning, and memory; (5) emotional response of the interviewer to the subject, and vice versa; and (6) medical psychiatric history, emphasizing symptoms related to psychiatric disorders.

The Family Study

Six second-year social work students participated in group training sessions in which the questionnaire which we had developed for our earlier study of male adolescent addicts was discussed, modified, and elaborated on by the group to meet the needs of describing the familial experiences of female adolescent addicts. In the course of these sessions, as in the corresponding training sessions of the earlier study, the special research needs of thoroughness and objectivity were discussed in a variety of contexts, and the all-too-common social worker's fear and misconception of research instruments and questionnaires were worked through.

Each of the families was interviewed at home, two to four times. A process recording of the interview was written immediately after each interview; a case summary (which followed a topical outline) was also written, and a check-list questionnaire was filled out after the interviewing was completed. The process recording, the topically organized case report, and the questionnaire were reviewed and edited for internal consistency and completeness in a final discussion of each family.

Findings of the Clinical Study

THE ADDICTION SYNDROME

Seventeen of the twenty patients were addicted to heroin, in some instances supplemented by morphine or methadone, prior to this hospitalization and displayed unquestionable symptoms of a withdrawal syndrome on hospitalization. One patient had a history of addiction, but came to the hospital without current dependency. Two had no history of addiction, but were using drugs regularly and increasingly—up to five times weekly—in the month prior to hospitalization. Nine of the patients had had previous medical treatment for addiction or had found themselves in the clutches of the law. Eleven had not experienced any external interruption in their use of drugs until the present situation led to hospitalization.

Eleven of the patients came to the hospital following an arrest for possession of heroin and/or other charges, e.g., prostitution or theft. Three were brought to the hospital by their families. Six initiated the hospitalization themselves. Of these six, two came to the hospital because of a change in their external circumstances which interfered with their ability to get heroin; they had depended on a male addict-pusher to support their habit, and, when he was arrested, they found that they could not manage. Another sought hospitalization because she could not "get high" any more; she needed and wanted a "free period." A fourth came to the hospital because her increasing habit could not be supported through her legitimate earnings as a dietitian's assistant in a hospital; though she wanted to turn to prostitution, she could not make herself do so. A fifth came for reasons known only to herself, although it seems likely that she sought hospitalization because of some practical difficulties associated with addiction rather than dissatisfaction with heroin use per se. The sixth came to the hospital because she felt that heroin use was hurting her and her baby.

Thus, the major factor leading to hospitalization was clearly in the situation and not in the patient. In a minority of cases, the mounting difficulties of supporting a habit in our society may lead to voluntary hospitalization, but only after other courses are attempted. The rarest of reasons for hospitalization of the female adolescent addict is that she regards her heroin addiction as harmful.

These data are consistent with a general impression that the typical young female addict who is hospitalized in connection with her drug-use problem has already experienced prolonged and regular use of heroin or other opiates. The hope that either male or female adolescents who become hospitalized in connection with drug use are involved only superficially or transiently with opiate drugs is not often supported by our observations.

First use of opiate drugs among the twenty female patients took place at a median age of sixteen; the range was from fourteen to nineteen years. For the majority, heroin was their first source of intoxication. Only nine had previously used any other intoxicant drug. Two regarded themselves as alcoholics before they began to use heroin; another three had used alcoholic beverages for intoxication, but did not like to do so, because they felt that they "lost control" when intoxicated. Only seven of the twenty patients had ever tried marijuana. Two gave it up because they did not experience any satisfaction from this drug; two gave it up because they regarded the giggling and silliness of the marijuana intoxication as alien to their ideal of being able to stay "cool" and "adult"; two gave it up because they became anxious when they began to feel that people were staring at or talking about them during the state of marijuana intoxication; one gave it up for both of the two last-named reasons; and one gave it up because she was frightened by disturbances in spatial perception.

What is the function of opiates in their lives? This question must be answered at several levels, as we pointed out in Chapter IX. The generalizations we offer there for male adolescent opiate addicts are equally applicable to the female adolescent addict—they take opiates because of certain highly estimated, consciously experienced effects of the drug; as a defensive reorganization of their lives; for deep, unconscious "symbolic" needs; and for the complex psychophysiological processes of tolerance and dependence. In the simplest of terms, they feel better when they use drugs than when they abstain.

We were interested in the setting of the onset of drug use. Since addiction is preponderantly a problem of young men, we were inclined to expect that the setting of initial use would typically be that of some man introducing heroin to an adolescent girl. Our data indicate, to the contrary, that only a minority (six cases) received their first heroin from a male user. The most typical setting (thirteen cases) of initial use was with one or more other female users. One took her first dose while she was alone. Slightly more than half received their first heroin from a person in their own age range (eleven cases) ; the rest (nine cases), from an older person. None purchased their first heroin. It was, in the main, given to them, ostensibly with some reluctance, by a donor who was already an experienced user, though not necessarily an addict; two, however, stole their first heroin, one from her addict-pusher brother, the other fiom an addict-pusher girl friend.

As the frequency of their use of heroin increased, there was a shift from predominant use with other female users to predominant use with male users or with a mixed group in which male users were much in the majority. In short, the companions of onset were not the companions of regular use, though the companions of onset were usually persons who "made some difference" in their lives.

The life situation at the time of onset is difficult to clarify. The ostensible motivation for first use was "curiosity." All the patients knew that heroin is illicit, habit-forming, and possibly lethal (through an overdose), and they believed that heroin use is debilitating. However, they were also aware of its reputation as "a good way to get high," that is, they expected relaxing and comforting effects. Their first use clearly did not express ignorance, but rather disregard for what they knew about the long-range probabilities of harm and trouble in the quest for immediate pleasure. Only occasional patients were consciously motivated by forces other than curiosity. Two were aware of nervousness, anxiety, or unhappiness. They felt that heroin would make them feel better, and it did. Though three others were chronically depressed, their conscious motivation for heroin use was "curiosity," rather than relief. None of the patients first used heroin in response to a severe and distressing situation except when such a situation—death of a baby (in one case), loss of a boy friend (in two cases), or bitter quarrel with a father (in one case)—occurred in the setting of prolonged and pervasive maladjustment.

Thirteen of the patients recalled quite clearly how they responded to their first use of heroin. Ten got what they wanted—e.g., being high and liking it—on their first use. Three did not enjoy their first experience, but returned for more in the hope that they would learn to like it, and, of course, they all did. Seven patients were too vague or evasive in the reconstruction of their early heroin use for us to judge how they responded to their first experience.

In the course of their continued use, they had to spend increasing amounts of money to maintain themselves without withdrawal distress and with continuing satisfaction. They usually supported their habit in the course of their addiction by several means (in order of descending frequency) : by living with an addict-pusher (nine cases); by abusing the confidence of friends or relatives (eight cases); by working (seven cases); by prostitution (six cases); through a relative who was an addict-pusher (two cases); through theft (two cases); and, in one case, by gifts of drugs from friends who were users.

PERSONAL CHARACTERISTICS, RELATIONSHIPS, AND PSYCHOPATHOLOGY

Slightly fewer than half the patients (eight cases) approached the interview in a compliant and cooperative attitude. They were quite willing to talk about themselves and their life situations. Though they were skeptical and negativistic about the likelihood that anything could be done to help them in their difficult situations, they were grateful for the asylum and support of the hospital. They hoped to reorganize themselves in the course of the hospitalization in order to cope better with their lives than they had in the course of their drug use.

About half the patients (nine cases) approached the interviewers in an angry, demanding, and complaining attitude. Though they answered questions about themselves, they did so in a flippant and resentful manner. They insisted that they had been deceived in their expectations of the hospital and by the statements made to them about how they would be treated. They regarded hospitalization beyond detoxification as an unwarranted and unnecessary intrusion into their lives, which they considered quite under control and manageable, despite quite extensive evidence to the contrary.

The remaining patients showed gross disturbances of communication. It was quite difficult to obtain information about them and their life situations. Two were quite willing to remain in the hospital. The third shared the indignant attitude of the second of the above groups.

Though the patients in the first group were compliant and cooperative, they could not be regarded as well-motivated psychiatric patients. No clinician would mistake their superficial compliance and cooperativeness for a genuine wish to explore their current and past relationships and feelings. None, despite their cooperative attitudes, could be regarded as having insight into the fact that their lives prior to drug use were troubled nor into the fact that they had some role in creating these difficulties. In brief, none of the patients had the inclination or the modicum of insight necessary for voluntary involvement in psychotherapy. We do not mean to imply that these patients were unable to participate in psychotherapy, but rather that their lack of insight and their conscious attitudes with regard to need for treatment made the initiation of treatment difficult and slow. It is possible, with patience and persistence, in a controlled environment, where conscious attitudes and fears about treatment can be worked through, to get these patients into therapeutically more promising relationships and communication.

The utilization of hospital facilities by the female adolescent addict, as by the male adolescent addict, is typically characterized by meager participation in or utilization of hospital resources, whether educational, recreational, or psychotherapeutic. They do participate in sadistic hazing of new patients, in sexual affairs, and in inciting fights over them by the male patients. They do not take work assignments seriously. They have a high incidence of physical complaints without demonstrable physical pathology. Unlike the males, who generally try not to attract attention from the hospital staff, the female gets herself noticed. Perhaps this reflects a characteristic difference between men and women in our culture. Whatever the basis of the difference, female adolescent addicts are unquestionably far more demanding of the time and energy of the staff than are male patients.

From our interviews, we learned that the relationships and social adjustment of our patients prior to their drug use were conspicuously troubled and stormy. Of the nineteen patients who had had any school experience in this country, only three had a scholastic career devoid of extensive truancy, learning difficulties, or notable misbehavior with teachers and with fellow students. Two of these three left school because of out-of-wedlock pregnancy. What their school career would have been without this interruption (by the fourth term of high school) is a moot question. The third was graduated from high school without incident, but managed to insulate herself from the educational process. In a less enlightened period, she would have been dismissed from school as a poor student. Since she attended fairly regularly, stayed out of fights, and behaved politely, she was awarded her high school diploma.

Of the twenty patients, six could be regarded as having made some positive vocational adjustment. Two of these were employed by their families in undemanding and protective circumstances. One was a barmaid in her father's saloon; the other did domestic work in her grandmother's boarding house. Four of the twenty patients unquestionably made a good vocational adjustment, prior to and continuing into their heroin addiction, working steadily with a sense of purpose and satisfaction. The remaining fourteen were either never employed or worked for short periods at many jobs with long intervals of unemployment.

Only six of the twenty patients had no conspicuous behavior difficulties at home. Of these, two were remarkably overindulged children whose whims were law. Neither was able to get along in school; one made a good vocational adjustment in a situation in which she was the petted and praised youngest worker, a situation quite analogous to her family situation in which she was the petted and praised baby sister of five brothers. The other four who manifestly caused no distress at home did so by adopting a passive-submissive attitude to mothers who were hostile, demanding, and critical. The remaining fourteen were recurrently in trouble with their parents, with whom they were disobedient, demanding, and disagreeable.

Eleven of the twenty patients acquired an out-of-wedlock child or pregnancy preceding their addictive drug use. Another two avoided this outcome by chance; they were sexually promiscuous and neither took nor demanded any contraceptive measures.

Eight of the patients had been seriously maladjusted in the areas of family life, school, and work; eight were notably disturbed in two of the three areas; three patients in one of the three; and only one (discounting an out-of-wedlock pregnancy and a consequent disastrously unsatisfactory marriage) could be described as showing no abnormal disturbance in any of the three areas. Even the last and most favorable of these patients could hardly have been expected to make a satisfactory life adjustment if she had not become involved with narcotics; her comparatively "good" adjustment was achieved through an evasive, guarded, and controlled participation in school, work, and family rather than as an expression of adequate, intact ego functions.

From our interviews, the patients' histories, and the psychological testing, it seemed clear to us that the female addicts, like their male counterparts, were seriously maladjusted adolescents prior to addiction. Like any other set of psychiatric patients, the female addicts could be described in the terms of any standard psychiatric nomenclature. However, we believe that it would be more useful to classify and describe them sui generis, in terms of the personal living situations and relationships, as well as in terms of their formal psychopathological manifestations. Although we have reworked our phenomenological typology several times since we first struggled with the general description and diagnosis of adolescent addicts, the formulation we offer here for the female adolescent addict remains a slight variant of the schema in our report on male adolescent addicts. This schema is not intended as an exhaustive typology. It is intended as a compromise between the bare diagdostic terms of the current nomenclature and the at-least-severalhundred-word summary of the ego functions, symptoms, defenses, and relationships which we would need to properly and uniquely describe each of the patients.

Overt Schizophrenia. These patients were not hallucinating or psychotically disturbed. However, they displayed inappropriate affect, labile emotionality, serious thinking disorders, and delusions of reference and grandeur. Rather than being quietly withdrawn, they were too much in everyone's attention through making trouble, but in their relations with the staff and with other patients they were empty of feeling and relatedness. Three patients of our sample were in this category. All three had been regarded as queer, bizarre, and unreachable since childhood. One had been hospitalized prior to drug use and diagnosed as schizophrenic, hebephrenic type.

Borderline Schizophrenia. These patients were struggling against a disorganizing and disruptive process in which they experienced extreme anxiety related to feelings of inadequacy and low self-esteem. Paranoid trends and early thinking disturbances were noted. Though moralistic and struggling toward conventional goals in work, family living, marriage, and education, they found themselves unable to carry out the required roles and relationships. Suppression of resentment and hostility toward their mothers was one of the most pressingly and poignantly conscious issues in their lives; they regarded their mothers as depriving, critical, and dominating, yet they clung to them as potential sources of love and support. In short, their relationships with their mothers were intensely ambivalent. These observations are incorporated in the diagnostic description not because they were subtle or inferentially "dynamic factors," but because they were acute concerns with which they were struggling. They were depressive, anxious, or guilt-ridden. Five of the twenty patients could be placed in this category.

Inadequate Personalities. These patients showed a paucity of interests and goals and an impoverishment of thinking and emotional expression. They were neither "good" delinquents nor "good" schizophrenics. They were successful in establishing role systems in which people responded to them almost as though they were just "not there." Although other cases of this type are encountered, which justifies noting it, only one in our sample could be so classified.

Complex Character Disorders. These patients can be described in general as follows: they regard their difficulties and symptoms as ego-syntonic. Their neuroses, to use the collective term, are alloplastic rather than autoplastic. They perceive their difficulties as imposed on thim by fate, chance, or by an unfavorable environment. There are three major types within this category, types which differ by the degree to which particular relationships and recurrent experiences occurred in them. The types are not exclusive; the salient features which define them can often be perceived more subtly or less extremely in the others.

The Sadomasochistic Type. The key themes in the lives of five of the patients was a struggle between efforts to control aggression, on the one hand, and sadomasochistic involvement, on the other. Every so often they would be overcome by anger and resentment, only to suffer consequent anxiety and pangs of self-reproach, which, in turn, were alleviated by brief periods of penitence. From childhood into the period of their sexual affairs, they were continually involved in relationships in which they were beaten, mistreated, and picked on. They were accident-prone and seemed to invite teasing and provocation. The pattern of teasing and abuse was already evident in their early childhood relationships with one or both parents.

The Angry, Aggressive Type. Four of the patients were openly aggressive, stubborn, negativistic, and quarrelsome. They were going to take nothing from anyone, ostensibly in affirmation of their independence. This independent attitude, carried out to the point of a caricature, was a defensive denial of their wish for passivity and dependence. Their anger and hatred was the rule, placidity or satisfaction, the exception. Unlike the sadomasochistic type, they experienced no anxiety or self-reproach for their anger or their troublesome behavior. They could project, rationalize, and justify their rage; their worlds were out of joint, not they.

The "Cool" Psychopath. Two of the patients were cool, glib, smooth, clever, manipulative, apparently free of anxiety, and facile at rationalization. They looked at the experience of hospitalization with calm superiority and on the other patients as crude roughnecks. They had no need or wish to modify their behavior on the basis of their experience, since they regarded their experiences, however deplorable they might seem to the rest of the world, as wonderful, interesting, and remarkable.

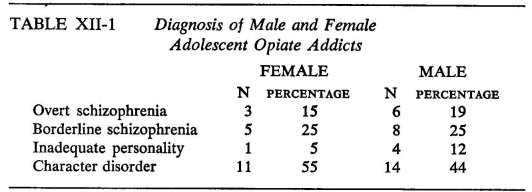

It may be appropriate to note (see Table XII-1) the similarity in the distribution of diagnoses for the female addicts of this sample and the sample of male addicts reported previously.

The only notable difference in frequency (which, however, is not statistically significant) is in the category of character disorder. However, the differences in the qualitative aspects in this area are quite striking. Thus, the subtypes we used to describe the male adolescent addict in the general category of the character disorder were "pseudopsychopathic delinquent" and "oral character." Both these subtypes defined their lives in terms of aggression and hostility experienced as pleasurable or as justified reaction to mistreatment or frustration. For the female adolescent addict, these themes were absent. The angry, aggressive type did not wear the façade of "joy in battle" of the pseudopsychopathic delinquent, even though some of their outward behavior was quite similar. The oral male addicts whose rage and anxiety in response to frustration was episodic—as was the anger and resentment of the sadomasochistic type of female addict—did not experience anxiety and self-reproach following their episodes. In short, the Gestalten of the character disorders of the male and female adolescent addict were quite different.

Findings of the Family Study

The families of the female addicts, like those of the male addicts, seemed heterogeneous, both in structure and in the relationships between the teen-aged daughters (who became opiate addicts) and the important figures in their lives. Like the male addicts, their families were of the types which clinical experience suggests are productive of serious difficulties in living. Their parents were rarely as responsible for their children's—or their own—welfare; or as warm, objective, and encouraging of their personal development; or as steady and reasonable in disciplinary practices; or as free from psychopathology as we would like any families to be. In staff diagnostic conferences, the impression we garnered from the presentations of family backgrounds, as seen by the hospital psychiatric social workers, was, at best, that there were some positive features in some families, but that these were far outweighed by grossly pathogenic features and, at worst, that there was a congeries of pathogenic features without any apparent countering salutary influences.

Turning from general clinical experiences and impressions of the family background of the female addict, we can construct a picture of her typical family background out of the explicit categories of our own investigation. For simplicity in reporting, we shall describe those aspects of familial relationships or experiences which we regard as pathogenic and which occurred in 50 per cent or more of the cases as "usual" and those which occurred in 70 per cent as "typical"; an unqualified generalization is to be taken as "typical."

The relationships between the parents of the female adolescent addicts were typically discordant. Their fathers were usually absent from the parental home for prolonged periods in our subjects' childhoods; typically, at least one parent figure was absent from the home for a prolonged period in early or later childhood. In early childhood, their mothers were usually the dominant figures (i.e., clearly dominant - father minimally involved in handling money, administering authority, making decisions); in later childhood, this was typically the case. Similarly, the mothers were typically the important parental figures (the one the patient went to for advice, affection, or disciplinary statements). They were the ones who made and enforced disciplinary policy, which typically took the form of physical punishment, threat of reformatory or police, cruel and sadistic ridicule, locking up the child, taking away various privileges, humiliation, withdrawal of food, or threat of these, rather than offering or withdrawing love.

Our subjects typically did not receive warm, affectionate treatment from their parents. The relationships between our subjects and their parents fell at the extreme of our scales. They were usually denied gratifications or spoiled (overindulged) or overindulged at some times and harshly frustrated at others. Parental expectations for their behavior and for their future were typically vague or rigid. Their ties with their mothers or fathers were typically either weak or intense. The mothers were usually insecure women, concealing their conflicts and insecurities behind a façade of efficiency, responsibility, and excessive mothering; they were usually religious and prone to preaching; they were opinionated, judgmental, rigid, authoritarian, and dictatorial; and they were punitive or indifferent in regard to their daughters' sexual functions and development. The fathers were usually "immoral figures," practicing infidelity, pimping, homosexuality, crime, alcoholism, or drug use. In almost half the instances, they could be described as weak, immature, quiet, and passive in their family roles. They were usually impulsive, concerned with immediate gratification, improvident, and unrestrained in their discharge of hostility. Both the mothers and fathers were usually distrustful or manipulative of authority figures. Neither the mothers nor the fathers made use of community resources for recreation or for cultural enhancement.

In summary, the clinical impression that the female adolescent addict has developed her difficulties in relationships and her psychopathology through immersion in a malignant familial environment is amply documented by the family study data.

In viewing the data on the family backgrounds of the female addicts, there are two points to be considered. First, though the unmentioned categories of family characteristics were not frequent, they might well have occurred with greater frequency in the family backgrounds of female addicts than in those of other adolescent girls in the same cornmunities. Since we did not have a control group of nonaddicted, non-delinquent girls, we cannot answer this question. For example, six (more than one-fourth) of our patients had at some time lived in foster homes or institutions. Though this can hardly be said to be characteristic of female addicts, it may have nonetheless occurred more frequently in the lives of this group than in those of such appropriate controls.

Second, we were concerned with the difference in background of male and female adolescent addicts. As pointed out previously (chapters VIII and X), the male adolescent addict can be described in terms of three general aspects of personality structure and two patterns of attitudes and values. These are: weak ego function, defective superego function, inadequate masculine identification, lack of middle-class orientation, and distrust of major social institutions. Working definitions were written for each of these five personal characteristics. A list of family background factors which psychiatric and psychoanalytic literature and relevant research suggest are plausibly related or conducive to the development of such personal characteristics was drawn up. Our working assumption was that, the more frequently such factors occurred, the greater would be the likelihood of these characteristics in the individual; none of the factors in themselves need lead to these personal characteristics, but an accumulation of such factors would. An index score for each male addict and control subject was obtained for each of the five characteristics by taking the ratio of the number of factors categorically described (experiences or situations) which occurred in any individual to the total number of factors listed. Our hypothesis was that the index scores would be higher in the family background of the male adolescent addict than in the background of the male control subject. The data indicated that the male addict developed in a milieu which afforded far more of these factors for each of the five personal characteristics.3

Excluding as irrelevant the index of factors leading to inadequate masculine identification, we compared the families of male and female adolescent addicts.4 There were no significant differences in factors leading to weak ego function or defective superego function. However, the family backgrounds of the female addicts had fewer of those factors leading to lack of realistic middle-class orientation (Index IV) and distrust of major social institutions (Index V) .a These index differences between male and female addicts were based on a few items which were much more common among the male than among the female patients. These were not items which significantly differentiated the male addicts from the male controls, and it may be that we are dealing here with a general sex difference in the subcultures from which our cases came. Moreover, it is quite possible that unrealistic aspirations on the parts of the parents and distrust of social institutions are not so forcefully communicated to the female child as to the male or that, if they are, they do not have the same impact on their psychosocial development. Thus, if a girl accepts marriage as the major goal of personal fulfillment, the consequences of frustration ensuing from unrealistic parental aspirations may be less pervasive of the significant areas of her life than they would be of her brother's. By the same token, it is likely that we did not look for realism of expectations in the relevant life areas (and, for that matter, it would be much more difficult to do so), i.e., in those areas of specifically feminine roles. Similarly, attitudes of cynicism and distrugt toward the larger society may have much less consequence for a girl than for a boy if she remains closer to the intimate environment. Such considerations would lead one to expect that the variables represented by indexes IV and V do not play much of a role in the genesis of female addiction and hence that the families of female addicts are not, on the average, markedly deviant in these respects.

There were only three items which, individually, significantly differentiated the families of the male and female addicts. It was more often the case with the male addicts than with the female that their mothers had unrealistically high or unrealistically low aspirations for them in their early childhood; that their mothers had unrealistically high or unrealistically low aspirations for them in later childhood; and that their fathers had unrealistically high or unrealistically low aspirations for them in their early childhood.

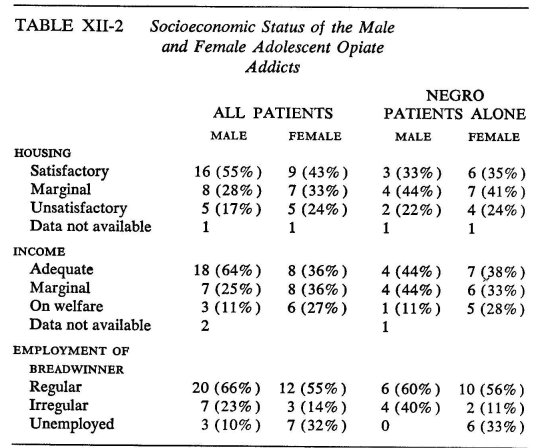

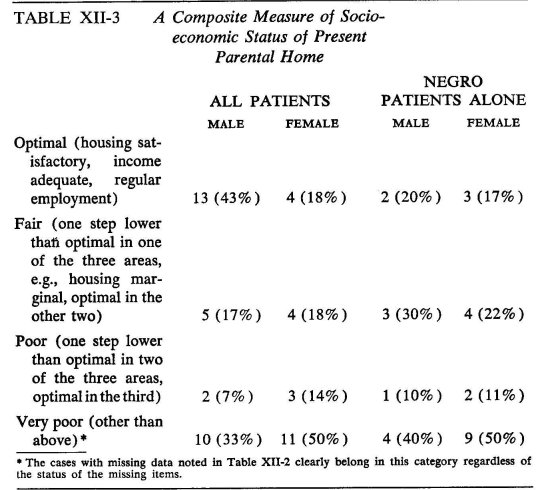

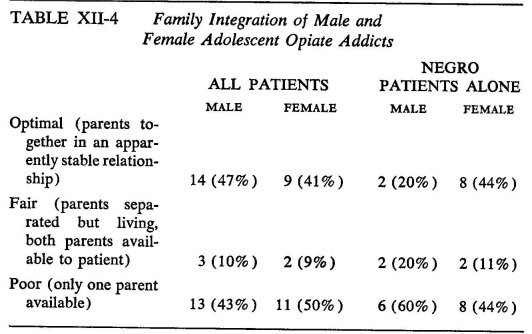

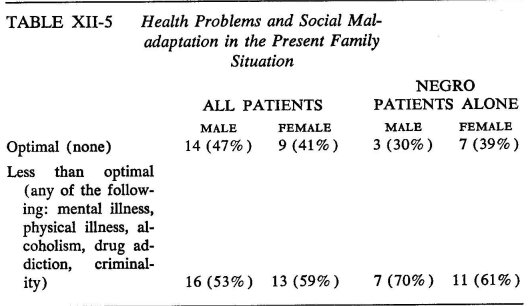

Comparative data on the family situations of male and female addicts are given in tables XII-2, XII-3, XII-4, and XII-5. Although we give the parallel figures for the total male and female samples in these tables in addition to those for the Negro subsamples, it should be apparent that, because our female sample is composed mainly of Negroes, the only dependable comparisons are those between the Negro subsamples.

With respect to socioeconomic conditions, the family situations of male and female Negro addicts are essentially similar. It may be recalled from Chapter V that the Negro male addicts are the most deprived among the male addicts; the female Negro addicts match them in degree of deprivation. This is evident when we consider the conditions of housing, family income, and regularity of employment of the family breadwinner. On the composite measure of socioeconomic status, however, the females seem to be at a greater disadvantage.

The family integration of the male and female addicts does not differ. However, when we look at the family integration controlling for ethnic background, we note that Negro female addicts tended to come from better integrated families than did the male addicts, a finding consistent with that reported above with regard to our fourth index in the extendedfamily—background study, i.e., female addicts came from families with more realistic middle-class orientation than did male addicts.

Family deviance with respect to health problems and social mal-adaptation was no more frequent among the female than the male samples, for the total sample or for any ethnic group, except that the parents of the Negro female addicts more frequently had alcoholism problems (50 per cent) than did the parents of Negro male addicts (30 per cent) —a difference which, however, in view of the small sample sizes, is not statistically significant and which is offset by small differences favoring the males in other categories of deviance.

Finally, it may be of interest to note the neighborhood distribution of the female addict. The patients and the families we studied lived in those areas of the city where opiate use was most prevalent. In fact, this generalization is accurate for all female patients ever admitted to Riverside Hospital. Like the male adolescent opiate addicts, they came from those areas of the city which are least suitable for living—areas of inadequate housing, of the highest population density, of maximum unemployment, and of familial disorganization. Though they resided in these settings, their families were no worse off on the whole than other families in the same communities. The heterogeneity in the social characteristics of their families again suggests that personally experienced poverty or low status were neither necessary nor outstanding factors in their addiction, though the prevalence of poverty and low-status families in the community could not but unfavorably affect their development and relationships. We remind the reader that, though the "ecological" pattern of adolescent opiate addiction is not related in a simple way to the vulnerability of any individual to becoming an addict, it is unquestionably related to the prevalence of the problem.

In summary, we have found that female adolescent opiate addicts had serious difficulties in their lives prior to becoming addicts or beginning to use drugs—difficulties expressed in disturbed relationships and behavior in school, at work, and with their families. They began to use drugs in the context of serious maladjustment, into which they had limited insight. They were most often introduced to heroin by their female peers, who were ostensibly reluctant to involve them in opiate use; they were not introduced to heroin by older men seeking to "enslave" them. The prevalent conscious motive for their initial use was "curiosity." They were not naïve as to the personal or legal consequences of opiate addiction in our society. They supported their habits through a variety of means, of which the most common were living with a male addict-pusher and taking advantage of the confidence of friends or relatives.

Hospitalization was initiated through external forces, usually through being arrested. Once in the hospital, they usually began to demand their release or accepted a stay in the hospital in a passive-dependent attitude. They had no insight as to their need for psychotherapy and only minimally accepted their need for further education, vocational training, or placement. Their behavior in the hospital as a group was conspicuously; rather than quietly, nonconforming.

They lived in neighborhoods that we found to be high-drug-use areas for teen-aged boys. Their families resembled the families of the male adolescent addicts, in terms both of their life-long family situations and their current familial environments, the notable exceptions being that indexes of unrealistic aspirations for the children and distrust of major social institutions were found to be lower for the families of the girl than of the boy addicts. There is thus reason to believe that the female adolescent opiate addict developed her difficulties in social adaptation and her psychopathology through immersion—or at least while immersed—in a malignant familial environment.

STATISTICAL FOOTNOTE

a These differences are significant at the .05 level. We must point out that such small samples as we worked with here can verify only the grossest differences. There may be more points of difference than these data indicate.

1 Cf. Alan S. Meyer, Social and Psychological Factors in Opiate Addiction: A Review of Findings together with an Annotated Bibliography (New York: Bureau of Applied Social Research, Columbia University, 1952), p. 38.

2 At that time, part of the NYU Graduate School of Public Administration and Social Service.

3 This paragraph in effect summarizes Chapter X; the reader is referred to that chapter if he wishes to refresh himself on the details of methodology, analysis of data, and interpretation of results.

4 Since the female sample was preponderantly Negro, our comparison of the family background of male and female addicts is restricted, of necessity, to a comparison of the family backgrounds of ten male and eighteen female Negro adolescent addicts.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|