11 Family Backgrounds of Selected Addict and Control Cases

| Books - Narcotics Delinquency & Social Policy |

Drug Abuse

XI Family Backgrounds of Selected Addict and Control Cases

The following case summaries offer a somewhat closer view of the contrasting family environments of addicts and controls than can be given by numerical indexes.1

The addict cases to be presented here are not the "worst" that could have been selected from the thirty available. In fact, on the basis of the indexes alone, the family background of one of these boys (James McGill) was one of the most atypical of the addict group. These histories were chosen primarily because the psychiatrist member of our team had first-hand knowledge of the boys and their families; he could, therefore, supplement and more accurately interpret the information obtained by the interviewers. The three control cases are two arbitrarily selected ones markedly typical of their group in terms of their scores on each of the indexes, whereas the third (actually the first, in order of presentation) is one of the least typical in this respect.2

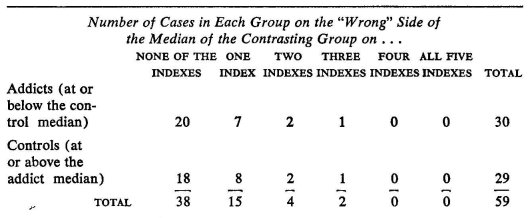

Thus, even with so lenient a criterion of "marked" deviance (lenient, that is, in terms of a predetermined criterion in selecting deviant cases from two groups that are being compared), almost two-thirds of the cases were not markedly deviant from their respective groups on any of the indexes, and only two cases were markedly deviant on as many as three indexes. Robert S. Lee, "The Family Experiences of Male Juvenile Heroin Addicts and Controls" (doctoral dissertation, New York University, 1957), has reviewed the data on the three most deviant addict and the three most deviant control cases (i.e., on the six cases markedly atypical of their respective groups on two or three indexes), only to find that, if anything, the indexes did not do justice to the marked contrasts between the two sets of families. A similar conclusion seemed to be indicated in his contrast of the records of the three most typical addict and the three most typical control families. Incidentally, the addict who was atypical on three indexes, it turns out, may have achieved this position of pre-eminence because of insufficient evidence —that is, there was an exceptionally small number of items relevant to the indexes on which we had enough information for scoring purposes; the computed indexes may, therefore, be quite misleading. It would, however, be surprising, indeed, if larger samples would not turn up more markedly deviant cases, especially among the controls.

CASE 44: RICHARD STONE, ADDICT

Richard Stone is a Negro adolescent addict. He was reared as the only child in a home with two women and no men, except for the first years of his life. At the time of this study, he had been using drugs for two and a half years and was a patient in Riverside Hospital at the time that his mother and grandmother were interviewed.

Prior to his birth, the relationship between his parents was amicable, predicated on his mother's superior attitude and condescending tolerance for his father, whom she regarded as "just a boy" who was shy and inexperienced with people. They lived with her mother throughout their marriage. Both parents worked, and, after Richard was born, Mrs. Jones, the maternal grandmother, was responsible for most of his care. The circumstances following his birth are unclear. On the one hand, we were told that he was breast-fed for the first two months of his life; on the other, it was stated that his mother spent six postnatal months in a hospital because she was so weak after his birth. Though this may have been a postpartum psychosis, we could not establish this from available records. It is clear, in any case, that, early in his infancy, Richard's care passed into the hands of his maternal grandmother, Mrs. Jones.

In his early childhood, both his parents continued to work, while his grandmother, who was the superintendent of the building in which they lived, took care of him. He learned to call his mother "Sister" and his grandmother "Mother." What he called his father is not indicated, but it is reported that the extent of his father's interest in him was limited to inquiring once daily about the state of his health. His father never picked him up, never took him anywhere, never concerned himself with Richard's discipline. His mother gladly relinquished his care to his grandmother, who described his childhood as uneventful. Richard was completely toilet-trained by eighteen months "He was always a very obedient child. He was not a fighter. When any child started up with him, he would run away and say that he is sick; he won't fight." He had "rickets of the bones," recurrent fevers, and a spot on his lungs. He was hospitalized for half-year periods at ages four, six, ten, -and fourteen years. His illness first expressed itself symptomatically as a sudden inability to walk when he was four years old, which led his mother to believe that Richard suffered from polio.

Richard wanted to be an affectionate child, but Mrs. Stone regarded "all that kissing and hugging as foolishness" for which she had no time. From his mother's willingness to give his care over to her mother; from her minimal retrospective concern for or recall of his development; from her attitudes toward his efforts to express affection; and from evidence in the interview of her contemptuous identification of her son with her husband, from whom she separated when Richard was six, it seems reasonably certain that the prevalent attitude Richard experienced from his mother was one of unqualified rejection. There was no apparent area in which she felt enduring, affectionate regard for him.

The relationship with his grandmother was quite different. It was extremely close—too close. Mrs. Jones's attitude was: "You must never drive a child away from you; you should draw him to you instead." She expressed the belief that a child wants you to drive him away, but, if you do this, then the "bad things from the street" will be instilled in him. Even in her own estimation, however, she spoiled Richard. He could get whatever he wanted from her because she was afraid that otherwise he might take it from someone else. She never permitted Richard to run around by himself, and she took him with her wherever she went. Richard shared her bed until he was fifteen years old. (It may be symptomatic of her feelings that, as she told about sharing the same bed with her grandson, Mrs. Jones placed her hand inside her blouse, grasping her breast.) Again and again, she stressed how extremely close they were.

She taught him his arithmetic with clothespins and discussed religion and life with him every evening for many hours. Her ambition was that he should become a minister. Though they would discuss almost anything, Mrs. Jones never talked with him about what she called "common life," that is, sexuality. In her opinion: "If you teach life to a child, he has no cause to stay away from it. Children know too much, anyhow. When their mothers are pregnant, they know about it months in advance and say: 'Are you going to have a baby? I hope it will be a boy.'" She told her children that Santa Claus brings the babies. Religion and the reading of the Bible played an enormous role in the grandmother's life. There were many crosses, religious pictures and calendars, and quotations from the Scriptures hanging on the walls of the apartment. Mrs. Jones also looked back to the time when she was a house servant in a white Southern family, where everything was clean and nice, as the best time of her life. She believes that man should earn his bread by the sweat of his brow, as it says in the Bible, and that people in the city are bad because they want to live in ease and comfort.

It seems clear that Richard's early childhood situation was pathological. Continuously perceptible parental rejection and neglect vied with the grandmother's overprotectiveness and overindulgence. Attitudes of sexual prudishness contrasted with seductive intimacy. Hypermoralistic religiosity was coupled with yielding to the slightest of whims The illusion of omnipotence generated by overindulgence was shatteringly denied by the impotence in evoking any positive response from affectionate overtures to the mother and by the grandmother's smothering of any gesture toward independence or socializing with peers. It was a situation in which conflicts over aggressivity and passivity must have been sharp. It was one in which invitation to feminine identification must have been strong and in which there was no appropriate model for masculine identification. Although it is unlikely that his illness at age four came about for psychological reasons, it is not at all unlikely that such a motor inhibition must have had serious psychological consequences, concretizing unconscious anticipation of bodily harm as a penalty for sexual interest and fantasies which must have been repeatedly stimulated by the nightly physical proximity and by hugging and kissing in bed with his grandmother.

In 1941, when Richard was five years old, his father was drafted into the Army. When he returned from service three years later, he behaved in a completely changed manner. Instead of being the docile and submissive husband who worked and brought home his pay check, he began to drink heavily. He ran around with other women. In Mrs. Stone's words, his father thought he was "a real big shot," who never bathed and who would not work. Indeed, he did not even live with his wife, but stayed mostly at the home of his aunt, who had reared him. After six weeks of intermittent contact, during which he resided with his wife and son in periods of sobriety, he finally left for good when his wife refused to give him money. She said that she was tired of supporting him with nothing in return for herself. Since then, Mr. Stone has worked irregularly, has apparently been supported by various women, and it is very likely that he earns his living as a procurer. Mrs. Stone believes that all men are this way, or at least that every man she has ever known is this way. She describes her husband as a man who never liked to be with friends, did not talk much, but liked the best clothes and had big ideas. She believes that her son is like his father. In fact, she says that they look like twins.

We get some further picture of Richard as a young boy from the statements of both his mother and grandmother. He was always a good boy, the nicest and kindest boy in the neighborhood, and always quiet. He preferred to play with younger children. He was afraid of being whipped and was consequently extremely docile.

His mother now believes that Richard has the same need for drugs as his father has for drinking. Richard used to be a quiet and good boy, the best boy in the neighborhood, but now "he stays around with garbage," with "the bums on the block." He started his foolishness when he was in junior high school when he met some very wild boys. His mother compares this change in Richard to the change that occurred in the father when he was in the Army. "After he met some bad boys, he was crazy. He never stayed home; he always wanted to go out somewhere drinking. He thought he was a big shot; he would talk a lot about all the big shots he drank with, some of his Army buddies."

Throughout the interviews, both the mother and grandmother made much of their veneration of cleanliness. For example, the grandmother wished that the neighborhood would be tom down and replaced by projects, because then at least there would be cleanliness, which would be good for the people. But, in marked contrast to their expressed concern for cleanliness, our interviewer was impressed by the extreme clutter, darkness, and pervasive stench in the apartment. All the rooms were in a mess, the beds unmade, the dishes unwashed, the religious symbols in scattered disarray, the rooms extremely poorly illuminated. The important point is not that the apartment was so poorly cared for, but rather the extraordinary discrepancy between these expressed interests and tastes of the two women who are the major figures in Richard's life and the way in which they actually live. Whether this expresses a pervasive attitude of passivity and helplessness, intense ambivalent attitudes wtih regard to cleanliness, or both, we can only conjecture. In either case, any such marked discrepancy between expressed values and actual style of living must be a bewildering and harmful experience for a developing child.

CASE 58: JAMES MCGILL, ADDICT

McGill is an Irish-American drug addict. He and his family differ strikingly from Richard Stone and his family. He has always lived in private housing developments with his parents and, as they came along, with four younger brothers. His father does not drink excessively, as did Richard's father; nor is he unstably employed; nor manifestly uninterested in James's life and development; nor, in the gross terms of our indexes, did he offer an unseemly model with whom James might identify. Again in the gross measures of our indexes, James had far fewer pathological experiences and relationships than had most of the addicts in the group. In at least the superficial aspects of his life experience and relationships, it would seem that he has been favored by fate and fortune.

James's father is a civil servant. His mother did not work during the course of James's childhood. About a year before these interviews, after James was already thoroughly addicted, she became a hostess at one of a chain of dignified ladies' tea shops in New York City.

Certain circumstances associated with James's birth were somewhat unusual. He was born after his mother had had a number of miscarriages, and, in the three years following his birth, there were several additional miscarriages. Thereafter, she conceived and bore four more sons. As a young child, James was apparently healthy. He seemed to adapt well to the regime of his parents. At one year, toilet training was begun; by eighteen months, he was dry and clean. At age three, he had an appendectomy; at thirteen, he had asthma. During some period of his childhood, he was said to have been markedly overweight. Until he was fourteen or fifteen, he bit his nails to the quick.3 From any one of the manifestations of obesity, asthma, and nail-biting, one might infer that James had difficulty, in Erikson's phrase, in negotiating the oral phase of psychosexual development; from their conjunction, the conclusion seems virtually inescapable. We do not, however, have any data that might pinpoint the precise nature or the source of the difficulty.

It is impossible to specify the period during which James suffered from obesity. In one interview, his father stated that the period of James's obesity extended from the time he was six until he was nine years old. In another, his mother said that James became overweight after his appendectomy, that is, after age three. In a third interview, his father rationalized those of James's social difficulties which occurred when he was nine to twelve as due to obesity.

Though both his mother and father spoke a great deal when they were interviewed, there was a remarkable emptiness of communication about James's development and a vagueness about his relationships and reactions. Everything "was at the usual time"; but, for emphasis, Mrs. McGill added: "He wasn't at all advanced." At the age of two, he had the one overt temper tantrum of his life; this was while he was with his father, who walked away from James as though he had no connection with him. This, by the way, was described as singularly effective and commendable behavior by both Mr. and Mrs. McGill; indeed, they both were pleased to regard their child-rearing with composure, if not with self-satisfaction.

The vagueness about James's obesity was not the only area of vagueness. Though there is a considerable range of ages between her sons, Mrs. McGill seemed quite unable to sort them out in terms of their special behavior, characteristics, or problems. She seemed insensitive to them individually, except, signfficantly, with regard to issues of obedience. Even here, however, they did not seem to stand out sharply from one another in her mind. During James's adolescence, he stretched the limits to the point of quarrels with his father. For instance, Mr. McGill made quite a fuss over the fact that Larry, the second son (who, incidentally, was given somewhat more freedom than was James), would be home by 9:30 on a summer's evening, whereas James did not get home until 10:00.

At present, there are four boys in the house, which is spotless and quiet, even though the boys were home while the interviews were going on. They are trained to go to their rooms, come when called, and are always dressed neatly—or more than neatly. They are expected and accustomed to wait, even when waiting is clearly not necessary. For example, when the doorbell rings, Mrs. McGill does not answer it. Though she may be sitting only a few paces from the door, she lets whoever has rung wait and does not get up to open the door until the bell has rung two or three times. On one occasion, a year prior to these interviews, James returned late in the evening and rang the bell; his parents decided to wait until he rang again. He did not; instead, he spent the night in the streets. There is little sense of warmth or interpersonal activity in the household; instead, there is an atmosphere of extremely efficient and disciplined interaction.

Mrs. McGill does not like to lose her composure. Her life is stiff and controlled; she is not given to affectionate or easy interaction, nor is she Able to express anger or annoyance with ease. In fact, on the few occasions in her life that she could recall in which she had expressed anger or annoyance, she felt tense and self-reproachful as a consequence. She is very concerned with proper deportment, manners, and cleanliness. The house seemed to be spotless, yet, when our interviewer commented on this, Mrs. McGill responded: "Oh, there's lots of dirt still here, if you only know where to look for it." She is extremely concerned with social status. She strives for increasing status, but with measured tread; it is not seemly to seek too much too fast. She glosses over or lies about those facts in her life which might lower her status. For example, she is extremely evasive and ashamed of the fact that, during one phase of their married life, her husband worked as a waiter; he did not always have a white-collar job, and, even after he obtained one, he continued to work as a waiter on a part-time basis. Her younger children had not been told that James was in the hospital. She maintained the fiction that his work required a peculiar schedule so that he was never home on weekends, did not come home during the evenings until after his brothers—aged fifteen, ten, eight, and six—were asleep, and left before they awoke. None of the neighbors or their families were supposed to know that James was in a hospital.

Her relationship with James and, for that matter, with her husband and the other children, is and has been superficial and without warmth. The entire family attends Mass every Sunday—religiously, one might say, but not with any depth of religious feeling. Toilet-training was accomplished, manners practiced and attained. Until James was seven, he expressed appreciation by hugging and kissing, but, when he "grew away from this," Mrs. McGill was not at all regretful. Since James had begun to stay out late, become a truant, and taken to drugs, Mrs. McGill had felt "terribly ashamed," but in none of the interviews did she express anxiety, intense concern, or unhappiness for James's sake.

Some indication of her difficulties in the expression of aggression and anger is discernible in her relationship to her husband. She adheres closely to his opinions and strictures, even when these run contrary to her own views. But she constantly expresses fear for her husband's health and has threatened James and the other children with his high blood pressure: "What if your father, with his high blood pressures fell down some stairs? Then where would you be?" She encourages him to take over household tasks (she has never washed a diaper in her life e—Mr. McGill did—and this before the era of the automatic washing machine), but she will not let him clean the windows for fear he might fall out—a fear behind which one may suspect a lurking wish, since he has never fainted nor experienced dizzy spells or disturbances of equilibrium which might justify such apprehensions.

James's relationship with his father is quite a different matter and indeed rather unusual in the background of the adolescent addicts. Throughout early childhood, James hung on to his father's apron strings. Mr. McGill took care of much of the cooking, cleaning, and child care, although Mrs. McGill was not working nor burdened with many children. Furthermore, whatever demonstrative affection James received, he probably got from his father. This all occurred in a lower-middle-class, prewar setting in which such behavior was conspicuous, if not indecorous, and in which there was none of the ideological emphasis on "sharing" responsibility for child-rearing and household work.

Also somewhat unexpected were Mr. McGill's theories of child-rearing. He himself had "been brought up with all kinds of fears" and did not want his children to be brought up this way. He did not want his children to be afraid of the policeman and the dentist (as he himself had been?) and took measures to prevent them, e.g., by providing opportunities for acquaintance and play with policemen and dentists.

From age four until eight or nine, James was inseparable from his father. Each day when his father returned from work (his job permitted him to get home about 3 in the afternoon), James would be his companion in a walk to the river. The babble of childish enthusiasm and adult response which makes the walking together of fathers and sons a valid and touching human interplay was absent from their walks; they walked in solemn silence. Where did their relationship come alive? Only in anger. Though Mr. McGill was consciously concerned with raising fearless children, James learned to listen with fear and resentment to his father's temper tantrums. By the time he was eight years old, it became evident that James was neither extraordinarily intellectually gifted nor impelled toward a life of learning for any other such reason as parental cultural achievements or interests. His school work was, at best, average. For this, Mr. McGill would scream at James, insult him, and urge him to exert greater efforts in his studies. James's response to these explosions over his school work was to conform outwardly to his father's demands. He did sit at his desk with his books from 7 to 9 in the evening, but he did not really study.

Both Mr. and Mrs. McGill were proud of the fact that James never fought back when his father scolded him. However unreasonable or uncontrolled Mr. McGill might be, Mrs. McGill supported him. On one of the few occasions that James came to her in tears after one of his father's tirades, she told him that his father behaved this way only for James's own good, that, if his father did not care for him and did not care about what happened to him, he would not talk to him this way. James was regularly confronted with his own shortcomings and expected to regard his father as always reasonable and always fair.

The overt emphasis on conformity and suppression of feeling is sufficiently clear. Nevertheless, there is some reason to suspect that Mr. McGill warmly accepted the fact that James did not really conform. For example, granted that a person may be stirred to intense anger by evidence of one's child's shortcomings, one would hardly expect that this anger would be completely appeased by the most superficial conformity; yet that was typical. As soon as it became evident that James was going through the motions of study, the tirade ended—until the occasion for the next one arose.

There are many episodes in James's recent life where delinquent or aggressive and inappropriate behaviors were supported by his father. For instance, a few months before our interviews, James was home on a weekend pass from the hospital. He was near a candy store, where he met a group of boys whom he had known most of his life; these boys were not drug-users, and they had not seen him for some months. One of them asked: "Been away on a vacation?" James ignored the questioner. He walked into the candy store, bought cigarettes, and then came out and hit this boy in the jaw. Mr. McGill approved of this; he identified warmly with James in telling about the incident, as though this were a reasonable response to a question about a person's whereabouts (which may or may not have carried the implication that James had been in some jail).

About a year prior to our interviews, "James had got into trouble once before." After buying a "jalopy" against his parents' advice and without their knowledge, he had a hit-and-run accident. This was "fixed up" by his father. When James was arrested for drug-connected activities, Mr. McGill again wanted to "fix it" and was extremely unhappy that he could not. At each of James's numerous episodes of truancy and school failures, his father made visits to school to "fix it up." When-Mr. McGill learned that James was using heroin, he felt that he would kill the man who introduced him to drugs. In short, whenever James got into outside trouble, that anger which flowed so freely at home was absent, replaced by sympathy and support for James in his troubles with the world. On the one hand, James was cajoled, screamed at, and insulted in the hope of impelling him toward scholastic achievement, good behavior, and self-control. On the other, he received his father's warmth, support, and defense whenever he misbehaved—often seriously —away from home. From the standpoint of his developing goals, ideals, and controls, what is relevant is not merely that he was reared in a setting of rigidity, suppression of feeling, emphasis on cleanliness, status consciousness, and ambition, but that this took place in a climate of conspicuously inconsistent morality.

CASE 62: DOMINICK CORDOVA, ADDICT

Dominick Cordova is a Puerto Rican addict. He is the youngest of five siblings, born three years after his only sister. He and his siblings were all born in the United States. At the time of his birth, his parents had been living in this country for twelve years. His birth and childhood were without special incident of illness, injury, or other conspicuous trauma. Like James McGill, he was obese as a child, although no problems in socialization were imputed to this.

His mother reared all her children "exactly the same way." Nobody could tell her, nor did she inquire at any clinic or from any physician, when they should be weaned, when they should receive solid foods, when or how toilet training might be accomplished. Each child was weaned from the breast at six months. By age two, every child had to feed itself—neatly. At seven months, they were completely toilet-trained. They never wet their beds thereafter. She plans that her grandchildren be fed and trained the same way. She knows that this is the right and best way.

We do not know what Mr. Cordova contributed to his children's upbringing. By the time Dominick was four, his father and mother had separated and divorced. Thereafter, his family was supported by the Department of Welfare. Their home has been in a slum area of New York City, but the apartment was always kept neat and orderly. Mrs. Cordova has little or no contact with her own family of origin, and there were no relatives by whom her children's lives could have been enriched or otherwise influenced.

Mrs. Cordova's inflexibility and definiteness of opinion extended into all aspects of the socialization of her children. She was concerned that they not be regarded as "Spanish children." For instance, Dominick wore a clean white shirt to school every day so that the teacher would not think that he was "like the other Spanish children." Her children were kept together as a group. They were not allowed out on the streets like the other children of the neighborhood; instead, she gave them things to do in the house. She is proud that her daughter is not like some girls who cannot cook, clean, sew, or do the things necessary for the home. She is proud that Dominick can do all these things, too. He can cook, do housework, and wash clothes "as good as any woman." People used to tell her that she should not keep the children in the house so much. Despite this, she did so. They all played together in the same room, and they were never rowdy, nor did they ever tear up things. When they went out, it was always as a family group, from mother to the youngest child.

Discipline was "no problem." All the children were well behaved. She never had to whip them. She just spoke to them, and they obeyed. They were all good. They had a reputation; and they never spoke back to her. On one occasion in the past year, when Dominick spoke disrespectfully to her, she slapped his face. She knew that he behaved this way only because he was taking "that stuff" at the time and that he would never talk back to her otherwise. (We agree.) Despite (because of?) the extraordinary and enforced closeness of Mrs. Cordova with her children, her present relationships with her children are meager. She is disappointed in all of them. The only one to whom she is close is her daughter.

Although she has lived many years in this country, Mrs. Cordova does not read English at all. This is extraordinary for several reasons. First, she is already literate in Spanish. Second, she speaks and understands English well. Third, all five of her children were educated in American school systems. Fourth, we have already noted her concern that her children should escape what she regarded as the stigma of being identified as Spanish.

She belongs to no churches, nor has she any knowledge of community house or neighborhood activities. Since she seems intelligent and observant and is ambitious, this is another indication of her self-isolating behavior. In this regard, we were impressed by her growing suspiciousness of our interviewer. Mrs. Cordova persistently doubted her integrity. She suspected that the interviewer, despite her credentials, was actually ferreting out information about Dominick and his life to make a newspaper story. Indeed, the last exchange between Mrs. Cordova and the interviewer was a request that the latter write down her name so that Mrs. Cordova could check on her again through the hospital.

To this point, we can observe some of the general characteristics of the familial situation in which Dominick was reared. He was brought up by a repressive, domineering, inflexible mother who isolated herself and her children from the dangers—and, incidentally, from the opportunities for growth—afforded by her environment. We note—as we did in Richard's case and as seems to be the usual state of affairs in the family background of adolescent opiate addicts—the small role played by an adult male figure in Dominick's life.

But probably the most important facts about Dominick's early experience have to do with his succession to the only girl in the family. Unlike his older brothers, who were equally regarded—or, in a more profound sense, disregarded—by their mother, Dominick's early childhood must have been full of evidence that his mother preferred another. His sister, Cora, who was three years older than he, was Mrs. Cordova's pleasure, hope, and pride. When Cora was born, Mrs. Cordova found the one object she could really pamper, indulge, and, in a sense, love. Dominick was another unwanted male child who could only interfere with her devoted attention to her daughter. This was so evident that Mrs. Cordova had to excuse herself frequently and rationalize her preferential behavior toward Cora by asserting that girls inherently need more than boys. Parenthetically, Mrs. Cordova was, herself, the oldest girl in a sizable family, but, rather than being the preferred and favored child, she was body servant and maid-of-all-work to the others in the family.

Though Mrs. Cordova and her children were supported by the Department of Welfare, somehow she found the means of having Cora trained to become a ballet dancer. Now that the sons are scattered around New York City, Mrs. Cordova and Cora, now married, occupy separate apartments in the same building. Cora gave up her career as a dancer (unlike her ballet classmates, who now are dancing throughout the country) and has earned her living as a typist in a bank. Mrs. Cordova is disappointed by Cora's abandonment of a career as a dancer, but Cora is still the apple of her mother's eye. Mrs. Cordova went out of her way to introduce Cora to our interviewer and tried to arrange for the interview to take place in her daughter's apartment rather than in her own.

When Dominick was fifteen, Mrs. Cordova tried to have him committed to a state school for wayward minors. Since his misbehavior was limited to truancy without other delinquency, the judge refused to commit Dominick and instead scolded the mother. In Mrs. Cordova's present contacts with Dominick, she has told him, as she tells us, that, if he were to return to his old habits (not holding a job steadily, hanging around with drug-users, and so on), she would have nothing more to do with him. Dominick's mother is quite capable of carrying out her threat to have nothing more to do with him. When she cuts someone out of her life, she cuts completely and thoroughly. When she separated from her husband, she moved out of the apartment in which she had reared her children, so that there would be no stimulus to remember that there had ever been a father in the home. She is emotionally so withdrawn from her husband that she will not even complain, criticize, or be angry with him. She asserts, with no special feeling, that he was a fine man and that "he had a good reputation."

CASE 17: JOHN CRAWFORD, CONTROL

The Crawford family lives in a predominantly Negro slum area in lower Harlem. The household is overcrowded. In addition to Mrs. Crawford and John, her oldest child, there are a grandmother, an aunt, John's two sisters, and a foster child.

Mrs. Crawford and her husband separated when John was eight. According to Mrs. Crawford, her husband had an unstable work history, did not provide adequate financial support for the family, and, in fact, was rarely home. According to her: "He was always out of the house, drinking and running around." For a while after the separation, she was kept busy running to the Family Court in repeated efforts to get Mr. Crawford to pay for the support of the children. Eventually, the family had to seek assistance from the Department of Welfare. After the separation, John continued to see his father occasionally until about a year before our interviews.

According to his mother, John was never any trouble to her. He was always a quiet boy and a good student. He was quite precocious. She says that he not only walked by himself by the time he was eighteen months old, but that he already could count at that age. As early as five, John began to contribute to the support of the family by turning in what he could earn by shining shoes. Although he later began college, he dropped out in order to support the family. John now "works for a big company, and he got the job by passing a test."

In fact, John is the man of the house in other ways, as well. For instance, Mrs. Crawford says that John sometimes loses his temper when disciplining his youngest sister and may slap her. "You've got to have a father in the house. So I let John take over. I never interfere when John disciplines Margaret. I can't do it all myself, and it's good to have someone to rely on." This is not simply a recent development, for Mrs. Crawford has apparently always pushed him toward the assumption of responsibility.

The relationship between John and his mother is a close one. Although she struck our interviewer as a rather aloof person in the course of the several contacts with her, Mrs. Crawford has warm, motherly feelings toward John and takes great pride in his accomplishments. In return, John discusses things with her and confides in her. At the time of the interviews, John had been "going steady" for about a year and a half, but our interviewer thought that she detected a note of relief in Mrs. Crawford's assessment of the relationship as not yet having "reached the serious stage." Mrs. Crawford does, however, have apparently realistic plans for her own future. She has a skill that can be developed as a basis for earning her livelihood when her most pressing homemaking responsibilities diminish.

Academic achievement on the part of the children is very important to Mrs. Crawford, and she has particularly pressed John in that direction. She sees herself as both culturally and morally superior to her neighbors, with whom she does not socialize. She hates Harlem and would like to live elsewhere. She feels that her values differ from those of the others who live nearby, and she speaks with contempt of the women on the block for their lack of interest in the activities of their children. She feels that the children are permitted to stay out too late and that the mothers are generally irresponsible in not knowing where their children are. At the time of the interviews, Mrs. Crawford was especially concerned about her youngest daughter, Margaret, and made a special point about not liking to see her come home late, "because there are dope-pushers and alcoholics on the stairs of this building." She was also concerned about the sexual immorality prevalent in the neighborhood. "The' mothers around here don't seem to care about their girls. That's why you see them going to school in the winter and walking baby buggies in the spring." That she recognizes that there are limits to the protection a mother can provide and that a child who yields to the pressures of a bad environment is still entitled to parental support is indicated when she adds: "I hope nothing like that will happen to Margaret, but, if anything did, I would stand by her."

We do not know much about the quality of John's relationships to the other members of the household or about their relationships to one another.

There are obviously features of John's home environment that, taken by themselves, cannot be regarded as wholesome—most notably, a father whose irresponsibility, incompetence, and profligacy set a bad example and the total absence of any adult male in the household during the latter part of his childhood and adolescent years. The pressures of economic adversity and toward the premature assumption of familial responsibilities are not normally favorable circumstances, either. There were, however, also compensatory features in his situation, in part determined by his own precocity. Most notably on the favorable side of the balance was his warm and close relationship with his mother, who, despite the fact that she may have pressured him too much for comfort, nevertheless respected his integrity as an individual and accepted and nurtured his sense of masculine initiative and competence in a household where it could easily have been crushed. John's home did not provide an appropriate model of manliness with which he could identify, but his mother, perhaps because of her own dependency needs, nevertheless found the means of showing him the way. She did not find in him a sexual object on which to play out the repressed themes of her own unfulfilled sexuality. Perhaps these needs were not very strong, perhaps they were otherwise satisfied, perhaps they were effectively repressed—we do not know; but she did find in him, and helped him to discover, a man. Moreover, in her own person, she offered him a model of one who does not passively accept defeat, but who continues to strive in adversity; and she demanded of him, somehow without overwhelming him in the process, that he live up to the model.

CASE 30: LOUIS HORA, CONTROL

Like John Crawford, Louis Hora is a product of a broken marriage. He lives with his mother, stepfather, brother, and half-brother in a spotless, attractively furnished, and well-equipped apartment in a dirty apartment house in a run-down Manhattan neighborhood.

Louis' father has returned to Puerto Rico, but Louis still keeps in constant contact with him and his paternal relatives by mail. He writes to his father for guidance and consults him on every important move that he contemplates. Mr. Hora has always urged Louis to aim at a higher occupation than that of a factory hand, and the letters from the relatives are full of admonitions to work hard, not to play too much, and not to waste his time.

According to Louis' mother, Mr. Hora had been very strict with the boy and, indeed, she describes his entire family (to whom she laughingly refers as "a bunch of old goats") as extremely pious, moralistic, strait-laced, and industrious. Mrs. Hora describes herself as having shared fully in this disciplinary approach, and, between her and her first husband, the boy was watched over constantly and given little opportunity to get into trouble. At any sign of misbehavior, a "look" was sufficient to institute control.

Despite Mrs. Hora's self-characterization as a full partner in setting a stern disciplinary regimen for Louis, the interviewer who had an opportunity to observe mother and son together described their relationship as a warm one enriched with humor and mutual tolerance. During one of the interviews in which Louis acted as interpreter for his mother, who speaks little English, Mrs. Hora enumerated a list of illnesses from which her present husband suffers, and the two of them were greatly amused at the length of the list. They spoke of the stepfather with a sort of amused fondness, as though he were a rather pleasant addition to the household, rather than the head of it. In another context, the mother referred to the fact that Louis may bring friends into the house for parties and added that, if there is too much noise, she goes out.

The point is not that Louis' mother exaggerates her standards or that she is indecisive in applying them to her children; far from it. She clearly gives the impression of being a strong and purposeful individual and that it is she who takes the lead in making family decisions. But she keeps things in a good-humored perspective and makes allowances for the needs of the other members of her family even if these involve some inconvenience. This is why she is rather contemptuous of Mr. Hora's family. It is not that she deprecates their standards, but their rigidity and their failure to discriminate between essentials and nonessentials.

Louis' stepfather, Mr. Domingo, is described by the interviewer as a warm, friendly, rather emotional man in his fifties. He formerly owned a small retail establishment, but a series of illnesses had forced him to retire. He seems to be quite fond of Louis, whom he has known since the latter was nine years old. According to him, Louis has never been in any trouble, and, if there was any issue of discipline, all that was needed was to talk to him, although "sometimes he talked back. You know, the way a kid does."

Louis himself is described as a boy content to stay around the house most of the time. He never wanted to play with older boys who might lead him into trouble. He has belonged to the Boy Scouts for many years and also to a number of other organizations.

In line with his father's admonitions, Louis has always wanted to enter some profession and, for some years, has aspired to become a physician. This was, however, considered beyond the family means, and they did not believe that he would be able to win a scholarship. Recently, therefore, be settled upon optometry (a decision that was facilitated by the fact that Mr. Hora himself was, at that point, also preparing to become an optometrist in Puerto Rico), and he has just received a letter in response to his application requesting him to appear for an interview.

CASE 21: THEODORE SPINNER, CONTROL

The Spinners live on the top floor of a dirty, ill-kept walk-up tenement in a slum neighborhood in an immaculate apartment that shines with cheerful chair covers and polished, old-fashioned furniture.

Mr. Spinner had to leave Ireland as a consequence of his political activities, and the fact that he had to leave home and give up his ambition of becoming an accountant left him all the more embittered toward the British. In quick succession, an American friend helped him to find two jobs after his arrival in the United States, but he could not stand either and gave them up. One of these was as a house detective in a hotel, and a major part of his responsibilities was to keep an eye on the cleaning women, lest they steal something; it took him half a day to decide that this was not a career he could stomach. On another occasion, he was offered a job on the condition that he not let it be known that he was Catholic; although there were to be no restrictions on his religious practices, Mr. Spinner felt that accepting the condition of secrecy would amount to denying his faith, and he refused. Eventually, he took a job as a laborer and has kept it for the past thirteen years. There are a number of other instances that could be adduced to indicate Mr. Spinner's quiet but prideful and firm insistence on not compromising his principles and on acting in accordance with his convictions.

Mr. Spinner prefers to leave the financial and disciplinary affairs of the household in the hands of his wife. Concerning his role as head of the household, he laughingly remarked: "Let's face it, the women always make the decisions." To his son, he displays a great deal of quiet warmth and interest. They frequently go together to baseball games, even when Mr. Spinner himself would rather do something else. He also lets Ted pick the time when he tries to get his vacation so that it will coincide with the games Ted most wants to see.

Mrs. Spinner gives the impression of being more outgoing and self-assertive than her husband. She, too, left Ireland, but in her case because she could not find work in the old country. She met Mr. Spinner on the boat, where she married him, as she said, doubtless tongue in cheek, "out of sympathy" because "he had no one to come to in the new country." She is more community-oriented than her husband, more articulate, more bitterly critical of the social ills she sees around her. She and her husband have tried to protect their children from becoming aware of some of the unwholesome things that go on in the neighborhood, e.g., the use of narcotics. She has told Ted that masturbation is sinful, but has also assured him that he could freely tell her about it if he had done anything wrong. She considered it a punishment to say: "I don't know why I love you so much."

She does not approve of discrimination against minority groups, but she does believe in the rightness of segregation. At the same time, she is quite undisturbed if her son has an Italian or Puerto Rican friend. She is glad that Ted does not have girl friends who would interfere with his school work. She is proud of the accomplishments of all of her children, especially of Ted's school achievements. She does not, however, try to discourage his participation in sports or in the social activities of the church.

Mrs. Spinner approves of her husband's sticking to his convictions, even when this meant losing a good job, and this despite a strong desire on her part to move up the social scale.

The interviewer describes Mrs. Spinner as warm and friendly, not only in her accent and personality, but with a warmth reflected in the very possessions which surround her. She is a charming, pleasant-faced woman, with a calm way of speaking, great politeness, and a somewhat sad smile.

Tlw family is a cohesive one, all of its members seemingly oriented to family and home life, enjoying the home and doing things in it; yet each is independent of the other, with independent interests and friends. Religious feeling and action are manifest throughout. The mother is the primary and active authority, but the children know that she has the agreement and backing of the father. Both parents try to protect the children from bad influences by discussion and by reasonably defining the kinds of activities and friends to be permitted.

Obviously, one cannot base great generalizations on six cases. As indicated at the beginning of the chapter, our reason for presenting these summaries was to provide some concrete illustrations of the kinds of home life experienced by a few boys, some of whom became addicts and some of whom proved resistant to the pathogenic influences of their neighborhood environments. If there is any generalization that can be gleaned from this group of cases, it is a negative one, based on two of the control cases: divorce is not necessarily disastrous to the children.

The intactness of the family is a surface manifestation; what matters, we think, is the history of personal relationships that lead up to the break and issue from it. The broken home is more likely to be one in which interpersonal relations are unwholesome, especially in the case of divorce. After all, divorce does not come out of the blue, and no one, to our knowledge, has ever explicitly suggested that divorces are made in heaven. All too often, in the case of divorce, neither parent is capable of sustaining the respect for the other's integrity and individuality that are required by an enduring intimate relationship. This incapacity is as corrosive of their relationships to their children as it is of their relationships to each other. That this is not necessarily the case is, apart from common experience, evidenced by the cases of John Crawford and Louis Hora.

Moreover, the case of John Crawford stands witness to the fact that there can be compensatory adjustments for even the total absence of an adult male model in the family. Indeed, in its own way, the case of Louis Hora makes a similar point; for, although the gentleness and emotive spontaneity of his stepfather must have had some attemjating effect on the model set by the reputed inflexibility of his actual father, Louis still, in the main, cast his ego ideal in terms of the latter.

On the other hand, the case of James McGill serves as a reminder that an intact family may provide a far from ideal developmental environment, and this in a home not marked by an unusual degree of friction between the parents. Obviously, there are marriages that do not —for religious, social, economic, and even psychological, sadomasochistic reasons—end in divorce, even though relations between the parents are as marked by vicious cycles of mutual irresponsibility, reciprocal frustration, clashing values, and incompatible purposes as are many marriages that do. The marriage of the McGills does not meet these specifications; there was a conscious effort on the part of at least Mr. McGill to establish a wholesome relationship with his son and to foster his psychological growth. Again one is pointed toward the subtleties of personal relationships rather than toward the grossly observable and easily describable aspects.

There is another rather striking aspect of the cases we have reviewed, one far removed from the issues of divorce and broken homes, that also points in the same direction. Running through five of the cases — all three of the addicts and two of the three controls—is a major concern with cleanliness and order. To be sure, this concern was most ineffectively implemented in the home of one of the addicts. We are not, however, directing attention to the actual degree of cleanliness, but to the spirit of the concern. In the homes of the controls, cleanliness and neatness were simply means of facilitating a good home life—people do not exist to be clean; cleanliness is simply a means of helping them to live better. In the homes of the addicts, cleanliness seemed to have become an end in itself, divorced from the welfare and happiness of the people who had to live with it. In the Stone home, it was not even something that people bring about by themselves; it was a state of grace that descends upon them through the providence of others. James McGill was constantly hamstrung by his mother's obsession with cleanliness and order and with the necessity for suppressing human feelings. Dominick Cordova had to learn to "play" with his three brothers and one sister in one room which never became disordered, and the one point of pride his mother could find in her son was that he could do housework like a woman.

Whether it involved cleanliness or countless other issues, this was a recurrent difference in the lives of addicts and controls. The spontaneity, flexibility, and warmth of the human relationships was paramount in the homes of the controls; the essential ignoring of the human being, whether through the application of inflexible rules of childrearing, home care, and conduct or through outright rejection or withdrawal was paramount in the homes of addicts. The addict fairly typically grows up in a home where he is an object to be manipulated and controlled, to be ignored except when he gets in the way of the grownups, or to serve as a target for poorly repressed impulses. The control typically grows up in a home where he is another person, to be responded to with the give and take that his personality implies, with respect for and adaptation to his needs and with appreciation for what he, as an individual, has to offer. The difference even emerges in the manifestations of religion in the family life. In the one case, it is formalistic, ritualistic, empty of genuine feeling, essentially manipulative or conciliatory of supernatural powers for the advancement of one's own ends; in the second, however prominent actual ritual may be, it makes for a sense of oneness and lends grace to the home.

These qualitative subtleties are so important that one may wonder that our indexes, based as they were on quite unsubtle matters, should have so effectively differentiated between the two groups. That the two groups did come out so differently with respect to the indexes is testimony, therefore, not merely to the grossly different patterns of familial experience, but to the fact that the subtle differences tend to go along with the gross ones. To take but one example: Relative to a boy's developing a clear sense of masculine identity, there is some likelihood that there will be adequate compensatory adjustment for the absence of a father figure during a significant portion of the boy's childhood; there is also some likelihood that, despite a father's presence throughout his son's childhood, other factors will interfere with the emergence of a clear sense of masculine identity. The first likelihood is apparently substantially less than the second; therefore, the absence of a father figure may be taken as predictive, albeit not perfectly so, that the boy will grow up confused with respect to his masculine identity. It was on the basis of such reasoning that we expected the ingredients of our indexes to work. Though we readily grant that we may have proceeded on false premises for some of the items included in the indexes, we cannot think of any compelling reason why the indexes should have discriminated the two groups other than that our reasoning was, in general, correct.4

The conclusion seems inescapable: the addicts grew up in, and, were at least in part shaped by, homes that were far less wholesome than those in which the controls were nurtured. The differences extend from the gross indicators of family pathology utilized in the indexes to the subtler features of personal relationships that are correlated with the gross indicators.

1 In order to protect the anonymity of the respondents, all names in cases have been changed; details which might help identify the subjects have been altered in inessential respects or omitted.

21n planning the study, we assumed that there would be substantial numbers of atypical cases among both the addict and control groups and hoped to be able to glean some useful insights from an intensive study of these cases. Actually, there were few, if any, cases that could be described as markedly atypical. This is indicated in the following table:

3 Both Richard Stone and James McGill have unusual health histories. This is a coincidence and is not a regular or predictable feature in the background of the adolescent addict.

4 We deal with an alternative explanation, interviewer bias, in Appendix M, where we have described the data that led us to reject this possibility. We have conscientiously tried to think of other alternatives and have felt compelled to dismiss those that have occurred to us. For instance, the use of an interview technique to explore the past is always fraught with the danger that the present may color the past. For instance, the parents of addicts may unwittingly darken the past histories of their wayward sons, whereas the parents of the controls—boys who have avoided serious trouble—may have brightened the histories of their sons. This possibility is not only precluded by the nature of the items we have included in the indexes, but, as illustrated by the six cases described in this chapter, is also precluded by the fact that the past differences are consistent with the observable present. Contrariwise, the contrast between the warmth and relaxation of the control homes and the coldness and tension of the addict homes may be a consequence of having had to deal with well-adjusted, as against maladjusted, children. That such effects are real, it seems to us, is hardly debatable; but then it is also hardly likely that the differences are of recent origin or that parents have been reacting over the years to their well-adjusted or maladjusted children, while the children have been pursuing their own inner growth potentials, uninfluenced by their relations to their parents.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|