5 European and non-European evidence of effectiveness of drug treatment

| Reports - Models of Good Practice in Drug Treatment |

Drug Abuse

5 European and non-European evidence of effectiveness of drug treatment

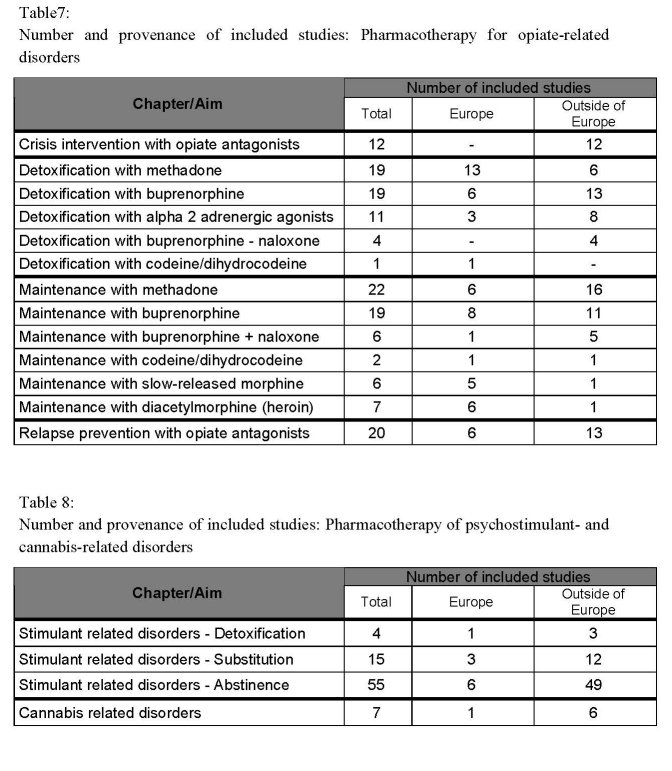

Results related to the effectiveness of drug treatment are based on research from all

available countries (inside and outside of Europe). In order to separate the studies

conducted in European States from those conducted outside of Europe, the country of

origin of all included references was identified. The number of included references was

counted for each chapter and allocated as evidence from a European State or from a

State outside of Europe. Usually it is indicated if the research was conducted in

European State, although the evidence of effectiveness is not influenced by the location

of the study concerned. Generally there are some reviews and systematic reviews on the

effectiveness of drug treatment conducted by researchers in European countries (e.g.

Berglund et al 2003; Rigter et al. 2004; Amato et al. 2007), but these reviews cover

research from all over the world as well. The methodology for the identification of

relevant literature is described in chapter 4.

5.1 Evidence from outside of Europe

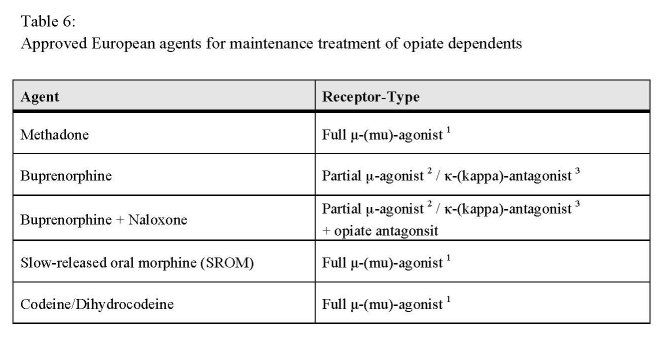

Pharmacological treatment agents for opioid-related disorders

Crisis Intervention

Use of naloxone and naltrexone for crisis intervention

Heroin overdose is one of the leading causes of death among heroin addicts (Sporer

2003) and non-fatal overdoses are highly prevalent among opioid addicts (Warner-

Smith et al. 2001). One study showed that 23-33% of injecting heroin users have taken a

non-fatal overdose in the last year, and 43% have witnessed a heroin overdose in

another user within the last year (Sporer 1999).

The short-acting opioid-antagonist naloxone is considered to be an effective substance

in treating respiratory depression and coma in patients with an overdose (Kaplan et al.

1999), This has prompted a discussion on a new strategy to reduce the risks of overdose,

by making naloxone available in addicts´ homes for peer administration in order to

prevent fatal overdose (Baca & Grant 2005; Lagu et al. 2006; Sporer 2003). A recent

study supports this recommendation by showing, that especially drug users with an

overdose history have a great willingness to administer naloxone in the case of a friend's

overdose (Lagu et al. 2006).

There is no evidence to suggest that subcutaneous or intramuscular routes of

administration are inferior to intravenous administration of naloxone (Clarke 2001),

where as another route, the nasal application of naloxone, seems to be comparably

effective to the intravenous application (Barton et al. 2005). Others studies investigated

the preventive effect of sustained release naltrexone implants, where initial findings

support the clinical efficacy in preventing opioid overdose (Hulse et al. 2005).

As a recent period of abstinence may lead to a reduction in tolerance and has been

shown to be a time of particular risk, the best prevention of heroin overdoses is

participation in opioid-assisted maintenance treatment. All opioid dependent persons

who opt for abstinence based treatment need to be made aware of the particular risk of

overdose after a period of abstinence. This is especially true when abstinence was

temporarily obtained through maintenance treatment with the long-acting opioid

antagonist naltrexone. Extended use of naltrexone can result in supersensitivity of the μ-

opioid receptors and an increased risk of overdose (Lesscher et al. 2003). Digiusto et al.

showed eight times higher rates of experienced overdoses in naltrexone treated

participants after leaving treatment, compared to participants who left agonist treatment

(Digiusto et al. 2004). Recently, Gibson et al. found the overdose-related risk of death

related to oral naltrexone appears to be higher than that related to methadone treatment

(Gibson et al. 2007). This results lead to an open discussion about the overdose-related

death risk of oral naltrexone.

In summary, the short-acting opioid-antagonist naloxone is effective in treating in

patients with an overdose. However, an extended use of opiate antagonists can lead to a

reduction of tolerance and therefore to an increased risk of overdose.

Pharmacotherapy of opioid withdrawal/detoxification

Withdrawal or detoxification treatment is a necessary step to enter a following drug-free

treatment and during detoxification various pharmacological substances can be used to

manage withdrawal symptoms, including (partial/full) opioid agonists (e.g. methadone,

buprenorphine), opioid antagonists (e.g. naltrexone) and α2-adrenergic agonists (e.g.

clonidine). The major goal of pharmacotherapy during detoxification is to relieve the

severity of opiate withdrawal symptoms in order to avoid unnecessary human suffering

and medical complications (e.g. epileptic seizures) as well as to enhance motivation to

continue treatment (Gonzalez et al. 2004).

Methadone as a detoxification agent (including methadone reduction treatment)

Detoxification treatment with tapered doses of methadone showed fewer severe

withdrawal symptoms and fewer drop out rates compared to placebo (Kleber et al.,

2007). Nevertheless, various patients relapse to heroin use and in comparison to

methadone maintenance treatment, methadone withdrawal treatment leads to high dropout

rates, even though the effect on the proportion of positive urine samples in both

treatment modalities remains high (Kleber et al. 2006). Because of the poor treatment

outcomes especially in rapid detoxification approaches (e.g. 10% dose reduction per

week) like taper interruptions, illicit drug use and withdrawal symptoms, a gradual

methadone taper (like 3% per week) is recommended (Kleber et al. 2006).

Higher doses of methadone for non-rapid detoxification were found to be more effective

than lower doses with regard to treatment retention and fixed methadone detoxification

programmes may lead to higher retention rates than flexible methadone detoxification

schedules (Kleber et al. 2006). Patients who are informed about the methadone

withdrawal schedule have better outcomes than uninformed patients, although patients

do not have better outcomes, when they control their methadone schedule on their own

(Gowing et al. 2001; Kleber et al. 2006). One Australian effectiveness report found that

detoxification with tapered doses of methadone is more likely to be completed if

withdrawal is scheduled to occur over a short period of time (21 days or less) (Gowing

et al. 2001).

Low doses of methadone were found to be equal to clonidine in the effectiveness to

suppress withdrawal symptoms (Gowing et al. 2001; Kleber et al. 2006). However, in

comparison to methadone treated patients, patients treated with clonidine were more

likely to leave the treatment early, possibly because opioid agonists suppress

withdrawal symptoms early in treatment (Kleber et al. 2006). No differences were

found between clonidine and low doses of methadone with respect to withdrawal

symptoms, but patients treated with clonidine tend to dropout earlier compared to

patients treated with methadone (Gowing et al. 2001; Kleber et al. 2006). Buspirone, an

azipirone used primarily as an anxiolytic agent, administered in addition to methadone,

could lead to a more rapid methadone taper with larger and more frequent methadone

decrements, but more trials will be needed to confirm this hypothesis (Buydens-

Branchey et al. 2005).

There is evidence to show that severity of withdrawal under methadone tapering can be

reduced by different psychosocial measures, such as having patients well-informed

(Green & Gossop 1988), contingency management (Hall et al. 1979) or counselling

(Rawson et al. 1983). Kleber et al. (2006) suggests combining pharmacological

treatment with behavioural and psychosocial approaches to increase efficacy (Kleber

2003). The recent Cochrane review found only one randomised controlled clinical trial

comparing inpatient and outpatient settings for opioid detoxification, suggesting that

opioid detoxification in inpatient settings is slightly more effective, but the underlying

available research remains limited (Day et al. 2007).

In summary, there is evidence that detoxification treatment using tapered doses1 of

methadone is associated with adequate rates of completion of withdrawal, reduction of

withdrawal symptoms to tolerable levels, and minimal adverse effects. Control by the

clinician rather than the patient of the rate of reduction of the methadone dose is

associated with greater reductions in methadone doses. Compared to the effects of

methadone in maintenance treatment, the efficacy of methadone for detoxification

treatment is limited. The attrition rate of methadone detoxification treatment remains

high, particularly in an outpatient setting compared to an inpatient setting. Despite the

findings related to methadone and α2-adrenergic agonists of one recent RCT, the current

systematic Cochrane review shows that methadone had better outcomes than other

opioid agonists in terms of completion rate, and patients have shown less severe

withdrawal symptoms.

Buprenorphine as a detoxification agent

The partial μ-agonist and κ-antagonist buprenorphine is a commonly used agent for the

detoxification treatment of opiate dependents, mainly in Europe and Australia. In the

USA, buprenorphine is commonly combined with the short-acting opioid-antagonist

naloxone. Like methadone, the detoxification treatment with buprenorphine is carried

out in a linear reduction schedule with equal dose decreases.

The efficacy of buprenorphine in the detoxification of opioid dependents is comparable

to methadone with regard to treatment retention, illicit drug use, and suppression of

withdrawal symptoms, though detoxification with buprenorphine can be completed

more quickly, within 3 to 8 days (compared to a normally duration of 14 days in

methadone detoxification (Gowing et al. 2007; Kleber et al. 2006). Also, no significant

differences were found between buprenorphine and methadone in terms of completion

of withdrawal, despite quicker resolution of withdrawal symptoms with buprenorphine

(Gowing et al. 2007). Furthermore, the current Cochrane review found that neither

buprenorphine nor methadone is associated with significant adverse effects when used

to manage opioid withdrawal (Gowing et al. 2007). The recent Cochrane review

suggested that gradual tapering of buprenorphine after buprenorphine maintenance

appears to be more effective than rapid tapering, but further research is needed to

confirm this assumption (Gowing et al. 2007).

Kosten and O’Connor (Kosten & O'Connor 2003) prefer buprenorphine over methadone

as their first choice opioid tapering and detoxification strategy, because withdrawal

symptoms of methadone last longer than those of buprenorphine. Conventional inpatient

detoxification (clonidine and other medications for a mean of 3.5 days) was found to be

more effective in achieving initial abstinence than outpatient detoxification using

buprenorphine (Digiusto et al. 2005). Only 12% of patients treated with buprenorphine

in an outpatient setting achieved initial abstinence compared to 24% of patients in

conventional inpatient treatment (Digiusto et al. 2005), although outpatient

detoxification was found to be more effective with buprenorphine than when

conventional symptomatic medications (e.g. clonidine) were used in an outpatient

setting (4%) (Digiusto et al. 2005).

Assadi et al. (2004) suggest that opioid detoxification using high doses of

buprenorphine (12 mg) in 24 hours is a reasonable approach to reduce the time required

for opioid detoxification (Assadi et al. 2004). One group of twenty patients were treated

with 12 mg buprenorphine in 24 h, the other patients received conventional doses of

buprenorphine tapered down over 5 days. No significant group differences were found

regarding treatment retention, severity of subject-rated opioid withdrawal, and side

effects profile. Patients treated with a high dose of buprenorphine in 24 hours,

developed early the maximal withdrawal symptoms, and patients in the conventional

protocol group were more likely to use more adjuvant medications for symptom

palliation. However, larger studies are needed to confirm these results.

Buprenorphine tapering was found to be more effective than clonidine or clonidine

combined with naltrexone for the management of opioid withdrawal, especially in the

suppression of withdrawal symptoms (Gowing et al. 2007; Kleber et al. 2006).

Buprenorphine probably improves withdrawal symptoms better than clonidine (Gowing

et al. 2001). Furthermore, buprenorphine has fewer cardiac side effects than clonidine

and methadone (Gowing et al. 2001). Compared to clonidine, buprenorphine has also

more positive effects on well-being and psychosocial variables (Ponizovsky et al. 2006).

Collins et al. (2005) found no significant differences, but greater rates of treatment

retention and naltrexone induction in patients detoxified with buprenorphine than in

anesthesia-assisted or clonidine-assisted heroin detoxification, but no differences in

completion rates of inpatient detoxification and opioid free urine samples (Collins et al.

2005).

A recent proposal is to detoxify heroin addicts with a single high dose of buprenorphine

(32 mg), because the combination of a high dose, the relative long plasma half-life and

the slow dissociation kinetics of the drug from the opioid receptors seems to create a

slow and effective tapering process (Kutz & Reznik 2002). Future research should focus

on determinants of withdrawal following cessation of buprenorphine in tapered doses

and the optimum approach to withdrawal following long-term buprenorphine

substitution treatment. Also the effectiveness of buprenorphine for managing

withdrawal from methadone as compared to withdrawal from heroin still remains

unclear, even though some studies indicated that the use of buprenorphine for the

management of withdrawal from methadone is feasible (Gowing et al. 2007). Also more

information is needed about the transition from methadone to buprenorphine, which can

lead to precipitated withdrawal (Johnson et al. 2003).

In summary, buprenorphine seems to have similar efficacy as tapering doses of

methadone for the treatment of opioid detoxification with comparable effectiveness in

improving withdrawal symptoms and in completing detoxification treatment. Compared

to clonidine, buprenorphine provides at least more effectiveness in withdrawal

management and has fewer adverse effects. Therefore, a replacement of heroin by

buprenorphine in tapered doses followed by the prescription of α2-adrenergic agonist

(e.g. clonidine or lofexidine) to reduce withdrawal symptoms proved to be an effective

strategy for detoxification of opioid addicts (Gowing et al. 2004; Gowing et al. 2004a).

However, it should be noted that patients on high doses of heroin are sometimes

difficult to stabilise with the partial agonist buprenorphine, resulting in precipitated

withdrawal symptoms and early drop out.

α2-adrenergic agonists as detoxification agents

The use of α2 adrenergic agonists (clonidine, lofexidine) to manage the acute phase of

opioid withdrawal is common worldwide.

The α2-adrenergic agonists clonidine and lofexidine have been approved for

detoxification treatment. Clonidine reduces opioid related withdrawal symptoms,

although does not completely relieve symptoms like anxiety, restlessness and insomnia

(Kleber et al. 2006). In comparison to morphine, clonidine is more effective in

suppressing objective withdrawal symptoms, but less effective than morphine in

attenuating subjective withdrawal symptoms (Kleber et al. 2006). Low doses of

methadone were found to be equally effective in suppressing withdrawal symptoms as

clonidine, but patients treated with clonidine were more likely to drop out early

(Gowing et al. 2001; Kleber et al. 2006). No differences were found between clonidine

and low doses of methadone in resolving withdrawal symptoms, but patients treated

with clonidine tend to drop out earlier compared to patients treated with methadone

(Gowing et al. 2001; Kleber et al. 2006). Maybe one reason for the high attrition rate in

the early stage of treatment with clonidine is that patients treated with clonidine develop

withdrawal symptoms early in treatment compared to methadone tapering (Gowing et

al. 2001). Another reason for lower retention rates of withdrawal with clonidine could

be higher rates of adverse effects. Despite more evidence supporting the efficacy of

clonidine, it has now been shown that lofexidine is to be preferred over clonidine,

because hypotension is less likely to occur with lofexidine (Gowing et al. 2004).

The comparison of α2-adrenergic agonists with methadone tapering shows some

differences - the longer duration of methadone tapering, no difference in completion

rates, similar or marginally greater withdrawal severity with α2-adrenergic agonists,

earlier resolution of withdrawal under α2-adrenergic agonists, more adverse events for

clonidine - but no overall difference in clinical efficacy (Gowing et al. 2004).

A systematic review, including ten clinical trials, indicates that the clinical effectiveness

of buprenorphine is superior to clonidine regarding suppression of opioid withdrawal

symptoms, treatment retention, side effects and completion of treatment (Gowing et al.

2004). Recent randomised trials confirmed these findings. Oreskovich et al. (2005)

demonstrated in their randomised, prospective pilot study the superiority of high doses

of buprenorphine to clonidine for acute detoxification from heroin in different

measures, like suppression of withdrawal symptoms (Oreskovich et al., 2005).

Ponizovsky et al. (2006) compared detoxification programs using buprenorphine and

clonidine with regard to side effects and effects on well-being and psychosocial

variables in a randomised controlled trial design (Ponizovsky et al. 2006). Patients, who

received clonidine, developed significantly more side-effects. The authors suggested

that buprenorphine is preferable for inpatient detoxification due to these findings. The

application of buprenorphine in combination with behavioural interventions proved to

be more effective than the combination of clonidine and behavioural interventions with

regard to treatment retention in the detoxification of opioid-dependent adolescents

(Marsch et al. 2005). Patients treated with buprenorphine were also more likely to

provide negative urine samples. On the other hand, Digiusto et al. (2005) found higher

retention rates in patients treated in an inpatient detoxification setting with clonidine

plus other symptomatic medications than in patients in outpatient detoxification using

buprenorphine or clonidine plus other symptomatic medications (Digiusto et al. 2005).

Higher completion rates were found for patients in clonidine-naloxone precipitated

withdrawal treatment under sedation (rapid opioid detoxification), than in clonidineassisted

detoxification (Arnold-Reed & Hulse 2005). However, the reasons for these

findings remain unclear: No differences were found in secondary outcomes, like

severity of withdrawal or craving, and also oral naltrexone compliance levels and

abstinence from heroin four weeks following detoxification were similar (Arnold-Reed

& Hulse 2005).

Sinha et al. (2007) found higher opioid abstinence rates and better relapse outcomes in

patients treated with lofexidine-naltrexone compared to those treated with placebonaltrexone

(Sinha et al. 2007). Furthermore, patients treated with the combination of

lofexidine and naltrexone showed lower opioid craving symptoms in laboratory as

patients in the placebo-naltrexone group. The authors concluded that lofexidine has the

potential to decrease stress-induced and cue-induced opioid craving and improves

opioid abstinence in naltrexone-treated opioid-dependent individuals (Sinha et al. 2007).

The combination of opioid antagonists like naltrexone and α2-adrenergic leads to a

more intense (higher peak) but less overall withdrawal severity than withdrawal

managed with clonidine or lofexidine alone (Gowing et al. 2006). The additional

provision of symptomatic medications enhanced the effectiveness of adrenergic

agonists, and especially the combination with opioid antagonists such as naltrexone and

naloxone leads to less severe withdrawal symptoms in detoxification compared to the

treatment with lofexidine alone (Gowing et al. 2006).

In summary, adrenergic agonists (clonidine and lofexidine) could be considered as an

effective detoxification option especially for patients, who prefer non-opioid treatment

for detoxification. Compared to tapering doses of methadone, opioid withdrawal

management with α2-adrenergic agonists like clonidine and lofexidine leads to equal

rates of completion of withdrawal and overall severity of withdrawal, but to more side

effects and therefore to higher drop-out rates especially at an earlier stage of treatment.

Buprenorphine seems to be superior to clonidine, with regard to the better safety profile,

well-being and self-efficacy. Lofexidine showed fewer side effects with similar clinical

effectiveness in comparison to clonidine. The most described adverse effect of the

opioid withdrawal treatment with clonidine is hypotension, which leads to the

recommendation to check patients` blood pressure regularly. Due to the hypotensive

side effects of clonidine, lofexidine should be preferred in outpatient settings.

Buprenorphine-naloxone combination as a detoxification agent

The combination of buprenorphine and naloxone is available for the maintenance and

detoxification treatment of opioid dependence is available several countries worldwide.

The intention of adding naloxone to buprenorphine is to deter intravenous misuse and

reduce the symptoms of opiate dependence.

Recent RCTs show that a direct and rapid detoxification with buprenorphine-naloxone

is safe and well tolerated by patients with good results in terms of treatment retention,

detoxification completion and abstinence rates in treatment (Amass et al. 2004; Ling et

al. 2005). Amass et al. (2004) treated 234 mostly intravenous heroin-dependent

participants in a thirteen-day buprenorphine-naloxone taper regimen for short-term

opioid detoxification. Most patients received an initial dose of 8 mg buprenorphine-2

mg naloxone and reached a target dose of 16 mg buprenorphine-4 mg naloxone in three

days. Treatment compliance and treatment retention were high: Four of five patients

showed compliance with regard to the medication and two of three patients completed

the detoxification treatment. Only one serious adverse event2 was possibly related to

buprenorphine-naloxone (Amass et al., 2004). Ling et al. (2005) used a multi-centre

randomised trial design to investigate the clinical effectiveness of buprenorphinenaloxone

and clonidine for opioid detoxification in inpatient and outpatient settings. 113

inpatients and 231 outpatients were recruited, and short-term treatment seeking opioiddependent

individuals were randomly allocated in a 2:1 ratio to buprenorphine-naloxone

or clonidine detoxification treatment over a period of 13 days. Appreciably more

participants treated with buprenorphine-naloxone completed the detoxification

treatment and provided also opioid-free urine samples on the last day of clinic

attendance (Ling et al. 2005). With respect to dose related effects of

buprenorphine/naloxone, a recent double-blind randomised controlled trial found that

patients did not additionally benefit from buprenorphine/naloxone doses higher than 8

mg/2 mg with regard to opioid blockade and withdrawal symptom suppression (Correia

et al. 2006). However, Hopper et al. (2005) showed that a single high dose of a 32 mg

buprenorphine/naloxone combination tablet is a feasible method for rapid

detoxification. In this pilot study, twenty patients were randomly allocated to one-day

vs. three-day buprenorphine inpatient detoxification protocols for heroin dependence.

No group differences were found with regard to completion rates, retention in treatment,

intensity of withdrawal symptoms, and provision of opiate-free urine samples (Hopper

et al. 2005). In summary, the combination of buprenorphine and naloxone is effective

and safe for the detoxification of opioid dependents and well tolerated by patients.

Pharmacotherapy for opioid maintenance

Given the chronic, relapsing nature of the disease and the generally disappointing longterm

results of detoxification in combination with relapse prevention, stabilisation of

illicit drug use, improvement of well-being and reduction of drug related harm have

become the most important treatment modality in many countries. Opioid-assisted

maintenance programmes are among the most important strategies in this respect, as

they are associated with reductions of heroin use and HIV risk behaviour (Kerr et al.

2005). Considering the high rate of relapse after detoxification of opioid dependence,

maintenance therapy is currently considered to be the first-line treatment for such

patients (O'Connor 2005). Opioid-assisted maintenance programs have been introduced

in most countries of the world, yet the medication of choice differs from one country to

the next. Methadone is the most extensively studied and most widely used opioid in

maintenance treatment. Other μ-opiate agonists that are used include levoacethylmethadol

(LAAM), codeine, slow-release oral morphine and diacetylmorphine,

as well as the partial μ-opioid agonist buprenorphine.

Methadone as a maintenance agent

Methadone maintenance treatment constitutes an effective treatment modality in

reducing illicit opiate use, although not all patients benefit from methadone substitution,

indicated through further illicit heroin use (Gowing et al. 2001). Nevertheless, several

pre- and post-treatment outcomes confirmed the effectiveness of methadone

maintenance treatment in a wide range of age and ethnic groups of patients and showed

that MMT leads to higher retention rates and longer treatment duration than placebo or

no treatment.

Even lower doses (≤ 20 mg methadone) were found to be more effective in retaining

individuals in treatment than placebo or no treatment (Connock et al. 2007). Methadone

dosages ranging from 60 to 100 mg/day were found to be more effective than lower

dosages in terms of treatment retention and reduction of heroin and cocaine use during

treatment (Connock et al. 2007). Higher doses (60 mg - 110 mg) of methadone are in

general associated with a lower number of opioid-positive urine samples than moderate

and lower doses (< 40 mg) (Connock et al. 2007). Indeed, lower doses of methadone

seem to be sufficient to stabilise the patient and might be helpful to keep the patient in

treatment, but are inadequate to suppress opiate use (Kleber et al. 2006). In comparison,

the treatment retention rates are higher with moderate doses of 40-60 mg/day of

methadone, which are normally necessary to suppress the opioid withdrawal symptoms

(Kleber et al. 2006). Higher methadone doses are needed during maintenance treatment

to block craving for opiates and illicit drug use (Donny et al. 2005), and especially

heroin addicts with axis 1 disorders benefit from high methadone doses (≥ 100 mg/day)

(Kleber et al. 2006). Yet, one effectiveness report from outside of Europe found no

significant difference in the retention rate between patients with moderate (≥ 40-50

mg/day) and high methadone doses (≥ 80-100 mg/day), maybe due to a plateau of dose

related efficacy of methadone, but marked declines in self-reported illicit drug use in

both groups (Kleber et al. 2006). As the illicit drug use significantly declines in patients

with higher methadone doses, the explanation of a plateau of dose related efficacy of

methadone is only valid for the retention rates (Kleber et al., 2006). However, adequate

daily dosing has an important effect on retention in methadone maintenance treatment

(Anderson & Warren 2004). In the US, low dosages of methadone have to a large extent

been replaced by higher dosages: In 1988, almost 80% of the patients received dosages

of less than 60 mg/day, in 2000, this was the case in 36% of the cases (D'Aunno &

Pollack 2002). Suboptimum methadone doses lead to a lower retention rate, and when

patients remain in treatment, MMT reduces heroin use, delinquency, and HIV-related

risk behaviour and HIV transmission (Ward et al. 1999). Nonetheless, since very high

dosages of methadone have also been associated with the occurrence of Torsade de

Pointes (TdP), high dosages need to be monitored carefully (Krantz et al. 2002).

However, sporadic cases of TdP have also been reported in patients receiving a

recommended dose between 60 and 100 mg methadone per day (Pearson & Woosley

2005) and the risk of death caused by overdoses in heroin users seems to substantially

reduce after stabilisation on methadone (Gowing et al. 2001).

MMT seems to be superior to methadone detoxification treatment or outpatient drugfree

treatment in reducing heroin use, criminal behaviour and risky sexual behaviour

and is associated with greater retention in treatment than therapeutic communities,

outpatient drug-free treatment or naltrexone treatment (Gowing et al. 2001).

Observational studies suggested that the treatment retention is better in a take-home

approach with corresponding doses of methadone and reduced frequent treatment centre

visits (Gowing et al. 2001).

Opioid dependence is commonly associated with psychiatric co-morbidities like

depression and, therefore, associated with poor outcomes. Dean et al. (2004) used a

double-blind, double dummy, randomised controlled trial design to examine whether

heroin users maintained on buprenorphine demonstrate greater improvement in

depressive symptoms than those on MMT (Dean et al. 2004). Contrary to former

findings, which reported depression as a side effect of buprenorphine or described

greater depressive symptom improvement with methadone, no differential benefits of

buprenorphine compared to methadone were found on depressive symptoms in heroin

users engaged in maintenance treatment (Dean et al., 2004). However, a conclusion

based on these results could not be made and requires further investigations. Flexible

doses of methadone were found to be more effective than flexible doses of

buprenorphine for maintenance treatment, maybe because of the higher potential of

methadone to suppress heroin use, especially if high-doses of methadone are used

(Connock et al. 2007; Mattick et al. 2007). Compared to buprenorphine maintenance

treatment, the administration of an average maximum dose of 80 mg methadone leads to

higher treatment durations, longer periods of sustained abstinence and a greater

proportion of cocaine- and opioid-free urine samples than liquid buprenorphine in an

average maximum dose of 15 mg (Schottenfeld et al. 2005). Furthermore, MMT is

associated with a reduction of self-reported adverse effects, a reduction of the relative

mortality risk, an improvement of HIV-related behaviour and a reduction of

delinquency (Gowing et al. 2001; Johnson et al. 2003).

In summary, methadone is the best-studied and most effective opioid agonist for

maintenance treatment so far. Treatment outcome in methadone maintenance has been

shown to improve substantially with increased dosages of methadone. Adequate dosing

is an important issue and avoids on the one hand unpleasant withdrawal symptoms,

especially in the latter half of each inter-dosing interval, and on the other hand

significant adverse effects. The combination with psychosocial treatment such as

counselling and behavioural interventions leads to a broader effectiveness and a greater

range of treatment outcomes such as reduced craving, reduction of illicit drug use and

drug-related delinquency, improvement of health and well-being and reduction of drug

related harm. However, even methadone maintenance treatment without adequate

psychosocial care as an interim solution until entry into a comprehensive methadone

maintenance treatment programme has shown to increase the likelihood of entry into

comprehensive treatment and reduce heroin use and delinquency (Schwartz et al. 2006;

Teesson et al. 2006).

Buprenorphine as a maintenance agent

Buprenorphine proved to be effective and clinically useful in the maintenance treatment

of opioid dependence. Compared to placebo, buprenorphine was found to be an

effective agent for the treatment of opioid dependence in a maintenance approach and

several studies have shown efficacy of buprenorphine in maintenance treatment of

opioid dependence (Ling & Wesson 1984; Mattick et al. 2007). Like methadone, the

efficacy of buprenorphine is dose-related: Higher doses of buprenorphine showed better

outcomes than lower doses, although these differences were not always robust in their

values (Kleber et al. 2006). Low and moderate doses (2 - 8 mg) of buprenorphine are

superior to placebo in the measures of treatment retention, provision of opioid-negative

urine samples, mortality, and psychological and social functioning (Kleber et al. 2006).

When using equipotent doses, the efficacy of buprenorphine in the maintenance

treatment of opioid dependents is comparable to that of methadone (Kleber et al., 2006).

Therefore no significant differences were found between low dose buprenorphine and

low dose methadone with regard to treatment retention, opiate free urine samples and

self-reported heroin use (Mattick et al., 2007), whereas moderate doses of

buprenorphine are superior to low doses of methadone (Kleber et al. 2006). In general

contrary to these dose-related results, Connock et al. found that methadone in

comparable and especially in flexible doses is superior to buprenorphine with regard to

treatment retention, with the exception of lower doses (Connock et al. 2007).

The maximum therapeutic effect of sublingual buprenorphine tablets occurs in the range

of moderate (8 mg) to higher doses (16 mg), comparable to moderate methadone doses

of 40-60 mg (Kleber et al. 2006). In flexible dosage, methadone is significantly more

effective than buprenorphine in retaining patients in treatment, perhaps because of the

higher potential of methadone to suppress heroin use, especially if high doses of

methadone are used (Mattick et al. 2007).

Methadone seems to be superior to buprenorphine in the maintenance treatment of

opioid dependents with co-occurring cocaine dependence (Schottenfeld et al. 2005). The

administration of an average maximum dose of 80 mg methadone leads to higher

treatment durations, longer periods of sustained abstinence and a greater proportion of

cocaine- and opioid-free urine samples than liquid buprenorphine in an average

maximum dose of 15 mg (Schottenfeld et al. 2005). However, Montoya et al. (2004)

showed in their double-blind, controlled clinical trial with strict eligibility criteria that

daily doses of 8 and 16 mg of buprenorphine solution in combination with drug abuse

counselling are feasible and effective in maintenance treatment of outpatients with cooccurring

opioid and cocaine dependence (Montoya et al. 2004).

The longer duration of therapeutic action of buprenorphine provides the advantage of a

less than daily schedule, however, the comparison of daily vs. intermittent

administration lead to different results. Some findings showed no increase of

buprenorphine doses under intermittent administration, while others found a doubling of

doses (Kleber et al. 2006). However, another trial found that intermittent doses for 48-

hours provide adequate effects and are preferable to daily dosing (Kleber et al. 2006).

From a clinical point of view, dosing of buprenorphine on every fourth day is possible

and was found to lead to similar effects on the measures of adverse effects and efficacy

than daily doses (Kleber et al. 2006). A recent controlled trial confirmed these results

(Marsch et al. 2005). In this comparison no differences were found between one per

day, three times a week and twice a week administration of buprenorphine regarding

treatment retention and opiate use (Marsch et al. 2005). However, the less-than-daily

schedule with adapted doses was found to be effective, is often preferred by the patient

and provides the opportunity to serve a greater number of opioid-dependent patients.

The efficacy of buprenorphine maintenance treatment was found to be comparable to

methadone maintenance with advantages in some treatment settings, in alternate day

dosing, better safety profile, and milder withdrawal syndrome (Mattick et al. 2007). In

two small-scale studies, buprenorphine prescription in primary care was associated with

good retention (70-80%) and reasonable rates of opiate free urines (43-64% achieving

three or more consecutive weeks of opiate free urines) (Fiellin et al. 2002; O'Connor et

al. 1996). These positive effects were confirmed in a larger trial, showing a reduction of

opiate use and craving under buprenorphine (Fudala et al. 2003). Similar results were

obtained in France some years ago (Duburcq et al. 2000). Buprenorphine reduced the

risk of overdose related death compared to methadone (Kleber et al. 2006; Simoens et

al. 2000) and was found to reduce mortality in maintenance treatment (Auriacombe et

al. 2001). However, recently, Lofwall et al. (2005) examined the safety and side effect

profiles in 164 opioid dependents in buprenorphine and methadone outpatient treatment.

After randomisation to buprenorphine (n = 84) or to methadone (n = 80) all patients

were maintained for 16 weeks. Besides very few clinical gender differences, common

profiles of safety and side effects were found for both groups (Lofwall et al. 2005).

Connock et al. (2007) found in their recent health technology assessment no

generalisable results in the comparison of methadone and buprenorphine with regard to

mortality (Connock et al. 2007). In general, buprenorphine is associated with lower

levels of withdrawal symptoms than heroin or methadone (Gowing et al. 2001).

In general, maintenance treatment with buprenorphine provides some advantages for the

treatment of opioid dependence in comparison to methadone, e.g. a better safety profile

at high doses, a lower abuse potential, the possibility of a less-than-daily administration

and lower impairment in psychomotor and cognitive functioning. Similar to methadone,

the efficacy of buprenorphine in maintenance treatment is dose related; higher doses of

buprenorphine (12 mg/day or more) improve the treatment retention and reduce illicit

heroin use. Provided in effective doses, buprenorphine appears to be at least as effective

as methadone with regard to reduction of illicit opioid use and treatment retention,

whereas methadone maintenance in high doses is associated with higher rates of

retention in treatment and better suppression of withdrawal symptoms than

buprenorphine maintenance treatment (Mattick et al. 2007). The recent Cochrane review

recommends that buprenorphine maintenance should be supported as a maintenance

treatment, when higher doses of methadone cannot be administrated (Mattick et al.

2007). However, Marsch et al. (2005) demonstrated that predictors of treatment success

of LAAM, buprenorphine, and methadone appear to be largely comparable, and they

did not detect any factors that would prefer one medication over the others (Marsch et

al. 2005).

Buprenorphine-naloxone combination as a maintenance agent

The buprenorphine-naloxone combination contains the partial opiate agonist and

antagonist buprenorphine as well as the opioid antagonist naloxone to deter illicit

intravenous preparation of the tablet. This is intended to attenuate the effects of

buprenorphine on opioid-naive users should this formulation be injected.

Fudala et al. (2003) used a randomised blinded placebo-controlled trial design including

4-week follow-up to demonstrate that sublingual tablet formulation of buprenorphine

and naloxone is effective for the treatment of opiate dependence compared to placebo

(Fudala et al. 2003). Recently, Mintzer et al. (2007) showed the feasibility and efficacy

of buprenorphine-naloxone treatment in primary care settings (Mintzer et al. 2007).

An Australian pilot study showed the tolerability and feasibility of unsupervised

administration of buprenorphine-naloxone combination tablets in the maintenance

treatment of opioid dependence (Bell et al. 2004). Another double-blind crossover study

found only minor impairment with buprenorphine-naloxone administration in the

highest dose of 32 mg/8 mg (Mintzer et al. 2004). However, both recent studies

included only a small number of patients and further investigations are needed with

larger sample sizes in a control group design to confirm these findings. Both for

methadone or buprenorphine maintenance alone, new research focuses on the

improvement of adherence through additional psychosocial treatment. Fiellin et al.

(2006) conducted a 24-week randomised, controlled clinical trial with 166 patients to

investigate the effect of adding two different kinds of counselling to buprenorphinenaloxone

maintenance therapy for opioid dependence (Fiellin et al. 2006). The

participants were randomly allocated to a brief, manual-guided, medically focused

counselling and either once-weekly or thrice-weekly medication or enhanced medical

management with extended sessions and thrice-weekly medication dispensing. The

patients in all three treatment types showed significant reductions of illicit opioid use,

although no differences were found regarding opioid-negative urine samples, the

duration of abstinence from illicit opioids and the retention in treatment. The efficacy of

buprenorphine in combination with naloxone seems to be comparable to buprenorphine

alone in the maintenance treatment of opiate dependency. Patients treated with

buprenorphine and naloxone showed lower rates of opiate-positive urine samples,

showed fewer craving symptoms for opiates, and greater improvement in overall health

and well-being than patients who received placebo.

Slow-release oral morphine as maintenance agent

Slow release oral morphine (SROM) acts as an agonist on the μ-receptor and the long

duration of action permits to administer a once-a-day preparation. SROM has been

authorized for maintenance treatment of opioid dependence mainly in a few European

countries. Only little evidence was found from outside of Europe. Jones et al. (2005)

showed in their recent randomised trial the feasibility and safety of switching opioiddependent

pregnant women from short-acting morphine to buprenorphine or methadone

during the second trimester3 of pregnancy (Jones et al. 2005). Further studies will have

to confirm these results in order to be able to evaluate the added value of this substance

for the treatment of heroin dependence. In summary, SROM might be a promising

compound for maintenance treatment. Further details are provided in the respective

European chapter.

Pharmacotherapy for relapse prevention

Naltrexone for relapse prevention

The opiate antagonist naltrexone is indicated for prescription for those who have

achieved abstinence. In a human laboratory setting, naltrexone showed to be effective to

block the effects of short acting opioids such as heroin (Kleber et al. 2006). Low doses

of naltrexone had no discernible advantage, and participants preferred 50 mg per day.

Despite the preference of patients for blocking doses of oral naltrexone (like 50 mg per

day), the effectiveness of naltrexone appeared not to be dose related (Rea et al. 2004).

Due to the prevention of the euphoria effect of opiates, outpatient double-blind placebo

controlled trials with long-acting opiate antagonist are very uncommon. Placebocontrolled

trials showed extremely high dropout rates, which implicates that the general

acceptability of the participants is low (Kleber et al. 2006). On the other hand, the high

drop out rates lead to highly selective patient samples in most of the naltrexone

maintenance studies and it could not be precluded that these groups of patients have a

high level of motivation (Kleber et al. 2006). Indeed, the retention in treatment was

found to be the most important predictor for the effect of naltrexone in treating opioid

dependence, and authors therefore propose to add counselling to naltrexone

maintenance treatment (Ritter 2002). O’Brien et al. (2005) suggested in their metaanalytic

review that medications for relapse prevention are most effective in the context

of counselling, therapeutic and behavioural techniques (O'Brien 2005). However, Nunes

et al. (2006) concluded in their recent randomised control trial that there may be a limit

on the extent to which behavioural therapy can overcome poor adherence to oral

naltrexone (Nunes et al. 2006): The authors investigated the effectiveness of

Behavioural Naltrexone Therapy (BNT) including voucher incentives, motivational and

cognitive behavioural therapies. Sixty-nine patients were randomly administrated to the

admission of BNT or to a standard treatment control including compliance

enhancement. In both groups, treatment retention after six months was low (22% BNT

vs. 9%), whereas most patients remaining in treatment after three months achieved

abstinence from opioids (Nunes et al. 2006). Tucker et al. (2004) found no reasonable

effects, although the provision of an additional 12-week manualised group-counselling

programme including a cognitive-behavioural relapse prevention approach provides

additional benefit to naltrexone treatment (Tucker et al. 2004).

An alternative strategy to improve the retention rates is the administration of sustainedrelease

depot formulation of naltrexone instead of oral naltrexone in treating opioid

dependence. A recent randomised controlled trial found promising results (Comer et al.

2006): Sixty heroin-dependent males and females were randomly allocated to placebo

or 192 or 384 mg of depot naltrexone, including twice weekly relapse prevention

therapy for all participants. The sustained-release depot formulation of naltrexone was

well tolerated. After two months, 60-68% of patients in the 192 mg of naltrexone and

384 mg of naltrexone groups, respectively, remained in treatment compared to 39% of

the placebo group. The mean dropout time was dose related, varying between 27 days

for the placebo group and 48 days for the 384 mg of naltrexone group. However, the

study sample was small and no direct comparison with oral naltrexone was provided, so

that the potential advantages should be regarded as promising but not proven. The

former assumption that the combination of naltrexone with a Selective Serotonin Reuptake

Inhibitor (SSRI)4 is more effective than naltrexone alone, could not be

confirmed in recent randomised, placebo-controlled trials (Farren & O'Malley 2002). A

recent primarily double-blind, placebo controlled RCT with a small number of patients

suggests that the additional administration of lofexidine to oral naltrexone leads to

higher opioid abstinence rates and improved relapse outcomes as compared to the

combination of placebo and naltrexone (Sinha et al. 2007). However, these promising

results have to be proven in larger sample sizes.

Naltrexone is considered to be a safe medication with few side effects; only high doses

can lead to transaminase elevations in liver function tests (Kleber et al. 2006). Two

other issues related to the prescription of naltrexone deserve special attention: the

potential induction of depression by naltrexone, and the overdose risk following

discontinuation of a naltrexone treatment. A systematic review of the available literature

found no evidence for a relationship between naltrexone and depression or anhedonia,

but found that reduced opiate tolerance following naltrexone treatment may indeed

increase the risk of heroin overdose (Dean et al. 2006; Ritter 2002). Therefore, a clear

warning to patients treated with oral naltrexone regarding the risk of heroin overdose is

warranted. One possibility to avoid this risk is the administration of long acting

sustained release naltrexone implants. Hulse et al. (2005) showed a reduced number of

opioid overdoses observed in the 6-12 months post-implant treatment (Hulse et al.

2005). However, a most recent case report indicates that patients can die from an opioid

overdose with a naltrexone implant and blood naltrexone levels higher than reported

blockade levels (Gibson et al. 2007).

In summary, the effectiveness of antagonist maintenance with oral naltrexone for opioid

dependence has been limited by high dropout rates. This conclusion is corroborated by

the findings of the National Evaluation of Pharmacotherapies for Opioid Dependence

(NEPOD) in Australia, which showed that only 4% of the patients in naltrexone

maintenance treatment were still in treatment after six months (NDARC 2001).

Furthermore, patients preferred relapse prevention treatment with buprenorphine or

methadone (Digiusto et al. 2005). Naltrexone maintenance seems not to be effective as a

stand-alone treatment and should be, therefore, part of a broader treatment programme

or should be reserved only for highly motivated patients living in a stable life situation.

Nevertheless, a promising strategy to improve treatment retention in broader range

could be the combination of long-acting implantable naltrexone formulations and

behavioural methods.

5.2 Pharmacotherapy for the treatment of stimulant-related disorders

In summary, non of the proofed medication has been found yet that can be considered a

standard for treating stimulant dependence effectively, although a number of different

medications has been tried (Kleber et al. 2006). The treatment of cocaine dependence

frequently still includes the use of antidepressants, especially SSRIs, despite the low

evidence level for their efficacy. Some typical and atypical psychotic agents such as

haloperidol, olanzepine and risperidone, were found to be effective in the treatment of

patients with co-occurring schizophrenia and cocaine dependence. Also promising

results are expected from topiramate and other antiepileptic drugs, and much hope is

being placed in the development of the cocaine vaccine.

Detoxification treatment for stimulant-related disorders

Symptoms of intoxication are treated in different ways. Labetalol, an alpha-1 and beta

adrenergic blocker used to treat high blood pressure, has been used for treating

symptoms of cocaine intoxication, but the little clinical research shows that the use of

adrenergic blockers and dopaminergic antagonists should be used carefully in acute

cocaine intoxication (Kleber et al. 2006). Benzodiazepines (such as Oxazepam,

Alprazolam) are given those cocaine users with acute intoxication who are very agitated

(Kleber et al. 2006).

One way of treating withdrawal symptoms during detoxification, such as sleep

difficulties, symptoms of depression, anxiety, anhedonia is to give dopamine agonists

(e.g. amantadine), but research findings have been ambiguous, with two studies finding

positive effects and two others with no significant effect (Kleber et al. 2006). The same

is true for bromocriptine that acts as a dopamine agonist. Bromocriptine has potential

use in treating cocaine addiction, since the addictive effects of cocaine are caused by it

blocking dopamine reuptake. First studies seemed to be promising, until a double-blind

RCT found a higher rate of negative urine-samples but higher dropout rate with

bromocriptine than amantadine, an antiviral drug, releasing dopamine from the nerve

endings of the brain cells (Kleber et al. 2006). Another double-blind RCT found no

significant differences between bromocriptine and placebo concerning reduction of

cocaine use (Kleber et al. 2006). One uncontrolled inpatient study found no reduction of

craving with bromocriptine (Kleber et al. 2006). Therefore, the UNODC report

(UNODC 2002) comes to the conclusion that there is no significant effect of both

bromocriptine and amantadine. For patients with relatively severe withdrawal

symptoms, propranolol has showed some effect (Kleber et al. 2006).

Antipsychotic medication has been prescribed and reported to be somewhat effective in

treating cocaine-related delusions, but most patients recover from delusions without

medication after a few hours (Kleber et al. 2006. No evidence has been found that

anticonvulsants reduce cocaine-induced seizures (Kleber et al. 2006). Gillman et al.

(2006) found reduced cocaine withdrawal symptoms in cocaine dependents treated with

psychotropic analgesic nitrous oxide (PAN), a titrated mixture of oxygen and nitrous

oxide (Gillman et al. 2006).

A recent placebo-controlled pilot study investigated the safety and efficacy of

mirtazapine, an antidepressant used for the treatment of moderate to severe depression,

in amphetamine detoxification (Kongsakon et al. 2005). Twenty amphetamine

dependents were randomly allocated to either mirtazapine treatment (9 patients) or

placebo (11 patients), of which seven patients in the mirtazapine and nine in the placebo

group completed the study. Patients in the mirtazapine group showed significant

improvements in the total Amphetamine Withdrawal Questionnaire (AWQ)5 score

versus placebo at days 3 and day 14. Despite reported mild adverse events like headache

etc. and the small sample size the authors suggested, that mirtazapine may be an option

for amphetamine detoxification treatment (Kongsakon et al. 2005).

Substitution treatment for stimulant-related disorders

Different approaches have been considered for replacement therapy in the treatment of

cocaine dependence. Replacement therapies with methylphenidate or sustained-released

amphetamine showed better patient retention and greater reduction in cocaine use

compared to placebo, but further studies are needed (Kleber et al. 2006). Buprenorphine

has been tried with those patients with double dependence (opiate and cocaine) and

showed some effect on cocaine use in open trials but not in double-blind studies (Kleber

et al. 2006). Montoya et al. (2004) showed reducing concomitant opiate and cocaine use

under the provision of 16 mg daily doses of sublingual buprenorphine solution

(Montoya et al. 2004). Schottenfeld et al. (2005) found significantly longer treatment

retention rates, longer periods of sustained abstinence and a greater proportion drug-free

tests in co-occurring cocaine and opioid dependents maintained with methadone than

patients assigned to receive buprenorphine (Schottenfeld et al. 2005).

Stoops et al. (2007) recently indicated that acute d-amphetamine pre-treatment does not

increase stimulant self-administration (Stoops et al. 2007). Grabowski et al. (2004)

conducted two studies to investigate efficacy of sustained release d-amphetamine as

well as risperidone (an atypical antipsychotic medication for cocaine dependence), each

in combination with methadone in 240 (120/study) cocaine and heroin co-dependents,

which randomly allocated to one trial medication or placebo (Grabowski et al. 2004).

All patients underwent a methadone induction, were stabilised at 1.1mg/kg and received

one behavioural therapy session per week. The combination of the methadone and damphetamine

was found to be significantly more effective than methadone and placebo,

and also better than methadone and risperdione for treatment of concurrent cocaine and

opioid dependents (Grabowski et al. 2004).

Methylphenidate (MPH), a prescription stimulant commonly used to treat attentiondeficit

hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), was recently found to be effective for reducing

intravenous drug use in patients with severe amphetamine dependence respectively

cocaine use in patients with cocaine dependence (Levin et al. 2007; Tiihonen et al.

2007). Furthermore, methylphenidate can be safely provided in an outpatient setting

with active cocaine users (Winhusen et al. 2006).

Recently, Collins et al. (2006) found that the provision of up to 20mg memantine, a

non-competitive N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) antagonist, did not alter the subjective

or reinforcing effects of cocaine in methadone-maintained cocaine smokers (Collins et

al. 2006). Also, the maintenance treatment with gabapentin, a medication originally

developed for the treatment of epilepsy, did not alter the choice to self-administer

cocaine by treatment-seeking cocaine-dependent individuals and was found not to be

clinically useful for the treatment of cocaine and methamphetamine dependence (Haney

et al. 2005; Hart et al. 2007; Hart et al. 2007a; Hart et al. 2004; Heinzerling et al. 2006).

Also, baclofen, a GABA-ergic compound, was found to be ineffective at suppressing

self-administration, especially in more intensive cocaine users and seems to have only a

small therapeutic effect for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence compared to

placebo (Heinzerling et al. 2006).

Abstinence maintenance for stimulant-related disorders

No medication has shown clear efficacy in treating cocaine dependence (Kleber et al.

2006), and no antagonists have been found yet to be effective (UNODC 2002).

However, patients with severe forms of dependence and severe withdrawal symptoms

or those not responding to psychosocial treatment may find medication to be useful for

them (Kleber et al. 2006).

Shoptaw et al. (2006) indicated that the antidepressant sertraline is contraindicated for

the treatment methamphetamine dependence due to significant more adverse events

compared to placebo conditions (Shoptaw et al. 2006). Newton et al. (2006) suggested

that the antidepressant bupropion has some effectiveness in reducing

methamphetamine-induced subjective effects and cue-induced craving (Newton et al.

2006). Newton et al. (2006) found reduced acute methamphetamine-induced subjective

effects and reduced cue-induced craving under the administration of bupropion, an

atypical antidepressant that acts as a norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitor,

and nicotinic antagonist (Newton et al. 2006). Furthermore buprion was found to be

well-tolerated by patients and seems to alleviate the cardiovascular effects of

experimentally administered methamphetamine (Newton et al. 2005).

The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor fluoxetine and the dopamine reuptake

inhibitor bupropion had some benefit in small studies but not in larger trials (Kleber et

al. 2006). The tricyclic antidepressant desipramine has been studied with inconsistence

findings, some studies showing positive effects others not. One study compared

desipramine with placebo and found a short term effect of 6 weeks but not at 12 weeks

or longer (Kleber et al. 2006). Several recent clinical trials confirmed, that the use of

antidepressants such as paroxetine, reboxetine, nefazodone, sertaline, and venlafaxine

do not support the treatment of cocaine dependence (Ciraulo et al. 2005; Ciraulo et al.

2005a; Passos et al. 2005; Winhusen et al. 2005). Desipramine, a tricyclic

antidepressant (TCA) that inhibits the reuptake of norepinephrine, is associated with

depression improvements and therefore with improvements in cocaine use in treatment

of cocaine-dependents with depression in an outpatient setting (McDowell et al. 2005).

However, the administration with desipramine lead to higher dropout rates due to side

effects and medical adverse events (McDowell et al. 2005).

After some initial promising results, the anticonvulsant carbamazepine had no effects in

later double-blind placebo-controlled studies (Kleber et al. 2006). In recent clinical

trials the anticonvulsants valproate, lamotrigine, and gabapentin were found to be not

more effective than placebo in treating cocaine dependence (Berger et al. 2005; Bisaga

et al. 2006; Gonzalez et al. 2007; Reid et al. 2005). For the utility of divalproex (an

anticonvulsant and mood-stabilising drug) in patients with bipolar disorder and primary

cocaine dependence further high quality experimental, placebo-controlled studies are

warranted to confirm the promising results of a first pilot study (Salloum et al. 2007).

Tiagabine, an anti-convulsive medication, has been shown to lead to reduced positive

urine samples in patients treated for cocaine dependence compared to placebo and may

merit further study, although the patients of a recent trial showed difficulties in

tolerating low dose of tiagabine (Gonzalez et al. 2007; Winhusen et al. 2005).

Topiramate, an anticonvulsant drug, showed recently some promising results in one

double-blind study (Kleber et al. 2006) and Kampman et al. (2004) demonstrated that

topiramate-treated patients were more likely to be abstinent from cocaine compared to

placebo-treated (Kampman et al. 2004).

The GABA agonist baclofen has shown some minor effect (Heinzerling et al. 2006),

and one double-blind clinical trial with tiagabine showed more effect than placebo in

reducing cocaine use (Kleber et al. 2006). The narcoleptic medication modafinil has

shown some effects, but needs further studies (Kleber et al. 2006). Modafinil blocked

the euphoric effects of cocaine, significantly decreased systemic exposure to cocaine

during the first 180 minutes following intravenous cocaine administration and improves

clinical outcome when combined with psychosocial treatment for cocaine dependence

(Dackis et al. 2005; Donovan et al. 2005; Ginsberg 2005). Malcolm et al. (2006) found

in their recent clinical trial6 no significant hemodynamical interactions between

modafinil and cocaine, but further outpatient trials appeared to be warranted (Malcolm

et al. 2006). The systematic review by the APA describes mixed results on dopamine

agonists: amantadine, an antiviral drug, has been best studied but with no overall

benefit, only in some studies (Kleber et al. 2006). Kampman et al. (2006) used a doubleblind,

placebo-controlled design to evaluated the efficacy of amantadine, propranolol, a

non-selective beta blocker mainly used in the treatment of hypertension, and their

combination in one hundred and ninety-nine cocaine dependent patients with severe

cocaine withdrawal symptoms (Kampman et al. 2006). Neither propranolol nor

amantadine or their combination was found to be significantly more effective than

placebo in promoting abstinence from cocaine in these extremely difficult-to-treat

patients, whereas highly adherent patients to study medication showed better treatment

retention and higher rates of cocaine abstinence under the provision of propranolol

compared to placebo (Kampman et al. 2006).

Reid et al. (2005) found no effectiveness of the atypical antipsychotic agent olanzapine

for the treatment of cocaine dependence with regard to cocaine use, as measured by

urine Benzoylecgonine (BE)7 levels and self-report (Reid et al. 2005) and risperidone,

another atypical antipsychotic medication, were found to be insufficient in reducing

cocaine craving in cocaine dependents (Smellson et al. 2004). The partial dopamine

agonist aripiprazole have shown promising results in a small clinical trial regarding

subject-related and cardiovascular effects, but further research is needed to confirm the

effectiveness (Lile et al. 2005). However, typical and atypical psychotic agents such as

haloperidol, olanzepine and risperidone, were found to be effective in the treatment of

patients with co-occurring schizophrenia and cocaine dependence (Albanese & Suh

2006; Rubio et al. 2006; Sayers et al. 2005; Smelson et al. 2006). Stoops (2006)

indicated that the aripiprazole, an atypical antipsychotic medication approved for the

treatment of schizophrenia and acute manic and mixed episodes associated with bipolar

disorders, may have clinical utility in treating stimulant dependence, but large-scale

clinical trials are needed to confirm the efficacy (Stoops 2006). Otherwise, mazindol, a

catecholamine reuptake inhibitor and antipsychotic agent, was fount to be ineffective in

reducing cocaine consumption, cocaine craving, and psychiatric symptoms in patients

diagnosed with comorbid schizophrenia and cocaine abuse or dependence (Perry et al.

2004).

Dopamine agonists like selegiline, l-dopa/carbidopa, pergolide had inconclusive or

negative findings and altogether no superiority to placebo (Kleber et al. 2006) and also

recent findings did not confirm the support for the efficacy of dompamine agonists for

the treatment of cocaine dependence (Ciraulo et al. 2005; Focchi et al. 2005; Gorelick &

Wilkins 2006). However, Shoptaw et al. (2005) found good results for cabergoline, a

potent dopamine receptor agonist, regarding improvements in addiction severity and

negative urine samples for cocaine metabolites and provided empirical support for

conducting a larger study of the medication (Shoptaw et al. 2005).

The opiate antagonist naltrexone has not been found useful for treatment of cocaine

dependence (Kleber et al. 2006; Schmitz et al. 2004). Schmitz et al. (2004) found, that

50 mg/day of naltrexone failed to reduce either cocaine or alcohol use in co-occurring

cocaine and alcohol abusers, whereas psychotherapy significantly reduced cocaine use

during the first 4 weeks of treatment (Schmitz et al. 2004). Baker et al. (2007) found

that the administration of disulfiram reduced cocaine-associated subjective effects

(‘high’ and ‘rush’) (Baker et al. 2007). Carroll et al. (2004) showed that the provision of

disulfiram alone and in combination with cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) is

effective in reducing cocaine use in cocaine-dependent outpatients (Carroll et al. 2004).

Several further medications were recently investigated with regard to their efficacy for

treatment of cocaine dependence. Progesterone, a steroid hormone, attenuated some of

the physiological and subjective effects of cocaine, but further studies are warranted to

assess the efficacy (Sofuoglu et al. 2004). High doses of dehydroepiandrosterone, a

natural steroid prohormone, seems to be contraindicated as a pharmacotherapy for

cocaine dependence due to increasing cocaine use compared with placebo (Shoptaw et

al. 2004). Tryptophan, an essential amino acid, did not significantly prevent relapse to

cocaine use or attenuate cocaine use after relapse (Jones et al. 2004). Levodopa (Ldopa),

an intermediate in dopamine biosynthesis, and amlodipine, a calcium channel

blocker, were found to be not superior to placebo in reducing cocaine use (Malcom et

al. 2005; Mooney et al. 2007). Also selegiline, a drug used for the treatment of

Parkinson's disease, does not support the treatment of cocaine dependence (Elkashef et

al. 2006), as well as celecoxib, a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (Reid et al.

2005).

Immunisation and vaccination are two strategies with a long tradition and very little

empirical proof of effectiveness (Kantak 2003). In (passive) immunisation, catalytic

antibodies are injected that bind cocaine and subsequently hydrolyse cocaine into the

inactive products ecognine methyl ester and benzoic acid. A cocaine vaccine has also

been proposed; this would attempt to block the effects of cocaine using cocaine

antibodies (Bagasra et al. 1992). This unique approach to the pharmacotherapy of

cocaine addiction was initiated by immunisation experiments that demonstrated specific

cocaine antibody production in animals (Carrera et al. 1995; Carrera et al. 2000; Fox

1997; Fox et al. 1996). Cocaine-specific antibodies can sequester cocaine molecules in

the bloodstream, thereby allowing naturally occurring enzymes (cholinesterases) to

convert cocaine into inactive metabolites, which are then excreted. As the antibodies

cannot cross the blood-brain barrier, the vaccine is not expected to have any direct

psychoactive effect. As the antibodies prevent cocaine from having an effect, the

reinforcing effect of continued cocaine use would be dampened. Furthermore, the

vaccine persists for months, so there is no need for daily administration of medication.

A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial involving 34 former

cocaine users was carried out to assess the safety and immunogenicity of the therapeutic

cocaine vaccine TA-CD (Kosten & Biegel 2002). The results of this trial showed that

the vaccine induced cocaine antibodies in a time- and dose-dependent manner and that it

was well tolerated with no serious adverse events during 12 months of follow-up. This

trial was then followed up by an open-label, 14-week, dose escalation study evaluating

the safety, immunogenicity and clinical efficacy of the cocaine vaccine (Martell et al.

2005). Ten cocaine-dependent subjects received a total dose of 400 μg of vaccine in

four injections over the course of 8 weeks and eight cocaine-dependent subjects

received a total dose of 2 000 μg of vaccine in five injections over the course of 12

weeks. The results showed a high completion rate, no serious adverse events, good

tolerance and a significantly higher likelihood of cocaine-free urine in the high-dose

group at 6 months. The results are most encouraging when compared with other

pharmacological strategies, but will have to be replicated in further studies.

Pharmacotherapy for the treatment of cannabis related disorders

Neurobiological trials on cannabis withdrawal demonstrate the importance of the

development of further pharmacological options for the treatment of cannabis

dependence. Different published studies have employed laboratory animals to evaluate

medication effects on cannabinoid withdrawal symptoms. Nevertheless clinical trials of

human participants are rare and none of the included effectiveness reports found clinical

trials supporting a medication for the pharmacotherapy of cannabis dependence (Kleber

2003; UNODC 2002). Some findings suggest that oral delta-9-tretrahydrocannabinol

(THC) might be helpful in suppressing cannabis withdrawal (Budney et al. 2007). In a

recent clinical trial eight daily cannabis-using adults were randomly allocated to placebo

or lower dose of THC (30 mg) or higher doses of THC (90 mg) during three 5-days

periods of abstinence from cannabis. A lower daily dose of THC reduced withdrawal

discomfort, where as higher daily doses showed a greater effect in suppressing

withdrawal symptoms (Budney et al. 2007). These results replicated the findings of

another clinical trial that demonstrated that THC administration beginning on the first

day of marijuana abstinence lead to decreased symptoms of cannabis withdrawal, like

anxiety, misery, chills or self-reported sleep disturbance, relative to placebo (Haney et

al. 2004). Oral THC also decreased marijuana craving during abstinence compared to

placebo. The same study investigate the effect of the mood stabiliser divalproex to

attenuate a broader range of cannabis withdrawal symptoms, compared to

antidepressants, such as nefazodone and burpropion (Haney et al. 2004). As like

bupropion, maintenance with divalproex prior to and during marijuana abstinence also

markedly worsened mood such as irritability, edginess, anxiety and sleepiness (Haney et

al. 2004). Another double-blind placebo-controlled study focused on the effectiveness

of the anticonvulsant drug gabapentin in suppressing cannabis use and cannabis

withdrawal symptoms (Escher et al. 2005). In several studies gabapentin was found to

be effective and safe in treatment of depression, anxiety, insomnia, aggression, and

alcohol withdrawal. Twenty-one non treatment-seeking volunteers with concurrent

DSM IV8 cannabis and alcohol abuse or dependence were randomly treated with

gabapentin (1200 mg/d) or placebo. Gabapentin administration decreased a subset of

marijuana withdrawal symptoms compared to placebo as measured by the Marijuana

Withdrawal Checklist (MWC). Patients reported less sleep disturbance and enhanced

sleep quality. Gabapentin was also associated with diminished urge to use cannabis and

alcohol (Escher et al. 2005).

Quetiapine, an atypical antipsychotic medication, seems to decrease cravings for

cannabis in patients with co-occurred psychotic and substance use disorders (Potvin et

al. 2006). Nevertheless, these findings were only shown in an open label trial and a final

conclusion could only made after verification in a randomised, placebo-controlled trial

design. In summary, different agents, such as bupropion, divaleproex, naltrexone, and

nefazodone were investigated for the treatment of cannabis dependence and for the

prevention of cannabis reinstatement after abstinence, but each medication missing

broader effectiveness (Kleber 2003; UNODC 2002). Oral delta-9-tretrahydrocannabinol

(THC) might be helpful in suppressing cannabis withdrawal.

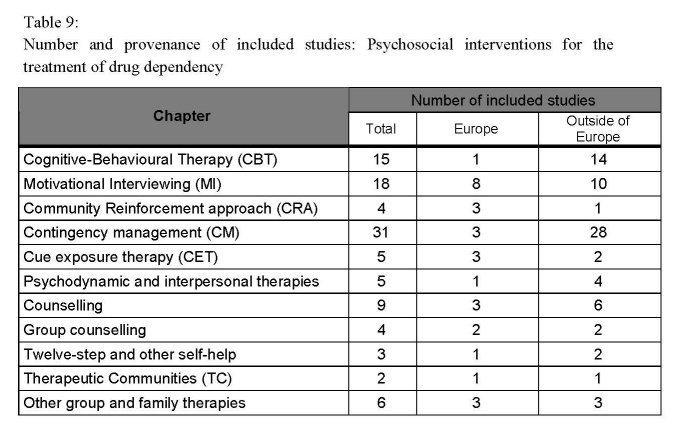

5.3 Psychosocial interventions for the treatment of drug dependency

A wide range of psychosocial interventions is available for the treatment of drug

dependence. As many different study designs were used to explore psychosocial

treatment, it is difficult to compare the individual direct outcomes. The optimal duration

of treatment might be a key point but has hardly been studied. The review of Gowing et

al. found limited strength of evidence that best outcomes are associated with treatment

duration of at least three months with at least weekly sessions (Gowing et al. 2001) The

intensity of treatment has been investigated in a few studies. Comparing a once-weekly

with a thrice-weekly counselling for buprenorphine-naloxone maintenance treatment,

Fiellin et al. did not find significant differences between the groups (Fiellin et al. 2006).

Highly structured relapse prevention seems to be more effective than less structured

interventions, with regard to cocaine users with co-morbid depression (UNODC 2002,

p.14). Treatment should match the patient and should be relevant to the individual

(Gowing et al. 2001). Some form of treatment may be more useful for women than for

men, others might be better for cocaine users than cannabis users (Haro et al. 2006), so

it is important to carefully choose and provide the optimal treatment setting for the

individual.

Often different approaches and methods are combined or compared. Combining

different treatment approaches can lead to improved results. One small American study

compared motivational enhancement plus CBT plus vouchers with motivational

enhancement only or with CBT. The latter two groups showed on average 7 days of

abstinence in the month prior to the last measurement, the three-way group had 13 days

on average (Rigter et al. 2004).

In general, treatment outcomes may differ if treatment is coerced: one study on