17 Systemic aspects of drug treatment

| Reports - Models of Good Practice in Drug Treatment |

Drug Abuse

17 Systemic aspects of drug treatment

Guidelines for treatment improvement

Moretreat-project

Institute of Psychiatry and Neurology, Warsaw, Poland

October 2008

The content of this report does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the European Commission. Neither the Commission nor anyone acting on its behalf shall be liable for any use made of the information in this publication.

Content

1 Introduction

2 Evidence Base

2.1 Assessment of a whole treatment system with stress on needs assessment

2.2 Assessment of a population impact of different treatment systems

2.3 Assessment of methadone maintenance programmes (MMT)

3 Recommendations

3.1 Evidence based treatment policy

3.2 Comprehensive needs assessment

3.3 Implementation of a differentiated treatment system

3.4 Care oordination

3.5 Evaluation and research

3.6 Tailoring to specific needs

References

1 Introduction

“Since there is no one single treatment that is effective for everyone” (UNODC 2003) a treatment system should offer a range of services meeting different needs of its heterogeneous target population(s). A drug treatment system therefore can ideally be described as a network of interrelated treatment and rehabilitation services that form an integrated response to -first of all -health problems of individuals suffering from drug addiction problems in a defined district, municipality, region or country. From a public health perspective a drug treatment system should also have measurable impact on population health and welfare. As proposed by Babor et al (2008) “The cumulative impact of these services should translate into population health benefits, such as reduced mortality and morbidity, as well as benefits to social welfare, such as reduced unemployment, disability, crime, suicide and health care costs” (p. S52). There is substantial evidence that drug treatment is not a single episode but a process that involves a number of treatment services, not infrequently over a number of years (Humphreys and Tucker 2002). It should offer easy access, range of services responsive to the needs of target population, co-ordination of care and continuous after-care and/or relapse prevention (Department of Health 2002; UNODC 2003; UNODC/WHO 2008; NTA 2007a). There is no overall consensus what drug treatment system consists of. One approach distinguishes “open access” services including advice and information as well as harm reduction on the one hand, and “structured” services on the other (UNODC 2003). According to UNODC guide “open access” services include what they call “prevention of adverse consequences” covering education about HIV/AIDS and other blood borne diseases, provision of clean injecting equipment, education about overdose risk exposure, basic survival services and health, welfare and legal advice. Structured services cover three large elements: detoxification, relapse prevention and aftercare. A comprehensive vision of integrated model of care is offered by the British Department of Health. According to its document Models of Care (2002, 2008) substance misuse treatment should consists of five tiers:

• Non-substance misuse specific services (e.g. primary health care, psychiatric services, sexual health, vaccination, emergency services, social services including housing, vocational services, non-specific assessment and care management),

• Open access substance misuse services (e.g. advice and information, drop-in, outreach, motivational interviewing and brief intervention, needle exchange, low threshold prescribing, substance abuse-specific assessment and care management),

• Structured community-based substance misuse services (e.g. counselling and psychotherapy, structured day programmes, structured community based detoxification, structured prescribing/maintenance, structured after-care),

• Residential substance misuse specific services,

• Highly specialised non-substance misuse specific services (e.g. specialist liver disease units, HIV specialist units, forensic services, terminal care, specialist personality disorders units).

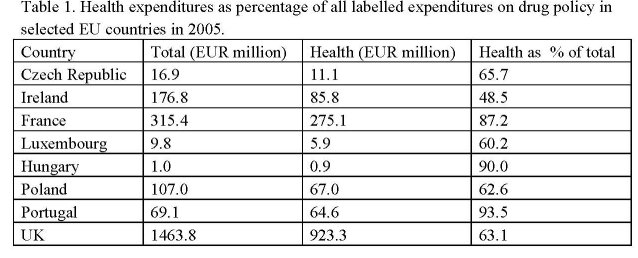

Despite apparently hierarchical structure integrated model of care should secure equal access to all five tires to all substance misusers. Access to one or more tiers should solely be dependent on needs of individual patient. Services offered in different tiers are not alternatives. Majority of clients will need parallel or consecutive services located in different tiers. Services distinguished by different tiers may be provided by a network of agencies to offer a client a choice between different treatment approaches. On the other hand, one agency could offer a range of services rather than one specific service. A definition recently adopted in an EC study reduces scope of drug treatment to structured interventions “drug treatment comprises all structured interventions with specific pharmacological and/or psychosocial techniques aiming at reducing or abstaining from the use of illegal drugs” (Degkwitz Zurhold 2008). Assessment of a treatment system requires information on a number of treatment or harm reduction units, their capacity, and number of clients. Annual budget and employment are also important to assess economic feasibility. Attempts should be made to estimate what proportion of a population in need of treatment is covered. The Level of collaboration among institutions involved as well as allocation of resources in different elements of the system are crucial for its efficient functioning. There are no universal rules. Distribution of power and resources must respond to local needs that have to be assessed while establishing and/or improving drug treatment systems. If a drug treatment system works in a proper way providing a range of care services which are adequate to a range of different needs of addicts, assuring easy access and continuity of care its outcomes are expected to be more paramount than simple sum of outcomes of its elements. Reinforcing systemic aspects of drug treatment may therefore increase its cost-effectiveness which is urgently needed as health expenditures constitute from 50 to over 90 per cent of all labelled expenditures on drug policy in EU countries (EMCDDA 2008b).

Source: EMCDDA 2008b (tables 1-2). Column 3 calculated for a purpose of this report. Despite similar financial commitment for drug treatment, distribution of these enormous expenditures differs substantially from country to country.

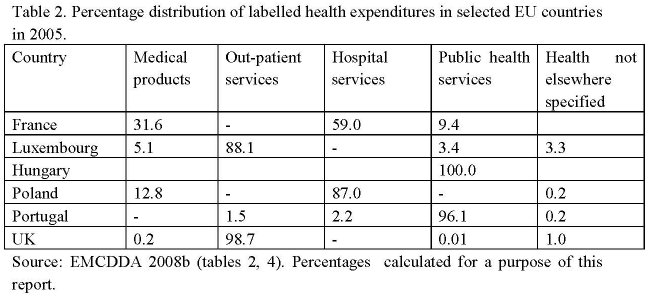

Source: EMCDDA 2008b (tables 2, 4). Percentages calculated for a purpose of this report.

Majority of drug treatment expenditures in France (59%) and particularly in Poland (87%), go to residential services. In contrast, in Luxembourg 88% and in UK 99.7% of those expenditures are located in out-patient sector while almost all drug treatment expenditures in Hungary and Portugal are spent within public health services. These huge differences may partially be attributed to variation in definition of so called “labelled expenditures” adopted within individual countries. Nevertheless, the table above suggests substantial differences in drug treatment systems across Europe with varying focus either on out-patient treatment in some countries or on in-patient treatment in a number of other countries. It seems that there are also countries whose priority is to treat drug addicts within non-specific public health services.

2 Evidence Base

There is a long list of crucial questions to be responded by research on systemic aspects of drug treatment. Should people suffering from drug addiction be treated by general health care, addiction treatment, specific drug treatment? What sector should take responsibility of drug addiction: health care, social welfare, law enforcement or mixture of them? What is rational combination of services to tackle problems associated with drug use in a cost-effective way? Does existing system offers equal access or discriminates certain vulnerable groups? Does a treatment system assures continuity of care, after care and relapse prevention or reinforces revolving door phenomenon? What is its impact on marginalization or social reintegration of clients? What is a population impact of drug treatment? However, a question of drug treatment as a system seems to be neglected by research as much as by existing reporting systems. No attempts were identified to understand different policies of different countries with regard to treatment priorities. This study found very few papers on systemic and/or organisational aspects of drug treatment. Most of them come from eastern Europe, from Bulgaria (two papers), Estonia (one paper), Lithuania (one paper) and Poland (three papers) and from Nordic countries (two papers). Few documents were identified from United Kingdom. In addition, some data may have been obtained from EMCDDA, WHO and UNODC reports. This may reflect low research interest across Europe in drug treatment as a system. The papers identified in this study deal either with the whole drug treatment system or with substitution treatment. The latter interest is justified by relatively short experience with substitution treatment in eastern Europe. Three broad issues can be distinguished:

• Assessment of a whole treatment system with stress on needs assessment.

• Assessment of a population impact of different treatment systems.

• Assessment of methadone maintenance programmes.

2.1 Assessment of a whole treatment system with stress on needs assessment

Needs assessment is crucial for identification of priorities in building or reforming existing system. A useful checklist for evaluation and prioritisation is offered in Needs assessment guidance for adult drug treatment published in UK by National Treatment Agency for Substance Misuse:

• What proportion of your target population has indicated a particular need?

• What are the areas of agreement between service providers and your target population about the target population’s needs? What are the areas of disagreement?

• Have you identified any areas of need among your target population that practitioners were largely unaware of?

• Which of the needs of your target population are currently being met, and which are not being met?

• Which services are easy for your target population to access and why? What are the barriers for your target population in having their needs met?

• What are the risks to your target population (or other people) in not having their needs met?

• How confident do you feel that the information you have gathered is broadly representative of the views of your target population and local practitioners?

• To what extent do existing services have the capacity and ability to meet the identified needs?

• Is funding being directed where it is most needed?

• What are the implications for the planning and funding, and resource allocation processes?

• To what extent do existing partnership priorities fit in with the needs identified in the assessment?” (NTA 2007c: 24-25)?

An important prerequisite of successful needs assessment is a demand for such an assessment expressed by important actors like municipality or national/regional authorities (Moskalewicz, Sieros?awski, D?browska 2006, Moskalewicz, Sieros?awski, Bujalski 2006) or even international organisations (Subata 2007). In addition to financial resources, external support offers better access to existing data sources, and last but not least good prospects for implementation. “Needs assessment is not an end in itself, but a means by which partnerships make increasingly evidence-based and pragmatic decisions about treatment …” (NTA 2007c: 6). Even though no study was identified offering a comprehensive needs assessment at the systemic level, several of them will be reviewed here showing a great potential in system assessment studies and presenting their deficiencies too. Two complementary studies from Bulgaria attempted to assess drug treatment supply on the one hand and its adequacy to patients’ needs, on the other. Mail survey was carried out targeting all out-patient and in-patient services in the country. It was found that the existing network of services provided mainly medical care including detoxification without sufficient stress on psychological and social care (Vassillev, Raycheva, Panayotov, Daskalov 2007). On the other hand, a study carried out among problematic drug users in 8 major cities in Bulgaria (sample size 893) showed their high level of marginalisation indicated by 58% unemployment rate, low education, 40% of respondents without health insurance, 30% share of representatives of ethnic minorities. Profile of majority of respondents suggests an urgent need for psycho-social and harm-reduction care (Vassiliev, Roussev 2007). A mail survey among drug treatment services proved its feasibility in Poland too. A simple form was sent out to all out-patient and in-patient services in the country reaching a two-thirds response rate (sample size = 92 institutions). All in all the study sample consisted in 37% out-patient clinics, 12% detoxification wards, 36% residential rehabilitation centres, 5% methadone maintenance programmes and 10% of services termed as other. The study showed a domination of drug-free treatment prevailing in more than 80% services. Nevertheless, one fourth of out-patient clinics and one fifth of substitution programmes provides sterile injection equipment. The survey revealed striking distribution of the total treatment budget. Out-patient clinics serving more than half of all patients receive less than 10% of the whole budget while long-term residential centres consume over 60% of the budget taking care of 15% of all patients. A number of system assessment measures were elaborated, including:

• Waiting time.

• Retention (percent drop-outs in the beginning of treatment and percent of those completing treatment).

• Number of patients per a staff member.

• Number of patients completing treatment per a staff member.

• Cost per one patient completing treatment.

In most of the above criteria out-patient services proved to be superior including short or non-existent waiting lists, similar as in remaining services retention rates, much higher number of patients per staff member. An annual cost per patient was two times lower compared with residential detoxification, three times lower than in substitution programmes and 20 times lower than in residential rehabilitation (Moskalewicz, Sieros?awski, D?browska 2006).

2.2 Assessment of a population impact of different treatment systems

Majority of studies on treatment efficacy and effectiveness focus on treatment outcomes; in other words on impact of treatment on individuals who received treatment or at least reported to treatment. Studies attempting measurement of population impact of treatment should be interested in such outcomes like alcohol-or drug-related mortality and morbidity in a given area (not only among patients), coverage rates (what proportions of target group was reached), access to treatment as well as cost of treatment. Unfortunately, studies measuring population health impact of drug treatment are practically non-existent while rather seldom in a field of alcohol treatment e.g. North American series of research indicating that increased number of alcoholics in treatment

(i.e. increased coverage rate) is associated with declining liver cirrhosis mortality (Mann et al 1988). Two Nordic studies focused more on impact of treatment system on coverage rates. A study presented by Stenius et al (2005) investigated impact of decentralisation and integration of treatment system on coverage rates, utilisation of treatment and clients’ satisfaction. The study compared two different treatment systems within Stockholm: one in which decentralisation progressed what led to establishment of more integrated out-patient treatment and another one with less integrated in-patient system. As it comes out from the study the more integrated out-patient system proved to have higher coverage rates with regard to more vulnerable groups and led to higher treatment satisfaction. In Denmark a population survey estimating number of heavy consumers in 14 counties was combined with treatment research in respective counties. High diversity across counties was reported with regard to coverage rates and cost of treatment. More successful treatment systems tended to be more accessible, provided more structured treatment and offered tailored treatment for specific groups (Pedersen et al. 2004 quoted after Babor et al. 2008). A recent attempt to review drug treatment coverage rates in EU (Degkwitz, Zurhold 2008) met serious difficulties due to different national definitions of problematic drug users, the reported groups of problematic drug users do not always express a need of treatment (e.g. regular cannabis smokers), some countries focus on opiate users and do not report other problematic drug users, and eventually quality of data provided vary from country to country. The authors of that review realised that “only the data on substitution maintenance treatment allows to draw first conclusions on the treatment coverage”. They found that coverage rate for substitution treatment very from 2.5% in Romania to 50% in Italy and UK among 11 countries providing data comparative enough for international comparisons. In addition, some countries have substantial overlap between out-patient and in-patient treatment that may lead to overestimation of patients in treatment. Very rough review of data provided by individual countries indicates that drug treatment coverage rates range from about 6% in Romania and about 10% in other Eastern European members of EU like in Bulgaria, Slovakia and Estonia to close to 80% in Germany and Ireland, and over 90% in Luxemburg, Malta, Portugal.

2.3 Assessment of methadone maintenance programmes (MMT)

There is large evidence available from high-income countries that maintenance therapy offers numerous benefits not only at the individual level but also at the population level including lower pace of infectious diseases and diminished crime rate (Ward, Mattick, Hall 1998). Recently published report from the WHO collaborative study on substitution therapy carried out in seven countries from South-East Asia, Eastern Europe, Middle East showed high treatment retention, substantial reduction in illicit drug use, diminishing risk behaviours, lower criminality after six months follow-up. The study proved that MMT may achieve similar outcomes in culturally diverse low-and middle-income countries to those reported earlier in high-income countries (Lawrison, Ali et al 2008). As stated earlier, a demand from national or municipal level is important factor in treatment assessment studies. Few years ago, the Warsaw municipality commissioned a study whose aim was to assess accessibility of MMT and demand for this service in Warsaw. A quick and relatively inexpensive study was completed in a couple of months. It consisted of collecting statistical data from existing services, including three MMT and two detoxification units, a survey among current patients receiving MMT, a survey among street addicts and semi-structured interviews with heads of existing MMT-s. Even though opportunistic sampling, the surveys covered over three quarters of patients (180 patients) and over one hundred of street addicts with response rates varying from 73 to 87 per cent. Simple socio-demographic measures disclosed high marginalisation of street addicts compared to those on methadone. All patients on MMT but two had health insurance compared to 44% only among street addicts, all of them but one had stable accommodation compared to 64% among street addicts. Over 90% had a legitimate source of income (salary, pension, welfare) while half of street addicts admitted begging, thefts, dealing as a main source of income. Average waiting time for admission to MMT was over one year even though one third was immediately admitted due to priorities given to seropositive individuals as well as to pregnant women. Long waiting time resulted in prolonged period of drug taking, health problems, HIV and/or HCV infections and legal problems. For those who were admitted, MMT did not meet majority of their problems. A simple indicator of adequacy of care was elaborated showing that one third of those suffering alcohol problems and psychological problems did not get appropriate help in those fields, half of those in need of psychological help was not offered any care in this regard, help in finding housing and/or employment was offered to less than 10 per cent of patients having poor accommodation and/or no employment. Despite insufficient services, three quarters of street addicts expressed interest in participating in MMT. Capture-recapture as well as benchmark methods gave similar estimates of a number of injecting drug users in Warsaw. Both estimates combined with demand for MMT expressed in the survey allowed a conclusion that only one sixth of the demand is satisfied by existing services. Taking under consideration place of residence of addicts and location of existing services, the study recommended establishment of six new services spread closer to their potential users (Moskalewicz, Sieros?awski, Bujalski 2006). An evaluation report on MMT in Estonia provides an useful guidance how to evaluate treatment system or its segment within very limited resources applying qualitative interviews. An evaluation expert commissioned by UNODC visited several MMT in three cities studying available documentation and interviewing 14 staff members and 8 patients. He concluded that “interviewed MMT management representatives and providers indicated that they did not receive adequate training before they started MMT and were “left alone” to learn from their own mistakes. During the past years there was little or no ongoing in-service training for the staff, including physicians, nurses, social workers, psychologists. Some MMT providers reported that while implementing MMT they have faced critical organizational and clinical problems, and did not know where to get support, advice or supervision. As an outcome result, MMT programs were developing “their own approaches”… “in relative isolation”. Interviews with patients showed that patients were disappointed with some aspects of structured MMT, particularly with severe limitations on travel. They felt chained to a MMT site which they were obliged to visit every day and seemed to be unaware of a possibility to receive sufficient amount of methadone to carry on with them while travelling or spending vacations in the country (Subata 2007). A question of take-home methadone was investigated in Poland in 2003 where a patient had to visit MMT site every day to swallow his/her methadone. A mail survey was carried on in all existing MMT throughout the country with response rate of 90% (10 out of 11 existing sites responded). Despite lack of legal provisions practically all sites under study offered take-home methadone and elaborated specific rules with this regard. This “privilege” was given after a long period of not taking any illicit drugs. Major premises were physical health, employment, need to take care of other family member (Habrat, Chmielewska, Baran-Furga 2003). Another study run in Lithuania discusses impact of MMT on health and social integration of people participating in MMT in 3 major cities in Lithuania. The study covered several hundred patients being relatively old (mean age 32.6 years) and relatively well educated (60% having 11+ years of education). WHO Quality of Life questionnaire short version (WHOQOL-BREF 26-items version) and Opioid Treatment Index were administered among patients. The study showed that MMT programmes in Lithuania had potential to affect physical dependence to opioids, but they are not so effective to social and psychological aspects of dependence. To increase impact on quality of life it is recommended to offer more psychological consultations and to employ in MMT more psychologists and social workers (Vangas 2007).

3 Recommendations

Current drug research in which studies on drug treatment as a system have no priority whatsoever, does not provide enough evidence to respond to a crucial question how scarce resources in drug treatment should be allocated. Considering scarcity of systemic research and their great potential following recommendations can be formulated: Recommendations

3.1 Evidence based treatment policy

Drug treatment policy should be formulated and adopted by relevant authorities at the national, regional and local levels. Treatment policy should be integrated within general drug policy on the one hand, and with general treatment policy, on the other. Instead of promoting dominant treatment approaches, drug treatment policy should encourage development of drug treatment system(s) at the national and local levels composed of coordinated network of open-access and structured services. Treatment policy should be based on evidence of effectiveness and cost-effectiveness rather than on existing traditions and convictions.

3.2 Comprehensive needs assessment

Needs assessment at the national and local level should precede decisions aiming at expanding or ameliorating existing treatment system. Needs assessment should be methodologically sound but politically – participatory including commitment from local authorities as well as participation of current and potential clients. Comprehensive assessment includes not only epidemiological data but also expectations of potential users of a treatment system as well as available treatment resources with focus on human resources, their competence, attitudes and commitments. There is a variety of components in needs assessment. Majority of them would include:

• Reviewing existing sources of information on drug use and related harms.

• Mapping existing services, and their capacities incl. personal and material resources.

• Tracing clients movements within existing treatment system.

• Assessing existing barriers.

• Identification of unmet needs of current clients.

• Identification of needs of population(s) not in treatment.

• Identification of harms associated with limited access to treatment.

3.3 Implementation of a differentiated treatment system

Treatment system should offer a range of services and be tailored to a range of specific needs of heterogeneous target groups. System must offer services which are accessible, of different intensity, requiring varying client’s commitment. Clients’ needs are very likely to go beyond health needs and to include social, legal and economic dimensions. Therefore, treatment system should spread across different sectors: health, social welfare, criminal justice, employment et cetera. If restricted to specialised drug treatment only, following elements may be distinguished (elaborated from NTA 2007b).

Regular treatment

• counselling,

• detoxification,

• psychotherapy,

• rehabilitation.

After care support

• housing

• vocational training

• employment

• health problems

• psychological problems

• legal problems

Harm reduction

• general health assessment and care

• vaccinations against HBV

• screening for HCV

• needle exchange

• supervised consumption, including maintenance treatment.

3.4 Care oordination

Coordination between different elements of the system including inter-sectoral coordination is crucial. It will take into account systemic coordination i.e. appropriate distribution of tasks and resources as well as individual case coordination. To this end, effective communication structures should be established to secure efficient referrals and continuity of care.

3.5 Evaluation and research

Research on drug treatment as a system should be among top priorities among EU research programmes as well as national and regional research funding schemes. Drug treatment system studies do not need to be expensive. Simple approaches work and bring useful information on treatment demand, needs assessment, adequacy of treatment, feasibility, effectiveness and even cost-effectiveness. New approaches need to be invented to study continuity of treatment, level of system integration and population impact of treatment.

3.6 Tailoring to specific needs

Population impact of drug treatment system should be continuously studied. This includes proportion of population in-need that receives treatment (coverage rates), morbidity and mortality due to drug-specific causes such as HIV, hepatitis, overdose, social marginalisation (e.g. homelessness, unemployment), crime rates.

References

Babor T.F., Stenius K., Romelsjo A. (2008) Alcohol and drug treatment systems in

public health perspective: mediators and moderators of population effects.

International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research; 17(S!): S50-S59.

Degkwitz P., Zurhold H. (2008) Overview of types, characteristics, level of provision

and utilisation of drug treatment services in European Member States and Norway.

Department of Health (2002) Models of Care for substance misuse treatment.

EMCDDA (2008b) Towards a better understanding of drug-related expenditure in

Europe. Lisbon: European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Abuse.

Habrat B., Chmielewska K., Baran – Furga H. (2003) Regulacje prawne i praktyka

kliniczna w zakresie wydawania środków substytucyjnych do domu. Alkoholizm i

Narkomania 16, 3-4, 147-154;

Lawrinson P., Ali R. et al. (2008) Key findings from the WHO collaborative study on

substitution therapy for opioid dependence and HIV/AIDS. Addiction 103: 1484-

1492.

Mann R.E., Smart R.G., Anglin L., Rush B. (1988) Are decreases in liver cirrhosis rates

a result of increased treatment for alcoholism? British Journal of Addicition. 83: 683-

688.

Moskalewicz J., Sierosławski J., Dąbrowska K. (2006) Ocena systemu leczenia i

rehabilitacji osób uzależnionych od substancji psychoaktywnych. Alkoholizm i

Narkomania 19,4, 327-355;

Moskalewicz J., Sierosławski J., Bujalski M. (2006) Dostępność programów

substytucyjnych Warszawie. Manuscript, Warsaw: Institute of Psychiatry and

Neurology.

NTA (2007a) Final Results of the Annual Report 2006-07. London: National Treatment Agency for Substance Abuse

( w_commissioning%20&%20harm%20reduction.pdf).

NTA (2007b) Adult drug treatment plan 2008/09. Guidance notes on completion of the

plan for strategic partnership. London: National Treatment Agency for Substance

Misuse.

NTA (2007c) Needs Assessment Guidance for Adult Drug Treatment; National

Treatment Agency for Substance Misuse.

Pedersen M.U., Vind L., Milter M. Gronbek M. (2004) Alkoholbehandlingsindsatsen i

Danmark – semmenlignet med Sverige. Aarhus: Center for Rusmiddelforsknig.

Stenius K., Storbjörk J., Romelsjö A. (2005) Decentralisation and integration of

addiction treatment: Does it make any difference? A preliminary study in Stockholm

county. Paper presented at the 31st KBS Annual Alcohol Epidemiology Symposium,

Riverside, CA.

Subata E. (2007) Evaluation of methadone maintenance therapy programs in Estonia.

Not published report.

Vangas A. (2007) Economical analysis of methadone maintenance treatment in

Lithuania. Public Health Reasearch Council Of Kaunas. University of Medicine.

Vassilev M., Raycheva T., Panaytov A., Daskalov K. (2007) Estimation of treatment

needs: estimation of supply of treatment. Manuscript.

Vassilev M., Roussev A. (2007) Treatment demand and barriers to the treatment access

for problematic drug users in Bulgaria. Conference proceeding.

Ward J., Mattick R., Hall W., eds (1998) Methadone maintenance treatment and other

opioid replacement therapies. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers.

UNODC (2003) Drug Abuse Treatment and Rehabilitation: A Practical Planning and

Implementation Guide. Vienna: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

UNODC/WHO (2008) Principles of Drug Dependence Treatment. Discussion paper.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|