12 Detoxification

| Reports - Models of Good Practice in Drug Treatment |

Drug Abuse

12 Detoxification

Guidelines for treatment improvement

Moretreat-project

NAC, Kings College London

October 2008

EUROPEAN COMMISSION HEALTH & CONSUMER PROTECTION DIRECTORATE-GENERAL Directorate C -Public Health and Risk Assessment

The content of this report does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the European Commission. Neither the Commission nor anyone acting on its behalf shall be liable for any use made of the information in this publication.

Content

1 Introduction

1.1 Definitions

1.2 Aims and objectives

2 Research evidence base.

2.1 Treatment environment and holistic treatment and care

2.2 Effectiveness by treatment setting

1.3 Prescribing for opiate dependence

3 Recommendations

3.1 Access to care

3.2 Pathways of care

3.3 Assessment

3.4 Staffing Competencies

References

Introduction

1.1 Definitions

Context

Detoxification denotes the clearing of toxins from the body of a patient who is intoxicated and/or dependent on substances of abuse. The term is also widely used to describe a set of interventions aimed at managing acute intoxication and withdrawal, so that the effects of drugs are eliminated from dependent users in a safe and effective manner (WHO, 2006). Supervised detoxification may prevent potentially life-threatening complications that might occur if the patient was left untreated. Detoxification can also be seen as a form of palliative care for those who want to become abstinent or must observe mandatory abstinence because of their legal situation or because they have been hospitalized (SAMHSA, 1995). Detoxification is often used as a first step in the patient's drug treatment career. For example, some residential facilities require patients to have become drug-free before entering treatment and some methadone maintenance programmes require patients to have at least attempted detoxification.

Philosophy and approach

Detoxification needs to be placed in the context of other treatment interventions, for detoxification alone does not produce long-term abstinence. Detoxification should be managed in a way that causes as little discomfort as possible. Many addicts are anxious about detoxification and have fears about the effects of withdrawal, deterring some people from seeking treatment. The discomfort of withdrawal symptoms may lead the patient to leave treatment. As part of a continuum of care for substance-related disorders detoxification should consist of three essential components: evaluation, stabilization and fostering patient readiness for and entry into treatment (SAMHSA, 1995). Those people seeking detoxification should have access to all the components of the detoxification process no matter the setting or the level of intensity. All persons requiring treatment for substance use disorders should receive treatment of the same quality and appropriate thoroughness. Detoxification provides an important therapeutic encounter between the patient and the clinician and should be used as an opportunity to provide biomedical assessment, referral to appropriate services and linkage to treatment services (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2008a; SAMHSA, 1995). Detoxification should be delivered by staff who are competent in delivering the intervention and receive appropriate supervision (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2008a). It should also be remembered that detoxification is not often successful, particularly at the first attempt (UK. Department of Health, 2007). In order to obtain informed consent, treatment staff should give patients detailed information about detoxification and attendant risks. This information should include:

• The physical and psychological characteristics of withdrawal

• The use of non-pharmacological approaches to manage or to cope with withdrawal symptoms

• The loss of opioid tolerance following detoxification and the resulting increased risk of overdose and death from illicit drug use that may be potentiated by the use of alcohol or benzodiazepines

• The importance of continued support, along with psychosocial and appropriate pharmacological interventions, to maintain abstinence, treat comorbid mental health problems and reduce the risk of adverse outcomes, including death (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2008a).

1.3 Relevance of the problem

The European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA, 2008) have estimated an average prevalence of problem opioid use of between four and five cases per 1,000 of the population aged 15-64 in Europe and Norway. While drawing attention to the limited data supporting these estimates, the EMCDDA further estimates that this rate suggests that 1.5 million people experience problem opioid use in Europe. Similar estimates for cocaine are not available for Europe as a whole but available for only three countries, Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom. Here the estimates from these countries are between three and six problem users of cocaine users per 1,000 adults aged 15-64.

Using its Treatment Demand Indicator data the EMCDDA has recorded opioids as the principal drug in around 40% of the drug treatment requests recorded in 2005. Recent data suggests a decrease in new requests for opioid treatment, with Bulgaria and the United Kingdom as the only European countries not reporting a decrease. In 2005, there were around 45,000 demands for treatment across Europe where cocaine was reported as the primary drug. Cocaine is reported as a secondary problem drug by around 15% of all outpatient clients. Most countries in Europe report a low proportion of cocaine users among all clients in drug treatment, although the Netherlands and Spain have reported high proportions of 35% and 42% respectively in 2004 (EMCDDA, 2008). Benzodiazepines are infrequently the primary drug reported by those coming for treatment but are widely used by problem drug users. For example, around 25% of treatment clients recorded by the UK Drug Treatment Outcomes Research Study (DTORS) reported benzodiazepine use (Jones et al, 2007).

1.2 Aims and objectives

Aims of detoxification

The aim of detoxification is to eliminate or reduce the severity of withdrawal symptoms in a safe and effective manner when the physically dependent user stops taking drugs (WHO, 2006). Detoxification programmes should include the following elements:

• An assessment of the psychological, psychiatric, social and physical status of patients using defined assessment schedules

• An assessment of the degree of misuse and/or dependence on relevant classes of drugs, notably opioids, stimulants, alcohol and benzodiazepines

• To define a programme of care and to develop a care plan to carry out a risk assessment

• To prescribe medication safely and effectively to achieve withdrawal from psychoactive drugs

• To identify risk behaviours and offer appropriate counselling to minimise harm

• To assess the longer-term treatment needs of patients and provide an appropriate discharge care plan

• To assess and refer patients to other treatments as appropriate

• To monitor and evaluate the efficacy and effectiveness of prescribing interventions

• To provide referral to other services as appropriate (NTA, 2002)

Client groups served

Detoxification patients are those who meet International Classification for Diseases (ICD) 10 or Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) IV dependence criteria. This group comprises those who are seeking abstinence from their main problem drug. Patients may also be concurrently using opioids, benzodiazepines and stimulants.

Eligibility

Those who are physically dependent on one or more classes of drugs and have made an informed and appropriate decision to undergo detoxification should be eligible for detoxification. Those who have had at least one previous unsuccessful detoxification episode within a community setting and who require a high level of medical and nursing support because of significant comorbid physical and/or psychiatric problems or are polydrug users requiring detoxification from several drugs should be appropriate for inpatient detoxification.

Priority groups

Exclusion

Detoxification services are not appropriate for those who have serious psychiatric morbidity requiring acute psychiatric treatment or have serious physical morbidity such as a life-threatening physical illness (NTA, 2002).

2 Research evidence base.

2.1 Treatment environment and holistic treatment and care

2.2 Effectiveness by treatment setting

Methadone

While community detoxification is the most widely used option, consistently low completion rates have been reported for opiate dependent patients detoxified in the community. One UK study found that 51% were drug-free at 6 month follow-up. Other studies have found abstinence rates between 17 and 28% in outpatient settings. This compares to rates of 80-85% recorded for inpatient detoxification programmes (Gossop et al, 1986; Dawe, 1991; Gossop & Strang, 1991). The only controlled study of inpatient versus outpatient treatment in the UK found that 70% of those in inpatient services were drug-free on discharge compared to 37% of those in an outpatient setting (Wilson, 1975, Day et al, 2005). However, the numbers in this study were small and a Cochrane review concluded that there is a lack of good quality research to guide practice in this area (Day et al, 2005).

Buprenorphine

There is limited evidence for the relative efficacy of outpatient versus inpatient detoxification using buprenorphine. One study found only 12% of patients treated with buprenorphine in an inpatient setting achieved abstinence compared to 24% in a conventional outpatient setting (Digiusto et al, 2005). Another study compared similar detoxification regimens found in a community-based programme in a specialist setting with one in a primary care setting. The settings had similar efficacy with 71% completing detoxification in the primary care setting and 78% in the specialist setting (Gibson et al, 2003)

1.3 Prescribing for opiate dependence

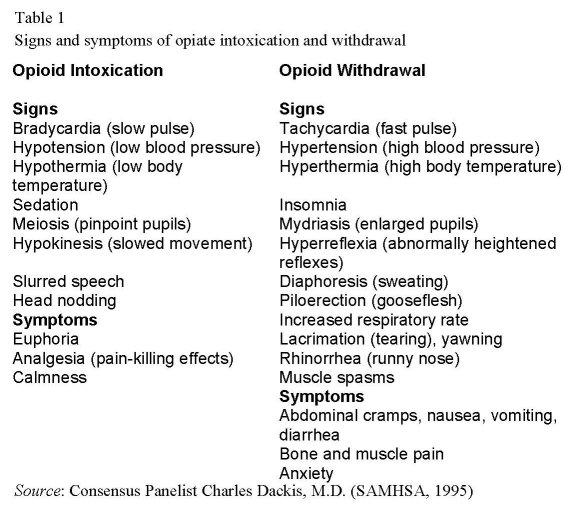

Chronic opiate use leads to withdrawal symptoms which are uncomfortable and can be highly unpleasant (SAMHSA, 1995), However, it is rarely associated with life threatening problems that may arise with alcohol or benzodiazepine withdrawal (Mattick and Hall, 1996).

The withdrawal syndrome is similar for all the opiates with some variance in severity, time of onset and duration of the symptoms depending on the opiate used, duration of use, the daily dose and the interval between doses (SAMHSA, 1995). Withdrawal symptoms are usually at their most intense between 24 and 72 hours. Symptoms will gradually lessen in intensity although it may be a week or 10 days before the addict begins to feel better again. . A wide range of criteria have been used for the evaluation of opiate detoxification programmes. These include severity of withdrawal symptoms; completion of detoxification, achievement of an initial period of abstinence; engagement in subsequent treatment (DiGiusto et al, 2005).

Methadone

The most extensively tested medication for detoxification is the long-acting opioid agonist, methadone. Methadone is a long-acting agonist at the u-opioid receptor site, which displaces heroin or other abused opiates and restabilizes the site and reverses opioid withdrawal symptoms (SAMHSA, 1995). The initial dose of methadone is determined by estimating the amount of opiate use by gauging the patient's response to administered methadone. The patient should be physically examined to screen for signs of opiate withdrawal. Avoidance of overmedicating is important to avoid overdose, while underdosing is important to avoid so unnecessary discomfort is also avoided (SAMHSA, 1995). While there is little evidence that that there is a relationship between opiate dose and withdrawal severity, one recent study found that patients on higher doses of methadone in an inpatient treatment service reported more severe withdrawal symptoms than those on lower doses, although methadone dose did not have an effect on completion rates or length of stay in hospital (Glasper et al, 2008). Detoxification with tapered doses of methadone shows fewer withdrawal symptoms and fewer drop-outs than placebo (Amato et al, 2005). Methadone has been found to have a better adverse-event profile, particularly in relation to hypotension, compared to clonidine and better detoxification completion rates when compared to lofexidine (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2008a). Extant studies do not indicate a difference between buprenorphine and methadone for detoxification completion rates but there is no data available to compare abstinence outcomes (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2008a). However, methadone detoxification is marked by high attrition rates and up to 86% do not complete their detoxification programme (Sees et al, 2000). A study demonstrated that flexible negotiated detoxification schedule where patients could regulate the rate of their methadone reduction was not superior to fixed rate programmes in an outpatient setting. Fewer of the patients in the negotiated rate group completed the programme and there was no difference in retention between the two groups (Dawe et al, 1991).

Buprenorphine

A Cochrane review found that the evidence for the effectiveness of buprenorphine for managing opioid withdrawal is limited (Gowing et al, 2004). With the limited data available the Cochrane review concluded that the efficacy of buprenorphine with regard to treatment retention, illicit drug use and suppression of withdrawal symptoms is similar to that of methadone, although detoxification with buprenorphine can be conducted more quickly than with methadone (Gowing et al, 2004). There are also no significant differences between the two medications in completion of withdrawal, while a recent review found low rates of abstinence among treatment completers in the studies reviewed (Gowing et al, 2004; Horspool et al, 2008). Buprenorphine is more effective than clonidine in reducing the signs and symptoms of opioid withdrawal, retaining patients and in supporting the completion of withdrawal. A preliminary study has found that patients codependent on opioids and benzodiazepines undergoing detoxification with buprenorphine reported less severe withdrawal symptoms during treatment than with methadone and were more likely to complete treatment (Reed et al, 2007)..

Dihydrocodeine

Based on the results of two RCTs comparing dihyrocodeine and buprenorphine for detoxification, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence(NICE) concluded that those undergoing dihydrocodeine detoxification were less likely to be abstinent at the end of their detoxification programme and no more likely to complete treatment than those receiving buprenorphine (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health 2008a).

Clonidine and lofexedine

A group of non-opioid drugs called alpha-2-adrenergic agonists, which include clonidine and lofexedine, have been found to reduce noradrenergic hyperactivity seen in opiate withdrawal and have been consequently been used alone or with a rapid reduction in opioid dose to manage opioid withdrawal. Clonidine has been found to produce a rapid and prolonged reduction of withdrawal symptoms in open and double -blind trials (Gossop, 1988). Clonidine has been found to be as equally effective as low doses of methadone in suppressing withdrawal symptoms (Gowing et al, 2004). However, clonidine does not completely eliminate withdrawal symptoms and patients experience more severe withdrawal symptoms in the first few days of clonidine treatment while methadone patients experience more discomfort at a later stage (Gossop,1988). However, patients are more likely to leave treatment early with clonidine and completion rates for clonidine detoxification are low, ranging from 20 to 40 per cent (Kleber, 2006). A recent NICE review found there was no evidence that clonidine is more effective than lofexedine for managing opioid withdrawal and, because of its greater side effect profile, suggested that clonidine is not used in routine practice (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health 2008a ).

Lofexedine has comparable clinical efficacy to clonidine but has a slight advantage of fewer side effects, and in particular less postural hypotension, a fall in blood pressure when the position of the body changes (Buntwal et al, 2000). A double blind study which randomised low dose opiate patients to lofexedine and clonidine found that both drugs could be used successfully for outpatient detoxification but that treatment with clonidine required more input in terms of staff time (Carnwath and Hardman, 1998). While a Cochrane review found no significant differences between 2-adrenergic and methadone for detoxification treatment in opioid dependents, the additional provision of symptomatic medications enhanced the effectiveness of adrenergic agonists (Amato et al, 2005). In particular, their combination with opioid antagonists such as naltrexone and naloxone has been found to lead to less severe withdrawal symptoms in detoxification compared to treatment with lofexedine alone (Buntwal et al, 2000; Gowing 2004).

Opiate antagonists

Rapid opiate detoxification regimens have mainly involved the use of opiate antagonists, naloxone and/or naltrexone to precipitate an acute withdrawal state with the ensuing withdrawal symptoms managed with a variety of medications and techniques including concurrent treatment with an alpha-2-agonist such as clonidine and /or benzodiazeopine induced sedation (Bearn et al, 1999). Some patients may be attracted to this procedure because a rapid detoxification treatment includes a briefer, less uncomfortable transition from dependence to abstinence. During the 1990s there was international interest in the use of antagonists with drug anaesthesia to detoxify opiate addicts. However, a recent randomised controlled trail found that rapid detoxification with anaesthesia did not lead to improved outcomes compared to rapid detoxification without anaesthesia (De Jong et al, 2005). In addition, there is an absence of controlled trials to evaluate the risk/benefit ratio (Stine et al, 2003).

Buprenorphine and naloxone

A number of recent RCTs have demonstrated that rapid detoxification with buprenorphine-naloxone is safe and well-tolerated by patients with positive outcomes for treatment retention, detoxification completion and abstinence rates in treatment (Amass et al, 2000; Ling et al, 2005).

Other medications for symptomatic treatment

Opiate detoxification when properly conducted usually can be conducted without significant patient discomfort. However patients receiving adequate detoxification doses may still complain of withdrawal symptoms such as diarrhoea or insomnia and which can be treated with adjunctive medications (SAMHSA, 1995). However, there is no systematic evidence that any of the medications work to improve outcomes (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2008a; UK. Department of Health, 2007).

Psychosocial interventions in combination with detoxification

The majority of the studies examining psychosocial interventions combined with detoxification have featured contingency management techniques during community detoxification (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2008b). Contingency management in these studies usually begun after stabilisation and continued through the detoxification process until treatment was completed. Patients receiving contingency management were more likely to be abstinent at the end of treatment and to complete treatment than those patients who did not receive it (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2008b). This outcome was found with both short-term and longer term detoxification programmes.

Managing benzodiazepine withdrawal

Benzodiazepines have the potential for misuse and dependence and are also often taken in combination with opioids or stimulants. Medical complications of benzodiazepine withdrawal are similar to the problems seen in alcohol withdrawal. Seizures may occur without being preceded by other symptoms of withdrawal but seizures and delirium are rare. Patients have also reported distortions in smell, taste and other perceptions (SAMHSA, 1995). Panic attacks which may emerge during withdrawal may be a result of the emergence of the patient’s underlying symptomatology rather than a withdrawal effect (SAMHSA, 1995). There are a limited number of controlled trials that can provide guidance regarding benzodiazepine withdrawal but the evidence available supports a stepped care approach (Oude Vashaar et al, 2006). Those with low dose benzodiazepine dependence may experience anxiety, apprehension, dizziness and insomnia during withdrawal but do not require special treatment. During early abstinence these patients should be given support and reassurance that the withdrawal effects will soon reduce or disappear (Petursson and Lader, 1984). A meta-analysis of studies found that minimal interventions are effective strategies for reducing benzodiazepine consumption when compared to care as usual (Oude Vashaar et al, 2006). If minimal intervention fails then supervised gradual withdrawal can be initiated (Petursson and Lader, 1984). However, prescribing medication to assist withdrawal should only be initiated where there is evidence of dependence based on clinical information taken form the patient and significant others, observed symptoms and drug testing (SAMHSA, 1995; UK. Department of Health, 2007). Identifying the specific name of medication, dose and duration of use are vital (SAMHSA, 1995). If the patient is receiving a long-term dose of methadone for concomitant opioid dependence, the methadone dose should be kept stable through the benzodiazepine reduction period (UK Clinical Guidelines). The treatment aim for benzodiazepine detoxification should be to prescribe a reducing regimen for a limited period of time. Diazepam has been recommended for use in withdrawal regimens. Diazepam has a relatively long half-life and is available in different strength tablets. It can be given as a once-a-day dose. Benzodiazepines, including diazepam, can be withdrawn in proportions of about one-eighth of the daily dose every fortnight. Where the dependence is on therapeutic doses then the dose can be reduced initially by 2-2.5 mg and if withdrawal symptoms appear the dose can be maintained until symptoms improve. If the patient is experiencing severe withdrawal symptoms then the dose may need to be increased to alleviate symptoms (UK. Department of Health, 2007).

Adjunctive therapies such as structured psychosocial interventions, counselling, support groups and relaxation may be helpful to alter negative cognitions related to medication cessation, provide patient education and provide cognitive and behavioural techniques for anxiety reduction and sleep enhancement during withdrawal (UK. Department of Health, 2007; SAMHSA, 1995).

Managing stimulant detoxification

Long-term stimulant use may lead to neuroadaptive states and subsequent withdrawal effects if stimulant use is discontinued. While a number of pharmacological treatments have been tried, there are no medications with proven efficacy to treat stimulant withdrawal. Antidepressant drugs such as fluoxetine have been used to manage the depressive episodes associated with stimulant withdrawal. There is no evidence that antidepressants have any effect on the withdrawal effects of stimulants regardless of the type of antidepressant used (Lima et al, 2001).

3 Recommendations

3.1 Access to care

Access to the service

Detoxification should be a readily available option for people who are dependent and have expressed an informed and appropriate choice to become abstinent (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2008a). Information should be made available on criteria for access to detoxification programme. The material should describe who the service is intended for and what are the expected waiting times for entry (NTA, 2002).

3.2 Pathways of care

Programme duration

Most detoxification treatments with methadone use a linear reduction schedule with regular equal dose decrements from an individually tailored starting dose to zero. Treatment programmes typically last 10-28 days. While research suggests that longer periods in treatment with a critical period of 28 days may predict better outcomes, there is little evidence to support more protracted detoxification schedules which may lead to residual symptoms continuing after treatment has finished.

Detoxification with lofexedine can be achieved over periods as short as five days (Bearn et al, 1998).

Setting

A range of settings have been used for detoxification, including specialist in-patient drug dependence units, psychiatric hospital wards, residential rehabilitation programmes, community-based settings and prisons. Different settings may suit different users in different circumstances or suit the same user at different stages of their career (Gossop, 2003). Substance abuse facilities may or may not have the necessary services to provide adequate assessment and treatment of co-occurring psychiatric conditions and biophysical problems. In-patient mental health facilities are available generally to provide treatment for substance use disorders and co-occurring psychiatric conditions Inpatient detoxification provides 24-hour supervision, observation and support for patients who are intoxicated or experiencing withdrawal. Residential settings vary in the level of care they can provide. Community-based programmes should be offered to those considering detoxification except for those

• Have not benefited from earlier community-based detoxification

• Need medical and/or nursing care because of significant comorbid physical or mental health problems

• Require complex polydrug detoxification

• Are experiencing significant social problems that limit to the benefits of community detoxification (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2008a).

In patient care should normally only be considered for people who need a high level of medical and/or nursing support for significant and severe comorbid physical or mental health problems or need concurrent detoxification from alcohol and other drugs which need a high level of medical and nursing expertise (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2008a). Residential detoxification should normally only be considered for those who have significant comorbid physical or mental health problems or need sequential detoxification from alcohol and opioids or concurrent detoxification from opioids and benzodiazepines. It may also be considered for those who have less severe levels of dependence, eg those who have only recently started their drug use, or would benefit from the residential setting during and after detoxification (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2008a).

3.3 Assessment

Those presenting for opioid detoxification should be assessed to establish the presence and severity of opioid dependence, as well as misuse of and/or dependence on other substances including alcohol, benzodiazepines and stimulants

Assessment should include

• Urinalysis to aid confirmation of the use of opioids and other drug use/ dependence

• A clinical assessment of the signs of withdrawal if present

• The taking of a history of drug and alcohol use and previous treatment episodes

• A review of current and previous physical and mental health problems

• Risk assessment for self-harm, loss of opioid tolerance and the misuse of drugs or alcohol as a response to opioid withdrawal symptoms

• An assessment of present social and personal circumstances

• A consideration of the impact of drug misuse on family members and any dependents

• Development of strategies to avoid risk of relapse (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2008a).

Detoxification for those women who are opioid dependent during pregnancy should be undertaken with caution. Comorbid physical and mental health problems should be treated alongside the opioid dependence (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2008a).

3.4 Staffing Competencies

Community detoxification should be co-ordinated by competent primary or specialist practitioners (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2008a).Residential and in-patient detoxification programmes should be staffed by multidisciplinary teams with an emphasis on medical and nursing staff.

References

Amass L, Kamien JB, Mikulich SK (2000) Efficacy of daily and alternate-day dosing regimens with the combination buprenorphine-naloxone tablet. Drug and Alcohol Dependence: 58(1-2), 143-152.

Amato L, Davoli M, Minozzi S, Ali R, Ferri MMF (2005) Methadone at tapered doses for the management of opioid withdrawal. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews: 3.

Bearn J, Gossop M, Strang J (1998) Accelerated lofexidine treatment regimen compared with conventional lofexidine and methadone treatment for in-patient opiate detoxification. Drug and Alcohol Dependence: 50 (3), 227-232.

Bearn J, Gossop M, Strang J (1999) Rapid opiate detoxification treatments. Drug and Alcohol Review: 18(1), 75-81.

Buntwal N, Bearn J, Gossop M, Strang J (2000) Naltrexone and lofexidine combination treatment compared with conventional lofexidine treatment for in-patient opiate detoxification. Drug and Alcohol Dependence: 59(1), 183-188.

Carnwath T, Hardman J (1998) Randomised double-blind comparison of lofexidine and clonidine in the out-patient treatment of opiate withdrawal. Drug and Alcohol Dependence: 50(3), .251-254.

Dawe S, Griffiths P, Gossop M, Strang J (1991) Should opiate addicts be involved in controlling their own detoxification? A comparison of fixed versus negotiable schedules. British Journal of Addiction: 86(8), 977-982.

Day E, Ison J, Strang J (2005) Inpatient versus other settings for detoxification for opioid dependence (review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews: 4.

Digiusto E, Lintzeris N, Breen C, Kimber J, Mattick RP, Bell J, Ali R, Saunders JB (2005). Australian National Evaluation of Pharmacotherapies for Opioid Dependence Research Group. Short-term outcomes of five heroin detoxification methods in the Australian NEPOD Project. Addictive Behaviors: 30(3), 443-456.

European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) (2008). Annual Report 2007. Lisbon: EMCDDA.

Gibson AE, Doran CM, Bell JR, Ryan A, Lintzeris N (2003). A comparison of buprenorphine treatment in clinic and primary care settings: a randomised trial. Medical Journal of Australia: 179(1), 38-42.

Glasper A, Gossop M, de Wet C, Reed L, Bearn J (2008).Influence of the dose on the severity of opiate withdrawal symptoms during methadone detoxification.

Pharmacology: 81(2), 92-96.

Gossop M (1988) Clonidine and the treatment of the opiate withdrawal syndrome. Drug and Alcohol Dependence: 21(3), 253-259.

Gossop M (2003) Drug addiction and its treatment. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gossop M, Strang J (1991) A comparison of the withdrawal responses of heroin and methadone addicts during detoxification. British Journal of Psychiatry: 158, 697-699.

Gossop M, Johns A, Green L (1986) Opiate withdrawal: inpatient versus outpatient programmes and preferred versus random assignment to treatment. British Medical Journal: 293(6539), 103-104.

Gowing L, Ali R, White J (2004) Buprenorphine for the management of opioid with drawal. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews: 4

Gowing L, Farrell M, Ali R, White JM.(2004) Alpha2 adrenergic agonists for the management of opioid withdrawal. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews: 4.

Hall W, Ward J, Mattick RP. eds. (1998). Methadone maintenance treatment and other opioid replacement therapies. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers.

Horspool MJ, Seivewright N, Armitage CJ, Mathers N (2008) Post-treatment outcomes of buprenorphine detoxification in community settings: a systematic review. European Addiction Research, 14(4), 179 – 185.

Jones, A, Weston S, Moody A, Millar T, Dollin L, Anderson T, Donmall M. (2007). The drug treatment outcomes research study (DTORS): baseline report. London: Home Office.

Kleber HD, HD, Weiss RD, Anton RF, Rounsaville BJ, George TP, Strain EC, Greenfield SF, Ziedonis DM, Kosten TR et al (2006) Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with substance use disorders. Washington: American Psychiatric Association.

Lima M, Farrell M, Lima Reisser AARL, Soares B. (2003) Antidepressants for cocaine dependence. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews: 2.

National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (2008a).Drug misuse: opioid detoxification. London: British Psychological Society and the Royal College of Psychiatrists.

National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (2008b).Drug misuse: psychosocial interventions. London: British Psychological Society and the Royal College of Psychiatrists.

National Treatment Agency (2002). Models of Care. London: NTA

Oude RC, Voshaar RC, Couvée JE, Van Balkom AJLM, Mulder PGH, Zitman FG (2006) Strategies for discontinuing long-term benzodiazepine use. Meta-analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry: 189, 213-220.

Reed L, Glasper A, de Wet C, Bearn J, Gossop M (2007). Comparison of buprenorphine and methadone in the treatment of opiate withdrawal: possible advantages of buprenorphine for the treatment of opiate-Benzodiazepine codependent patients? Clinical Psychopharmacology: 27(2), 188 – 192.

Petursson H, Lader M (1984) Dependence on tranquillizers. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sees KL, Delucchi KL, Masson C, Rosen A, Clark HW, Robillard H, Banys P, Hall SM (2004) Methadone maintenance vs 180-day psychosocially enriched detoxification for treatment of opioid dependence: a randomized controlled trial. 99(6), 718-726. Stine SM, Greenwald MK, Kosten TR (2003) Ultra rapid opiate detoxification: pharmacologic therapies for opioid addiction.. In: A. Graham and T. Schultz eds. Principles of Addiction A. Graham and T. Schultz. Maryland: American Society of Addiction Medicine, 668-669.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) (1995) Detoxification from alcohol and other drugs. Rockville, Md.: SAMHSA

UK. Department of Health (2007). Drug misuse and dependence: UK guidelines on clinical management. London: Department of Health.

Wilson, BK, Elms RR, Thomson CP (1975) Outpatient vs hospital methadone detoxification: an experimental comparison. International Journal of Addiction: 10(1), 13-21.

World Health Organisation (WHO) (2006). Lexicon of alcohol and drug terms published by the World Health Organisation. Available at http: //www.who.int/substance-abuse/terminology/who-lexicon/en/

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|