11 Psychosocial interventions

| Reports - Models of Good Practice in Drug Treatment |

Drug Abuse

11 Psychosocial interventions

Psychosocial, inpatient and residential treatments – guideline

Guidelines for treatment improvement

Moretreat-project

SORAD Stockholm Sveden

October 2008

The content of this report does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the European Commission. Neither the Commission nor anyone acting on its behalf shall be liable for any use made of the information in this publication.

Content

1 Introduction Psychosocial treatment

1.1 Aims and objectives

2 Research evidence base

2.1 Counselling

2.2 Cognitive behavioural therapy

2.3 Community Reinforcement Approach

2.4 Group therapy

2.5 Motivational interviewing

2.6 Relapse prevention therapy

2.7 Contingency management

2.8 The 12 step programme

2.9 Case-Management

2.10 Inpatient and residential treatment

2.11 Key findings

3 Recommendations

3.1 Counselling

3.2 Cognitive behavioural therapy

3.3 Community reinforcement approach

3.4 Group therapy

3.5 Motivational interviewing

3.6 Relapse prevention therapy

3.7 Contingency management

3.8 The 12 step programme

3.9 Case management

3.10 Inpatient and residential treatment

4 Final notes

References

1 Introduction Psychosocial treatment

Psychosocial treatment is an expanding field in the context of treatment of drug dependence. There is no single method, but a set of different forms of psychosocial interventions offered to people. There are a vast number of psychosocial methods available for drug dependence, even if the methods on one hand might look very different; they have some things in common:

• Focus on the misuse.

• The treatment is structured around the patient/treatment.

• Sufficient amount of time for treatment.

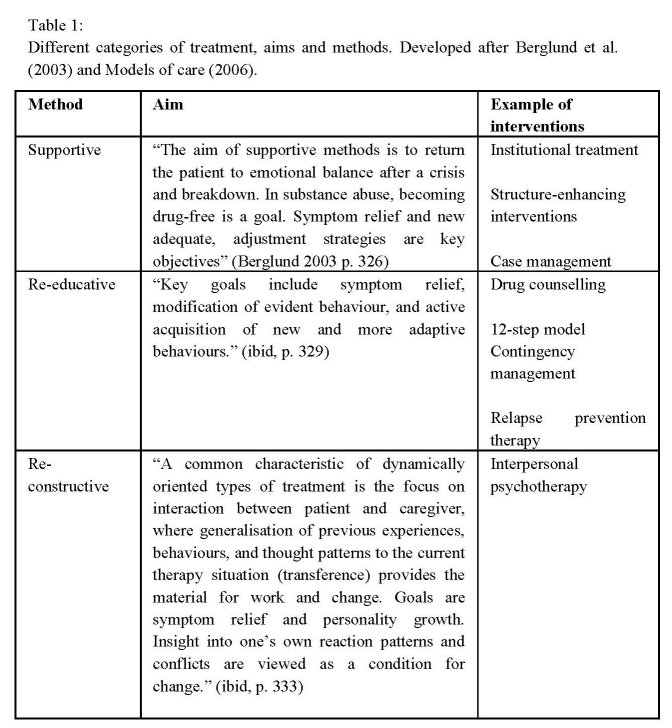

• Focus on both the misuse and the psychological factors (Fridell 2007). The psychosocial methods can be divided into supportive methods, re-educative methods and re-constructive or psychodynamic oriented methods (Berglund et al. 2001

• 12). Table 1 shows an overview of different methods referred to as psychosocial treatment. A great deal of the material in this overview comes from the meta analysis the Swedish council of technology assessment in health care (SBU 2001, Berglund et al. 2001) which was an initiative to establish an evidence-based practice platform. However, this study has been subject for critique. For example Pedersen (2005) point out that there are problems in the comparison and in the different interventions categories. At the same time the SBU-study is an important pioneering piece of work in a relative new field of research.

Structured psychosocial interventions should according to the Models of care (2006, p. 43) be:

• Clearly defined.

• Evidence based.

• Delivered as part of clients care plan.

• Normally time limited.

• Delivered by a practitioner.

• Should be competent and adequate training.

• Should receive regular clinical supervision (Irving et al 1999).

The treatment should be identified within a care-plan and can be delivered individually or in group sessions. Due to the fact that the treatments are different in traditions, design, staff and outcome, it is difficult to compare them. What is clear is that some form of psychosocial treatment is better than no treatment at all (Berglund et al. 2003). There is no silver-bullet method, no single method is better than any other (Socialstyrelsen 2001).

1.1 Aims and objectives

Psychosocial treatment is not a single method, but includes different forms of therapies. The idea is that the therapist and the client should cooperate. The significance of this cooperation is to avoid direct confrontation and instead base the interaction on trust and understanding. A very important part of the treatment is that the patient should be active and learn about his or her specific situation, through self-exploration and data gathering. This data is a ground for discussion in the sessions with the therapist. The role of the therapist is to share knowledge about different factors that may be important reasons for drug-or alcoholic misuse. The aim is that the client should learn about those reasons and be able to understand why he or she has problems and what to do about it. An important part of the therapy is for the problematic drug users to become more aware of the negative consequences of the dependence and instead develop a larger self-control, become calmer and more active when it comes to choices of life. Different forms of therapy includes role playing and concrete practices when it comes to different social areas, such as not being late to appointments, buying food and contact with the social governments. Inpatient drug and alcohol misuses treatment programmes are designed for drug and alcohol misuse disorder (Models of care 2006 p. 90). The aim is to support the addict both in order get free from his/her drug use, but also help with creating a social context (Berglund et al. 2001). The residential treatment takes place in many various settings and includes both long-term and short-term placements in residential treatment facilities, prisons and other criminal justice facilities, involuntary institutions and halfway houses. In the Models of care, Residential treatment is described as follows: “Residential rehabilitation programmes aim to engender and maintain abstinence in a residential setting. It is recognised that people with complex problems related to drug misuse may require respite and an intense programme of support and care which cannot realistically be delivered in a community or outpatient setting.” (Models of care p. 99).

2 Research evidence base

Previous research shows that that one way to succeed is to combine psychosocial treatment with some substitution maintenance treatment (Berglund et al. 2001). In this section we will discuss different psychosocial treatments and inpatient/residential treatment.

2.1 Counselling

The most common form of psychosocial treatment is different forms of care-planned counselling, and that is defined as: ‘…formal structured counselling approaches with assessment, clearly defined treatment, plans and treatment goals and regular reviews, as opposed to advise and information, drop-in support and informal key-working.’ (Models of Care 2002).

2.2 Cognitive behavioural therapy

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) focuses on the interplay between the individual and the environment, and on solving problems. In the US Department of Health and Human services, brief interventions and brief therapies for substance abuse (TIP 34) it is stated that CBT represents: “(…) the integration of principles derived from behavioural theory, cognitive social learning theory, and cognitive therapy, and it provides the basis for a more inclusive and comprehensive approach towards to treating substance abuse disorders” (Lawton Barry 1999, p. xxi). Previous research has shown that CBT has especially good outcome on cocaine misuse treatment used in a long term perspective, and that CBT to be more effective than other forms of psychosocial therapy when treating patients with more severe dependence (Schulte et al. 2007). Berglund states that only psycho therapy (cognitive, family and dynamic therapy) shows good results for up to a year of treatment when it comes to treatment of opium addiction in combination with methadone treatment. But when it comes to randomised controlled studies and cocaine abuse cognitive therapy shows no significant effects other than higher retention. Over all, Berglund states, it is the psycho therapies that show the highest retention. In NICE they write: “Evidence-based psychological treatments (in particular, cognitive behavioural therapy) should be considered for the treatment of comorbid depression and anxiety disorders in line with existing NICE guidance for people who misuse cannabis or stimulants, and for those who have achieved abstinence or are stabilised on opioid maintenance treatment.” (NICE, p. 14). They also write that: “Cognitive behavioural therapy and psychodynamic therapy focused on the treatment of drug misuse should not be offered routinely to people presenting for treatment of cannabis or stimulant misuse or those receiving opioid maintenance treatment.” (p. 14). The duration is flexible. Schulte et al (2007) write: “CBT has especially good outcomes in the long-term view and for different patient groups and especially for those with more severe dependence symptoms or co-morbid mental illness. It has been conducted for cocaine dependence in a number of studies with good results, and also for other substances.” (Schulte et al. 2007, p. 88). In the Socialstyrelsen (2007) it is pointed out that psychosocial treatment per se have effects on drug dependence, but no individual form of psychosocial treatment is superior to another. Family therapy dynamic forms of therapy and CBT are more effective when it comes to continued participation in treatment (Socialstyrelsen 2007, p. 138).

2.3 Community Reinforcement Approach

The Community Reinforcement Approach (CRA) aims to provide opportunities for the illicit drug user to re-structure his or her life situation. The approach aims to eliminate positive feelings of drug use and instead increase the positive attitude towards a life free from drug dependence. In many ways CRA is similar to Motivational Interviewing (MI) in that both therapies tries to enhance the clients will for change. There should be clear goals with living a drug free life, normally patient’s signs a “contract” with the care giver, saying that for a time being, a week, a month -that he or she will not use illicit drugs. CRA is suitable for both residential and out patient treatment, but due to the attempt to affect the client’s surroundings and that the patient then can stay in a familiar surrounding. CRA is mainly used as a method mainly to treat cocaine abuse. (Berglund et al. 2003). “Community reinforcement and family training is a manualised treatment programme that includes training in domestic violence precautions, motivational strategies, positive reinforcement training for carers and their significant other, and communication training. However, the primary aim of the treatment appears to be encouraging the person who misuses drugs to enter treatment. This intervention consists of up to five sessions.” (NICE, p. 202). Flexible settings, often in inpatient programmes and in combination with vouchers, but also in outpatient treatment contexts (Azarien, et al. 1982).

2.4 Group therapy

Group therapy is a form of counselling where one or several therapists treat groups of clients together as a group. Examples of treatments that effectively can be carried out in groups are cognitive behavioural therapy or interpersonal therapy. It draws on a combination of different theories (NHS 2002). Studies have found that well-structured 12 step therapy and well-structured cognitive behavioural therapy both produce equal outcomes and are preferred in routine clinical care. An important part is the degree of interactive acquisition, i.e. how well the individuals in the group take ownership of the problem. Since all members in the group are in a similar situation it might be easier to discuss the problems and get social support (NHS, 2002). At the same time the drug addicts’ problems may be hard to handle also in a group discussion. Group therapy has showed to be particularly effective when it comes to treating depression (McDermut W et al. 2001).

2.5 Motivational interviewing

Motivational interviewing (MI) was developed by the clinical psychologists Miller and Rollnick (2003). Motivations can be seen in relation to something or someone. It may not be something that a person lacks or have, but is changeable and flexible and can be influenced. It can change rapidly and is very affected by the state of mind of the person; abstinence can affect an individual’s motivation. The starting point must be the patient’s own experiences and emotions. Care givers must try to understand the logical reactions, based on previous experiences, that the patient makes, and from there point out the difference in the experienced situation and how the patient would like it to be. MI states very clearly that a week motivation is not to regard as lack of motivation, motivation is changeable, not a personal trait. Motivational Interviewing (MI) is often used as a brief intervention. It focuses on enhancing patients’ motivation to change behaviour. MI is both guiding and focused of the patient. The main idea is that the therapist should use the users’ feelings for the drug use as a starting point in the therapy. He or she should be supportive and optimistic regarding the chances of success (Socialstyrelsen, p. 14). The method is often used together with medical treatment, such as Subutex. The time of treatment is rather short and should be limited in time. (Socialstyrelsen, p. 15). In a methadone study, Saunders investigated MI’s effect as a compliment in treatment. Among the heroine abusers that received MI, reported fewer drug related problems, fewer relapse and stayed longer in the methadone programme. According to Schulte et al (2007) MI has “especially good outcomes for patients with lower initial motivation than for those with higher initial motivation” (p. 91). The method shows good results for cannabis use and heroin use. They conclude that there are moderate evidence that.

2.6 Relapse prevention therapy

Relapse prevention therapy (RPT) focuses on different ways to handle breakdowns when the patients are trying to change their behaviour. It can be both a treatment programme for use following the treatment of additive behaviours and used as standalone treatment programme. RPT aims to provide users with self-control techniques in order to identify risks and cope with changes in their behaviour to avoid relapse. RPT is a combination of behavioural and cognitive interventions and emphasises self-management (Parks and Marlatt 2000). Carroll et al. (1991) found in a study evidence that RPT helped users avoid relapse after finished treatment. This was most significant for cocaine abusers. After 6 -12 month the cocaine abusers which participated in the study and got a combination of relapse therapy and CBT where still drug free.

Teaching clients strategies to: understand relapse as a process, identify and cope effectively with high-risk situations, cope with urges and craving, implement damage control procedures during a lapse to minimize its negative consequences, stay engaged in treatment even after a relapse, and learn how to create a more balanced lifestyle.

2.7 Contingency management

Contingency management focuses on changing a learnt behaviour into a new one. This is done by different means of rewarding good behaviour, for example through shopping vouchers. In NICE Clinical guidelines they write: “Drug services should introduce contingency management programmes (…) to deduce illicit drug use and/or promote: Engagement with services for people receiving methadone maintenance treatment Abstinence and/or engagement with services for people who primarily misuse stimulants” (NICE 2007, p.10).

2.8 The 12 step programme

The 12 step programme is based on cognitive theories and traditions. The 12 step programme has its traditions in the US, and has its base in AA and NA group meetings. The 12 step programme is per say no method, since it is based on the individuals own personal experiences and not on scientific research. The 12 step programme has a strong position in both residential and outpatient care and is used as a control condition for other treatment interventions. (Berglund et al. 2003)

2.9 Case-Management

Supportive methods aim to let the patient find an emotional balance and a drug-free life. Methods referred to as supportive is counselling, relaxing, acupuncture, environmental therapeutic methods, case-management and pharmacological forms of treatment. For the patient the goal is to find new life strategies and to ease the symptoms. CMSA defines case management as “a collaborative process of assessment, planning, facilitation and advocacy for options and services to meet an individual's health needs through communication and available resources to promote quality cost-effective outcomes. “ (CMSA 2008). Usually case-management are divided into four models (Vanderplachen et al., p. 138);

• Generalist or Standard Case Management -close interaction between case manager and client.

• Assertive community treatment (ACT) /intensive case management – the aim is to work as a team of case.

• Clinical models – combines case management and clinical actives.

• Strength based case management – focusing on the clients strengths and the use of informal help networks area of expertise in order to get an enhanced possibility to give the client the right support.

Case management has been used in drug treatment since the beginning of the 1980s. It is based on the recognition that the misuses often have significant problems in additions to their drug misuse. Case management is most often used as a treatment in the USA and Canada, but there have been European programmes in Germany, Belgium and the Netherlands. The intention with case management can be described as providing continuous supportive care when it comes to contact with other helping resources (Wanderplasshen et al. 2005). Case managements have five core functions:

• Assessment

• Planning

• Linking

• Monitoring

• Advocacy

2.9.1 Outcomes of case management

Earlier studies from Lightfoot et al. (1982), Willenbring, et al. (1991), report positive outcomes of case management. There is ongoing research which model suits which population best (Wanderplasshen et al. 2005).

Generalist or Standard Case Management

Wanderplasshen et al. states that the effects of applying the standard case management model mainly was about “improved treatment participation and retention” (ibid, p. 143). Positive effects reported in uncontrolled studies “could not always be maintained over time.” (ibid, p.144). They conclude: “Some evidence is available concerning the effectiveness of generalist case management for enhancing treatment participation and retention. Generalist case management might be appropriate for this purpose among several substance abusing populations, but needs to combined over time with other interventions or with more intensive or specialised models of case management in order to affect clients’ psychosocial functioning.” (ibid p. 144).

Assertive community treatment (ACT) /intensive case management

Wanderplasshen et al. found nine randomized and controlled trials. Five of those showed significant differential effects of intensive case managements ACT when compared with other interventions (p. 142). They point out that there are few repetitions of results between the studies. They write: “Intensive case management appears to be most effective for extremely problematic substance abusers, such as chronic public inebriates and dually diagnosed individuals, since this intervention helps to stabilize and improve psychosocial functioning and to reduce utilization of expensive inpatient services.” (ibid. p.142).

In uncontrolled studies there is evidence that intensive case management is effective, something not present in controlled studies due to the lack of repetition of results between studies.

Clinical Case Management

Wanderplasshen et al. writes that since there are no randomized and controlled trials that have assessed the effectiveness of the Clinical Case Management there is no evidence. (ibid, p. 144).

Strength-based case management

According to Wanderplasshen et al. (ibid) little evidence is available when it comes to the effectiveness strength-based case management. They write: “We conclude that some evidence exists for the effectiveness of strengths-based case management to improve employment functioning and treatment participation and retention. Given its role in addressing denial and resistance, its appreciation among clients and its potential positive effects, a strengths-perspective on case management might help to enhance treatment participation and retention among persons with little or no motivations for change.” (ibid, p. 143).

2.10 Inpatient and residential treatment

It can be very difficult to perform methodological randomized controlled studies within an institution or organisation. The main reason is that, even if the method used is similar between the organisations and institutions, the result may vary due to various and different settings such as organisation structure, management and information. For example Fridell (1996) argues that the organisation of the care giver affects the actual care. Although we are discussing the same kind of intervention it differs a great deal from country to country, and also within different countries. This makes it hard to compare studies made in different countries and draw conclusions to create an evidence base. American studies have reported that the outcome of long-term residential rehabilitation programmes is in relation to how long the patient stayed in the programme. Also, long-term residential programmes have shown to be cost-effective when it comes to treating problematic highly criminal clients. As well as short-term and other less intense programmes are better adapted for less problematic clients. (Models of Care, 2002) The Models of Care reports that there is limited evidence that TC is superior to other inpatient/residential treatments. When compared to community residence, there where no different evidence concerning treatment completion, but the day TC residential group had better results in attrition and abstinence rates. (Models of Care 2002 p 105). The difference between inpatient and residential treatment lies in where it takes place and how it is organized. Inpatient treatment takes place in a controlled environment, for example in a hospital. The patient stays at the hospital during the whole treatment period. Residential treatment, on the other side, means that the misuser participates in a programme providing both specialised non-hospital based and general interdisciplinary services twenty-four hours a day, all week long. In the residential environment the misuser receives services from staff. In the UK most residential programmes require that the patient is drug-free on entry but some residential programmes offers detoxification facilities. (Models of Care 2002) In general there are three types of residential treatment, therapeutic communities, 12-step programmes and various forms of general Christian houses. In return, the programmes within the treatment can be either long-term or short-term treatment. (ibid) According to NIDA therapeutic communities are: drug free programmes in a residential setting where the treatment settings levels are increased due to the person’s personal involvement (NIDA 1988). Group pressure and peer influence is used to help the individuals to re-learn social norms and skills. TC’s are highly structured programmes where the participants participate in the residential treatment for a longer time, usually 6 to 12 months. The size of a residential treatment facility can vary in size. Usually the clients prefer to relocate for treatment and travel away from their familiar surroundings. (Models of Care 2002).

2.10.1 Short-term residential rehabilitation

Short-term residential rehabilitation has a planned duration for six to 12 weeks. The patient usually takes part of a medically supervised withdrawal as a first step.

2.10.2 Long-term residential rehabilitation

The long-termed residential rehabilitation does not normally include a medically supervised withdrawal as a first treatment face. The duration for the programmes varies a great deal. But according to the Models of Care the median time in treatment is 10 weeks. (Models of Care) Normally long-term residential treatment is an ongoing process 24 hours a day for 12 weeks and longer. The most well known form of long-term residential treatment is the therapeutic communities (TC) but there are also other forms of treatment.

2.10.2 Halfway houses

Halfway houses are also referred to as low-intensity rehabilitation. This is often the last step of a long-term residential treatment. Halfway houses are normally linked to the original programme, the clients are supposed to live drug free and the halfway house can be seen as a preparation for a life after treatment. The duration of halfway houses varies a great deal. (Models of Care 2002).

2.10.4 Therapeutic communities

A therapeutic community (TC) is not a method, but rather a model for how to organize treatment of drug and alcohol misuse. The aim is to change the conditions for treatment through changing the abusers norms and values. According to Models of Care they are “based on democratic and de-institutionalised principles and aim at abstinence”. TC’s normally is group based and offer various forms of therapy. (Models of Care 2002).

2.10.5 Compulsary/involuntary treatment

NIDA, the National Institute on Drug Abuse in the USA, defines compulsory care as: Compulsory treatment may be defined as activities that increase the likelihood that drug abusers will enter and remain in treatment, change their behaviour in a socially desirable way, and sustain that change. (NIDA 1988 p. 1). In general there are three different kind of reasons how a person end up in compulsory care:

• The Criminal justice system: a person is, without consent, sentenced to compulsory treatment in a treatment facility due to drug related crime. Or:

• A person is sentenced to treatment within a prison without consent.

• If a person who is undergoing voluntary treatment demands compulsory treatment if he/she tries to end treatment in advance. (LVM-utredningen 2004).

Compulsory care can be problematic. The clients/patients can have great difficulties adjusting in the settlement. (Kinnunen A 1994) It is very difficult to talk about results when it comes to compulsory treatment. There are no randomised studies about the effect of compulsory treatment available. A study made by Gerdner, where 47 persons who had had compulsory treatment under the period 1998-2000, showed no positive or negative effect of the treatment (Gerdner A 2000).

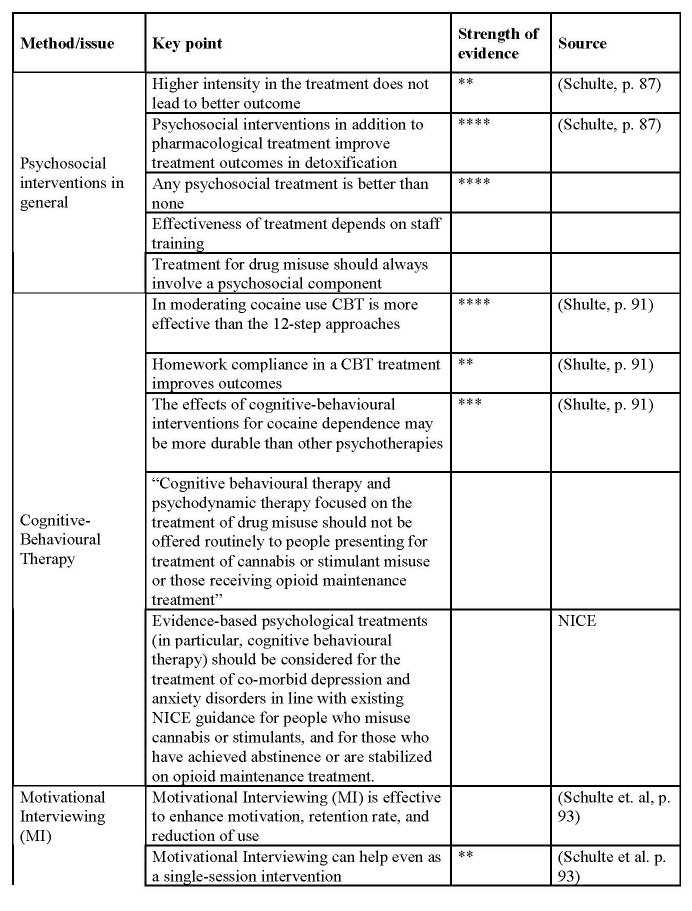

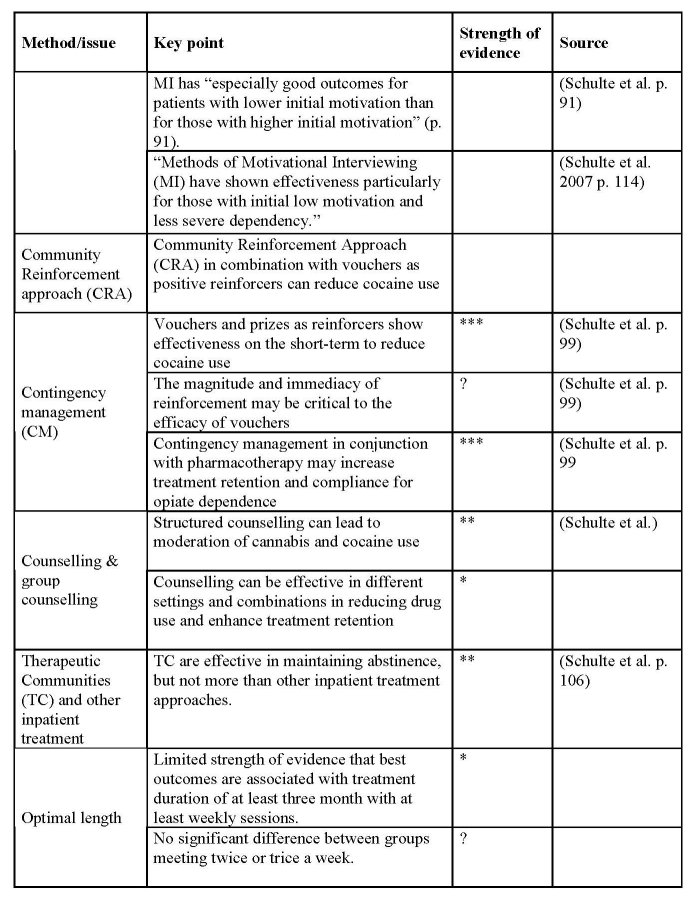

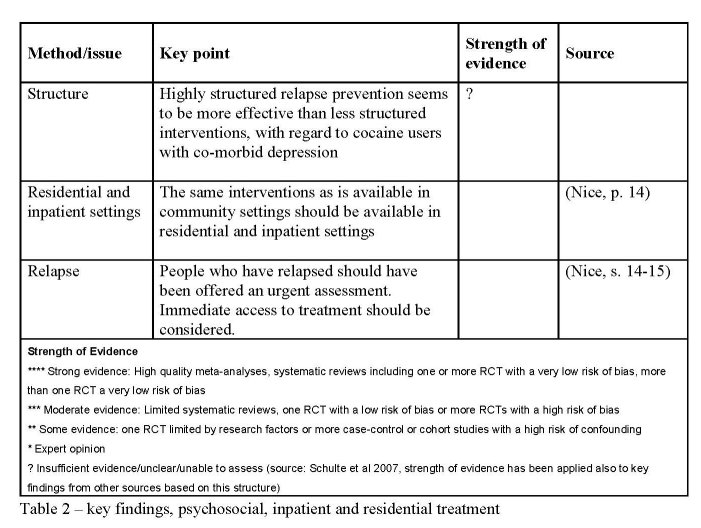

2.11 Key findings

In the fact sheet below key findings are presented. There are several guides available covering the research area of psychosocial, inpatient and residential treatment. The main source of information for this guideline comes from NICE, Berglund and Schulte et al (2007) and NHS.

3 Recommendations

An important finding is that psychosocial treatment per se have effects on drug dependence, but no individual form of psychosocial treatment is superior to another (see e.g. Socialstyrelsen 2007; Shulte et al. 2006; Berglund, 2003). In the following we will walk through the different methods and see what recommendations are related to access to care, pathway, other structural aspects and management aspects.

3.1 Counselling

Counselling can effectively be used in different settings and combinations in reducing drug use and enhance treatment retention (Schulte et al. 2007). Structured counselling can lead to moderation of cannabis and cocaine use (Schulte et al. 2007).

3.2 Cognitive behavioural therapy

CBT can be provided in many different settings e.g. privately founded care, through and within the primary care system, inpatient/residential care, etc. Treatment for drug misuse should always involve a psychosocial component (Schulte et al. 2007, p. 91)

Homework compliance can be used in a CBT to improve outcomes (Schulte et al. 2007, p. 91). Psychosocial treatment has effects on drug dependence, but no individual form of psychosocial treatment is superior to another. Family therapy dynamic forms of therapy and CBT are more effective when it comes to continued participation in treatment (Socialstyrelsen, 2007, p. 138).

3.3 Community reinforcement approach

The community reinforcement approach can be carried out in inpatient programmes and in combination with vouchers, but also in outpatient treatment contexts. Community Reinforcement Approach (CRA) in combination with vouchers as positive reinforcers can reduce cocaine use.

3.4 Group therapy

It is important that the individuals in the group take ownership of the problem. If all members in the group are in a similar situation it might be easier to discuss the problems and get social support (NHS 2002). Group therapy is particularly effective when it comes to treating depression (McDermut W et al. 2001)

3.5 Motivational interviewing

Care givers must try to understand the logical reactions, based on previous experiences, that the patient makes, and from there point out the difference in the experienced situation and how the patient would like it to be. Methods of Motivational Interviewing (MI) have shown effectiveness particularly for those with initial low motivation and less severe dependency.” (Schulte et al. 2007, p. 114). Motivational Interviewing (MI) can be used to effectively enhance motivation, retention rate, and reduction of use. Motivational Interviewing can help even as a single-session intervention.

3.6 Relapse prevention therapy

Highly structured relapse prevention seems to be more effective than less structured interventions, with regard to cocaine users with co-morbid depression. People who have relapsed should be offered an urgent assessment. Immediate access to treatment should be considered.

3.7 Contingency management

The staff needs to be trained in “appropriate near-patient testing methods and in the delivery of contingency management” (NICE 2007). Vouchers and prizes as reinforcers can be used on the short-term to reduce cocaine use. The magnitude and immediacy of reinforcement may be critical to the efficacy of vouchers. Contingency management in conjunction with pharmacotherapy may increase treatment retention and compliance for opiate dependence (Schulte et al., p. 99).

3.8 The 12 step programme

The 12 step programme can be used in both residential and outpatient care. The 12 step programme can be used as a control condition for other treatment interventions. (Berglund et al. 2003).

3.9 Case management

Generalist case management might be appropriate for enhancing treatment participation and retention. It can be combined with other interventions or with more intensive or specialised models of case management (Wanderplasshen et al. 2005, p. 144). Intensive case management is most effective for extremely problematic substance abusers. It is also effective for treatment of chronic public inebriates and dual diagnosed individuals (ibid. p.142). A strengths-perspective on case management might help to enhance treatment participation and retention among persons with little or no motivations for change (ibid, p. 143).

3.10 Inpatient and residential treatment

The same interventions as is available in community settings should be available in residental and inpatient settings. All the different psychosocial treatments should be carried out by professional staff. Short-term and other less intense programmes are better adapted for less problematic clients. (Models of Care 2002).

4 Final notes

Many of the studies in this chapter comes from the US, Canada and England. Very few of them comes from the rest of Europe. It can be hazardous to take a method from the US and use it in societies, which have other conditions, such as in Europe (Uffe Pedersen 2005). There is no single best method, and the research discussed in this overview many times point this out.

The few studies included in this guideline indicates that there is a scientific support for the use of psychosocial interventions. However, there are few studies and it is very difficult to draw any firm conclusion about which method is superior to another. It is indicated that all the different psychosocial treatments should be provided by professional staff. At the same time they are very flexible in their structure and can also to some degree be combined. One such combination is the use of methadone or subutex and psychosocial interventions. Further studies about the effects of psychosocial treatment, not at least based on European material, are recommended.

References

Andreassen, Tore (2003). Institutionsbehandling av ungdomar : vad säger forskningen?.

Stockholm: Gothia

Azrien, 1982

Berglund, Mats, Thelander, Sten & Jonsson, Egon (red.) (2003). Treating alcohol and

drug abuse : an evidence based review. Weinheim: Wiley-VC

Bergmark Anders (2005) Evidence Based Practice - More Control or More Uncertainity

in Pedersen, Mads Uffe, Segraeus, Vera & Hellman, Matilda (red.) (2005). Evidence

based practice? : Challenges in substance abuse treatment. Helsinki: NAD pp.27-36

Carroll, K. & Rouansaville, B & Keller, D. (1991) Relapse prevention strategies for the

treatment of cocaine abuse. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 17 (3),

249-265

Edman, Johan & Stenius, Kerstin (red.) (2007). On the margins : Nordic alcohol and

drug treatment 1885-2007. Helsinki: Nordic Centre for Alcohol and Drug Research

(NAD)

Kinnunen Aarne. (1994) Den bristande motivationen. En litteraturstudie över

tvångsvård av rusmedelsmissbrukae i de nordiska länderna. Missbruk och

tvångsvård. Helsingfors: Nordiska nämnden för alkohol- och drogforskning (NAD)

Klingemann, H and Takala, J. P. and Hunt, G. (1992) Cure, care or control. Alcoholism

treatment in sixteen countries. State university of New York, Albany

Fridell, Mats (1990). Kvalitetsstyrning i psykiatrisk narkomanvård : effekter på personal

och patienter. Diss. Lund : Univ.

Gerdner Arne (2004) LVM-vårdens genomförande, utfall och effekt- en kontrollerad

registerstudie i Jämtland. LVM-utredningens bilagedel Forskningsrapporter SOU

2004:3

Järvinen, Margaretha, Skretting, Astrid & Hübner, Lena (red.) (1994). Missbruk och

tvångsvård. Helsingfors: Nordiska nämnden för alkohol- och drogforskning (NAD)

Lehto, J (1994) Involuntary treatment of people with substance related problems in the

Nordic Countries, in Järvinen, M. and Skretting, A. (eds) Missbruk och Tvångsvård,

Nordiska nämnden för alcohol och drogforskning (NAD), Hakapaino Oy,

Helsingfors, 1994

Andreassen, T. (2003). Institutionsbehandling av ungdomar : vad säger forskningen?

(Residental reatment of youths : research overview). Statens institutionsstyrelse,

Stockholm: Gothia

Berglund, Mats, Thelander, Sten & Jonsson, Egon (red.) (2003). Treating alcohol and

drug abuse : an evidence based review. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH

Schulte, B. Thane, K., Rehm, J. Uchtenhagen, A., Stöver, H., Degkwitz, P, Reimer, J.

and Haasen, C. (2007) Review of the efficacy of drug treatment interventions in

Europe, University of Hamburg, Hamburg

Lawton Barry, K 1999 Brief interventions and brief therapies for substance abuse,

Treatment improvement protocol (TIP) series: 34

LVM-utredningen (2004). Forskningsrapporter : bilagedel : betänkande. Stockholm:

Fritzes offentliga publikationer

Asmussen V og Kolind T (2005) Udvidet psykosocial indsats i metadonbehandling -

Resultater fra en kvalitativ evaluering af fire metadonforsögsprojekter Center for

rusmiddelforskning

Hesse M (2006) Psykosociala interventioner i stoffri behandling for opiatmissbruk

Nordisk alkohol & Narkotikatidskrift 6

Principer för behandling av drogberoende : en forskningsbaserad vägledning. (2004).

Stockholm: Statens institutionsstyr. (SiS)

Pedersen, Mads Uffe, Segraeus, Vera & Hellman, Matilda (red.) (2005). Evidence based

practice? : challenges in substance abuse treatment. Helsinki: NAD

Miller, William R. & Rollnick, Stephen (2003). Motiverande samtal : att hjälpa

människor till förändring. Norrköping: Kriminalvårdens förlag.

B. Schulte, Thane, K, Rehm, J, Uchtenhagen, A., Stöver, H., Degkwitz, P., Reimer, J. &

Haasen, C. (2007) Review of the efficacy of drug treatment interventions in Europe,

ZIS

McDermut W et al (2001) The Efficacy of Group Psychotherapy for Depression: A

Meta-analysis and Review of the Empirical Research. Clinical Psychology: Science

and Practice, 8, 98-116

Dennis, M et al (2003). The Cannabis Youth Treatment (CYT) Study: Main Findings

from Two Randomized Trials. Accepterad (januari 2004) för publicering i

JOURNAL OF SUBSTANCE ABUSE TREATMENT

Nationella riktlinjer för missbruks- och beroendevård vägledning för socialtjänstens och

hälso- och sjukvårdens verksamhet för personer med missbruks- och

beroendeproblem. (2007). Stockholm: Socialstyrelsen. Available on Internet:

Irvin, J. E., Bowers, C.A., Dunn, M.E., and Wang, M.C. (1999). Efficacy of relapse

prevention: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology.

Parks, G, & Marlatt, A. (2000) Relapse Prevention Therapy: A Cognitive-Behavioral

Approach The National Psychologist September/October, (9, 5)

Pedersen, Mads Uffe, Segraeus, Vera & Hellman, Matilda (red.) (2005). Evidence based

practice? : challenges in substance abuse treatment. Helsinki: NAD

Mads Uffe, Pedersen (2005) Drug-Free treatment of Substance Misusers: Where are we

now, Whwerw are we heading? in Pedersen, Mads Uffe, Segraeus, Vera & Hellman,

Matilda (red.) (2005). Evidence based practice? : Challenges in substance abuse

treatment. Helsinki: NAD pp. 11-28

Woutter, Wanderplasshen, Wolf, Judith, Rapp, Richard C. & Broekaert, Eric (2005) Is

Case Management an Effective and Evidence Based Intervention for Helping

Substance Abusing Populations? in Pedersen, Mads Uffe, Segraeus, Vera &

Hellman, Matilda (red.) (2005). Evidence based practice? : Challenges in substance

abuse treatment. Helsinki: NAD pp. 137-158.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|