Chapter 4 ENACTING DECRIMINALIZATION: A DRAFTER'S GUIDE

| Books - Marijuana Use and Criminal Sanctions |

Drug Abuse

Chapter 4 ENACTING DECRIMINALIZATION: A DRAFTER'S GUIDE*

* This chapter is a revised and updated version of papers originally prepared for the National Governor's Conference in connection with an LEAA-sponsored study of recent revisions of the marijuana laws and later published in 11 Mott. J. OF LAW REFORM 3 (1977).

As I mentioned earlier, the National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse recommended decriminalization of possession of marijuana for personal use in 1972.' Since that time, ten states2 have enacted some variant of the Commission's recommendation, and similar proposals are currently being considered in most of the remaining states and in the Congress.3 This chapter is designed to survey and discuss the numerous issues of policy and law which must be confronted in evaluating legislative proposals to implement the Commission's recommendation.

The chapter does not discuss the arguments in favor of decriminalization, a matter which the author' and others5 have covered elsewhere. Nor does it consider the even more difficult questions involved in a legislative decision to legalize the drug and authorize its distribution for non-medical uses. Previously-noted international obligations, federal law and current political realities preclude enactment of a "regulatory" approach toward the availability of marijuana—including any variant of the so-called alcohol model—in the immediate future. Although a state could conceivably repeal its laws against cultivation and distribution of marijuana, leaving only the federal prohibitions in effect, such an overt departure from the prevailing national sentiment seems unlikely, at least in the foreseeable future. One must assume, for present purposes, that commercial activities will remain prohibited by state law.6

Within these contours, the range of public policy choices has both statutory and administrative dimensions. The statutory issues involve the appropriate penalty structure for possession of marijuana for personal use and other consumption-related behavior. Possible sanctions include criminal penalties of varying severity as well as several forms of decriminalization, including civil sanctions. Although administrative choices by police and prosecutors are extremely important and should not be overlooked by reformers,7 this chapter will focus only on legislative options, providing a drafter's guide for lawmakers who have concluded that the traditional criminal penalties for consumption-related behavior should be substantially modified.

The term decriminalization has been used to describe these legislative reforms, but, because the operational meaning of the criminal sanction is itself ambiguous, neither legislators nor criminal justice personnel share a common conception of what decriminalization means. In this chapter, the term will be employed to refer to a threshold concept rather than a definitional one : decriminalization refers to any statutory scheme under which the least serious marijuana-related behavior is not punishable by incarceration. Incarceration is a useful threshold device for several reasons : the elimination of the possibility of imprisonment and its attendant social stigma reflects a significant change in official attitudes toward marijuana offenses ; total confinement is a sanction different in kind as well as in degree from other legal sanctions ; and a lesser sanction suggests or requires less severe and less elaborate application of criminal processes.

Beyond this threshold, two important questions must be addressed. First, legislators must decide what behavior should be decriminalized. Only possession of small amounts? Nonprofit accommodation sales to friends? Cultivation of a few plants in the home? These questions will be addressed in part I.

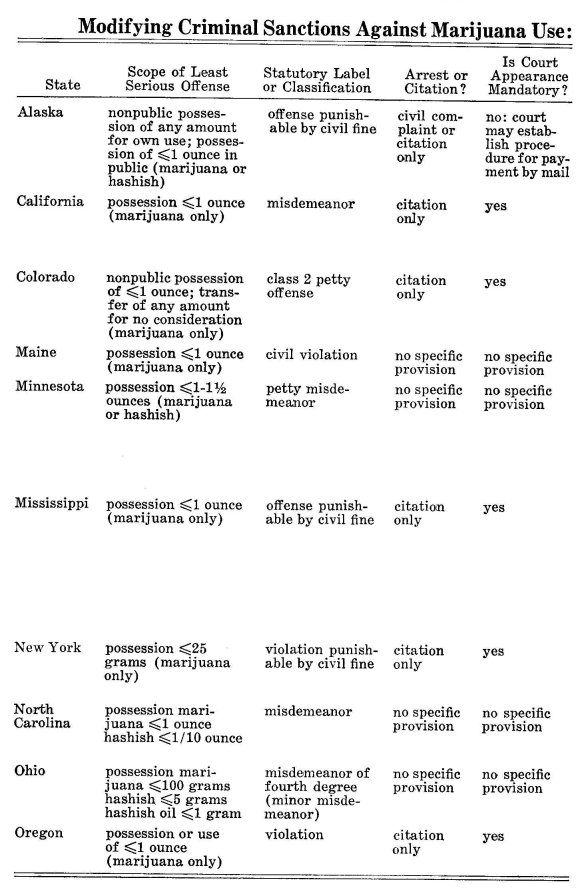

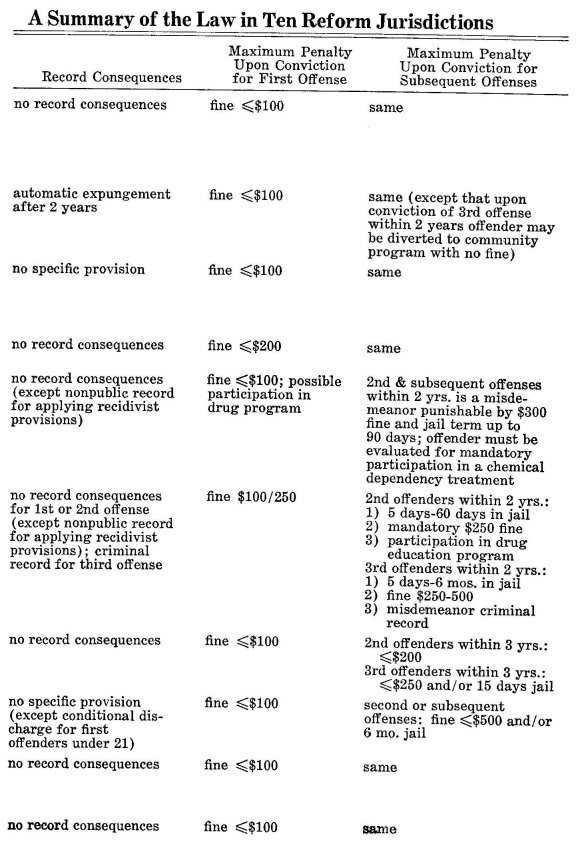

Second, legislators must determine what residual sanctions, if any, should be retained to implement the state's interest in discouraging decriminalized behavior. Conduct that is decriminalized may or may not remain subject to lesser sanctions. In each of the ten states which have thus far enacted decriminalization reforms, least serious marijuana-related behavior is still punishable by a fine. In some of those states the behavior is still labeled a criminal offense, although a person convicted of the offense may have no record. Should the commission of a decriminalized offense be punishable by a monetary penalty or by participation in some educational or counseling program? Should the person be booked and taken into custody after detection of a decriminalized offense? Should such a person be stigmatized by an arrest or conviction record? These questions will be addressed in Parts II, III and IV.

I. DECRIMINALIZED OFFENSES

The scope of decriminalized behavior, and the drafting techniques used to define the residual offenses, will be determined primarily by the purpose of the reform. If, for reasons of fairness, justice, or institutional integrity, the legislature's main goal is to withdraw the criminal sanction from mere consumers of marijuana, the statutes should be revised in a way that most accurately distinguishes between consumption-related activity and commercial activity. On the other hand, if the primary legislative objective is to promote the efficient administration of criminal justice by reducing the burden of processing petty marijuana cases, decriminalization may be restricted to the narrowest range of behavior consistent with this goal.

Drug offenses are usually separately defined for possessory conduct, distributional conduct and production or cultivation. Legislators have traditionally recognized that possessory activity may be indicative either of intended consumption or intended distribution, depending upon the amount possessed and other indicia of intent. Similarly, legislators have been sufficiently aware of the patterns of marijuana use that they have distinguished since the late 1960's between purely commercial activity and gratuitous or non-profit transfers among friends. A similar distinction may be drawn between forms of cultivation, which may range from growing one plant

in a window box to a large-scale agricultural enterprise. This Part will consider the drafting alternatives for defining "decriminalized" or "least serious" marijuana-related behavior with reference to possessory conduct, non-commercial transfers, and non-commercial cultivation.

A. Possessory Conduct

1. Statutory Relationships Between Intent and Amount

Traditionally, the possession offense has been divided into at least two categories : simple possession and possession with intent to sell, (with more severe penalties authorized for the latter category) . A clear legislative trend in recent years has been to dispense with proof of "intent" and to substitute gradations of amount with correspondingly graduated penalties. Thus, in discriminating between less serious and more serious possessory activity, legislatures can utilize two criteria, intent to sell and amount possessed, which can be combined in several different ways.

Under one statutory scheme, the pure intent approach, possession of any amount of marijuana is decriminalized unless the prosecution proves intent to sell. The principal advantage of this approach is that it reflects the essential difference between commercial activity8 and possession for personal consumption. The primary drawback is that the prosecution rarely has any independent evidence of intent to sell, and usually relies entirely on inferences drawn from the amount of marijuana possessed.

Because non-criminal and criminal conduct are difficult to distinguish, the pure intent approach does little to reduce the cost or enhance the fairness of enforcing marijuana prohibitions.9 The user cannot confidently adjust his conduct to avoid criminal sanctions. Criminal justice resources may be unnecessarily squandered if the police cannot recognize the decriminalized offense when they see it, although the promulgation of prosecutorial charging guidelines can solve this problem. In addition, defendants charged with criminal possession are more likely to insist on a trial under the pure intent approach because the prosecutor must prove actual intent, a more difficult task than proving that the amount possessed exceeded a designated quantity. Since the defendant has a greater chance of prevailing under the pure intent approach than under a strict amount approach, the prosecutor will not have as much leverage for plea bargaining.

A variation of the pure intent approach, which shifts the burden of proof to the defendant, may increase the prosecutor's leverage. Under this approach, possession of any amount is presumed to be criminal unless the defendant proves that the possession was solely for personal use." Although the question is unsettled, this approach may be unconstitutional ; it may not satisfy the constitutional requirement that the state prove each element of the crime beyond a reasonable doubt ;11 and there may be an insufficient connection between the proven fact, possession of any amount, and the apparently presumed fact, intent to distribute.12 It may be argued, in response, that since the legislature is constitutionally entitled to classify simple possession of any amount of marijuana as a crime it can, a fortiori, create what is in effect a reduced offense for cases in which the offender can demonstrate his intent to consume. On the other hand, if the legislature has chosen to employ the offenders' purpose as the central element in distinguishing criminal conduct from noncriminal conduct, it may be required to assign the burden of proof in a way which bears some empirical connection to the offenders' actual state of mind. Thus, unless statutory presumptions are based on the amount possessed, the legislature may be constitutionally bound, in effect, to presume intent to consume from the mere fact of possession of any amount of marijuana or not to presume anything at all, defining mere possession without any intent as the offense.

However the constitutional issue is resolved, it is clear that decriminalization of possession only if the violator proves that his intent is to consume will not result in any major change in the operation of the marijuana laws. Not surprisingly, none of the ten states which have thus far adopted decriminalization provisions have employed either version of the pure intent approach."

A second method of drawing the statutory boundaries for possessory activity is to decriminalize possession of less than a specified amount and to retain the criminal penalty for possession of any quantity exceeding that amount, without regard to intent to sell. Nine of the ten states which have decriminalized marijuana have utilized this pure amount approach." The principal advantages of this scheme are fairness and efficiency : defining the offense by the amount possessed permits both possessors and police to know precisely what conduct is criminally prohibited ; moreover, this approach gives the prosecutor greater leverage to plea bargain with those who possess above-the-line amounts. On the other hand, the method may be, at once, over and underinclusive : it may decriminalize the behavior of some sellers who possess amounts below-the-line and may retain criminal penalties for some consumers who possess above-the-line quantities." The respective degrees of over and underinclusion obviously depend upon where the line is drawn.

If a legislature is impressed with the advantages of the pure amount method but wishes to alleviate either the under-inclusion or the overinclusion, it may select a scheme which combines the intent and amount approaches. There are four basic variations on this theme.

The first combined approach errs in the direction of under-inclusion. If the major impetus behind decriminalization is a desire to reduce the administrative costs of processing most petty consumption offenses, then the statutory amount could be relatively small and the law could be drafted to make possession of above-the-line amounts always criminal and possession of below-the-line amounts criminal only if the prosecution proves intent to distribute. In below-the-line cases, however, such a statute will involve the same problems of fairness and cost as the pure intent approach since the seriousness of the possessor's offense is indeterminate at the time of the offense in the absence of definitive prosecutorial guidelines. The main advantage of this combined approach is that police and prosecutors may utilize evidence of intent against dealers who are careful to possess only below-the-line amounts. Also a criminal above-the-line offense will give the prosecutor a plea bargaining tool for persons charged with possession with intent to sell.

A second combined approach errs in the direction of over-inclusion. If the core objective is to ameliorate the unfairness of criminalization of an activity which is engaged in and approved of by a large segment of the populace, a larger statutory amount could be used and possession of below-theline amounts would always be noncriminal while above-the-line possession would be noncriminal unless the prosecution proved intent to distribute.

If the legislature believes that this approach will permit many commercial dealers to avoid prosecution by limiting their possession to below-the-line amounts or will generate too many contested cases due to the prosecutor's reduced leverage, the statute could presume intent to distribute in above-the-line cases, in effect shifting the burden of proving intent to consume to the defendant in such cases. This third variation was adopted by Maine in its decriminalization statute." Although similar statutes have been challenged on constitutional grounds, they have generally been upheld on the theory that the proven fact, the amount possessed, is rationally related to the presumed fact, intent to distribute.'7 However, a Michigan court invalidated a statute which provided that possession of more than two ounces of marijuana raised a presumption of intent to sell based on its finding that the specified amount was inadequate to support the presumption." Again, the constitutional question is a tangled one, and extensive treatment is not warranted here. The soundest position would seem to be that the legislature may employ any amount it chooses as a grading variable, decriminalizing possession of less than that amount; but if it chooses to link the amount with the violator's purpose, making the latter the ultimate issue for grading purposes, then it must assign the burden of proof in a way which bears a reasonable relation to the amount possessed. For example, a statute which decriminalized possession of less than 5 grams but decriminalized possession of more than 5 grams only if the defendant proved intent to consume might be invalid, whereas a similar statute using 4 ounces as the gradient would be clearly constitutional.

A statute combining the intent and amount criteria in this way, when compared with the pure amount approach, has the advantage of providing the possessor with an opportunity to contest the presumed fact of his intent to distribute. The person who possesses marijuana for personal use only, in amounts near the borderline, may be criminally punished if the quantity is slightly in excess of the designated amount. The disadvantage of this approach is that intent to distribute will be a triable issue in every case, even when the police are convinced that the drug was not held solely for personal use ; some retail dealers may thus be able to avoid serious sanctions even if they are detected in possession of small above-the-line quantities. Policymakers wishing to alleviate this problem and still retain the advantage of the combined intent-amount approach could create a "buffer zone." This fourth variation will set two amounts, X and Y, so that possession of less than X will never be a criminal offense, while possession of more than Y will always be a criminal offense. Possession of more than X but less than Y will be criminal only if the prosecution proves intent to sell.19

2. Designating the Amount

If a legislature has decided to decriminalize some marijuana-related behavior and intends to implement that choice by utilizing at least one specific amount, the legislators must also decide what that specific amount will be and whether a distinction should be drawn between different cannabis products.

Defining a statutory amount line is necessarily somewhat arbitrary. It is clear that a person possessing over a kilogram of marijuana is holding it for sale and that one holding less than half an ounce is holding it for his personal use and perhaps that of his friends. Between these extremes, however, there is no single amount for decriminalization which is a priori more appropriate than another.

The precise amount should reflect the legislature's specific goal of decriminalization. If the goal is merely to reduce petty nuisance arrests and to retain the criminal sanction for as much marijuana-related conduct as possible, then a relatively small amount such as one ounce should be chosen. Since 90 to 95 percent of all arrests are for simple possession, and approximately two-thirds of these involved one ounce or less," decriminalizing possession of one ounce or less will significantly reduce enforcement costs. The one ounce amount also conforms to current patterns of retail distribution of marijuana.21 Of the ten states which have decriminalized some marijuana-related behavior, six set the line at one ounce,22 one used 25 grams, an amount slightly less than an ounce," and two others decided on an ounce and a half."

If, on the other hand, legislators want the statutory amount to approximate the distinction between commercial and consumer behavior, one ounce is too low, although available data about use and distribution patterns do not indicate clearly which amount would be more realistic. It has been shown both in free access studies, where marijuana users are kept under observation and told to smoke as much as they wish, and in survey studies, where users are asked how much marijuana they consume, that even a heavy user will not use more than an ounce of marijuana in a week.25 Yet, many persons engaging in strictly consumer activity, including casual, not-for-profit distribution to friends, frequently possess more than one ounce because the drug is usually smoked communally and because many users hold a supply for longer periods than one week. If a legislature wishes to keep users out of the criminal justice system, it should probably draw the line at about four ounces. In Ohio, possession of less than 100 grams, a little more than three and a half ounces, was decriminalized.26

One problem which a higher amount leaves unresolved is that of the commercially-oriented retailer who deals only in amounts of four ounces or less, returning to his secreted supply for frequent replenishment. A buffer-zone statute27 could be used to reach this situation : possession of less than one ounce could be decriminalized while possession of more than four ounces remains a crime and possession of an amount in the "buffer zone" would be a criminal offense if the prosecution proved intent to sell.

3. The Potency Problem

Variability in the potency of marijuana poses an additional problem once the legislature has decided upon an amount. Different parts of the cannabis plant contain the psycho-active substance, delta-nine-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), in different proportions, generally decreasing in the following sequence: resin, flowers and leaves. Almost no THC is contained in the stems, roots or seeds.28 The level of THC also varies among plants depending upon agricultural conditions. For example, Mexican-grown marijuana usually contains 1 percent THC by weight; Colombian or Jamaican marijuana can contain as much as 3 to 5 percent THC; and marijuana grown domestically almost always contains less than 1 percent THC.29 Marijuana refers to a preparation of the flowers, leaves, seeds and small stems. Hashish, on the other hand, generally refers to only the resin and the flowering tops of the plant, and its potency may range from 1 percent to 14 percent THC.

A decriminalization scheme might distinguish between preparations of varying potency in order to deter, more effectively, use of the more potent ones. Two methods for making this distinction have been proposed. The potency approach makes criminal liability entirely dependent upon the percentage of THC contained in the particular preparation. For example, possession of less than four ounces of any cannabis will no longer be a crime if the potency is less than one percent, but possession of any amount containing more than 1 percent THC remains a crime.

The potency approach poses three basic problems : fairness, cost, and inconsistency with the goals of decriminalization. The fairness objection implicates the fundamental requirement of our criminal law that actus mus and mens ma coincide. Unless all consumers purchase the equipment necessary to perform THC assays, a person smoking marijuana cannot know the potency of his supply, and a potency distinction therefore imposes the criminal sanction on one who could not have known he was committing a crime.30

Implementing a potency approach would also be costly for the state because each police department would be required to equip their chemical laboratories for THC assays.31 Scientists at the National Institute on Drug Abuse claim that the cost would be prohibitive even though it is now technologically feasible to assay every compound seized.32

The most serious objection to the potency approach is that it could undermine the benefits of decriminalization. Since any marijuana sample could contain an excessive percentage of THC, the police might be directed to detain all persons possessing marijuana pending chemical analysis. This could increase rather than reduce the expenditure of scarce police resources in enforcing marijuana laws. Further, the potency approach does not distinguish the commercial seller from the consumer and it retains the potential for harassment and selective enforcement which plagues the present system. Finally, the potency distinction may actually be insignificant. The Drug Enforcement Administration has analyzed street samples of marijuana compounds for the last several years, and virtually every sample has fallen within the .5 percent to 1 percent range, with a mean potency of .6 percent.33

Under the second method of distinguishing between samples of different potencies, the form approach, criminal penalties are imposed for the possession of hashish, resin, and flowering tops, but not for the usually less potent marijuana flowers, leaves, seeds, and small stems. There are two problems with the form approach. The first problem is that form is not always correlated with potency. Some weak samples of hashish contain less THC than some strong marijuana compounds.34 While the Drug Enforcement Administration has located hashish samples which contain as much as 14 percent THC, the mean percentage is 2.6 percent, and two-thirds of the preparations analyzed were below this mean percentage. The person possessing weak hashish might successfully claim that a statute which punishes him while permitting a person possessing a more potent marijuana mixture to escape criminal liability is defective under the equal protection clause. Further, even if the potency-form relationship is close enough to survive constitutional challenge, it makes little sense as a matter of policy ; since there is very little potency difference between the mean sample of each form, the distinction cannot be justified in terms of potentially disparate effects on health.

A second objection to the form approach is a definitional one. Hashish is typically defined as the "resin" of the cannabis plant,35 but as the Marihuana Commission pointed out:

[R] ather than representing a clear physical distinction, "resin" is merely a convenient label for describing certain substances exuded by many plants, all of which have certain properties in common. For example, they are brittle in solid form and melt when heated.

The problem is that "marihuana" mixtures contain some resins and "hashish" preparations often contain plant parts other than resins. So, for legal purposes, resin is not the only factor. How could it be defined? Predominantly resin? Substantially resin? Any such formulation might well fail to a vagueness attack.36

Despite these objections, six of the ten states which have decriminalized some marijuana-related behavior have retained the criminal sanction for possession of any amount of hashish, and each relies on the form approach to make the necessary distinction.37 Two additional states relied entirely on the form approach to decriminalize possession of different amounts of cannabis products : both Ohio and North Carolina decriminalized possession of 100 grams of marijuana, five grams of hashish and one gram of hashish oil.38 Only two of the reform jurisdictions, Alaska and Minnesota, decriminalized possession of equal amounts of cannabis products without regard to form or potency.39

If lawmakers are determined to exert a greater deterrent against the use of the most potent preparations, the most sensible approach would be to distinguish between "hashish oil" and other forms of cannabis. Since hash oil is a liquid concentrate, this distinction would be a simple one to make for both users and police. Furthermore, there is a significant difference in terms of average potency between hash oil and the other two forms of the drug. While nearly all samples of both marijuana and hashish contained less than 3 percent THC in the Drug Enforcement Administration study, the lowest potency found for hashish oil was 10 percent, and the mean was 17 percent.40 Thus, hashish oil is easily defined in terms of both form and potency.'"

B. Distributive Conduct

The sale or distribution offense must also be classified in two or more categories to distinguish adequately between commercial activity and activity which is primarily consumption-related. Casual, non-commercial transfers are commonplace in the experience of most marijuana users, partly because of the difficulty of obtaining the drug, and partly because marijuana use, unlike the use of narcotics, is often a communal experience. The most frequent type of transfer is probably the gift of a small amount for immediate use, but other kinds of non-commercial transfers are also quite common. Collective purchases of up to one pound may be distributed among friends with each buyer paying his share of the aggregate cost. In addition, students and other users with limited income sometimes sell small amounts at a slight profit in order to pay for their own use.

Casual distribution of small amounts of marijuana is the functional equivalent of possession of small amounts of the drug. Recognizing this fact, Congress and 18 states treat transfers of small amounts of marijuana without remuneration or without profit as a misdemeanor rather than felonious sales.'" In 1972, the National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse concluded, under the same rationale, that these casual transfers should be decriminalized if they occur in private.43^

Undoubtedly, it is possible to distinguish these casual distributive transactions, as least on a quantitative basis, from smuggling and other commercial activity involving large amounts of marijuana and, consequently, large profits. If, for the same reasons that have prompted decriminalization of non-commercial possessory activity, legislators wish to draw a line at some point along the spectrum of distributive activity, and to decriminalize "below-the-line" transfers, the primary decisions to be made are how and where to draw the line.

One criterion which may be used in classifying distributive activity is the nature of the transaction. A legislator attempting to decriminalize all consumption-related transfers might provide more lenient penalties when the transfer is a gift, when it does not result in profit to the transferor, or when the profit is less than a specified minimum. In terms of proof, it is most convenient to draw the line to exclude only gifts. Cost-only transfers arguably should not remain criminal, but efforts to distinguish non-profit transactions from profitable ones will prove difficult," and case-by-case adjudications of the profit issue hardly seem worth the effort when only small amounts are involved.

The second relevant criterion for evaluation of distributive activity is the amount transferred. A statute which stipulates a designated amount could avoid the problems of proving commercial purpose by creating a statutory presumption similar to the presumptions suggested for possession offenses. Of course, it is conceivable that retail dealers may adjust their behavior to the contours of the law, never transferring more than the specified amount. However, as evidence emerges regarding the operation of such a provision and its impact on retail distribution patterns, the legislature can respond intelligently by simply increasing or decreasing the designated amount.

Given the two available classification criteria, the nature of the transaction and the quantity transferred, there are several possible policy choices. Decriminalization of gifts only is probably the minimum revision consistent with decriminalization of possession. It makes little sense to refuse to accord gifts, which are rarely detected and rarely involve substantial amounts of marijuana, the same penalty status as possession of small amounts ; the donor is an accommodating user and different legal consequences seem fundamentally unfair.

The decision to extend the scope of the decriminalized offense beyond gifts to include non-profit sales, sales of small amounts, or both, requires a sensitive effort to accommodate the goals of decriminalization with continuing law-enforcement needs under a prohibitory scheme. One cannot ignore the risk that decriminalization of any sales will create a loophole for professional retailers. By adjusting his trading patterns so as to make many small sales instead of a few large ones, a retailer might be able to continue a profitable commercial operation without risking any sanctions more severe than an occasional fine. Undoubtedly, a legislator whose primary goal is to decrease criminal justice costs by cutting down on prosecutions of insignificant offenses will want to limit decriminalization to gifts in order to avoid creating a loophole for retailers. On the other hand, maintaining criminal penalties for all sales will not be attractive to legislators who believe that the state's main objective in marijuana control is to contain the aggregate availability of the drug by deterring commercial activity. For such legislators, the aggregate market impact of distribution of small amounts will not be regarded as significant enough to warrant an overinclusive statutory provision which would also sweep non-commercial distributors into the criminal justice system.

Legislators who take the latter view must design legislation that covers most consumer activity without opening a wide loophole for commercial activity. Sales are much more ambiguous than gifts : a sale of two ounces may be a simple "accommodation" between two users, one purchasing part of another's supply at cost; or it may be part of a large-scale, profit-making retail enterprise. The legislator must simply aim to devise a realistic classification which can be applied with reasonable convenience. One approach is to select a relatively low amount, one-half ounce or one ounce, for example, and impose a criminal penalty for all transfers of greater amounts. Another approach is to choose a higher amount and combine the profit and amount methods. For example, legislation could provide that sale of more than two ounces is not a criminal offense if the defendant proves that he made no profit.

Whether or not amount is the conclusive statutory element, the precise figure which the legislature chooses is obviously of major importance. As was noted above, the loophole risk is increased by raising the amount line while designation of an unnecessarily small amount will extend the criminal sanction to too many users. Resolution of this dilemma depends, in part, on an assessment of the practical significance of the "loophole effect." Decriminalization of sales of small amounts may in fact induce retailers to adjust distribution patterns to decrease the risk of apprehension, and it may also induce enterprising consumers to enter the marijuana trade at the retail level. Neither of these effects will be significant, however, unless the criminal penalties already in force, as well as those in effect after decriminalization, have a significant deterrent effect on persons inclined to engage in commercial activity. It is axiomatic that the deterrent effect of criminal sanctions depends to a large extent on the level of enforcement. 45 Thus, if the enforcement of laws against commercial sale is relatively passive, the loophole effect of an accommodation provision will be minor, and a designated amount which is too low may simply increase the risk of discriminatory enforcement without making any significant contribution to the deterrent process. On the other hand, if enforcement is active and the threat of detection is credible, enforcement objectives may well be compromised by an accommodation provision which permits careful retailers to escape punishment.

In summary, the wisdom and technique of decriminalizing accommodation sales depend mainly on the importance that lawmakers attach to prosecution of retailers who profit from the sale of small amounts. A designated amount of two ounces is not likely to affect dealers who customarily transfer amounts over five pounds because it would be too inconvenient to divide up a transaction of that magnitude into enough separate transfers to qualify as decriminalized activity. If legislators believe that enforcement efforts should be concentrated on major sources of supply, a possible loophole for small-scale retailers is a matter of little concern, and the distribution of amounts up to two ounces probably should be decriminalized."

On the other hand, legislators who believe that vigorous enforcement at the retail level has a significant impact on the supply of marijuana will want to limit the scope of decriminalization to such small amounts or to gifts only. It should be emphasized, however, that legislators who would take the latter view probably would still distinguish among commercial marijuana offenses for penalty purposes. Depending on the relative importance attached to proportionality as a limiting principle in the application of criminal sanctions to commercial activity, legislators will want to subdivide the criminal offense of sale into categories that reflect the relative seriousness of the offense. Thus, transfers too serious to qualify for decriminalization may merit petty offense or misdemeanor penalties rather than felony classification.

C. Cultivation for Personal Use

The overwhelming majority of marijuana consumed in the United States is imported from Mexico, the Carribean or Central and South America. Although visitors to these countries may smuggle small amounts for their own use, most illicit importation is commercial in nature and involves substantial amounts. Domestic cultivation of marijuana has never been a serious problem because its THC content is relatively low, but the plant is easily cultivated, can even be grown indoors, and is easily prepared for use. For this reason, small scale cultivation of marijuana is a relatively widespread practice in the United States.

Under most current statutes, cultivation of any amount is punishable as a serious felony, with penalties usually as severe as those for sale.47 It seems clear that legislators interested in reforming their marijuana penalty statute should, at a minimum, revise cultivation penalties in order to distinguish between commercial and non-commercial activity. Assuming that cultivation of small amounts for personal use should be subjected to lesser sanctions than commercial cultivation, two problems remain : whether the reduced offense of cultivation for personal use merits a criminal penalty and what specific amount constitutes commercial cultivation.

A legislator interested only in conserving criminal justice resources while maximizing the deterrent value of the law probably will not be interested in decriminalizing cultivation.

Few arrests are made for this activity and decriminalization of possession is not likely to increase cultivation arrests. On the other hand, a legislator aiming to remove disproportionate criminal penalties from private, consumption-related behavior could decide to decriminalize cultivation for personal use because it is the functional equivalent of private use. Moreover, prohibitions against home cultivation are especially susceptible to arbitrary and discriminatory enforcement, and prosecution and punishment of the few who are detected usually arouse the same sense of unfairness which has provoked the decriminalization of possession.

It might be argued, however, that decriminalization of home cultivation will permit an increase in the availability of marijuana and frequency of consumption by users. Under this view, there is a difference in kind as well as degree between decriminalization of possessory conduct and decriminalization of cultivation : decriminalization of possessory conduct makes it possible for marijuana users to keep a limited supply on hand without risking serious penalties, but decriminalization of cultivation will increase the number of users who maintain a potentially unlimited source of supply.48

One answer to this contention may be that the ultimate social goal of marijuana prohibition, reducing the adverse social consequences of marijuana use, is better served by a sanctioning system which covertly encourages rather than deters home consumption by users. Most homegrown marijuana will be less potent than imported marijuana and presumably will result in fewer adverse health consequences, both acute and chronic. Also, since users who grow their own marijuana will not be supporting the commercial market, decriminalizing personal cultivation might reduce the aggregate demand for smuggled contraband, reducing the price and ultimately reducing the supply. Finally, users who choose to grow their own marijuana are no longer in constant contact with dealers who may also sell more dangerous drugs.

However the decriminalization issue is resolved, legislators should attempt to grade the penalties for cultivation, reducing to a misdemeanor the penalty for non-commercial cultivation of small amounts. Whether decriminalized or reduced to a misdemeanor, the question arises how this personal cultivation offense should be distinguished from commercial activity. Because much of the marijuana plant cannot be consumed, it is probably advisable to use a figure based on the number of plants rather than on the weight of the cannabis, and to designate a number that will yield approximately the amount of usable marijuana which defines the line between criminal and non-criminal possessory offenses. Alternatively, policy makers may wish to set a smaller amount which reflects the importance they attach to discouragement of cultivation, or a larger amount which reflects the fact that a single planting is often intended to yield a year's supply of marijuana.

II. SELECTING SANCTIONS FOR MARIJUANA USERS: THE THEORETICAL CONTEXT

The trend toward marijuana decriminalization must be viewed in the context of generic efforts to redefine the scope of the criminal law. For almost two decades, criminal law scholars and increasing numbers of politicians have called attention to the adverse institutional effects of overcriminalization, and have repeatedly urged the repeal of criminal sanctions for consensual sexual behavior, gambling, public drunkenness and, more recently, illicit drug use." The explosion of drug use in general, and marijuana use in particular, in the 1960's became a major political issue and triggered a sometimes volatile debate over the wisdom and legitimacy of the drug laws.50 Jail terms for middle-class marijuana users sparked controversy and critics of the marijuana laws suddenly had a public audience for the libertarian and social cost arguments against overcriminalization which had been so thoroughly discussed in the scholarly literature during the preceding decade.

When the National Commission recommended decriminalization in 1972, it tried to avoid the political polemics which ensnared marijuana use in wider social conflicts concerning countercultural politics and war protest. Instead, the Commission placed its recommendation squarely in the context of the widely acknowledged need to reallocate law enforcement resources, to restore and preserve the institutional integrity of the criminal justice system, and to strike an appropriate balance between protection of legitimate public interests and the value of personal liberty.51 Similarly, the American Bar Association,52 the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws,53 the National Advisory Commission on Criminal Justice Standards and Goals54 and other expert bodies concerned with the administration of criminal justice have tied their endorsements of marijuana decriminalization to the general need for criminal law reform rather than to the more contentious arguments concerning the rights of drug users.

The theoretical context of marijuana law reform accounts for the incremental nature of the legislative efforts. Since the focus has been on the institutional inappropriateness of criminal punishment, rather than on the rights of marijuana users to use the drug, legislators have generally sought to modify the nature and consequences of the prescribed punishment rather than to immunize the decriminalized behavior from legal control. Whereas the National Commission saw no need to treat consumption-related behavior as a punishable offense, most reform-minded politicians have been unwilling to go so far; instead every statutory implementation of the Commission's recommendation has aimed to achieve the benefits of decriminalization without depenalizing the behavior. While many legislators seem to agree that traditional "criminal" penalties, especially incarceration,55 are too severe for marijuana users, a consensus seems to have emerged that their conduct must nonetheless remain punishable to effectuate society's interest in discouraging use.56 For this reason, the marijuana reform movement must be viewed as the first systematic effort to implement another generic penal code reform : the formulation of non-criminal or civil sanctions for disapproved behavior which is not considered serious enough to warrant traditional criminal sanctions.

The drafters of the Model Penal Code argued that the criminal sanction is too potent, too stigmatizing, and too cumbersome from a procedural standpoint for much disapproved behavior, especially violations of regulatory provisions and local ordinances which are not regarded as morally offensive and many of which require no mens rea.57 To deal with such conduct, the Code drafters recommended that legislatures create a civil violation, punishable solely by a fine whose maximum amount is $500, and resulting in none of the adverse legal consequences which are attendant upon conviction of a criminal offense.58 Several years later, the 1970 Report of the National Commission on Reform of the Federal Criminal Laws endorsed an infraction offense modeled after the Model Penal Code civil violation.59 Similarly, in 1973, the National Advisory Commission on Criminal Justice Standards and Goals, with a mandate to formulate national standards for crime reduction and prevention at the state and local level, urged the creation of a separate administrative structure for processing minor traffic violations, violations of building codes, zoning ordinances, health and safety regulations and evasion of state taxes."

If the Model Penal Code civil offense concept had been widely adopted, it is conceivable that marijuana decriminalization proposals might have focused on the relatively simple question of whether the offense should be reclassified from a misdemeanor to a civil violation, and the legislation itself might have been limited to a simple cross reference to the pre-existing offense classification section of the code. However, most states have not adopted the civil offense concept and those that have done so have usually limited its application to traffic offenses which are in any event not popularly regarded as crimes, even when they are formally classified as misdemeanors.° For this reason, the effort to decriminalize marijuana use has occasioned a confusing array of proposals and statutes which differ significantly from state to state. For the most part, the statutes which purportedly decriminalize marijuana use have only one thing in common : they preclude incarceration as the penalty for a first offender.

Marijuana decriminalization statutes convincingly demonstrate the descriptive inadequacy of the traditional distinction between civil and criminal penalties. Certainly the mere use of one label or the other has no operational significance, for even if legislators have concluded that traditional criminal sanctions, including imprisonment, are not appropriate for least serious marijuana offenses, the sanctions imposed for violating the law may be modified without changing the statutory label. For example, a criminal offense may be punishable by a fine only,62 or, even if an offense is punishable by imprisonment after conviction, systematic use of a pre-conviction diversion program may undermine the original classification as a crime.63 Finally, specific provisions mandating the use of citations minimize the likelihood of deprivation of liberty after arrest, and the consequences of convictions may be ameliorated through other specific provisions permitting record expungement or a statement of "no record" on job applications.64

Even when an offense is classified as a civil violation for purposes of record consequences, the legislature might provide that the offense is still punishable by a confinement period. For example, the current version of the Senate Judiciary Committee's bill revising the federal criminal law creates a non-criminal category of civil infractions, but permits the judge to sentence a violator to up to 5 days in jail:14

In short, there is at present no clear division between criminal and civil sanctions ; instead, legislators have at their disposal a continuum of sanctions of varied severity. Approaching the matter functionally, it is helpful to recognize that involvement in the sanctioning process begins after apprehension for the offense and that some sanctions take effect even before an adjudication. For example, post-arrest consequences may include injury to reputation arising from disclosure of information or records about the fact or circumstances of apprehension ; deprivations of physical liberty occurring when a person is taken into custody, or is required to appear in court; and deprivations of wealth occurring because a person must sustain the expenses of defending himself and may miss time on the job. Similarly, post-conviction consequences may include injury to reputation arising from disclosure of information or records about the fact or circumstances of conviction; deprivations of physical liberty occasioned by sentences to continuous or periodic confinement or even by probation, community service orders and other community-based alternatives to confinement;" and deprivations of wealth occasioned by the payment of fines and lost economic opportunities.

The choice of a particular sanctioning device implicates constitutional procedural requirements which do not necessarily parallel the use of criminal or civil labels. For example, a jail term may not be imposed, even for a day, unless indigent defendants have been represented by counse1.67 On the other hand, no jury trial is required unless the defendant can be sentenced to more than six months in jail." The confusion surrounding sanctions is reflected in the uncertainty over whether the applicable standard of proof must be the criminal standard of beyond a reasonable doubt or a civil standard of clear and convincing evidence or a preponderance of the evidence.69

III. MODIFYING THE CRIMINAL SANCTION: POST-CONVICTION CONSEQUENCES

If imprisonment is regarded as an unjust or inefficient sanction for consumption-related conduct many important issues must be resolved regarding the legal consequences of being found guilty of such conduct. The primary problem is to determine what, if any, legal sanctions are appropriate for consumption-related behavior. If the sanction includes a fine, the amount of the fine and the consequences of nonpayment must be determined. Legislators must also decide if the violation should be punishable by the imposition of a criminal record and if the ordinary consequences of such a record should be ameliorated for consumption-related conduct. Finally, the possibility of increasing the sanction for subsequent offenses and making special provision for minor offenders must also be considered.

A. Are Legal Sanctions Against Use Necessary?

Two of the traditional purposes of penal provisions, incapacitation of dangerous offenders and punishment of intrinsically immoral behavior, are wholly inapplicable to consumption-related marijuana offenses. Instead, the possible utility of a sanction for this conduct lies in its implementation of a policy aimed at discouraging marijuana consumption. In theory, there are three ways that legal coercion, short of a threat of imprisonment, can accomplish this purpose: by deterring the prohibited behavior ; by providing legal leverage to channel detected users into specific programs designed to discourage consumption ; and by symbolizing social disapproval of the behavior and thereby reinforcing attitudes unfavorable to consumption.

Individual decisions to experiment with marijuana have not been significantly influenced in recent years by the fear of legal sanctions70 and, as a practical matter, the incremental deterrent effect of a fine is probably not substantial. Instead, it is the prohibition against distribution which circumscribes the population with an opportunity to experiment by forcing the traffic underground, making the drug inconvenient to obtain. Similarly, these prohibitions against distribution, by establishing the conditions of availability, play a much more significant role in containing the population of continuing users, which includes less than fifty percent of the experimenters, than does the threat of sanctions for possession. A fine applied with certainty would at most decrease the rate of increase in experimentation. Although there are no data measuring the increase in the rate of experimentation when sanctions are removed altogether, the data in states which have enacted fines in lieu of jail terms are wholly consistent with this analysis?' Since the opportunity to consume occurs mainly in private, continuing sanctions against possession will serve at most to discourage regular users from transporting their marijuana on their person or in their vehicles when they venture into public.

While legal sanctions may be of significant value in providing the leverage to channel alcoholics and heroin addicts into treatment programs, they appear to be of minimal value where marijuana users are concerned. As noted earlier, the overwhelming majority of persons who experiment with marijuana and use it recreationally are not in need of treatment ; they are indistinguishable from their non-marijuana-using peers by any criterion other than their marijuana use." Instead, the main value of leverage is educational and preventive rather than therapeutic. It must be questioned, however, whether the costs of enforcing such a sanction and maintaining an educational program are worth the probable benefits. Persons who have been apprehended for marijuana possession will probably not be told anything that they do not already know. If the objective is simply to counsel against the use of more harmful substances, the imposition of legal sanctions seems to be a costly and unnecessarily coercive method of reaching this result. Indeed, it seems unwise to pervert the criminal justice system to serve functions which ought to be performed by the public school system. If children and adolescents apprehended for marijuana possession need to be channeled formally into appropriate counseling or educational programs, the jurisdiction of the juvenile justice system is sufficient for this purpose. In sum, leverage is an inadequate justification by itself for imposing legal sanctions on consumption-related activity by all marijuana offenders, including responsible adults.

The most convincing argument for retaining some legal sanction for consumption-related behavior is its presumed symbolic effect. It can be argued that the educative or moralizing influence generated by a formal expression of social disapproval reinforces other socio-cultural forces which shape desired attitudes toward consumption of psychoactive drugs in general and marijuana in particular." From a purely empirical standpoint, the pertinent question is whether the penalty for consumption significantly augments the symbolic message conveyed by the total prohibition against cultivation, importation and distribution ; or, whether the absence of a sanction connotes approval of marijuana possession despite enforcement of prohibitions against availability. The data compiled in Oregon and other reform jurisdictions strongly support the hypothesis that decriminalization does not, in itself, encourage use, although the penalty reduction does seem to convey and reinforce the message that use of marijuana is not as harmful as was formerly thought.74

The utility of legal sanctions for marijuana consumption depends on whether the incremental deterrent and symbolic effects of the legal sanction in decreasing the number of users and the frequency of their use warrant the resulting administrative costs and invasions of personal privacy. Ten members of the National Commission did not think so, although three members endorsed the civil fine primarily for symbolic reasons.75 Legislators have neglected to study the question at all, and have simply assumed that some sanction is better than none at all. Even from a purely fiscal point of view, this assumption may be unjustified ; administrative costs of enforcing and processing the fine probably substantially exceed the amount of money collected in most jurisdictions. The costs of criminal justice processing can be reduced substantially, however, by foregoing the customary incidents of the criminal process such as booking, custody and personal appearance in court.76 Also, as the experience with the California fine statute has shown, a large number of detected and sanctioned violations can produce a sizeable amount in fines.77

In summary, these observations suggest that a legislator who believes that some legal penalty for marijuana consumption is necessary to discourage marijuana use should select a fine, not a leverage sanction, and should facilitate its efficient and minimally intrusive administration. On the other hand, a lawmaker who believes that the incremental symbolic and deterrent effects of a consumption penalty do not significantly exceed the preventive effects of continuing prohibitions against distribution, or who believes that any penalty for possession is disproportionate to the harm engendered by the conduct, should withdraw all legal sanctions from least serious consumption-related behavior as the National Commission recommended.

Even if the legislature concludes that least serious marijuana offenses should remain punishable by some sanction, it should consider limiting the application of the prescribed penalties to violations which occur in public places, including moving vehicles. A clear statutory distinction between public and private behavior would tend to channel marijuana use into private locations, thereby reducing the likelihood of intoxication and incapacitated behavior in public. The main reason for excluding possession in a "private" location from the sanctioning provision, however, is that the threat of intrusions into the home is of limited deterrent value under any foreseeable enforcement circumstances. The overwhelming proportion of marijuana arrests under current criminal statutes occur as a result of police patrol activities, either on the street or in connection with vehicle searches." Further, the detection of marijuana consumption in the home should have a low priority for police investigative resources, and an explicit decriminalization of private possession will both establish a clear legislative direction on this point and eliminate the risk of harassment and discriminatory enforcement associated with searches of private locations.

Retention of civil penalties for private possession will not eliminate these problems ; if private possession of less than the statutory amount remains a non-criminal offense, users will still be subject to apprehension in the home." Moreover, possession of a small amount might be used as a pretext for searching the home for larger amounts, or even for arrest on suspicion of possessing larger amounts. In order to prevent these intrusions, which occur too sporadically to represent a credible deterrent, private possession of less than the designated amount could be excluded from the definition of noncriminal as well as criminal marijuana offenses."

No state has yet depenalized private possessory conduct, but the Alaska law takes an important step in this direction. Public possession of more than one ounce is a misdemeanor as is public use of the drug, whereas public possession of one ounce or less is punishable as a civil offense. In contrast to the amount approach used for public behavior, however, private conduct is graded by the pure intent approach : private use or private possession of any amount is a civil offense unless there is proof of intent to sell.81

B. The Record Consequences of Arrest and Conviction: Is Stigma Necessary?

If the legislature decides to impose a fine for least serious marijuana-related behavior, it must also decide to what extent, if at all, the commission of such an offense will subject the offender to the criminal process. A criminal arrest, even if no conviction follows, will normally be a traumatic experience, particularly for the first offender. Even if the arrestee is ultimately released without charge or is acquitted, he will suffer the inconvenience and embarrassment of being brought to the police station, photographed, and fingerprinted. This deprivation of liberty could last a significant length of time, especially if bail is required and the defendant is unable to post it immediately. He also may miss work while being detained, and, even if he loses no working time, his employer may dismiss him upon learning of the arrest.

The existence of an arrest record can also detrimentally affect the arrestee in subsequent encounters with the criminal justice system : he is less likely than a person without a record to receive lenient treatment from the prosecutor in the form of dropped or reduced charges, and an arrestee with a record may receive a harsher sentence than a similarly situated first offender.82 An arrest record may also limit the arrestee's employment opportunities, especially if this information is accessible to potential employers. Even if the information is not disseminated, the arrestee may be prejudiced by being asked whether he has ever been arrested or convicted of a crime, a common question on most applications.83

If the arrestee is subsequently convicted of a criminal offense, all of these record consequences are exacerbated by the numerous legal disabilities flowing from the criminal conviction, even for a misdemeanor. The records may be accessible to both public and private employers. The convicted misdemeanant may be precluded by licensing laws from engaging in certain occupations and from securing public employment. A convicted felon in virtually all states is ineligible for occupational licenses and public employment and is usually disenfranchised as well."

A number of state legislatures have enacted generic provisions for reducing these consequences of criminal arrest and conviction records,85 and federal regulations now govern the dissemination of arrest records." Thus far, however, the piecemeal nature of the effort to modify criminal sanctions for marijuana use has required legislators to focus on these questions for this offense alone rather than as part of a general reconsideration of the effect of criminal records. Thus it is worthwhile to consider alternative methods for ameliorating the record consequences of arrest and conviction as part of a reduction or elimination of criminal penalties for consumption-related marijuana behavior. Of course, the extent to which record consequences are ameliorated may differ according to the rationale for changing the sanctions applied to the use of marijuana.

There is reason to believe that favorable legislative sentiment for decriminalization is largely attributable to a widely shared view that the stigma associated with traditional criminal processes is a disproportionately severe punishment for such a minor, widely committed, offense. Reform-minded legislators, and their constituents as well,87 apparently believe that possession of marijuana for one's own use simply is not a sufficiently serious offense to warrant the imposition of all the legal, economic, and social disabilities ordinarily associated with the criminal sanction. Apart from this elementary notion of proportionality, a related rationale may be the unfairness to the individual and the counterproductive social effect of stigmatizing marijuana offenders with criminal labels. For either reason, a legislator may well believe that any type of criminal stigma associated with marijuana use engenders a disrespect for the criminal justice system as a whole.

Legislators who adopt this view are not influenced by arguments that the criminal stigma generates deterrent and symbolic effects not associated with non-criminal processes and penalties. Even those legislators who are not categorically opposed to serious, even stigmatizing, sanctions for marijuana users may nonetheless believe that the incremental preventive value of criminal processes and records is offset by the administrative costs of implementing them. A legislature might easily determine, for example, that the police resources now employed in booking, recording, and maintaining the records of marijuana offenders could be better expended in the prevention and punishment of crimes against person or property. Similarly, legislators might well find that the procedural system necessary to process criminal offenses is too costly, and they may be willing to sacrifice the stigmatizing effects of the sanction to facilitate expeditious and convenient processing of offenders.

Whether for reasons of fairness or expediency, five of the ten reform jurisdictions have reclassified least-serious marijuana behavior as a "civil" offense and have eliminated all the record incidents of apprehension, adjudication, and other aspects of the criminal process.88 Ohio has specifically eliminated all of the record consequences of the criminal process but has nevertheless insisted on classifying the offense as criminal.89 A more explicit statement of the presumed symbolic, moralizing effects of the mere labeling of disapproved behavior as a crime can hardly be imagined.

In contrast, the legislatures in the remaining four states not only retained the criminal classification of the offense but also retained some of the normal record consequences of the criminal process. Analysis of these statutes reveals no consistent pattern : arrest records are created in some but not in others ; adjudications of guilt constitute convictions in some but not in others ; and arrest and conviction records are automatically expunged or sealed in some but not in others."

It is difficult to offer guidance to legislators who wish to ameliorate but not eliminate the record consequences of the criminal process. To the extent that the reform is designed primarily to accommodate the presumed deterrent and symbolic value of the criminal penalty while reducing the cost of administering it, several devices are available. First, eliminating formal booking procedures will save police the time, and arrestees the inconvenience, associated with fingerprinting and photography. Persons apprehended would simply be issued citations to appear in court. In addition, two basic approaches involving various degrees of destigmatization are available to adjust the severity of the record consequences to the less serious nature of the offense : expunging or sealing records immediately after conviction or expunging or sealing the records after expiration of a stipulated period of time. Either of these two approaches could be supplemented with the right to state the nonexistence of arrest or conviction for a criminal offense to employers or other questioners.

The choice among immediate or postponed expungement or sealing depends upon how the legislature balances the presumed deterrent effect of the criminal penalty against the unfairness of stigmatizing minor marijuana offenders. If the legislature is seriously concerned about adverse economic effects of criminalization, a crucial feature of the reform should be to permit the offender to deny any criminal arrests in connection with employment inquiries. To be effective, the remedy should take effect immediately after arrest.

The central consideration in choosing between expunging and sealing the records is whether future access to the records is considered necessary for certain limited purposes, such as research needs. If penalties are to be increased for subsequent offenses by the same offender, immediate expungement could not be employed. If a sealing provision is enacted, however, measures should be taken to prevent unauthorized dissemination by removing information identifying offenders or segregating sealed files and restricting access to them.9'

A legislative decision to retain the stigmatizing consequences of marijuana violations should be carefully considered. Quite apart from the interrelated notions of proportionality and fairness noted earlier, potent utilitarian arguments may be interposed against efforts to derive deterrent and symbolic benefits from the imposition of criminality. Scholars have argued, for example, that the moralizing value of the criminal sanction may be diluted by its application to minor, widely committed offenses.92 "The ends of the criminal sanction are disserved," Herbert Packer claimed, "if the notion becomes widespread that being convicted of a crime is no worse than coming down with a bad cold."" Although this hypothesis is not easily tested, the oft-repeated assertion that marijuana law enforcement generates disrespect for law signifies its plausibility. Already bar examiners, medical licensing boards, colleges and graduate schools and other licensing and screening agencies are routinely confronted by applicants who have been convicted of marijuana offenses but seek to escape the customary consequences of "criminality." When the social meaning of a disapproved behavior is severed from the presumption of immorality, perpetuation of stigmatizing penalties may serve only to undermine the social meaning of the sanction itself.

C. The Imposition of "Non-Criminal" or "Less Criminal" Sanctions

Whether or not the sanctioning process generates "criminal" record consequences, several operational questions are raised regarding the administration of the residual penalty : the amount of any fine, the consequences of nonpayment, and the structure of any educational program.

If a fine is chosen as the sanction for least serious consumption-related behavior, there are a number of reasons for limiting the maximum fine to an amount comparable to the penalty for a serious traffic offense, no more than one hundred dollars, for example. First, there is no evidence that the deterrent effect will differ according to the amount of the fine once it reaches a certain non-nuisance level, $25 for example. Second, symbolic effects are retained by any fine, regardless of the amount, as long as it is not de minimis. Third, the practical and legal difficulties associated with administering the sanction, discussed below, are mitigated if the amount of the fine is held to a minimum.95

The administration of a financial penalty for marijuana offenses raises several important issues. The most efficient way to collect a fine, of course, is to insist upon payment immediately after apprehension and conviction. However, any procedure for enforcement of payment, even against defendants who are in fact able to pay, must provide an initial hearing to determine ability to pay. Although the Supreme Court has not fully described the procedural requirements of this hearing, it seems likely that they include the right to counsel and the right to present witnesses in defense of a claim of indigency.96 Moreover, it has been held that, prior to the indigency hearing, the defendant cannot be confined at all."

If a defendant is judged able to make immediate payment and refuses to do so, or if he is given a reasonable opportunity to pay the fine consistent with his financial situation and he fails to take advantage of this opportunity, he can be incarcerated for a period of time, although the constitutional limits of this period are not yet settled." It is no longer constitutional, however, to imprison a defendant who is financially unable to pay his fine.99 Such a defendant must be allowed a period of time that affords him a realistic opportunity, under the circumstances of his case, to make payment through installments or otherwise.1"

An alternative means of collecting fines from indigent defendants is to require them to report for work on some public project for the number of days necessary to satisfy the fine, although this approach also may involve constitutional problems to the extent that the work is perceived as custody. If this method of payment is presented as an alternative to installment payments, however, it may simplify collection from defendants who are tempted to use present indigency as an excuse for future non-payment.

The best method of dealing with the problem of indigency is to permit judges to offer any person who pleads inability to pay the option of performing some public service involving an equivalent sacrifice of time. This approach can also be employed in cases involving offenders whose drug involvement is significant enough to suggest that participation in some educational program would be beneficial. If such programs have an educative effect at all, that effect is likely to be greater to the extent that the defendant's participation is voluntary. If defendants are given the realistic choice of either paying the fine or attending the program, those who enter the program will be attending, at least in part, of their own volition, and will be much more likely to benefit.

If the preferred sanction is an educational program rather than a fine, it should resemble, in terms of time and convenience, the driver education programs required for youthful violators or multiple adult offenders. Experience with drug education programs clearly indicates that the objective cannot be to teach participants about the evils of marijuana use.ioi Instead, the objective must be to instill responsible and mature attitudes toward the use of psychoactive substances, including both marijuana and alcohol. The Minnesota educational program for marijuana offenders follows this model.102 It is suggested above that a mandatory "leverage" sanction, applied in lieu of a fine in all cases involving the least serious consumption-related behavior, amounts to legislative overkill.103 On the other hand, it should be emphasized that an educational program may be a useful optional sanction for persons unable to pay the fine and it may also be an appropriate dispositional alternative for some repeat offenders'" or youthful violators. The latter situations, however, involve generic questions regarding the desirability of different, more burdensome sanctions for subsequent offenses and violations by minors.

D. Should Penalties Be Increased For Subsequent Offenses?

Assuming a state has decided to decriminalize some marijuana behavior, and to impose a "civil" fine for these "least serious" offenses, the question arises whether the sanction applied should vary with the number of such offenses committed by the same offender. There are three alternatives : to retain the same penalty for subsequent offenses as for first offenses ; to impose a larger fine for subsequent offenses ; or to apply more severe "criminal" sanctions, in the form of either stigmatizing record consequences or incarceration or both, for subsequent conduct.

Again, the rationale which underlies the initial decision to reform the marijuana prohibitions will affect the evaluation of possible alternatives. If the legislature wishes to minimize the involvement of marijuana users in the criminal system because of its concern about the fairness of enforcement and the disproportionality of criminal sanctions to the offense, then it makes little sense to alter the nature of the penalty for second offenders.'" Only an increase in the fine would comport with the goals of decriminalization and even then the cost of retaining and searching records is hardly warranted by any increased deterrent effect. On the other hand, if the legislators' primary goal is simply to decrease the cost of enforcing marijuana prohibitions while retaining maximum preventive effects, then imposing higher penalties for subsequent offenses may be a rational course. Such an approach is not costless, however. Apart from the costs of processing and punishing repeat offenders, increased penalties also require retention of records of initial violations in order to determine whether a violator is a second offender.

The costs of enforcement will be substantially increased if the legislature authorizes imprisonment rather than civil fines for subsequent offenses. Aside from the obvious expense of incarceration, one principal advantage of the fine-only scheme—the elimination of costly trials—will be lost if incarceration is authorized, because defendants will be less likely to plead guilty if they face possible confinement. The threat of imprisonment may also engender more technical search and seizure claims both at trial and on appeal, all of which will operate to drain already scarce judicial resources. Even a "criminal" sanction which excludes imprisonment will add significantly to the cost of deterring marijuana behavior. More formal procedures will have to be utilized during arrest because the offender must be brought to the station, fingerprinted, and photographed; criminal records will have to be maintained ; some defendants may be inclined to contest the charge either to avoid the higher fine or the criminal stigma ; and notions of procedural fairness may require that publicly-paid counsel be offered to indigent offenders.'"

Apart from considerations of fairness and cost, the legislature may wish to evaluate the possible utility of the sanctioning system as a leverage device in cases involving recidivists. Repeated apprehension for marijuana offenses may indicate, in some cases, that the individual has progressed beyond purely recreational use of marijuana to a more intensified pattern of psychoactive drug use. Nonetheless, a judicious use of discretion to utilize optional educational or counseling programs is a more efficacious way of dealing with this problem than the enactment of categorical increases in sanctions for subsequent offenses.

Whether for reasons of fairness or efficiency, six of the ten states which have decriminalized least serious marijuana behavior do not enhance the penalty for subsequent offenses.107 However, legislators in the four other reform jurisdictions have apparently been persuaded that the incremental deterrent effects of more severe penalties warrant the costs of imposing them on repeat offenders. Threatened penalties for second offenses vary widely : the fine is merely doubled in New York ;1" a large fine and up to 60 days may be imposed in Mississippi, although the violator earns no criminal record ;109 and criminal fines and jail terms of three months and six months may be imposed in Minnesotan° and North Carolina.'" respectively.

E. Applicability to Minors

A further question raised by the decriminalization of marijuana is whether the reforms should recognize a distinction between juvenile and adult offenders. The same legislator who does not object to reducing the penalty for possession for personal use to a fine paid by mail when the offender is an adult may wish to grant jurisdiction to the juvenile court when the offender is a minor. The issue is whether decriminalizing possession of marijuana for personal use will require a change in the definition of juvenile delinquency in order to allow possession of marijuana to remain an allegation sufficient to support a juvenile delinquency petition.112