Chapter 6 EUROPE AND DECRIMINALIZATION: A COMPARATIVE VIEW

| Books - Marijuana Use and Criminal Sanctions |

Drug Abuse

Chapter 6 EUROPE AND DECRIMINALIZATION: A COMPARATIVE VIEW*

* This chapter was prepared during the spring of 1977 for the Director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse under Contract No. 271-77-1211.

Introduction

Drug control laws do not emerge haphazardly. International trends have always played a dominant role in triggering and shaping domestic legislation. Thus, the initial anti-narcotics legislation in most countries of the world was enacted in the 1910's and 1920's in response to the Opium Conferences of 1912 and 1924. Another wave of drug legislation swept the industrialized world in the 1950's in partial response to a post-war increase in drug abuse and in confirmation of the creation of new United Nations agencies. Then, the explosion of drug use, especially cannabis, in North America and parts of Europe during the late 1960's, as well as an apparent increase in availability and use of heroin in many countries of the world, stimulated a great deal of international activity in the late 1960's. The result was promulgation of new international agreements as well as a new wave of domestic drug legislation beginning about 1970.

Several common themes are immediately discernible in much of this new legislation. First of all, the same interest in tighter regulatory controls which generated the Convention on Psychotropic Substances and the Amendments to the Single Convention also triggered domestic legislation which extended sophisticated regulatory controls to a larger number of controlled drugs. Secondly, criminal penalties for trafficking offenses have been increased' and the new provisions have aimed to stimulate and facilitate international cooperation in detecting and disrupting international trafficking organizations.2 Finally, a third trend, which is the subject of the present investigation, is a general reorientation of penal policy toward the use of illicit drugs and other consumption-related activity. A major theme in all recent revisions has been to draw substantive penal distinctions3 between trafficking activity and consumption-related activity, at the least by increasing the penalties for the former and reducing the penalties for the latter. Frequently, however, the reductions in consumption-related penalties are tied to the establishment of alternatives to traditional penal sanctions, especially incarceration, and to the use of supposedly "nonpenal" measures!' Sometimes these reforms are said to have "decriminalized" or "depenalized" drug use, although these terms are used to refer to a wide variety of statutory modifications.

Concurrent with these drug-abuse policy trends, the international community of criminal justice experts and officials has engaged in a collaborative effort to share information about generic reforms of the criminal process, especially in three areas : the control of discretion in the administration of criminal justice; the development of alternatives to traditional criminal sanctions, especially imprisonment ; and the reassessment of the scope of the substantive criminal law.5 In many countries, revised policies toward drug use have represented the first major efforts to implement these generic policy trends in a specific substantive area.

These legislative developments have been most pronounced in Western Europe and the Anglo-American countries, where cultural similarities have spawned similar problems in criminal justice administration and where the search for solutions has proceeded in a similar normative climate. The Council of Europe has been especially active and its Committee on Crime Problems has published numerous source documents on these general themes.6

Purpose and Method of Investigation

The primary purpose7 of this investigation was to describe the recent modifications of penal provisions toward drug use, and the resulting patterns of enforcement, in a selection of West European countries, to assess the implications of these emerging policies and practices, and to evaluate the utility of these approaches as models for reform in other countries, including the United States.

Much has been said in recent years about the importance of creating "non-criminal" means of discouraging illicit drug use and minimizing the social costs of drug abuse. Yet, despite this proliferating interest, little information has been shared. Part of the problem is the diversity of criminal jurisprudence, both substantive and procedural. Indeed, the very concept of "decriminalization" has very different connotations in different countries, depending in part on the meaning of the term "crime" or its equivalent. To some extent this comparative analysis is intended to bridge that gap in information and understanding.

This chapter is comprised of five case studies of recent drug law revisions in France (1970), Italy (1975), Switzerland (1975), The Netherlands (1976), and the United Kingdom (1971 and 1977). In each of these countries, structured interviews were conducted on site with knowledgeable persons in official and quasi-official positions,8 and efforts were also made to obtain all relevant statistical data and official statements. The final section synthesizes the case-study information and also incorporates secondary information concerning legislative revisions or administrative practices in Denmark and Austria, although none of these countries was studied first hand. As will be explained below, these European reforms have not been shaped from the same mold. They each employ different devices for implementing a shared policy of reducing reliance on the criminal sanction as a means of discouraging illicit drug use.

The Legal Background

This chapter presents a comparative analysis of recent revisions of penalties for consumption-related drug offenses. As was indicated earlier, these legislative activities have occurred against the backdrop of international treaties and domestic legal traditions which, respectively, establish the outer boundaries and substantive contours of reform. Thus, it is important to review at the outset the obligations imposed by international law and to develop an analytical framework for extracting patterns, themes and issues from the diverse array of national laws.

Obligations Imposed by International Law

Under the prevailing and authoritative interpretation of the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs (1961), the parties are not obligated to make use, possession for personal use, and other consumption-related activity punishable offenses. Article 36 does require the parties to ensure that "cultivation, production, manufacture. . . possession, offering, offering for sale, distribution, purchase, sale, delivery on any terms whatsoever . . . shall be punishable offenses" but it is generally accepted that the term "possession" in this Article refers to possession with intent to distribute and not to "simple" possession or possession for personal use. Although the parties are bound by Article 4 (c) to "take such legislative and administrative measures as may be necessary . . . to limit exclusively to medical and scientific purposes the . . . use and possession of drugs" and are enjoined by Article 33 not to "permit the possession of drugs except under legal authority," these provisions have been authoritatively construed to require an official policy of discouragement and prevention but not necessarily through the use of penal measures.

The parallel provisions of the Convention on Psychotropic Substances have been construed in a similar fashion.

The nascent international interest in the development of non-penal measures of prevention was codified during 1971 and 1972 in several provisions of the Convention on Psychotropic Substances and in the 1972 Protocol Amending the Single Convention. For example, paragraph (1) of Article 20 of the Psychotropic Convention requires the parties to take "all practicable measures for the prevention of abuse of psychotropic substances and for the early identification, treatment, education, after-care, rehabilitation, and social reintegration of the persons involved." Article 15 of the 1972 Protocol, amending Article 38 of the Single Convention, is to the same effect. Similarly, paragraph (1) (b) of Article 22 of the Psychotropic Convention expressly authorizes the use of non-penal methods of intervention even in the cases of persons who have committed offenses which must be made punishable under Article 22(1) (a) :

Notwithstanding the preceding sub-paragraph, the parties may provide, either as an alternative to conviction or punishment or in addition to punishment, that such abusers undergo measures of treatment, education, after-care, rehabilitation, and social reintegration in conformity with paragraph 1 of Article 20.

Article 14 of the 1972 Protocol amended Article 36 of the Single Convention to the same effect.

The Meanings of Penal Sanctions

For ease of reference and comparison, it is necessary to sidestep some variations concerning the substantive definition of drug offenses and the classification of penalties. The central substantive concept employed in this chapter is "consumption-related behavior," a term which is designed to encompass a wide range of non-commercial conduct including use, purchase or possession of small amounts for the purpose of personal use, or non-commercial distribution to acquaintances for their own personal use. For the moment, no effort is made to convert these concepts into legally-defined offenses. As will become apparent below, the laws of the subject countries use somewhat different substantive devices for converting these policies into legally defined offenses. For present purposes, however, these variations are not especially important.

Differences in penalty classifications will be neutralized by focusing on the types of penal consequences which are prescribed for consumption-related activity: the direct punitive consequences (deprivations of property or restrictions of liberty) imposed "for" the offense ; and the derivative or indirect consequences of involvement in the process or of an officially recorded violation. Together these consequences are referred to, interchangeably, as sanctions or penalties. As was noted earlier, the terms decriminalization and depenalization are frequently used in connection with recent drug law reforms.

But they have no generally accepted meaning ; this imprecision is largely due to the lack of any common conceptions about what differentiates "criminal" sanctions from other kinds of sanctions—a theoretical gap which exists not only across legal systems but also within each country's jurisprudence, including the United States.9

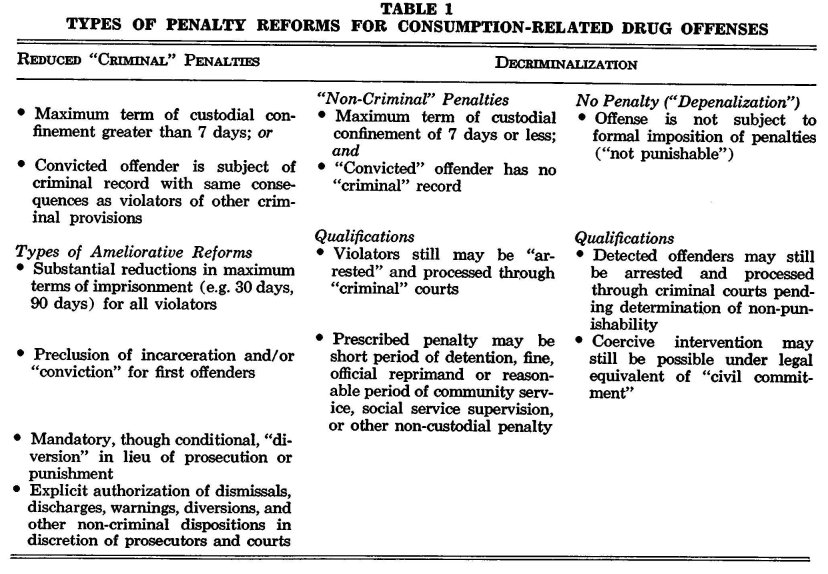

The confusion surrounding use of these terms will not deter us from using them here ; instead, definitions will be stipulated for convenience of reference and comparison. Table 1 summarizes the differences in penal consequences by which reductions in "criminal" penalties may usefully be distinguished from "decriminalization" and by which substitution of noncriminal penalties may be distinguished from a more or less complete repeal of penalties.

An offense will be regarded as having the characteristics of a "criminal" offense" if (a) the convicted offender is punishable by a period of custodial confinement in excess of one week or (b) if identifying information about the conviction is reported to a penal record documentation center and is thereby subject to the legal consequences which generally attach to conviction of a criminal offense.

Even if the offense remains a "criminal" one, a legislature may reduce or lessen the consequences of conviction in many ways. First "criminal" offenses may be punishable by penalties of varying severity. In some countries, the penalties have been substantially reduced for some use-related offenses—for example, 30 to 90 days may be the maximum penalty. Second, incarceration and/or the adverse record consequences may be precluded for first offenders. Third, prosecutors and courts may have the discretion to forego imposition of a "conviction" (hence a criminal record) or incarceration in particular cases even though the offense is itself punishable by conviction and imprisonment. Finally, the prosecutors and courts may be required or permitted to waive prosecution or punishment if the offender participates in a treatment program ; such "diversion" schemes do not effect a "decriminalization" because the criminal process may be re-instituted if the offender fails to participate satisfactorily in the prescribed program. In all of these situations, non-penal or "less penal" measures can be (or must be) invoked even though the offense itself remains punishable as the equivalent of a criminal offense.

Conversely, if some consumption-related behavior is not punishable by criminal penalties as defined above, that behavior will be said to be "decriminalized" even if some other penalty is prescribed (such as a fine or a short period of detention) so long as the person is not regarded as having a "criminal" record. If the behavior is not punishable by any penalties, it will be regarded as having been "depenalized." Thus, depenalization is regarded as a more liberalized type of decriminalization."

As will be shown below, the legislatures of Italy and Switzerland have depenalized consumption-related behavior. In contrast, recent revisions of the French, Dutch, and British laws have effected some reduction in penalties for at least some consumption-related behavior and have introduced a number of devices for ameliorating the penal consequences of conviction. But the offenses remain criminal offenses, at least on the face of the law. It will also become clear, however, that decriminalization (or, indeed, depenalization) of some consumption-related behavior can be achieved, in practice, through the systematic exercise of official discretion by police, prosecutorial, and judicial agencies, even though the prescribed penalties are criminal ones. This has been documented, for example, in The Netherlands and in Denmark.

Penal Sanctions and Other Types of Coercion

Apart from the variations in severity of prescribed penalties for the consumption-related offense, another complicating factor is the relationship between penal sanctions and other mechanisms of coercive legal intervention. Suppose, for example, that a legislature (a) repealed all penalties for consumption-related behavior, stating that use, possession for personal use, and other related conduct are not "punishable offenses ;" and (b) provided instead that any person who is a "user" of illicit drugs may be ordered to participate in an appropriate treatment program. Presumably the determination that the person was a "user" would be based on the conduct which was formerly proscribed and punished. This type of legislative scheme substitutes a "control" model of coercive intervention for the sanction or "punishment" model. The intervention may be ordered by "civil" courts instead of criminal ones and the records of proceedings may be accessible to different agencies, and the restrictions of liberty may occur in different buildings and be ordered by different individuals and agencies. But the records, deprivations and restrictions may be equally stigmatizing and may be viewed by the subjects themselves as equally obnoxious.

Fortunately it is not necessary to decide here how such a scheme would be classified and evaluated from a jurisprudential standpoint. No country has attempted to replace the penal prohibitions with equally comprehensive "civil commitment" schemes. But there are several variations on this theme which should be mentioned here.

On the one hand, some statutes retain the classification of consumption-related behavior as offenses punishable by imprisonment but require the use of non-penal measures of intervention for a more or less defined category of users—for example, those charged with use or possession of small amounts for personal use. This type of statute does not "decriminalize" the behavior, for it remains an offense ; it does not "decriminalize" the process, for the offender is still subject to arrest and involvement in criminal proceedings ; it does not lift the threat of criminal sanctions because the offender is subject to conviction and punishment if he resists, or fails to participate satisfactorily in, the therapeutic regimen ; and, as this implies, it still reflects a philosophy of coercive intervention. These "mandatory diversion" statutes have been enacted in France (Act of December 31, 1970) and Austria (Act of June 24, 1971) . In several other countries, the law permits, but does not require the prosecutors and courts to substitute non-penal measures for penal ones. Such a permissive diversion scheme has been adopted in the Federal Republic of Germany.

On the other hand, it should be emphasized that both the Italian and Swiss laws, which have decriminalized the conduct, do retain mechanisms for coercive intervention. This is especially true of the Italian law which establishes an elaborate scheme of referral to social welfare and medical centers. But these schemes are distinguishable from the hypothetical statute described earlier because they do not impose the medical model on all drug users. Instead, the possibility of compulsory treatment is limited to those who are determined, in a separate judicial proceeding, to be "in need" of medical intervention. Although a commitment statute is subject to abuse, it does draw on a legal tradition considerably different from the criminal law.

FRANCE

French drug laws were overhauled by the Act of December 30, 1970. In general, this law increased the penalties for trafficking offenses, reduced the penalties for consumption-related offenses, and established a scheme of diversion for drug users. For first offenders, the statute requires the substitution of non-criminal means of intervention for the traditional criminal sanctions.

Provisions of the 1970 Act

Prior to the 1970 Act, "repression" through the penal law12 was the dominant theme of French narcotics laws, and trafficking and consumption penalties were functionally indistinguishable. According to official observers, the use of illicit drugs, primarily heroin and hashish, first became visible in the late 1960's, triggering parliamentary consideration of the issue in 1969. The direction of the popular mood is indicated by a September 1971 public opinion survey which indicated that 58 percent of the respondents thought that pushers deserved heavy prison sentences and 38 percent thought that these offenders ought to be put to death."

Apparently the reforms enacted in 1970 were intended to translate into French law the themes that were becoming prevalent in the international discussions of the day : substitution of humanitarian measures for dealing with the user while increasing the penalties for traffickers. Even the title of the law—"Concerning Health Measures of the Struggle Against Drug Addiction and the Repression of the Traffic and Use of Poisonous Substances""—captures this dual theme.

Basic Penalty Provisions

The basic penalty provision of the 1970 Act appears in Articles L. 627 and L. 268. Trafficking offenses are punishable by imprisonment from two to ten years and by a fine of from 5,000 to 50,000,000 French francs ($1,000 to $10 million) . Illegal importation, production, manufacture or "exploitation" are punishable by 10 to 20 years' imprisonment. For recidivists, the penalties are doubled.

Use offenses, on the other hand, are punishable by imprisonment of two months to one year or by a fine of 500 to 5,000 francs ($100 to $1,000) . It is notable that under the French criminal code the offense is "illegal use" and the act of possession is included in the trafficking provision. However, it is understood that it is within the discretion of the magistrate and the public prosecutor to distinguish in the initiation of the criminal process between the person who possesses for personal use and the person who possesses with intent to distribute. It is also noteworthy that the 1970 Act also proscribes "use" in all places ; before the Act, public use of any drug was punishable while private use was punishable only if the drug consumed was cannabis, khat or heroin. The 1970 Act abolished the distinction among drugs and made their use a punishable offense in all cases.

Relative Seriousness of Penalties

Under French law the term "crime" is reserved for only a few of the most serious offenses such as intentional homicide. The great mass of what we regard as criminal offenses in the United States are classified as "délits" which, in theory, are less serious." As a practical matter, however, no difference in severity of penalties is apparent ; all drug offenses, including trafficking are délits, even though the penalties range as high as 20 years for a first offense. The only differences are procedural ; unlike the true "crimes" which are triable at the "cour d'assises" (three magistrates and a jury of nine citizens) , délit offenses are triable before the tribunal "correctionel"—now referred to as the tribunal de Grande Instance (composed of three magistrates) .

Another category of offenses encompasses traffic and local ordinance violations and other petty police offenses which are triable in the local police courts.16 Ordinarily, these offenses are punishable solely by a fine, although in cases of recidivism the sentence could be up to two months. Apparently this is the maximum sentence of imprisonment for these petty offenses. This shows why the minimum term of imprisonment for illicit use of drugs is two months. No consideration has apparently been given to utilizing such a penalty scheme for consumption-related drug offenses.

Other Penalty Provisions

Several provisions of the 1970 French law, then unique, have inspired similar provisions in other countries and, for that reason, merit mention here. First, traffickers may be punished by a range of unusual sanctions such as banishment (2 to 5 years), withdrawal of passport (up to 3 years) or suspension of driver's license (up to 3 years) .17

Second, the Act creates a new offense of encouraging or inciting illicit drug use:

Whoever by any means has incited to the commission of [a violation of the use or trafficking provisions described above], although this incitement did not result in an act or the offense had no serious consequences, shall be punished by imprisonment from one to five years and by a fine from 5,000 F to 500,000 F, or by one of these penalties. . . . The same penalties will be imposed upon those persons who by any means incited to the use of substances and plants having the effect of opiates, even if the incitement did not result in an act.

In the case of an incitement in writing, even if introduced from abroad, verbally or by pictures, also if put into circulation abroad, assuming that such material has been discovered in France, the persons named in Article 285, Criminal Code will be subject to prosecution provided in the preceding paragraphs under the conditions set forth in this Article, if the [offense] has been committed by means of the press. The persons known to be responsible for the issuance are also subject to prosecution, or in their absence, the chiefs of the establishments, directors or managers of enterprises having participated in the dissemination or having derived profit therefrom if the offense has been committed in any other way."

Prohibitions against advocacy, incitement or encouragement of drug use have subsequently been adopted in Austria, Switzerland, Italy, and the Netherlands.

Diversion Provisions: In General

The 1970 French Act was the first to establish a comprehensive legislative scheme for substitution of the treatment process for the criminal process. Neither of the two earlier phases of drug legislation had included such provisions in France or anywhere else. Similar schemes have subsequently been adopted in Austria (Act of June 24, 1971), the Federal Republic of Germany (Act of March 22, 1971) , and Luxembourg (Act of February 19, 1973).

The French law does not "decriminalize" drug use and remains both interventionist and coercive. First, all consumption-related behavior remains punishable as a criminal offense, under Articles L. 627 and L. 628. Second, therapeutic intervention is required for all users, regardless of the intensity of their use, either in conjunction with or in lieu of criminal prosecution or punishment ; substitution of treatment for the criminal process is referred to here as "diversion." Third, diversion is mandatory for first offenders but only permissive (in the prosecutor's or court's discretion) for recidivists (most drug offenders). Fourth, when treatment is invoked in lieu of prosecution or sentencing—by suspending the proceedings or waiving the penalty—the criminal process is suspended only conditionally; it can be reinstituted if the offender fails to conform to the conditions of the suspension.

Methods of Entry into Treatment

The basic principle is set forth in Article L. 355-14: "Any person who illegally uses substances or plants classified as narcotics will be placed under the supervision of the health authority." The act then goes on to provide three methods of entry into the treatment system: (1) voluntary entry which permits a person who applies for treatment on his own to remain anonymous ; (2) entry upon referral by a physician or a social service worker, whereupon the referred person can be ordered by the health authority to participate in a treatment program (either an addiction treatment center or under "medical supervision") ; and (3) upon referral from the criminal justice system by the public prosecutor, by the examining magistrate or by the sentencing court.

Prosecutorial Diversion

The normal charging procedure in cases involving "délit" offenses is for the police to notify the public prosecutor (procureur de la République) who has discretion not to prosecute. Although the public prosecutors are normally guided by instructions issued by the Minister of Justice, their discretion in drug cases is directed by the terms of the law itself.

Article L. 628-1 provides that a person who has been arrested for illegal use of drugs, and who is a first offender, "shall not be prosecuted if it has been determined that the person submitted himself to a treatment for drug addicts or to medical supervision" under the procedures for voluntary entry or upon referral by the medical and social services. Article L. 628-1 also authorizes the prosecutor to order a person who has been apprehended for illegal use of drugs and has not previously submitted himself to treatment under the other methods of entry, to do so.19 The prosecutor may enter such an order, in his discretion, for any user, but if he chooses to do so for a first offender and the person complies with the order and completes treatment, the offender "is not subject to prosecution."

In a judgment rendered on May 4, 1972, the criminal chamber of the appellate court (Court of Cassation) ruled that the legal effect of these diversion provisions was not to exculpate the person from criminal responsibility or to confer immunity but rather to establish grounds for termination of prosecution. Again the important point here is that the conduct for which the person was not prosecuted remains a criminal offense, and that the dismissal of charges, even when mandatory, is conditional only.

Judicial Diversion

When a person is prosecuted for a "crime" or a serious délit offense, such as drug trafficking, the normal procedure is for the prosecutor to request an examining magistrate (Juge d'Instruction) to conduct a preliminary investigation." However, not all cases must be referred to the examining magistrate by the prosecutor ; this is mandatory only in cases involving "crimes" and délits committed by minors and unidentified offenders. For less serious délit offenses, the prosecutor ordinarily takes the case directly before the competent court. This is the procedure virtually always followed for drug users against whom there is no evidence of trafficking.

In any case referred to him, a Juge d'Instruction may determine that the person is a user and that there is insufficient evidence to prosecute him for trafficking. In such cases, or in cases referred directly to the adjudging court, Article L. 628-2 of the 1970 Act authorizes the magistrate or judge, as the case may be, to order the user to submit to treatment "if it is determined that the person . . . can be cured by medical treatment." Again, the procedure established is that the court is not required to order treatment; it may sentence the person forthwith. However, if the court did order the person to submit to a treatment program and the person has completed it, the court is required to waive sentencing.

Unlike the prosecutorial provision, this diversion in lieu of sentence is not limited to first offenders. However, like prosecutorial dismissal, waiver of sentence is conditioned upon completion of treatment. The physician responsible for treatment must notify the court of the "development of the treatment and its results." The law also provides that if the person "evades execution of a decision ordering treatment," he must be punished and sentenced even if he is ordered to participate in the treatment program again.

Summary

To summarize, a person who has been arrested for drug use (at least for the first time) may avoid any formal process, and any attendant stigma, simply by reporting on his own to a treatment program. Once the prosecutor has been so notified, and the person has completed the prescribed treatment, the prosecution must be waived. If, on the other hand, the person has not submitted to treatment on his own, the prosecutor's office may order the treatment; this process will generate official records, may carry some stigma, and is clearly coercive, but criminal prosecution must likewise be waived if the person satisfactorily completes the program. For persons prosecuted, the adjudging court is authorized to substitute a compulsory treatment order for criminal sentencing. This procedure, although equally coercive, would avoid a criminal penalty. Again, however, a sentence will be imposed if the offender is unwilling to conform to the treatment order.

Application of the 1970 Act to Users

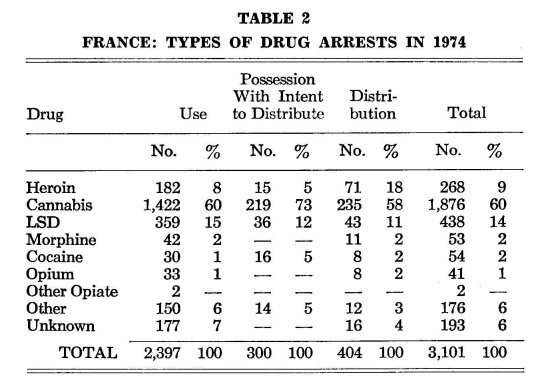

Table 2 shows that more than 3,000 persons were arrested for drug-related offenses in 1974 and that more than three-fourths of those persons were arrested for "use." Although drug arrestees may, in theory, be detained, preventively, for up to four days after arrest,21 persons arrested primarily for use are, according to informed observers, routinely released after arrest. Although recent data are not available regarding prosecutorial and judicial dispositions, 1973 data show that of the 1,786 persons reported by the police for use of drugs, 13 percent of the persons had their cases filed without further action and 27 percent were ordered to report to the health authorities in lieu of prosecution. Assuming that the 13 percent "not filed" figure represents only cases in which prosecution was withheld because the person had submitted to treatment on his own, six cases in ten were still prosecuted. Does this figure represent recidivists alone?

No sentencing data were available at all but informed observers indicated that recidivist users are rarely sentenced to imprisonment except in exceptional cases of flaunting the court's authority. Also, fines or suspended sentences are routinely imposed on persons who fail to fulfill the conditions of treatment.

Two important practical questions are raised by the diversion scheme. First, the Act draws a clear line between users and traffickers. Only persons apprehended for violations of Article L. 628 (use) are eligible for diversion ; if there is evidence of dealing, the "repressive" measures of Article L. 627 are to be used. Second, the Act draws no distinction among users and employs the "medical model" of therapeutic intervention for all persons arrested for consumption-related behavior. Neither legal principle conforms well to the empirical realities of drug-using behavior or the drug trade.

The User/Dealer Problem

Many French observers have pointed out the user/dealer problem. Some, especially those associated with the judicial system, argue that many dealers are escaping punishment under the diversion provisions. Others, in the health profession, emphasize that many dealers are drug-dependent and could benefit from medical intervention. The question is thus posed. Should the basic diversion concept be utilized in cases involving consumption-related trafficking ; or should the distinction be drawn clearly and cleanly between an apprehension for use and an apprehension for dealing. Under the former approach, the law would aim to distinguish between commercial trafficking and consumption-related trafficking. A criminal code reform committee composed of ten distinguished members of the bench and bar attempted to formulate such a provision recently but concluded instead that it was best to leave the basic distinction between use and other offenses alone and to rely on the exercise of prosecutorial discretion ("the principle of opportunity") to draw the appropriate line in individual cases. Available data simply do not indicate how the prosecutors and courts are responding to this problem at the present time.

Users Who Are Not "Sick"

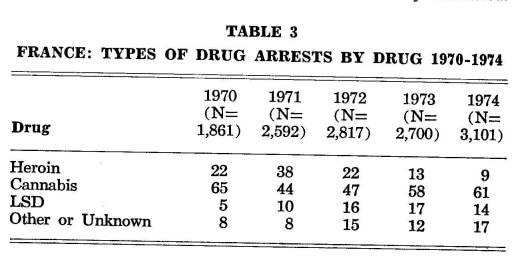

The other practical question concerns the applicability of the therapeutic control model to all users. Table 2 shows that 60 percent of those arrested for use in 1974 (representing almost half-46 percent—of the total number of arrestees) were arrested for use of cannabis. Conversely, the proportion arrested for opiate offenses is less than 10 percent. Table 3 shows that while the number of arrests has increased slowly since 1971, the proportion of heroin cases has slowly decreased while the proportion of cannabis cases has slowly increased.

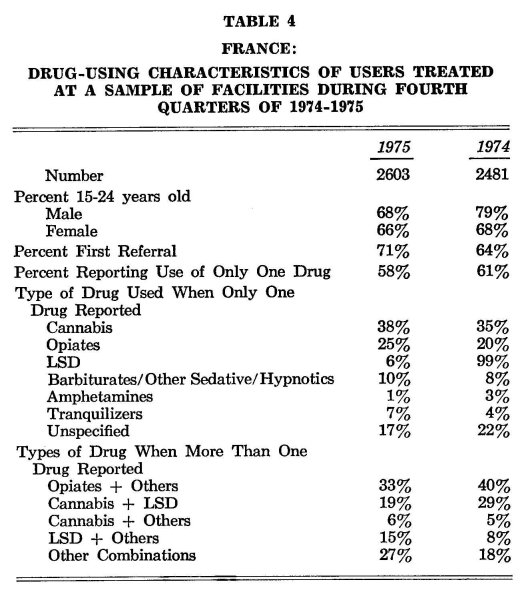

These figures should be compared with those in Table 4 which reports the results of an inquiry by the Director General of the Department of Health regarding the characteristics of persons enrolled in treatment programs in the last quarters of 1974 and 1975. Data show that about 2,500 users were reporting to the treatment facilities during these survey periods, a far greater number than the persons arrested for drug offenses. This indicates that large numbers of persons were entering these programs voluntarily or on referral from physicians or social service establishments, without having been arrested and referred for prosecution. On the other hand, the data also show that more than one-third of these patients were being treated in connection with their use of cannabis. Similarly, among the polydrug users (approximately 4 of every 10 subjects), another quarter or so were being treated in connection only with their use of cannabis and drugs other than opiates.

Taken together, these arrest and treatment data suggest that a large segment of the treatment program clientele may be cannabis users who are being referred by the criminal justice system even though the "medical model" is not appropriate. This is one aspect of the new law which merits continued scrutiny. The Act's diversion scheme imposes the "medical model" of coercive therapeutic intervention on the entire class of persons arrested for consumption-related behavior. Although French officials do not readily acknowledge it, there can be little doubt that experimentation with cannabis and hallucinogens has increased and that a growing number of adolescents and young adults use cannabis recreationally. Many of these persons do not need treatment. It will be interesting to see how the French respond to this problem as it becomes more visible.

ITALY

Italy's drug laws were completely revised by the Act of December 22, 1975. The comprehensiveness of the new law is reflected in the coverage of its various subdivisions. The regulatory and administrative provisions appear in Titles I through VII. Title VIII deals primarily with penal measures, Title IX provides for "Information and Education Measures," Title X establishes and describes the functions of "Medical and Social Welfare Centers" and Title XI contains highly detailed provisions on "Preventive, Curative and Rehabilitative Measures."

In general, the Act increases the penalties for trafficking offenses, facilitates the development of "prevention and treatment" programs, and emphasizes non-penal measures for dealing with consumers. A statutory declaration that possession of small quantities of drugs for personal use is "not punishable" is supplemented by an integrated and detailed set of provisions for referral to medical and social service programs. Thus the law remains interventionist, albeit non-penal and less coercive.

Background

Italy's predecessor narcotic law (Act of 1954) had been enacted mainly in response to international pressures related to the flow of international narcotic traffic through Italy. Informed sources indicate that the lawmakers were not, at that time, responding to any perceived domestic drug abuse problem. Under Article 6 of the Act of 1954, "use" was not an offense but all other drug-related behavior, including "simple" possession, was punishable by the same penalty—imprisonment for not less than three or more than 8 years and by a fine of not less than 30,000 lire or more than 4,000,000 lire. The applicability of this penalty to possession for personal use was upheld by the constitutional court in 1973.

Beginning during the late 1960's, as the domestic use of illicit drugs was perceived to increase, experts in the medical community began to press for legislative reforms to distinguish between users and traffickers. Although the reform movement won much popular backing, it got nowhere until 1970, when the Minister of Interior (who controls the national police) endorsed the idea of reform. Subsequently, the government sponsored one of the many reform bills introduced in the Parliament in 1970. Although a consensus emerged quickly regarding the desirability of increasing trafficking penalties, expanding the scope of regulatory control and abandoning the "repressive" approach toward the user,22 the ensuing debate focussed primarily on the type of approach which should be substituted for the discredited one.

By 1974 the only unresolved question was how to structure a system which offered the possibility of intervening and, if necessary, controlling the user without punishing him. It is clear that the government wanted to avoid penal measures but also wanted to maintain a structure of intervention. Consideration was given to the "French solution," but this was regarded as too coercive. Instead, the drafters settled on a unique form of depenalization combined with the "substitution of non-penal modes of assistance and compulsory treatments."23

Penal Provisions of the 1975 Act

The Italian law employs several unique substantive devices to distinguish among and determine the relative severity of penalties for drug offenses. Article 71 prescribes severe penalties for production, distribution, purchase, and possession (not use) of all drugs, although it differentiates between 2 classes of drugs. Article 74 provides for aggravation of penalties for violations of Article 71 if defined circumstances are proven. Then Articles 72 and 80 carve out two exceptions from the generally applicable penalties of Article 71; in essence Article 72 deals with retail distribution of small amounts and Article 80 deals with personal consumption-related behavior. The net effect is that retail distribution of small amounts is punishable by less severe penalties than the major trafficking penalized by Article 71 and consumption-related behavior is not punishable.

Trafficking : Presumptive Penalties

Article 71 provides that importation, exportation, production, distribution, purchase and possession of Schedule I drugs (opiates, cocaine, amphetamines, hallucinogens) and Schedule III drugs (barbiturates) are punishable by imprisonment from four to fifteen years and by a maximum fine of 100 million lire, and that similar acts involving Schedule II drugs (cannabis) and Schedule IV drugs (other medically used drugs, mainly tranquilizers) are punishable by imprisonment from 2 to 6 years and by a maximum fine of 50 million lire.

Trafficking : Aggravation

Article 74 provides that the penalties prescribed in Article 71 "shall be increased by no less than one third or more than one half" if the recipient is a minor, if the offender was armed and in other specified circumstances. The Article provides for even more severe aggravation (penalty increases of not less than one-half or no more than two-thirds) if the offense "involves very large quantities" or if weapons were used in the commission of the offense.

Trafficking : Small Amounts

Article 72 provides for lesser penalties for possessing, offering, acquiring, selling, transporting or distributing "small (modiche) amounts" of drugs "for the personal, non-therapeutic use of third persons." If the offense involved Schedule I or III drugs it is punishable by imprisonment from two to six years and by a maximum fine of 8 million lire, and if it involved Schedule II or IV drugs, it is punishable by imprisonment from one to four years and by a maximum fine of 6 million lire.

Consumption-Related Behavior

Article 80 provides as follows :

Any person who illicitly acquires or in any way possesses any [narcotic drug or psychotropic substance] for the purpose of his own personal therapeutic use is not liable to punishment provided that the quantity of the substance possessed does not exceed, in any appreciable way, that necessary for the person's treatment in light of his particular medical condition.

Similarly, any person who illicitly acquires or in any way possesses small (modiche) quantities of [any narcotic drug or psychotropic substance] for his own personal nonmedical use, or who has in any way possessed these substances and has made exclusively personal use of them, is not liable to punishment.

• • •

In every case the provisions of title XI shall be applicable.24

Although most of this report will be concerned with the meaning and application of this provision, several points should be highlighted immediately. First, use of drugs and the antecedent acts of acquisition and possession of small amounts are formally de-penalized. They are not punishable acts. Second, the Act does require a formal record of the determination of non-punishability and a referral to an appropriate medical or social service agency (these are the provisions of Title XI, to be described below). However, separate legal measures are provided to coerce treatment if this is regarded as necessary—but the coercive devices are not tied back to the criminal process which has been terminated because the offense is not punishable. Third, depenalization implies the absence of punishment and formal sanctions, but not the absence of intervention : the person is subject to apprehension, his case is recorded and presented to a magistrate who determines whether his acts are punishable and his involvement with drugs is also brought to the attention of health and welfare authorities. Thus, even though the offense is not punishable, the criminal process is used as a "detection" device to facilitate, but not coerce, the delivery of any required services to the drug-using population.

The next section will describe, in detail, the duties which link the criminal process to the medical and social service system. Before doing so, however, several other penal provisions should be noted.

Other Penal Provisions

One of the interesting features of the new Italian law appears in Article 82, which imposes an obligation to testify on "any persons who have been declared not liable to punishment for having acted in the manner referred to in Article 80." Such persons are required to "give evidence as witnesses in proceedings concerning facts which in any way whatever may lead to the identification of criminals or criminal organizations which illicitly produce, manufacture, import, export, sell or otherwise transfer or possess narcotic drugs or psychotropic substances." Apparently, during the initial phases of enforcing the new law, little information was being divulged by the users processed under Article 80; the police spokesman speculated that this was due to the continuing effect of past relationships between users and dealers which have always inhibited the task of obtaining information. On the other hand, he indicated that these relationships were being loosened as users have become aware of the benefit available to them under Article 80. According to this spokesman, the results of Article 82 are now becoming visible in enforcement and investigative successes.

Another interesting feature of the new law is its provision for administrative measures above and beyond penal sanctions for trafficking behavior. Article 79, modeled after a similar French provision, authorizes judges to preclude an offender from leaving the country for a period up to three years and to revoke his driver's license for the same period. No data are available on the use and impact of these sanctions.

Finally it is also noteworthy that the Italian law, like the French, Austrian, Swiss, and Dutch laws, also includes a provision penalizing the "encouragement" of drug use. Article 76 penalizes "inducing a person to make illicit use of drugs," or "engaging, in public private, activities aimed at promoting" illicit drug use. The penalties vary according to whether the drug is in Schedules I and III or II and IV and the penalties are aggravated if the act prejudices minors.25

Linkage Between Criminal Process and Treatment and Social Services

The regional governments are directed to organize and coordinate the drug abuse prevention and treatment activities of hospitals, clinics, medical specialists, and social service agencies. In doing so they are directed to establish a coordinating committee and to create at least one "medical and social welfare center" to receive initial referrals and perform diagnostic, treatment, referral, and liaison functions. (Title X) . Treatment and other services may be initiated upon voluntary, anonymous application, upon referral by physicians and other health workers as well as by referral from the criminal justice system.

Articles 96-101 include a detailed and integrated set of provisions concerning the relationship between the criminal justice system and the therapeutic and social service system to be established under Article X.

The Police

Under Article 96, the police are directed to "inform the nearest of the [medical and social welfare] centers and the local magistrate of all cases coming to their attention of persons who use narcotic drugs or psychotropic substances for non-medical purposes in order that they may, if necessary, take such action as lies within their competence." Similarly Article 98 provides that if the police "learn of one of the acts referred to in Article 80" they "shall bring it to the attention of the magistrate." It should be emphasized that police are thereby mandated (a) to invoke the criminal process and (b) to initiate the referral process, in all cases involving drug users. Article 96 also requires the police to "accompany to the nearest health office any person who may be found in a state of acute intoxication presumed to result from the use of" drugs. This provision is similar to that found in many state laws in the United States concerning the police "protective function" in cases involving public intoxication by alcohol or controlled substances.26

Magistrates

Articles 96-101 go on to specify the procedures to be used by magistrates in cases brought to their attention by the police. If the magistrate concludes that the conditions of Article 80 are met and that the offense is, therefore, not punishable, he is required to give "his opinion concerning any medical treatment and assistance it may be necessary to give to the person concerned" and "declare that [criminal] proceedings must not continue."27 He is also directed to "transmit a copy of the decision to a [medical and social welfare] center in the locality where the discharged offender resides, in order that the center may take such action as lies within its competence."26 If the person needs "emergency" treatment, the magistrate is directed to initiate the commitment process specified in Article 100.29

Non-Cooperation

The underlying premise of these provisions is that the "non-punishable" user will voluntarily report to the medical and social welfare center and will undergo whatever treatment is prescribed. Articles 97, 99, and 100 establish the procedures to be invoked if the person does not do so. Article 97 provides :

Any medical and social assistance centre receiving a notification as referred to in Article 96 above and having ascertained that the person who is the subject of the notification has not voluntarily undergone therapeutic and rehabilitative treatment, shall invite him to do so, indicating the most suitable means. Should the person refuse, the centre shall bring this fact to the attention of the local magistrate solely for the purposes of the provisions of Articles 99 and 100. A similar notification shall be made if the person concerned voluntarily interrupts medical or social treatment of which he is still in need, if such interruption may prejudice the treatment being given.

It should be emphasized here that the medical and social service personnel are not required to notify the magistrate of interruption of treatment unless this interruption will "prejudice" treatment of which the person is "in need." This principle is re-emphasized in Article 100 which provides for a type of "civil commitment" process" which is conducted not by the criminal court but by a "specialized division of the civil court :"

The police authority or the competent medical and social welfare centre shall notify the judicial authority of any person indulging in the use of narcotic drugs or psychotropic substances who is in need of medical care and assistance but refuses to undergo the necessary treatment.

A similar notification may be made by the parents, spouse, children or, in their absence, close relatives of the person to be assisted.

Whenever the judicial authority perceives the need for medical treatment and assistance, it shall, after the necessary verifications having been made and, in every case, after the person concerned and the competent medical and social welfare centre have been heard, make an order for the admission of the person concerned to a hospital, other than a psychiatric hospital, if this is absolutely necessary, or for appropriate out-patient or home treatment. In every case, the judicial authority shall place the person to be assisted in the charge of the centre referred to in Article 90, which shall take the necessary action and report thereon at least every three months to the said authority.

The person concerned shall be placed in the charge of the centre for the presumed duration of the treatment and assistance necessary for his social reintegration.

If, when medical treatment as an out-patient has been ordered, the person concerned interrupts the treatment and refuses to resume it, the judicial authority may order his admission to a suitable hospital, other than a psychiatric hospital.

The measures indicated in the preceding articles may be modified at any time. They shall be revoked as soon as it is possible to assume that the person concerned is no longer in need of care and assistance.

Again, it should be emphasized that after the initial referral to the treatment system from the criminal system under Article 80, the criminal proceedings are terminated. Unlike in France, Austria and other states with "diversion" schemes, pending criminal charges (for use or simple possession) are not used to induce or coerce participation. Instead the traditional "mental illness commitment" model is employed. Only if the person needs treatment is a judicial order possible, and only if hospitalization is "absolutely necessary" for his treatment is such an order permissible. By using such a legal framework, the Italian law distinguishes clearly between cases where the "medical model" provides an appropriate basis for coercive intervention and cases where it does not. In diversion schemes which link participation in treatment programs to criminal possession/use charges, such a distinction is not drawn.

Treatment as an Adjunct to Punishment

One other provision should be noted. Article 96 also addresses situations where drug users have been convicted of an offense, either under Articles 71 or 72 or other criminal provisions, but are not sentenced to imprisonment. In such cases, the judge is required to initiate the drug-abuse treatment process :

A judge who pronounces a conviction in the case of a person who uses narcotic drugs or psychotropic substances for non-medical purposes shall, if he orders conditional suspension of sentence, order that the judgment be communicated to a [medical and social welfare] center in order that the center may take such action as lies within its competence.

Determinations under Article 80

Article 80 employs the technique of purposeful ambiguity. Rather than specifying the meaning of "small quantities," the Parliament, in effect, decided to delegate to the courts the responsibility for defining the line between criminal and noncriminal behavior. All observers agree that the Parliament contemplated that the judiciary would decide on a case-by-case basis, making an individualized determination, based on the report by the police and, in some cases, the testimony of experts.

However, when the police apprehend a person whom they believe is a user, and from whom they have seized a quantity of prohibited drugs consistent with this belief, they must themselves make a preliminary determination whether or not a "small amount" is involved and whether the person was holding it for personal use. If an Article 80 determination is anticipated, a summons will be issued, the person will be released and a report will be filed with the magistrate. On the other hand if the person is considered to be a dealer or if the amount is not considered to be small, he will be arrested and his case will be referred to the public prosecutor. Eventually, if the magistrate does not agree with the preliminary police determination that Article 80 is applicable, the normal criminal process will be invoked and the violator will be arrested and jailed. On the other hand, if the magistrate ultimately concludes that Article 80 is applicable to a case in which the offender had been arrested, release will be ordered.

At present there are apparently no formal guidelines to assist the police to make the preliminary "small amount" decision. Police officials emphasize the complexity of this determination which, they contend, depends on many extrinsic factors in individual cases ; but the crucial point seems to be that they feel constrained by their impression of the Parliament's intent—this is a decision for magistrates, not for the police. It is possible that the street decisions can, over time, be guided by the practice of the magistrates themselves, but no patterns seem yet to have emerged. Thus police practice undoubtedly varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction and from officer to officer. In the absence of any guidelines, one can infer that the law has no uniform meaning at the present time. As inequalities from jurisdiction to jurisdiction (or magistrate to magistrate) become apparent, recourse to the Supreme Court can be anticipated.

The official statistics of the DAD, the central narcotics enforcement agency, indicate that 1,164 persons were brought to the attention of the magistrate in 1976 because they had possessed small quantities of drugs for personal use. This figure represents approximately one-third of the 3,551 "denunciations"—the number of persons charged for violations of the drug laws. The remaining 2,387 persons were charged with trafficking, sale, and other crimes, and 1,675 of these persons were actually arrested for these violations. These data are not apportioned by drug type and the statistics regarding referral under Article 80 do not indicate which drugs had been possessed. However, the general impression of a spokesman from the drug enforcement agency was that the major proportion of the persons who are brought to the attention of the magistrate under Article 80 are heroin addicts. This would suggest that even though a summons and a report is mandatory in all cases of detected violations, the police must be ignoring many detected violations, especially those involving cannabis. Several university students indicated that the police frequently ignore overt cannabis use and even if the drugs are seized no report is made if the amount is unequivocably small—e.g., 10 grams.

In any event, once a case is referred to the magistrate, the statute appears to contemplate that a full evidentiary proceeding will be held in all cases to determine the applicability of Article 80:

The magistrate, when the necessary information has been gathered, shall entrust an expert having specific competence in the matter with the task of determining whether the conditions for non-punishability stated in the first two paragraphs of Article 80 exist and of giving his opinion concerning any medical treatment and assistance it may be necessary to give to the person concerned. The technical verification must be based mainly on the toxic properties of the substances possessed by the person concerned, having regard to his physical and psychical personality.

The magistrate, having ascertained the existence of one of the grounds for non-punishability, shall declare that proceedings must not continue.

In the opposite case, he shall transmit the documents to the competent public prosecutor.

Despite the mandatory statutory language, it appears unlikely that an evidentiary hearing is needed when, as in many cases, the amount is so small that it speaks for itself. It seems safe to assume that the magistrate makes his determination on the basis of the police record in some cases, although this suspicion has not been confirmed. In any event, if a hearing is held, Article 98 provides that the issues to be resolved are forensic in nature and require expert testimony. For example, a defense witness who is expert in the treatment of drug dependence may testify that the three grams of heroin seized was, in light of its purity and the defendant's tolerance, equivalent to a three days' supply of one gram per day. One forensic expert indicated that most magistrates have developed rules of thumb which vary significantly (e.g., 2 grams to 10 grams) from court to court.

In summary, neither the drug enforcement authority, nor the Ministry of Justice has issued any guidelines as to the meaning of "small amounts." Nor has the law been in effect long enough either for any patterns of magistrate and judicial behavior to become visible or for the appellate courts to have become involved. At the present time, only a survey of local attorneys and magistrates could be expected to provide information regarding current practices.

Some Perceived Problems

Italian officials and experts have pointed out features of the law which have generated difficulties in implementation. The first is the generic problem of distinguishing "correctly" between possession for personal use and possession with intent to distribute. One judicial expert pointed out that many retail dealers were undoubtedly carrying only "small amounts" at any given time to assure that their conduct appears to be nonpunishable under Article 80 if they are detected.3' Of course, if the police have adequate extrinsic evidence of trafficking, the fact that the amount seized was small does not preclude prosecution under Articles 72 or 71. It is interesting, in this connection, that the DAD official did not raise this problem. In fact enforcement efforts have been substantially more productive since the new law went into effect.

Enforcement data clearly show that the police have devoted more attention to trafficking and especially heroin since the new law established a drug enforcement agency (DAD) to coordinate the activities of the three national police forces. A DAD spokesman indicated that even before the new law was passed, a consensus had emerged regarding the inappropriateness of incarcerating users and that the police had already adopted a passive approach toward the enforcement of the consumption-prohibitions. Nonetheless a comparison of 1975 and 1976 seizure data is instructive. While the police seized 13,634 kilograms of heroin in 1975, this figure rose to 75,763 in 1976. Similarly, the seizures of cannabis and its derivatives also increased considerably, and in fact doubled from 763,397 kilograms in 1975 to 1,482,179 kilograms in 1976.

Another concern about the law involves the line between the consumption-related behavior which is not punishable under Article 80 and the commercial behavior which is punishable under Articles 71 and 72. All observers emphasized the well-known fact that most addicts also engage in retail dealing to some extent as a means of financing their own habits. On the face of the law, Parliament has provided that the addicted dealer is subject to the full rigors of the criminal process. Although the sanction is less severe for "small" dealers than for commercial traffickers (another judgment which the magistrate must make on a case-by-case basis), incarceration is the prescribed penalty for "small" dealing under Article 72 and defense attorneys have begun to utilize various legal devices to mitigate the penalty in such cases (e.g., partial responsibility arising from "chronic intoxication"). Of course, this is not a difficulty unique to the Italian law. Drawing a line between use and consumption-related trafficking is a generic problem.

Another problem with implementing the law concerns the recalcitrant patient. One treatment expert estimated that the dropout rate in the public treatment centers was between 40 percent and 50 percent. As in the treatment of mental illness, there are inherent limits to the capacity of the "commitment" process to intervene if a patient drops from an outpatient program. Some experts are apparently arguing that the criminal process should be reinstated in such cases—that in effect the offense should be "punishable" and that the law, as in France, should only establish a "diversion" process. Others are arguing that it is impossible to compel a "cure" in any event and that penalization is not a suitable alternative to a voluntary treatment strategy. This issue is currently unresolved.

At present the major difficulty in administering the law is that the medical and social welfare centers, and the associated treatment programs, which the Parliament contemplated as alternative means of social intervention, are not yet available. The 1975 law regionalized the responsibility for drug abuse (and alcohol) treatment, directing regional committees to establish treatment and prevention programs. Ultimately the Ministry of Health is required to create the clinical facilities if the regional committees fail to do so. All observers emphasized that regional facilities are in widely varying stages of development during this transitional phase. Police officials who are sympathetic to the guiding philosophy of the law nonetheless emphasized that it is difficult to withdraw the criminal enforcement apparatus when the therapeutic alternative has not been adequately established.

Summary: The Meaning of Decriminalization in, Italy

The major innovation in the Italian law is the substitution of non-penal measures under Title XI for criminal punishment. The key provision is Article 80. Under this provision the criminal process must be initiated against any person apprehended for possession or use of prohibited drugs. If the magistrate determines that the person did not possess the substance for his own use or possessed more than a small amount, he is expected to order the person arrested and to notify the prosecutor for initiation of the customary criminal process. Only when a magistrate (or a judge) has determined, in a given case, that the amount seized was small and was possessed for the person's own use, can it be said that the person's conduct was not a "crime" and hence, not punishable. From this point, the person's involvement in the criminal process has no legal effect. Although the criminal charge provides the legal device for notification. of the medical and social service authorities, any subsequent coercive intervention must be based on the legal principles which govern civil commitment.

Because criminal sanctions are not imposed regardless of the outcome of the treatment process, it is reasonable and accurate to characterize the Italian scheme as having "decriminalized" consumption-related behavior. On the other hand, this conduct is not entirely immune from penal consequence. First, the person's apprehension is formally documented in a police record which is accessible to the police and may be accessible to third parties. Second, although the person is not the subject of a criminal judicial record in the ordinary sense, there will be an official record of the proceedings. Third, the person's involvement in the criminal process is, in every case, brought to the attention of the medical and social service system. Fourth, the person is not immune from any formal legal intervention arising out of his relationship with the medical and social service center.

These "derivative" consequences of apprehension do have "penalizing" effects, hence, presumably, they have preventive and deterrent value. Thus, the Italian scheme represents a unique and creative effort to implement a policy of "discouragement without criminalization." Moreover by employing the criminal process as a device for detecting users of illicit drugs and assessing their need for treatment, the law also represents a unique effort to achieve outreach while minimizing coercion. Both aspects of the Italian scheme merit continuing study and consideration.

SWITZERLAND

Major revisions to the Swiss Narcotics Law of October 3, 1951 were adopted on March 20, 1975. In general, these modifications increased the penalties for trafficking, reduced and substantially modified the penalties for consumption-related offenses, and revised the basic legal contours of the process of treating drug-dependent persons.

Background

The process which culminated in the enactment of these revisions began in 1968 when the government proposed a series of amendments in connection with ratification of the Single Convention (which was ultimately accomplished on January 23, 1970) . After these amendments were enacted and in anticipation of the amending protocols to the Single Convention, the Narcotic Commission, an interdepartmental agency of the Swiss government, initiated a prolonged process of reassessment and revision in December 1970. The lead agency in the drafting process was the Pharmaceutical Division of the Public Hygiene Service, which submitted a first draft to the Commission in December 1971. The Narcotic Division completed its draft in November of 1972 and submitted the proposed legislation for comment to the cantonal authorities and 18 private interest groups, including the pharmacists, physicians, and pharmaceutical companies. After these comments were received, a final draft was presented by the Secretary of Health to the full cabinet, and the government presented the bill to the Parliament in its message of May 9, 1973.32

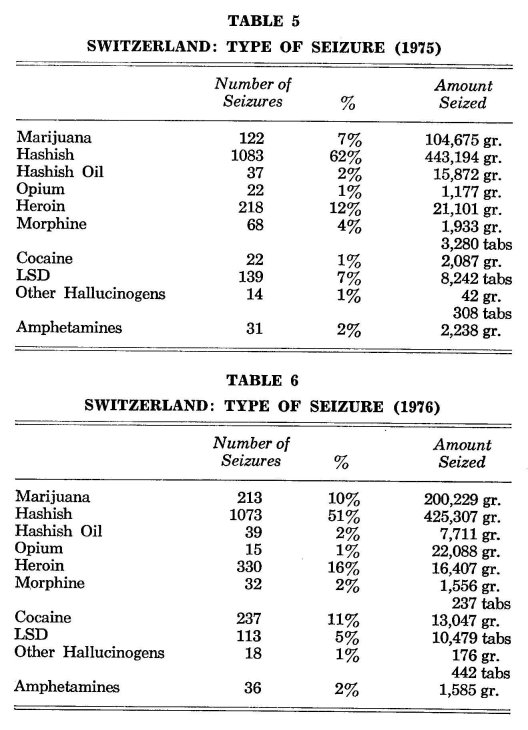

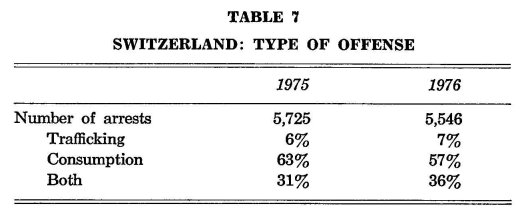

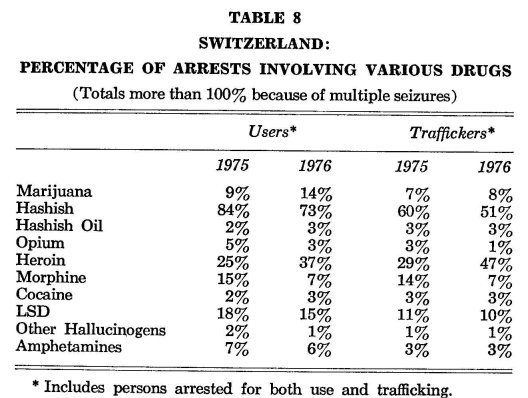

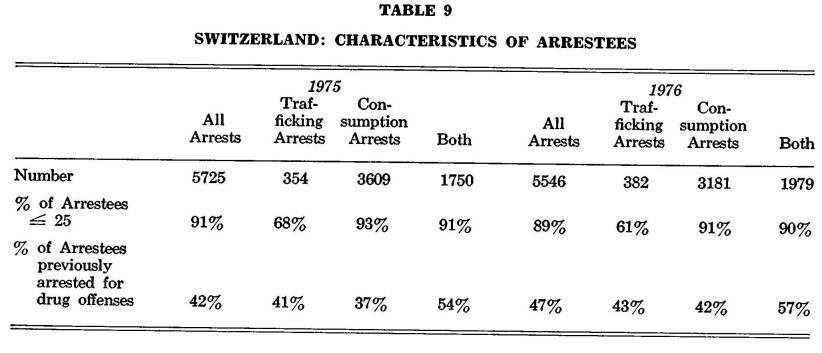

As was true in most European countries, data concerning the incidence and patterns of illicit drug use in Switzerland are sketchy and impressionistic. Apart from an old two-year study based on Armed Forces entrance exams and a few doctoral dissertations, there are few sources of hard information.33 However, based on seizure patterns and clinical reports, informed observers believe that illicit drug use has increased considerably in the last several years. Hashish is the most widely used illegal drug but opiate use is increasing. The Public Hygiene Service estimates that there are some 20,000 drug-dependent persons in Switzerland ; this figure includes persons heavily involved with all illicit drugs (all classified as "narcotics" under the law) . Heroin addiction is thought to have tripled since 1971, now approximating 13,000 addicts.34 The Swiss authorities estimate that 650,000 Swiss francs ($260,000) are spent on illicit drugs daily. Swiss experts have concluded that their patterns of drug abuse lag about one to three years behind those which emerge in the United States, although on a considerably smaller scale.

Penal Provisions of the 1975 Act

As indicated earlier, the 1975 law completely revised the penal provisions concerning both trafficking and consumption-related offenses. In contrast to the laws of many other countries, including the United States, Great Britain, and Italy, the penal provisions are not in any way linked to the regulatory classification of the drug. All controlled substances are classified as "narcotics"—this includes the opiates, cocaine, cannabis, hallucinogens, and amphetamines ; barbiturates are not controlled.33 Under the penal provisions (Article 19) the sole device for "grading" offenses is the seriousness of the offender's conduct, not the characteristics of the drug.

Penal Sanctions Under Swiss Law

As in France, offenses are generally classified into crimes, délits, and contraventions. Generally speaking, the distinction between crimes and délits appears to have little legal significance, since the penalties differ only slightly and the record-consequences do not seem to differ at all. They both refer to serious criminal offenses in Anglo-American terminology. In contrast, contraventions resemble "civil" offenses and are generally employed in connection with federal regulatory offenses and with cantonal offenses such as illegal parking.36

The basic distinctions in Swiss penal law are drawn according to the types of penalties available upon conviction ("condamnation") . Deprivations of liberty are classified as réclusion, imprisonment, and arrêts, which are defined by Articles 35-39 of the Penal Code. "Réclusion," the most grave penalty involving deprivation of liberty, is served under the most rigorous conditions and may be ordered for not less than one year or more than twenty years. "Imprisonment," in contrast, may be imposed from a minimum of three days to a maximum of three years, unless the particular substantive law provides otherwise.37

The least severe penalty involving deprivation of liberty is the "arrêts" which may be imposed for any length of time between one day and three months. Article 39 of the Penal Code specifically provides that if the substantive law authorizes either imprisonment or a fine, the judge may impose detention by arrêts, the intermediate sanction. The distinction between detention by arrêts and imprisonment is a crucial one. The detention by arrêts must be served in local special institutions (similar to jails) where confinement need not be continuous ; offenders are authorized to be released for continuation of employment, spending only nights and weekends in detention.

Generally speaking, contraventions are usually punishable only by fine, though detention by arrêts is also possible in some cases. Délits and "crimes" are usually punishable by imprisonment or réclusion, although such sanctions are usually not mandatory. Another crucial distinction between contraventions on the one hand and crimes or délit offenses on the other pertains to their respective implications for the criminal record system. Any conviction for a crime or délit must be reported to the cantonal and federal record bureaus, regardless of the gravity of the penalty actually inflicted. However, contraventional violations of cantonal ordinances need not be reported at all and contraventional violations of the Swiss Penal Code or other federal laws need not be reported unless they involve the imposition of a penalty of arrêts or a fine of more than 200 Swiss francs ($80).38

Trafficking Provisions

Under the old law consumption and trafficking offenses were not distinguished in terms of penalty: all offenses were punishable by "imprisonment" for up to two years and by a fine of up to 30,000 Swiss francs ; in "grave case" cases (involving "dessein de lucre") "réclusion" for up to five years was permitted.

Under the new provisions, as they appear in paragraph 1 of Article 19, the maximum penalty for the ordinary trafficking offense is three years' imprisonment and/or 40,000 Swiss francs." However, the new law increases the penalty for "grave" offenses to a mandatory minimum sentence of one year of réclusion or imprisonment and increases the maximum penalties to 20 years' réclusion and/or a fine of 1,000,000 Swiss francs. This is the heaviest penalty authorized by Swiss law for any offense.

Paragraph 2 of Article 19 enumerates grave cases by way of example, not by definition, indicating that the types of cases contemplated are those (a) involving a large enough quantity that the offender must have known that his act put many people in danger or (b) involving organized trafficking, or (c) involving "professionals" who aim for a large volume of sales or a considerable profit. It is notable, in this connection, that the definition of a grave offense, and therefore applicability of the more serious penalty, is entirely within the discretion of the courts ; even these illustrative concepts demand judicial interpretation of the law as well as factual determinations in particular cases.

Consumption Provisions : Background

Under the old law, the acts of possessing, having within one's control, buying or otherwise acquiring proscribed drugs were all prohibited and, on the face of the law at least, were punishable by the same penalties as the trafficking offenses of offering, distributing, selling, etc. However, the act of using or consuming was not a punishable act. Although this may not seem to be an important point to those acquainted with Anglo-American criminal law, it has a crucial significance for understanding the evolution of the consumption-related provisions of the new Swiss law.

Under Anglo-American drug laws, the act of possessing the drug, even for one's own use, has traditionally been an offense under all state and federal drug laws at least since the 1930's. While the act of use, in itself, may or may not have been an offense, this was generally not relevant to the meaning of the term "possession." That is to say, a person who has used the drug has also possessed it and acquired it previously. Thus the act of use also establishes the act of possession. (If both acts are prohibited, the offender could probably be charged with both of them, although the lesser "offense" may have been "included in" and merged with the greater offense under the jurisprudence of an individual jurisdiction.) And the act of possession is an offense regardless of whether the person intended to use it himself or pass it on to someone else.

Under the terms of the old Swiss law, as indicated earlier, the acts of possessing, having, buying or otherwise acquiring were all punishable acts, regardless of the intention of the actor. Yet, it was argued that in light of the fact that the act of consuming or using was not an offense, a person who was apprehended while in the act of using could not be punished for the previous acts, which had then ceased, of acquiring, having or possessing the drug. In other words, because consumption was not, in itself, punishable, the law did not permit the user to be punished for the antecedent illicit acts. The federal Supreme Court rejected this argument in 1968, holding that the consumer did not become immune from prosecution for his previous offenses simply because consumption was not a punishable act. In the case before it, the court upheld the conviction of a young man who accepted ("acquired") a marijuana cigarette purely for smoking after it had been prepared by someone else. Although it might seem perfectly acceptable under Anglo-American jurisprudence for such a conviction to stand, the Swiss Supreme Court was charged with hypocrisy for having distorted the definitions of the punished conduct.

This decision necessitated at least some change in the law ; all agreed that the consumer should not be punishable by a two-year term of imprisonment, which was the consequence of the court's ruling. But there was no agreement about what should be put in its place. Some argued that the user should be entirely "decriminalized"—that use and all the antecedent acts intended for personal use should not be punishable offenses, and entirely non-penal measures should be substituted to deal with those in need of treatment. Others, especially the police, insisted that most users were also dealers and that decriminalization of consumption-related behavior would inhibit the enforcement of Article 19 against traffickers by opening large loopholes.40 The result was a compromise41 —a substantial reduction in maximum penalties for any consumption-related behavior, specific authorization for a variety of non-punitive dispositions and, apparently, a full decriminalization of offenses involving insignificant amounts. The reasons for the use of this qualifier ("apparently") will become clear below.

Article 19a

Article 19a provides :

1. Any person who intentionally consumes drugs without lawful authority or any person who has violated Article 19 to assure his own use is liable to punishment by arrêts or by a fine.

2. In benign (minor) cases, the competent authority may suspend the proceedings or waive the imposition of a penalty. A reprimand (warning) may be pronounced.

3. It is possible to waive the criminal process whenever the offender has already submitted to treatment for drug use or if he agrees to do so. The criminal process may be reinstituted if he interrupts the treatment.

4. Whenever the offender is drug dependent, the judge may order him to be hospitalized. Article 44 of the penal code is applicable by analogy.