CHAPTER FOUR IBOGAINE AND THE VINE OF SOULS: FROM TROPICAL FOREST RITUAL TO PSYCHOTHERAPY

| Books - Hallucinogens and Culture |

Drug Abuse

CHAPTER FOUR: IBOGAINE AND THE VINE OF SOULS: FROM TROPICAL FOREST RITUAL TO PSYCHOTHERAPY

Naranjo's application of psychedelics to mental therapy at this point provides a convenient pharmacological bridge for us, from the numerically small though significant non-nitrogenous substances to the infinitely more numerous and culture-historically more dramatic nitrogenous hallucinogens. Also, in contrast to the nutmeg derivatives MDA and MMDA, which do not occur naturally but are the result of in vitro amination, ibogaine and Harmaline, the other two psychedelics which Naranjo found most useful, are very much in evidence in the natural world itself—as are the tryptamines, ergo-lines, isoquinolines, phenylethylamines, and tropanes in the major hallucinogens of the New World, or the isoxazoles of the fly-agaric mushroom, Amanita muscaria.

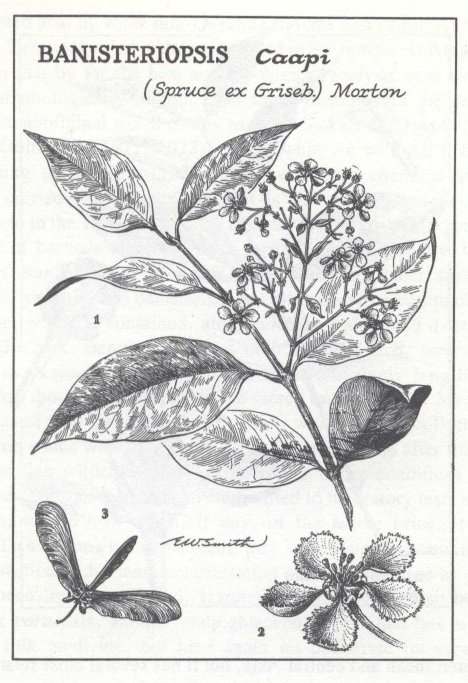

Ibogaine is derived from an equatorial African bush, Tabernanthe iboga, whose hallucinogenic roots are employed in the Bwiti ancestor cult, the MBieri curing cult, and other nativistic religious movements in tropical sub-Saharan West Africa. Harmaline is one of the principal harmala alkaloids in Banisteriopsis caapi, the sacred vine of ecstatic Amazonian shamanism, in related species of the Malphighiaceae, and in Peganum harmala, an Old World plant known also as Syrian rue.

Tabernanthe iboga

Twelve closely related indole alkaloids have been isolated in T. iboga, a member of the Apocynaceae, or dogbanes, a family consisting of tropical herbs, shrubs, and trees characterized by a milky juice, often showy flowers, and simple entire leaves. T. iboga, which occurs wild in the equatorial underforest but is also cultivated widely around villages adhering to the cults, has yellowish or pinkish-white flowers and a small, sweetish-tasting, non-narcotic fruit that is sometimes used as a medicine against barrenness. Although the family as a whole is rich in alkaloids, T. iboga is the only member definitely known to be used as an hallucinogen, with ibogaine apparently the principal psychoactive constituent (Schultes, 1970).

Iboga or eboka has interested the Europeans since the 1800's, when its ritual use was first reported by explorers of Gabon and the Congo. In the last decades of the nineteenth century the German colonial administration of northern Gabon, then German Kamenm, encouraged its use as a central stimulant on tiring marches and colonial labor projects. French medical scientists studied ibogaine—now known to function as a monoamine oxidase inhibitor in the brain—intensively around the turn of the century and adopted it into official medicine as the first antidepressant of its kind, long before the advent of Tofranil, iproniazide, and similar drugs. The first modern psychiatrist to adopt it on a sustained basis as an adjunct to psychotherapy seems to have been Naranjo, who reported his initial results with the drug in 1966. Since then, ibogaine has passed into wider psychiatric use, especially in South America.

Because I want to devote more space in this chapter to the harmala alkaloids, whose subjective effects in psychotherapy sometimes strikingly resemble those reported from the aboriginal cultural context, the discussion of ibogaine will be limited to a summary of its role in African cults (for a wider discussion of its application to psychiatry see Naranjo's The Healing Journey, pp. 174-228).

Iboga Cults in Tropical Africa

The first significant modern anthropological examination of Tabernanthe iboga is that of James W. Fernandez, who studied its role in the Bwiti and MBieri cults of the Fang of Gabon in the larger context of reformist and nativistic African religious movements. What follows is based on a paper published by him in 1972.*

In the Fang tongue T. iboga is called eboka. The principal active alkaloid is mainly concentrated in the root bark, and it is this that the Fang employ for ecstatic inebriation, in the form of raspings, ground up as powder or soaked in water and drunk as an infusion. How much of the drug is consumed depends on the context. The regular way is to ingest small doses of eboka (two to three teaspoonfuls for women and three to five for men) in powdered form before and in the early hours of the ceremonies. The second way is to take truly massive doses once or twice in the career of the cult member for the purpose of initiation and to "break open the head" in order to effect contact with the ancestors. The regular doses amount to about 20 grams in all, containing 75- 125 mg. of ibogaine. This is sufficient to bring about the desired ecstatic dream state in which one travels outside one's body to Otherworlds, where the ancestors dwell and where one learns to do their work (as distinct from the burdensome and psychologically disorienting demands of the rapidly modernizing world outside the tropical rain forest). The massive initiatory dose is very much greater, from forty to sixty times the threshold dose, when the effects make themselves felt. However, in very high amounts eboka is toxic; not surprisingly, as in the toloache (Datura inoxia or meteloides) initiation cults of Southern California Indians, and the red-bean rites of the Southern Plains, overdose deaths from eboka have occasionally been reported.*

How old is the use of T. iboga in equatorial Africa? That is difficult to estimate, but the Fang themselves credit its origin to the Pygmy people of the Congolese rain forest, who were there long before the Fang arrived from the north and who are, in fact regarded by them as their saviors, having shown them how to survive in the unfamiliar and frightening forest environment. Eboka, goes a Fang story recorded by Fernandez (pp. 245-246), was given to the people by the last of the creator gods, Zame ye Mebege:

He saw the misery in which blackman was living. He thought how to help him. One day he looked down and saw a blackman, the Pygmy Bitumu, high in an Atanga tree, gathering its fruit. He made him fall. He died and Zame brought his spirit to him. Zame cut off the little fingers and the little toes of the cadaver of the Pygmy and planted them in various parts of the forest. They grew into the eboka bush.

Eventually the dead man's wife came searching for him. She was told by a disembodied voice to eat of the root of an eboka plant that grew at the left of the mouth of a cave, and of a mushroom (!) that grew on the right. She did so and suddenly the bones of the dead with which the cave was filled came to life, revealing themselves as her husband and other deceased relatives. They told her that she had found the plant that from then on would enable members of the Bwiti cult to see the dead.

Male-Female Symbolism and Acculturation

The mushroom of the origin myth is a white fungus with a large cap that is sometimes consumed in the Bwiti cult and that also plays a role in herbal concoctions. No psychoactive properties have been reported, but the mushroom has not been studied ethnobotanically or chemically.

Fernandez points out several important elements in the myth. First, it clearly identifies the eboka plant with the deep forest and the Pygmies as an agent of transition that enables the people to pass from the familiar village deep into the dark and mysterious forest that holds the secrets of death (recalling that the Fang themselves once made the traumatic transition from the open savannah lands to the north into the equatorial rain forest). Second, there is the universal image of the cave as the place of death and rebirth. Third, the story of the discovery of eboka by the wife emphasizes the crucial role of women in the cult. While in the MBieri curing cult women are dominant, in Bwiti men and women have an equal place. However, the cult directs itself to the female principle of the universe: Nyingwan Mebege, author of procreation and guarantor of a prosperous life. Fernandez also notes that Bwiti eboka is the left-hand plant—the left side of the chapel is female—while the phallic mushroom stands at the right, or male, side, repeating the directional juxtaposition of eboka and mushroom at the entrance to the mythic cave of death and rebirth.

Finally, Fernandez draws attention to a certain eucharistic implication of the planting of parts of the Pygmy who upon his death became eboka:

This makes the consumption of the roots an act of communion with the Pygmy--originator of the cult who had been chosen by Zame and brought to heavenly abode. Hence we have in the eating of eboka a eucharistic experience with similarities to Christian communion. How much of this is a syncretism with Christianity and how much is original with the Fang is difficult to say. One can suspect more of the former. For not only do members of Bwiti practice communion, employing eboka instead of bread, but they also boast of the efficacy of eboka over bread in its power to give visions of the dead. Some of the more Christian branches of Bwiti, not fully cognizant with the origins legend, even speak of eboka as a more perfect and God-given representation of the body of Christ! (p. 247).

This syncretistic view of the meaning of eboka is strikingly similar to what we find today in Mexican mushroom rituals (see Chapter Seven) which likewise blend Christian with traditional Indian elements and identify the mushroom with Christ. But I rather suspect that there is more to the eucharistic implication than just Christian acculturation. In the first place, the origin myth in which a dismembered Pygmy transforms into the sacred hallucinogenic plant is essentially similar to the Colombian Indian tradition of the Yajê Woman and her baby, whose dismembered body becomes Banisteriopsis caapi (see below). This myth is certainly not influenced by Christian beliefs, any more than is the Huichol story of peyote as the transformed flesh of the ritually slain deer deity (see Chapter Ten). Again—the manner in which on the peyote hunt the first peyote—the flesh of the slain deer god—is divided and distributed to his companions by the officiating shaman cannot but recall the Eucharistic "Take, eat, this is my body." Yet there is little question that the Huichol ceremony is pre-European and that its eucharistic element is no more "Christian" than was the communal eating of the dismembered body of the transsubstantiated "god-impersonator" in the sacrificial rite of the Aztecs. Indeed, this act of ritual cannibalism reminded some of the early Spaniards so uncomfortably of the rite of the Eucharist that they tried to explain it away as vile distortion of Christian communion by the Devil himself!

Harmaline and Related Alkaloids

Hallucinogenic harmala alkaloids (harmine, harmaline, harmalol, and harman), which belong to the beta-carbolines, were originally isolated from an Old World perennial Peganum harmala, or Syrian rue. Syrian rue, the traditional source of the characteristic red dye of Turkish carpets, is at home in the Mediterranean and central Asia, but it has several close relatives in the southwestern United States and Mexico, of which none, so far as is known, has ever been employed hallucinogenically. Nor do we know of any deliberate psychedelic use of Peganum harmala, even though the plant is a very old folk remedy of whose intoxicating potential Arab physicians and folk healers of the Orient must surely have been aware since antiquity (Schultes, 1970:576).

Syrian rue is actually only one of at least eight plant familiharmalahe Old and New Worlds in which hannala alkaloids are now known to be present. Botanically the most numerous and culturally the most interesting of these is Banisteriopsis , a malpighiaceous tropical American genus that comprises no less than a hundred different species, of which at least two, B. caapi, discovered and named by Spruce in the mid-nineteenth century, and B. inebrians, and quite possibly others, such as B. muricata, are the basis of the potent hallucinogenic ritual beverages the Indians of Amazonia call, depending on the local language, by such terms as caapi (more correctly, kahpi or yajêi), mihi , dapa, pinde , nathma , yaje , etc. In Quechua, the language of the Incas of pre-Hispanic Peru and of millions of Andean Indians today, the drink is eloquently called ayahuasca, meaning "vine of the souls," a term that has been adopted also by some non-Quechua Indians east of the Andes. Ya.j (or yag) is a Tukanoan word widely employed in the northwest Amazon, and for the reason that by far the best anthropological analysis ever written on the complex mythological, symbolic, and social meanings of the Banisteriopsis drink in the aboriginal world comes from the Tukanoan Desana of Colombia (Reichel-Dolmatoff, 1971, 1972), that is what we will call it here.

According to Schultes (1972a:38), the earliest chemical studies were probably carried on B. caapi, and it is this plant also of which Louis Lewin wrote in the 1920's, when the first psychotherapeutic experiments with an extract of harmala alkaloids were carried out in Germany. Originally a number of Ban isteriopsis alkaloids were described under such names as telepathine, yageine, and banisterine, but all these were eventually identified as harmine, which is contained, along with harmaline and d-tetrahydroharmine, in the bark, stems, and leaves of B. caapi and B. inebrians. These psychedelic alkaloids have been found to be amazingly long-lived—much more so than those, for example, in the sacred mushrooms of Mexico. Pieces of the stems of the type material of B. caapi which Spruce collected in Brazil in 1851, and which were eventually deposited in England after first being lost in the Brazilian wilderness for nearly a year under conditions that hardly favored preservation, were recently submitted to laboratory tests at Schultes's suggestion, to see how much, if any, of the active principles had been retained. To everyone's astonishment, they were found to contain—after 115 years!—practically the same concentration of active harmine as did material that had been freshly collected. Harmala alkaloids have also been isolated from Cabi paraensis, another malpighiaceous genus that has many uses in Brazilian folk medicine, but here again no deliberate intoxicating use is known.

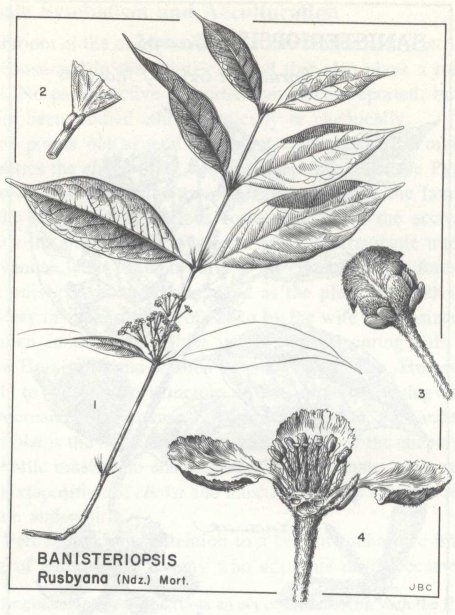

In addition to the two principal species of Banisteriopsis from which ya,1 is known to be made, there is still another that figures in this complex, B. rusbyana, whose stems and leaves, oddly enough, do not contain the betacarboline alkaloids characteristic of B. caapi and B. inebrians but instead yield tryptamines, a pharmacological phenomenon to which we will refer again when we get to the problem of hallucinogenic snuffs. For the moment let it be said only that the way the Indians use B. rusbyana suggests that long before the advent of modern chemistry, they discovered for themselves that the alkaloids of certain plants require the addition of others to become psychedelically effective.

Amazonian Indians as Psychopharmacologists

No one can tell when the Indians of the upper Amazon discovered the "otherworldly" effects of the vine of the souls. But we are probably not far wrong in suggesting that it is at least as old as the characteristic Tropical Forest Culture, which was based on intensive root-crop agriculture and which seems to have been well-established as early as 3000 B.C. or even before (Lathrap, 1970). Tukanoan mythology places the origin of ya.j at the very beginning of the social order, when it is said to have appeared in human form soon after the male Sun had fertilized the female Earth with its phallic ray and the first drops of semen had become the original people. Among them appeared Yaj Woman, who bore a child that was human in shape but also had the quality of light, for it was ya.j and caused the men to have visions. Ya.g Child was dismembered, every man appropriating for himself a part of its body. In turn, each of these became a yaji. vine, which the Tukano equate with lines of descent of their different phratries. As a result of this original act, each phratry has its own particular kind of ya.g (based not on species differentiation but on different external appearances of the plant and the ways its effects are perceived). Descent also forms the basis for the criteria by which different parts of the plant are chosen for the preparation of the hallucinogenic drink (Reichel-Dolmatoff, 1972).

When properly performed according to the sacred traditions, the entire ya.g ritual, from the initial cutting of the vine and the preparation of the drink to the interpretation of the hallucinogenic effects, is highly formalized and circumscribed from beginning to end by a series of ceremonial requirements and taboos. The pottery vessel that will hold the liquid is a ceremonial object symbolizing the maternal womb and the creative process of gestation. The different symbols with which it is decorated represent fertilization and fecundity, including, on its base, a painted vagina and clitoris. Before the vessel can be used it must be ritually purified with tobacco smoke.

Yaje and the Mythic Origins of Society

As described by Reichel-Dolmatoff (1972:97-102), the ya.g-drinking ceremony commences in the communal house after nightfall with ritualized dialogues that recount the Creation Myth and the genealogies of the exogamous phratries, the origins of humanity, of yaji , and of the social order being commemorated with song and dance to the accompaniment of instrumental sounds: a phallic rattle staff that symbolizes the primordial fertilizing ray of the Sun, the rhythmic pounding of wooden tubes, and the rubbing of a turtle shell with wax to imitate the croaking of a frog. Each distribution of yaj is formally introduced by the blowing of a decorated clay trumpet. The ya,j is distributed at prescribed intervals and with ritual gestures and speechmaking by the headman, who fills the cups from the sacred maternal yaj vessel, while the men sit or continue their dancing. As the yaji, effects increase so does the precision with which the dancers coordinate their movements, until at last they seem to be dancing as one body. The hallucinations are called "ya.j images," and the Indians say that the order in which they appear is fixed: some are seen after the third cupful, others after the fourth, and so on. To have bright and pleasant visions one must have abstained from sexual intercourse and have eaten only lightly on the preceding days (exactly as in the peyote rituals of the Huichols of Mexico). At intervals an old man or someone who lays claim to esoteric knowledge describes his visions and interprets them publicly: "This trembling which is felt is the winds of the Milky Way," or "That red color is the Master of the Animals." The women meanwhile keep to themselves at one end of the house. As a rule they do not drink but participate with shouts of encouragement or derisive laughter when someone vomits or refuses a proffered bowl or cup.

What Reichel-Dolmatoff* writes of the subjective reasons why the Indians take yag is of the greatest interest, not just because of what it reveals specifically about the psychocultural mechanisms of the social group involved, the Tukanoan Desana of the Vaupes of Colombia, but also because of its sometimes striking similarity to other such aboriginal "psychedelic" rituals; a comparison with the meaning of peyote among the Huichols, as described later in these pages, will immediately demonstrate this similarity.

In the first place, the Tukano say that one who has had the ya.j experience awakens as a new person, a true Tukano, fully integrated and at one with his traditional culture, for what he has seen and heard in his ecstatic ya.j trance has confirmed and validated the ancient truths of which the shamans and elders have told him since childhood. This is exactly what my Huichol friends told me many times of the meaning of their initiation into the magic of the peyote quest: "We went to find our life; we went to see what it is to be Huichol." Let me quote some salient passages from Reichel-Dolmatoff s account:

According to our informants of the Vaupés, the purpose of taking ya.j is to return to the uterus, to the fons et origo of all things, where the individual "sees" the tribal divinities, the creation of the universe and humanity, the first human couple, the creation of the animals, and the establishment of the social order, with particular reference to the laws of exogamy. During the ritual the individual enters through the "door" of the vagina painted on the base of the vessel.t Once inside the receptacle he becomes one with the mythic world of the Creation. . . . This return to the uterus also constitutes an acceleration of time and corresponds to death. According to the Indians, the individual "dies" but is later reborn in a state of wisdom, because on waking from the yaje trance he is convinced of the truth of his religious system, since he has seen with his own eyes the personifications of the supernaturals and the mythic scenes.. . .

According to the Tukano, after a stage of undefined luminosity of moving forms and colors, the vision begins to clear up and significant details present themselves. The Milky Way appears and the distant fertilizing reflection of the Sun. The first woman surges forth from the waters of the river, and the first pair of ancestors is formed. The supernatural Master of the Animals of the jungle and waters is perceived, as are the gigantic prototypes of the game animals, and the origins of plants—indeed, the origins of life itself. The origins of Evil also manifest themselves, jaguars and serpents, the representatives of illness, and the spirits of the jungle that lie in ambush for the solitary hunter. At the same time their voices are heard, the music of the mythic epoch is perceived, and the ancestors are seen, dancing at the dawn of Creation. The origin of the ornaments used in dances, the feather crowns, necklaces, armlets, and musical instruments, all are seen. The division into phratries is witnessed, and the yurupari flutes promulgate the laws of exogamy. Beyond these visions new "doors" are opening, and through the apertures glimmer yet other dimensions, which are even more profound. . . . For the Indian the hallucinatory experience is essentially a sexual one. To make it sublime, to pass from the erotic, the sensual, to a mystical union with the mythic era, the intra-uterine stage, is the ultimate goal, attained by a mere handful, but coveted by all. We find the most cogent expression of this objective in the words of an Indian educated by missionaries, who said, "To take ya0 is a spiritual coitus; it is the spiritual communion which the priests speak of."

Hallucinogens and Jaguar Transformation

Reichel-Dolmatoff s essay concerns yajg in the social setting; elsewhere he has written of shamanism and jaguar transformation and the role of yaj and other intoxicants in this context. It is in fact a common phenomenon of South American shamanism (reflected also in Mesoamerica) that shamans are closely identified with the jaguar, to the point where the jaguar is almost nowhere regarded as simply an animal, albeit an especially powerful one, but as supernatural, frequently as the avatar of living or deceased shamans, containing their souls and doing good or evil in accordance with the disposition of their human form (Furst, 1968). This qualitative identity of shaman and jaguar is reflected in the fact that in a number of Indian languages the terms for shaman and jaguar are identical or closely related (e.g. yai or dyai = shaman, jaguar, in several Tukanoan languages). Shaman-jaguar transformation is closely linked to the ecstatic trance, by means of tobacco or Anadenanthera or Virola snuff among some peoples, the Banisteriopsis caapi among others, or, as is often the case, tobacco followed by yaje. For some peoples B. caapi is the shaman's vine par excellence, his ladder to the Upperworld, his means of achieving transcendence. "This vine," an Indian informant told the German ethnographer Theodor Koch-Griinberg (1923:388), who traveled widely among the Indians of the Guianas, Venezuela, and northern Brazil in the early decades of this century, "contains the shaman, the jaguar."

Since there are good shamans and bad—i.e. witches or sorcerers—and since both are able to transform themselves into jaguars, it is to be expected that the great jungle cat can appear as a malevolent and frightening demon in unpleasant yali• experiences, not uncommonly in association with giant snakes such as the anaconda. That even a Tukano can have an occasional "bad trip" with yaji is confirmed by Reichel-Dolmatoff (1972). There are instances, he reports (p. 103), when he is nearly overcome by the nightmare of the jaguar's jaws or the menace of snakes that draw near while he, paralyzed with fright, feels their cold bodies winding themselves around his extremities.*

*A recent article by H. Pope in Economic Botany (1969) also contains much valuable ethnobotanical and historic data

*The Fang employ several other plants with hallucinogenic properties, but none plays the pervasive ritual role of eboka One is Alchornea floribunda, called alan. In large amounts alan produces a state that is interpreted as passing over to the land of the ancestors. Some branches of the Bwiti cult mix alan and eboka. The latex of Elaeophorbia drupifera is mixed with oil to form eyedrops that seem to affect the optic nerves, producing bizarre visual effects. Yet another is hemp (Cannabis sp.), which in some branches of Bwiti is smoked after the ingestion of two or three teaspoonfuls of eboka. The smoke symbolizes the travel of the soul to the roof of the Bwiti chapel, where it mingles with the ancestors. Although hemp has long been smoked in Gabon, most branches of Bwiti reject it as a foreign plant that distracts the members from proper ritual matters. Like South American Indians, Fang women also make quids of tobacco and ashes which they hold in their cheeks or under the tongue and which are said to produce a state of pleasant lassitude. (Fernandez, 1972:242-243)

*For other significant recent anthropological literature on Banisteriopsis in its aboriginal context see Michael J. Hamer's The Jivaro : People of the Sacred Waterfalls (1972) and Hallucinogens and Shamanism, M. J. Harner, ed. (1973). For those who read German, KochGriinberg's Vom Roraima zum Orinoco (1917-1928) contains much information on Banisteriopsis and other hallucinogenic plants in the mythology and practice of shamanism in Venezuela, the Guianas, and Brazil, and of course R. E. Schultes's many publications are an essential source not only of botanical and pharmacological but also ethnographic data.

tAmong the sacred places on the ritual itinerary of the Huichol peyote pilgrimage to Wiriküta. the divine, paradisiacal land of the peyote and place of ultimate origins and primordial truths, there is one called "The Vagina."

*My Huichol informants explained "bad trips" as the consequence of imperfect purification prior to a peyote pilgrimage, especially on the sexual plane. An incestuous relationship (the most serious infraction of the ethical code) is almost certain to result in a terrifying rather than pleasant drug experience. However, such negative experiences are not attributed to peyote; rather, say the Huichols, someone who has transgressed and not purified himself before going out to collect peyote will be supernaturally misled into mistaking another hallucinogenic cactus, Ariocarpus retusus, for the true peyote, Lophophora williamsii, and will suffer terrible psychic agonies instead of seeing "what it is to be Huichol" in vividly colored peyote dreams.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|