Chapter 3 The development of European drug policy and the place of harm reduction within this

| Reports - EMCDDA Harm Reduction |

Drug Abuse

Chapter 3 The development of European drug policy and the place of harm reduction within this

Susanne MacGregor and Marcus Whiting

Abstract

This chapter gives a necessarily brief overview of the development of drug policy at the European Union level in recent decades. These developments are set within the wider context of moves towards European integration. The chapter considers how far a process of

convergence has occurred, within which harm reduction may have a central place; and how far this gives a distinctive character to European policy internationally. It draws mainly on documentary evidence and scholarly accounts of policy development. Key processes

identified include: the achievement of agreed policy statements at intergovernmental level; the influence of guidance, action plans and target setting; the role of the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA); the spread of information; networking,

training and collaborative activities among researchers and practitioners; the size and shape of the drug problem; and the impact of HIV/AIDS. While common agreements have been forged at the supra-national level, differences remain between and within different Member

States, reflecting their social and political institutions, differing public attitudes, religious and cultural values, and varying financial and human resources.

Keywords: European drug policy, harm reduction, convergence, cultural and institutional differences, political influences.

Introduction

A steady, progressive evolution of drugs policy, towards a more rational, evidence-based approach, has been the ambition of medical humanists and technocrats involved in policy and practice networks in the EU. Advocates like the International Harm Reduction Association and the Open Society Institute also hope to see harm reduction principles entrenched within policy. In the light of this, the aim of this chapter is to explore how policies have developed over time and what forces have been influential, considering in particular what has been achieved in terms of policy convergence and the introduction of harm reduction. To do this, we draw largely upon an analysis of the content of EU policy documents and key published books and articles.

We define ‘Europe’ here as primarily referring to the European Union, and ‘drug policy’ as statements in EU policy documents. However, we recognise that Europe is a larger geographical and cultural entity than the European Union itself, and that the national policies of European countries also form part of ‘European drug policy’. In addition, we are aware that policies cannot be judged solely on the basis of statements in documents or the rhetoric of politicians and other players on the policy field. ‘Policy’ more broadly defined refers to the way a society meets needs, maintains control and manages risks. To describe and assess this would require analysis of what actually happens and with what impacts. Policy judged by functions or effects may result from forces other than the overt goals in formal policy

statements. In a short chapter such as this, it is not possible to analyse or account for all these forces. We have chosen instead to look mainly at the formal development of EU drug policy, but attempt to set this within its context and to indicate that the process of development has not been inevitable and has at times been contentious.

Methods

This paper draws on research towards a social history of the development of the drugs problem and responses to it over a 30-year period. Here the focus is on European drug policy and specifically its links to public health and discussions of the role of harm reduction

approaches. Methods used have included reviews of secondary literature in books and journals and of documentary evidence, especially that available through European institutions like the European Commission and the EMCDDA. Observation of discussions at

conferences and networking meetings has also played a part, along with interviews with some of the key players in the development of policy over this period. A detailed narrative history is not possible in a short chapter so the approach adopted here is to present an

interpretative account of developments.

The context for policy development

Development of the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a political and economic union in which sovereign countries agree to share or give up some attributions and powers. A simple description of the process of policy development would note that in any given field it starts with open intergovernmental discussions then moves into areas where the union’s institutions obtain some power of proposition, action or decision. The EU is thus a policy actor in itself and one that is progressively trying to create convergence, while limited in its influence on actions at national level.

The EU has expanded rapidly to its current 27 Member States in a period of economic liberalisation involving free movement of both labour and capital and a reduction in border controls. The size and shape of the drugs problem and responses to it within Europe have been

influenced by these larger trends and the series of treaties that marked this trajectory: the Single European Act 1986; Maastricht Treaty 1993; Amsterdam Treaty 1997; and the most recent Lisbon Treaty. These Acts were important contextual features and, together with the collapse of the Soviet Union and reductions in border controls, influenced the supply of illicit drugs and the responses of criminal justice agencies. A number of key principles are important features of the European Project, especially human rights, electoral democracy and free trade.

Throughout this period there have been two different visions of the European Union — characterised as the ‘widening’ or ‘deepening’ scenarios — with enlargement paralleling the dominance of the widening, free market approach. This approach emphasises economic cooperation alongside the retention of national sovereignty and national differences with regard to social and political institutions. The deepening agenda would hope to see agreement on social policies.

While drug policy does not fit neatly into conventional models of social policy, attitudes to drugs and social responses to problems do reflect the historical development of institutions (constraining and shaping options for policy change) and cultural norms relating to rights and responsibilities. Moves towards a shared EU approach to drugs have been in this sense part of the European Project. The development of a drug policy could indicate some success for moves to deepen integration, with the development of shared practices related to social and criminal justice policies. The widening agenda — with enlargement increasing the number of EU Member States — clearly presents problems for integrationist ambitions as it increases the range of difference to be potentially coordinated in any shared strategy — differences of culture, language, path dependency in the development of institutions, human and financial resources: these and more influence the potential for acceptance and implementation of policy proposals.

National policies

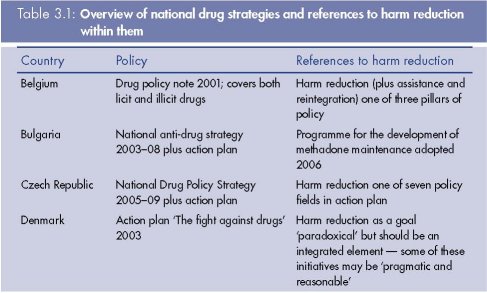

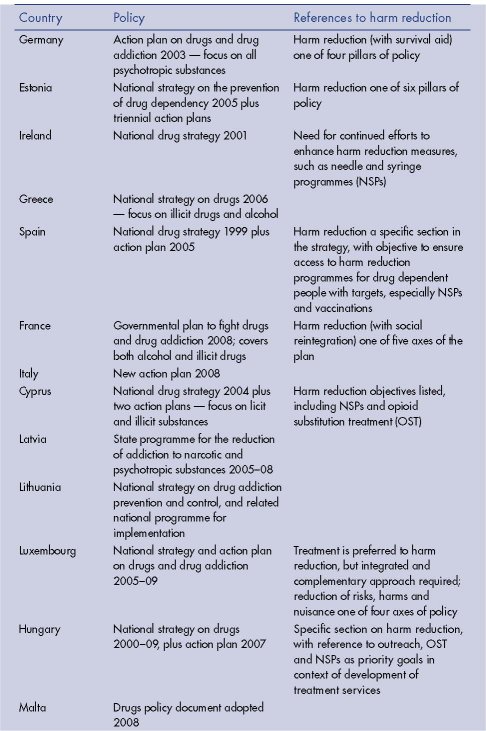

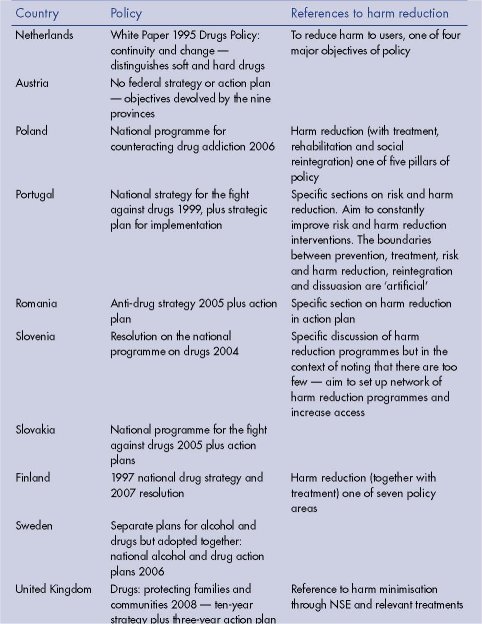

We begin with a brief overview of the current state of play, considering what has been achieved in terms of policy coordination and recognition of a role for harm reduction. In 2008, there were 14 national strategies, 15 action plans, six programmes, two policy notes/documents, one white paper, one governmental plan, one implementation decree, and numerous provincial, regional, local or devolved administration documents relating to drug policy within the countries of the EU. A general trend can be discerned towards the

production of explicit strategies and related action plans, increasingly linked to an overall EU drugs strategy. Within these statements, the term ‘harm reduction’ is often present and in some countries is specifically identified as a major policy goal (see Table 3.1).

At the present time, EMCDDA states, ‘the prevention and reduction of drug-related harm is a public health objective in all Member States and in the EU drug strategy and action plan ... The general European trend is one of growth and consolidation of harm reduction measures’ (EMCDDA, 2009, p. 31). But a closer look at the current situation gives a more qualified picture. EU Member States do employ a combination of some of the main harm reduction measures, which ‘are reported to be available in all countries except Turkey [but]

considerable differences exist in the range and levels of service provision’ (EMCDDA, 2009, p. 31).

Thus, harm reduction occupies a clear place within European policies but its influence should not be overstated. However, while differences between countries remain, these are not as great as in earlier times. The move to a shared position has involved compromises and a shift to the centre. Shared features of policy are also evident in the stress on research and information exchange and use of managerialist approaches, involving action plans, logframes, strategies, targets and benchmarks.

How, then, do we explain continuing differences at national level? Do drug policies follow the shape of the drug problem in a country, and is this in itself a reflection of attitudes to drug use? Or can the policy environment influence attitudes and thus the size and nature of drug taking and associated problems?

Since 1998, the year of the UNGASS Twentieth Session Declarations (United Nations, 1998),‘most European countries have moved towards an approach that distinguishes between the drug trafficker, who is viewed as a criminal, and the drug user, who is seen more as a sick person in need of treatment’ (EMCDDA, 2008, p. 22). Differences remain, however, for example on whether or not to set threshold quantities for personal possession. There are differences also regarding maximum or probable sentences and whether or not these are

becoming more punitive or lenient. Encouragement into treatment (increasingly as an alternative to a criminal charge or sentence) is developing across countries, but differences remain with regard to the stage when referral to treatment occurs. In the majority of Member

States, substitution treatment combined with psychosocial care is the predominant option for opioid users. Shared concerns about public nuisance are visible, as are concerns around driving under the influence or use in the workplace.

In general, public attitudes to drug taking appear to remain primarily restrictive. For example, a Eurobarometer survey in 2006 conducted in 29 countries found only 26 % supporting legalisation of the possession of cannabis for personal use (ranging from 8 % in Finland to 49 % in the Netherlands) (Eurobarometer, 2006, pp. 36, 49–50). A review of attitudes to drug policy in three countries with relatively restrictive policies (Bulgaria, Poland and Sweden) and three countries with relatively liberal ones (Czech Republic, the Netherlands and Denmark) found that for most people the most important factor influencing them not to use illicit drugs was concern about health consequences (ranging from 73 % in Bulgaria to 27 % in Holland). Fewer were primarily influenced by the fact of illegality (ranging from 3 % in Denmark to 19 % in Poland). Most saw prevention and education as the most important policy area (ranging from 17 % in Poland to 57 % in Sweden). Needle and syringe programmes (NSPs) were supported by some respondents (ranging between 22 % in Sweden and 54 % in Denmark) but opposed by others (ranging from 7 % in Denmark to 29 % in Bulgaria).

This survey found a correlation between public attitudes on drug use and a country’s drug policies (Hungarian Civil Liberties Union, 2009). Countries were deeply divided in their views on the decriminalisation of cannabis. The majority considered drug use to be a public health issue and there was wide acceptance of NSPs as a response to HIV. However, the majority believed that prescribing heroin for addicts would do more harm than good. It is worth noting that some of the countries described above as relatively liberal have seen legislative and administrative moves to more repressive responses in recent years. So there is movement in a number of directions, away from harm reduction and public health principles in some cases, while in others there is a move towards agreement around a core of the more moderate and less contentious issues.

European Union drug policy

EU Member States are the main actors in the drug field, and drug legislation is a matter of national competence. However, the Treaties explicitly acknowledge the need to deal with drug issues at EU level, in particular in the fields of justice and home affairs, and public

health. The tension between ideas of law enforcement and ideas of public health is built into this policy area. Drug trafficking has been a key area for developing cooperation between police and judiciaries. A multidisciplinary group has been working on organised crime and

increased cooperation has developed between police, customs and Europol groups. The main technical and policy forum to facilitate joint efforts of Member States and the Commission is the EU Council’s Horizontal Drugs Group (HDG). This meets about once a month, bringing together representatives of Member States and the Commission. The HDG is playing a key role in the drafting of European drug policy documents. One of them is the current EU drugs strategy (2005–12) endorsed by the Council of the European Union in

December 2004, which sets out two general aims:

1. The EU aims at a contribution to the attainment of a high level of health protection, well being and social cohesion by complementing Member States’ action in preventing and reducing drug use, dependence and drug related harms to health and society; and

2. the EU and its Member States aim to ensure a high level of security for the general public by taking action against drug production, cross border trafficking in drugs and diversion of precursors and by intensifying preventive action against drug related crime through

effective cooperation embedded in a joint approach.

(European Commission, 2008, p. 7)

Overall, responsibility for drugs continues to be diffused across all pillars (1), leading to some confusion, and a constant struggle to improve coordination, which has developed in some areas more than others. The strategy also stresses the value of consultation with a broad group of partners, principally scientific centres, drug professionals, representative nongovernment organisations (NGOs), civil society and local communities. The current EU drugs action plan focuses on five priorities: improving coordination, cooperation and raising public awareness; reducing the demand for drugs; reducing the supply of drugs; improving international cooperation; and improving understanding of the problem.

Moves toward harm reduction

Under the heading of demand reduction, objective 10 of the current 2009–12 EU drugs action plan refers specifically to harm reduction. The objective here is to ‘ensure access to harm reduction services in order to reduce the spread of HIV/AIDS, hepatitis C and other

drug-related blood borne infectious diseases and to reduce the number of drug-related deaths in the EU’ (OJ C 326, 20.12.2008, p. 14).

Before that, on 18 June 2003, the Council of the EU had already adopted a recommendation on the prevention and reduction of health-related harm associated with drug dependence.

This referred to the following aims:

Member States should, in order to provide for a high level of health protection, set as a public health objective the prevention of drug dependence and the reduction of related risks, and develop and implement comprehensive strategies accordingly … Member States should, in order to reduce substantially the incidence of drug-related health damage (such as HIV, hepatitis B and C and tuberculosis) and the number of drug related deaths, make available, as an integral part of their overall drug prevention and treatment policies, a range of different services and facilities, particularly aiming at risk reduction.

(Council of the European Union, 2003/488/EC)

This recommendation called upon Member States to provide a number of harm reduction interventions, including: information and counselling; outreach; drug-free and substitution treatment; hepatitis B vaccination; prevention interventions for HIV, hepatitis B and C, tuberculosis and sexually transmitted diseases; the distribution of condoms; and the distribution and exchange of injecting equipment (see also Cook et al., 2010).

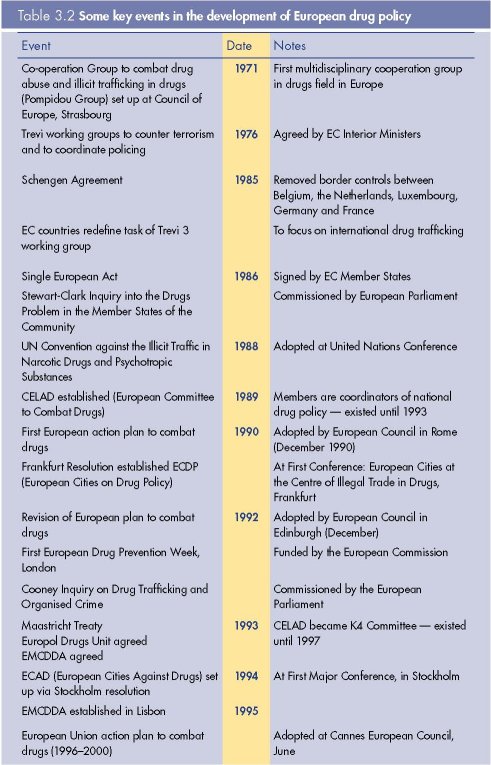

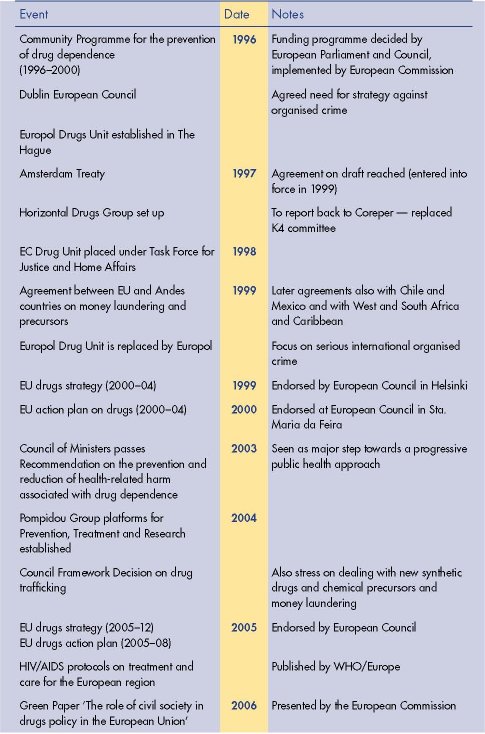

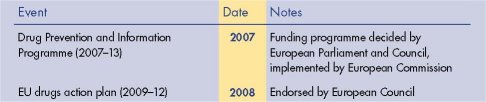

Drawing upon numerous EU policy documents, Figure 3.1 summarises some key events in the development of EU drug policy, noting the place of harm reduction within this. It suggests that until the mid-1980s, the idea of a European drug policy had not even been debated. Since this time, attention to drug issues has increased, and policy has developed in scope and detail. In the 1992 Maastricht Treaty, drug dependence was included in the field of public health. This was the first example of an EU treaty that specifically mentioned drugs and opened the possibility for setting up EU action and funding programmes in this field, although under the principle of ‘subsidiarity’. Subsidiarity means that in policy areas that do not come within the exclusive competence of the Community, action would be taken at EU level only if the objectives of the proposed action could not be sufficiently achieved by Member States acting alone and could be better achieved by the Community.

The 1997 Treaty of Amsterdam put even more stress on public health and made explicit reference to drugs. It was agreed that ‘the Community shall complement the Member States’ actions in reducing drugs-related health damage, including information and prevention’.

Specific interventions are now detailed in two action plans (2005–08 and 2009–12) which inter alia aim to significantly reduce the prevalence of drug use among the population and the social harm and health damage caused by the use of and trade in illicit drugs. Actions at

EU level must be targeted and offer clear added value, and results must be realistic and measurable. Actions must also be cost-effective and contribute directly to the achievement of at least one of the goals or priorities set out in the EU drug strategy. Evaluation of the impact of the first action plan (2005–08) in the area of demand reduction concluded that: ‘There remains a lack of reliable and consistent information to describe the existence of or evaluate the impact of prevention programmes; that further improvements are still needed in

accessibility, availability and coverage of treatment programmes; and that the majority of Member States offer drug-free treatment, psychosocial treatment and substitution treatment’

(European Commission, 2008, p. 66).

The European Commission concluded that:

In the field of harm reduction, major progress has been achieved in recent years. In all EU Member States the prevention and reduction of drug related harm is a defined public health objective at national level. Among the most prevalent interventions are needle and syringe

exchange programmes, outreach workers and opioid substitution treatment combined with psychosocial assistance. However availability and accessibility of these programmes are variable among the Member States and in some countries with low coverage, there are signs of higher levels of risk taking among new, younger generations of — in particular — heroin injectors who have not been reached by prevention and harm reduction messages.

(European Commission, 2008, p. 66 [6.1.2.3: 4])

The continuing lack of provision of services in relation to drug users in prison and released prisoners was also noted, while ‘treatment and harm reduction programmes are often not tailored to address the specific needs and problems of different groups of problem or

dependent drug users, for example, women, under-aged young people, migrants, specific ethnic groups and vulnerable groups’ (European Commission, 2008, p. 66 [6.1.2.3:7]). The Commission also noted that ‘the evaluation shows that the action plan supports a process of convergence between Member States’ drug policies and helps to achieve policy consistency between countries’ (European Commission, 2008, p. 67 [6.1.3:2]).

Factors influencing the development of EU drugs policy

On the occasion of the launch of the EMCDDA’s Annual report on the state of the drug problem in Europe in 2008, the Director, Mr Götz, said, ‘there is a stronger agreement on the direction to follow and a clearer understanding of the challenges ahead’, indicating his

opinion that within Europe a convergence of views on policy is developing. If this is so, it is a remarkable change in just over 20 years.

A number of factors appear to have been influential in shaping developments in European drug policy:

• the evolution within the European Union of competencies in the field of drugs;

• the rising political priority of drugs across the areas of public health, public security (justice and home affairs) and external relations;

• a clear demand from various European institutions as well as Member States for information and evidence for policymaking and decisions;

• the creation of institutions such as the Pompidou Group and then EMCDDA and its national counterparts to meet those information needs;

• the existence alongside the institutional developments of longstanding and interlinked human networks of drug researchers and the possibilities to channel that scientific knowledge into the institutional process;

• the wider influence of international connections and the exchange of knowledge and experience.

(Hartnoll, 2003, p. 67)

Additional factors are: the growing similarities between countries in the nature and extent of their drug problems; the influence of evidence-based reason winning over ideology; and the effects of involvement in the practice of data collection and analysis, and a related

development of norms, values and institutions (Bergeron and Griffiths, 2006, p. 123). In general terms, trends in drug use have affected many EU countries in roughly the same way and at roughly the same time (Bergeron and Griffiths, 2006). These have led to fairly radical

changes in many countries, especially in the light of HIV/AIDS (see also Cook et al., 2010). In most EU countries, HIV and AIDS became a problem in the 1980s, levelling off after the 1990s, but with high levels of hepatitis C (EMCDDA, 2008). In addition, ‘since the 1985

Schengen agreement, and its facilitation of free movement around Europe, the prevention of international drug trafficking and organised crime has become a priority for all member states’ (Chatwin, 2007, p. 496) and

national governments are eager to reap the benefits of unity in the area of controlling organised crime and the illegal trafficking of drugs. However, spillover of this level of European control to areas other than drug trafficking and organised crime prevention has not been as extensive. Trends towards the implementation of harm reduction initiatives and the decriminalisation of the drug user can be observed across Europe, with notable exceptions, but unity of policy in this area does not enjoy the same degree of official encouragement

(Chatwin, 2007, p. 497)

However, Chatwin has concluded that with regard to ‘the fight against organised crime and drug trafficking, some progress towards a European drug policy is being made’ (Chatwin, 2003, pp. 40–1). Finally, the ‘context of a particular country, its size, geographical position

and relation to its neighbours, the state of the drug problem and public opinion … political context [and] political ideology’ all influence national strategies (Muscat, 2008, p. 9).

Harm reduction in international policy debates

In 1992, the Cooney Report to the European Parliament had advocated the use of needle exchange and methadone treatment programmes (Cooney, 1992). This was evidence of a growing pragmatic approach in Europe based on harm reduction principles, reflecting a

significant shift of opinion between 1985 and the early 1990s, very much influenced by awareness of HIV/AIDS and its links to injecting drug use (Stimson, 1995). The European Parliament at the time did not, however, adopt these recommendations.

As illustrated in Table 3.2, there were a number of developments over the 1990s (see also Estievenart, 1995; Kaplan and Leuw, 1996), and in 2004 a former Interpol Chief writing in Le Monde felt able to declare the ‘war on drugs’ lost. Raymond Kendall said that it was time for an alternative approach — ‘harm reduction’ — and called for Europe to take the lead in an international movement to reform policy when the UN drug conventions came up for renewal in 2008. He said:

Policies based solely on criminal sanctions have failed to demonstrate effectiveness. Economic corruption increases, organised crime prospers and developing economies are hard hit by military and environmental (crop eradication) interventions that have no apparent positive effect. At the same time, the marginalisation of drug users is compounded. There is therefore an urgent need for a multi-dimensional and integrated approach, which aims at reducing both supply and demand, and which also integrates harm reduction strategies designed to protect the health of the individual drug user as well as the well-being of society as a whole

(Le Monde, 26 October 2004)

Is Europe now leading the policy case for harm reduction? Judged in terms of where things were a few decades ago, Europe does appear to have a recognisably shared approach and countries have coordinated their policies. Importantly, Europe tends increasingly to speak with one voice on the international stage.

EU drugs policy respects the International Drugs Conventions and implements the five principles of international drug policy adopted at the UN General Assembly Special Session (UNGASS) on Drugs of June 1998 (United Nations, 1998). These principles are: shared

responsibility — de-emphasising the distinction between producing and consuming countries; an emphasis on multilateralism — recognising that unilateral action to single out particular countries is ineffective; a balanced approach — controlling demand as well as controlling supply; development mainstreaming — the drugs problem is complex and attention to sustainable development is critical; and respect for human rights.

The EU is also playing an active role in developing UN drug policy, notably promoting the emphasis on demand reduction. For example, the Action Plan on Demand Reduction that followed the 1998 UNGASS resolution rested on a set of guiding principles on demand

reduction, based to an extent on ideas of harm reduction, though the term itself was not allowed — ‘adverse consequences of drug use’ was preferred. In this way, European ideas can be seen to be penetrating to the international level. More recently the EU also supported

the UNGASS reviews, for example by preparing resolutions for the Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND) meetings. A thematic paper drafted by the EMCDDA on the role of syringe provision in the reduction of infectious disease incidence and prevalence was presented to

the HDG before the 2005 CND session and formed the basis of a mutually agreed position from EU Member States (EMCDDA, 2004).

The EU’s influence is partly levered by financial contributions: for example, between 1971 and 1998 the total contribution to UN drugs-related activities through UNODC from EU countries amounted to $535 million. Currently, EU countries contribute at least half of the UNODC budget. Additionally, in international cooperation activities with countries that want to sign association agreements with the EU, like Iran and Afghanistan, drug-related issues are raised, with human rights being discussed routinely. Particular attention is also given to assisting third countries, especially those applying for future membership of the EU, and countries that are main transit points for drugs reaching the EU. The EU thus reaches out to Latin America and the Caribbean, to central and south-east Asia and to West and South Africa.

According to one drug policy researcher:

The European Union is now mainly a single voice at international meetings with a strong and explicit harm reduction tone even though there are signs of modest retreat from some of the boundaries of harm reduction

(Reuter, 2009, p. 512)

In its evaluation of the EU drugs action plan 2005–08, the European Commission also concluded that the EU is increasingly speaking with one voice in international fora, notably in the UN CND (European Commission, 2008). It noted that the EU maintained a unified

position in the UNGASS review process and that during the CND Working Sessions in 2006–08, the successive EU Presidencies delivered joint EU statements on the follow-up to UNGASS, drug demand reduction, illicit drug trafficking and supply, the International

Narcotics Control Board (INCB) and policy directives to strengthen the UNODC Drug Programme, and the role of the CND as its governing body. The Commission, on behalf of the European Community, delivered its traditional statement on precursors at each CND

session. However, the Commission warned that a harmonised approach among EU actors during the plenary meetings had to be maintained to ensure the EU speaks with one voice (European Commission, 2008). The EU positioned a paper in 2009 to CND noting the

importance of harm reduction, but the inclusion of the words ‘harm reduction’ in the final UN statement were resisted, as they were a decade earlier in 1998 (International Drug Policy Consortium, 2009). Yet, while Europe may be seen to speak with one voice at the highest

elite level, it is important to note that differences remain between and within countries, and groups organise to put pressure on these elites (see box on p. 73).

(box 73:) Voices against harm reduction

Drug abuse is a global problem ... Even though the world is against drug abuse, some organizations and local governments actively advocate the legalisation of drugs and promote policies such as ‘harm reduction’ that accept drug use and do not help drug users to become free from drug abuse. This undermines the international efforts to limit the supply of and demand for drugs. ‘Harm reduction’ is too often another word for drug legalisation or other inappropriate relaxation efforts, a policy approach that violates the UN Conventions. There can be no other goal than a drug-free world. Such a goal is neither utopian nor impossible.

(Declaration of World Forum Against Drugs, Stockholm, Sweden, 2008)

Step-by-step development

It appears therefore that in drug policy as in other policy areas, incremental change has been the explicit strategy of those aiming at ‘closer European Union’ (that is, achieving an increasing proportion of common positions in policy statements), and has been actively

pursued by the key actors within the dominant institutions of the EU (Hantrais, 1998; Clarke, 2001, p. 34).

While enlargement might have been expected to lead to greater diversity within Europe on drug issues, oddly, convergence or harmonisation have in many ways followed the expansion of the EU. EU accession instruments had an impact on drug policy convergence

and the adoption of harm reduction in new Member States. This is partly because the accession countries were keen to drop all vestiges of the former Soviet system and were open to demonstrating their adherence to European values and policies. The deliberate policy of

institution building within the EU encouraged this process, including the coordination of activities aimed at synchronisation in the conduct of reviews, publishing of strategies and action plans and attention to the value of information and evaluation. Drugs as an issue can

serve these purposes very well since drug misuse is at face value something all agree to be a bad thing: through the process of deliberating on drug policy, networks develop, institutions are formed and the wider aspects of a European approach are learnt, such as transparency, justification by reference to evidence, dialogue, and involvement of civil society.

For instance, the European Union PHARE (2) programmes exercised influence over candidate countries aiming to meet the requirements for accession. The European Commission funded a multi-beneficiary drug programme within PHARE, and the EU included national drug policy as an area of focus in its accession talks with candidate countries, which all signed the UN Conventions. Many candidate countries made the prevention of trafficking of illicit drugs an area of special attention and focus.

There have thus been a number of steps in the path towards convergence: the shared experience of practitioners, especially those involved in tackling the heroin, HIV/AIDS and hepatitis C epidemics and treating injecting drug users (IDUs); an increasingly shared perception of the problem, partly encouraged by dialogue around the development of information resources; the development of a common language to support the discourse; and the adoption of a set of common methods and reporting standards.

Forums and networks have also played a role in developing shared understandings and approaches to the European drug problem. With the Frankfurt Resolution of November 1990, representatives from the cities of Amsterdam, Frankfurt, Hamburg and Zurich resolved

that attempts at eliminating drugs and drug consumption were a failure and that a new model was needed to cope with drug use in European cities (http://www.realitaeten-bureau.de/en_news_04.htm). This led to the setting up of European Cities on Drug Policy (ECDP),

which helped open up the debate for a Europe-wide harm reduction drug policy approach. The direct involvement of user groups as well as epidemiologists and medical and criminal justice and other practitioners has been another important factor. ENCOD (European

Coalition for Just and Effective Drug Policies) is a European network of about 156 organisations and individual citizens affected by and concerned about current drug policies. Another important network is the International Drug Policy Consortium — ‘promoting objective and open debate of drug policies’; this brings together NGOs and professionals who specialise in issues related to illegal drugs, while the International Harm Reduction Association (IHRA) has influence through its efforts to promote a harm reduction approach to all psychoactive substances on a global basis.

On the other hand, there have continued below the surface to be strong opposing currents of opinion on drug policy (see box on p. 73). In April 1994, the Stockholm resolution aimed to promote a drug-free Europe and established European Cities Against Drugs (now with 264 signatory municipalities in 30 countries). In this process, Sweden played a leading role (http://www.ecad.net/resolution).

Conclusion

Some have noted ‘a clear trend across Europe towards the recognition of harm reduction as an important component of mainstream public health and social policies towards problem drug use’, representing something of a ‘sea change in European drug policies’ (Hedrich et al., 2008, p. 512). This convergence appears to have been strongly influenced by the production of EU drugs strategies from 1999 onwards, and the development of concrete, measurable targets, action plans and evaluation strategies. Hedrich et al. note:

By including harm reduction as a key objective of drug policy, EU action plans not only reflect what was already happening in some Member States in response to serious public health challenges but [also] that European instruments further consolidated harm reduction as one of the central pillars of drug policy.

(Hedrich et al., 2008, p. 514)

Convergence towards ‘policy consensus’ was thus ‘mediated by EU guidance while not originating from it’ (Hedrich et al., 2008, p. 507).

The evidence reviewed in this chapter supports a conclusion of a progressive although limited convergence in European drug policies and that harm reduction is both an element and an indicator of this convergence. Opioid substitution treatment and needle and syringe

programmes have become part of the common response in Europe for reducing problems related to drug injecting. This is characterised as a ‘new public health’ response to injecting drugs and HIV/AIDS (see also Rhodes and Hedrich, 2010).

EU drugs policy mixes traditional law enforcement approaches with an increasing focus on public health. A public health approach could be seen as relatively humane, sympathetic to those affected by drug use — both users, and families and communities — and as following ethical principles (see also Fry, 2010). The public health model still, however, rests on a ‘disease’ conception of drug use, framing it as an infectious and communicable disease that can be regulated from above, using a package of measures including surveillance and monitoring and aiming at containment. The starting point is recognising that the disease is present, even if measures should try to prevent or eliminate it. The main concern is to reduce the risk of transmission and its development into an epidemic. This

conception has grown in power with the arrival of HIV/AIDS, exacerbated more recently by hepatitis C. It is a feature of this model also to assume that some members of populations are more vulnerable than others and that, although the underlying causes may need to be understood and tackled, in the short term the focus should be on targeting these groups. The priority is to focus on containing and managing the disease. This approach, based on scientific evidence and filtered through a range of regulatory and advisory bodies, produces directives, recommendations and guidance documents to which national governments are expected to respond. These increasingly influence national policies, partly because national governments want to ‘show willing’, be part of and signed up to the European Project, and also in some cases because governments do not actually consider drugs to be as important an issue as others on their busy agendas, so they do not bother to contest the matter.

In reality, implementation, a crucial element in the policy process, is influenced by the degree of acceptance by those involved of the measures suggested. Treatment professionals, service providers and budget holders influence the shape of service responses, and the wider society — of non-governmental pressure groups, drug users themselves and families and communities — may agree or disagree about the basic values on which these recommendations are based.

Overall, however, within Europe, a coordinated and increasingly coherent ‘middle ground’ policy on drugs appears to be emerging, within which harm reduction has an accepted place. But there is continuing tension between opposing views. A compromise may hold for a

while, but with changing circumstances and conditions further policy adaptations are likely to appear on the agenda.

Acknowledgements

The research on which this chapter is based was supported by an Emeritus Fellowship awarded to Susanne MacGregor by The Leverhulme Trust, for which we are very grateful. We would like to thank reviewers of drafts of this chapter for their valuable comments, which

we have endeavoured to take into account. Any errors or faults of interpretation remain our responsibility.

(1) Between 1993 and 2009, the European Union (EU) legally comprised three pillars: economic, social and environmental policies; foreign policy and military matters; and one concerning cooperation in the fight against crime. This structure was introduced with the Treaty of Maastricht in 1993, and was eventually abandoned on 1 December 2009 with the entry into force of the Treaty of Lisbon, when the EU obtained a consolidated legal personality.

(2) Acronym deriving from the original title of the EU assistance programme, Pologne Hongrie Assistance pour la Réstructuration Economique.

References

Bergeron, H. and Griffiths, P. (2006), ‘Drifting towards a more common approach to a more common problem: epidemiology and the evolution of a European drug policy’, in Hughes, R., Lart, R. and Higate, P. (eds), Drugs: policy and politics, Open University Press, Milton Keynes, pp. 113–24.

Chatwin, C. (2003), On the possibility of policy harmonisation for some illicit drugs in selected member states of the European Union, Sheffield University, PhD thesis.

Chatwin, C. (2007), ‘Multi-level governance: the way forward for European illicit drug policy?’, International Journal of Drug Policy 18, pp. 494–502.

Clarke, J. (2001), ‘Globalisation and welfare states: some unsettling thoughts’, in Sykes, R., Palier, B. and Prior, P. M. (eds), Globalisation and European welfare states, Palgrave, Houndsmill, pp. 19–37.

Cook, C., Bridge, J. and Stimson, G. V. (2010), ‘The diffusion of harm reduction in Europe and beyond’, in European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA), Harm reduction: evidence, impacts and challenges, Rhodes, T. and Hedrich, D. (eds), Scientific Monograph Series No. 10, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

Cooney, P. (1992), Report of the Committee of Inquiry on the spread of organised crime linked to drug trafficking in the Member States of the Community, 23 April, European Parliament, meeting documents, A3-0358/91.

EMCDDA (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction) (2004), A European perspective on responding to blood borne infections among injecting drug users: a short briefing paper, European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, Lisbon. Available at http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/html.cfm/index5777EN.html.

EMCDDA (2008), The state of the drugs problem in Europe, European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, Lisbon.

EMCDDA (2009), The state of the drugs problem in Europe, European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, Lisbon.

Estievenart, G. (ed.) (1995), Policies and strategies to combat drugs in Europe, European University Institute, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, Florence.

Eurobarometer (2006), ‘TNS Opinion and Social’, Public opinion in the European Union, Standard Eurobarometer, 66, Autumn, European Commission. Available from http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/eb/eb66/eb66_en.htm.

European Commission (2008), Commission staff working document. Accompanying the communication from the Commission to the Council and the European Parliament on an EU drugs action plan (2009–2012) — report of the final evaluation of the EU drugs action plan (2005–2008), {COM(2008) 567} {SEC(2008) 2455} {SEC(2008) 2454}, European Community, Brussels. Available at http://eur-lex.europa.eu/SECMonth.do?year=2008&month=09.

Fry, C. (2010), ‘Harm reduction: an “ethical” perspective’, in Chapter 4, ‘Perspectives on harm reduction: what experts have to say’, in European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA), Harm reduction: evidence, impacts and challenges, Rhodes, T. and

Hedrich, D. (eds), Scientific Monograph Series No. 10, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

Hantrais, L. (1998), ‘European and supranational dimensions’, in Alcock, P., Erskine, A. and May, M. (eds), The student’s companion to social policy, Blackwell, Oxford, pp. 199–204.

Hartnoll, R. L. (2003), ‘Drug epidemiology in the European institutions: historical background and key indicators’, Bulletin on Narcotics LV (1 and 2), pp. 53–71.

Hedrich, D., Pirona, A. and Wiessing, L. (2008), ‘From margin to mainstream: the evolution of harm reduction responses to problem drug use in Europe’, Drugs: education, prevention and policy 15, pp. 503–17.

Hungarian Civil Liberties Union (2009), Public poll survey on drug policy attitudes in 6 EU Member States, HCLU. Available at http://eudrugpolicy.org/files/eudrugpolicy/PollReportEDPI.pdf.

International Drug Policy Consortium (2009), The 2009 Commission on Narcotic Drugs and its high level segment: report of proceedings, IDPC Briefing Paper, April 2009.

Kaplan, C. D. and Leuw, E. (1996), ‘A tale of two cities: drug policy instruments and city networks in the European Union’, European Journal of Criminal Policy and Research 4, pp. 74–89.

Kendall, R. (2004), ‘Drugs: war lost, new battles’ [Drogues: guerre perdue, nouveaux combats], Le Monde 26 October — opinion editorial.

Muscat, R. and members of the Pompidou research platform (2008), From a policy on illegal drugs to a policy on psychoactive substances, Council of Europe Publishing, Strasbourg.

Official Journal of the European Union (2008) Official Journal of the European Union C 326, 20.12.2008, Part IV: Notices from European Union Institutions and Bodies: Council, EU Drugs Action Plan for 2009–2012. Available at: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/JOIndex.do?year=2008&serie=C&textfield2=326&Submit=Search&_ submit=Search&ihmlang=en.

Reuter, P. (2009), ‘Ten years after the United Nations General Assembly Special Session (UNGASS): assessing drug problems, policies and reform proposals’, Addiction 104, pp. 510–17.

Rhodes, T. and Hedrich, D. (2010), ‘Harm reduction and the mainstream’, in European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA), Harm reduction: evidence, impacts and challenges, Rhodes, T. and Hedrich, D. (eds), Scientific Monograph Series No. 10, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

Stimson, G. V. (1995), ‘AIDS and injecting drug use in the United Kingdom, 1987–1993: the policy response and the prevention of the epidemic’, Social Science and Medicine 41, pp. 699–716.

United Nations (1998), ‘UN General Assembly Twentieth Special Session World Drug Problem 8–10 June’. United Nations, New York. Available at http://www.un.org/documents.

United Nations (2008), ‘Economic, Social and Economic Council, Commission on Narcotic Drugs, fifty-first session’, The world drug problem: fifth report of the Executive Director, United Nations, Vienna, 10–14 March (E/

CN.7/2008). Available at http://www.unodc.org.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|