Chapter 2 The diffusion of harm reduction in Europe and beyond

| Reports - EMCDDA Harm Reduction |

Drug Abuse

Chapter 2 The diffusion of harm reduction in Europe and beyond

Catherine Cook, Jamie Bridge and Gerry V. Stimson

Abstract

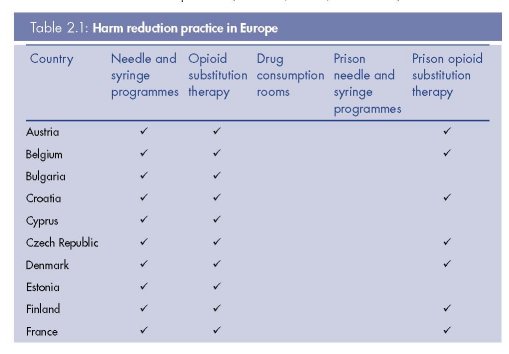

This chapter traces the diffusion of harm reduction in Europe and around the world. The term ‘harm reduction’ became prominent in the mid-1980s as a response to newly discovered HIV epidemics amongst people who inject drugs in some cities. At this time, many European cities played a key role in the development of innovative interventions such as needle and syringe programmes. The harm reduction approach increased in global coverage and acceptance throughout the 1990s and became an integral part of drug policy guidance from the European Union at the turn of the century. By 2009, some 31 European countries supported harm reduction in policy or practice — all of which provided needle and syringe programmes and opioid substitution therapy. Six countries also provided prison needle and syringe programmes, 23 provided opioid substitution therapy in prisons, and all but two of the drug consumption rooms in the world were in Europe. However, models and coverage vary across the European region. Harm reduction is now an official policy of the United Nations, and Europe has played a key role in this development and continues to be a strong voice for harm reduction at the international level.

Keywords: history, harm reduction, global diffusion, international policy, Europe.

Introduction

The term ‘harm reduction’ refers to ‘policies, programmes and practices that aim to reduce the adverse health, social and economic consequences of the use of legal and illegal psychoactive drugs’, and are ‘based on a strong commitment to public health and human

rights’ (IHRA, 2009a, p. 1). The term came to prominence after the emergence of HIV in Europe and elsewhere in the mid-1980s (Stimson, 2007). However, the underlying principles of this approach can be traced back much further (see box on p. 38). This chapter seeks to explore the emergence and diffusion of harm reduction from a localised, community-based response to international best practice. Since space restricts an exhaustive history transcending all aspects of harm reduction, we will focus primarily on the development and acceptance of approaches to prevent HIV transmission amongst people who inject drugs. It is these interventions that have come to epitomise the essence of harm reduction. For the purposes of this chapter, Europe is defined as comprising 33 countries — the 27 Member States of the European Union (EU), the candidate countries (Croatia, the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia and Turkey), and Norway, Switzerland and Iceland.

Early examples of ‘harm reduction’ principles and practice

1912 to 1923 Narcotic maintenance clinics in the United States.

1926 Report of the United Kingdom Departmental Committee on Morphine and Heroin Addiction (the Rolleston Committee) concluded in support of opiate prescription to help maintain normality for heroin-dependent patients.

1960s Emergence of ‘controlled drinking’ as an alternative to abstinence-based treatments for some alcohol users.

1960s on Grass-roots work on reducing harms connected to the use of LSD, cannabis, amphetamines, and to glue sniffing.

The diffusion of harm reduction in Europe

In 1985 HIV antibody tests were introduced, leading to the discovery of high rates of infection in numerous European cities among people who inject drugs — including Edinburgh (51 %) (Robertson et al., 1986), Milan (60 %), Bari (76 %), Bilbao (50 %), Paris (64 %), Toulouse (64 %), Geneva (52 %) and Innsbruck (44 %) (Stimson, 1995). These localised epidemics occurred in a short space of time, with 40 % or more prevalence of infection reached within two years of the introduction of the virus into drug-injecting communities (Stimson, 1994). Analysis of stored blood samples indicated that HIV was first present in Amsterdam in 1981, and in Edinburgh one or two years later (Stimson, 1991). Heroin use and drug injecting in European countries had been on the increase since the 1960s (Hartnoll

et al., 1989) and research indicated that the sharing of needles and syringes was common amongst people who injected drugs (Stimson, 1991).

It soon became evident that parts of Europe faced a public health emergency (see box below). Across Europe, the response was driven at a city level by local health authorities and civil society (sometimes in spite of interference from government) (O’Hare, 2007a). In 1984

(one year before the introduction of HIV testing), drug user organisations in the Netherlands started to distribute sterile injecting equipment to their peers to counter hepatitis B transmission (Buning et al., 1990; Stimson, 2007). This is widely acknowledged as the first

formal needle and syringe programme (NSP), although informal or ad hoc NSPs existed around the world before 1984. Soon after, the Netherlands integrated NSPs within lowthreshold centres nationwide (Buning et al., 1990).

The transformation brought by HIV and harm reduction HIV and AIDS provide the greatest challenges yet to drug policies and services. Policy-makers and practitioners … have been forced to reassess their ways of dealing with drug problems; this includes clarifying their aims, identifying their objectives and priorities for their work, their styles of working and relationships with clients, and the location of the work. Within the space of about three years, mainly between 1986 and 1988, there have been major debates about HIV, AIDS and injecting drug use. In years to come, it is likely that the late 1980s will be identified as a key period of crisis and transformation in the history of drugs policy.

(Stimson, 1990b)

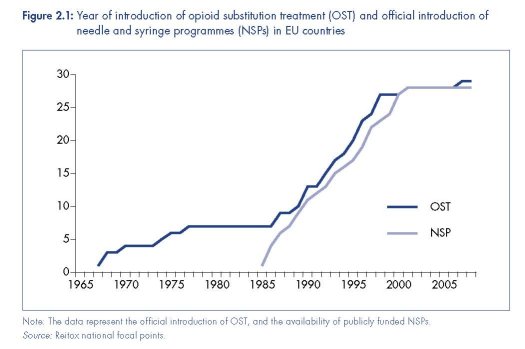

In 1986, parts of the United Kingdom introduced NSPs (Stimson, 1995; O’Hare, 2007b). By 1987, similar programmes had also been adopted in Denmark, Malta, Spain and Sweden (Hedrich et al., 2008). By 1990, NSPs operated in 14 European countries, and were publicly funded in 12. This had increased to 28 countries by the turn of the century, with public funds supporting programmes in all but one of these (EMCDDA, 2009a, Table HSR-4). Some countries were also experimenting with alternative models of distribution, including syringe vending machines and pharmacy-based schemes (Stimson, 1989). By the early 1990s, there was growing evidence of the feasibility of NSPs and in support of the interventions’ ability to attract into services otherwise-hidden populations of people who inject drugs, and reduce levels of syringe sharing (Stimson, 1991).

The spread of NSPs in Europe in the late 1980s and throughout the 1990s was the result of broader policy shifts away from the treatment of dependence and towards the management of the health of people who used drugs (Stimson and Lart, 1990). A focus on health and its risk management increased the emphasis on low-threshold access to services and community-based interventions. Outreach, and especially peer-driven outreach, epitomised these shifts (Rhodes and Hartnoll, 1991; Rhodes, 1993). No longer were services solely reliant upon drug users seeking help for treatment, but instead they reached out to those most hidden and vulnerable as a means of reducing population-wide drug-related risk. In many instances, harm reduction was coordinated at the community or city level (Huber, 1995; Hartnoll and Hedrich, 1996).

These shifts enabled the reshaping of prescribing and drug treatment services towards a more ‘user friendly’ and collaborative model. The practice of prescribing opiates to people dependent on them had been widely adopted as early as the 1920s in the United Kingdom

(Department Committee on Morphine and Heroin Addiction, 1926; Stimson and Oppenheimer, 1982). Methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) was introduced in Europe in the 1960s; first in Sweden, then in the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and Denmark (Hedrich et al., 2008), albeit with limited provision and often in the context of abstinenceorientated programmes. The emergence of HIV in the mid-1980s served to reinvigorate this intervention, combining it with outreach-based models, such as the ‘methadone by bus’ project in Amsterdam (Buning et al., 1990). The number of European countries with MMT rapidly increased throughout the 1990s (see Figure 2.1).

By the 1990s, harm reduction was becoming endorsed as part of national drug policies in many European countries, although some were slower to follow suit (including Germany, Greece and France, which maintained abstinence-based policies) (Michels et al., 2007; Stimson, 1995; Bergeron and Kopp, 2002). It took over a decade, however, for the EU to agree, for the first time, a ‘Drugs strategy’ (European Union, 2000a) with an associated ‘Action plan’ (European Union, 2000b), for the period 2000–04, containing a number of concrete targets. National drug policies across Europe have always been the individual responsibility of Member States, and as such the EU’s role is a ‘co-ordinating, complementary and supporting one’ (Hedrich et al., 2008), creating frameworks rather than legally binding instruments. This first EU drugs strategy presented six recommended targets, one of which was ‘to reduce substantially over five years the incidence of drug-related health damage (including HIV and hepatitis) and the number of drug-related deaths’ (European Union,

2000a). Although the document did not explicitly use the term harm reduction, this target represents an important milestone in European drug policy.

The next milestone came in 2003, when the Council of the European Union adopted a recommendation on the prevention and reduction of health-related harm associated with drug dependence. This stated that Member States should set the reduction of drug-related risks as a public health objective and listed some of the key harm reduction measures to ‘reduce substantially the incidence of drug-related health damage’ (see box below). In 2004 a new eight-year EU drugs strategy (2005–12) was adopted, which explicitly aimed for a ‘Measurable reduction of ... drug-related health and social risks’ through a comprehensive system ‘including prevention, early intervention, treatment, harm reduction, rehabilitation and social reintegration measures within the EU Member States’ (European Union, 2004).

Council Recommendation of 18 June 2003 on the prevention and reduction of health-related harm associated with drug dependence (COM 2003/488/EC)

Member States should, in order to reduce substantially the incidence of drug-related health damage (such as HIV, hepatitis B and C and tuberculosis) and the number of drug-related deaths, make available, as an integral part of their overall drug prevention and treatment

policies, a range of different services and facilities, particularly aiming at risk reduction; to this end, bearing in mind the general objective, in the first place, to prevent drug abuse, Member States should:

1. provide information and counselling to drug users to promote risk reduction and to facilitate their access to appropriate services;

2. inform communities and families and enable them to be involved in the prevention and reduction of health risks associated with drug dependence;

3. include outreach work methodologies within the national health and social drug policies, and support appropriate outreach work training and the development of working standards and methods; outreach work is defined as a community-oriented activity undertaken in

order to contact individuals or groups from particular target populations, who are not effectively contacted or reached by existing services or through traditional health education channels;

4. encourage, when appropriate, the involvement of, and promote training for, peers and volunteers in outreach work, including measures to reduce drug-related deaths, first aid and early involvement of the emergency services;

5. promote networking and cooperation between agencies involved in outreach work, to permit continuity of services and better users’ accessibility;

6. provide, in accordance with the individual needs of the drug abuser, drug-free treatment as well as appropriate substitution treatment supported by adequate psychosocial care and rehabilitation, taking into account the fact that a wide variety of different treatment

options should be provided for the drug-abuser;

7. establish measures to prevent diversion of substitution substances while ensuring appropriate access to treatment;

8. consider making available to drug abusers in prison access to services similar to those provided to drug abusers not in prison, in a way that does not compromise the continuous and overall efforts of keeping drugs out of prison;

9. promote adequate hepatitis B vaccination coverage and prophylactic measures against HIV, hepatitis B and C, tuberculosis and sexually transmitted diseases, as well as screening for all the aforementioned diseases among injection drug users and their immediate social networks, and take the appropriate medical actions;

10. provide where appropriate, access to distribution of condoms and injection materials, and also to programmes and points for their exchange;

11. ensure that emergency services are trained and equipped to deal with overdoses;

12. promote appropriate integration between health, including mental health, and social care, and specialised approaches in risk reduction;

13. support training leading to a recognised qualification for professionals responsible for the prevention and reduction of health-related risks associated with drug dependence.

(Council of the European Union, 2003)

During this time, the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) established itself as a core instrument for the monitoring of evidence related to patterns of drug use and policy in the EU. Founded in 1993, and building upon work by the Pompidou Group of the Council of Europe, the EMCDDA generated the first EU-wide overviews of harm reduction activity at the turn of the century (for example, EMCDDA, 2000). As the EU grew, newer Member States began to develop national drug monitoring systems to feed into this process. In addition, it has been argued that ‘there is clear evidence that “EU drugs guidance” was a model for national policies’ for newer Member States (Commission of the European Communities, 2007; Hedrich et al., 2008, p. 513). By 2009, there was explicit support for harm reduction in national policy documents in all 27 EU Member States, as well as in Croatia, the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Norway and Switzerland (Cook, 2009). This convergence towards a ‘common position’ (Hedrich et al., 2008, p. 513) has allowed the EU to be a strong advocate for harm reduction at international fora (see also MacGregor and Whiting, 2010).

The diffusion of harm reduction beyond Europe

In Australia, medical experts learned of NSPs in the Netherlands through a letter in the medical journal The Lancet, and in 1985 ‘harm minimisation’ was universally adopted as a national policy (Wellbourne-Wood, 1999). In 1987, the Canadian Government adopted harm

reduction as the framework for the National Drug Strategy (Canadian AIDS Society, 2000), and in the United States the first NSPs appeared before 1988 despite long-standing federal opposition to policies of harm reduction (Sherman and Purchase, 2001; Lane, 1993; Watters, 1996). In many US states, in the absence of legally endorsed needle and syringe distribution, some activist groups also began distributing bleach for cleaning syringes (Watters, 1996; Moss, 1990). The first harm reduction project in Latin America started in Brazil in 1989 (Bueno, 2007). Three years later, the HIV/AIDS Prevention Program for Drug Users was established in Buenes Aires. Touze et al. (1999) attributes ‘the increasing amount of information on international harm reduction experiences in the mass media’ as one of five

contributory factors to the adoption of harm reduction in Argentina.

Much international attention was focused on selected European cities, especially Amsterdam (where a city official was hired to manage the demand for visits), and Liverpool, which hosted the first ‘International Conference on the Reduction of Drug Related Harm’ in 1990

(O’Hare, 2007b). In the same year, Frankfurt also hosted the first ‘Conference of European Cities in the Centre of the Drug Trade’. New networks and alliances of cities and experts were emerging within and beyond Europe (including, in 1996, the International Harm Reduction Association). Bilateral funding and support from European governments also began to focus on harm reduction in the developing world (for example, the Asian Harm Reduction Network was founded in 1996 with support from the Dutch Government).

At a global level, the World Health Organization (WHO) was one of the first multilateral bodies to endorse the underlying principles of harm reduction in a meeting in Stockholm in 1986 (WHO, 1986). As early as 1974, the WHO Expert Committee on Drug Dependence

reticence or ambiguity. Since the turn of the century, however, harm reduction appears firmlyhad made reference to ‘concern for preventing and reducing problems rather than just drug use’ (Wodak, 2004). Other agencies of the United Nations system — including UNAIDS (the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, established in 1996) — showed greater entrenched in the international policy dialogue (United Nations General Assembly, 2001; International Harm Reduction Association, 2009b).

In 2001, a meeting of the United Nations (UN) General Assembly (the chief policy-making body of the United Nations) adopted a ‘Declaration of Commitment’, which explicitly stated that ‘harm reduction efforts related to drug use’ should be implemented by Member States

(United Nations General Assembly, 2001). Two years later, the WHO commissioned a review of scientific evidence on the effectiveness of harm reduction interventions targeting people who inject drugs, which was published in 2005 (WHO, 2005a; Wodak and Cooney, 2005; Farrell et al., 2005; Needle et al., 2005). That same year, methadone and buprenorphine were added to the WHO list of ‘essential medicines’ (WHO, 2005b), and UNAIDS released a position paper entitled ‘Intensifying HIV Prevention’ that listed a core package of harm reduction interventions (UNAIDS, 2005a) — later expanded to become the ‘comprehensive harm reduction package’ (WHO, 2009).

In December 2005, the UN General Assembly adopted a resolution requesting that UNAIDS assist in ‘scaling-up HIV prevention, treatment, care and support with the aim of coming as close as possible to the goal of universal access to treatment by 2010 for all those who need it’ (United Nations General Assembly, 2006). This led to the development of WHO, UNAIDS and UNODC guidelines on national target setting and programming on HIV prevention, treatment and care for injecting drug users, and focused advocacy efforts on the need for greater coverage towards ‘universal access’ (Donoghoe et al., 2008).

In contrast to the United Nations’ HIV/AIDS response, there has been notably less support for harm reduction from the various UN drug control agencies. Within the UNAIDS programme, UNODC is the lead agency on the ‘Prevention of transmission of HIV among injecting drug users and in prisons’ (UNAIDS, 2005b) but this role remains overshadowed by its parallel remit to control the production and supply of illicit drugs. In addition, UNODC’s governing body — the Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND) — has seen ongoing resistance to harm reduction from some countries (including Japan, Russia and the United States), creating incoherence on a global policy position for harm reduction across the UN system (Hunt, 2008). The International Narcotics Control Board (the expert advisory body monitoring compliance with the UN Drug Conventions) has also regularly questioned the legality of some harm reduction interventions (Csete and Wolfe, 2007). Most recently, in 2009, CND adopted a draft ten-year ‘Political Declaration’ on drug control that (after months of negotiation and despite advocacy efforts from civil society, the UNAIDS Executive Director, and two UN Special Rapporteurs) resisted requests to include the term harm reduction (United Nations Commission on Narcotic Drugs, 2009; see also MacGregor and Whiting, 2010). Despite this, however, there were 84 countries around the world supporting harm reduction in either policy or practice by 2009, spanning every continent and including 31 European countries (Cook, 2009).

Current harm reduction practice in Europe

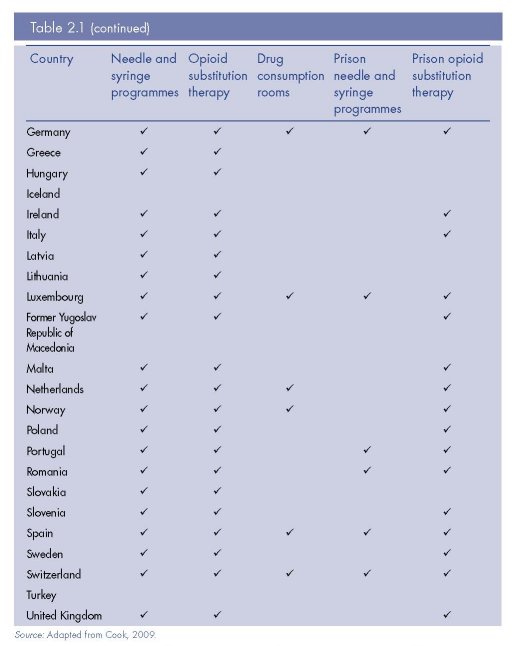

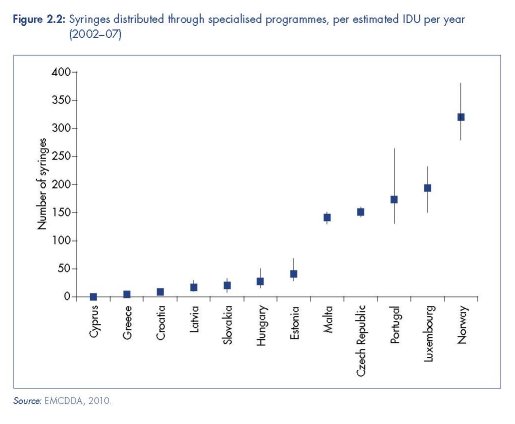

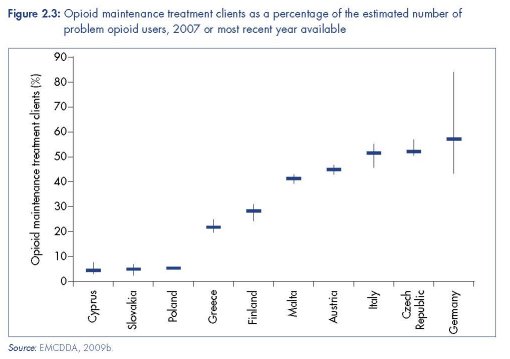

Europe remains one of the regions most supportive of harm reduction policy and practice, including through bilateral support from European governments to programmes in low- and middle-income countries. Yet there is still considerable variation within Europe in the extent and nature of harm reduction, and the coverage these interventions achieve among targeted populations (see Table 2.1, Figure 2.2 and Figure 2.3). We synthesise here current harm reduction practices in Europe, focusing on access to sterile injecting equipment, opioid substitution treatment and drug consumption rooms (DCRs) (see also Donoghoe et al., 2008; Aceijas et al., 2007; Kimber et al., 2010; Hedrich et al., 2010).

Access to sterile injecting equipment in Europe

By 2009, there were 77 countries and territories worldwide with at least one operational NSP, and 31 of these countries were European (Cook, 2009). With the exception of Iceland and Turkey, every European country where injecting drug use had been reported had one or

more NSP (see Table 2.1). The most recent EU Member to begin providing sterile injecting equipment to people who inject drugs was Cyprus in 2007. Across the region, sterile injecting equipment is delivered through community-based specialist drugs services, pharmacies and outreach (including peer outreach), although not all service delivery models are employed in all countries. For example, access to free injecting equipment is only available through pharmacies in Northern Ireland, and two hospital-based outlets in Sweden (EMCDDA, 2009a, Table HSR-4). Syringe sales are legal in all countries, except in Sweden.

In 2007, subsidised pharmacy-based syringe distribution was available in 12 countries: Austria, Belgium, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Greece, the Netherlands, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain and the United Kingdom. Seven countries also used syringe vending machines (Austria, Denmark, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy and Luxembourg) and several had mobile service provision (EMCDDA, 2009a, Table HSR-4).

Cross-country comparisons of coverage require robust reporting systems and harmonised indicators. While more robust than the data estimates available in other regions of the world, information remains unavailable for some European countries and patchy in others

(EMCDDA, 2009a, Table HSR-5). In addition, estimating intervention ‘coverage’ — the proportion of target populations reached by harm reduction interventions, ideally with sufficient intensity to have probable impact — requires estimates of target population prevalence and intervention dose that are often unavailable or of dubious reliability (Heimer, 2008; Aceijas et al., 2007; Sharma et al., 2008). While most European countries have estimates of the prevalence of problem drug use, far fewer have specific estimates of the prevalence of drug injecting (EMCDDA, 2009a, Table PDU-1).

Available data indicates substantial variation in NSP coverage across the region (Figure 2.2). Even when comparing the number of NSP sites nationwide, an indicator that does not take into account the size of injecting populations, or factors impeding service access, they vary from several thousand (France), several hundred (United Kingdom, Portugal, Spain) to fewer than five (Cyprus, Greece, Romania and Sweden) (Cook and Kanaef, 2008). A number of European countries are providing over 150 syringes per injector per year through specialist NSPs (for example, the Czech Republic, Portugal, Norway and Luxembourg) (EMCDDA, 2010) — levels of coverage that may contribute to the aversion or reduction of HIV epidemics (Vickerman et al., 2006). However, this is by no means consistent throughout Europe, and coverage is almost negligible in some countries (Figure 2.2). In Sweden (one of the first countries to establish NSPs in Europe), there are only two NSP sites, and the intervention reaches approximately 1 200 people; just 5 % of the estimated total number of people who inject drugs in the country (Svenska Brukarföreningen et al., 2007; Olsson et al., 2001).

In addition, national NSP coverage estimates often hide dramatic geographical coverage variations, with provision in many cities, towns and rural areas woefully inadequate. In France, for example, there are no specialist drugs facilities with NSPs in some cities with a

population over 100 000 and with known injecting drug use (ASUD, 2008).

Figure 2.2 illustrates that many people injecting drugs in Europe have inadequate access to subsidised or free syringes from NSPs. In several countries, current coverage levels are not high enough to avert or reverse an HIV epidemic in the IDU population (Vickerman et al.,

2006; Heimer et al., 2008). It should be noted, however, that pharmacy sales of injecting equipment are not captured in Figure 2.2 and may be a common source of syringes for some people using drugs in the region.

Several countries have larger numbers of non-specialist pharmacy-based NSPs than specialist agencies (EMCDDA, 2006, Table NSP-1), and some (for example, Northern Ireland and Sweden) rely only on one type of outlet. Specialist NSPs, however, may provide more than needles and syringes alone, including a greater intensity of harm reduction advice and education, referrals into drug and HIV treatment, and a wider range of injecting equipment (including ‘spoons’ or ‘cookers’, water, filters, alcohol pads, tourniquets, condoms, acidic

powders for dissolving drugs, and aluminium foil or inhalation pipes to assist ‘route transitions’ from injecting to smoking). Among the common developments in Europe is a diversification of outlets for needle and syringe exchange, which also provides a basis for scaling up syringe provision. In most countries several types of legal syringe sources, including NSPs, pharmacies and mobile units, are available to meet the needs of people who inject drugs.

Access to sterile injecting equipment in European prisons

Despite evidence-based reviews of effectiveness and recommendations for implementation (WHO, 2005a; Kimber et al., 2010), only 10 countries worldwide have introduced needle and syringe programmes (NSPs) in prisons. Six of these countries are European: Germany, Luxembourg, Portugal, Romania, Spain and Switzerland. The first prison NSP was introduced in Switzerland in 1992, followed four years later by Germany, and then Spain in 1997. Service models vary between prisons and include ‘one-to-one’ exchanges implemented by medical staff, exchanges operated by external NGOs or by peer workers, and the use of automated syringe vending machines.

The number of prisoners with access to this intervention varies across the region, but only in Spain have syringe programmes been made available across a national prison system. In recent years, Spain has scaled-up the availability, while in Germany a change in government led to the closure of six prison-based syringe programmes, leaving only one (WHO, 2005c). In 2009, Belgium and Scotland were in the process of developing pilot programmes. Researchers on this issue have concluded that the poor availability of this intervention in Europe ‘cannot be based on logic’ (Stöver et al., 2008a, p. 94).

Drug consumption rooms in Europe

With the exception of one Canadian and one Australian facility, all DCRs are operating in European countries (see Hedrich et al., 2010). Germany, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain and Switzerland have an estimated 90 DCRs collectively, spanning 59 European cities (with the majority in the Netherlands and Germany). These facilities, which are usually integrated into low-threshold drugs agencies, allow the smoking and/or injecting of drugs under supervision by trained staff and without fear of arrest. In 2007, there were an estimated 13 727 supervised consumptions in Luxembourg’s sole DCR and 11 600 in Norway’s single facility. In Germany, large numbers of supervised consumptions occurred in Frankfurt (171 235 in 2007), Berlin (12 000 in 2006) and Hannover (29 332 in 2006). Despite positive evaluations, these facilities remain controversial both within Europe and elsewhere (Hedrich et al., 2010).

Access to opioid substitution treatment in Europe

By 2009, there were 65 countries and territories worldwide that provided opioid substitution treatment (OST) for drug dependence, almost half of which were in Europe (Cook, 2009). All European countries where injecting drug use is reported, with the exception of Iceland and Turkey, prescribe methadone and/or buprenorphine as treatment for opioid dependence (see Table 2.1).

In 2007, more than 650 000 opioid users were estimated to have received OST in Europe, with huge national variations in coverage (EMCDDA, 2009b). England and Wales, Italy and France were each prescribing the treatment to more than 100 000 people. Methadone is the most commonly prescribed OST medicine across the region, with the exceptions of Croatia, the Czech Republic, Cyprus, France, Finland, Latvia and Sweden, where high-dosage buprenorphine is used and Austria, where slow-release morphine is used more often

(EMCDDA, 2009a, Table HSR-3). In general, the volume of OST prescribing increased between 2003 and 2007, with the most dramatic increases in Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Finland, Latvia and Norway. Decreases have been reported in Spain and a

stabilisation of the demand for OST seemed also to take place in France, Luxembourg and the Netherlands (see EMCDDA, 2009a, HSR Tables).

The coverage of OST provision varies greatly across the region. While countries such as Spain and the United Kingdom have large numbers of OST sites (2 229 and 1 030 respectively; EMCDDA, 2009c; United Kingdom National Treatment Agency, 2007), at least 10 European countries have fewer than 20 sites providing OST (EMCDDA, 2009c). Where estimates of the prevalence of problem drug use and data on clients in substitution treatment are available, the coverage of OST can be calculated (see Figure 2.3). While these estimates must be interpreted with caution due to uncertainties in both values, the results indicate significant variations in coverage across the EU — from 5 % in Cyprus and Slovakia to around 50 % in the Czech Republic, Germany and Italy. In a recent UN target-setting guide, reaching 40 % or more of people using opioids problematically with OST is cited as ‘good coverage’ (WHO et al., 2009).

Even where OST is available, several factors influence the effective utilisation of services. Long waiting lists, limited treatment slots, strict adherence policies, and an unwillingness of general practitioners to prescribe OST are all reported to impact upon accessibility in

European countries. The costs attached to OST, the lack of ‘take-home’ doses and, in some cases, the need for medical insurance also act as barriers (Cook and Kanaef, 2008).

A number of European countries have remained at the forefront of innovation with regards to OST and drug dependence therapies. For those who cannot or do not wish to stop injecting, a small number of European countries prescribe injectable OST medicines (including the Netherlands, Switzerland and the United Kingdom) (Cook and Kanaef, 2008). The prescription of pharmaceutical heroin (diacetylmorphine) remains limited to a few European countries (Fischer et al., 2007; EMCDDA, 2009a, Table HSR-1). Despite positive findings from

randomised controlled trials in several countries (indicating that diacetylmorphine is effective, safe, and cost-effective, and can reduce drug-related crime and improve patient health), only Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, Switzerland and the United Kingdom include this intervention as part of the national response to drugs. Pilot programmes are currently underway in Belgium and Luxembourg (EMCDDA, 2009a, Table HSR-1).

Access to opioid substitution treatment in European prisons

European countries make up a large proportion of those worldwide that offer OST to prisoners; 23 countries in Europe out of 33 globally (Table 2.1). However, there are ‘heterogeneous and inconsistent regulations and treatment modalities throughout Europe’, and practice varies within countries and from prison to prison (Stöver et al., 2006). OST is available in the majority of prisons in Austria, Belgium, Croatia, Denmark, Luxembourg, Malta, Portugal, Slovenia and Spain (EMCDDA, 2009a, Figure HSR-2). It remains limited to specific geographical areas or a small proportion of prisons elsewhere in the region. In France, buprenorphine is more widely available in prisons than methadone (as is the case in the community), but this is still restricted to certain prisons (van der Gouwe et al., 2006). Latest estimates show that the national prison system of Spain provided OST to 19 010 prisoners, the highest number reported in Europe. Far fewer prisoners were receiving OST in other countries, including Ireland (1 295), Portugal (707), Belgium (300), Luxembourg (191), Finland (40), Serbia (10) and Montenegro (5) (Cook and Kanaef, 2008). Switzerland is the only country globally providing heroin (diacetylmorphine) maintenance to prisoners, although this is limited to two facilities (Stöver et al., 2008b).

The availability and provision of OST in European prisons has increased in recent years, but the regulations and practices surrounding prison OST vary greatly, leading to gaps between treatment need and provision. For example, prison OST is often subject to overly strict inclusion criteria, resulting in relatively few prisoners being able to access it (BISDRO and WIAD, 2008). Medical risks associated with disruption of long-term maintenance treatment when serving prison sentences remain an issue where OST is not available to prisoners (BISDRO and WIAD, 2008). The difference compared to the availability of OST in the community is particularly striking (EMCDDA, 2009a, Figure HSR-2). Four decades after the introduction of community OST in Europe and following the considerable scale-up in the past two decades, the gap between treatment provision inside and outside prison walls has further increased.

Conclusion

Key messages

• Harm reduction became widely established as a response to HIV/AIDS in the 1980s.

• Early policy and practice was pioneered by a number of European cities.

• By 2009, some 31 countries in Europe had needle and syringe programmes, and 31 had opioid substitution treatment.

• Of the European countries reporting injecting drug use, only Iceland and Turkey have not implemented harm reduction measures.

• Europe had a significant impact on the diffusion of harm reduction globally, and in 2009 there were 84 countries around the world that endorsed harm reduction in policy or practice.

• The European Union has played a crucial role in promoting and supporting harm reduction at the United Nations.

Since the mid-1980s, harm reduction has transformed from a peer-driven, grass-roots approach to an official policy of the United Nations, with Europe playing a leading role. European countries were among the ‘earlier adopters’ of harm reduction, facilitating its diffusion throughout Europe and beyond. Countries in Europe remain among the forerunners of innovations in harm reduction practice and technology — for example, developing new NSP products (such as coloured syringes to reduce sharing; Exchange Supplies, n.d.) and

interventions to encourage transitions away from injecting (Pizzey and Hunt, 2008), delivering NSP and OST in prisons, and establishing DCRs. At the same time, definitions of harm reduction are expanding to embrace the need to protect the rights to health and access to

services of people who use drugs, and to protect them from harmful drug policies, and Europe remains central to this dialogue and advocacy. There are now two decades of research and evaluation exploring the feasibility and impact of harm reduction interventions, especially among people who inject drugs (Kimber et al., 2010; Palmateer et al., 2010; Wiessing et al., 2009; Wodak and Cooney, 2005; Farrell et al., 2005; Institute of Medicine, 2007).

Yet harm reduction practice and policy varies across Europe (see also MacGregor and Whiting, 2010). Where national harm reduction responses are well established, these may be threatened by governmental changes. The global politics of drug use continue to be

polarised. One recent instance of this was the non-inclusion of the term ‘harm reduction’ in the ‘Political Declaration’ of the 2009 Commission on Narcotic Drugs, prompting a coalition of twenty-five UN Member States (the majority being EU countries) to announce that they

would interpret sections of the Declaration to nonetheless mean harm reduction (International Drug Policy Consortium, 2009). The need for networking, exchange and coordination within Europe remains if policies of harm reduction in Europe and beyond are to be defended, strengthened and properly evaluated.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dagmar Hedrich and Lucas Wiessing from EMCDDA for their feedback and comments. In addition, we would also like to thank Cinzia Bentari, Esther Croes, Pat O’Hare, Tuukka Tammi, Daan van der Gouwe, Annette Verster and Alex

Wodak.

References

Aceijas, C., Stimson, G. V., Hickman, M. and Rhodes, T., United Nations Reference Group on HIV/AIDS Prevention and Care among IDU in Developing and Transitional Countries (2004), ‘Global overview of injecting drug use and HIV infection among injecting drug users’, AIDS 18 (17), Nov. 19, pp. 2295–303.

Aceijas, C., Hickman, M., Donoghoe, M. C., Burrows, D. and Stuikyte, R. (2007), ‘Access and coverage of needle and syringe programmes (NSP) in Central and Eastern Europe and Central Asia’, Addiction 102 (8), pp. 1244–50.

ASUD (French National Association for the Safety of Drug Users) (2008), ‘Global state of harm reduction qualitative data response’, in Cook, C. and Kanaef, N., Global state of harm reduction: mapping the response to drug-related HIV and hepatitis C epidemics, International Harm Reduction Association, London.

Bergeron, H., and Kopp, P. (2002), ‘Policy paradigms, ideas, and interests: the case of the French public health policy toward drug abuse’, The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 582 (1), pp. 37–48.

Bueno, R. (2007), ‘The Latin American harm reduction network (RELARD): successes and challenges’, International Journal of Drug Policy 18, pp. 145–7.

Buning, E. C., Van Brussel, G. H. and Van Santen, G. (1990), ‘The “methadone by bus” project in Amsterdam’, British Journal of Addiction 85, pp. 1247–50.

Canadian AIDS Society (2000), Position statement: harm reduction and substance use. Available at www.cdnaids. ca/web/setup.nsf/(ActiveFiles)/PS_Harm_Reduction_and_Substance_Use/$file/Harm_Reduction_and_ Substance_Use_En_Red.pdf.

Cook, C. (2009), Harm reduction policies and practices worldwide: an overview of national support for harm reduction in policy and practice, International Harm Reduction Association, London.

Cook, C. and Kanaef, N. (2008), Global state of harm reduction: mapping the response to drug-related HIV and hepatitis C epidemics, International Harm Reduction Association, London.

Council of the European Union (2003), ‘Council Recommendation of 18 June 2003 on the prevention and reduction of health-related harm associated with drug dependence’, Official Journal of the European Union 3 Jul, L165 (46). Available at http://eur-lex.europa.eu/JOHtml.do?uri=OJ:L:2003:165:SOM:EN:HTML.

Csete, J. and Wolfe, D. (2007), Closed to reason: the International Narcotics Control Board and HIV/AIDS, Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network and the International Harm Reduction Development Program of the Open Society Institute, Toronto/New York, p. 3.

Department Committee on Morphine and Heroin Addiction (1926) Report. Available at www.drugtext.org/index. php/en/reports/220.

Donoghoe, M., Verster, A., Pervilhac, C. and Williams, P. (2008), ‘Setting targets for universal access to HIV prevention, treatment and care for injecting drug users (IDUs): towards consensus and improved guidance’, International Journal of Drug Policy 19 (Supplement 1), pp. S5–S14.

EMCDDA (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction) (2000), Reviewing current practice in substitution treatment, Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, Luxembourg.

EMCDDA (2006), Table NSP-1: Number of syringe provision outlets and number of syringes (in thousands) exchanged, distributed or sold 2003, Statistical bulletin 2006. Available at http://stats06.emcdda.europa.eu/en/elements/nsptab02-en.html.

EMCDDA (2008), National drug related research in Europe, Selected issue, EMCDDA, Lisbon.

EMCDDA (2009a), Statistical bulletin 2009, Available at http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/stats09. Tables HSR ‘Health and social responses’. Available at http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/stats09/hsr. Tables PDU ‘Problematic drug use population’. Available at http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/stats09/pdu.

EMCDDA (2009b), Annual report 2009: the state of the drugs problem in Europe, EMCDDA, Lisbon.

EMCDDA (2009c), Drug treatment overviews. Available at www.emcdda.europa.eu/responses/treatmentoverviews.

EMCDDA (2010), Trends in injecting drug use in Europe, Selected issue, European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, Lisbon.

European Commission (2007), ‘Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council on the implementation of the Council Recommendation of 18 June 2003 on the prevention and reduction of healthrelated harm associated with drug dependence’, COM (2007) 199 final (eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/site/en/ com/2007/com2007_0199en01.pdf).

European Union (2000a), European Union Drug Strategy 2000–2004. Available at http://www.emcdda.europa. eu/html.cfm/index2005EN.html.

European Union (2000b), The European Union Action Plan on Drugs 2000–2004. Available at http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/html.cfm/index1338EN.html.

European Union (2004), European Union Drugs Strategy 2005–2012. Available at http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/html.cfm/index6790EN.html.

Exchange Supplies (n.d.), Nevershare syringe. Available at http://www.exchangesupplies.org/needle_exchange_ supplies/never_share_syringe/never_share_syringe_intro.html.

Farrell, M., Gowing, L., Marsden, J., Ling, W. and Ali, R. (2005), ‘Effectiveness of drug dependence treatment in HIV prevention’, International Journal of Drug Policy 16 (Supplement 1), pp. S67–S75.

Fischer, B., Oviedo-Joekes, E., Blanken, P., et al.. (2007), ‘Heroin-assisted treatment (HAT) a decade later: a brief update on science and politics’, Journal of Urban Health 84, 552–62.

Greenwald, G. (2009), Drug decriminalization in Portugal: lessons for creating fair and successful drug policies, Cato Institute, USA.

Hartnoll, R. and Hedrich, D. (1996), ‘AIDS prevention and drug policy: dilemmas in the local environment’, in Rhodes, T. and Hartnoll, R. (eds) AIDS, drugs and prevention: perspectives on individual and community action, Routledge, London, pp. 42–65.

Hartnoll, R., Avico, U., Ingold, F. R., et al. (1989), ‘A multi-city study of drug misuse in Europe’, Bulletin on Narcotics 41, pp. 3–27.

Hedrich, D., Pirona, A. and Wiessing, L. (2008), ‘From margins to mainstream: the evolution of harm reduction responses to problem drug use in Europe’, Drugs: education, prevention and policy 15, pp. 503–17.

Hedrich, D., Kerr, T. and Dubois-Arber, F. (2010), ‘Drug consumption facilities in Europe and beyond’, in European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA), Harm reduction: evidence, impacts and challenges, Rhodes, T. and Hedrich, D. (eds), Scientific Monograph Series No. 10, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

Heimer, R. (2008), ‘Community coverage and HIV prevention: assessing metrics for estimating HIV incidence through syringe exchange’, International Journal of Drug Policy 19 (Supplement 1), pp. S65–S73.

Huber, C. (1995), ‘Needle park: what can we learn from the Zürich experience?’ Addiction 90, pp. 291–2.

Hunt, P. (2008), Human rights, health and harm reduction: states’ amnesia and parallel universes: an address by Professor Paul Hunt, UN Special Rapporteur on the right to the highest attainable standard of health, Harm Reduction 2008: IHRA’s 19th International Conference, Barcelona — 11 May 2008, International Harm Reduction Association, London.

IHRA (International Harm Reduction Association) (2009a), What is harm reduction? A position statement from the International Harm Reduction Association, International Harm Reduction Association, London.

IHRA (2009b), Building consensus: a reference guide to human rights and drug policy, International Harm Reduction Association, London.

IHRA (2009c), German parliament votes in favour of heroin assisted treatment. Available at www.ihra.net/June200 9#GermanParliamentVotesinFavourofHeroinAssistedTreatment.

IHRA and Human Rights Watch (2009), Building consensus: a reference guide to human rights and drug policy, International Harm Reduction Association, London, pp. 18–19. Institute of Medicine (2007), Preventing HIV infection among injecting drug users in high risk countries: an assessment of the evidence, Committee on the Prevention of HIV Infection Among Injecting Drug Users in High-Risk Countries, National Academies Press, Washington.

International Drug Policy Consortium (2009), ‘The 2009 Commission on Narcotic Drugs and its high level segment: report of proceedings’, IDPC Briefing Paper, April.

Kazatchkine, M. and McClure, C. (2009), From evidence to action: reflections on the global politics of harm reduction and HIV, International Harm Reduction Association, London.

Kimber, J., Palmateer, N., Hutchinson, S., et al. (2010), ‘Harm reduction among injecting drug users: evidence of effectiveness’, in European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA), Harm reduction: evidence, impacts and challenges, Rhodes, T. and Hedrich, D. (eds), Scientific Monograph Series No. 10, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

Lane, S. D. (1993), Needle exchange: a brief history. Available at www.aegis.com/law/journals/1993/ HKFNE009.html.

MacGregor, S. and Whiting, M. (2010), ‘The development of European drug policy and the place of harm reduction within this’, in European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA), Harm reduction: evidence, impacts and challenges, Rhodes, T. and Hedrich, D. (eds), Scientific Monograph Series No. 10, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

Michels, I. I., Stöver, H. and Gerlach, R. (2007), ‘Substitution treatment for opiate addicts in Germany’, Harm Reduction Journal 4 (5). Available at http://www.harmreductionjournal.com/content/4/1/5.

Moss, A. (1990), ‘Control of HIV infection in injecting drug users in San Francisco’, in Strang, J. and Stimson, G.

V., AIDS and drug misuse: the challenge for policy and practice in the 1990s, Routledge, London.

Needle, R. H., Burrows, D., Friedman, S. R., et al. (2005), ‘Effectiveness of community-based outreach in

preventing HIV/AIDS among injecting drug users’, International Journal of Drug Policy 16 (Supplement 1), pp.

45–57.

O’Hare, P. (2007a), ‘Harm reduction in the Mersey region’, International Journal of Drug Policy 18, p. 152.

O’Hare, P. (2007b), ‘Merseyside: the first harm reduction conferences and the early history of harm reduction’,

International Journal of Drug Policy 18, pp. 141–4.

Olsson, B., Adamsson Wahren, C. and Byqvist, S. (2001), Det tunga narkotikamissbrukets omfattning I Sverige

1998, CAN, Stockholm.

Palmateer, N., Kimber, J., Hickman, M., et al. (2010), ‘Preventing hepatitis C and HIV transmission among

injecting drug users: a review of reviews’, Addiction, in press.

Pizzey, R. and Hunt, N. (2008), ‘Distributing foil from needle and syringe programmes (NSPs) to promote

transitions from heroin injecting to chasing: an evaluation’, Harm Reduction Journal 5, p. 24.

Rhodes, T. (1993), ‘Time for community change: what has outreach to offer?’, Addiction 88, pp. 1317–20.

Rhodes, T. and Hartnoll, R. (1991), ‘Reaching the hard to reach: models of HIV outreach health education’, in

Aggleton, P., Davies, P. and Hart, G. (eds), AIDS: responses, interventions and care, Falmer Press, London.

Robertson, J. R., Bucknall, A. B. V., Welsby, P. D., et al. (1986), ‘Epidemic of AIDS-related virus (HTLV-III/LAV)

infection among intravenous drug abusers’, British Medical Journal 292, p. 527.

Sharma, M., Burrows, D. and Bluthenthal, R. (2008), ‘Improving coverage and scale-up of HIV prevention,

treatment and care for injecting drug users: moving the agenda forward’, International Journal of Drug Policy 19

(Supplement 1), pp. 1–4.

Sherman, S. G. and Purchase, D. (2001) ‘Point defiance: a case study of the United States’ first public needle

exchange in Tacoma, Washington’, International Journal of Drug Policy 12, pp. 45–57.

Stimson, G. V. (1989), ‘Syringe exchange programmes for injecting drug users’, AIDS 3, pp. 253–60.

Stimson, G. V. (1990a), ‘AIDS and HIV: the challenge for British drug services’, British Journal of Addiction 85 (3),

pp. 329–39.

Stimson, G. V. (1990b), ‘Revising policy and practice: new ideas about the drugs problem’, in Strang, J. and

Stimson, G., AIDS and drug misuse: the challenge for policy and practice in the 1990s, London, Routledge.

Stimson, G. V. (1991), ‘Risk reduction by drug users with regard to HIV infection’, International Review of Psychiatry

3, pp. 401–15.

Stimson, G. V. (1994), ‘Reconstruction of sub-regional diffusion of HIV infection among injecting drug users in

South East Asia: implications for early intervention’, AIDS 8, pp. 1630–2.

Stimson, G. V. (1995), ‘AIDS and injecting drug use in the United Kingdom, 1987–1993: the policy response and

the prevention of the epidemic’, Social Science and Medicine 41 (5), pp. 699–716.

Stimson, G. V. (2007), ‘Harm reduction — coming of age: a local movement with global impact’, International

Journal of Drug Policy 18, pp. 67–9.

Stimson, G. V. and Lart, R. (1990), ‘HIV, drugs and public health in England: new words, old tunes’, International

Journal of the Addictions 26, pp. 1263–77.

Stimson, G. V. and Oppenheimer, E. (1982), Heroin addiction: treatment and control in Britain, Tavistock, London.

Stöver, H., Casselman, J. and Hennebel, L. (2006), ‘Substitution treatment in European prisons: a study of policies

and practices in 18 European countries’, International Journal of Prisoner Health March, 2 (1), pp. 3–12.

Stöver, H., Weilandt, C., Zurhold, H., Hartwig, C. and Thane, K. (2008a), Final report on prevention, treatment,

and harm reduction services in prison, on reintegration services on release from prison and methods to monitor/

analyse drug use among prisoners, European Commission Directorate — General for Health and Consumers, Drug

Policy and Harm Reduction, SANCO/2006/C4/02.

Stöver, H., Weilandt, C., Huisman, A., et al. (2008b), Reduction of drug-related crime in prison: the impact of

opioid substitution treatment on the manageability of opioid dependent prisoners, BISDRO, University of Bremen,

Bremen.

Svenska Brukarföreningen/Swedish Drug Users Union and International Harm Reduction Association (2007),

Briefing to the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights on the fifth report of Sweden on the implementation

of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, International Harm Reduction Association,

London.

Touze, G., Rossi, D., Goltzman, P., et al. (1999), ‘Harm reduction in Argentina: a challenge to non-governmental

organisations’, International Journal of Drug Policy 10, pp. 47–51.

van der Gouwe, D., Gallà, M., van Gageldonk, A., et al. (2006), Prevention and reduction of health-related harm

associated with drug dependence: an inventory of policies, evidence and practices in the EU relevant to the

implementation of the Council Recommendation of 18 June 2003, Trimbos Instituut, Utrecht.

UNAIDS (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS) (2005a), Intensifying HIV prevention: UNAIDS Policy

Position Paper, UNAIDS, Geneva. Available at http://data.unaids.org/publications/irc-pub06/jc1165-intensif_hivnewstyle_

en.pdf.

UNAIDS (2005b), UNAIDS Technical Support Division of Labour: summary & rationale, UNAIDS, Geneva.

Available at data.unaids.org/una-docs/JC1146-Division_of_labour.pdf

United Kingdom National Treatment Agency (2007), Global state — data collection response. Cited in Cook, C.

and Kanaef, N. (2008), Global state of harm reduction 2008: mapping the response to drug-related HIV and

hepatitis C epidemics, International Harm Reduction Association, London.

United Nations Commission on Narcotic Drugs (2009), Report on the fifty-second session (14 March 2008 and

11–20 March 2009) Economic and Social Council Official Records, 2009: supplement no. 8 — political declaration

and plan of action on international cooperation towards an integrated and balanced strategy to counter the world

drug problem, United Nations Commission on Narcotic Drugs, Vienna.

United Nations General Assembly Sixtieth Special Session (2006), ‘Agenda item 45: resolution adopted by the

General Assembly. 60/262’, Political declaration on HIV/AIDS, New York.

United Nations General Assembly Twenty-Sixth Special Session (2001), ‘Agenda item 8: resolution adopted by

the General Assembly. S-26/2’, Declaration of Commitment on HIV/AIDS, New York.

Vickerman, P., Hickman, M., Rhodes, T. and Watts, C. (2006), ‘Model projections on the required coverage of

syringe distribution to prevent HIV epidemics among injecting drug users’, Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency

Syndromes 42, pp. 355–61.

Watters, J. (1996), ‘Americans and syringe exchange: roots of resistance’, in Rhodes, T. and Hartnoll, R. (eds),

AIDS, drugs and prevention: perspectives on individual and community action, Routledge, London, pp. 22–41.

Wellbourne-Wood, D. (1999), ‘Harm reduction in Australia: some problems putting policy into practice’,

International Journal of Drug Policy 10, pp. 403–13.

Wiessing, L., van de Laar, M. J., Donoghoe, M. C., et al. (2008), ‘HIV among injecting drug users in Europe:

increasing trends in the east’, Eurosurveillance 13 (50). Available at http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.

aspx?ArticleId=19067.

Wiessing, L., Likatavičius, G., Klempová, D., et al. (2009), ‘Associations between availability and coverage of

HIV-prevention measures and subsequent incidence of diagnosed HIV infection among injection drug users’,

American Journal of Public Health 99 (6), pp.1049–52.

Wodak, A. (2004), ‘Letter from Dr Alex Wodak to Dr Zerhouni at the US National Institute of Health NIH’.

Available at www.drugpolicy.org/library/05_07_04wodaknih.cfm.

Wodak, A. and Cooney, A. (2005), ‘Effectiveness of sterile needle and syringe programmes’, International

Journal of Drug Policy 16, S1, pp. S31–S44.

WHO (World Health Organization) (1986), Consultation on AIDS among drug abusers, 7–9 October 1986,

Stockholm, ICP/ADA535(S).

WHO (2005a), Evidence for action series. Available at www.who.int/hiv/pub/idu/idupolicybriefs/en/index.html

and http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2007/9789241595780_eng.pdf.

WHO (2005b), Essential medicines: WHO model list (14th edition). Available at http://whqlibdoc.who.int/

hq/2005/a87017_eng.pdf.

WHO (2005c), Status paper on prisons, drugs and harm reduction, World Health Organization, Copenhagen.

Available at http://www.euro.who.int/document/e85877.pdf.

WHO (2009), HIV/AIDS: comprehensive harm reduction package. Available at http://www.who.int/hiv/topics/

idu/harm_reduction/en/index.html.

WHO, UNODC (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime) and UNAIDS (2009), Technical guide for countries to

set targets for universal access to HIV prevention, treatment and care for injecting drug users, WHO, UNODC/

UNAIDS.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|