Chapter 14 Criminal justice approaches to harm reduction in Europe

| Reports - EMCDDA Harm Reduction |

Drug Abuse

Chapter 14 Criminal justice approaches to harm reduction in Europe

Alex Stevens, Heino Stöver and Cinzia Brentari

Abstract

This chapter reviews the spread of harm reduction services in European criminal justice

systems, and their evaluation. It begins with a discussion of the tensions and contradictions

inherent in providing harm reduction services (which may accept continued drug use) in

criminal justice settings (that do not). It then draws on research carried out for the

Connections project, for its predecessor the European Network on Drug and Infections

Prevention in Prisons and on the information gathered by the European Monitoring Centre

for Drugs and Drug Addiction. It examines services such as needle and syringe exchange,

opiate substitution and distribution of condoms and disinfectants in prisons. It also

examines harm reduction services that have been developed in the context of police

custody, and in the attempt to provide through-care and aftercare to drug users who pass

through the criminal justice system. The chapter concludes that the tensions between harm

reduction and criminal justice aims can be overcome in providing effective services to

reduce drug-related harms.

Keywords: criminal justice systems, harm reduction, prison, decriminalisation, syringe

exchange, opioid substitution treatment, arrest-referral.

Introduction

Harm reduction is often seen as conflicting with the use of law enforcement to reduce drug

use, but there are ways in which policies and practice can develop in order to reduce harms

related to drugs within the criminal justice system. The principle of harm reduction may also

be applied to law enforcement itself. Drug prohibition can inadvertently increase the

harmfulness of drug use as it means that users rely on illicit forms of supply and consume

drugs of unknown purity and quality in a risky manner. It also creates artificially high prices,

which stimulate acquisitive crime and facilitate corruption and violence. Given that drug

markets cannot be eliminated, but may operate in ways that are more or less socially

harmful, the key questions for law enforcement become: what sort of markets do we least

dislike and how can we adjust the control mix so as to push markets in the least harmful

direction? In this chapter, we leave aside more detailed discussion of the wider impact of

drug law enforcement or criminalisation on societal levels of drug-related harm. We focus

instead on the provision of services that aim to reduce harms done to drug users within the

criminal justice system.

Many of the people who are caught up in the criminal justice system are highly exposed to

drug-related harms (EMCDDA, 2009a; Singleton et al., 1997; Stöver, 2001; Rotily et al.,

2001; Møller et al., 2007; Stöver et al., 2008a; Dolan et al., 2007). These people do not lose

their right to adequate and effective healthcare when they enter the criminal justice system

(Carter and Hall, 2010). The ideal criminal justice system would therefore protect their health

by offering the full range of healthcare approaches. Some European systems have been

moving closer, in various ways, to achieving this, and we describe some of these

developments in this chapter. We will examine how measures such as opioid substitution

treatment (OST), needle and syringe exchange, and the provision of disinfectants and

condoms have worked in prison contexts. We will look at issues of through-care and

aftercare and we will explore how processes that follow arrest can divert drug users into

treatment. Before looking at specific harm reduction measures we provide a short discussion

of the inherent tensions between controlling drugs through the criminal law and efforts to

reduce harms to drug users.

Tensions between law enforcement and harm reduction

There are at least two contradictions that hinder the effort to reduce harm through the

criminal justice system. The first is the fact that criminal justice systems themselves produce

harms. Of course, the criminal justice system also produces benefits to the extent that it

protects people from crime and insecurity. But arrests, fines, community penalties,

imprisonment and parole all infringe on individual freedoms and pleasures. The special pains

of imprisonment have been a particular focus of criminological research (Sykes 1958;

Mathiesen, 2006). The idea that these pains are justified by the need to reduce crime is

challenged by the lack of evidence for the effectiveness of imprisonment, the most painful

form of criminal justice intervention currently used in Europe (Tonry, 2004; Gendreau et al.,

1999). It is well known, for example, that there is little relationship between imprisonment and

crime rates (Kovandzic and Vieraitis, 2006; Reiner, 2000). Countries do not use prison as a

direct, rational measure to reduce crime. Rather, they choose — through a complex process

of ideological, moral, political and juridical negotiation — the level of pain that they are

willing to inflict on their citizens (Christie 1982). If we choose the level of harm that we inflict,

we can also choose to reduce it.

The second contradiction in pursuing harm reduction in the criminal justice system is that

between the pursuit of abstinence and the acknowledgement of continuing drug use.

Countries are obliged, through the UN drug conventions, to prohibit and to penalise the

possession of certain substances. The criminal justice system is the process that puts these

obligations into practice. It is very difficult for the same system to acknowledge that the

people under its control continue to defy the law. Until the mid-1990s, for example, it

was common for prison governors to deny that drug use was going on within their walls

(Duke, 2003). More recently, it has been suggested by Phillip Bean (2008) that treatment

agencies working with the criminal justice system should expect to subordinate their aims

to those of the criminal justice agencies. Harm reduction approaches have traditionally

been developed to meet the needs of people who continue to use illicit drugs, and

therefore do not fit with the prescription that people under penal control should abstain.

Some parts of the criminal justice system and some countries appear to negotiate this

conflict more easily than others. This may be due to the different perceptions of the ideal

goal of abstinence. Within the prison system, for example, abstinence has a relatively

high value, because it fits with the prison’s goal of incapacitating the prisoner from

committing further crimes (e.g. drug purchase and possession). Probation services, with a

greater focus on rehabilitation and relatively less control of the person’s behaviour, seem

to have less emphasis on absolute abstention, at least in Europe. In the United States,

drug use while on probation often leads to imprisonment. It is more often tolerated in

European probation systems, as long as no other offences are committed (Stevens,

forthcoming).

So how do we deal with these contradictions? First, it seems axiomatic that the best way to

reduce the amount of drug-related harm that occurs inside the criminal justice system is to

reduce the number of drug users who enter it. Drug users cannot cause harm (or be

harmed) in criminal justice settings if they are not actually in these settings. The number of

drug users in criminal justice settings can be reduced through decriminalisation of drugs,

which means that no drug users enter the criminal justice system for possession offences

(though decriminalisation of drugs would not necessarily reduce the number of drug users

who enter the system for other offences, which could be reduced by developing diversion

or alternative sanctions) (Stevens, forthcoming). Different European countries have tried

various forms of decriminalisation. They include the Netherlands’ expedient nonprosecution

of cannabis supply at the retail level, as well as the non-criminal offences of

personal drug use in the Czech Republic, Estonia, Italy, Spain and suspension of

prosecution of personal use offences in Germany and Austria.

The most comprehensive process of decriminalisation so far has occurred in Portugal.

From July 2001 people who are found by the Portuguese police to be in possession of

fewer than ten days’ personal supply of any drug have not been arrested, though the

drug is still confiscated. They have instead been referred to regional drug dissuasion

committees, which have the option of imposing warnings, fines, administrative sanctions

(such as taking away driving or firearms licences), or — in the case of dependent users

— referring them to treatment. Since decriminalisation, and the simultaneous expansion

of prevention, treatment and harm reduction services, there have been dramatic

reductions in drug-related deaths and HIV. Rates of drug use seem to have fallen among

children, but risen slightly in adults, in line with pan-European trends. The respective

roles of decriminalisation and the simultaneous expansion of drug treatment in producing

these changes can be debated (IDT, 2007; IDT, 2005; Hughes and Stevens, 2007;

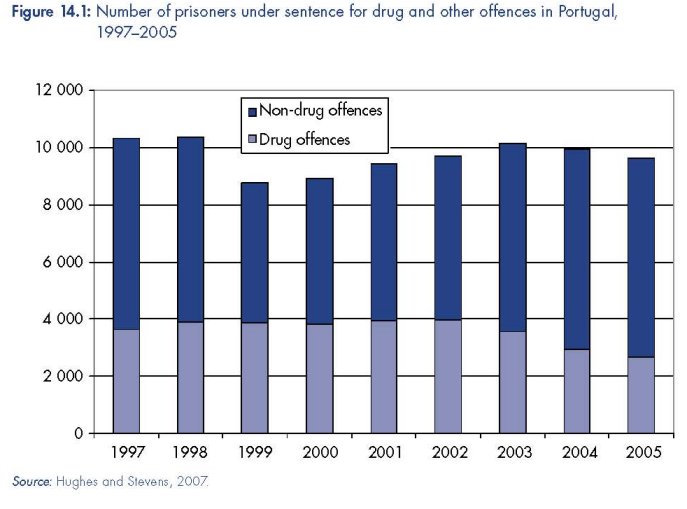

Greenwald, 2009). But Figure 14.1 shows clearly that decriminalisation reduced the use

of imprisonment for drug offences and led to an overall reduction in the prison

population (IDT, 2006, Table 62). This reduction has also been accompanied by

substantial reductions in the number of people using drugs and living with HIV within

Portuguese prisons (Torres et al., 2009).

The second contradiction is just a more extreme form of the long-standing argument that

harm reduction conflicts with the goal — still subscribed to by all UN members (ECOSOC,

2009) — of eliminating illicit drug use. Over time, there has been a gradual acceptance

that harm reduction measures do not prevent people from achieving abstinence, but

rather protect the health of people who will continue to use drugs, whether or not they

have the means to protect their health. This acceptance has been supported by decades

of evaluative research on harm reduction measures outside the criminal justice system,

including opiate substitution treatment (using methadone, buprenorphine or heroin itself)

and needle and syringe exchange programmes (Hunt, 2003; Ritter and Cameron, 2005;

Tilson et al., 2007; Kimber et al., 2010). As evidence develops on the use of such

measures within the criminal justice system, we could expect that resistance to harm

reduction within the criminal justice system will also subside. But we should not be too

optimistic. The negotiations at the high level segment of the Commission on Narcotic

Drugs in Vienna in March 2009 showed that resistance to harm reduction remains strong,

even outside the criminal justice system. A glimmer of hope from that meeting can be

perceived, if we look hard enough, in the commitment to provide treatment and ‘related

support services ... on a non-discriminatory basis, including in detention facilities’

(ECOSOC, 2009).

Harm reduction in the criminal justice system

Our exploration of existing harm reduction services in criminal justice systems starts in the

place where drug-related harms of the criminal justice system are most acute: prisons.

In a report on the implementation of the European Council Recommendation (of 18 June

2003 (1)) on the prevention and reduction of health-related harm associated with drug

dependence (2) it was stated that a policy to provide drug users in prisons with services

that are similar to those available to drug users outside prisons exists in 20 EU Member

States and was about to be introduced in four countries (van der Gouwe et al., 2006).

However, recent European monitoring data show that that the implementation of harm

reduction programmes is quite heterogeneous in European prisons (EMCDDA, 2009a).

Availability and accessibility of many key harm reduction measures in prisons lag far

behind the availability and accessibility of these interventions in the community outside

prisons (EMCDDA, 2009b).

(1) http://europa.eu.int/eur-lex/pri/en/oj/dat/2003/l_165/l_16520030703en00310033.pdf

Illustrating this gap most vividly is the provision — or lack thereof — of needle and syringe

programmes (NSP), currently only implemented in five EU countries (EMCDDA, 2009c). The

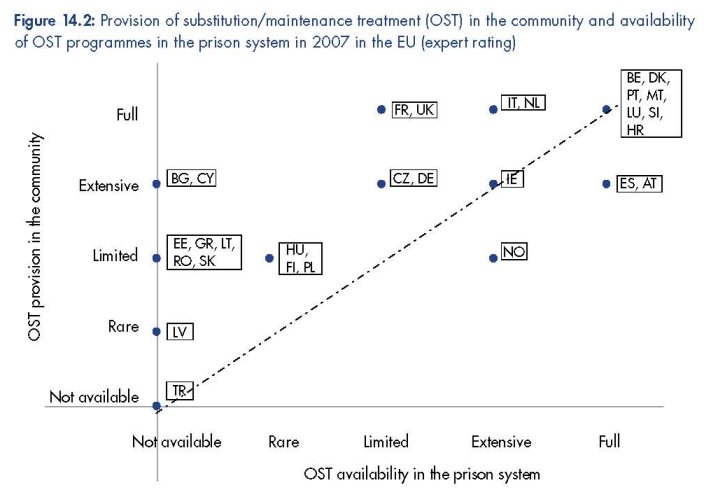

availability of opioid substitution treatment (OST) in prisons is low compared to the level of

OST provision in the community in most European countries (EMCDDA, 2009d; see Figure

14.2). These findings support an earlier statement from the European Commission that:

Harm reduction interventions in prisons within the European Union are still not in accordance with

the principle of equivalence adopted by UN General Assembly, UNAIDS/WHO and UNODC,

which calls for equivalence between health services and care (including harm reduction) inside

prison and those available to society outside prison. Therefore, it is important for the countries to

adapt prison-based harm reduction activities to meet the needs of drug users and staff in prisons

and improve access to services.

(European Commission, 2007, conclusion 5).

These findings also echo a 2008 WHO Regional Office for Europe report that monitored

State progress in achieving Dublin Declaration goals. The Dublin Declaration commits the

signatory States to take 33 specific actions — and in some cases meet specific targets — to

address the HIV prevention, care, treatment and support situation across the region. The

report found that, of the 53 signatory countries, condoms were available in prisons in only

18, syringe exchange programmes available in six and substitution treatment available in 17

(Matic et al., 2008). A more recent review (in 2009) by the International Harm Reduction

Association (IHRA) found the situation has only marginally improved, with nine countries (out

of 46) in Europe and Central Asia having syringe exchange in prisons and 28 substitution

treatment (Cook, 2009; see also Cook et al., 2010).

Calls for an urgent and comprehensive response to addressing health risks within prison

settings, including harm reduction measures (WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2005) are

not new, and have been highlighted in international reports and policy documents spanning

two decades (Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, 1988; UNODC et al., 2006;

WHO, 1993; Matic et al., 2008). However, despite existing recommendations, guidelines and

commitments made by governments and many others (Lines, 2008), only very few countries

within the European region have come close to achieving the goals set out (Cook, 2009).

There are four key harm reduction tools for the prison setting. We describe each of these,

including an example of best practice, below.

(2) http://ec.europa.eu/health/ph_determinants/life_style/drug/drug_rec_en.htm

Notes:

This figure is available at: http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/stats09/hsrfig2.

Comments:

Data were not available for Sweden.

Rating scales:

Prison: expert rating of the availability of OST programmes in prisons in the country (and does not reflect level of

OST provision in prison):

• Full: substitution/maintenance treatment exists in nearly all prisons.

• Extensive: exists in a majority of prisons but not in nearly all of them.

• Limited: exists in more than a few prisons but not in a majority of them.

• Rare: exists in just a few prisons.

Community: expert rating of the level of provision of OST in the community, in relation to the needs of target group

problem opioid users:

• Full: nearly all problem opioid users (POUs) in need would obtain OST.

• Extensive: a majority but not nearly all POUs in need would obtain OST.

• Limited: more than a few but not a majority of POUs in need would obtain OST.

• Rare: just a few POUs in need would obtain OST.

Sources: EMCDDA, 2009d. Structured questionnaire on ‘treatment programmes’ (SQ27/P1), submitted by NFPs in 2008.

Data for Malta is from DG Health and Consumer Protection, ‘Final report on prevention, treatment, and harm reduction

services in prison, on reintegration services on release from prison and methods to monitor/analyse drug use among

prisoners’, SANCO/2006/C4/02.

Needle and syringe exchange programmes in prisons

A position paper of the United Nations system identifies NSP as one component of ‘a

comprehensive package for HIV prevention among drug abusers’ (Commission on Narcotic

Drugs, 2002). In prisons, NSPs have been operating successfully for more than 15 years. A

meta-analysis (based on 11 evaluations of the implementation of prison-based NSPs)

revealed that none of the fears often associated with planned NSPs occurred in any project:

syringe distribution was followed neither by an increase in drug intake nor in administration

by injection. Syringes were not misused as weapons against staff or other prisoners, and

disposal of used syringes was uncomplicated. Sharing of syringes among drug users

disappeared almost completely or was apparent in very few cases. These studies

demonstrate both the feasibility, safety and efficacy of harm reduction including NSP in

prison settings (Meyenberg et al., 1999; Stöver and Nelles 2003).

At present, NSPs have been established in prisons in nine countries worldwide (Lines et al.,

2006), including six countries in Europe. Coverage of the national prison systems is, however,

variable. In Spain, implementation of needle and syringe exchange is authorised in all

prisons (see box below) and in 2006, programmes existed in 37 prisons (Acín García,

2008). In Switzerland, NSPs are available in eight of 120 prisons, and in Germany,

Luxembourg, Romania and Portugal such programmes operate in one or two prisons. Other

countries, including the United Kingdom (Scotland), are considering the implementation of

pilot projects (EMCDDA, 2009a; Lines et al., 2006). A review published in 2007 stated:

Prison NSPs have been implemented in both men’s and women’s prisons, in institutions of varying

sizes, in both civilian and military systems, in institutions that house prisoners in individual cells

and those that house them in barracks, in institutions with different security ratings, and in different

forms of custody (remand and sentenced, open and closed).

(Stöver et al., 2009, p. 83)

|

Prison-based needle and syringe exchange programmes in Spain Spanish prisons implement needle and syringe programmes (NSPs) via negotiated protocols • a Commission is created, with the Director and vice directors (including sanitary vice reducing potential harm to prison staff (Ministry of Labour and Social Security, 2002). |

Opioid substitution treatment

While opioid substitution treatment (OST) has become standard practice in community drug

treatment services in many European countries (EMCDDA, 2009a), the implementation of

OST in custodial settings in most European countries is still lagging behind the availability

and quality of the treatment provision in the community (Kastelic et al., 2008; EMCDDA,

2009d).

Studies have indicated that OST initiated in the community is most likely to be discontinued in

prisons (Stöver et al., 2004; Stöver et al., 2006; Michel, 2005; Michel and Maguet, 2003).

This often leads to relapse both inside prisons and immediately after release, often with

severe consequences, as indicated by high mortality rates after release from prisons

(Singelton et al., 2003). Many studies have also shown the benefits of OST for the health and

social stabilisation of opioid-dependent individuals passing through the prison system

(Stallwitz and Stöver 2007; Larney and Dolan, 2009).

Substitution treatment has been widely recognised as an effective treatment for opioid

dependence in the general community (Dolan et al., 1998; Farrell et al., 2001; Larney and

Dolan, 2009; UNODC et al., 2006) and as having crime reducing effects (Lind et al., 2005).

Despite this and the fact that methadone and buprenorphine have been added to the WHO

model list of essential medicines (WHO, 2005), it remains controversial for prisons,

particularly in Eastern European countries where substitution treatment also only exists on a

low level in the community (van der Gouwe et al., 2006). Nevertheless, experience has

clearly shown the benefits of this treatment in prisons (WHO et al., 2007; Heimer et al.,

2005; Stöver et al., 2008b; Stöver and Michels, 2010).

In countries that provide OST in prisons, it is most commonly used for short-term

detoxification, and less frequently as a maintenance treatment (Kastelic et al., 2008). In some

countries, such as Austria, England (see box on p. 387) and Spain, substitution treatment is

provided as standard therapy to many prisoners who began treatment in the community and

are deemed likely to continue it after release (Stöveret al., 2004). In others it is either not

available in prisons at all, although legally possible (Estonia and Lithuania), or only provided

in very rare cases (Sweden). OST treatment that has been started in the community cannot

legally be continued in prisons in Slovakia, Latvia, Cyprus and Greece. New substitution

treatments cannot be initiated in Slovakia, Latvia, Cyprus, Greece, Portugal, Finland and

Estonia (EMCDDA, 2009a).

Acknowledgement that the benefits of substitution treatment in the community might also

apply to the prison setting has taken years. The sources of the controversy — and the slow

and patchy manner of the intervention’s implementation thus far — can be traced first to the

prisons’ general failure to provide adequate healthcare, with limited resources for

populations with high concentrations of poor physical and mental health (Møller et al., 2007;

Bertrand and Niveau, 2006). Second, due to the parallel prison healthcare system (separate

to the national health services in most countries), responsibility for a prisoner’s medical

treatment is often transferred to healthcare providers only after that prisoner has been

released. Third, the ethos of coercion and incapacitation manifests itself in a strict abstinence

based approach to drug use. Therefore, while opioid-dependent individuals in the community

may be treated as patients and receive substitution treatment, in prison they continue to be

treated as prisoners who are supposed to remain drug free. This double standard leads to

frequent interruptions in treatment and inconsistency in dosages, especially as many opioid

users spend substantial periods of time incarcerated.

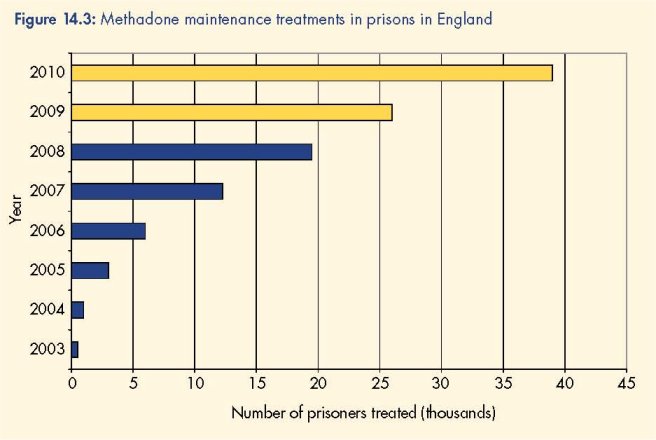

The number of methadone maintenance (OST) treatments started in prisons in England has increased from 700 in 2003 (1) to 19 450 for the year 2008. All 130 adult prisons in the country are now funded to provide OST. Approximately 26 000 treatments are anticipated for 2009, rising to 39 000 for the year 2010 (Marteau and Stöver, 2010).

The massive expansion of OST in prisons is the result of: a shift of responsibility for prison This example shows that the Integrated Drug Treatment System (IDTS) has been welcomed by (1) Refers to the fiscal year 2003–04 which runs from 1 March 2003 until end February 2004. All dates cited in this box |

Evidence shows that methadone maintenance treatment (MMT, the most studied form of

pharmacological drug treatment) can reduce risk behaviour in penal institutions, such as

reduced frequency of illicit drug use in prison and reduced involvement in the prison drug

trade (Dolan et al., 1998; Kimber et al., 2010). Studies have also demonstrated that

methadone maintenance treatment provision in a prison healthcare setting can be effective in

reducing heroin use, drug injection and syringe sharing among incarcerated heroin users

(Stöver and Marteau, 2010). A sufficiently high dosage also seems to be important for

improving retention rate, which helps in the provision of additional healthcare services (Dolan

et al., 2002).

There is evidence that continued MMT in prison has a beneficial impact on transferring

prisoners into drug treatment after release. The initiation of MMT in prisons also contributes to a

significant reduction in serious drug charges and in behaviour related to activities in the drug

subculture. Offenders participating in MMT also had lower readmission rates and were

readmitted at a slower rate than non-MMT patients. For example, a 2001 evaluative study of

the methadone programme of the Correctional Service of Canada (CSC) concluded that

participation in methadone programmes had positive post-release outcomes. The study found

that opiate users accessing MMT during their incarceration were less likely to be readmitted to

prison following their release — and were less likely to have committed new offences — than

were those not accessing methadone. These findings have been supported by a more recent

randomised trial from the United States. It showed that prisoners who started methadone

treatment before release and continued after it were significantly more likely to stay away from

illicit drugs in the first year after release. Their outcomes were better than those achieved by

similar prisoners who received only counselling in the prison, than if they were transferred to

methadone programmes on release (Kinlock et al. 2009; Stöver and Marteau 2010; Stöver and

Michels, 2010).

Studies have shown that prison staff tend to support the introduction of OST to a higher

degree than they support other harm reduction measures, such as syringe exchange (Allen,

2001). Greater knowledge of substitution programmes is directly associated with more

positive attitudes towards it (McMillan and Lapham, 2005). This suggests that training for

staff on all levels may decrease resistance to substitution programmes and contribute to

patient-oriented, confidential and ethical service delivery. Institutional constraints can also be

overcome by highlighting the benefits of a substitution programme for the prison itself (Stöver

and Marteau, 2010).

Provision of bleach and disinfectants

Many prison systems have adopted programmes that provide disinfectants such as bleach to

prisoners who inject drugs, as a means to clean injecting equipment before re-using it (see

box on p. 389). According to UNAIDS in 1997, the provision of full-strength bleach to

prisoners as a measure had been successfully adopted in prisons in Europe, Australia, Africa,

and Central America (UNAIDS, 1997). The WHO further reported that concerns that bleach

might be used as a weapon proved unfounded, and that this has not happened in any prison

where bleach distribution has been tried (WHO, 2007).

However, disinfection with bleach as a means of HIV prevention is of varying efficiency, and

therefore regarded only as a secondary strategy to syringe exchange programmes (WHO,

2005). The effectiveness of disinfection procedures is also largely dependent upon the

method used. Before 1993, guidelines for syringe cleaning stipulated a method known as the

‘2x2x2’ method. This method involved flushing injecting equipment twice with water, twice

with bleach and twice with water. Research in 1993 raised doubts about the effectiveness of

this method in the decontamination of used injecting equipment, and recommended new

cleaning guidelines where injecting equipment should be soaked in fresh full-strength bleach

(5 % sodium hypochlorite) for a minimum of 30 seconds (Shapshank et al., 1993).

All of these developments further complicate the effective use of bleach and disinfectants in

prison settings, where fear of detection by prison staff and lack of time often means that

hygienic preparation of equipment and drug use happens quickly, and that prisoners will

often not take the time to practise optimal disinfection techniques (WHO, 2005). Furthermore,

bleach is effective in killing the HIV virus, but may be less effective for the hepatitis C virus.

Training drug users to clean syringes with bleach may provide the user with false reassurance

regarding the risk of re-using injecting equipment. Despite these limitations, provision of

disinfectants to prisoners remains an important option to reduce the risk of HIV transmission,

particularly where access to sterile syringes is not available. The Royal College of General

Practitioners concluded that ‘[o]n current evidence it would be difficult to support a policy of

not distributing bleach’ (2007, p. 13).

By August 2001, bleach was provided in 11 of 23 pre-expansion EU prison systems (Stöver et al.,

2004). Disinfectants are also made available to prisoners in Canada, England and Wales, Iran,

Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Turkmenistan, Switzerland, and some parts of the Russian Federation.

|

Provision of bleach in Austrian prisons

|

Provision of condoms, dental dams, and water-based lubricants

Many prisons globally provide condoms to prisoners as part of their institutional health and

STI prevention policies. This is in keeping with the recommendation of the WHO Guidelines,

‘Since penetrative sexual intercourse occurs in prison, even when prohibited, condoms should

be made available to prisoners throughout their period of detention. They should also be

made available prior to any form of leave or release’ (WHO, 1993

Multiple barriers exist to the use of condoms in many prisons, and there is often poor

knowledge among prisoners of sexual risk behaviour and risk reduction (MacDonald, 2005;

Todts et al., 1997; UNODC et al., 2006). These barriers include prison rape, the social stigma

attached to homosexuality and same-sex activities, and insufficient privacy to enable safer

sex. Furthermore, condoms, dental dams, and water-based lubricants are often theoretically

available but often not easily and discreetly accessible, at least not available on a 24-hour

basis. Prisoners may be reluctant to access safer sex measures for fear of identifying

themselves as engaging in such activities.

Evidence suggests that the provision of condoms is feasible in a wide range of prison

settings (WHO et al., 2007). No prison system enabling condom distribution has reversed

this policy, and none have reported security problems or any major negative

consequences. Research also demonstrates the importance of identifying the factors

shaping resistance among stakeholders and prison officials to introducing harm reduction

measures in custodial settings, including condom distribution (Jürgens et al., 2009; Stöver

et al., 2007). The orientation of ministries of justice, public opinion, and prison system

financial constraints are all factors shaping staff acceptance or resistance to implementing

harm reduction, and it is important to develop tailor-made strategies to address these

(Marteau and Stöver 2010; Stöver et al., 2009).

Through-care and aftercare

Prison may be the place where drug-related harms are most visible and acute, but the vast

majority of prisoners will one day be released. According to Williamson (Williamson, 2006)

the major challenge for prison healthcare is:

to enable continuity of care, within, between, on admission and upon release. Using the prisoner

journey from pre-arrest to post release as a template it will be possible for local health and social

care, and criminal justice communities to better plan continuity of health and social care,

alternatives to imprisonment and long term support services.

(Williamson, 2006, p.5)

Several studies have shown that effective and rapid access to aftercare for drug-using

prisoners is essential to maintain gains made in prison-based treatment (e.g. Zurhold et al.,

2005; Inciardi et al., 1997; Department of Health/National Offender Management Service,

2009). Prisoners are marginalised in society and tend to fall into the gaps between care

systems and structures, which find it hard to deal with multiple needs. Care should be taken

to overcome this tendency. From previous studies on recidivism following in-prison

treatment (e.g. Inciardi et al., 1997), maintaining therapeutic relationships initiated in the

prison into the post-release period would be likely to reduce recidivism and improve health

outcomes. Prisons can be places of relative safety and health promotion for prisoners.

Many people slip back into less healthy habits when they leave this structured environment.

The box on p. 391 gives an example of a promising programme that seeks to avoid this

danger.

The ‘Through the Gates’ service

Many prisoners, including a high proportion of those with drug problems, leave prison with no

home to go to. This increases the likelihood that they will continue risky patterns of drug use and

offending. In response to this problem, the St Giles Trust (a non-governmental organisation

based in London) set up the ‘Through the Gates’ service. This service employs a team of

caseworkers (half of whom are themselves ex-offenders) to work with individual prisoners. The

caseworkers go to meet prisoners before they are released in order to assess their housing and

other needs. They then meet the prisoner at the gate of the prison on the day of their release.

The worker accompanies the client to initial meetings with the housing service, with probation

officers and, when necessary, drug treatment services. In the first year of this service, 70 % of

the homeless clients it worked with were successfully placed in temporary or permanent

accommodation. Probation officers reported that the service dramatically increased the chances

of successful resettlement. Some clients reported that it was the first time that they had been

helped to step off the repetitive treadmill of imprisonment, drug use and crime.

The following conclusions were drawn by a multi-country survey of key informants on

aftercare programmes for drug-using prisoners in several European countries (Fox, 2000):

• Aftercare for drug-using prisoners significantly decreases recidivism and relapse rates and

saves lives.

• Interagency cooperation is essential for effective aftercare. Prisons, probation services,

drug treatment agencies and health, employment and social welfare services must join up

to meet the varied needs of drug-using offenders.

• Short-sentence prisoners are the most poorly placed to receive aftercare and most likely to

re-offend. These prisoners need to be fast-tracked into release planning and encouraged

into treatment.

• Ex-prisoners need choice in aftercare. One size does not fit all in drug treatment.

• Aftercare that starts in the last phase of a sentence appears to increase motivation and uptake.

• In aftercare, housing and employment should be partnered with treatment programmes.

Unemployed and homeless ex-prisoners are most likely to relapse and re-offend.

• Drug treatment workers must have access to prisoners during their sentence to encourage

participation in treatment and to plan release.

As the mortality risks due to overdose are most critical in the first week after release

(Singleton et al., 2003; Farrell and Marsden, 2008), all harm reduction measures to prevent

overdose or drug-related infections should be available and accessible.

Earlier stages of the criminal justice system

As with prisons and through-care, the practice and policy of the police with regard to harm

reduction varies throughout Europe, dependent on different legal backgrounds. What can be

found all over Europe is a high level of formal or informal discretion (EMCDDA, 2002). The

police on the street can simply turn a blind eye towards illicit behaviour, or the official

strategy of the police might pro-actively support harm reduction. The basis for these choices

is a growing awareness of the adverse effects of control and custody with regard to the

health of drug users and thus an increasing acknowledgment of all forms of support,

assistance, counselling and treatment for this target group.

The introduction of policing practices that are more open to harm reduction interventions can

contribute substantially to reducing some of the negative consequences of police patrolling,

such as a reluctance to carry syringes and unsafe disposal, hurried and unsafe preparation

of injection, and the potential for police attention to deter drug users from going to treatment

centres (MacDonald et al., 2008). The availability of an injection location that is safe from

police interference is a significant harm reduction measure (Kerr et al., 2008). Drug

consumption rooms are an interesting model of accepting an unlawful behaviour (possession

and consumption of drugs) for the sake of the health of the drug users. In most countries

where they operate, these facilities are not only tolerated, but also demanded and supported

by the police, who also facilitate their use (DeBeck et al., 2008). Furthermore, the police

mostly see drug consumption rooms as a ‘win–win’ situation, as they spend less of their time

dealing with users, and therefore have more resources available to target dealers. In

addition, drug consumption is no longer taking place in the local area and causing public

nuisance, but is taking place under hygienic and less visible circumstances (Stöver, 2002;

Hedrich et al., 2010). The success of drug consumption rooms depends on the police

agreeing not to target drug users within and around them.

There are other examples in Europe of structured combinations of harm reduction and crime

prevention approaches. Arrest referral programmes, which first appeared in the United

Kingdom in the 1980s and were expanded at national level by the Home Office Circular in

1999, are an example of a criminal justice-based programme that can introduce drug users

to treatment and harm reduction services (Seeling et al., 2001). Arrest referral places

specially trained substance use assessment workers in police stations to counsel and refer

drug-using arrestees who voluntarily request assistance with their drug-related problems.

Arrest referral schemes provide an access point for new entrants to services. Data from the

national monitoring programme in England and Wales showed that half (51 %) of all those

screened by an arrest referral worker had never accessed specialist drug treatment services

(Sondhi et al., 2002). This implies that arrest referral is successful in contacting problem drugusing

offenders at an earlier point than they might have otherwise considered using services.

Outcomes of the arrest referral schemes included consistent reductions in drug use and

offending behaviour among problem drug-using offenders who have been engaged in the

scheme (Sondhi et al., 2002).

However, arrest referral often suffers from low rates of retention, with large proportions of the

contacted drug users not going on to contact services (Edmunds et al., 1998). In England and

Wales, the Drug Intervention Programme was supplemented by a system of case

management of drug-using offenders and, since 2005, testing on arrest and required

assessments in order to address this problem. These latter measures enable the police to

require a person arrested for any one of a specific list of offences to undergo a drug test. If

the test is positive for cocaine or heroin, the person can then be ordered to attend an

assessment with a drug treatment worker. The effect of these measures has not been

evaluated. They have brought more drug users into treatment assessments, but many of them

have been recreational users of cocaine who see no need to enter treatment.

At the stage of arrest, many drug users face risks associated with the seizure of their injecting

equipment, as this increases the risks of syringe sharing the next time they use drugs. The

provision of syringe exchange within police custody could reduce this risk. The revised 2007

ACPO Drug Strategy for Scotland, as well as reaffirming the support of police forces for

harm reduction interventions, also acknowledges the role of the introduction of syringe

exchange schemes in custody suites. As MacDonald et al. (2008) have stated:

Research has demonstrated that the police can have a role in harm reduction provision, without

necessarily compromising their legal and moral values. For example, they can encourage users

in detention to make use of local needle exchange sites and provide information on their location,

and they can use discretion in not arresting users at such sites, while consulting with the community

on the need for such methods.

(MacDonald et al., 2008, p. 6)

Early interventions have been implemented in many European states to avoid the negative

impact of both continuous untreated drug addiction and conviction and possibly

incarceration. ‘FreD goes net’ is a European network of such early intervention projects,

which are diverting young drug users from police to counselling agencies to avoid adverse

effects of the criminal justice system (LWL, 2009).

In a number of European countries legislation expands the options available to the courts for

the diversion of drug-related offenders away from the criminal justice system to treatment, or

for court-mandated treatment to form part of a sentence (EMCDDA, n.d.). Although data on

usage of these options remain rare (European Commission, 2008), it seems they have

historically been under-used (Turnbull and Webster, 1997). Few have been formally evaluated

(Hough et al., 2003). Those that have been evaluated have tended to show that treatment that

is entered through the legal system can be as effective as when people enter through other

modes (McSweeney et al., 2007; Stevens et al., 2005). The under-exploitation of opportunities

to divert drug users from the criminal justice system through alternative measures to

imprisonment remains a major problem — particularly in new Member States of the European

Union — which demands further investigation and action. In Cyprus in 2008, for example, a

law had existed since 1992 that enabled drug-using offenders to be diverted into treatment, but

no suitable treatments were in place and so the law was not used (Fotsiou, 2008).

Conclusion

The evidence and examples provided in this chapter have shown that it is possible to

negotiate the tensions between law enforcement and harm reduction. Services have been

successfully implemented that have reduced the harms experienced by drug users in the

criminal justice system. However, implementation in many countries remains at the level

of discussion, or small pilot projects. It is rare that countries actually practice the principle

of equivalence between services inside and outside prisons to which they have signed

up. And the chances of rapid extension of harm reduction in criminal justice systems may

seem to be low, given the current scale of economic uncertainty and strains on the public

purse.

Nevertheless, given the frequent contact between drug users and criminal justice systems,

and ongoing epidemics of blood-borne viruses linked to problem drug use, there is an urgent

need for harm reduction services to be scaled-up. Reducing the numbers of drug users in

prison will be the least costly means of increasing the proportion of prisoners who have

access to harm reduction. It would reduce demand for drug services in prison and would free

up resources to spend on harm reduction and other services, assuming that these resources

are not diverted away from working with drug users.

Additional challenges remain. These include the need to develop and expand services for

non-opiate users (such as methamphetamine users in parts of Eastern Europe, and cocaine/

crack users in the United Kingdom; see Decorte, 2008; Hartnoll et al., 2010), as well as the

challenge of involving drug users themselves in the design and delivery of harm reduction

services (see Hunt et al., 2010), which are especially severe when those drug users are

subject to the criminal justice system.

All elements of the criminal justice system have roles to play in the reduction of drug-related

harm, including police officers, prosecutors, courts, prisons, probation services and nongovernmental

organisations that work with offenders. Harm reduction is a challenge for law

enforcement, and law enforcement is a challenge for harm reduction. The contradictions

between the aims of these two approaches cannot be wished away. However, we can protect

both public health and individual rights to healthcare by acknowledging these tensions and

finding ways to move beyond them to provide high-quality harm reduction services to all

who need them.

Acknowledgements

The authors’ gratitude goes to the various reviewers of this chapter who helped us to improve

it and to the EMCDDA for providing useful information.

References

Acín García, E. J. (2008), ‘Un enfoque global sobre la prevención y el control del VIH en las prisiones de España’,

Secretaría General de instituciones Penitenciarias, Ministerio del Interior, Gobierno de España, presentation at

the Internacional Harm Reduction Conference, Bangkok 2008.

Allen, A-M. (2001), Drug-related knowledge and attitudes of prison officers in Dublin prisons, Thesis submitted for

the degree of M.Sc. in Community Health, Department of Community Health and General Practice, Trinity

College, Dublin, October.

Allwright, S., Bradley, F., Long, J., et al. (2000), ‘Prevalence of antibodies to hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HIV and

risk factors in Irish prisoners: results of a national cross sectional survey’, British Medical Journal 321 (7253), pp.

78–82.

Bean, P. (2008), Drugs and crime, 3rd edition, Willan Publishing, Cullompton.

Bertrand, D. and Niveau, G. (eds) (2006), Médecine, santé et prison, Editions Medecine & Hygiene, Chene-Bourg.

Bravo, M. J., de la Fuente, L., Pulido, J., et al. (2009), ‘Spanish HIV/AIDS epidemic among IDUs and the policy

response from an historical perspective’, Presentation at the 5th European Conference on Clinical and Social

Research on AIDS and Drugs, Vilnius, 28–30 April 2009.

Carter, A. and Hall, W. (2010, in press), ‘The rights of individuals treated for drug, alcohol and tobacco

addiction’, in Dudley, M., Silove, D. and Gale, F. (eds) (2010), Mental health and human rights, Oxford University

Press, Oxford.

Caulkins, J. P. and Reuter, P. (2009), ‘Towards a harm-reduction approach to enforcement’, Safer Communities 8

(1), pp. 9–23.

Christie, N. (1982), Limits to pain, Martin Robertson, Oxford.

Cook, C. (2009), Harm reduction policy and practice worldwide: an overview of national support for harm reduction

in policy and practice, International Harm Reduction Association, Victoria and London. Available at http://www.

ihra.net/HRWorldwide.

Cook, C., Bridge, J. and Stimson, G. V. (2010), ‘The diffusion of harm reduction in Europe and beyond’, in

European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA), Harm reduction: evidence, impacts and

challenges, Rhodes, T. and Hedrich, D. (eds), Scientific Monograph Series No. 10, Publications Office of the

European Union, Luxembourg.

Commission on Narcotic Drugs (2002), Preventing the transmission of HIV among drug abusers: a position paper of

the United Nations system, endorsed on behalf of ACC by the High-Level Committee on Programme (HLCP) at its first

regular session of 2001, Vienna, 26–27 February 2001, document E/CN.7/2002/CRP.5 for participants at the

Forty-fifth session, Vienna, 11–15 March 2002. Available at http://www.cicad.oas.org/en/Resources/

UNHIVaids.pdf.

Crawley, D. (2007), Good practice in prison health, Department of Health, London.

DeBeck, K., Wood, E., Zhang, R., et al. (2008), ‘Police and public health partnerships: evidence from the

evaluation of Vancouver’s supervised injection facility’, Substance Abuse Treatment Prevention Policy May, 7 (3),

p. 11. DOI: 10.1186/1747-597X-3-11.

Decorte, T. (2008), ‘Problems, needs and service provision related to stimulant use in European prisons’,

International Journal of Prisoner Health 3 (1), pp. 29–42. Available at http://dx.doi.

org/10.1080/17449200601149122.

Department of Health/National Offender Management Service (2009), Guidance notes: prison health

performance and quality indicators, Department of Health, London. Available at http://www.hpa.nhs.uk/web/

HPAwebFile/HPAweb_C/1232006593707.

Dolan, K. and Wodak, A. (1999), ‘HIV transmission in a prison system in an Australian State’, Medical Journal of

Australia 171 (1), pp. 14–17.

Dolan, K. A., Wodak, A. D. and Hall, W. D. (1998), ‘Methadone maintenance treatment reduces heroin injection

in New South Wales prisons’, Drug and Alcohol Review June, 17 (2), pp. 153–8.

Dolan, K., Shearer, J., White, B. and Wodak, A. (2002), A randomised controlled trial of methadone maintenance

treatment in NSW prisons, National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, Sydney.

Dolan, K., Khoei, E. M., Brentari, C. and Stevens, A. (2007) Prisons and drugs: a global review of incarceration,

drug use and drug services. Report 12. Discussion paper, The Beckley Foundation, Oxford. Available at http://kar.

kent.ac.uk/13324/.

Dorn, N. and South, N. (1990), ‘Drug markets and law enforcement’, British Journal of Criminology 30 (2), pp.

171–88.

Dublin Declaration on HIV/AIDS in Prisons in Europe and Central Asia (2004), Prison health is public health, Irish

Penal Reform Trust, Dublin.

Duke, K. (2003), Drugs, prisons and policy-making, Palgrave, Basingstoke.

ECOSOC (United Nations Economic and Social Council) (2009), Political declaration and plan of action on

international cooperation towards an integrated and balanced strategy to counter the world drug problem, United

Nations, Vienna.

Edmunds, M., May, T., Hearnden, I. and Hough, M. (1998), Arrest referral: emerging lessons from research, Home

Office, London.

EMCDDA (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction) (n.d.), Treatment as an alternative to

prosecution or imprisonment for adults, ELDD Topic overview, European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug

Addiction, Lisbon. Available at http://eldd.emcdda.europa.eu/html.cfm/index13223EN.html (accessed 3

December 2009).

EMCDDA (2002), Prosecution of drug users in Europe: varying pathways to similar objectives, Insights series number

5, European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, Lisbon. Available at http://www.emcdda.europa.

eu/html.cfm/index33988EN.html.

EMCDDA (2005), Alternatives to imprisonment: targeting offending problem drug users in the EU, Selected issue,

European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, Lisbon. Available at http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/

html.cfm/index34889EN.html.

EMCDDA (2009a), Annual report 2009: the state of the drugs problem in Europe, European Monitoring Centre for

Drugs and Drug Addiction, Lisbon. Available at http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/annualreport/

2009.

EMCDDA (2009b), Statistical bulletin 2009, Table HSR-7: availability and level of provision of selected health

responses to prisoners in 26 EU countries, Norway and Turkey (expert ratings), European Monitoring Centre for

Drugs and Drug Addiction, Lisbon. Available at http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/stats09/hsrtab7.

EMCDDA (2009c), Statistical bulletin 2009, Table HSR-4: year of introduction of needle and syringe programmes

and types of programmes (NSP) available in 2007, European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction,

Lisbon. Available at http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/stats09/hsrtab4.

EMCDDA (2009d), Statistical bulletin 2009, Figure HSR-2: provision of substitution/maintenance treatment (OST)

in the community and availability of OST programmes in the prison system in 2007 (expert rating), European

Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, Lisbon. Available at http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/stats09/

hsrfig2.

European Commission (2007), ‘Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council on the

implementation of the Council Recommendation of 18 June 2003 on the prevention and reduction of healthrelated

harm associated with drug dependence’, COM (2007) 199 final. Available at http://eur-lex.europa.eu/

LexUriServ/site/en/com/2007/com2007_0199en01.pdf.

European Commission (2008), Commission staff working document: accompanying document to the communication

from the Commission to the Council and the European Parliament on an EU drugs action plan 2009–2012. Report of

the final evaluation of the EU drugs action plan (2005–2008), COM(2008) 567, SEC(2008) 2455, SEC(2008)

2454, European Community, Brussels. Available at http://eur-lex.europa.eu/SECMonth.

do?year=2008&month=09.

Farrell, M. and Marsden, J. (2008), ‘Acute risk of drug-related death among newly released prisoners in England

and Wales’, Addiction February 103 (2), pp. 251–5.

Farrell, M., Gowing, L. R., Marsden, J. and Ali, R. L. (2001), ‘Substitution treatment for opioid dependence: a

review of the evidence and the impact’, in Council of Europe (ed.), Development and improvement of substitution

programmes: proceedings of a seminar organized by the Cooperation Group to combat Drug Abuse and Illicit

Trafficking in Drugs (Pompidou Group), Strasbourg, France, 8–9 October 2001, pp. 27–54.

Fazel, S., Bains, P. and Doll, H. (2006), ‘Substance abuse and dependence in prisoners:

a systematic review’, Addiction 101 (2), pp. 181–91.

Fotsiou, N. (2008), Personal communication, Cyprus Anti-Drugs Council, Nicosia.

Fox, A. (2000), Prisoners’ aftercare in Europe: a four countries study, European Network of Drug and HIV/AIDS

Services in Prison (ENDHASP), Cranstoun Drug Services, London.

Gendreau, P., Goggin, C. and Cullen, F. T. (1999), The effects of prison sentences on recidivism, Solicitor General

Canada, Public Works and Government Services Canada, Ottawa. Available at http://www.prisonpolicy.org/

scans/gendreau.pdf.

Greenwald, G. (2009), Drug decriminalization in Portugal: lessons for creating fair and successful drug policies,

Cato Institute, Washington, DC. Available at http://www.cato.org/pub_display.php?pub_id=10080.

Hagan, H. (2003), ‘The relevance of attributable risk measures to HIV prevention planning’, AIDS 17, pp. 911–13.

Hartnoll, R., Gyarmarthy, A. and Zabransky, T. (2010), ‘Variations in problem drug use patterns and their

implications for harm reduction’, in European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA), Harm

reduction: evidence, impacts and challenges, Rhodes, T. and Hedrich, D. (eds), Scientific Monograph Series No.

10, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

Hassim, A. (2006), ‘The “5 star” prison hotel: the right of access to ARV treatment for HIV positive prisoners in

South Africa’, International Journal of Prisoner Health 2 (3), pp. 157–72.

Hedrich, D. (2004), European report on drug consumption rooms, European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug

Addiction, Lisbon. Available at http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/html.cfm/index54125EN.html.

Hedrich, D., Kerr, T. and Dubois-Arber, F. (2010), ‘Drug consumption facilities in Europe and beyond’, in

European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA), Harm reduction: evidence, impacts and

challenges, Rhodes, T. and Hedrich, D. (eds), Scientific Monograph Series No. 10, Publications Office of the

European Union, Luxembourg.

Heimer, R., Catania, H., Zambrano, J. A., et al. (2005), ‘Methadone maintenance in a men’s prison in Puerto

Rico: a pilot program’, Journal of Correctional Health Care, The Official Journal of the National Commission on

Correctional Health Care 11 (3), pp. 295–306.

Hough, M., Clancy, A., McSweeney, T. and Turnbull, P. J. (2003), ‘The impact of drug treatment and testing

orders on offending: two year reconviction results’, Home Office Research Findings No. 184, Home Office,

London.

Hughes, C. and Stevens, A. (2007), The effects of the decriminalization of drug use in Portugal, Beckley

Foundation, Oxford. Available at http://www.idpc.net/php-bin/documents/BFDPP_BP_14_

EffectsOfDecriminalisation_EN.pdf.pdf.

Hunt, N. (2003), A review of the evidence-base for harm reduction approaches to drug use, Forward Thinking on

Drugs, London. Available at http://www.iprt.ie/contents/1328.

Hunt, N., Albert, E. and Montañés Sánchez, V. (2010), ‘User involvement and user organising in harm reduction’,

in European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA), Harm reduction: evidence, impacts and

challenges, Rhodes, T. and Hedrich, D. (eds), Scientific Monograph Series No. 10, Publications Office of the

European Union, Luxembourg.

IDT (Instituto da Droga e da Toxicodependência) (2005), Relatório anual 2004 — A situação do país em matéria

de drogas e toxicodependências. Volume I - Informação estatística, Instituto da Droga e da Toxicodependência,

Lisbon. Available at http://www.idt.pt.

IDT (2006), Relatório anual 2005 — A situação do país em matéria de drogas e toxicodependências. Volume I -

Informação estatística, Instituto da Droga e da Toxicodependência, Lisbon. Available at http://www.idt.pt.

IDT (2007), Portugal: new developments, trends and in-depth information on selected issues: 2006 National report

(2005 data) to the EMCDDA by the Reitox National Focal Point, Instituto da Droga e da Toxicodependência, Lisbon.

Available at http://www.idt.pt.

Inciardi, J. A., Martin, S. S., Butzin, C. A., Hooper, R. M. and Harrison, L. D. (1997), ‘An effective model of

prison-based treatment for drug-involved offenders’, Journal of Drug Issues, 27 (2), pp. 261–78.

Jürgens, R., Ball, A. and Verster, A. (2009), ‘Interventions to reduce HIV transmission related to injecting drug use

in prison’, Lancet Infectious Diseases 9, pp. 57–66.

Kastelic, A., Pont, J. and Stöver, H. (2008), Opioid substitution treatment in custodial settings: a practical guide,

BIS-Verlag, Oldenburg. Available at http://www.unodc.org/documents/baltics/OST%20in%20Custodial%20

Settings.pdf.

Keppler, K., Nolte, F. and Stöver, H. (1996), ‘Übertragungen von Infektionskrankheiten im Strafvollzug —

Ergebnisse einer Untersuchung in der JVA für Frauen in Vechta [Transmission of infectious diseases in prison:

results of a study in the prison for women in Vechta]’, Sucht 42 (2), pp. 98–107. Available at http://www.neuland.

com/index.php?s=sxt&s2=inh&s3=1996204.

Kerr, T., Macpherson, D. and Wood, E. (2008), ‘Establishing North America’s first safer injection facility: lessons

from the Vancouver experience’, in Stevens, A. (ed.), Crossing frontiers: international developments in the treatment

of drug dependence, Pavilion Publishing, Brighton, pp. 109–29.

Kimber, J., Palmateer, N., Hutchinson, S., et al. (2010), ‘Harm reduction among injecting drug users: evidence of

effectiveness’, in European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA), Harm reduction:

evidence, impacts and challenges, Rhodes, T. and Hedrich, D. (eds), Scientific Monograph Series No. 10,

Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

Kinlock, T. W., Gordon, M. S., Schwartz, R. P., Fitzgerald, T. T. and O’Grady, K. E. (2009), ‘A randomized

clinical trial of methadone maintenance for prisoners: results at 12 months postrelease’, Journal of Substance

Abuse Treatment 37, pp. 277–85

Kovandzic, T. V. and Vieraitis, L. M. (2006), ‘The effect of county-level prison population growth on crime rates’,

Criminology and Public Policy 5 (2), pp. 213–44.

Larney, S. and Dolan, K. (2009), ‘A literature review of international implementation of opioid substitution

treatment in prisons: equivalence of care?’, European Addiction Research 15, pp. 107–12.

Lind, B., Chen, S., Weatherburn, D. and Mattick, R. (2005), ‘The effectiveness of methadone maintenance

treatment in controlling crime: an Australian aggregate-level analysis’, British Journal of Criminology 45 (2), pp.

201–11.

Lines, R. (2008), ‘The right to health of prisoners in international human rights law’, International Journal of

Prisoner Health 4 (1), pp. 3–53.

Lines, R., Jürgens, R., Betteridge, G., et al. (2006), Prison needle exchange: lessons from a comprehensive review of

international evidence and experience, 2nd edition, Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network, Toronto. Available at

http://www.aidslaw.ca/publications/publicationsdocEN.php?ref=184.

LWL (Landschaftsverband Westfalen-Lippe) (2009), Fred goes net: Early intervention for young drug users,

Landschaftsverband Westfalen-Lippe, Münster. Available at http://www.lwl.org/LWL/Jugend/lwl_ks/Projekte_

KS1/Fgn-english/.

MacCoun, R. J. and Reuter, P. (2001), Drug war heresies: learning from other vices, times, and places, Cambridge

University Press, Cambridge.

MacDonald, M. (2005), A study of health care provision, existing drug services and strategies operating in prisons in

ten countries from central and eastern Europe, Heuni, Helsinki. Available at http://www.heuni.fi/12542.htm.

MacDonald, M., Atherton, S., Berto, D., et al. (2008), Service provision for detainees with problematic drug and

alcohol use in police detention: a comparative study of selected countries in the European Union, Paper No. 27,

European Institute for Crime Prevention and Control, affiliated with the United Nations (HEUNI), Helsinki.

McMillan, G. P. and Lapham, S. C. (2005), ‘Staff perspectives on methadone maintenance therapy (MMT) in a

large southwestern jail’, Addiction Research and Theory 13 (1), pp. 53–63.

McSweeney, T., Stevens, A., Hunt, N. and Turnbull, P. (2007), ‘Twisting arms or a helping hand? Assessing the

impact of “coerced” and comparable “voluntary” drug treatment options’, British Journal of Criminology 47 (3),

pp. 470–90.

Marteau, D. and Stöver, H. (2010, in press), ‘The introduction of the prisons “Integrated Drug Treatment System

(IDTS)” in England’, International Journal of Prisoner Health.

Mathiesen, T. (2006), Prison on trial, 3rd edition, Waterside Press, Winchester.

Matic, S., Lazarus, J. V., Nielsen, S. and Laukamm-Josten, U. (eds) (2008), Progress on implementing the Dublin

Declaration on Partnership to Fight HIV/AIDS in Europe and Central Asia, WHO Regional Office for Europe,

Copenhagen. Available at http://www.euro.who.int/document/e92606.pdf.

Meyenberg, R., Stöver, H., Jacob, J. and Pospeschill, M. (1999), Infektionsprophylaxe im Niedersächsischen

Justizvollzug — Abschlußbericht, BIS-Verlag, Oldenburg.

Michel, L. (2005), ‘Substitutive treatments for major opionic dependance adapted to prison life’, Information

Psychiatrique 81 (5), pp. 417–22.

Michel, L. and Maguet, O. (2003), L’organisation des soins en matière de traitements de substitution en milieu

carcéral, Rapport pour la Commisssion nationale consultative des traitements de substitution, Centre Régional

d’Information et de Prévention du Sida Ile-de-France, Paris.

Michel, L., Carrieri, P. and Wodak, A. (2008), ‘Harm reduction and equity of access to care for French prisoners:

a review’, Harm Reduction Journal 5, p. 17. DOI: 10.1186/1477-7517-5-17.

Ministry of Labour and Social Security (2002), Instruction 101/2002 of the Directorate General on Labour Inspection

and Social Security on criteria of action in connection with the implementation in a number of prisons of the needle

exchange program for injecting drug users, 23. August 2002, Ministry of Labour and Social Security, Madrid.

Møller, L, Stöver, H., Jürgens, R., Gatherer, A. and Nikogosian, H. (eds) (2007), Health in prisons: a WHO guide

to the essentials in prison health, WHO Regional Office for Europe, Copenhagen.

Offender Health Research Network (2009), Website. Available at http://www.ohrn.nhs.uk (accessed 19 August

2009).

Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (1988), Recommendation 1080 on a co-ordinated European

health policy to prevent the spread of AIDS in prison, Council of Europe, Strasbourg. Available at http://assembly.

coe.int/documents/AdoptedText/ta88/erec1080.htm.

Pont, J. (2008), ‘Ethics in research involving prisoners’, International Journal of Prisoner Health 4 (4), pp. 184–97.

Radcliffe, P. and Stevens, A. (2008), ‘Are drug treatment services only for “thieving junkie scumbags”? Drug users

and the management of stigmatised identities’, Social Science and Medicine 67 (7), pp. 1065–73.

Reiner, R. (2000), ‘Crime and control in Britain’, Sociology: The Journal of the British Sociological Association, 34

(1), pp. 71–94.

Ritter, A. and Cameron, J. (2005), Monograph no. 06: a systematic review of harm reduction, DPMP Monograph

Series, Turning Point Alcohol and Drug Centre. Fitzroy.

Rolles, S. and Kushlick, D. (2004), After the war on drugs, Transform, Bristol.

Rotily, M., Weilandt, C., Bird, S. M., et al. (2001), ‘Surveillance of HIV infection and related risk behaviour in

European prisons: A multicentre pilot study’, European Journal of Public Health 11 (3), 243–50.

Royal College of General Practitioners (2007), Guidance for the prevention, testing, treatment and management of

hepatitis C in primary care, Royal College of General Practitioners, London. Available at http://www.smmgp.org.

uk/download/guidance/guidance003.pdf.

Seeling, C., King, C., Metcalfe, E., Tober, G. and Bates, S. (2001), ‘Arrest referral: a proactive multi-agency

approach’, Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy 8, pp. 327–33.

Shapshank, P., McCoy, C., Rivers, J. , et al. (1993), ‘Inactivation of Human Immunodeficiency Virus-1 at short time

intervals using undiluted bleach’, Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 6, pp. 218–19.

Singleton, N., Meltzer, H. and Gatward, R. (1997), Psychiatric morbidity among prisoners: summary report,

National Statistics, London. Available at http://www.statistics.gov.uk/downloads/theme_health/Prisoners_

PsycMorb.pdf.

Singleton, N., Pendry, E., Taylor, C., Farrell, M. and Marsden, J. (2003), ‘Drug-related mortality among newly

released offenders’, Findings 187, Home Office, London. Available at http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/pdfs2/

r187.pdf.

Sondhi, A., O’Shea, J. and Williams, T. (2002), ‘Arrest referral: emerging findings from the national monitoring

and evaluation programme’, DPAS Briefing Paper 18, Home Office Drug Prevention Advisory Service, London.

Stallwitz, A. and Stöver, H. (2007), ‘The impact of substitution treatment in prisons: a literature review’,

International Journal of Drug Policy 18, pp. 464–74.

Stevens, A. (2008), ‘Alternatives to what? Drug treatment alternatives as a response to prison expansion and

overcrowding’, Presentation at the 2nd Annual Conference of the International Society for the Study of Drug

Policy, 3–4 April 2008, Lisbon.

Stevens, A. (forthcoming), ‘Treatment sentences for drug users: contexts, mechanisms and outcomes’, in

Hucklesby, A. and Wincup, E. (eds), Drug interventions and criminal justice, Milton Keynes.

Stevens, A., Berto, D., Heckmann, W., et al. (2005), ‘Quasi-compulsory treatment of drug dependent offenders:

an international literature review’, Substance Use and Misuse 40, pp. 269–83.

Stevens, A., Bewley-Taylor, D. and Dreyfus, P. (2009), Drug markets and urban violence: can tackling one reduce

the other?, Beckley Foundation, Oxford.

Stöver, H. (1994), ‘Infektionsprophylaxe im Strafvollzug’, in Stöver, H. (ed.), Infektionsprophylaxe im Strafvollzug.

Eine Übersicht über Theorie und Praxis (Vol. XIV), Deutsche AIDS-Hilfe, Berlin, pp. 13–40.

Stöver, H. (2001), An overview study: assistance to drug users in European Union prisons, EMCDDA, Lisbon.

Stöver, H. (2002), ‘Consumption rooms: a middle ground between health and public order concern’, Journal of

Drug Issues 32 (2), pp. 597–606.

Stöver, H. (ed.) (2008), Evaluation of national responses to HIV/AIDS in prison settings in Estonia: evaluation carried

out on behalf of the UNODC Regional project ‘HIV/AIDS prevention and care among injecting drug users and in

prison settings in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania’, UNODC, New York. Available at http://www.unodc.org/

documents/baltics/Report_Evaluation_Prisons_2008_Estonia.pdf.

Stöver, H. and Marteau, D. (2010, in press), ‘Scaling-up of opioid substitution treatment in custodial settings:

evidence and experiences’, International Journal of Prisoner Health.

Stöver, H. and Michels, I. I. (2010, in press), ‘Drug use and opioid substitution treatment for prisoners’, Addiction.

Stöver, H., and Nelles, J. (2003), ‘10 years of experience with needle and syringe exchange programmes in

European prisons: a review of different evaluation studies’, International Journal of Drug Policy, 14 (5–6), 437–44.

Stöver, H., Hennebel, L. and Casselman, J. (2004), Substitution treatment in European prisons: a study of policies

and practices of substitution treatment in prisons in 18 European countries, Cranstoun Drug Services, London.

Stöver, H., Casselman, J. and Hennebel, L. (2006), ‘Substitution treatment in European prisons: a study of policies

and practices in 18 European countries’, International Journal of Prisoner Health 2 (1), pp. 3–12.

Stöver, H., MacDonald, M. and Atherton, S. (2007), Harm reduction for drug users in European prisons, BISVerlag,

Oldenburg.

Stöver, H., Weilandt, C., Zurhold, H., Hartwig, C. and Thane, K. (2008a), Final report on prevention, treatment,

and harm reduction services in prison, on reintegration services on release from prison and methods to monitor/

analyse drug use among prisoners (Drug policy and harm reduction, SANCO/2006/C4/02), European Commission,

Directorate – General for Health and Consumers. Available at http://ec.europa.eu/health/ph_determinants/

life_style/drug/documents/drug_frep1.pdf .

Stöver, H., Weilandt, C., Huisman, A., et al. (2008b), Reduction of drug-related crime in prison: the impact of

opioid substitution treatment on the manageability of opioid dependent prisoners, BISDRO, University of Bremen,

Bremen.

Stöver, H., Lines, R. and Thane, K. (2009), ‘Harm reduction in European prisons: looking for champions and ways

to put evidence-based approaches into practice’, in Demetrovics, Z., Fountain, J. and Kraus, L. (eds), Old and new

policies, theories, research methods and drug users across Europe, European Society for Social Drug Research

(ESSD), pp. 34–49. Available at http://www.essd-research.eu/en/publications.html.

Sykes, G. M. (1958), The society of captives, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

Taylor, A., Goldberg, D., Emslie, J., et al. (1995), ‘Outbreak of HIV infection in a Scottish prison’, British Medical

Journal 310 (6975), pp. 289–92.

Tilson, H., Aramrattana, A., Bozzette, S., et al. (2007), Preventing HIV infection among injecting drug users in high

risk countries: an assessment of the evidence, Institute of Medicine, Washington, DC. Available at http://www.nap.

edu/catalog.php?record_id=11731.

Todts, S., Fonck, R., Colebunders, R., et al. (1997), ‘Tuberculosis, HIV hepatitis B and risk behaviour in a Belgian

prison’, Archives of Public Health 55, pp. 87–97.

Tonry, M. (2004), Punishment and politics: evidence and emulation in the making of English crime control policy,

Willan Publishing, Cullompton.

Torres, A. C., Maciel, D., Sousa, D. and Cruz, R. (2009), Drogas e Prisões — Portugal 2007, CIES/ISCTE, Lisbon.

Turnbull, P. J. and Webster, R. (1997), Demand reduction activities in the criminal justice system in the European

Union, Final Report, EMCDDA, Lisbon.

UNAIDS (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS) (1997), Prisons and AIDS: UNAIDS technical update,

UNAIDS Best Practice Collection, United Nations, Geneva.

UNODC (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime) and UNAIDS (2008), Women and HIV in prison settings,

United Nations, Geneva/Vienna.

UNODC, WHO and UNAIDS (2006), HIV/AIDS prevention, care, treatment and support in prison settings: a

framework for an effective national response, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, World Health

Organization and the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, Vienna and New York.

van der Gouwe, D., Gallà, M., van Gageldonk, A., et al. (2006), Prevention and reduction of health-related harm

associated with drug dependence: an inventory of policies, evidence and practices in the EU relevant to the implementation

of the Council Recommendation of 18 June 2003. Synthesis report, Contract nr. SI2.397049, Trimbos Instituut, Utrecht.

Available at http://ec.europa.eu/health/ph_determinants/life_style/drug/documents/drug_report_en.pdf.

WHO (World Health Organization) (1993), WHO guidelines on HIV infection and AIDS in prisons, WHO, Geneva.

WHO (2005), Effectiveness of drug dependence treatment in preventing HIV among injecting drug users, Evidence

for action technical papers, WHO, Geneva.

WHO (2007), Effectiveness of interventions to manage HIV in prisons: needle and syringe programmes and bleach

and decontamination strategies, Evidence for action technical papers, WHO, Geneva.

WHO (2005), WHO model list of essential medicines, 14th revision (March 2005), WHO, Geneva. Available at

http://www.who.int/medicines/publications/essentialmedicines/en/index.html.

WHO Regional Office for Europe (2005), Status paper on prisons, drugs and harm reduction, WHO Office for

Europe, Copenhagen.

WHO Regional Office for Europe (2007), ‘WHO health in prisons project’, Newsletter December, WHO Office for

Europe, Copenhagen. Available at http://www.euro.who.int/Document/HIPP/WHO_HIPP-Newsletter-dec07.pdf.

WHO, UNAIDS and UNODC (2007), Effectiveness of interventions to manage HIV in prisons: provision of condoms

and other measures to decrease sexual transmission, Evidence for action technical papers, World Health

Organization, Geneva.

Williamson, M. (2006), Improving the health and social outcomes of people recently released from prisons in the UK:

a perspective from primary care, The Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health, London. Available at http://www.scmh.

org.uk/pdfs/scmh_health_care_after_prison.pdf.

Zurhold, H., Haasen, C. and Stöver, H. (2005), Female drug users in European prisons: a European study of prison

policies, prison drug services and the women’s perspectives, BIS-Verlag, Oldenburg.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|