Chapter 13 Young people, recreational drug use and harm reduction

| Reports - EMCDDA Harm Reduction |

Drug Abuse

Chapter 13 Young people, recreational drug use and harm reduction

Adam Fletcher, Amador Calafat, Alessandro Pirona and Deborah Olszewski

Abstract

This chapter begins by reviewing the prevalence of recreational drug use and related

adverse health outcomes among young people in European countries. It then employs a

typological approach to review and discuss the current range of responses that aim to reduce

the harms associated with young people’s recreational drug use in Europe. These responses

include: individually focused and group-based interventions (school-based drugs education

and prevention, mass media campaigns, motivational interviewing, and youth development

programmes) and ‘settings-based approaches’, which make changes to recreational settings,

such as nightclubs, or institutional settings, such as schools, to address the social and

environmental background of young people’s drug use.

Keywords: young people, drug use, prevalence, harm, intervention, Europe.

Introduction

This chapter focuses primarily on young people’s use of illegal drugs (rather than alcohol and

tobacco use). However, the potential for harm is likely to be greatest when young people use

both drugs and alcohol, and many of the interventions reviewed in this chapter are

considered to be appropriate for reducing the harms associated with both drug and alcohol

use. The chapter will begin by reviewing the prevalence of drug use among young people in

Europe and the related adverse health and other harms. The appropriateness and likely

effectiveness of different types of interventions that aim to reduce the harms associated with

young people’s recreational drug are then discussed. Harm reduction has traditionally

focused on adult ‘problem’ drug users, particularly injecting drug users (see, for example,

Ball, 2007, and Kimber et al., 2010), and neglected not only the harms associated with young

people’s recreational drug use but also how to reduce these harms.

This chapter considers young people’s recreational drug use to be drug use that occurs for

pleasure, typically with friends, in either formal recreational settings, such as nightclubs, and/

or informal settings, such as on the streets and in the home. This is thus a broader definition

than the one applied in other EMCDDA publications, which often focus specifically on young

people’s drug use within a ‘nightlife context’ (e.g. EMCDDA, 2002). This chapter is primarily

focused on young people aged 14–19, although some studies report on other age ranges

(e.g. 14–24) and therefore at times it has been necessary to define ‘young people’ more

broadly. Furthermore, data on prevalence and trends of drug use among young people often

aim to provide an indication of overall levels of use and therefore do not always distinguish

between recreational drug use and more problematic patterns of use.

Trends in young people’s recreational drug use in Europe

The European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs (ESPAD) and recent

general population surveys have revealed lower prevalence of use of cannabis and other

illicit drugs for European youth compared to youth in the United States (Hibell et al., 2004;

Hibell et al., 2009; EMCDDA, 2009). However, these overall European-level data mask

diversity within the EU in terms of young people’s use of cannabis, ‘club drugs’, such as

ecstasy and amphetamines, and cocaine.

Cannabis

The 2007 ESPAD data revealed that the highest lifetime prevalence of cannabis use among

15- to 16-year-old school students is in the Czech Republic (45 %), while Estonia, France, the

Netherlands, Slovakia and the United Kingdom reported prevalence levels ranging from

26 % to 32 % (Hibell et al., 2009). Lifetime prevalence levels of cannabis use of between 13 %

and 25 % are reported in 15 other countries. Less than 10 % of 15- to 16-year-old school

students report cannabis use in Greece, Cyprus, Romania, Finland, Sweden and Norway.

Early onset of cannabis use has been associated with the development of more intensive and

problematic forms of drug consumption later in life. In most of the 10 EU countries with

relatively high prevalence of frequent use, between 5 % and 9 % of school students had

initiated cannabis use at age 13 or younger. In addition, compared to the general population

of students, cannabis users are more likely to use alcohol, tobacco and other illicit drugs

(EMCDDA, 2009).

National survey data reported to the EMCDDA shows that in almost all EU countries

cannabis use increased markedly during the 1990s, in particular among school students. By

2003, between 30–40 % of 15- to 34-year-olds reported ‘lifetime use’ of cannabis in seven

countries, and more than 40 % of this age group reported ever having used cannabis in two

other countries. However, data from the 2007 ESPAD surveys suggests that cannabis use is

stabilising — and in some cases declining — among young people in Europe: of the 11 EU

countries for which it is possible to analyse trends between 2002 and 2007, four countries

showed overall decreases of 15 % or more in the proportion of 15- to 16-year-olds reporting

cannabis use in the last year, and in four other countries the situation appears stable (Hibell

et al., 2009; EMCDDA, 2009).

Ecstasy and amphetamines

It is estimated that 7.5 million young Europeans aged 15 to 34 (5.6 %) have ever tried

ecstasy, with around 2 million (1.6 %) using it during the last year (EMCDDA, 2009).

Estimates of prevalence are generally even higher among the subgroup of 15- to 24-yearolds,

for whom lifetime prevalence ranges between 0.4–18.7 % in European countries

(estimates fall between 2.1 % and 6.8 % in most European countries). Among 15- to 16-yearold

students lifetime prevalence of ecstasy use ranges between 1 % and 7 % in countries

surveyed in 2007 (EMCDDA, 2009).

Studies of recreational settings that are associated with drug use, such as dance events or

music festivals, provide further evidence regarding young people’s ecstasy and

amphetamine use. Estimates of young people’s drug use in these settings are typically high.

However, comparisons between surveys can only be made with the utmost caution, as the

age and gender distribution of survey respondents as well as variations in the setting may

lead to observed differences. Studies conducted in recreational settings in 2007 in five EU

countries (Belgium, Czech Republic, Latvia, Lithuania, Austria) reveal lifetime prevalence

estimates of 15–71 % for ecstasy use and 17–68 % for amphetamines (EMCDDA, 2009).

Much of party-going young people’s drug use occurs on weekends and during holiday

periods (EMCDDA, 2006b).

A further indication of the extent to which the use of these drugs may be concentrated

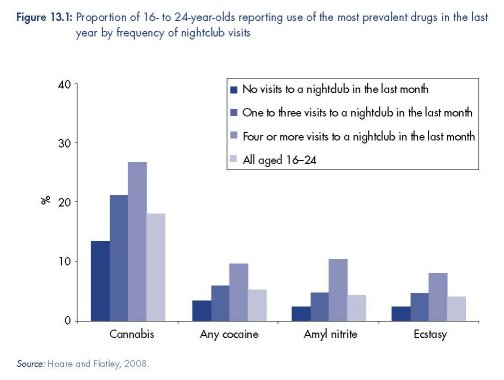

among the young, club-going population can found in the 2007/8 British Crime Survey

(Hoare and Flatley, 2008). The study found that those 16- to 24-year-olds who reported

visiting a nightclub four or more times in the last month were more than three times as

likely to have used ecstasy in the last year than those not attending nightclubs (2 % vs.

8 %) (Figure 13.1). In a French study that was carried out in 2004 and 2005 among 1 496

young people at ‘electronic’ music venues, 32 % of respondents reported ecstasy use and

13 % reported amphetamine use in the past month (Reynaud-Maurupt et al., 2007).

Among specific sub-populations that self-identified as ‘alternative’, prevalence estimates

for ecstasy and amphetamines were as high as 54 % and 29 %, respectively (Reynaud-

Maurupt, 2007).

Cocaine

Although cocaine is the second most commonly used illicit drug in Europe after cannabis

(EMCDDA, 2007), estimates of the prevalence of cocaine use among school students are very

low. Lifetime prevalence of cocaine use among 15- to 16-year-old students in the ESPAD

survey is between 1 % and 2 % in half of the 28 reporting countries, and in the rest it ranges

between 3 % and 5 % (Hibell et al., 2009; EMCDDA, 2009).

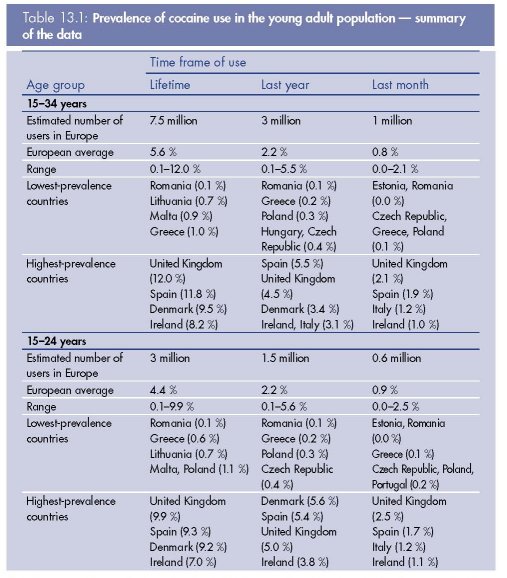

Note: European prevalence estimates are based on weighted averages from the most recent national surveys conducted

from 2001 to 2008 (mainly 2004–08), therefore they cannot be attached to a single year. The average prevalence for

Europe was computed by a weighted average according to the population of the relevant age group in each country. In

countries for which no information was available, the average EU prevalence was imputed. Population base is 133 million.

The data summarised here are available under ‘General population surveys’ in the EMCDDA 2009 statistical bulletin.

Source: EMCDDA, 2009.

Of the 4 million Europeans who used cocaine in the past year, around 3 million were young

people and young adults (EMCDDA, 2009). The prevalence of past-year cocaine use among

15- to 24-year-olds is estimated to be 2.2 %, which translates to about 1.5 million cocaine

users. In contrast to the prevalence estimates for cannabis or ecstasy use, which are highest

among the 15 to 24 age group, measures of more recent cocaine use (last year and last

month) are similar among the 15 to 24 and 25 to 34 age groups (see Table 13.1). Of the 11

countries for which it is possible to analyse trends in cocaine use between 2002 and 2007,

the proportion of 15- to 34-year-olds reporting cocaine use in the last year increased by

15 % or more in five countries (Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Portugal, United Kingdom), remained

stable in four (Germany, Spain, Slovakia, Finland) and only decreased in two countries

(Hungary, Poland).

Cocaine use is also strongly associated with alcohol use. For example, the British Crime

Survey 2007–08 found that among 16- to 24-year-olds who made nine or more visits to a

pub in the last month, 13.5 % reported using cocaine in the last year, compared to 1.7 %

among those who had not visited a pub (Hoare and Flatley, 2008). Visiting nightclubs was

also associated with higher cocaine use, as nearly 10 % of the 16- to 24-year-olds who

visited a club on four or more occasions during the last month reported using cocaine in the

last year, compared to 3.3 % among those who had not visited a club (Hoare and Flatley,

2008). Studies conducted in nightlife settings also report higher prevalence of cocaine use

among club-goers than among the general population (EMCDDA, 2007).

It is worth noting that alcohol is almost always the first drug with strong psychoactive and

mind-altering effects used by young people, and its widespread availability makes it the

main drug connected to poly-drug use among young adults, particularly in recreational

settings. Other psychoactive substances commonly referred to as ‘legal highs’ are

increasingly sold as alternatives to controlled drugs. In 2009, a snapshot study of 115

online shops located in 17 European countries showed that a range of herbal smoking

products and ‘party pills’ containing legal alternatives to controlled drugs were being sold

(EMCDDA, 2009).

Health and other harms

It is now widely acknowledged that recreational drug use can be an important source of

status and recreation for young people (Henderson et al., 2007); it can not only facilitate a

shared sense of group belonging and security (Fletcher et al., 2009a), but also a sense of

being different from other groups of young people (Shildrick, 2002). However, as

recreational drug use has increased among different sections of the youth population, so has

evidence of drug-related harm and concerns about the consequences of adolescent drug use.

Although the vast majority of this increase in drug use among young people has been

attributed to the use of ‘soft’ drugs (e.g. cannabis and ecstasy), these substances still have

health risks, especially for frequent users who are most at risk of harm.

Cannabis can cause short- and long-term health problems, such as nausea, anxiety, memory

deficits, depression and respiratory problems (Hall and Solowij, 1998; MacLeod et al., 2004;

Solowij and Battisti, 2008; Hall and Fischer, 2010). Although more research is needed on the

long-term effects of adolescent cannabis use on mental health, cannabis use is also thought

to increase the risk of mental health problems, particularly among frequent users (Hall, 2006;

Moore et al., 2007) and those with a predisposition for psychosis (Henquet et al., 2005).

Regular cannabis users can also become dependent (Melrose et al., 2007).

The true extent of future mental health problems due to adolescent ecstasy use is unclear, but

young ecstasy users may be at risk of depression in later life and there is evidence that

ecstasy use may also impair cognitive functions relevant to learning (Parrott et al., 1998;

Schilt et al., 2007). Dehydration, a more immediate risk for ecstasy users, can cause loss of

consciousness, coma and even death. Furthermore, evidence from cohort studies suggests

that early initiation and frequent use of ‘soft’ drugs may be a potential pathway to more

problematic drug use in later life (Yamaguchi and Kandel, 1984; Lynskey et al., 2003;

Ferguson et al., 2006).

Cocaine use can result in dependence and/or serious mental and physical health problems,

such as depression, paranoia, and heart and respiratory problems (Emmett and Nice, 2006).

Hence, although only a small minority of young people use cocaine (NatCen and NFER,

2007; Hibell et al., 2009), their numbers are increasing in some countries in Europe, posing

an increasing public health issue.

In addition to presenting direct health risks, adolescent drug use is also associated with

accidental injury, self-harm, suicide (Charlton et al., 1993; Beautrais et al., 1999; Thomas et

al., 2007) and other ‘problem’ behaviours, such as unprotected sex, youth offending and

traffic risk behaviours (Jessor et al., 1991; Home Office, 2002; Jayakody et al., 2005; Calafat

et al., 2009). For example, a recent report by the United Kingdom Independent Advisory

Group on Sexual Health and HIV (2007) has suggested that there are strong links between

drug use, ‘binge’ drinking and sexual health risk, with similar trends in these risk behaviours.

Furthermore, although the links between crime and heroin or cocaine dependence are well

known, there is increasing evidence of links between teenage cannabis use and youth

offending (e.g. Boreham et al., 2006). This is not to say that there is necessarily a direct

causal relationship between adolescent drug use and social problems, but there is clear

evidence that they cluster together among certain groups of young people.

A typology of interventions

There have been surprisingly few attempts to synthesise the evidence relating to interventions

in European countries addressing young people’s recreational drug use. Here we adopt a

typological approach to describe and discuss responses that aim to reduce the harms

associated with young people’s recreational drug use. These include: (1) individually focused

and group-based interventions — school-based drugs education and prevention, mass

media campaigns, motivational interviewing and youth development programmes — and (2)

‘settings-based approaches’ which make changes to recreational settings, such as nightclubs,

or institutional settings, such as schools, to address the social and environmental background

of young people’s drug use.

This is not an exhaustive list of interventions in Europe that target young people’s recreational

drug use. For example, we do not discuss interventions that are directed primarily at young

people’s parents rather than young people themselves (see Petrie et al., 2007 for a review of

the evidence relating to current parenting programmes). Social policies that may impact on

macro-social — or ‘structural’ — factors, such as youth cultures, poverty or social exclusion,

that are also associated with young people’s drug use, are also not discussed, because they

rarely aim to specifically reduce the harms associated with recreational drug use. The

decriminalisation of drugs, drug classification policies, and policies and enforcement to

reduce the supply of illicit drugs and illicit sales of prescription drugs are also beyond the

scope of this chapter.

Individual and group-based approaches

School-based drugs education and prevention

In Europe, schools provide universal access to young people under 16 and are widely

recognised as a key site for drugs education and prevention interventions that aim to prevent

or delay drug use and reduce the frequency of drug use during adolescence (Evans-Whipp

et al., 2004). However, evidence from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of classroom-based

drugs education interventions aiming to improve knowledge, develop skills and modify peer

norms suggest that the effect of these interventions on young people’s drug-use behaviour are

limited: a recent systematic review found that they can have positive effects but concluded

that these are small, inconsistent and generally not sustained (Faggiano et al., 2005). In other

words, drugs education may promote students’ ‘health literacy’ but is not sufficient on its own

for changing young people’s behaviour or reducing drug-related harms.

Faggiano and colleagues (2005) found that school-based drugs education programmes

based on a ‘comprehensive social influence approach’ and those that are delivered by other

students (rather than teachers) appear to have the most positive effects — programme

characteristics that were also associated with more positive effects in systematic reviews of

alcohol education and smoking prevention interventions in schools (Foxcroft et al., 2002;

Thomas and Perera, 2006). However, in reviewing the evidence for drug education

programmes in schools, Cahill (2007) has highlighted the difficulties of implementing

complex interventions such as peer-led programmes in school settings and suggested that

caution is also required with normative education to ensure that adolescents receive

appropriate messages.

A key challenge in Europe and elsewhere is therefore to pilot and further evaluate evidencebased

school-based drugs education and prevention interventions (Faggiano and Vigna-

Taglianti, 2008; Ringwalt et al., 2008). ‘Unplugged’ is an example of a European schoolbased

programme that employs a comprehensive social influence model. It aims to reduce

young people’s substance use via 12 interactive sessions addressing topics such as decisionmaking,

‘creative thinking’, effective communication, relationship skills, self-awareness,

empathy, coping skills and the risks associated with specific drugs (Van Der Kreeft et al.,

2009). A recent cluster RCT of the ‘Unplugged’ programme in 170 schools across seven

European countries suggested that curricula based on such a comprehensive social-influence

model are not only feasible to implement in schools in Europe, they may also reduce regular

cannabis use and delay progression to daily smoking and episodes of drunkenness

(Faggiano et al., 2008).

The ASSIST (A Stop Smoking in Schools Trial) programme in the United Kingdom provides an

example of an effective peer-led health promotion intervention that is feasible to deliver in

schools: a cluster RCT of the ASSIST programme involving 59 schools in Wales found a

significant reduction in smoking among the intervention group, including among the most

‘high risk’ groups of students (Campbell et al., 2008). The programme uses network analysis

to identify influential students and train them as peer supporters to ‘diffuse’ positive health

messages throughout the school. Researchers at the Centre for Drug Misuse Research in

Glasgow have recently piloted a peer-led drugs prevention programme based on the ASSIST

programme in two secondary schools in Scotland; this study suggested that it is feasible to

deliver cannabis and smoking education (CASE) together using this approach (Professor Mick

Bloor, personal communication). However, further research is needed to examine the effects

of this intervention on students’ drug use and drug-related harms.

Mass media campaigns

Mass media campaigns have become a popular tool among health promoters seeking to

inform young people about the risks associated with recreational drug use and/or seeking to

encourage current users to reduce their use and minimise the risk of harm. These

interventions, such as the recent United Kingdom FRANK advertising campaigns on the

mental health problems associated with recreational cannabis use (http://www.talktofrank.

com/cannabis.aspx), aim to increase the information available to young people and reframe

issues relating to young people’s recreational drug use on public health terms. These mass

media campaigns to raise awareness about the effects of drug use in the United Kingdom

have also been integrated with a ‘credible, non-judgemental and reliable’ online and

telephone drugs advice and information service for young people and their parents (Home

Office et al., 2006).

However, mass media campaigns that aim to reduce the harms associated with young

people’s recreational drug have rarely been evaluated to examine their effects on young

people’s behaviour, attitudes or intention to use drugs — and where they have, the findings

have not always been positive. A national survey to evaluate the United States Anti-Drug

Media Campaign suggested that mass media campaigns have little or no effect on changing

attitudes once young people have initiated drug use (Orwin et al., 2006), and may even

have harmful effects as those young people who were exposed to the adverts were more

likely to report cannabis use or an intention to use cannabis (Hornik et al., 2008). Similar

negative outcomes were reported in another large-scale evaluation of the Scottish cocaine

campaign ‘Know the score’: two-fifths (41 %) of respondents said that the campaign made

them more likely to find out more about cocaine and 12 % felt that the campaign had made

them more likely to experiment with cocaine (Phillips and Kinver, 2007). A meta-analysis of

evaluations of mass media campaigns to reduce smoking, drinking or drug use by Derzon

and Lipsey (2002) found that campaigns featuring messages about resistance skills appeared

to have the most harmful effects and were associated with significantly higher extent of

substance use than observed in control communities.

Flay and colleagues (1980) have suggested that the key factors to change behaviour via

mass media health promotion campaigns include: repetition of information over long time

periods, via multiple sources and at different times (including ‘prime’ or high-exposure times).

Mass media interventions also provide the opportunity to reach specific target groups within

a short timeframe (HDA, 2004). However, population-level mass media campaigns require a

significant financial investment (Hornik, 2002) and are competing in an increasingly crowded

market with a range of other information available to young people (Randolph and

Viswanath, 2004).

Brief interventions

Approaches based on early screening of young people’s drug use and brief behaviour change

interventions, such as motivational interviewing, have been rigorously evaluated in the United

Kingdom and elsewhere (Tait and Hulse, 2003; Tevyaw and Monti, 2004). Developed by Miller

and Rollnick, motivational interviewing has been defined as a ‘client-centred, directive method

for enhancing intrinsic motivation to change by exploring and resolving ambivalence’ (Miller

and Rollnick, 2002). Evidence suggests that it is feasible to deliver brief one-to-one interventions

such as motivational interviewing to young drug-users in a wide range of settings, such as

youth centres, further education colleges, general practitioners’ surgeries and ‘emergency

rooms’ (Gray et al., 2005; Martin et al., 2005; McCambridge et al., 2008), and where brief

interventions employ motivational interviewing principles they have been found to be effective

in reducing young people’s drug use (Tait and Hulse, 2003; McCambridge and Strang, 2004;

Tevyaw and Monti, 2004; Grenard et al., 2006).

Reviewing the evidence from trials of brief motivational interviewing interventions, Tevyaw

and Monti (2004) found consistent evidence that this approach can ‘result in decreases in

substance-related negative consequences and problems, decrements in substance use and

increased treatment engagement’, and these effects appear to be greatest among young

people who report the heaviest patterns of drug use and the least motivation to change prior

to intervention. Researchers have also found evidence that as little as a ‘single session’ of

motivational interviewing can significantly reduce cannabis use among heavy users and

among those young people considered to be at ‘high risk’ of progressing to more

problematic drug use (McCambridge and Strang, 2004).

However, the existing evidence suggests that, although brief interventions based on

motivational interviewing can encourage young people to moderate their drug use in the

short term, this approach is unlikely to have long-term effects on its own (McCambridge and

Strang, 2005) and may therefore need to form part of a more holistic approach to harm

reduction. Further research is also needed to examine the essential elements of motivational

interviewing interventions and their effects on developmental transitions during adolescence

(McCambridge and Strang, 2004; McCambridge et al., 2008). Furthermore, motivational

interviewing is complex and requires practitioners to develop skills and experiences over time

in order to deliver it proficiently. As such, it is likely to be difficult to replicate and evaluate

existing intervention more widely across Europe at present while is there is limited capacity to

deliver such interventions.

Youth development

Youth development programmes work with groups of teenagers and aim to promote their

personal development, self-esteem, positive aspirations and good relationships with adults in

order to reduce potentially harmful behaviours, such as drug use (Quinn, 1999). As well as

enhancing young people’s interests, skills and abilities, youth projects also have the potential

to divert young people away from drug use through engaging them in more positive sources

of recreation, and youth workers can provide credible health messages and signpost health

services. There has been considerable interest from policymakers in youth development

interventions as an alternative means of reducing young people’s drug use. For example, in

the United Kingdom youth work programmes targeted at socially disadvantaged and

‘excluded’ young people and other ‘at-risk’ groups have been supported by the Government,

including new community-based youth development projects such as the Positive Futures

initiative and the Young People’s Development Programme (Department for Education and

Skills, 2005).

Evaluations of youth development interventions targeted at vulnerable young people have

shown mixed results: although some studies report that youth development interventions have

had positive effects (Philliber et al., 2001; Michelsen et al., 2002), others suggest these

interventions may be ineffective (Grossman and Sipe, 1992) or even harmful (Palinkas et al.,

1996; Cho et al., 2005; Wiggins et al., 2009). It appears that involvement in such programmes

may result in an increase in drug use where: young people are stigmatised (or ‘labelled’) via

targeting, which further reduces their self-esteem and aspirations; and/or harmful social

network effects arise through aggregating ‘high risk’ young people together, thus introducing

young people to new drug-using peers (Bonell and Fletcher, 2008). For example, in a study

examining an intervention for high-risk high school students (Cho et al., 2005), greater

exposure to the programme predicted greater ‘high-risk peer bonding’ and more negative

outcomes, including higher prevalence of cannabis and alcohol use (Sanchez et al., 2007).

Youth development approaches are therefore likely to be most appropriate and effective where

they are delivered in universal settings to avoid the harmful ‘labelling’ and social network

effects associated with targeting ‘high risk’ youth. In the United States, after-school and

community-based youth development programmes promoting civic engagement and learning

through the principle of ‘serve and learn’ — which involves voluntary service, reflection on this

voluntary service though discussion groups, social development classes and learning support

— have been found to be effective in reducing a wide range of risky behaviours including

involvement with drugs and teenage pregnancy (Michelsen et al., 2002; Harden et al., 2009).

Where youth workers aim to target ‘high risk’ groups of young people, ‘detached’, street-based

services may be more appropriate in order to avoid the potentially harmful social network

effects associated with aggregating these young people together in youth centres, although this

needs further evaluation (Fletcher and Bonell, 2008). Examples of street-based youth projects

include the Conversas de Rua programme in Lisbon (http://www.conversasderua.org/) and the

‘Off the Streets’ community youth initiative in Derry, Northern Ireland.

Settings-based approaches

Settings-based approaches to health promotion have their roots in the World Health

Organization’s (WHO) Health for All initiative and the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion

(WHO, 1986). The Ottawa Charter argued that health is influenced by where people ‘learn,

work, play and love’, integrated new thinking about health promotion, and heralded the start

of this new approach (Young, 2005). Key principles regarded as necessary to achieve the

status of a ‘health promoting setting’ are the creation of a healthy environment and the

integration of health promotion into the routine activities of the setting (Baric, 1993). Since the

late 1980s, health promotion interventions have been widely established, which make

changes to recreational ‘settings’, such as nightclubs, or institutional ‘settings’, such as schools,

to address the social and environmental determinants of harmful drug use.

Interventions in recreational settings

Studies of young people in Europe who attend dance music events consistently report much

higher prevalence of drug use than found in surveys of the general population (EMCDDA,

2006a). A ‘Hegemonic Recreational Nightlife Model’ has been used to understand how

recreational drug use and the settings where this takes place now govern many young people’s

weekend entertainment and social networks, and can give ‘meaning’ to their lives through

intensive participation (Calafat et al., 2003). The recreation industry thus not only supplies

services but also contributes to defining entertainment and creating the conditions in which

recreational drug use takes place. In turn, there is a wide range of risk behaviours associated

with recreational drug use in this context (e.g. violence, sexual risk, traffic risk), and these have

been found to be influenced by factors such as a ‘permissive atmosphere’ (Homel and Clark,

1994; Graham et al., 2006), overcrowding (Macintyre and Homel, 1997), overt sexual activity

(Homel et al., 2004; Graham et al., 2006) and transport habits (Calafat et al., 2009).

A wide range of interventions now aim to change the physical context and/or the social and

cultural norms of recreational settings to address the conditions and influences associated

with the most ‘habitual’ contexts for young people’s recreational drug use, such as nightlife

settings and music festivals, and the potential harms arising from use in such contexts. For

example, several organisations in Europe have launched safer nightlife guidelines. ‘Safer

dancing’ guidelines, developed in the United Kingdom, have now become an important tool

in this field. Other examples are the Safe Nightlife initiative in Holstebro, Denmark, and the

London Drug Policy Forum’s ‘Dance Till Dawn Safely’ initiative.

Safe-clubbing guidelines aim to reduce opportunities for drug-related problems to occur in

these settings and include promoting the accessibility of free water, the immediate availability

of first aid and outreach prevention work with young clubbers. Reports on the availability of

such measures, in nightclubs with sufficiently large target populations for the intervention to

be implemented, were collated by the EMCDDA in 2008 (EMCDDA, 2009). These reports

highlighted the limited availability of simple measures to prevent or reduce health risks and

drug use in European nightlife settings. For example, it was found that outreach prevention

work was provided in the majority of dance clubs in only two out of 20 European countries

(Slovenia and Lithuania), while free water was still not routinely available in nine of the 20

countries. Furthermore, while 12 countries now report having developed guidelines for

nightlife venues, only the Netherlands, Slovenia, Sweden and the United Kingdom report that

they are monitored and implemented.

The most widely implemented intervention in recreational settings is the responsible beverage

service (RBS) guidelines to support staff and managers in harm reduction strategies. A recent

systematic review, however, concluded that there is no reliable evidence that these interventions

are effective in preventing injuries or other harms (Ker and Chinnock, 2008; see also Herring et

al., 2010). Community-based approaches to responsible service may produce the largest and

most significant effects. For example, Stockholm Prevents Alcohol and Drug Problems (STAD) is

a community-based prevention programme that started in 1996 in Stockholm to promote

community mobilisation, the training of bar staff in RBS and stricter enforcement of existing

alcohol licensing and drug laws: an evaluation found a decrease in alcohol-related problems,

increased refusal to serve minors and a 29 % reduction in assaults (Wallin and Andréasson,

2005). However, large-scale community-based interventions are likely to be expensive and

need political commitment. Other factors may also limit compliance to responsible service, such

as low pay, high staff turnover and a stressful working environment, and the efficacy of such

interventions is therefore likely be greater when enforced as a statutory intervention (Ker and

Chinnok, 2008; Wallin and Andréasson, 2005).

Promising interventions that need further evaluation are glassware bans in recreational

settings (Forsyth, 2008) and the creation of collaborating guidelines between licensed

premises and accident and emergency services (Wood et al., 2008). Some nightclubs in

Europe have now incorporated a first aid service inside the premises, but we are not aware

of any evaluations of their effectiveness. Further research and effective collaboration between

health promoters, nightlife settings and the alcohol industry are likely to be crucial in

reducing the harms associated with young people’s recreational drug use. However, building

relationships across these sectors is not straightforward. ‘Codes of practice’ with the potential

of enforcement may be the most appropriate means to facilitate engagement across the

sectors (Graham, 2000). At present, there seems to be a reluctance to enforce greater

accountability through law enforcement. The Tackling Alcohol Related Street Crime (TASC)

intervention in Cardiff provides an example of a broad and multifaceted intervention

implemented largely by the police that produced reductions in violence at the relevant

premises, although further research is needed to examine the feasibility of introducing policeled

approaches in nightlife settings more generally (Maguire et al., 2003).

Finally, on-site pill testing in recreational settings has been a controversial issue for several

years and appears to be steadily less common in Europe. The main arguments against pill

testing are the limited capacity of on-site tests to accurately detect harmful substances and

that, by permitting on-site pill testing, contradictory messages are being sent out about the

risks related to both use and possession of controlled substances (EMCDDA, 2006b).

Whole-school interventions

Following the emergence of ‘settings-based approaches’ to health promotion, traditional

classroom-based drugs education programmes have gradually been accompanied by

additional strategies in schools that address more ‘upstream’ environmental, social and

cultural determinants of young people’s drug use, such as student disengagement and

truancy. The origin of this new ‘settings’ approach to health promotion in schools is attributed

to a WHO conference in 1989 which led to the publication of The Healthy School (Young

and Williams, 1989). Following this report, ‘whole-school’ approaches have received

continued support from international networks, such as the WHO, the European Network of

Health Promoting Schools (ENHPS) and the International School Health Network (ISHN)

(WHO, 1998; McCall et al., 2005).

Using cross-sectional survey data from 10 European countries, Canada and Australia,

Nutbeam and colleagues (1993) found a consistent relationship between ‘alienation’ at

secondary school and ‘abusive behaviours’, such as smoking, drinking and drug use, and

warned that ‘schools can damage your health’. Further analysis of this data suggested that

students’ perceptions of being treated fairly, school safety and teacher support were related

to substance use (Samdal et al., 1998). Three recent systematic reviews of experimental

studies of ‘whole-school health promotion interventions’, which make changes to schools’

physical environment, governance and management, policies, and/or educational and

pastoral practices, have found that these approaches appear to be ‘promising’ for reducing

a wide range of ‘risky’ health behaviours among young people (Lister-Sharpe et al., 1999;

Mukoma and Flisher, 2004; Fletcher et al., 2008). The review by Fletcher and colleagues

found that changes to the school social environment that increase student participation,

improve teacher–student relationships, promote a positive school ethos and reduce

disengagement are associated with reduced drug use. The Gatehouse Project in Australia is

one of the best-known examples (http://www.rch.org.au/gatehouseproject/).

Although various pathways may plausibly underlie school effects on drug use and drugrelated

harms, three potential pathways via which school effects on drug use may occur have

been identified: peer-group sorting and drug use as a source of identity and bonding among

students who are disconnected from the main institutional markers of status; students’ desire

to ‘fit in’ at schools perceived to be unsafe, and drug use facilitating this; and/or drug use as

a strategy to manage anxieties about schoolwork and escape unhappiness at schools lacking

effective social support systems (Fletcher et al., 2009b). This evidence further supports ‘wholeschool’

interventions to reduce drug use through: recognising students’ varied achievements

and promoting a sense of belonging; reducing bullying and aggression; and providing

additional social support for students.

Discussion

There is considerable data on the prevalence of recreational drug use among young people

in European countries, and the related adverse health and other harms. However, much of

this evidence regarding overall prevalence of young people’s drug use is gained through

school-based surveys and we cannot assume that patterns of drug use among young people

who have low school attendance and young people who have been excluded from school

will therefore be accurately captured in these surveys; there are also practical problems with

collecting reliable self-report data about students’ use of drugs in school-based surveys

(McCambridge and Strang, 2006). Street-based surveys of young people, such as the

Vancouver Youth Drug Reporting System (VCH, 2007), could therefore complement existing

monitoring systems in Europe. Nonetheless, current European surveys that monitor

prevalence and trends are well established and allow cross-national comparisons to be made

regarding young people’s drug use.

In response to public and political concerns about the harmful consequences of young people’s

drug use, a wide range of interventions have been implemented throughout Europe and

elsewhere. There is no ‘magic bullet’, and harm reduction strategies in this context will need to

encompass both universal and targeted strategies that seek to prevent or delay drug use,

reduce the frequency of drug use during adolescence, and make changes to risk environments.

Mass media campaigns may be politically important but appear to be largely ineffective (and

occasionally counter-productive). If they are to continue to play a role in informing young

people about the risks associated with recreational drug use, health promoters should design

mass media campaigns in conjunction with young people and — although it is difficult to

attribute changes in behaviour to mass media interventions — these campaigns should be

subjected to pilot trials prior to ‘roll-out’. Future mass media campaigns should also pay close

attention to providing easy access to information via the Internet and telephone advice lines.

Based on the current evidence, school-based programmes show greater promise for

preventing young people initiating drug use at a young age than mass media interventions.

Comprehensive social influence models and peer-led programmes based on the ‘diffusion of

innovations’ approach are the most promising approaches for drugs education and

prevention in schools, and thus should be piloted and evaluated more widely in Europe.

Interventions that promote a positive school ethos and reduce student disaffection and

truancy are likely to be an effective complement to these drugs education and prevention

interventions in schools. These school-level ‘settings’ interventions focusing on the more

‘upstream’ determinants of risk should also now be piloted and evaluated in Europe to

examine their potential for harm reduction.

Motivational interviewing shows considerable promise in a wide range of settings, including

among those young people with the heaviest patterns of drug use. However, motivational

interviewing is resource-intensive and where there is insufficient investment this will impact on

its potential for harm reduction. New training programmes in motivational interviewing

should therefore be considered a priority in European countries, initially to build capacity for

greater intervention in recreational contexts and among professionals working with high-risk

young people.

Youth development approaches appear to be most appropriate and effective in addition to,

rather than as an alternative to, school, such as after-school and school-holiday programmes

promoting self-esteem, positive aspirations, supportive relationships and learning through the

principle of ‘serve and learn’, which is based on volunteering in the local community. In

addition, because of its focus on working with existing peer groups (and thus its ability to avoid

the potentially harmful effects associated with centre-based youth projects), as well as its

greater reach and flexibility, detached, street-based youth work may be the most appropriate

and effective approach for targeting those young people deemed at ‘high risk’ of harm. These

approaches should be the subject of further evaluation in Europe with high-risk groups.

Perhaps of greatest concern at present is the lack of agreement and guidance about what to

do in recreational settings in Europe to reduce drug-related harm. There are few statutory

policies governing the most ‘habitual’ contexts for young people’s recreational drug use, such

as nightlife settings and music festivals, or rigorous evaluations of interventions in such

settings in Europe. Guidelines promoting the accessibility of free water, immediate availability

of first aid and outreach services have been implemented with promising effects in some (but

by no means all) European countries. These should be enforced through changing them into

laws where possible and be accompanied by additional efforts to encourage responsible

alcohol service and reduce other risky behaviours.

References

Ball, A. (2007), ‘HIV, injecting drug use and harm reduction: a public health response’, Addiction 102, pp. 684–90.

Baric, L. (1993), ‘The settings approach: implications for policy and strategy’, Journal of the Institute of Health

Education 31, pp. 17–24.

Beautrais, A. L., Joyce, P. R. and Mulder, R. T. (1999), ‘Cannabis abuse and serious suicide attempts’, Addiction,

94, pp. 1155–64.

Bonell, C. and Fletcher, A. (2008), ‘Addressing the wider determinants of problematic drug use: advantages of

whole-population over targeted interventions’, International Journal of Drug Policy 19, pp. 267–9.

Boreham, R., Fuller, E., Hills, A. and Pudney, S. (2006), The arrestee survey annual report: Oct. 2003–Sept. 2004,

England and Wales, Home Office, London.

Cahill, H. W. (2007), ‘Challenges in adopting evidence-based school drug education programmes’, Drug and

Alcohol Review 26, pp. 673–9.

Calafat, A., Fernandez, C., Juan, M., et al. (2003), Enjoying nightlife in Europe: the role of moderation, Irefrea,

Palma de Mallorca.

Calafat, A., Blay, N., Juan, M., et al. (2009), ‘Traffic risk behaviors at nightlife: drinking, taking drugs, driving,

and use of public transport by young people’, Traffic Injury Prevention 10, pp. 162–9.

Campbell, R., Starkey, F., Holliday, J., et al. (2008), ‘An informal school-based peer-led intervention for smoking

prevention in adolescence (ASSIST): a cluster randomised trial’, Lancet 371, pp. 1595–602.

Charlton, J., Kelly, S. and Dunnell, K. (1993), ‘Suicide deaths in England and Wales: trends in factors associated

with suicide deaths’, Population Trends 7, pp. 34–42.

Cho, H., Hallfors, D. D. and Sanchez, V. (2005), ‘Evaluation of a high school peer group intervention for at-risk

youth’, Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 33, pp. 363–74.

Department for Education and Skills (2005), Every child matters: change for children, young people and drugs, Her

Majesty’s Stationery Office, London.

Derzon, J. H. and Lipsey, M. W. (2002), ‘A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of mass-communication for changing

substance-use knowledge, attitudes and behaviour’, in Crano, W. D. and Burgoon, M. (eds), Mass media and drug

prevention: classic and contemporary theories and research, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Matwah.

Emmett, D. and Nice, G. (2006), Understanding street drugs, Jessica Kingsley Publishers, London.

EMCDDA (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction) (2002), Recreational drug use: a key EU

challenge, Drugs in focus, European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, Lisbon.

EMCDDA (2006a), Annual report 2006: the state of the drugs problem in Europe, European Monitoring Centre for

Drugs and Drug Addiction, Lisbon.

EMCDDA (2006b), Developments in drug use within recreational settings, European Monitoring Centre for Drugs

and Drug Addiction, Lisbon.

EMCDDA (2007), Cocaine and crack cocaine: a growing public health issue, European Monitoring Centre for

Drugs and Drug Addiction, Lisbon.

EMCDDA (2009), Annual report 2009: the state of the drugs problem in Europe, European Monitoring Centre for

Drugs and Drug Addiction, Lisbon.

Evans-Whipp, T., Beyers, J. M., Lloyd, S., et al. (2004), ‘A review of school drug polices and their impact on

youth substance use’, Health Promotion International 19, pp. 227–34.

Faggiano, F. and Vigna-Taglianti, F. D. (2008), ‘Drugs, illicit — primary prevention strategies’, International

Encyclopaedia of Public Health 2, pp. 249–65.

Faggiano, F., Vigna-Taglianti, F. D., Versino, E., et al. (2005), ‘School-based prevention for illegal drugs use’,

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2, Art. No. CD003020.

Faggiano, F., Galanti, M. R., Bohrn, K., et al. (2008), ‘The effectiveness of a school-based substance abuse

prevention program: EU–Dap cluster randomised controlled trial’, Preventive Medicine 47, pp. 537–43.

Ferguson, D. M., Boden, J. M. and Horwood, L. J. (2006), ‘Cannabis use and other illicit drug use: testing the

cannabis gateway hypothesis’, Addiction 101, pp. 556–69.

Flay, B. R., DiTecco, D. and Schlegel, R. P. (1980), ‘Mass media in health promotion: an analysis extended

information-processing model’, Health Education and Behavior 7, pp. 127–47.

Fletcher, A. and Bonell, C. (2008), ‘Detaching youth work to reduce drug and alcohol-related harm’, Public Policy

Research 15, pp. 217–23.

Fletcher, A., Bonell, C. and Hargreaves, J. (2008), ‘School effects on young people’s drug use: a systematic

review of intervention and observational studies’, Journal of Adolescent Health 42, pp. 209–20.

Fletcher, A., Bonell, C., Sorhaindo, A. and Rhodes, T. (2009a), ‘Cannabis use and “safe” identities in an innercity

school risk environment’, International Journal of Drug Policy 20, pp. 244–50.

Fletcher, A., Bonell, C., Sorhaindo, A. and Strange, V. (2009b), ‘How might schools influence young people’s drug

use? Development of theory from qualitative case-study research’, Journal of Adolescent Health 45, pp. 126–32.

Forsyth, A. J. M. (2008), ‘Banning glassware from nightclubs in Glasgow (Scotland): observed impacts,

compliance and patrons views’, Alcohol and Alcoholism 43, pp. 111–17.

Foxcroft, D. R., Ireland, D., Lowe, G. and Breen, R. (2002), ‘Primary prevention for alcohol misuse in young

people’, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 3, Art. No. CD003024.

Graham, K. (2000), ‘Preventive interventions for on-premise drinking: a promising but under researched area of

prevention’, Contemporary Drug Problems 27, pp. 593–668.

Graham, K., Bernards, S., Osgood, D. W. and Wells, S. (2006), ‘Bad nights or bad bars? Multi-level analysis of

environmental predictors of aggression in late-night large-capacity bars and clubs’, Addiction 101, pp. 1569–80.

Gray, E., McCambridge, J. and Strang, J. (2005), ‘The effectiveness of motivational interviewing delivered by

youth workers in reducing drinking, cigarette and cannabis smoking among young people: quasi-experimental

pilot study’, Alcohol and Alcoholism 40, pp. 535–9.

Grenard, J. L., Ames, S. L., Pentz, M. A. and Sussman, S. (2006), ‘Motivational interviewing with adolescents and

young adults for drug-related problems’, International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health 18, pp. 53–67.

Grossman, J. B. and Sipe, C. L. (1992), Report on the long-term impacts (STEP program), Public/Private Ventures,

Philadelphia.

Hall, W. (2006), ‘The mental health risks of adolescent cannabis use’, PLoS Medicine 3, p. e39.

Hall, W. and Fischer, B. (2010), ‘Harm reduction policies for cannabis’, in European Monitoring Centre for Drugs

and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA), Harm reduction: evidence, impacts and challenges, Rhodes, T. and Hedrich, D.

(eds), Scientific Monograph Series No. 10, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

Hall, W. and Solowij, N. (1998), ‘Adverse effects of cannabis’, Lancet 352, pp. 1611–16.

Harden, A., Brunton, G., Fletcher, A. and Oakley, A. (2009), ‘Teenage pregnancy and social disadvantage:

systematic review integrating controlled trials and qualitative studies’, BMJ 339, b4254.

HDA (Health Development Agency) (2004), The effectiveness of public health campaigns, Health Development

Agency, London.

Henderson, S., Holland, J., McGrellis, S., Sharpe, S. and Thompson, R. (2007), Inventing adulthoods: a

biographical approach to youth transitions, SAGE, London.

Henquet, C., Krabbendam, L., Spauwen, J., et al. (2005), ‘Prospective cohort study of cannabis use,

predisposition for psychosis, and psychotic symptoms in young people’, BMJ 330, pp. 11–16.

Herring, R., Thom, B., Beccaria, F., Kolind, T. and Moskalewicz, J. (2010), ‘Alcohol harm reduction in Europe’, in

European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA), Harm reduction: evidence, impacts and

challenges, Rhodes, T. and Hedrich, D. (eds), Scientific Monograph Series No. 10, Publications Office of the

European Union, Luxembourg.

Hibell, B., Anderson, B., Bjarnsson, T., et al. (2004), The ESPAD report 2003: alcohol and other drug use among

students in 35 countries, The Swedish Council for Information on Alcohol and Other Drugs, Stockholm.

Hibell, B., Guttormsson, U., Ahlström, S., et al. (2009), The 2007 ESPAD report: substance use among students in 35

European countries, The Swedish Council for Information on Alcohol and Other Drugs, Stockholm.

Hoare, J. and Flatley, J. (2008), Drug misuse declared: findings from the 2007/08 British Crime Survey, Her

Majesty’s Stationery Office, London.

Home Office (2002), Updated national drugs strategy, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, London.

Home Office, Department of Health, Department for Education and Skills (2006), FRANK review, Her Majesty’s

Stationery Office, London.

Homel, R. and Clark, J. (1994), ‘The prediction and prevention of violence in pubs and clubs’, Crime Prevention

Studies 3, pp. 1–46.

Homel, R., Carvolth, R., Hauritz, M., McIlwain, G. and Teague, R. (2004), ‘Making licensed venues safer for

patrons: what environmental factors should be the focus of interventions?’, Drug and Alcohol Review 23, pp. 19–29.

Hornik, R. (2002), ‘Public health communication: making sense of contradictory evidence’, in Hornik, R., Public

health communication: evidence for behavior change, Erlbaum, Mahwah.

Hornik, R., Jacobsohn, L., Orwin, R., Piesse, A., and Kalton, G. (2008), ‘Effects of the National Youth Anti-Drug

Media Campaign on youths’, American Journal of Public Health 98, pp. 2229–36.

Independent Advisory Group on Sexual Health and HIV (2007), Sex, drugs, alcohol and young people: a review of

the impact drugs and alcohol has on the sexual behaviour of young people, Department of Health, London.

Jayakody, A., Sinha, S., Curtis, K., et al. (2005), Smoking, drinking, drug use, mental health and sexual behaviour

in young people in East London, Department of Health/Teenage Pregnancy Unit, London.

Jessor, R., Donovan, J. E. and Costa, F. M. (1991), Beyond adolescence: problem behaviour and young adult

development, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Ker, K. and Chinnock, P. (2008), ‘Interventions in the alcohol server setting for preventing injuries’, Cochrane

Database of Systematic Reviews 3, Art. No. CD005244.

Kimber, J., Palmateer, N., Hutchinson, S., et al. (2010), ‘Harm reduction among injecting drug users: evidence of

effectiveness’, in European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA), Harm reduction:

evidence, impacts and challenges, Rhodes, T. and Hedrich, D. (eds), Scientific Monograph Series No. 10,

Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

Lister-Sharp, D., Chapman, S., Stewart-Brown, S. and Sowden, A. (1999), ‘Health promoting schools and health

promotion in schools: two systematic reviews’, Health Technology Assessment 3 (22), pp. 1–207.

Lynskey, M. T., Heath, A. C., Bucholz, K. K., et al. (2003), ‘Escalation of drug use in early onset cannabis users vs

co-twin controls’, JAMA 289, pp. 427–33.

McCall, D. S., Rootman, I. and Bayley, D. (2005), ‘International school health network: an informal network for

advocacy and knowledge exchange’, Promotion and Exchange 12, pp. 173–7.

McCambridge, J. and Strang, J. (2004), ‘The efficacy of single-session motivational interviewing in reducing drug

consumption and perceptions of drug-related risk and harm among young people’, Addiction 99, pp. 39–52.

McCambridge, J. and Strang, J. (2005), ‘Deterioration over time in effect of motivational interviewing in reducing

drug consumption and related risk among young people’, Addiction 100, pp. 470–8.

McCambridge, J. and Strang, J. (2006), ‘The reliability of drug use collected in the classroom: what is the

problem, why does it matter and how should it be approached?’, Drug and Alcohol Review 25, pp. 413–18.

McCambridge, J., Slym, R. L. and Strang, J. (2008), ‘Randomized controlled trial of motivational interviewing

compared with drug information and advice for early information among young cannabis users’, Addiction 103,

pp. 1819–20.

Macintyre, S. and Homel, R. (1997), ‘Danger on the dance floor: a study of interior design, crowding and

aggression in nightclubs’, in Homel, R. (ed.) Policing for prevention: reducing crime, public intoxication and injury,

Criminal Justice Press, New York.

MacLeod, J., Oakes, R., Oppenkowski, T., et al. (2004), ‘How strong is the evidence that illicit drug use by young

people is an important cause of psychological or social harm? Methodological and policy implications of a

systematic review of longitudinal, general population studies’, Lancet 363, pp. 1579–88.

Maguire, M., Morgan, R. and Nettleton, H. (2003), Reducing alcohol-related violence and disorder: an evaluation

of the ‘TASC’ project, Home Office, London.

Martin, G., Copeland, J. and Swift, W. (2005), ‘The adolescent cannabis check-up: feasibility of a brief

intervention for cannabis users’, Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 29, pp. 207–13.

Melrose, M., Turner, P., Pitts, J. and Barrett, D. (2007), The impact of heavy cannabis use on young people:

vulnerability and youth transitions, Joseph Rowntree Foundation, York.

Michelsen, E., Zaff, J. F. and Hair, E. C. (2002), A civic engagement program and youth development: a synthesis,

Child Trends, Edna McConnell Clark Foundation, New York.

Miller, W. R. and Rollnick, S. (2002), Motivational interviewing: preparing people for change, Guildford Press, London.

Moore, T. H. M., Zammit, S., Lingford-Hughes, A., et al. (2007), ‘Cannabis use and risk of psychotic or affective

mental health outcomes: a systematic review’, Lancet 370, pp. 319–28.

Mukoma, W. and Flisher, A. J. (2004), ‘Evaluations of health promoting schools: a review of nine studies’, Health

Promotion International 19, pp. 357–68.

NatCen and NFER (2007), Smoking, drinking and drug use among young people in England in 2006: headline

figure, NHS Information Centre, London.

Nutbeam, D., Smith, C., Moore, L. and Bauman, A. (1993), ‘Warning! Schools can damage your health: alienation

from school and its impact on health behaviour’, Journal of Paediatric and Child Health 29, pp. S25–S30.

Orwin, R., Cadell, D., Chu, A., et al. (2006), Evaluation of the National Youth Anti-Drug Media Campaign, NIDA,

Rockville.

Palinkas, L. A., Atkins, C. J., Miller, C. and Ferreira, D. (1996), ‘Social skills training for drug prevention in highrisk

female adolescents’, Preventive Medicine 25, pp. 692–701.

Parrott, A. C., Lees, A., Garnham, N. J., Jones, M. and Wesnes, K. (1998), ‘Cognitive performance in

recreational users of MDMA or “ecstasy”: evidence for memory deficits’, Journal of Psychopharmacology 12, pp.

79–83.

Petrie, J., Bunn, F. and Byrne, G. (2007), ‘Parenting programmes for preventing tobacco, alcohol or drugs misuse

in children <18: a systematic review’, Health Education Research 22, pp. 177–91.

Philliber, S., Williams, K., Herrling, S. and West, E. (2001), ‘Preventing pregnancy and improving health care

access among teenagers: an evaluation of the Children’s Aid Society-Carrera Program’, Perspectives on Sexual

and Reproductive Health 34, pp. 244–51.

Phillips, R. and Kinver, A. (2007), Know the score: cocaine wave 4 — 2006/07 post-campaign evaluation, Scottish

Executive Research Group, Edinburgh.

Quinn, J. (1999), ‘Where need meets opportunity: youth development programs for early teens’, The Future of

Children 9, pp. 96–116.

Randolph, W. and Viswanath, K. (2004), ‘Lessons learned from public health mass media campaigns: marketing

health in a crowded media world’, Annual Review of Public Health 25, pp. 419–37.

Reynaud-Maurupt, C., Chaker, S., Claverie, O., et al. (2007), A Pratiques et opinions liées aux usages des

substances psychoactives dans l’espace festif «musiques électroniques», TRENDS, Observatoire Français des Drogues

et des Toxicodependences.

Ringwalt, C., Vincus, A. A., Hanley, S., et al. (2008), ‘The prevalence of evidence-based drug use prevention

curricula in U.S. middle schools in 2005’, Prevention Science 9, pp. 276–87.

Samdal, O., Nutbeam, D., Wold, B. and Kannas, L. (1998), ‘Achieving health and educational goals through

school: a study of the importance of the school climate and the student’s satisfaction with school’, Health

Education Research: Theory and Practice 13, pp. 383–97.

Sánchez, V., Steckler, A., Nitirat, P., et al. (2007), ‘Fidelity of implementation in a treatment effectiveness trial of

Reconnecting Youth’, Health Education Research 22, pp. 95–107.

Schilt, T., Maartje, M., de Win, M. L., et al. (2007), ‘Cognition in novice ecstasy users with minimal exposure to

other dugs: a prospective cohort study’, Archives of General Psychiatry 64, pp. 728–36.

Shildrick, T. (2002), ‘Young people, illicit drug use and the question of normalization’, Journal of Youth Studies 5,

pp. 35–48.

Solowij, N. and Battisti, R. (2008), ‘The chronic effects of cannabis on memory in human: a review’, Current Drug

Abuse Reviews 1, pp. 81–98.

Tait, R. J. and Hulse, G. K. (2003), ‘A systematic review of the effectiveness of brief interventions with substance

using adolescents by type of drug’, Drug and Alcohol Review 22, pp. 337–46.

Tevyaw, T. O. and Monti, P. M. (2004), ‘Motivational enhancement and other brief interventions for adolescent

substance use: foundations, applications and evaluations’, Addiction 99, pp. 63–75.

Thomas, J., Kavanagh, J., Tucker, H., et al. (2007), Accidental injury, risk-taking behaviour and the social

circumstances in which young people (aged 12–24) live: a systematic review, EPPI-Centre, London.

Thomas, R. E. and Perera, R. (2006), ‘School-based programmes for preventing smoking’, Cochrane Database of

Systematic Reviews 3, Art. No. CD001293.

Van Der Kreeft, P., Wiborg, G., Galanti, M. R., et al. (2009), ‘“Unplugged”: a new European school programme

against substance abuse’, Drugs: education, prevention and policy 16, pp. 167–81.

VCH (Vancouver Coastal Health) (2007), 2006 Vancouver youth drug reporting system: first results, Vancouver

Coastal Health Authority, Vancouver.

Wallin, E. and Andréasson, S. (2005), ‘Effects of a community action program on problems related to alcohol

consumption at licensed premises’, in Stockwell, T., Gruenewald, P. J., Toumbourou, J. W. and Loxley, W. (eds)

Preventing harmful substance use: the evidence base for policy and practice, John Wiley, West Sussex.

Wiggins, M., Bonell, C., Sawtell, M., et al. (2009), ‘Health outcomes of a youth-development programme in

England: prospective matched comparison study’, British Medical Journal 339, pp. 2534–43.

Wood, D. W., Greene, S. L., Alldus, G., et al. (2008), ‘Improvement in the pre-hospital care of recreational drug

users through the development of club specific ambulance referral guidelines’, Substance Abuse Treatment,

Prevention and Policy 3, p. 14.

WHO (World Health Organization) (1986), The Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion, World Health Organization,

Copenhagen.

WHO (1998), HEALTH21: an introduction to the Health For All policy framework for the WHO European Region

(European Health for All Series No. 5), World Health Organization, Copenhagen.

Yamaguchi, K. and Kandel, D. B. (1984), ‘Patterns of drug use from adolescence to young adulthood: predictors

of progression’, American Journal of Public Health 74, pp. 673–81.

Young, I. (2005), ‘Health promotion in schools: a historical perspective’, Promotion and Education 12, pp. 112–17.

Young, I. and Williams, T. (1989), The healthy school, Scottish Health Education Group, Edinburgh.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|